Articles

Exploring the Rhizomal Self1

Theories of the Self abound both across and within disciplines. Following a discussion of two frameworks for understanding the Self—the essentialist and the dialogic—we explore the nature of what we call the rhizomal Self. Through autobiographical material we present a rhizomal narrative as a means of understanding the Self as narrative performance. We conclude with a brief discussion of some of the advantages of this way of conceptualizing and representing the Self.

1 There is much written about the relationship between narrative and the Self, and also much on the notion of narrative as performance. These two aspects of narrative discourse together raise some important questions for those of us who are attempting to explore issues pertaining to the Self. Do they suggest that there is a life, a Self, separate from the performance, and that performance is a more or less accurate representation of that life? Or is the life, the Self, constituted in and/or by the performance, having no other reality than that which exists while it is being performed? And in either case, what is the nature of the Self being performed? We come to these questions not primarily from a desire to philosophize (though we will be engaging in such throughout this article) but from a professional concern with the implications of possible answers to these questions. We are social workers, one newly qualified, the other of some years standing, now teaching social work. Understanding individuals in context is the essence of our chosen profession. How we understand individuals, their lives, and their identities makes a significant difference to our assessment procedures, our interventions, our evaluations of circumstances and behaviours and, of course, our relationships with service users. This paper is not, however, an article primarily about the concerns of social work, but an exploration of a particular way of understanding the Self that we believe may be of interest to narrative scholars.

2 In essence, our argument is that we need to develop a way of conceptualizing and re-presenting the Self that addresses some of the philosophical, cultural, and representational failings of two foregrounded frameworks for understanding the Self: the essentialist Self and the relational or dialogical Self. These failings, we argue, can be addressed well, although perhaps not entirely, through a rhizomal narrative framework of the Self, incorporating insights from the every growing field of narrative and the philosophy of Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. The way we will develop our argument is thus. Following some introductory remarks we will outline the two frameworks of the Self that we take issue with (the essentialist and the dialogical), indicating the problems we see in each. We will then outline what we call the rhizomal Self, a Self that is de-centred, multiplicitous, fluid, and, in Deleuzo-Guattarian terms, nomadic. In the following section we attempt to illustrate this rhizomal Self using autobiographical material, primarily from one of us (CH). Finally, we will discuss some further features of the rhizomal Self and indicate some of the areas in which further work is required.

A Narrative Understanding of the Self

3 The extensive and expansive literature on the relationship between narrative and the Self that cuts across disciplines such as philosophy (MacIntyre, 1984; Taylor, 1989; Ricoeur, 1991; Strawson, 2004; Currie, 2010); the social sciences (Somers, 1994; Day Sclater, 1998; Guerrero, 2011); psychology (Bruner, 1987, 2006; Schechtman, 1997; McAdams, 2006, 2008); and literature (Eakin, 1999, 2008; Vice, 2003; Snaevarr, 2007) falls, we think, along a spectrum at one end of which there are those authors who see narrative as reflecting, or as a window upon, a Self that exists prior to, and independently of, that narrative and at the other end of which we have narrative as constitutive of the Self, that is the view that without narrative there is no Self to understand (Schechtman, 1996). Wherever along this spectrum one takes a position, narrative can be seen as being relevant to understanding the Self because, like the Self, it requires agency and opportunity to be realized. As such, narrative (and thus the Self) can be seen as performative regardless of whether one sees the Self as a unified, singular whole as in the essentialist position, or the decentred, multiplicity of the dialogical position.

The Essentialist Self

4 The essentialist Self is the Self that, starting with Augustine’s invention of the “inner self” (Cary, 2003), developed through a range of practices in the 11th and 12th centuries, (Morris, 1987), was formulated more rigorously by philosophers such as Descartes in the “I” of cogito ergo sum and Locke (1836) as “a thinking, intelligent being, that has reason and reflection, and can consider itself, as itself, the same thinking thing in different times and places” (p. 225). The essentialist Self found its resting place in modernist psychology as a being with frontiers, separate from others, with its own distinct personality, beliefs, and attitudes, that encapsulates the idea of continuity in that the Self at time t1 is, at least in most significant respects, the same as the Self at time t2. It is a Self that can be considered as a centred, individual subject that can be known “as a bounded, unique individual, more or less integrated motivational and cognitive universe; a dynamic center of awareness, emotion, judgment, and action organized into a distinctive whole and set contrastively both against other such wholes and against a social and natural background” (Geertz, 1974, p. 1). This is also the autonomous, stable, unified, and coherent Self of Western liberalism, discussed by St. Pierre (1997), that frames individuals within a socio-legal discourse of rights and citizenship and which holds individuals accountable for past actions. For example, “this is the individual who abused this child and this Self and no other should be held responsible” or that “it is I and no other Self that should receive credit or compensation for my sacrifice and service” (see Schechtman, 1996). This is the sense of Self that lies implicit when people say of their relative with dementia, “Oh, he’s not the person he was,” or “She’s not the woman I married.”

5 This understanding of the Self is, we suggest, an example of a “line of articulation” that frames an individual through three strata: organism, significance, and subjectification. The first, organism, points to the necessity to be organized as a body; the second, significance, to being interpreted through hierarchical language; the third, subjectification, to the requirement to become a clearly identifiable, singular self. (See Markula, 2006, for a discussion of these strata.) Through the process of articulation the individual is framed/constructed as conforming to the demands and expectations of ordered classifications, themselves linear, fixed, hierarchical/vertical, and deeply rooted (“arborescent,” in Deleuzo-Guattarian terms), as found, for example, in terms such as the “good employee,” the “effective manager,” or, in social work, the “rogue” or “dangerous” mother (see Bergeron, 1996, on this last articulation).

6 While this understanding of the Self may be widespread and even common-sensical, it is problematic in a number of ways. First, there are problems with the notion of psychological continuity that is fundamental to this view of the Self (see Schechtman, 1996). Second, given that humans are social beings, it seems to have little to say about how ongoing interactions with others shape the Self. Ongoing, everyday interactions appear to be simply meetings of already-formed Selves that react to other Selves in particular ways. It is thus a somewhat atomistic notion of the Self and one in which there seems to be little, if any, room for fundamental change, ongoing formation, or becoming through interactions with others. This stability or fixity does not sit well with the therapeutic aims of social work: helping people to change, to become different. Third, it allows for individuals to be excluded from the status of personhood, depending on the criteria used; see for example, Brock (1993), who excludes individuals with severe dementia from the “personhood club”: “The dementia that destroys memory in the severely demented destroys their capacities to forge links across time that establish a sense of personal identity across time. Hence, they lack personhood” (p. 373).

The Dialogical Self

7 If the essentialist Self forms one end of a spectrum of positions to be taken on what constitutes the Self, at the other end is the relational or dialogical Self, that perceives the Self in a more social and fluid fashion. This is the decentred, social Self that we find in authors such as Salgado and Clegg (2011), who note that “Self-identity becomes a matter of socially situating oneself and negotiating with others one’s own identity—the fixed self becomes fluid, socially constituted, and unstable” (p. 424). Having no central “I” to control or coordinate multiple aspects of an independent Self, the subject is viewed as multiple “I’s” each with its own voice, position, and worldview. These “I’s” may compete or conflict with one another and the Self is thus, in Bakhtin’s terms, polyphonous, having a “multiplicity of worlds, with each world having its own author telling a story relatively independent of the authors of the other worlds” (Hermans, Kempen, & van Loon, 1992, p.28). In the example in the second part of this paper, it is thus possible to see such multiplicity (on a limited scale) in the “military” and “social work” selves. Further, the Self is embodied and shaped by social relations, the dialogical Self being understood as expressing “the juxtaposition of personally experienced social corporeality” which “grants us a richer role of sociality beyond that of intersubjective exchange” (Cresswell & Baerveldt, 2011, p. 272). In other words, we are continually shaped in our interactions with others, the Self being thoroughly contextual. For us, as social workers, the continual performance of Self in relation to individual, communal, institutional, political, economic, cultural, and societal contexts is the essence of our work, aiding others to negotiate a livable Self materially, psychologically, socially, and spiritually.

8 There are, however, limitations to this framework. The emphasis on the socially constructed Self seems to place the Self entirely at the mercy of social context without allocating it any agentive capacity. An extreme version of this would be represented by Woody Allen’s character Zelig (Allen, 1983), who morphs into the body types, speech patterns and behaviours of people around him — quite literally embodying all of his social interactions and relationships.

9 The problem with the dialogical Self thus conceived is how to allow for agentivity in Self construction—the Self being a performance but not a puppet. Again, agentivity is important to social work, as it seeks to empower, to promote independence, and to enable people to fashion, create, invent, and discover for themselves ways of being in the world.

The Rhizomal Self

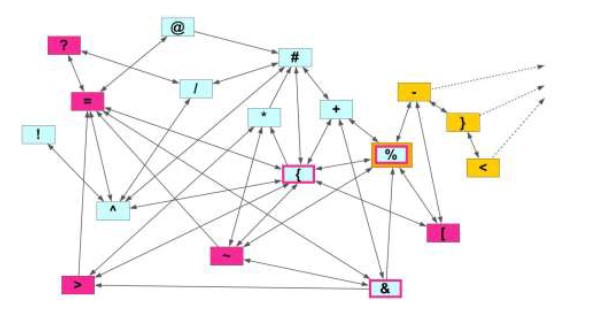

10 One way of envisioning the Self that avoids both the rigidity and asociality of the essentialist Self and the passive, ineluctable malleability of the dialogic Self is as a rhizome, an interconnected collection of nodes or narratives spread horizontally across time and space without predefined shape or direction (see Figure 1). The rhizomal Self defies subjectification, the requirement for a clearly defined singular identity. Multiplicity, multi-vocality, discontinuity and fragmentation can all be accommodated within the rhizomal narrative—the Self being compared to “a buzzing beehive so agile and inconsistent, we can barely keep track of it” (Rosseel, 2001, p.127, cited in Sermijn, Devlieger, & Loots, 2008, p. 637). In the rhizomal Self, the nodes, consisting of individual narratives, narrative fragments or traces, capture something of what it is to be that individual, but neither define the individual nor form resting points at which we can claim an understanding of “who that person is.” Rather, they are passage points for what Deleuze and Guattari (1987) call “lines of flight.” Lines of flight seek to make connections, to deterritorialize or disrupt unity and coherence and thus open up possibilities for becoming “other.” It is therefore the pathways between nodes that shape the Self in time and context. The Self, forever on the move between nodes, is thus nomadic. In this way, the rhizomal framework of Self captures agentivity in that the movement between nodes can be purposeful and meaningful, yet also highly social because the direction of movement is influenced but not determined by others and context. Such lines of flight can be seen in the contestation of essentialist and heteronormative categories of identity within queer and crip theory discussed by McRuer (2006) or the experimentations of Australian performance artist Stelarc (2012), who challenges notions of fixedness in arborescent thinking by breaking down traditional conceptualizations of the unity and stability of the body through performances such as his third mechanical arm project or the grafting of a third ear onto his arm. For social workers, such heterogeneity sits well with the commitment to cultural diversity, the uniqueness of the individual, the promotion of empowerment, and so on.

11 While the rhizomal, nomadic Self has, we think, certain advantages over the essentialist and dialogic frameworks, we still need to find a way of representing that Self that is understandable and it is to this we turn in the next section where we present autobiographical material in rhizomal form.

Performing the Rhizomal Self

12 In order to illustrate this notion of the Self, we here present a rhizomal narrative, simplified in terms of the number of nodes and possible connections (real-life rhizomes being far more complex and fluid). Figure 1 presents the rhizome visually so that the reader may have a sense of how nodes can be linked, though ideally the shape and structure of the rhizome would remain unknown (see the discussion section).

13 We have endeavoured, within the constraints of a linear text, rather than a hypertext, to present this rhizome as an interactive narrative, at once a performance by [CH] presenting aspects of her life in a flexible, decentred, constitutive, nomadic way and the reader who, in choosing possible pathways, has the text perform according to the choices made. Nodes, each represented by a symbol such as #, %, * and so on, capture personal, familial, communal, societal or discoursal passage points or narratives through which the reader can follow and come to know the author [CH]. Each node carries a symbol rather than a number or letter so as to avoid the suggestion that there is a preferred starting point for entering the rhizome or a preferred pathway once in it. The rhizome is designed with the modest intention of demonstrating possible tensions and convergences between the military and social work selves and can be read in a number of ways. First, one might read it through as it appears just as one might read a more traditional autobiography. This would provide one understanding of [CH]. Alternatively, the reader may start with the first section and then move to other sections as indicated by the symbols following the text (it is possible to move from one section to another by clicking on the symbol), creating a pathway along which another understanding of [CH] emerges. Or, again, one might start at any node, and move along a pathway of one’s own choosing. Alternatively, it is possible to access each node in whatever order one chooses. Each of these approaches will constitute a new narrative performance, and thus a different understanding, of [CH].

The Rhizomal Narrative

14

My swearing-in ceremony was a fancy affair, a one-off public affairs stunt aimed at garnering support for an increasingly unpopular military. Most new military members attend a quiet reception at their local barracks or armoury; I was sworn in with hundreds of other new recruits by the Minister of National Defence, Chief of Defence Staff, and Prime Minister of Canada at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. We were served a full-course dinner on white tablecloths. Dignitaries toasted our patriotism and loyalty to our country. Entertainment included a demonstration of rappelling techniques from a squadron of helicopters flying overhead. Other than commending the bravery of the troops, there was little mention of the Canadian military mission in Afghanistan. # > ~

15

I graduated from Basic Military Qualification (BMQ) training on a Friday afternoon, ranked third in my class of 58 recruits. We were a mix of regular and reserve force army, navy, and air force members. Women were outnumbered 4:1. Of the five highest-ranked graduates, three were women; my roommate was also awarded the top shot prize for highest shooting accuracy on the range. My female platoon mates and I thrived in the adrenaline- and testosterone-fuelled environment and we never let anyone question our capability as soldiers-in-training. We all had different reasons for joining the military— adventure, travel, rebellion, money. Basic training was a summer-long mind game, instructor vs. recruit. I did well because I refused to take all of the military rah-rah seriously. When I giggled in the ranks, I completed my prescribed push-ups without complaint, but no punishment could stop me from smiling gleefully up at the drill commander as he screamed “Ordinary Seaman Hill, why are you so goddamn happy to be here?” I was seventeen years old, living away from home, making tons of new friends, and being paid a heck of a lot of money to do it. It was like summer camp for physically fit adults, and it was a blast. / ^ + {

16

Here I am (left) with a friend in the field phase of my Basic Military Qualification course. # ^ ?

17

Excerpt from Letter to the Editor:

18

I wrote this letter to the editor in response to an article I read describing a “die-in” protest of military recruitment on my university campus. I felt that the article was very one sided, and as a member of the military and a student, I wished to contribute to the discussion. This seems like a straightforward process, and it would have been for any civilian writing to a public newspaper. However, as a military member, I was required to have my letter vetted by the Canadian Forces public affairs section. I submitted my letter to my military unit, who in turn sent it on to the area public affairs representative. This entire process took several weeks. Even though a letter to the editor clearly reflects the opinion of the submitter, military members are not permitted to publicly comment on the military without express permission from Canadian Forces public affairs. In a world where words are constantly reinterpreted by the press and the public, the military is incredibly cautious about public and media scrutiny. ^

19

My grandfather passed away the day before my ship sailed for a deployment to Bermuda and the Eastern Seaboard. He had been shipped off to war at 21 years of age, the same age I was when he died. I sent him letters every summer detailing my adventures with the Navy. When he passed away, I was on the other side of the world, thousands of miles away and unable to attend the funeral. Instead, I sent him one final letter: When I was little I used to sit on your knee and ask you to tell me the longest story in the world—you would recount stories of your days in the Navy, postings all over the Continent and throughout the Middle East, languages learned and sites seen. I know now that you must have been filtering your stories carefully for my young ears, leaving out the horrors of war and replacing them with the beauty that you managed to see amidst the destruction. My grandmother told me after his death that he had rarely discussed the war with anyone. # & { %

20

When I moved to New Brunswick and enrolled in my social work degree, I transferred from the Naval Reserve unit in Montreal to the Naval Reserve unit in Saint John. As a reservist, I continue to work one night per week and over some weekends when I am not under long-term contract. For me, this has always meant that I work part time for the military during the school year, and dedicate the summer months to full-time employment as a sailor. # =

21

He was a Corporal in the infantry, a gambler trying to kick the habit before his late summer wedding. His fiancée was not aware of his expensive hobby. He had been deployed to Afghanistan twice and was expecting a third deployment in the New Year. We worked our way through the Addictions intake sheet quickly, chatting easily about his background. I [CH] asked him if he had ever received counseling services in the past; he replied that he had. I asked him if he would be able to elaborate. He spoke of the deaths of six friends in the same roadside attack. They were in his battalion; he was lucky to be alive. He lost his roommate and suffered from severe nightmares and flashbacks for years after. His grief counselor used exposure therapy, made him watch movies that reminded him of his dead roommate. I sat in front of him, speechless. He was only a year or two older than me. I felt like a child play-acting at an adult’s very important job. * = {

22

They will not be the same; for they’ll have fought

In a just cause…”

“We’re none of us the same!” the boys reply

“For George lost both his legs; and Bill’s stone blind; …

“And Bert’s gone syphilitic; you’ll not find

“A chap who’s served that hasn’t found some change.”

(Siegfried Sassoon, “They,” 1917/1984) + > ~ = %

23

My supervisor had been working with him for months, and we had tracked his case at our weekly Mental Health meetings. She was distraught at his suicide; they grew up in the same small community and she knew his family. A memorial service was held at the base; the father called out to his son’s former co-workers, begging them to seek help for post-traumatic symptoms so often pushed aside. The family called for a “Highway of Heroes” to bring him home, asking only that he be given the same honour as soldiers killed in combat. Later, talking to a number of reporters, his father repeated the same line over and over: “He may not have been killed in Afghanistan, but Afghanistan is what killed him.” * & = { %

24

My decision to undertake a student placement at the local forces’ base was rooted in my desire to merge my military role with my social work role. The reality of working for the army element of the military was very different from my own experience in the navy. Real war is ugly, and it does not end when soldiers return home. I was not prepared for the inconceivable pain experienced by many of the soldiers and their families. At times I felt ill-equipped to handle my new role. My supervisors were experienced and truly incredible in their respective roles. They provided me with guidance and always seemed to have the best interests of their clients at heart. I eventually realized that even that could not prevent the inevitable tragedies that occur in this line of work. At the mental health clinic, the military tagline, “If the soldier isn’t deployable, he’s not employable,” is law. Social work confidentiality rules (harm to self, harm to others) go out the window; the social work officer is first and foremost a military officer, and illicit behaviours such as drug and alcohol misuse may be reported to the client’s commanding officer. The responsibility to the client is replaced by the responsibility of keeping the military machine running as smoothly as possible. Over the course of my placement, I realized that I could not function as a military social work officer within this system because I would never be willing to compromise my professional ethics for the sake of the military institution. By the end of my three months at the base, it was clear to me that my social work identity was slowly replacing my military identity. ^ @ & ? {

25

Here I am (left) riding in a troop carrier with my social work placement supervisor. We were on our way to visit troops conducting a week-long exercise in the field. When we arrived in the training area, it was windy, freezing cold, and pouring rain. It was not lost on me that if I were taking part in the exercise as a military member rather than visiting as a social work intern, I would not be returning to the comfort of a heated vehicle and a cozy bed at the end of the day. Instead, I would have another week of wind and rain to look forward to, hunkered down in my dugout trying to stay warm, far from the comforts of home. = /

26

I stand on the parade square in a packed arena. I am in the front row, dead center. My uniform is pressed, my boots are shined, and my hair is in a tight bun at the nape of my neck. As the drillmaster orders us to stand at ease, the opening strains of “Amazing Grace” begin to play. The first wreath is laid on the cenotaph, borne by an elderly veteran who walks slowly and carefully with the assistance of a cane. I think of my grandfather, and feel tears well up in my eyes. I will myself to keep it together. There are thousands of people watching; television crews cross back and forth in front of our platoon. I stare directly ahead, focusing on the shine of the parade commander’s boots, the light sprinkling of dandruff lingering on our platoon officer’s shoulders, the dull ache of my feet in my flat-bottomed parade boots—anything to keep my mind occupied. The next wreath is laid by a veteran of our modern era of conflict. He walks toward the cenotaph clutching the hand of a young girl, who I imagine must be his daughter. She wears a sparkly dress and a ribbon in her hair. I think of my former clients, broken and lost upon returning home from the deadly desert. It is not the deployment that breaks them, but the return home to normalcy. They are no longer normal. Tears start to slide slowly down my cheeks. I feel one trickle into my ear. I clench my fists at my sides, digging my fingernails into my palms. I lock my knees, then unlock them, then lock them again. I bite the inside of my cheek. I try to prevent the inevitable. The procession of veterans and mourners continues, laying wreath after wreath on the simple stone cenotaph. As the bugler begins “The Last Post,” we stand at attention and our platoon officer raises his right hand in a strong salute. Across the parade square, a WW2 veteran comes to attention and struggles to raise his right hand to his brow. He holds his salute for a few seconds, until the intense shaking of his arm forces him to lower it down to his side. After a few moments, he tries again. Up and down, up and down, he tries so hard but his body is not as strong as it was once. The last mournful notes echo in the large arena. Tears are streaming down my cheeks, my nose is running, my composure completely lost. A thousand thoughts compete for space in my head. * # + > ~ = % [

27

I] think of Siegfried Sassoon’s (1947/1984) poem, “At the Cenotaph”:

Standing bare-headed by the Cenotaph….

“Make them forget, O Lord, what this Memorial

Means; their discredited ideas revive; …

Lift up their hearts in large destructive lust; …

The Prince of Darkness to the Cenotaph

Bowed. As he walked away I heard him laugh. + ~ { [ -

28

The first time I heard Sassoon’s poem, “At the Cenotaph,” I was in my narrative social work class. CB was the instructor, and he presented a slide with the text of the poem, giving us several minutes to read and consider Sassoon’s words. I remember being blown away by the mixed emotions invoked by this poem. The idea of forgetting those killed in war, of forgetting the veterans we continue to thank so adamantly for their service year after year, was shocking to me. At the same time, it occurred to me that this would be a small price to pay for a world that knows only peace, so much so that a war memorial loses all meaning and significance. The following day was Remembrance Day. { % -

29

I [CB] first heard Sassoon’s poem in Mr. Emmett’s English class. As a bored teenager I wasn’t enamoured with the war poets and following the exam I promptly forgot about it. But some years later, seeing Margaret Thatcher, the then prime minister and architect of the Falklands war, standing at the Cenotaph, the first line was disinterred from the depths of memory: “I saw the Prince of Darkness, with his Staff.” Sassoon may have had the gender wrong, but his poem was prescient. % [ }

30

As far as I [CB] remember, I was against war, all wars, long before I understood what it meant to be a pacifist. I was involved in, or a member of, all sorts of organizations in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the Campaign Against the Arms Trade, the Peace Tax Campaign (now Conscience), Christian Movement for Peace and could make the intellectual links between peace issues and international development, peace and justice, and (contra Aquinas’ theological arguments for the Just War) between “pacifism” and faith. But it was Utah Phillips (1993), recounting the words of Ammon Hennacy, that struck home: “You came into the world armed to the teeth. With an arsenal of weapons, weapons of privilege, economic privilege, sexual privilege, racial privilege. You want to be a pacifist, you’re not just going to have to give up guns, knives, clubs, hard, angry words, you are going to have lay down the weapons of privilege and go into the world completely disarmed.” (I do not know where I first heard these words, but they are to be found on Utah Phillips’ album, I’ve Got To Know). And, as with Utah Phillips, I find it a constant struggle. - <

31

I [CB] have always had a fondness for the Industrial Workers of the World, the Wobblies, what I once heard referred to as the smallest mass movement in the world. Joe Hill’s songs, the stories of Utah Phillips—their passion resonate with my desire for a better world and their tragedies encapsulate the difficulties of achieving it. }

Discussion

32 This way of conceptualizing the Self—as a rhizomal narrative— has, we believe, advantages over both the essentialist and the dialogical frameworks of the Self. The notion of the narrative Self has been constructed in a number of ways that, at times, can be conflicting and confusing (Smith & Sparkes, 2008). Smith and Sparkes (2008) provide a typology for viewing and understanding the varied conceptualizations of the Self by presenting five perspectives (the psychosocial, the inter-subjective, the storied resource, the dialogic, and the performative) along a continuum. The notion of the rhizomal Self adds a sixth conceptualization of the narrative Self and in the future it would be beneficial and illuminating to explore how and where the rhizomal Self fits on the continuum (Smith & Sparkes, 2008).

33 Ideally, the rhizomal Self should be presented as hypertext so that the reader has neither a map of the rhizome nor access to all nodes. We have presented the rhizome, both map and content, here as a means to illustrate how the rhizomal Self might work as a framework for understanding an individual in context. We ask the reader for the rest of the discussion to imagine how the above text might appear in hypertext form, with the reader having access to the present node and the links from that node and without knowledge of the shape or extent of the rhizome as a whole. Further, having read the text, in whatever way chosen, we now invite you to return to it and reread it in other ways, choosing different pathways, and keeping in mind how this (second, third or fourth) reading is different from previous ones.

34 One advantage of this hypertextual way of reading the autobiographical material is that it reflects in some ways the way we come to know others. Most of our interactions with others start part way through their lives and we come to know them through our interactions with them, interactions that are dependent upon the situation, our interpretations of what they tell us, their choices regarding self-disclosure, choices themselves dependent upon context and how they regard us. In other words, coming to know someone is not the linear process of a traditional autobiography but a piecing together of fragments from which we take out clues from what is disclosed as to which pathways to follow.

35 Another advantage with this way of visualising the Self is that, with the author establishing possible pathways between nodes, the framework extends the agentivity of the dialogical Self, through control over how access to nodes is granted, while, on the other hand, allowing for the reader to participate in the construction of the autobiography through the choices of pathway to be followed. The Self thus becomes a dynamic between the author and the reader that captures both agentivity and sociality.

36 Further, there is the possibility of including pointers to other narratives, thus illustrating how our lives touch on, and are touched by, those of others. In our example, these are represented by the nodes that form part of CH’s rhizome (blue and red) and part of CB’s rhizome (yellow). In this way our individual stories become part of each other’s rhizome—a further capturing of the social Self.

37 At the same time, this rhizomal approach can accommodate the notion of central stories—that is, stories that are highly connected with other stories. In our example above, the nodes =, {, and ^ are examples of this. Taking the notion of centrality from social network analysis, we can view such central stories as either locally central—that is, it is connected with many stories in its local environment—or globally central in that it holds a “position of strategic significance in the overall structure of the network” (Scott, 1991, p. 85). Therefore, such stories can be viewed as being more central to understanding the individual than others, though not in and of themselves capturing any essentialist Self as such stories are simply well-connected passage points in multiple lines of flight.

38 In addition, the framework allows for separate Selves (illustrated above in the military and social work selves, themselves represented by the blue and red nodes respectively) to exist alongside each other, capturing a sense of multiplicity. For example, if one followed the pathway @ * # ^ ! / (the blue nodes in Figure 1) one would understand CH in primarily a military context; if alternatively, one followed ~ > = ? (the red nodes) it is the social work self that is foregrounded. The two pathways set apart the two Selves and it might be the case that, depending on the pathway followed the reader might have no knowledge of the other Self. The rhizomal framework, however, does allow for connections to be made between different Selves, as illustrated in Figure 1). These are points in lives where multiple Selves touch upon one another. In this way, complex configurations of the Self are possible within a rhizomal narrative that are less easily available in traditional linear ways of presenting autobiographies.

39 Consequently, adopting a rhizomal Self theoretical approach to frontline social work is particularly beneficial for service users for a number of reasons. A rhizomal Self approach gives the service user more control; it does not see individuals as “fixed” by particular challenges or concerns; it is more creative, allowing for multiple pathways of understanding; it challenges the dominant medical model, allowing for more empowering outcomes; and it fits well with anti-oppressive practice. For example, for individuals living with body integrity identity disorder (BIID), the lines of articulations are often psychiatry, medical, unethical, crazy, evil, etc. With a rhizomal Self approach, BIID can be understood by various lines of fligh,t such as pretending, second life, freedom, amputating your own leg, etc. In this way, we see there is not any one way to live with BIID.

40 Finally, the rhizomal Self presented above is inherently unstable and transient. Each reading constitutes a different Self depending upon the pathway taken. Thus, in our example above, how we understand ({), standing at the cenotaph,depends at least in part, on whether we have first read (%), the Sassoon poem. Is the reflection at the cenotaph prompted by the poem or does the poem have personal significance only following the reflection? This interpretative uncertainty is part and parcel of understanding others.

41 These advantages, we think, are enough to warrant further exploration of the possibilities of the rhizomal Self. Such explorations could take the form of rhizomal autobiographies, experiments with hypertext, theoretical musings on the nature of rhizomal narratives, or the application of the framework in a range of settings (for example, social work assessments). We offer such possibilities in the hope that this paper, as a node in our rhizome, will be taken up as a link to those of others.