Articles

Association Football in St. John’s:

The Pioneer Years, 1870–1896

Introduction

1 This article examines the pioneer years of Association football in St. John’s, Newfoundland.1 St. John’s is a relatively small city and perhaps not of much importance as far as football is concerned. Yet, its football history is worth reconstructing for at least three reasons. First, football played a noticeable role in the social life of St. John’s in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Second, although academics over the last three or four decades have come to recognize that writing sports history can be a serious intellectual activity, little or nothing has yet been written about sport in Newfoundland.2 This article begins filling this lacuna by focusing on the pioneer years of football in St. John’s. Third, writing about football in St. John’s is not simply writing local history because, as sport historian James Walvin argued, a national or global history of football, or any other sport for that matter, can only be built on local histories, or, to put it in a more scientific language, generalizations can only be developed from specifics.3

2 The time period examined here extends from the early 1870s to 1896. This period spans the time from when the game of football, understood as both Association and Rugby football (as well as variations thereof), first arrived in St. John’s, to when a football league of seven teams was established. The sources used to reconstruct the history of football in St. John’s in those early years are very limited, consisting almost exclusively of newspapers articles, a few secondary sources, and some archival material held at the Centre for Newfoundland Studies of Memorial University.4 The article is divided into four parts. The first section provides some hypotheses about the origins of football in St. John’s between the beginning of the 1870s, when football began to be played in St. John’s, and 1878, the year in which local newspapers first began reporting about it. These hypotheses are based on what is known about the early developments of football in England as well as the first reports found in local newspapers and some primary sources. The second part examines the various football clubs (five in particular) that existed and competed against each other and against the crews of visiting ships from the late 1870s to the mid-1880s, when the popularity of football underwent a decline. The third section analyzes the characteristics of football as it was played in St. John’s in those early years. A fourth part looks at the decline of football in the second part of the 1880s, offers a hypothesis on the reason for such a decline, and then examines its renaissance in the early 1890s due primarily to the decision of the city’s denominational elite academies or colleges to make football part of their curriculum. The article ends with some concluding remarks.

The Kick-off

3 Very little is known about the origins of Association football in St. John’s. That very little, moreover, comes from a single source, an article signed “On-looker” that the Evening Telegram published in June 1922 to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the St. John’s Football League.5 The article is a review, that is, a summary and commentary, of the first year of operation of the league in 1896 and begins with a few words about the origins of football in St. John’s. Most likely, it is a reprint of the review of the year in football that was published in November of 1896, in the first issue of a publication called Illustrated Sporting Annual. This publication contained, as mentioned in the local press at the time, a review of each of the major sports, including Association football, and summarized the activities of each of them for 1896.6 Unfortunately, a copy of this issue could not be located in any of the archives in the city. It is almost certain, however, that the article the Evening Telegram reprinted in 1922 is precisely the review of Association football published by “On-looker” in the Illustrated Sporting Annual of 1896. The newspaper called it both a “review” and a “résumé” of the 1896 year in football, and it appears to have been the only source for a short article on the origins of football in St. John’s written in 1901 by the then secretary of the St. John’s Football League, W.J. Higgins, some sentences having been lifted almost verbatim from it.7 According to “On-looker,” in 1878 “J.C. Strang . . . instituted the Association Game in Newfoundland and [came therefore to be] known . . . as the Father of Association Rules in Terra Nova.” Strang and a few others enthusiasts organized the Terra Nova Club, a.k.a. Gemmell’s men.8 The club, which besides football occasionally played cricket and rugby, took its name from the Terra Nova Foundry and Boiler Works established by Mr. McTaggart and Mr. Hugh Gemmell in 1875 in the east end of the harbour, an area originally known as Maggoty Cove and by the 1870s as Hoylestown, and, more precisely, in the area between Hill of Chips and Temperance Street. In 1878, Mr. McTaggart withdrew from the partnership and Mr. Gemmell continued to operate the foundry as sole proprietor, hence the club’s nickname “Gemmell’s men.”9

4 The first football match recorded in the local press was played on 8 July 1878:

The remark that this was “the first Foot Ball match for the season” suggests that other matches of football — understood in the larger sense of the term, that is, including not only Association football but also Rugby football as well as variants of both codes — had been played before 1878. In the chapter devoted to sports in his voluminous history of the city of St. John’s, Paul O’Neill wrote: “The first mention we have of soccer in St. John’s is the formation of the St. John’s Football Club on March 21, 1873.”11 O’Neill does not provide the source of his information but there is evidence of the existence of this club in a letter its officers sent to local newspapers in the spring of 1873 to solicit donations for the purpose of holding a Youth Athletics Sports Day. One of the sports on the program was: “kicking the foot ball.”12 The type of football played by this club appears to have been more akin to rugby than to Association football, at least according to a handwritten note contained in the Graham Snow Collection, which reads: “1873 Football (rugby), June 18 first match of the season, St. John’s FC vs. HMS Sirius + Woodland, 15 members on each side.”13 This evidence is not conclusive, however, because at that time the difference between various football codes was still tenuous. Even if in England the Football Association (FA) and the Rugby Union had adopted their distinct codes in 1863 and 1871, respectively, on the playing fields it took some time before the two games became completely distinct and for the many variants of both codes to fade away. At the end of the 1860s, for instance, the FA still had only 30 clubs while the Sheffield Association, which played under slightly different rules, had 27.14 Indeed, in the United Kingdom as a whole, the FA and the Scottish, Irish, and Welsh associations did not reach agreement on a uniform code until December 1882 and the International Board, which would have (and still has) final authority on the rules of the game, was not formed until 1886.15 In some parts of England (e.g., Sheffield, Cambridge, Brighton), even if the rules of the game played were essentially those of the Association code, they retained elements of what would become the Rugby code. Points, for instance, could be obtained not only by making the ball pass between the goal posts but also by scoring a “rouge,” that is, by making the ball pass between designated areas on either side of the goal posts.16 Also, the number of players varied. Both in Sheffield and in Glasgow, it was not unusual, at least until the late 1860s and early 1870s, to have matches of 10, 14, 15, and even 16 a side. On 26 December 1860, for instance, a match between Sheffield FC and Hallam FC (probably the very first football derby in history) was played with 15 a side and lasted until it got dark.17

5 If it took some time for the Association football and Rugby codes to be widely accepted in Great Britain, their variants likely survived even longer outside it. Not surprisingly, in St. John’s, the Terra Nova club played at least two matches in 1883 and 1884 according to Scottish Association rules.18 Athletes, moreover, were versatile and willing to play both codes as well as their variations. Thus, it was not unusual for British Royal Navy ships that docked in St. John’s to have local papers publish a notice in which they challenged local clubs to a game of football specifying that they would be prepared to play either Association or Rugby codes. Sometimes, one match was played with Rugby rules and the return match with Association rules.19 Some matches were even played under one code for the first half and the other for the second. So it can be said that football (spelled also foot-ball and foot ball) began to be played in St. John’s under both Association and Rugby codes, as well as variations or combinations of these, at some time in the early 1870s, at about the same time as it did in other parts of the British Empire.20

6 The reasons why there are no mentions of, let alone reports on, any football matches in the St. John’s press before 1878 can only be surmised. At the time St. John’s could boast a considerable number of daily papers.21 All of them, however, consisted of two sheets or four pages, one or two of which contained advertisements. The remaining pages were devoted mostly to commentaries on local politics — most of the newspapers, after all, were little more than the mouthpieces of local politicians or individuals who aspired to be elected to public office — and some news agencies’ reports on European politics. The space devoted to local events was very small, usually about half a column, and contained primarily announcements of the time of arrival and departure of boats and the time and place of meetings of various local associations and organizations. It was in this space, at the end of the 1870s, that some local newspapers began to announce, and occasionally also report on, football matches. In all likelihood football had been introduced on the island in the late 1860s or very early 1870s, but at first it would have consisted primarily of occasional kick-about among sailors or recent immigrants from Great Britain. Towards the end of the 1870s, however, football appears to have become more organized, with groups of friends who worked for the same business — as in the case of the Terra Nova Foundry and Boiler Works — or who were members of the same fraternal or athletic association organizing on a more permanent and formal basis by creating football clubs. As a result, public interest in football increased and newspapers concluded that the sport deserved some attention. This does not mean that newspapers began to employ sports reporters but simply that they began to publish announcements or reports provided by officers, or simply members or supporters, of the football clubs playing a given match. The report of the 8 July 1878 match between Terra Nova and the Avalon Cricket Club, mentioned above, appeared in exactly the same words in both the Morning Chronicle and the North Star, which suggests that someone linked to one of the two clubs submitted the text to the two papers. The football community, as it were, was still relatively small and hence communications were at times rather cryptic except for the members of that community. The Evening Telegram of 18 November 1887, for instance, announced: “The foot-ball match that should have taken place yesterday, will be played to-morrow at the usual time and place.” Finally, it should be noted, St. John’s newspapers usually used the term “football” indistinctly to indicate not only the two sports known today as soccer and rugby but also variations of both, which were common at the time. They did not always specify the code under which a particular match was going to be, or had been, played. As late as 1894, a reader signing himself “HALF BACK” wrote a letter to a local newspaper in which he complained about an article published a few days earlier in which football had been described as a “brutal sport” and compared to “prize fighting.” He asked himself whether that article had been “taken from an American paper,” and hence referred to American football, since anyone familiar with “football as it [was] played on the other side of the ‘herring pond’ . . . would not have the audacity to write such a thing.” He concluded by quoting extensively those Association football rules designed to prevent violence among players.22

7 To conclude, since announcements and reports of football matches depended primarily on the initiative of the clubs themselves and the term “football” was used in an all-encompassing manner, it is difficult to determine for the period examined here exactly how many organized Association football matches were played and under which rules any particular match was played. Appendix 1 offers a list of organized football matches that were mentioned in the local press. For most of these matches the press provided a very short report, often simply the final score, as well as some clues to the code under which they were played, while for others the announcements were limited to noting that a match had been scheduled for a certain date but did not follow up with a report. One can only assume that some of these matches were either cancelled (due to the weather or some other reasons) or that the clubs simply did not care, or forgot, to send a report to the press. It is also very likely that during this period at least a few other matches, of which there is no record, were played.

The Early Clubs

8 Football, at least the type played primarily according to Association rules, can be said to have begun taking root in St. John’s in the early 1880s. The first local newspaper to devote attention to it was the Evening Telegram, the only paper of the many that existed at the time to be still in print today (although with the abbreviated name of the Telegram). It began publication on 3 April 1879 and it first mentioned football on 20 June 1879. This was a brief, paid announcement simply stating: “The Terra Nova football club will meet for practice at 7 o’clock this evening on the Parade ground. A full attendance is requested. By order of C. McLarty, Secretary.” At that time, the Terra Nova Rangers might have been the only organized football club in the city, but the sport was undoubtedly becoming a topic of interest, or at least curiosity, because the newspaper thought the paid announcement to be newsworthy and repeated it in the same issue in its column on local events.23 A report of what was probably one of the first international, as it were, Association football matches played in St. John’s appeared a few days later: the Terra Nova Rangers played and defeated (the score, however, was not reported) a team from HMS Zephyr.24

9 Little is known about the identity of the Terra Nova players, except their names (see Appendix 2).25 The bits and pieces of information that have been uncovered suggest, however, that at least most of them26 were engineers or skilled workers employed at the foundry and that they hailed primarily from Scotland. This is hardly surprising, since British professionals (civil servants, garrison officers, engineers, doctors, teachers) and sailors introduced football in most of the countries around the world and founded the first local clubs. At first, membership in these clubs was reserved, with very few exceptions, to British expatriates. It took some time before locals began to be accepted into these clubs.27 Things were not very different in St. John’s, even if here the locals were just as British as the recently arrived expatriates, except for the Irish, who might have felt differently.

10 To take root and thrive, however, football needs more than the occasional challenge provided by sailors of the Royal or Merchant Navies putting in at port. To thrive, football needs permanent local rivalries. These did not take long to develop in St. John’s. The early pioneers eagerly sought new recruits, as one can gather from a notice in a local newspaper in September 1880: “All young men who are desirous of joining in a game of Foot-ball are invited to come to Back Harbor Green, where practice is held every evening at 7 o’clock.”28 By the early 1880s, four clubs, besides Terra Nova, were active in the city: the Mechanics, Cathedral Works, the Natives, and Victoria Rangers. The Mechanics was the club of the Mechanics Society, an Irish fraternal society of skilled tradesmen founded in 1827.29 The club seems to have played cricket much more often than Association football. The press of the time mentions it only three times with reference to football: to report a defeat by 1–0 in a match, played on 15 October 1884 against the Victoria Rangers, and to announce two matches against the sailors of the HMS Tenedos for 6 June and 22 August 1885.30

11 Cathedral Works, also known as Red Cross, was a club formed in July 1883 by skilled stone workers who had come to St. John’s from Great Britain to complete work on the Anglican Cathedral. It could count on a number of members who had played Association football for different clubs back home.31 Such wealth of experience must have given it a considerable advantage over the local opponents: Cathedral Works appears to have played only five matches over the course of the summers of 1883 and 1884 and won them all, outscoring the opposition 12 goals to one. On 11 and 22 August and again on 27 October 1883, the club defeated the Terra Nova Rangers three times, by scores of 2–1, 2–0, and 1–0.32 These victories seem all the more significant if one considers that, according to “On-looker” at least, the Terra Nova club “had marked success being victorious in the majority of games played,” although he does qualify his assertion by adding that the victories came “principally against teams from the different warships at the station.”33 In its account of these matches, the Evening Mercury did not provide comments on the performance of Cathedral Works. For some reason, it chose instead to focus exclusively on the performance of the Terra Nova players. Willie Power was selected as the star of the first match, having been “much admired by the spectators for his dribbling and dodging,” while J.C. Strang, the founder of the club, “distinguished himself ” in the second. As for the third match, the paper simply reported that it had been “very evenly contested.”34 In the other two matches Cathedral Works played during its brief existence, it defeated the Victoria Rangers and a team from HMS Tenedos by scores of 2–0 and 5–0, respectively.35

12 Another club in existence in St. John’s in the early 1880s was the Natives. Notwithstanding its name, this club had no direct connection with the Newfoundland Natives’ Society since the latter had officially ceased to exist in 1863. Its creation, however, seems to have been inspired by the same motivations.36 The club, in fact, embraced the same political message as that of the Natives’ Society, namely, that ethnic origins and denominational affiliations had to be set aside if one wished to advance the interests and careers of native-born Newfoundlanders. The Natives’ football club, in other words, can be said to have continued the struggle of the Newfoundland Natives’ Society, which wished to give a chance to Newfoundland-born individuals to reach the higher echelons of public life, and applied it to football. Native Newfoundlanders quickly took to football and were eager to play it competitively. They must have found it difficult, however, to be admitted as members into the Terra Nova, a club founded and run by local Scottish expatriates, the same way as their fathers and grandfathers, 30 years earlier, had found it difficult to gain access to posts in public administration. Hence, less than a year after the formation of the Terra Nova team, they set up a club of their own. Membership depended only on place of birth: Newfoundland. In this respect, the Natives were the Newfoundland expression of a phenomenon that was to take place in other countries as well. The Natives, in other words, were the predecessors in St. John’s of clubs like Nacional in Montevideo, Stade Français in Paris and Independiente in Buenos Aires. As Goldblatt points out, these clubs “were created in opposition to English [British would have been a more appropriate adjective] dominated clubs in their cities and inevitably came to carry a nationalist flag onto the pitch.”37

13 At first, the Natives seem to have played, or perhaps simply practised, between themselves.38 Eventually, they ventured to play Terra Nova, which proved to be too strong for them. In their first match, on 15 September 1883, Terra Nova humiliated the Natives, 9–0. According to one report, “the ball never went into the Terra Nova’s half ”; according to another, it did so only once.39 The Natives did a bit better, losing by a score of 2–0 on 24 May 1884, and a year later, on 20 June 1885, they lost again, by a score of 4–0. In the 1884 game the Terra Nova goalkeeper touched the ball only twice, whereas in the 1885 game, he “never handled or kicked the ball during the whole game.”40

14 The fourth football club active in those pioneer years, most likely set up in 1880, was the Victoria Rangers. This club seems to have had all the right characteristics to develop an intense rivalry with the Terra Nova Rangers. First, the members of the two clubs were employees of two rival companies because the Victoria Rangers was the club of the Victoria Engine and Boiler Works, owned by Halifax-born James Angel, which was the main competitor of the Terra Nova Foundry.41 Second, they were also geographical rivals since the Terra Nova Foundry was located at the eastern end of the harbour (Hoylestown) while the Victoria Engine and Boiler Works was located at the western end (Riverhead). In the 1880s and 1890s, football matches, especially Rugby football, between teams calling themselves East and West were common in St. John’s and thus an indication of the existence of an identity cleavage between the two parts of the city.42 Third, while Terra Nova had primarily a Scottish identity, the Victoria Rangers club seems to have had more of an English and Irish one, which, given the breakdown of the population at the time, also suggests that most of the players were very likely born in Newfoundland.43 Notwithstanding the presence of all these elements conducive to a heated rivalry, the Victoria Rangers did not meet the Terra Nova Rangers on a football field until 23 June 1883, when the two clubs faced each other on the Parade Ground in what was described as an “exciting” match that ended in a draw, the precise score not being specified.44 The two clubs met again a year later, on 28 June 1884, on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s sixty-fifth birthday. This match, played at the cricket ground in Pleasantville on the northeast shore of Quidi Vidi Lake, was undoubtedly considered a major event since it received quite a bit of attention in the press. It ended in a 0–0 draw, yet it must have been rather exciting since the Evening Telegram called it “one of the sharpests [sic] contests in the annals of local sport.”45

15 Most likely, it took some time for the two clubs to play each other because in those days people did not have much free time that could be devoted to recreational activities. The workweek consisted of 10 hours a day for five days a week plus Saturday mornings. Since playing on Sundays was frowned upon, to put it mildly, there was very little leisure time one could devote to football and, except on Saturdays, it was basically confined to evenings. In Newfoundland, of course, the problem was compounded by the weather, which meant that the football season was limited to evenings and Saturday afternoons during the three summer months. Football, moreover, had to compete for both playing time and athletes with the more established cricket and, therefore, it took time for clubs to agree to play a match on a date and at a time convenient to both of them.46 It was not uncommon, moreover, for some players not to show up and for their teams to play one or two men short or to recruit volunteers to replace the absentees from among the members of the public attending the match.47

16 The record shows that the Victoria Rangers played their first match at Quidi Vidi on 28 July 1880 against a team called All Comers, i.e., an improvised team made up of anyone eager to enter the field and test his football skills.48 After that, the Victoria Rangers seem to have played two matches in 1882, both against the Natives (a 0–0 draw and a 1–0 win) and two in 1883 (the first against Terra Nova, which ended in a draw, and the second against Cathedral Works, which, as noted above, ended in a 2–0 defeat).49 In the late summer of 1884 there seems to have been much expectation in the city for a return match between the Victoria Rangers and Terra Nova after their draw on 28 June. A reader signing himself “Muldoon,” for instance, wrote the following letter to the Evening Mercury:

Although there was an effort by both clubs to arrange a return match on a mutually acceptable date, it must have been unsuccessful because there is no record of another match between the two clubs. Terra Nova arranged instead a match against the Natives to be played on 23 August.51 It is unclear, however, whether or not it took place since there is no record of it. The Victoria Rangers, for their part, played the Natives on 24 September (a 1–1 draw) and then on 15 October, although one man short, they beat the Mechanics.52

17 On 11 June 1885 the Victoria Rangers played the squad of HMS Tenedos, which beat them by a score of 2–0. The diatribe that followed shows how Newfoundlanders were eager to stand behind local teams whenever they played against visiting, foreign ones and, hence, how football both reflected and strengthened a distinctive Newfoundland identity. The Evening Telegram in its report of the game wrote: “The Tars got the ball easily into two goals, and, in fact, it is stated that there were two of their number — one being the captain — who alone could have held their own against the combined strength of their opponents.”53 This comment led a reader to send a letter of protest in which he argued that at least five of the Victoria Rangers could easily stand up, one to one, to the Tenedos captain. If the Rangers had lost, he added, it was only because “six or seven h[ad] had very little practice” and “this was the first foot-ball they had ever played on.” Last but not least, he blamed the timekeeper for robbing the Rangers “out of, at least, fifteen minutes time.”54 Less than two months later, however, Newfoundlanders could rejoice for not one but three victories by natives over foreigners on the same day:

It is interesting to note that even if most of the Terra Nova players were born in Scotland they were considered natives for this occasion (they had played and beaten a team “come from away”). The use of the term “habitants,” of course, would have been more appropriate but the fact that they had chosen to work and reside in Newfoundland made them, in this context at least, natives.

18 After 1885, visiting ship teams were met not by individual local clubs, but by a City Scratch team, i.e., a team composed of players selected for that specific occasion, which also included players who were born in Great Britain but resided in St. John’s. One could suspect that this change occurred to increase the likelihood that “natives,” understood in the larger sense of “habitants,” would prevail against visitors. Regardless of whether or not this consideration played a role, the change was primarily due to the fact that, as will be shown below, in the second half of the 1880s most football clubs dissolved.

19 Native pride led to the organization in the summer of 1894 of two matches between two select teams that were dubbed Natives and Aliens. Although these were the first Association football matches organized along this identity cleavage, other sports had already organized matches between similarly styled teams.56 The fact that different matches often pinned Natives against non-Natives was not simply due to the fact that a match is more interesting if the two contenders boast characteristics that set them apart. If this were the only reason, one would have seen many more matches of East vs. West and Bachelors vs. Married men, which were also occasionally played. That the cleavage Natives vs. non-Natives was chosen more often points to the fact that such a cleavage was a salient one and would arouse more public interest than others. In the two football matches played in the summer of 1894 between the Natives and the Aliens, the latter won both of them, by scores of 3–1 (according to the Evening Herald) or 2–1 (according to the Evening Telegram) and 1–0. Before the match, the local press pointed out that although the Natives would meet the “boys from the land of the heather and the land of the rose . . . a hard-fought battle [wa]s anticipated.” In the first match, the Natives apparently “showed up well in the first half . . . kicking against the wind and scoring one goal . . . but in the second half . . . they seemed to lose heart, and the Aliens gained three goals in succession.”57 Although there were no incidents, the contest must have been hard indeed, especially in the return match, since the press went out of its way to emphasize that the two teams bore “kindly feelings one to the other . . . the distinguishing name being rather as a stimulus to action and interest than to in any way create any feeling whatever approaching hostility.”58

20 In the second half of the 1880s, Association football underwent a temporary decline in St. John’s, at least in regard to organized competitive matches. This decline, however, did not last very long because in the early 1890s the local denominational elite academies or colleges included the game in their curriculum and thus gave it a much more secure foundation. Before we turn to examine this period, however, a few remarks on how the game of Association football was played in the 1870s and 1880s are in order.

Association Football as Played in the Pioneer Years

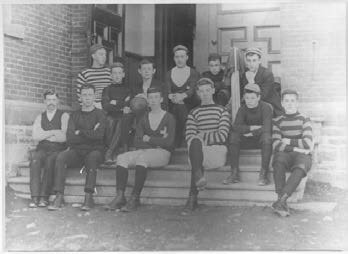

21 That the game of football as played in its pioneer years had little resemblance to either the game of soccer or that of rugby as played today has already been mentioned. This fact can be grasped easily by looking at the picture below (Figure 1).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

22 This undated photograph was taken at the Pleasantville ground on the northeast shore of Quidi Vidi Lake, as can be deduced from the hills visible in the background. The caption tentatively identifies the team portrayed as “the Victoria Rugby team.” A copy (or the original) of the same picture, held at the Rooms Archive, and printed in reverse of that held at Memorial, states that it depicts “a St. John’s team” after a rugby match against the naval men of the HMS Cordelia and dates it as having been taken sometime between 1896 and 1898. Nothing in the picture, however, allows for any certainty as to whether this was a match of Association football or Rugby football or a variant of either code. A number of reasons suggest that the information provided in both copies of the picture is wrong.

23 First, the local press never mentioned the Victoria Rangers in connection with rugby. Second, in the late 1890s, the Pleasantville ground was used exclusively for cricket. Third, all Rugby and Association football matches, including those that the HMS Cordelia played in St. John’s between 1896 and 1898, were played in fields located in the city.59 Fourth, two balls, one deflated, are visible in the centre foreground of the picture. The balls are sewed in a pattern that resembles the wedges of an orange, an example of which is the ball featured in the logo of Tottenham Hotspur FC. This was the type of ball used until the end of the nineteenth century. The fact that the ball is round does not definitively establish that this was an Association football match since the oval ball did not become compulsory in Rugby football until 1892. Before that, there was not much difference, if any, between the balls used in Association football and those for Rugby football. Had the photo been taken between 1896 and 1898 and had this been a rugby match, however, one would have expected to see an oval ball. Fifth, one can see that the goalposts are considerably thinner than those of today and a tape (until 1872 it was actually only a string) — barely visible in the picture — was used instead of a crossbar, the latter having been introduced only in 1882, the same year in which it became compulsory to mark clearly the boundaries of the playing field with white lines. Until then flags, quite a few of which are visible in the forefront of the picture, were used.60 The goalposts extend above the ribbon, suggesting this might have been a rugby match. Yet, both the length of the goal and the height at which the ribbon is placed suggest it was an Association football match. The rule establishing that the goal posts should be 24 feet apart was introduced in 1863 but it was only in 1882, when the crossbar replaced the tape, that the FA specified that it should be eight feet high. Sixth, no goal net is visible in the picture but this does not prove it was a rugby match since goal nets in Association football, which in England came into use in late 1891, would not be adopted in St. John’s until 1898.61 Seventh, the uniforms of the players do not tell us the nature of the match either since both Rugby and Association football players dressed, at least in the early days, the same way as they would if they were playing cricket: long trousers, flannel shirts, usually white but occasionally of other colours, caps (first used to distinguish individual players and later the teams), and heavy boots. Had this photo been taken between 1896 and 1898, the uniforms would have been rather similar to those worn today, as confirmed by many other pictures of football or rugby teams taken in the late 1890s. Finally, the statement that this was a rugby match seems to be based exclusively on the fact that 14 players are visible in the picture, as suggested also by a notation in the picture held at the Rooms Archive indicating that “one player [is] missing from the photo.”62 Yet, we know that the number of players on both Rugby and Association football teams in their very early days could vary.63

24 All of these facts point to the conclusion that this picture was taken not in the late 1890s but several years earlier, in the late 1870s or very early 1880s at the latest, and that it is probably the very first picture of a football team (the term “football” being understood in its largest sense to include both Association and Rugby codes and their variants) taken in St. John’s.

25 Other characteristics distinguished the type of football played in those pioneer years from that of today. There was no referee with final authority. Instead, two umpires, one drawn from each team, watched the action from the sidelines and intervened only when one of the two captains called their attention to a rule infringement. The umpires were usually chosen among the players that were either injured or had been left out of the lineup for some other reason. Thus J.C. Strang, the founder of Terra Nova, acted as an umpire in the game against Cathedral Works on 11 August 1883 but was on the field for the return match on 22 August.64 The referee, as one understands the term today, first appeared in England in the late 1870s. The presence of a referee became the norm in 1881, at first simply to make a final decision when the two umpires disagreed and later, in 1898, as the sole and final arbiter of the game. Penalty kicks were introduced only in 1887. Until then, a foul committed to avoid a probable goal was awarded a goal. Football teams held practice sessions but had no formal coaches. The captain of the team, especially on the field, provided directions to his teammates at least insofar as the team could be said to act as a collective, which, as discussed below, was rarely the case. In any event, the captain — who was elected by the members of the team at the beginning of the season — played a much more central and significant role than is the case today. Perhaps the last football captain who played a role similar to those played by the early ones was Johan Cruyff, especially during his years at Ajax Amsterdam (1964–73). The dimensions of the playing fields varied considerably. In Great Britain they tended to be larger than they are today (up to 180 metres long and 90 metres wide). In St. John’s, instead, they appear to have been smaller than the contemporary standard dimensions (105 x 68 metres). The fields also seem not to have been perfectly level since reports of matches often mentioned which team began the game kicking uphill or downhill. In Great Britain the length of a match was set at 90 minutes in 1877, but in St. John’s it appears that, at times at least, they lasted longer. A report of a match played in November 1886 states, for instance, that “owing to the brief time for play in the afternoon the match lasted only an hour and a half.”65 As late as 1893 a match between a local team called Rovers and a squad from the HMS Blake was reported to have lasted “about two hours.”66

26 The style of play in these early days was pretty rudimentary and rather rough. Playing tactics were basic, to say the least: most if not all players operated as forwards, the only defender being the goalkeeper, who, at the time, could handle the ball anywhere on the field and wore a shirt of the same colour as that of his teammates, at least once team uniforms were introduced, which in St. John’s only happened in 1897. The different shirt for goalkeepers became the norm in 1909 and the restriction that he could handle the ball only in his penalty area was introduced as late as 1912. The role of the goalkeeper was certainly not distinctive, as it would eventually become. Thus, it is not surprising to see players who were goalkeepers in one match play as forwards in another or even change position during the same game.67 The game consisted basically in chasing the ball: one player dribbled forward while all his teammates followed hoping to recapture the ball in the event that the dribbler lost it. The task of the opposing team was to gain control of the ball. When this happened the chase would resume in the opposite direction. The game was referred to as “the dribbling game” since this was pretty much the only activity in which players engaged even if, more than dribbling as the term is understood today, it was simply head-down charging. Success, therefore, depended as much on the size and strength of the players as on their skills. The ball was rarely, if ever, passed to teammates for two reasons. First, the ball could be passed only backward or laterally because any player of the team in possession of the ball was considered to be offside if positioned ahead of the ball. This rule, called Law Six of the 1863 Association rules, remained in place until 1866 when it was changed to allow forward passes as long as there were at least three defenders between the player passing the ball and the one receiving it. Second, and this attitude lingered even after the rule was changed, passing was considered “unmanly,” indicating “failure, even dishonour.”68 It was in Scotland that what came to be called “the passing game” was first developed. The major reason was that north of the Hadrian wall, the offside rule was much less stringent than in England, a forward being offside only if he was both behind the penultimate man of the opposing defence and in the final 15 yards of the field. By the mid-1880s, the English also came to recognize the superiority of the passing game over the dribbling one. This happened for at least two reasons. First, in their international matches in the 1870s, the Scottish players, who “were over a stone lighter” than the English ones, managed to do much better than expected. Their passing game, in fact, allowed them to go around the English players rather than taking them on frontally, a contest in which they would have been unlikely to come out as winners. Second, in the 1880s, teams from the north of England, composed in large part by Scottish professionals, became dominant and hence set the standards for how the game was played.69

27 In St. John’s, not surprisingly given the Scottish character of two of its first clubs, the Terra Nova Rangers and the Cathedral Works, which included quite a few Scots, players seem to have adopted, or at least strived to play, the passing game from the very beginning. This is confirmed both by the lineups reported in the press, which suggest that teams played with the typical 2–2–6 Scottish formation, and by the fact that, in the press at least, the quality of games was judged on the basis of the frequency and accuracy of passing (also known as combinations, scientific game, or united action) or the lack thereof. Thus, when the Terra Nova Rangers beat the HMS Tenedos in August 1885, the Evening Telegram noted that their victory was due to their “combined and close play.” Commenting on the loss of the Natives to the Aliens by the score of 1–0, in the summer of 1894, the same paper pointed out that the game of the Natives, although showing “almost marvellous individual kicking,” had suffered from “a lack of combination.”70 Not surprisingly, another characteristic of the football played in St. John’s was what the non-English-speaking world in general and the Italians in particular call “English fair play,” which could be defined as fairness and honour in dealing with the opposition. Thus, for instance, sending the ball into touch when under pressure was regarded as ungentlemanly play.71

28 One final characteristic of the St. John’s early football scene deserving attention is the social extraction of the players. The early footballers in St. John’s shared the same social characteristics as those playing in England outside London, in places like Sheffield and later Lancashire and Staffordshire.72 They were, in other words, schooled professionals and skilled tradesmen, as shown by the telling name of two of the early St. John’s clubs, Mechanics and Cathedral Works, as well as by the fact that both the Terra Nova and Victoria players were mostly engineers or skilled workers at the two major foundries in the city. Less is known about the Natives, but it is reasonable to assume that their social profile was the same as those of the other players.

Decline and Resurgence

29 In the second half of the 1880s the popularity of Association football in St. John’s seems to have faded away, at least judging by the declining number of matches reported in the local press. “What’s the matter with the Foot Ball Clubs?” asked the Evening Telegram of 8 October 1886:

The piece elicited a response by a Terra Nova club member who lamented: “We can get no team to play us.”73 This is not surprising since it appears that the Victoria Rangers had already disbanded (or gone “up the spout” as the same paper put it) at the beginning of the season, the last mention of the club in the local press being dated 26 June 1886. It was an announcement of a practice to be held on the Parade Ground two days later. The announcement did point out, even if indirectly, that the survival of the club was in question since it added: “It is hoped that all the members who intend retaining their connection with the club will be in attendance at 7 o’clock, sharp.” It would appear, although we do not know the reasons why, that not many members chose to do so.74 The Natives must have been disbanded at about the same time, as suggested by the fact that they too ceased to be mentioned in the press.75 In the 1885 season, the Terra Nova Rangers, as stated in the club’s offi-cial report, played five matches.76 The following year, given the difficulties of getting a game, the club decided at its annual general meeting that if “the Rugby clubs w[ould] arrange for a match, they w[ould] play one game Rugby rules [while] the return [would] be according to the Association code.”77 With the exception of one match announced, but probably not played, between Terra Nova and the HMS Emerald in July 1888 and some calls to attend scheduled practices, football was hardly mentioned in the St. John’s newspapers for several years after 1886.78 Cricket continued to enjoy its traditional status as the most popular sport in the city.79 In July 1883, the first match of lacrosse was played in St. John’s. Cycling races made their appearance and so-called “walking matches” became increasingly frequent.80 Most interesting, however, is that the decline of Association football seems to have coincided with a rise in the popularity of Rugby football, which in St. John’s was also colloquially known as “kicking the cod” and “rushing the waddock.”81 On 5 November 1887, for instance, the Evening Mercury wrote: “A game of [Rugby] football was played yesterday on a field near the New Era Gardens between scratch teams. Why do not the young men of the town form a football club and thus give interest to their matches[?]” This suggestion seems to have been immediately picked up because only a few days later the same paper reported that “a football club” had been formed “to play under rugby rules” and that “it was named the St. John’s Football Club.”82 Other rugby clubs mentioned in the local press in the late 1880s were St. Mary’s, Caledonia, and some with exotic-sounding names of North American Indigenous tribes, such as the Minnehaha and the Kickapoo.83

30 In 1891, two Association football matches were played at Quidi Vidi between the HMS Pelican and the Scotia club, which apparently was active only that year and about which no information is available. Scotia won the first match and tied the second (1–1), which, according to the Evening Herald, was “the best contested game of Association football played [in St. John’s] in a long time.” This remark must be taken with a grain of salt, however, because very few matches were played between 1885 and 1893.84 The Terra Nova Rangers played some matches under Rugby rules and were reported to have scheduled an Association match on 5 July 1892 against an unidentified team. The match, however, was postponed for unspecified reasons.85 In July 1893, they did play a match under Association rules with a new club called Rovers whose members were also, for the most part at least, employees of the Terra Nova Foundry. They must have been the only two clubs playing Association football by this time since the match was announced as one that would “decide which holds the city championship.”86 In March and April 1894, the Terra Nova Rangers played one match against a new club formed by the Scottish St. Andrew’s Society, whose players “were all Scotchmen — drapers from the Water street stores.”87 They also planned at least three other matches, though no additional record of these matches has been found. The club must have disbanded soon afterwards because its name disappears from the local newspapers.88

31 The press does not offer any explanation of, nor does it provide any clue to, the decline in popularity of Association football in the second half of the 1880s. The most likely explanation is that by this time most of the members of the first generation of Association football players in St. John’s had come pretty much to the end of their playing careers. Since the major clubs were formed by employees of manufacturing companies, it is very probable that the number of retiring footballers was higher than that of newly hired employees. The clubs, moreover, had no reliable system in place to nurture young talent (i.e., they had no youth teams). Some players, of course, remained active, but not in sufficient number to keep all the clubs that operated in the first part of the decade alive.

32 In the second half of the 1880s, however, while most of the pioneer players and the clubs they had formed faded away, Association football slowly began to acquire new practitioners and followers and thus established the basis of its own resurgence in the second half of the 1890s. In his 1896 review, “On-looker” explained the resurgence of football in the early 1890s as being due “to school, college, factory and warehouse” or, more precisely, to “the arrival of young men to the mercantile firms and the return from college of boys belonging to Newfoundland families.”89 Other factors, however, also played a role. One of the most popular summer activities in St. John’s in the 1880s was the organization by local businesses, associations, societies, unions, etc. of excursions “’round the bay” for their employees or members and their families. The excursions were advertised well in advance in the local papers and each organization had its own preferred destination, the most popular ones being Topsail, Manuels, Kelligrews, Harbour Grace, and Bay Bulls, the latter two usually reached by boat. Games of football between improvised teams and played on makeshift fields figured, often prominently, among the activities of the day. These matches could become very competitive, as happened in Harbour Grace in July 1885 when “a football match between two teams chosen from among the excursionists . . . took place in the afternoon at the Racehorse but owing to some dispute between the combatants the match was not finished.”90 Besides being evidence that the game was taking root more widely, at least at the purely recreational level, the matches played during these excursions also contributed to bringing the game to smaller communities outside St. John’s.

33 The employees of local St. John’s commercial businesses, those of department stores in particular, began to play football on a more regular basis and not only during the “’round the bay” excursions. The first recorded football match between two such commercial sides took place in 1893 between the employees of two of the major stores in the city, Ayre & Sons and Monroe, which also had a political overtone as can be gathered by a comment in a local paper: “Some of the Ayre and Sons’ men say that they will be satisfied if they can give the Hon. M[oses] M[onroe]’s party as good a beating to-night as he himself will surely get at the coming election.”91

34 Less than a year later, the Monroe men played the Knowling Athletic Club. The press did not report the result of the match but pointed out that these emerging rivalries would help “cement the kindly feelings of good fellowship among the young of this city.”92 The technical quality of these games must have left much to be desired, as can be gathered from the comments made about the playing style of the Knowling men in a match against St. Andrew’s: “They made some very rough play during the last of the time and seemed to be carried beyond all prudence in their wild kicking at the ball making it very dangerous of the opposing side.”93

35 Even more important for the future of Association football in St. John’s was the fact that in the late 1880s football became very popular among children, as suggested by a letter sent to one of the local papers in January of 1889. A member of the George Street Methodist Church complained to the editor that “on the congregation leaving the church they were greatly annoyed by a crowd of boys kicking football in and out among the congregation as they were returning to their homes.”94 What is of even more importance in indicating the popularity of the sport among children is that this episode happened on a Sunday and in the dead of winter. At Christmas the same year, the Rev. J.J. McGrath — guardian of the St. Thomas’ Home, Villa Nova Parish in Topsail — in a letter to the same paper acknowledged the gifts of several donors to the orphan boys of the parish, including “a beautiful foot-ball” donated by a Miss Gleason.95 Playing football appears also to have been the favourite recreational activity during picnics organized by youth groups.96 The increasing popularity enjoyed by football among youth, moreover, was not limited to St. John’s. Other urban centres were experiencing the same phenomenon. In Carbonear, for instance, a local paper asked: “Where were the policemen on Monday when a crowd of young men and boys were kicking football on the public street, persons passing by being in danger of getting hurt? Some having to stop for five minutes to pass. This has occurred here several times, and should be put a stop to.”97

36 The most important factor for the resurgence of organized football, however, was its introduction in the late 1880s among the pupils of the St. John’s elite denominational academies and colleges, namely the Church of England Academy or CEA (renamed Church of England College in 1892 and then Bishop Feild College in 1894), the Methodist College, and the Catholic St. Bonaventure’s College (better known as St. Bon’s). These schools adopted football in their curriculum for the same reason as English public schools had, namely, they regarded sport as an important component of a good education. This is not surprising if one considers that most if not all of the teachers in the St. John’s elite colleges came from, or had been formed in, England (or Ireland in the case of the Catholic ones). Hence, they brought with them the view that sport was “a major contributor to the development of character.” The Christian Brothers who, by the end of the century, ran St. Bon’s “advocated erudition predicated on a healthy body and a healthy mind.” The principal of Bishop Feild College wrote in one of the school’s annual reports: “It is in the playfield that boys acquire the power of becoming leaders.”98 This made a whole generation of pupils and students interested in football and, once out of school, they went on to form alumni (or old boys’) football clubs that would recruit their new players among the students coming out of their alma mater, thus replicating what had happened in England. Schools, moreover, explicitly encouraged, and clearly expected, graduates interested in continuing playing to do so for their school’s old boys’ association. The Methodist College, for instance, wrote in its school magazine: “When our boys leave school, they should at once, join the senior club which represents their college.”99

37 Organized matches between the pupils of different schools seem to have begun in November 1889 when the CEA succumbed by a score of 2–1 to St. Bon’s but defeated the Methodist College by 2–0 a week later.100 A more detailed record exists of a school match played on 28 November 1891 between the CEA and the Methodist College. According to the Evening Telegram, “although the Methodist College side was perhaps heavier, yet its members did not appear to be so well acquainted with the game as did their opponents, the skilful combination and passing of whom soon began to battle their defence.” The CEA won easily, 6–0.101 In this match, the CEA had its principal, William Blackhall, and a teacher, Mr. Lloyd, in its lineup, thus confirming the argument forcefully advanced by soccer historians J.A. Mangan and C. Hickey that schoolmasters contributed greatly to the spread and popularity of the game not only in England but also abroad.102 A year later, on 19 November 1892, the CEA played St. Bon’s, winning by a score of 4–0. This time, both schools included some teachers in their lineups.103 Then, on 10 December of the same year, the CEA boys took on a team composed of Alumni of English Colleges and beat them 5–0.104 Although the local press paid only occasional attention to the interscholastic game, it seems that these matches were played rather regularly by the early 1890s. In her biography of Robert E. Holloway, the Methodist College principal, Ruby Gough writes that in 1894 the Methodist College “won the [intercollegiate football] championship” (see Figure 2), which might better be expressed that the College was the self-proclaimed city champion.105

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

38 An Intercollegiate League was not officially established until 1899. As Gough explains, a “cause for celebration before the year’s [1899] end was the winning of the silver cup for football, the first year the cup had been awarded.”106 Thus, any 1894 title was “unofficial,” meaning simply that the College won most of the occasional games it played against the other denominational schools. In the absence of a league, friendly games were organized on a bilateral basis and haphazardly, that is, not all teams played the same number of matches, and the winner received only bragging rights for a year (the picture shows the team without a trophy).107

39 The spread of football to the local elite colleges also led to new playing fields being developed in the city. In the 1870s, football was played on the Parade Ground that was part of Fort Townsend. After the British garrison was withdrawn from St. John’s in 1871, the fort was allowed to decay. The Parade Ground, located south and east of where Merrymeeting Road, crosses Parade Street, became a “common” and the only public place where sport could be played in the city. This meant that it soon fell into a “disgraceful state,” being all “cut up by car-ruts running in all directions.”108 Hence, at the end of the 1870s, a field was established in Pleasantville at the east end of the northern shore of Quidi Vidi Lake, basically where the Caribou softball complex and indoor soccer facilities are located today. The Pleasantville field (referred to frequently as Quidi Vidi) was used primarily for cricket but football matches soon moved there, where they remained until the very early 1890s. This ground had a number of advantages: it was bigger than the Parade Ground and level, it had a grandstand capable of seating hundreds, and it had a hotel nearby where visiting teams could be, and often were, entertained and where spectators could go and “quench their thirst.”109 It also had, however, a major drawback: it was more than three kilometres from downtown, beyond what were then the city limits, and difficult to reach, except on foot, because the road around the lake was narrow and often in very poor condition.110 Thus, some people felt that a new field within the city precincts was needed. Some suggested that it should be built in Bannerman Park while others thought the Parade Ground could be easily refurbished through a small government grant and a percentage of the gate receipts of the local sports clubs.111 Potential sites were often offered for lease and advertised in the local papers. In November of 1886, for instance, the Evening Telegram advertised for three days in a row that a “meadow” located “in rear of the Parade Ground . . . would make a good Foot-ball or Cricket ground” and was for lease.112 During the 1880s, almost all the matches mentioned in Appendix 1 (at least those for which the field was indicated) were played at Quidi Vidi. A field located just off Freshwater Road called the New Era Pleasure Grounds, which was probably what today is known as the Ayre Athletic Grounds, was also used, as were Banner-man Park and, at least once, the Government Meadow.113

40 In the 1890s, as the colleges began to play football, a few new grounds were developed. The CEA (later Bishop Feild) played near Avalon Cottage, the original location of the school. This field, just off what is today King’s Bridge Road, was “far from level and . . . much too small for the proper development of soccer and cricket teams.” Thus, it was eventually extended to its north side to include part of the estate of the Hon. A.W. Harvey, an old Feildian who gave permission to the school’s principal, Mr. Blackhall, to move his fence back “any distance [he] like[d].” Then, in 1895, the school signed a five-year lease “for a large piece of property” located at the intersection of what today are Forest Road and Forest Avenue. The new field “was named Llewellyn Place (or Grounds) out of respect for Bishop Llewellyn Jones.”114 St. Bon’s used its own ground, which was bigger than the children’s play-field one can see today, and occasionally also the nearby Shamrock Field (where the Merrymeeting Sobeys’ store is located today). The Methodist College also had a field of its own — sometimes called by the local press Methodist Park and at other times Methodist Institute — although it is not clear where it was located. The Evening Telegram of 14 July 1894 referred to it as being “near Parade Ground,” which means that it might have been the “meadow . . . in rear of the Parade Ground” that the same paper had advertised as being for lease in November 1886. Two matches were played at Lash’s Field, on the north side of Merrymeeting Rd. The St. John’s Football League would later use the Llewellyn Grounds in its first three years of operations (1896–98) but move to Lash’s Field, which had been renamed St. George’s Field, in 1899. The most popular facility, used also by non-school teams, was a field called simply “the Institute,” which the press reported as being located “at the top” or “at the head” of Hamilton Street in a place known as “Poken Pass” — this most likely meant the north side of what today is Hamilton Avenue and the eastern side of Bennett Avenue in the area where the Grace Hospital would eventually be built.115

41 By 1895, football had become popular again, so much so that the Evening Telegram wrote, not without some surprise, that notwithstanding the bank crash of the previous year, “sport and pastimes in the city [were] liberally patronized; the popular games of cricket and football being almost a ‘craze’ with all classes.”116 New football clubs were formed, such as St. Andrew’s, and the alumni of the denominational schools soon organized new clubs linked to their respective schools from which they would, each year, recruit new players. Proof of this “craze” is seen in local press coverage: no news reports exist of Association football matches played in 1887 and less than a handful can be found for the period 1888–93, but 18 matches are reported to have been played, or planned, in the summer and fall of 1894 and 13 matches are noted for the same period in 1895. Hence, it is not at all surprisingly that the following year, in 1896 — only eight years after the formation of the first football league in England and six years after that in Scotland — a similar league was organized in St. John’s.

Conclusions

42 The sport of football, understood in its larger sense (i.e., both Association and Rugby codes as well as their variations), seems to have arrived rather early in Newfoundland, most likely in the late 1860s or early 1870s. It took some time for Association football to become clearly distinct from Rugby football and for all their variants to disappear. Once this happened, the Association code seems to have enjoyed more popularity than that of Rugby, with the exception of a short period in the second half of the 1880s. At least five clubs were active in St. John’s between the end of the 1870s and the mid-1880s. Two clubs (Terra Nova Rangers and Victoria Rangers) were associated with local iron works companies, one (Mechanics) with a local self-help and educational Irish society, another (Cathedral Works) was composed of British skilled workers who were putting the finishing touches to the Anglican Cathedral, and yet another (Natives) was a club reserved to native Newfoundlanders. Although suffering a temporary decline in the second part of the 1880s, football made a recovery in the 1890s once the local elite denominational colleges made the sport part of their curriculum. This would lead to the formation of alumni clubs and, finally, in 1896 to the launching of a St. John’s Football League (i.e., an organized summer competition) only eight years after the formation of the English Football League (1888) and six years after the Scottish one (1890).

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank various members of the St. John’s football community who have kindly put up with my questions and patiently listened to my summaries. I am also grateful to my wife, Rosemary Thorne, as well as the editor and copy editor of Newfoundland and Labrador Studies and to three anonymous reviewers, who have greatly contributed to improve my final text.

Notes

Appendix 1: Matches Held in St. John’s before 1896A1

| Date | Teams | Ground | ResultA2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1878 | |||

| 6/8 | Terra Nova – Avalon Cricket Club | Parade | 0–0 |

| 1879 | |||

| 6/24 | Terra Nova – HMS Zephyr | Quidi Vidi | n.a. |

| 8/26 | Terra Nova – HMS Zephyr | Quidi Vidi | |

| 9/10 | Natives 1 – Natives 2 | Parade | n.a. |

| 9/24 | Natives 1 – Natives 2 | n.a. | |

| 1880 | |||

| 7/28 | Victoria Rangers – All Comers | Quidi Vidi | 2–0A3 |

| 1882 | |||

| n.a.A4 | Natives – Victoria Rangers | n.a. | 0–0 |

| 9/6 | Natives – Victoria Rangers | Parade | 0–1 |

| 1883 | |||

| 6/23 | Terra Nova – Victoria Rangers | Parade | draw |

| 8/11 | Cathedral Works – Terra Nova | Quidi Vidi | 2–1 |

| 8/22 | Cathedral Works – Terra Nova | Quidi Vidi | 2–0 |

| 9/5 | Cathedral Works – Victoria Rangers | Quidi Vidi | 2–0 |

| 9/15 | Terra Nova – Natives | Quidi Vidi | 9–0 |

| 10/27 | Terra Nova – Cathedral Works | Quidi Vidi | 0–1 |

| 1884 | |||

| 5/24 | Natives – Terra Nova | Quidi Vidi | 0–2 |

| 6/7 | Cathedral Works – HMS Tenedos | n.a. | 5–0 |

| 6/28 | Victoria Rangers – Terra Nova | Quidi Vidi | 0–0 |

| 8/23 | Terra Nova – Natives | Quidi Vidi | |

| 9/24 | Victoria Rangers – Natives | Quidi Vidi | 1–1 |

| 10/15 | Victoria Rangers – Mechanics | Quidi Vidi | 1–0 |

| 1885 | |||

| 6/6 | Mechanics – HMS Tenedos | Parade | |

| 6/11 | Victoria Rangers – HMS Tenedos | Quidi Vidi | 0–2 |

| 6/13 | Terra Nova 1 – Terra Nova 2 | Quidi Vidi | |

| 6/20 | Terra Nova – Natives | Quidi Vidi | 4–0 |

| 7/4 | Terra Nova – Victoria Rangers | Quidi Vidi | |

| 8/22 | Mechanics – HMS Tenedos | New Era Pleasure GroundsA5 | |

| 8/29 | Terra Nova – HMS Tenedos | Quidi Vidi | 3–0 |

| 1886 | |||

| 5/15 | Terra Nova – Scratch teamA6 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 11/27 | Terra Nova – Scratch team | Quidi Vidi | 2–0 |

| 1887 | |||

| No games reported in the local press | |||

| 1888 | |||

| 7/17 | Terra Nova – HMS Emerald | n.a. | |

| 1889 | |||

| 11/2 | C.E. AcademyA7 – St. Bon’s | n.a. | 1–2 |

| 11/9 | C.E. Academy – Methodist College | Bannerman | 2–0 |

| 1890 | |||

| 8/23 | Terra Nova – HMS Pelican | Quidi Vidi | |

| 1891 | |||

| 6/11 | Scotia Club – HMS PelicanA8 | n.a. | n.a. |

| 8/26 | Scotia Club – HMS Pelican | Quidi Vidi | 1–1 |

| 10/9 | St. John’s Selects – HMS Emerald | Quidi Vidi | |

| 11/28 | C.E. Academy – Methodist College | n.a. | 6–0 |

| 1892 | |||

| 11/19 | C.E. College – St. Bon’s | n.a. | 4–0 |

| 12/10 | C.E. AcademyA9 – Alumni English Colleges | n.a. | 5–0 |

| 1893 | |||

| 6/3 | Rovers – HMS Cleopatra | Quidi Vidi | n.a. |

| 7/1 | Rovers – HMS Blake | n.a. | 0–1 |

| 7/20 | Terra Nova – Rovers | Institute | n.a. |

| 8/25 | Ayre & Sons – M. Monroe | Institute | n.a. |

| 9/4 | Terra Nova – HMS Cleopatra | Institute | 3–0 |

| 1894 | |||

| 3/17 | Terra Nova – C.E. Club | Methodist | |

| 4/4 | Terra Nova – Unidentified team | ||

| 4/25 | Terra Nova – Terranova’s crewA10 | Lash’s field | |

| 5/8 | C.E. College – Scratch team | Lash’s field | 1–0 |

| 6/13 | Aliens – Natives | Institute | 2–1A11 |

| 6/19 | Knowling AC – Monroe | n.a. | 2–0 |

| 6/29 | St. Andrew’s – HMS Cleopatra | Institute | 3–0 |

| 7/6 | St. Andrew’s – Knowling AC | Institute | 3–1 |

| 7/7 | Rovers – HMS Cleopatra | Quidi Vidi | |

| 7/10 | Aliens – Natives | Institute | 1–0 |

| 7/24 | St. Andrew’s – Rugby Union Club | Institute | |

| n.a. | Terra Nova – St. Andrew’s | Institute | drawA12 |

| 7/27 | St. Andrew’s – Rovers | Institute | 0–1 |

| 8/3 | M. Monroe – Ayre & Sons | Institute | |

| 8/7 | St. Andrew’s – Rovers | Institute | 2–1 |

| 8/14 | M. Monroe – Ayre & Sons | Institute | |

| 8/23 | St. Andrew’s – Rovers | Institute | |

| 11/9 | Bishop Feild – City Scratch | n.a. | 1–2 |

| 1895 | |||

| 1/1 | HMS Tourmaline – City Scratch | Methodist | 1–1 |

| 4/6 | Rugby Union – HMS Tourmaline | Methodist | 0–1 |

| 4/18 | HMS Tourmaline – City Scratch | n.a. | 0–1 |

| 9/3 | Knowling AC – Goodfellow & Co. | n.a. | 1–1 |

| 10/19 | St. Bon’s Town – St. Bon’s Outports | St. Bon’s | 0–1 |

| 11/2 | St. Bon’s – Bishop Feild | Llewellyn | 6–1 |

| 11/5 | Bishop Feild – City Scratch | Llewellyn | |

| 11/7 | Methodist College – St. Andrew’s Boys Brig. | Methodist 1–0 | |

| 11/19 | St. Bon’s – City Scratch | Shamrock | 0–3 |

| 11/21 | Methodist College – St. Bon’s | Methodist | |

| 11/27 | St. Bon’s – City Scratch | St. Bon’s | 0–1 |

| 11/30 | St. Bon’s – Methodist College | n.a. | |

| 12/5 | C.E. Institute – City Scratch | Llewellyn | 1–3 |

Notes for Appendix 1

Appendix 2: Lineups and PlayersB1

- Terra Nova Rangers (match of 11 August 1883 against Cathedral Works)J. McFarlane, W. Phelan, J. Donnelly, Wylie, Pender, W. Power, MacKinlenny, Mann, Gray, Hanlon, Maher

- Terra Nova Rangers (match of 28 June 1884 against Victoria Rangers)J. Donnelly, J.C. Strang, M. Phelan, J. Mochler, M. Pender, F. Maher, W. Gray, J. Whylie, J. McFarlane, G. McCarthy, J. McHinlay

- Terra Nova Rangers (match of 20 June 1885 against Natives)J. McFarlane, J. Mochler, J. Skaines, M. Pender, W. Gray, G.W. McKinlay, W. Power, J.C. Strang, A Mann, J. Donnelly, F. Marr

- Terra Nova Rangers (match of 27 November 1886 against City Scratch)Strang, White, Raines, Phelan, Pender, Donnelly, J.W. McKinlay, A.W. McKinley, Power, Adams, Maher (McFarlane acted as umpire).

- Cathedral Works (match of 11 August 1883 against Terra Nova Rangers)S. William, J. Andrews, Whyte, Dwyer, Mitchell, Johnston, Doxey, Scott, Rutherford, Parhill, Macqueen

- Cathedral Works (match of 5 September 1883 against Victoria Rangers)Wright, White, Mitchell, Andrews, Dwyer, Johnson, Pepper, Doxey, Rutherford, Scott, Macqueen

- Victoria Rangers (match of 5 September 1883 against Cathedral Works)Whiteway, Sutcliffe, Downs, Jenkins, Trapnell, Antle, Tilley, Hookey, Collins, Martin, Pinn

- Victoria Rangers (match of 28 June 1884 against Terra Nova Rangers)J. Whiteway, R. Martin, W. Downs, T. Jenkins, G.A. Collins, J. Hookey, L. Sutcliffe, J. Trapnell, G. Pynn, W. Hunt, W. Martin

- Victoria Rangers (match of 24 September 1884 against Natives)Whiteway, L. Sutcliffe, N. Chislets, T. Jenkins, W. Martins, E. Tilley, K. Chancey, G. Collins, J. Trapnell, T. Adams, J. Hooky

- Natives (match of 24 September 1884 against Victoria Rangers)M. Percy, D. Sullivan, J. Breen, H. Bartlett, J. Neill, J. Codner, R. Martin, S. Hookey, S. Learning, J. Stitstone, W. Norman

- Natives (match of 20 June 1885 against Terra Nova Rangers)M. Percy, D. Sullivan, S. Learney, H. Bartlett, J. Taylor, S. Hookey, W. Mormedy, D. Ainsworth, J. Stison, R. Martin, J. Codner

- Natives (not the club but the team selected to play the Aliens on 13 June 1894)W. Hayward, H. Hayward, A. Donnelly, H. Donnelly, J. Shea, R. Holden, T. McNeil, H. Jardine, Rev. A. Bayly, P. Knowling, Lieut. Melville

- City Scratch Team (match of 27 November 1886 against Terra Nova Rangers)Harvey, Heygate, Job, Steer, Thorburn, Grieve, Syme, Gear, Gosling, Rennis, Simms

- Church of England Academy (match of 28 November 1891 against Methodist College)G. Williams, W. Smith, R. Wood, Mr. Lloyd, E. Watson, W. Reid, Mr. Blackall, H. Feaver, T. Godden, F. Hutchings, E. Reid (Mr. Blackall and Mr. Lloyd were teachers)