Articles

Landscapes of Memories:

Visual and Spatial Dimensions of Hajja's Narrative of Self

In this article, the focus is on how to represent narratives of self well. This dilemma concerns the specific narrative of self of Hajja, a market woman who lived in the provincial town of Kebkabiya, North Darfur, Sudan. The challenge of "responsible representation" in relation to her narrative concerns the question of how to represent a narrative that does not follow the expected structure of such a narrative. By considering the narrative as a performance of identities in the discursive and material context of narration, the author points out that a narrative is part and parcel of its context of narration. A representation of that narrative should therefore include elements of this context. Not only the discursive and verbal, but also the visual, spatial, and ultimately the temporal dimensions of the context allow us to understand narratives as enactments of self in a specific context. This consideration ties into the current debate on the nature of narrative. Narratives should not only be understood in terms of the what and how, but also in relation to the where and when of their narration. Narratives constitute spaces that allow the narrator a temporal moment of closure, of constructing oneself as a unified, coherent, bounded self in a specific place at a specific time.

1 This quotation comes from Hajja, an elderly market woman whose narrative of self I taped during my anthropological research in two periods that totaled about 16 months between 1990 and 1995 in Kebkabiya, a provincial town in North-Darfur, Sudan.1 I stayed on her compound where she lived with her two daughters and three grandchildren during the second part of my research period (October 1991-April 1992). However, from the first time I met Hajja in 1990, she would recount the same event at different occasions, in similar phrasings. As a young girl, she was singled out to travel from remote Darfur to Khartoum, the capital of the then Anglo-Egyptian Condominium of Sudan, in order to be trained as a medical midwife at the midwifery school founded by the British. She became first in her class, and therefore, she was elected to attend the birth of As-Sadiq Al-Mahdi, who would become prime minister in two of the democratic post-colonial regimes of the Sudan in 1966-1967 and 1986-1989.2 He was the great-grandson of the illustrious Al-Mahdi who founded the Mahdiyya, an Islamic state, by expelling the British who ruled Sudan on behalf of the Ottoman Empire in 1885 (Woodward, 1990, pp. 97-137, 201-239). Even for those who are not aware of the political history of the Sudan, it may be hardly surprising that she prioritized her identity as a British-trained midwife since, in that capacity, she was somehow connected to one of the most famous political and religious families in the Sudan. Assisting in giving birth to one of the few democratic prime ministers Sudan has seen since Independence in 1956 came close to assisting the Sudan being born as an Independent nation-state. That there was another angle to look at her insistence on remembering her time as a midwife, I was only to establish later.

2 During my research, I taped about 22 biographic narratives. Eight were with female teachers, of whom a majority were living at the boarding house near the house I rented during my first period of research (October 1990-May 1991), while the other fourteen biographic narratives were with market women, both elderly and young. The narratives of those women who agreed to let me tape them would have never appeared in print but for my project. By turning their taped narratives into texts, I have in fact "converted" the narratives of self into a new mode of representation for an audience of which most of the narrators only had a vague idea. Even with the hesitations, disturbances, laughter, and other "diversions" transcribed in that text, it is never more than a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional performance and experience.

3 As an anthropologist, I have been part of the contexts in which these narratives have been narrated and taped over a long stretch of time (from three up to sixteen months) in such diverse settings and locations as a kitchen; the compound of the narrator; the marketplace; the riverbed or an orchard; a classroom, office, or boarding house; or, as was sometimes the case, my house. In addition, the narratives sometimes came up spontaneously, while I helped the narrator with her chores, walking in the streets to her or my compound.

4 This was particularly true for the biographic narrative of Hajja. Living on her compound meant I participated in her daily life in both its exciting and its mundane aspects. It allowed me to not just tape her "words" as reflections on her past, but also to witness events she referred to and to experience the way she performed what she narrated. Hajja's narrative was, therefore, part of an ongoing interactive process that included me, and that was one of the reasons I singled her out, as she had singled me out, for an in-depth analysis in my book,3 as well as in this article. Hajja's biographic narrative, or narrative of self, was closer to the "narratives-in-interaction" that Georgakopoulou (2006, p. 239) works with than to the life-stories that she criticizes as being considered the "classic narration," according to the influential model of Labov (1972; as cited by Georgakopoulou, 2006, p. 235; see also Hyvärinen, 2012, this issue), that made most scholarship focused on narratives characterized by:

5 This was precisely the reason I opted for the label of "biographic narratives" instead of life-histories, as it allowed me to "refer more loosely to narratives that women would tell about their lives" (Willemse, 2007a, p. 34). The main question I deal with in this article is how to represent Hajja's biographic narrative in a way that allows for conveying a sense of the immediacy of her narrative-in-interaction. In order to engage in what I refer to as "responsible representation," the narrative is not only to be considered a speech act, but also a performance of the self, which is thus related to the discursive context of performance/narration.

6 My quest to represent Hajja's narrative in a "responsible way" ties into recent debates on the nature of narrative. In his recent work, Hyvärinen (2006a, 2006b) tries to write a conceptual history of the "travelling concept of narrative," in which he detects several shifts in the conceptualization of narrative. He states that the purpose of his emphasis on "the necessary move from the structuralist textuality into contextual storytelling," is "not the search for fixed closures but an invitation to telling new stories from new perspectives" (Hyvärinen, 2012, p. 11). As a most recent shift, Hyvärinen discusses experience-centred approaches to narrative (see also Bruner, 1987, 1990, 1991; Fludernik, 1996; Herman, 2009; Squire, 2008, all cited in Hyvärinen, 2012, this issue). For my argument, the experience-centred approach to narrative as referred to by Georgakopoulou (2006) as so-called "narratives-in-interaction" is of interest. Despite the fact that Georgakopoulou considers "narratives-in-interaction" to refer in particular to "small stories" like emails that have less "tellability" (pp. 238-239), I consider the biographic narratives of the women of Kebkabiya, such as the one narrated by Hajja, to be constituted by interaction as well. These narratives were also not "elicited" in a controlled environment of interviewing, but rather, were the result of the multiple interactions in and with the context of narrating, of which the researcher also formed part. This aspect makes these biographic narratives equally less controlled, "less polished, and less coherent" than the narratives that are recorded in a controlled interview setting (see Ochs and Capps, 2001, pp. 56-57; also cited in Georgakopoulou, 2006, pp.237-238).

Intertextuality: The Sudanese Government's Discourse on Women, Islam, and Work

7 This still leaves open the question of how to represent these "narratives-in-interaction" well. In my search for a means to do so, I will start from the empirical level of Hajja's "narrative-in-interaction." Close scrutiny of Hajja's context of narration leads me to understand the context as part and parcel of the narrative and vice versa. In taking a more self-reflexive stance, and "reading" the context of Hajja's narrative as constitutive of that narrative, the visual and spatial dimensions of that context prove to be important to understanding her narrative properly. Therefore, I will argue, the analysis and representation of a narrative should include, not only what Hyvärinen (2010) calls, the "what" and the "how" (p.78), but also the "where" of narratives, in the broadest sense of the term (Georgakopoulou, 2008, p.236; Willemse, 2007a, pp. 149-156). The intertextuality of Hajja's narrative is related to the discursive context of narration. Kristeva (1986) refers to intertextuality as "the insertion of history (society) into a text and of this text into history" (p.39; quoted in Fairclough, 1992, p.101). I use this perspective of intertextuality and consider it from the perspective of the narrator and her audience as “the sum of knowledge that makes it possible for texts to have meaning” (Meijer, 1993, p. 23; 1996, pp. 369; see also Fairclough, 1992, pp. 103-105). A narrator will try to understand her life and her identities in relation to discourses that are dominant at the moment of narrating. Discourses on gender often tend to be based on a notion of morality, on a distinction between proper and improper ways of conduct for men and women. Narrators, even if they do not articulate the dominant discourse that is of importance to their positioning, will in their reflections always argue with reference to these dominant discourses (Billig, 1991, pp. 2-6, 17; Willemse, 2007a, pp. 449-495 ). In other words, narrators will try to negotiate their gendered identities by referring to these dominant moral discourses in order to gain some moral leverage (Mills, 1997, pp. 77-102, 131-159; Fairclough, 1992, pp. 103-105; Mahmood, 2005, pp. 3-15).

8 An important shift in the dominant discourse on gender occurred at the time of my research. The Islamist government that had just come to power in Sudan in 1989 had embarked on what it called al-Mashru' al-Hadari, the civilisation project. The project focused on women in the public domain in general, and in Darfur in particular, as the region was considered the “least Islamised” after the South of Sudan. The Islamist government's discourse on gender stipulated that the most important role for women was to be a mother within the walls of their compounds. Women therefore, should not enter the public domain and should abstain from working outside their homes. In religious speeches organized by the government, Darfur women, who are renowned for their hard work outside their homes, were explicitly addressed and urged to return to their compounds and become “good mothers” who would raise the next generation of Sudanese Muslims.

9 The religious speeches were delivered by the newly established religious committees that consisted of government-employed, educated men and women. Educated women had few options for employment: either in one of the government organizations like ministries or parastatals, such as television broadcast organizations, but mostly as teachers or in one of the medical professions. In Kebkabiya, most educated women were employed as teachers and they were referred to by the government as the example of the proper Muslim woman, as their education made it possible for them to read the Qur'an and understand Islamic teachings correctly. At the same time, they “knew how to behave,” as I was told by government officials. Not only did they have worldly and religious knowledge ('ilm), they had also been taught the rules of conduct for Muslim women, both inside and outside the house: rules based on the educated elite's notion of correct gendered behaviour. The new Islamist government decreed that all women in the public space, including the female teachers, were to wear head-scarves where they had not done so before, since the Sudanese tobe, a four to six meters long cloth that women wrap around their clothes as an outer garment, was now considered insufficient as an Islamic dress for women.4 In any case, female employees were cast as the example of the proper Muslim woman.

10 Female government employees were juxtaposed to market women, who were referred to as those conducting themselves improperly as Muslim women, since they dealt daily with “non-related” men (ajnabi) while selling in the market. Selling in the market also meant they could not tend to their children in the way proper Muslim mothers should: within the confines of their homes. Market women were at that time continuously threatened with forced removals, as had happened elsewhere in towns in Sudan under what came to be known as the kasha-raids. In Kebkabiya, this fate had already befallen the women selling coffee and tea from their tiny stalls in the market place. They were accused by the government of causing fitna (sexual chaos or promiscuity) in the public space, as their trade allowed men to stay in their vicinity for a prolonged period of time, leaving ample room for sexual liaisons and other dishonourable contacts. Market women were cast in a similar position, for they, too, would deal with male customers who were not related to them: and their work would also prevent them from being “good” mothers. Market women were thus continuously threatened with forced removal. I therefore had to consider Hajja's narrative in this discursive context in which her livelihood was at stake.

Hajja's Negotiation of Selling in the Market: “Othering” While Claiming a Moral Positioning

11 During the first months of my stay in Kebkabiya, I would usually meet Hajja in the market where she was, most of the time, selling onions and peanut butter, and sometimes garlic as well. For me, Hajja was therefore primarily a market woman. It was only when I lived at her compound, in the period in which I taped her biographic narrative in several sessions, that I realised her situation was more complex.

12 Hajja did not consider herself to be a market woman. Even when Hajja went to plead her case at the government offices when the government decided to deny market women the right to sell food and drinks to travellers during Ramadan, she did so as an elderly widowed mother who had to cater for the needs of her daughters and grandchildren. Whenever I tried to engage Hajja in a discussion of her market activities, she was elusive: she would send me to other women, telling me that they “would know more about marketing since they were 'real' market women,” referring to the women who were selling fresh fruit and vegetables on a daily basis in the central market square. Only on one of the two market days, Mondays and Thursdays, when she was sitting at her place at the margins of the market, would she answer my questions about her own experiences as a market woman, however reluctantly. Even in those rare instances, it was clear she did not want to be seen as a market woman. During one of the first talks I had with Hajja when I inquired about the time she started selling on the market, she answered:

13 In this small quotation, Hajja is making two statements that are of importance to my argument. In the first place, she tells me when she did not go to the market. The information I get is clear; the death of her husband forced her to sell in the market, which meant she did so out of need rather than by choice. She continues to negate her position as a market woman by pointing out that in the period she was not a market woman, she would go out of the house to perform her duties as a midwife. As her husband himself made breakfast for their young daughters, she establishes her status as an honourable Muslim woman since this meant that her husband was not only fully aware of her work outside the compound, but that he even supported her in performing her job by taking over her duties as a mother. It meant that she was complying with the notions of an obedient wife and a good mother according to the current government's discourse on gender. By the end of this quotation, she points out that she only became active in selling in the market when her daughters were old enough to fend for themselves. In addition, her market activities allowed her young daughters to stay within the confines of the home or to board at school. She was thus, again, not neglecting her duty as a mother. On the contrary, being now past menopause and thus past a sexually active life stage, she constructs her selling in the market as a necessity for an elderly widow who as a mother, in fact, had prevented the fitna that might have been caused if she had sent her young, sexually active daughters to sell in the market. She thus constructs herself as someone who not just understands, but also actively acts according to the same dominant discourse that threatens to prevent her from selling in the market. Hajja thus claims a morally justified position as a mother and as a market woman. To do so, she has used intertextual aspects of the dominant discourse—notably the relation between selling in the market, sexual promiscuity, and improper Islamic conduct—to negotiate her position as a proper Muslim woman and a working mother.

14 The construction of her identity as a working widow by negotiating the dominant discourse on gender, work, and religion is only one of the multiple identities Hajja performed and narrated. Moreover, she, in fact, put forward her identity as a midwife as her “real” position as a working woman. This confronted me with some problems of representation, which I will deal with in the next section.

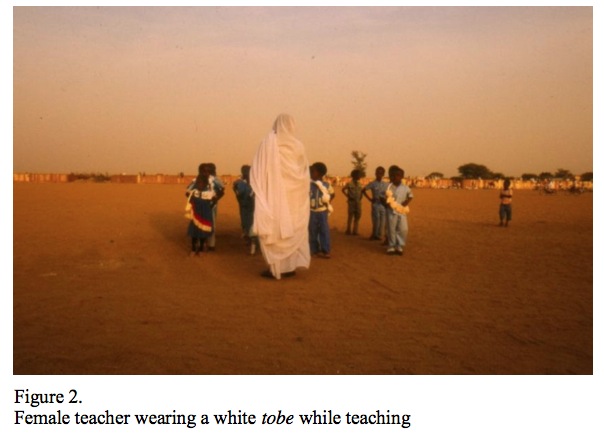

The Non-Verbal: Visual and Embodied Anchors in the Context of Hajja's Narrative of Self

15 As a feminist and critical anthropologist, my main aim was to engage in what I call con/text analysis and research “against the grain,” which should lead to “responsible representation” (Willemse, 2007a, pp. 1-44, 135-147, 449-495; Davids & Willemse, 1999, pp. 1-14). This meant that I wanted to stay as close as possible to Hajja's original narration. It made me consider not only the obvious meaning of the narrative, but also the way the context of narration might have had a bearing on the kind of identities that the narrator thereby tried to construct.5 As I consider identities to be performative rather than innate (Butler, 1990, pp.270-282; 1993, pp.128-226; 1997, p. 20; De Certeau; 1988, p. 123), this led me to try and understand how Hajja, by narrating about her self, performed her multiple identities in the context of narration, in the light of her past and her present. In addition, a “responsible representation” implied for me that I was to represent Hajja's narrative in such a way that it would cast Hajja as the agent of her own life and of her narrative performance of that life (Hyvärinen, 2006a, p. 30; see also Ricoeur, 1984, p.55). This confronted me with several dilemmas.

16 First of all, as I showed above, even though she was able to construct her selling in the market as a morally justified act, most times Hajja was reluctant to discuss her market activities at all, especially when we were outside the market place; most often, she would direct me to other women selling in the market who “knew more about it.” If she was performing certain activities in the market in order to earn money, that did not make her, in her own eyes, a market woman. On the other hand, she relished talking about her memories of her position as a medical midwife. Evidently, she positioned herself first and foremost as a medical midwife. I had, however, never seen her practicing her midwifery skills. On a few occasions, I saw her going to or returning from tending to births, but not as often as Hajja would want me to believe. Due to her age, her eye-sight had become poor, which meant she could not venture far from home anymore at night, nor could she see much of what she was doing in the weak lamp or candlelight in which nightly births would take place, as there was no electricity. She might, however, have made up for these shortcomings by her experience and the talent she had for midwifery. She also had less energy and stamina to work all night in cases of prolonged labour. Recently, two younger women had joined her as medical midwives. Hajja told me vividly about her activities, the many babies she delivered and the problematic births which she knew how to bring to a successful ending. But to an anthropologist, participant observation of those activities are a sine qua non to understand and represent those activities well. So how could I represent Hajja's identity as a midwife “in context,” if I knew hardly anything about the enactment of her identity as a midwife in a particular context? When, on a return visit in 1995, I tried to explain to Hajja what I had done to her narrative by analyzing it in order to get her consent as well as some advice as to how to represent her narrative, she looked at me, saying "all I said was true." Next, after she checked if my tape recorder was running, Hajja started to re-tell her narrative by again recounting the birth of as-Sadiq al-Mahdi, which I quoted at the beginning of this article. It was clear: Hajja had narrated her narrative and thereby constructed her identities to her own conscience; now it was up to me to decide how to represent her narrative well.

17 Another matter concerned the fact that, although Hajja had a good memory, she liked to talk about her life, and she had a lively way of narrating, her narrative was patchy and seemingly incoherent if compared to some of the other narratives I taped, in particular those of the female teachers. This might have been due to the fact that I taped her narrative in several sessions, since she was quite a busy woman. But so were the female teachers. In both cases there were hardly any long stretches of narration, and we were often interrupted. It was not so much a matter of my expectations of what a narrative of self should look like that bothered me. As I pointed out above, my aim had not been to “gather life-histories,” but rather narratives that centred in whatever way on notions of self, which I therefore labeled biographic narratives. My hesitation to represent Hajja's narrative as “all over the place” was related to the fact that her way of telling about her life differed from that of the female teachers precisely in structure, since the latter did use a certain chronology when narrating about experiences and events. I did not want to make Hajja seem incoherent, or out of control of her own narrative, as it would tie in too neatly with the division that the Islamist government had constructed between both classes of working women with reference to the notion of ilm (knowledge). As indicated above, this referred both to religious and worldly knowledge, and is seen as one of the first obligations of Muslims to acquire, after keeping to the five pillars.6 In the context of Sudan, it also implied knowledge of the etiquette and code of conduct of the educated elite, and it marked one's position as a member of the educated elite class. The way the female teachers narrated their lives therefore constituted locally a model for a more sophisticated way of telling about one's life and thus constituted a quality of being educated— perhaps, not accidentally, a model that is related to the expectations of my audience “back home” of how a narrative of self should be structured.

18 So, even if my analysis of Hajja's negotiation of the dominant discourse as a market woman, mother, and good Muslim provided space for pointing out her agency, it did not challenge the division among women as constructed by the dominant discourse on the basis of education. It left intact the boundaries between different classes of working women, as articulated by the Islamist government's discourse on the proper Muslim woman. If I just wrote down Hajja's narrative in the way she had narrated it, I ran the risk that the expectations of both the local and transnational audiences for whom I was writing my book would experience Hajja's narrative as less eloquent and as revealing less of an overview of her life than the female teachers' narratives, even if I were to caution them not to. I realized that, if I was to cast Hajja as an agent of her life and of the narrative about that life, I had to include in my representation more of the context of her narrative and thus of performing her identities. I had to show, rather than tell, more of both Hajja's and my own interactions with the context of her narration.

19 It is precisely this aspect of tying the narrative of Hajja to the context of narration that makes Georgakopoulou’s (2006) notion of “narratives-in-interaction” attractive. Georgakopoulou thereby zooms in on the intersubjective level of narratives, in the sense that she looks at how narratives are the result of communication between subjects on shared themes (pp. 230-250). In a similar way, an important aspect of Hajja's “narrative-in-interaction” was the interaction with me in my capacity as anthropologist, as audience, witness, translator, and thus interpreter of Hajja's narrative. Engaging in Hajja's life, and those of other women, practicing “participant observation” meant I did not only witness the daily lives of the women I worked with, but engaged in an intersubjective process of knowledge production as well. Precisely because of my “situated” and “embodied” knowledge of the context of narration (Braidotti, 1991, p. 219, pp. 155-168; Davids, 2011; Schrijvers, 1993; 1995, pp.19-29; 1997; Willemse, 2007a, p. 365; Davids & Willemse, 1999, pp. 1-14), I, as the interlocutor who was representing that narrative through hindsight, had to try to convey something of the context in which the narratives were told, and of which I had become a part, as well.7 “Narrative-in-interaction” refers to the way that Hajja interacted with other subjects, as well as with the non-verbal aspects of the context of narration, both material and immaterial. Understanding this context might allow me to find a way to represent Hajja's narration in the way she had presented it, while retaining her position as an agent of her life.

20 A first realization of the importance of non-verbal aspects of her narrative struck me when I asked if I could take a picture of Hajja and her family. While most women, including some of the married female teachers, would dress up in their most beautifully coloured tobe, Hajja insisted that she wear her white tobe. Her white tobe actually had a red rim and that may have distracted me originally (see Figure 1). Only when I saw her wearing that same tobe when she was going to the hospital for attending to a birth did I realize that this was, to Hajja, the “white tobe.” White tobes are the prerogative of women who are employed by the government. It marks them as professionals in government service and thus part of the educated elite. By wearing her white tobe in a “private” picture with her family, she in fact enacted and prioritized her identity as a medical midwife.

Display large image of Figure 1

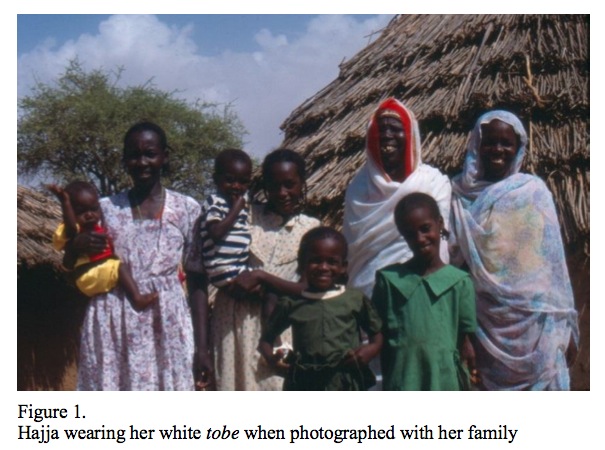

Display large image of Figure 121 At the same time, she thus negotiated the dominant discourse of the Islamist government, since it had pointed out that female teachers, as one group of government employees, were to be seen as the example of the proper Muslim woman. Despite the fact that teachers would also leave their compounds in order to perform their jobs, they had not only acquired ilm, but were in fact, in their capacities as teachers, transferring ilm to their pupils. This made their job religiously approved and even necessary in order to create the next generation of Sudanese as “proper Muslims” in the eyes of the Islamist government. When female government employees were performing their jobs, whatever grade or position within the government ranks they had, they would wear a white tobe (see Figure 2). Thus, by wearing a white tobe, Hajja was not just constructing an identity as a midwife: she thus marked herself as a female government employee. Since midwives were indeed employed and (supposed to be) paid by the government, her claim was valid. Even though she could not read or write, and distinguished her medicines and vaccines by taste and smell, she thus constructed a commonality between the example set by the Islamist government of the proper Muslim woman and her own position. It made sense that, in this discursive context, she downplayed her position and positioning as a market woman, but rather, considered herself a widow who occasionally engaged in marketing activities in order to be good mother—in other words, to provide for her young daughters. At the same time, constructing herself as a female government employee in her capacity as midwife was not just a verbal strategy, but was also enacted by wearing a white tobe. Even when the government had not paid her expenses for a long time (apart from her monthly allowance and her tobe, they were also supposed to provide her with soap, medicine, and vaccinations for her midwifery chest, and to pay her transportation costs), and she had received the white tobe as a present from her maternal cousin (which was why it had red rim, when the official white tobes did not), she did not dwell too much on this neglect by the government, since she wanted to construct herself as part of that government, not to be taken as someone protesting against it.

22 By taking heed of the context in which Hajja performed her narrative and by looking at non-verbal, embodied aspects of her narrative as a performative act, I could better understand how the narrative of Hajja's past served, in fact, to construct an identity in the present, in the context in which she narrated her past. However, it still left me with the problem that I wanted to represent Hajja's narrative in a proper, “responsible” way, since I considered her narrative, as I stated above, as part of enacting her agency. As the female teachers were seen as the example of the proper Muslim woman, their way of talking about self, using standard Arabic instead of Hajja's colloquial Arabic, and using chronology as a means to structure the articulation of their memories, surely constituted the model after which biographic narratives were locally supposed to be narrated. However, if I edited her narrative, cleaned up her phrasing, or altered her way of speech, that would equally deny her agency. These solutions were so far removed from my notion of “responsible representation,” in the sense of staying as close as possible to the way her narrative was told, that I searched for an alternative.

23 I realized that, only by taking the notion of “performance” more seriously and taking the notion of “interaction” more literally in the way that Hajja told her narrative, I might find a way to properly represent her narrative as both a verbal and non-verbal performance of her identities and a negotiation of the dominant discourse. Being more self-reflexive led me to include in the analysis of Hajja's narrative both our interactions with her environment, not just as a discursive and intersubjective context, but also in its locational capacities. I thus detected an almost “natural” coherence to Hajja's narrative: a coherence that was offered by the landscape she was able to discern in the environment she lived in and which constituted the self-evident anchors of her memories.

A Landscape of Memories: Mapping Hajja's Narrative

24 The triadic relationship of a narrator, the narrative, and the environment struck me when Hajja and I got a lift from her field into town in the car of a local merchant. After we had crossed the dry riverbed and the car started climbing the sandy embankment of the Wadi, Hajja opened her hands as if reading a book, a sign of doing ta'ziya (consolation), commemorating a dead person: a gesture I had witnessed just after a person had died as a sign of offering one's condolences. When I asked her who had died, Hajja replied: “My father, a long time ago. The cemetery used to be here at this side of town.” Apparently, Hajja had a different map in her head than the one obvious to me, as there were no markings of graves like stones or wood: just a plain of sand. That this map was conducive to her narrative of self was only clear when on Wednesday, Hajja made a similar gesture at the outskirts of Kebkabiya, near the government offices. I spotted only an ankle high wall around a dead looking tree. This was the grave of her stepfather, Faqih Siniin, Hajja told me, the alleged founder of Kebkabiya who was remembered as martyr of the last Fur Sultan Ali Dinar and revered as a faqih (a religious leader). His gubba (tomb), marked by the dead-looking tree, was now visited by those in need of baraka (blessings) for prosperity, health, or fertility. When I inquired about him, she promised we would go and visit his tomb to ask for my prosperity and the health of my loved ones next Wednesday, the day of commemorating Faqih Siniin as a saint. That same Wednesday afternoon was the first time Hajja related to me the narrative of this local hero, her mother's first husband and therefore her stepfather in name only.

25 Thus it occurred to me that Hajja narrated her memories when having visited a part of town, the town where she had lived with minor intervals since her youth, which would then trigger certain memories and would conjure certain identities that belonged to those spaces, both as memories of her self in the past and their meanings in her present life. Her environment constituted an archive, with layers and layers of memories and selves that stood out to her as markers in a landscape. These different layers, memories, meanings, and selves were, moreover, organized not only spatially, but also temporally: Faqih Siniin's commemorative day was a Wednesday, so we visited his tomb on that day, and Hajja told me about him for the first time on that same day. She would discuss marketing only when we were in the market, which meant mostly on a Monday, since most often on a Thursday, the main market day, she would be most of the time too busy with her customers. Friday would be a day of prayer in the mosque and thus a day to speak of religious issues and her status as a good wife. Her husband had been a wealthy trader and a renowned head of the market, working for the British; his business acquaintances, family, and friends used to visit their compound after prayers. Saturday was a day of working in the fields, in the home, visiting neighbours and family members, or occasionally a day of rest: moments of chores and leisure she would share mostly with her younger co-wife and her sons and daughters. Sunday would be a day to prepare the goods to sell in the market, the first market of the week being the next day. Midwives could be called to duty at any moment, whenever a birth required their attendance at the hospital close to her compound or at the pregnant woman's house; so a midwife she was all along, all the time, underlying all other responsibilities now her daughters were mature and could fend for themselves, relieving her of her caretaking responsibilities as a mother.

26 Hajja's narrative thus was from the onset literally “all over the place”; her surroundings provided an obvious, coherent, and almost tangible way of ordering her narrative. Her narrative was part of the context in which Hajja experienced and enacted both her past and her present by narrating about her self. She did not need any narrato-logical devices to tie her memories to in order to give her life an idea of chronological unfolding; rather, her narrative had a charto-logical structure in the sense that it was guided by a chart of her surroundings containing the memories that mattered to her. Hajja's life—past and present—was there, in front of her eyes, within her reach, under her feet, with the faces, the smells and sounds that belonged to the fragments, the episodes, the memories as well as the everyday rhythm of it: and so for me, as well.

27 Since I had become part of that daily routine, I understood to some extent the local habits, hierarchies, and power struggles. Hajja obviously trusted me to be able to translate and interpret her narrative as the interlocutor I had become by living in the town of Kebkabiya, on her compound; locally I was positioned as naas Hajja (people of Hajja). Hajja had attached her memories and her re-living of them to the places-turned-spaces we encountered in her daily life, which apparently made Hajja consider me informed enough to understand the charto-logical nature of her narrative: to recognize the landscape of her memories and use them as the markers of her selves, thereby making the mapping of her narrative of self, self-evident.

Discussion: Spaces Are Practiced Places—and So Are Narratives

28 What does the understanding of the chartological structuring of Hajja's narrative performance add to the discussion of the nature of narratives? By trying to solve the dilemma I faced as a researcher of how to engage in “responsible representation,” and therefore to understand and represent well the seeming fragmented nature of Hajja's narrative, the journey has led me to acknowledge that a narrative of self should not only be analyzed for its narrative content and its form. Hyvärinen concludes that “narrative, therefore, can reside either in text …, in communication …, or in reception of a text” (Hyvärinen 2006a, p. 34), which corresponds to the conceptualization by Tammi of narrative as a discourse, a speech act, or a cognitive schema (2005, quoted in Hyvärinen 2006a, p. 34). I want to add to these conceptualizations of narrative the spatial dimension. This spatial dimension is tied to the temporal dimension of the narrative as a powerful means of understanding the way a narrator positions herself within the context of her performance. Like Georgakopoulou (2006), I consider narratives as embedded in discourse surroundings (p. 252), which means that the study of narratives needs to be "spatially and temporarily expanded to capture the dis-embeddedness and the reembeddedness of stories: the ways in which stories are transposed, (re)shaped and recycled across time and space in different contexts" (p. 252). I agree with Georgakopoulou that narratives do not necessarily unify or integrate a notion of self, but "can be seen as ongoing projects in which improvisation, contingency, contradictions and fragmentation are equally—if not more—plausible and worthy of investigation" (p. 254). At the same time, what seems fragmented to the listener, the researcher, may be perfectly coherent to the narrator. It is precisely our task, as those who represent these narratives, to take into account the ways narrating about one's life as a performance constructs notions of self as unified, coherent wholes, and understand the agency of the narrator in trying to attain closure, even if just for the moment of narrating. In trying to solve my dilemma of how to represent this process of narrative construction in a responsible way, the visual, spatial, and temporal dimensions of the narrative as performance proved to be highly relevant.

29 "Space is a practiced place" states De Certeau (1988, p. 117). In Hajja's narrative, seemingly inanimate places, such as the dry riverbank or a dead tree, were transformed into lived spaces of the experiences and identities of Hajja's past and present at one and the same time. Hajja's narrating in and about certain places-turned-into-spaces was thus both a reflection of an experience and itself an experience: both the representation and the enactment of Hajja's identities, thus validating the notion that "space is existential" and "existence is spatial" (De Certeau 1988, p. 117). This means that "there are as many spaces as there are distinct spatial experiences" (De Certeau 1988, p. 118). Narratives indeed refer to multiple spaces and constitute the enactment of multiple identities. Hajja prioritized in particular contexts certain identities at the expense of others which were thereby downplayed, which made sense in the discursive context of the present. Thus, if narratives are to be analyzed on not just what is being narrated, but also on how it is narrated, this how leads us to consider also the where of narrative performance. This where not only inheres in the performative, but the spatial and temporal as well (Willemse, 2007a, pp. 364-367). In that respect the where comes close to the notion of Chronotope (space-time) as defined by Bakhtin (1981), which refers to "points in the geography of a community where time and space intersect and fuse. Time takes on flesh and becomes visible for human contemplation; likewise, space becomes charged and responsive to the movements of time and history and the enduring character of a people....Chronotopes thus stand as monuments to the community itself, as symbols of it, as forces operating to shape its members' images of themselves" (p.84; as cited in Basso, 1984, pp. 44-45).

30 If spaces are practiced places, narratives constitute spaces that, however temporary, and time and context-bound, allow us to perform our selves, to negotiate subject positions allotted by dominant discourses, to enact multiple identities, and to remember who we have become, just for a moment.

Notes

Karin Willemse, PhD, obtained her doctorate in cultural anthropology from Leiden University, based on her dissertation entitled One Foot in Heaven: Narratives on Gender and Islam in Darfur, West-Sudan (Brill, 2007). She is Assistant Professor at the Erasmus School of History, Culture, and Communication in Rotterdam. She specializes in an analytical method of narrative analysis, “con/text analysis against the grain.” She was chair of the Netherlands Association for Gender and Feminist Anthropology (1997-2003), Fellow at NIAS (2005-2006 & 2007-2008) and is currently a member of the Academic Advisory Board of the Islam Research Project, a cooperative venture between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Leiden University. Her latest research projects, on which she worked with scholars from South Africa, Senegal, and Sudan, all focus on Africa and gender.