Articles

“I was… Until… Since then…”:

Exploring the Mechanisms of Selection in a Tragic Narrative

This paper presents a reading of Amos’s life story that follows an interpretive model based on mechanisms of narrative selection (Spector-Mersel, 2011). Drawing on the notion of the narrative paradigm, this model is derived from narrative epistemology, and specifically from a conceptualization of how identities are claimed through stories. The narrative production is conceived of as consisting of six mechanisms of selection, through which biographical facts are sorted, with the purpose of confirming an end point. Accordingly, the analysis seeks to identify the expressions of these mechanisms in the story, as a means to recognize the identity being claimed. The examination of the mechanisms of selection displayed in both the content and the form of Amos’s story reveals a split end point, which divides Amos’s life into “before” and “after” the stroke. The “I was” part strictly corresponds with the cultural ideal of a Sabra-Kibbutz member, depicting Amos’s prior self as a “culturally appropriate” and highly significant figure in his collective. In contrast, the “since then” part, which portrays the past 15 years since the stroke as an extended present, conveys his being “outside” of both the culture and the collective. Considering Amos’s story a clear instance of a tragic narrative, some insights are offered that can shed light on possible manifestations of this story genre.

1 In this paper I offer a reading of Amos’s life story (see Appendix) that follows an interpretive model based on mechanisms of narrative selection (Spector-Mersel, 2011). My primary goal is to demonstrate a possible implementation of this model. Yet in so doing,I also illustrate its potential utility as a mode to display the analysis 1 conducted. Hence, while explicitly focusing on the process of interpretation, I also attempt to exemplify its possible outcome, offering the mechanisms of selection as, hopefully, a valuable vehicle in both making sense of narrative data and composing the interpretive account.

2 Drawing on the notion of the narrative paradigm (Spector- Mersel, 2010a), the model proposed is deeply rooted in narrative ontology and epistemology. Accordingly, before detailing its precise rationale and analytical procedures, I will lay out the philosophical groundwork from which they derive, principally the notions of holism and the claiming of a point via narrative. This foundation, in my view, is not limited to the model specified, but is rather significant for all kinds of narrative analyses. By relating to the premises on which the model stands, I thus actually deal with the groundwork of narrative analysis in general.

3 Having discussed the theoretical groundwork, I proceed to the specificities of the analysis. Here too, a tight connection exists between epistemology and methodology, particularly between the understanding of the process through which narratives are generated, and the way they are interpreted. Conceptualizing the narration process as composed of six mechanisms of selection generating a point, or an “end point,” I suggest employing these very mechanisms in the analysis. Thus, the researcher traces the “footprints” of the mechanisms originally employed by the teller, while attempting to explore the claimed end point.

4 In the second part of the paper, I apply the suggested model to interpret Amos’s story. The examination of the mechanisms of selection displayed in this text unfolds a split end point, which divides Amos’s life into “before” and “after” his stroke. Considering this story as an instance of a tragic narrative, I offer some insights that can shed light on possible manifestations of this story genre.

Narrative Paradigm and Narrative Analysis

5 Unlike methods of narrative analysis that exclusively focus on the how to of interpretation, seemingly detached from a theoretical foundation, the present model explicitly rests on theoretical premises. Its analytical tools emerge from an understanding of what narratives 2 are and how they are produced, attempting to “operationalize” this understanding by turning it into practice. This connection between theory and analysis is informed by the conception of the narrative paradigm(Spector-Mersel, 2010a), which posits a full-fledged research worldview that connects premises about human reality and the means through which it may be studied. Employing the accepted concepts, a close correspondence is implied between ontology, epistemology and methodology.

6 The present analysis springs from the Weltanschauung of the narrative paradigm, on two levels. On the general level, it conforms to fundamental principles in narrative philosophy. On the more specific level, it grows out of a theoretical conceptualization of the process through which narratives are generated. I shall start by elucidating the former.

7 Among the complexity and richness that comprise narrative ontology and epistemology (for details, see Spector-Mersel, 2010a), two premises seem to me particularly important regarding narrative analysis. The claiming of a point via stories determines its purpose,whereas holism informs the meanstowards this purpose. Let us illuminate each.

The Purpose: Recognizing and Explaining the End Point

8 The constructivist epistemology underlying the narrative paradigm, as crystallized since the narrative turn, strongly rejects the “factist” perspective that ruled the first biographical studies (Alasuutari, 1997). While the latter conceived of stories as pictures of phenomena outside them—either inner to the narrator (e.g., personality, identity) or outer (e.g., social structure, culture)—current theorization accentuates that narratives are not transparent windows to something “out there” (or “in there”). Rather, they constitute selective and subjective accounts of phenomena. As I have suggested elsewhere (Spector-Mersel, 2010a), this epistemology determines the first principle of narrative methodology: treating the story as an object for examination. Since stories are data, not a channel to the data, they cannot be regarded as transparent containers of phenomena lying “beyond” them.

9 Considering narratives as vehicles for meaning-making (Polkinghorne, 1988), it has been argued that they “make a point” (Alasuutari, 1997; Polanyi, 1979; Riessman, 2008; Smith & Sparkes, 2009). I adopt Gergen and Gergen’s (1988) term end point (hereafter, EP), to refer to the story’s main or principal message (and not to an ending or denouement in temporal terms or in terms of the narrative’s dramatic structure). All narratives make an EP of some kind, yet in self-narratives it takes on a particular significance. Narratives aboutan external object, whose focus lies outside the teller, e.g., a story about my country (Spector-Mersel, 2011), certainly reveal something about him or her. In a self-narrative, however, that constitutes “the individual’s account of the relationship among self-relevant events across time” (Gergen & Gergen, 1988, p. 19), the direct object is the teller, often his or her life history: the lived-through life (Rosenthal, 1993). Either when this life history is related only in part, eliciting a defined self-narrative (Spector-Mersel, 2011), and more markedly, when it is recounted as a whole, creating a life story, an EP is straightforwardly being claimed as to who the teller is. Or better, as to how he or she presents themselves in the specific story. In this spirit, Mishler (1986) considers (self) narrative as “a form of self- presentation, that is, a particular personal-social identity is being claimed” (p. 243). In self-narratives, then, the EP actually constitutes a claimed identity that portrays a specific version of the teller. As implied by Mishler’s (1986) term “personal-social identity,” self- narrative’s EPs are often culturally valued (Gergen & Gergen, 1988; Polanyi, 1979), that is, reveal a special “culture sensitivity.”

10 Along these lines, the general purpose of the analysis of narratives may be identifying their EP. When self-narratives are explored, as in Amos’s text, this endeavor entails recognizing the identity claimed in the story. But the analysis does not conclude here. A complementary task is offering some kind of explanation of the EP identified—that is, developing an interpretive framework that points to possible factors (psychological, social, cultural, and contextual) that may account for the EP (Spector-Mersel, 2011). Considering the two levels of interpretation mentioned in the introduction (Spector-Mersel, 2014)—the what and the why—I suggest that narrative analysis endeavors to respond to two basic questions: what is the EP claimed in the story, and why precisely this EP?

The Means: A Holistic Interpretive Strategy

11 The means towards this purpose, I believe, is informed by the concept of holism, a major emphasis in narrative ontology. Narratives are conceived of as multi-origin and multi-layered products, in which various dimensions converge (Spector-Mersel, 2011). Considered a principal theoretical premise, holism has been emphasized as the hallmark of narrative analysis (Chase, 2005; Daiute & Lightfoot, 2003; Josselson & Lieblich, 2001; Mishler, 1986; Riessman, 2008). But what precisely does this mean in practice? Attempting at a possible answer, I suggested the holistic interpretive strategy as the second principle of narrative methodology, and a general framework for narrative analysis (Spector-Mersel, 2010a, 2011). This strategy entails five practical aspects. The first two relate to the what level of the analysis—recognizing the story’s EP—while the subsequent three concern mainly the more advanced phases, when trying to figure out why this EP.

12 1. Treating the story as a whole unit, often termed holistic analysis (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, 1998), is indicated as the signature of narrative understanding (Bruner, 1991; Josselson, 2011; Polkinghorne, 1988; Rosenthal, 1993), and the fundamental distinction between narrative analysis and other forms of qualitative analysis (Riessman, 2008). The opposite strategy—categorical analysis—that isolates segments in the story (Lieblich et al., 1998), may be considered a strategy of de-narrativization. It might, though, serve as a complementary technique in narrative interpretation, subordinate to the principal holistic analysis.

13 2. Regard for content and form concerns attending to what is said (and what is not said) and how it is said, that is, the linguistic and structural aspects of the narrative. Although the content is our “natural” focus of attention while listening to a story, the form equally matters (Bruner, 1987). The content and the “storying style” (Kenyon & Randall, 1997) are two complementary “voices” through which the story “speaks”—two channels through which its EP is being claimed—thus both need to be explored.

14 3. Attention to contexts of production is required, since “stories don’t fall from the sky … they are composed and received in contexts” (Riessman, 2008, p. 105). Exploring the contexts within which the story has been told is thus essential, even constituting a criterion of “good enough” narrative inquiry (Riessman & Speedy, 2007). Specifically, in attempting to figure out why this EP, we should explore the “narrative environments” within which the “narrative work” has taken place (Gubrium & Holstein, 2009; see also Randall & McKim, 2004). These include three contextual circles: macro, micro, and immediate (Spector-Mersel, 2011). When self-narratives are analyzed, considering the EP as contextually bound has to do with the notion of multiple narrative identities (Bamberg, De Fina, & Schiffrin, 2007; Mishler, 2004). In line with this epistemology, Amos’s story’s EP needs to be seen as representing a given selective identity, claimed in a specific web of contexts (see Tuval-Mashiach, 2014).

15 4. The analysis of both life and story stems from the ontological premise, that life and narrative imitate each other and neither can fully exist without the other (Bruner, 1987; Polkinghorne, 1988; Spence, 1982; Widdershoven, 1993). A major aspect of this multifaceted relationship is that every narrative represents a particular point throughout the permanent flow of life. Because the present is the only “real” time in the narrative, as the past and the future are regarded from its vantage point (Freeman, 1993), the EP merely reflects the narrator’s conception at the time of the telling. This is evident in Amos’s story, which is being told from his present situation, as a handicapped old man.

16 5. Employing a multidimensional and interdisciplinary lens draws from the ontological conception of narratives as multi-origin and multi-layered products. This is not to reduce disciplinary and theoretical inclinations that naturally direct every researcher, but to emphasize the necessity of expanding our vision when analyzing narratives. In developing an interpretive framework for the story’s EP, we may thus consider a range of dimensions (i.e., body, identity, cognition, emotion, gender), and relate, to some extent, to psychological, cultural, and social influences. This holistic imperative, which can never be completely realized, is, I believe, one of the complex challenges inherent in narrative analysis.

Mechanisms of Narrative Selection

17 Thus far, I have addressed the general correspondence between narrative philosophy and analysis: the notion of claiming a point implies the latter’s purpose—recognizing and explaining the story’s EP—and the premise of holism informs the holistic interpretive strategy as a means towards it. The present model is marked, however, by a more specific linkage between the “what is” (a narrative) and the “how to” (interpret it). Particularly, the analysis of the narrative derives from a theoretical understanding of the narration. The conceptualization of the course through which the teller molds a story dictates the manner in which the latter is approached by the researcher.

18 How, then, do we tell a story? What does this process look like? Following others (Gergen & Gergen, 1988; Randall, 1999; Rosenthal, 1993; Sarbin, 1986), I consider selection as the organizing principle of the narration. Each and every act of narration involves choices and decisions—often unconscious—as regards to what to tell (and what not to tell) and how—that is, how the facts being selected are organized and what meaning is attributed to them. Actually, it is through this selection that narrative meaning-making processes (Polkinghorne, 1988) take place. Selectiveness is evident in all types of narratives, but is intriguingly apparent in self-narratives. Our life history—the collection of events and facts that constitute our lived life —comprises an immense repository of events, places, dates, and people. When we aim to weave a particular account out of this information, it is as if we “look” at the list of our biographical “building-blocks,” ultimately picking up only a few. The claiming of identities through stories is thus based upon conscious and unconscious 3 acts of sorting, filtering, and selecting from the “raw material” contained in our life history. But what directs this selection? Upon what principle are life facts sorted and edited? Drawing on Gergen and Gergen (1988), 4 it is the first component of the narrative (creation): the establishment of an EP. The EP set to the story yet to be told, guides the subsequent selection.

19 Specifically, I suggest thinking of this process as consisting of six mechanisms of selection that aim at asserting an EP (Spector- Mersel, 2011). The most basic mechanism is inclusion, which refers to representing facts, events and periods from the teller’s life history that are compatible with the story’s EP, thereby confirming it. Some of these facts are given prominence through the mechanism of sharpening: the emphasizing of life facts that are compatible with the EP. While inclusion and sharpening refer to what is reported, the two following mechanisms refer to what is not. Omission is the non- reporting of life facts irrelevant to the EP, whereas silencing relates to the non-reporting of life facts that contradict it. Flattening5 refers to the condensation of life facts; these are reported but markedly reduced. This is so, because either they are irrelevant to, or contradict the EP—here, flattening resembles omission or silencing, differing from them in intensity: instead of telling nothing, telling only a little bit. Or, life facts can be flattened for they relate to two opposing parts of the EP. In this case, flattening fulfills a dual function, as both mentioning a fact and asserting its insignificance are compatible with the EP. Hence, if my story’s EP is: “I am a good researcher, but I am mainly a devoted mother,” I might say: “I spend many hours in my office, but this is not really important to me.” The last mechanism— “appropriate” meaning attribution—refers to conferring life facts with significance compatible with the EP. This mechanism springs from the narrative’s ability to ascribe meanings to life facts, events, or periods that in “real time” might have held different meanings, pointing to the delay, or “postponement,” of insight that characterize human existence (Freeman, 2010). By way of illustration, diverse meanings may be conferred on a past marital relationship that ended in divorce, compatible with different EPs, narrated at different points in the teller’s life, or in front of different audiences. If the story’s EP is: "We should have stayed together and work out the difficulties," then the former relationship might be recounted as essentially positive. If, in contrast, the EP is: "Since I got divorced I have gained my life back," the same relationship would be described in quite dark colors.

20 In detailing the mechanisms of selection I referred to the processthrough which the teller—often our research participant—forms a narrative. Now I wish to return to the researcher, who strives to interpret the already-narrated text. My intention here is turning the conceptualization of the narration process displayed into a possible mode of reading the narrative. Fundamentally, I suggest tracking the narration process in reverse: beginning with its final product—the text, and going backwards towards its initial step: the EP. Assuming that biographical selection is not haphazard (Rosenthal, 1993), and that everything said (and not-said) in a given story functions to express, confirm, and validate the identity claimed in it (Mishler, 1986), then identifying the manifestations of the mechanisms—both in content and form—in the story, unfolds its EP. The researcher thus follows the narrator’s footsteps, but backwards. Borrowing familiar terms, the (narrator’s) process of claiming a narrative identity is deductive—first the EP is set, then biographical facts are selected to confirm it—whereas the (researcher’s) interpretation is inductive, for the EP unfolds out of the identified manifestations of selection. It is important to note, though, that while the EP initially set to the story typically directs the subsequent selection, the point of the story may alter throughout the process of narration (Polanyi, 1979). In part, this has to do with the extent of the conscious and unconscious forces guiding the narrative selection (see n. 4). In any case, the analysis unfolds the EP actually claimed in the story, whereas the “original” EP remains inaccessible to the researcher, and therefore is theoretical in nature.

21 Summing up, the present analysis aims at identifying the expressions (both in content and form) of the six mechanisms of selection in a narrative text, as a means to recognizing its EP. 6 Analytically speaking, our guiding question would be: what is the selection manifested in the story, and what EP does it present? When a self-narrative is analyzed, our practical question would be: what life history material is represented in the story, and how? Thus, while the “why” level of interpretation is certainly inherent in the analysis (why precisely this selection? why this EP?), the six mechanisms specifically operate in the “what” level. Accordingly, this will constitute my focus in interpreting Amos’s story.

Amos’s Story: Tracing the Selection

22 In what follows, I offer a reading of Amos’s story, based on the model presented. Specifically, I will point to the mechanisms of selection that appear in the text, showing how they operate and cooperate in claiming Amos’s identity EP. As detailed elsewhere (Spector-Mersel, 2011), identifying the narrative selection requires, as a first step, unfolding the alternatives available to the teller. As every point in the story represents a choice between alternatives (Rosenthal, 1993), for these choices to be recognized, we need to examine the story against its “building blocks,” i.e., the teller’s life history. This involves extracting information from all ethically accepted sources available, primarily the interview’s questioning period (Rosenthal, 1993). Relying on this section, and obviously on the life story too, I drew Amos’s life line: an abstract of his life history. In studying this biographical information, I asked myself what options are available to narrate it. What possible meanings may be conferred upon individual events in Amos’s life, such as the stroke? What potential configurations can be thought of, that organize his various life events and periods into a Gestalt?

23 I subsequently prepared the story line: a summary of the life story. 7 Comparing between these abstracts, I pondered on the relationships between Amos’s life and story: what facts and periods from the life line appear in the story line? Conversely, what life line information is absent from the story line, creating “holes” in the latter? While already beginning the analysis, at this phase I still focused on eliciting questions to be subsequently explored. With these in mind, I began the main analytic phase: exploring the mechanisms of selection in the text. As the analysis proceeded, the EP gradually unfolded, increasingly crystallizing, until attaining its final form. For a clear demonstration, I will state the EP of Amos’s story in advance:

This EP clearly divides Amos’s life into two separate, even opposed, parts: before the zbeng (his term for the stroke he suffered 15 years prior to the interview), and after the zbeng. Interestingly, this division is apparent in the general structure of the story. Looking at the text from a bird’s-eye view, we notice that it comprises three identifiable parts. In the first part (1-35), Amos recounts what “I was”: a Sabra, a contributing kibbutz member, always in public affairs and competent. All this, he indicates, “Until … I got a zbeng” (35). In the second part (35-50), Amos describes his life since then: “Since then I’m bound to the chair […] 9 the shift between disability and activity, it creates a problem for me” (35-36). The third and last part of the story (50-59) constitutes a concluding argumentation that unites the two previous parts: “I was active […] always in public affairs. Until I got sick […] It took me out of the frame” (51-56). As implied by the concluding argumentation, the story’s overall EP consists of the “pasting together” of two seemingly separate EPs: I was (before-the-zbeng EP), and since then (after-the-zbeng EP). This split requires a separate examination of each EP, subsequently attempting to explore how they relate to each other.

The “I was” EP

24 Scrutinizing the selection evident in the first part of the story unfolds a marked “I was” EP, composed of four interrelated emphases that introduce the before-the-zbeng Amos: I was a Sabra, a contributing kibbutz member, always in public affairs and competent. In fact, the first attribute embraces all the others: the “real” Sabra dedicates his life to the collective (i.e., the public), clearly materialized in being a contributing kibbutz member, and he is capable and competent. I nevertheless detailed each of these features in the EP, since they are respectively emphasized in the story. As described in the Guest Editor’s Introduction (Spector-Mersel, 2014), the “exemplary” Sabra life consists of a clear life-track, with definite features and “stations.” I had recognized these prior to analyzing Amos’s story, from an extensive reading of literature on and by Sabras, and particularly from my previous study on the narrative identities of former Sabra high-ranked officers in old age (Spector- Mersel, 2008), a group that clearly embodies the mythological Sabra. I mention this to highlight the importance of the researcher’s possessing a quite extended knowledge regarding the narrator’s culture, as a prerequisite to "see" cultural codes hidden in the narrative. Reading Amos’s story with this knowledge in mind, I soon realized that its first part strictly follows the Sabra cultural script. Just as in the officers’ stories, the selection principle guiding this part was: life history facts that conform with the Sabra key-plot, or master narrative (Nelson, 2001)—the ideal life course of the mythological Sabra—are “worth” telling (i.e., included and sharpened). In turn, facts detached from this cultural story are left on the “shelves” of the life history’s repository (i.e., omitted or silenced, or at least flattened), or alternatively have “proper” meaning attributed to them. Consequently, I suggest Sabra as an elementary claim of the EP, although Amos does not employ this term in the story. Let us examine how the Sabra frame of relevance is evident in the text.

25 Inclusion is useful to begin with, as it is the most basic mechanism. Here we ask: what biographical material is represented in the story? Amos begins his life story with a common opening statement: “I was born in Poland.” But he immediately goes on to: “I came at the age of 2” (1), possibly implying that he is (almost) Israeli born—a fundamental feature of the ideal Sabra. Moreover, the first event mentioned in the story, after his very birth, is his immigration to Israel—the ultimate Zionist act. The next fact Amos includes is: “because my mother’s family mainly, were in Balfur, so we came to Balfur” (2-3). Being a well-known Zionist community, Balfur was a “proper” living place for a Sabra, as is the next place in Amos’s biography that he goes on to mention: “After that we moved to Tel Aviv” (3-4). Being “the first Hebrew city” and the major residence of the Zionist establishment at the time, Tel Aviv is central in the Sabra ethos. Having stated the “right” places in which he grew up, Amos continues mentioning the schools at which he studied, both known Sabra institutions (4-6). The next reported fact—“I was a member of the Machanot Olim. For a long time” (6-7)—completes his portrait as a Sabra adolescent, since participating in a youth movement was a major characteristic of the prototypical Sabra life.

26 Having displayed a typical Sabra childhood and adolescence, Amos goes on to note: “I was sent to the Palmach” (8). This fact conforms with the cultural script that depicts the Palmach as the desirable result of Sabra socialization. Accordingly, Amos portrays his first adult-life act—enlisting in a military framework—as a clear continuation of his pre-adult life. After mentioning his youth movement, he notes that “within this framework I was sent to the Palmach”(7-8). And in explaining how precisely this occurred, he recounts that he was in a Hachshara—another Sabra cornerstone.

27 By including the circumstances of his enlisting, two further claims are implied. First, the competent EP, introduced here to the story. “All Hachshara provided a quota for the Palmach” (9), explains Amos, implying that he was chosen for this mission, probably due to being better qualified than others. This fact further highlights his competency, which was already proven by his having been accepted to the prestigious framework. Second, the Sabra EP is promoted. “It was still before (they) had recruited all the Hachsharas” (9-10), Amos notes, implying that he was enlisted at a very early stage. This is further explicit by the next fact included: “I was in the Palmach, from the year…’42” (10-11). The Palmach was founded in 1941, thus Amos is one of its senior soldiers, which points to his “excellence” in being a Sabra.

28 In accordance with the practical and reality-oriented Sabra discourse, Amos continues providing details about his company, battalion and brigade (12-13), and then refers to his military advancement: “I was … in the beginning a squad commander, after that a platoon commander, and after that … an officer in the Brigade […] I finished as a Lieutenant-Colonel” (13-16). Not only the Sabra EP is being claimed, for military service is the major realization of Sabra-ness, but the competent EP too, as Amos’s quick advancement certainly points to his qualities. The narrated military period ends by mentioning his meeting his wife, a seemingly temporary deviation from the main storyline, which I later address.

29 Amos goes on to the next chapter in his biography: “when I was released from the army I came to Gev” (20). Living in a kibbutz is a major fulfillment of the Sabra ideal, thus the Sabra EP continues to be reinforced. Yet the more specific EPs are added: a contributing kibbutz member, always in public affairs and competent. “Since then I have been at Gev” (20-21), Amos notes, implying that, unlike many others that left the kibbutz, he remained a loyal member. He was not, however, just another member, but a central figure in his kibbutz, and afterwards in the UKM. This is indicated by detailing the “various roles” (21-24) he fulfilled, which stress his being a public figure, his contribution to the collective, and certainly his competency, as he was chosen, out of many, to perform these central roles. All these EPs are most powerfully claimed through the subsequent mini-narrative that ends the story’s first part, which I discuss below.

30 To conclude the mechanism of inclusion, we notice that each and every life fact represented in the first part of the story correlates with the Sabra key-plot, thus building Amos’s (past) image as a “real” Sabra. As in the cultural script, in his narrated life Amos is (almost) Israeli born, he grew up in Sabra places, studied in Sabra schools, participated in a youth movement and in a Hachshara. As an adult, he implemented his Sabra mission by enlisting in the Palmach, fighting within it for a long period, and subsequently in the IDF. Once concluding his military contribution, Amos continued to fulfill his Sabra-ness by significantly contributing to his kibbutz and the UKM.

31 Once having attained a general picture of this part of the story, relying on the mechanism of inclusion, we may continue to a subtler mechanism of selection: sharpening. To explore this mechanism we ask: What life facts are emphasized in the story? Sharpening via content is exemplified when Amos mentions: “I studied at the Beit Chinuch, the A. D. Gordon Beit Chinuch” (4-5). Beit Chinuch is the well-known shortened name of his Sabra school, thus it would have been certainly sufficient here. Nevertheless, Amos provides its full name, highlighting his Sabra ascription. Content sharpening is manifested also with regard to the high school. Although mentioning the “Chadash High School,” Amos stresses “continuation. And … secondary school” (6). This may have to do with the fact that at that time secondary education was not inevitable, since many youngsters left school to work. However, the “real” Sabras typically continued their studies. In fact, their high schools constituted central socialization agents, within which the generation’s leaders were formed. Against this background, the fact that Amos did continue to secondary studies is worth emphasizing.

32 Sharpening via form is demonstrated in Amos repeating twice each of the Sabra places in which he grew up: “because my mother’s family mainly, were in Balfur, so we came to Balfur […] we moved to Tel Aviv. In Tel Aviv I was…” (3-4). A further mode of formal sharpening is employing a mini-narrative: a small story within the larger story (see Rosenthal, 1993). The “zooming in” on a particular event is never coincidental. Furthermore, the pseudo-objective feel of this type of text—supposedly, it recounts what “really” happened— grants a “confirming power” to the EP. Amos’s life story includes a single mini-narrative, abbreviated below:

All the aspects of the “I was” EP are claimed through this episode. As the factory manager, Amos performed a central role in his community (always in public affairs); running the kibbutz’s main provider, he made it a significant contribution (contributing kibbutz member); and the factory’s success certainly points to his own capability, highlighted by the lack of support from “others” (competent).

33 As all these traits are compatible with the Sabra ideal, they contribute in turn to the Sabra EP. As it clearly reinforces the story’s EP, this episode is sharpened; not only by the text’s type of mini- narrative but also by the significant volume it is conferred—about a third of this part’s total volume. Yet this sharpening may be accounted for by an additional reason, interestingly implied by a further dual sharpening within the mini-narrative: Amos repeats that “today the factory” (29); “that factory today, is the only thing that supports Gev”(34), and he stresses “today” through a higher pitch. By these instances of sharpening, his (past) contribution in the factory is claimed to be relevant at present, possibly representing a vehicle of symbolic immortality (Lifton, 1977), in face of his gloomy present.

34 Omission is the opposite of the previous two mechanisms. In examining it, we ask: what life facts are non-reported, as they are irrelevant to the EP? We may think of various life facts that might be expected to be mentioned in a life story, but nevertheless did not enter Amos’s account, probably for being unrelated to its EP. For instance, what kind of child was he? does he have any siblings? children? We should keep in mind that omitting themes, people, or periods from a self-narrative by no means indicates that they are unimportant to the teller. The omission of Amos’s children in this specific life story points only to their irrelevance to this story’s EP, and we can in no way infer that they lack importance to him.

35 Closely related to omission is silencing. This mechanism also refers to life facts not reported, but postulates a different reason: they contradict the EP. 10 Silencing is evident in the opening sentences of Amos’s story: “I was born in Poland. I came at the age of 2” (1). I referred earlier to the textual proximity between being born in Poland and the act of coming to Israel—the two first facts included. Now I wish to claim that the lack of any reference to the time in-between, namely to Amos’s first two years in Poland, may signify silencing. Poland constitutes the Diaspora, the ultimate “other” of the iconic Sabra (Spector-Mersel, 2008, 2010b), thus accordingly silenced in Amos’s claimed identity.

36 One can possibly argue that Amos’s non-reporting of his two first years is the mere product of his inability to remember this period. It is worth noticing, then, that just as he surely does not remember his early life in Poland, neither does he probably recall his immigration, at the age of two. Still, in his story the first is silenced, whereas the latter is included. My interpretation of this absence as silencing might be further clarified by two pieces of empirical evidence. First, Sabra officers who arrived in Israel older than Amos, even at the age of 15, also typically silenced their Diaspora years in their narratives (Spector-Mersel, 2008). Second, in other studies that I have conducted, some participants did recount events from very early in their lives, which were definitely inaccessible to their memory—for they supported their story's EP. This evidence indicates that narrative memory by no means mirrors cognitive memory. Whether an event is, or is not, represented in a story, depends principally on its relationship to the EP. According to this principle, not only Amos’s life in the Diaspora is silenced, but also the characters of his parents that represent it, with a minor exception referred to later. 11

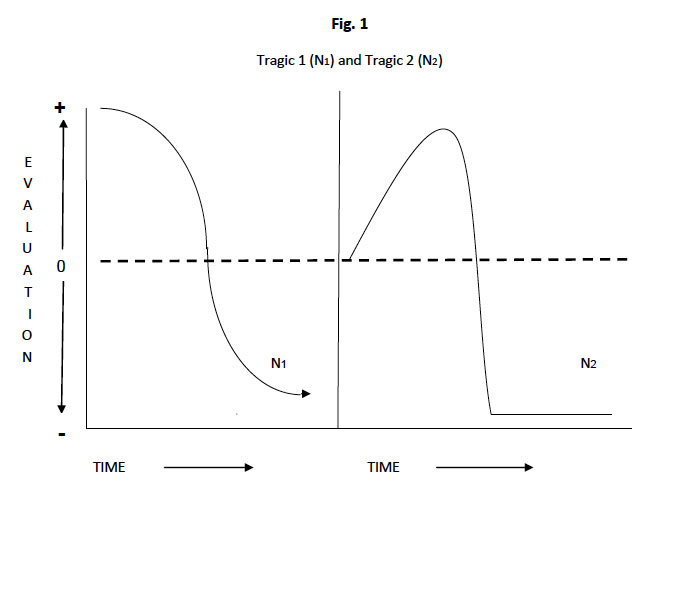

37 In examining the mechanism of flattening, we ask: what life facts are condensed—that is, mentioned, but only in passing? Let us examine a particular example of this mechanism. When relating to the factory he established, Amos mentions that “in the beginning it limped along a bit” (31-32). But he does not elaborate any further and does not detail what precisely “limped along.” Rather, he continues on by noting that “(they) actually began … to run after me” (32), and emphasizes that “In the end that factory today, is the only thing that supports Gev” (33-34). Amos thus offers a possible hint at a failure, but he immediately flattens it, both through content—by focusing on the others’ non-supportive attitude and the final successful outcome— and form—giving it very limited space; a short sentence. The flattening here resembles the mechanism of silencing, for the flattened theme—a possible failure—contradicts the competent EP. It is, however, flattening rather than silencing, since the failure is referred to, albeit briefly.

38 The final mechanism of selection is “appropriate” meaning attribution. Our analytical question here is: what significance is conferred to life facts? Attributing “proper” meaning through content is exemplified when Amos recounts that while arriving in Israel, “because my mother’s family mainly, were in Balfur, so we came toBalfur” (2-3). Amos’s only reference to his mother in the story associates her with Israel and the Zionist community, rather than with the Diaspora which she came from, pointing to the Sabra EP. To demonstrate “appropriate” meaning attribution by form, let us return to the opening sentence: “I was born in Poland. I came at the age of 2. I came…—(they) brought me” (1-2). Although Amos corrects “I came” to “(they) brought me,” his apparent “error” indicates that intuitively, he recounts his personal history according to the Sabra key-plot. Employing the first person pronoun and an active verb— although he was only two years old—conforms to the Zionist ethos that depicts immigration to Israel as a purposeful act. Another instance of attributing “proper” meaning via form—once again reinforcing the Sabra EP—is Amos’s phrasing of his enlisting to the Palmach. The passive verb “I was sent” (8), by no means points to external locus of control. Rather, it follows the common Sabra discourse that highlights the collective as determining individuals’ lives. Accordingly, Amos did not decide to enlist; rather, he implemented the collective’s decision. Interestingly, in the second self-correction later in the story, Amos resists this collective discourse of “(they) assigned me,” when he begins to recount his establishing the factory, but immediately changes passive to active: “I took on the task of establishing a factory, and I established the factory” (25-27), highlighting the competent EP. These instances of language being culture-bound suggest that familiarity with the narrator’s language—and this goes much beyond the linguistic knowledge of Hebrew, and refers to culture—can be vital in the analysis.

39 A last example of “appropriate” meaning attribution via form is Amos’s only reference to his wife: “And in the territorial defense I met her” (17-18). Including this fact in the midst of recounting his Sabra career appears to deviate from the main plot, resulting perhaps from his wife’s presence during the narration. This deviation, however, is strikingly depicted as temporary and insignificant. Not only is the image of Amos’s wife flattened into a short sentence, which is “locked-up” between two sentences recounting his Sabra career, but principally, she is not portrayed as a theme on her own, but rather as subordinate to the main Sabra plot. This is indicated by his referring to “her,” with no mention of her name; by Amos’s non- reacting to her correction of their meeting’s circumstances (“Okay,” he mutters [19] and continues with his account); and by her late introduction into the story. Although Amos met his wife during a Palmach course (that is, probably between 1944-47), he refers to the event only after having mentioned the conclusion of his military service (in 1952). The gap between the historical and narrative timing of the events may point to their different importance in the claimed identity.

40 Let us conclude the selection evident in the first part of the story. The “I was” EP, that represents Amos’s former life and self, is noticeably based upon the Sabra script. Facts from Amos’s life history that are compatible with this script are included in the story, some sharpened (“stations” in the Sabra socialization, military frameworks, contributions to the kibbutz); life facts irrelevant to this script are omitted (e.g., his children) or conferred the “right” significance (his wife); and life facts that contradict the key-plot are silenced (e.g., the Diaspora) or again, given “proper” meaning (his mother). Coinciding with the image of the Sabra, Amos’s former self is portrayed as competent (accordingly, failures are silenced or flattened), and as one who dedicated his life to the collective (indicated by including his public roles and sharpening his contribution while managing the factory). The Sabra key-plot accounts also for more holistic attributes that characterize this part of the story, and which unsurprisingly typified the officers’ stories too. A notable mark is adherence to the outer reality (evident in including years, places, roles, and military affiliations) while silencing the inner world (evident in the non- reporting of feelings and thoughts, and in suppressing his weeping). Furthermore, as indicated by the Sabra ethos, Amos’s acts for the collective are specified, while his personal and familial life is omitted, portrayed as irrelevant to the claimed identity.

The “since then” EP

41 Amos’s life as a fine Sabra-Kibbutz member ended abruptly, when he suffered a stroke. This is stressed when Amos states: “That’s it, until … I got a zbeng” (35). The expression “That’s it” indicates that his former life is concluded, and the term “zbeng,” sharpened by pitch tone, confers on the stroke its “right” meaning, namely its being a dramatic event that fully collapsed his former life. From now on, his (narrated) life and self are radically transformed. Two points are emphasized in Amos’s account of his life “since then”: I’m bound to the chair and I live in a contradiction between an intact mind and a disabled body.

42 The first point emerges right at the beginning of the second part, constituting Amos’s first reference (i.e., sharpening) to his life after the stroke: “Since then I’m bound to the chair” (35-36). Although severely limited, Amos is not literally “bound to the chair.” With his caregiver’s help, he manages to get up and even walk a few steps. More than mirroring his precise physical situation, then, this expression reveals an “appropriate” meaning attribution that conveys Amos’s body as a “total loss.” This is further suggested by Amos’s inclusion of what he physically cannot do (“I don’t get up by myself. In walking I’m completely limited,” 44-45)—while silencing (the few) activities that he can do, albeit with assistance.

43 In accordance with this EP is also the inclusion of the “Filipino aide” that “really does help me a lot” (49), thus emphasizing his physical dependence. This selection is further apparent in the omission of any other human image in this part of the story, for their inclusion might possibly have underscored other aspects of Amos’s self. For example, had he referred to his grandchildren, his grandfather’s role would have been indicated. Or had he mentioned his Palmach mates, with whom he meets now and then, his Sabra-ness would have been underscored, which is irrelevant in this part of the story. The bound to the chair EP is most powerfully conveyed in Amos’s conclusion of his life since the stroke: “And that’s it, it’s already … 15 years. Essentially sitting in the chair” (47-48). Amos could have selected other attributes to mark this period, such as his struggle to recover, his family support, or his well-maintained mental abilities. From the alternatives available, however, he selects his physical disability as characterizing his life since the stroke, exerting “appropriate” meaning attribution.

44 The second emphasis of the “since then” EP—I live ina contradiction between an intact mind and a disabled body—is claimed by direct references included in this part: “the shift between disability and activity, it creates a problem for me” (38-39); “when I think that I’m healthy, and I try … to do accordingly, physically—doesn’t work” (42-3); “I go back and forth between thinking that I’m healthy and the future, that I’m limited” (45-47). In light of the story’s shortness, these sentences represent sharpening (by volume) of this theme. The opposition between Amos’s “intact mind” (38) and disabled body is also possibly implied by his reference to the “Filipino aide” (49). The term “aide,” substituting the more accepted term “caregiver,” reduces Amos’s dependency, as “care” is more intensive than “aide.” Furthermore, in referring to the aide, Amos employs an active verb: “He really does help me a lot” (49), and not a passive phrasing, such as “I am helped by him a lot.” Instead of portraying himself as the recipient of assistance, the worker is depicted as its provider. These last two might represent “appropriate” meaning attribution (first by content, then by form), that lessens Amos’s dependency and passivity, possibly suggesting that his intact mind guards him against the total dependence implied by his limited body.

45 Further concerning the body-mind contradiction, notice that just as Amos’s physical disability is intensified in the story, the opposite seems to occur regarding his cognitive functioning. The term “intact” (38), selected to characterize his mind, is informative in this regard. Also, just as Amos includes the cannots and silences the cans when referring to his body, when relating to his mind he includes and sharpens the cans—“(I) read books, read the newspaper, read … television” (41-42)—and silences cognitive impairments. The latter are implied in the text itself, when Amos fails to remember the years of his Palmach service (11), and by his incorrect version, according to his wife, of their meeting (18-19). Just as his body is fully disabled in the story, so is his thinking entirely “healthy” (40-41). (The term “healthy” is repeated in 42.)

46 Also noteworthy are Amos’s “mixed feelings” towards his “intact mind.” On the one hand, he sharpens (via pitch tone) its being “the lucky thing” (36). On the other hand, he states: “I came out with an intact mind. It bothers me quite a bit these days” (37-38). While partially feeling fortunate that his mind has not been damaged, Amos is also pained by this very fact, due to which he is doomed to realize his physical loss and live in a disturbing contradiction between body and mind.

(Dis)Connecting the EPs: A Tragic Narrative

47 The connection, or better, the disconnection, between the two EPs claimed in Amos’s narrative, form its overall EP, marked by a sharp division between his “good” or “proper” life before the zbeng and his miserable life thereafter. On this premise, I wish to suggest that Amos’s story constitutes a lucid instance not only of a "broken narrative" (Hyden & Brockmeier, 2008), but specifically, of a “tragic narrative.” The definition of a tragedy has been extensively discussed, originally going back to Aristotle’s Poetics (1987). Fundamentally, explain Gergen and Gergen (1988), the tragedy tells “the story of the rapid downfall of one who had achieved high position. A progressive narrative is thus followed by a rapid regressive narrative” (pp. 25-26). The tragic narrative, they further stress, is marked by the acceleration of and alteration in the narrative slope. Amos’s story evidently portrays these features. It recounts a culturally-adapted version of “one who had achieved high position”—a Sabra-Kibbutz member, who significantly contributed to his collective by fulfilling central communal roles—and who subsequently experienced a “rapid downfall”, following a stroke. The progressive line that typifies his life before the stroke thus quickly and dramatically alters into a regressive line, representing his life thereafter. While generally complying with Gergen & Gergen’s (1988) description of the tragic narrative, the thorough examination of Amos’s story by the mechanisms of selection offers some insights that can shed light on possible manifestations of this narrative genre.

48 My primary insight concerns the general form of the tragic narrative. In drawing its line (N1 in Fig.1), Gergen and Gergen (1988) focus on the downfall inherent in it. Their figure disregards the earlier progressive line, mentioned in their discussion, and the potential subsequent line, following the downfall. Amos’s narrative suggests a more extended form that may typify some tragic identities. This storyline is composed of three identifiable parts (N2 in Fig.1). The regressive line that represents the downfall is added to a preceding progressive line, that embodies the before-the-downfall, and a following stable line, capturing the after-the-downfall. The regressive middle line is undoubtedly the hallmark of the tragedy, as it signifies the narrative’s sharp fall along the evaluative space (Gergen & Gergen, 1988)—from a high positive point to a low negative one. Nevertheless, as in Amos’s story, it can constitute a very short part of the overall narrative, actually condensed as the turning point in a two- part structure.

49 The before-the-downfall part in Amos’s story clearly furnishes a progressive line. Life in this part proceeds in a coherent sequence. Every step continues the previous one, yet escalates it, intensifying Amos’s contribution to the collective until reaching its peak while managing the factory. At this high point, the narrative slope is suddenly truncated when Amos suffers a stroke. This turning-point results in a rapid downfall which ruptures his former life and self, indicated by the decisive phrase: “That’s it, until … I got a zbeng” (35). The accelerated regression that marks the tragic narrative is thus evident. However, once the storyline already descended, the stage is set to a (negative) stability narrative (Gergen & Gergen, 1988). Indeed, the after-the-downfall part of Amos’s story is recounted as a non-changing time-unit. “Since then I’m bound to the chair” (35-36), Amos states, depicting his last 15 years as an extended (stable) present. As in here, his additional references to his life “since then” are also phrased in the present tense: “it creates a problem for me” (39); “I think that I […] am healthy today” (40); “I read” (40); “I try” (42). This “appropriate” meaning, attributed by form, is strengthened by the content. “I came out with an intact mind,” Amos says, referring to the immediate consequence of the stroke, but then continues, “It bothers me quite a bit these days” (37-38). He draws a direct line between the stroke and his very present, disregarding the 15 years in between. This depiction of the “after” life as a static present suggests that in some tragic narratives the drastic descending of the narrative slope is followed by a negative line of stability, implying that life will never change in either direction. Further regression is considered impossible, for the narrative line has already reached its bottom. But so is improvement. In this respect, the tragic narrative resembles the “chaos narrative,” whose “plot imagines life never getting better” (Frank, 1995, p. 97). Yet while chaos stories lack any coherent sequence or discernible causality (Frank, 1995), this is true only for the “after” part of the tragic narrative.

50 A second insight concerns the marked discontinuity between the “before” and “after” that may typify tragic narratives. In Amos’s story, this split is evident in the differences between its two parts, both as to content (i.e., external vs. internal world; collective vs. personal) and form (i.e., past vs. present tense). This division is highlighted by the representation of human characters. Apart from his mother, mentioned only in reference to her family (2), Amos’s story comprises only two characters. The first is his wife—the most significant person in Amos’s actual life and his major source of emotional and practical support. Importantly, having been Amos’s partner during more than 60 years, she constitutes the principal thread of continuity throughout his life. Still, she is mentioned only in the “before” part of the narrative, possibly highlighting its overall discontinuity, stressed by the silencing of other lifelong companions (his children, old friends from the kibbutz or the Palmach). Also informative is that the single character in the “since then” part is the foreign caregiver, who only knows Amos in his “after” life, as a disabled old man.

51 The discontinuity between the before and after of the downfall, emphasized in the first two parts of the narrative, is additionally stressed in its third part, which offers a concluding argumentation. Here, the two previous EPs are put together in a condensed form that conveys the essence of the tragic identity: “I was […] Until I got sick […], it took me out of the … frame” (51-56). The content of the opposition conveyed earlier is also stressed: Amos’s positive speech, when noting what he was and did—“I was active … I was in a position, I was a working man […] I was in the community” (51-4)— is followed by a negative speech, when relating to what he currently is not anddoes not: “I stopped going to the dining room […] (I) don’t listen to the meetings, no activity” (56-58). The only reference to what he is points to his deficiency: “I was limited” (58), echoing the EP: “I’m bound to the chair.”

52 A third remark specifically refers to the before-the-downfall part of the tragic narrative. Although progressive while recounting his once good advancing life, it is shadowed by the collapse to come. In content, this may be seen in what I term “wasted cultural resources.” While notably storying his “before” life according to the Sabra key- plot, typical markers of the latter are peculiarly absent from the account. For instance, the 1948 War of Independence—the signature of the generational identity and typically sharpened by Sabras’ self- accounts—is not explicitly mentioned. Similarly, Amos omits his deeds during three years of service in the IDF at a critical historical time, which could undoubtedly reinforce his Sabra EP. Related is his depiction of the collectives (the schools, the youth movement, the Palmach, the kibbutz) as amorphous and impersonal, evident in the lack of any image identified with them. This attribute, contrasting the sharpened “we-ness” in the Sabra officers’ stories (Spector-Mersel, 2008), might be the result of “dripping” from his lonely present. This may be linked to the scarcity of mini-narratives in the story. In contrast to the extensive employment of this text type in the officers’ accounts, especially when recounting their military activity, Amos employs it only once, regarding a later life period. Because mini- narrative is the text closest to “reality” (Rosenthal, 1993), its shortage in Amos’s story may suggest that his Sabra past is felt as distant, almost unreal, as if slipping away from his memory and self— possibly a hint at the future downfall. The shadow of the future collapse is possibly apparent also in Amos’s suppressed weeping when recounting his Palmach affiliations—a supposedly good part of his life. Regarded together with the later instance of suppressed weeping (40), while relating to his disabled body, both instances refer to what Amos once had and is forever gone: belonging to exclusive collectives and an able body. Lastly, the emphasized past tense in which the “before” life is recounted may also inform that its progressive line is destined to end. Particularly instructive is the phrase “I was,” which is repeated no less than 16 times in relation to this part of life, a formal sharpening suggesting that all these facts are no longer relevant.

53 As we approach the conclusion of this article, let me summarize the essence of Amos’s tragic narrative as follows: I was… Until… Since then…. This is a story of a fine life, proceeding “by the book,” until an unexpected event occurred. As a result, not only has life altered, but it has significantly ended, as symbolized by the negative stability line signifying life henceforth. “I don’t have much more than that now” (50), Amos concludes, implying that nothing valuable has been left in his life.

54 It should be emphasized that this kind of significance conferred on the stroke and its consequences is by no means “natural” or “logical.” While undoubtedly a major challenge, losing physical abilities is not universally equated with the end of life. Why, then, does Amos select this meaning out of the alternatives available? Why does he claim this EP when invited to narrate his life history? Our concluding analytic endeavor should offer an “interpretive framework” (Spector-Mersel, 2011) for Amos’s narrative selection. However, a comprehensive explanation would be impossible, due to space limits. Thus, in addition to some influences suggested throughout the analysis, such as the search for symbolic immortality (psychology), or the presence of his wife during the narration (context), in this final note I would like to highlight culture as a major determinant of Amos’s EP, and possibly of tragic narratives at large.

55 Amos’s conceiving of his physical damage as a total collapse, that necessarily divides his life into before and after, is rooted in the Sabra-Kibbutz culture, which is markedly masculine (Spector-Mersel, 2008, 2010b). Three attributes of this culture make it extremely complicated to maintain a coherent self in the face of a disabled body. First, activity is a major value. This is evident when Amos refers to “the shift between disability and activity” (38-39); activity being considered the opposition of disability is thus equated with being healthy. Similarly, in the concluding argumentation, Amos represents the opposition between his life before and after the stroke in terms of activity or lack thereof: before, “I was active” (51, 52); after, “no activity” (58). The Sabra practical ethos is not, however, based upon personal activities, such as reading books or watching television, which Amos does. Rather, it demands activity for the sake of the collective, as clearly manifested in the “before” part of the story. And this kind of activity, according to the ethos, demands an able body. This brings us to the second point: the ideal of the Sabra-Kibbutz member-man is founded upon an able, strong (and young), body. Accordingly, with a disabled body, Amos cannot longer be a proper Sabra-Kibbutz member, or even a man. Lastly, Amos’s disabled body turns him into an old man – the ultimate “other” of both the Sabra- Kibbutz and the ideal man (Spector-Mersel, 2006). All these suggest, that Amos’s culture denies him the opportunity to continue being himself, namely a Sabra man. And indeed, he is not anymore—at least in his claimed identity. While recounting his pre-zbeng self as a meticulous materialization of this ideal, in narrating his post-zbeng self, Amos divorces himself from this ideal. While formerly a real Sabra serving his collective, now he is “bothered” (38) by his personal situation, just like a stereotypical old man. While formerly focusing on the outer reality, as Sabra men do, now he discloses his feelings and thoughts, as is typical of old people and women.

56 This movement from being “inside” the culture to being “outside” it is nested in a parallel implied movement, concerning the collective. From once being a central figure in his kibbutz, Amos is currently irrelevant to his community, 12 refraining from the most basic activities of a “regular” kibbutz member: eating at the communal dining room and participating in the assembly meetings. More abstractly, from being formerly positioned at the heart of the Israeli collective—being a Palmach soldier and a kibbutz member—Amos is now totally peripheral to Israeli society. He is forgotten, living alone with his elderly wife and his Filipino aide.

57 Drawing on Amos’s life story, we can conclude that culture constitutes an underlying theme in tragic narratives in two respects: first, with regard to the distance between the personal life history and the cultural key-plot; and second, concerning the resulting belonging (or not) to the collective. Accordingly, the downfall that marks the tragic storyline implies a dramatic movement from inside to outside, both from the culture and the collective. Echoing Gergen and Gergen’s definition (1988), the tragedy might be the story of an exclusion of one who had embodied the cultural ideal and deeply belonged to the collective; one who was culturally valued but was “torn from” the culture; one who operated in the heart of the collective, but was expelled to its margins. This aspect of the tragic narrative powerfully confirms Gergen and Gergen’s (1988) view of “self-narratives as properties of social accounts or discourse” (p. 19), and more specifically, of narrative forms as cultural products.

58 I hope that in this long essay on Amos’s tragic life story, I have demonstrated the possible utility of analyzing narratives, and possibly also displaying the analysis, by the mechanisms of narrative selection. A meticulous examination of this short text has hopefully raised valuable insights, both regarding Amos’s claimed identity, and tragic narrative identities at large.

Gabriela Spector-Mersel, PhD, is a lecturer in the School of Social Work at Sapir Academic College and in the Department of Sociology of Health and Gerontology at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel. Her research interests include narrative theory and methodology and narrative gerontology, with a focus on culture and masculinity in old age. She has published papers on narrative research and gerontology, and authored the book Sabras Don't Age: Life Stories of Senior Officers from Israel’s 1948 Generation (Hebrew; 2008; Magnes, The Hebrew University Press). She also co-edited (with Rivka Tuval-Mashiach) the first comprehensive book in Hebrew on narrative research, titled Narrative Research: Theory, Production and Interpretation (2010, Magnes and Mofet Press, Israel).

Appendix: Amos’s Story*

- I was born in Poland. I came at the age of two. I came -- (they) 1

- brought me. We at the first stage, because my mother’s family

- mainly, were in Balfur,2 so we came to Balfur for a few years. After

- that we moved to Tel Aviv. In Tel Aviv I was…I studied at the Beit

- Chinuch, the A. D. Gordon Beit Chinuch, and after that at Chadash3

- High School – continuation. And…secondary school. And I was a

- member of the Machanot Olim.4For a long time. Within this

- framework I was sent to the Palmach.5 Because then we had reached

- the point that all Hachshara6 provided a quota for the Palmach. It

- was still before (they) had recruited all the Hachsharas. And I was in

- the Palmach, from the year…’42…no…don’t remember, ’42. I was

- in…2 nd Company. After that we moved over to the 4 th Battalion

- [suppressed weeping]. After that in the Negev Brigade. I was…in the

- beginning a squad commander, after that a platoon commander, and

- after that…an officer in the Brigade, and… That’s how I drifted

- through the army and I finished as a Lieutenant-Colonel. And…that

- was already within the territorial defense. And in the territorial

- defense I met her. [His wife: Not like that, you met me in a radio

- course. You were an instructor and I was a trainee.] Okay. And

- when I was released from the army I came to Gev. Since then I have

- been at Gev. In various roles. Community coordinator, treasurer,

- and…after that I went…to work in the movement. In the UKM. 7 I

- was…in the UKM for six years. Coordinator of the Health

- Committee. I was…and after that back to Gev, I worked for a few

- years in agriculture. After that, (they)assigned me -- (they) assigned,

- I took on the task of establishing a factory, and I established the

- factory called “Gevit.” A paper products factory. And I managed it

- up until I retired, actually. Half-retired. I had already wanted to be

- replaced. And it so happened that today the factory… When I

- established the factory it was…a bit of a problem in Gev. It was a big

- investment, and (they) weren’t used to that. And…in the beginning it

- limped along a bit. And then (they) actually began…to run after me.

- Why did you create this white elephant and why that… In the end

- that factory today, is the only thing that supports Gev. A lot for

- production, a lot… That’s it, until…I got a zbeng.8 A stroke. Since

- then I’m bound to the chair and… The lucky thing is that…as

- opposed to others, and I say as opposed, because I came out with an

- intact mind. It bothers me quite a bit these days. Meaning…the shift

- between disability and activity, it creates a problem for me,

- sometimes I…I think that I [suppressed weeping] am healthy today,

- in (my) thinking. (I) read books, read the newspaper, read…

- television. So when I think that I’m healthy, and I try…to do

- accordingly, physically – doesn’t work. For instance getting out of

- bed, beforehand I got up by myself. Now I don’t get up by myself. In

- walking I’m completely limited. And…and…these days I go back

- and forth between thinking that I’m healthy and the future, that I’m

- limited. And that’s it, it’s already…15 years. Essentially sitting in the

- chair. And that’s a long time. Very long. And along with that I

- have…a Filipino aide. He really does help me a lot. And this is how I

- go through my life. I don’t have much more than that now. I

- was…when I was active, I was a member of the political party

- center, the council. I was…pretty active in the UKM, I was in a

- position, I was a working man – in agriculture, I was in the

- community, community coordinator, I was treasurer. That’s my life.

- Always in public affairs. Until I got sick. I got sick, so it took me out

- of the…frame. I stopped going to the (kibbutz communal) dining

- room – now there isn’t a dining room anymore. (I) don’t listen to the

- (kibbutz assembly) meetings, no activity. I was limited, mostly the

- walking limited me. And…that’s that. About myself. What else do

- you want to hear? Interesting?

* Transcription and notes, Spector-Mersel (2014).