Article

Newfoundland and the Trade of North Devon Ports in the Seventeenth Century

Introduction

1 Although Charles Kingsley, in his 1855 novel Westward Ho!, sought to portray the sixteenth century as a Golden Age for North Devon, a stronger claim could be made for the seventeenth century as the apogee of maritime enterprise in the area.1 In this century, the Newfoundland trade was at the heart of economic life and closely meshed with other trades, both newly emerging ones and older established trades such as the cloth industry and exchange with France, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain. Grant (1992: 130) notes the establishment of several almshouses in Barnstaple as evidence of the prosperity of the town at this time, to which could be added the elegance of Queen Anne’s Walk, the merchants’ exchange erected in the first decade of the eighteenth century, and, in Bideford, the grand merchants’ houses in Bridgeland Street, built at around the same time. There is general agreement that Barnstaple and Bideford were significant players in the Newfoundland trade, but in almost all accounts they occupy a rather peripheral place compared to the South Devon ports, especially Dartmouth.

2 A primary aim of this paper is to redress the balance somewhat and to set the Newfoundland trade in the context of other maritime enterprise during the seventeenth century, a period when North Devon more than held its own compared to ports such as Dartmouth and Poole in Dorset. Most accounts talk of a series of triangular trades involving Newfoundland, with Ireland, France, and Iberia usually being seen as the other apices. A valid question is whether these were triangular trades involving the same ships and merchants or whether cargoes made more complex journeys. While there is agreement that the Newfoundland trade was central to the economic prosperity of North Devon in the seventeenth century, it is less evident how central it was to the leading merchants and whether the merchants with Newfoundland interests could ever claim to speak for their ports as a whole. This paper will use a selection of the Port Books for North Devon to shed more light on these issues. As will be seen, the Port Books give a rather different picture of the Newfoundland trade from that emerging from the Heads of Inquiry returns that the senior naval officer on the Newfoundland station was to produce each fishing season after 1676.

3 Devon, uniquely among English counties, has two physically separate coastlines, one to the north forming the southern shore of the Bristol Channel and being about 85 kilometres in length, compared to the South Devon coast, fronting the English Channel, of approximately 140 kilometres. Unlike South Devon where harbours are numerous, the combined estuary of the Taw and Torridge offers the only shelter and this can only be entered at high water. Barnstaple lies about 14.5 kilometres up the Taw and Bideford about 8 kilometres up the Torridge. Notwithstanding the smaller size of seventeenth-century ships, the Taw to Barnstaple was not navigable, even at high water on the neap tides, for four or five days each month. As the seventeenth century progressed, Bideford came to eclipse Barnstaple in maritime trade. Gent (2002: 20), using parish registers, estimated the population of Bideford as between 1,700 and 2,000 during the second half of the century and Gray (1998: 17), using similar sources, estimated Barnstaple’s population as around 2,000 in 1600, about the same as that of Dartmouth. Barnstaple had constructed in stone its Great and Little Quays between 1550 and 1600 and at Bideford a stone quay built around 1600 was extended twice in the seventeenth century.

Data Sources and Limitations

4 Maritime trade in the seventeenth century was recorded in Port Books, one for domestic trade within England and Wales, and one for overseas trade, which included Scotland, Ireland, and the Channel Islands as well as mainland Europe and North America. In the sixteenth century, North Devon was included within the Port of Exeter as a sub-port and, during the following century, first Barnstaple (with Bideford as a sub-port) and then Bideford became Head Ports in their own right. A selection of the overseas Port Books covering North Devon has been transcribed and these are used in this paper.2 Bideford contains Clovelly as a sub-port, but the village only participated in coastal trade, although its mariners may well have served on ships engaged in international trade. Barnstaple includes Ilfracombe, which was active in the Bristol Channel and Irish Sea trade but is not separately recorded in the Port Books.

5 The Port Books have a number of limitations, especially with regard to the Newfoundland trade. They contain only records of ships carrying dutiable cargoes and so ships sailing to Newfoundland with gear and provisions for the fishing season do not appear, nor do ships sailing anywhere in ballast. There is evidence of under-recording of all cargoes more generally and Taylor (2009: 19) suggests that Bristol merchants often used North Devon ports to evade the stricter recording of their home port. The entries record the names of ships and usually the names of their masters and home ports. In the absence of any compulsory system of registration, the home port can be confusing and there are instances of a ship being given as from Bideford or Northam, the parish of its deeper water out-port of Appledore, even in the same year. Ship tonnages are frequently recorded, but what is almost certainly the same ship is often given widely different tonnages and, as Farr (1976: 5–6) notes, a range of formulae were in use to calculate tonnage and in any case, it frequently suited the master to exaggerate the ship’s capacity to merchants and to minimize it to port officials. For these reasons, ships’ tonnages are omitted in this study. The ports of origin and destination are given, although these have a variety of spellings and in a few cases are unidentifiable. The cargoes of ships are given in a variety of measurements, making comparison difficult, and the focus of the present research has been on the number of consignments each merchant has of different commodities. Dates are given when details were entered in the Port Book, but it is clear that the clerks sometimes saved up records to be entered at one go and at other times appear to have noted daily when each consignment was unloaded from a ship. The names of merchants are usually given, and in some of the earlier books their place of residence is often given. However, as will be shown, some evidence suggests that not all the merchants recorded were the North Devon importer or exporter of commodities and some must have been the merchants in other ports trading with North Devon. In a few instances, the master was recorded as the merchant, and this was often the case for French ships. Thus, in 1672 Alain Ferrick was both the master and the merchant for the Jacques of Pouldavid near Douarnanez in Brittany, which arrived in June with a cargo of salt and then returned to Brittany with woollen cloth.

General Patterns of Trade

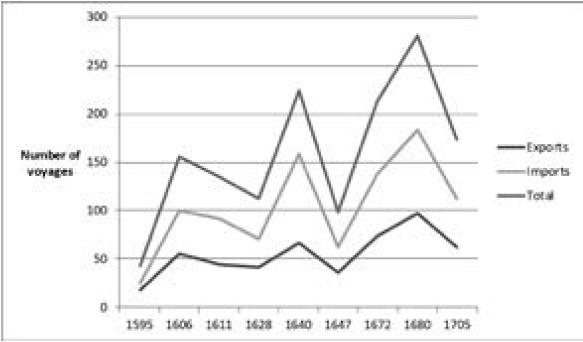

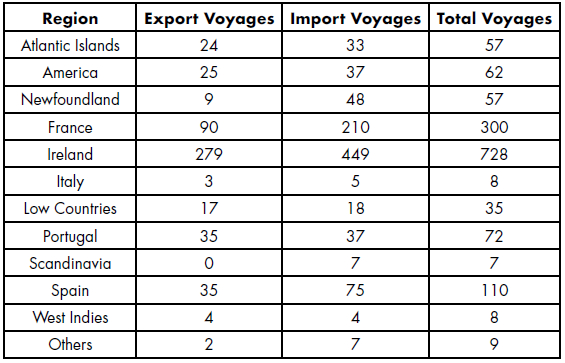

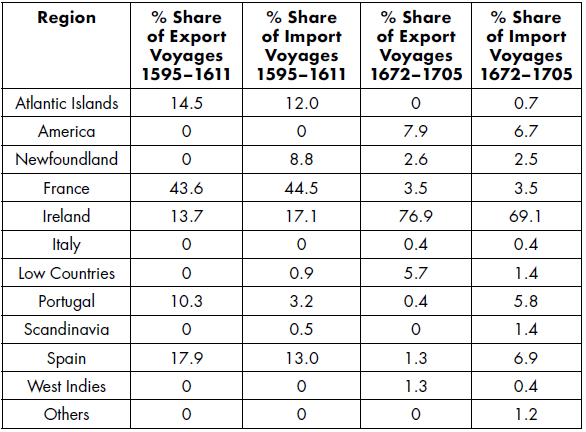

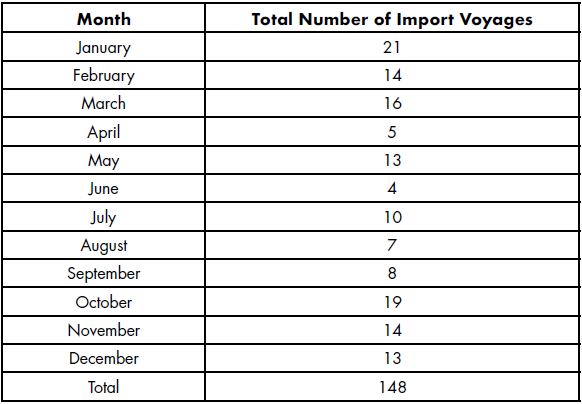

6 Figure 1 shows how the overseas trade of North Devon grew during the seventeenth century, as measured by the number of voyages recorded in the accounts. It also shows the fluctuations attributable to wars (in 1628 the Anglo-Spanish War; the English Civil War and the Irish Confederacy wars in 1647; and the War of the Spanish Succession in 1705) and how imports were consistently more numerous than exports. A total of 87 ports or geographical regions (Ireland, Norway, Portugal, and Spain, where specific ports were not given) traded with North Devon. For 27 of these only a single voyage was recorded, and for a further 11 only two voyages were recorded. Table 1 shows the breakdown of voyages in the seventeenth century using 12 broad geographical regions. The Atlantic Islands of the Azores, the Canaries, and Madeira are treated as distinct from mainland Portugal and Spain, and the American colonies of Carolina, Maryland, New England, and Virginia are distinguished from Newfoundland.Thus North Devon’s overseas trade was dominated by Ireland, France, and Spain, with Newfoundland occupying fourth place and just ahead of America, Portugal, and the Atlantic Islands as the other principal trading partners. The seventeenth century saw a considerable relative shift in the pattern of North Devon’s overseas trade, which is summarized in Table 2. The major trends are the sharp decline in both relative and absolute terms of trade with France and rather less dramatic declines in the shares of trade with Portugal and Spain. Trade with Ireland accounted for under a fifth of the total early in the century but by the end it accounted for around three-quarters. Trade with America was non-existent in the early years but had grown to account for around 7 per cent of voyages by the end of the century. The share of trade with Newfoundland fell during the century, although in absolute numbers of voyages, it was roughly the same.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 2

7 Around two-thirds of the voyages recorded in the Port Books involved just nine ports, with Newfoundland occupying fifth place, although with only a little more than a quarter of the number of voyages of the two leading ports, La Rochelle and Waterford, with 208 and 201 voyages respectively. La Rochelle traded with North Devon in every year, but the volume of its trade had fallen to next to nothing by the end of the century. By contrast, Waterford saw only a handful of voyages early in the century but these increased rapidly in number, so that by the end of the century it had displaced Dublin as North Devon’s principal Irish trading partner. Cork, Kinsale, New Ross, and Wexford were four other significant Irish trading partners, but Wexford declined as New Ross grew in the second half of the century. There is no apparent reason for this as both ports were stormed and sacked by Cromwellian forces in 1649, although it has to be conceded that the Slaney is far more difficult to navigate to Wexford than is the Barrow to New Ross. Bilbao in northern Spain completes the list of major trading partners and it, too, had voyages in most years.

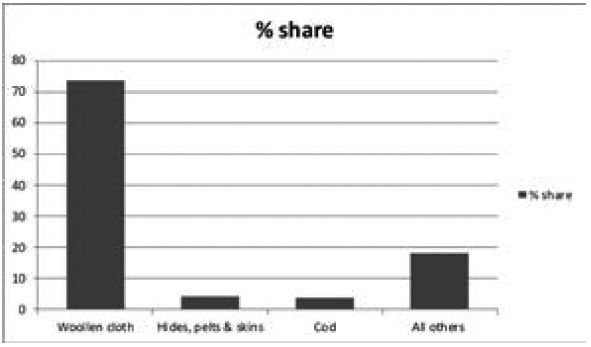

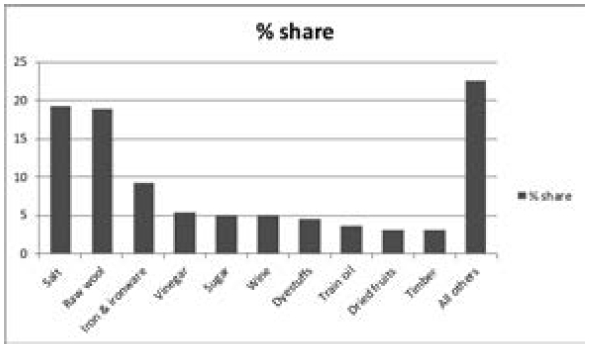

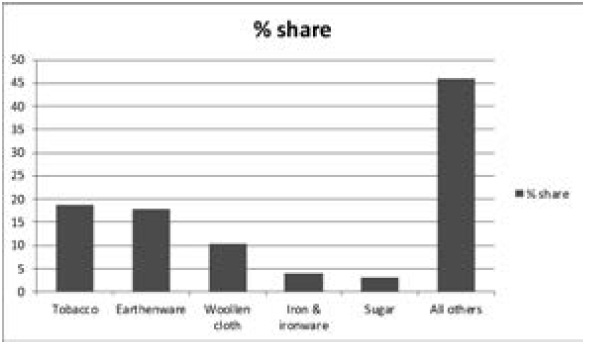

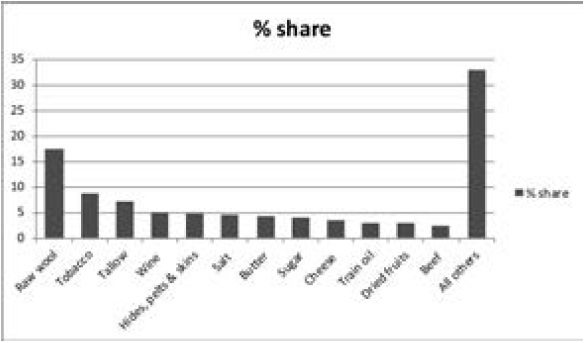

8 The overseas trade of North Devon grew both in the number of voyages and in the number of consignments during the seventeenth century. There were also some significant changes in the commodities being traded, although a basic pattern was sustained throughout. Figure 2 shows the share by consignment of the principal commodities exported in the early part of the century (1595, 1606, and 1611). Woollen cloths, particularly bays, were the dominant commodity, and the production of this cloth was reflected in two of the imports shown in Figure 3, where raw wool, principally from Spain, was the second most important commodity and dyestuffs, especially woad, were around 5 per cent of the consignments. The Newfoundland trade features, with salt from Europe as a principal import and train oil from Newfoundland as another import of some consequence. The markets for salt cod were principally in Portugal and Spain, where cargoes of dried fruit, wine, and iron could be procured. Tavenor (2010: 31) sees the two former as cargoes of convenience in Spain, but the iron was necessary to meet demand for hooks and nails in the fishery. A peculiarity of the early seventeenth century was the import of vinegar from France, in particular La Rochelle. By the late seventeenth century (1672, 1680, and 1705) the range of commodities in trade had widened and so the share of woollen cloth in the exports had fallen; indeed, cloth had been replaced by tobacco as the principal export, as shown in Figure 4. North Devon’s pottery industry grew significantly at this time and earthenware featured prominently in the export trade. Figure 5 shows train oil as a relatively minor import, but beef, butter, and cheese from Ireland to provision the fishing fleet together accounted for nearly a tenth of all import consignments and it must be presumed that a considerable proportion of the hides, pelts, and skins imported were made into leather for aprons, jerkins, and sea-boots for the migrant fishermen. The number of consignments of salt remained roughly the same as earlier, although their share of the import trade fell and Spain replaced France as the principal source. It is also evident that North Devon had become an entrepôt by the late seventeenth century and was dispatching most of the tobacco it imported to Ireland and to Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Even coal, which was being imported from South Wales, was being sent on to Irish ports. Although not numerous, later in the century some very mixed cargoes were sent to America to meet a range of requirements, including drapery, haberdashery, and earthenware, for which. as Watkins (1960) notes, North Devon was a major supplier, and far more unusual items such as cartwheels and quern-stones were exported to Maryland in 1680.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

Triangular Trades

9 Almost all histories of the Newfoundland fishery, including those by Cell (1969), Grafe (2003), Handcock (1989), Innis (1954), Lounsbury (1934), Matthews (1968), Pope (2004), Starkey (1992), and Tavenor (2010), insist that it was part of a set of triangular trades. The general pattern of overseas trade for North Devon in the seventeenth century shows how the Newfoundland trade meshed with many of the other trades. Provisions were being shipped from Ireland, and Ireland too supplied many of the hides, pelts, and skins from which leather was made for the fishing fleet. Another commodity vital to the fishery was the supply of barrel staves, which also came from Ireland in ever greater quantities in the latter part of the century. The salt, so essential to the curing process, was imported from France, Portugal, and Spain, and iron for use in boat-building, construction of the fishing stages and flakes in Newfoundland, and for fish hooks came from northern Spain.

10 There seems to be a general consensus that ships from South West England followed the lead of North Devon ships and called at ports in southeast Ireland to collect supplies before sailing to Newfoundland for the season. Pope (2004: 23) notes that this was commonplace by the late seventeenth century and commenced the process of Irish migration to Newfoundland, points also made by Mannion (2000: 14; 2001: 266). Tavernor (2010: 30) suggests that some English ships sailed to Portugal and Spain for salt prior to crossing the Atlantic. The Port Books would not record ships sailing in ballast or with men and gear for the summer fishery, but it might be presumed that a ship sailing to Ireland would have a little room for a commercial cargo, which would then be replaced by the provisions to be loaded in an Irish port. An examination of the Port Books for 1672, 1680, and 1705 does not yield a single instance of a ship leaving North Devon for Ireland and then failing to return within a few weeks. All this proves is that merchants did not attempt to combine a Newfoundland expedition with a little trade in Ireland on the outward journey, but it does serve to underline how many ships must have been provisioned with supplies previously imported from Ireland and perhaps packed into freshly made barrels in North Devon.

11 If ships did leave North Devon for France and Iberia for salt to carry to Newfoundland, which seemed to have been the case with sack ships sailing later in the summer, then again it would seem reasonable to assume that at least some might have carried woollen cloth from North Devon on the outward voyage to collect salt. Again, the Port Books do not show any instances of ships making one-way voyages to Cadiz, La Rochelle, Lisbon, or any of the other Iberian ports. Ships sailing from Newfoundland to Iberia with salt cod might be expected to return to North Devon with wine and dried fruits and to do so from October to December, having left Newfoundland in August or early September. Table 3 shows the monthly arrivals of imports from Iberia for the seventeenth century. These do fall more within the half-year October to March, but hardly any are one-way voyages for the ship and in any case are as plausibly explained as shipment of the vintage, once ready, as showing in the return of sack ships to North Devon. It has to be concluded from the evidence of the Port Books that not many ships seem to have made triangular voyages, but Barnstaple and Bideford certainly did form nodes in trading that linked France, Ireland, Iberia, and Newfoundland.

Display large image of Table 3

Display large image of Table 3

12 The selection of Port Books has entries for 56 import voyages and nine export voyages involving Newfoundland in the seventeenth century. It is not easy to ascertain how many individual ships were involved, but only one ship, the John in 1705, is recorded as making both outward and return voyages the same year. Following the other voyages made by ships known to have sailed from Newfoundland does shed some light on the way the Newfoundland trade fitted into North Devon’s wider trading patterns. In the 1595 Port Book, two ships made appearances other than bringing train oil from Newfoundland. The Handmaid had arrived in October with train oil for a well-known Bideford merchant, John Short, and in December, under a different master, sailed to La Rochelle with coal for Baptist Tucker, a Barnstaple merchant. The ship returned with salt, also for Baptist Tucker, in March 1596, potentially in time to make a further voyage to Newfoundland for the season. In September the Katherine arrived with train oil for her master John Dennis and then arrived once more in January with woad from Terceira under another master and for Robert Martin, a Barnstaple merchant. In 1606, the Port Books have two interesting sets of voyages. In September, the Phoenix, master Thomas Topp, arrived with salt cod and train oil for Richard Beaple of Barn-staple and the following month, still under the command of Thomas Topp, she sailed for Lisbon with a cargo of woollen cloth and salt cod for the Barnstaple merchants Pentecost Dodderidge and John Salisbury. For the Joseph,there are four voyages under two masters. In January, she sailed for Nantes with a cargo of herrings and salt cod for William Darracott of Bideford and returned in March with a cargo of prunes, salt, vinegar, and wool from nearby Le Croisic, again for William Darracott. Her departure for Newfoundland is unrecorded but she returned in September under master Thomas Beaple with salt cod and train oil for Nicholas Delbridge of Barnstaple. The last entry is for her departure in December, under Thomas Beaple, with a cargo of herrings and salt cod for the Canaries, for merchant Nicholas Delbridge. In 1611, two ships sailed on to Lisbon with woollen cloth and salt cod after arrival from Newfoundland and another went to La Rochelle. The 1640 Port Book records three voyages for the Speedwell. Her first is an arrival from Bilbao with wool and iron in February. Then in May she sailed for Newfoundland with a cargo of lead and returned in July with a cargo of sugar from Sao Miguel in the Azores, presumably having brought salt cod there from Newfoundland. Also of interest from 1640 is the Truelove, which arrived in October from Newfoundland with train oil for the Bideford merchant, George Short, but the previous March the Truelove had arrived from Faial with a cargo of ginger, sugar, and woad for George Short. In September 1640, the Vineyard, master David Baker, arrived with train oil from Newfoundland for James Gammon and himself, and in November, again commanded by David Baker, the Vineyard sailed for Dublin with train oil for James Gammon and hops and raisins for Henry Kingston. Another ship, the Seaflower, sailed onward under the same master, Richard Sherman, after arriving with train oil, but this time to La Rochelle, with a cargo of coal for her master. To underline how ships seemed to move between trades and cargoes, in September 1640 the Mermaid, under Christopher Smale, arrived with train oil for James Gammon and within less than a month was outbound to Faial in the Azores, again under Christopher Smale, but this time with a mixed cargo of canvas, soap, and woollen cloths for George Short of Bideford and Richard Beaple of Barnstaple.

13 In 1647, the Truelove, probably the same ship as in 1640, commanded by Vivian Limbury, arrived from Newfoundland with train oil for George Short and with the master and merchant combined when she sailed in December for Faial with salt cod and woollen cloth. Also of interest from the 1647 Port Book are the four voyages of the William under Richard Pearce, arriving in December 1646 from La Rochelle with vinegar and salt for merchant William Palmer, returning thence in February with coal and woollen cloth, also for William Palmer, and finally arriving once more in Bideford in May with barley for John Palmer. In October, the ship arrived from Newfoundland with salt cod and train oil for William Palmer and Robert Fleming and then, this time under the command of Henry Ramsey, the ship sailed for La Rochelle with coal and woollen cloth for William Palmer.

14 In 1672 the pattern of ships arriving in North Devon from other ports prior to an arrival later in the year from Newfoundland is seen in the voyage of the Fellowship, master James Cock. She arrived in April from Waterford with a cargo of butter, cheese, tallow, and wool for the Bideford merchant, John Davey. In October she returned from Newfoundland with salt cod and train oil for George Middleton and her master. Although the cargo carried to Newfoundland by the Diamond is not recorded, her arrival with lemons, nuts, oranges, wine, and salt from Porto for Abraham Hayman is, and both voyages were under the command of Robert Fishley.

15 In March 1680, the Lamb, master John Whitfield, arrived from Waterford with butter, cheese, Irish frieze cloth, and Spanish salt, sugar and raw wool for John Davey, and about a fortnight later she sailed for Newfoundland with beef and salt, also for John Davey. In February the Unicorn, master William Wilkey, had sailed to Newfoundland with tobacco for merchant Philip Gribble but her return to North Devon went unrecorded. The Delight had arrived in February with iron and sugar from Bilbao for five Bideford merchants, including Andrew Hopkins, who was listed as the merchant when she sailed for Newfoundland in April with beef, bread, and peas, again under the command of Samuel Cade. That same year, five ships were recorded as bringing train oil from Newfoundland and four of them, earlier in the year, had arrived from Portugal and Spain with salt but also carrying olive oil, raisins, sugar, and wine, serving to underline how interlinked all of North Devon’s various trades were. None of the outward journeys to Newfoundland were recorded.

16 The voyages of the ships discussed above, albeit a small proportion of the total, show how vessels tended either to arrive in North Devon with key provisions for the fishery, like salt from Iberia and foods from Ireland or to sail on to Iberia with various cargoes after the arrival in the autumn from Newfoundland. The imports they brought from Iberia were often a mixture of luxury goods, like wine and sugar, and essentials such as salt, while the exports carried, usually woollen cloth, were typical of North Devon’s wider export trade with Iberia.

The Heads of Inquiry Returns and the Port Books Compared

17 From 1675 the senior naval commander at Newfoundland was expected to make a report to the English government. These vary in the amount of detail recorded and unfortunately none of the fuller returns coincide with one of the Port Books transcribed. The Port Books of 1672 and 1680 can be examined against the Heads of Inquiry returns for 1675, 1676, 1677, and 1681, which for Ferryland, the favoured destination of North Devon ships, have been transcribed by Peter Pope.3

18 Of eight ships recorded in the 1672 Port Book as sailing in the Newfoundland trade, just four appear in the Heads of Inquiry returns for 1675–77.These contain the names of 16 ships that do not appear in the Port Books, with the Delight and the Mermaid, both of Bideford, being recorded at Newfoundland in all three years, 1675–77. The Delight does appear in the Port Book for 1680, both in Newfoundland and also engaged in the Spanish trade. The 1680 Port Book records eight ships in the Newfoundland trade, with none of the 1672 Newfoundland vessels, although the Delight now appears. The Heads of Inquiry return for 1681 has only six North Devon ships, none of which was recorded in the Port Book the previous year. In 1681 the Expedition of Barnstaple was reported from Newfoundland in the Heads of Inquiry and the previous year the Port Book noted her voyage to Maryland. Both the Rainbow and the Ruby were in Newfoundland in 1681, but in the previous year the Port Book recorded their voyages to Spain.

19 The Heads of Inquiry returns for 1698 to 1701 and 1708 contain a little detail on the passages ships in Newfoundland had made.4 In 1698 both the origin of the inbound journey to Newfoundland and the destination of the outbound voyage were recorded, but for the 1699, 1700, 1701, and 1708 returns entries only relate to the destination of the outbound voyage from Newfoundland, and not all destinations were recorded. In 1698 most of the ships had arrived in Newfoundland carrying “necessaries” and “provisions” and some both, and presumably the distinction implied that the “necessaries” were for the ship’s company for the season and the “provisions” were for planters and any men being left to overwinter. Two ships had come from Bide-ford and another via Topsham on the Exe estuary and more than 430 kilometres around Land’s End from Bideford. There is no obvious reason for this, especially as the voyage along the south coast of Cornwall and Devon would have made the ship yet more vulnerable to attack from French privateers. Four ships had come via Ireland, two from Dublin and one each from Waterford and Youghal, examples of one of the classic triangular trades. A single ship had come from Iberia carrying salt and wine. In the returns for the five years, the outbound voyages from Newfoundland are given for 24 of the 36 ships. Seven were returning directly to North Devon and two more had “England” as their destination. All these ships were carrying train oil and salt cod. Five ships were bound for Portugal and four for Spain, and a further five were given “the Straits” as their destination, implying ports within the western Mediterranean. A single ship went to Barbados. This and those heading to Iberia and the Mediterranean all carried salt cod. From the Heads of Inquiry returns it can be seen that, while triangular voyages taking cod to Iberian and Mediterranean markets were in a clear majority, more than a third of the voyages brought the ships back directly to England. Thus the data from the Port Books, which seem to show few if any arrivals from Iberia after a fishing season in Newfoundland, are supported to some degree by evidence from the Heads of Inquiry returns. There remains the still unresolved question as to how North Devon ships sailing to Iberia eventually found their way home, and in time to sail to Newfoundland for the next season.

North Devon’s Merchants and the Newfoundland Trade

20 Various opinions have been expressed about capital requirements and ease of entry to the Newfoundland trade in the seventeenth century. Matthews (1968: 62) suggests that a primary reason why Devon in general and not South Wales or Ireland came to dominate the Newfoundland trade in the seventeenth century was the accumulated capital in ships and knowledge in seafaring that these others lacked. Cell (1969: 6) noted that the Newfoundland trade, compared to others, required limited capital investment and could rely on the supply of materials readily available in the home port. Taylor (2009: 32) suggests that the Newfoundland trade attracted the merchants whose enterprises were larger and better capitalized. While the seventeenth-century Port Books cannot directly answer questions about the capitalization of merchants in the Newfoundland trade, they can give some indication of the scale of their operations as seen in the number of consignments they handled.

21 Matthews (1968: 16) notes how the Newfoundland trade was the base upon which all other trades in West Country ports rested but then made the point (Matthews, 2001: 155–57) that the terms “the Newfoundland merchants” and “the merchants of the port” were not necessarily synonymous and when this latter term was used in petitions to government, it perhaps reflected the greater power of the former. The Port Books allow the transactions of all the merchants to be examined and to see how important the Newfoundland trade was in the overall pattern of enterprises of individual merchants.

22 In 1595, nine merchants were involved with Newfoundland, with two of them also being masters of the ships in which train was carried. John Delbridge of Barnstaple was among the Newfoundland merchants and he also handled the most consignments of any merchant that year. His trading links were with La Rochelle, Bayonne, and St Jean-de-Luz and involved export of woollen cloth and import of salt and wine. Three other Newfoundland merchants also traded with La Rochelle and Bayonne, but of the other leading merchants in terms of numbers of transactions, none was active in the Newfoundland trade. In 1606, six merchants were active in the Newfoundland trade, with one also being a ship’s master, but he had no other trading transactions, and the leading merchant in North Devon in terms of transactions, William Palmer, did not participate in the Newfoundland trade. However, Richard Beaple of Barnstaple, the second most active of the merchants, was involved with Newfoundland and also traded with western France, Iberia, and the Canaries, exporting woollen cloth and importing salt, wine, and wool. Thomas Leigh was the sixth most active merchant and besides his Newfoundland trade, he exported woollen cloth to La Rochelle and imported salt from there and wine from Iberia. In 1611 eight merchants imported fish and train oil from Newfoundland, with one being a ship’s master with no other trading activity and two others also had no other trading activity. None of the six leading merchants traded with Newfoundland and, as in 1606, the other trading links of the Newfoundland merchants were with La Rochelle, Iberia, and the Atlantic Islands. In 1627 only a single voyage from Newfoundland was recorded and the merchant involved, Melchard Bennett, was not among the leading merchants. His other activity involved importing beef, linen cloth, tallow, and wool from Dublin and beaver skins from Virginia.

23 By 1640, the Newfoundland trade was more extensive and involved two export cargoes of lead, as well as the usual import of train oil and salt cod. Thirteen merchants participated, with two of them being ship’s masters and one of these also acted as a merchant for a single consignment of salt from Le Croisic, also in his own ship. North Devon’s leading merchant in terms of consignments was James Gammon, with extensive trading links to France, Ireland, and New England as well as Newfoundland, with provisions coming from Ireland and salt from La Rochelle. Gilbert Paige of Barnstaple, with only a third as many transactions as James Gammon, had a similar pattern of operations and also traded with Spain. The other Newfoundland merchants had rather more restricted contacts but again traded with France, Ireland, and Spain. The second merchant in the number of transactions was William Palmer, with nearly half the total of James Gammon, but his links excluded Newfoundland. The English Civil War of 1642–51 had been a difficult time for Barnstaple and Bideford, with both ports enthusiastically declaring for Parliament before falling to the Royalists and remaining in Royalist hands, notwithstanding a brief rebellion in Barnstaple, almost to the end of the war. Lea-O’Mahoney (2011: 164) notes the importance to the Royalist cause of levies on the Newfoundland trade, and while North Devon received eight ships from Newfoundland in 1647, not much down from pre-Civil War levels, other trade in the ports had fallen back. A total of 13 merchants was involved in the Newfoundland trade, with one being master of the ship conveying the train oil. Five of the merchants had no other transactions. William Palmer was both the leading merchant overall but also active in the Newfoundland trade. His other links were with Ireland, La Rochelle, and Amsterdam. Most of his business was the export of woollen cloth. Not far behind in number of transactions was George Short of Bideford, another combining the Newfoundland trade with links to Ireland, re-exporting Spanish wine and spices and exporting woollen cloth to France and Spain. Two other leading merchants had similar enterprises, although together they only just equalled those of George Short.

24 By 1672 North Devon had become a significant importer of tobacco from Virginia and tobacco also became a significant export, much being sent to Ireland and the Low Countries. In that year 16 merchants handled goods from Newfoundland and half of them had no other transactions. Four of the leading merchants were participants in the Newfoundland trade, but this would appear to have played a minor role in their overall enterprise, especially as this included the tobacco trade. The principal merchant was John Davey of Bideford but most of his trade was either in the re-export of tobacco to Ireland or the import of butter, cheese, tallow, and horses, chiefly from Waterford. Abraham Hayman had about two-thirds the number of transactions as John Davey, and like him was trading with Ireland from Belfast round to Cork, but he had links with Portugal and Spain, importing iron, wine, and fruit. The other Newfoundland merchants had links with Iberia and Ireland but their trade with Ireland was export, chiefly of earthenware, sugar, and tobacco. One with just the import consignment of train oil to his name is Philip Kirke, who must surely be the son of Sir David Kirke of Ferryland.

25 In 1680, a total of 30 merchants had some participation in the Newfoundland trade with two being masters of a ship in the trade, and neither of these had any other transactions. Of the others, 10 had no other transactions. North Devon’s leading merchant, John Davey, sent beef and salt to Newfoundland and imported a single consignment of train oil. He had extensive links with Maryland, sending general cargoes and receiving tobacco, which then formed much of his onward trade to the Low Countries and Ireland. His import trade from Ireland comprised wool and potential provisions for the fishery such as butter and cheese. The second merchant in number of consignments was Hartwell Buck, but it is clear that his principal interest was in the import of tobacco from Maryland and Virginia and its onward trade to the Low Countries and Ireland. He also was a significant supplier of basic goods to the American colonies. Abraham Hayman, Andrew Hopkins, and William Titherley had similar trading patterns to Hart-well Buck, but also were importing olive oil, dried fruits, salt, and wine from Cadiz. Most of the other Newfoundland merchants either traded with Iberia or with Ireland but not with both. Of North Devon’s 14 leading merchants, eight had no interest in the Newfoundland trade.

26 The 1705 Port Book records just three voyages involving Newfoundland, with two of imports and one of export. John Buck handled the export and import voyage of the John and was the merchant with the second greatest number of transactions overall. His principal activity, like that of Hartwell Buck in 1680, was in the tobacco trade with imports from Virginia and shipments onward to the Low Countries and Ireland. The other Newfoundland import was handled by William Langdon, who ranked sixth in terms of overall transactions and, like John Buck, was involved with the tobacco and supply trade with the North American colonies and with more traditional links to Ireland and Iberia.

27 The Port Books examined show that many of the busier merchants were indeed involved with the Newfoundland trade, but that their other activities, particularly in tobacco in the second half of the seventeenth century, tended to be greater. Most also continued North Devon’s traditional trade with Portugal and Spain, even if this tended to be confined to imports of wine and salt. Ireland was also a focus of interest for the Newfoundland merchants, but it seems that not all of them were importing provisions that might have been used for the fishing fleet. The Port Books cannot give any picture as to the involvement of North Devon’s Newfoundland merchants in provisioning their ships in Ireland en route across the Atlantic, but the Port Books do seem to suggest that there must have been some purchase of Irish provisions in North Devon prior to departure for Newfoundland.

28 Some measure of the influence of merchants, in particular Newfoundland merchants, can be gauged by their participation in the governance of their towns. Unfortunately there are no surviving lists of members of the Town Corporations of Barnstaple and Bideford, but a full listing of the mayors of Barnstaple exists. Clearly, one problem in comparing the names of Newfoundland merchants from the Port Books with those of the mayors of Barnstaple is that fathers and sons and uncles and nephews sometimes shared the same name. Between 1590 and 1710, there are 87 different names of mayors of Barnstaple and it is likely that this actually involves 89 people. The influence of family connections can be seen in that only 68 different surnames occur. Forty-four merchants whose transactions appear in the overseas trade in the Port Books were mayors and nine of these also participated in the Newfoundland trade at some time. Thus it seems reasonable to presume that merchants as a group had considerable influence in the governance of Barnstaple and that the Newfoundland trade would usually have had a good hearing in the deliberations of the Corporation. Starkey (1992: 168) goes further, claiming that the Western Adventurers from ports in South West England dominated local government and could readily use this to express their disquiet about Newfoundland policy to the government as and when required. Matthews (2001) expresses more skepticism and suggests that there were probable tensions between the Newfoundland merchants and other merchants in any port, and he therefore questions the ability of the former to mobilize the Corporation to promote the Newfoundland interest in the counsels of the English government. The case of Barn-staple perhaps offers more support to Matthews than to Starkey.

Conclusions

29 The seventeenth century saw an expansion of North Devon’s overseas trade, and central to this was the Newfoundland fishery and trade in salt cod and train oil. The Newfoundland trade was not the largest of the trades carried out, but it complemented and built on older trade with France, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain. Towards the end of the century it is clear that the tobacco trade from North America, with the re-export of tobacco within England and to Ireland and the Low Countries, was attracting the major merchants. Trade with France contracted but that with Ireland expanded greatly. Ireland replaced Spain as the supplier of raw wool for the local cloth industry and became a principal supplier of provisions for the Newfoundland fishery. However, the Port Books, unlike some of the Heads of Inquiry returns, are unable to show evidence of North Devon ships sailing for Newfoundland via ports in southeast Ireland, although it is clear that supplies of butter, cheese, and meat were the other staples of the import trade from Ireland. In the early part of the century salt had been imported from La Rochelle and around the mouth of the river Loire and this, too, was to supply the Newfoundland fishery. As the political situation deteriorated, Portugal and Spain took over as sources of salt, but there is once again no evidence from the Port Books that North Devon ships en route to Newfoundland sailed to France and Iberia to collect salt. The classic accounts of the Newfoundland fishery stress the significance of Iberia as a market for Newfoundland salt cod and how this then funded the purchase of wine and fruits for import. Most of the Port Book entries for Iberian trade show ships making both outward and return voyages and there is only a slight seasonality in the arrival of ships from these ports, which is as plausibly explained by shipping the wine vintage as by ships calling in Iberia after the summer fishing season. Thus the Port Books suggest more complex patterns of trade than the simple triangular trade of the classic accounts. It seems that commodities arrived in North Devon from Ireland and Iberia to supply the fishing fleet, but ships in that fleet cannot be seen to be making triangular voyages. Data from the Heads of Inquiry returns do offer more support to the notion of triangular trades, but even here a large minority of ships made simple two-way voyages across the Atlantic.

30 The Newfoundland trade involved many North Devon merchants, but it cannot be said that the major merchants dominated it. For about half the merchants named in the Port Books in conjunction with the Newfoundland trade, it was the only thing that they did and most had but a single consignment of train oil in any year.The Newfoundland trade shared a characteristic with the other trades in that a number of ships’ masters had an interest in the cargo they carried. Most of the larger merchants involved with Newfoundland had a range of other interests, usually exporting woollen cloth and importing salt and wine from France, Portugal, and Spain and provisions from Ireland. By the end of the century the tobacco trade had become significant for these larger merchants. What is also noticeable is that some merchants appeared to dip in and out of the Newfoundland trade over the course of their careers, although there is little to suggest that they had to be successful in other trades, especially that with Ireland, in order presumably to accumulate the capital necessary for the Newfoundland trade. Those trading with Newfoundland hardly formed a distinct group among the merchants, and throughout the seventeenth century, Newfoundland merchants were always in a minority. However, merchants in general and Newfoundland merchants in particular do seem to have had a significant presence in the Corporation in Barnstaple. Whether they could always easily co-opt their fellow merchants to send petitions and appeals to national government is less clear. The importance of the seventeenth century and the significance of the Newfoundland trade are clear in the maritime history of North Devon, even if Kingsley’s shadow tends to obscure it in local popular imagination.

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful to Professor Barry Gaulton for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript and to the anonymous referees for their feedback.