Chapters

Chapter 2

The Courage and Moral Choice Project: Maine, Phase 2

Phase 2 of the Courage and Moral Choice Project (CMCP) involved a more structured and planned learning experience than had Phase 1. Two teachers at an alternative public high school collaborated with researchers and artist educators to develop an integrated, three-month learning experience around stories of helping. Students participated on a voluntary basis and focused on these stories through language arts, history, art, and service learning experiences. They were encouraged to tell their own stories of courageous moral choices, and their exchanges led to more general disclosure and trust in the learning environment. Artist educators were brought into the schools to encourage students to translate their experiences of moral choice into poetry, essays, art, and songs. Teachers and students reported a more cohesive sense of community as well as increased empathy and awareness of the help of others among participants.

Keywords: interpersonal trust, expanded generosity, artist educators

1 When Michele Brierre and I walked into the rather small, late-Victorian building that houses the Forest School1 in September, during the start of the second phase of the CMCP, the excitement in the air was palpable. The students had been planning since the previous year; they eagerly awaited the day when Michele would come to talk to them about her experience during Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent building of the Ellis Marsalis Center for Music. The CMCP had been introduced the previous spring to the students by their English and art teachers, who had planned and integrated the humanities curriculum around the CMCP. The other guests that September day included Putnam Smith, a songwriter, and Martin Steingesser, a local poet. They both seemed excited, too, as they had just introduced themselves to the students through poetry and song that morning.

2 There was anxiety in the air, as well, discernable through the students’ questions: “Who are we supposed to interview?” and “How will we find them?” Students knew that there would be a community-based component of the project and that they would be expected to find stories of helping within their own communities. Their nervous and excited anticipation created an energetic atmosphere.

3 The second phase of the project proceeded through the next three months, during which plans were made and revised, and community members were engaged in ways that were sometimes structured and other times spontaneous. After the kickoff September event, students began to formally explore what moral courage meant to them. The first, introductory, day included images of the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina. Among these images were depictions of restoration efforts in New Orleans that told a story of extraordinary giving and many powerful examples of active care. One example of this generosity is the Ellis Marsalis Center for Music. It is a state of the arts performance center, built largely through donations in one of the areas hit hardest by Katrina. Healthy snacks and free or low cost music instruction are offered to area residents. Michele shared the ways that she maintained courage and equilibrium after losing almost everything in the floods of Katrina. She described the ways that she was eventually able to give back to those who had been generous to her family by helping to develop and direct the Marsalis Center. Her equilibrium was supported, in part, by giving back to the New Orleans community, as well as to their ancestral communities in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake.

4 Following Michele’s talk and slide presentation, Martin Steingesser and his wife, Judy Tierney, performed verses drawn from Etty Hillesum’s (1996) diaries. Hillesum was a writer who kept detailed and moving diaries before and during her life in a concentration camp and was eventually murdered in Auschwitz. The performance of Etty’s efforts to maintain her own humanity in the face of horror clearly moved the students; however, they spoke very little immediately after it concluded. It was in the safety of their own, smaller classrooms that they began to open up. Many students reported feeling inspired to tell their own experiences of struggle, hardship, and abuse.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

A Catalyst for Community

5 One of the significant themes that emerged from the first phase of the CMCP was the way that stories of active care functioned as a catalyst for students sharing their own stories. That theme reappeared in the second phase. Student Samantha reported that students “shared some of our own struggles resulting in a different perspective.” Some of the students who had shared the same classroom for months began to see one another in a different light as they became participants in the CMCP.

6 The second phase of the CMCP lasted four months. The interpersonal sharing had the cumulative effect of building an ongoing sense of community among many of the 18 students. In fact, the building of community was the outcome most emphasized by the teacher participants, Amanda and Molly as they reflected back on their experiences with the project. Molly described this as students “finding courage from each other . . . I think to carry on, which is really touching, knowing some of the personalities.” The prominent theme of shared stories and the building of interpersonal trust will be discussed in more detail, but first, more description of the start-up of the project will be provided.

Project Start-Up, Phase 2

7 The students and teachers organized themselves into two classes that focused on courage and moral choice through interdisciplinary investigations of literature, writing, art, and music. The students had all moved, for one reason or another, out of their conventional public schools and into the unique, alternative environment of the Forest School, which was designed for students who had experienced behavioral, emotional, or relational challenges, and who did not experience success in a conventional school setting. Many students had come from stressed home environments, some with significant financial and mental health challenges.

8 For many of the students, re-entering a school environment is an act of courage. This school was built on a “Safe School” model created around core values of respect, responsibility, accountability, tolerance, and community service. While students clearly saw this school as a caring environment, a sense of student community had been elusive. Students had been described by their teachers as “typically isolated (in school) or moving around in tight groups of two or three.”

9 The teacher participants began by introducing foundational questions to frame the students’ participation in the CMCP, such as, “Why do we want to learn this?” Some of the students’ answers included: “To understand people better”; “To be able to treat people better”; and “To remember we are all humans.” Creating a curriculum that drew links between the everyday and often serious challenges that the students faced with the world events and challenges shared by the speakers and artists was an ongoing focus of the project.

10 Once the purpose of the CMCP was discussed, teachers introduced the concept of moral courage with questions such as:

- Have you ever put your own needs aside for someone else?

- Have you ever experienced someone helping you without being asked? How did it matter to you?

- Have you ever wished you had made a more courageous choice, but didn’t?

- Do you think you have done anything that was courageous in your life? In a small way? In a big way?

After discussing these and similarly reflective questions, students were encouraged to make a visual expression in response to the discussion. The students’ ability to translate their experience into a range of storytelling and artistic methods of expression appeared key to its success with the many students.

Building Interpersonal Trust and Added Perspective

11 The most prominent experience that students referred to when they spoke about their involvement with the CMCP was the sharing of their own stories with each other. As Molly (a teacher participant) observed, “It helps a lot of people to tell their own stories, and explain what they have been through, and I think it helped them to feel more comfortable.” Student Samantha described this learning as a widened perspective:

The outcomes of deepened knowledge and broadened perspectives through the sharing of personal stories about courageous choice-making that emerged from the second phase of the CMCP did not come as a surprise to us because they arose as prominent themes in our first set of interviews. We were surprised by the depth of the interpersonal sharing that occurred. The two teachers who participated in Phase 2 intentionally encouraged a focus on shared personal stories, in part by sharing their own stories of personal courage and moral choice.

Helping as Catalyst to Connection and Expanded Perspective

12 In their interviews, both teacher participants from the Forest School agreed that one of the most important effects of the second phase of the CMCP was the building of a more cohesive community among the students. This appeared to be augmented by a compelling common focus, as well as by shared stories of vulnerability and helping. Amanda, a teacher participant, noted that: “We had kids who were incredibly disconnected to us and the program and the school altogether . . . , [who] began to share stories that they heard outside of school, find things that they saw on the internet, and share them with us on YouTube.” Teacher Molly added that, as the students shared their own stories, they began to identify courage in both their own stories and the stories of their peers:

Student Oliver described it this way: “You know, getting courage from people, and that you can learn, you know, looking at the other people what they had done in their life and getting an education from them. You learn from them.” Teacher Amanda noted the catalytic effect of sharing stories: “And it kind of built—so when one person shared an important story . . . it was easier for the next person to share . . . . Their empathy grew and they helped each other.”

13 We will return to the theme of expanded empathy, but first it is important to note an effect associated with increased connection—that of changed perspective. Three students noted a shift and expansion of their perspectives on other people. This included a changed view of their classmates, and an even more pronounced shift in their perspectives regarding the significant others who appeared in their own stories. Samantha said: “Well, a lot of the stories I’ve actually heard, like, surprised me, and just learning about what people have gone through and hearing their stories is amazing, and it, I think it has helped me have a different perspective on certain things.” Student Daniel mentioned that he doesn’t currently have other people to talk to outside of school, and that he has been able to see both students and teachers at the school a little differently: “In the school, I have a different perspective on some students and some teachers there. . . . I don’t really know about people outside of the school or family that I can talk to.” Both teachers were aware of their central role in the project, especially in relation to building trust and comfort with the sharing of personal stories. As Amanda put it,

A Heightened Awareness of the Help of Others

14 Students in this phase of the project described a heightened awareness of those who had helped them as they shared their own stories. This is consistent with our findings in the first phase of the project. Students in this second phase also described a heightened understanding of others, and during a community presentation, one student shared the observation that this understanding included their family members and the choices that those family members had made. Samantha spoke more generally about this understanding: “I have to tell myself, like, ‘Hey, they’re going through something that is affecting their decision, and this decision is for a reason.’ I guess just have to, like, try to understand more, that even if things might not be the best decision, it’s the one they made and that’s life.”

“I Guess I Matter”

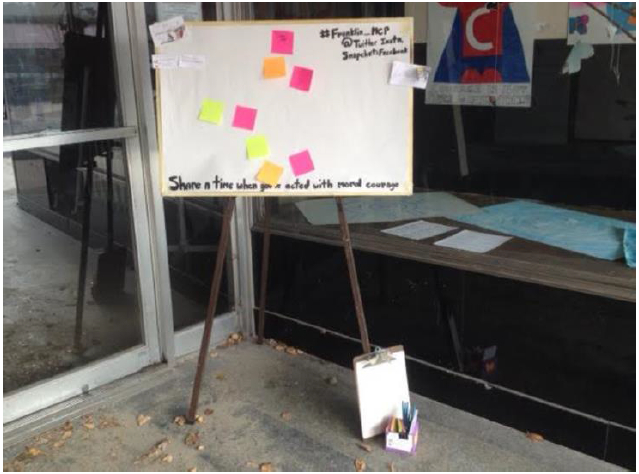

15 In addition to expanding their perspectives, telling and listening to their life stories encouraged a belief among student participants in the significance of their stories and their lives. “They just sort of went through life and never talked about it, but then, [after sharing their stories], they thought, ‘Well, I guess I matter’” (Molly). Amanda spoke of the added significance of sharing their stories with the school board at the conclusion of the project: “The kids could see that their stories are important. They felt connected up to the community and heard.” The students also reached out into the community to encourage others to share moments of moral courage. During an art walk in their city, they set up a storefront decorated with their art projects focused on moral courage, and with an easel that included examples of “helping moments.” Students encouraged those on a community art walk to add their own examples of helping others, by putting sticky notes on the easel.

Expanded Generosity

16 We found that reports of stronger connections and changed perspectives were correlated with increased empathy and generosity within the classroom. This effect in Phase 2 echoes the observed effect in Phase 1: that participants experienced the sharing of stories of helping as interpersonal generosity. Because there was an added emphasis in Phase 2 on sharing personal stories, the resulting connection appeared to build more sustained empathy among the participants. This empathy led, at times, to more interpersonal sharing. Initially, this giving was in the inspirational help of the stories themselves, as Molly pointed out: “As one kid broke down the barrier to buy into the journey, that inspired the next one to go. They got the courage from each other, I think, to carry on, which was really touching, knowing some of the personalities.”

17 Molly also gave an example of concrete generosity that manifested in the context of the CMCP:

The teachers also noted the insight that students had into the generosity of others, at times without any adult prompting or guidance.

In a reciprocal fashion, this expanded empathy further increased their sense of connection to one another:

One of the significant effects of the increased empathy for others was that students began to feel less alone in their struggles: “In the beginning, how taken they were when the community interacted, even on that small scale, with the message board. Um, I think that went deep for a couple of kids thinking that ‘Oh, there are other people out there, it’s not just us’” (Amanda).

“Things Are Not Going to Stay This Way Forever”

18 In addition to feeling less alone, students also described an evolving view of change: “After hearing everyone’s stories, I realize that things do get better and they aren’t going to stay like this forever, they are constantly changing” (Samantha). Student Oliver spoke about the way that the CMCP encouraged his expression of his experiences through song; this changed his view of himself and his relationship with music. He described a past standoff with his family, who had seen his interest in music as a pathway to drugs and possible poverty. He felt that his experiences with songwriting helped him to express his musical interests in new ways: “This community change my—pretty much helped me, helping me to focus on my music and that things working . . . [as a] songwriter, that has helped me more and more.” Samantha described her participation in the CMCP as formative of her decision to join the Navy:

A Community of Helping

19 The most significant outcome of Phase 2 appears to have been the development of a community of learners in a setting where, primarily because of past experiences, students had typically engaged in pairs or alone. Furthermore, it appears that the sharing of personal stories of courage engendered this sense of community, which was strengthened by mutual experiences and acts of generosity. Molly stated: “I think of the first day with a classroom full of kids in isolation and pockets of ‘What are we doing?’ and disconnect, and I remember how it ended; it was a very warm, full group.” Amanda also talked about some connections students made with their larger community:

20 Because there was less time spent on historic stories of rescue during this phase, it appears that there may have been less time spent wrestling with some of the larger moral questions. This suggests to us that a balance between the sharing of personal stories with the examination of historic, cultural stories of courage and moral choice may create both enhanced connection among participants as well as the motivation to wrestle with larger moral dilemmas.

Conclusion

21 The two phases of the CMCP each focused on stories of helping in challenging environments, and they each incorporated the use of artistic expression to help student participants process their responses to the stories. Both phases included the additional component of community service. Phase 1 developed over time, and while it involved considerable planning, there was less emphasis on planning for sustained engagement with artist-educators and associated workshops than in Phase 2. Phase 1 featured dramatic, historic stories of active helping, while Phase 2 focused more on students’ personal stories of courage in making moral choices. Several themes emerged across both phases, but with somewhat different foci. Examples of common themes were stories as reminders, stories as a reference point, and stories as catalysts.

22 Both the historically-based and the personal stories of helping appeared to remind student participants of those who had helped them in their own lives. In Phase 2, student and teacher interviews demonstrated that students gained new perspectives on those who had helped them. The students in Phase 1 reflected on how they would respond to their loved ones.

23 In both phases, the stories shared created a reference point from which student participants could examine their own lives and the lives of others. The larger, historic stories appeared to encourage reflection on moral choice, and the personal stories shared in Phase 2 encouraged reflection on individual choices and on the ways that lives change.

24 Finally, in both phases, the stories appeared to function as a catalyst for interpersonal sharing. In the Phase 2, with a more focused learning plan and community, story-sharing also led to increased interpersonal generosity. This interpersonal generosity sustained a sense of connection and community. This final effect leads us to wonder whether increased interpersonal sharing, generosity, and connection lead to a sense of safety reminiscent of the safety created by secure attachment. We have noted that secure attachment promotes helping behaviors (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005). Can a community built on a foundation of stories of helping and courageous choices approximate the experience of safety promoted through successful attachment?

Notes

1 Names of schools, students, and teachers have been changed throughout to protect confidentiality.

References

Adele Baruch, PhD, is Associate Professor and Chair of Counselor Education in Clinical Mental Health Counseling at the University of Southern Maine.