Article

The Danny Williams Government, 2003–2010:

“Masters in Our Own House”?

Introduction

1 Danny Williams was Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador for just over seven years, from 6 November 2003 to 3 December 2010. His principal claim, which resonated well with the electorate at the time, was that, under his leadership, the province would become “masters in our own house,” thereby breaking its long-term dependency on the federal government and outside corporations. This approach appeared to be successful during his years as Premier. Due mainly to a huge increase in the price of oil that coincided with Williams’s premiership, Newfoundland and Labrador prospered as never before (or since). For the first and only time since Confederation with Canada in 1949, it became a “have province.” As the province prospered, Williams’s reputation soared. He became one of the most popular provincial premiers in Canadian history. Unlike most of his predecessors, Williams was just as popular when he announced his retirement in the fall of 2010 as he had been at any time during his premiership. In retrospect, however, Williams’s reputation has been sullied by his leadership role in the ill-fated Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project, which Williams had announced with great fanfare just a week before he announced his retirement.

2 This article reviews Williams’s premiership, focusing on his efforts at economic and social development.1 The main body of the article focuses on the seven years when Williams was Premier. But, because of his leadership role in initiating it, the final section reviews the Muskrat Falls project briefly and how it might affect Williams’s reputation in the long run.

A Premier in Waiting

3 Danny Williams was unique among Newfoundland and Labrador premiers in that his accession to the premiership was long anticipated by many people in the province. Williams was born in St. John’s on 4 August 1949, just five months after Confederation. Hence, he just missed out on being born a Newfoundlander and grew up during the first years of the erstwhile country becoming the tenth province of Canada.2 Williams was very much a “townie,” and an upper-middle-class townie at that. The Williams family were avid Progressive Conservatives (PCs) as behind-the-scenes supporters, organizers, and election campaigners for the party. Hence, Danny Williams grew up as a Progressive Conservative, but one for whom progressive was the more important part of the name. He told me that he was fiscally conservative but socially progressive.3 This helps explain his later disdain for Stephen Harper and his more right-wing conservatism.

4 Although Williams was very much a city boy, he had an outgoing personality and a way of getting along with people from all walks of life that resonated well with rural Newfoundlanders and Labradorians. Danny was always “one of the boys,” albeit a very successful one. Even before he went into politics, he was known as “Danny” in a way that was reminiscent of Newfoundland and Labrador’s first Premier, Joseph Smallwood, being known simply as “Joey.”

5 Williams received his early education at St. Bonaventure’s College and Gonzaga High School in St. John’s. He earned a degree in political science and economics from Memorial University and, in his graduating year, was awarded the Rhodes Scholarship for Newfoundland and Labrador for 1969. At Oxford, he studied arts and law, and then went on to Dalhousie University where he completed his LL.B. Starting in 1972, Williams became a successful lawyer, taking on several high-profile cases, including the Mount Cashel Orphanage sexual abuse scandal. He was appointed Queen’s Counsel in 1984. Concurrent with building his law practice, Williams also took the lead in developing Newfoundland’s first cable television company, Avalon Cablevision. This became one of the biggest and most successful cable television companies in Atlantic Canada.

6 Over the years, Williams had maintained his interest in politics, and was approached from time to time about running for office. But he did not feel inclined to become involved in the all-consuming life of a political leader while he and his wife were raising their children. By the year 2000, however, his children had grown up, he had turned 50 the year before, the ruling Liberal Party was looking vulnerable after Brian Tobin’s hasty exit and a bitter leadership contest, and he felt that the time was ripe for him to devote the next 10 years of his life to politics. A change of government was in the air if the PCs could find a dynamic new leader. The obvious choice, when he became available, was Danny Williams.

7 To clear the way for this radical change in careers, Williams felt that he first had to get rid of his major asset, the cable company, because he couldn’t find himself in a position of sending out bills to thousands of people if he were also their Premier. So he sold the company, reportedly for over $200 million. This put him in an advantageous position: “I was in a position where I had independent wealth, it’s nice to have financial autonomy, and I could be totally my own person.”

8 Williams recognized, however, that running a government is a very different proposition to running a business or a law firm.

Preparing to Govern

9 Danny Williams became the leader of the provincial Progressive Conservative Party in April of 2001 and won a by-election in the west coast district of Humber West. Initially, Williams felt impatient for the next provincial election. The incumbent Liberal Premier, Roger Grimes, however, had his own agenda and priorities that he wanted to address as best he could. Realistically, Grimes recognized that he was likely to lose the next election, so he hung on for as long as he could.4 Eventually, the election was called for 21 October 2003, two-and-ahalf years after Williams had become leader of the official opposition.

10 Reflecting on this 13 years later, Williams recognized that the long wait was a positive advantage for him and his team: “I was thinking that there would probably be an election sooner rather than later. As it happened there wasn’t, which was probably the best thing that ever happened to me, because I realized that I had a huge learning curve ahead of me as far as government and running a province went.”

11 The key advantage was that Williams, his senior policy advisor, Lorne Wheeler, and the other members of his team were able to prepare thoroughly in advance of forming the government. Williams emphasized how important these preparatory years were to his premiership. He and his team, made up mainly of himself, Lorne Wheeler, and senior members of what was then a small opposition caucus, drafted a document that would serve as both an election platform and a blueprint for the two terms for which Williams hoped to be Premier. It was, in Wheeler’s term, a “rolling document” that kept being revised and re-revised many times before it was finalized.

12 While this was a multi-faceted document, Williams’s main focus from the outset was “three major things that I wanted to tackle.” The first was our relationship with the federal government and our share of the offshore. “We didn’t need $5 million cheques, we needed billion-dollar cheques.” Although the Atlantic Accord, signed in 1985, had stated the fundamental principle that Newfoundland and Labrador should be the primary beneficiary of its offshore oil and gas resources, this was not happening in practice. The second major battle was with the oil companies to ensure that the province received a larger share of revenues from the offshore. The third was Churchill Falls, “that’s got to be tackled as well. I took on the federal government first, then I took on the oil companies and finished up with Churchill Falls, and then basically my bucket list was done.”

13 The final version of the plan was called Our Blueprint for the Future.5 Because it proved to be an important document in practice, not just a party platform to be shelved once the election was over, I will discuss it here in an introductory way, and refer to some of its specific action items later. The Williams government’s plan, or “the blue book,” as it was generally referred to in government circles, guided the approach and actions of the government during Williams’s premiership. Several senior officials within the provincial government commented on this to me. They were surprised and impressed by the extent to which the Premier and his ministers really did attempt to oversee the implementation of most of the items included in the blue book. Many of the items were implemented more or less as envisioned, such as the establishment of an energy corporation, the implementation of a poverty reduction strategy, and the passing of a sustainable development act. Some were modified in implementation, for example, the proposed Chief Information/Innovation Office position was divided in two: a Chief Information Officer as a stand-alone agency and an Assistant Deputy Minister of Innovation within the Department of Innovation, Trade and Rural Development. A few items, such as the building of a fixed link between the island and Labrador, were researched but not acted on as they would have proven to be too costly.

The First Year: The Fiscal Challenge and Labour Relations

14 After he had stretched his premiership to the limit, Roger Grimes called for a provincial election in the fall of 2003. Danny Williams and his party won the election, capturing 34 of the 48 seats in the House of Assembly and nearly 59 per cent of the popular vote. The new government took office on 6 November 2003. In the short term, however, Williams, his newly minted Minister of Finance, Loyola Sullivan, and the rest of his cabinet and government were stalled in their intention to implement their blue book plan. In what by now had become a familiar pattern in government transitions in Newfoundland and Labrador, they found that the financial state of the province and its government was more precarious than they had realized. The new government commissioned an independent assessment of the province’s finances by the chartered accounting firm, PricewaterhouseCoopers, which confirmed that action needed to be taken on the province’s debt. It had stood at around $6 billion in 1992–93 and threatened to reach almost $16 billion by 2007–08. Williams and Sullivan determined that their first order of business had to be to get the provincial government’s fiscal house in order.

15 To deal with what it viewed as an immediate debt crisis, the government took several measures. The most controversial were their intentions to downsize the public service by 4,000 and to freeze the wages of public servants for two years. At the same time, Williams promised the public servants that they would be recompensed in the future when the fiscal situation of the province improved. The government also instructed every department and agency of the provincial government to propose ways in which their annual budgets could be cut by 20 per cent.

16 These measures were felt as a betrayal by the main public-sector union, the Newfoundland and Labrador Association of Public Employees (NAPE), many members of which had voted PC in the recent election, and by the Newfoundland and Labrador Federation of Labour (NLFL) and its president at the time, Reg Anstey. NAPE members voted for strike action and Anstey made some uncomplimentary comments about Danny Williams in the local media. Tension was heightened when the government passed legislation that ended the strike and forced the public servants back to work.

17 This was a difficult time for the Williams government. Williams’s popularity dropped to the lowest it was ever to be, and his relationship with organized labour got off to a rocky start.

Non-Renewable Resources: An Oil Bonanza and Mining Growth

18 The 1985 Atlantic Accord stated that its fundamental purpose was “to recognize the right of Newfoundland and Labrador to be the principal beneficiary of the oil and gas resources off its shores, consistent with the requirement for a strong and united Canada.”6 The Accord on the whole is a strong document, but its one weakness is its ambiguity about the role of equalization payments in determining what is meant by “principal beneficiary.” Since Canada’s equalization program includes revenues from non-renewable natural resources as part of its complicated formula, as offshore oil revenues increase, provincial revenues from equalization would decrease by a similar amount. Hence, there would be no net benefit to the province. Recognizing this, the architects of the original Accord included a section on equalization offset payments. This, too, was complicated, with Part I offset payments to last for 12 years from the commencement of first production, and then Part II offset payments “equivalent to 90 percent of any decrease in the fiscal equalization payment to Newfoundland in respect of a fiscal year in comparison with the payment for the immediately preceding fiscal year.” Beginning in the first fiscal year of offshore production, “this offset rate shall be reduced by ten percentage points and by ten percentage points in each subsequent year.”7

19 The unintended consequence of this provision was that, over the years, when equalization payments are included in the calculation, the federal government’s net benefit from Newfoundland and Labrador’s offshore oil production greatly exceeded that of the provincial government. In a background paper prepared for the province’s Royal Commission on Renewing and Strengthening Our Place in Canada, John Crosbie, who as federal Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada was one of the signatories to the 1985 Accord, concluded as follows:

Whether Crosbie’s calculations were precise or not, the main point is clear. When equalization effects are taken into account, with revenue from non-renewable resources included in their calculation, Newfoundland and Labrador was far from being the main beneficiary of its offshore oil production. This glaring fact was the starting point for Danny Williams’s battles with Ottawa and the major oil companies operating in the Newfoundland and Labrador offshore.

20 Fortunately for the new Premier, there was a minority federal government in Ottawa at the time, led by Prime Minister Paul Martin. Martin’s power base was precarious as the country headed towards a federal election in 2004. This meant that Newfoundland and Labrador’s seven federal seats could prove crucial in tipping the balance in the forthcoming election. Williams was in a stronger bargaining position than is usual for the premier of a small province. And he had the personality and strength of will to take full advantage of this opportunity. Martin promised verbally to agree to a revision of the Atlantic Accord that would honour the principle of Newfoundland and Labrador being the principal beneficiary of its offshore oil. Just before Christmas in 2003, Williams flew to Winnipeg for a meeting with the Liberal Minister of Finance, Ralph Goodale, in the expectation that this verbal commitment was to be confirmed officially.

21 Williams’s tactic of taking down the Canadian flag at all provincial government buildings was controversial and caused a furor in the country. Nevertheless, a few days later, Paul Martin agreed to meet with Williams and between them they hammered out an agreement on what they called the Atlantic Accord 2005. Paul Martin’s version of events was rather different from the “capitulation” that he was accused of by mainland pundits. According to Martin, he was sympathetic from the outset to Newfoundland’s case and fully intended to follow through on his earlier promise.

Whatever the course of the negotiations between Williams and Martin, the outcome was very favourable to Newfoundland and Labrador. Paul Martin agreed to amend the Atlantic Accord to the effect that the government of Canada would “provide additional offset payments to the province in respect of offshore-related Equalization reductions, effectively allowing it to retain the benefit of 100 percent of its off-shore resource revenues.”10 This agreement would be in effect initially from 2004 to 2012, reduced gradually for the period 2012 to 2019 if the province was no longer eligible for equalization (it wasn’t, having become a “have province” in 2008), and reviewed in 2019. To put it into effect, Ottawa provided the government of Newfoundland and Labrador with an advance payment of $2 billion to reduce its outstanding debt. Danny Williams returned to the province triumphantly, pumping his fist and shouting “We got it! We got it!” He received a hero’s welcome at St. John’s airport.

22 Having successfully negotiated a satisfactory deal with the federal government, Williams then turned his attention to the second item on his bucket list, the negotiation of a better deal with the oil companies for the development of subsequent oil and gas projects offshore. Williams took what he called a three-pronged approach — to get greater royalties, to get an equity share in the new fields as they were developed, and to get more processing in the province. The third was used mainly as a bargaining tool, conceding privately that, because there was already a surplus of refineries and petrochemical complexes where you really needed a huge critical mass, it was unlikely that he would succeed on this front. So he held this in reserve as something that he could appear to concede on in order to get his way on his equity and royalty objectives.

23 Direct participation through demanding an equity position was controversial. Although common practice in most oil-producing jurisdictions around the world, it was not the common practice in the United States and Canada. The oil companies’ resistance was due in part to their concern about setting a new precedent for their North American operations. Williams believed that taking a small equity position would have two important benefits. The first is that, over time, the province would almost certainly receive a positive return on its investment through its share of the profits once the new fields began producing. The second, equally important, benefit is that by becoming a shareholder, the province would have a seat at the table of the board of directors of the project, and thereby have access to information that otherwise the companies would hold close to their chests. Participation would also contribute to provincial officials gaining more expertise about the workings of the industry. This approach, however, is costly in the short term and, if oil prices were to fall later (as they did), risky in the long term.

24 These were the basic considerations that guided Williams’s negotiations for the development of Newfoundland and Labrador’s third major oil field after Hibernia and White Rose, the Hebron/Ben Nevis field. The oil companies’ first response to Williams’s three demands was to refuse and to threaten to walk away from the project. Like Brian Peckford in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Williams came under a lot of pressure, including from the local business community, to relent and make a deal so that the project with its attendant business activity and employment benefits could get underway. But Williams was adamant in his position.

25 As world oil prices rose dramatically during the mid- to late 2000s, ExxonMobil, the largest shareholder and operator for the Hebron project, did come back to the negotiating table. Williams conceded on his third condition, local processing, and the operator and its private-sector partners agreed to the province taking a 4.9 per cent equity position in the Hebron project. They also agreed to an enhanced royalty regime, including a super royalty if and when the price of oil was to exceed $50 a barrel. Subsequently, the precedent having been set, the provincial government was able to negotiate similar deals on the West White Rose project (5 per cent equity) and the Hibernia Southern Extension project (10 per cent equity).

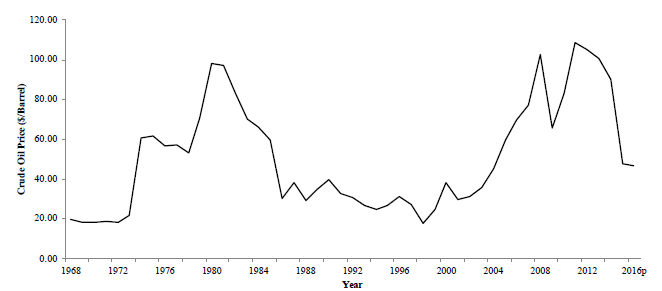

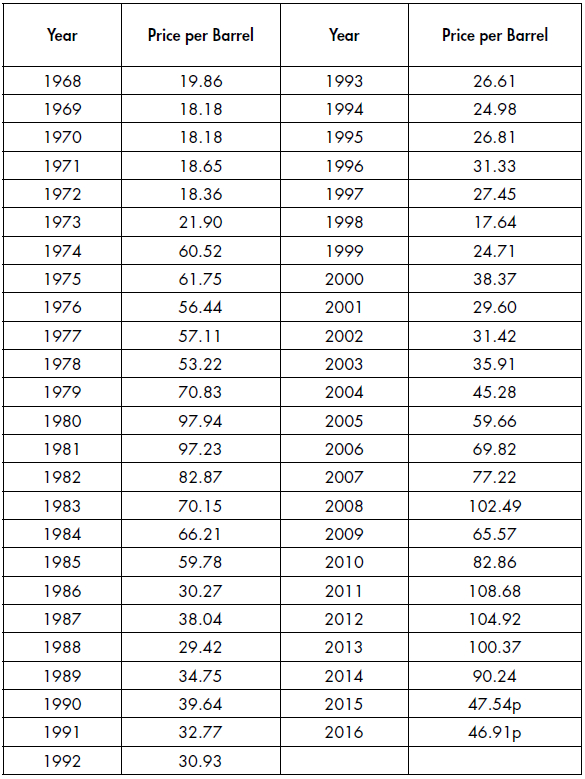

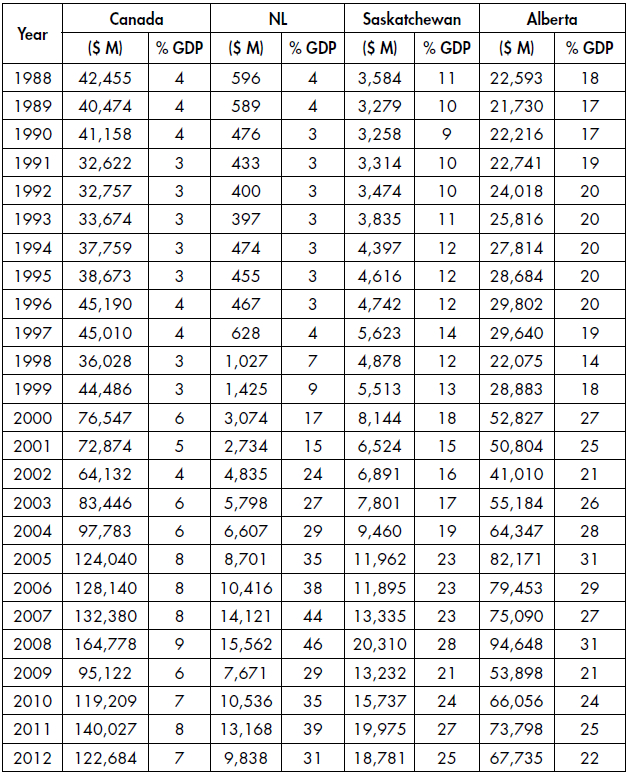

26 If Clyde Wells was the unluckiest post-Confederation Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador, due to the serious province-wide crisis induced by the groundfish moratoria of the early 1990s, Danny Williams was the luckiest, due to the dramatic increase in the world price of oil during the first decade of the twenty-first century. As Table 1 and Figure 1 show, the price of oil per barrel rose from US$35.91 in 2003 to US$102.49 in 2008. The percentage of the province’s GDP from mining and petroleum also jumped, from 27 per cent in 2003 to a high of 46 per cent in 2008, considerably higher than the other main Canadian oil-producing provinces, Alberta and Saskatchewan (Table 2).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 2

27 In addition to the dramatic rise in provincial revenues from off-shore oil developments, the Danny Williams years also enjoyed a significant rise in revenues from the mining industry, primarily from the Voisey’s Bay nickel project. While in opposition, mainly for political reasons, Williams had expressed skepticism about the project. Nevertheless, it proved to be highly successful and, ironically, it was his government rather than his predecessor’s that enjoyed most of the increased government revenues generated by the project. Thus, in the provincial government’s projections for 2007–08, for example, in addition to the $1.25 billion direct revenues from offshore oil, the province also anticipated getting over $200 million from mining operations.11 Williams and his Minister of Natural Resources, Kathy Dunderdale, managed to negotiate a revision of the 2002 agreement in 2009 that ensured even greater benefits for the province as a condition for Vale Inco being given an extension for completing the construction of the hydromet processing plant at Long Harbour.12

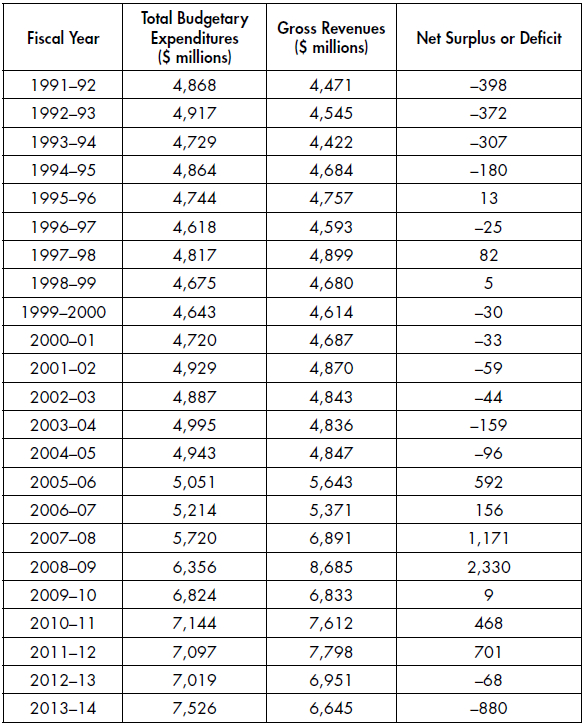

28 The combination of the benefits from both the original Atlantic Accord of 1985 and the amendment of 2004, coinciding with a dramatic increase in the price of oil during the Williams years and supplemented by increased income from the mining sector, induced a period of fiscal well-being for the Newfoundland and Labrador government such as has never been seen before or since. This allowed the tone of the Williams government’s throne speeches and budget speeches to be positive, upbeat, confident, and optimistic in a way that contrasted to most of their predecessors and successors. As Table 3 shows, the government saw budget surpluses from 2005 to 2012. In the words of Memorial University economists Wade Locke and Doug May, the province enjoyed seven years of abundance during which the accumulated surpluses totalled $5.1 billion.13 Rather than the perennial question of how to deal with the deficit, Williams and his finance ministers had the luxury of dealing with the more inviting question of how to deal with the surplus. They tried to take a balanced approach to spending on debt reduction, dealing with what they had identified as an infrastructure deficit, and improving education at both the grade-school and post-secondary levels. The latter included maintaining a freeze on tuition and a student loan debt reduction program. In 2007, the government also reduced the personal income tax rate from the highest to the lowest in Atlantic Canada. In his 2008 budget speech, the then Minister of Finance, Tom Marshall, did sound a cautionary note: “The fact that 37 percent of our revenues accrue from non-renewable resources in an environment of historically high prices gives me cause for concern.”14

Display large image of Table 3

Display large image of Table 3

29 Nevertheless, towards the end of Williams’s premiership, as the world economy sank into a serious recession, the government spent more in a counter-cyclical attempt to lessen the impact of the recession on the provincial economy; and, in keeping with Williams’s promise to compensate public servants for the salary freeze during his first years in office, the government provided them generous salary increases.

30 In later years, many observers were to criticize the Williams government for not establishing a heritage fund based on the Norwegian model. This is debatable. In keeping with sound financial advice, they did pay down the debt considerably, which is arguably preferable to setting up a parallel savings fund while the debt continues to accumulate. And strong cases can be made for attempting to address the infrastructure deficit, strengthen education and training, and even invest in public works in a counter-cyclical attempt to offset the negative impacts of the global recession. If the oil revenues bonanza had continued for many more years, as it had in Norway, a strong case could have been made for establishing a heritage fund, but the seven years of abundance came to an abrupt end after 2012, by which time Danny Williams had retired from politics.

Renewable Resources: Pulp and Paper, and Fisheries

31 With the growth of its two main non-renewable resource sectors, mining and petroleum, and of the provincial government’s revenues from these two sectors, Danny Williams and his government enjoyed a healthy fiscal balance sheet during the second half of the first decade of the twenty-first century. In the long run, however, renewable resources may well be more important. What is often overlooked in reviewing the Williams years is that all was not rosy in the province’s two main renewable resource sectors, forestry and fisheries.

32 When Danny Williams became Premier in the fall of 2003, there were three pulp and paper mills operating in the province, in Grand Falls, Corner Brook, and Stephenville. These mills were all owned and controlled by outside multinational corporations, which for many years had been operating in a highly competitive industry. In North America, branch-plant operations based mainly on fibre from slow-growth forests, which included Newfoundland and Labrador as well as other eastern Canadian provinces, were being challenged by plants that benefited from fast-growth forests, particularly in the southern United States. The first sign of trouble for Newfoundland and Labrador had occurred in the 1980s under the Peckford government. Bowaters announced its intention to shut down its mill in Corner Brook; and it was only through the prodigious efforts of Peckford and some of his senior officials that the province was able to effect a sale of the mill to Kruger. That mill, under the name Corner Brook Pulp and Paper, has been upgraded over the years and continues to operate effectively today.

33 By the early 2000s, the province’s other two mills were owned by Abitibi Consolidated. In 2004 Abitibi gave notice that it was reviewing its operations in Canada with a view to possibly shutting some of its mills, including the one in Stephenville. The Williams government set up a working committee of senior officials to meet with the manager of the mill to carry out their own review and work on ways to improve its operations. The committee was chaired by the Deputy Minister for Forestry at the time. The local managers of the mill were very co-operative and keen to keep the mill going. It was a modern, efficient mill and they were optimistic it could be saved. But they were wrong. The provincial government offered long-range subsidies worth more than $10 million a year. But, from Abitibi’s global perspective, although the Stephenville mill was profitable, it was not as profitable as some of its other mills. In December of 2005, Abitibi announced that it was permanently closing its mills in Stephenville and in Kenora, Ontario. Williams was quoted at the time as saying: “This company is an extremely — and this is the nicest possible way I can say this — an extremely difficult company to deal with.”15 Williams threatened to expropriate the mill and sought but failed to find an alternative operator. The mill closed, putting nearly 300 people out of work. Stephenville adjusted as best it could. The provincial government supported its efforts to attract new businesses to the town. But the main saving grace was that many of the skilled workers from the mill were able to find alternative, well-paying jobs in Fort McMurray and other mainland locales. The Stephenville airport is still operating and the headquarters of the province’s institute of technology, the College of the North Atlantic, is located in Stephenville. Stephenville also continues to be a service centre for the Bay St. George region.

34 The pulp and paper mill at Grand Falls was the oldest mill in the province. Established in 1909 by the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company, it was an early success story of the government-ofthe-day’s efforts at diversifying the country’s economy away from its almost sole dependence on the fisheries. The mill provided employment and was the economic base of the thriving town of Grand Falls– Windsor for 100 years. Its ownership changed hands many times over the years. The last owner was AbitibiBowater, which announced in 2008 that, due to a fall in demand for newsprint, it was consolidating its operations in mills closer to its main markets. It closed the Grand Falls mill in 2009. Lacking any effective bargaining power to prevent this from happening, Danny Williams controversially proceeded to expropriate most of the company’s timber and power generation assets in Newfoundland.

35 Without really meaning to, however, the government also found itself expropriating the mill itself, which was to cost it millions of dollars for environmental cleanup.16 AbitibiBowater successfully protested the expropriation as being contrary to the rules of the North American Free Trade Agreement, but it was the government of Canada that had to compensate the corporation, not the government of Newfoundland and Labrador. The closure of the two paper mills, despite the provincial government’s best efforts to keep them up and running, shows just how difficult it is in practice for a small jurisdiction to be “masters in our own house” in an open, global capitalist economy.

36 Newfoundland and Labrador’s other major renewable resource industry, the fisheries, also remained problematic throughout the Williams years. Unlike Brian Peckford and Roger Grimes, Danny Williams did not include fisheries matters in his own list of major priorities. Nevertheless, he did acknowledge their importance and attempted to appoint fisheries ministers who would provide effective leadership. This is no small task. All fisheries ministers in Canada’s coastal provinces face innumerable difficulties. First and foremost, they lack jurisdictional control over the resource for which they are held responsible. In addition, particularly in Newfoundland and Labrador, they have to contend with incessant social and political pressures from the many individuals, families, enterprises, and communities that depend on fish harvesting and processing as the main source not only for their market incomes, but also for income support through unemployment insurance. As a former successful fisherman, member of the executive committee of the fishermen’s union, and member of the Fisheries Resource Conservation Council, Williams’s first choice as Fisheries Minister, Trevor Taylor, was well qualified for the challenge.

37 Taylor inherited a proposed program meant to bring order and stability to the crab fishery, which had become the main fishery in the province following the groundfish moratoria. The proposed program was called Raw Material Shares (RMS). During the late 1990s, in an effort to help offset the negative impacts of the groundfish moratoria, the Tobin government had issued several crab-processing licences to inshore plants. This contributed to overcapacity and instability in the industry. The intention of the RMS program was to stabilize the industry by capping the amount of raw material that each seafood processor could process. Taylor announced that the provincial government intended to implement such a program as a pilot project for two years. The Association of Seafood Processors (ASP) welcomed the announcement but the Fisheries, Food and Allied Workers Union (FFAW) rejected the proposal outright, fearing that the program would lead to more control over the industry by the ASP and weaken crab harvesters’ flexibility to sell their product to whomever they chose. In March of 2005, the FFAW began a series of protests, some of which were experienced as threatening to Minister Taylor and members of his family. In May, Premier Williams commissioned Richard Cashin, former president of the FFAW, to review the RMS project and make recommendations back to government. Based on his review and meetings he held with the various parties involved, Cashin concluded that “RMS was a seriously flawed concept in its proposed application to the crab fishery. . . . I concluded that, in the changed nature of today’s crab fishery, RMS will not provide the claimed stability or the necessary efficiency improvements. Therefore, it should be dispensed with immediately.”17

38 Cashin had also been asked to comment on what he believed to be the underlying problems in the fishery and what should be done about them. He concluded that he had become “really struck by how much the underlying causes of the current problems in this sector were initially caused by uncoordinated management decisions by the two levels of government, each acting in isolation in its own sphere of influence. . . . The causes of the present state of affairs are so intertwined that a classic case for joint management of the two sectors is obvious.”18 The government accepted Cashin’s recommendation to terminate the RMS pilot project. But, although he agreed with it in principle, Danny Williams never took up the cause of joint management in the fisheries with the same passion he had shown in dealing with the federal government on offshore oil revenues.

39 Williams did not neglect the fisheries, but, like Smallwood and other premiers before him, he found that the problems in the fisheries seemed intractable. In 2007, he convened a two-day fisheries summit of representatives of all the parties involved in the fisheries. Coming out of that convention, he initially felt optimistic that they were getting somewhere. He and his government proposed to the province’s seafood producers that they should combine to form a common marketing agency for Newfoundland and Labrador seafood products, taking advantage of the pending sale of the marketing arm of Fisheries Products International (FPI).

The Williams government did put some money into fisheries research, partly to offset the national government’s “abandonment of fisheries research” under Stephen Harper. The government also put money into aquaculture development on the south coast and instituted a system of custodianship for salmon conservation. On the whole, however, Williams himself expressed disappointment and frustration over his government’s inability to accomplish more on fisheries development.

40 The other major change that took place during Danny Williams’s tenure was the final demise of Fisheries Products International. Established as a Crown corporation after the fisheries crisis of the late 1970s and early 1980s, FPI became a phenomenal success story during the mid- to late 1980s, so much so that its CEO, Victor Young, and his senior executive were able to take great pride in wiping out the corporation’s debts to allow FPI to be privatized by the end of the decade. Ironically, privatization was the first step towards the ultimate loss of control over the company by Young and his team. They managed to keep the company going after the groundfish moratoria of the early 1990s, importing raw material and keeping as many plants going and as many people employed as possible, thereby fulfilling as best they could what they considered to be their social contract with government and the people of the province. This did mean, however, that they did not necessarily give primary consideration to the “bottom line” and shareholders’ interests, which is the norm for capitalist enterprises. Despite the stipulation that no shareholder could own more than 15 per cent of the shares of the corporation, privatization had opened up the possibility of a corporate takeover.

41 The takeover was spearheaded by John Risley, CEO of Nova Scotia-based Clearwater Fine Foods. Clearwater’s first attempt, in 1999, failed as the government of the day strictly enforced the 15 per cent stipulation. Nevertheless, Risley persisted, and by 2001 he and his partners, Icelandic Seafood and the Newfoundland fish company, Bill Barry Group of Companies, had gained control of 40 per cent of FPI shares. Risley also attracted prominent Newfoundlanders, notably John Crosbie, to his cause, and at a board meeting in May of 2001, 82 per cent of the FPI board voted in favour of a corporate takeover, with the expectation that the company would become more profitable under a new management regime. Newfoundlander Derrick Rowe, a proven business leader, was appointed as the new CEO of FPI. Rowe was quoted as saying: “We need to communicate to the employees that this is a positive change for the company; things are going to be fine.” He also noted, “It’s a stability issue now, all this is behind us. We need to take care of our employees and our customers.”19 Subsequently, Rowe continued to speak positively but was careful to add the telling proviso that the company’s favourable prospects depended on resource availability and market conditions.

42 Not surprisingly, these conditions turned out not to be so favourable, and by the time Danny Williams became Premier, FPI found itself in serious financial difficulties. The company turned to the provincial government and argued that the only way it could avoid bankruptcy was for the government to rescind the 15 per cent rule and allow the company and/or its assets to be sold to the highest bidder. This led to a prolonged and passionate debate within the provincial House of Assembly. Williams and his government were caught between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, giving up on the 15 per cent rule meant giving up on Newfoundland and Labrador’s largest fish company, which had become one of the largest suppliers of seafood in North America. On the other hand, stubbornly refusing the company’s request would likely lead to bankruptcy, which in turn would have created all sorts of problems for the government and the province’s fishing communities.

43 One possibility would have been for the government itself to buy the company and run it as a Crown corporation as it had been initially during the early to mid-1980s. As we have seen above, Williams did indeed consider this for the marketing arm of FPI, but was dissuaded when he couldn’t convince local processing companies to participate in creating a co-ordinated marketing agency for the Newfoundland and Labrador fisheries. Williams conceded: “We cannot control the actions of a company and what its board of directors can do.”20 He recognized that their real aim was to strengthen FPI enough for it to be sold off.

44 The government reluctantly passed Bill 41, An Act to Amend the Fishery Products International Act, and what had been one of the greatest success stories in the history of the Newfoundland and Labrador fishing industry was lost to the province. The harvesting and processing side of the business was bought by a Newfoundland company, Ocean Choice International, but the marketing arm was bought by High Liner Foods Incorporated based in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. Ironically, the name “Fisheries Products International” persists to this day, but it now refers to a division of a subsidiary of High Liner called High Liner Foods (USA) Inc. based in Danvers, Massachusetts.

Business and Economic Diversification

45 In their book examining the contention that premiers in Newfoundland and Labrador are all-powerful, Marland and Kerby conclude that “the premier’s power is more limited than many people think.”21 Given the limitations of what even a hard-working premier can do alone, Williams, like all other premiers, had to depend on other members of his team: “You have to rely on your ministers, you have to rely on your bureaucracy. You have the ability to appoint your key deputy ministers, but some of it is the hand you’re dealt with, and with that comes some good cards and some bad cards. That’s how the democratic system works, it’s very different from running your own business.”

46 In an attempt to have at least some control over business development, where he could confidently call on his own knowledge and experience, Williams established a Department of Business that would focus specifically on business development and complement the more general economic development mandate of the established Department of Innovation, Trade and Rural Development. Williams recruited from outside of government in the person of Ms. Leslie Galway, who had a business background, to serve as the deputy minister of the new department. Initially, Williams had her report directly to him. The department focused first on developing a new, upbeat brand for the province and on reducing red tape within the bureaucracy. After two years, Williams decided to appoint a separate Minister of Business, and the department focused more on efforts to attract businesses from outside the province to move to or set up branch offices in Newfoundland and Labrador.

47 Although he was interested in economic diversification, this was not a priority issue that Williams took on personally. Instead, he appointed Kathy Dunderdale as his first Minister of the Department of Industry, Trade and Technology, which they renamed the Department of Innovation, Trade and Rural Development (INTRD).

48 Dunderdale was able to hire some excellent people, notably Dennis Hogan to become the first Assistant Deputy Minister of Innovation, thereby fulfilling half of the blue-book commitment to establish a Chief Information/Innovation Office for the province. Hogan took the lead in working with the private sector and educational institutes to produce an innovation strategy for the province.22 INTRD also took the initiative in developing the government’s broadband initiative, which leverages government’s own broadband needs to extend broadband capability to most regions of the province; instituted and funded a Comprehensive Regional Diversification Strategy; and funded a $3 million Industrial Research and Innovation Fund “designed to encourage research into clusters of excellence such as marine technology, pharmaceutical research, biotechnology, and the oil and gas industry”23 to support applied research and development in support of economic development initiatives. This was later expanded and set up as a separate Crown agency called the Research and Development Corporation.

49 Dunderdale’s other main thrust was to reinvigorate and strengthen the department’s programs of support for small business enterprises and rural development. In its 2005 budget, the government announced the establishment of a $10 million Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Fund as well as a $5 million Regional/Sectorial Diversification Fund.

50 INTRD became the lead agency within government for fostering the growth of emergent sectors outside the province’s resource industries. In 2004, the department developed a Marine Technology Development Strategy for the province, with a commitment of $1.5 million over five years to help implement the strategy. Other sectors of focus were environmental industries and information and communications technologies (ICT), where the department worked closely with the respective industry associations, the Newfoundland and Labrador Environmental Industries Association (NEIA) and the Newfoundland Association of Technology Industries (NATI), respectively. Another emergent sector was aerospace and defence. In 2004–05, the department identified more than 30 companies employing approximately 1,000 people working in this sector, generating annual sales of approximately $80 million.24

51 It is difficult to determine how effective these initiatives have been in helping diversify the province’s economy; but it is noteworthy that the provincial economy has become more diversified over the years, which is important given the recent decline in its oil and gas industry.

Poverty Reduction

52 In addition to its efforts at economic development, the Williams government also emphasized the importance of social development. For example, it recognized the legitimacy of same-sex marriages in December of 2004, and negotiated the New Dawn Agreement with the Innu Nation of Labrador in September 2008 that included three elements: a land claims agreement-in-principle, compensation for the negative impacts of the Upper Churchill project on the Innu, and an impacts and benefits agreement for the Lower Churchill project.25

53 The regime’s claim to be socially progressive is best supported by its commitment to poverty reduction in Newfoundland and Labrador. In 2003, the province had the second highest rate of people living in poverty of all Canadian provinces.26 In a section entitled “Eradicating Poverty and Social Exclusion” in their 2003 party platform, the PCs stated as follows:

Based on a research program and consultations with labour and business organizations, as well as consultations with people living in poverty, the government produced a poverty reduction strategy in June 2006,28 taking a long-term, comprehensive, and integrated approach to poverty reduction. Over the years, it took several measures aimed at reducing poverty, each of which was supported by funding targeted specifically to prevent, reduce, and alleviate poverty. Some of the specific action items included raising the minimum wage, increasing income support payments, reducing the costs of schooling (e.g., by providing textbooks at no cost and improving nutrition through the Kids Eat Smart program), and removing disincentives for people on income support to join the workforce (e.g., by extending the Low Income Prescription Drug Program to cover all low-income families, not just those on income support). In all, as reported in the 2014 Progress Report, over 100 discrete actions had been taken in support of the poverty reduction strategy, with more than $170 million budgeted for poverty reduction initiatives.

54 Was the poverty reduction strategy successful? The answer is that, yes, it was, and impressively so. During the period 2003–11, Newfoundland and Labrador went from being the Canadian province with the second highest rate of poverty in the country, at 12.2 per cent, to being tied with Saskatchewan as the province with the second lowest rate, at 5.3 per cent. The latter was significantly lower than the overall Canadian rate of 8.8 per cent. In Newfoundland and Labrador, the number of people with low incomes in 2003 was 63,000. This had fallen to 27,000 by 2011.29 This improvement continued during the immediate post-Williams years such that, by 2013, Newfoundland and Labrador had achieved the goal set in 2003 of being the province with the lowest level of poverty in Canada as measured by Statistics Canada’s low income cut-offs.30

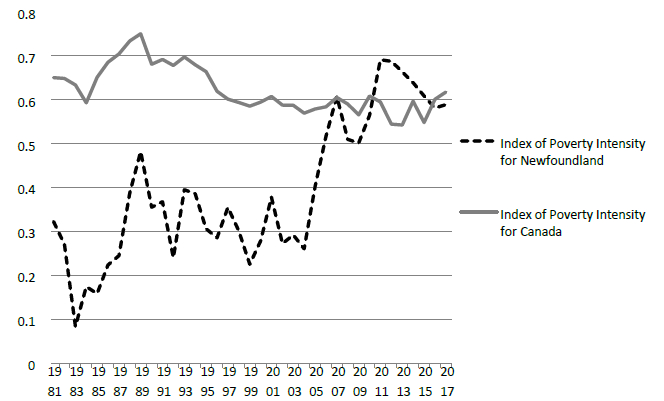

55 An independent academic analysis conducted under the auspices of the Ottawa-based Centre for the Study of Living Standards confirms, in a rather more sophisticated index that they call Poverty Intensity, that the situation in Newfoundland and Labrador improved impressively during the first decade of the 2000s. As Figure 2 shows, the Index of Poverty Intensity was very low in 1983 (the lower the score, the higher the level of poverty intensity), improved somewhat by the late 1980s, worsened again after the groundfish moratoria, but then improved dramatically to be better than the Canadian average by 2012. The success of the poverty reduction strategy was a significant achievement.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

The Strategic Partnership and Labour Relations

56 The public-sector strike during Danny Williams’s first year as Premier inevitably meant that his relationship with organized labour got off to a rocky start. Over the next several years, however, as financial and economic conditions improved, this was to change. In the spring of 2004, Williams, accompanied by Kathy Dunderdale and some senior public servants, embarked on a goodwill and fact-finding visit to the Republic of Ireland. Williams, with his Irish Newfoundland roots, was well received and fêted and dined in Ireland. While there, he learned about the success of the Irish Tiger economy during the 1990s and early 2000s.

57 Williams was impressed by what he learned about the Republic’s social partnership of labour, business, government, and the community sector, which had played a key role in the impressive turnaround and growth of the Irish economy during the 1990s.31 Back in the early 1990s, Newfoundland and Labrador had established its own Strategic Partnership initiative, but, despite undertaking some fine research on various indicators of competitiveness, the Partnership was experiencing a lull at the time. Williams encouraged strengthening the Strategic Partnership.

58 The deputy minister (DM) of INTRD took over as chair of the Partnership. The president of the Federation of Labour (at first Reg Anstey and later Lana Payne), the chair of the Business Coalition (at first Denis Mahoney and later Roger Flood), and the DM formed an executive committee. Premier Williams agreed to meet with it regularly to discuss the Partnership and what its members viewed as being the major issues of the day. He also agreed to arrange annual meetings for the full board of the Strategic Partnership with him and a select number of his senior ministers and deputy ministers. Williams found this informative, and it was also of benefit to him politically as a means to consolidate his ties to the business community and also improve his relationship with organized labour.

59 One of the major strengths of the Strategic Partnership was that it served as a forum through which each of its members could engage in dialogue, become better informed about key issues facing the province, and learn about the reasons behind the other partners’ points of view. An important side benefit was that people came to know and respect each other in an informal way and develop contacts that could be helpful in dealing with issues as they emerged. This was particularly important for the labour representatives. It gave them access to government ministers and officials they would not otherwise have had. As Lana Payne explains:

60 Williams’s relations with organized labour improved over the time he was in office. He and Reg Anstey, who had been openly critical of Williams during the public-sector strike, became more respectful of each other through the Strategic Partnership. After Anstey retired and was succeeded by Lana Payne as president of the Newfoundland and Labrador Federation of Labour, Williams supported Anstey’s appointment to the board of directors of the Canada/Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Directorate. Payne also got to know Williams through the Strategic Partnership and felt comfortable dealing with him directly on various issues. Although they often disagreed, Payne appreciated that he was approachable and willing to give her views a fair hearing.33

Popularity and Leadership

61 Except for a dip during his first year when he legislated public servants back to work, Danny Williams maintained very high ratings throughout his tenure. Before the 2007 election, his personal popularity was at 75 per cent, and it continued to reach even higher levels, to over 80 per cent just before he announced his retirement from politics in 2010.34 Williams was flamboyant and dramatic. After he ordered the Canadian flag to be taken down from provincial government buildings, Paul Martin capitulated on offshore revenues. As the price of oil continued to rise, the province’s need for equalization was eliminated and, as noted earlier, for the first time in its history Newfoundland and Labrador became a “have province” within the Canadian federation. Most Newfoundlanders attributed the new affluence to Danny Williams rather than to the fortuitously rapid rise in oil revenues during the 2000s.

62 Good fortune was not the only reason for Williams’s popularity. As a successful lawyer and businessman, Danny Williams was already popular before he entered politics. Indeed, this is the main reason why, once he declared his candidacy, it was all but a foregone conclusion that he would become Premier. Although born into a professional family in St. John’s, he did not inherit most of his wealth but became a successful self-made multi-millionaire. Williams was comfortable in all social circles: he could sit at boardroom tables as an equal with corporate executives, but was just as comfortable playing recreational hockey with his buddies. Although born and raised in St. John’s, he enjoyed travelling around rural Newfoundland and coastal Labrador. He was seen as down-to-earth and by no means a stuck-up townie. Not only did he first win a seat in a by-election in the west coast district of Humber West, but he continued to represent that district throughout his time in office. Like Joey Smallwood during his prime, for most Newfoundlanders Danny could do no wrong.

63 Popularity, however, is not the same as leadership. What are the characteristics that distinguished Danny Williams as a leader? He was not a great orator in the tradition of Joey Smallwood and John Diefenbaker, but he did come across as sincere and passionately committed to Newfoundland and Labrador and its people at all levels. Some people have criticized Williams for being too dictatorial, too much like Joey Smallwood in his style of autocratic leadership.35 Yet Williams was keen to build a strong team, including cabinet ministers, policy advisors, and senior public servants. He believed in the democratic system, and worked extremely hard to win his majority governments in fair elections. Although at times frustrated by the goings-on in the House of Assembly, he respected his Liberal and New Democratic opponents and the important role they played in political debate. At cabinet meetings, he allowed all his ministers to express their views openly and freely. At the same time, as the undisputed leader, he had his own opinions and his own preferred outcomes to the discussion. In the final analysis, as Premier he had the final say, and this was generally accepted as legitimate by his cabinet colleagues.

64 There were some exceptions. Most notably, one of his high-profile ministers, Beth Marshall, resigned from cabinet early in Williams’s first term when he decided to intervene in a Victorian Order of Nurses strike while Marshall was in Alberta, even though they had previously agreed not to intervene.36 Later, former Premier Tom Rideout was to resign over a dispute about the transportation budget allocation for his constituency.37 On the whole, however, as Matthew Kirby has demonstrated, the rate of exit from Williams’s cabinets was lower than for most previous premiers, and “Williams may have been highly protective of his ministers, much more so than his predecessors.”38

65 Williams also stressed the importance of strategic planning. Not only was the party’s platform for the 2003 election exceptional in that it really did guide the government’s actions for the subsequent eight years, but Williams also insisted on their taking a strategic approach to planning across a whole plethora of government initiatives. Examples include an innovation strategy, a white paper on post-secondary education, a skills task force report, a northern strategy for Labrador, a climate change action plan, an air access strategy, a long-term tourism vision and plan, the government’s broadband initiative, and the poverty reduction strategy. In addition, the Williams government required every department and agency to develop and submit five-year plans with annual updates and justifications for their proposed expenditures. All of these planning and strategic initiatives gave a sense of purpose and direction to the ministers, deputy ministers, and public officials throughout government.

66 One of Danny Williams’s most striking characteristics as a leader was that he was decisive. When unforeseen problems arose, such as a hormone receptor test disaster where many women with breast cancer were incorrectly diagnosed, he immediately took steps to set up an independent inquiry and to see to it that its findings and recommendations were acted on expeditiously. When a senior minister was found guilty of misusing public funds, he had no hesitation about firing him. When several members of the House of Assembly were found to be misusing their constituency allowances, he insisted that they pay back the money and established an independent commission under Justice Derek Green to investigate and make recommendations, which were acted on by government to guard against similar problems in the future.

67 By his own admission, Williams hated to lose. In his closing speech to his supporters when he announced his retirement, he drew laughs and applause when he told them: “you know, I laugh when some critics and reporters say that I’m nothing more than a fighter, someone always looking for a racket, never happy unless I’m taking someone on. Well, folks, I’m here to tell you that those people are right!” In his book about Williams and his battles with Ottawa over oil and gas revenues, Bill Rowe, who was the province’s representative in Ottawa at the time, wrote that Williams’s obsessive drive to succeed in amending the Atlantic Accord was irresistible.39

68 This win-at-all-costs/hate-to-lose attitude was, however, a two-edged sword. It held Williams in good stead in his dealings with Ottawa and the major oil companies over offshore oil revenues. But the same attitude led Williams into some excesses as well. He was incensed when the then president of Memorial University of Newfoundland, Axel Meisen, attended a Liberal convention and when Meisen opposed Williams’s intention to establish Grenfell College in Corner Brook as a separate university. When Meisen resigned, Williams opposed the appointment of Eddie Campbell as president, because he felt Campbell had been too close to Meisen and his opposition to Williams’s hopes for Grenfell, this despite Campbell being a Newfoundlander, which would have accorded with Williams’s maxim that we needed to become “masters in our own house.”40 Williams claims that he never intended to control the appointment of the new president himself, but just “wanted to prevent the succession that was just happening that all the old boys are going to keep somebody in there, one of their own to perpetuate things. I felt that we needed a whole new look in there.” This intervention by the Premier and Minister of Education was anathema to academics who cherish academic freedom from political interference as a sacred principle. In the words of one of its political scientists, “not only did the government do the wrong thing but also they did the wrong thing in a very inept manner.”41

69 This hate-to-lose attitude also characterized Williams’s behaviour towards Stephen Harper. In the lead-up to the 2006 federal election, Harper had promised to remove non-renewable resource revenues from the equalization formula. But when he won the election Harper modified his position and put a cap on how much the province could earn. This incensed Williams. In a meeting in Gander in 2006, Williams raised this issue with Harper and also solicited Harper’s support for legislating a time period beyond which a proven offshore oil development would revert to the Crown if the operator failed to implement the development. According to Williams, Harper got angry and used foul language, to which Williams replied in kind. In a somewhat different version of events, Harper’s chief of staff at the time claims that the dispute was about equalization and that “Williams’s talk descended into foul language.”42

70 In retaliation, Williams led an ABC (anything but Conservative) campaign leading into the federal election of 2008. The ABC campaign was successful in a narrow sense — Harper’s Conservatives failed to win a single seat in Newfoundland and Labrador and their share of the vote fell from 42.7 per cent in 2006 to just 16.5 per cent in 2008;43 but this also meant that the province had no representative in the federal cabinet for most of Harper’s tenure.44 As Raymond Blake points out, Williams failed to nourish the kind of provincial premier/federal minister partnership that had worked so well for Joey Smallwood/Jack Pickersgill and Frank Moores/Don Jamieson — or even, somewhat more rancorously, Brian Peckford/John Crosbie and, later, Clyde Wells/John Crosbie.45 Instead, Williams was very critical of the two Newfoundland and Labrador federal ministers who served during his premiership. He was scathing about John Efford’s supposed weakness on the Atlantic Accord renegotiation, as he was about Loyola Hearn’s failure to insist on Canada extending its offshore management regime beyond the 200-mile limit to include the nose and tail of the Grand Banks. Both ministers refused to break with cabinet solidarity, something that Williams would not have brooked in his own cabinet.

71 Williams bristled at being criticized. He chastised reporters and talk show hosts who offered alternative views to his own on such topics as the province’s dependency on the oil industry and the proposed Lower Churchill hydroelectric project.46 This created an atmosphere that several commentators compared to the heyday of the Smallwood regime back in the 1950s and 1960s. According to Jerry Bannister, for example, “like the Smallwood era, the current period of Conservative government has also seen a palpable fear of retribution for speaking out politically in St. John’s.”47 Williams tended to equate criticism with being unpatriotic, most notably when respected public figures such as former deputy ministers David Vardy and Ron Penney dared to criticize the Muskrat Falls hydro project.48

72 Danny Williams’s hate-to-lose attitude also coloured his approach to the Lower Churchill hydroelectric project.

An Energy Plan

73 Newfoundland and Labrador is blessed with abundant energy resources — mainly oil and gas, wind and hydroelectricity. How should that potential be best realized to serve the people of the province? The Williams government decided to produce an energy plan to address this question. Work began in November 2005 with the release of a discussion paper followed by public consultations around the province. The government also received 86 formal submissions and engaged Wood McKenzie to provide information about the international context of energy developments. The general consensus was that energy prices would continue to rise over the period 2016 to 2041, when the Upper Churchill contract was due to expire. At the time, the shale oil and gas deposits in the United States had not yet been developed, and global concerns about the negative impacts of hydrocarbon production on climate change were not as prevalent as they were to become. The energy plan was released at a time of great optimism in Newfoundland and Labrador, at about the mid-point of Danny Williams’s tenure as Premier.

74 Looking to the future, the central idea of the energy plan was to use the substantial revenues the province expected to gain from its non-renewable oil and gas resources to fund the development of its renewable energy resources, wind and hydro but primarily the latter, to ensure the long-term, sustainable supply of energy for the province. Unlike in the past, the province itself would be the owner and the controller of its renewable energy industry:

As Newfoundland and Labrador’s renewable electricity resources will be the foundation for a sustainable economy, the province will maintain control over them. Once our investments in renewable generation projects are recovered, they can produce electricity at very low cost. Through ownership, the people of the province will be the principal beneficiaries.

Through these actions, we can deliver a clean, secure supply of electricity, a lasting stream of economic benefits and a sustainable future for the people of Newfoundland and Labrador.49

75 Although other energy sources are discussed in other sections of the energy plan — wind, offshore natural gas, small hydro projects — the development of the Lower Churchill hydro project was the main focus. The demand for energy in the province was expected to continue growing (implying that the various conservation efforts discussed elsewhere in the report would have little impact) and that this would necessitate the development of the Lower Churchill project:

While statements at various points in the energy plan indicate that the decision to proceed with the Lower Churchill was still tentative, the deck was clearly stacked in favour of the Lower Churchill by 2007. This was to be the jewel in the crown of Newfoundland and Labrador becoming “masters in our own house,” just as the nationalization of hydroelectricity, under the rallying cry Maîtres chez nous!, was for the Quebec Liberal government in 1962. To take the lead in the implementation of its energy plan, the Williams government established a powerful Crown corporation, later named Nalcor, in June 2007.

Muskrat Falls

76 In his book about relations between Ottawa and Newfoundland and Labrador, Raymond Blake uses a quote from Danny Williams for the title, Lions or Jellyfish: “I would rather live one more day as a lion than ten years as a jellyfish.” Blake concludes his chapter about the Williams government with the favourable overall assessment that “Williams left office with a considerable list of accomplishments.”51 Curiously, however, Blake plays down Williams’s support for the Muskrat Falls hydroelectricity project. Just a week before he announced his forthcoming retirement, Williams and Nova Scotia Premier Darryl Dexter proclaimed with great fanfare that the Lower Churchill project would go ahead.

77 It seems to be a mean trick of fate, but most of those who have served as Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador since Confederation ended their term of office on a low note. For Smallwood, it was the disastrous Upper Churchill contract, for Peckford the Sprung Greenhouse fiasco, for Tobin it was breaking his promise to serve out a second term of office in order to pursue his political ambitions in Ottawa. Danny Williams seemed to have been an exception to the rule. He was still riding high as the most popular premier in Canada when he announced his retirement from politics. Even though it proceeded after Williams had stepped down, the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project, which has dominated political discourse in the province during the past decade, will continue to affect Williams’s reputation and legacy in the long term, much as the Upper Churchill hydro project has affected Joey Smallwood’s legacy.

78 The main emphasis of this article has been on the Williams government during his time as Premier. This is not the place for a lengthy and detailed review of the Muskrat Falls project. But, because of its overriding significance, I will discuss it in a summary way here.

79 In May of 2010, Quebec’s energy regulator rejected Nalcor’s application to transmit power from a proposed Gull Island project via Quebec’s energy grid. Unable to negotiate what it would have considered to be a fair agreement with Quebec for developing the larger Gull Island project on the Lower Churchill, the Williams government determined to develop the smaller Muskrat Falls project in a way that would avoid Quebec altogether. It would transmit power overland and by subsea cables to the island of Newfoundland. This would provide the island with a reliable source of clean, renewable energy that could operate in perpetuity, guaranteeing a secure supply of energy to residents. It would have the further advantage of replacing the Holyrood generating station, which relied on imported non-renewable oil and was responsible for emitting large quantities of hydrocarbons and other emissions that contributed to global warming. This sounded good in principle and the project had a lot of support initially. As it has proceeded, however, many problems, including cost escalation, production problems, management deficiencies, and environmental issues have emerged to undermine public faith in the project. Ironically, given Danny Williams’s determination that, unlike the Upper Churchill project, Quebec would not be the primary beneficiary this time around, it now appears that Newfoundland and Labrador’s other neighbouring province, Nova Scotia, may be the main beneficiary of this project by gaining clean energy at a lower price to its consumers than that to be paid by their Newfoundland and Labrador compatriots. The projected cost of the project has escalated from $6.2 billion to almost twice that amount, meaning that, without some sort of rate mitigation, island Newfoundlanders could see their power bills nearly double from around 12 cents to around 23 cents per kilowatt hour.

80 The project has also contributed significantly to the provincial government’s indebtedness. After the Muskrat Falls project received the green light in 2012, the proportion of the provincial budget earmarked for the resource sector suddenly increased dramatically. Throughout the 2003–10 period expenses under the resource sector were just 4–5 per cent of total expenses, but for the 2011–12 budget year the actual percentage attributed to the resource sector shot up to 20.4 per cent, a huge increase over the original estimated budget allocation of 4.4 per cent. This dramatic increase undoubtedly reflects the government’s investment in the Muskrat Falls project through Nalcor.52 Investigative journalist Russell Wangersky estimated government’s investments in Nalcor in 2015, finding that “the number’s truly spectacular — $2.5 billion pumped into the warehouse in just eight short years.”53

81 In 2017 then Premier Dwight Ball announced the establishment of a Commission of Inquiry Respecting the Muskrat Falls Project under Justice Richard LeBlanc. LeBlanc ran an exhaustive process of conducting hearings, receiving submissions, and reviewing related literature and documents. LeBlanc submitted his report on 5 March 2020.54 The report is very critical, as its title, Muskrat Falls: A Misguided Project, indicates. At time of writing, the Muskrat Falls hydro project is still not complete, problems continue, the cost continues to rise, people are worried about their electricity bills, and, with a sharp decline in oil revenues, the provincial government is facing a fiscal crisis.

Conclusion: A Dynamic Leader for a Dynamic Decade

82 The escalating costs, time delays, and many legitimate criticisms of the Muskrat Falls project have called into question what was otherwise viewed as Danny Williams’s highly successful and popular tenure as Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador. Whether or not Williams, with his greater understanding of business practices than his successor, Kathy Dunderdale, would have sanctioned proceeding with the project in 2012 is a moot question. Certainly, he has been unstinting in his continued support for the project, and he has argued that, in the long run, it will prove to be advantageous to the province and to the country. For present purposes, it is important to acknowledge the problems of Muskrat Falls, but also to balance this against the substantive accomplishments of Williams and his government during the previous seven years.

83 Of all Newfoundland and Labrador’s premiers since Confederation in 1949, Danny Williams was undoubtedly the most fortunate. His timing could not have been better. After a rough start and a genuine but tough approach to begin to get the province’s financial house in order, which occasioned a public-sector strike and back-to-work order in early 2004, the price of the province’s oil increased dramatically and remained high throughout Williams’s tenure. The price of oil increased from $35.91 a barrel in 2003 to $102.49 in 2008. Provincial government revenues increased from $4,836 million in 2003–04 to $8,685 million in 2008–09, with government enjoying a healthy surplus of $2,330 million in the latter year.

84 This positive picture was not due only to good luck. It was also due in part to Williams’s successful negotiation of an advantageous Atlantic Accord Agreement in 2005 and his negotiation of better terms for the province with the multinational petroleum companies operating off-shore. For the most part, this increase in revenue was spent responsibly. The province’s per capita debt was reduced from $24,154 in 2003 to $15,366 in 2009. Government expenditures did increase as well, but largely to fund important services, including health care and education, and to upgrade the province’s aging physical infrastructure. The large increases in 2008–09 and 2009–10 were in part due to a counter-cyclical attempt to help the province ride out the global recession during those years. Williams also agreed to a generous salary increase for the province’s public servants after 2008, partly to adhere to a pledge he had made to pay them back for the austerity package he had imposed on them in 2004. The Williams government also reduced personal and business taxes in a way that has come to haunt the provincial treasury since the dramatic decrease in the price of oil.

85 The Williams government’s poverty reduction strategy was impressively successful, with Newfoundland and Labrador going from the province with one of the highest poverty rates in Canada to one of the lowest. With respect to business development, through the Department of Innovation, Trade and Rural Development, his government introduced several new programs to support local businesses, especially in rural regions; and the innovation strategy and the establishment of the Research and Development Corporation boosted the province’s emerging technology industry. Intangibly, but nevertheless importantly, Newfoundlanders’ and Labradorians’ pride in themselves and the province’s standing within the Canadian federation rose perceptibly during the Williams years.

86 On the other side of the ledger, Danny Williams also had his failures and setbacks. He was unable to contribute to the province’s fisheries development, with his government’s proposed resource-sharing program rejected by fish harvesters, and his attempt to establish a co-ordinated fish marketing organization rejected by the processing companies. In addition, sadly, his government felt it had no choice but to agree to the final dissolution of the once proud Fisheries Products International. During Williams’s time in office, two of the province’s three pulp and paper mills shut down due to world market forces, and the Williams government, despite its “masters in our own house” mantra, was powerless to stop them.

87 Danny Williams’s hate-to-lose attitude proved to be a two-edged sword. It stood him in good stead in dealing with Paul Martin and the oil industry. But it also caused him to interfere in a non-productive way in the selection process for a new president for Memorial University. He was unable to have the same success with Prime Minister Stephen Harper as he had had with Paul Martin. He was frustrated and enraged by Harper’s refusal to honour his campaign promise to exclude non-renewable resource revenues from the equalization formula; and Williams’s subsequent ABC campaign in 2008 resulted in Newfoundland and Labrador having no representation in Harper’s cabinet. Some have argued that this same refusal-to-lose attitude also contributed to Williams’s decision to support the Muskrat Falls project via the inter-island route. Given the historical record of one premier after another being unable to negotiate a fair deal with Quebec, this is perhaps understandable. But there is no doubt that Williams was overly optimistic in his assumptions about the cost of the project and its time frame, as well as regarding projections about both domestic and export demand for the hydroelectric energy from Muskrat Falls.

88 The Williams government’s approach to how to develop the Muskrat Falls project was undoubtedly also coloured by its determination to be “masters in our own house.” Unlike the Upper Churchill project, which, despite its faults, was undertaken by Brinco, a private-sector consortium, at no cost to the provincial treasury, the Williams government’s decision to go it alone through its newly established Crown corporation, Nalcor, was a fateful decision that has landed the provincial government and its taxpayers with a massive financial burden. Ironically, this project, which he championed at the end of his tenure, threatens to undermine the very pride of his people that Williams strove to champion, not to mention his own long-term reputation as one of the province’s most successful and popular premiers.

89 Looking back on it, the decade of the 2000s, with Danny Williams as its dominant figure, was indeed a dynamic decade.55 For the first and only time in its post-Confederation history, Newfoundland and Labrador became a “have” province within the Canadian federation. The age of Newfie jokes was over. The province and its dynamic Premier were respected on the mainland. It became a desirable place to visit, with tourists from other provinces and other countries coming to appreciate the landscape, lifestyle, and culture of Newfoundland and Labrador. Whether that, or the ill-fated Muskrat Falls project, becomes the main legacy of Danny Williams’s premiership remains to be seen.