Articles

(Re)telling Stories of Middle School Student-Led Bands:

How One Music Teacher Becomes a Narrative Researcher1

Finely polished prose and clean analysis is abundant in scholarly publications. Yet the academic writing process of drafts, peer review, and revisions that lead to these polished papers is one of trials, triumphs, discovery, and self-doubt rarely revealed to new scholars. This paper is one attempt to demystify the writing as inquiry process through the lens of narrative inquiry. Using three drafts of the same researched text, this paper tells the story of twin journeys: my journey from music teacher to narrative researcher and my middle school music students’ journeys through a student-led curricular unit.

1 Narrative inquiry requires researchers, according to Clandinin and Connelly (2000), to “write about people, places, and things as becoming rather than being” (p. 145). The goal of any narrative inquirer is to convey the story of a research participant’s experience contextualized within his/her lived world. Yet, conveying experience or the process of becoming within the three-dimensional inquiry space (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000), is a complex writing and cognitive task. Often, as scholars, we do not “lift the veil” on the research and writing process. I believe this does a disservice to new scholars who only see final, polished works. The process of writing scholarship, of becoming a social science researcher of any ilk, is a lengthy cognitive task filled with drafts past, present, and yet to come.

2 In this paper, I focus on the process of becoming a narrative researcher myself. Early in my doctoral studies, I enrolled in a narrative research methods course. I was searching for an approach to scholarly writing that enabled me to write things I enjoyed reading. What I discovered through the process was that writing scholarship in an evocative and compelling style while conveying a scholarly message was far more challenging than I had imagined. Rich (1994) summarizes the plight of the narrative researcher well: “You must write, and read, as if your life depended on it” (p. 33). This paper is a story of writing as if my life depended on it, writing and revising in order to become a narrative researcher.

3 In engaging with my research context, I proceeded through a process of writing described by Clandinin and Connelly (2000) as one in which the writer is “engaged with composing many versions of narrative texts prior to selecting the one they eventually create,” a process requiring several drafts, feedback, and reflections (p. 165). They continue to describe this process of narrative writing in this way:

4 What follows is the presentation of three different attempts at writing a research story modeled on work produced by other narrative scholars. In each version, I provide excerpts from the complete story in order to demonstrate the types of writing I was attempting in my process of becoming a narrative researcher. I follow each of the three attempts with a self-critique of the narrative style shaped by comments from readers and scholarly work I was reading concurrently. In each reflection, I interrogate the narrative style and approach as well as the success of the storytelling I was attempting.

The Research Project

5 Beginning in November 2011, my eighth-grade general music students (eight girls) and I embarked on a curricular unit designed to help them create their own popular music “bands.” Groups of four students joined together to become a popular music “band” and were tasked with creating cover songs. Successful cover songs are not recreations of the original recording, but rather a new conception, or a performed interpretation, of the same melody and lyrics. The students were asked to determine their collective musical influences and develop their band’s musical identity. They were then asked to choose a song that fit the course definition of a ballad (a song with a verse and chorus that tells a story) and a winter holiday song. The end goal was to create a cover of each song that could be performed at the end-of-semester concert. This was a student-led curricular project; all decisions, including musical ones, were left to the students in each group. I provided guidance and materials only when asked.2

Data Collection

6 The research project presented here began as a practitioner inquiry (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009), but evolved into a narrative study during the analysis and writing process. The research project itself emerged from my teaching practice. This curricular project started at the beginning of November and the class met once per week for 50 minutes for six classes total prior to the performance at the end-of-semester concert. Following the first introductory lesson, most lessons consisted of a brief teacher introduction followed by group work time. My teacher role was to monitor the group work and allow the students to direct their own learning. In the final five minutes of each class, I posed a reflective question, focused on the students’ musical progress or group interactions, and asked each student to respond in her journal. As a teacher reading my students’ thoughtful journal responses, I found myself invigorated and intrigued by the things they had to say. Learning from their reflections each week, I was able to make curricular adjustments that would best serve them as individual learners and as a group. In reading the journals, I found that the groups’ expressions conveyed an experience of music learning with a story waiting to be told. In January, students worked for three class periods on an assignment that required them to reflect upon the band project and rewrite the lyrics of a known song to tell the story of their experience with the project. Student and teacher written texts, including weekly reflection journals, composed song lyrics, and curricular documents were the primary sources of data collected. The reflective work produced by students and my own teacher reflective journal serve as the primary sources of data for developing the narratives herein. Seven of the eight students provided written consent to participate in the project. All student names are pseudonyms, but the band names “The Undecided” and “Ctrl Z” are the names chosen by the students. All direct quotations preserve the students’ spelling and grammar errors.

Analysis and Narrative Writing

7 Throughout the analysis process, I was one of twelve graduate students enrolled in a narrative methods course that included significant peer debriefing. Following the construction of each version of my narrative, I met with a group of classmates who provided feedback on the draft I presented. Spall (1998) suggests that “peer debriefing contributes to confirming that the findings and interpretations are worthy, honest, and believable” (p. 280). I personally found this process challenging, yet rewarding, as I felt that each version was closer to elucidating the core of my students’ experiences.

8 Two aspects of this peer debriefing were particularly useful to my process of becoming a narrative researcher. First, my peers continually challenged my writing for clarity and thematic analysis. I learned that the knowledge gained from first-hand experience of a research site is not easily conveyed to a reader. These peer reviewers, none of whom were music teachers, required me to think deeply about how to convey substance clearly for the average scholarly reader. In fact, “talking about issues” in this setting generated new ideas that caused “the murky [to become] clear and sharp, and new descriptions [to] surface” (Spall, 1998, p. 285). Without this peer review, I would not have discovered the themes that eventually shaped my final work. Second, my peers challenged me to continually reexamine my data in search of the heart of the narrative. The “process of exposing [myself] to a disinterested peer” helped me to explore “aspects of the inquiry that might otherwise [have remained] only implicit within” my mind (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, p. 308). Each week’s peer debriefing provided me with feedback about the storytelling format I was using and helped me question the theme or themes I was attempting to unravel through the use of storytelling. The reflections I present at the end of each narrative version are based on the peer-review process.

Version 1: A First Attempt

9 In this first attempt at narrative writing, I modeled my writing on Watts’ (2007) article, in which he cleverly crafted sentences that connected two different ideas written on the page in parallel before rejoining them to continue writing a single thought. My attempt to do so focused on the parallel stories of the two bands formed by the students in my class.

Excerpts from the Narrative Draft

10 As is clear from the quantity of books and VH1 specials telling the “untold” story of the life behind the music, the formation and maintenance of a popular music band is not an easy or uncontested process. Over the course of the project, four students—Sydney, Anya, Emily, and Chloe—formed the band The Undecided, while Maddie, Rachel, Lilly, and Adrian formed the band Ctrl Z. Using the girls’ words from their journals, I tell these two parallel stories of two bands that began and ended in the same place, but took very different paths of development. My words stitch the girls’ words together, but it is their story. The story of The Undecided is found on the left and the story of Ctrl Z is found on the right. Words taken from my own teacher reflection are marked as Teacher Reflection followed by the date and page number. In the style of Watts (2007), I use full paragraphs to connect the two columns of text together. The final or opening sentence in each full paragraph connects to the first or last sentence in each column.

11 In the opening lesson, I introduced the curricular unit to the students, but as a teacher I was plagued with worry: “Would it work? Would the girls find it interesting?” However, “I was shocked by how quickly they began working together as a group and discussing different parts of the project” (Teacher Reflection, 11-2-11, p. 1). Their excitement about becoming a popular music band is clear in their words:

12 The excitement of this first day carried throughout the project, though it was occasionally punctuated by frustrations, setbacks, and difficulties as the girls struggled individually and as a group. These struggles took many forms, primarily focusing on musicianship. In this section, Emily and Sydney in The Undecided question their musical abilities, while Adrian, Rachel, and Maddie in CtrlZ discuss their personal musical challenges:

13 As the teacher, I worried that I had not equipped the students with enough musical knowledge to complete this project. Much of this project relied on the musical training that the girls had obtained in earlier years in school or in musical lessons outside of school. As Emily articulates, not every student’s musical talent or experiences with music are the same, yet each student had a responsibility to participate in her group.

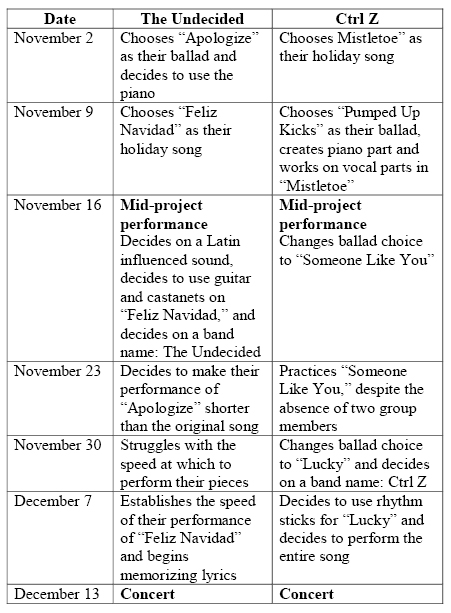

14 Some aspects of the project (like the mid-project performance on November 16 and the concert on December 13) occurred simultaneously for both bands. Other aspects of development occurred at dramatically different times:

15 The Undecided chose their ballad and holiday song and remained with the songs the entire time, working throughout the project to limit and perfect their performances, while Ctrl Z changed their ballad choice three times throughout the weeks of the project. Neither group chose a band name early, but Ctrl Z left the band name selection to nearly the last minute. Similarly, choices about musical roles were made at different times based on a variety of factors and inter-group relationships.

Peer Response and Researcher Reflection

16 At the time, I was rather reticent to share a rough draft with others, but was attempting to learn to do so. In reading Watts (2007), I was intrigued by the way he was able to craft sentences that connected two different ideas. Since I wanted to tell two stories, one of each band, I thought that this might be a good model to follow. As I shared Version 1 with three of my twelve classmates, I was less confident that what I had written was working in the way that I intended, particularly since I had been unable to connect sentence fragments in both columns to the larger paragraphs in a way that mimicked Watts’ article.

17 Two suggestions were offered during the reading and discussion that I found interesting and useful to consider as I crafted the second version of the stories. First, the major problem that readers had with the text was that the stories of the two bands were not different. This gave me pause because each band developed very differently. What had occurred was that, in trying to line up the text so that it could be read logically, I had rearranged the text so much that the two groups appeared exactly the same, save for the dates found in the parenthetical documentation. Readers reported that they typically read right over the parenthetical documentation in a text. Unfortunately, the parenthetical documentation, which showed the dates on which students had written particular statements, was what held the explanatory information regarding how differently each group developed. This was clearly not working for the reader.

18 Second, it was suggested that I create a chart showing the major differences between the two groups’ development. In response to this suggestion, I wondered aloud if a chart would take away from the narrative aspect, but the classmate suggesting the chart said that sometimes a chart is just more useful. I thought I would at least attempt a chart to see what would happen, even though I was concerned that it would break up the narrative (not that I was certain I yet had a narrative). In reflecting on the way in which I constructed Version 1, I realized that simply linking quotations from the students together in succession did not tell the kind of story I was hoping to tell, nor did it work to assume that readers would notice dates found in parenthetical documentation. As I proceeded forward, I knew I needed an alternative method for telling these two stories.

Version 2: Presenting Data on Paper

19 In this version of the narrative, I revised Version 1 so that the bands’ stories were indicated through two different fonts instead of displayed in parallel. In addition, I added the chart suggested by the peer reviewers who examined Version 1. At this point in my process of becoming a narrative writer, my main focus was on how to distinguish two parallel stories physically on the page. As a writer, I was more interested in design over coherence or substance.

Excerpts from the Narrative Draft

20 Using the girls’ words from their journals, I tell these parallel stories of two bands that began and ended in the same place, but took very different paths of development. At times, both bands were at the same point in development, while at other times, they were in completely different places. My words stitch the girls’ words together, but it is their story. In order to distinguish the two “voices” of the bands, all text from The Undecided is in Courier New font while all text from Ctrl Z is in Arial font.

21 When does a popular music band actually come into existence? Some might argue that it is during that first practice in a parent’s garage, or in this case, in the choir room. Others might say that it is that first performance for friends or neighbors. It was not until the third week of the project that the girls realized that they truly were becoming a band. In my reflection I noted that “today I pushed the girls to have ‘something’ ready to perform” (Teacher Reflection, 11-16-11, p. 2). For each group, that “something” was different and “the performances were short and rough” (Teacher Reflection 11-16-11, p. 2), but it was the first time that the students began to feel like a band. My assessment as a teacher was that “the girls got a lot out of hearing the other group and also seeing how much they have already actually accomplished” (Teacher Reflection, 11-16-11). Although the experience was a good one for each band, the experience of performing a “rough draft” was different for each group:

22 Although some aspects of the project, like the mid-project performance on November 16 and the concert on December 13 occurred simultaneously for both bands, other aspects of development occurred at dramatically different times. The chart below shows each band’s progress through some of the pivotal decisions required for becoming a band. Following the chart, the girls describe these decisions in their own words.

23 The Undecided chose their ballad and holiday song and remained with these songs the entire time, working throughout the project to limit and perfect their performances, while Ctrl Z changed their ballad choice three times throughout the short weeks of the project. Neither group had an easy time choosing a band name, but Ctrl Z left the band name selection to nearly the last minute. Similarly, choices about musical roles were made at different times based on a variety of factors and inter-group relationships.

24 In addition to group dynamics, another challenge for the students was the final public performance for their families. This public display of learning at the culmination of the project brought out both student and teacher nerves. Given the authority the girls had over the production of the performances, I believe typical concert performance nerves were heightened. As a teacher, I was concerned about how different our performance would be compared with the ensemble performances or the performances of the other grades. As a first-year teacher at this school, I had doubts. In my reflection I wrote: “I hope that the parents understand. I hope that it is ‘musical enough.’” (Teacher Reflection, 12-13-11, p. 4). The two bands had very different performance experiences, specifically: “Ctrl Z had to stop in the middle of “Mistletoe”” (Teacher Reflection, 12-13-11, p. 5). Even though I had heard them perform the song dozens of times, I was unsure what actually happened to make the performance stop and the girls to begin laughing. I had to step in as the teacher and get the girls calmed down and reorganized in order to start the performance again. As a teacher, I was fairly embarrassed, but as I noted in my reflection “no one seemed to mind all that much,” even though I was still “worried about what the adults [were] saying” (Teacher Reflection, 12-13-11, p. 5). The girls’ individual performance reflections show how each band experienced this culminating public performance:

Clearly, the performance experience was filled with nerves, but also with a sense of success. Even though Ctrl Z had a hiccup in their performance, this was not felt as a major disappointment by the students.

Peer Response and Researcher Reflection

25 Unlike with Version 1, I was more confident in bringing my writing to class, but even so, I was displeased with it. I incorporated the suggestion of the chart, but discovered that it still did not convey the meaning I hoped. According to Richardson (1997), “Unlike quantitative work, which can carry its meaning in its tables and summaries, qualitative work depends upon people’s reading it” (p. 87). This statement became painfully obvious when I was told that when reading the chart, it was still not clear that Ctrl Z chose three different ballads during the course of the project. Apparently, just like parenthetical documentation, a chart could not convey the critical data of the bands’ development.

26 In the discussion of Version 2, I asked my peer reviewers if it might be better for this narrative to be written in two actual stories, one following the other. The font changes really were not working successfully to convey the differences in the development of the two bands, my primary writing goal. I had been pondering writing two different versions of the narrative, one for each band, after reading an early version of Nichols (2013) and then rereading Cape and Nichols (2012). In both articles, the concept of multiple stories is “played with” in ways dramatically different from my original inspiration (Watts, 2007). Nichols tells the research participant’s story as well as the researcher’s story while Cape and Nichols (2012) present two different stories within the same article. I had been considering the latter as a better solution than the use of fonts I tried in Version 2. I felt that perhaps Version 2, while better, was still not telling an actual story in prose form. My peers agreed that this idea might work better.

27 This second peer review resulted in two major suggestions. The first focused on the substance of my writing and the second was on the written prose. One peer reviewer suggested that I write the major differences between the two student bands on a sheet of paper. This would enable me to see what I really wanted to write about thematically. The peer reviewer suggested that I then use those notes to attempt to write a true “story” in prose form. The second major suggestion was that the stories I was telling, through the font changes, needed much more commentary or narrative in order to connect the quotations from the girls to the actual story I was telling. This peer reviewer wanted me to write in prose form, more like a novel than the choppy writing I had produced thus far. Clandinin (2013) suggests that, as narrative researchers, “we must stay wide awake to be open to what is possible as well as to what becomes visible in the stories of experience” (pp. 206-207). With these two peer suggestions, I was suddenly awakened to the possibility of writing my research like a novel or short story. In earlier versions, I had tried to write in ways that I thought reflected “scholarly” writing, mimicking others in my quest to convey meaning. I was so concerned with honouring my students’ voices that I had forgotten my reasons for taking a narrative research method course in the first place: to engage with scholarly writing that I actually wanted to read.

Version 3: Two Stories

28 As I began the process of reanalyzing the data and revising my writing a third time, I was plagued by several questions. How do I tell a story that stays true to the students’ experiences? How can I use the students’ language as much as possible while creating a coherent narrative? How can I conceptualize the stories in the way I need to as a researcher while not taking away the students’ ownership of their experiences? I wrestled with these questions as I wrote—very slowly— Version 3.

Excerpts from the Narrative Draft

The Undecided: The story of a very “decided” band.

29 Sydney, Anya, Emily, and Chloe joined together to form the band they later named The Undecided. As the group name might suggest, members of this group were often plagued with worry and insecurity about the project: “I’m afraid that I’ll let my group down” (Sydney, Journal, 11-2-11), despite the fact that the way in which they planned their performance was anything but Undecided.

30 Four students gather around a handout provided by their teacher and carefully complete the answers to each question. It is the first day of a new project and I have just introduced the assignment and handed out a planning worksheet to each student. The four girls assign roles and responsibilities to each group member: Sydney will be the Conductor; Anya, the Manager; Emily will serve as the Publicist; and Chloe will serve as the Producer. Systematically and quickly, they answer some of the easier questions first, leaving the band name and musical influences (even though those are first on the list of questions) until the end. As a group, they will make decisions democratically and by the end of class have “chose[n a] ballad and kind of chose[n] a few holiday songs” (Anya, Journal, 11-2-11).

31 In their individual reflections at the end of class each girl voices her own feelings about the project, feelings that are both positive and negative. Sydney says, “I feel like this project will help me with team-building skills and I feel good about it because music is an interest of mine” (Journal, 11-2-11). She is joined by always-positive Anya who says, “I feel that this project will be very fun and I cannot wait to hear what the other group will do at the end of the year!” (Journal, 11-2-11). However, the feelings are not all smiles and rainbows in this group. Emily has concerns: The project “should be pretty fun, I just hope that my group doesn’t crash and burn or get into arguments over things” (Journal, 11-2-11). Despite these misgivings, the students in this group leave class with many decisions already made. Their decision-making skills and ability to come to a consensus have made their group appear very cohesive right from the beginning.

32 On the second day of the project, Anya, Emily, Sydney, and Chloe gather around the grand piano in the choir room. After I have a brief meeting with Sydney in her role as Conductor, they all gather around Emily’s laptop to listen to the music I provided. In her reflection on the day, Anya shares the progress her group has made in only a short time: “Today class was very interesting . . . But! We figured out our ballad and Holiday song! Even though I don’t know many holiday songs I am sure I can memorize “Feliz Navidad! Hopefully next class we will get more organized as I am the Manager! The other group sounds like they know what they are doing but, no worries we will too . . . SOON! (I hope)! (Anya, Journal, 11-9-11).

33 Although Emily and Sydney join Anya by agreeing that the group has decided on a ballad and a holiday song, they have personal doubts about the success of the project. Emily’s doubts stem from her previous and less than successful forays into musical training, which lead her to conclude that “I feel kind of useless in my group” (Journal, 11-9-11), while Sydney is plagued with worry about her piano skills: “I want to be successful, but my piano playing not being too good is going to be a problem. Also, I wanted to do something I knew a little better, but it doesn’t really matter now” (Journal, 11-9-11). In this statement, it is clear that the democratic procedure is in place in this group—Sydney would have preferred another song and seems to have lost the vote, a loss she is trying to deal with in order to proceed with the project.

34 The night of the concert arrived and all four girls seemed nervous, but not overly so. The Undecided performed second after the performance by Ctrl Z. “I was really nervous about it before we went on” (Emily, Journal, 12-14-11), but despite individual nerves, all four girls appeared calm and collected as they took the steps to the altar turned stage. For their first number, Sydney took her seat at the piano and the other three girls stood on the steps to sing their cover of “Apologize” by Ryan Tedder. Emily and Sydney were selected by the group to provide the song introductions that the girls had prepared for the concert. For the second number, Sydney, Anya, and Emily gathered around the chair on which the guitar player sat to play their acoustic version of “Feliz Navidad.” “All in all it was good and the audience CLAPPED” (Anya, Journal, 12-14-11).

35 And the audience CLAPPED. The emphasis Anya placed on the word “clapped” perhaps best summarizes the girls’ experience forming The Undecided. Anya’s comment articulates the collective surprise this group experienced throughout this project. As a group they seemed continually unsure of their ability to be successful in creating a band. While they worked together in a very systematic way, they struggled with confidence. Though they made decisions quickly and easily throughout the project, perhaps The Undecided is, in fact, an apt name; they individually and collectively felt undecided about their ability to succeed.

Ctrl Z: Undo and start again.

36 Maddie, Rachel, Lilly, and Adrian formed the band Ctrl Z. The story of Ctrl Z is one of anxiety for the teacher and blissful confidence for the students who spent most of the project believing, in the words of Rachel, that “MY GROUP IS SO EPIC!” (Rachel, Journal, 12-7-11).

37 Three students gather around the desk upon which Maddie sits. They are reviewing the band planning handout that I have just provided them. Rachel has her pencil poised to fill in the answers to the questions. Their discussion is lively and animated as they discuss bands they like, bands they dislike, and bands not all of them know. The musical discussion ranges from Justin Bieber to The Beatles and zigzags through numerous other musical groups before returning to Justin Bieber’s “Mistletoe,” which has just been released for the holiday season.

38 Lilly, Rachel, and Adrian sit near the upright piano in the corner of the choir room listening to a recording on a laptop that sits on top of the piano. “After looking more carefully, I discovered that Maddie was nowhere to be found” (Teacher Reflection, 11-9-11, p. 2). “I found her in the classroom attempting to print the lyrics to a song,” a process that took up much of the class time and prevented her group from making any decisions in her absence” (Teacher Reflection, 11-9-11, p. 2). In her reflection on class, Maddie shares her experience:

39 Though they faced some challenges in this first rehearsal, each girl’s journal echoes Rachel’s when she says, “Today, my group made a lot of progress; I think we’re on the road to success!” (Rachel, Journal, 11-9-11). Rachel and Lilly also mention the selection of their ballad song, which Rachel details as “‘Pumped Up Kicks’ by Foster the People,” a selection with which “everyone was happy” (Rachel, Journal, 11-9-11). However, this is the first of two ballads that will be chosen, agreed upon by everyone, and ultimately rejected before the third and final selection is made, two class periods before the concert.

40 The night of the concert arrives, and Maddie is bursting with hyper energy. Lilly and Rachel are dressed as “men,” complete with paper bow ties for their role singing the “male” part in “Lucky.” All four girls make eye contact with one another and begin playing the steady beat on the rhythm sticks. Their performance of the hastily prepared “Lucky” begins and ends successfully. Yet this is only part of the performance story. The concert CD features three tracks, rather than two, because the girls started “Mistletoe,” collapsed into giggles in the middle of the song because they messed up the lyrics, and had to restart the song. This mistake required teacher intervention to help them collect themselves and start again. In order to solve the problem, Maddie, who was playing the jingle bells, “had to sing it [‘Mistletoe’] as well” (Maddie, Journal, 12-14-11). Despite this mistake, all of the girls felt that they had a successful performance. “I thought my group did a great job at the performance overall” (Rachel, Journal, 12-14-11). “I felt pretty good about how we did, even after the mess up” (Maddie, Journal, 12-14-11). “We messed up on our second song, but we did well. We were able to keep our spirits up, though!” (Lilly, Journal, 12-14-11).

41 The story of Ctrl Z ends with mixed reviews. The girls thought their performance was successful, despite the fact that they erred during the performance in front of the audience. Although I would love to say, in conclusion to the Ctrl Z story, that their band name, Ctrl Z, is a carefully selected metaphor for the fact that they needed to go back and “undo” some aspects of their experience as a band, this is not the case. Several weeks after the project ended, Lilly was sitting at one of the classroom computers working on her liner notes project when she exclaimed, to the room at large, “Control Z actually does something!” It seems that they did not know when they selected their band name that when the computer keys Control and Z are pushed together, the previous activity is undone.

Peer Response and Researcher Reflection

42 The process of writing these two stories was a challenging one. In crafting this version of the narratives, I broke through the wall of my narrative researcher chrysalis, but did not fully emerge. In presenting this version for peer review, I felt that I had indeed moved forward in my process of becoming a narrative researcher.

43 Instead of focusing on the most recent iteration, my peer reviewers wanted to discuss all three versions of the narrative. I was asked to speak about my project and the changes I made from Version 1 to Version 3. Peer reviewers thought that the new stories were easier to read and understand, but they wanted to know how I planned to connect the two band stories in an overarching narrative.

44 As I answered the peer reviewers’ questions, I began considering metaphors appropriate for conveying the developmental trajectory of The Undecided and Ctrl Z. I started to see a metaphor of a path, one straight and narrow (The Undecided), the other winding and serpentine, filled with switchbacks and dead ends (Ctrl Z). This is how I, as the teacher/researcher, saw the development of the two bands. Yet based on what the students had written in their journals, it seemed that the groups believed the exact opposite about themselves. In the students’ minds, The Undecided was the group on the serpentine road filled with concern and lack of confidence, while Ctrl Z was on the straight and narrow, completely oblivious to their own messy organization and development. Could I write a version of these two stories that presented this metaphor as the constructing framework? In doing this, would I be able to remain truer to the girls’ own language and not insert my own voice into their words?

The Process of Becoming

45 Through this process, I confronted two critical aspects of scholarly writing: voice and the writing process. In order to continue on my path toward becoming, I had to negotiate internally (and thankfully with the help of peers) to develop my own understanding of scholarly voice and my writing process. Negotiating these two aspects of scholarly writing led me to understand more fully how writing as inquiry is an important component of narrative inquiry.

46 First, the three narrative versions presented herein each feature aspects of my voice as researcher, my voice as teacher, the voices of my individual students, and the collective voices of the two student bands. Each narrative version plays with the prominence of these different voices. Clandinin and Connelly (2000) suggest that “in narrative inquiry, there is a relationship between researchers and participants, and issues of voice arise for both” (p. 147). I wanted my students’ voices to metaphorically sing off the page, but the story I was attempting to tell seemed to lower their voices to pianissimo as my researcher voice conducted their voices to conform into the story I was trying to tell. Unfortunately, as perhaps these versions do, “being there in [a] special way” as a teacher and researcher caused a “dilemma of how lively [my] signature [as a teacher or researcher or both] should be [since] too vivid a signature runs the risk of obscuring the field and its participants” (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000, p. 148). In this process of becoming, I had yet to find my voice and the correct use of my participants’ voices in the telling of this particular aspect of the story. Perhaps their voices are best honored by two side-by-side poems created to introduce the groups. The text for the two poems below is drawn entirely from the students’ concert introductions, journal entries, and liner notes. Though all text is directly quoted, in order to maintain the poetic structure no quotation marks or citations are used:

We are The Undecided

Striv[ing] to perform good music

With a Latin influence

Some days were good

And some were okay

Our group goals were

To recreate two songs

And to put in our own different flair

Our group indeed met its goals

And we all kept our roles

A challenge was the counting

On our Spanish song

But a success was that we made it work

So you can sing along

We ACTUALLY sounded good!

And the audience CLAPPED

We [are] mainly influenced

By very harmonic bands

Like

The Beatles

We were able to work

And communicate well with each other

We learned that

We were able to respect others opinions,

Even if we didn’t completely agree

If [we] had to change one thing

[We] would have picked a ballad earlier!

Something interesting:

We actually made up

Our own piano part for this song

[OUR] GROUP IS SO, SO EPIC!

47 Second, I discovered that the process of narrative writing, the engagement with multiple drafts and feedback, is actually a “method of knowing” (Richardson, 1997, p. 89). As I wrote, I began to see things in the data that I had not noticed before, and the feedback from my peers forced me to engage deeply with the data and question my interpretations of how each band had developed. I began to better understand my research data as well as what I hoped to convey in the researched text. I found that, as I wrote each version, my “self-knowledge and knowledge of the topic develop[ed] through experimentation with point of view, tone, texture, sequencing, metaphor, and so on” (Richardson, 1997, p. 94). Indeed, I became more knowledgeable about my research and began to form insights into my data, insights that have since become other, differently nuanced stories outside the parameters of this paper. Richardson (1997) explains:

Writing three drafts, engaging in three peer debriefing sessions, and then conducting three reflections, allowed me to discover that there is “no such thing as ‘getting it right’; only ‘getting it’ differently contoured and nuanced” (Richardson, 1997, p. 91).

48 The goal of this paper is to lay bare the process of scholarly writing and reveal how I wrote during the process of becoming a narrative researcher. As I wrote different versions of these band stories, I was forced to reflect on my meaning and the construction of the story. According to Elbaz-Luwisch (1997), “reflection brings the narrative researcher up against the edges of the work, and requires him or her to examine the context within which the research is carried out and its broader implications” (p. 75). While I was not satisfied with Version 3 of my story, it is fairly close to the final version I developed as part of my early doctoral work. Although this paper is about “becoming” a narrative researcher, the project described was actually just the first tentative steps down that pathway. I have conducted other narrative inquiries since this initial attempt and yet I still feel as though I am in the process of becoming a narrative researcher.

49 As scholars, each new project presents unique challenges, and fresh writing, reflection, and review provides additional insights for development and improvement. For me, this is one of the primary reasons to conduct narrative inquiry. The search for the story within the data and the journey of analysis and writing are difficult, but ultimately this process leads to deeper understanding of the data and the researched space. Each time I write and then return to my data to reread, I am forced to consider what stories are important to tell, what themes are emerging, and how I am interpreting the data. The three narrative versions presented here demonstrate that “as the writing of texts progresses, form changes and grows,” (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000, p. 148), and this process leads to greater academic insight: the ongoing process of becoming a narrative researcher.