Chapters

Chapter 1

The Courage and Moral Choice Project: Maine, Phase 1

This chapter recounts the events and early research that inspired the start of the Courage and Moral Choice Project in area schools. The project appeared to work well in a school district focused on the need to develop a climate of inclusion and empathy, as the district had recently experienced a high influx of refugees from many parts of the world into a community that had been fairly homogeneous for generations. Teachers noted an increased tendency for students to share personal stories with others after listening to stories of helping under duress. They also noted increased engagement with questions of moral choice. Both students and teachers said that they repeatedly reflected upon the question of, “What would I do if faced with similar circumstances?” Students noted that they began to identify with the stories of helpers once they engaged in service of their own.

Keywords: moral elevation, life stories, social networks

1 At a regional university conference on life stories, high school students made presentations alongside university faculty, administrators, and teaching staff about their shared experiences with stories of helping under catastrophic conditions. The student presenters shared their responses through photographs, art, and essays, describing the ways that the stories changed both their understanding of history and their ability to share their own stories with others. For some, the stories also changed the ways that they interacted with their peers. In this book, we look at people’s responses to stories of helping, and we examine the interaction between stories of helping, the surrounding community, and the development of an altruistic identity.

2 Our exploration is rooted in both psychodynamic and social learning perspectives. The emergence of an altruistic identity may depend on intrapsychic and interpersonal maturational factors, but it also created by learning experiences that influence a person’s cognitive schema, placing one’s self in a context of “those who help” (Monroe, 2004).

3 From a psychodynamic perspective, we understand altruism as a mature defense (Vaillant, 1993, 2002) that encourages individuals to channel their own stress, fear, and anxiety toward actions that effectively help others. Additionally, we understand that secure attachment promotes the effective expression of helping behaviors (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005). This mature capacity has interpersonal and interactional effects, promoting facilitative group behaviors, and increasing a sense of trust, agency, and belonging in groups (Yalom & Leszcz, 2005). Two related questions from a psychodynamic perspective anchor this book. First, how do stories of helping effect the development and evolution of the mature defense of altruism? Second, how may stories of helping effect the expression of altruism in groups?

4 Kristen Monroe (2004) notes that altruistic actions most easily emerge with someone who has an established altruistic identity (i.e., someone who sees oneself as “one who helps”). Nevertheless, she also suggests (along with Irvin Staub, 2003, 2008) that conversely, taking action to help others begins to carve out an altruistic identity. Staub (2008) observes that by helping others, we come to know them differently. He asserts that a deepened knowledge of the “other” increases one’s desire to help. Aquino, McFerran, & Laven (2011) describe a phenomenon they call “moral elevation” as “becoming moved and even transformed by witnessing acts of extraordinary moral goodness” (p. 714). They find that moral elevation, as experienced through stories or through the evocation of memories of extraordinary helping, is positively correlated with behaviors that demonstrate social responsiveness to the needs and interests of others.

5 A question associated with these findings is how stories of moral elevation or active care interact with the cognitive dimensions of an emerging altruistic identity. Additionally, when these findings are considered alongside the interpersonal aspects of identity emergence, one might ask: How does the expression of active care in a group effect an emerging altruistic identity? How do these stories effect our self-perceptions as “one who helps”? Demonstrating active care in a group of helpers surrounds one with stories of active care. How does this network of helping effect a helping identity?

The Courage and Moral Choice Project: New England

6 The inquiry central to this book began as a study of individual participants and their experiences of hearing stories of active care. That study grew into an action-research project as the result of the continued interests, actions, and motivations of some of the original participants. The school-based aspect of the action-research project is called the Courage and Moral Choice Project (CMCP). It grew out of the enthusiasm of Mary, an alumna of a public university in Maine, who, at an event sponsored by her alma mater, was moved by stories of active care under catastrophic conditions. She believed that the time was right to bring these stories to her public school community, where she worked as a clinical mental health counselor. The story of her efforts and our collaboration to bring narratives of active care to her school is detailed below. The CMCP grew organically to include collaboration with English and art teachers, as well as school administrators, all of whom became increasingly convinced of the value of these stories. They became curious about how the stories might fit into current curricula and how they might bolster efforts to build a more inclusive school climate. The first phase developed into a multi-year project, growing each year, and culminating in students, administrators, and teachers participating in and presenting at The Life Stories Conference, a regional conference that focused on stories of active care.

7 The second phase of the project involved several of the original teacher participants and was a more structured initiative. For this phase, I worked with teachers from the Forest School, which is located in the same school district that helped bring the CMCP into existence. The teacher participants, various local artists, and I engaged students at the alternative school to develop poetry, music, and art in response to their experiences with stories of active care. As the CMCP evolved, we came to refer to the stories of active care as stories of courageous moral choice. Kim, one of the teacher participants, aptly summarized the making of these choices as “doing the right thing in the face of your fears or adverse consequences.”

8 This second phase of the project was developed over a year’s time and was presented through a series of learning workshops during the first half of the following school year. At the culmination of this phase, participating teachers, students, and administrators presented their art work, writing, and experiences to the local school board. Below, we present our analysis of the interviews of the participants, as well as participant observers. We have tried to describe each phase of the CMCP as clearly as possible so that our analysis is adequately contextualized.

The Focus of our Research Questions and Methodology

9 For the qualitative inquiry that is the CMCP, we used a grounded theory approach, allowing concepts and their organizational categories to evolve from the experience itself. For our analysis, we were guided by the principles of hermeneutics to understand our data: we did not simply look for the appearance and reappearance of certain words and terms to determine their significance; instead, we used the dialectical process of hermeneutical questioning, and it was in the back and forth of open dialogue that we determined the meaning and significance of words and concepts (Gadamer, 1989; Kvale, 1995, 1997, 2007).

10 Research questions have a special role in grounded theory, as the theory asserts that core concepts arise out of the data itself. Strauss (1996) points out that the original research questions that guide a qualitative study may arise out of both data and experience (p.14), but in order for the research questions to be effective, the use of previous experience must involve a continuous back and forth between old theory and developing theory. He says that although we may develop questions out of previous experience, these questions must be “checked out by further observation and interviews” (p. 15).

11 Even the most orthodox grounded theorists acknowledge that observation occurs in an experiential context and, because of our driving interests, we train our focus on specific areas and specific conditions. In Gadamer’s (1989) terms, this focused attention is shaped by the researcher’s presuppositions, but a dialogical engagement around meaning allows us to enlarge the horizon of our presuppositions to get “closer” to the truth of the observed setting (see also Kvale, 1995). While we began interviews with a brief formatted series of questions, we also engaged in dialogue to test the assumptions that we began to develop around meaning.1

The Courage and Moral Choice Project: Maine, Phase 1

12 After hearing Leo Goldberger, Professor Emeritus of Psychology at New York University, talk about his family’s escape and rescue from Copenhagen to Sweden during the Nazi Occupation of Denmark, Mary came to my office and stated simply, “We need these stories in our school.” The school where Mary, an alumna of the counseling program, worked as a mental health counselor is located in a largely blue collar, predominantly white manufacturing community in Maine that had experienced significant job loss over the previous two decades and had also recently become home to a large number of East African refugees. While many in the community were welcoming of immigrants, some were not, and Mary’s school and others in the area were experiencing the effects of rapid change. Teachers and administrators had been working to find ways to promote inclusion and cooperation, and Mary was one of the first to see the possibilities offered by our research project about stories of helping. The CMCP emerged as a four-year, multidisciplinary program to bring stories of active care to high school students and pair them with curriculum designed to facilitate the students’ engagement with these stories using a variety of media.2

13 The CMCP’s initial phase centered on raising student awareness of helping behavior via stories of compassion in action. A public high school—the Edmunton School—and an alternative high school—the Forest School—were involved,3 and both in-class experiences and out-ofclass community events were developed. Art and English teachers at both schools developed curricular initiatives that exposed students to stories of helping, encouraged them to consider their own experiences of helping or being helped, encouraged them to reflect on the personal impact of hearing stories about helping behavior, and directly engaged students in community service projects.

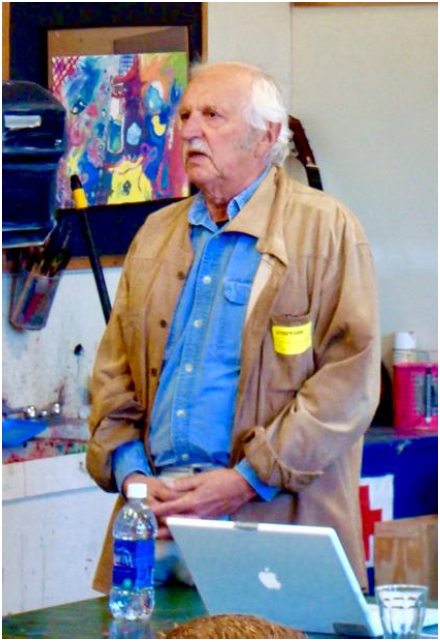

14 The first year of the CMCP focused on presenting stories associated with the rescue of Danish Jews during the Holocaust. Leo Goldberger, who participated in the rescue (and who assisted in the making of a documentary film and a book on the events associated with the rescue), told his story and engaged students in discussion. The corresponding CMCP curriculum included student essay responses to Leo’s presentation and the film about the rescue.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

15 During the next year, several additional curricular initiatives were developed around stories of helping. Students completed art projects that honored someone who had helped them or others in a significant way. After watching a film about a group of senior citizens who devoted themselves to welcoming returning servicemen and women, students in an English class were encouraged to develop service projects of their own. Other students conducted interviews of friends and relatives who had helped others and initiated ongoing service projects within the larger community.

16 Michele and Ulrick Jean-Pierre, a couple who had been helped and who had helped others in both the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and that of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, shared their firsthand stories of help during catastrophic devastation to students at the Forest School. Michele Jean-Pierre (now Brierre), an educator herself, had recently become the Director of New Orleans’ Ellis Marsalis Performing Arts Center in the Musicians’ Village, a collaborative effort of the New Orleans Area Habitat for Humanity, the citizens of New Orleans, and artists such as Branford Marsalis and Harry Connick, Jr. The Musicians’ Village provides adequate and affordable housing for musicians, their families, and others who were displaced after Hurricane Katrina. The Center also provides young people with a rich musical education, offering a performance center that attracts and invites artists back to New Orleans to share their music. Ulrick is an internationally acclaimed painter whose creative work has often depicted stories of the heroes and heroines of Haitian history. Both Michele and Ulrick had done much to foster and rebuild the arts community in and around New Orleans, and they had also received a great deal of help in rebuilding their home after the hurricane.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

The Life Stories Conference

17 Michele and Ulrick shared their stories at the area high school as well as at a community library event. Soon after those presentations, the students, teachers, staff, and community partners involved with the CMCP joined Michele and Ulrick in a series of presentations at the university conference on stories of active care. During these presentations, the students shared their experiences of hearing the stories, and they also shared artwork they had created in response to the stories, much of which described the individuals whose stories of active helping had inspired them.

18 A particularly powerful presentation at the conference featured the story of musician Elliott Cherry (2009), who created a performance piece about supporting his husband through the devastation of cancer. Titled A Finished Heart, this piece incorporates storytelling, music, and poetry. The students and staff from the CMCP were so moved by the performance that they immediately began talking about bringing it to their local community.

19 The concluding event of the first phase of the CMCP was another performance of A Finished Heart at the city library, co-sponsored by the CMCP and the Hospice of Southern Maine, and attended by students, faculty, and community members. After the performance, Elliott held an open discussion about his story of helping; he also shared his process of crafting the story into a performance. Numerous inspired audience members also shared their stories of loss and helping. This effect—the creation of an atmosphere conducive to sharing loss and grief—was described as an effect of hearing stories repeatedly during interviews for the Courage and Moral Choice Project.

20 We interviewed participants at several points during the four-year project. Those interviews of students, teachers, and others involved in the project, and the CMCP-related school assignments generated by students, were assessed and analyzed for common themes and serve as the basis for the remainder of this chapter.

Themes from the CMCP, Phase 1: Interviews and Observations

Would I Do the Same Thing?

21 This reflective question is one version of many similar questions that were posed repeatedly in our interviews of students and teachersabout stories related to helping during the Nazi Occupation of Denmark. These stories involved life and death decisions, and they engendered reflection upon choices made in more intimate and localized crises.

22 Sam, an art teacher in the district, spoke about the questions that arose in him as he heard Leo Goldberg’s presentation on the Danish Rescue, as well as more recent questions that arose after reading coverage of help during the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings:

Along with questions about courage and the capacity to respond in caring and courageous ways during catastrophes, participants voiced the desire to identify with those who helped. They also were reminded of those who had helped them in some way or another. As Katelyn, a student, put it:

23 Some students quite reasonably questioned whether they might be able to rise to the level of care demonstrated in the stories shared. One student, Andrew, expressed doubt that he or his friends would be able to care for a loved one in the way that Elliott provided care for his partner; however, he did feel encouraged:

24 While students and faculty were left questioning what they would do, it appears that their questioning was frequently productive. Both a student and a teacher spoke of the stories as a reference point, a starting point, from which to consider possible future responses in catastrophic situations of loss. Andrew, the student, observed: “If people don’t talk about it [death] that much, I think it’s when you come to that situation in your life to have some starting points, like a reference.” Kim, the teacher, agreed: “Just having this point of reference, because I think it’s hard to mentally or emotionally prepare to be in any of these situations that they describe in these stories. So when you hear them, you think, “I hope someday I have the courage to react in the same way.”

25 Not every student had a positive reaction to the question, “what can I do?” Amanda, a teacher at the Forest School, described an example of one of her students who found it too difficult to identify with the caring part of herself or others:

A certain amount of willingness to be vulnerable appears associated with exploring these stories of care. Amanda described it as “a very emotional and risky thing to try and reach out and help someone. And what if you fail or what if you’re rejected?”

They Start To Live It

26 Both Isaac (a student), and Amanda spoke at length about the need to feel safe and accepted in a basic way in order to explore or express our capacity for caring. Isaac talked about the tough façade he used to project and the growth he experienced in his ability to care after he felt accepted in the caring environment of his alternative school:

Amanda spoke about observing the process of change with her students as a result of being in a caring environment, and then taking the risk to help others:

Isaac echoed this link between the way a student is treated and how they behave to the rest of the world: “Whatever you’re taught is what you’re going to act.” He described himself as a bully in his earlier school who experienced repeated positive interactions at this alternative school:

Once Isaac began to see himself differently, he started to “live” the change; that is, he began to put his experience with receiving care into action by helping others in his community. Amanda described the change this way:

It appears that a caring school environment provided the foundation, or fertile ground, for stories of active care to “take hold” and become meaningful for Isaac. Opportunities for caring action in the community, when linked via curriculum design with stories of helping featured in the CMCP, encouraged a changed identity.

27 Here, we return to two of the central themes of this book. The first is the idea that helping occurs in the context of a caring network. This theme echoes Christakis’ and Fowler’s (2009) finding that helping behavior is much more likely if one is embedded in a community of helping. The second, which builds on Staub’s (2003, 2008) work, is that active care is encouraged by the experience of seeing others provide help by doing some good act, no matter how small.

28 Monroe (2004) has pointed out that while identity influences the choice to help, the experience of helping, conversely, has the power to transform identity. She notes that “identity constrains choice, but acts, in turn, to shape and chisel at one’s identity” (p. 262). This changing sense of self appears to open new possibilities for responding to others. Isaac’s comments suggest that the caring environment in the Forest School enabled him to let his guard down enough to show interest in the stories of helping. The stories, coupled with opportunities to help others, have empowered him to reshape his view of himself as “one who helps others.”

What Can I Do?

29 In addition to asking “What would I do?” several students asked the more action-based question “What can I do?” Isaac said: “I think hearing about the stuff makes you want to do more good things ‘cause you hear about the stuff other people have done, and you say ‘What have I done?’ and ‘What can I do?’” Amanda noted that stories of active care dovetailed well with the community values expressed in the Forest School. An inclusive sense of “family” is promoted in the school and students seek to join in the values of caring expressed by both their peers and their teachers:

30 One poignant interactive change was described by Adrianne, who participated in the conference with another student, by whom she had been bullied a couple of years prior. She herself is someone who had bullied others, and who had transferred to the Forest School, where she became immersed in its smaller, caring environment. She then participated in a small group that had formed to share stories of caring, identifying, and interviewing individuals she knew who expressed care for others. Finally, she prepared a presentation on her experiences to share at the Life Stories Conference.

31 Student Katelyn also presented at the regional conference. She described her first reaction and evolving understanding as she realized she was sharing the stage with someone who had previously hurt her in significant ways:

32 Isaac described the ways in which he changed when he entered the Forest School, a smaller environment than his previous school that also offered a caring atmosphere:

Amanda noted that many of the students who chose to participate in the CMCP continued to seek out people who embodied the qualities of those described in stories of active helping: “I think that some of them are able to surround themselves with people who have some of these qualities, so that they are able to continue moving forward and feeling the same way.”

33 Christakis and Fowler (2009) state that within experimental groups, “when a person has been treated well by someone, she goes on to treat others well in the future” (p. 298). They note that while our mirror neurons may predispose us to “practice what we observe in others” (p. 39), members of a network tend to promote the generosity within their network because “the sustenance of the network is in itself valuable to them” (p. 300).

34 One of the central questions of our current inquiry is whether stories provide a way to expand altruistic social networks. Although we may not be the immediate recipients of generosity when we encounter a story of helping, we wonder: Does hearing such a story help us imagine membership in a “club” we want to join? Do these stories provide company, hope, and modeling for our future (generous) selves? This is an especially pressing question as many of our pragmatically-oriented networks—which operate in a post-industrial, capitalist culture—tend to promote a fairly narrow and constricting focus on self-advancement.

35 I asked student Andrew if he had shared the story he heard from Elliott Cherry with others after first hearing it. While he had not shared the story, he had gone over and over it again internally. He said: “Well to be honest, I don’t know if I did. I will say, though, I thought about [it] a lot and just replayed it over in my head a bunch of times that night, and a few nights after.” He later added, “I guess for me, it made me really appreciate the people I love and made me want to show them. I could tell them more often.” Andrew’s answer suggests that the expressiveness and generosity demonstrated in Elliott’s story encouraged him to consider his expressed love and appreciation to those in his immediate network.

36 Student Katelyn noted that she began to think about helping others, and is especially inspired to help when she can see the potential effects of making that choice:

Here, Katelyn highlighted another dimension to the influence of stories of helping. She was motivated not only by generous and altruistic action, but by the described significance of that action. She also emphasized the relative influence of stories told by someone close to her. This echoes a theme that emerged from the reflections of those CMCP participants who heard stories of helping during the Holocaust; stories appear to be most influential when there is immediacy and presence in the telling. As Katelyn said,

A Catalyst

37 Immediacy and the opportunity for give and take appear influential. In both of Elliott Cherry’s performances, he opened the stage up for questions and discussions at the conclusion of the show. In both cases, audience members were moved to share stories of their loved ones and their loss. Sam, an art teacher participant in the CMCP, noted that the process of creating portraits of those who have helped encouraged students to share their own stories:

The stories of helping appear to create a safe environment that encourages personal sharing, often about grief and loss.

38 Kim, the English teacher, brought a number of students from different classes to see Elliott’s performance. They were an academically and culturally heterogeneous group of students from different grades:

Student Andrew also noted the depth of sharing after Elliott’s performance: “I saw a lot of people all suddenly seem to feel more comfortable talking about their grief . . . I think students talked about a lot of things I have never heard students talk about before.” Katelyn described a “chain reaction” as students shared their portraits of someone who had helped others in their art class:

I Think a Lot about the Stories I Choose

39 Noting the influence that stories of helping appeared to have had on her students, Kim stated that participation in the CMCP caused her to reflect further on the stories she chooses in her curriculum. Additionally, she stated that she was encouraged to reconsider her approach to facilitating the students’ telling of their own stories:

Teacher Sam also reported that he made changes to his curriculum. Although he described himself as historically drawn to thematic units (as they appear to create cohesion for students), this was the first time he devoted so much focus to the theme of active helping: “I just invited students to create projects focused on someone they knew who has helped [others]. And I never had so many students so eager to tell the stories behind their work.”

40 Teacher Amanda noted that the classroom projects associated with the CMCP were a natural fit for the orientation of the Forest School. She also noted the encouraging effect of involving students as presenters in the university conference. Attaching significance to students’ stories and actions appears influential to the level of receptivity students expressed. In her words:

Conclusion

41 Inspired in part by social tensions in a public school in Maine that developed in reaction to a rapid influx of African refugees, the CMCP was an effort to bring the potential beneficial effects to individuals and communities of encounters with stories of helping outside of one’s identity groups. Through the CMCP, students and teachers engaged stories of helping in the face of danger and despair, contemplating, reflecting, and learning via stories, performances, reflective assignments, and direct service to others.

42 Our analysis of interviews and writings by students and teachers both during and after the CMCP reveals patterns of response to hearing stories of active helping, as well as themes of personal change and strengthened community. Stories and experiences of the CMCP caused many of those involved to explore their identities as compassionate humans and helpers. Students and teachers involved in this phase of the CMCP were inspired to provocative self-reflection, asking questions such as, “Would I do the same thing?” (i.e., Would I summon the courage to help in the face of danger and despair?), and “What can I do to help?” Results from the first phase of the CMCP suggest that stories of helping can be effective for inspiring people to “continue the chain” of helping others, especially if students are convinced of the significance of these helping actions. An emergent question is whether stories of helping, coupled with supported opportunities to help, provide enough of a community to support an emerging altruistic identity even when the school environment is less than optimal. That is, could narratives of helping, coupled with opportunities to serve, possibly overcome some of the alienation in a more “typical” public high school? Might those narratives also promote a sense of connection with those who have helped elsewhere (as well as with the beneficiaries of efforts made by high school students to provide help to others)?

43 Our interviews suggest that if there is a lack of connection inside and outside of a school, it is unlikely that hearing stories of helping will have an impact. However, it also appears that a large high school may offer a sometimes cold and bureaucratic environment, even as it contains individuals who can express ongoing care and nurturance. Can these individuals, who sustain and nurture connection with others, provide enough safety to promote an openness to stories of helping to the rest of the community? Our interviews suggest that this may be the case, although our analysis is unable to provide specificity regarding the type and amount of nurturance needed in order to foster receptivity to and engagement with stories of helping.

44 Two of the student participants noted an increase in caring behaviors toward other students in the context of this project and a more nurturing school environment. Teacher Kim observed that large public high school where she teaches has worked on a number of initiatives to build awareness and tolerance of differences. The CMCP was one in a series of efforts to bring change to the school culture. She said:

We may sensibly conclude that along with several other school-wide initiatives to increase tolerance and care, the CMCP has been an important component of an effective effort to build a more actively caring school culture.

45 It does appear that narratives about helping in catastrophic conditions tend to inspire listeners to show interpersonal courage by sharing their own stories. (Again, we have only seen this in the context of a highly supportive teaching environment with teachers who are actively engaged in student learning and service to the community.) We observed students sharing their personal experiences with grief and loss after encountering stories of helping in both the alternative school environment and in small groups in a large public high school. These stories, therefore, might play a role in building a more authentic and coherent community as they appear to encourage interpersonal sharing and vulnerability. It is telling that teacher participants found themselves inspired to use stories of helping more with students after having participated with the CMCP, and that they expressed determination to be more deliberate about their choice of stories. Through their involvement with the CMCP, they found new ways to evoke meaningful personal stories of courage and a variety of ways to translate the students’ stories of courage into narrative and artistic expression.

Notes

References

Adele Baruch, PhD, is Associate Professor and Chair of Counselor Education in Clinical Mental Health Counseling at the University of Southern Maine.