Articles

Life Stories in Context:

Using the Three-Sphere Context Model To Analyze Amos's Narrative

Despite a wide theoretical consensus among narrative researchers about the importance of referring to context in analyzing narratives, it seems that the various contexts at work in individual life stories and the specific methodological implications of the importance of context are not that clear. In this paper, I will describe a model for context analysis, which refers to three distinct spheres of contexts in which narrators situate their life stories (Zilber, Tuval-Mashiach, & Lieblich, 2008). The first context involves the immediate inter-subjective relationships within and involving which a narrative is produced; the second comprises the collective social field in which a life and story have evolved; and the third surrounds the systems of broad cultural meaning or meta-narratives that underlie and give sense to any particular life story. In the second part of the paper, I will illustrate the three contexts in Amos's story, and claim that viewing his story as it is embedded through these three contexts not only situates it within a more general social framework, but also enables a deeper understanding of his identity and the core themes of his life-story.

1 In keeping with the social constructivist philosophy which underlies qualitative research, qualitative methodologies call for a "pluralistic" stance in the analytic process (e.g., Frost and Nolas, 2011). A pluralistic stance holds that the employment of more than one qualitative approach helps one gain a broader spectrum of meanings of the studied phenomena. Indeed, in the last few years, several demonstrations of different qualitative approaches to the same text have been published (e.g., Frost et al., 2010; Wertz et al., 2011). But within narrative research, the current issue is the first effort to apply different analytic tools to a narrative text. I wish to contribute to this joint effort by claiming that a contextualized reading of a narrative adds important insights to the analytic process. I will analyze Amos's narrative using a model for context analysis.

What Is Context, and Why Is It Important?

2 Learning about people and their lives and identities within the context in which they live is one of the main aims of qualitative research. When interpreting human behavior, qualitative researchers emphasize the importance of taking into account various aspects of the environment, including physical, ethnic, historical, ideological, and gender aspects (e.g., Bruner, 1990; McAdams, 1993; Polkinghorne, 1988), and many claim that context is part of the definition of qualitative inquiry (Marecek, 2003). The importance of taking context into account is justified by the narrative assumption that individuals cannot construct their identities in a void; rather, they do so by using the social and cultural scripts and norms available to them as a repertoire from which they choose. Therefore, one’s life story is never just an expression of a unique and “private” identity; at the same time, it doesn't need to fully conform to social conventions (Zilber, Tuval- Mashiach & Lieblich, 2008). Rowland-Serdar and Shwartz-Shea (1997) nicely describe this tension:

According to this line of thought, an explicated examination of context has the potential to supply the tools for understanding the narrator's motivations, values, and meaning systems as well as the boundaries within which his/her identity is constructed. Furthermore, although context exists in all research and regardless of the method used, its examination may be more accessible and easier when the method used is the narrative method and the collected data is stories. This accessibility and ease may be due to the holistic aspect of stories, which enables the weaving together of individual and collective influences along a temporal dimension (Spector-Mersel, 2011). However, despite widespread agreement regarding the importance of context in qualitative and narrative analysis, the epistemological question of what constitutes context, and its derivative methodological question of how to analyze it in the narratives under study or which contexts are relevant to a specific analysis, still lack clear answers, leaving the topic obscured. For example, the definition of context as "the set of circumstances or facts that surround a particular event, situation, etc." (Collins English Dictionary) demonstrates just how endless context can be, since the question of what circumstances or what facts, among the endless facts surrounding each event, should be looked at is left open. As a result, defining what context is (or isn't) is always a relative, situational decision, which depends on the researcher's theoretical stance, his or her sensitivity, the research texts, and the nature of the qualitative data (Marecek, 2003; Stenvoll & Svensson, 2011).

3 Alongside these tensions and debates regarding what context is and is not, the growing theoretical agreement that narratives are always situated and bound in different contexts has eventually led to a complementary methodological effort to suggest ways to analyze contexts and examine their contribution to the understanding of identity. Among the contributions to the literature on contexts are Plummer's (1995) sociology of stories, which maps the historical and cultural contexts within which stories develop; the work of Potter and colleagues (Potter, 2003; Potter, Stringer, & Wetherell, 1984) on situational context in discursive psychology; and Tedlock's (2003) treatment of context in the field of autoethnography. Each of these strategies for the analysis of context was developed separately with a specific approach, highlighting aspects relevant to that approach. For example, sensitivity to the context of the interaction emerged in approaches wherein an interview or a discourse supplied the main texts for analysis (namely, narrative inquiry or discourse analysis). In what follows, I will outline the Three-Sphere Context Model for context analysis, developed by myself and my colleagues (Zilber, Tuval-Mashiach & Lieblich, 2008), and then analyze Amos's narrative(see Appendix) using this model. The presentation here provides a summary of the model; a fuller discussion of the model and its implementation may be found in (Zilber, Tuval-Mashiach & Lieblich, 2008).

The Three-Sphere Context Model

4 The model was created based on existing research literature in various disciplines (mainly linguistics, sociology, and psychology), as well as our reading of life stories collected in interviews in different settings. We suggest a three-sphere model:

- The immediate inter-subjective relationships in which a narrative is told;

- The collective social field in which one’s life and story evolved;

- The broad cultural meaning systems or meta- narratives through which a life story is told.

The Inter-Subjective Relations

5 Any text is constructed “in connection” (Jordan, Kaplan, Baker Miller, Stiver, & Surrey, 1991)—that is to say, within social relations. As a result, our identities may be seen as the summation of the relational encounters we have with others (Gergen, 1984). Polkinghorne (1988) claims that:

Within narrative psychology we deal most often—but not exclusively —with life stories that are told in an interview situation, and thus, the relationship between narrators and their interlocutors is indeed relevant for the understanding of the story. The inter-subjective context encompasses the usage of language (the very ability to understand each other); the moods, intentions, and motivations involved when telling a specific narrative; and the relationship between interviewee and interviewer. Thus, a story might contain references to the relationship within which it was told (e.g., the interview situation). We expect these references to be concrete: i.e., to deal with the relations between the teller(s) and their listener(s) at the time of the telling. Furthermore, this relationship affects the choices of the teller: what to tell, how to tell it, and what details need elaboration (in their perception). Even when not explicitly referred to in the text, we should read the story looking for the assumed context of the connection within which the story was constructed. Awareness of this context at the time of the interaction is not necessary, although it is often possible to identify textual markers that may belie the context (e.g., in comments or clarifications to the interviewer), or the dynamic of the interaction.

6 Guiding interpretive questions: In an interview situation, for example, we need to know a variety of significant factors, including what the interviewee knew about the aims of the interview; the background of the interviewer and her connection to the topic of the research; where and when the interview took place and why; who was present; and whether there were any prior relationships between the parties. These aspects of the interaction may affect the choice of contents included or omitted by the narrator; the narrative ordering of events; and his decisions to disclose or hide personal experiences, or to emphasize or de-emphasize certain topics over others. For example, if the interviewee feels that the interviewer is interested in specific answers, rather than in the interviewee's spontaneous experiences, it may lead him to give short, laconic answers. The inter-subjective context affects the interviewer as well (e.g., through the emotional atmosphere in the interview which may lead him to change his original questions), and both, in turn, impact the final text. Thus, knowledge of the immediate context is essential for understanding the story, and it should be accounted for in each specific interpretation.

The Social Field

7 The social field relates to the socio-historical context within which a life was or is being lived. Schiebe (1986) claims that:

Our treatment of the social context is somewhat different than those of sociologists (including Bourdieu’s field theory, 1992/1996; Giddens’ structuration, 1984) who refer to both the symbolic and material aspects as being part of social context. Our model differentiates between the social material aspects, and the symbolic-cultural context, which we term cultural meta-narratives, as I will describe later.

8 When narrating their lives, people situate their stories within certain social structures and historical events. Their choice of the relevant social field is meaningful and may be interpreted to indicate what they see as relevant or important for their identity. Identity stories contain explicit and implicit references to the social context relevant to the narrator’s experience of his/her life. People often reflect on the socio-historical context, thus introducing collective events and public figures into their story. These references will usually be concrete, dealing with institutions and structures in the immediate social and political environment and in relation to the historical moment or to historical or mythical events and figures. We expect such references to be especially explicit when the narrator and his/her interlocutors do not share the socio-historical context. In such cases, both parties are aware of the need to elaborate, detail, and explain the socio-historical context. When narrators and their interlocutors share the same social sphere – even though holding different positions within it—this context may be taken for granted and not referred to explicitly. The researcher is expected to be reflexive regarding the social field and its effects on the story.

9 Guiding interpretive questions here may be, for example: What historical events are mentioned? How local or public were these events? What historical events which might be expected to be mentioned are missing from the text? Does the narrator place her narrative? Which social groups appear in the narrative? Which social structures or institutions are described? And how does the narrator relate to them? The social context may shed light on whether or how a narrator identifies with a collective, which social identities hold relevance to the narrated identity, and the social networks with which the narrator feels affiliated.

Cultural Meta-Narratives

10 The request to talk about one's life invites people to tell their own personalstory. Yet one’s culture affects this narrative construction by providingnarrators with collectively shared meaning systems—narratives abouthuman nature, human behavior, and history—that serve as templates orscripts for individual stories (Polkinghorne, 1988, p. 153; Wertsch &O’Connor, 1994). Meta- narratives are webs ofmeaning that reflect cultural themes and beliefs that give a local story itscoherence and legitimacy. Because each culture holds various meta-narratives,narrators use multiple cultural resources as “tools” for creating their line ofaction (Swidler, 1986) and their line of narrative. Each story may echo one or more meta- narratives, local or universal. Again, it is important to remember that the narrative is not a mere assimilation of cultural norms and conventions; rather, it presents the tension between the uniqueness of the individual and his or her culture. Bruner (1990) says that:

As societies and sub-groupsdiffer in the meta-narratives that characterize them, the cultural contextneeds to be explicated in each case to follow the dynamics of the personaland the collective in a specific life story.Usually, meta-narratives are not consciously acknowledged by the teller,nor do they appear explicitly in the text. Rather, meta-narratives constructthe story and shape the plot or are used without the narrator’s explicitacknowledgement. They are to be extricated bottom-up through interpretive moves. They are discovered (and reconstructed) by reading and comparingmany stories and abstracting general cultural patterns (plot lines,figures’ roles, moral lessons, typical scenes, etc.) or brought in by theresearcher while implementing insights from the research literature.

11 Guiding interpretive questions here may be, for example: What are the meaning systems that provide sense forthis story? What do we know, or believe, that makes this story sound plausible to us?

The Three-Sphere Model in Context

12 The Three-Sphere Context model was developed alongside other theoretical efforts to describe different contexts within which narratives are embedded. One of the most thorough descriptions of stories in context is the "sociology of stories" (Plummer, 1995). Plummer (1995) views stories as symbolic interactions, and his focus is not on the individuals who tell the stories, nor on the texts themselves, but “in the interactions which emerge around story telling” (p. 20). In his mapping, Plummer refers to the story in the most general way, as one which can be created in many ways, such as through the media, in a casual conversation between friends, as a work of art or literature, or in a research interview. This expansion of the circumstances of the story creation enables him to then suggest several levels of inter-subjective contexts (e.g., between narrator and interviewer, or between narrator and coaches and coercers), who encourage the telling, but are not necessarily part of the telling interaction, or between the author of an autobiography and his readers. Although both the Three-Sphere Context Model and Plummer's model refer to the three levels of the interaction, the social context, and the cultural context, they differ in their focus and scope. Indeed, the three- sphere model is aimed specifically at oral narratives, and mainly those produced through interviews, and its focus is on understanding the narrator's identity and choices as they are shaped and embedded in the contexts in which he lives (Zilber et al., 2008).

Contextualizing Amos's Story

The Inter-Subjective Context

13 I begin my analysis of Amos's story with the inter-subjective context. Here I am interested in learning how different aspects of the immediate interview environment shed light on Amos's identity. A rich analysis of this context, however, requires a detailed description of the interaction between narrator and interviewer, including non- verbal behaviors, the emotional atmosphere, changes in tone and intonation, and bodily positions and movements. Since our decision as authors of this joint issue was to receive the text in its rawest possible form—in order to portray our impressions and analyses as openly and independently as possible—most of that information is missing here. In most cases, as researchers, however, we conduct a study in which we are both the interviewers and interpreters of the findings and therefore do have access to this information and can use it in our analysis.1 Nevertheless, we do know some things about the interaction: we know that Gabriela Spector-Mersel (2014a; the interviewer) informed Amos about her research question, and that Amos knew that the research purpose was to learn about his experiences with his personal caregiver. Interestingly, his life-story tells us very little about this topic.

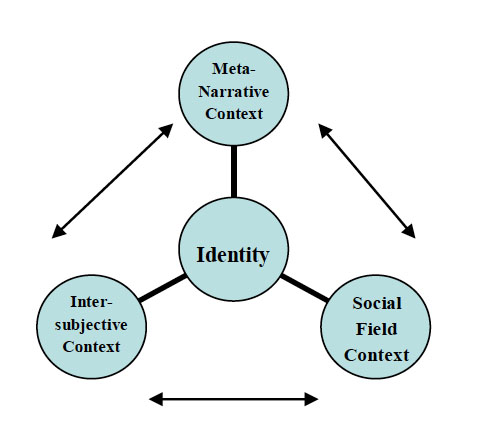

14 Within the interaction there is a series of apparent contradictions between Spector-Mersel and Amos. Amos is physically limited; he is wheelchair-bound and dependent on his caregiver. Spector-Mersel is healthy, independent, and commutes freely. Amos is 85 years old; Spector-Mersel is almost 50 years younger. Amos is a man; Spector-Mersel is a woman. She is the researcher who brings up the topic. He is the interviewee who is asked to respond to her questions and abide by her research agenda. In terms of the power relations between narrator and interviewer, there is, at least on the surface, an imbalance between the two partners. This imbalance is partly due to the unavoidable power relations that always exist in research, as it is the researcher who chooses the topic and the sample, asks the questions, and ultimately decides what to publish (Karnieli- Miller, Strier, & Pessach, 2009). This “performed” tension in the interaction between Gabriela and Amos seems to parallel the major tension in Amos's identity as it emerged in the contents of Amos's narrative, between being independent and agentive, on the one hand, and being dependent and passive, on the other, as other analyses of the text in this issue have convincingly showed (e.g., Perez and Tobin, 2014).

15 However, despite the obvious differences described above, Amos is active in narrating his life story. He starts his story spontaneously, without needing or requesting further instructions (as many interviewees do in the first stages of an interview). His story does not refer directly to the research question and he places the focus of his story more on his past, prior to his stroke. He tells his story and then asks Gabriela if it was interesting. The picture of an active, engaged agent emerges.

16 To summarize, what does the first context add to our understanding of Amos's identity? From the inter-subjective context it appears that there is a gap between the explicit content of the narrative, at least after the stroke (which is about dependency, loss of agency and control, and disengagement) and the relational context of the interview interaction, in which Amos seems active, independent, and in full control of the situation. How can this tension be resolved? At this point we will leave the question open, and return to it after analyzing the two other context spheres.

The Social Field Context

17 The second level of analysis—the social field context—relates to the social world in which a story is embedded. When I read a narrative through the prism of the social context, my reading is focused on the relations of the narrator with others in his or her life, his or her affiliations with social institutions, and his or her identifications and values, as described in the text. Reading Amos's life-story, a few immediate impressions emerge: it is a condensed and very factual and descriptive text, filled with names, geographical locations and social organizations. We don't hear anything in this narrative about Amos's emotions, motivations, or justifications of the life choices he has made. Although this result might be a product of Spector-Mersel’s choice of interview approach—i.e., an initial interview in which Amos was invited to provide a summarized version of his life—it is still interesting to note that even at the factual level, Amos barely refers to the other people in his life, including his children and friends (except for a brief mention of his marriage to his wife, who was with them in the room at the time of the interview), or to fields other than his professional life. His story is only about his work—irst his work in the army; subsequently his career—and the loss of his career after he underwent a stroke and became paralyzed.

18 In order to illustrate the contribution of context analysis, I suggest reading Amos's narrative twice: first without referencing the specific meanings of the names and institutions mentioned; namely, without reference to the social context. The second reading, however, will be a contextualized reading, i.e., the social signs will be included and made available for interpretation.

19 For a first reading, in order to avoid an analysis of the social context, I replace each reference to a place or institution with an alphabetical letter. The text then looks like this (for the sake of space, I am using only a small extract from the text, but the reader is encouraged to apply it to the whole narrative):

Such a reading advances a greater sensitivity to the formal-structural aspects of the narrative (rather than to its contents, e.g. Lieblich et.al, 1998), due to the omission of details about the content. The reader is left with the impression of a dynamic and energetic movement between places and environments and through time, with a fast pace and clear progress being made. The narrator is portrayed as very competent and active, and he shows initiative in pursuing his life path; on those occasions when he is chosen for a job, he still makes the active decision to accept. This is a prototypical Western male narrative (Gergen & Gergen, 1992; Tuval-Mashiach, 2006).

20 But Amos's stroke cuts the text into two drastically different sections, and in the second section there is no mention of any places or affiliations, no changes in himself or in his life, and no movement of any kind, physical or ideological. It is as if time itself has suddenly stopped, and life is lived in a long unchangeable present, without a past or a future.

As I wrote earlier, this analysis doesn't require an understanding of the context. Even without understanding the meanings of the social institutions, such an analysis could have been conducted by any reader, even one who is a stranger to Israeli culture and its social nuances.

21 What then does awareness of the social context add to the understanding of Amos's identity?

22 As is detailed by Gabriela Spector-Mersel (2014b), the institutions and milestones mentioned in Amos's narrative represent all that is Israeli, or in Spector-Mersel's words: the “Sabra” image. Within the social field context, Amos's identity as an active competent man is now charged with the unique meanings identified with being a “Sabra”—namely, being one of the founders of the state of Israel, belonging to the heroic “1948 generation” group who fought for the independence of Israel and were later involved in establishing and leading the army and the central civic institutions. The values guiding the “Sabra” generation are a strong belief in Zionism and the return of the Jewish people to Israel, and are based on collective ideologies rather than on individualistic ones (Spector-Mersel, 2010). Therefore, even though Amos's story may appear to conform to the prototypical male success plotline, it actually represents for the narrator not his own personal success but that of his social collective. His choices and deeds are motivated by and directed towards the needs of the collective, not his own. As the text implies, Amos's identification with the collective (at least before his stroke) is very high: he serves in the army and later chooses to live in a kibbutz, which at the time was considered the purest actualization of collective life in Israel. He works in the kibbutz institutions and throughout the years remains involved in public affairs, until his physical situation suddenly changes. Only on one occasion do we suspect that there might be a gap between his own priorities and those of the collective: when he describes a career move that seems to have been dictated by the needs of the collective. But he immediately corrects himself: “After that (they) assigned me—(they) assigned, [corrects himself] I took on the task of establishing a factory, and I established the factory” (25-27).

23 The embodiment of Amos's identity as a “Sabra,” therefore, not only defines him as an individual but also as part of a social world which includes affiliations and networks of belonging. By being part of the joint effort and the founding generation, Amos is granted membership into the social milieu which surrounds him. The second part of his narrative, however, sees a significant departure: since his stroke 15 years ago, he is not engaged in any public activity and even avoids activities that are part of the daily routine in the kibbutz, such as eating in the communal dining room, or participating in the kibbutz meetings.

24 The sharp distinction between the two stages in Amos's life story is striking: it is as if there is no continuity at all between who he was before and who he is today. There is no single activity or description that continues from his past to his present. This discontinuity is surprising, as generally people tend to narrate their lives as if they were a coherent and continuous unfolding series of events (e.g., Bruner, 1990; Linde, 1993).

25 Shortly, in my discussion of the meta-narrative context, I will look at some possible explanations for this change in Amos's narrative. In the meantime, the analysis of the social field context demonstrates that for Amos, being young, healthy, and active ensured not only self-esteem and self-assurance but also the ability to be part of something that was bigger than he was (Zionism), and to belong to the social networks related to it. Therefore, when Amos underwent his stroke, he not only lost his independence but also his social life, affiliations, and relations with non-family members. In his words: “I was active, I was a member. […] I got sick, so it took me out of the…frame” (51; 55-56).

The Meta-Narrative Context

26 At this level of analysis, the analytic effort focuses on deciphering the systems of cultural meanings and values as implied by the text. In Amos's text there are several possible meta-narratives underlying the spoken one. To illustrate the analysis of meta- narratives, I have chosen to focus on explaining the two-stage structure of Amos's narrative and the tension between its two parts.2 I will refer to four interlinked concepts, which together create the dissonance between the two parts of Amos's narrative: aging, masculinity, being old in Israel, and the trauma of stroke and chronic illness.

27 Amos's narrative is, among other things, a narrative about aging. The differences between the two parts of his story might reflect the tension between being young and getting old. As has been convincingly claimed elsewhere (e.g., Hazan, 1994; Spector-Mersel, 2010), in western societies elderly people are generally perceived uniformly as weak, deteriorating, and inefficient. As such, Amos's old age is conceived as a mirror image of the youthful, competent picture which emerges from the first section of his narrative. However, the notion of getting old is itself contextualized, since it intersects with gender, social norms and values, and nationality (Harevan, 1994; Hazan, 1994). Adding the gender aspect, it seems that Amos's masculinity is also threatened by his growing old. In this sense, not only does his ill and dependent condition contradict commonly-held perceptions of masculinity (Connell, 1995), he also lacks a proper framework within which to locate himself as an elderly man. As Spector-Mersel (2006) writes,

Additionally, there is a cultural component. At one time, Amos — belonging to the cohort of Israel's founders—exemplified the very essence of the “Sabra,” being strong, independent, and healthy. Now he is old and dependent, and stands in direct contrast to the young country of which he was a founder, in direct contrast to the ideas held by the “new Sabra.”

28 The last of the four interlinked concepts are disability and illness. Amos's two-stage narrative is prototypical of people who experienced trauma and whose life has changed drastically as a result (Wigren, 1994). The transition from being physically healthy—free to move, and plan and behave as he wishes—to a state where each step requires planning in advance and constant help from others is an extreme change. This change is reflected both in the content and the form of the narrative. The narrative changes from a dynamic meaningful account of Amos's life to a static narrative, frozen in time. This is a tragic narrative reflected in the rift between the two parts of the story and in Amos's acknowledgement of the gap between his intact mind and his disabled body:

and forth between thinking that I’m healthy and the future, that I’m limited. And that’s it, it’s already…15 years. Essentially sitting in the chair. And that's a long time. Very long.

[…] And this is how I

go through my life. I don’t have much more than that now.

(45-48; 49-50)

In sum, the qualities of being a man in Israel, belonging to its founding generation, and coping with a chronic disability have all combined to make Amos's aging process difficult and painful, and they account for the abrupt sense of discontinuity in his story. The meta-narrative underlying his story is that of the difficulties old age creates and the disengagement it forces on the individual's life and affiliations.

The Three Contexts in Amos's Narrative: Is There a Common Thread?

29 Analysis of the three contexts adds different layers to the understanding of Amos's identity. The first context—inter- subjective—adds to the understanding of how Amos handles the tension between being potent and agentive, and between being passive and dependent, in the context of the interaction itself. The second context—the social field—reveals the meaning systems which led Amos to make the life choices he makes; they also reveal how Amos's strong identification with the social norms of his particular world led him to become a full member of its social institutions and field. However, Amos's story is also about the disengagement, loneliness, and loss of membership in the social and public affairs sphere to which he belonged, in the aftermath of his incapacitating illness. The third context—meta-narrative—sheds light on the more general concepts and truths Amos holds. There is a disconnect in his narrative, between his life before the stroke and after the stroke, as if his story were the story of two different people.

30 I would like to suggest that these three contexts all point to disengagement and overcoming it. Or, in other words, all three contexts relate to Amos's struggle to recreate relationships: with the interviewer, with his social environment and affiliations, and with his present life, so that his life-story becomes one continuous story. Using Myerhoff`s (1982) metaphor of re-membering and Michael White's (2005) elaboration of this concept in narrative therapy, I would suggest that through the process of narration and remembering, and within the inter-subjective context of the interview interaction, Amos is re-membering his past, his present, and his current self to prior embodiments of himself. In doing so, he gains membership in his former life as well as the agency and authorship of his life story.

Reflection and Concluding Remarks

31 My initial response to the idea that each of us would write reflectively about our analysis was that it felt strange. Ordinarily, in my experience, the interview interaction and analysis are intertwined because I myself do both during the research process. Here, however, I had to analyze a life-story without knowing the narrator and without being close to the research question which guided the interviewer or the population her research addressed. I therefore felt somewhat estranged from the text upon my first readings. Nevertheless, perhaps as a result of my experiences with my own parents—who also cope with health challenges related to old age—I found it easier to identify with Amos. I found his life-story to be both inspiring and illuminating, in terms of the experience of those who established the state of Israel. Yet it was also difficult to see the tragic direction Amos's life and narrative took due to his stroke, and especially the void in which he lives his life now, according to his description. Such tragic stories are not new to me since in my clinical work I often hear trauma patients narrating a two-stage story (life before and after the trauma). However, I usually hear these stories in the context of therapy, as a starting point from which both the patient and I share the efforts and hope that there are other, better stages waiting to unfold in the future. The fact that Amos narrated his life-story in the research context— without the motivation or hope for change—left me with sorrow. Having said that, I am aware that Amos chose to participate in the study and to tell his story and that he was glad to tell it and believed it to be interesting (as was implied from his question to the interviewer at the end of the interview), and this helped me see his strength and agency. I should also say that my feelings towards Amos and his life- story might have impacted my analysis in ways that prompted me to search for evidence of the agency and free will available to him despite his difficult condition.

A Few Last Comments about the Analysis of Context

32 All contexts address the question of "why" a certain identity claim is made. Each level of context offers a different mechanism involved in shaping and reconstructing identities: from the more concrete level of immediate behavior, impressions and relations in the inter-subjective context through the social field level of values and ideologies which charge the life path with specific meanings to the meta-narrative level of the more abstract, general and at times universal truths and norms. However, despite this somewhat linear presentation of the model here and elsewhere (Zilber et. al, 2008), it now seems to me that a more circular conceptualization is accurate because each of the contexts not only explains the narrator's identity but also adds to the understanding of the two other contexts, as well as enriched by each of the other contexts (see Figure, below).

33 It is important to bear in mind that the analysis of contexts is ever-evolving and endless. For example, juxtaposing Amos’s narrative with other participants’ stories in this unique sample would have supplied yet another kind of context with which the understanding of Amos’s identity and life could have been enriched. In addition, reflection itself may be considered another level of context analysis, a level which exists between the reader and the text. The research question and the theoretical lens the researcher uses are two more factors that impact context. That is to say that the Three-Sphere Context analysis model is not meant to be exclusive; rather, it aims to offer a systematic consideration of several contexts. In addition, the explication of different contexts depends on the type of narrative product being analyzed: some narratives are richly embedded in one context but supply very little data on another. Therefore, the analysis of context is itself a contextualized act.

34 Text and context are like a reversible figure and ground: both create the whole, and yet at any given moment we can only focus on one. Thus, I focus here on reading for context. Although context is treated here for pragmatic reasons as though it was constant and separate from the text, it’s important to remember that context is dynamic, socially and politically embedded, and ever-evolving.

35 Finally, narrative analysis is by nature a process of zooming in on the text in question with a greater sensitivity to text nuances, both in terms of form and content. In this paper I suggest that a deeper understanding of identity and life stories may be gained by adopting a complementary zooming out approach: one that views identities within the wider environments in which they are embedded.

Rivka Tuval-Mashiach, PhD, is a clinical psychologist and senior lecturer in the Department of Psychology and the Gender Program at Bar-Ilan University, Israel. She is also head of the community services unit of NATAL, the Israel organization for the treatment of national trauma survivors. Her research fields include coping with trauma and stress, identity challenges and identity re-construction in coping with trauma and illness, narratives of gender, and the development of narrative theory and qualitative methodologies. She has published numerous papers and co- authored the book, Narrative Research: Reading, Analysis and Interpretation (1998), with Amia Lieblich and Tammar Zilber), and the book Narrative Research: Theory, Interpretation and Creation (2010; Hebrew), with Dr. Gabriela Spector-Mersel.

Appendix: Amos' Story*

- I was born in Poland. I came at the age of two. I came -- (they)1

- brought me. We at the first stage, because my mother’s family

- mainly, were in Balfur,2 so we came to Balfur for a few years. After

- that we moved to Tel Aviv. In Tel Aviv I was…I studied at the Beit

- Chinuch, the A. D. Gordon Beit Chinuch, and after that at Chadash3

- High School – continuation. And…secondary school. And I was a

- member of the Machanot Olim.4For a long time. Within this

- framework I was sent to the Palmach.5 Because then we had reached

- the point that all Hachshara6 provided a quota for the Palmach. It

- was still before (they) had recruited all the Hachsharas. And I was in

- the Palmach, from the year…’42…no…don’t remember, ’42. I was

- in…2nd Company. After that we moved over to the 4 th Battalion

- [suppressed weeping]. After that in the Negev Brigade. I was…in the

- beginning a squad commander, after that a platoon commander, and

- after that…an officer in the Brigade, and… That’s how I drifted

- through the army and I finished as a Lieutenant-Colonel. And…that

- was already within the territorial defense. And in the territorial

- defense I met her. [His wife: Not like that, you met me in a radio

- course. You were an instructor and I was a trainee.] Okay. And

- when I was released from the army I came to Gev. Since then I have

- been at Gev. In various roles. Community coordinator, treasurer,

- and…after that I went…to work in the movement. In the UKM. 7 I

- was…in the UKM for six years. Coordinator of the Health

- Committee. I was…and after that back to Gev, I worked for a few

- years in agriculture. After that, (they)assigned me -- (they) assigned,

- I took on the task of establishing a factory, and I established the

- factory called “Gevit.” A paper products factory. And I managed it

- up until I retired, actually. Half-retired. I had already wanted to be

- replaced. And it so happened that today the factory… When I

- established the factory it was…a bit of a problem in Gev. It was a big

- investment, and (they) weren’t used to that. And…in the beginning it

- limped along a bit. And then (they) actually began…to run after me.

- Why did you create this white elephant and why that… In the end

- that factory today, is the only thing that supports Gev. A lot for

- production, a lot… That’s it, until…I got a zbeng.8 A stroke. Since

- then I’m bound to the chair and… The lucky thing is that…as

- opposed to others, and I say as opposed, because I came out with an

- intact mind. It bothers me quite a bit these days. Meaning…the shift

- between disability and activity, it creates a problem for me,

- sometimes I…I think that I [suppressed weeping] am healthy today,

- in (my) thinking. (I) read books, read the newspaper, read…

- television. So when I think that I’m healthy, and I try…to do

- accordingly, physically – doesn’t work. For instance getting out of

- bed, beforehand I got up by myself. Now I don’t get up by myself. In

- walking I’m completely limited. And…and…these days I go back

- and forth between thinking that I’m healthy and the future, that I’m

- limited. And that’s it, it’s already…15 years. Essentially sitting in the

- chair. And that’s a long time. Very long. And along with that I

- have…a Filipino aide. He really does help me a lot. And this is how I

- go through my life. I don’t have much more than that now. I

- was…when I was active, I was a member of the political party

- center, the council. I was…pretty active in the UKM, I was in a

- position, I was a working man – in agriculture, I was in the

- community, community coordinator, I was treasurer. That’s my life.

- Always in public affairs. Until I got sick. I got sick, so it took me out

- of the…frame. I stopped going to the (kibbutz communal) dining

- room – now there isn’t a dining room anymore. (I) don’t listen to the

- (kibbutz assembly) meetings, no activity. I was limited, mostly the

- walking limited me. And…that’s that. About myself. What else do

- you want to hear? Interesting?

36 * Transcription and notes: Spector-Mersel (2014a).