Articles

Peak Oil and the Everyday Complexity of Human Progress Narratives

The “big” story of human progress has polarizing tendencies featuring the binary options of progress or decline. I consider human progress narratives in the context of everyday life. Analysis of the “little” stories from two narrative environments focusing on peak oil offers a more complex picture of the meaning and contours of the narrative. I consider the impact of differential blog site commitments to peak oil perspectives and identify five narrative types culled from two narrative dimensions. I argue that the lived experience complicates human progress narratives, which is no longer an either/or proposition

1 Oil and oil-related events such as the 2010 BP spill in the Gulf of Mexico are part of the story of human progress and important to how people story their own lives. Oil powers lifestyles and plays a role in everything from transportation to food production. In difficult times, such as the oil shocks of the 1970s, the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill, the skyrocketing prices during the summer of 2008, and the more recent BP Gulf spill, our interpretive frameworks and related horizons of hope and despair shift. Interpretations produce everyday narratives of human progress on fronts such as population growth, resource depletion, environmental degradation, and technological advancement derived, in part, from the big story of human progress.

2 Particular to resource depletion, M. King Hubbert developed the concept of “peak oil” during the 1950s as a way to mark the halfway point of world oil extraction (Foster, 2008). Upon reaching a peak in extraction, it will enter a phase of terminal decline in which oil will become more and more difficult to extract. Peak oil is not the end of oil production, but it is the end of the most easily attainable oil. Although it is primarily an ecological issue, this analysis indicates that peak oil is also narratively constructed.

Shifting the Focus

3 “Narrative” is an elusive, ambiguous, and often contested concept (Georgakopoulou, 2006; Sclater, 2003). It can be viewed as a reflection upon and performance of self and identity (Bamberg, 2006; Freeman, 2006; Georgakopoulou, 2006). In that regard, some view it as socially constructed and organized (Gubrium & Holstein, 2009). Others view it as structured in particular ways and functioning in relation to that (Labov & Waletzky, 1997). Narratives are told in diverse and influential contexts with variegated layers, voices, interpretations, and audiences (Josselson, 2011). Storytelling is a way to make sense of the world and our place within it (Bamberg, 1997; Smith, 2003). It is practical and strategic, used to accomplish situated goals in relation to who and what we are and desire to be (Bamberg & Georgakopoulou, 2008; Gubrium, 2006; Gubrium and Holstein, 2009; Kraus, 2006; Pruit, 2011).

4 Narratives are also proportionally related (Loseke, 2007). In this article I analyze the “interplay” between two such proportions—called “big” and “little” stories by Jaber F. Gubrium and James A. Holstein (2009). For the purposes at hand the former are culturally recognized forms producing collective representations (Durkheim, 1961) and the latter are “brief utterances that speakers and listeners treat as meaningful” (Holstein and Gubrium, 2011, p. 1).

5 Recent discussion about methodological approaches draws distinctions between how to accurately record the lived experience. “Big” stories, says Mark Freeman (2006), “entail a significant measure of reflection on either an event or experience, a significant portion of a life, or the whole of it” (p. 132). They are generally prompted in an interview context and tend to focus on “larger constellations of identity” (p. 137). The interview context, Freeman argues, removes storytellers from the hustle and bustle of everyday experience (going “on holiday”), giving the narrators an opportunity to reflect back on their lives.

6 “Small” stories (Bamberg, 2006; Bamberg and Georgakopoulou, 2008; Georgakopoulou, 2006) turn to everyday interactive contexts. They are “employed as an umbrella-term that covers a gamut of under- represented narrative activities, such as tellings of ongoing events, future or hypothetical events, shared (known) events, but also allusions to tellings, deferrals of tellings, and refusals to tell” (Georgakopoulou, 2006, p. 123). This approach examines “what people do with their talk — and more specifically, how they accomplish a sense of self when they engage in storytelling talk” (Bamberg, 2006, p.142).

7 Gubrium and Holstein’s (2009) use of big and little stories is conceptual in the first instance. Big stories are similar to cultural stories (Richardson, 1990), master narratives (Mishler, 1995), and formula stories (Loseke, 2000; 2001; 2007). They are shared arrangements of interpretation. Big stories are far reaching within everyday experience. They are commonly referred to and often provide the underpinning that contextualizes everyday accounts. In a sense, little stories are accountable to big stories.

8 “Little” stories (Gubrium & Holstein, 2009) are the vast array of articulations relating to the contexts in which they occur. Narrators of little stories use the big story as an interpretive resource. Little story interpretations are also practical and relate to everyday experience. They are malleable because narrators reinterpret and adjust positions according to competing exigencies. Analysis of little stories provides an opportunity to document how the big story of human progress influences peak oil interpretations.

9 Little stories and storytelling occur “in relation to specialized interpretive demands, utilizing distinct vocabularies and knowledge” (Gubrium & Holstein, 2009, p. 32). Each is subject to the exigencies of the settings in which they occur, the “narrative environments” (Gubrium & Holstein, 2009). Narrative environments are interactionally situated contexts for interpretation, reinterpretation, and reflection. The narrative environments examined here provide blog participants with the local expectations needed to discuss peak oil and the future of humanity.

10 As a way of making visible the practical nuances of human progress, which are largely hidden in the big story, this article shifts the focus of attention to everyday life, to the varied little stories we convey in ordinary relations with each other. As Holstein and Gubrium (2000) argue about the self, human progress is not just a philosophical matter of either/or, but is narratively constructed in relation to ordinary contexts in which it is considered. Rather than a priori taking on board existing views, I examine two Internet blogs featuring talk related to resource depletion for conceptualizations put into place to portray the future. The aim is to document nuances as they unfold in such everyday sites. As I will show, bloggers formulate human progress in complex terms associated with the lived experience.

Data

11 I followed Kathy Charmaz’s (2006) Constructing Grounded Theory by applying initial, focused, and theoretical coding while using the constant comparative method (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Straus, 1967). I then analyzed human progress narratives following Gubrium and Holstein’s (2009) distinction between big and little stories. The big story of human progress features well-known themes and harbingers, while little stories are everyday interpretations of big story formulations. Internet blogs serve as available narrative environments (Gubrium & Holstein, 2009) grounding otherwise abstract distinctions and providing a narrative context for the little stories of peak oil.

12 Multiple coding phases and procedures, along with the constant comparative method, enhanced analysis while guarding against forcing data into a priori frames (Charmaz, 2006, p. 68). This also directed me toward the interplay of big and little stories. The resultant narrative dimensions from focused coding linked big and little stories during theoretical coding and turned my attention to what bloggers do with their words (Wittgenstein, 1973) to construct narratives and position themselves within those narratives (Bamberg, 1997). This gives a sense of what is going on as well as how it is accomplished.

13 I collected and analyzed data from three sources. Big story data comes from a literature review tracing exemplary historical voices to the present. This sketches a broad background for human progress. Internet data is from a larger study of two peak oil blog sites from April 2005, August 2005, June 2008, July 2008, February 2009, and March 2009. These months feature peak oil talk in full bloom, so to speak, from the time the blogs launched, to when the price of a barrel of oil peaked at (US) $147.27 on July 11, 2008, to the decline in prices.

14 I selected “Peakoildebunked.com” (POD) and “Theoildrum.com” (TOD) because they present exemplary views centering on peak oil and provide contexts for analyzing everyday interpretations of those views. Several blogs discuss resource depletion, but the popularity and practicality of these two blogs made them empirically relevant. The blogs represent differing views and reference each other at times, lending to the richness of the data and linking the sites. They are also meaningful sites of talk and interaction with stakes and interests related to blogger participation. Lastly, the sites are open access and archived, making follow up studies possible.

Method of Proceeding

15 During initial coding, I simultaneously collected and coded Internet data. This phase covered the first month from each site. Data became fractured and partial, resembling expositions. Using the constant comparative method, I began comparing “incidents to incidents” (Charmaz, 2006, p. 53), in this case individual blogger expositions within each blog and month, and then between each blog and month. I used broad working codes that contemporaneously summarized and accounted for them. For example, codes defining the problem, blog philosophy, the other blog, and potential solutions emerged from each site.

16 Upon constructing initial codes I began a focused coding phase. My goal was to determine which initial codes made the most sense analytically by using previously coded data as a guide. I moved between the months by comparing previously coded data to newly collected data, and then assembling codes into working categories. The working categories were consistently refined within and between the blogs using as much in vivo terminology as possible (Charmaz, 2006, p. 55). Some POD categories included “POD is,” and “doomers are,” and some TOD categories included “cornucopians are,” and “doomers are.”

17 Following initial and focused coding of the Internet data, I turned to the related literature. It included resource depletion, population, food production, and technology—properties of human progress also found in the Internet data. I reconceived the literature review as a human progress narrative and began coding it for narrative elements: characters, plots, and maxims. Two polarizing narratives surfaced: utopian and dystopian narratives corresponding with “cornucopian” and “doomer” blogger interpretations. I then began focused coding of the literature to identify dimensions of the polarizing narratives.

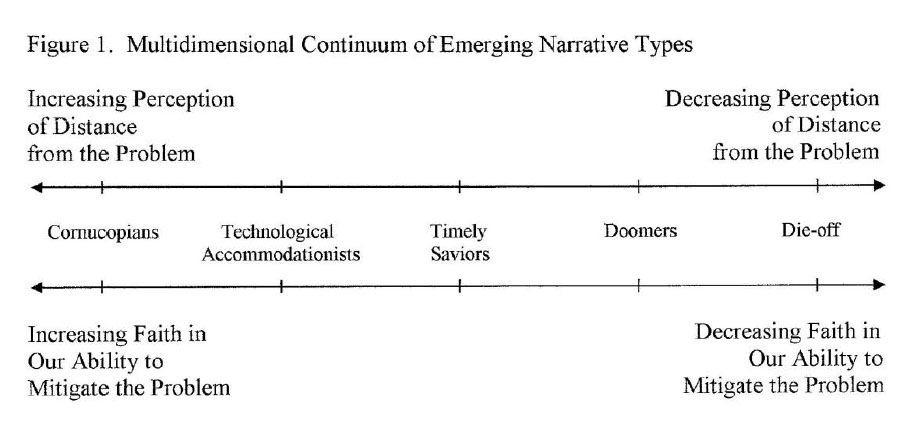

18 During focused coding of the literature, two narrative dimensions emerged as the underlying logic of human progress: perception of distance from the problem and faith in the ability to mitigate the problem. The first dimension reflects a belief in whether or not problems stemming from human progress will arise. Beliefs that population increases will soon cause food scarcity, for example, perceives the distance from the problem as near. The second dimension reflects having faith that humanity will have the ability to transcend any problems. Believing food scarcity is unsolvable indicates less faith in the ability to mitigate the problem. The narrative dimensions position narratives, provide coherence, and link together different narrative proportions.

19 I then reexamined the Internet data using theoretical coding (Charmaz, 2006; Straus and Corbin, 1998) to specify the relationship between my focused coding categories and the academic literature by coding for the narrative dimensions. I found that the narrative dimensions also shape and position narrative environments and little stories. As anticipated, blogger interpretations included polarizing positions (“cornucopian” and “doomer”). However, three additional narrative types surfaced to create a multidimensional continuum, including one narrative type with support from both sites and one that pushes beyond dystopian and doomer narrative borders.

20 In the following analysis I reconstruct academic and everyday interpretations as big and little stories shaped by the narrative dimensions. I first consider the big story as the evolution of a polarizing debate. I then analyze the local expectations of two peak oil narrative environments that contextualize and condition what would otherwise be undifferentiated talk. Lastly I present five narrative types from analysis of little stories that paint an increasingly complex picture of human progress.

The Big Story

21 The leading technological turn in the big story of human progress came during the industrial revolution. Authors constructed a sharp contrast by purporting polemically different positions of human ingenuity. Population, food production, resource depletion, and technology became frequent themes and harbingers of human progress. The associated debate, while strong on particulars, tended toward abstract and binary conceptualization, constructed as utopian and dystopian narratives, and then carried forward by contemporary scholars.

22 Two narrative dimensions are the underlying logic of the big story of human progress: perception of distance from the problem and faith in the ability to mitigate the problem. The dimensions position the narratives and their proponents. The utopian narrative reports there is no problem and human ingenuity is a limitless resource for indefinitely continuing the project of humanity. The dystopian narrative responds that there is a problem and it is near, especially concerning finite resources. There is little faith in the ability to mitigate the problems and humanity faces collapse.

23 The two narratives evolved to include character types such as Condorcet the optimist and Malthus the pessimist, who introduced plots of humanity’s upward and downward trajectory. The narrative dimensions shape the narrative positions and help make the plot believable by providing coherence with the maxim. Big story maxims follow the general purpose of each plotline by encouraging either (1) preparation for social and technological transcendence, or (2) preparation for social collapse.

Utopian Narrative

24 WilliamGodwin (1793) and Marquis de Condorcet (1796) expressed optimistic views of human progress. Godwin believed that “nothing can put a stop to the progressive advances of mind, but oppression” (p. 820). Condorcet (1793) reported

Enlightenment thinkers constructed a utopian narrative with “no bounds” to the “improvement of the human faculties.” They believed human ingenuity would progress indefinitely and transcend any impeding limits and controlling powers. Human perfection is limited only by the duration that humans will inhabit the earth, hence “nature has fixed no limits to our hopes” (Condorcet, 1793, p. 120), human intellect, or technological instruments. Although hardship may occur collapse will not, because little can affect the “happiness of the human race, or its indefinite perfectibility” (p. 129).

25 Underlying the utopian narrative is the faith that humanity will not encounter any problems. This optimism is grounded in the belief that humanity will continue its linear, upward trajectory. The narrators implicitly position themselves as protagonists employing human ingenuity to produce technological achievement, while antagonists try to exert impeding power. The exemplary optimists’ plot is of limitless human ingenuity and technological advancement. The maxim is to trust in the greater good of human ingenuity and scientific prosperity during the process of perfection.

Dystopian Narrative

26 Thomas Malthus (1798) and W. Stanley Jevons (1866) articulated less optimistic views of human progress. Malthus (1798) believed population would increase to exceed subsistence levels (p. 11) and “cannot be checked without producing misery or vice” (p. 11). Jevons (1866) viewed resource depletion as an economic issue. He questioned “the length of time that we [England] may go on rising, and the height of prosperity and wealth to which we may attain” (p. xxi). He reported, “we cannot get to the bottom of [coal reserves]; and though we may someday have to pay dear for fuel, it will never be positively wanting” (p. xxx). That is, coal will never become completely depleted because the costs of extraction will halt it.

27 Underlying the dystopian narrative is a diminished faith in recognizing and mitigating problems, grounded in the belief that humanity will overshoot its resource base, causing collapse. This narrative has binary character types and a tragic plot. Malthus and Jevons positioned themselves as protagonists warning others about impending doom, while antagonists continue down a dreadful path unaware. The plot takes a tragic turn sometime in the future, whenever humanity collapses. The story ends in misery and vice for many. The maxim is that it is best to live within the one’s own means, rather than beyond them.

Contemporary Versions

28 More contemporary versions editorialized the big story (Rambo & Pruit, 2011). In the middle of the 20 th century “rapid growth came to be seen as a result of the exploitation of nonrenewable resources, an idea that had its roots in Malthus's observations about limitations to growth in the means of subsistence” (Price, 1998, p. 214). Contemporary authors discarded general sketches of ideological differences and constructed polarizing character types by juxtaposing utopian and dystopian narratives and characters as “optimist” and “pessimist” (Forester, Mora, and Amiot, 1960, p.1293) and “for or against Malthus” (Boserup, 1978, p. 142). They further characterized Malthus and Jevons as “misguided” pessimists (Boserup, 1978, p. 141) who produced “pernicious” fantasies (Haru, 1984, p.366) and “false predictions” (Boserup, 1978, p. 141). As the main pessimistic character, Malthus promoted “fear” and “somber” views of the future (Rothschild, 1995, p. 729).

29 The big story’s plot continued as a “rather general view of population, resources, and environmental destruction” (Rothschild, 1995, p. 735). Contemporary narrators positioned themselves as commentators outside the human progress debate. They accomplished this by creating “stock characters and recognizable plot structures” (Loseke, 2000, p. 45) including protagonist and antagonist character types (Condorcet the optimist and Malthus the pessimist) and taken-for-granted plotlines (infinite technological progression versus social collapse). Contemporary big story maxims continue editorializing. David Price (1998) assessed the human progress debate as stagnant: “At the end of the twentieth century, debate…is still polarized by the same difference of underlying assumptions that animated the controversy two hundred years ago” (p. 216). Price continued, “[s]o little progress has been made in resolving the debate that one might suppose the difference between the two columns to be more a matter of predisposition than force of reason” (1998, p. 217). Next, I turn to two narrative environments that contextualize everyday interpretations of peak oil.

Narrative Environments

30 Bloggers do not simply talk about peak oil. They position themselves and others in relation to human progress. Narrative environments ground what would otherwise be undifferentiated talk in context. Unlike the big story, there is not a determining position. Narrative environments contextualize peak oil interpretations by providing local expectations for how to discuss the issues. The local expectations exemplify collective representations of peak oil while providing an atmosphere in which little stories can proliferate.

31 Bloggers interpret human progress topics such as population growth, resource depletion, food production, and technology in relation to peak oil. Each site portrays its own interpretations of peak oil as the dominant narrative. In practice, bloggers construct local expectations through interpretations that problematize oil. Questions include: Do oil prices signal demand or supply issues? Are higher prices the road to conservation or collapse? Is pessimism unrealistic, or does an optimistic message ignore reality on the ground?

32 At first blush the blogs present polarizing views of resource depletion, but further investigation draws distinctions in how local expectations shape stories of human progress. PODers local expectations align with the historical experience of technological progression. Participants are optimistically working on peak oil and believe it is a manageable problem. Technological innovation, careful planning, conservation, and exploring alternative energy sources are local expectations for discussing mitigation.

Peak Oil Debunked

33 The enlightenment tradition of technological progression shapes POD’s local expectations. The blog’s overarching position purports scientific optimism, because technology will transcend peak oil, just as it has other concerns. Although it is a serious issue, PODers do not believe it will cause major problems. They have high faith that technological innovation will mitigate it. Instead, bloggers interpret pessimistic attitudes as the main problem. The first set of expositions position the site through its leading voice (“JD”):

34 Solution oriented optimism sets the tone for POD interpretations of peak oil. The local expectations are that optimistic solutions, technological achievement, and careful planning will make peak oil a “manageable technical problem.” History and “biology” teach that peak oil will be transcended through evolution “to the next level,” because “increasing scarcity” does not cause “collapse,” but rather “succession.” The “optimist solution” is “conservation” and then movement toward “alternative power sources.” PODers anticipate conservation will “radically reduce oil use” so that the transition to alternative energy transformations will occur “quite easily” and be “beneficial to the economy.”

35 A closer look at POD reveals that participants problematize pessimistic interpretations more than peak oil and construct an antagonistic (doomer) character. The protagonists (POD) display disdain for pessimists believing technological progression will eventually discredit them. They draw a sharp contrast with the “pessimistic argument” of the “doomer,” which is “based on a series of fallacies.” Below, PODers discuss peak oil as manageable while problematizing the TOD view as untenable:

36 A sign of lowered demand is “demand destruction,” an economic phenomenon forcing conservation via escalating prices. PODers view this as a conservation strategy, not a signifier of “doom.” They believe TOD focuses on oil prices to make claims of societal doom. POD portrays TOD as irrational because its participants do not recognize economic trends. POD participants issue palatable maxims such as “societies are remarkably adaptable,” and it “may blow,” but humanity is not “headed for the Armageddon.” The POD position is that it is “doing something” to solve the problem and “make the grid work.” PODers are part of the solution, while TODers pessimism and lack of scientific faith is the problem.

37 Similar to the utopian narrative, belief in the problem is lower while faith in technological achievement, optimism, and mitigation is higher. Narrative elements, such as protagonists “doing things to make the grid work” and antagonists “sitting around” are present. POD characters plot an “optimist solution” versus a “pessimist argument” in which technological succession mitigates collapse and human ingenuity prevails over “Armageddon.” Levity and emotion ("WE'RE STILL DOOOOOOMED!”;“DOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOMMMMM MMMMMMMM!”; and “dammit”) illustrate PODers local expectations of doomers. Coherence is a product of the narrative dimensions (positioning and plot) and extends into the little stories where the expected maxim is to trust human ingenuity.

The Oil Drum

38 TODers’ local expectations break from optimistic frames, portraying present circumstances as warning signs for a potentially ominous future. The local expectations include being reasonable, rational, logical, realistic, and knowledgeable. TOD characterizes peak oil as a potential cause of catastrophic collapse, shaping how the site orients to oil and related events. It is an event looming somewhere in the future, but interpreted as an immediate concern. TODers have little faith humanity will recognize, accept, and act in time to mitigate peak oil:

39 TOD is “about IDEAS about peak oil.” The goal is to “talk about, inform, and debunk” less credible ideas. The blog claims inclusiveness extending to those who are “not so complimentary and positive” as long as the discussion contains “evidence and reason.” TODers encourage others to “think,” “see both sides of the arguments,” and form “constructive counterviewpoints.” Participants defend TOD even though the ideas may “come across as doomerish.” This is because the blog is a “bulwark of knowledge” for those seeking information. It stands in opposition to “cornucopians, technocopians, denialists, conspiracy theorists and others” by providing a realistic position for peak oil interpretations.

40 The problem of peak oil varies with each site. While POD looks to scientific optimism and human ingenuity, TOD tends to interpret the problem as one of individual selfishness coupled with a lack of societal preparation. The TOD expositions below contextualize how they view the problem:

41 Participants believe TOD is a place for commentary on the problem and that peak oil “confronts people’s selfishness,” causing polarizing reactions. Another problematic is a lack of preparation primarily characterized as a government responsibility. The TOD position is that humanity is close to a “crisis state.” TODers believe that peak oil is near and “don’t put much stock” in things turning out well, because the general public does not care about the “whole energy thing.” Having lowered faith in mitigation, the local expectations are that humanity could suffer from the consequences of selfish individualism and lack of preparation.

42 TODs local expectations are similar to the dystopian narrative. They believe the problem is more immediate and have less faith that it can be solved before major problems occur. This cautionary tale positions the blog as realistic, reasonable, and rational. TODers contrast their views with “cornucopians” who believe human and technological progress will continue indefinitely. The TOD plotline has society progressing until finite resources dwindle and humanity faces collapse. As a subplot, TODers are sending warning messages that defend their views against those who misinform, or do not recognize its significance. In the following section I show how these contexts and the big story are used and multiplied through everyday interpretation.

Little Stories

43 Little stories begin to fill in the spaces between binary conceptualizations, indicating that scholars no longer have the final word on human progress. The narrative dimensions link the big story, narrative environments, and the little stories of peak oil. If previous epochs have produced narrative polarity, then the present epoch characterizes the everyday complexity of the lived experience. This encourages us to push further into how storytellers interpret experience.

44 Analysis of peak oil little stories shows a more complicated scenario than the big story, and can differ significantly from local expectations. There are two analytic considerations regarding little stories. First, I present narratives types that are fairly clear-cut, but the lived experience is not. It is moving, unspecified, overlapping, unclear, and downright ambiguous. People frequently change positions and their accounts change with them. Second, and in relation, categorizing narrative types is a practical endeavor. The lived experience does not allow for an exhaustive categorization of types, as this would continue indefinitely. It does, however, provide adequate grounds for elaborating on the narratives between binary conceptualizations.

45 The little stories use common narrative elements such as stock characters, plots, and maxims. These are resources for everyday narrative practice. The following analysis shows how everyday interpretations complicate the big story. I identify five narrative types positioned along the two narrative dimensions. Figure 1 illustrates a multidimensional continuum – cornucopian, technological accommodationist, timely savior, doomer, and die-off accounts:

Cornucopian Narrative

46 Advocates of the cornucopian narrative envision a utopian-like future exempting humans from natural limits through technological adjustments and advancements. The diffusion process began with the industrial revolution and will last indefinitely. Collapse will never manifest because technology will exceed human needs. There is great faith in the ability to mitigate any challenges via technological developments. Supporters assert new technological advances will continue expanding natural limits. The following POD expositions illustrate the cornucopian narrative:

47 Stock character types and a predictable plotline contribute to the cornucopian narrative. If the “doomers” are “elitist,” then cornucopians are humane optimists. Protagonists assert that peak oil is a non-issue, dreamt up by pessimistic doomers. Technological ingenuity, such as that imagined by the Wright brothers, is a narrative mainstay that will allow humanity to transcend potential problems. This narrative purports that the doomer goal is to spread fear before they unleash a holocaust-like program to cull the human herd (an “elitist human mass extermination program”). However, the upward trajectory of civilization will continue despite the doomer mission. The maxim, like that of the utopian narrative, is to trust in human ingenuity and scientific prosperity.

48 Perceiving peak oil as unproblematic is a hallmark of the cornucopian narrative, because believing in collapse would be “insane.” There is no reason to be “worried” because “scary numbers” have no meaning. “Great people” and “great societies” do not look at limitations, they look for “opportunities and the greater possibilities.” Peak oil will not cause collapse because we already have an infinite amount of energy and “more exotic stuff” to mitigate it.

49 Although there is considerable interpretive play, the cornucopian narrative is consistent with the POD local expectations and aligns with the utopian narrative to a greater degree than other narrative types. Advocates regularly refer to technological optimism to thwart doomer propaganda. They exalt in the spirit of human ingenuity by demonizing doomers and Malthus. Proponents channel enlightenment thinkers by envisioning a technologically limitless future.

Technological Accommodationist Narrative

50 The technological accommodationist narrative reports humans will realize natural limits are on the horizon and make successful accommodations before it is problematic, since peak oil is distant industries and governments have a long time to create the technology of tomorrow. Their faith in the ability to mitigate collapse is high. The expositions from POD indicate humanity will make a smooth and successful transition at the first signs of scarcity:

51 The technological accommodationist narrative has stock characters, plotline, and maxims. This includes antagonists (“your position”) who believe “peak oil will cause civilization to collapse” and protagonists (“my position”) who believe it will “continue to advance and prosper.” Bloggers construct character types by positioning themselves as optimistic and others as pessimistic. Overcoming resource depletion is an economic issue. Proponents believe in the “power of economic change to drive clever new engineering ideas.” The plot purports peak oil exists but is a “manageable problem.” Societies will recognize and mitigate potential problems through technology. Trusting in scientific innovation to overcome problems is the maxim.

52 The technological accommodationist narrative differs from the cornucopian narrative by acknowledging potential problems. Proponents recognize resource depletion exists and believe preparation is important. Similar to the cornucopian bloggers, accommodationists believe human ingenuity will produce the “next exotic energy breakthrough” before problems manifest, so that humanity is “technologically ready.” This narrative shares sentiments of the utopian and dystopian narratives. The solution to peak oil is in the technologies Malthus failed to imagine. Similar to Jevons, supporters treat ecological issues as economic issues (“we should not underestimate the power of economic change”). Mirroring enlightenment thinkers, historical trends determine the future, not “current technological or economic conditions.” The “no growth” view will not come to fruition because humanity will tap into its “real source of power: individuals and businesses with the freedom to use their intellectual resources” (Stabler, 1998, p. 109).

The Timely Savior Narrative

53 Timely savior narrators believe humans will realize natural limits after temporarily overshooting them, and then recover through well-timed adjustments. Instead of a problem free existence, or a problem on the distant horizon, timely savior accounts acknowledge the potential for collapse, but only after circumstances warrant. Faith in the ability to mitigate collapse is in the middle of the continuum, neither overly optimistic nor overly pessimistic. Mitigation will come from hard work, technological advancements, and rational planning. The expositions constructing this narrative type are from both sites, although the majority are POD participants:

54 Timely saviors appeal to a trinary model problematizing polarizing characters (cornucopians and doomers) and their plotlines (“business as usual” and “complete societal collapse”) as a “false dichotomy.” This type of mental coloring (Brekhus, 1996; 1998) constructs a normative perspective. The protagonists report “it’s going to be a little messy,” but “humanity is bent on survival” and “bent on continuing our way of life as much as possible.” Most importantly, adherents “refuse to give up!” Supporters believe in realistic optimism, rationality, and in doing something to help by being reasonable, knowledgeable, and informed. The maxim is that peak oil will be mitigated through hard work and sacrifice.

55 Proponents draw upon and resist all other narrative types, both narrative environments, and the big story. The plotline is that although humanity is “in the face of crisis,” that is when the “best in mankind” emerges, because “where there is a will, there is a way.” Similar to previous narratives, optimism stems from “human will and ingenuity.” Supporters believe “acceptance and recognition” are important before the necessary “massive changes” can occur. Humanity is “on the verge of serious change” and solutions will surface because “there are enough people working and thinking about the problem.” Advocates claim government and industry will prevent collapse with “fiscally responsible ‘sustainable’ behavior.” Similar to previous narrative types, there is a happy ending on the horizon. The maxim is that it will “be a little messy,” “but at the end of the day successful.”

The Doomer Narrative

56 The doomer narrative marks a turn in peak oil interpretations. Advocates argue limitless growth coupled with resource depletion will force collapse unless the historical trends of the past 200 years are reworked. Supporters view collapse as perilously near, or presently occurring. Doomers have little faith in mitigation because humanity does not recognize problems associated with resource depletion. Unlike previous narrative types, mitigating faith is near depletion because humanity continues “running for the cliff.” The following TOD expositions illustrate the doomer narrative:

57 The stock characters reverse positions in this narrative. Protagonists “expect total world collapse” and are trying to warn others, while antagonists “keep refilling their Kool-Aid” and misleading others. Cornucopians’ tarnished view of “uncontrolled growth” now faces limits, despite the “dominant political structure, culture, or level of technology.” Those purporting cornucopian tendencies are leading others into a “nose dive.” Oil is presently peaking and must be dealt with immediately. Doomers acknowledge major systemic changes must occur or mankind will be decimated. In short, doomers problematize peak oil and those unwittingly supporting collapse by not recognizing natural limits.

58 Doomer adherents dismiss the cornucopian narrative. Their plot includes living within the “carrying capacity” of the planet because the current “size and complexity” of modern civilization is “untenable.” Cornucopians “pretend it’s all going to be ok” to “remain sane.” Some doomer advocates have been “waiting for this for 30 years” and are “pleased it’s finally here.” They believe each attempt to rectify the problem pushes humanity closer to the “edge.” The doomer maxim is to recognize and accept problems and prepare as for collapse.

59 The doomer narrative closely resembles TOD expectations and the dystopian narrative. They believe resource depletion will leave society without a suitable replacement, reflecting Malthusian claims about timber. Doomer narrative consequences are unimaginable for the cornucopian and technological accommodationist supporters. PODers believe the doomer narrative paints a bleak picture, while others believe it is optimistic. This stems from the idea that it is too late for any real solutions because we have already reached the tipping point with the four horseman of collapse—resource depletion, overpopulation, global climate change, and environmental degradation. These individuals believe that no matter what type of action is taken it is too little, too late.

Die-Off Narrative

60 Die-off narrative proponents believe the converging crises of resource depletion, overpopulation, global climate change, and environmental degradation will culminate in the end of humanity, regardless of technological advancements. Advocates believe this is good because human practices harm everything and everyone. It is best to let nature take its course. Unlike other narrative types, there is no concern about distance from collapse because we are presently experiencing the extinction of humanity and the death of the planet. Equally significant, there is no mitigating faith because any effort toward change is irrelevant. The die-off narrative is exclusive to TOD:

61 The die-off narrative position differs significantly from the other narrative types. The character types lack protagonists, instead having only victims (the planet and its natural inhabitants) and antagonists (humanity and its practices). The plot problematizes all human conduct, especially current lifestyles leading to complete collapse. While other narrative types have resolution, even if it is only a shred of hope, this narrative ends in total tragedy. There is no escape from the impending crises because the “crash has already begun.”

62 The die-off narrative plot asserts that the only remedy is “collapse and die-off.” The converging crises of “overshoot and habitat destruction” coupled with “peak oil and anthropogenic global warming” leave most of humanity without hope for survival. Most people, including most TODers, do not realize these converging problems will cause an inescapable “bottleneck” similar to the “holocaust.” The elitist “triage” has already begun and those less economically prosperous will likely succumb. The only feasible solution is consciously limiting population growth so less people suffer the “ass kicking Die-off Reality has waiting in the wings.”

63 Supporters emphasize collapse and die-off as necessary and nothing can or should be done to prevent it. There is no reason to attempt mitigation or participate in the “cacophony of public debate.” Unlike other narratives, there will be no bootstrap optimism or exotic technological breakthroughs solving the “larger issue of ecological crisis and collapse.” It is best to “let nature take its course,” which includes the “extinction of our own species” and “every vertebrate of about mean size or larger, along with the end of ecosystems.” The die-off maxim is that humanity’s bed is made and that it is now time to lie in it.

64 This narrative is an outlier in the TOD environment, where local expectations tend toward the doomer narrative. It is incomprehensible to POD, where cornucopian and technological accommodationist narratives dominate. The die-off narrative border is well beyond the misanthropy attributed to Malthus and completely foreign to enlightenment thinkers. The utopian and dystopian narratives and other narrative types entertain at least a sliver of hope, but the die-off narrative brings the chapter on humanity to its dreadful end.

Conclusion

65 Big and little stories can be understood as having a comparative relationship. The big story is often thought of as polarizing and deterministic, while little stories allow for more imaginative agency. Big stories simplify the general contours of a narrative—multiple elements, voices, and perspectives—while the little stories complicate interpretations. However, if big and little stories of human progress relate, it is a reflexive relationship based on the interplay of the narrative dimensions. In this sense we not only live by the big story, but we also live parts of it out in our little stories.

66 The big story of human progress is a guide to the issues, but only partially determines possibilities. The big story is often treated as a set of facts that form basic assumptions about issues, but it is not a fact sheet. It is a moving, living, and breathing part of narrative life, and an important resource in the practice of storytelling. In a sense the big story creates borders that become flexible, if not fluid, in everyday life. Big stories also create collective identities and representations that add context, coherence, and meaning to the lived experience. They present general issues and perspectives that, at times, sweep people up in the drama of everyday life.

67 Narrative environments are places where big and little stories coalesce. They are everyday sites that appeal to the big story, but are porous enough to accommodate the proliferation of individual voices emanating from little stories. Narrative environments mediate the interplay of big and little stories by simultaneously acting as filters while giving occasion for reflexivity. Individuals construct local expectations shaping experience even as individual experience shapes local expectations. The local expectations and narrative practices establish, enable, and constrain emerging human progress narratives.

68 Everyday settings such as Internet blogs turn us to the little stories, to the complex ordering relating to human progress narratives. The narrative types indicate that the big stories in question do not exhaust articulations of human progress. Little stories on the ground—in this case blogger interpretations of resource depletion—present a more complex picture. A multitude, but categorizable, range of views is evident urging us to turn to the lived experience, as much as historical exemplars, for views of the issues at hand.

69 Differential commitments and contexts blur narrative ownership. Because it is complex and not necessarily anchored to a single source, scholars and everyday actors borrow, exchange, and (re)construct human progress narratives and its constitutive elements using the narrative dimensions. Participants align themselves with different narrative positions at different times indicating that movement between positions is not only possible, but expected. For example, “JD” and “Ari” contribute to POD’s local expectations, and along with “Barba Rija” oscillate between the cornucopian, technological accommodationist, and timely savior narrative types. Likewise, “Goose” and “Orbit 500” contribute to TOD’s local expectations that correspond with timely savior and doomer narrative types. “GreyZone” produces a view that aligns with the doomer narrative type, but also contributes to the die-off narrative type, which flexes TOD’s local expectations.

70 The big story, narrative environments, and the little stories are all accountable to the narrative dimensions. The underlying logic of the narrative dimensions is to organize meaning and positionality, which allows for mapping the varying. The narrative dimensions are embedded in the big and little stories as “seen but unnoticed” (Garfinkel, 1967, p. 36) resources that guide interpretation. In practice, the narrative dimensions locate and link multiple positions. This moves interpretations beyond binary representations of infinite progress and catastrophic collapse toward the everyday complexity of the lived experience. In this sense the use of narrative dimensions is a practical accomplishment.

71 In narrative environments outside of the big story we find the countless little stories that complicate the narrative in ways that cannot be drawn from big stories. Little stories reproduce the big stories only partially, taking them well beyond the imaginations of big story advocates. If the big stories serve as guides to the issues, it is the little stories that apply them in practice and provide turning points in the journey. Equally important are the different narrative environments in which little stories are embedded. The blogs considered here are only two of the many environments for articulating human progress.

John C. Pruit is a graduate student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Missouri, Columbia. He is the former managing editor of Symbolic Interaction and Societies Without Borders, and the current editorial assistant for the Journal of Aging Studies. His current interests include narrative, social control, and qualitative methods.