Research Note

The Newfoundland Potato Famine, 1846–48

An Account from the Colony’s Newspapers

Introduction

1 While the Great Potato Famine in Ireland continues to be studied in extensive detail,1 little seems to have been written about the famine, caused by the same blight, that simultaneously struck Newfoundland. Prowse’s History of Newfoundland (first published in 1895 when many survivors would have still been alive) describes the earlier famine of 1814–172 but omits any mention of the famine that occurred in 1846–48. Other Newfoundland histories include a discussion of the topic, but only in a few brief sentences, often secondary to discussion of another matter.3 None explore the subject in depth.

2 At first glance, the absence of studies of the famine in Newfoundland is puzzling. The surviving newspapers from this era contain numerous descriptions of conditions in Newfoundland that, at least on their face, appear as heart-rending as scenes from Ireland.4 In 1848, for example, the editor of the Harbour Grace Weekly Herald described the bleak circumstances in Conception Bay. In language that could have applied equally to the shores of Ireland, he wrote that “thousands of our population in this Bay are in a starving condition — it is painful — distressing — harrowing to meet them in the street — to have them at our doors — to see them fainting at our hearths.”5

3 With the potato providing nearly the sole source of sustenance for most of Ireland, the blight brought to its population a devastation that was unmatched in scale and duration. Yet the suffering caused by the same blight in Newfoundland appears to have been substantial, and a brief glimpse into the social and economic conditions in Newfoundland during this era reveals both similarities and differences with Ire-land that make the Newfoundland famine an intriguing topic of study. As discussed herein, the similarities include the nature of the blight and its nearly simultaneous appearance on both islands; the intense debate between the proponents of laissez-faire economics and the advocates of immediate government relief; the requirement of work on public projects such as road construction in order to receive public assistance; and the exportation of large quantities of food at the height of both famines (grain from Ireland, cod from Newfoundland). Among the differences are the multiple causes of the Newfoundland famine; the larger scale and longer-lasting consequences in Ireland; the establishment of workhouses and soup kitchens in Ireland but not in Newfoundland; and the mass evictions and mass emigration that occurred only in Ireland.

Prologue to the Famine

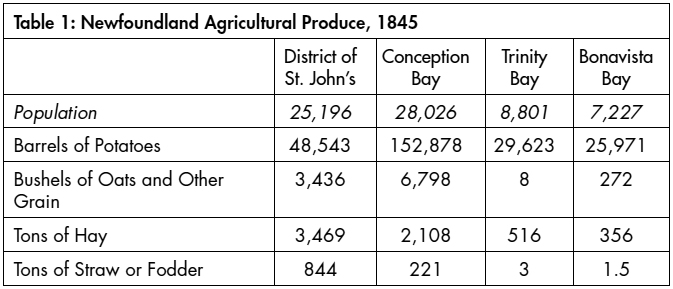

4 In 1845, a year before the famine began, the colonial government conducted a census in Newfoundland that included data for the island’s agricultural produce:6

5 While these statistics provide only a brief overview of the produce grown in the various districts, the preponderance of potatoes over other staples suggests a lack of agricultural diversity and hints at the precarious nature of the food supply. The statistics also indicate the susceptibility of the population to dire shortages in the event that a failure of the potato crop would coincide with a failure of the fisheries. And that is precisely what occurred, beginning in 1846.

6 Although the origins of the potato blight are obscure, the first known outbreak occurred three years earlier, in the eastern United States in 1843.7 Borne by the winds and by shipments of infected potatoes themselves, by 1845 the blight had crossed the Atlantic and spread throughout Northern and Central Europe. Its first appearance in Ireland was detected in early September 1845.8 In the same month in North America, the disease reached the potato fields of Prince Edward Island9 and just three months later, in December 1845, the blight arrived in Newfoundland. The first potatoes to be visibly affected were not the crops in the fields, but the “immense quantities” in storage in Lamaline, some having been shipped from Prince Edward Island and nearly all found to be “attacked by the disease and rendered useless.”10

7 By the following year, 1846, the blight had reached every field in Ireland and the Great Famine had begun.11 In Newfoundland, the disease had spread along the southern coast but appeared to have advanced no further.12

8 Even before the arrival of the blight, 1846 had been a difficult year for the colony. Both the spring seal hunt and the summer cod fishery — the heart of Newfoundland’s economy — had produced disappointing returns.13 In addition, two more calamities struck Newfoundland in 1846, contributing to a convergence of events that dramatically altered the island’s food supply. The first was the 9 June 1846 fire in St. John’s. By the time the flames were extinguished, more than half of the city was in ashes, including nearly all of the mercantile establishments that lined the waterfront and provided supplies for the fisheries.14 Then on 19 September, just three months after the fire, an unusually ferocious gale struck the island. The storm destroyed fishing premises throughout the outports, shattering fishing boats, flakes, stages, and supplies, and leaving desolation in its wake.15

9 Ordinarily after a gale, even after a particularly destructive one, the planters in the outports, along with all those dependent on the fishery, could find the means to rebuild. Unfortunately, rebuilding after the gale of 1846 was far more difficult. Since the mercantile establishments in St. John’s had been destroyed in the June fire and were in ruins themselves, they were unable to advance the necessary supplies to rebuild the destroyed premises in the outports.16

10 Even though St. John’s had been severely damaged by the fire, funds for rebuilding, both public and private, had reached the city by winter, and the nearby potato fields remained free of disease. In the outports, however, the suffering caused by the gale, the failed fisheries, and the harsh winter was acute. Reports were received from Trinity Bay that a severe frost had penetrated normally secure root cellars and destroyed stores of potatoes. Cellars were robbed by starving neighbors in Conception Bay. By mid-winter, Port de Grave, Brigus, and Bay Roberts were reported to have no provisions.17

11 In December, the editor of one of the weekly newspapers in St. John’s, the Newfoundlander, made a plea for relief: “That the destitution of the Outports must be met, no one denies. Wherever the means comes from, the people cannot be permitted to starve.”18 And so the stage was set for the momentous year, 1847.

The Famine

12 On 2 February 1847, when harbours were frozen and communication with St. John’s was limited, the businessman Thomas Hutchings left St. John’s to travel overland around Conception Bay. Hutchings took detailed notes about the communities he visited, and upon his arrival at Bay de Verde he sent an extensive account to the St. John’s weekly, the Royal Gazette.

13 In his account — still prior to the spread of the blight beyond the south coast — Hutchings found that the failed fisheries of the past year had resulted in “extreme destitution” among some of the families in Topsail, Holyrood, and Brigus.19 In proceeding around the Bay, Hutchings also reported that from Carbonear to Black Head “the late intense frost has destroyed a large portion of the potatoes of many families . . . seed potatoes will be exceedingly scarce in the ensuing spring, more especially as many poor people will be necessitated to eat those they have reserved for seed, or starve.” Beyond Carbonear and Black Head, Hutchings noted that “Many cellars, &c, have been broken open on the North Shore and the potatoes taken by the starving people.”20

14 In addition to Hutchings’s account of the conditions in Conception Bay, the Royal Gazette published accounts from more distant locations. On 23 February the newspaper reported that “a portion of the inhabitants of Bonavista Bay were in a starving condition.” According to this account, “some individuals had come over from King’s Cove, to Trinity, and reported that some of the inhabitants were without food.”21

15 With acute shortages of food and supplies, the outfitting and provisioning of the spring sealing fleet, while simultaneously arranging for those left behind, was a difficult task. On 3 March the Harbour Grace Weekly Herald acknowledged the importance of the upcoming seal hunt, but also warned of the growing despair for those remaining at home. “The sealing craft, we admit, will relieve the district of some five or six thousand mouths, but unfortunately these are they upon whose daily exertions the bulk of the population are dependent for support. Who, for the most part, will be left behind? Women, the aged, the decrepit, and the helpless!”22

16 The editor asked, “How are those to be fed? . . . The accounts we continue to receive from various parts of the Bay are truly distressing. There may, perhaps, be a small stock of potatoes in the settlements south of Brigus, but with this exception the destitution is complete — it is awful.”23

17 While the struggling population awaited the return of the sealing fleet from the ice fields, private philanthropies, including the Benevolent Irish Society, continued their efforts to raise funds for relief not only for the impending famine in Newfoundland but also for the Great Famine in Ireland. In the process, hostility grew in some quarters towards the concept of raising Newfoundland funds for anyone other than Newfoundlanders.

18 The conflict appears to have been exacerbated by the writings of Henry Winton, the editor of the biweekly Public Ledger in St. John’s. Winton assailed “the infatuated people of this district” for sending funds to Ireland “whilst they are neglecting the first duty imposed upon them by God and man of relieving the necessities of the people within their own immediate neighborhood.”24 To Winton, the benefit to the poor in Ireland “can be as absolutely nothing compared with the amount of good which the very same money, laid out in the purchase of provisions here for the famished poor in the outports, would have produced.”25

19 Despite his hostility to aid for Ireland, Winton’s call for relief for the outports was valid. A 26 March letter from Bonavista, for example, described the bleak conditions in that community: “[O]wing to the very bad crop of potatoes, the scarcity of fish, &c., the last summer, and no seals to be had this spring, a great number of the inhabitants of this harbour and the neighboring coves, as well as in the Bay, are in a state of utter destitution.”26

20 The reference to “no seals to be had this spring” is indicative of the unpredictable nature of the seal hunt during this era, and provided a foreshadowing of what was to come. On 5 May the Harbour Grace Weekly Herald announced the dismal results from much of Conception Bay: the bulk of the Harbour Grace sealing fleet, along with those from at least some other harbours, returned empty. As the Weekly Herald reported, “Another fruitless sealing voyage has sent hundreds to their homes without a morsel of food or a penny in their pockets.”27

21 The suffering of the sealers in Cupids is described in painful detail by Charles Cozens, from Brigus, in a 12 May letter to the editor of the Weekly Herald. The letter provides a compelling description of the hardship in Cupids (spelled “Cubits” in the Weekly Herald) and several nearby communities:

Brigus

12th May, 1847

Sir —

A considerable number of the people in this neighborhood are still in great distress, especially Cubits, Portde-Grave and Salmon Cove; nearly all the Cubits vessels have returned without seals, and members of the families of shoremen returned having nothing in the shape of food, and have consumed all their seed potatoes . . . I am at a loss to know what many of them will do or what will be the result . . . they have failed in the Seal Fishery three years running, and most of their potato crops turned out bad.

. . .

I know many that their families had for a long time only one scanty meal a day, others have laid a-bed whole days for want of food, and had but one meal the next.28

22 While Newfoundlanders struggled with starvation, as vividly described by Cozens, the tragedy was compounded by the arrival of ships from Ireland, overloaded with emaciated passengers who had booked passage in hopes of escaping starvation in the homes they left behind. Hunger was not their only problem: contagious fevers frequently broke out during the Atlantic crossings. For this reason, on 13 May the editor of the Newfoundlander urged that quarantine regulations be strictly enforced for the vessels arriving in St. John’s.

23 The editor then described the difficulty that the port authorities encountered in trying to maintain the isolation of passengers on these ships. As he explained, “To prevent communication with passenger vessels from Ireland has always been a matter of difficulty, as it generally happens that the passengers have either relatives or friends here who, with a very natural anxiety, press on board to meet them.” The anguished residents, “if obstruction be offered to their boarding, will endeavor to effect it covertly at night, or will avail themselves at any moment of the chance of a want of vigilance on the part of the preventative authorities.”29

24 Just eight days later, on 21 May, the Public Ledger reported an incident that illustrated the extent of the problem. It concerned “the barque Bolivar, White master . . . out 37 days from Waterford. She had on board 174 passengers, three of whom died at sea.”30 The newspaper described the breakdown of quarantine upon its arrival in St. John’s: “In visiting this vessel the medical officer, Dr. Kielley, was prevented from going on board in consequence of the great number of shore boats that surrounded her, the people from which were crowding the decks, despite the efforts of the captain who endeavored to prevent it.”31

25 In the meantime, in response to the multiple and expanding crises, the colonial Governor, John Gaspard LeMarchant, issued a proclamation announcing a “day of Public Fasting and Humiliation.” The proclamation attributed the recent disasters, not to natural causes, but to the “heavy judgments with which Almighty God has been pleased to visit the iniquities of our Island.” The Governor declared the day of fasting in hopes that it may lead the Almighty to “withdraw his afflicting hand.” As the Proclamation explained, the purpose of the fast was “so that the people of our said Island may humble themselves before Almighty God, in order to obtain the pardon of their sins.”32 If anyone questioned the wisdom — or the irony — of imposing a fast on an already famished population, the local newspapers didn’t reflect it.

26 During this period, the Governor continued to submit detailed reports to the Colonial Office in London. In contrast to the piety expressed in his public pronouncements in St. John’s, the Governor’s communications with officials in London appear to have been strictly secular. His letters to the Colonial Office contain a stark critique of the social and political institutions in Newfoundland that, to him, were incapable of dealing effectively with the ongoing difficulties.

27 In correspondence dated 10 June 1847, the day after the Public Fast, the Governor conceded, “I feel very uneasy about the future.” He explained that “The Outports’ 80,000 Souls only raise a few, and a very few potatoes for the Winter supplies: all the rest they have to support them and their families are the Fisheries . . . and all are, even in the best of times and seasons on the verge of vagrancy — and a bad season leaves them destitute.” The Governor warned that without an abundant potato crop “the almost entire support of the Outports will devolve on the government.”33

28 Governor LeMarchant’s concern for the outports was well-founded. Throughout the summer, much as in the previous year, reports from the fisheries were dismal. In August, James Walsh of remote Merasheen Island in Placentia Bay wrote to Rev. Troy in St. John’s describing the cod season at Merasheen, currently nearing its end: “For the greater part of the summer those who caught any fish thought themselves well off to have the offal, that is, the head and bones, to live upon.” He stated that “in nine cases out of ten,” the families ate offal “without a bit of potatoe or bread to take with it, barely seasoning it with a little salt.” In cases “where the family was large, the fish they took little more than kept them alive, eating it as it came out of the water.”34

29 Walsh adds that “There are some too, who, without an atom of fish, have contrived to live, I know not how, having nothing on earth to eat but a little green cabbage, with a grain of salt.” Walsh then asks, “But what are they to do in the winter, if they can preserve existence until then? May God help them, if their fellow creatures in St. John’s will not be touched by the grace of charity, and come to their relief.”35

30 Similarly, on 7 September a resident of Trinity forwarded a letter to the Public Ledger stating, “The cod fishery may now be considered as brought to a close for this season, and a most miserable wind-up it is.” And the failure of the fishery was not the only concern in Trinity. Until September, the potato blight appeared to have been confined to Newfoundland’s lightly populated southern shore. St. John’s and the bays to the north had been spared. The letter broke the alarming news of a new outbreak, that the blight had reached Trinity Bay and all its neighbouring coves and was “rapidly progressing.”36

31 On 15 September the St. John’s Morning Courier reported that the blight had also reached Bonavista Bay. Additionally, the newspaper confirmed that “In Trinity Bay the distress is most appalling; of a population of 8,801 upwards of two-thirds are bordering on starvation.” The paper then explained that “We have been creditably informed, that in Hants Harbour in this bay, out of 80 houses, a whole biscuit, or a pound of flour is not to be found in half.”37 The same week, the Public Ledger reported, “The accounts which we hear of the distress and destitution in the district of Fogo and Twillingate are absolutely painful, and the prospects of the poor for the means of subsistence during the coming winter it is impossible to contemplate without the utmost possible anxiety.”38 The Times of St. John’s expressed a similar anxiety about conditions in the outports. Its primary concern, however, was not the destitution itself, but the likelihood that St. John’s would receive “an influx of paupers from these Outports before the winter finally sets in.”39

32 As September progressed, conditions throughout Newfoundland only worsened. On 18 September, the Times reported the arrival of blight in the fields near the capital. “One of our highly-respected fellow-townsmen” has just discovered his potato fields, which had “never been known to fail, are now completely affected by the destructive inroads of the blight.”40

33 Despite the widespread reports of starvation, the Times remained leery of government intervention. The editor did not totally oppose relief, but urged restraint in the expenditure of public funds and insisted that “unless some better and more stringent rules be adopted, the whole of the lower classes will become beggars by profession, and every principle of independence destroyed.” In support of its assertions, the newspaper stated that “It is notorious that some are not as active, as industrious and provident, as they ought to be.” The editor claimed that “to such an extent has indolence prevailed, in certain quarters of our shores, that persons have been known to bask in the noon-day’s sun during the very height of the fishery!”41

34 As the weeks passed, the news from the potato fields grew increasingly grim. And it became ever more apparent that the colonial government, with a treasury already depleted because of the tragedies of the past year, would have difficulty providing sufficient relief, even if it chose to do so.

35 In light of this daunting prospect, on 6 October the citizens of the Conception Bay community of Carbonear held a public meeting “for the purpose of bringing under the consideration of the government the total failure of the Potato crop in this district, and the state of thousands of persons thereby rendered destitute of the means of subsistence.”42 Two weeks later, a similar meeting was held in nearby Harbour Grace. Both meetings concluded with decisions to prepare petitions addressed — not to the Governor or to Lord Grey, the Secretary of State for the Colonies — but directly to Her Majesty, Queen Victoria.

36 The petition from the citizens of Carbonear asserted that, because of the total failure of the potato crop and partial failure of the fisheries, they “have every reason to believe that they shall be visited by famine in its dismal form before the month of January next unless immediate means be adopted to bring some cheap and wholesome food for the people of this extensive Bay.”43 The petition from Harbour Grace, similar to the one from Carbonear, explained that “for some years past the Fisheries have greatly failed in this neighborhood,” and that “a new and still more trying visitation” has recently befallen them in the destruction of the potato.44 Both petitions were signed by leading members of the communities: prominent merchants, representatives of the clergy (both Catholic and Protestant), and the editor of the Harbour Grace Weekly Herald.

37 It is not clear exactly what the petitioners anticipated from the Queen or if, in fact, they even expected their petitions to reach her personally. Victoria had ascended to the throne in 1837, at age 18. By 1847, the United Kingdom was a constitutional monarchy, the Queen’s powers were largely ceremonial, and the monarchy was facing multiple problems, not the least of which was the Great Famine in Ireland, then in its third year. To the Queen, or to any government official, a plea for relief from citizens of what must have appeared to be a remote bay across the Atlantic would not likely be a priority. Perhaps more importantly, the petitioners from Carbonear and Harbour Grace may not have recognized the significance of Parliament’s amendments to the Irish Poor Law in June — provisions that effectively ended the era of public relief in Ireland, and adopted the principle that the Irish must find the means to resolve their problems on their own.45 At least in hindsight, it seems unlikely that the British government would take a different approach to the crisis looming in Newfoundland.

38 On 13 October, while the petition from Carbonear was pending and a week before the petition from Harbour Grace had been drafted, the Times in St. John’s finally faced the growing reality and acknowledged “with deep and sincere regret” what it described as “the awful ravages which the ‘taint’ is making amongst the potatoes in this Island.” The editor stated that “It is not a difficult matter to understand how hardly this calamity will press upon the poor.” Nevertheless, the Times, much like the British government at this time, maintained its opposition to public relief and expressed its scorn for the petitioners from Carbonear who “not only sought assistance from His Excellency [the Governor], but, as we understand, besought him to transmit a petition to the Queen.”46

39 On 23 October, the Times wrote again about the potato blight. This time, it acknowledged a new and ominous development: potatoes that had remained healthy through harvesting were now becoming infected. As the Times described it, “even after the root has been dug and housed in an apparently sound condition, the ‘taint’ makes its inroad, and blackness and rottenness succeed.” The editor conceded that “its failure must entail a vast amount of misery upon this Island.”

40 Once again, however, the Times discouraged government relief and proposed its own solution to the shortages. The editor began by asserting that “this misery will be, in some degree, alleviated by the energy and kindly feelings of the Governor we are sure; but we urge upon all, and especially upon our poorer fellow-colonists, the absolute necessity of the strictest economy.” Without specifically mentioning the Petition to the Queen, the editor then insisted that “the poor in the mother country have much more of evil to contend with.” As for Newfoundlanders, the Times claimed that “with a proper husbanding of their present resources the distressed in Newfoundland may, under the kind and fostering care of the local government, ‘weather the winter’; and that by a ready obedience to the law, — an honest desire to work, — and a resolution to bear up under the pressure of unexpected evil, they will be brought through this trial.”

41 The Times concluded with a cheery assessment. “Let us look at the brighter side of the picture: it is only three or four months before our hardy sealers will again be in full employ.” Without providing any examples, the Times announced that “even in the interim, there is many an opportunity for an honest man to provide for his family.”47

42 By contrast, on 27 October, the editor of the Harbour Grace Weekly Herald expressed only despair. He explained that, “Taking the newspaper Custom House reports for our guide there is not, at this moment, three weeks provision in the colony. This is awful.” The editor added, “We were assured on Monday last by a most respectable inhabitant of Lower Island Cove, (Mr. William Wilshire), that long before Christmas the people in that part of the District will not have a morsel to put in their mouths. The potatoes are gone; literally vanished; they are left undug, or thrown up in putrid heaps, poisonous to the very hogs that are suffered to touch them.”

43 The editor asks, “Is his Excellency apprised of it? Does he know of a certainty what has been ordered by the Trade — what may reasonably be expected? One thousand barrels of meal per week are scarcely sufficient to keep life in the people of this bay alone. Where is this to come from?”48

44 November arrived with an ever deepening sense of gloom. The Public Ledger reported on 2 November that “upwards of seventy individuals have within the last few days arrived from Burin . . . .” According to the newspaper, they arrived “for the purpose of throwing themselves upon the Government bounty for subsistence during the winter.” In response, the Public Ledger insisted that “there can be no shelter for them here in so inclement a season.” Consequently, “it has been resolved to send them back again, and a vessel has been accordingly chartered for that purpose.” The newspaper added the meagre assurance that “A supply commensurate with the very limited means at the disposal of the Executive will no doubt be apportioned to the actual sufferers in that district.”49

45 On a more positive note, the Public Ledger announced that “a vessel arrived from the United States, last evening, containing 2,000 barrels of Indian meal to government account.” Nevertheless, the newspaper cautioned, “as there are several districts to be relieved, it will be understood that the greatest economy must be exercised in the distribution of this relief.” As if that warning wasn’t enough, the newspaper added: “Any idle and thoughtless reliance therefore, upon government aid, it would be obviously unsafe to cherish.”50

46 On 28 November, Robert Lowell, a missionary serving in Bay Roberts, sent a desperate plea addressed to the “Editor of the Daily Advertiser (Boston, Massachusetts) and any others in the United States.” At the time, Lowell had temporarily left his position in Bay Roberts to visit his home in Massachusetts before returning to Newfoundland.

47 Lowell titled his letter “Famine in Newfoundland”:

To the Editor of the Daily Advertiser, and any others in the United States

FAMINE IN NEWFOUNDLAND

The people of this country, who heard with so much sympathy and answered so cordially the cry of the famished in Ireland, may, it is hoped, not turn away from the appeal of the wretched much nearer home.

It comes from a rocky island, at almost five days sail from Boston. . . . The people there are fishermen, eighty thousand of them, — and their summer’s fishery like that of last year, or to a worse extent, has been a deplorable failure. Their wives and children, in their absence on the sea, planted the scanty seed which had been hoarded from last year’s wreck; and the rot has already made fearful ravages of the only staple crop of the Island.

The Newfoundlanders have now no resource but charity. They cry from the shore of the land which this year gives them no food, for help, or they must perish. . . .

Let the charitable reader then, — if he has no better way of sending it, entrust his money, or food, or clothing, to the undersigned, who will forward and account for it. Whatever may be received . . . will be sent to the proper authorities to be distributed without distinction of any sort, except degrees of wretchedness.

Robert Lowell

Late Missionary in Newfoundland,

now at Cambridge, Mass.

Nov. 28, 184751

48 In the meantime, both of the petitions from Conception Bay to the Queen had found their way across the ocean. They had not only found their way to London but, according to the report received by the Governor, had reached the Queen herself. And the Queen, it was reported, was pleased to receive them “very graciously.”52 As the petitioners quickly discovered, however, there is a difference between receiving a petition graciously and responding graciously to its contents. The Queen’s response to the citizens of Conception Bay, as published in the St. John’s newspapers, was in the form of a letter signed by Newfoundland’s Colonial Secretary, James Crowdy.

49 Crowdy’s letter, dated 18 December 1847, is essentially a letter of rejection. He “expresses his earnest hope that . . . the resources of the Colony within itself, may be sufficient to meet the impending calamity.” Much like the British response in this same year to the crisis in Ireland, Crowdy added that “the People of Newfoundland . . . must rely on their own energy and frugality to meet the trials which are inevitable when it pleases Providence to withhold the usual supply of Food.” Although denying any immediate relief for Conception Bay, Crowdy’s letter did contain a long-term plan: a future increase in agriculture, particularly in agricultural variety. In the meantime, the only immediate remedy he could propose was harder work and greater frugality, and the hope that “by the blessing of Providence” the hungry will “in a short time be placed in a condition of independence and comfort.”53

50 To the editor of the Harbour Grace Weekly Herald there was something familiar in Crowdy’s response. The denial of relief, the urging of frugality, and the proposal to expand agriculture were the long-standing positions of the colonial government in St. John’s. As such, Crowdy’s letter raised the question of whether the response to the petitions did, in fact, express the considered view of Lord Grey, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, or the Queen herself. Instead, the editor of the Weekly Herald suspected that, in conveying the petitions to London, the officials in St. John’s had included their own views, thereby undermining the petitions and generating the negative response that they themselves desired.

51 In its first edition of the new year, 5 January 1848, the editor assailed the “knot of small politicians” in St. John’s he believed to be responsible for the denial of relief, the “men utterly incapable of conducting the petty business of a third rate counting house, to say nothing of governing the affairs of this Colony.” He stated, “We look these men in the face, and we tell them now what we foretold them many weeks ago — that thousands of our population in this bay are in a starving condition — that it is painful — distressing — harrowing to meet them in the street — to have them at our doors — to see them fainting at our hearths.”

52 The editor warned that even the successful merchants in Conception Bay were on the brink of collapse, that “in a few days more the most affluent among us will be brought down to the same common level” as everyone else. He then added, “But who are the really affluent in the Colony? Who are those upon whom the Home Government enjoins the duty of relieving the destitute? Who, but those who with fixed and exorbitant salaries, have been placed beyond the surge and pressure of the times?” And in his final attack against the officials in St. John’s — those he believed had denied relief for the people of Conception Bay — the editor stated: “But what have they given, pray, towards the relief of their perishing fellow creatures? NOT ONE FARTHING! ! ! !”54

53 As it turned out, the suspicions of the editor were correct. In submitting their petitions to the Queen, the petitioners followed established protocol and first presented the petitions to the Governor, along with their request that he forward them to the Queen. (In a similar manner, the Governor was required to present the petitions to Lord Grey, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, with a request that he, in turn, present the petitions to the Queen.) When the delegation from Carbonear met with the Governor to present their petition to him, the Governor pledged that he would “do all in his power for the poor of Conception Bay.” Most significantly, the Governor assured the petitioners that, in forwarding the petition to the Queen, he would “give it his support.”55 Instead, Governor LeMarchant did the opposite.

54 In a letter dated 18 October 1847, addressed to Lord Grey, the Governor wrote that he had the honour “to transmit to your Lordship the accompanying Petition to be laid before Her Majesty the Queen, which was placed in my hands . . . by a Deputation from the Town of Carbonear.” (In a postscript dated a day later, the Governor added that he had just received another petition “of the same purport and character” from the Town of Harbour Grace.)56

55 In his letter, the Governor stated that it behooved him to place the Secretary “in full possession of the actual state and future prospects of this Country generally, as well as of this particular District, now appealing to the Home Government for assistance and support.” The Governor then vigorously maintained that the residents of Conception Bay, contrary to the assertions in their petitions, were instead living in a “state of comfort,” that there was no “direct appearance of poverty,” that even the poorer classes of residents were “well and comfortably clad.” Furthermore, and in conflict with the reports from all Newfoundland newspapers, including those most supportive of the Governor, he insisted that in the season just concluded, “their Fisheries have been more than ordinarily productive.”57

56 The Governor did acknowledge the failure of the potato crop in a few settlements in other bays, including at Burin and in Fortune Bay, and reported that those communities were on the brink of starvation. The Governor explained to Lord Grey that he had ordered “a large supply of Indian Meal” from the United States for the settlements deemed to be in need, but only to be distributed in exchange for labour on the roads and other public projects, and purchased entirely with funds already at hand.58 As for the petitions for relief from Conception Bay, the Governor recommended total denial59 — a goal that he consequently achieved.

57 Left to their own resources as the spring 1848 sealing season approached, the merchants and fishing families in Newfoundland continued their internal debate over the role of government and the cause of famine. The Newfoundlander again insisted that the current suffering was brought on by the “improvidence” of the sufferers themselves. The solution? According to the Newfoundlander, the cure for improvidence was to impose even harsher conditions upon the fishing families, including a significant increase in berth money charged to the sealers in exchange for the “privilege” of participating in the spring hunt.60 This burden would constitute a reversal of the success achieved in several sealers’ strikes in the last few years61 and, in effect, take more from the fishing families and give more to the merchants.

58 As its editorial of 20 January explained, “[T]he risk of the supplying merchant, both in the Seal and Cod fisheries, is overproportioned to his chance of success. . . . Before a vessel can leave the merchant’s wharf, she must not only be fitted out with every description of gear appertaining to her own particular use, but must be furnished with an abundance of provisions for any given number of men.” The Newfoundlander then added, “Great as this is already, however, the prevalent system of supply demands a still larger expenditure — the men are to be provided with as large a stock of clothing as they are disposed to take, and their families are to be supported during their absence.”

59 The Newfoundlander acknowledged that a reduction in the “heavy advances of the employer to the employed” would, at first, “bear heavily upon many who, from their previous improvidence, might be unprepared to meet it.” The newspaper insisted, however, that a reduction in advances to the sealers and fishing families would enforce “habits of forethought and economy in the future management of their affairs.” By bearing a portion of the merchants’ costs in advance, they “would be taught to calculate a little in advance, and to husband some part, however small, of the earnings of one year to meet the exigencies of the next.”62

60 While the Newfoundlander, along with other St. John’s newspapers, insisted that conditions were too easy for those who fish, rather than too harsh, a second, related theme emerged. According to an analysis published on 9 March in the form of a letter to the Newfoundlander, instead of widespread famine during the past season, there was actually “little suffering” experienced by what was termed the “labouring classes.” In a letter signed only by the name “Observer,” the dire forecasts were described as exaggerated. The writer insisted that, in contrast to the desperate warnings from across the island, “no one has died from starvation.” The writer proceeded to congratulate His Excellency, the Governor, for “resisting the clamour which pressed upon him with extravagant demands.” As the writer explained, “Mere eleemosynary relief was peremptorily forbidden, except in cases of infirmity or advanced years.” And by denying demands for government relief, “Thus were the people relieved from the degradation of living on public charity, and this pernicious principle successfully resisted.”63

61 Regardless of the “Observer’s” opinion of government relief, his assertions that there was “little suffering” and that “no one has died from starvation” seem questionable. The number of deaths is a matter that would be unknowable to the writer at that time, given the absence of wintertime communication throughout much of the island, especially from the remote outports. But most significantly, the claim that no one died mistakes the actual causes of death during times of famine. As noted by historians of the Irish Potato Famine, death from famine is caused most frequently not by direct starvation, but by the diseases that fatally attack weakened and malnourished populations before starvation itself can produce death — diseases such as typhus, relapsing fever, dysentery, measles, scarlatina, consumption, and smallpox.64

62 In fact, the outbreak of fever was a dominant theme in Newfoundland newspapers throughout 1847.65 Much as with the Irish Potato Famine, the precise number of famine-related deaths in Newfoundland can never be known, but from the many heart-rending accounts of hunger and hunger-related disease, the number of deaths from the famine in Newfoundland must have been significant.

The Recovery

63 In the spring of 1848, while understating the extent of the current suffering, the Newfoundlander acknowledged the critical need for a successful seal hunt. On 16 March, the newspaper stated: “This spring’s adventure is one of immense importance to the Country. Never in its history, we believe, was there a deeper or more universal anxiety for the result, for never before did it appear to involve more momentous considerations.”66

64 A week later, in its edition of 23 March, the Newfoundlander delivered good news: “The Sealers are dropping in every day, and up to this time, all well fished. They report most cheeringly of the prospects.”67 Throughout the spring, results from the ice continued to be favourable. By 20 April, the Newfoundlander was able to announce, “It has, indeed, been an excellent fishery — the best, we believe, since the spring of 1831.”68

65 The good fortune continued beyond the spring. The successful seal hunt was followed by a promising beginning of the summer cod fishery. As early as 16 May, the Royal Gazette printed a report from “A gentlemen recently arrived from the Western Shore.” The report contained the welcome news that “The fishery has commenced very favorably in Placentia Bay, and especially from Oderin to the Ram Islands, where fish is unusually plentiful, particularly at Paradise Sound and Isle of Valen.” The report then added, “A few boats belonging to Burin had been to Cape St. Mary’s, and returned with trips of from 15 to 25 qtls. each.”69

66 As the season progressed, even more encouraging reports arrived. On 8 June, the Newfoundlander stated, “We learn that the Fishery to the Southward and Westward has been so far unusually good — the last accounts say, the best known for many years.”70 On 27 June, the Royal Gazette announced “that favourable accounts of the success of the cod fishery continue to be received from various parts of the coast, north, south and westward.”71 The Royal Gazette continued to report the abundance of cod to be taken, limited only by the ability to process the catch. As stated on 11 July, “By an arrival yesterday from the Western Shore, we learn that the Cod Fishery in and about Placentia Bay continues to be very prosperous; but that salt is extremely scarce.”72

67 On 19 July, the Weekly Herald announced that the arrival of large quantities of cod extended beyond the local inshore fisheries. “A schooner belonging to Mr. Clement Noel of Carbonear arrived from Cat Harbour [now Lumsden] a few days since, bringing very good accounts of the fishery on that part of the coast.” The Weekly Herald added that “intelligence has been received in St. John’s from Labrador, which affords much hope of the result of the voyage in that quarter also.”73

68 By 20 July, the Newfoundlander could not only announce a successful fishery, but also a promising agricultural crop.74 In September, therefore, when the Weekly Herald confirmed what many had feared — the recurrence of the blight75 — the colony was better prepared. By this time, both private and public efforts to encourage the production of a greater variety of crops had begun to produce results.76 As a consequence, when the potato blight struck again in 1848, although serious, the impact was less severe. The disease arrived following a successful seal and cod fishery, as well as at a time when the island was becoming less dependent on the single agricultural crop.

69 On 20 November the Newfoundland Agricultural Society released its annual report. The report noted the expansion in the growth of wheat, barley, and oats, “notwithstanding the recurrence of the potato disease, by which many persons have again suffered, though to an extent much less than heretofore.” The report urged the construction of more mills to process the grains, as well as the completion of roads “enabling cattle to be driven to St. John’s at all seasons, especially early in the spring, when meat is scarce and dear.”77

70 The newly elected House of Assembly convened in St. John’s on 14 December. The session began with an address by Governor Le-Marchant. The Governor recounted the now familiar refrain: “the greatly distressed condition of the trade of this town and colony generally arising out of the train of disasters (fire and gale) that afflicted us in the year 1846.” He then added that the disasters and resulting obligations on the government to provide relief “were further enhanced by the additional losses suffered in the failure of the fisheries and destruction of the potato crop of the following year.” As a result, “The state of the economy at the approach of last winter was such as to demand our most anxious care and vigilant attention for the preservation of the very existence of a large portion of the population, and more especially those dwelling in the remote settlements of the Island.”

71 To save the population — and without mentioning his denial of relief to Conception Bay — the Governor explained that “all the resources of the government were devoted, and by the blessing of Divine Providence not unsuccessfully.” He then congratulated himself for what he asserted to be the successful distribution of relief, claiming “I am thankful to have it in my power to state that the loss of a single life was prevented, although so large a mass of the population were dependent on the government for their daily subsistence.”78

Conclusion

72 The Governor’s statement that the famine in Newfoundland did not result in “the loss of a single life” repeats the claim, originating in the Newfoundlander of 9 March, that during the winter of 1847–48 “no one died from starvation.” As previously noted with reference to the Great Famine in Ireland, this claim overlooks the actual causes of death during times of extreme hunger: the diseases that attack malnourished populations before starvation itself can produce death.

73 Further comparisons to the Irish famine are also significant. Unlike in Ireland, the immediate cause of the Newfoundland famine was not the failure of the potato crop alone, but the convergence of a series of misfortunes that culminated with the failure of the potato. Also, unlike in Ireland, the surviving records in Newfoundland contain no references to workhouses or soup kitchens, and there was no period during the Newfoundland famine when government relief was totally denied. Recovery in Newfoundland was faster and, less burdened by overpopulation, the colony did not experience the mass evictions or mass emigration that dramatically impacted the Irish. Yet the official position of many government leaders and the newspapers that reflected their views were strikingly similar, with the Times of London, much like the Times of St. John’s, insisting that the famine was a gift from an all-merciful Providence — a gift delivered to cure the moral defects of an indolent and improvident people.79 It is also disturbing to note the shipping records that confirm that during both famines, even at the height of starvation, large quantities of food continued to be exported from both islands: grain from Ireland, fish from Newfoundland.80

74 Placed in perspective, the massive scale of the Irish famine more than justifies the intense interest and volume of studies it has produced. By contrast, the famine in Newfoundland is still a largely unexplored area of scholarly research. Perhaps the official position that no one died in Newfoundland is the reason why so few data appear to have been compiled. And with few data, perhaps little can be written. Yet the many heart-rending accounts of hunger and hunger-related disease that appear in the Newfoundland newspapers from this era suggest that death from famine may have been widespread.

75 Governor LeMarchant’s attempts to obscure this history, with his assertion that no one died, need not go unchallenged and awaits further study, along with many other aspects of the famine and the controversies it generated. For those of us with a Newfoundland heritage — and to others interested in this intriguing but troubling history — we honour our forefathers and foremothers by renewing these efforts to understand the hardships they endured.