RESEARCH NOTE

John Tilsed (1747–1834):

Servant of George Cartwright and the Slades, Planter of Shoe Cove, Gentleman of Dorset

1 Historians traditionally focus on significant and well-documented trends, events, and individuals, whereas genealogists often find it difficult to uncover more than the dry vital statistics of their enigmatic ancestors. However, the ever-increasing accessibility of both digital and offline source material, previously held privately or in far-flung libraries, can now help flesh out more details of obscure personalities and offer fresh perspectives at the intersection of history, anthropology, geography, and genealogy.1 The impetus for this research note was our discovery that a name found across many of these original sources dovetailed neatly into the timeline of just one man.

2 Merchant ships of the late eighteenth-century Newfoundland trade took men and supplies from England to Newfoundland and Labrador, then returned to markets in England or the Mediterranean laden with fish, seal oil, and furs. Surviving documents linked to well-known merchants provide a treasure trove of information about the men working for them — documents such as the acclaimed journals of George Cartwright, the meticulous Slade ledgers, and the personal diaries of the Lesters. Cartwright, who hailed from Nottinghamshire, had first come to Newfoundland in 1766, then returned with his brother in 1768 in an attempt to establish relations with the reclusive Beothuk people. Two years later he began an almost 16-year residence on the coast of Labrador, keeping a journal that he published in 1792. Brothers Isaac and Benjamin Lester were prosperous merchants from Poole, Dorset, with family links to Trinity where they established their Newfoundland headquarters; their diaries span the period from 1761 to 1802. John Slade and, later, his nephews were competing merchants, also from Poole and extremely prosperous. Slade began his Newfoundland trade in the early 1750s and had fishing and trading operations based in Twillingate, then Fogo, and eventually Battle Harbour. The detailed ledgers produced by Slade’s clerks contain the names of many men recruited from Poole and its hinterland.

3 That these English merchants left a paper trail in the form of journals, financial ledgers, and other documentation explains their prominent place in the scholarly — and even popular — history of Newfoundland and Labrador. What, however, became of those who worked for them? Here, through genealogical research, we trace one such man and get a glimpse into his long-forgotten life on the periphery of history.

4 Workers in the merchant trade were either “servants” or “planters,” terms that conjure very different connotations today than they did in the eighteenth century. Servants were the men and boys who were employed by merchants in Newfoundland and Labrador for a discrete period of time before returning to Britain. The duration of their employment could range anywhere from a month to upward of six years, but was often two summers and one winter, which might be renewed for a subsequent term. By contrast, those who settled in Newfoundland or Labrador were planters. Planters used hired servants to operate fishing boats that worked from shorefront fishing rooms, the larger of which were called premises or plantations. They were considered either dependent (obligated to deal with a supplying merchant firm) or independent, and generally they rose from the ranks of servants. Some such individuals constituted a middle class in the Newfoundland milieu of the period. The Slade ledgers contain numerous examples of servants becoming planters, although among them there are relatively few instances of those who quantifiably thrived.

5 There are even fewer examples in Labrador, where knowledge about most servants vanished into unrecorded time.2 The transition from salaried employee to supplied resident was difficult, and it seems that many who made the attempt to become planters fell deeper into debt and left the region.3 Remarkably, a variety of surviving records show that one man,4 John Tilsed, over a 25-year span, was twice employed in Labrador by Cartwright and in both Labrador and Newfoundland by the Slades, before successfully becoming an independent planter in Shoe Cove on the Baie Verte Peninsula and eventually retiring comfortably to his native Dorset. To have a comprehensive biography of an individual servant active in both Labrador and Newfoundland, shown to have successfully made the transition to planter, together with parallel knowledge of his family, life, and fate back in England, is quite rare.

6 John Tilsed was baptized in 1747 in Wimborne Minster, Dorset. 5 Boys would typically serve an apprenticeship or indenture and possibly John Tilsed, whose father died when he was four years old, was sent to Poole as a parish apprentice when he reached age 11. However, nothing certain is known about Tilsed until his name appears in George Cartwright’s journal entry on 19 May 1771. On that date Cartwright hired him as a “boatsmaster” (one of several servant’s roles6 ) off a sealing ship in Labrador.7 The journal is not entirely clear about which sealing ship Tilsed arrived on, but it seems to refer to one led by Hezekiah Guy8 under the auspices of Cartwright’s early partnership with Jeremiah Coghlan, Thomas Perkins, and Francis Lucas.

7 To be serving on a sealing ship in Labrador and hired into the well-advanced position of boatsmaster by age 24, even in Cartwright’s small and neophytic operations, Tilsed must have gained plenty of prior experience — presumably more so in Poole and Newfoundland than in Labrador. British merchants could not begin to exploit Labrador until it, along with most other French possessions in North America, was ceded from France when the Treaty of Paris came into full effect in 1763. France then retained rights to the “French Shore” along Newfoundland’s coast between Point Riche and Cape Bonavista, while the rest of the island and Labrador were placed under the jurisdiction of the British governor of Newfoundland (Labrador was later transferred to Quebec under the Quebec Act of 1774). In 1765, Governor Hugh Palliser issued fishing regulations that prioritized migrant merchants from Britain’s West Country; the first ships to arrive from Britain in the spring had full rights to the best harbours for the rest of the season, and crewmen had to be British despite their inexperience with local conditions and methods compared to men from Quebec, New England, or Newfoundland.9 John Tilsed may have been recruited to Labrador by Coghlan, who was based at Fogo10 and sealing in Chateau Bay as early as 1765 and who, with Perkins, purchased the schooner Enterprize to use for trade between Poole and Fogo;11 by the Lesters, who were active on the Labrador coast by 1767; by Lucas, who took command of the Enterprize in Poole and arrived in Labrador in July 1770 seeking trade with the Inuit; or by Hezekiah Guy, who is listed as a fisherman in Twillingate (1768) and Fogo (1771).12

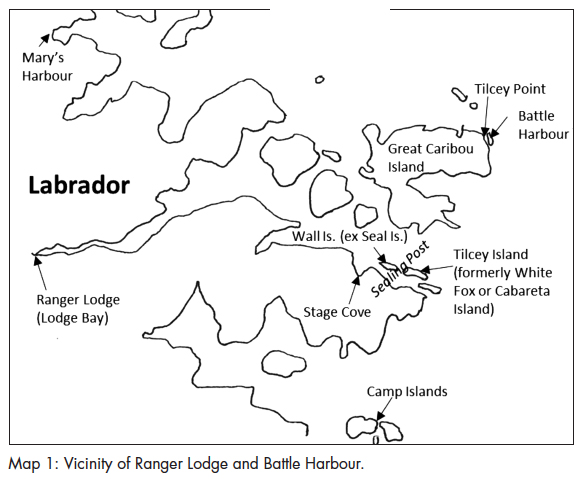

8 Residing with Cartwright at Ranger Lodge (Map 1), in present-day Lodge Bay near Mary’s Harbour, Tilsed helped with the construction of facilities in nearby Stage Cove13 — used seasonally by Cartwright for four years14 in the mid-1770s and as his main residence in 1774–75 — and fetched supplies from Fogo.15 The men made frequent forays along the Labrador coast for hunting, trapping, fishing, and sealing. On Tilsed’s return from one such outing to Seal Island in January 1772, Cartwright recorded that both of Tilsed’s big toes were “frozen solid” and that he “kept his feet in cold water with snow in it for eight hours.”16 Three months later, having frozen them again, “they mortified so far that he lost both nails, and bared the ends of the bones.”17

9 Cartwright interacted and traded with local Indigenous peoples, both the Inuit and, to a lesser extent, the Innu. Recent excavation of two late eighteenth-century Inuit sod houses on Great Caribou Island (near both Battle Harbour and Cartwright’s sealing post — see Map 1) found evidence of European trade such as flintlocks, beads, pearl-ware, and pipe fragments, as well as fur and seal products.18 Although there were violent clashes between Inuit and other Europeans along the Labrador coast, Cartwright and the Inuit developed a close connection. Members of his crew were among the European men known to have relationships with Inuit women and to father their children.19

10 The tickle between Seal Island (now Wall Island) and White Fox Island (now Tilcey Island) provided a highly utilized sealing post for Cartwright and generations of Indigenous people before him. Stretching nets across the tickle when large numbers of adult seals migrated each fall, his six-man crew caught more than 1750 seals in the two years during which John Tilsed is recorded as being there.20

11 The last journal reference to Tilsed in his first term with Cartwright was on 29 June 1772. He likely returned to England that fall, possibly travelling with Cartwright who departed for Britain on 8 November, bringing five Inuit with him. The Inuit caused quite a stir in London, drawing the attention of high society and large crowds but, tragically, four of them died of smallpox before they could return home.21

12 For at least part of the time between 1773 and 1785, Tilsed may have worked for the Lesters in Dorset and Newfoundland. George Cartwright’s journal places John Tilsed at the Trinity home of the Lesters’ partner, “Mr. Stone,” in the early spring of 1785.22 However, it is difficult to ascertain the extent of his involvement with the Lesters because their enterprise was large and individual working men rarely got more than a passing mention in their diaries — John Tilsed is entered using his forename only once.23 There were other Tilseds mentioned in the diaries (most frequently William, Thomas, and “Tilsed ye Pilot”),24 and it is not always possible to distinguish between them in the many instances in which only the Tilsed surname is noted. To further complicate matters, there are also fairly significant gaps in the Benjamin Lester diaries.

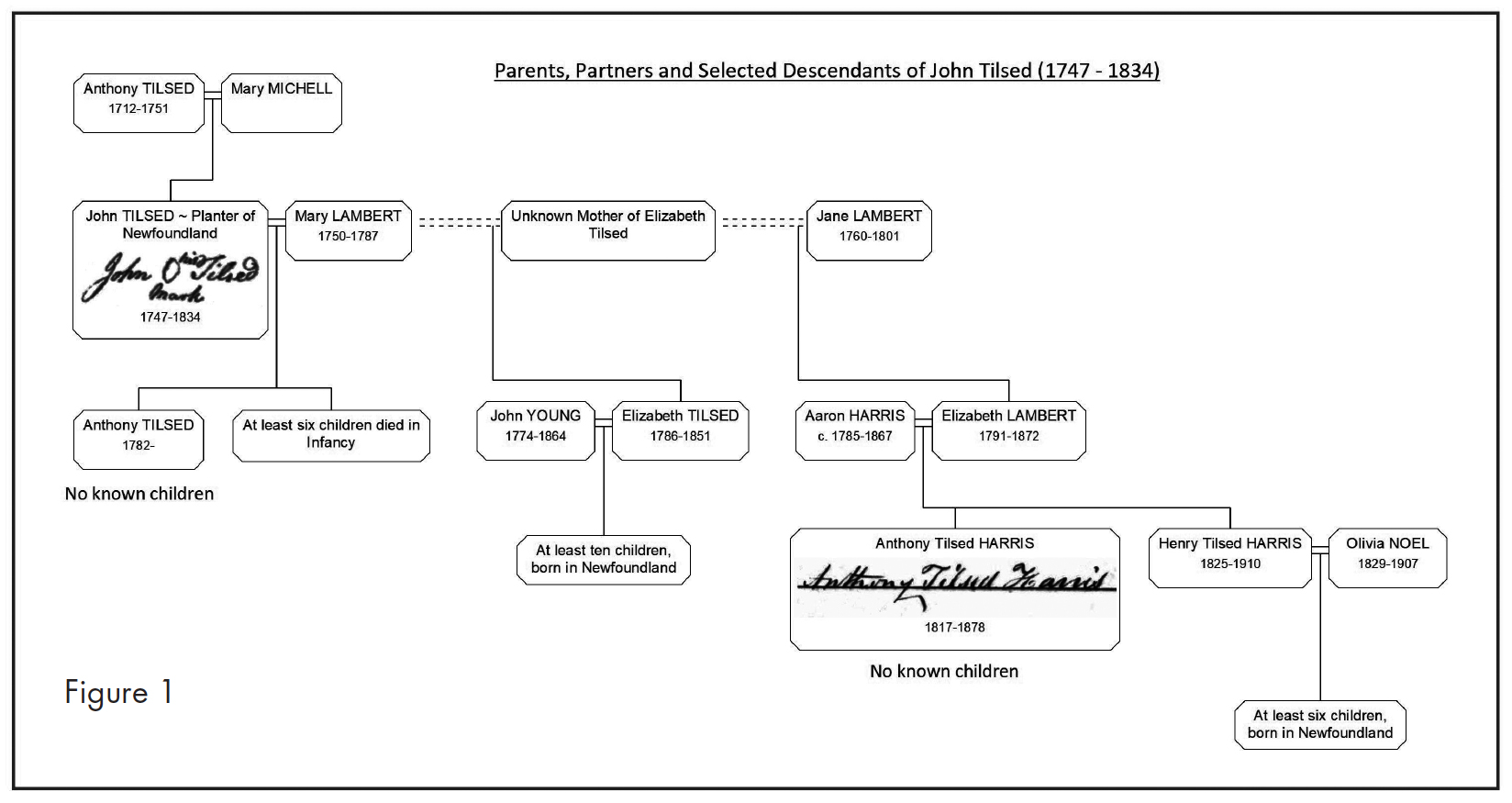

13 During his hiatus from Cartwright, John Tilsed started a family in Dorset (Figure 1). In 1776, he married Mary Lambert of Hampreston.25 They had at least seven children26 but all except one (Anthony) died in infancy. Mary herself died in 1787 and John later had at least one child with her sister, Jane Lambert.27 It was illegal in England until 1907 for a man to marry his deceased wife’s sister so there are no marriage or baptismal records involving both John and Jane, but his will of 1831 coyly makes bequests to their shared Harris grandchildren.

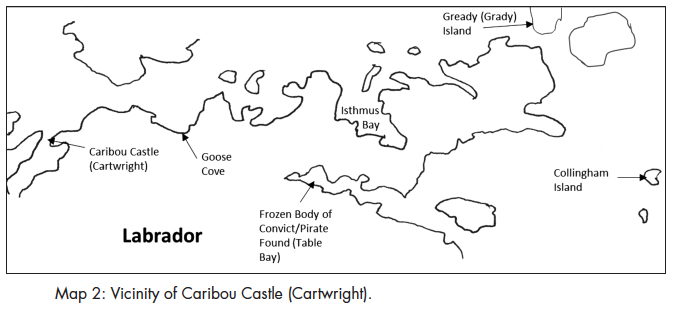

14 John Tilsed rejoined George Cartwright in Labrador in the spring of 1785, again as a boatsmaster,28 but this time based at Caribou Castle (today’s town of Cartwright) and Isthmus Bay (Map 2). By that point Cartwright was faced with bankruptcy, having been the victim of a series of misfortunes including a costly raid by an American privateer. As part of his effort to return to solvency, he resorted to recruiting four young convicts for his operations in Labrador.29 Tilsed was one of a couple of men on whom Cartwright clearly relied and is mentioned almost daily in the journal with accounts of hunting, trapping, fishing, sealing, and often boat repairs or carpentry work on the buildings. The journal paints a picture of Tilsed as a man executing generally mundane but vigorous daily tasks, occasionally punctuated by drama — badly cutting his leg with a hatchet, carrying a lost and frozen former pirate to his burial out on the ice, or getting smoked out of the house by a chimney that had taken him a full week to build. In a rare celebration, Christmas Day in 1785 was marked with a meal of roast venison, mountain hare, venison pastry, berry pie — and their last three bottles of porter.

15 It was not unusual for a man of the Newfoundland trade to remarry if his wife died, to father children in Newfoundland, or even to have a common-law wife in Newfoundland as well as a wife in England. John Tilsed had a daughter, named Elizabeth, who is acknowledged in legal documentation30 and who was likely born in Newfoundland or Labrador, circa 1785 to 1790. The estimate of Elizabeth’s birthdate is based on her age at death in 1851, as inscribed on her headstone marker in Twillingate,31 with an allowance for her reported age being imprecise. The identity of Elizabeth Tilsed’s mother is as yet uncertain. Cartwright makes no mention of John Tilsed having a wife with him in Labrador, nor are there any indications that John’s wife or her sister ever left England or that Elizabeth Tilsed was ever there.

16 George Cartwright returned to England in the fall of 1786 and never went back to Labrador. He began the trip on 30 July, but after a leisurely voyage did not arrive at St. John’s until 2 October. Meanwhile, Cartwright last mentions Tilsed in his journals on 18 August 1786, when Tilsed met him across the straits at Quirpon Island, having arrived there separately in a shallop with the news that one of the convicts had escaped. Two months later, on 19 October, Cartwright departed Newfoundland for England on the brig John. There were 123 other people aboard, including the notorious General Benedict Arnold and 111 discharged fishermen.32 Given that Tilsed’s terms of employment with Cartwright included passage home, he may have been among them.33

17 John Tilsed’s two stints of employment had, in effect, bookended George Cartwright’s 16 years in Labrador — the first commencing a year after Cartwright arrived and the second coinciding with his final two years.

18 After Cartwright’s departure, Tilsed was in need of a new employer. He began as a Slade servant in 1788 and continued to appear in their ledger accounts until 1808.34 By 1788 the Slades had become well established at Twillingate, Fogo, and Battle Harbour, with many branches including Western Head, Change Islands, and Conche. It seems that they made use of Tilsed’s considerable experience in Labrador by assigning him within the same general area — variously the Camp Islands, Conche, and Goose Cove,35 where he was head servant of six in 1789. Tilsed is recorded in the earliest extant Slade ledgers from Battle Harbour (1792) and was there at least until 1795.36

19 Over the 20-year period in which Tilsed had a Slade ledger account, his relationship with the Slades changed from servant to supplier to customer. He was a Slade servant from 1788 to 1795 and for a time also sold them seal oil and fish. During the 1790s his lists of purchases from the Slades were quite lengthy, but by the early 1800s they had become negligible. For whatever reason, he may have eventually turned to a different merchant to acquire supplies. The ledger accounts provide details of financial transactions — wages paid, monies sent home to England, purchased supplies such as rum, tobacco, and sugar needed by otherwise self-reliant residents, and in later years the harvest being sold to the Slades.

20 The ledgers also provide occasional genealogical nuggets. For example, ledger entries reveal that, in 1795, John Tilsed’s 12-year-old son Anthony joined him from England aboard the Slade vessel Love & Unity while daughter Elizabeth stayed in either Twillingate or Fogo37 under the care of Susanna Thoms, a woman who did laundry and odd jobs for some of the Slades’ men.38 Perhaps significantly, John Tilsed signed the 1797 account for Susanna Thoms on her behalf, the final year in which she has an entry. It may be that Elizabeth was a domestic servant to Susanna Thoms, and possibly apprenticed to housewifery, or perhaps they were actually mother and daughter.39

21 The Battle Harbour ledgers for the fall of 1793 make reference to “Tilsed’s Post,”40 where John Tilsed led a crew of six “on the Labrador.” It is reasonable to suppose that Tilsed’s Post is today’s Tilcey Point, located within view of Battle Harbour. The change of name from “Tilsed” to “Tilsey” or “Tilcey” needs explanation; while the preferred spelling of “Tilsed” has remained consistent in Dorset since 1581,41 the pronunciation seems to have misled people, and there are many instances in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries of “Tilsey” as a deviant spelling for Tilsed.42

22 Just as the town of Cartwright and Collingham43 Island and Grady44 Island on the Labrador coast today bear the names of George Cartwright and his men, there are indications that today’s Tilcey Island and Tilcey Point (Map 1) both derive their names from John Tilsed. Tilcey Island borders Cartwright’s primary sealing post and is quite close to both Seal Island and Stage Cove, where he noted Tilsed working. While Cartwright first called it White Fox Island45 and later Cabareta Island,46 as of 1907 it was referred to as Tilsey Island in the memoir by Charles Wendell Townsend.47 Similarly, Tilcey Point, situated on the northern shore of Great Caribou Island near the entrance to Battle Harbour, was known as “Tilsey” Point in a 1950s reference.48

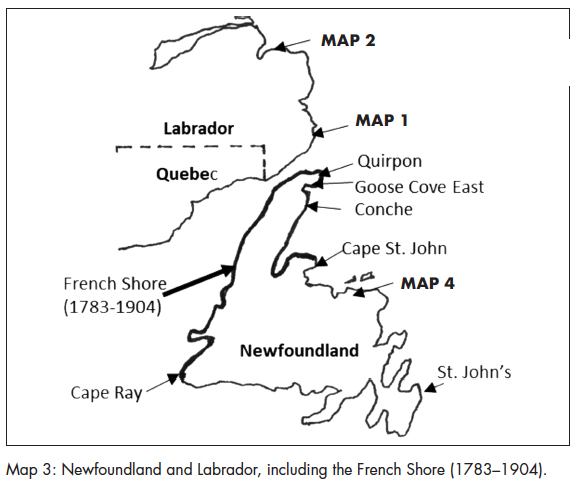

23 At about the time John Tilsed began his association with the Slades, events began taking shape back in Europe that would ultimately affect the nature of their relationship. Although conflict had long existed between France and Britain regarding their territorial possessions in the Americas, the revolution that unfolded in France in the early 1790s came to have a profound effect on Newfoundland trade and settlement by the English. In 1791, as a legacy of the Quebec Act, Labrador became part of Lower Canada along with the southern portion of today’s Quebec, and it stayed that way until being transferred back to Newfoundland in 1809. In Newfoundland, the British were restricted from fishing along the French Shore, which as of 1783 extended from Cape Ray to Cape St. John (Map 3). Starting with the French Revolutionary Wars in 1793, and followed by the Napoleonic Wars, France waged war with Britain almost continuously until 1815. Fear of impressment by the Royal Navy scared many fishermen away from English fishing ports, and the outbreak of a prolonged period of war marked the beginning of the end of the previously thriving migratory fishery between England and Newfoundland.49 Rather than risk frequent transatlantic travel in wartime, many men chose instead to settle in Newfoundland.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

24 John Tilsed was no exception. There is evidence that he, too, started to branch out in the mid-1790s, forming independent partnerships for sealing and fishing. The ledgers record a partnership with Roger McGrath (who had also been with the Slades at Battle Harbour and kept a boat at Tilting Harbour) that was “the second best boat in 1795,” with a haul that included 633 quintals of fish, 376 seals, and 8.5 tons of seal oil. By 1798, Tilsed had partnered with Giles Budgell (also Budgel) and by 1804 with William Sheppard (also Shepard). The surnames of these men who partnered with Tilsed are today common in Newfoundland and Labrador.

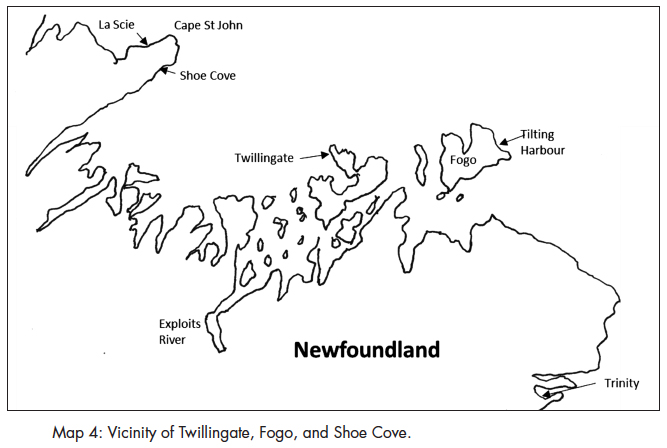

25 In 1804, a mere 11 years after the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars, Governor Sir Erasmus Gower reported that the fishery in Newfoundland was carried out almost exclusively by the residents.50 As of that year, Gower also made note51 that John Tilsed was a planter operating a salmon fishery in partnership with William Shepard in Shoe Cove. Situated on Cape St. John, Shoe Cove (Map 4) is at the edge of what was then the French Shore (Map 3) and adjacent to the French fishing base of La Scie. Tilsed presumably wanted to be close to the waters he knew well and settled as near the French Shore as possible while still being within reasonable proximity of other English residents and supplies at Twillingate and Fogo.

26 English crews out of Twillingate could legitimately fish the waters off Shoe Cove after the 1783 Treaty of Versailles redrew the French Shore boundary with Cape St. John as its eastern limit.52 One of the earliest records of English fishermen in Shoe Cove dates to 1792 when a man was reportedly chased by Beothuk.53 John Tilsed and Giles Budgell may have been living there by 1798, the first year that their partnership bought supplies from the Slades. Budgell was still living in Shoe Cove as of the 1836 census.54 Another among the 14 heads of families named in that census was Robert Thoms, likely the son of Susanna Thoms who had been caring for Elizabeth Tilsed in 1795. By far the oldest grave in Shoe Cove is that of William Shepard, who died at age 70 in 1815.

27 Cross-boundary skirmishes were so common until the mid-nineteenth century that British naval vessels frequented Shoe Cove to prevent French encroachment55 and the French brought a series of caretakers/magistrates to La Scie to deal with theft and vandalism by residents of Shoe Cove.56 When the French gave up their rights on the French Shore, exactly 100 years after Governor Gower noted the operation of the Tilsed/Shepard salmon fishery, many of the English and Irish fishermen living in Shoe Cove moved to La Scie.

28 In about 1804, John Tilsed’s daughter Elizabeth Tilsed married John Young of Twillingate, although no record of their marriage has yet been found. Their eldest child, Eleanor, was born in Twillingate in 1805.57 John Young was the eldest known son of William Young, also a former Slade servant58 turned planter,59 so his marriage to Elizabeth Tilsed circa 1804 was an early example of the Newfoundland union of the offspring of English merchant employees. Oral tradition is that John Young would row a punt across the more than 30 miles of North Atlantic Ocean between Twillingate and Shoe Cove to court, and eventually marry, “Betty Telsie.”60

29 In 1808, John Tilsed signed a Slade receipt for freight from Poole, and there is also a record of a “Tillseed & Budgell” account61 with John and William Fryer, merchants in Wimborne represented locally by Parker Knight & Co. out of St. John’s. The relatively large (£100) latter transaction hints that Tilsed and his partners had indeed shifted business to merchants other than Slade. Surviving records from such merchants are extremely scarce and nothing later than 1808 has so far been found to help ascertain when Tilsed finally left Newfoundland for Dorset.

30 By 1824, Tilsed was living at Pithouse (about 10 miles from Wimborne Minster) with, or near, his English daughter. A legal document62 dated 29 November 1824 references “John Tilsed of Pithouse in the parish of Christchurch Twyneham in the County of Southampton late a Planter in Newfoundland.” In this document, known as a “Mortgage by Demise,” Tilsed lent £150 at 5 per cent interest and gained ownership (but not possession) of a property in Wimborne Minster. The Mortgage by Demise is evidence that the now 77-year-old Tilsed had the financial means to make a fairly significant investment.

31 Although no proof has been found, it is possible that a 71-year-old Susanna Tilsed buried in Wimborne on 24 August 182463 was the former Susanna Thoms, and that she married John Tilsed in Newfoundland prior to the two of them retiring to Dorset (see note 39). No headstone or grave information has so far been discovered to clarify who Susanna Tilsed was. Someone paid 2s 6d for the bell and cloth for her funeral, but not the extra 6s 8d for burial inside the Minster Church.

32 John Tilsed died a decade later, on 30 July 1834 at age 87.64 That is a strikingly advanced age for the era, especially when one reflects on the many risks he must have encountered over his life — freezing his toes and chopping his leg with a hatchet are two incidents we just happen to know of when he was in remote Labrador with no hope of medical assistance beyond homespun remedies.

33 Tilsed was buried in Wimborne Minster on 3 August 1834.65 As with Susanna, whoever arranged the funeral paid the standard fee of 2s 6d to cover the hire of the hearse and pulpit cloths and the ringing of the Great Bell.66 They did not pay the extra 6s 8d for him to be buried within the Minster Church itself.

34 His will of 1831,67 in which he is self-described as “formerly of Shoe Cove near Cape John (sic) in the Island of Newfoundland Planter but now of Wimborne Minster in the County of Dorset Gentleman,” names only family and acquaintances in England. However, among the papers of John Peyton at Memorial University is a document referring to a legal settlement in which John Tilsed, through Robert Slade, an attorney in Poole, provides that his daughter Elizabeth (Tilsed) and her husband, John Young, in Twillingate, receive dividends as they become due on the sum of over £1055.68 This is the only known contemporary document confirming that John Tilsed was Elizabeth’s father.

35 Between the will and the settlement, Tilsed’s estate is conservatively estimated to be over £1255 — certainly a significant sum and a testament to his success as a planter, considering that through all the years as a servant with both Cartwright and Slade, he received wages of only £37 for two summers and a winter (and £20 for a single year with Slade, 1792–93). Tilsed may well have been able to develop and sell fishing and sealing posts, leading to the large value of his estate, although no such record has been found.

36 The Tilsed surname vanished from Newfoundland and Labrador by the middle of the nineteenth century. All traces of son Anthony disappear after the 1795 ledger entries and daughter Elizabeth took the married name of Young. One William Tilsed of unknown relation to John Tilsed — who was active near St. Mary’s beginning in the 1790s69 — had died by 1820.70 A different John Tilsed, also of unknown relation to the subject of this paper, was captain of the infamous Mountaineer found intact but abandoned 16 miles off the coast of Newfoundland in 1850.71 Although the Tilsed surname disappeared, John Young and Elizabeth Tilsed had at least 10 children,72 and today there are numerous descendants in the province and beyond. Also, John’s English grandson and namesake, Henry Tilsed Harris73 (1824– 1910), moved to Newfoundland74 as a young man, possibly inspired by his grandfather’s story. In 1854 he married Olivia Noel at Freshwater, Carbonear.75 Henry and Olivia had at least six children,76 moved to Bay of Islands, and are buried in Corner Brook.77

37 Genealogical research and collaboration,78 benefiting from the growing accessibility of source material, can shine a surprisingly bright light on such interesting but unrecognized characters in Newfoundland and Labrador history as John Tilsed. Just as many Newfoundlanders in recent times ventured afar in search of employment opportunities — sometimes staying, sometimes returning — the men of Dorset came to Newfoundland and Labrador for the same purpose more than 200 years ago. Servants would often put down roots in Newfoundland, but what sets John Tilsed apart — beyond the fact that he is known to have worked for multiple merchants and was able to parlay his early experiences into a successful venture as a planter — is the relative abundance of detail of his life in Labrador, and in Dorset, and in Newfoundland. John Tilsed’s extraordinary saga presents a rare glimpse into the life, adventures, and legacy of an ordinary man successfully forging his livelihood circa 1770–1808 during formative times in the settlement of the frontier colony. His ongoing legacies to his adopted home are the Tilcey place names and his many descendants.

- Susanna’s husband, Jacob Thoms, died in 1787 in Newfoundland, the same year that John Tilsed’s wife died. He was likely the Jacob Thoms baptized in 1748 in Hampreston, so of similar age to John Tilsed and from the same village where John and Mary Tilsed lived.

- Widowers often remarried, or lived in a common-law relationship, of practical necessity to do everything required to raise and support a family in those early outport years. By 1795, John Tilsed had two children in Newfoundland, and Susanna had children from her marriage to Jacob.

- The Slade ledgers record Susanna doing laundry for John Tilsed (1788), maintaining Elizabeth in Fogo while John was away (1795), and having her account signed by him (1797).

- No record of Susanna Thoms is found after 1797 but Robert Thoms, believed to be her son by Jacob, was an early resident of Shoe Cove and is enumerated there in the 1836 census.

- Elizabeth (Tilsed) Young named one of her many children Susannah.

- According to burial registers and churchwardens’ accounts, a Susanna Tilsed who lived in Wimborne was buried there on 17 August 1824 at age 71 (so born circa 1753). She was of suitable age to have possibly been John Tilsed’s wife, and John is known to have been back in the Wimborne area by 1824. No other life events for this Susanna Tilsed have been found, and no relatives confirmed.

- The name of John’s Newfoundland daughter has been transmitted through oral tradition and later written by descendants as Betty Telsie, but the power of attorney giving authority to pay out her inheritance clearly states her father’s name as Tilsed.

- In English records, John himself was christened and married as Tilsed but buried as Tilsey; his wife, Mary, was buried as Tilsed, while the christenings and burials of their children were mainly recorded as Tillseed with one instance of Tilsey and two of Tilsed.

- John’s brother, Roger, was christened, married, and buried as Tilsed. Roger’s first and last known children were christened as Tilsed, but the seven in the middle are noted in the register as Tilsey.

- John’s grandson Anthony Harris used the name Anthony Tilsed Harris at his own marriage and at that of his sister Susan, where he signed as witness, but he appears in the christening register of Ringwood as Anthony Tillsey Harris.

- The St. Mary’s merchant William Tilsed (about whom details are available through subsequent endnotes) had a sister whose confident signature on several documents, including her marriage certificate, clearly reads “Ann Tilsed.” Despite this, the rector recorded her name at marriage as Tilsey.

- The erroneous spelling of Tilsey for Tilsed died out with the rise of mass literacy — in the 1911 census of England and Wales there is only Tilsed who is misspelled as “Tilsey” and he was named for the enumerator by a lodging-house keeper who made his or her mark. By this time, lacking any Tilseds in the area, the name was fixed in Newfoundland oral tradition as “Tilsey.”