Articles

Stand Together or Fall Alone:

Narratives from Former Teachers

when I am there

But when I drive home it feels like

No, I don’t want this!

(Lena, former teacher)

2 In several countries today the teaching profession is suffering from low status and many teachers leave their profession (Johnson, Kraft, & Papay, 2012; Paine & Schleicher, 2011; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011). As recently as 2004, 25% of the teachers in Denmark, England, and Sweden would have liked, if possible, to leave their profession immediately (Eurydice, Report IV, 2004). A Swedish report from a teachers’ union in May 2012 shows that one in six teachers has left the profession (Lärarförbundet, 2012). Better understanding of why teachers leave the profession may improve understanding of what motivates teachers to remain in the profession and may help to improve teacher retention.

3 I myself am a teacher who has left the school system. Ten years ago I quit being a teacher and my story could also be included in this article, although it is not. I write this only to let readers know that I share the experience of coming to the decision to leave a profession I was trained and educated to perform, but for one reason or another chose not to. My personal reasons included fatigue with relations on all levels (juggling the demands of interacting with children, parents, supervisors, and fellow teachers) and a wish to try a new field, outside the school system, to broaden my horizons. Although I have left the profession, I have maintained a strong interest in teaching and the experiences of teachers.

4 One way to learn more about why teachers want to leave their profession is to ask teachers who already have left why they made that decision; to that end this paper reports four stories from former teachers. Listening to individuals and letting them tell their own stories allows detailed knowledge to emerge, which might be masked in larger, quantitative investigations. Such studies can contribute with data from large samples, as in a Norwegian study with over 1,000 teachers (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011) or in the meta-analysis conducted by Purvanova and Muros (2010) that sought gender differences in burnout. However, in a personal story, details may come forward along with the personal voice. In the narratives recounted here respondents told different stories and gave different reasons for not being teachers anymore, although experiences with colleagues turned out to be a common thread, frequently mentioned, both positively and negatively. The theme of having colleagues and what it means to be a colleague, from both a positive and a negative point of view, was hence further explored. This paper is intended to show the relevance to teachers, teacher education, and schools of addressing questions concerning support and trust between colleagues.

Theoretical and Methodological Framework

5 The narratives are treated from a social-constructionist perspective, which regards knowledge as something created within social contexts and in which subjective accounts are told with the focus on life as it is lived (Hatch & Wisniewski, 1995). It is also assumed that the understanding of an issue can embrace different forms and expressions (Gergen, 1999; Hjort, 2008; Karlsson, 2006; Peréz Prieto, 2003). From this perspective, some research questions are believed to be best answered through a subjective story (Plummer, 2001). When people are asked to talk about their lives, they are given space to express themselves in a way that does not normally occur in everyday social interactions. In the interview situation, expressions of indecision, contradiction, and confusion emerge and help to form a picture of life as it sometimes is— complex and chaotic (Hatch & Wisniewski, 1995). Here, we listen to stories that have led up to a decision to leave the teaching profession. By turning to individuals and listening to their voices, attention is directed toward fragments of life; small parts of everyday life are studied (Fontana, 2003). From that, it follows that each person’s truth embraces smaller parts of life and can be interpreted or understood as relative. Researchers who adopt this point of view often choose to regard their results as negotiated between the interviewer and the interviewee. The interview is redefined and the actual situation, as well as the interaction between the two persons involved, is given greater importance. Objectivity and validity therefore need to be discussed using new standards (Plummer, 2001). One way to do this is to let the reader accompany the researchers’ reasoning and intentions throughout the research process—through the data collection, analysis, and preparation of the presentation of the results. In this paper I strive to share my evolving reasoning while maintaining focus on the respondents and keeping them in the foreground. Bourdieu (1999) claims that such an approach makes it possible for the reader to recreate in the results and the findings both the researchers’ construction and understanding of their data. In this way these narratives about teachers’ experiences, including their reasons to quit being teachers, help us to better understand the conditions for teachers today.

Turning Points

6 The narratives are analyzed in four steps, adapting a model by Pérez Prieto (2007), in which one focus is on “turning points.” A turning point is a break in the narrative, a “before-and-after” incident that in some way contributes to a changed position or outlook. One way to identify a turning point, according to Bruner (2001), is to be aware of a change in the use of verbs that signify a state of mind. The narrator may also more explicitly mark that something changed by using expressions such as “that was the day” or “that was the last straw.” Bruner (2001) claims that at a turning point, individuals free themselves from their history, and he accentuates the difference between the present—the narrator’s awareness—and the past—the protagonist’s awareness.

7 Hodkinson and Sparkes (1997) separate structural, imposed, and self-initiated turning points in working life. The structural ones, such as retirement, are expected and embedded in the social structure; the imposed, such as the closure of a workplace, are outside of the individual’s control, but may not be expected; the self-initiated are acts of the individual, influenced by several factors in that person’s life. In working life, individuals make career decisions within “horizons for action” (Hodkinson & Sparkes, p. 34), meaning that the individual does not have infinite possibilities. The individual’s background and habits, as well as the job market, limit possible options. The content of vocational training also influences what a person thinks of as possible in a particular profession.

Analysis

8 Using the perspective of social construction, I aimed to understand the stories of different people as they were told, from their individual points of view. If I were interested in constructing categories from the interview data, I would lose sight of the individuals. One way I found to keep the stories and voices as intact as possible was to use poems extracted from the interviews themselves. Gubrium and Holstein (2003) suggested the use of poems as an alternative way of working with narratives, and poems have been used in the analysis of narratives by, for example, Ely (2007), Larsen (2003), and Richardson (2002). In using a poetic form for the data presentation and analysis I tried to accomplish two things: first, to shift focus from the researcher’s voice to the interviewees’ own words; and, second, to avoid the insertion of descriptions of the interviewees or the interviews, and thus allow the interviewees’ own words to speak for them. The words in the poems are words uttered by the interviewees. Nothing is added. To reach my purpose I used a model adapted from that introduced by Pérez Prieto (2007), in which the first step is to create a one-page (or so) profile of the interviewee. The profile should be written as closely to the interviewee’s own words as possible. Next, the researcher should identify and reflect upon turning points, small detours, and themes in the story to better understand the narrative. Finally, the researcher should relate the narrative to other narratives from the same person in what often is described as a life history. In this article I adapted and extended Pérez Prieto’s first stage by composing poems rather than profiles from words of the interviewees. In the final step I related each narrative to the larger story. In this case the larger story is not, as in Pérez Prieto, the whole life story of an individual, but rather it is the story of deciding to leave the teaching profession.

How the Poems Were Composed

9 A story might be sprawling and consist of repetitions and hesitant speech; to condense the narratives to their essence I removed such repetitions as a first step. Words or phrases that expressed feelings or atmospheres were saved, to catch the emotion in the narrative. Words marking time were also retained, to give the poem a timeline. At first, the word order was conserved, even when words were removed, but after translation into English from Swedish, this was not always possible.1 With the narratives thus stripped from repetitions, etc., the next step was to break the lines in a more poetic form, a strategy also used by Fitzpatrick (2012) when she transformed interviews to poems. I was guided in this by what I had understood as essential in the stories through several readings, with “turning points” as a main focus, and by my own linguistic feeling. Sometimes utterances about the same thing found in different parts of the original narrative were brought together to better define the chronology. These steps were all taken to clarify the narratives, a little like adjusting the aperture lens when taking a photograph. The poems therefore provide snapshots: summarized inputs of the whole narratives. To allow deeper understanding of each individual’s story, more exact excerpts are presented and analyzed following the poems themselves.

Respondents

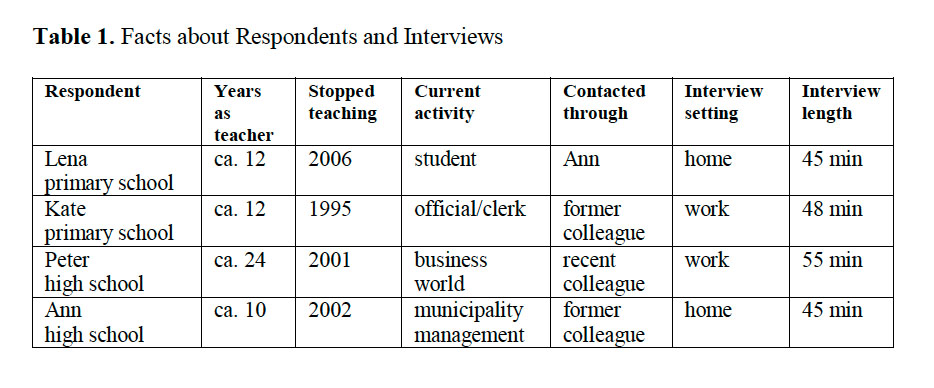

10 The four respondents were found through earlier contacts (see Table 1). When I contacted them they were all very positive about talking about their careers as teachers. To make the interview situation as convenient as possible, the respondents were allowed to decide the place and the time for the interview. Two chose their homes and two chose to be interviewed at their new jobs. I started the interview by posing a three- part question: “What made you become a teacher, how was it when you worked as a teacher, and what made you stop?” Posing the three questions at once was intentional: The respondents now knew the theme for the interview, and they could tell their story without being interrupted by new questions. They all talked almost without pause until they came to a definite end to their story. The table below shows that the interviews did not differ much in length.

Interview Situation

11 To frame the interviews and better allow the reader to follow the research process, I will share the field notes I took immediately after the interviews and disclose how my own experiences as a teacher may have influenced the interview situation.

12 Ann: Age 37, Ann worked as a teacher for 10 years teaching history and Swedish at a high school in both a bigger city and a small town. The interview took place in her home at the kitchen table in the morning. She was by that time on her third maternity leave. The baby slept through the whole interview, no phone rang, and we were undisturbed. We sat opposite each other, which made the eye contact very intense. I noticed that she looked away more than I did. During the interview she spoke continuously. Since I had called her and made the appointment, she had thought about the theme for the interview and was full of her story—it welled out.

13 Peter: In his 50s, Peter worked as a teacher for 24 years, teaching science and mathematics in a high school in a small town. The interview took place at his office, where there was a glass wall out to a hallway; no one passed and we were uninterrupted during the interview. No phone rang and no one came to ask for Peter. We sat opposite each other, but not as close as at a kitchen table. His eyes moved away from mine, but at the end of the interview we made more eye contact. I noticed in myself that I treated him a bit differently from Ann, due to the gender difference. I laughed more, for instance. He spoke most of the time. By the end of the interview he told me that he had talked to high-school students several times about his working trajectory. Peter made many gestures and also used noises or sounds instead of words sometimes. I tried during the interview to interpret the gestures or sounds into words in order to capture them in the recording.

14 Kate: In her 40s, Kate had tried three different jobs after she left teaching. She worked at primary school in a small town. The interview took place at her office, in a conference room; in the midst of the interview we had to leave that room and find another. At the beginning Kate sat at the end of a table with me by her side; in the second room we sat opposite each another which I then found a bit uncomfortable. I knew Kate as a colleague outside of school and we could start the interview at once. She said several times that she was not sure of what she could remember, but now and then during the interview she commented to herself with surprise that she “did not think I remembered this!” Kate fiddled a lot with her stuff, like keys, a cell phone, and lipstick. The first part of Kate’s story was more of a report, not so emotional. When she approached the critical incidents, the story changed character and got more emotional.

15 Lena: She worked as a teacher for 10 years, first in a big city teaching social sciences at a high school, later on in the countryside as a primary school teacher. We did not know each other and chatted for a while before the interview started. It took place in Lena’s kitchen. She had a baby present all the time. It fell asleep at the end of the interview. In the middle of the interview she nursed the baby for a while. We sat opposite each other, but as the baby was present we did not have constant eye contact. The phone rang once, but she ignored it. She was very concentrated and focused during the interview, even with the baby present. She seemed sad and marked by the incidents that had led up to her decision to leave the profession.

16 As mentioned in the introduction, I share with the four respondents the experience of giving up a profession. From the beginning of this project I was a bit anxious; perhaps all the stories would be a replica of my own? As the interviews showed, that was not the case. Here and there I recognized reflections of my own experiences, but only in short snippets, and perhaps due to the fact that we had all had worked inthe same profession during the same time period and in the same country.

17 Before the interviews, I had told them that I was interested in their experiences of being teachers and why they had chosen that profession in the first place. When we met I gave them more information about the study. I also informed them that they could interrupt the interview or withdraw their consent to contribute to the research (Josselson, 2007). They all agreed to continue with the interview. My overall impression was that once they started talking, their stories seemed to just well out. My job during the interviews was mainly to listen, to nod, and to be alert. Many scholars in the narrative or ethnographic field discuss the interaction between the interviewer and the interviewee, how to cope with strong emotions that might arise (Kleinman & Copp, 1993), and how interviewers should ethically behave when they are in a vulnerable situation (Josselson, 2007). These interviews, as I understood them, did not elicit traumatic feelings; the interviewees had all (except perhaps Lena) moved on. The power between us was probably fairly well balanced; I was a researcher, but we had shared the same profession, and as teachers they do not qualify as an exploited or vulnerable group.

18 After the interviews were transcribed I read through them and wrote down some questions that I wished the respondents to clarify, and I also wrote a letter asking if they wanted to add or withdraw something. I sent my questions and the letter to each participant, without receiving any response. I took this lack of response as further implied consent to use the material.

Results

Never felt

I’d like to be a teacher

A mere chance.

Don’t think

I ever understood

what it would mean to be a teacher.

job at once

well-behaved children

interested in studies.

How cool!

got the world’s most trying class

it was

it was completely

yes, it was

the biggest pedagogical challenge ever

One hour

every morning

just to get into the classroom

Didn’t teach much

Listen! Respect each other! Wait your turn!

It killed me

What was it I had chosen?

Appreciated by colleagues

Not by parents

thought everyone saw school the way I did

A shock

I hadn’t really understood, in a way

The social interaction

takes so much energy

too much time and energy

Consuming, nothing nourishing

What did I think was the joy in work?

Work in teams!

planning, using the curriculum

all this theoretical stuff

like the academics

prepare well for class

no fun to be questioned

why you can’t walk into the classroom with shoes on

when I am there

But when I drive home it feels like

No, I don’t want this!

I’d take any job

just let me have lunch downtown

A teachers’ conference

I was group leader

well prepared

This is going to be so fun!

But

I’d forgotten

once again

the others . . .

colleagues from another school

Such resistance!

Went home and just cried like a maniac

Now I’ve had it!

I have to

I’ll go under

if I can’t get away!

Clear, cold days with colourful leaves

I felt such a relief

Gratitude

I got away from school

No words to describe it.

what it would mean to be a teacher.

Lena—From Encouragement to Condemnation

19 Lena entered the teaching profession with the idea that everyone liked school and had the samefeelings for school as she did. Lena truly enjoyed her academic studies (“Can it be this fun to study?”) and she appreciated the theoretical aspects of the work. She seeks intellectual stimuli and gets bored if the teaching content is at a low level. Her first job did not dampen her enthusiasm, but when she moved with her family to a new part of the country, her new workplace was not what she had been accustomed to; she says, “Preparing for advanced questions was completely unnecessary, because that would never happen.” The academic and theoretical aspects of her job were gone; what dominated Lena’s work days were relations and social interactions. She describes her class as “really messy,” and during the first two years “everyone was screaming, shouting, and jumping.” The atmosphere in Lena’s home was affected by her discomfort at work, and her husband and children complained that she was “grumpy and in a bad mood.” This tiresome period was managed with support from her closest colleagues, who saw her as a resource and as someone with the capacity to make a real contribution to the school. Lena said that she had many expressions of appreciation from fellow teachers, such as “Oh, it is good that you want to do this, you do it so well.” On the other hand, there were colleagues in other schools, too. When Lena was asked by her principal to be group leader for a discussion at a conference day for school teachers throughout the municipality, she was stimulated by the assignment, feeling that she had finally come across something “nourishing,” but as it turned out, this was a turning point in another direction:

20 The event with the unsupportive colleagues was the straw that broke the camel’s back and made Lena decide to leave her profession for a while; the supportive and appreciative colleagues at her own school could not erase the bad feelings from that day. She started with a year off, but at the time of the interview she told me that she was determined never to return to teaching. For Lena, for whom academic discussions, further training, and intellectual challenges are important, it was devastating to realize that these were things she would never be able to share with her colleagues. She described the teaching methods at the high school as “stone age” and found it impossible to fit in there. Lena was prepared to put effort and time into her work: “Boy, did I read!” When the other parties disparaged her efforts, she said she felt that “You can’t find something fun or be passionate about it without getting put down.” She felt disillusioned and started to look for some other, more stimulating work.

Further Discussion about Colleagues

21 The teaching profession has been described as a lonely profession, but nevertheless it consists of individuals forming a collective. Teachers, as almost all other professionals, have co-workers who contribute to their well-being or lack of well-being. From that perspective it is not surprising that the teachers interviewed here mention relationships with colleagues as central. Hargreaves (2002) claims that trust “is a vital ingredient of productive professional collaboration” (p. 394). When people feel trust or when there is an existing underlying trust, it is easier to risk a conflict, and thereby develop the work. Trust can have the effect of a lubricant for changing and improving schools, and can even function as a source of morale according to Bryk, Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, and Easton (2010). A Norwegian study highlighted the importance of the feeling of belonging in teachers’ willingness to stay in the profession (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011).

22 Hargreaves (2002), like many other scholars, distinguishes trust between colleagues (lateral trust) from trust within the organization (vertical trust). When trust within organizations is defined, a commonly identified feature is vulnerability (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995), sometimes described as “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party” (Mayer et al., 1995, p. 712). That is, a person is prepared to let another person act, in the belief that those actions will contribute to a greater good.

23 In the narratives presented here, many good things are said about colleagues and the experience of trust. However, there was also talk of problems in relationships with colleagues, and some of these problems were serious enough to predispose teachers to leave their profession. In Lena’s poem we heard both negative and positive talk about colleagues, which are echoed in the experiences with colleagues discussed in the other three narratives.

Kate—When Trust is Shattered

24 Kate described her school as one in which it was never hard to get teachers to do extra assignments, such as taking care of the school library. Kate was part of a group of teachers who always taught grades five and six, and she became the head of one class for only one year. She would have liked to remain in that position for a longer time, but she was happy and pleased anyway because the school was so good and inspiring to work in. Then something went badly wrong. At the time of the interview, more than ten years had passed since the incident, but she still could not tell me exactly what had happened. As far as I understand, some of her students got involved with the police and she tried to support them, but the principal did not support her at all, and what she learned about the events she was strongly forbidden to share with her colleagues. Here is a snippet from her poem:

no one should ever need to deal with

Urgent turnout to help students one night

police officers to school

Reproach from the principal

but when children are calling you . . .

towards everyone

colleagues, the public, everywhere.

Shitty time

my colleagues

terrible

I got hassled

for not sharing what I knew

in my eyes

so totally

the colleagues

my inspiration

when I first got there . . .

25 Kate knew that she had no option, because she was ordered to maintain the strictest secrecy, but she felt her former loved and respected colleagues no longer felt the same about her and regarded her as having done wrong. “I didn’t have the feeling that I was one of the gang anymore, once I had taken the principal’s side.” Nevertheless, Kate stayed at the school, but when reorganization took place and a colleague with whom she used to work well and successfully no longer worked there, things became worse and Kate talked of it as a turning point. She was supposed to cooperate with the teachers who were now antagonistic toward her: “I was thinking that just, noooo, sit here with those who just . . . because I had no confidence in them anymore.” One theme in Kate’s story is how important it is for her to be a member of a team; she wants to belong and have a safe place to work. She was in a dilemma at this school, however, between obeying the headmaster, which seemed the correct thing to do, and pleasing her colleagues, who demanded their own sort of loyalty before allowing her to regain her welcome among them. Kate did what she believed was best for her students, and she made herself vulnerable to help them, but she was punished rather than rewarded with respect by her colleagues. The colleagues’ image of her as a traitor is the feeling she bore with her when leaving school, in spite of the fact that she could no longer respect the colleagues she once almost worshipped.

Peter—Colleagues as Friends

26 Peter’s story is completely different; he thrived at his school, even if he was a bit surprised that he had become a teacher, just like Lena. He liked the contact with students, he liked his colleagues, and he had fun! The school was newly established when he started there, and he was loyal to it until one day, after 28 years, he finished as a teacher:

A small school

young colleagues

great in every way.

Peter talked very positively about the school, his colleagues, and the students. He had a hard time pinpointing why he wanted to quit as a teacher, but after a while he talked about an event that affected him and could be characterized as a turning point, after which nothing was the same. It turned out after all that there was a crack that would split the colleagues. “We were a bunch of colleagues who played in hockey tournaments every Tuesday,” and the feeling that everything was wonderful “lived on, lived on, lived on,” until:

the days of the introduction of

individual wages.

Then something happened, yes

all the old grudges

which we did not know existed!

It was awful!

Some quit, took their bags and just walked out.

27 It is possible that Peter had been naive and had not seen that there were disagreements in the past, but he seems to have genuinely experienced consistency and team spirit before the reform to individual wages from set wages. In Peter’s world, his colleagues thought like him; he uses the pronoun “we” when he talks about the unexpected animosity. When the municipalities and school boards in Sweden introduced individual wages, there were four wage levels, and Peter “came in third there,” next to the top. Not everyone got what they had expected, and those who were at the bottom seemed very discontent, according to Peter. Thus, the introduction of different wages changed the former feeling of “all of us together” to “why did he get higher wages than I?” He understood that to some extent, but was nevertheless happy with his own placement. “Well, what can I say? I had not asked for it!” This event is the only negative one he tells about his colleagues, and the timing was close to his leaving the school. Peter’s picture of his school and his colleagues changed with the introduction of individual wages, and things were not as he had believed them to be. One minute there was a group and the next there were only individuals.

Ann—Supportive Colleagues

28 Ann’s colleagues were a source of joy and encouragement, though at the beginning of her career she was mainly passionate about the students. She was fascinated with the development of students’ potential that the teaching profession could accomplish. Eventually, however, relationships, conflicts, and motivational difficulties with students put a strain on her.

I was like mad with that

But as time went by

all the time

more and more

solving conflicts

motivating teenagers

all the time

motivate, motivate, motivate, motivate.

After a while Ann’s relations with colleagues came to replace the happiness and hope she had first found with her students. Speaking to colleagues is what made her remain a while longer as a teacher: “What gave me strength were our . . . these pedagogical evenings we had together. There we sat and discussed, yes, student influence and things like that.” In the end, that was the only positive thing: “I found, when I was about to leave school, I thought it was more fun to socialize with colleagues than with students.” Ann sought stimulation from adult conversation; she was looking for motivated recipients of what she had to share. Her decision became clear one evening when she was planning her teaching about the French Revolution, once again: “So I just felt, ‘Oh no, now it is time to do that revolution again.’ And I could not motivate myself to find any interest in it at all.” The students no longer offered her the intellectual stimulation or pedagogical satisfaction she wanted, and she finished teaching without bitterness, but more with a feeling that it no longer suited her. Ann has no experience of mistrust or betrayal; on the contrary, it was her colleagues who supported her and kept her going during a hard time.

Discussion and Conclusion

29 The turning points identified in the narratives fall into the category of self-initiated (Hodkinson & Sparkes, 1997); Lena is exhausted and put down, Kate is disappointed and frustrated, Peter just stops, and Ann has lost her inspiration. None of the four left the profession because of any clearly expressed structural or imposed turning points, although the change in salary policy and the effects that had on the teaching staff in Peter’s story may have contributed to, or been the trigger for, his decision to leave his profession. However, self-initiated turning points are influenced by several factors in a person’s life (Hodkinson & Sparkes, 1997) and the aim of this paper is not to identify one reason why these four teachers have left their profession. These are merely turning points identified in the narratives, marked by a before and an after in the story. A turning point does not come out of the blue without any warning; these four people’s lives and stories of leaving teaching, taken as a whole, share the theme of having been marked by a turning point. Other analytical perspectives would likely identify additional themes in these stories, such as the experience of being both a parent and a teacher, or of working in the rural versus urban environment; these questions may be possible to elaborate in another paper.

30 One clear theme, however, in these four narratives is the importance of trust between colleagues. Lena and Ann found a source of strength during tough times at work, Kate found inspiration, and all four found energy and joy in their relationships with their colleagues. Three of the four had a hard fall when trust was breached and nothing was ever the same again. If lack of support and trust between colleagues is an identifiable reason teachers leave or consider leaving school, it is an issue that organizations and teacher education institutions need to ponder and improve. A sense of comradeship is rarely mentioned when teachers’ job satisfaction is discussed, but nevertheless it and the feeling of loss of comradeship turned out to be important features in all four of the stories related here. This is in line with a study Hargreaves (2002) reported from Canada, in which teachers were asked questions about trust in organizations. It turned out that loss of trust or betrayal was very vivid and left emotional scars such as those shared by Lena and Kate.

31 Trust seems to be an important factor underlying teachers’ cooperation with other teachers and their well-being in the workplace (Bryk, Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, & Easton, 2010; Hargreaves, 2002). In this article the focus has been on the importance of lateral trust, of good and reliable interpersonal relations with co-workers on an equal level, for job satisfaction and work engagement (Chughtai & Buckley, 2007). Earlier research concerning trust in organizations has mainly focused on vertical trust, but over the last 20 years, when organizations have been changing and people directed more often to work together in “flatter” organizations and self-regulated teams, it has been obvious that lateral trust matters for achieving effective collaboration (Tschannen- Moran, 2001). Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (1998) argue that it is the diminishment of trust within organizations that has prompted its emergence as a subject of research studies in several disciplines. As long as trust is assumed, it goes unnoticed and unquestioned, both in research and in everyday working life, just as we do not notice our muscles until they stop working. Kate’s story is an example of that: When her colleagues turned their backs on her, she felt lost, deprived of support she may not have been fully aware of.

32 These four narratives and what they reveal about colleagues and trust say a lot about what is important to aim for when organizing teacher education and teacher work. For professionals who carry out knowledge- based work, where problem solving and management of atypical cases are the focus, fellowship between colleagues is central (Abbott, 1988; Hjort, 2008). It is essential that professionals have the opportunity to develop common knowledge and define common concepts, thereby making it possible for them to analyze and evaluate the many difficult challenges they face daily. This does not mean teachers all have to think and act as one person; it means that they should be able to feel confident that they understand common concepts in the same way. It is also very important that they have time to plan, develop, and evaluate their work—both together and individually. And it is vital that they are given an opportunity to build and develop a collegial culture, which includes not only a necessary and reasonable division of labour and quality control, but also opportunities to discuss values, goals, and, in the case of teachers, pedagogy, aimed at defining superior social, ethical, and professional practices. If teachers have frequent and regular opportunities to discuss these issues, simmering disagreements and difficulties may rise to the surface and be handled before they can cause serious problems.

33 Historically, collaboration among teachers has not been one of the “big stories” of teachers. Rather the other way around, teachers have usually been portrayed as working alone and isolated from one another, though studies have set out to prove the connections between teacher collaboration and trust and even students’ outcomes (Goddard, Goddard, & Tschannen-Moran, 2007). In a report from the United States investigating reasons for teachers to leave or remain in the profession (Johnson et al., 2012), social conditions, including relationships with colleagues, feature prominently in predicting teachers’ job satisfaction. Johnson et al. (2012) also claim that a “supportive context in which teachers can work appears to contribute to improved student achievement” (p. 3).

34 In a time when the teaching profession has changed in major ways (Aili & Brante, 2007; Day, 2000; Hargreaves, 1994), and demands on teachers have expanded to include new areas and skills, teachers need each other to redefine how they work and to support each other in this reorientation. As Tschannen-Moran (2001) put it, “For teachers to break down norms of isolation and to sacrifice some of the autonomy they value so highly in order to reap the potential benefits of greater collaboration they must trust their colleagues” (p. 311). The narratives in this study speak for constructing a new “big story,” in which teachers actually acknowledge that they need one another, take advantage of the professional benefits they get from supporting one another, and share information about their work. If opportunities are provided and teachers are encouraged to communicate and be collegial, they will have the opportunity to build lateral trust, which will in turn help to build collaboration and benefit the profession.2

Eva Wennås Brante is Lecturer in Education at Kristianstad University, where she works in the area of teacher education, and is part of a research team in learning design. She is also a PhD candidate at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden; her dissertation is provisionally entitled “Dyslexia and the Ability to Distinguish the Parts of Wholes and Vice-Versa.”