Article

Joseph Roberts Smallwood:

A Biographical Sketch, 1900–1934

1 Joseph Roberts Smallwood was, and remains, a man of myth — myth of his own making and myth made by others, both friend and enemy. During his long career in Newfoundland politics — he led the campaign for union with Canada and was then the first premier of the new province, serving from 1 April 1949 to 18 January 1972 — he used his literary, rhetorical, and theatrical skills to create a distinct and celebrated persona. Known, variously, as “Joe,” “Joey,” “J.R. Smallwood,” and “J.R.S./JRS,” he was sometimes referred to in his late years as “the little fellow from Gambo.”1 He told his own story in his 1973 autobiography, I Chose Canada. Dashed off immediately following his long premiership and published by Macmillan Canada, it ran to 600 pages and capitalized on his national prominence and on his fluency as a writer. While he was still alive, he became a stage character in a one-man show performed by actor Kevin Noble. In the title of his widely read 1968 biography of the Newfoundland leader, Richard Gwyn dubbed him “the unlikely revolutionary.”2 The satirist Ray Guy, whose career was largely built on attacking Smallwood, mocked him, to great advantage, as “the only living father of Confederation,” a moniker contracted to the disparaging “O.L.F.”3 In his 1989 biography Joey, Harold Horwood, who had served in Smallwood’s cabinet only to become an unrelenting and scathing journalistic opponent, described him as “the most loved, feared, and hated of Newfoundlanders.”4 In 1998, the writer Wayne Johnson moved Smallwood into the realm of fiction in his highly successful novel The Colony of Unrequited Dreams (eventually adapted for the stage by Robert Chafe). To Ray Argyle, the author of a brief 2012 life in the Quest biographies series published by Dundurn, Smallwood was a “Schemer and Dreamer.”

2 When John Crosbie was lieutenant-governor of Newfoundland and Labrador (2008–13), there was a caricature of Smallwood in public view at Government House, St. John’s. Another, and very different, Smallwood can be found, though, in his voluminous papers deposited at Archives and Special Collections, Memorial University Libraries, St. John’s, and in his extensive early writing, most of it buried in newspapers and magazines. It is this Smallwood that we seek to understand here. There are multiple J.R. Smallwoods, but the aspiring young man presented in this biographical sketch stands apart. Talented, venturesome, and, above all, remarkably resilient, he was no ordinary Joe.

3 Our purpose in writing this paper is to add a documentary basis to knowledge of Smallwood’s early life, both personal and political, and to expand knowledge about a big and diverse career. Much is known about Smallwood’s formation from the work of Richard Gwyn and Harold Horwood, but his own papers and his extensive newspaper writing are largely untapped sources. It is these resources that we draw on here to add to existing understanding of the man and his times. One day Smallwood will be the subject of a major entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, the definitive reference source for Canadian lives. Our hope is that the spadework we have done in this biographical sketch will provide a factual basis for a key part of that entry. But other phases of Smallwood’s life — 1934–39, 1939-46, and 1946–49 are periods that readily come to mind — will need similar fresh research effort if a truly comprehensive account is to be written. We end in 1934 because of the rupture in the political history of Newfoundland brought on by Commission of Government. By definition, our main focus here is on Smallwood’s own understanding of the events of his times and his emergence by the 1930s as a well-known and ambitious public figure, albeit an outrider with a very mixed reputation who faced a decidedly uncertain future. Our paper is a building block for a further and deeper understanding of both the private and public selves of a truly extraordinary Newfoundland public figure.

4 The Smallwood family came to Newfoundland from Prince Edward Island. David Smallwood, a carpenter by trade, arrived in St. John’s from Charlottetown in 1861 and soon after married Julia Cooper in his adopted city.5 They had a large family, and the third of their 11 sons was Charles William, who became a lumber surveyor. In 1900, he and Mary Devanna were married in St. John’s. Charles was nominally a Congregationalist, while Mary (known as Minnie) had been brought up as a Roman Catholic, but their nuptials were conducted by the Rev. H.P. Cowperthwaite, a Methodist.6 Charles and Minnie produced another large family, seven girls and six boys, of whom Joseph Roberts Smallwood was the oldest. He was born on 24 December 1900 in Gambo, Bonavista Bay, where his father was temporarily employed. He was baptized in May 1901 by the Rev. Charles Lench, a rising figure in Newfoundland Methodism, a religion that would figure prominently in Smallwood’s intellectual life and in his extensive career as a book collector. Smallwood’s given names were apparently suggested by his grandfather — “Joseph” in honour of prominent British politician Joseph Chamberlain, and “Roberts” in honour of Field Marshal Lord Roberts, at the time commander of the British forces in the Boer War. His grandfather’s anglophile outlook found many echoes in Smallwood’s own later life.

5 In his political career, Smallwood made much of the fact that he had been born in an outport, as the many small coastal communities spread along the Newfoundland coast and away from the capital of St. John’s are called. In fact, though, Smallwood was taken to St. John’s at an early age and grew up there, amid many family ups and downs. Charles Smallwood had a drinking problem, moved from job to job, and was an unreliable breadwinner. As his first-born later remembered, “brief times of prosperity” were combined “with long periods of stringency, and sometimes hunger.”7 The family first lived in St. John’s over a store at the corner of LeMarchant Road and Lime Street.8 From there, they went to Bond Street and then to Coronation Street, finally settling, around 1907, on Southside Road.9 Their way of life in this enclave — at once part of St. John’s but separated from it — was nicely evoked by Reg Smallwood in his self-published memoir, My Brother Joe: Growing Up with the Honourable Joseph R. (“Joey”) Small-wood (c. 1995). The Smallwood children learned how to make do — picking berries on the Southside Hills, catching trout, chopping wood, and tending to a vegetable garden — the latter activity stimulating in the young Joe a lifelong interest in farming.10 Nearby was the “romantic, thrilling magnet” of the harbour, the coves and wharves of which Joe came to know inside out as he absorbed the talk and lore of old Newfoundland. 11 In the spring of each year, the departure of the sealing fleet for the “front” and its return laden with pelts was an especially stirring time. Joe Smallwood’s memory of the St. John’s of his boyhood was of “a paradise of excitement” and indeed it was.12

6 Smallwood attended Centenary Hall, P.G. Butler’s school, and St. Mary’s Church of England school on the Southside; he was also taught by nuns at Littledale Academy, a Roman Catholic school for girls run by the Sisters of Mercy.13 By age 10, he had been in four schools and was known as a bright and promising boy.14 Recognizing this, his well-off Uncle Fred, who ran a boot and shoe business started by David Smallwood, volunteered to pay for him to become a boarder at Bishop Feild College, a rough-and-tumble but well-respected Church of England school for boys and one of the denominational colleges, favoured by parents with means, that stood at the top of the St. John’s educational hierarchy. Bishop Feild was modelled on an English public school and had a headmaster, playing fields, corporal punishment, and a King and Country ethos; it exemplified muscular Christianity.15 Small of stature and from the lower orders, Joe was undoubtedly bullied there but he also advanced academically, read voraciously (a habit that stayed with him), and, influenced by a chance encounter in a dentist’s office with reformist House of Assembly member George Grimes, embraced socialism.16 He was enrolled in the school’s contingent of the Church Lads’ Brigade (an Anglican youth organization) and joined the Boy Scouts, a movement that was new to Newfoundland; in 1914 he accompanied the First Five Hundred of the Newfoundland Regiment as they marched from their training camp at Quidi Vidi and along Water Street to the SS Florizel, the ship that transported them overseas to the battlefields of the 1914–18 war. At this historic moment, Smallwood carried the officer’s bag of Adolph Ernest Bernard, who won the Military Cross at Gallipoli in faraway Turkey.

7 Already radically minded, reflecting youthful convictions about unfair distribution of wealth, Smallwood clashed with authority at Bishop Feild College. He was involved in a protest over the quality of the food being served and led a resistance to punishment meted out to a number of boarders who had skipped evening service at nearby St. Thomas’ Anglican Church. In 1915, he left school in a huff over a dispute with a housemaster. Having bolted Bishop Feild, he worked as a printer’s devil17 at the Plaindealer, a St. John’s weekly under lay Catholic auspices. After six months there learning the trade, he moved over to the Spectator, founded as a temperance newspaper, where he worked as a typesetter. He next spent two years as a circulation clerk at the Daily News. While in this job, writing under the pen name “Avalond,” he published letters in the St. John’s Evening Advocate, the daily newspaper of the Fishermen’s Protective Union.18 Founded in 1908, the FPU had ventured into party politics under the banner of the Union Party (Grimes was one of its stalwarts). It was led by William Ford Coaker, who had become Smallwood’s first role model in public life. From 1910 the Union published the Fishermen’s Advocate, a well-written and widely read weekly. The Evening Advocate dated from 2 January 1917 and was commonly referred to as the Advocate, a designation that will be used here.19 In a January 1918 article in the paper, Smallwood eulogized Coaker as “a man amongst men . . . the super genius, the man who directed the fishermen’s efforts.”20

8 Later that year Smallwood rounded out his introduction to the newspaper business when he became a reporter for the Evening Telegram. He wrote easily and well and was resourceful in the pursuit of stories. Until he had a debilitating stroke late in life,21 words and phrases came to him like capelin rolling on an endless beach. He interviewed British war correspondent Frederick A. McKenzie when he visited St. John’s22 and scooped other papers by meeting up with Newfoundland Victoria Cross winner Tommy Ricketts at sea, before the ship on which the regimental hero was travelling docked in St. John’s.23 Smallwood was also at the fore in covering a crackdown on moonshiners at Flat Islands and the many takeoffs and landings that put Newfoundland in the limelight at the dawn of transatlantic air travel. He brought his reporting on aviation together in an article first published in Newfoundland Magazine and then reprinted in the 25 and 26 August 1919 issues of the Evening Telegram. He also tried his hand at fiction, contributing a story, “The Power of Attraction,” to the paper on 24 December 1918. This recounted the efforts of two outport men in braving a snowstorm to deliver food to a community that had none. On 27 July 1919, he published an article in which he imagined himself an aide to British Prime Minister David Lloyd George at the recent Paris peace negotiations (the Treaty of Versailles had been signed on 28 June). In the same vein, in “What the Kaiser said,” he conducted an imaginary interview with the deposed German leader.24 In “Assisting the Press,” he surveyed the work that went into reporting the day’s news and explained how a reporter went about getting information from public and private sources.25 In an article in one of the city’s Christmas annuals, he gave a glowing account of the Marconi Wireless Company’s Mount Pearl station, while bemoaning the “continuous pessimism” of Newfoundlanders about “the absence of things unusual in this little country of ours.”26

9 As a writer and reporter, Smallwood emerged as an energetic and inspired publicist for Newfoundland — but for a country reconstructed according to the social and economic reformism of Coaker, the FPU, and a nascent labour movement. In the general election of 1919, which produced a coalition between Liberals led by Richard Squires and Coaker’s Union Party, the Evening Telegram supported Squires. Smallwood, however, helped produce the Industrial Worker, a paper established by the Newfoundland Industrial Workers’ Association (NIWA); it supported three Workingmen’s Party candidates opposed to Squires. Smallwood wrote for this paper, briefly edited it, and pasted its front pages on utility poles and fences around St. John’s.

10 Under Newfoundland law at the time, on becoming a cabinet minister a member of the House of Assembly had to run in a by-election. Following the 1919 vote, the two members elected in St. John’s West, Squires and Henry Brownrigg, were subject to this requirement, a by-election being called in their district for 22 January 1920. To oppose them, the Workingmen’s Party joined forces with the main opposition Liberal-Progressive Party, led by former Prime Minister Sir Michael Cashin. Smallwood was active in the campaign on behalf of labour-backed candidate William Linegar; in a letter to the Evening Herald, which he signed as late editor of the Industrial Worker, he issued a clarion call for workers to have their own representatives in the legislature. The ideal candidate “must be a workingman himself and know what the workingman knows, see everything from the same angle, and have the same needs. Equipped with such a knowledge, he must be an intelligent man with ability to present, in compelling, arresting words, the demands of the workingmen to the Assemblymen who have in their hands the power to give the workingmen the things which they desire and need.”27 Linegar, he asserted, was just as such a candidate, but in the event Squires and Brownrigg were re-elected.

11 Smallwood was also active in this period — family circumstances may have led to this involvement – in support of the cause of the prohibition of the sale of alcoholic drink. On 4 November 1915, a national referendum had been held on this issue and those in favour of prohibition had carried the day. Legislation followed, and prohibition, which Coaker strongly supported, took effect in Newfoundland on 1 January 1917. From the start, the administration of the ban ran into problems, as drinkers sought ways around it. The making of moonshine became a problem, as did a loophole enabling doctors to issue prescriptions (popularly known as scripts) whereby alcohol could be obtained. On 14 March 1920, proponents of better enforcement of prohibition held a public meeting at the Methodist College Hall and elected a Vigilance Committee. Its purpose was to “take cognizance of any violations of the Prohibition Act and assist the Department of Justice in its rigid enforcement.”28 Smallwood was chosen to serve on the committee, which also had as members a number of prominent Protestant clergymen. Five days later, however, another public meeting, held at the Casino Theatre, came out in favour of a partial lifting of prohibition and the introduction of a rationing system that “would enable reputable citizens to obtain periodically . . . limited quantities of alcoholic beverages for their personal consumption.”29 This was the policy eventually adopted by Newfoundland, but Smallwood remained a teetotaller for much of his life.30

12 To hone his public speaking skills, Smallwood took a great interest in debating clubs, and in February 1919 he became a member of the most prominent of such organizations in the city, the Methodist College Literary Institute, commonly referred to as the MCLI. The club traced its origins to 1866 and drew on the rich heritage of Methodist pulpit oratory.31 Eventually, Smallwood became one of its most prominent enthusiasts and a formidable extempore speaker, with a rich vocabulary and a rapier command of verbal thrust and parry. On 18 March 1920, he and the young lawyer Leslie R. Curtis (minister of justice and attorney general of Newfoundland, 1949–66) argued the winning affirmative side in a debate about housing policy in the city of St. John’s.32 In addition to being able to write clean, clear, and concise prose, Smallwood was a born storyteller and raconteur.

13 In June 1920, he parted company with the Evening Telegram and ventured forth into the larger world. His first port of call was Halifax, where he worked for the daily Halifax Herald and contributed copy to both the weekly Citizen and a local labour paper. Having been asked by the editor of the Sunday Leader to write articles on “Newfoundland and things and men in Newfoundland,” he appealed to Prime Minister Squires (Sir Richard from 1921) for research help, telling him that he was “painfully ignorant” of things about which he should write. 33 Squires responded favourably, referred the request to his secretary, William J. Carew, wished Smallwood “abundant success,” and offered this assurance: 34 “In spite of the fact you were associated with my political opponents, our acquaintance of the past few years has from my standpoint developed into a personal friendliness because of my knowledge of your ability in the particular line of work with which you have identified your interests.” In a letter to Evening Telegram staff members, published in the paper 10 August 1920, Smallwood stated that his plan was to go to Winnipeg and from there to Vancouver and Seattle; he would then make his way back across the United States to New York. His purpose, he explained to a friend in St. John’s, was to get enough journalistic experience to be able to bring out “a fairly decent rag in Newfoundland — one which, I mean, will wipe the other Sunday-school journals off the slate. You know, I am really ashamed to get papers from St. John’s, and I always hide them away until I can get a chance to read them unobserved.”35 From Halifax, Smallwood published in the Telegram articles detailing his observations of Canadian life.36 While in the Nova Scotia capital, he also enjoyed hobnobbing with influential figures — another predilection that would persist — including Newfoundland worthy Sir P.T. McGrath and President Roy Wolvin of the British Empire Steel Corporation, operator of the iron ore mines at Bell Island, Conception Bay.37 From Halifax, Smallwood went not westward but to Boston, where he spent a few months working at the Herald Traveler. Continuing on to New York, a powerful magnet for Newfoundlanders seeking opportunity, he next worked at The Call, a paper in the vanguard of American socialism.

14 Arrived back in St. John’s, he published, in the 7 January 1921 issue of the Daily Star, an interview with himself about his New York sojourn. Having travelled there by train, his first impression of the city had been of the vastness of Grand Central Station, where he had been given a rough reception: “Before I had a chance to buy a stick of gum even, I was attacked savagely by a gang of ruffians who seemed to have been waiting for me and I [was] whisked into a closed car and I was just going to yell to a cop with a huge shield on his coat when the driver turns around and asks me where I wanted to go. I was terribly relieved. He was a taxi driver. I gave him an address on West 16th street, about fifteen minutes drive. Four hours and eight minutes later, the shades of night having fallen and the electric lights having blazed on, we made our objective and the drive made me a pauper. Driving is terribly expensive in New York.”38

15 On 12 March 1921 Smallwood launched a weekly, the St. John’s Times, described in the first issue as a “liberal, non-political, literary . . . review magazine” and “a publication of wide, general and special interest.”39 He promised “A clean, paper — free and independent, impartial, and liberal.”40 Unfortunately, a printers’ strike disrupted publication just as the venture got going, whereupon he abandoned it and worked as a reporter for the pro-Squires Daily Star. On 12 March 1921, the Advocate praised Smallwood as a “newspaperman who in the brief course of three or four years” had “made a name for himself which other members of the profession might well envy.”41 When the Daily Star failed that same month, Smallwood became a reporter for the FPU paper, to which he contributed a column, “Findings” / “Day. By. Day,” a potpourri of observations on local and world events.42 The column extolled the virtues of Coaker in his role as minister of marine and fisheries in the Squires government. The FPU leader had reduced the operating budget of his department by $500,000 while maintaining its efficiency and services. “It only goes to show,” Smallwood gushed, “what can be done when the right man is there to do it. Confederation would never be in the thought of this country if we had a Coaker for every department of the public service.”43

16 On his return to Newfoundland, Smallwood also re-entered the prohibition debate with a vengeance. In a 31 May 1921 letter to the Evening Telegram — the first of a number of such missives — he asserted that there was “no prohibition in Newfoundland” and that “thirteen thousand gallons of booze” were being consumed annually as a result of bootlegging and the script system.44 Alcohol had to be attacked as if it was typhus: “We must relentlessly and quite without mercy exterminate it. . . . If we don’t, then booze is going to grow strong again. We must regard booze as a wild beast, stinking of beastiality and brutality, the antithesis of civilization . . . and the enemy of culture. . . . [W]e must stand firmly for its total abolition, extinction, elimination and destruction.” The script system favoured people with money, and those advocating a rationing system had the argument of fairness on their side. In order to counter this and to make Newfoundland “bone-dry,” Smallwood called on prohibitionists to adopt a “working program” to rebuild support for their cause.45 The existing legislation was “faultily constructed” and had been approved during the war for sentimental and patriotic reasons.46 What was needed now to rectify matters was an “intense educational campaign against the use of alcoholic poison,” followed by a plebiscite to secure a fresh majority vote in favour of out-and-out prohibition. Prohibition had to be based on the “good will of the people” and on public belief that the ban on alcohol was “good and desirable.” Another — and winning — cause he publicly espoused in this same period was the enfranchisement of women, a reform that was realized in Newfoundland in 1925.47

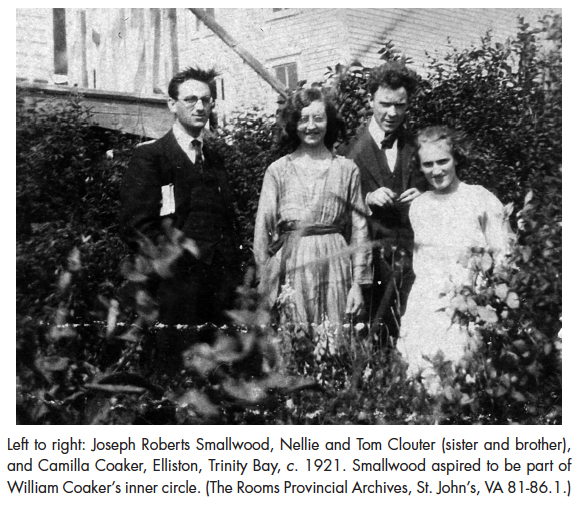

17 In late August 1921, Smallwood made his first visit to Port Union, the town that embodied Coaker’s utopian vision for outport Newfoundland. Writing from Coaker’s office on the fourth floor of the Union Trading Company (an FPU enterprise), he marvelled at being “actually in the sacred spot which of all places in Newfoundland crystalizes unionism and cooperation, and stands as eloquent testimony of the contention that men united can do almost anything, and certainly what men divided cannot do.”48 All of this was personified in Coaker, about whom Smallwood rhapsodized: “I look through the window and there upon the wharf my eye falls upon the man who has by his vision and imagination, his peerless organizing genius, his indomitable courage, and matchless energy made it all possible. I see him busier than any man on the waterfront . . . I see him directing, supervising, helping, giving a hand — where needed — all quite without hesitation, and with an evident zest and keen enjoyment. . . . The man never seems to tire. He must have a stupendous reserve. He is out of bed and on the wharf and in the store at six in the morning, is here all day, and I have seen him here each night so far this week when I left, late in the night, to retire.” In time, Smallwood became part of Coaker’s inner circle, cultivating a close connection with both Camilla Coaker, his hero’s only child, and Tom Clouter, a protégé the FPU leader treated like a son and heir.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

18 In September, Smallwood further extended his knowledge of out-port Newfoundland when he travelled from Placentia along the southwest coast of the island aboard the coastal boat Argyle, recording his impressions in a series of articles for the Advocate.49 By November, he was offering Coaker advice on the future of the FPU. In a letter that perhaps revealed much about his own underlying ambition, he cautioned his mentor: “I think one of the drawbacks on you is the fact that you are tied down to the U.T.C [Union Trading Company], and the other companies. Can’t you get some big man capable of taking care of the companies, and you yourself launch out? History produces a man like you every now and then; history judges that man not so much by his actual achievements as by the extent to which he went in exploiting his opportunities. You are in the rather enviable position of having had thrust into your grasp opportunities for far-reaching good which no Newfoundlander before you possessed or dreamed of possessing. Make no mistake — Newfoundland history will judge you kindly as it is. . . . If you fail Newfoundland, then she is indeed unfortunate and in sad truth the Cinderella of the Empire. There is but one Coaker, and he has but one lifetime.”50

19 In December, Smallwood went back to Port Union for the 13th convention of the FPU, which began on the second of the month. On this occasion, he was called upon by Coaker to speak on the subject of nationalization, which for both of them, in the context of the fishing economy, meant not public ownership of the means of production but greater government regulation in the exporting and marketing of salt codfish. This was a cause that Coaker was pushing at the time within the government and it was a matter about which Smallwood had written extensively in the Advocate. For Smallwood, nationalization meant taking a “national” perspective in solving the problems of the fishery — as opposed to the individualist outlook that typified the dog-eatdog Water Street business community in St. John’s.

20 Smallwood described the convention in two articles, published in the Advocate.51 “Before my eyes, about me,” he eulogized, was a “parliament — a parliament of fishermen. Here were delegates from all the bays of the North and from the South. Here were representatives delegated by many local councils to travel to the union capital; and here, at the fishermen’s parliament, they are to express and give voice to the sentiments of the majority of their constituents. . . . Here, in short, was a national council representing fishermen, fishermen’s interests, and all that fishermen stand for.” The delegates were “old men and middle-aged and young, representative of all shades of thought — seriously discussing and debating big subjects of grave and vital importance to our country. Where else is this done? This convention represents the most conscious, intelligent and enlightened citizenship that will be found in Newfoundland.” Coaker had more faith in the country “than any other Newfoundlander” and since 1908 had been a beacon of “faith and optimism, coupled with intelligence, [and] honest action.”

21 In January 1922, always the adventurous reporter, Smallwood participated in travel of a different sort when he, along with Albert Perlin of the Evening Telegram (a close friend from his Bishop Feild days) and a reporter for the Daily News, flew over St. John’s with Major Sidney Cotton in his Martinsyde biplane. An Australian by birth, Cotton was in Newfoundland to assist in the seal hunt through aerial spotting of the animals.52 “Advocate Man flies over St. John’s,” the FPU newspaper headlined, following up with “Flying above St. John’s! Two thousand feet above the City! Crashing thru the ether at a speed of ninety or a hundred miles an hour! What does it feel like?” Small-wood’s answer, given in an exhilarating account, caught the magic of first flight: “there is nothing I know of that is like it. That beautiful sensation of elevation, of elation, of moving suspension, is something which frankly, has to be experienced to be understood. There is no explaining it.”53 Throughout his life, Smallwood thus embraced technological advance as an instrument for human progress.

22 On 2 June 1922, he departed St. John’s to again seek opportunity in New York.54 There he met with Newfoundland expatriate Fraser Bond, nephew of former Newfoundland Prime Minister Sir Robert Bond. Fraser Bond was executive assistant to Charles Miller, editor-in-chief of the New York Times, who had himself visited Newfoundland in August 1921 and been interviewed by Smallwood for the Advocate.55 Through this connection, Smallwood was promised a job with the paper, but while waiting for this to materialize he was reduced to sleeping first on a park bench near the New York Public Library and then in a series of flophouses. 56 In the end, he never did work for the New York Times57 because another opportunity now came along that appealed to his instincts as a promoter — another lifelong role. At the suggestion of cinema owner Ron Young, a St. John’s friend, he went to see Canadian-born filmmaker Ernest Shipman to follow up on a suggestion that Shipman had made in a letter to Young — news of this was reported in the Advocate — for a movie to promote tourism to Newfoundland. Shipman had been in St. John’s more than a quarter century before as a member of a touring Shakespearean theatrical company and had never forgotten his visit: “The impression made on my mind of the great hills surrounding your harbor, and of the harbor itself will never be effaced.”58 Shipman explained to Smallwood that $100,000 would be needed to make the movie and that 60 per cent of this would have to come from local investors. Smallwood bought into the scheme hook, line, and sinker, and told readers of the Advocate that the film would “embrace all phases of Newfoundland life . . . make the island famous throughout the world and result, possibly, in an influx of tourists and visitors.”59

23 On 20 July, he and the Shipmans, husband and wife, arrived in St. John’s to find the wherewithal for the venture. Newfoundland Films, Ltd. was soon formed and had on its board of directors some of the most prominent businessmen in the city.60 Shipman’s scriptwriter, Garrett Elsden Fort, who had worked on a film adaption of Ralph Connor’s novel Glengarry School Days, arrived in the Newfoundland capital on 31 July to commence work.61 His script was to be based on the novel Rip Tide by Kenneth O’Hara, and much of the shooting was to be done in and around the harbour of St. John’s and at nearby Petty Harbour. In August, Fort went to Halifax to meet with Shipman and O’Hara, and in the same month Shipman and Smallwood went to Prince Edward Island to launch a similar venture there (Smallwood seized the opportunity to visit relatives in the island province).62 In September, Shipman returned to St. John’s and O’Hara came with him. A meeting with the directors of the company followed. With O’Hara “stressing the necessity of fair weather and sunshine for the project,” the directors of the company agreed to postpone shooting until the following July, by which time the whole scheme had fizzled out.63 Smallwood’s reach had exceeded his grasp, an outcome that became a leitmotif of much of his later life.64

24 With the movie escapade behind him, Smallwood worked as a casual labourer in New York until he found a job as assistant editor of a group of trade magazines.65 In this phase of life, he also joined the Socialist Party of America, attended lectures at the Rand School of Social Science, the New School of Social Research, the Cooper-Union Institute, and the Labor Temple (a Presbyterian gathering place run by Rev. Edmund B. Chaffee), and wrote syndicated articles, some of which appeared in the Advocate.66 In the 22 October 1922 issue of The Call Magazine he published “Why I am an Imperialist.”67 “I am an imperialist,” he explained, “because I am a Socialist. I believe in industrialist expansion throughout the earth because I am eager to see the Co-operative Commonwealth ushered in.” Though he had previously written “many columns of anti-imperialist denunciation,” he now understood that by spreading capitalism throughout the world, imperialism would “quicken the coming of the Socialist commonwealth.”

25 From afar, Smallwood also continued to spread the gospel of Coaker and the FPU. He wrote anonymously in the Advocate and produced a panegyric pamphlet — A Sincere Appreciation of Newfoundland’s Greatest Son[:] The Most Brilliant, Original and Romantic Figure Produced by Newfoundland is William Ford Coaker — which was printed by the Advocate Publishing Company, another of the FPU business enterprises. The pamphlet was signed by “An Admirer.” He praised Coaker as orator (“I have to confess that on every occasion when I heard him the tears welled in my eyes and little shivers went down my back”), writer (“He writes like he talks. Not a superfluous word is used. . . . He is as clear as day. What he means he says, and what he says he means. His words cut and sear like branding irons. . . . Never does this man write except on behalf of the fishermen toilers of his native land”), and statesman (“Public life, politics, to him are not games”). Coaker was in “public life only to serve, — to serve the thousands of fishermen who sent him there to be their champion.” In an article published in a January 1923 issue of The Nation, a widely read American weekly, Smallwood explained that Coaker was “not a Socialist — indeed he would hardly know what one was.” Rather, he was “solely a product of Newfoundland and Newfoundland conditions.” He was a man of “practical nature” and “a sincere idealist.” To further the FPU cause, Smallwood contributed a regular column to the Advocate, written in batches “to ensure continuity of publication.”68 Entitled “From the Masthead,” the column was written without remuneration, using the byline “by The Lookout,” a self-description that, adapted to “The Barrelman,” he employed to great advantage in a radio program he would start in 1937. In the Coaker tradition, he imagined himself a vanguard figure, finding a way forward for Newfoundland. In January and February 1923, the Advocate published a series of articles in which Smallwood described “What Newfoundland Might be Fifty Years Hence! A Glimpse at Things in General as They Might be in the Future in this Country.”69 Two of the articles dealt with Port Union and the FPU.70 He foresaw the Port Union of 1973 as an outport arcadia, a “live, wide-awake progressive town.” Always the dreamer, Smallwood imagined a golden future for Newfoundland — perhaps with himself at the fore.71

26 During his second New York sojourn he was also an avid suitor. His friends in the city included fellow Newfoundlanders Billie Newhook and Cynthia Morgan, a courting couple. When they eventually fell out, Cynthia moved to Melrose, Massachusetts, where she worked at the New England sanitarium and hospital. Smallwood, who lived in the same boarding house as Billie, kept in touch with her, and one of her letters to him asked if he still worshipped “at the shrine of the Goddess, Dorothy?” Her advice to him in this regard was: “‘keep on hoping’ Joe, — you may get her yet.”72 Dorothy remains a mystery figure in Smallwood’s biography, but in April 1923 he struck up a close relationship with Sophie Adams, a Jewish New Yorker. She told him that she wanted to be someone “to whom you will pour out all your thoughts, ideas and hopes. In whom you will confide.”73 Their connection, however, proved short-lived, because of opposition from her mother and because Sophie felt that Smallwood’s feelings were not strong enough for it to continue. By this time, moreover, he had developed a romantic interest in eighteen-year-old Lillian Zahn, a student at New York University, who was also Jewish. He had met her in early May 1923 at a social gathering at the residence of the radical economist Scott Nearing, who taught at the Rand School. On this occasion, Smallwood took a photograph of Lillian and enclosed it in a letter he sent to her. The picture was of the “group scattered about the grass eating lunch” but unfortunately showed only the back of Lillian’s head. She expressed surprise that Smallwood had taken so much interest in her but was welcoming: “Since you are not a New Yorker, you must be an interesting personality to meet. You see, I am so tired of New Yorkers that it is a relief to meet an outsider.” Apologizing for not having replied to an earlier letter because she was in the midst of doing some college work, she offered to meet with him on Saturday, 2 June, at 7 p.m., in front of the Rand School. This would be an “opportunity to learn each other’s ideas.”74 Their relationship blossomed during the summer of 1923, with Lillian apparently attempting to teach Joe Yiddish. But when Smallwood did not pass muster with her parents, refugees from Eastern Europe, the relationship came to an end.75 Clearly, however, the 22-year-old Smallwood was ripe for romance, which was not long in coming, through yet another chance encounter.

27 In November 1923, still close to Lillian Zahn, Smallwood returned to Newfoundland to attend the annual convention of the FPU that marked the fifteenth anniversary of the founding of the organization. Much had happened politically in his homeland while he had been away, all of which he had followed closely. In a general election held on 3 May 1923, the Squires government, running under the banner of Liberal-Reform, won 23 seats to 13 for the Liberal–Labour–Progressive Party led by John R. Bennett and Peter Cashin. Coaker had left the government before the election — replaced as minister of marine and fisheries by FPU stalwart William Halfyard — but was elected to the new House of Assembly. He was, therefore, still active in politics when, in July 1923, a cabinet revolt, brought on by alleged misuse of public funds for electioneering purposes, forced Squires’s resignation as prime minister. Squires was succeeded in office by William Warren, with Halfyard serving as colonial secretary and George Grimes as minister of marine and fisheries. The 1923 FPU convention, therefore, was held in very changed government circumstances — and with Coaker in retreat politically.

28 According to the Advocate, Smallwood, who was an honorary member of the FPU, had been commissioned by a “prominent New York labor newspaper” to cover the gathering “of the toilers of the sea” and to write “a number of special magazine articles about the union and other Newfoundland topics.”76 He brought greetings to the convention from Eugene Debs, leader of the Socialist Party of America; and from Frank Hodges, secretary of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain, whom he had met in the United States. Coaker, he told Lillian, had introduced him as a friend of the union: “I got a good hand as I went to the platform, and rarely have ever — never, in fact — felt in better condition to make a speech. My voice was in good form, and I had perfect control, except that I was slightly emotional, which gave my voice a thrill that enhances its value. I read out Debs’ address and it got a great hand. The address from Frank Hodges also got warm applause.”77 In an account of the convention published in the Advocate, he heaped praise on the entire proceedings.78 Privately, though, as soon became apparent, Smallwood had come to have grave doubts about the future of an organization he had long admired.

29 During his stay in Port Union, he took a series of photographs of the town and had “many fine chats” with Coaker. Writing on 4 December from 240 Duckworth Street, the St. John’s office of the Advocate, he told Lillian that he intended “to write a history of the union, in about four hundred thousand words” and “get it published, if possible, in New York.”79 “I have been meeting all my old friends,” he reported, “meeting them at every step I take on the street. I have been out to tea time and again, and have many invitations.” He was also kept busy helping out with a Christmas issue of the Advocate, to which he contributed both an article and some fiction he had had written earlier. Not surprisingly, he met readers in St. John’s who recognized him through his prose style as the writer of the Advocate’s “Masthead” column. Smallwood left again for New York on 15 December.80

30 He next found work at the New York Leader (the successor to the bankrupt Call). One contemporary remembered him as being “rather quiet and retiring”: “when art and literature were being discussed he hardly spoke at all. But when he got warmed up and started off about Newfoundland and Coaker, he could be quite aggressive.”81 As always, he busied himself with literary and political activities, attending lectures and continuing his work on behalf of the Socialist Party, for which he was a speaker during 1924 on behalf of presidential candidate Senator Robert M. LaFollette of Wisconsin.82 He also began collecting material in city libraries for an anthology (never completed) on the great political liberators in history. Most strikingly for this narrative, in a remarkable series of letters to St. John’s labour leader George Tucker, vice-president of the Newfoundland Industrial Workers’ Association and an official of the Electricians’ Union, he gave a searching critique of the diminished role of the FPU in the wake of Coaker’s exit from government and spelled out ideas and plans for the formation of a Newfoundland labour party.

31 The main work of the FPU, Smallwood told “Comrade Tucker,” had now been completed; the union was not “making new progress” and was “resting on its oars.”83 Coaker was no longer young and it was doubtful whether he was “equal to the task of reorganizing and revitalizing the FPU,” much as he might understand that this needed to be done. The underlying problem of the organization was that, while Coaker had definite objectives, there was no “general philosophy or attitude behind them”; “his cut and dried proposals . . . were purely topical and temporary.” That, Smallwood explained, was why “you never see the FPU these days agitating for a specific program, with the exception of fish. Instead, it recounts to the point of extreme weariness, its past achievements.” The FPU now had no “passionate ideals, little fight, less enthusiasm, no policies, and therefore . . . no mission” and was failing in democratic leadership. Its decline, moreover, was “due largely to . . . psychological and other changes” in Coaker himself. He had “burned himself out,” “run out of policies,” and was “largely disillusioned.” He was “tied down” by the FPU’s business side; “Frankenstein like,” it had come to demand all his time. The FPU had “ceased to be a movement, and [had] degenerated into a party.” As a result, the fishermen were “really leaderless.”84 Hence the need for the new labour party Smallwood envisaged. “Every month spent out of Newfoundland,” he told Tucker, “is punishment for me. My whole heart is in Newfoundland, and my interests are centered there. I regard my time spent out of Newfoundland in the light of training and experience, a period of broadening and the absorption of a cosmopolitan spirit if possible. . . . My idea is and has been for years that of equipping myself to be useful to the labor movement that I know should someday come to Newfoundland . . . and [to] devote myself entirely to it for the rest of my life.”85

32 While Smallwood thus mused in New York, party politics in Newfoundland entered a turbulent new phase. In December 1923, the Warren government launched an inquiry, undertaken by Thomas Hollis Walker, the recorder of Derby, England, into the various charges of corruption against the Squires government. His report, delivered in March 1924, led to the arrest of Squires and three associates, all of whom were charged with larceny. While on bail, Squires voted in a House of Assembly non-confidence motion that led to the defeat, by a majority of one, of the government that had charged him. Early in May 1924, having secured dissolution, Warren joined with opposition members to form a new administration but this combination proved short-lived: on 10 May 1924 he was succeeded as prime minister by Albert E. Hickman, another businessman. But when a general election was held on 2 June, Hickman was bested by Walter Monroe, a St. John’s factory owner, who led a deeply conservative party that styled itself as Liberal-Conservative. In August, the Monroe government pushed through the Alcoholic Liquors Act, which gave the quietus to the prohibition debate by introducing a permit system for the sale of liquor. This change was made following Hollis Walker’s finding that the existing system of liquor administration was in reality a bootlegging operation. Luckily for Squires, the charges against him did not survive grand jury scrutiny. He had had a very close call but lived to fight another day — by which time Smallwood had joined his camp. However, the events leading to his downfall and the legal imbroglio that followed not only permanently scarred his reputation but raised doubts about the ability of Newfoundland to govern itself — doubts that metastasized during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

33 The political upheaval that had occurred in St. John’s, George Grimes told Smallwood, had “unmasked a number of men, showing them to be men of straw, devoid of principle, with the jungle spirit of everyone for himself and the devil take the hindmost.” There had been “betrayal after betrayal, with men on the auction mart up to the highest bidder.”86 Disillusioned with politics, Coaker did not run in the 1924 election, preferring, as Smallwood had forecast, to concentrate his energies on the FPU’s business enterprises; as part of this shift, publication of the Evening Advocate was discontinued. Coaker had quit the “whole dirty business” of politics because the Union Party had lost the support of fishermen, and its elected members had degenerated “into an office-loving clique of politicians,” little better, if at all, than the reactionary forces the FPU had set out to replace.87 At the FPU’s December 1924 annual convention, Coaker called on the organization to elect a new president and to “adopt a new platform in touch with the present day requirements.”88 For the moment, he was persuaded to stay on as leader, but the revival he advocated did not materialize. As Smallwood had correctly discerned, the FPU’s glory days were now behind it.

34 It was against this political backdrop that Smallwood returned to Newfoundland in January 1925, having been engaged by American labour leader John P. Burke to reorganize the troubled Local 63 of the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers at Grand Falls, where a pulp and paper mill, owned by the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company, had been in operation since 1909. The local had declined drastically in membership following an abortive 1921 strike,89 and whereas membership had once stood at 1,700, it had now fallen to about 100. To get the organization back on its feet, Smallwood was paid a wage of $46 per week. His return to St. John’s was duly noted in the press, and three days after landing he participated in an MCLI debate;90 on 3, 4, and 27 February he published articles in the Daily Globe — a new Liberal paper launched in December 1924 following the demise of the Evening Advocate — about his “‘Adventures’ in America.”91 It was a “mournful fact to contemplate,” he wrote, that there were more Newfoundlanders living outside Newfoundland than in Newfoundland.92 Moving on to Grand Falls, he got to work on his union assignment and in April, with the support of local unions, launched a short-lived Newfoundland Federation of Labour, which attracted support from a variety of unions in St. John’s and from the Wabana Mine Workers Union on Bell Island.93 With Squires and Coaker on the sidelines and Monroe in office, Smallwood saw an opening for the labour party he had in mind.

35 The platform of the new federation, issued by Smallwood, promised action in favour of unemployment insurance, public health care, an end to child labour, insurance for fishermen, and collective bargaining.94 The federation would hire organizers to promote the union cause throughout the country, publish a weekly labour newspaper, maintain an industrial information bureau to keep record of wage trends in various crafts and occupations, and collect, classify, and disseminate information on labour laws, labour conditions, and housing needs. Smallwood looked to Christian clergymen to support organized labour, trumpeting the news that, after “some delightful chats,” Father William Finn, the Roman Catholic priest in Grand Falls, had wished him “God-speed.”95 On 2 May, Smallwood announced that the new federation had received an invitation from the British National Committee of the Trades Union Congress and the British Labour Party to send representatives to the Commonwealth Labour Conference to be held in London on 27 July.96 Identifying strongly with the Labour Party and drawing inspiration from its rise (Labour leader Ramsay Mac-Donald had become prime minister of the United Kingdom in 1924), he foresaw in its success the end of capitalism by peaceful, constitutional means. When Thomas J. Foran, the proprietor and editor of The Searchlight, questioned his credentials to act as a champion for labour and accused him of being a subversive ideologue,97 Smallwood replied vigorously:

36 In this case, however, rhetoric belied organizational reality. The first national convention of Smallwood’s nascent labour collective was planned for December but nothing came of this and, like many other initiatives at this stage of Smallwood’s life, the project of the federation proved overly ambitious and eventually came to naught. Meanwhile, though, he bombarded the press with correspondence on a wide range of labour-related issues, taking a special interest in the wages and working conditions of miners on Bell Island.99

37 In June 1925, Smallwood moved on to Corner Brook, where Newfoundland Power and Paper Co. had just started up a pulp and paper mill, for which Squires claimed full political credit; the disgraced former prime minister was said to have put “the ‘hum’ in the Humber,” the river that enters the Bay of Islands near the site of the new enterprise.100 Paper workers, electricians, and machinists in the now booming town had already organized trades locals and Smallwood, sometimes holding secret meetings in the mill during working hours, was able to help consolidate them into Local 64 of the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers.101 While thus employed, he stayed at a boarding house run by Mrs. Serena Baggs in nearby Curling, an old settlement. His choice of accommodation proved fateful, for there he met the visiting Clara Isabel Oates of Canvas Town, Carbonear, a cousin of the landlady. Born on 23 October 1901, she was the daughter of Edward and Sarah Oates (née Ash). The Oates family was well established in a town that had a strong entrepreneurial and maritime tradition. Her great-grandfather Thomas Oates, captain of the Belle, was well remembered as one of the “Vikings of Carbonear” who had “sailed the northern seas” decades before.102 Joe and Clara were of marriageable age and a romance quickly blossomed between them. By the time she returned home they were engaged, but their wedding had to await Smallwood’s next organizing venture.

38 In September, starting out from Port aux Basques, he made his way along the main line of the Newfoundland Railway (publicly owned since 1923), signing up section men as he went. He proceeded on foot, by hand trolley, and by train, stopping briefly at Corner Brook to attend to labour federation business and then moving on.103 At Clarenville, he took the branch line to Bonavista and visited Coaker at Port Union. Continuing on, he eventually took the branch line to Heart’s Content and from there proceeded by horse and cart to Carbonear, where he and Clara finalized wedding plans. He then resumed his rail journey until he reached Avondale, where he met with a party of railway officials that included general manager Herbert Russell, an old MCLI friend. Threatening to close the railway down, Smallwood was able to convince his interlocutors not to implement a proposed wage cut for the section men he was now representing.

39 On Thursday, 19 November 1925, a linen shower was held at the Oates home in Carbonear in honour of Clara.104 Then, on the evening of Monday, 23 November 1925, she and Joe were married at her family residence with the Rev. W.R. Budgen of the United Church officiating.105 There were no attendants and the wedding was “a quiet one” with “only the immediate relatives and friends of the family being present.” The “very prettily attired” bride was given away by her father and was the recipient of “a large number of presents,” said to be indicative of the esteem in which she was held.106 The next day the newlyweds left by train for St. John’s, where they stayed to begin with at the Balsam Hotel on Barnes Road.107 On 1 March, writing from rented rooms, Clara told her sister Beulah that she and Joe kept late hours and that he made her “go everywhere with him.”108

40 During their first year of marriage, the restless Smallwood busied himself in many directions. He published a weekly newspaper, The New Outlook, for the members of the railway union and remained active in the cause of the Newfoundland Federation of Labour. The motto of The New Outlook was “Fearless and Free.” On the front page of the first issue (dated 21 November), in keeping with this sentiment, Smallwood lashed out at the Evening Telegram for implying of late that there was Bolshevism in Newfoundland and that he was a Red. He challenged the Telegram “to make a statement in plain English” that he was a Communist, and spelled out what that paper could expect from him in response to its innuendos:

Whereas the Telegram had once had “personality,” and “principles,” and been “fearless,” it now preferred “to fawn and toady, most particularly to those who might give it advertising patronage.” In short, it put “business first and opinions, if any, last.”109

41 In January 1926, Smallwood began working for the Daily Globe, which was published from the building that had formerly housed the Advocate and was now edited by FPU veteran and House of Assembly member Richard Hibbs. At this paper Joe resurrected his column “From the Masthead,” “By The Lookout,” a literary outlet that allowed him to range widely. “Like the cat that came back,” he wrote in his first contribution, “I am again doing business at the old stand. I began this column in the old Evening Advocate, and continued it in The Labour Outlook. From now on I shall give the readers of The Daily Globe the benefit of my great wisdom and mighty pen. The only thing wrong with that sentence is that I don’t write with a pen, but a typewriter.”110 In April and May 1926 the Smallwoods paid rent to E.J. Berrigan, who ran a business at 209 and 211 Gower Street selling “Dry Goods, Millinery and American Novelties.”111 But they subsequently moved in with the Hibbs family, an arrangement perhaps tied to a partnership between Smallwood and Hibbs to publish a Newfoundland Who’s Who.

42 In this period also, Smallwood went through an intellectual metamorphosis by which he reconciled his socialist ideals with the practical realities of Newfoundland public life, emerging as a Liberal in politics and a supporter of Squires, who eventually became his patron. On 7 January 1926, he gave the first of a series of talks organized for city labourers by Dr. James Tait.112 His topic was the Newfoundland labour movement, and, in keeping with his recent history as a labour activist, he asserted that Newfoundland workers required their own labour party in the manner of their counterparts in Great Britain. The Liberal Party had once been the party of labour in Newfoundland but it no longer fulfilled this role and was now indistinguishable from the Tory Party.113 One of those present on this occasion was George W.B. Ayre, a controversial lawyer well known to Smallwood. Convicted in October 1922 for breach of trust and sentenced to two years with hard labour,114 Ayre had had his sentence commuted and was later allowed to resume professional practice; in the program of a complimentary dinner given in his honour at Smithville on 10 September 1925 he had been described as the “Solicitor for the Unemployed.” 115 In correspondence with the Daily Globe, the unorthodox Ayre praised Smallwood’s knowledge and ability but insisted that it was the Liberal Party that could still best serve the workingman’s purpose. In effect, he challenged Smallwood to reflect on how Newfoundland liberalism could be updated and renewed. Smallwood’s conciliatory response was that if the Liberal Party would “pull itself together, take earnest stock of the situation, and formulate and commit itself to principles and policies of social reform nature; and genuinely advocate them, there need never be a Labor Party in Newfoundland.”116 The exchange triggered a series of lengthy articles by Smallwood in the Daily Globe, in which he explained in detail how a revived Liberal Party could transform itself and continue its historic role on the side of the masses.117 Not surprisingly, these drew extensively on the plans he had spelled out in his letters to George Tucker calling for the creation of a Newfoundland labour party. Socialism would be the end but liberalism would be the means. On 8 December 1925 Smallwood and a teammate argued the winning negative side in a debate, sponsored by the Wesley Debating Club, on the proposition “That Newfoundland would be more prosperous under Crown government than under Responsible government”; their opponents were lawyer Raymond Gushue (later president of Memorial University) and Hayward Williams.118

43 Over the next months, Smallwood’s immediate concerns were decidedly personal. On 15 July 1926, he and Clara had their first child, a son, born in St. John’s and named Ramsay MacDonald Coaker in honour of two of his father’s heroes in life.119 But trouble struck around the same time when the financially strapped Hibbs was forced to stop publishing the Daily Globe (the last known issue was dated 5 June 1926).120 Smallwood’s response to this setback was to set forth for the United Kingdom in search of opportunity there; while he was away Clara and the baby would live with her family in Carbonear, until Joe came up with the money to bring them overseas. It was not uncommon for Newfoundland men to spend long periods away from home working, and Smallwood’s action should perhaps be understood in this context rather than by present-day expectations about family life. Absence, however, strained relations between husband and wife, and their correspondence was painful. To finance his fresh start, Small-wood sold a collection of books to Hibbs (at some stage he had also given up his partnership stake in the projected Who’s Who, which Hibbs eventually published in 1927).121 Before going abroad, Small-wood dickered with Coaker about writing a full-scale biography of the FPU founder, but when he set sail for Liverpool aboard the Furness Withy liner SS Newfoundland on 27 November (he travelled in steerage to the “Old Country”), this project remained up in the air.122 Two days before leaving, he had represented Royal Oak Orange Lodge in a debate with Leeming Lodge on the topic “Has trade unionism’s injuries to members been greater than its benefits.”123 Not surprisingly, he and his teammate, Royal Newfoundland Regiment veteran Charles F. Garland, had made the case for the benefits side.

44 Basing himself in London, he reported back to St. John’s on his activities in three letters, dated 9, 12, and 30 January 1927 and published in the Daily News under the heading “In the Heart of the Empire.”124 As always, Smallwood wrote positively and optimistically about what he was seeing and doing and whom he was meeting. But his accounts belied the harsh reality of a hand-to-mouth existence in England, as detailed in his troubled exchanges with the now hard-pressed Clara. There were many recriminations back and forth; in one missive she told him “I have not got a cent to mail a letter with.”125 The contrast in all this between Smallwood’s public and private selves reveals much about the energy, ambition, tenacity, and daring of a man in search of the main chance but whose sojourn in England was only the latest in a long, continuing series of many reverses in life. By nature a gambler, he took big risks and suffered hard losses — but, with good health, a thick skin, and seemingly boundless energy, was always ready for the next venture in life.

45 Writing on 24 January 1927 from 89 Guilford St. in central London, he told Clara that he had become so thin that she would hardly recognize him: “People remark it to me, and I have to tell them that I have been sick. I have not had enough food, and the worry has been even worse on me. This is Friday, and on Monday I didn’t have a solitary cent, so that I had to go to the Ivanhoe Hotel and take a room, knowing that I would at least get my meals there, and would not have to pay until Saturday” (he was hoping for payment for a collection of 30 photographs he had brought from Newfoundland and was attempting to hock).126 Having got to know the prominent Methodist preacher Rev. Ira G. Goldhart of the nearby Kingsway Mission, Smallwood toyed with the idea of starting a career in the clergy but this proved a passing fancy.127 By 16 February, he was reduced to hitting up Lady Squires, who had a flat in London (two Squires sons were at Harrow School), for a loan of £5. Telling her that he was in “deep water,” he explained that he had two job prospects — one with the Tottenham Labour Party and the other with the publisher George Newnes Ltd. — and needed the money to tide himself over to “some definite point — whether it be jail or the river or a good job, I sometimes have doubts!”128 He was “a lonely Newfoundlander in the most poverty-stricken city in the world,” with only his typewriter left to pawn, something he dare not sell. While apologizing for not delivering to date publications for which he had been advanced money in St. John’s by Sir Richard, he promised to repay expeditiously the loan he was now seeking or “burst in the attempt.” Writing from Carbonear a few days later, Clara reminded the now-desperate Joe of his promise to her mother that he would send for his wife in February. “We are hoping you will be up to your word,” she bitterly complained, “for the first time since I have known you.”129 With people wondering who was supporting her, she protested, she hardly went out so as not to be talked about.130

46 The one lasting success of Smallwood’s London sojourn came when Coaker arrived in the city on one of his periodic overseas business trips. He and Smallwood now quickly reached agreement about the publication of the biography of the FPU leader Joe had been itching to write. By his own account, Smallwood dashed the manuscript off in “three days and nights.” The 96-page book was published later in the year by the Labour Publishing Company under the title Coaker of Newfoundland: The Man who led the Deep-Sea Fishermen to Political Power and with this puckish inscription: “This Book is dedicated to Ramsay Coaker Smallwood by the Author of both.” The small volume incorporated much of what Smallwood had previously written about Coaker and the FPU. Coaker would “long be remembered by all as the father of the first attempt to place the fishery in all its phases upon a modern and scientific basis.” In sum, he was “the greatest Newfoundlander since John Cabot.”

47 Smallwood arrived back in St. John’s on 13 April 1927 and on the 27th Sir Richard Squires, who was rebuilding his political career, made this revealing entry in his diary: “Smallwood called on yesterday. He had just returned from England and said that my wife had been very courteous to him. Wanted me to understand whereas he had formerly said he would support me if Coaker was with me, he wanted now to say that he would support me in any event.”131 Smallwood meanwhile had reverted to form, writing letters to the editor on the public issues of the day and becoming secretary of an Unemployed Workers’ Committee, chaired by James McGrath, a former president of the Longshoremen’s Protective Union.132 Following a gathering of 250–300 unemployed men at Bannerman Park on 10 May, this committee appealed to the legislature for immediate relief for city workers.133 That same month, as correspondent for several foreign newspapers, Small-wood reported on the seaplane passage through Trepassey of intrepid Italian aviator Francesco De Pinedo.134 Later in 1927, with Clara and Ramsay still living in Carbonear, he moved to Corner Brook, arriving there just before the functional takeover of the mill by the Americanowned International Paper Company of Newfoundland Ltd. Through a connection with Royal Newfoundland Regiment veteran Major Bert Butler, he soon found a job with the new owner as a member of a topographical team, led by the company’s chief engineer, that assessed the Gander River area as a possible site for another pulp and paper mill.135 After the success of the Corner Brook mill, there would now be much talk in Newfoundland about putting “A Gang on the Gander.”136 Butler also held out the possibility of a job editing a company paper but this did not materialize. In December 1927, returned from the Gander, Smallwood was on hand for registration at a night school that would teach “mostly elementary subjects.”137 As Corner Brook correspondent for the St. John’s Daily News, he reported on this and many other events in the life of a growing community in which he assiduously built connections.

48 In February 1928, ambitious to be the Liberal candidate in dynamic Humber District, Smallwood clashed with local notable John R. Barrett of Curling. In a letter dated 10 February to the editor of the Western Star, published in his place of residence, Barrett cautioned readers to “guard against electing a person who may be looked upon as so much deadwood, driftwood, or any sort of flotsam or jetsam.”138 In the pending general election, there should be no place “for political adventurers or agitators, men who have been in the district scarcely long enough to get a haircut or a shave.” His words, Barrett thundered, had been prompted “by recent utterances of an irresponsible political adventurer in the Humber district, whose principal asset is the unlimited amount of unmitigated gall hidden beneath his cranium, and whose object is to foist himself by an ingratiating manner upon an intelligent electorate. To give earnest consideration to his vapourings would tend to lessen our standard of citizenship.” Though Smallwood was not named directly in this blast, there was no doubt that he was the object of the attack and he answered forthwith: “I suppose I ought to be ashamed of myself, and try and hold all this gall in check. And just as I start to get ashamed, I suddenly remember that ‘gall’ is another word for ‘nerve,’ and that ‘nerve’ is another word for ‘daring,’ and that ‘daring’ is another word for ‘boldness.’ And then I begin to wonder whether Humber District doesn’t need a little more gall, a little more boldness.”139 Answering Barrett’s claim that west coast districts should be represented by men who had their homes in them and therefore “something at stake,” Smallwood rejected the notion that only “local men,” in the narrow sense intended by his adversary, were qualified to run:

In a report for the Western Star in April 1928, Smallwood described the progress of the Orange Order in the developing Humber region; noting that the lodge at Deer Lake was the youngest in the country, he wished “All speed to them!”141 Though himself an agent of change, Smallwood well understood the role of tradition in shaping Newfoundland, even in the booming Humber area.

49 That same month, in a pointed and prophetic letter to the editor of the same paper, he mused on the current state of politics in Newfoundland, examining three panaceas being talked about to address the ills of the country: Confederation with Canada, reversion to “Crown Colony status,” and “Royal Commission rule” (in his disillusionment with party politics, even Coaker had come out in favour of the notion of government by elected commission).142 These schemes had “a common denominator.” One source of support was the sincerely held but mistaken belief that Newfoundland was incapable of governing itself. But another driving force was out-and-out Tory hatred of a resurgent Sir Richard Squires. In their desperation, he warned, his opponents “would almost rather sell Newfoundland to the devil” than see the Liberal leader back in the office of prime minister, but the writing was now on the wall for them in this regard. No Tory effort could stop the people from returning Squires to power “with the greatest electoral and parliamentary majority ever witnessed in this Island.” Ironically, in view of his later identification with the cause of union with Canada, Smallwood saw permanent disadvantage for Newfoundland within the Canadian federation:

Newfoundland had the “men of brains” needed to govern and transform the country, and putting them in charge would “very soon silence the calamity howlers and visionless croakers.” It was in boomtown Corner Brook that Smallwood saw first-hand what could be achieved by attracting international investment to resource development — a path to progress he would embrace wholeheartedly in the 1950s and 1960s. If Coaker’s legacy to Smallwood was commitment to social and economic uplift, that of Squires was a fixation on deal-making and resource development.

50 In May 1928, Smallwood acquired a new platform from which to campaign, when he became editor of a new weekly, the Humber Herald, published in Corner Brook by Humber Publishers Limited, an enterprise owned by businessmen J.M. Noel and M.A. Pickering.143 On the first page of volume one, number one, of the paper, dated 26 May, Smallwood’s name was highlighted and the Humber area characterized as “This NEGLECTED District.” Ultimately, however, Smallwood’s goal of representing the area in the legislature was overtaken by Squires’s decision to run in Humber himself. Smallwood had to content himself with campaigning alongside the Liberal leader, but the outcome of the general election, held on 29 October, was greatly to his satisfaction. The Liberals swept to victory, and on 17 November 1928 the previously disgraced Squires again became prime minister of Newfoundland. For his own efforts on behalf of the party, Smallwood was recommended, on 21 December, to be made a justice of the peace,144 a distinction that allowed him to use the letters J.P. after his name (he would long be attracted to honours and awards and well understood their place in greasing the wheels of politics). Meanwhile, on 30 September 1928, he and Clara — reunited in Corner Brook but living in cramped quarters — had had their second child, another son and a brother for Ramsay. Named William Richard Squires,145 he became affectionately known in the family as “Billie.”

51 On 12 August 1929146 Smallwood left for New York on holiday, sailing to Baltimore on the SS Corner Brook, a newsprint carrier,147 and then travelling by train. “It has been a beautiful trip,” he wrote the again pregnant Clara while on the ocean voyage south: “The water has been as smooth as Bay of Islands, and except for two days and nights of dense fog — during which the ship’s whistle blew steadily every three minutes — the weather has been magnificent.”148 After the testing early phase of their marriage, life seemed to be settling down for the couple — but not, it turned out, for long. Soon after his return from the United States, Smallwood ran into legal difficulty when local businessman Edward Barry sued him, as editor of the Humber Herald, and J.M. Noel, as managing director of the paper, for $10,000.149 The basis of Barry’s claim, which was started in the Supreme Court of Newfoundland on 21 September, was an article Smallwood had written in the newspaper on 3 August condemning as unseaworthy the George L., a vessel Barry used for a government-contracted ferry service around the Bay of Islands. According to Smallwood, the “boat was a “rattle-trap” — a “tiny, stinking, oily, slow tub that can’t carry enough freight, that travels like a snail, that herds men and women and children passengers up amongst barrels of herring and oil piled high on the blubbery deck, that hasn’t got any toilet arrangements, that isn’t fitted to serve a meal to passengers.”150 Barry was represented in the action by the St. John’s law firm of Winter and Higgins, and Smallwood and Noel by Raymond Gushue. In their statement of defence, the respondents denied any libel and made the case that the words being complained about were “true in substance and in fact.”151 They had, moreover, been written “honestly and in good faith and without malice.” But two days before this document was filed with the court, Noel visited Barry and offered to meet the costs of the case, publish an apology in the Humber Herald, disassociate Smallwood from the publication (the Western Star had already reported that he had left his post),152 and not publish any more articles by him — if Barry would drop his suit. On this basis, the action was discontinued, Barry having told his solicitors that Smallwood “had no interest in the paper or any money or property which we may attach.”153

52 Soon afterwards, on 7 January 1930, the last of the Smallwood children, a daughter named Clara, was born in Corner Brook (unlike her brothers, she was not named to honour any politician).154 In February of that year, without steady employment and in need of a fresh start, Joe went back to New York, where he met with an editor for Macmillan to pitch his latest book idea, a volume about contemporary Newfoundland.155 While he awaited word from the publisher, he met with Squires, who was also in the city. The prime minister liked what he heard from Smallwood and immediately got behind his book project, giving him $100, offering him more help if he found himself “up against it” pending a commitment from the publisher, and arranging free passage for him back to St. John’s on a ship of the Furness Withy line.156 Having got a green light from the publisher, Smallwood stopped in St. John’s on his way home to do research for his book. 157 He was followed back to Corner Brook by a variety of consumer items — religious statuettes and cards, Easter cards, playing cards, and gramophone records — which he had acquired in the United States with a view to resale locally by brother-in-law Bill Oates. 158 Always the unabashed self-publicist, he also brought back photographs he had had taken of himself, describing them to Clara as “beauties.”159

53 By May 1930 he was back in St. John’s, working on the Liberal campaign for by-elections held on the 17th of that month to fill vacancies caused by the deaths of three members of the House of Assembly (one of them George Grimes) in 1929. Smallwood published articles in support of the government’s cause in the Liberal Press and the FPU weekly, the Fishermen’s Advocate, and these were then reprinted as pamphlets for distribution in the districts in play. Squires praised the pamphlets as “the best he ever read.” 160 Smallwood bet that the Liberals would win all three seats and won his bet. 161 One of the new members returned was Lady Squires, who was elected in Lewisporte, thereby becoming the first woman to sit in the House of Assembly. While in St. John’s on this mission, Smallwood sent Clara a baby carriage, a vacuum cleaner, and a gramophone, the latter to stimulate the sale of records in which he was already involved.162

54 Returned to Corner Brook and now a well-established Squires operative, he served on a committee that drafted a public address to Governor Sir John Middleton, who visited Bay of Islands with Lady Middleton on 7 June 1930.163 The address was printed and illuminated by the Western Star and the text was linotyped courtesy of J.M. Noel of the Humber Herald.164 The address exemplified the Newfoundland boosterism to which Smallwood had long been drawn and in the expression of which he excelled:

No doubt, such sentiments — the words in the address were typical of him — were much in Smallwood’s mind when he headed back to New York on 15 July (sales associate Bill Oates travelled on the Corner Brook with him)166 to advance matters with Macmillan.167 Shortly after he left on this trip, son Billie was knocked down in Corner Brook West by a horse and suffered scalp wounds.168 The toddler was hospitalized overnight, but in the end all was well. As Joe pursued his latest literary quest, Clara clearly had her hands full.

55 Smallwood returned home in October 1930 169 and the next month was in St. John’s, where a deal was in the making that led him to move permanently to the capital.170 If Smallwood had imbibed idealism from Coaker and his circle, he was now being well schooled by the crafty Squires in the dark arts of patronage and party management. Beginning on 14 February 1931, he brought out a pro-Squires newspaper mischievously called The Watchdog, the opposition’s mouthpiece being labelled The Watchman. Based at the Labour Press publishers and printers, 10 George St., Smallwood was initially paid $25 a week for his efforts, but lived in hope that his patron Squires would find him “an additional job.”171 When the principals of The Watchman issued a legal challenge to the name chosen for Smallwood’s new paper, the court ruled against them.172

56 While thus busily engaged, Smallwood also scrambled to find housing so that he could reunite the family. He hoped for something better than the four rooms they had been occupying in Corner Brook for the last two years, but cautioned the understandably anxious Clara that all this might take time: “I can’t catch a man by the throat and force a house out of him. I have got to wait until there is a house.”173 A limiting factor, moreover, was his inability to take a year’s lease.174 In March, on a visit to her family in Carbonear, Clara told him she had an “empty purse” but had “to buy medicine for the children.”175 Manifestly, the Smallwoods were once more up against it.