Articles

The Perceived Impact of Parental Depression on the Narrative Construction of Personal Identity:

Reflections from Emerging Adults

This paper presents a narrative analysis of emerging adults’ perceptions of the impact of parental depression on themselves as they reflected back on their lives in their natal home. Archived interview narratives were analyzed from sixteen respondents from a preventive intervention study of depression in families. The perceptions of parental depression and the perceived impact of parental depression were found to fall into five perspectives: resistance (no impact), negativity (being disadvantaged), ambivalent perspectives (disadvantaged but also sensitized), acceptance (reconciling with loss), and, compassion (sensitivity and caregiving). The findings from the narratives indicated that the perceived impacts of parental depression spanned a spectrum of responses, not all of which were negative. Emerging adults with their own history of depression reported a more resistant or negative perceived impact of parental depression, and more boys than girls narrated perceived negative impacts of parental depression on the self. These perspectives on parental depression derived from the narratives offer clinicians and family therapists a means of understanding the impact of depression on emerging adults’ sense of self. Implications of language usage, such as tense and coherence, are also discussed.

1 Emerging adulthood is a developmental phase sandwiched between adolescence and young adulthood (Arnett, 2000), characterized by multiple transitions in the biological, psychological, and socio-cultural realms (Arnett, 2000, 2006). The social, contextual, and developmental changes that accompany the end of high school contribute to a higher density overall of social role changes during this period than at any other time in an individual’s life trajectory (Shanahan, 2000). The specific challenge for emerging adults is the reconciliation of the contradictory impulses of pursuing autonomy (associated with adulthood) versus retaining intimacy with their parents (associated with childhood). Gaining mastery over the associated emotions is at the core of this developmental stage. Relationships with family members typically improve during emerging adulthood compared to adolescence (Aquilino, 2006; Arnett, 2006; Fuligni & Pedersen, 2002).

2 Accomplishing the developmental tasks of autonomy and relatedness could be a challenge during the transition to adulthood, because adolescents from families with depression are consistently documented as being at high risk for abnormal socio-emotional development, including their own risk of developing depression, difficulties in relationships, and in achieving normal developmental milestones (Beardslee, Schultz, & Selman, 1987; Dansky, 1986; Klimes- Gougan et al., 1999; Langrock et al., 2002). Impaired parenting abilities due to an affective illness could markedly affect this transition to adulthood (Dansky, 1986), especially since adolescent children of parents with depression are at high risk of developing the disease themselves (Beardslee, Keller, & Klerman, 1986; Langrock, Compas, Keller, Merchant, & Copeland, 2002). Environmental factors, including negative life events and conditions (Kendler, Thornton, & Gardner, 2001); early health problems and family patterns of depressive symptomatology (Reinherz, Giaconia, Carmola Hauf, Wasserman, & Silverman, 1999); and gender (Petersen, Sarigiani, & Kennedy, 1991) can influence the occurrence and course of depression in emerging adults.

3 Although the above research studies illustrate outcomes for children from families with mental illness and other life stressors, little is known specifically about the perceived impact of parental depression. Some narratives about the experience of depression are found in autobiographical (Casey, 2001; Jamison, 1996; Smith, 1999) and biographical (Shenk, 2005) literature detailing personal accounts of struggles with the illness. These narratives include references to struggles with reconciling the identity of loved ones with their identity when they are ill, fluctuating self-worth, and fears for functioning successfully in society (Casey, 2001). Stigma and inadequate awareness of the illness were reported to impact the lives of those suffering from depression, as well as those who surround them (Shenk, 2005), especially in contexts where depression is not accepted as an illness (Danquah, 2002). These narratives, however, are anecdotes of experiences in individual cases written by older adult writers after much reflection and life experience.

4 Understanding the subjective experiences of youth as they transition out of a home with parental depression can help illuminate their unique constructions of individual identity, including identifying potential vulnerabilities and strengths. Applying methodology used for understanding adolescent experience is inappropriate, as a different approach is required for emerging adults (Arnett, 2006). When underlying developmental processes are poorly understood, qualitative analyses can help to uncover and explain potential sources of variation (Briggs, 1989; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Narratives, in particular, with the focus on point of view and temporality in piecing together multiple, disparate, and potentially alienated selves (Ochs & Capps, 1996), can be particularly useful in understanding the construction of the self. The analysis of narratives provides this voice to emerging adult children of depressed parents and illuminates their lived experience. Narrative is not just a means to recapture an experience, but also a way to understand the meaning of the experience to the individual (Skinner, Bailey, Correa, & Rodriguez, 1999). Telling one’s story enables a person to organize and integrate new experiences into the various roles that define his or her identity (Josselson, 1987; McAdams, 1993; Ochs & Capps, 1996).

5 Beardslee and Podorefsky (1988) presented evidence that children who expressed a deep self-understanding and a self-perceived identity that was distinct from the parent made successful transitions out of the home. In a previous paper, Kaimal & Beardslee (2010) presented a conceptual framework underlying children’s perception of parental depression. We described each perspective as representing a distinct narrative about the perceptions of parental depression: resistance was a denial or minimization of parental depression; negativity involved a focus on the unpleasant aspects of parental depression; ambivalence was the co- occurrence of conflicting perceptions; acceptance was a resolution with respect to parental depression; and compassion was a perspective that perceived the depressed parent as an individual suffering from an illness and therefore deserving of kindness. That paper was, however, focused on the perception of parental depression, and not on the perceived impact of parental depression on the self. In this paper, we examine how the five- perspective framework maps on to the children’s perception of themselves and what we can learn about emerging adults’ perception of the impact of parental depression .

Methods

6 The data for this study came from two longitudinal, preventive intervention studies of families with depression. The preventive intervention approach educated parents on how to minimize psychosocial risk in their children through understanding the impact and experience of parental depression (Beardslee et al., 1997). In the pilot phase of the study, 32 families were enrolled and later, 21 more families agreed to have their children participate directly at future assessment points. Families were recruited into the study through a large, pre-paid, health maintenance organization and referrals from mental health practitioners. Dual and single-parent families were invited to participate if at least one parent had experienced an episode of depression in the past 18 months and had at least one child between the ages of 8 and 14 who had not experienced depression (Beardslee et al., 1997). The children were typically between 8 and 14 years of age when the study began. They were in their late teens and 20s when the study ended in 2003. The combined sample is constituted of mostly middle-class and Caucasian families but includes a range of socio-economic and educational backgrounds. Sixty- four percent of the families fell within the top two socio-economic levels on the Hollingshead and Redlich (1958) classification. Ninety-three percent of the parents were white and 43 percent had a graduate or professional degree. Ten percent of the parents had a high school education or less. In 77 percent of the families, the mother was the identified patient (Beardslee et al., 2003).

7 The families in the clinician-facilitated intervention group received six to 11 sessions. This included separate meetings with parents and children, family meetings, and telephone contact at 6- to 9-month intervals. The core elements of the clinician-facilitated intervention were: 1) assessing all family members; 2) presenting psychoeducational material about mood disorders; 3) assessing risk and resilience in children, linking the psychoeducational material to the family’s life experience; 4) decreasing feelings of guilt/blame in children; and 5) helping children develop relationships within and outside of the family. An explicit goal of the clinician-facilitated intervention was to foster the families’ self-understanding of the illness experience. The lecture group consisted of two separate meetings presented in a group format without children present. As in the clinician-facilitated intervention, mood disorders were presented in the context of family experience and parents were encouraged to talk to their children about parental illness (Beardslee et al., 2003).

8 After the initial interventions, each family enrolled in the study completed a semi-structured interview as well as many standardized survey measures once a year. All aspects of data collection, including semi-structured interviews and standardized measures (demographics and scales for affective disorders, depression, relationship, and self-esteem), collected from the families over a period of over ten years, were the same for both groups. The interviews from the preventive intervention studies constitute the data for this study. Interviews were conducted with all the participants in this study as part of a battery of annual assessments. For this analysis, we used the semi-structured, young adult interview data conducted with children after they turned 18 (see Appendix). The research question on the perceived impact of parental depression was approached as a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis. In recognition of the cognitive and developmental maturities of this age, respondents were asked more reflective autobiographical questions, compared to the previous interviews when they were younger. The emerging adult respondents were expressly asked to reflect back on their adolescence and articulate their perceptions of the impact of parental depression. Examples of questions from the interview included in this analysis were:

- What was the impact of depression on your relationships with others your age?

- Looking back, what impact has depression in your family had on your own life?

- How has the transition out of the home gone for you? Did you face any difficulties?

- Were those difficulties related to the presence of depression in your family?

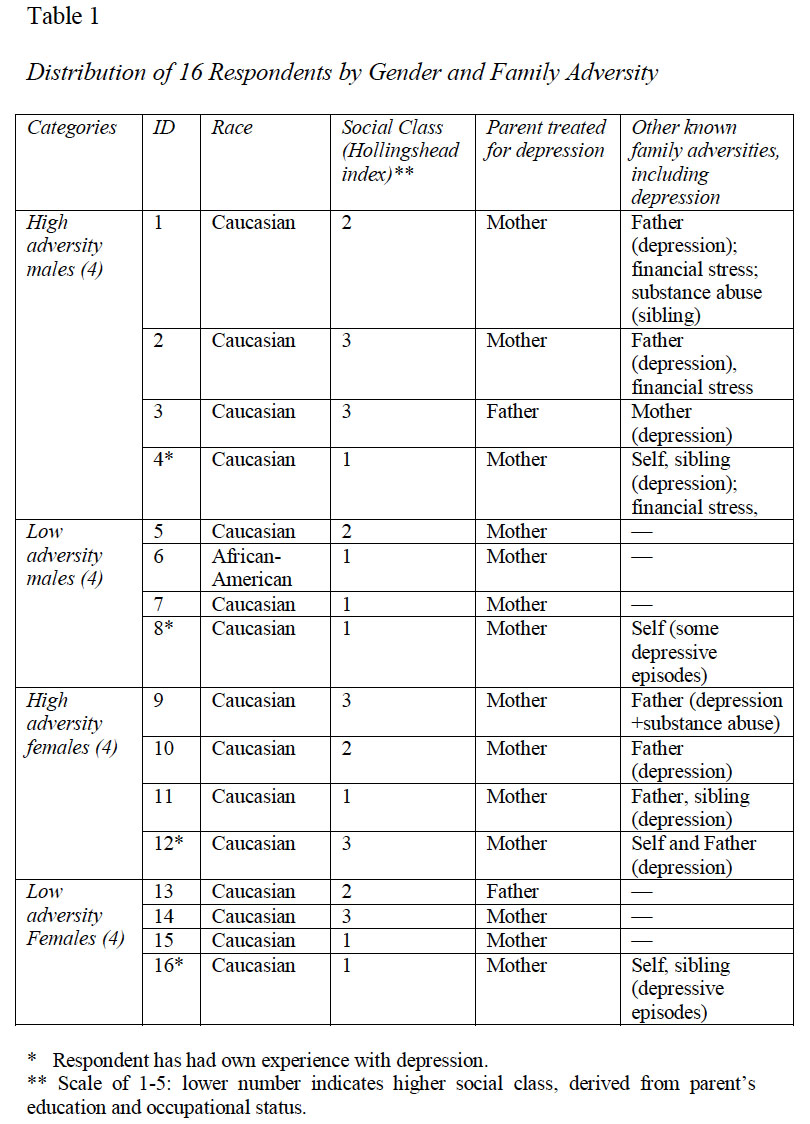

9 Based on the availability of audible, tape-recorded interviews for young adults aged 19 to 20 years of age (the age when they had typically left home), 16 respondents were included in this analysis. This included eight males and eight females to represent extremes of high and low family adversity (see Table 1). High adversity refers to families that had experienced major parental depression in one or both parents and had faced additional struggles, including financial, legal, and/or health challenges, or other traumatic events. Low adversity refers to families that had experienced parental depression in one parent and no other reported parental or family adversities.

** Scale of 1-5: lower number indicates higher social class, derived from parent’s education and occupational status.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1

10 These interviews were available as audiotaped recordings that were archived by the program staff who conducted the interviews. All the interviews were transcribed by Beardslee. The units of analysis in the transcribed interview narratives were the responses to the interview questions, which tended to range from one sentence to several sentences. Given the absence of research on emerging adult narratives and parental depression, the initial coding for this study was developed from prior research on autobiographical life story narratives (McAdams, 2001). The interview narratives (specifically, the sections that focused on the perceived impact of parental depression) were coded for aspects of autonomy and relatedness, the developmental tasks of emerging adulthood. It was based on this coding that we (Kaimal & Beardslee, 2010) previously identified the five perspectives on parental depression described above: resistance, negativity, ambivalence, acceptance, and compassion. The specific segments of the interviews that focused on perceived impact on the self were further coded using the framework of the five perspectives to see if they mapped on. A second coder coded a sample of interviews to ensure validity of the framework and findings. Memos were created to track ideas and reflections of the coders during the process. A matrix was then created to facilitate visual examination of coded responses and framework from the participants. Data saturation was achieved with this sample of 16 respondents because we did not notice any additional themes.

Findings

11 The authors considered the possibility that the perceived impact of parental depression on the self might mirror our framework of five perspectives and reflect some or all aspects of the different perspectives held by the respondent about the parent. The question of the impact of parental depression provides a window into the individual voices and perspectives of the lived experiences of children of depressed parents. The respondents embody the perspectives, but their responses to the question also reveal a deeper narrative self: a unique developmental identity defined in some measure by parental depression. The findings indicate that the perceived impact of parental depression mapped on and expanded understanding of the perspectives towards parental depression for many of the respondents. Many articulated a negative impact on themselves, but included references to a positive outcome through the negative experience. Some made complex abstract associations between parental depression and their own behavioral patterns and responses. Others limited their assessment of the impact of parental depression to simple responses, such as awareness of the illness of depression.

12 Each theme that arose in this analysis is related to one of the five perspectives and is discussed with representative quotations from the interview narratives. The themes included resistance to any perceived impact (no impact, minimizing), negative impact (disempowerment/ disadvantage), ambivalence (concurrent unresolved positive and negative perceptions of impact), acceptance (reconciling with loss) and compassion (sensitivity/caregiving).

Resistance: No Impact, Minimization

13 Resistance was defined as the refusal to identify or attribute to parental depression any perceived impact on the self. This manifested in refusing to attribute any impact to parental depression, making intellectualized references, and/or minimizing any impact of parental depression on the respondent’s past or current life context:

This respondent had a persistently resistant perspective towards parental depression in all parts of the interview. He did not present a clear or coherent answer to the perceived impact of parental depression that suggested any impact beyond an allusion to some concern that his moods and behaviors might be similar to those of his depressed parent. The respondent was exceptionally articulate in all other parts of the interview, but his narrative lost coherence in discussions around the perceived impact of parental depression. This is the reason why his response was coded as Resistance. Within the context of the interview and the narrative quoted above, there was a fear of losing control and efforts to monitor his own moods. These statements, although indicative of some efforts at self- awareness, were nevertheless not narrated with clarity, and his perception remains unclear to the reader. There appears to be a fear of experiencing the parent’s illness because of the close relationship: a shared familial relationship seemed to imply a shared illness. The respondent did not differentiate between the parental illness and his individuality with respect to his relationship with his parents. This was interpreted as a focus on the self along with a reluctance to articulate any perceived impact of parental depression.

14 A similar narrative describing a lack of impact of parental depression was seen with another respondent:

-Daughter; own history of depression in addition to mother’s depression

When asked about the impact of parental depression on herself, the respondent did not identify any impact. She distanced and depersonalized the relationship by switching from referring to her mother as “she” to a depersonalized reference to “people with depression.” The respondent also equated her mother’s illness behaviors with normative mood shifts, by saying that her mother “kept it to herself.” Although these narratives cannot verify whether the respondent truly believed that there was no impact, the resistance to any perceived impact of parental depression is important in light of her own personal experience with depression and her belief (reported in another part of the interview) that her mother’s depression was caused by personal inadequacies in the respondent and her siblings. Given her own experience with depression, this respondent assumed responsibility for all her difficulties and for the origins of her mother’s symptoms, and completely “normalized” her mother’s moods and symptoms in the narrative.

15 This refusal to attribute to parental depression any impact on the self was also seen in a male respondent who had a personal history of depression. He was particularly hard to code because he was not very articulate in his interview:

-Son; own history of depression in addition to mother’s depression

In his narrative of the impact of parental depression, this respondent did not really answer the question. He did not refer to any impact of his mother’s depression. He referred instead to the perceived impact of his own depression. Despite being from a high-adversity family, he did not consider any long-term impact of parental depression on himself or any aspect of his life. This respondent’s attribution of the impact to himself is important to note and was similar to other respondents who had a personal experience with depression.

Negativity: Feeling Disempowered/Disadvantaged

16 The negativity in references to the perceived impact of parental depression was expressed as a negative aspect of their life experiences. This included feeling disempowered and diffident in social interactions, feeling guilty, and feeling forced to grow up faster. The following is an example of this perceived negative impact of parental depression on the respondent’s confidence in social contexts. Referring to the impact of parental depression on himself, he says:

-Son; mother diagnosed with major depression

This is an example of a reported negative impact of parental depression on the self in a respondent who overall had an ambivalent perspective towards parental depression. He identified his frustration towards his mother as an inadequate parent by accusing her of not modeling appropriate behaviors in occupational and social realms. In addition, he attributed to maternal depression the negative consequence of poor homemaking. His narrative did leave room for future changes and insights when he referred to some unknown “deeper psychological impact” that was unidentified at present. This equivocation mirrors his overall ambivalence towards maternal depression, but the identified impact is entirely unflattering and embodies a purely negative impact of parental depression. Few respondents presented a purely negative narrative without adding some additional dimensions that reflected their self-perceived agency and development. This respondent also had an intensely difficult transition to college and continued to engage in some risky and self-defeating behaviors at 19 years. Few respondents in this study had such completely negative perceptions and his negativity set him apart from most of the other respondents from low-adversity families.

Ambivalence: Concurrent Unresolved Positive and Negative Perceptions of Impact

17 Many respondents described some positive aspects in addition to negative aspects in the perceived impact of parental depression. These positive and negative perceptions were sometimes held in unresolved conflict. Descriptions from two respondents illustrate this perspective. For the respondent quoted below, disempowerment was described in the loss of her individuality and her voice. However, the loss of voice was presented in the context of the desire to maintain harmony in the relationship. These conflicting perceptions of the impact of parental depression on herself remained unresolved for her at the time of the interview:

In the perceived impact of parental depression, the respondent offered an explanation for her dynamic in interpersonal relationships. She attributed her conflicting urges to her interactions with her depressed mother. Notably, the respondent described the impact in the present tense, as an ongoing struggle. She did not present it as a purely negative narrative about the impact of parental depression; rather, she presented a contradictory set of impulses. She “knows” that her behaviors were suppressing her voice and individuality, and yet this suppression of voice serveda purpose that had an emotional value to her. Choosing one or the other option involved a perceived loss: either of the relationship or of her voice. This particular excerpt might imply a purely negative experience, but in other parts of the interview the respondent reported having a very supportive and close relationship with her mother and it was the memories of when her mother) was angry that had impacted part of the respondent’s own reactions to people who got angry with her. The recurring use of "is" in her narrative indicates that the perception of the positive and negative aspects of the impact of parental depression is not yet resolved.

18 Another respondent described this suppression of anger but was less clear about how parental depression could have contributed to his behaviors. Ambivalence in this case was concordant with his overall perspective towards his mother and the perceived impact of parental depression:

In the narrative above, the respondent seemed unable to separate the impact of parental depression from his own personality characteristics and attributed concurrent positive and negative aspects to parental depression. He was not forthcoming about how parental depression affected him in certain relationships and yet identified the unresolved co- existence of being more empathic and yet somehow someone without a distinct and assertive voice. In this case, empathy and the ability to express anger were not perceived to be able to co-exist and the existence of one precluded the presence of the other.

19 Competing emotions were presented in numerous narratives. However, not all respondents held unresolved responses. Many who demonstrated the perspectives of acceptance and compassion narrated a sense of some resolution of the conflicting emotions.

Acceptance: Reconciling with Loss

20 Acceptance of the perceived impact involved acknowledgment of some form of disempowerment and loss due to parental depression, with a co-occurring narrative about self-created resolutions of that loss. There is an inherent resolution in the narrative despite references to negative effects of parental depression on the self. The reference is often made in the past tense, unlike negativity, resistance, and even ambivalence, which are often referred to in the present tense:

In the above narrative the respondent narrated a primarily negative impact of parental depression. Yet he narrated the negativity as an experience of the past, not a problem of the present. He “couldn’t” see what upset others; his relationship with his mother “made it harder.” The negativity was described as an experience of the past, his early years. The respondent’s current individuated voice then emerged in the latter part of the quotation. Here, he described the incongruence between his experiences with friends and his relationship with his mother. All the relational confusion was relegated to the past and was not described in the present tense. In this case, he was aware of some impact on his own life but was able to differentiate the experience with his mother from that with his friends, despite the disempowerment and loss of confidence in approaching people. This narrative is different from that of respondents for whom the negativity was a current unresolved issue, as seen in earlier examples of ambivalence. Typically, this assertion of impact as a feature of the past implied acceptance: that the perceived impact of parental depression was something that did not have an ongoing and/or immediate impact on the child’s life course. Overall, it was found that acceptance and compassion were perspectives that implied a successful integration of parental depression into the life stories of the respondents in a way that was not resistant, conflicted, or negative.

21 Another aspect of the theme of reconciling with loss was the recurring narrative of a “forced early maturation.” These respondents included references to losing their childhood because of having to care for siblings; being forced to care for themselves unlike their peers; and having to take on household responsibilities that were ordinarily considered the domain of parents. Narratives of early maturation were reported by the oldest sons in the sample, especially those from high- adversity families. Although many boys undertook responsibilities for their homes and siblings, sometimes unwillingly, their narratives also referred to a sense of competence and self-mastery as a result of the hastened maturation:

In the above narrative, the respondent clearly refers to a forced assumption of responsibilities that he was neither ready nor willing to take on. He then justified many of his subsequent actions as a consequence of feeling much older than his years. He did not bemoan the maturation. He considered himself as mature, as someone older than he in chronological years. The narrative is not entirely negative, despite the acknowledgment of loss. He revealed remnants of his earlier ambivalence and resentment when he corrected himself—“I did not really enjoy my childhood … I mean I did but I wish it could have lasted longer”—and then clarified further that it was not entirely lost, only that he wished it could have lasted longer. There is an expressed resolution of loss without denial, and a justification for the resulting self-confidence and sense of responsibility. Two other male respondents also attributed “growing up faster,” compared with peers, to their experience of parental depression. This differentiation of the self from peers was described as the product of severe depression in one or both parents.

Compassion: Sensitivity to Others, Caretaking, Kindness, Awareness

22 Compassion as the perceived impact of parental depression manifested in references to being sensitive to others, being aware of others’ needs, and being caring, kind, and loving. These references often were hard to distinguish from resistance. Compassion as the perceived impact of parental depression, to the exclusion of all perspectives, was repeatedly seen in the interviews with the female respondents. One female respondent indicated no perceived negative impact of parental depression on herself, despite earlier negative references to the experience of parental depression:

These responses were entirely focused on the needs of others and were striking in the absence of any perceived negative impact on the self. The sensitization to others was also seen in two male respondents, but their overall narratives were resistant at all time points. Their sensitivity to others was an extension of their perspective towards their parents. However, for the girls, the sensitivity was not an extension of the resistance. Few girls held resistant perspectives towards parental depression and the perceived impact of parental depression was predominantly described in compassionate terms.

Discussion and Implications

23 This paper presents an analysis of emerging adult children’s perceived impact of parental depression on themselves. Reflecting upon and narrating the perceived impact of parental depression on the self required the respondents to draw connections between their experience of parental depression and some aspect of their own lives and patterns of interaction. Unlike being asked interview questions about the experiences of interacting with a depressed parent, this question involved taking a longer-term view of the effects of parental depression on some aspect of the respondents’ lives and life stories. The response required integrating several family story lines and partial selves—including those alienated selves created by adversity and challenges—into a coherent narrative about the self (Ochs & Capps, 1996). Narrations of illness or disability are a means of chronicling medical experiences but also a means of creating personal understanding around these experiences for the patient and the clinician (Kleinman, 1988). Moreover, narrative structure has provided insights into patients with severe psychiatric disturbances and a history of trauma (Josselson, 2004; Dimaggio, 2006).

24 The narratives in this paper are presented in the transcripts; the telling, however partial the self may be, offers a reality of the experience which is in turn interpreted by the authors of this study. The responses were embodied in the five perspectives on parental depression identified by the authors in a previous paper (Kaimal & Beardslee, 2010). The perceived impact on the self were manifested in this framework, but nuances were evident as the participants describe specific impacts on themselves. Some of these responses resonated with the literature, while others offered new insights into experiences of children of parental depression. Note that we do not ascribe any valence or value to any of the perspectives. Each perspective represents an aspect of identity and the life story narrative created by the respondent.

Resistance: No Impact, Minimization

25 Three female respondents and three male respondents indicated no impact of parental depression on their lives, or minimized any significant impact. Unlike in the perspectives of ambivalence and acceptance, which were elaborate and nuanced, these responses were not as complex or detailed. Some made references to learning more about the illness of depression and one even indicated that it was a positive experience, because it facilitated his desire to be more independent. For many respondents in this study, the relationship with the parent was close and supportive despite the presence of parental illness. An interesting pattern seen in the data was that respondents with their own history of depression had more resistant and negative perspectives on the perceived impact of parental depression compared to respondents who did not have a recognized history of depression. The examples of resistance and negativity seen in the respondents with their own history of depression raised additional questions about the role of depression in families and how it impacted the child. The resistance was manifested in attributing difficulties arising from depression to the self, rather than the parent, or making distancing intellectualized statements such as: “I know about the symptoms of depression,” when asked about the perceived impact of depression. These responses are not complex narratives like the perspectives of ambivalence and acceptance, where respondents make multiple connections.

26 An added dimension was the co-existence of resistance and compassion in these narratives. For example, the same respondents would deny any impact of parental depression on themselves and yet go on to say that they were more aware of these symptoms in others. Similarly, when asked about the perceived impact of parental depression, three of the four respondents (with a personal history of depression) made references to the impact of their own depression, rather than that of their parent. Another way we distinguished this in the narrative was to compare how expressive the respondent was in other aspects of the interview and whether that contrasted with the narrative style for the specific question on the impact of parental depression. In the cases where we coded it as denial/minimization, the difference was stark. It is possible that it was an accurate depiction of the respondents’ perception, but it seemed unlikely because of the lack of any explanation of why they thought so and how different their response was compared to the long detailed answers they provided to other questions in the interview.These issues surrounding the perception of parental depression are uniquely colored by the respondents’ own experiences. The difficulty in separating the influence of parental depression from their own experience of the illness was seen in many narratives. This parallels Ochs and Capps’ (1996) assertion that narrative and self are inseparable because they are both born out of experience and also shaped by experience. Thus the absence of a personal narrative, either through distanced intellectualization or denial of any impact, is akin to denying the existence of a self impacted by parental depression.

Negativity: Disempowerment and Disadvantages

27 The references to the negative impact of parental depression included parental inadequacy as role models, parental undermining of self-confidence, difficulties in social interactions, being forced to grow up before peers, eagerness to please others, and an inability to be assertive in interactions. This reference to negativity was presented as an ongoing issue rather than something that was resolved in any way. This temporal component of the narrative situates it as particularly relevant to children from families with depression. If the impact is negative and ongoing, then this has potential clinical significance. In addition, narratives help bring together the alienated and sometimes difficult aspects of a life story that might otherwise remain disconnected in the overall narrative (Ochs & Capps, 1996). Numerous studies have indicated that children of depressed mothers were more self-critical than other children and had difficulties with regulating emotion and social interaction (Downey & Coyne, 1990). However, the narratives in this study indicate that mostly boys, not girls, made references to such a negative impact on themselves. Only one of the eight girls identified a negative impact of parental depression on herself: the inability to be assertive in confrontations. Seven of the eight girls indicated that the impact of parental depression was either being sensitized to the needs of others experiencing low moods, or taking a more active role in helping their parents.

28 Another aspect to consider is the gender of the parent. In 14 of the 16 families, it was the mother who was the identified depressed patient. Sheeber, Davis, and Hops (2001) propose that daughters of depressed mothers are at additional risk as a function of greater familial and parent-child discord and poor maternal modeling. Alternatively, it is possible that the gender of the parent who is depressed might be impacting boys and girls differently. Petersen, Sarigiani, and Kennedy (1991) suggest that there is a steeling effect such that boys, compared with girls, are potentially less affected by family dynamics. The narratives in this analysis contradict this finding, as boys clearly describe many negative effects of family stressors. They also describe overcoming these stressors and gaining in maturity and self-mastery. The girls’ narratives do not present this negativity and also do not present much of a resolution, implying either that there is a differential impact or that there is no acknowledgment of any impact within the short period of analysis for this study. A related but underrepresented issue to consider is Luthar’s (1991) assertion of the unidentified “costs” or the toll that highly adverse or stressful life circumstances take on resilient adolescents. In a study comparing young adolescents with differing levels of exposure to stress, she found that even children who demonstrated high levels of resilient functioning had a higher incidence of anxiety and depression compared to those who had not experienced stress and adversity as children. This implies that stressful events took a toll on children, including those who appeared to be resilient and to be functioning well in school and in their peer and family relationships. Further study is needed, but it is possible that the negativity provides a window into some of the hidden burdens carried by otherwise high-functioning emerging adults.

Ambivalence: Conflicted Positive and Negative Attributions

29 A few respondents described the impact of parental depression in the form of two concurrent conflicting unresolved impulses. Examples included the desire to express anger but feeling unable to do so, or the desire to confront someone but being afraid of losing the relationship. Such conflicting perspectives reflected the ambivalence felt towards the parent. This is especially salient because these respondents otherwise referred to having very close relationships with their parents. This concurrent conflicting set of emotions mirrored the developmental challenge of emerging adulthood: trying to develop an autonomous identity while maintaining relatedness. Narrative engagement provided individuals in this context with a forum to elaborate on many facets of their existence, especially in regard to emotional experiences like those that may arise from parental impairment (Gilgun, 2005). Their perspectives might be unresolved, but emerging adulthood is associated with cognitive maturity, which in turn enables greater self-reflection and the ability to engage in complex forms of thinking, awareness of the subjectivity of individual perspectives (Labouvie-Vief, 2006), and the ability to articulate a coherent life story (Habermas & Bluck, 2000).

30 Ambivalence also highlights the complexity of relationships with a depressed parent, in that these relationships might not always be irreparably impaired (Puig-Antich et al., 1993) or perceived negatively (Kaslow, Rehm, Pollack, & Siegel, 1988; Stark, Humphrey, Crook, & Lewis, 1990), as indicated in the literature. The unresolved perspective holds together many difficult emotions, multiple perspectives, multiple narrative selves, and difficult emotions associated with parental depression. The articulated awareness of multiple aspects of the relationship, without resorting to simplistic representations like resistance or negativity, could also indicate an effort to engage in reflection and self- awareness. These multiple perspectives in the narratives are indicators of maturation (Hermans, 1996). In terms of narrative complexity the multiple selves are not yet ordered and integrated into a chronological sequence. Opportunities for retelling the story, integrating new insights and new experiences, as well as narrative interactions with parents and significant others that the emerging adults encounter might perhaps help create some resolution of this ambivalent narrative.

Acceptance: Disempowerment and Mastery/Reconciling with Loss

31 Acceptance of the impact of parental depression on the self included parallel narratives about loss and self-mastery. The negative impact of disempowerment included having to grow up faster, an early maturation, and difficulties in social interaction. As one male respondent said, “I might be 19 but I feel like I am 25.” The narratives of early maturation indicated a loss in the form of a shortened childhood or a faster road to maturity, compared with peers. In fact, the early maturation involved in being responsible around the house or for siblings was described in negative terms because it conflicted with what the participants viewed in the experiences of their peers from families without depression. The negativity, however, existed with reference to the past, not the present. In the present, the respondents described themselves as competent, responsible, and mature. Although their experience of childhood was different from that of their peers, their present was also different in terms of their perceived maturation. The narratives had none of the ambiguity of the other responses towards parental depression and these respondents were unquestionably affected by parental depression.

32 The act of narration engages participants in ongoing efforts to understand and incorporate new experiences and events into the story of their lives, to integrate and impose order on otherwise unconnected events from the past and present (Ochs & Capps, 1996). This gives new meaning to former understandings of the self, both as an individual and as a product of the larger family unit in which the individual is situated. The chronological placement of the impact was presented, as something of the past is especially relevant because it provides evidence of the potential for narrative to create order from disorder (Ochs & Capps, 1996), and as in many of the cases in this study, adverse experiences. Moreover, as Arnett (2000) and Dubas & Petersen (1996) argue, the very act of leaving the home promotes psychological growth and modifies the parent-child relationship to be that between two adults rather than between a child and an adult. This was most evident in this perspective of acceptance in the perceived impact of parental depression.

Compassion: Sensitivity, Kindness and Caretaking towards Others

33 Many respondents described the impact of parental depression as having developed the ability to be aware of others’ moods, and becoming more caring and responsive to the needs of others. The sensitization to moods in both themselves and others was narrated by both boys and girls and was portrayed by some as a positive impact, not a negative impact, of parental depression. This perceived impact of parental depression is not portrayed often in the literature on families of children with depressed parents, as it focuses on the insecurities, low self-esteem, and other negative reactions to parental depression.

34 An interesting aspect of the sensitization to others was the similarity it bore to a resistance to any perceived impact of parental depression on the self. Compassion was very similar to resistance when any discussion of a negative impact on the self was excluded. Further study is needed to better understand this, but one similarity was the simplicity of the narratives in both compassion and resistance. There weren’t many explanations, extensive descriptions, or clarifications in either of these perspectives. One difference, however, was that in compassion, the respondents were able to separate the illness from the individual. In resistance, the respondents tended to combine the depression and the relationship into one and say that there was no impact. In compassion, however, the respondents were able to distinguish that the illness was a part of their parents’ life but not what defined them completely. Borland (1991) identified this issue in her examination of conflicting interpretations of oral narratives and the challenges of researcher-led analysis of oral narratives. It is possible that further follow- up interviews might shed light on this connection between compassion and resistance.

35 The focus on the sensitization to others to the exclusion of any negative impact was seen in the narratives of almost all the girls. Although both sons and daughters of depressed parents attributed a greater sensitization to parental depression, few girls expressed any negativity towards their parents with respect to their depression. In response to the perceived impact of parental depression, most of the narratives revolved around caretaking and sensitivity to the needs of others. Josselson (2004), in the case study of a patient, provided a complex, detailed, and coherent story about her life but it became clear to the therapist that it was a “forced story” that the respondent was regurgitating and it did not include any of her own perspectives or views. This might indicate a possible narrative that the girls have internalized as a socially desirable response to parental depression. Further study is needed to determine whether this indeed might be the underlying dynamic in the narratives from the girls in this study.

Limitations and Conclusion

36 All findings in this study must be interpreted cautiously because emerging adult children who participated in this study were more informed about the signs and symptoms of depression than those who dropped out of the study or those who were not part of the study. Those who didn’t have the opportunity to share their perceptions and narratives might have presented very different, or less descriptive, narrative perspectives on parental depression. The sample is also not very diverse. All respondents were Caucasian except for one, who was African American. Most of the respondents were from middle-class to upper- middle-class families. Socio-cultural and socio-economic differences in the perception of parental depression are not represented by this sample and are an important limitation of both the preventive intervention study and therefore this study.

37 The data for the preventive intervention study was collected and archived prior to the initiation of this study. But the data were secondary, and therefore it was not possible to ask additional questions of the respondents, which in turn could have contributed more to the research questions in this study. Only transcribed narratives were used in the analysis to extract emergent themes. As thematic analysis was the focus of this study, additional aspects of the discourse, such as pauses, humor, etc., were not analyzed in depth. Moreover, the interviews were not conducted by the author, and therefore there is no additional information about the respondents’ demeanor, facial expression, body language, and interpersonal or interactional style that could have contributed additional dimensions of an individual’s experience of parental depression. The associated quantitative data and narratives from other family members, notes from research staff, and biographical data from other informants were also not used to triangulate the narratives from the respondents.

38 To conclude, the perception of the impact of parental depression varied amongst emerging adults. This analysis examined narratives from a small sample of sixteen emerging adults. Some findings that are important to consider include young adults with their own history of depression reporting a more resistant or negative perceived impact of parental depression, a perceived early maturation due to parental depression, and more boys than girls narrating perceived negative impact of parental depression on the self. The girls mostly did not refer to any significant impact on themselves but focused instead on being more aware and sensitive to the needs of others. A key point that reiterates the protective role of healthy relationships is that experience of parental depression was not always found to have a negative impact, as revealed in the narratives of the children.

Appendix

39 Semi-structured interview questions; young adult interview questions after 18 years:

I. Family Relations

- Where are you living now? (If the subject is no longer living with the family of origin, ask about their current arrangement. If the subject has moved out during this interval, ask how the transition has gone.)

- Has anything changed about who is living in your parents’ home? (If there has been a change): How has this impacted you?

- Are there things you enjoy doing with your family?

- How have things been going for your family?

- How would you describe your relationship with your mother? What is it you like about your mother?

- How would you describe your relationship with your father? What is it you like about your father?

- How would you describe your relationship with your sibling/s? What is it you like about your sibling/s?

II. Transition to Young Adulthood

- Looking back, how did the transition to higher education or employment go for you?

- How concerned were you about being ready to live away from home?

- How stressed were you in the first few months living away from home?

- Did you worry about your parents or other family members when you moved away from home?

- What impact if any has growing up in a family with depression/ difficulties had on your relationship with others your age?

- What impact if any has growing up in a family with depression/ difficulties had on your relationship with your sibling/s?

- What have you learnt from your experience that might be helpful to other kids growing up in similar situations?

III. Life Events: Coping

- You told me about (major life event) that happened. Different people have different things that are difficult. Which things are hard for you?

- I’d like to find out more about what helped or how you coped.

IV. Experience of Parental Illness from the Young Adult’s Point of View

- What is depression? When a person is depressed, what are they like? (How do you know when someone is depressed? What are the symptoms of depression?)

- What is mania (manic-depressive)? When a person is manic, what are they like? (How do you know when someone is manic? What are the symptoms of mania?)

- Has either of your parents been depressed, manic, or otherwise been having a hard time with their feelings since I saw you last? What about in the past?

- Have you ever worried you might be experiencing symptoms of depression/ mania? Can you tell me a bit about it?

- Have you used mental health services since you left high school? If yes, what type? How satisfied were you with the help you received?

- How would you (did you) recognize depression/mania/both in your mom/dad/siblings?

- Has either of your parents and/or siblings been seeing a therapist, taken medications or been hospitalized for depression/mania/both?

- What is it like for you when your parent/sibling/s is depressed?

- How do you feel when you your parent/sibling/s is depressed?

- Do you do anything differently at these times?

- Sometimes when a parent/sibling is ill it is hard to do the things people usually do. Was it hard for you? How did you cope?

- At this point what do you think caused your parent to be depressed?

- Are there things that seem to make your parent’s depression/mania better?

- Sometimes people feel that it is their fault or someone else’s fault when there is a depressed person in the family. Does this ever happen to you?

- Have your parents ever talked with you about the issue?

- Looking back, what sort of impact has having a parent with depression (mania) had on you (e.g., childhood experiences, activities, increased responsibilities, changed the way they see the world)

- What were the biggest challenges you faced during adolescence?

- Do you think those challenges were different because your family has dealt with depression/family issues? If yes, how?

- Who else in your family talks about the illness? Have you talked with your non- ill parent? Have you spoken since we last met?

- If you did talk, who starts the conversation? What do you talk about? How helpful was it to talk?

V. Conceptualization of Personal Depression

- The last time we spoke you were…(description of how subject was feeling ). How have things been since then?

- When did you begin to feel better/worse?

VI. General Coping

- Sometimes things happen that make it hard to do the things you usually do: everyday things such as concentrating on your school work, getting to work, doing your school work, spending time with friends, talking with your parents, eating or sleeping. Different people find different things difficult. What is hard for you?

- Different people get help or help themselves in different ways. How did you cope?