Articles

Life Tree Drawings as a Methodological Approach in Young Adults’ Life Stories during Cancer Remission1

This paper introduces a methodological approach that was utilized when the textual material and life tree drawings of young adults with cancer were analyzed as an interwoven ensemble. In order to take the visuals seriously, the article focuses on visual narrative analysis in order to give a clear description of how the drawings were analyzed as narratives. New insights are gained when the analysis process is introduced step by step as a genuine combination of narrative textual and visual analysis. Finally, the drawings reveal new layers of experiences in a form of metaphors that reflect support, self, body, and time.

1 Autobiographical interviews and life tree drawings from sixteen young adults with cancer were gathered after their cancer treatments. The participants’ ages varied between 18 and 34; this was based on an official age limit given by the Finnish Cancer Society that defines young patients as being between 18 and 35 years of age (Sonninen, 2012). Earlier studies indicate that young adults are coping poorly with cancer diagnosis (e.g. Kyngäs, Jämsä, Mikkonen, Nousiainen, Rytilahti, Seppänen, et al., 2000; Grinyer, 2007; Zebrack, 2011). The focus of this research is to understand how cancer impacts the patient from the perspective of one’s life story, how coping is described, and if there is a role for religion in the life stories of young adults.

2 The original source of methodological inspiration was my earlier research in which I gained important insights using a holistic analysis of a form of the plot (Saarelainen, 2009). Lieblich (1998) commented that when analyzing life stories, the form of the plot must be noted in order to avoid accidental exclusions of important information. Work by Riessman (2008), Luttrell (2003), and Tamboukou (2010) was found beneficial when trying to answer the question, “With what kind of form can a life story be expressed?” This article evaluates from a wide perspective life tree drawings as a methodological selection, at the same time describing in detail how the visual analysis was conducted.

3 The visual narrative inquiry is a construction process in which the participant and researcher examine the meaning of the experience together. This work includes both visual and narrative elements, and deals with the participant’s emotional involvement in the experience (Bach, 2008). Keats (2009) observes that visual elements are particularly helpful in situations where it is expected that the informants may have difficulty expressing their feelings. Several benefits of using visuals as a part of research have been reported (see Pain, 2012; Weber, 2008).

Recruiting and Interviewing the Participants

4 The participants were invited to take part in the research through webpages and chat rooms hosted by the Finnish Cancer Society. As well, some were invited through the email list of a support association. The time between the treatments and the interview varied from several weeks to five years. I did not require a particular type of cancer or religious affiliation. Most of the participants had been diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease but the spreading of the cancer varied greatly. Most were studying in a professional program at the time the cancer occurred. Before the diagnosis, they were living on their own or with a partner or friend. A few were still adolescents and living with their parents when diagnosed. All described living independent lives to some extent before the cancer. One had children and one was pregnant at the time of her interview. Twelve of the participants were females and four were males.

5 The interviews were mainly conducted between October 2011 and March 2012. One respondent wanted to participate shortly after being diagnosed, so she was interviewed for the first time during treatment and the second time in December 2012. The participants were given an opportunity to select the interviews’ location. The interviews were conducted in restaurants or cafeterias, as well as the facilities of universities and the cancer association. On one occasion, the interview was held at a participant’s home. Three of the participants were writing a blog about their cancer experiences. These blogs were given to me as research material, and I am utilizing those that had been written by the end of 2012. In addition, one of the interviewees had earlier (2008) written a letter about her experiences with cancer, as she had participated in my earlier research (Saarelainen, 2009). This textual material (blogs and letter) was analyzed alongside the interviews.

6 At the beginning of the interviews, their rights as interviewees and my responsibilities as a researcher were explained to the participants. At the end of the interviews, the participants were given a written explanation of their rights, and were asked if they understood it and if they were they willing to let their drawings and interviews be used for academic purposes and as teaching material. All participants wished to continue in the research project and submitted their drawings for this purpose.

7 The actual interviews began with the drawing task. A simple instruction was repeated in every interview: “I ask you to think about your life, thus far, as a tree. What does your tree look like?” They were given an A4 sheet of paper and a black marker. Other markers (purple, blue, brown, yellow, orange, red, pink, light green, and dark green) were placed on the table. Some participants asked for more information or commented that they were not artistic. They were told that “You can draw it the way you see it. There is no right or wrong way.” Some began to spontaneously explain what they were drawing and how things were related. When they were asked, “Where would you like to start?” cancer was usually selected as the first subject to talk about. If a tree narrative did not appear, they were asked “Can you please explain the picture and what is in it?” Some used the drawing as a tool to relate their life stories, a few continued to work on the drawings while narrating their life situations, and some did not refer to the trees at any later point of the interview. Still, all were asked how the components of the trees were related, and to explain the meaning of the various signs and symbols.

Selecting the Tree

8 With sensitive research topics, the use of drawings has been found helpful, and has encouraged participants to speak about their experiences (e.g., Lev-Wiesel & Liraz, 2007; Katz & Hamama, 2013). The original idea was to use life lines as a drawing task for the participants. Life lines are a workable approach when researching sensitive topics (Guenette & Marshall, 2009). In addition, timelining is considered to produce rich data, especially in narrative research (Sheridan, Chamberlain, & Dupuis, 2011). After careful consideration, some ethical questions emerged. It did not seem right to ask young adults who had finished their cancer treatment to imagine their lives as a line, since the end of the line could easily be associated with the end of life.

9 Multiple visual tasks were considered, such as drawing a cartoon based on one’s life. With a cartoon, one would have to depict certain people and incidents, and show links between events. It seemed difficult to evaluate the impact of cancer from the perspective of a life story presented in a cartoon. Asking the participant to simply “draw your life/life story” was also considered, but this could have been too confusing without prior information being given to the participants. Still, it would have been fascinating to see the kinds of drawings and stories that would have had appeared. Self-portraits with finger paintings, crayons, and watercolors were considered but not used, as they were felt to be too messy and difficult to do effectively.

10 The Tree of Life (ToL) is grounded in narrative practice and designed to assist in talking about difficult matters. Although the original technique offers a tool for group interventions, trees as a form of life and means of expressing difficult experiences were found intriguing. I decided to use open instructions for drawing the trees, since the specific ToL guidelines felt too instructional. (For more about ToL, see Byrne, Warren, Joof, Johanson, Casimir, Hinds et al., 2011; Loubser & Müller, 2011; German, 2013; Hughes, 2014; Tree of Life, 2014). It was recognized that the interviews would be conducted for research rather than therapeutic purposes.

11 Although the approach of using freehand drawings of a life tree within the context of a narrative research interview is seemingly a rare and novel one, German (2013) and Hughes (2014) have reported positively when using interviews with ToL. Furthermore, the Theme Tree Method (TTM) involves tree painting as a creative activity when the interviews are seen as giving the actual data. When TTM data have been analyzed, storytelling and paintings were found to be so intertwined that these two narrative forms of life description were difficult to distinguish from one another (Gunnarson, Jansson & Eklund, 2006; Gunnarson, Peterson, Leufstadius, Jansson & Eklund, 2010).

12 The shape of a tree for an autobiographical drawing can be discussed from several perspectives. It must be admitted that the tree as a metaphor of life is old and common. It recalls images of family trees and other similar things. Many biblical parables involve trees. Further, trees in nature have certain well-known parts, like roots, trunk, branches, and leaves, and they tend to grow. Thus, recognizing a tree as a shape makes the drawing task easier to master for participants. As Morris (1995) noted, trees can be seen as mythological and religious symbols but also as metaphors of an individual’s personality. Metaphors help us to comprehend the surrounding world and ourselves in a unique way. They are vital to understanding our worldviews, our deepest emotions, and our imagination. Metaphors exist in ordinary language, but help us to apprehend abstract ideas concerning life, death, and time (Lakoff and Turner, 1989).

13 Before I began to gather the data, I was unsure how the drawings would be handled or if only the narration would be analyzed. The first interviewee designed her tree carefully, and described her selection of colors and symbols. She depicted her cold feelings towards her parents and childhood with blue leaves and intentionally left the roots out. The coloring of the leaves changed to red and pink when she met her husband. Cancer was pictured as scars on the tree’s trunk and as black leaves. After five years she still felt that cancer was impacting her life, and she did not want to draw the top of the tree that would have represented her future. Her way of using the drawing convinced me that somehow the drawings must be treated as equal to storytelling. Given Tamboukou’s (2010) assertion that in order to understand self-images, it is not enough to juxtapose visual images and narratives, this meant that I needed to find analysis methods which would complement both the visual analysis of the drawings and narrative approach of the data analysis.

Mapping Myself within Narrative Theories and Visual Narrative Analysis

14 My understanding is that people are storytellers and that an identity is built by telling stories. In other words, my research task considers cancer’s impact on narrative identity. The research is focused on “what” was said, rather than “how” (see Riessman, 2008). Originally, my interest arose from a “big story” approach. I postulated that narratives are formed as coherent life stories which include a beginning, middle, and end (e.g., McAdams, 1988, 2008, 2009; Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, 1998). The shape of a tree was selected as a tool to examine coherent life stories.

15 I noticed that the storytelling included material that is not easy to define in terms of coherence, such as a clear plot line. Sartwell (2000) noted that coherence and narrative identity are combined together. As he states, “If I lose the thread of the story I was telling ... then there is no me” (p. 43). He strongly criticizes our obsession about language and forced orientation towards telos (orig. Greek “τέλος”: end, purpose, goal). As well, incoherent narrations were important when attempting to understand the young adults’ stories and their relations in them. I became aware of the importance of small stories, and their impact on storytelling and identity formation (e.g., Bamberg 2011a, 2011b; Bamberg & Georgakopoulou, 2008). Andrews (2010) notes that when people undergo a traumatic experience, it might be difficult to express it as a coherent unity.

16 Although the perspectives of “big” and “small” can be seen as opposites, I find my textual data to be in between: the data include both. Practically, this means that the unit of analysis is a life story formed from big and small stories. Freeman (2011) summarizes the possibilities of uniting the approaches as follows: a “truly synthetic, dialectic endeavor in which the multiple orders of time and being, practice and reflection that characterize the life of experience find a suitable home” (p. 120; see also Freeman, 2010).

17 When using the term “life story,” I am referring to the participant’s description of his/her story of life as a whole. It includes both coherent stories and fragments of narrations. This definition of a life story helps in understanding people in crisis; their stories can be evaluated as a whole, even if a coherent meaning for cancer has not presented itself. The stories of the young adults showed that some found a meaning for the cancer, some were struggling to find a meaning, and some thought that there could not be a meaning in it (Saarilainen, in press).

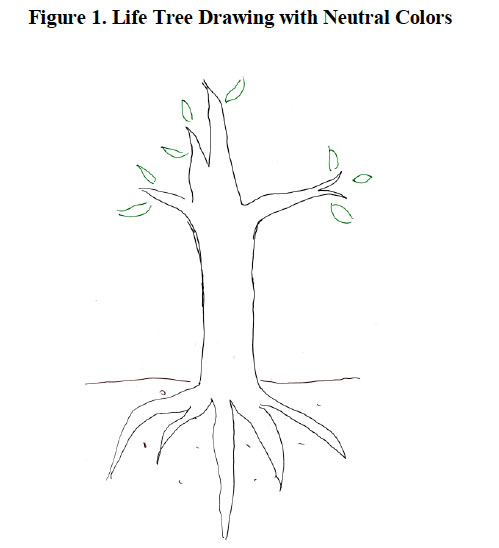

18 During the first interviews, I found my neutral position inadequate, since some participants needed a more conversational approach as well as probing questions. Taking a more active role helped me to get closer to the participants’ world (see Smith & Osborn, 2008; on dialogical perspective, see Mishler, 1986). In any case, some participants mostly talked on their own without prompting. The following citation (Figure 1) shows how meanings were sometimes constructed in a dialogue:

P: I don’t know why I drew such a big root for the tree ... I don’t necessarily want to think that it is a part of the tree ... rather you get the best pieces from there .... I don’t know. I feel that I have experienced so many things. Perhaps a lot of education is there and many interests. And perhaps ... being healthy. I don’t know how to separate them.

Me: OK. So do you mean that it is something that gives a foundation to the growth of the tree?

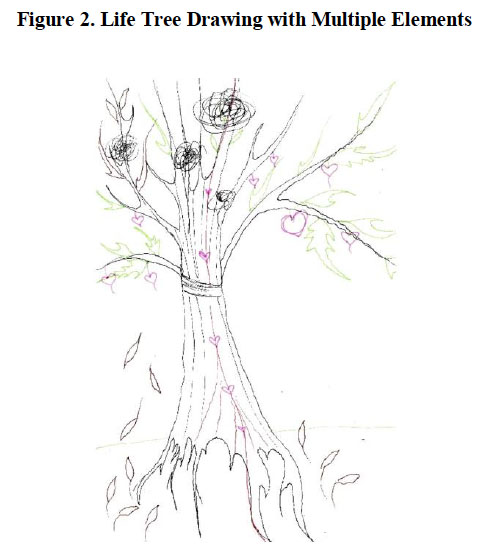

P: Yes.

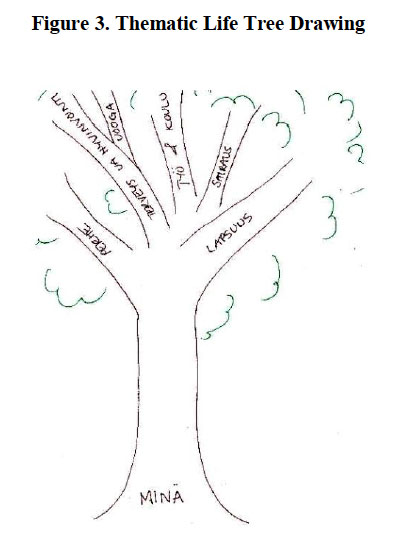

Me: OK.

P: Well, actually many things form the foundation, but also a lot of useless stuff too, not all the things end up here (in the foliage).

19 Since the life tree drawings were a new way for participants to think about life and cancer, it is possible that using a visual element may have changed their stories. It was rare that participants included their religion or worldview in their stories, although they were asked about them. Often, at the end of the interview, participants would say “I have never thought of it like this before,” or “I have never told the whole story to anyone,” or felt that “it was good to tell this again to someone.”

20 The young adults’ drawings are understood as narrative representations of life. Visuals are sign sets “that progress temporally, causally, or in some other socio-culturally recognisable way” (Esin & Squire, 2013, p. 4). Although Sartwell (2000) harshly critiques paintings for being “inanimate” and “never getting something accomplished” (p.105), my understanding is that the drawings and narrations were temporal constructions of the experience of cancer and life at that specific moment. At another time or place, or with another visual method, the story could have been different. When the drawings were analyzed together with the interview data, they often included a time perspective; both the impact of life events on the tree and social relations were narrated within the drawing. Visual methods are increasingly used in a wide range of research fields and are accepted as a part of qualitative research; it is also common that visuals and texts are used side by side to supplement each other (Pain, 2012).

21 I found the interviews to be an important tool enabling the drawings to be interpreted and given meaning, since it has been found that the visual objects can be highly personal (Gillies, Harden, Johnson, Reavey, Strange, & Willing, 2005). The analytical work could be defined as interpreting the interpretation. I respected the common understanding that arose during the interviews, but as Gadamer (2004) noted, shared understanding is discovered through an infinite dialogue in a “fusion of horizons” (cited by Regan, 2012, p. 289). In this hermeneutic process, the researcher always goes beyond the participant’s meaning in order to make sense of the experience. Both “understanding” and “interpreting” are needed to be able to “do greater justice to the totality of the person” (Smith & Osborn, 2008, p. 54). When presenting the results of the young adults’ stories, “a middle way” was selected. When differences in interpretations between the participant and myself occurred, both perspectives were brought up (see Wertz, Charmaz, McMullen, Josselson, Anderson, & McSpadden, 2011). For example, art therapy and art psychotherapy offer wide opportunities to interpret drawings (e.g. Rankanen, Hentinen, & Mantere, 2007; Leijala-Marttila & Huttula, 2011; Lieppinen, 2011), whereas the psychoanalytic approach can be used to explain the appearance of the trees drawn (e.g., Burns, 2009).

Critical Perspectives on Analysis

22 Rose’s (2007) critical approach to visual analysis was found to be very useful. I wanted to go beneath the surface while keeping three aspects—producing the image, the image itself, and audience—in mind. From the perspective of the drawing production process, it became apparent that the social aspect of the process was important. With a knowledge of the diagnosis, treatments, check-ups, future views, and so on, it was possible to analyze the cancer process as a whole. The instructions and drawing material dictated the visual work, at least to some extent. Still, the drawings share the genre of cancer patients’ life tree drawings. Although I was initially less interested in language structures, it was also important to focus on “how” the drawings were structured. From the perspective of an audience, numerous things can be seen to have affected the way the young adults drew and described their stories; they were making images for research and teaching purposes. The young adults shared high expectations of helping other young patients when sharing their stories (Saarelainen, in press).

23 My personal commitment to the situation impacted the research process as a whole. These drawings and stories were made and told for a young female, me, with no experience of going through cancer. Some of them seemed to have “googled” me and were aware of my former work as a Lutheran minister, but if they did not ask about my congregational background, I did not bring it up. The young adults often asked about my personal interest in the subject. It is a fact that I am approaching the research as an outsider with the point of view of not having personally been diagnosed with cancer. However, I am an insider from the witnessing point of view: I have known people who have been diagnosed with cancer at all different ages. I have seen their lives and shared their experiences, some very close, and some more at a distance. Some of these people have passed away. With these personal experiences, I feel I have at least some sense of the reality of cancer. As Bell (2006) notes, it is important to understand one’s own personal situation and reactions, and systematically integrate them with one’s research. I kept track of my own thoughts and emotions. I decided to write my own story and draw my own tree, to be able to better distinguish my individual thoughts from the participants’ processes.

24 No fixed rules govern how to evaluate validity, reliability, and ethics in narrative projects. When narrative research is scrutinized from the angle of validity and reliability, some basic definitions need to be noted. Narrative “truths” are always situated: the temporality of the context and interactive elements in certain situations become vivid. “Truths” portray individual experiences in a unique way, and it is more important to understand the meaning of the narratives, rather than verify the factual truth (see Polkinghorne, 1995; Riessman, 2008). The value of case studies can be seen in the detailed descriptions of certain contexts that are needed for the discipline to develop experimental and critical approaches which are essential to scientific progress, and, in addition, to further theorizing. Little things and daily details can give insight into how things occur in everyday life (Flyvberg, 2004). Narrative and paradigmatic cognitions are simply different ways of understanding the human mind (Bruner, 1986; Polkinghorne, 1995). I consider the data of these young adults to be an important source of knowledge when endeavoring to understand their cancer experiences and life stories.

Data Example: Trees and Tree Narrations

25 The following three types of trees were drawn. Firstly, neutral trees were discovered (Figure 1); in this type of drawing, the colors approximated the natural coloring of trees, with mostly green, brown, and black markers being used. Some trees were drawn only in black, and sometimes other colors such as red, pink, and orange were used if the tree had fruit or was blossoming.

26 Secondly, some used multiple elements in their trees (Figure 2). In such drawings, the participants used most of the markers, and the colors were often described as having emotional meanings. A variety of similar symbols were used in both the neutral and colorful trees. Figures 1 and 2 were selected to present half of the data. Figure 1 is one of the simplest trees drawn, whereas Figure 2 includes many of the most common elements. By selecting these two trees, it is possible to show how largely the trees varied, but also how they still had many similarities.

27 Thirdly, half of the participants decided to take a thematic approach to drawing their trees (Figure 3). On the tree trunk of Figure 3, “I” is written. The branches are marked with the following themes, starting from the left side of the tree: “family”; “health and well-being” together with a sprout featuring “yoga”; “work and school” on a branch next to “illness”; and a large “childhood” branch on the right. Most thematic trees included words that described different life stages or important incidents. One participant described his life with small pictures in the tree’s foliage. A few used no words in their trees and at first glimpse it seems that the trees were empty. However, analysis together with the interview data revealed a thematic approach being used in these drawings. The branches (sometimes hidden in foliage) carry different meanings, and cancer is described as part of the story.

28 These three drawings show the diversity of the trees drawn. This variation points out how the analysis was possible and how results were found even when the drawings differed from each other. The trees and their stories show how differently the participants experienced cancer; all three drawings were made by females whose treatment had ended less than a year earlier.

Conducting the Visual Narrative Analysis

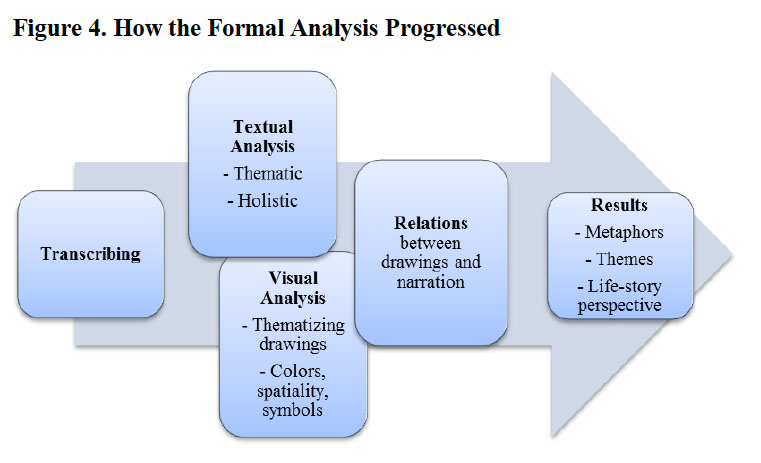

29 The different types of narrative texts (written, spoken, and visual) describe the participants’ personal stories, and at the same time, the different forms of data express the same story of the individual. When these are connected, our understanding of the participants’ experiences deepens (Keats, 2009). In this study, the formal analysis process consisted of five steps:

- Transcribing the textual material

- Analyzing the textual material

- Thematizing the drawingsObserving the use of colors and symbolsFocusing on spatial use of the paper and descriptive themes

- Noting what was narrated but not drawn, and vice versa

- Identifying metaphors

The interpretative work began when probing questions were asked about the participants’ stories and continued when writing down my thoughts after the interviews. To give a clear picture of the formal analysis, the steps are introduced one by one with a theoretical discussion and examples of analysis.

Steps 1 and 2: Transcribing and Analyzing the Text

30 After each interview, I took short notes about the atmosphere of the meeting and to record my personal thoughts. This was important because I wanted to consider how my presence may have contributed to the interview situation. I conducted and transcribed all the interview data myself. When writing the transcription, all words, pauses, and other expressions such as laughter and crying were noted. Some comments and intuitive thoughts were written on the margin of the page, to keep track of analytical thoughts. Following this raw transcribing, the second phase of transcription included dividing the text intuitively into “meaning units” (see Riessmann, 2008, pp. 34–37). When the participant changed a subject, theme, or style of narrating, I divided the text with an extra line space. Riessman (2008) points out that “meaning units” are usually a part of any structural analysis, and in addition, these units are helpful when hoping to achieve a more accessible transcription. Mishler (1986) mentions the importance of an accurate transcription when attempting to understand the “meaning of what is said” (p. 47).

31 The textual material was analyzed first to see what was actually said in the interviews, since it was found that the participants utilized their trees in different ways. The drawings were placed on a table, but I did not write comments on them at this stage. The narration was analyzed using a narrative method similar to what Riessman (2008) defines as a thematic approach, and comes near to what Lieblich (1998) defines as a holistic-content perspective. By combining these, it was possible to focus particularly on certain themes without losing the holistic life story perspective. Figure 2 depicts a story that has multiple twists with respect to the participant’s family: difficulties with her father, loving mother, and stepfather; her stepfather’s health problems; and her grandmother’s succumbing to cancer. Every now and then, family relations are connected to mental well-being and depression. In the end, these are part of her cancer story; she narrates support from her mother but wonders if her father’s alcohol abuse made her weak. This example shows how multiple layers of meaning can be found when maintaining a holistic approach instead of only dividing data according to themes such as family, cancer, and depression.

32 Analyzing the text also served to identify all tree-related narration in the interviews. The results of this holistic-thematic approach were kept in one folder, and of the “pure” tree-related narrations in another. With these partly overlapping files it was possible to proceed to the next steps. Step 3 included processes which progressed simultaneously, but for a clearer view of the process they are introduced one after the other.

Step 3: Thematizing the Drawings and Observing the Use of Colors and Symbols

33 The analysis of the drawings began by looking at each picture one by one and at the same time reading the tree-related drawing narration. The use of color was well worth noting. For example, a common feature of Figures 1 and 2 is the way green and pink are used. The participants expressed hope and recovery with these colors. In Figure 2, the green leaves and blooms were described as representing the participant’s feelings about life and strong hopes for the future. In Figure 1, the participant’s hesitations and hopes were interwoven (in her tree description) as follows: “it has not decided yet which direction to grow in.” She was uncertain what to think about the cancer at this stage of life, and said that she wanted to forget the disease but did not know how. She wanted to remain positive and said that the green leaves meant “promising new growth.” Overall, bright colors were used to describe positive views of life and the future. However, black was the color most used, depicting cancer and negative experience. In the thematic trees, only black or brown markers were used to express the themes. Yet even some of these participants used green to represent the foliage (Figure 3).

34 The participants’ descriptions of colors were marked on the drawings when they were mentioned. From expressions like “I’m using a nice color to represent happiness,” it was possible to detect how the participants sometimes associated colors and with emotions. For example, I wrote “pink—happiness” in the margin of Figure 2 and “green— growth” in the margin of Figures 1 and 2. Lev-Wiesel and Liraz (2007) pointed out that in art therapy the use of colors can reveal important information from a diagnostic angle and that colors have therapeutic value. It was difficult to determine the reasons for the selection of certain colors rather than the black marker. For example, some participants only used a black marker even though the narration had multiple “shades” and was spoken in a positive tone of voice. If I were to re-gather the data, I would inquire about the selection of colors in more detail, in order to analyze the use of the markers more precisely. The basic problem was that the meaning of the colors was often narrated when multiple colors were used, whereas when using only one color—usually black—there was little to say. This could only result from the fact that the black marker was offered first. I decided to focus on individuals’ explanations of certain colors and only give a general overview of the participants’ use of color. In the drawings of children, color use has not correlated with positive and negative events; rather, the color selection was based on preferred colors (Crawford, Gross, Patterson, & Hayne, 2012).

35 The trees exhibited several positive and negative symbols. In Figure 2, a rich use of symbols is evident. The hearts were explained as representing good things in life, and the red thread represented the persisting thread of life. Tree nests were drawn to represent different negative events in life; some were described in more detail, others only briefly. In Figure 1, the use of symbols is more restrained. For example, cancer is not described with a specific symbol but its impact becomes vivid in the participant’s descriptions; for example, according to her, “the tree is alive. It is not a dead tree.” It was common that green leaves symbolized well-being, suggesting that the green leaves in the thematic tree (Figure 3) had a similar meaning. The participant herself mentioned nothing about leaves, but her story included much hope for the future and she described her tree as “solid.”

36 Picard and Lebaz (2010) argued that it is not clear whether the use of colors and size of the tree can be seen as symbolic representations of feelings in the case of freehand drawings. Even though trees are often used as symbols, there is only a limited amount of research that would be helpful to clinicians when interpreting such drawings. Crawford et al. (2012) concluded that rather than making assumptions about feelings based on color use, drawings should be used as a tool to encourage communication. Nonetheless, some correlation between the color use and feelings was found in the young adults’ drawings and narrations. The visual element functioned as an important “icebreaker” that seemed to reduce the tension and excitement arising from the interview situation.

Focusing on Spatial Use of the Paper and Descriptive Themes

37 It was interesting to observe such details as how much of the paper and which areas of it were used, as well as the visibility of the tree as a whole. The paper was generally used vertically except in one drawing. Some participants left the future story open and did not draw the tree as a whole. In such cases, the top of the tree was left out. These participants stated that they did not want to think or talk about the future in any detail. Some said that there were two different possibilities: either the cancer would recur or they would have a healthy life.

38 It was possible to ascribe evident descriptive themes to the drawings and look for correlations between them and the narrations. For example, Figure 1 was seen as “forming one’s self/life” under the tree’s roots, since the participant said, “there are many things in there, it is like the foundation of the tree, there is a lot of useless stuff too, and not all the things end up here (in the foliage).” Figure 2 included the descriptive theme of “cancer—choking” that was written next to a black band on the tree trunk. I wrote “father—problems, lack of support” on the left side of the roots and “mother—love, support” on the right side, as it was described in the interview. In the thematic trees, the participants often wrote the key themes themselves. In these cases, some descriptive words were added to make the connections more evident; for example, in Figure 1, “I—strong” and “Illness—only one small branch,” were written.

39 With the intratextual approach it was possible to see what the individual themes and symbols meant at the personal level. For its part, the intertextual approach offered the possibility of seeing more generally what kind of themes and symbols were used to describe positive life experiences. The growth of the tree, its green leaves, and fruit were said to symbolize positive experiences and mental healing after the crisis. Overall, it can still be said that the thematic trees had fewer symbols than the other types of trees. Cancer and other negative life events were often described as dead branches, scars in the tree trunk, and tree nests.

40 I consider that the value of the symbols used in drawings can be found when understanding them in terms of how Coufal and Coufal (2007) frame it: “drawing is a personal symbol system that allows the composer to use an invented symbol system that is not constrained by the complexities of the grammatical structure of language” (p. 110). At the same time, symbols are learned from the surrounding culture but can be used when creating individual expressions.

Step 4: What Was Said and What Was Drawn

41 Thematizing the drawings pointed out that the tree narrations and the drawings were dissimilar. This led to the following question: What was the relation between the participants’ life stories as a whole and their drawings? This comparison, in turn, showed that some of the pictures’ elements were not narrated, and that some themes were left out of the pictures.

42 Even though I asked careful questions about the visual elements, sometimes the participants were not able to express themselves or did not give direct answers. When I could not find possible explanations through the story or analysis, I looked for theoretical interpretations. For example, one participant required an amputation because of the cancer. A black hole is drawn on his tree trunk and a dead branch appears from the hole. The dead branch was described as symbolizing the cancer, but he could not explain the hole. Burns (2009) suggests that “traumatic indices on the tree trunk seem to reflect the age a severe trauma was experienced” (p. 190) and that “deep shading on a trunk suggests pervasive anxieties” (p. 191). Without losing the participant’s personal view, it is possible to bring these aspects together by saying that the participant himself did not find a meaning for the hole, but from a psychoanalytical perspective, it can be suggested that the hole symbolizes his age when diagnosed with cancer. Still, the elements were there, and they were drawn to represent the participants’ lives. Most of the trees’ elements were narrated and had a clear meaning for the participant. Even though it was difficult to verbalize the meaning of certain symbolic representations, the drawings can be seen as an important way of expressing difficult emotions (see also Lev-Wiesel & Liraz, 2007; Schick Makarof, Sheilds, & Molzahn, 2013).

43 Some themes were not drawn at all; for example, sometimes the trees make no reference to cancer (Figure 1), but the related narration otherwise explains the cancer’s impact. Religion was not commonly visualized even though most of the participants had existential questions and engaged in religious seeking after their diagnosis. Most participants exhibited what could be defined as religious coping (Saarelainen, in press). For some, religion was not a priority in terms of their whole life perspective, but it often had an impact on their cancer experience and therefore was narrated as a separate and small story. On the other hand, many participants for whom religion was more central did not picture it as a part of the tree (Figure 3). Only one of the participants drew a symbol that was linked to her personal conviction (Figure 2). Death, and fear of death, were often described in many words but rarely pictured as part of the tree. In addition, smaller details were rarely included in the pictures.

44 These cases show that it would be difficult and sometimes even impossible to analyze the drawings on their own. The importance of the dialogue was also seen in the verbal corrections that were made about the drawings. For instance, “the tree seems too solid” was mentioned so that the picture might be better understood. With more than one symbol system, as in the case of this research, it is likely that they are incongruous. Sometimes words can convey concepts that are difficult to express through visual elements, whereas visual representations may evoke something unexpected (e.g. Coufal & Coufal, 2002; Gillies, Harden, Johnson, Reavey, Strange, &Willing, 2004, 2005).

Step 5: Metaphorical Representations as Results of Visual Narrative Analysis

45 Once the analysis process was well underway, it became clear that the participants had different ways of understanding the tree as a metaphor. Even though the task was to use the trees as metaphors of the lives they had lived, other metaphors were also found. The discovered metaphors are one of the main results of the visual narrative analysis.

46 The metaphor of support was often described as the roots of the tree. The roots—in other words, “significant others”—were keeping the tree stable. Sometimes significant others were pictured as an independent branch of a tree and their support was described as important (Figure 3). The metaphor had diverse aspects. For instance, sometimes roots were not drawn but instead verbally described: “the tree has strong roots.” In these cases, it was understood that the drawings were unfinished and that the participants wanted to make sure that it was clear that the roots were there, even though one could not see them. A counter-narrative of lack of support appeared when some participants said they deliberately did not draw roots, since they felt that their families could not support them enough.

47 The metaphor of self was evident in trees that included descriptions of cancer having impacted their growth or blooming. For example, in Figure 2, “the fruits (referring to hearts) symbolize how versatile my life has been ... even though I’m so young.” This participant gave multiple examples of things in her life which had impacted her identity and sense of self. She described how her mother had always trusted her, which is why she had had so many experiences even though she was “so young.” In other trees, scars on the tree trunk were described as wounds on one’s self and one’s identity. These symbols narrated how cancer continued to have an impact on life years after the end of treatment. In the thematic trees, cancer was described, as in Figure 3, as only one branch—only one element of one’s life.

48 The body metaphor was found in descriptions of cancer having a similar impact on the tree as the actual cancer had on the individual. For instance, the black band choking the tree in Drawing 2 was described by one participant in the following way: “I just had to draw it there, since the tumor was here (puts her hand on her chest and throat), a thing that was pressing on my chest and very uncomfortable. I don’t know if it is there anymore.” In her life story, the fear of choking was described as being present even before the tumor was found. Sometimes holes and dead branches were described to represent both the cancer and the individual’s body.

49 The metaphor of time was evident in the most of the drawings. It was often expressed from the bottom up: the roots as childhood, the trunk as adolescence, and the foliage featuring young adulthood with cancer experience representing the future. The thematic trees’ time perspective was not particularly vivid; rather, the importance of the themes was emphasized, often through the sizes of the branches (Figure 3) or thematic boxes in the foliage. Sometimes, thematic boxes or small drawings were organized in such order as to follow the participant’s actual life events. Among all of the trees, only one thematic drawing included a cross, symbolizing death at an unknown time. When the aspect of hope appeared, it was closely linked to time. The participants’ views of the future included many hopes and plans, but for some it was too frightening to think about this.

50 In these metaphorical representations, the drawings revealed their narrative nature by proposing new layers of stories about experiencing life with cancer. It is difficult to estimate what would have been narrated without the drawings. It seems that metaphorical descriptions would have not been found otherwise. For example, the importance of significant others appeared in the narration, but their importance with respect to providing solid ground for daily life could have been remain hidden. Cancer’s impact on self and body were often described more deeply within the tree narrations than otherwise. The metaphorical representations were intertwined, and each drawing usually included more than one metaphor.

Conclusions

51 The life tree served the purpose of the autobiographical interviews, and it was interesting to see the extent of the cancer in the trees. An important finding was that the trees were growing and some were blooming even though it was reported earlier that the young adults were coping poorly with the cancer. The tree could only include a certain amount of data, and it rarely included coping practices and worldviews. If there had been a second drawing task concerning only the cancer experience itself, more clarity could have emerged in this area. In the future it would be interesting to take a more co-constructive approach, giving participants a more active role and an opportunity to return feedback during the analysis process. Perhaps the participants themselves could benefit from group meetings, since peer support was reported to have a positive impact on coping.

52 The “plot” of young adults’ stories was different than expected, but it was found that the participants had a life before, during, and after cancer, but that sometimes there were gaps in the story that could not be filled in. This is the reality for a number of the cancer patients. The original inspiration discovered from the form of a plot transformed to an understanding of the importance of different narrations. Coherence and incoherence alternated during the interviews, but every detail was needed in order to more fully understand the cancer experience. Even “small mistakes” in the drawings enriched the story and the participants’ interpretations of the situation.

53 I wanted to make sure that my visual narrative analysis was a uniform combination of both visual and narrative analyses rather than only an analysis of drawing narrations. Figure 4 shows how the different steps of the formal analysis formed a unity:

54 When the multifaceted findings from the analysis process were brought together, metaphorical descriptions of the cancer process and life emerged from the drawings. The combination of the analyses highlighted certain aspects of the stories and allowed for new insights. For example, the metaphor of time showed how some participants wanted to emphasize that cancer was only one part of life. For others, the time aspect showed that the impact was more long-term.

55 The visual methodology itself provides many possibilities for analysis and interpretation (Bell, 2004; Rose, 2007; Prosser & Loxley, 2008). With the narrative approach, selecting from among multiple alternatives is possible (Mishler, 1986; 1995; 1999; Polkinghorne, 1995; Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, 1998; Riessman, 2008; Gee, 2008). Most important is to find a way to combine suitable forms of analysis in order to reach a balance between the visual material and other narrative data. According to Hinthorne (2012), the visual elements both reveal data and lead to findings that would have remained hidden. In my research, the life tree drawings allowed for a fascinating analysis, interesting findings, and most importantly, a deep understanding of young adults’ life reality with cancer.