Reasearch Note

“. . . the Fishing Room and Meddow Gardens and Meddow Ground”:

Landownership at the Cupids Cove Plantation, 1610–2010

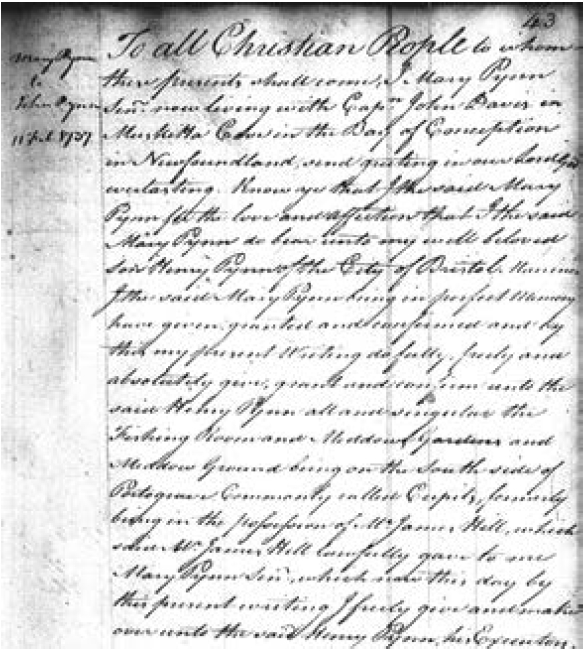

1 On 11 February 1737 Mary Pynn, who at the time was “living with Cap[tai]n John Davis in Muskitta Cove in the Bay of Conception in Newfoundland,” signed her name to a document. Addressed to John Pynn, who may have been leaving for or in Bristol, it was a grant in which Mary bestowed “to my well beloved son Henry Pynn of the city of Bristol, Mariner . . . the Fishing Room and Meddow Gardens and Meddow Ground being on the South side of Portograve, commonly called Cupits formerly being in the possession of Mr. James Hill, which said Mr. James Hill lawfully gave to me Mary PynnSen[io]r” (Figure 1).1 This is not a new discovery. The document was found, transcribed, and posted on a Newfoundland genealogical website by Susan Snelgrove, where it remained unnoticed by most researchers for a number of years.2 I first became aware of it in February 2019 when Lloyd Kane found a transcription online and contacted me. 3

2 One hundred twenty-seven years earlier, in February 1610, a group of London and Bristol merchants, led by John Slany and John Guy, submitted a petition to the Privy Council requesting a charter to establish a colony in Newfoundland. Three months later, on 10 May, James I issued a charter to “The Treasurer and the Company of Adventurers and Planters of the City of London, and Bristol for the Colony of Plantation in Newfound Land,” granting them the right to settle the island. The first colonists, led by John Guy, sailed from Bristol on 5 July 1610 and arrived in Newfoundland in August. Guy had visited the island two years earlier and it seems his initial plan had been to settle at Colliers, Conception Bay. However, at some point this plan was abandoned and the colonists landed nine miles north of Colliers at Cupids Cove. In a letter to Sir Percival Willoughby, written from Cupids on 6 October 1610, Guy explained he had chosen that place over Colliers “for the goodness of the harbour the fruitfulness of the soyle the largeness of the trees, and many other reasons.” The colony they established there was the first permanent English settlement in what is now Canada and the second in North America.4

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

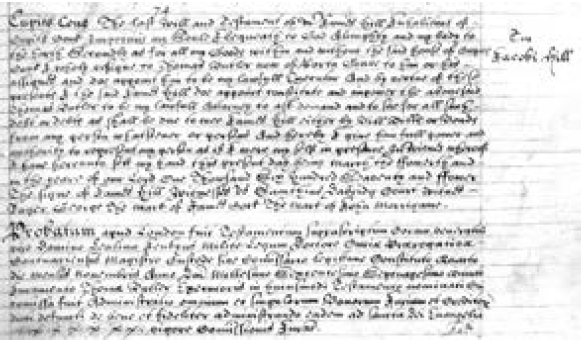

3 The site of the Cupids Cove Plantation was discovered in 1995 during an archaeological survey conducted, under my direction, by the Baccalieu Trail Heritage Corporation and excavations have been ongoing since that time. Prior to the discovery, many historians had assumed the colony had been abandoned after a few years but the excavations, and further documentary research, have shown this not to be the case. The remains of a number of seventeenth-century buildings have been uncovered at the site. Two of these, a dwelling house and storehouse that were among the first buildings erected by Guy’s party, were occupied until about 1670; another building, located just south of the storehouse, was still in use in the 1690s.5 Of the documents that have come to light over the past two decades, perhaps the most significant is James Hill’s will, written at Cupids on 4 March 1674. In it Hill leaves “all my Goods within and without the said house of Cupits Cove . . . to Thomas Butler now of Porta Grave to him or his assignees and do appoint him to be my lawful Executor . . . [and] to be my lawful attorney to ask demand and sue for all such debt or debts as shall be due to mee” (Figure 2).6

4 The earliest reference to a Master Hill being in Cupids Cove is from 1616. In that year, Henry Crout, who was living in the colony at the time, reported receiving “from Master hyll from 10 May to the 4 Iune 2 hundred [weight] of dry fish.” In a series of letters written to Sir Percival Willoughby from Cupids in 1619 and 1620, Thomas Rowley makes a number of references to Master Hill. In one, written on 13 September 1619, he tells Willoughby that “Master hill and I be resolved to goe in the bottome of Trinitie bay about 16 days hence, if it please god” to trade with the Beothuk. In another, dated 16 October 1619, Rowley reports that Master Hill is leaving next week for Trinity Bay and that he can get “more swine . . . [from] Master hill att my pleasure which he hath of his owne.” Four months later, on 8 February 1620, Rowley tells Willoughby that, if he is unable to hire a carpenter to help in building the house he planned to erect at New Perlican, “we shall make means without with master hills carpenters.”7 In another letter, written to John Slany’s brother and business partner, Humphrey, and William Clowberry, from St. John’s on 8 July 1623, Richard Newall reported that Thomas Rowley was arranging to supply Newall with salt cod for shipment to the Mediterranean, some of which Rowley was preparing himself, and “some other w[hic]h he is to receive from Mr Hills at Cupids Cove.”8

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

5 Keeping hogs, employing carpenters, storing and selling salt cod, and making plans to trade with the Beothuk: all this suggests Master Hill was a person of some standing in the colony. I have speculated elsewhere that the James Hill who wrote his will at Cupids in 1674 and the Master Hill living in Cupids in the second and third decades of the seventeenth century were one and the same, and that Hill may have been an agent sent to Cupids by the Newfoundland Company.9 As the company’s agent, one of Hill’s main jobs would have been to procure salt cod and keep it safe in the company’s storehouses until it could be shipped to market in southern Europe. As we have seen, Master Hill was doing just that in 1623. It is generally assumed the Newfoundland Company had ceased to operate by the time its treasurer, John Slany, died in 1632. This may be true, but the markets for Newfoundland salt cod still existed and the sack ships continued to trade. If Hill, an experienced trader, decided to stay on in Cupids, on a developed piece of land with dwelling houses, storehouses, and all the other facilities, it still would have been possible to make a decent living. Indeed, once the company ceased to operate, things may have been better for Hill since he then would have been a free agent. We know that someone still was playing this role in the 1630s: on 17 September 1633, Dutch merchants Hector and Lambert Pietersis purchased 44,400 salt cod at Cupids Cove.10 If we assume Hill to have been a young man of about 20 in 1616, he would have been about 78 when the will was written. Another possibility is that James Hill was the original Master Hill’s son. In either case, James did not live long after writing his will: it was probated in London on 5 November 1675.11

6 From the will it is clear that Thomas Butler inherited more than James Hill’s possessions; he also took control of Hill’s estate. For Mary Pynn to claim to have inherited Hill’s property in Cupids directly from him, she must have been closely connected to Butler: probably his wife or one of his children. The earliest reference we have to Butler is in James Hill’s will, the second is in the 1675 census in which he is recorded as living in Port de Grave, three miles (4.8 km) northeast of the Cupids colony on the other side of Bay de Grave, with his wife and three sons.12 While it is possible Butler’s wife survived him and later married a Pynn, she probably would have been in her mid-eighties, or older, when the grant was written. It seems more likely Mary was Butler’s daughter. The 1677 census records Butler as having three sons and a daughter.13 Since the daughter is not mentioned in the 1675 census, she must have been born sometime between the autumn of 1675 and the summer of 1677. According to the 1681 census, Butler and his wife had only one child living at home that year.14 While we cannot say for certain, this suggests the three sons had moved on to find their way in life, leaving the Butlers alone with their young daughter. If this was Mary, she would have been about 61 when the grant was drawn up: more than old enough to have a son looking to inherit property.

7 The Pynn family can trace its roots in Conception Bay back to the seventeenth century. The 1675 census records a Henry Pynn living in Carbonear with his wife, two sons, and four daughters.15 As prominent planter families in seventeenth-century Newfoundland, a marriage between Butler’s daughter and one of Pynn’s sons would have made a good match and this appears to be what happened. The fact that Mary’s son is named Henry also hints at a connection to the earlier Henry Pynn. The earliest reference to Mary’s son, Henry, I am aware of is from 1713. Customs records report that on 25 February that year “Henry Pinn,” master of the 60-ton “Sun Gally of Topsham,” sailed out of Bristol with 13 men bound for “Newfoundland on a fishing voyage.”16 Fifteen months later, on 12 May 1714, Henry Pynn married Jane Clarke at St. Nicholas Church in Bristol.17

8 Located between Harbour Grace and Carbonear, “Muskitta Cove,” or Mosquito Cove, was renamed Bristol’s Hope in 1904. The Davises were one of two families living in Muskitta Cove in the second half of the seventeenth century. William Davis is recorded living there in 1675 with his wife, four sons, and a daughter.18 As one might expect, the Pynns and the Davises knew each other well: William Pynn from Carbonear and George Davis from “Muskitta” organized the defences of Carbonear Island and fought together to defend it against the French during the winter of 1705.19 When Mary married, any land she owned would have passed to her husband. Since it was Mary, and not her husband, who deeded the land in Cupids to her son, she must have been a widow at the time. Perhaps one of Mary’s daughters married a Davis and this was why, by 1737, she was residing in John Davis’s home. We know that two and a half years later Henry Pynn was in Newfoundland and Captain Davis was in Bristol and on his way back to the island. On 13 June 1739, the Bristol merchant Isaac Hobhouse granted power of attorney to “Captain John Davis of the same city mariner” to recover the debts owed him by “Henry Pynn now at Newfoundland.”20

9 Mary Pynn’s grant survived because it was copied into a later document, written on 12 October 1774, in which Ann Stretch sold Henry Pynn’s property in Cupids to Harbour Grace merchant John Clements for £10.21 Ann Stretch might have remained a shadowy figure had her stepson, George Augustus Pynn, not challenged her right to inherit his father Henry’s estate after his death in October 1750.22 A year before the grant was issued, George Augustus’s mother, Jane, had died. She was interred in the crypt of St. Nicholas church, Bristol, on 23 January 1736, and shortly after, Henry married his second wife, Ann Thistle of Harbour Grace.23 During his life Henry had acquired extensive holdings in Newfoundland and an estate valued at £11,000, or roughly £2,453,000 in today’s currency. His largest holdings were in Harbour Grace, but he also held land in other parts of Conception Bay aside from Cupids. He had fathered at least three children by Jane, including George Augustus, and seven by Ann, of whom six had survived and were in her care. At Henry’s death, Ann took control of the estate and, five months later, married Henry’s clerk, Michael Stretch. However, Henry died without a will, and in 1752 George Augustus took his challenge to the Prerogative Court of Canterbury. Witnesses for the defence argued that George Augustus, referred to simply as Augustus in the court records, was not fit to manage the estate and it was for this reason his father had employed him as a mariner instead of a clerk. It was further stated that Augustus was “a drunken man” who had sworn “he would destroy the whole estate, rather than those who are interested should have any benefit.” Ann told the court that, fearing for her safety, she had “married Stretch for protection against the son.” The judge, Sir George Lee, decided in Ann’s favour, stating “that it had always been the practice to grant administration to the widow, unless some material objection appeared against her,” and adding that, since Ann had six of Henry’s children in her care, “their interests were united to hers, which gave her also a great majority of interests” in the estate.24

10 Like Henry Pynn, John Clements acquired extensive holdings in Conception Bay but his business came to a sorry end when, in 1797, Bridport merchant William Fowler and Bristol merchants John Cave and John Hurle demanded payment of debts owed them. Unable to pay, the 75-year-old Clements declared bankruptcy. It could not have been a large sum that sent his business over the edge: on 31 May 1797 the three claimants agreed to settle their debts for £100 to be paid by Bristol merchant Edward Bulmer, Clements’s partner and son-in-law.25 Clements died in Harbour Grace in February 1802 and two years later, in April 1804, Harbour Grace merchant William Stevenson was given power of attorney to collect the debts owed Clements’s estate.26 It soon became clear Clements’s main problem had been his inability to collect the money owed him. A list of outstanding debts, compiled in December 1805, indicates that the Clements estate was owed £10,183/7s/1½d, about £858,000 in today’s currency, from 119 individuals in Newfoundland. The list valued Clements’s Cupids property at £30.27

11 By 1806 a St. John’s notary public, auctioneer, and conveyancer, George Lilly, had been appointed “The Trusty for the Estate of the Late John Clements” and started collecting debts and selling off property. His skills as a conveyancer were put to work in October 1806 when he took possession of William Anthony’s land in Cupids for debts owed to “the estate of the late John Clements” and sold it to Daniel O’Conner, surgeon of Port de Grave, for £26/10s. Two weeks later he sold Clements’s land in Broad Cove, Port de Grave, to John Squires for £36/10s.28 On 22 September 1807 Lilly entered into an indenture with George Smith of Cupids to sell him “all that piece of ground or plantation and fishing room situated lying and being at Cupids Cove aforesaid and known by the name or appellation of Cupids Plain and bounded or extending from the Western Brook to Dicks Mead as the same was heretofore held occupied and enjoyed by the said late John Clements.” The indenture was for £100, a substantial increase from the £30 it had been assessed at two years earlier, to be paid in five annual installments of £20: the first due “upon or before the twentieth day of October [1807].”29

12 The boundaries and dimensions of all the properties in Cupids in the first decade of the nineteenth century are delineated in the “Return of Possessions Held in Conception Bay,” commonly referred to as the “Conception Bay Plantations Book,” compiled between 1804 and 1806.30 From this document we know the western boundary of Cupids Plain, or “the Plain” as it was more commonly known, was near the western end of the Salt Water Pond at the bottom of Cupids harbour.31 As we have seen, the Lilly–Smith indenture is more specific, stating that the western boundary of the Plain ran along “the Western Brook.” The Western Brook, or West Brook, once flowed from Cupids Pond into the south side of the Salt Water Pond about 44 yards (40 m) east of its western end. Although its course was diverted a number of years ago, and most of it now empties into the Horse Brook farther west, some water still flows underground along its old route and directly into the pond. The original course of the West Brook was one of the clues that helped us locate the Cupids Cove Plantation. John Guy mentions washing in a brook near the plantation in the spring of 1611; and Henry Crout reports that the colonists were catching trout in “our brook hard by the house” in March 1613. In 1995 we uncovered the first traces of the plantation on the western edge of a terrace 65 yards (60 m) east of the brook’s old stream bed.32

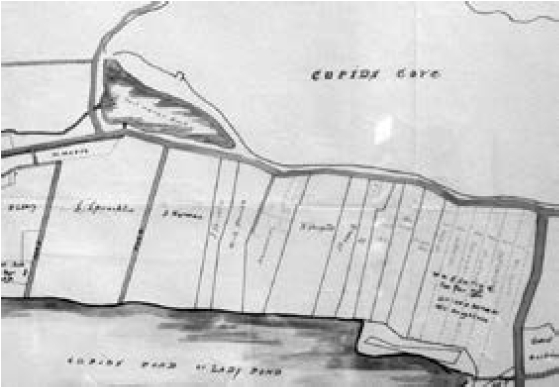

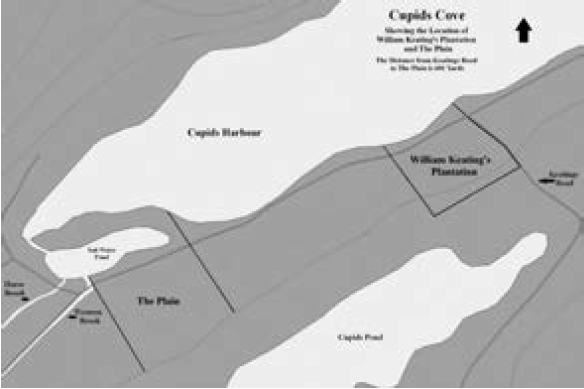

13 In 1793 Brigus merchant and boatbuilder William Keating purchased a plantation in Cupids from the Carbonear and Poole merchants George and James Kemp for £15. We know from the “Plantations Book” and from the unpublished Hearn Map of Cupids, compiled in 1908, that the eastern boundary of Keating’s property was just west of what is now Smith’s Hill at the north end of Keating’s Road (Figure 3).33 According to the measurements provided in the “Plantations Book,” the distance southwest from the eastern boundary of Keating’s property to the Plain was 601 yards (549.5 m). This places the eastern boundary of the Plain on the east side of the road that runs out onto, and extends across, Pointe Beach on the north side of the Salt Water Pond. The “Plantations Book” also states that the Plain extended along the water’s edge from this point for 218 yards (199.5 m).34 Measuring southwest for another 218 yards takes us back to the eastern bank of the Western Brook (Figure 4).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

14 In almost every case, the “Plantations Book” contains detailed information, arranged in columns, on the properties listed. Normally this includes the name and residence of the party claiming ownership, the nature of the claim, and the name of the present occupier. However, in the case of the Plain only the width of the property, the properties bordering it to the northeast and southwest, and the “Date of this Entry” are recorded.35 As Robert Cuff has pointed out, since all the entries in the “Plantations Book” were compiled between 1804 and 1806, the wide range of years listed in the document under the heading “Date of this Entry” cannot refer to the years in which those entries were recorded. Instead, they refer to the years in which the owners at the time the document was compiled entered into possession of their properties.36 The year given for the Plain is 1773 and this almost certainly is a reference to John Clements purchasing the land from Ann Stretch. While Clements purchased the property in 1774, not 1773, a discrepancy of one year is understandable, especially if the informant was relying on memory, or if Clements took informal possession of the land before the final paper work was completed. When the “Plantations Book” was compiled, the Plain was still part of Clements’s estate but Clements had been dead for several years and George Lilly was looking for a buyer. He already may have entered into negotiations with George Smith, but the actual ownership of the property still was unclear. Indeed, since the indenture between Lilly and Smith stipulated that if the latter should fail to make any of his five payments on time, the “bargain and sale shall cease . . . and the before bargained premises and every part thereof . . . shall again revert to, be, and remain to the Estate of the said late John Clements”; ownership of the property, and the date the owner took possession, would remain uncertain until Smith made his final payment in October 1811.37

15 Confusion over the meaning of “Date of this Entry” has led to a number of questionable claims to early land use in Conception Bay, including the claim that the Dawe family was living in Port de Grave by 1595.38 While the entries in the “Plantations Book” for George and Isaac Dawe’s properties in Port de Grave state that they were “Possessed by [their] ancestors for 160 years,” the year 1595 was arrived at not by counting back from when the entries were written down, sometime between 1804 and 1806, but from 1755, the year George Dawe inherited his property from his mother. Counting back from 1804, the earliest possible year the entry could have been recorded, would place the Dawe family in Port de Grave in 1644, not 1595. However, this also may be incorrect. In all, the “Plantations Book” lists eight landowners with the surname Dawe living in the same area, each claiming land “possessed by his ancestors.” A number of them claim multiple plots in different locations, and all of these plots border each other in a confusing patchwork. Of these, only George’s and Isaac’s are recorded as having been in the family for 160 years. The properties of Samuel, John, and Charles Dawe are recorded as having been in the family for 100 years, while those of Nicholas, William, and a second John Dawe are recorded as being in the family for 105 years.39 Since all these landowners probably had a common ancestor, it seems odd that two of the eight would claim an inheritance extending back 60 years further than the rest. And, given that none of the nominal census records from the 1670s and 1680s record any Dawes living in Port de Grave, it seems likely that 160 years is either an error or an exaggeration and that between 100 and 105 years is a more reliable estimate. If this is correct, the Dawe family probably arrived in Port de Grave sometime between about 1699 and 1706.40

16 Whatever George Smith’s plans for the extensive property he purchased in Cupids, he soon seems to have fallen on hard times. Perhaps the burden of the annual payment proved too great. Whatever the case, on 25 May 1813 he sold most of his land, 194 yards bordered “on the east by George Smiths Room [and] on the west by [the] Gutt” to “Samuel Sprackland Junr. Of Brigus” for £70.41 The “Gutt” mentioned in the agreement refers to the entrance to the Salt Water Pond and the area around it, at the pond’s western end. Assuming the measurement of 218 yards given in the “Plantations Book” to be correct, Smith must have retained a piece of land 24 yards (21.9 m) wide — “Smith’s Room” — at the eastern end of the property. Apparently Smith also owned at least some of the land on Pointe Beach. Included in his sale to “Sprackland” were “133 yards of the Beach extending from the east end thereof.” This makes sense: Pointe Beach would have been an ideal place for drying salt cod and likely was considered an essential part of the fishing room. Despite the sale, George Smith’s financial problems continued. A list of the inhabitants of Brigus, Cupids, Bareneed, and Port de Grave, dated 27 September 1817, records that “Samuel Spracklin” of Cupids, with a wife, three children, and four servants, was “well off,” while his neighbour, George Smith, with a wife, seven children, and two servants, was “distressed.”42 Finally, in 1825, Smith sold his fishing room to Spracklin.43

17 The entire Plain remained in the Spracklin family until sometime in the 1830s. Samuel died in 1825 and in 1831 his widow Mary wrote her will. At some point Samuel had divided the property into three fishing rooms, living on one and leasing the other two. Mary left one of these rooms to each of her three children, Simon, John, and Priscilla. Of the three, only Simon was over 21 and eligible to inherit at that time. John and Priscilla were left under the guardianship of Charles Cozens, who occupied another of the three rooms. The third room was leased to “John Bonnell of Cubits.”44

18 Sometime between 1831 and 1842 most of the eastern half of the Plain was acquired by the Norman family. On 6 February 1843 Solomon Norman left his land in Cupids to his wife with the stipulation that, should she die or remarry, it would be “equally divided among my four brothers, that is to say John, William, James & Job.”45 Clearly this must have been a large piece of land; the 1908 Hearn Map shows the Plain divided roughly in half with the Spracklins to the west, the Nor-mans to the east, and a “road” running north to south between them. The remains of this road, known as Tibb’s Lane, or Tibby’s Lane, was uncovered just west of the Norman property line during excavations conducted between 2002 and 2005.46 At the eastern end of the Plain, immediately east of the Norman property, the Hearn Map shows a narrow strip of land, also owned by the Spracklins, which almost certainly was George Smith’s room.47

19 Aside from a narrow strip of land just west of the Norman property, the Plain remained divided between the Spracklins and the Nor-mans until the early twentieth century, after which it was broken up into narrower lots and much of it sold. Two properties remain in the Norman family today: Rodney Norman’s residence immediately east of the Cupids Cove Plantation and Rodger Norman’s just south of the east end of the Plantation. The Spracklins sold their last piece of land in the 1920s. The narrow strip west of the Normans passed to the Ford family sometime after Simon Spracklin’s daughter, Mary Charlotte, married Elias Ford on 8 February 1855.48 It later passed to the Whalen family when Mary Charlotte and Elias’s daughter, Priscilla, married Caleb Whalen on 5 January 1892.49 Priscilla and Caleb’s granddaughter, Ruth Whalen, married Garland Baker in 1972 and Ruth and Garland Baker still owned that piece of land when we began our archaeological survey 1995.50 It was on that narrow strip, about 80 yards (73 m) east of the West Brook, that we made our first major discoveries, uncovering the 1610 dwelling house and storehouse, a section of the enclosure wall, and a number of other important features. Between 2008 and 2010 the Baker property and the properties immediately to the east and west were purchased by the provincial government, and in 2010 that part of the Plain was declared a Provincial Historic Site.

20 James Hill’s will, with which we began this brief exploration of landownership at Cupids Cove, makes no direct mention of land, and it may be that Hill continued to view the land he occupied in Cupids as belonging either to the Crown or to descendants of the merchants who established the colony in 1610. However, whether or not the land was officially granted to Hill, as the last living representative of the Newfoundland Company and someone who occupied the plantation for many years, most would have considered him its lawful owner. As Jerry Bannister has pointed out, despite certain restrictions on ownership, the English common law principle of “prima facie title or a presumption of the right of property in the thing possessed” was usually applied in Newfoundland.51 We know that Thomas Butler, most likely Mary Pynn’s father, was pasturing his sheep and cattle on this land in 1675 and it has been suggested that the plantation may have served as a winter home for Butler and his family after Hill passed away.52 Until now, we had assumed the original plantation had been abandoned after the French raid of 1697 and reoccupied later in the eighteenth century. We knew a planter had returned to Cupids in 1698, that there were at least five year-round residents in 1699, and that a planter, his wife, and child were living there in 1701, but we had speculated that these people had abandoned the original settlement and were living farther out the harbour and closer to the fishing grounds.53 However, this research shows that the site of the original colony was not abandoned in the early eighteenth century. Instead it continued to be valued as a fishing room, pasture, and garden. There can be little doubt Mary Pynn had some understanding of the significance of her claim when she stated that she had inherited the Cupids Plain “lawfully” from James Hill. In evoking Hill’s name, she was claiming title based on a history of use and ownership extending back to the early seventeenth century. We can now trace that history of ownership to the present day.

Postscript

21 The belief that all of Newfoundland’s early colonies were total failures originated with Prowse’s A History of Newfoundland, published in 1895, and has coloured our view of these settlements since that time. Yet Prowse’s statement that “none of the great patentees, from Gilbert to Baltimore, exercised the least permanent influence on the history of the Colony”54 was influenced more by the politics of his time than by an objective reading of the relevant documents. At a time when Newfoundland was struggling to emerge as an independent dominion and assert control over its resources, an origin story based in royal charters and “aristocratic and fantastical patentees” did not fit the tenor of the times. So Prowse dismissed the early plantations as failures and created a foundation myth, with no basis in fact, about “small bands of settlers” who, “amidst the fiercest opposition from the Devonshire ship fishermen” and “for years before Guy’s arrival, [had] been settled on the eastern coast, between Cape Race and Cape Bonavista.”55 The confusion caused by Prowse’s fictional foundation myth still lingers and, on occasion, has caused even professional academics to accept, or at least consider, claims of sixteenth-century settlement.56

22 In reality, permanent European settlement in Newfoundland began with the establishment of the Cupids colony in 1610. While some attempts failed, over the next 20 years investors in that company and patentees who acquired land from it established small settlements at Cupids, Harbour Grace, Carbonear, Ferryland, Renews, and St. John’s.57 By 1630 the total resident population was about 200.58 A report presented to the Council of Foreign Plantations in 1660 stated that there were about 150 English families living on the island that year; and the first census of Newfoundland, conducted in 1675, recorded 1,655 English settlers living in 28 communities on the English Shore.59 King William’s War (1689–97) and Queen Anne’s War (1701–13) resulted in a great deal of destruction in Newfoundland, and the population fluctuated considerably during this period. Still, there is evidence of further population growth. A list compiled for the Council of Trade and Plantations in 1699 records 3,099 year-round residents.60 Life was not easy for these early settlers but, despite what many still believe, settlement in Newfoundland was not illegal. The myth of illegal settlement had its origins in the politics of another era: the early nineteenth century when political reformers on the island promoted it as a means of creating unrest and support for their cause.61

23 The argument that settlement was illegal rests mainly on what has come to be known as the six-mile rule, first introduced in 1637. In that year the Crown dismissed all previous claims to Newfoundland in favour of a new grant of the entire island, the Grant of Newfoundland, to the Marquis of Hamilton, the Earls of Pembroke and Holland, and Sir David Kirke. The main case made by Kirke and his associates when petitioning for the grant was that all the previous proprietors had abandoned the island “leaving divers of our poor subjects in the said province living without government.”62 This was only partially true; the Calverts had left a governor, William Hill, at their colony in Ferryland, whom Kirke expelled when he arrived to take up the role in 1638. But Kirke’s arrival did provide greater security and helped promote further settlement.63 The six-mile rule, which was part of the Grant of Newfoundland and later incorporated into the Western Charter, stated that planters could neither build nor cut wood within six miles of the shore.64 While this may have looked impressive on paper, and probably provided some reassurance to those migratory fishermen opposed to settlement, it is hard to believe Kirke ever took it seriously and it was never enforced. And, as Pope has pointed out, 16 years later, in 1653, the Council of State removed the restriction and recognized “the rights of planters to waterfront property.” The Second Western Charter, issued in 1661, actually promoted settlement by restricting passengers travelling on fishing ships to Newfoundland to “such as are to plant and do intend to settle there.”65

24 However, the matter was not settled. Fearing that if the resident population continued to grow Newfoundland would go the way of New England, where the resident fishery had totally displaced the migratory fishery, fishing merchants in the West Country lobbied for its return. In 1671 they were successful and the six-mile rule was reinstated. The outbreak of the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–74) put matters on hold until 1675,66 but that year the naval commodore sent to Newfoundland to accompany the fishing fleet to market, Sir John Berry, was given orders to “declare his Majesty’s pleasure to all Planters that they come voluntarily away, and that next year his Majesty’s convoys will begin to put in execution the ancient Charter forbidding any Planters to inhabit within six miles of the shore.”67

25 Berry, a native of Knoweston, near Ilfracombe, in North Devon, who was knighted by Charles II for his service in the Third Anglo-Dutch War,68 did more than just inform the planters of the Crown’s decision; he conducted an investigation into the situation. He soon found that not all migratory fishing captains were opposed to settlement. He reported to the Council of Trade and Foreign Plantations that “45 of the chief western masters said that, if the planters were removed, the [fishing] trade would be utterly destroyed” because the French would then proceed “to enlarge their fishery as they please” and “will in a short time invest themselves of the whole [or] at least of Ferry-land and St. John’s where harbours are almost naturally fortified.”69 There was also the fear that, rather than submit to being removed, the planters would side with the French against the English. From a financial perspective, Berry felt that deportation would result not only in hardship for the settlers but also for the parishes to which they would be relocated because, he said, “a labouring man will get in a summer season [in Newfoundland] near £20 and their daily food . . . out of the sea [whereas] such a person would not get £3 in England.”70 And the Crown would also lose revenue. After careful study, Berry estimated that more than one-third of the fish and train oil shipped to market in southern Europe, valued at approximately £46,813, or roughly £10.5 million in today’s currency, was produced by the settlers.71

26 One of the accusations levelled against the settlers was that they lured fishermen away from their ships, “enticing the men to stay behind and neglect their families.” Berry found that, instead, “when the voyage is ended, to save 30s. or 40s. for their passage, the Commanders [of the fishing ships] persuade the Planters to receive them and the seamen to tarry behind.” The residents had also been accused of destroying “stages, flakes, storehouses” and other facilities “for firewood and covetousness of the nails, spikes and bolts.” This Berry found also to be false, reporting that it was the migratory fishermen who tore down these structures at the end of the season rather than have “another enjoy their goods next year.” The captains of the fishing ships used the wood to brew beer for the return voyage and heat their vessels, and sold what remained “of the stages and houses to the sack ships.” In an attempt to stop this practice, Berry informed the ships’ captains that “his Majesty’s Charter forbids that any spike or nail should be drawn, but everything entirely preserved, and he would take particular notice of those who should offend, and acquaint his Majesty therewith.”72 In a letter to Sir Joseph Williamson, written aboard the HMS Bristol in Bay Bulls harbour on 12 September 1675, Berry stated that, in his opinion, all the accusations made against the settlers were false and that he stood “in admiration how people could appear before his Majesty with so many untruths against the inhabitants.”73

27 It was largely as a result of Berry’s actions that the order was reversed. Instead, in 1676 orders were sent out that the six-mile rule would not to be enforced and the Lords of Trade and Plantations would conduct an inquiry into the situation. Violence between migratory fishermen and planters broke out in St. John’s that summer and some property was destroyed. This led John Downing, a prominent planter whose father had settled in St. John’s in 1640, to travel to London, where, on 7 November 1676, he presented a petition to the Lords on behalf of the inhabitants.74 No doubt Downing was speaking for all the English inhabitants in Newfoundland when he declared that they had settled “and lived for many years under the said laws and orders given them and by their industry built houses for their habitation and cleansed the wilderness of the place, whereby to keep some cattle for their sustenance and the support of such of your Majesty’s subjects as come to trade there . . . but now some of Your subjects, pretending your Majesty’s patent and orders for the same, . . . break open the houses of the said Inhabitants at their wills and pleasures contrary to the ancient laws and orders of the said place.”75 In response to the violence, in March 1677 the Lords of Trade and Plantations sent an order to be carried aboard the St. John “now lying at Dartmouth . . . directing masters and seamen fishing this year to forbear any violence to the planters upon pretence of the said charter, and suffer them to inhabit and fish according to the usage of past years.” These orders were declared in 31 harbours in Newfoundland, including “Cupid’s Cove [sic].”76

28 No further attempt was made to enforce the six-mile rule, and in 1680 it was rescinded for the last time when Article 3 of the Western Charter was altered “to allow the planters to live as near the shore as they please.”77 The attempt to remove the settlers was, in any case, reactionary and all but impossible by this time. In reality, by the 1670s Newfoundland planters and West Country fishing merchants had come to depend on each other. The compromise reached, to use Pope’s phrase, was one of “settlement without the settled government.”78 In addition to instructions to allow the settlers “to inhabit and fish according to the usage of past years,” other alterations were made to the Charter in 1680 making life more secure. It was recognized that planters could “keep taverns and public houses” and that “inhabitants shall retain possession of their stages,” and once the migratory crews had constructed the stages they needed that year, the planters could construct more stages “which they shall always possess.” Planters were also permitted “to hire servants in England and transport them to Newfoundland.” In addition, it was ordered that a “Minister, or as many . . . as the planters can maintain be sent . . . to go from place to place to baptize children, &c.”79 The planters’ right to hold property was acknowledged in 1699 with the passage of the Act to Encourage the Trade to Newfoundland, commonly referred to as King William’s Act, which, as Handcock states, secured “the tenure rights of inhabitants to property held in 1685 or before and to property not used as ships’ rooms between 1685 and 1698.”80 While some further attempts were made to restrict property rights in the eighteenth century, they were largely ineffectual.81 It is worth noting that of the 48 properties in Cupids recorded in the “Plantations Book,” 11 were registered as having been “Cut and cleared agreeable” to King William’s Act.82