Articles

Life Stories and Mental Health:

The Role of Identification Processes in Theory and Interventions

The goal of this article is to explore the relations between narratives and mental health from a psychological perspective. We argue that a process of identification with personal experiences underlies narrative structures that are known to be related to mental health. Overidentification and underidentification are described as general processes underlying mental health problems. Gerontological insights in reminiscence and life review and cognitive psychological studies on autobiographical memories validate this claim. Practical applications in mental health care provide even further evidence for the role of identification processes in mental health and how they can be targeted in interventions.

1 Personality psychologists have a longstanding interest in the nature of individual differences. Over the past 25 years, this interest has been broadened to include individual differences in autobiographical storytelling (McAdams, 2008). An important question that has been raised from this perspective is how storytelling is related to individual differences in mental health. This question has also been asked in mental health care, where narrative therapy has developed over the past two decades. The narrative approach to personality and mental health differs from traditional approaches, because it focuses more strongly on subjective constructions of identities in their developmental and sociocultural context.

2 The goal of this article is to explore the relations between narratives and mental health from a psychological perspective. In order to better understand these relations, we will not only focus on narrative structures, but also on the processes of narration beyond these structures. With this focus on psychological processes of narration, we aim to contribute to the theme of this issue: Narratives on the Move.

3 In the first section of this article, we will develop theoretical notions on narration from insights in narrative psychology. Because remembering is a crucial aspect of storytelling, we will also explore gerontological research on reminiscence and life review, and cognitive psychological research on autobiographical memory. This exploration intends to validate the notions developed from narrative psychology, while it also provides more empirical results on mental health. In the second section of this article, we will carry out a similar exercise, but this time based on practical applications in mental health care, based on insights from narrative psychology, reminiscence and life review, and autobiographical memory.

Narratives and Mental Health

4 In this section, we will first reflect on our narrative approach and describe psychological studies on story structure. Next, we will go from structure to process and distinguish four basic types of identification processes in narration. In a first conclusion, we will tie these processes to broader sociocultural and developmental processes to further contextualize our approach.

5 As there are different understandings of what a narrative exactly is, it is important to reflect on our approach. We follow McAdams’ (2009) definition of narrative as a life story: “A life story is an internalized and evolving narrative of the self that incorporates the reconstructed past, perceived present, and anticipated future in order to provide a life with a sense of unity and purpose” (p. 10).

6 This definition provides a functionalist approach to narratives. Within specific social and cultural constellations, life stories function to provide personal experiences with a sense of meaning by putting them in a perspective of autobiographical time. As narratives of the self, life stories provide people with a personal identity that is incorporated in time, but also recognized by other people.

Narrative Structures

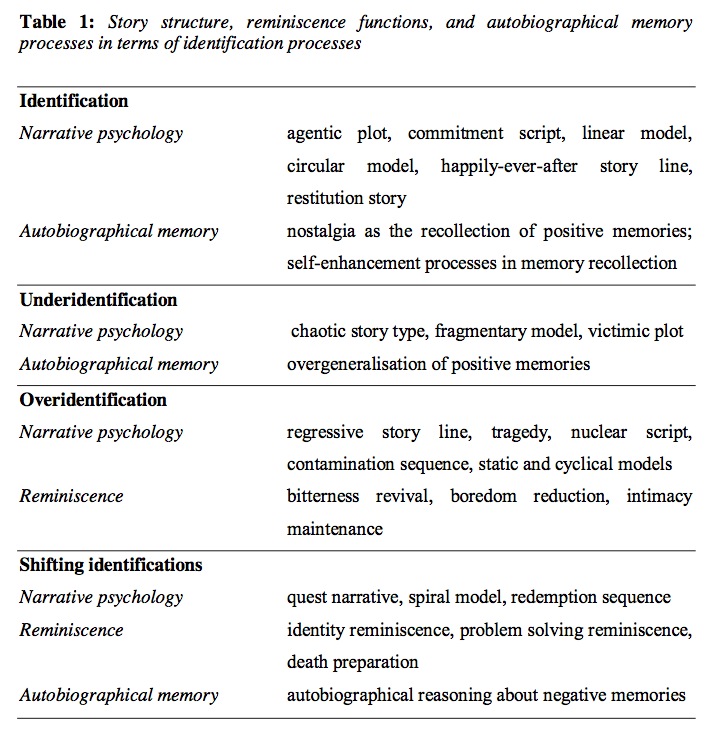

7 Narrative psychologists share an interest with other narrative researchers in the structure or plot of life stories. They have been inspired by the work of literary scientists like Kenneth Burke and Northrop Frye in their analyses of narrative plots. Psychologists have thereby taken up literary theory and applied it to storytelling in everyday life. They have mainly been interested in how individuals differ in the ways they structure their life stories. Psychological scholars have broadly focused on three related aspects of story structure: autobiographical time, personal affect, and authorship.

8 Some scholars focus mainly on the construction of autobiographical time in stories. Gergen and Gergen (1987) distinguish two basic elements in the narrative construction of time: progressive and regressive time lines. These can be found respectively in happily-ever-after plots and in tragic plots. They may also become mixed in more elaborate plots, like melodramatic or romantic plots. Brockmeier (2000) describes six narrative models of autobiographical time. The linear model incorporates a growth perspective across time. The circular model is likewise about growth, but it is more an interpretation after the fact. Cyclical and spiral models involve the recurrence of certain themes in a story. Whereas the cyclical model keeps coming back at the same theme in a similar way, the spiral model has a sense of direction to it. The static and fragmentary models are, in a sense, timeless. Static models incorporate stories that are frozen in time around a dramatic experience. Fragmentary models are characterized by a multitude of possibilities that are not tied together into a consistent story across time.

9 Other scholars have focused more on personal affect in relation to the plot. Silvan Tomkins (1987; see also Carlson, 1988) distinguished between commitment and nuclear scripts. A commitment script is woven around a predominance of positive affect that is related to a clear and rewarding life goal. In this kind of story, bad things can be overcome. A nuclear script, by contrast, encompasses much negative affect around more ambivalent life goals: it contains stories of good things gone bad. Building on these basic scripts, McAdams (2006) distinguished two types of narrative sequences about life episodes: redemption and contamination sequences. In a redemption sequence, an affectively negative experience leads to an emotionally positive outcome: the initial negative state is salvaged by the good that follows it. A contamination sequence is rather similar to a nuclear script, in that an emotionally positive experience becomes negative, as it is ruined or spoiled.

10 Finally, scholars have focused on issues related to authorship, that is, how much the author construes the protagonist of the story as being responsible for the actions in the story. Polkinghorne (1996) distinguished between victimic and agentic plots. In victimic plots, protagonists have lost power to change their lives, whereas in agentic plots protagonists actively help to shape their life, even in spite of problems. Arthur Frank (1995) distinguished between three types of illness narratives: restitution, chaos, and quest narratives. The restitution narrative is characterized by an important event, such as illness, that is overcome or cured so that the protagonist remains or becomes the same again. In the chaos narrative, the illness destroys the life of the protagonist. It is characterized as “speaking about oneself without being fully able to reflect on oneself” (p. 98). The quest narrative is characterized by the protagonist’s search for meaning and the idea that something can be learned or gained from the illness experience.

11 It is, however, important to go from a structural approach to a more processual approach, from a focus on “narrative” as “opus operatum” to “narration” as “modus operandi” (cf. Bourdieu, 1990; Westerhof & Voestermans, 1995). In the following section, we provide a psychological perspective on narration.

Identification Processes

12 Brian Schiff (2012, this issue) describes narrating as a process of making experiences present, while at the same time co-creating their meaning with other persons in a specific time and space. Distinguishing between experiences and their meaning makes clear that the two are not identical. Rather, narrating is a fundamental process of “selfing” (McAdams, 1996): phenomenal experiences—actions, thoughts, feelings, or strivings—are apprehended as more or less belonging to oneself. Using a spatial metaphor, one might say that narration places experiences as more or less close to one’s identity: this experience shows or does not show who I am. We will use the terms identification, overidentification, underidentification, and shifting identification to describe these variations in the fundamental process of selfing. These variations are tentatively related to variations in narrative structure (see Table 1).

13 First of all, there is the identification with personal experiences. The author identifies with these experiences as belonging to his or her own identity. There is thus a psychological proximity between experience and identity. From a perspective on autobiographical time, the plot leading to such an experience will consist of a progressive timeline or a linear model: i.e., it will represent growth from the past to the present experience. This growth may also be interpreted in retrospect, as in a circular model. With regard to affective quality, it can be characterized as a commitment script with a predominance of positive affect. Authorship is characterized by an agentic plot: the person is seen as the source of these experiences. Identification is indeed a matter of degree. This becomes clear when problems are encountered which can be overcome. People tend not to identify, but distance themselves, from such negative experiences in their lives in order to maintain their identity. This distancing process may underlie restitution stories about illnesses or commitment scripts in which problems are overcome. The identification process thus involves a balance between proximity and distance. Identity is created and recreated within existing storylines.

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 114 Second, narration may be characterized by underidentification with personal experiences. In these kinds of stories, persons find it difficult to identify with their experiences: there is an extreme distance between the two. Victimic plots in which protagonists are being overwhelmed by events and have lost power to effect change show that the author is not experiencing him- or herself as being part of the events. Chaotic story types, where illness shatters one’s identity, can be seen as the prototypes of such stories. The fragmentary autobiographical model would also be a story of underidentification, because existing identifications are not related to autobiographical time. Under-identification can thus be characterized by a lack of coherence. However, incoherence does not necessarily imply underidentification. In the theory of the dialogical self, stories are characterized by multiple I-positions which are not necessarily coherent among each other (Hermans & Kempen, 1993). Yet the I-positions as such present important identifications with personal experiences in certain times and places. Underidentification thus involves a process of strong distancing from experiences which makes it difficult to construct a story about a consistent and socially recognized identity. In the extreme case, there will be no story told: silence remains.

15 Third, stories may be characterized by overidentification. In these stories, identity is seen as defined by a particular personal experience: there is an extreme proximity between the two. These stories share the common elements of regressive story lines, nuclear scripts, contamination sequences, as well as static and cyclical models. Affectively negative events have resulted in a dramatic life change that came to absorb a person’s identity and obstruct the flow of autobiographical time. People may overidentify with a romanticized past when everything was better than it used to be, or they may solely identify with the negative experience: “I am my problem.” In either case, people tend to tell the same story over and over again, while there seems to be little room for alternative story lines.

16 Fourth, there are stories of shifting identifications. These stories are marked by a process of identity change that has been brought about by personal experiences. The quest narrative in patients, the spiral model of autobiographical time, as well as redemption sequences, describe such stories. The baseline is that something bad happened which resulted in a search for meaning ending in new identifications. Although theories of story structure have mainly focused on the case where something bad happened, shifting identities might also be found with regard to positive experiences that have changed one’s life. We speak of shifting identifications, rather than identification: although there is a balance between proximity and distance, there is also a process of identification with new meanings. In contrast to underidentification, there is proximity: even negative experiences do tell something about oneself, who is not their mere victim. In contrast to overidentification, there is also a certain distance: the experiences do not tell the whole story. The integration of new experiences in changing identities is therefore key in these kinds of stories. They are told with a certain openness and also involve the restorying of previous experiences from the perspective of a newly gained identity.

Identification in Time and Space

17 We have characterized narration as a process through which the relation between personal experiences and identity is construed. This process may result in different identifications which are marked by the proximity or distance between experiences and identity: identification, underidentification, overidentification, and shifting identification. We tentatively assumed that these processes underlie different narrative structures that are woven around autobiographical time, affective organization, and authorship. We acknowledge that these processes are ideal types which may be mixed during narration.

18 Although we described narration as a more individual-oriented identification process, it is important to realize that it is always contextualized in place and time. Narrative psychologists have relied on social constructionism to make it clear that narration is always a socially embedded process of construing a certain version of one’s personal experiences in a particular place (Gergen & Gergen, 1987). As a sociocultural process, identification can be seen as the way in which a person positions himself or herself vis-à-vis a certain interlocuting partner or a dominant discourse or ideology (Harré et al., 2010). Whereas the work of personality psychologists on story structure has focused more on big stories about life episodes or even life as a whole, identification through positioning would also provide a link to the small story approach (Sools, 2010).

19 With regard to time, narrative development has been related to lifespan theories of identity development. Habermas and Bluck (2000) have argued that the formation of identity in adolescence includes narrative processes by which people construct coherence in their lives and thereby forge narrative identities out of personal experiences. Later in life, a continuous re-reading and re-writing of one’s life story is carried out (Randall & McKim, 2008) which may result in changing or consolidating one’s identity (Westerhof, 2009, 2010). In some cases, however, these developmental processes may come to a halt. This has also been described as narrative foreclosure: the premature conviction that the story of one’s life is over (Freeman, 2000, 2011; Bohlmeijer et al., 2011).

20 The concept of identification in narratives resonates more specifically with processes distinguished in lifespan theories of identity (Erikson, 1959; Kroger, 2007; Marcia, 1993; Stephen, Fraser, & Marcia, 1992; Whitbourne, 1996). In these theories, processes of exploration, accommodation, and openness have been distinguished from processes of commitment, assimilation, and consolidation. The former processes can be seen as necessary prerequisites for shifting identifications, although a continuous reliance on these processes may result in underidentification. The latter processes are more supportive of identification, although an exclusive reliance on these processes may result in overidentification. A balance between the two is indeed often seen as the most benevolent for mental health (Marcia, 1993; Whitbourne, 1996).

21 Narration as an identification process is therefore always contextualized in place and time. We propose that within place and time, identification processes are also related to mental health. Identification and shifting identification will generally be related to a flourishing mental health, because they provide a balance in proximity and distance between experiences and identity. Underidentification and overidentification tend to be related to mental health problems, because distance or proximity prevail and flexibility is thereby lost. Some studies on story structures have indeed provided indirect evidence for this line of reasoning, e.g., persons who construe stories of growth and redemption experience higher levels of well-being (Bauer et al., 2005, 2008). In the following, we focus on research on remembering, which brings a further validation of the identification processes as well as more empirical results on their relation to mental health.

Remembering

22 In this section, we will describe two lines of research on remembering. Both lines of research make use of methodologies which differ from each other as well as from narrative inquiry. Research on reminiscence and life review stems from gerontology and has mainly been carried out with questionnaires asking for self-reports about remembering. Research on autobiographical memory stems from cognitive psychology and has worked mainly in an experimental paradigm. The exploration of these research lines can thus function as a triangulation of the idea of narration as identification.

Reminiscence and Life Review

23 Reminiscence refers to the recollection of memories, whereas life review also includes the evaluation of and meaning attributed to these memories (Bluck & Levine, 1998). Originally, reminiscence and life review were seen as activities which helped older people to come to terms with their past life in view of the impending end of life (Butler, 1963; Erikson, 1959). Later studies showed that reviewing one’s life was not done by all older adults, nor was it done solely by older adults. Nowadays, reminiscence and life review are seen as activities which occur throughout the adult lifespan, particularly in times of crisis and transitions (Pasupathi, Weeks, & Rice, 2006; Thorne, 2000; Webster & Gould, 2007; Webster, Bohlmeijer, & Westerhof, 2010).

24 Researchers have distinguished different types and functions of reminiscence (Webster, 1994, 2003; Wong & Watt, 1991). People do not only use reminiscence for death preparation, but also to discover or clarify who they are (identity function) or to remember past coping strategies to address current life challenges (problem solving). Furthermore, reminiscence has social functions to connect or reconnect to others (conversation) or to transmit past personal experiences to other people (teach/inform). Finally, reminiscence can be used to keep the memories of deceased persons alive (intimacy maintenance), to continuously recall negative experiences (bitterness revival), or to think back to the past to escape the present (boredom reduction).

25 Studies using self-report questionnaires have addressed which functions of reminiscence are related to mental health (Westerhof, Bohlmeijer, & Webster, 2010, provide an overview of previous studies). The reminiscence functions tend to split into three when it comes to their relation with mental health. Identity, problem solving, and to some extent, also death preparation are positively related to mental health (Cappeliez, O’Rourke, & Chaudhury, 2005; Cappeliez & O’Rourke 2006; O’Rourke, Cappeliez, & Claxton, 2010). These reminiscence functions make positive use of memories and tie them to one’s present self and life. Bitterness revival, boredom reduction, and to some extent, intimacy maintenance are negatively related to mental health (Cappeliez et al., 2005; Cappeliez & O’Rourke 2006; O’Rourke et al., 2010). Individuals using these forms of reminiscence appear to value the past, either as a result of a lack of meaning in the present (boredom reduction), a continued valuation of relationships with deceased persons (intimacy maintenance), or a continuous rumination about past negative events (bitterness revival). Social reminiscence is only indirectly related to mental health: it apparently makes a difference how memories are talked about in social situations (Cappeliez et al., 2005; Cappeliez & O’Rourke 2006; O’Rourke et al., 2010). Recent studies suggest that reminiscence is related to mental health, because it strengthens mastery, meaning in life, and goal management (Cappeliez & Robitaille, 2010; Korte et al., 2011; Korte, Westerhof, & Bohlmeijer, in press).

26 The functions of reminiscence are thereby close to the functions of autobiographical stories in providing a sense of unity and purpose in life. Reminiscence functions can also be interpreted in terms of identification processes in narration. Problem-solving reminiscence refers to a process where individuals identify with previous problem-solving strategies to cope with present-day problems. Identity reminiscence and death preparation contribute to the integration of meaning of both positive and negative memories. They are the prototypes of a life review in which memories are evaluated and balanced: identifications with positive experiences are maintained whereas identifications with negative experiences are provided with new meaning. They may thus be compared to the processes of identification and shifting identification in narration. By contrast, negative reminiscence functions are not characterized by evaluation and attribution of meaning. Bitterness revival refers to the obsessive rumination about things gone wrong in the past and can thus be characterized as overidentification. Boredom reduction and intimacy maintenance are both used to maintain identifications with the past. Insofar as they may prohibit new identifications or may be used to escape the present, they may even be interpreted in terms of overidentification. Interestingly, this adds a new dimension to overidentification, because it is characterized not by negative experiences, but by positive experiences from the past.

27 We conclude that studies on reminiscence and life review corroborate narration processes, while adding empirical evidence on the relation between identification and mental health as well as the possibility that overidentification can also occur for positive experiences.

Autobiographical Memories

28 Cognitive psychology has a long tradition of studying the functions of memory, but it has only in the last two decades focused on the unique, personal memories of an individual’s own life: autobiographical memories (Pillemer, 1998). Conway (2005; Conway & Pleydell-Pearce, 2000) sees autobiographical memories as the building blocks of one’s life story. He developed an intriguing theory about the self-memory system, which describes the dynamics between the conceptual story of one’s life and the episodic memories of specific events, which are often laden with sensory details. Episodic autobiographical memories are not simply retrieved from an archive of memories, but are actual reconstructions of the past. Memories are therefore not true or false in the sense that they are more or less exact representations of past events, but they are “true” or “false” in terms of being functional or dysfunctional in leading a good life in the present and near future (Bluck, 2009).

29 What do we know from this perspective on the relation between autobiographical memories and mental health? Studies on nostalgia have shown that the recollection of positive memories can be an effective antidote against negative moods (Wildschut et al., 2006). Recollecting specific positive autobiographical memories appears to be especially important. Studies on depressed persons have shown that they tend to overgeneralise their memories and have difficulties in retrieving the details of specific positive memories (Williams et al., 2007).

30 Furthermore, there appear to be interesting differences between memories of positive and negative events. Positive events from late adolescence and early adulthood are particularly well remembered, whereas negative events are not (Berntsen & Rubin, 2002). Affects attached to negative memories fade out more swiftly than those attached to positive memories (Ritchie et al., 2009). Negative memories seem to have occurred in a more distant past than positive memories (Wilson & Ross, 2003) and tend to be remembered from an outside, observer perspective (Berntsen & Rubin, 2006). Derogating the past can even be an important process in construing a positive view of oneself in the present (Wilson & Ross, 2003). Taken together, these findings point to a process of self-enhancement, i.e., the desire to maintain or improve one’s self-esteem.

31 The recollection of memories does not only include the retrieval of memories with all their associated characteristics, but also the evaluation and telling of them. In her studies on the development of autobiographical memory in children, Fivush (2008) found that styles of remembering may be more or less elaborate. A less elaborative remembering style focuses more on facts and concrete happenings, whereas more elaborate remembering focuses on context, emotions, explanations, and evaluations of what happened. The latter has also become known under the concept of autobiographical reasoning (e.g., McLean & Fournier, 2008). In terms of the self-memory system, autobiographical reasoning strengthens the link between episodic memories and their meaning at the conceptual level. Differences in autobiographical reasoning are important in attributing meaning to negative memories: people experience better well-being when they can accept regrets (Dijkstra & Barelds, 2008), resolve their regrets (Torges, Stewart, & Duncan, 2008), or adjust their perceptions of personal responsibility and control for regrets (Wrosch & Heckhausen, 2002). Integrative memories, i.e., those that connect a specific memory with a broader meaning, are also related to mental health (Blagov & Singer, 2004). Conversely, posttraumatic stress, with its vivid flashbacks of life-threatening situations, appears to be related to a lack of integration of specific negative memories with the conceptual level of life stories (Pillemer, 1998).

32 It can be concluded that although memories are about the past, they are reconstructed from the present. In this process, the link between recollecting specific experiences in the past as found in episodic memory with attributing meaning at the conceptual level of life stories plays an important role. Three dynamics between these levels are important for mental health: to relate specific positive memories to one’s life story, to enhance a positive view about oneself, and to connect negative memories to the level of life stories by processes of autobiographical reasoning.

33 These three processes in autobiographical memory relate to insights from narrative psychology about identification processes. Recollecting specific positive memories and relating them to one’s life story can be seen as a process of identification: the distance between the recollected experiences and one’s identity is diminished. When overgeneralisation takes place, it is difficult to identify with specific personal experiences. This can be seen as an aspect of underidentification, as there is nothing to identify with. The self-enhancing process involves an identification with positive events and distancing one’s identity from negative events. Finally, the process of autobiographical reasoning helps to attribute meaning to personal events and might thus be interpreted as a process of shifting identifications. We can conclude that studies on autobiographical memories corroborate the identification processes while adding the dimension of underidentification with positive memories. They also provide further empirical evidence for the linking of identification processes to mental health.

Identification and Remembering

34 We discussed two lines of research on remembering to provide further validation to the identification processes distinguished in narration. The importance of meaning-making processes which relate specific experiences to identity is corroborated. Processes of identification, underidentification, overidentification, and shifting identification could be distinguished in these lines of research (see Table 1). Interestingly, we also encountered underidentification processes and overidentification processes with regard to positive memories. Studies on reminiscence and autobiographical memories also provide empirical evidence on the relation of identification processes to mental health.

35 Each of the three streams of research (narrative psychology, reminiscence, autobiographical memory) has also been accompanied by interventions and therapeutic applications. We will focus now on insights from interventions to provide further validation of the relation between identification processes and mental health.

Therapeutic Applications

Narrative Therapy

36 White and Epston’s (1990) book, Narrative Ways to Therapeutic Ends, has become the classic treatise on narrative therapy. Clients tend to come to narrative therapy with problem-saturated stories (Payne, 2000). Such problem-saturated stories can become identities (e.g., I’ve always been a depressed person)and can therebyhave a negative influence on one’s mental health. Being grounded in social constructionist approaches, narrative therapists tend to see these stories not as truths, but as particular versions of the life of the client. The problem-saturated story is the story that is dominant in an individual’s life, but it is also often related to powerful dominant stories in society: e.g., stigmatization of mental illness. One of the goals of narrative therapy is to find an alternative, more satisfying, or preferred story.

37 There are basically two processes in narrative therapy: the deconstruction of the dominant story and the reconstruction of the alternative story. Externalizing the problem is the main process in the deconstruction of the dominant story. The goal is to see the problem no longer as self-defining, but as only part of a much broader story about oneself and one’s life. The alternative story is started by searching for unique outcomes: i.e., those personal experiences that are not part of, or even contradict, the dominant story line. The alternative story is then “thickened” by searching for more details and instances in different periods of life which confirm the alternative story so as to make it more vivid and complete. This reauthoring process involves two levels: the landscape of identity and the landscape of actions. On the one hand, the therapist continuously questions the meaning of specific actions: how do they indicate the more overarching personal values and intentions of the identity landscape? On the other hand, the therapist asks for more specific actions in the recent and distant past as well as in the future that are characteristic of the values and intentions found at the identity level.

38 In line with its social-constructionist approach, narrative therapy has mainly been studied with small-scale qualitative approaches (Etchison & Kleist, 2000; Riessman & Speedy, 2007). Case studies have provided evidence for the narrative processes at work and thereby validated theoretical descriptions of narrative therapy.

39 We conclude that narrative therapy can also be seen in terms of shifting identifications through which a new story is developed. Clients with an overidentification with experiences in problem-saturated stories are invited to explore other personal experiences that may serve as new identifications in an alternative story. The externalization process serves to distance one’s identity from the problematic experiences, whereas the “thickening” process serves to create proximity with other personal experiences. The shifting between action and identity landscapes strengthen this proximity. Interestingly, Singer and Blagov (2004) have pointed out that this shifting corresponds to shifting between the levels of episodic memories (similar to the action landscape) and the conceptual self-story (similar to the identity landscape) in terms of the self-memory system (Conway, 2005).

Reminiscence and Life Review Interventions

40 The concepts of reminiscence and life review are not just used to describe processes in the recollection of memories, but have also been used to describe psychological interventions (Westerhof et al., 2010). Such interventions have been part of (mental) health care for older persons for some 40 years. The use of reminiscence and life review in interventions and therapies for older adults is very widespread nowadays with many different settings, target groups, and activities.

41 Building on earlier distinctions between reminiscence and life review interventions (Bluck & Levine, 1998; Haight & Dias, 1992), we have proposed a three-fold classification of interventions that is based on reminiscence functions (Westerhof et al., 2010). Reminiscence interventions focus on the recollection of positive memories with the goal of enhancing well-being. They target mainly the social functions of reminiscence. The second kind of intervention is called life review. It addresses the integration of positive and negative memories with the goal of enhancing aspects of mental health, such as self-acceptance, mastery, and meaning in life. The reminiscence functions of identity construction and problem solving (and possibly death preparation) are stimulated. The third kind of intervention is life review therapy, which connects life review to other therapeutic interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (Watt & Cappeliez, 2000), creative therapy (Bohlmeijer et al., 2005), or narrative therapy (Bohlmeijer et al., 2008). The goal is to alleviate the symptoms of mental illness by reducing negative reminiscence functions, like bitterness revival.

42 During the past two decades, the effectiveness of interventions has been widely studied. Reviews (Lin, Dai, & Hwang 2005; Scogin et al., 2005) and meta-analyses (Bohlmeijer et al. 2007; Bohlmeijer, Smit, & Cuijpers, 2003; Hsieh and Wang, 2003; Pinquart, Duberstein, & Lyness, 2007) have shown that interventions are effective in improving wellbeing and alleviating depression. The evidence is stronger for life review than for reminiscence interventions. Recent studies have also shown that the combination of life review with therapy is effective in reducing depression (Korte et al., in press; Pot et al., 2010). Scogin et al. (2005) concluded that life review is an evidence-based treatment for late-life depression. Studies on processes involved in these interventions have found that an increase in personal meaning, mastery, and positive thoughts as well as a decline in negative reminiscence functions contribute to the decline in depressive symptoms in life review therapy (Korte, Cappeliez, Westerhof, & Bohlmeijer, 2012; Westerhof et al., 2010).

43 The different interventions based on reminiscence, life review, and life review therapy can again be interpreted in terms of different identification processes. Reminiscence is mainly directed towards the identification with positive memories about one’s own life: as Bluck and Levine (1998) argued, it is mainly focused on the consolidation of identity. Life review targets the evaluation and integration of positive and negative memories in the life story. It thereby contributes not only to identification with positive memories, but also to shifting identification with negative memories. Finally, life review therapy mainly targets negative reminiscence functions which are characterized by an overidentification with past memories. It thereby serves to induce changing views of oneself (Bluck & Levine, 1998) by opening up one’s life story for shifting identifications.

Autobiographical Memory

44 The more fundamental research on autobiographical memories conducted from cognitive psychology has resulted in fewer interventions. Two types of interventions have been studied reasonably well.

45 Based on the literature on overgeneralization of autobiographical memory in depression, interventions have been developed which target the retrieval of specific positive memories. Two studies provided evidence that memory specificity can be improved and depressive complaints can be alleviated by such an intervention (Gonçalves et al., 2009; Serrano et al., 2004).

46 Narrative exposure therapy is another intervention based on research on autobiographical memory. It is being used in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. The treatment involves emotional exposure to the memories of traumatic events and the reorganization of these memories into a coherent autobiographical story (Schauer et al., 2005). A recent review of treatment trials has shown that this therapy is superior in reducing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder compared with other therapeutic approaches (Robjant & Fazel, 2010).

47 In terms of our notions on narration as an identification process, the interventions for increasing autobiographical memory specificity aim at counteracting the tendency of depressed persons to underidentify with specific personal memories. Narrative exposure therapy, by contrast, focuses on autobiographical reasoning and thereby restoring a process of identification.

Identification in Therapy

48 We have seen that narration can be described in terms of identification processes with personal experiences. This was further validated by theoretical and empirical research on reminiscence and autobiographical memory. Overall, there is evidence that identification and shifting identification are positively related to mental health, whereas underidentification and overidentification are negatively related to mental health. Further validation of this perspective comes from therapeutic applications. Narrative therapy focuses on overidentification in dominant problem-saturated stories and renewed identification in alternative stories, thereby continuously shifting between the levels of specific events and identity. Interventions based on reminiscence and life review, including life review therapy, target different processes: identification in reminiscence, identification and shifting identification in life review, and overidentification and shifting identification in life review therapy. Therapy based on autobiographical memory targets underidentification with specific positive memories or identification with traumatic memories.

49 Interventions that are therapeutic in that they want to induce self-change all have in common that they try to stimulate a process of shifting identifications. This commonality derives from the fact that identification processes have often become problematic in people who seek therapeutic help. However, reminiscence interventions and the recall of specific autobiographical memories show that a positive identification with past experiences can also be a valuable process in interventions. Different approaches can thus learn from each other in how they target different identification processes. This is also true in terms of their scientific evaluation. Whereas studies of narrative therapy have mainly addressed therapeutic processes using qualitative methods, reminiscence, life review, and autobiographical memory interventions have mainly been studied in effectiveness trials.

Towards a Narrative Mental Health Care

50 We have argued that it is important to go from narrative structures as opus operatum to narration processes as modus operandi. We have seen that differences in identification are important aspects of narration from a psychological perspective. Different identification processes might not only account for differences in narrative structures, but also for different ways of reminiscing and reviewing one’s life as well as for autobiographical reasoning processes which relate episodic memories to conceptual life stories. Finally, identification processes are targeted in different ways in interventions based on narrative psychology and remembering. As long as identification remains a flexible process of creating distance and proximity between personal experiences and identity, mental health will be flourishing. Mental health may be impaired when this flexible process stops, either by a distance that makes personal experiences unrelated to identity or by a proximity that makes a particular personal experience be the sole defining feature of identity. These identification processes can be further contextualized in space and time, although this was not the focus of our paper.

51 How can these insights in narration be applied to mental health care? Over the past decades, mental health care has undergone a process of strong professionalization. Although psychological practice has become more strongly evidence-based, more transparent, and more controllable, it has also stepped more and more into a medical model and an “illness ideology” (Maddux, 2009, p. 62). Recovery is basically seen as the alleviation of symptoms of mental disorders. From a narrative perspective, the story of the patient is thereby reduced to his or her complaints. The dominant story in mental health care is the restitution narrative: the symptoms have to be treated and overcome.

52 Bohlmeijer et al. (2011) have argued that health care can be enriched by incorporating narrative perspectives. Narrative mental health care may include even more than the kind of interventions that we discussed in this article. Stories can be granted a more important role during the intake and diagnostic phase, besides psychiatric interviews and tests. Recordkeeping might involve narratives about the therapy and how it affects daily life from the clients’ point of view as well as the notes on progress from the therapists’ point of view. Clients’ stories might also play an important role in therapy evaluation, complementing the routine outcome-monitoring in contemporary practice. Hence, narrative mental health care does not leave the stories unexamined, but explicitly uses and studies them, thereby giving clients a stronger voice in the process.

Gerben J. Westerhof, PhD, is Associate Professor in Psychology at the University of Twente, the Netherlands. He directs the Dutch Life Story Lab (www.utwente.nl/lifestorylab) that aims to contribute toward a person-centered approach in mental health care. His work takes place at the intersections of narrative, positive, and lifespan developmental psychology. He is the co-author of numerous articles in these fields and among others, co-editor of Ageing and Society, the first European textbook on gerontology.

Ernst Bohlmeijer, PhD, is professor of mental health promotion at Twente University in the Netherlands. He has a special interest in the development and evaluation of person‐based and narrative interventions in mental health care. He is co‐editor of the recently published book Storying Later Life (Oxford, 2011) with Gary Kenyon and Bill Randall. In 2009, he was a co-recipient of the Gerontological Society of America’s award for Theoretical Developments in Social Gerontology.