Glorious Tragedy: Newfoundland's Cultural Memory of the Attack at Beaumont Hamel, 1916-1925

Robert J. HardingDalhousie University

1 THE FIRST OF JULY is a day of dual significance for Newfoundlanders. As Canada Day, it is a celebration of the dominion's birth and development since 1867. In Newfoundland and Labrador, the day is also commemorated as the anniversary of the Newfoundland Regiment's costliest engagement during World War I. For those who observe it, Memorial Day is a sombre occasion which recalls this war as a tragedy for Newfoundland, symbolized by the Regiment's slaughter at Beaumont Hamel, France, on 1 July 1916.

2 The attack at Beaumont Hamel was depicted differently in the years immediately following the war. Newfoundland was then a dominion, Canada was an imperial sister, and politicians, clergymen, and newspaper editors offered Newfoundlanders a cultural memory of the conflict that was built upon a triumphant image of Beaumont Hamel. Newfoundland's war myth exhibited selectively romantic tendencies similar to those first noted by Paul Fussell in The Great War and Modern Memory.1 Jonathan Vance has since observed that Canadians also developed a cultural memory which "gave short shrift to the failures and disappointments of the war."2 Numerous scholars have identified cultural memory as a dynamic social mechanism used by a society to remember an experience common to all its members, and to aid that society in defining and justifying itself.3 Beaumont Hamel served as such a mechanism between 1916 and 1925. By constructing a triumphant memory based upon selectivity, optimism, and conjured romanticism, local mythmakers hoped to offer grieving and bereaved Newfoundlanders an inspiring and noble message which rationalized their losses.

3 This 'Beaumont Hamel-centric' Great War myth was disseminated by the state, the church, and the press through remembrance ceremonies, war literature, and commemorative bronze and granite. A highly selective, inspirational cultural memory of the attack rapidly emerged, emphasizing bravery, determination, imperial loyalty, Christian devotion, and immortal achievement. However, each medium added its own distinguishing marks to the myth. Immediate reactions mythologized Beaumont Hamel in order to combat widespread grief. Rather than lamenting an advance that had gone horribly wrong, military and state officials, and the press transformed the failed assault into a heroic and inspiring event. Memorial Day ceremonies suggested that World War I had been a formative national undertaking, most appropriately symbolized by Beaumont Hamel. Through annual ritualizing, consolatory rhetoric was quickly transformed into the language of civic inspiration. A volume of historical literature also appeared in this period which, rather than acting as an alternative, served to reinforce the myth. The construction of the Beaumont Hamel Memorial Park was permanent confirmation that the advance was the symbolic pillar upon which Newfoundland's cultural memory of the conflict was built. Through consideration of the major mythic themes promoted by these mediums, this paper will show that remembering World War I in Newfoundland between 1916 and 1925 had everything to do with pride and achievement, while notions of tragedy and loss merited little, if any, attention. Newfoundland was not the only country which sought to rationalize this war through avenues of remembrance, and comparisons are made with Great Britain, Canada, and Australia. Newfoundland's cultural memory of this war was largely rooted in contemporary international trends.

4 Newfoundland's part in World War I and its impact on the country's history has been considered by a number of scholars. Recent work by historians David R. Facey-Crowther and P. Whitney Lackenbauer has focused on how the conflict entered Newfoundland's cultural memory during the postwar years.4 Although the experience of the Newfoundland Regiment at Beaumont Hamel has been thoroughly documented, the attack's passage into the realm of cultural memory has not been properly assessed.5

5 When war was declared on 4 August 1914, the Newfoundland government immediately assured Britain that it would provide 500 soldiers, and journalists and clergymen used patriotic rhetoric to encourage young men to volunteer. There were those, most notably William Coaker, who felt that Newfoundland should focus on training recruits for the Royal Naval Reserve. However, the predominant opinion was that the conflict would be settled on land, and Sir Edward Morris's government created the Newfoundland Patriotic Association [NPA] to raise and train a land-based battalion.6 There was an immediate and enthusiastic response, especially in St. John's. On 4 October 1914, the SS Florizel left St. John's with a force of 537 hastily trained and ill-equipped soldiers, "The First Five Hundred," or "The Blue Puttees."7

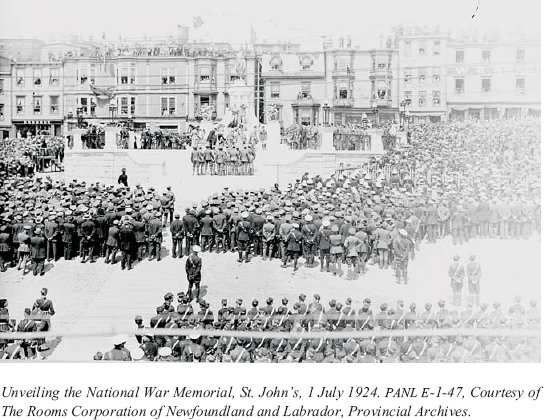

Unveiling the National War Memorial, St. John's, 1 July 1924. PANL E-1-47, Courtesy of The Rooms Corporation of Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Archives.

Display large image of Figure 1

6 This First Battalion of the Newfoundland Regiment trained in England and Egypt for several months and was reinforced by additional recruits before joining the British 29th Division on the Gallipoli Peninsula in September 1915.8 By the time the battalion withdrew in January 1916, it had suffered 760 casualties; only 170 soldiers remained to answer the roll call.9 The battered unit spent the winter months of 1916 being rebuilt and trained under its new commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur L. Hadow.10 In March, the 29th Division moved to the Western Front in France where the Newfoundlanders underwent further training near Louvencourt, while periodically entering the line to repair trenches in preparation for the Allies' next offensive.11

7 Allied commanders had spent the winter planning that offensive, scheduled to commence on 29 June 1916. By that time 500,000 men of the British 4th Army (including the 29th Division) were assembled along an eighteen-mile front between the Ancre and Somme rivers, the southern end linking with the eight-mile front of the French 6th Army.12 British and French commanders were confident that the offensive, preceded by a week-long artillery bombardment from 1,400 guns, would provide the necessary breakthrough. On 26 June, 29th Division commander General Henry Beauvoir de Lisle gave a speech to the men of the Newfoundland Regiment in which he all but promised victory in the upcoming offensive.13 These same hopes permeated the battalion's ranks, and are evident in the writings of Private Frank 'Mayo' Lind and Lieutenant Owen Steele.14 Optimism ran high that the Somme offensive would be an Allied victory and a glorious battlefield debut for the Newfoundland Regiment.

8 The highly anticipated moment came on 1 July 1916. At 7:28 a.m. several mines were blown along the Somme front, and at 7:30 a.m. the infantry advance began.15 Substantial gains were made by several divisions in the south, but most units were met by a crippling hail of German artillery and machine-gun fire. During the first hour, almost half of the 66,000 Allied troops in the attack were killed or wounded, usually before getting past their own barbed wire.16 The 29th Division was particularly affected. The 86th and 87th Brigades suffered overwhelming casualties without coming close to their objectives, the first and second lines of the German trenches. The Newfoundland Regiment, a part of the 88th Brigade, received revised orders from General de Lisle at 8:45 a.m., requiring an immediate advance on the German front lines, and hastily prepared for an assault for which it had not trained.17

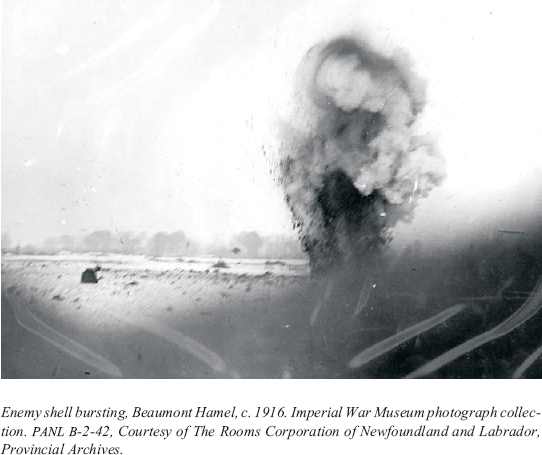

Enemy shell bursting, Beaumont Hamel, c. 1916. Imperial War Museum photograph collection. PANL B-2-42, Courtesy of The Rooms Corporation of Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Archives.

Display large image of Figure 2

9 The 800 Newfoundlanders advanced at 9:15 a.m. without support from the First Essex Regiment. They had to pass through several lines of British barbed wire and trenches before entering the downhill slope of 'no man's land'which would offer a clear view of the German barbed wire and front lines.18 Most of the 800 were wounded or dead before reaching their own front line, and the few that made it to the German wire were shot down. Not a single Newfoundlander fired a shot, let alone inflicted a casualty. Within a half-hour the battalion's advance had been shattered.19

10 The attack was called off by early afternoon. Of the more than 100,000 soldiers who had advanced against the German trenches, 57,000 were casualties, including 19,000 dead. The Germans suffered about 8,000 casualties.20 The

11 Newfoundlanders had been dealt one of the most severe blows during the assault. In his report that evening Lt.-Col. Hadow noted the brutality of the defeat: 233 dead, 477 wounded or missing, and only 68 answered the roll call.21

12 British commanders probably realized the futility of the attack as they watched their soldiers being mown down. However, unlike historians, battalion commanders and generals were not primarily concerned with assessing the merits and faults of their strategies and tactics.22 For them, finding purpose was more important than laying blame. They were fighting a war they intended to win, and, if they had been defeated, it was vital to at least suggest that their soldiers had died for good reason.23 There had to be something for the British command to build on, there had to be something inspiring about Beaumont Hamel which could be used in Newfoundland to mitigate the shock.

13 The Newfoundland press played a significant role in conveying news of the war to the public, usually in the form of censored military reports, in a sanguine and upbeat tone. Indeed, politicians and military authorities expected local papers to present war news in the most favourable light possible.24 This was not unique to Newfoundland. Jeffrey Keshen and Jonathan Vance have shown that the Canadian military effort was always portrayed by Canadian newspapers in a positive and reassuring light.25 Stephen Garton and Ken Inglis note that in the immediate aftermath of appalling losses in the Gallipoli landing of 25 April 1915, the Australian press quickly translated that failed assault into Australia's defining wartime moment, and the 10,000 Anzacs who died there were venerated as national heroes.26 Editorial rhetoric in Newfoundland similarly tried to lessen the negative impact of Beaumont Hamel by describing it as a heroic national sacrifice. In so doing, the press laid out the basic thematic elements that would shape the country's Great War myth.

14 Initial reports from the Somme were vague and highly optimistic. Major newspapers such as The Evening Telegram, The Daily News, and The Weekly Advocate declared that a major British victory was imminent.27 However, casualty lists began flooding the newspapers a week after the offensive started. On 8 July the Telegram reported 230 casualties from the Newfoundland Regiment's attack at Beaumont Hamel. By 22 July the figure had risen to 524, including 44 killed.28 One week later the Telegram published Lt.-Col. Hadow's official report, which revealed that 110 soldiers were dead, 495 wounded, and 115 missing. Hadow confirmed what newspapers had reluctantly been hinting at — the Regiment had suffered a frighteningly high casualty rate at Beaumont Hamel.29 The fact that Newfoundland was a small country comprised of many tiny, close-knit communities made it difficult to downplay the losses.30 The Western Star observed that it was vital for casualty lists to be released quickly because "Newfoundland is different from other countries. Here we seem to know each other. This makes the grief more widely felt."31

15 The official and press reaction was to mitigate the burden of grief by suggesting that the Newfoundland Regiment had accomplished something noble at Beaumont Hamel. The Daily News translated military defeat into a virtuous sacrifice offered in the name of imperial loyalty and Christian devotion:The price of Freedom is paid in tears, and the maintenance of liberty in the blood of its defenders. Today all Newfoundland is in sorrow, but with sorrow is mingled gratitude and pride.... It was Patriotism in its purity, and manhood in its perfection which brought the answer to the call of the Motherland. Newfoundland's response is Newfoundland's glory, and though today we bow in sorrow, and though hearts are breaking, and on some homes a pall of almost impenetrable darkness has settled, yet the silver gleam is there, for who shall say that the young Knights have not achieved in their quest for the Holy Grail. They have done their duty to God and man. They have withheld not themselves in the service of humanity. For some of them the fight is over. They rest from their labours, and their works do follow them.32 The battalion's slaughter was quickly transformed — this had been a loyal defence of the British Empire by Christian knights engaged in a modern crusade.

16 In so depicting Beaumont Hamel, however, the press was also trying to encourage greater support for the war effort. By 1916, a general improvement in the Newfoundland economy was hurting recruitment, and increasing numbers of men chose to work at home rather than enlist for service.33 Yet officials wanted to reconstruct the Regiment, fearing that the British War Office would remove it from the line.34

17 One way to stimulate recruitment and popular support was to portray the engagement as a challenge to the collective Newfoundland will. The Telegram hailed Beaumont Hamel for providing a new standard of discipline and courage to which future Newfoundland soldiers should aspire:For we had not yet known the bitter experiences of war which more than anything else has steeled the hearts and fixed the resolve of the rest of the empire. We have had it now. The glorious 1st of July united all Newfoundland in pride and sorrow; the memory of it will unite us in the steadfast resolutions which we have today recorded.35 Mourning was not the most appropriate way to honour the dead — continuing the fight in their place was. Beaumont Hamel therefore became a rallying point around which Newfoundlanders could re-muster and push forward with the war effort.

18 Words of praise from British military commanders gave the romantic presentation of Beaumont Hamel a heightened degree of legitimacy. Such statements appeared in the Telegram, The Daily News, The Weekly Advocate, and The St. John's Daily Mail during July and August.36 The famous comments of General Aylmer Hunter-Weston, commander of the British 4th Army's VIII Corps, appeared in The Weekly Advocate:That battalion (the Newfoundland Regiment) covered itself with glory on the 1st of July by the magnificent way in which it carried out the attack entrusted to it.... There were no waverers, no stragglers, and not a man looked back. It was a magnificent display of trained and disciplined valour, and its assault only failed of success because dead men can advance no further.37 The highest praise came from Field Marshal Douglas Haig, Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force, who informed Governor Davidson that "Newfoundland may well feel proud of her sons. The heroism and devotion to duty they displayed on 1st July has never been surpassed.... Their efforts contributed to our success, and their example will live."38 Such statements acknowledged the terrible losses suffered by the battalion, but, more importantly, they encouraged Newfoundlanders to recall Beaumont Hamel as a heroic moment that merited proud remembrance.

19 Several soldiers' accounts which appeared during July suggested that even in the trenches the advance was perceived as a gallant attack deserving national acclaim and thus provided further reinforcement for the mythic memory quickly taking shape.39 A letter from Private Bert Ellis portrayed Beaumont Hamel as a deadly killing field. However, he wrote, the battalion had conducted itself in a honourable and disciplined manner: "Our boys acted throughout like heroes. They went up on top singing just as if they were going on a march instead of facing death.... But our boys showed no fear."40 Another letter suggested that the Newfoundlanders' advance had beenan impossible job, so much so that we never had one chance in a million of doing anything.... I do not think there were any orders carried out at such a great sacrifice or so gloriously before in the annals of the British Army.... You may tell the people at home that Newfoundland may be proud of the Regiment. It was something to live and die for to be in that charge.41 Such accounts filled in the gaps left by official reports, while retaining the same assurances of a brave and memorable effort. By describing rather than simply noting the tremendous odds which faced the battalion on 1 July 1916, soldiers elevated the accomplishments of their battalion beyond the level of official, politically motivated rhetoric into the realm of authentic experience, making their advance appear even more dignified. Here was first-hand evidence that honour and pride were to be found in the blood-stained mud of Beaumont Hamel.

20 By August 1916 the press had established that Beaumont Hamel had been a great achievement by the Newfoundland Regiment, and this became the foundation for Newfoundland's 'Beaumont Hamel-centric' Great War myth. Editorials, military appraisals, and soldiers' letters reinforced and contributed to the rapid construction of a consensus which sought to inspire Newfoundlanders to harden their hearts against grief and despair. What makes these commentaries interesting is the manner in which selective realities were used to enhance mythic assertions. Editors, officers, and soldiers did not hesitate to confirm the high price paid by their countrymen at Beaumont Hamel, and they proclaimed the accomplishment of mythic feats there. Newfoundland had enthusiastically answered the Mother Country's call to arms in 1914, and officials did not want that initial enthusiasm to wane. Beaumont Hamel represented the cornerstone of a new Newfoundland heritage which, the press argued, was enhanced and made more inspiring by the severe price paid there. The engagement was transformed into a mythic event that could enrich Newfoundland's cultural fibre; and it was the responsibility of civilians to see that their country's new heritage was fittingly preserved and cultivated.

21 The spirit of the patriotic press editorials of July and August 1916 manifested itself in the rituals and rhetoric of Memorial Day. This annual ceremony reaffirmed the mythic themes first attached to Beaumont Hamel in 1916, and confirmed that engagement as the embodiment of Newfoundland's Great War myth.42 Memorial Day involved civilians in the mythmaking process by suggesting how they could best honour the dead soldiers outside the commemorative sphere. The event reinforced a sense of public duty, which official addresses and newspaper editorials suggested would be most adequately expressed through material aid to veterans and bereaved families. Beaumont Hamel would inspire Newfoundlanders to preserve and transmit a hard-earned heritage to future generations. Memorial Day rituals instructed Newfoundlanders how to commemorate World War I, and ceremonial language, which glorified Beaumont Hamel specifically, reminded them how best to honour the heroic soldiers who had fought and died.43

22 Remembrance ceremonies became customary in the countries which had participated in World War I. Ritualized commemoration is a social mechanism which ensures public endorsement of a given cultural memory, and provides an opportunity for the public to express its acceptance.44 Remembrance ceremonies also allowed the bereaved to formally cope with loss.45 This was certainly the case in Britain, while Australian soldiers were honoured on Anzac Day as the nation's finest youth who had performed heroic feats of national relevance.46 Each country had distinct commemorative ceremonies, but all were concerned to relay the supposed magnitude and impressiveness of soldiers' wartime service to the civilians who attended. Newfoundland was no exception.

23 The first Memorial Day ceremony was organized in St. John's by the NPA on 1 July 1917.47 The Daily News urged Newfoundlanders to commemorate the anniversary because it honoured a day when "there was written into the annals of this country by its noble and gallant sons, deeds of heroism and unfaltering devotion to duty that will ever be cherished as a glorious memory and handed down to generations yet to come as a priceless heritage."48 A year later, legislation officially established 1 July as Memorial Day, Newfoundland's official day of remembrance.49 By 1919 a standard Memorial Day programme, organized by the Great War Veterans'Association of Newfoundland [GWVA],50 had been established. That year, veterans and civic brigades paraded to their various churches for commemorative services, before assembling with civilian spectators for a state ceremony in Bannerman Park, next to the Colonial Building. Commemorative wreaths were laid around a temporary memorial cross. Governor Sir Alexander Harris gave a patriotic and optimistic address, and the ceremony concluded with the playing of "The Last Post" and a three-gun salute.51 With a few slight exceptions and alterations, this became the standard order of proceedings for Memorial Day services in St. John's, and by the early 1920s this programme was widely followed in communities across the island.52

24 Memorial Day organizers and speakers developed a dynamic 'Beaumont Hamel-centric' symbolism which they hoped would preserve the attack's — and the war's — cultural resonance. Newfoundland paid a relatively high price for serving the British Empire, and its mythmakers reminded civilians what four years of war had meant for their country — 12,000 out of a population of 250,000 had served, and nearly 1,600 had been killed.53 Memorial Day provided the mythmakers with the ideal channel through which to transmit their commemorative answer.

25 Speakers asserted that through their willing sacrifice at Beaumont Hamel, Newfoundland's soldiers had shown their kinsmen that the cost of freedom was both high and rewarding. During his 1920 Memorial Day sermon at the Anglican Cathedral in St. John's, the Reverend Canon Jeeves referred to the battalion's sacrifice as "the message from Beaumont Hamel. 'Son, Remember.'This is what comes from Paradise. What you enjoy is only yours today, because they laid down their lives on the National Altar."54 Dying for their country on 1 July 1916 thus enabled Newfoundland soldiers to achieve immortality. Vance notes that Canada's dead soldiers, like Newfoundland's, were also reinvented as saviours who had achieved eternal life by sacrificing themselves during the conflict.55 During the 1923 St. John's Memorial Day ceremony Governor Sir William Allardyce suggested that the fallen of Beaumont Hamel "may not be with us in the flesh, but they are nevertheless with us. Their influence cannot die, it is indestructible; their heroism and their valour cannot perish, for they were heaven sent and imperishable."56 Through Memorial Day services, Newfoundland's dead soldiers had new life breathed into them.

26 Commemorative rhetoric also emphasized that the heroic soldiers could live on in a tangible and practical way, as was the case in Britain.57 On Memorial Day, politicians, clergy, and veterans suggested that the noble traits of Newfoundland's fallen at Beaumont Hamel could be adopted by any civilian, young or old, and could bond Newfoundlanders together as a nation. Civilians were urged:Hold fast to those principles of truth, honesty, purity and manhood and you will be a perfect citizen, you will be doing more good for your country than ... a hero who dies for his country and her cause and be worthy of praise and renown; he on the other hand deserves an imperishable crown who by the observance of her laws by his industry and integrity lives and gives her the service of life.58 The soldiers of the Newfoundland Regiment had established a legacy at Beaumont Hamel that many believed was vital to their nation's culture, and it fell to civilians to see that that spirit of selflessness, patriotism, and devotion would endure beyond the battlefields of Europe.

27 Civilians were also urged to imitate the selflessness of Newfoundland's war heroes through material assistance to veterans and bereaved families.59 A Telegram editorial suggested that "Our repayment to them is not to be measured by the outward and visible deed. Let it be then ours to keep faith, and to do all that we can for the ones who are left."60 Bereaved families had been left with a "heritage which we will do not to neglect. That heritage is the care of those whom they left behind: those who were dependent upon them, and are now the first lien on the Dominion finances."61 A public appeal in the Telegram asked, "How sacred these two words have become to us, haven't they? What lies underneath these words? — blood, unselfishness, anguish."62 Memorial Day reminded the public of their civic duty to those most damaged by World War I, while Beaumont Hamel was the event which should motivate them to fulfil it.

28 Memorial Day also suggested that civilians were responsible for transmitting the mythic legacy of Beaumont Hamel to future generations. Efforts were made to ensure that children attended Memorial Day observances. The organizers of the 1918 St. John's ceremony hoped to have all relatives of city soldiers and veterans under the age of fourteen in attendance, and the Women's Patriotic Association [WPA] provided children's entertainment.63 The GWVA urged people to bring their children to the Memorial Day services as "[i]t is to the younger generation that we look to see that the memory of the Boys who gave their lives in the War is not forgotten."64 Five years later, a 1923 Telegram Memorial Day editorial identified the noble traits which Beaumont Hamel's fallen had transmitted to Newfoundlanders, while reminding readers that "[w]e must likewise hand down to our children and our children's children, as their most precious treasure and their most powerful inspiration, that same spirit of self-sacrifice which was possessed by all those whose memory we commemorate today, who, when duty called, fearlessly and unhesitatingly obeyed the summons."65 Two years later The Daily News commented that "July 1st, 1916, was a day that Newfoundlanders of the present generation can never wholly forget, and one which, so long as Newfoundland endures, will be held in honour by the generations that shall be."66 As the Memorial Day message had to survive beyond the generation which had experienced World War I, commemoration became a civic obligation for the island's youth.

29 Newfoundland's mythmakers may have promoted Memorial Day as an event that could motivate higher levels of social cohesion and civic pride, but it did not guarantee domestic political or economic stability. After the National Government collapsed in May 1919, politics became confused and chaotic. While civilians gathered annually to listen to patriotic rhetoric about national unity and imperial pride, their country went through six different ministries between 1919 and 1925, and a high level of government corruption was exposed by the 1924 Hollis Walker enquiry. At the same time, a harsh postwar economic climate saw Newfoundland's economy plummet dramatically from its prosperous wartime levels, while the public debt rose inexorably.67 Within this context, Memorial Day speeches and editorials offered the example of Beaumont Hamel's fallen to civilians in the hope that they would apply the same bravery and determination to their own obstacles.

30 Through the efforts of state, church, the GWVA, and the press, Memorial Day offered a highly ritualized and mythologized 'Beaumont Hamel-centric' memory of World War I to the Newfoundland public to ensure that their war dead lived on. Because Beaumont Hamel became mythologized so quickly, mythmakers could consolidate the noble elements they had extracted from the battle into a commemorative package which Newfoundlanders could use to repay the debt which they owed their dead soldiers and veterans. Maurice Halbwachs, James Fentress, and Chris Wickham have noted that memory can only be sustained through direct efforts to adapt it to changing social contexts.68 From this perspective, Memorial Day was the point of intersection where mythic assertions about the noble traits of dead soldiers became tangible elements that Newfoundland civilians were responsible for using to better their society. Remembrance ceremonies offered further validity to the mythic interpretation of Beaumont Hamel, while informing commemorative audiences that a cultural memory born under dire circumstances could aid a country entering dire straits.

31 Memorial Day was not the only way idealistic notions about the Newfoundland Regiment's advance at Beaumont Hamel were disseminated. Accounts of the engagement suggested that commemorative myths were rooted in actual fact.

32 Through emphasis on the overwhelming odds the battalion faced, and the identification of positive results, such works suggested that the battalion had actually achieved a plausible victory at Beaumont Hamel. To this end, writers produced highly selective accounts which avoided anything that could have threatened the mythic image. Fussell and Vance note that British and Canadian war-based literature recalled the conflict through narrative structures which, like Newfoundland war literature, offered mythic depictions of the conflict.69 In this period, writing about World War I was not about critical assessment; it was about persuading Newfoundlanders that the conflict had been a constructive national endeavour and that Beaumont Hamel was the country's defining wartime moment.

33 The terrain at Beaumont Hamel was presented as the first obstacle to confront the Newfoundland Regiment. The December 1917 edition of The Times History and Encyclopedia of the War included a chapter70 informing readers that the Newfoundlanders had to cross an open valley, which made them a clear and easy target, before they could even begin their attack. The battalion had to advance approximately 600 to 800 metres before reaching the German trenches, andthe way over this long distance was by no means clear. Lines had been cut through our own wires through which the troops might move, but those gaps were not nearly sufficient in number. The enemy knew all of these lanes and had their machine guns playing directly over them. There was a slight dip in the ground shortly after leaving our trenches, about three or four feet deep. The German machine guns had thus an admirable line of sight towards which they could sweep their fire, making the passage impossible.71 Then once it began, the advance was hindered by war-torn terrain. Published in 1921, Richard Cramm's The First Five Hundred was the first detailed treatment of Newfoundland's war effort. A politician and lawyer,72 he described a battlefield that presented many obstacles:The ground over which they [the Newfoundland Regiment] had to advance could scarcely be more difficult. It formed a gradual descent, which rendered our troops completely exposed. It contained enormous quarries and excavations in which large numbers of the enemy could remain concealed, almost immune from shell-fire, and ready to rush out and attack our men in the rear. Although the bombardment from the British guns was terrific it had comparatively little effect in lessening this danger.73 Physical obstacles guaranteed that the Newfoundlanders' advance would be hard pressed to succeed, and writers suggested that the battlefield served as an ally to the Germans, thus leaving the battalion seriously disadvantaged once it began its assault.

34 If the battlefield slowed the Newfoundlanders, it was the overwhelming volume and ferocity of the German resistance that broke their advance. In "Newfoundland's Heroic Part in the War" (which appeared in October 1916 editions of both The Cadet74 and Great War), F.A. McKenzie suggested that the Newfoundlanders bore the full brunt of the German fire during their advance at Beaumont Hamel.75 When they began their assault, the Germansmet our men with a withering fire before which none could live.... Success was impossible ... The whole thing was over so quickly that it seemed impossible that in a few minutes a gallant regiment should thus have been wiped out.76 Henry F. Shortis also emphasized the Germans' unrelenting fire in "Newfoundlanders in Picardy" in the October 1916 Newfoundland Quarterly.77 According to The Times account, once the British artillery bombardment ceased, "the German machine gunners poured out from their dugouts" and, when the Newfoundland Regiment advanced, "they were mown down in heaps."78 Thus the battalion's attack at Beaumont Hamel had not failed as a result of tactical errors — it had been stopped by the overpowering and skilful resistance of the German defenders.79

35 Survivors of the attack offered particularly harrowing accounts. Veteran JohnJ. Ryan, in a 1918 edition of Colonial Commerce,80 described how "One by one the boys were killed or wounded, and then the rear sections came piling in, just in time to receive a great shell that burst in the center of the bunch. A few of the chaps were blown in little pieces."81 The September 1921 edition of The Veteran Magazine,82 the "Beaumont Hamel Commemorative Edition," included a "fittingly and graphically told" account of the advance by Major Arthur Raley from St. John's. In one of the most famous lines written about the engagement, Raley observed thatThe only visible sign that the men knew they were under this terrific fire was that they all instinctively tucked their chins into an advanced shoulder as they had so often done when fighting their way home against a blizzard in some little outport in far off Newfoundland.83 Such eye-witness accounts provided convincing evidence that the Newfoundland Regiment's ability to endure the German's resistance was a victory unto itself.

36 While authors did not hesitate to spell out the number of casualties, they did not describe the horrifying carnage and destruction that the Newfoundlanders had endured.84 Ryan depicted Beaumont Hamel as a deadly affair but was careful not to describe the suffering of the wounded and the dying.85 Casualty figures and battlefield descriptions emphasized the battalion's heroism; the portrayal of danger and lethal opposition gave the attack a greater mythic aura.

37 It was further argued that the Newfoundland Regiment's advance had positive results. First, it was often depicted as a tactical sacrifice which enabled British and French forces to succeed along the southern sector of the Somme front. Second, writers argued that the Regiment's victory at Gueudecourt on 12 October 1916 was made possible by the experience gained at Beaumont Hamel, and the determination to avenge that defeat. Thus the battalion's noble efforts allowed others to succeed on that and future battlegrounds.

38 The southern sector of the Somme front was the only portion of the entire line where the Allies achieved any substantial gains on 1 July 1916,86 and several commentators suggested that the Newfoundland Regiment was instrumental in that success. Engaging a vast number of German machine guns and artillery pieces allowed British and French units in the south to achieve their tactical objectives. McKenzie reproduced a portion of General Hunter-Weston's letter to Prime Minister Morris which made this claim, adding that "[a]n attacking army is like a football team; there is but one who kicks the goal, yet the credit of success belongs not alone to that individual but to the whole team, whose concerted action led to the desired result."87 McKenzie suggested that the Regiment had been the midfielder with the ball who gets seriously injured by a dangerous tackle, but whose effort ultimately allows his striker to score the winning goal. Cramm used the same letter five years later to reinforce his assertion that the southern success owed much to the Newfoundlanders' assault.88 Similarly, Raley argued that the battalion had drawn the fire of numerous German machine-gun and artillery positions away from the southern front, because it advanced without support from neighbouring units. Instead of questioning why the battalion had advanced independently rather than as a part of a wider assault, Raley transformed its action into a successful tactical sacrifice.89 French artillery tactics were probably the deciding factor in the south, but Newfoundland writers were not looking to steal credit.90 Rather, through evidence taken from official military observations and eyewitness reports, such literature sought to convince Newfoundlanders that their battalion had made a vital contribution to the Allies' only concrete success on 1 July 1916.

39 Many commentators attributed the Newfoundland Regiment's victory at Gueudecourt in October 1916 to the fierce combat it had endured three months earlier. After being held in reserve after Beaumont Hamel, the battalion returned to the front line on 12 October 1916.91 Following an all-night artillery barrage the battalion successfully captured the German trenches facing it, secured its left flank after another brigade had been unable to capture the position, and then repelled a major German counter-attack. The Newfoundlanders' victory at Gueudecourt was the only significant gain made by any British unit that day. The battalion inflicted more than 250 casualties upon the Germans and took 150 prisoners; the price was 239 of its own casualties, including 120 dead.92

40 At Gueudecourt the Regiment proved that it had developed into a more effective fighting unit because of Beaumont Hamel, while also avenging its previous defeat. The Times asserted that "[e]very man had fresh in his memory what had happened at Beaumont Hamel."93 Cramm explicitly identified Gueudecourt as the battalion's "first chance for revenge since the reverse and losses at Beaumont Hamel, and the Regiment did not fail to take advantage of it."94 Within the wider context of World War I, Beaumont Hamel was translated into a valuable learning experience which taught the battalion how to fight, endure, and ultimately succeed. In this sense, Beaumont Hamel served as a necessary prerequisite for an inexperienced battalion. In order to succeed, it had to endure defeat first.

41 Such a depiction of Beaumont Hamel was partially determined by contemporary circumstances and intended audiences. Historians of the war were pressured by veterans and civilians to produce positive accounts that could serve as literary memorials,95 and the authors of Newfoundland war literature were not excepted. The accounts of Beaumont Hamel which appeared in The Newfoundland Quarterly, Great War, and The Times History and Encyclopedia of the War were wartime publications intended for public consumption and selectively described the action. Like the immediate press reactions, these pieces also appear to have been partially intended to serve as propaganda to promote the war effort. Cramm's The First Five Hundred appeared in the immediate postwar era when Memorial Day ceremonies were constructing a positive cultural memory of the conflict. Because it appeared in The Veteran, Raley's account was intended for fellow comrades who perhaps sought a commendatory depiction of their efforts on 1 July 1916. While these accounts had different audiences, they were consistent in painting Beaumont Hamel in as positive a light as possible.

42 There was no alternative narrative. Indeed, other than the graphic account provided by John J. Ryan in Colonial Commerce, nothing resembling antiwar literature appears to have been produced in Newfoundland during this period. This differs from Britain, Australia, and Canada, where veterans often produced antiwar literature in the form of biographical accounts of the war, novels, or poetry.96 The books, essays, or official histories mentioned here did not consider Newfoundland's role in a critical or objective light. Newfoundland war literature was overwhelmingly supportive of the 'Beaumont Hamel-centric'Great War myth, offering readers factual evidence to support the mythic claims expressed in formal commemorations.

43 In the years immediately following Beaumont Hamel, literature reaffirmed the attack's revered position within Newfoundland's Great War myth. Fentress and Wickham note that selectivity, distortion, and inaccuracy are common (though not necessary) features of social memory, and many writers incorporated some of these elements into treatments of the attack.97 Although these accounts abstained from taking a critical stance, they did not make false charges about the engagement either. Instead, the battlefield was presented in a highly selective manner which did not compromise the accepted mythic version of the attack. Historical accounts reinforced mythic perceptions with concrete historical evidence that justified and gave greater authority to the high claims of Memorial Day rhetoric. Historical literature provided Newfoundlanders with a more intimate and seemingly realistic depiction

44 of Beaumont Hamel which added to, rather than stripped away, the mythic layers of cultural memory.

45 War monuments gave physical shape to the commemorative concepts and mythic perceptions of Beaumont Hamel. The mythic overtones that permeated commemorative services and historical literature were most evident in the Beaumont Hamel Memorial Park, officially opened on 7 June 1925. Through a combination of masonry, sculpting, landscaping, and preservation, the park symbolized Beaumont Hamel as a victorious and inspiring achievement. It also represented how Newfoundland wished to be perceived by an international audience, suggesting that the attack had enabled Newfoundland to earn higher status within the British Empire.

46 The park also signified an attempt to construct a Newfoundland national heritage rooted in a mythically enhanced historic event, much like Newfoundland's Cabot quadcentenary festivities in 1897 and Quebec's tercentenary celebrations in 1908.98 Beaumont Hamel Memorial Park provided the concrete stamp of approval to Newfoundland's Great War myth, while also speaking in optimistic tones to the dominion's present and future.

47 According to Jacques Le Goff, World War I brought funerary commemoration to new heights, and the resulting war memorials often symbolized "the cohesiveness of a nation united in common memory."99 Like Newfoundland, Canada and Australia also commemorated their World War I dead through overseas memorials often in the form of battlefield monuments that honoured a single climactic engagement. For Canada, that event was the Canadian Corps'victory at the Battle of Vimy Ridge on 9 April 1917.100 According to Denise Thomson and Jonathan Vance the Vimy Ridge Memorial, unveiled in 1936, was an expression of sacred commemoration and a statement of Canadian national identity.101 However, the Canadian and Newfoundland experiences are different in the sense that the Canadian Corps had undoubtedly succeeded at Vimy; the same could not be said of the Newfoundland Regiment at Beaumont Hamel. Garton and Inglis note that Australia was most inclined to memorialize its role in the 1915 Gallipoli campaign during the postwar years.102 Australia's experience at Gallipoli was similar to that of the Newfoundlanders' experience at Beaumont Hamel, as both dominions memorialized their bloodiest wartime engagements as events which made them into stronger nations.

48 Beaumont Hamel was identified as such an event soon after it occurred. On 19 July 1916 the Telegram reported that the battlefield had been renamed St. John's Wood, and on the following day the newspaper's editor suggested the title gave a "hint of the nature of the feat performed by the Battalion. It helps to confirm the impression that it was a high one. It is a rare compliment, this naming of a field of battle after our capital, implying a rare gallantry that deserved it."103 On the attack's first anniversary Prime Minister Morris proclaimed thatJuly 1st, will, in future, be the day we celebrate because it is the anniversary of the day our heroes fell facing the foe. The glory of the Newfoundland troops has become a permanent page in the history of the world's greatest achievements and July 1st will always be a beacon light of liberty for Newfoundland....104 The bloody engagement was quickly being translated into a heroic defence of Newfoundland's freedom, leading many to believe that Beaumont Hamel was sacred national soil which the dominion rightfully owned and needed to reclaim.

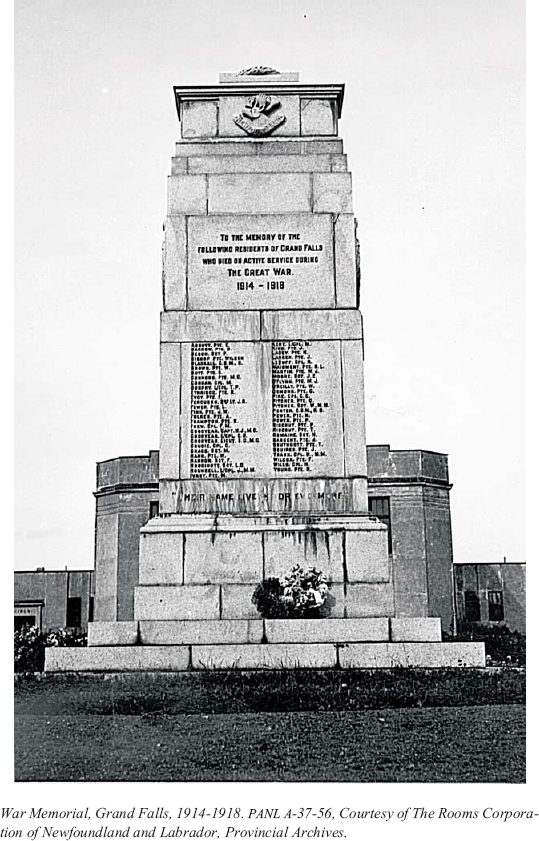

War Memorial, Grand Falls, 1914-1918. PANL A-37-56, Courtesy of The Rooms Corporation of Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Archives.

Display large image of Figure 3

49 Efforts to acquire the battlefield began once the war ended. After consulting with the GWVA's Memorial Committee, Prime Minister Richard Squires announced his government's intention to help fund the construction of a memorial park at Beaumont Hamel. In January 1920, Squires appointed the Newfoundland Regiment's former chaplain and GWVA member Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Nangle to negotiate the purchase of the battlefield and to supervise the construction of a memorial park. The government granted Nangle $15,000 to start the project.105 These efforts generated excitement within Newfoundland, and an editorial in the April 1921 Veteran commented that "we shall be the proud possessors of the sacred battlefield — the only land owned by Newfoundland in France."106

50 Events in Newfoundland and France moved along smoothly throughout 1921 and 1922. The Ladies' Auxiliary Committee of the GWVA formed a sub-committee to raise money for the purchase of the site, and the Beaumont Hamel Collection Committee was established in the spring of 1920 by a group of prominent St. John's residents.107 Both fundraising campaigns were successful — the Beaumont Hamel Committee raised almost $8,000 by August 1922.108 Nangle completed the purchase of the land during the summer of 1922.109 In October he commissioned the Flemish landscape architect Rudolph Cochius110 to design the layout for the park. The government granted an additional $25,000 to ensure that the work would be completed.111

51 Providing funding for the park's construction was something of a sacrifice in itself, given the country's economic and financial condition,112 but the project remained a priority because it was intended to be more than a war memorial. This fits well with Benedict Anderson's argument that official state nationalism often serves as a conscious, self-protective policy.113 From this perspective, memorializing Beaumont Hamel was too great an opportunity for national promotion for the government to let pass. In November 1922 Nangle informed Squires that he and Cochius planned to build "a proper 'Memorial Park' which would be an honour to the Men who fell there and an advertisement of the Colony."114 They intended the park to honour the precise moment when Newfoundland stepped onto the road of nationhood. If Peter Pope is correct in his assertion that the 1897 Cabot quadcentenary celebrations had more to do with "nationalism than navigation,"115 then it is quite likely that commemoration was not intended to be the sole symbolic purpose of the Beaumont Hamel memorial.

52 Construction began in the spring of 1923.116 Because they also conceived of Beaumont Hamel as "a resting place for Newfoundland's nearest and dearest,"117 Nangle and Cochius made a concerted effort to convert the battlefield into a transplanted piece of Newfoundland soil.118 A visitor's lodge was built from Newfoundland lumber; more than 5,000 native Newfoundland trees were planted around the battlefield's outer edges; and the 50-foot-high granite pedestal where the park's central monument would stand was covered with Newfoundland shrubs and flowers.119 The beautification efforts also symbolized nature's ability to overpower the scourge of war. Concerning the layout of the park, Cochius wroteThe sternness and the tragedy of War are passed from the scene. Where, then, was conflict, now is peace; harmony is enthroned where discord was; and beneath the sacred sod of the transformed wilderness, their duty done, their valour proved, their sacrifice complete, lie the mortal remains of hundreds, whose memory still shines in the hearts and homes of this land.120 A significant portion of Newfoundland's manhood and future had spent its blood on that battlefield, and beautifying it with Newfoundland flora was an explicit statement that those grounds were the dominion's rightful property. Beyond that, the replacement of wartime devastation with natural beauty was also meant to symbolize Newfoundland's collective determination to persevere through the hardship caused by the advance to regain postwar stability. If the battlefield could recover from the damage it had sustained, then so too could Newfoundland society.

53 The park's main sculpture suggested that the Newfoundland Regiment had made its sacrifice willingly and courageously. British sculptor Basil Gotto designed a bronze caribou replica reminiscent of the caribou which appeared on the battalion's emblem.121 Placed on top of the granite mound overlooking the battlefield, an oversized caribou arched its head, crowned with an imposing set of many-pointed antlers, as if in mid-bellow. The Veteran called the sculpture a "majestic animal ... bugling his battle challenge."122 It suggested how the battalion had performed at Beaumont Hamel, and how Newfoundland wished for the effort to be commemorated. The sculpture also represented Newfoundland's covenant with its fallen to ensure that their memory would forever be venerated and preserved.

54 Perhaps the most striking feature of the park was what had not been altered. The battlefield was unchanged since the war, so Cochius and Nangle agreed that the park's design should "preserve and accentuate these features," while also allowing limited access to trenches near the monument site. As The Veteran reported, the preserved battlefield would allow visitors to grasp some sense of what it had been like to be at Beaumont Hamel.123 Preserving the cratered and trench-ridden battlefield within a closed, sacred space was meant to remind visitors of the high price which the Newfoundland Regiment had paid, and to amplify the park's reassuring message. The battlefield was sacred ground which no amount of commemorative development could enhance any further.

Opening of Beaumont Hamel Park, 1925. PANL NA-3106, Courtesy of The Rooms Corporation of Newfoundland and Labrador, Provincial Archives.

Display large image of Figure 4

55 Beaumont Hamel Memorial Park was lauded as a commemorative and national success at its unveiling on 7 June 1925. The dignitaries present included Newfoundland's Colonial Secretary John R. Bennett, representatives of the GWVA, and Marshall Fayolle of the French General Staff. In contrast to Eric Hobsbawm's argument that many colonies and dominions developed a brand of anti-imperial nationalism after World War I,124 the unveiling of Beaumont Hamel Memorial Park suggested that Newfoundland had attained a more prominent rank within the British Empire. Any sense of Newfoundland nationalism that had been generated by Beaumont Hamel had been achieved within a broader imperial framework, which corresponds with Pope's belief that Newfoundland's national myth surrounding the Cabot 1497 landfall claims was largely influenced by British cultural traditions.125

56 The caribou monument was draped with a giant Union Jack for the occasion, and was unveiled by Field Marshal Haig.126 In a speech reminiscent of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, Bennett stated that "we are met on one of the great battlefields of the war, and we are here to dedicate a portion of that battlefield as the resting place of ... our fellow countrymen who gave their lives to the cause of civilization on the First of July, 1916."127 Beaumont Hamel was Newfoundland's Gettysburg, 'Hallowed Ground' apparently earned by the dominion through the sacrifice and loyalty to the Mother Country which its soldiers had displayed there. Essentially, Newfoundland could not celebrate the birth of a national heritage at Beaumont Hamel without first acknowledging its position within, and debt to, the British Empire.

57 The park was physical evidence that, with determination and perseverance, victory could be achieved in the face of seemingly inevitable defeat. Instead of choosing a field of victory for the memorial, Haig noted that Newfoundland hadchosen instead a locality where courage, devotion, and self-sacrifice were poured out, as it seemed at the moment, to no purpose. You have chosen a scene which in July 1916, seemed to many, remarkable for the failure of British arms. I think that you have chosen well.... Here your comrades died in the hope of that victory which they would never see. Today that victory is achieved.128

58 This was a bold statement from Haig, who seemed to be suggesting that the Somme Offensive and the assault at Beaumont Hamel could have been conducted with better outcomes. He suggested that victory could be found in resounding defeat, and he identified the park as a fulfilment of the victory which Newfoundland's soldiers had been unable to achieve nine years earlier.

59 In successfully reclaiming a sacred part of Newfoundland's past, the government and the designers had also constructed a reassuring message about the country's future. The Telegram commented that "it will always be regarded as hallowed ground, and it is for us and those who come after to see that it is tended with zealous care."129 The park was not a cemetery for mourning, but a shrine honouring national accomplishment and progress which proclaimed that the attack was the sacrificial pillar upon which a great nation could be founded. The caribou sculpture, transplanted vegetation, preserved battlefield, and ceremonial oratories served as the final confirmation of Newfoundland's 'Beaumont Hamel-centric' Great War myth, the point where myth and reality harmoniously met. By capturing the mythic memory of Beaumont Hamel in stone and space, the park represented the best chance for that triumphant cultural memory to survive on to future generations.

60 The triumphant cultural memory of Beaumont Hamel did not endure. Not long after the Memorial Park was opened, the country which it represented ceased to exist as an independent political unit. The Great Depression struck Newfoundland hard, and the results were disastrous. Newfoundland surrendered its sovereignty in February 1934 to an appointed Commission of Government.130 In two hotly contested referendums in 1948, Newfoundlanders chose Confederation with Canada, and their country became a province on 31 March 1949.131 Until that time, the mythic image of Beaumont Hamel remained a cultural symbol of national resistance, unity, and accomplishment. If "social memory exists because it has meaning for the group that remembers it,"132 then the memory of Beaumont Hamel had to change to ensure its sustained relevance. From 1949 forward, the proud memory of Beaumont Hamel as a triumphant national anniversary ceased to exist, becoming instead a painful reminder of an incurable wound suffered by a dead country.

61 Beaumont Hamel is still promoted as Newfoundland's most significant moment in World War I, but it is recalled in solemn and critical terms. In 2003, Memorial Day was observed in St. John's on Sunday, 29 June, and the programme was remarkably similar to the one first introduced in 1917.133 The Telegram reminded readers to pause on the anniversary "of the battle to remember those who paid the ultimate price in the war meant to end all wars."134 While the practice remains the same, the tone and symbolism of those ceremonies have been revised drastically. Today, Memorial Day is a sombre occasion when Newfoundlanders mourn Beaumont Hamel as an event which earned them nothing and stole their nation away.

62 Beaumont Hamel is still a popular topic for historians and writers. According to John FitzGerald, the attack was "an event that cut so deep into all aspects of Newfoundland society that it changed the course of the country forever."135 The novelist Kevin Major has called Beaumont Hamel "the single greatest tragedy in the history of Newfoundland and Labrador," an event which "left a wretched pall over the country."136 In his best-selling 1995 novel No Man's Land, Major depicted Beaumont Hamel as a senseless bloodbath that robbed Newfoundland of young men who could have led their nation to postwar prosperity.137 In The Danger Tree: Memory, War, and the Search for a Family's Past, David Macfarlane suggested that the absence of a generation of young Newfoundlanders was Beaumont Hamel's most noticeable legacy. He wrote that after the engagement "the best were gone ... or doomed, and what the world would have been like had they not died is anybody's guess.... Their plans were left in rough draft, their sentences unfinished.... No oneexpected it to be like this."138 The journalist and news broadcaster Jim Furlong has lamented the Newfoundland Regiment's defeat at Beaumont Hamel in The Newfoundland Herald, arguing that "[t]hey were not ordinary men. They were the type of men you could build a nice small nation around. They were the men who might have made a difference in Newfoundland's future."139 Contemporary literature and editorial columns often suggest that Beaumont Hamel was the event which fatally crippled Newfoundland's nationhood.140

63 On 10 April 1997, Beaumont Hamel Memorial Park was declared a National Historic Site by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, because "Newfoundland's accomplishment, contribution, and sacrifice in the First World War are themselves of major national importance. The loss of Newfoundlanders in the First World War had a profound impact on the colony."141 World War I might have been Canada's road to national maturity, but it ended Newfoundland's national potential. From this Canadian perspective, Beaumont Hamel is a reminder to Newfoundlanders of their country's mortal wounding and subsequent rescue by its neighbouring dominion. The website "Newfoundland and the Great War," constructed by students and faculty from Memorial University of Newfoundland, states that Beaumont Hamel "has typified the spirit of Newfoundland," and that since 1925 the memorial park has stood as "its lasting testimonial."142 If the website is correct in its assertion, then that spirit is one characterized by regret and a nostalgic yearning for what could have been. At Beaumont Hamel Memorial Park the Newfoundland Regiment's advance has been symbolically preserved, but the event and its memory can never be erased.

64 Today, Beaumont Hamel is remembered by a Newfoundland society which, according to Jerry Bannister, recalls its past with a sense of tragic nostalgia. In turn, the attack is perceived in a manner which enables it to fit this tragic context.143 Rather than commemorating Beaumont Hamel and acknowledging what transpired in its aftermath, modern-day observers lament the bloody encounter and conjure visions of a Newfoundland where it had never happened. Applying the hypothetical "what if?" to history can be a stimulating and imaginative exercise, but such manipulated alternatives have no chance of transpiring. We know of the terrible casualties suffered by Newfoundland servicemen during World War I; the severe postwar economic and political turmoil which crippled Newfoundland; that the dominion surrendered its democracy to a British-appointed commission which governed it until after World War II; and that it became a Canadian province in 1949. Hindsight allows present-day observers to identify Beaumont Hamel as the start of a tragic avalanche.

65 However, this contemporary view ignores the circumstances in which the attack occurred and was subsequently commemorated. Beaumont Hamel had a very different symbolic significance for Newfoundland, the dominion, than it does for Newfoundland and Labrador, the Canadian province. Before 1949, Beaumont Hamel was not identified as being Newfoundland's fatal national wound, and it was not recalled with regret or resentment. Between 1916 and 1925 Beaumont Hamel was depicted as a national triumph which should inspire Newfoundlanders to look confidently to their future. During a period when Newfoundland was weathering a storm of economic and political duress, an assortment of mythmakers constructed a mythic memory which suggested that World War I had reinforced the country's place within the British Empire, and Beaumont Hamel was identified as the bloody anvil upon which Newfoundland the colony had been forged into Newfoundland the nation. When Newfoundland was against the ropes in the early 1920s, Beaumont Hamel was triumphantly recalled as the event which should inspire the country to fight its way out of the corner. Today, it is recalled as the knockout blow which forced Newfoundland into national retirement. If cultural memory of the past can only remain relevant through its manipulated applicability to the present, then Newfoundland's cultural memory of Beaumont Hamel is an example which firmly supports that perspective.

66 It was probably in the best interest of Newfoundland's mythmakers to recall the attack in admirable and triumphant fashion. The state, press, and heads of Newfoundland's various religious denominations had all proactively encouraged Newfoundland's participation in World War I,144 so for them to recall the conflict in a critical or negative manner would have been to expose themselves to justifiable charges of hypocrisy and deceit. Thus, it is not surprising that newspaper editors spoke of Beaumont Hamel in heroic terms; that clergymen gave sermons which recalled the advance as a glorious Christian sacrifice; and that the state provided more than two-thirds of the funding for the $58,000 Beaumont Hamel Memorial Park which they envisioned as a nation-building tool.145 The rituals, rhetoric, and sculptures which informed Newfoundland's 'Beaumont Hamel-centric'Great War myth were probably nothing more than a series of shrewd moves by Newfoundland's ex-war-promoters turned postwar mythmakers to curb some of the overwhelming grief and tremendous shock that undoubtedly affected the bereaved families of those who had died on 1 July 1916.

67 Why was Beaumont Hamel bestowed with such mythic significance by mythmakers in postwar Newfoundland? After July 1916 the Newfoundland Regiment fought successfully in a number of battles during the final two years of World War I. The battalion achieved a stunning victory at Gueudecourt in October 1916; experienced further, but costly, successes at Sailly-Saillisel, Monchy-le-Preux, and Cambrai in 1917; before the year's end it became the only unit to receive a Royal prefix to its title during the conflict; and the Newfoundlanders were also involved in the final Allied charge that forced the Germans to concede defeat in November 1918.146 So why was the bloody failure of Beaumont Hamel transformed into a triumphant symbolic microcosm for Newfoundland's war effort? Because at no other time during the conflict did the dominion field a larger battalion; at no other time was it involved in a more anticipated offensive; at no other time did it suffer more casualties; and according to Newfoundland's mythmakers, at no other time did the dominion's soldiers perform more nobly in the service of their dominion, their empire, or their God. Beaumont Hamel was quickly identified as Newfoundland's wartime benchmark and turning point in much the same way that the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 was identified as "the high water mark of the Confederacy" during the American Civil War.147 If victory had been a requisite for the establishment of a military or national heritage, then a successful assault such as Gueudecourt or Cambrai would have assumed a more prominent position within Newfoundland's Great War myth. Though a military failure, Beaumont Hamel was the standard against which all subsequent Newfoundland military endeavours would be measured. Once the full scope of the defeat was realized, the mythmaking process functioned to turn Beaumont Hamel into as successful a standard as selective memory construction would allow. The outcome on 1 July 1916 did not matter under these circumstances — how that result could be applied within a broader social context did.

68 Remembering Beaumont Hamel in the period considered by this study had more to do with honouring conjured mythic images of the attack than mourning the losses it had caused. Myth was promoted as being a stronger influence on postwar Newfoundland society than reality. The lack of emphasis on what actually happened to the Newfoundland Regiment on 1 July 1916 prevented Beaumont Hamel from being recognized as a bloody military failure sooner than it did. Editorial, ceremonial, literary, and monumental emphasis on what the battalion had supposedly achieved that day enabled it to become Newfoundland's mythic pillar of remembrance. These commemorative mediums not only reinforced one another, but they also added their own distinctive remark to the mythic answer which they offered to Newfoundlanders. Essentially, remembering Beaumont Hamel in the decade after it occurred was not about accurately recalling events and their impact — it was about rationalizing a terrible event and finding concrete positives where none can ever be found.

Note