Papers on the Basques in Newfoundland and Labrador in the Seventeenth Century

In the Midst of Diversity:

Recognizing the Seventeenth-Century Basque Cultural Landscape and Ceramic Identity in Southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon

1 This paper lays out a spatial, archaeological, and cultural framework for studying the Basque cod fishery in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon. From the first half of the sixteenth century onward, this region was a major destination for Basque transatlantic fishermen (Barkham, 2009). Loewen and Delmas (2012) have suggested that the region held the greatest concentration of Basque cod fishermen in all of eastern Canada throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, attracting crews from both Spain and France. They hypothesized that Placentia Bay was the core area of the Basque cod fishery from which it expanded to several areas around the Gulf of St. Lawrence, reaching its apex between 1630 and 1713.

2 However, little historical and archaeological research has been conducted on the Basque presence in this region, and many questions remain. Not least, we lack confirmation of the number of ships that fished in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, and the proportion that they represented of the total Basque fleet in the Gulf. Knowledge has also remained somewhat anecdotal on the ports where Basques fished, and we lack an overall portrait of their distribution in the region. We will address these historical questions, based on the analysis of a 1677 Basque pilot book by Piarres Detcheverry and a 1676 annotated map by the French naval officer Courcelles.

3 From an archaeological perspective, we may identify two related questions. First, material culture studies have shown that Basque- related ceramics evolved over time and space. At the early end of the 250-year continuum of Basque presence, Iberian ceramics predominate on pre-1630 sites in the northern Gulf, from Labrador to Tadoussac (Gusset, 2007; Escribano-Ruiz and Barreiro Arguëlles, 2016). At the later end, only a few specifically Basque ceramics occur among otherwise typical French pottery on sites from 1713 to 1760 around the southern Gulf (Chrestien and Dufournier, 1995; Loewen and Delmas, 2012: 384–88). Centrally positioned along this continuum, both in time and space, seventeenth-century assemblages from southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon hold a key to understanding the shift in Basque-related ceramic provenances (Dieulefet, this volume). Geopolitical and commercial factors at play in New France and in the Basque Country allow us to suggest reasons for the seventeenth-century shift in Basque ceramic provenances.

4 Second, we must bear in mind that Basques were not the only Europeans in this region, where they rubbed shoulders with fishermen, merchants, and naval officers from La Rochelle, Nantes, and Brittany (Crompton, 2017; Landry, 2008 and this volume). This cultural diversity brings an added dimension to the challenge of recognizing seventeenth-century Basque material culture, which evolved to include more “French” ceramics. We argue that despite their transformation, Basque assemblages retain certain “low-frequency” ceramic types that were unique to the Basque supply chain, while lacking certain ceramics that were particular to other cultural groups, thus making it possible to detect a Basque supply chain in archaeological collections (Chrestien and Dufournier, 1995; Delmas, 2018; Dieulefet, this volume). Pushing this view further, we seek to understand cultural diversity among the various groups that archaeologists have often lumped together as “French.”

Theorizing Archaeological Diversity in the Atlantic

Cultural diversity in the distant fishery

5 The long-distance fishing activities of Europeans between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries significantly increased the cultural diversity of the North Atlantic territories of America. Fishing crews from England, especially Bristol and its economic hinterland, followed the wake of John Cabot, who visited Canada’s Atlantic littoral and probably Newfoundland at the end of the fifteenth century (Pope, 1997: 5). Breton, Norman, and southwestern French fishermen also frequented the western shores of the North Atlantic in the early sixteenth century, as did crews from the Basque Country and Portugal (Turgeon, 1987). While many historians have emphasized the cultural diversity that characterized North Atlantic fishing during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Abreu-Ferreira, 1998; Brière, 1990; Gray, 1988; Harrington, 1994; Innis, 1954; Litalien, 1993; Pope, 2004, 2008; Trudel, 1963; Turgeon, 1987, 2000, 2009), archaeological analysis of fishing settlements and their material record often cloaks this diversity.

6 In fact, the archaeological record frequently has been interpreted according to very broad cultural categories — for example, a site will be labelled only as English or French. In so doing, regional identities are obliterated and distinctive maritime cultures are subsumed under vast state entities. This way of interpreting identity is certainly influenced by our understanding of geopolitics in which state unity is paramount and state nationalism is used to promote socio-cultural cohesion. We should keep in mind that, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, regional identities were very strong, especially on the Atlantic facade of France and Spain. Such is the case for Normandy, Brittany, southwest France, and the Basque Country, which were brought within the borders of France or Spain during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, at a time when long-distance fishing was gaining in importance and reinforcing the regional capitalist economies of these cultural communities.

7 In order to fully grasp the experience of European fishermen sailing across the North Atlantic, we must acknowledge this regional cultural diversity and seek to detect its material expression on the Atlantic’s western coastlines. We must also recognize the creation of new identities associated with fishing sojourns and settlements in North America (Silliman, 2005). Fishing crews did not directly transpose a Breton, Norman, or Basque way of life into North America, since their behaviour and practices were also conditioned by the environmental, social, and cultural context in which their fishing activities were performed. In light of these considerations, we see a need to revisit the cultural hermeneutics of early fishing sites in and around Newfoundland, including Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon.

Archaeology of the Basque Presence in Newfoundland

8 Sites like Red Bay, which is associated with the Basque presence in Labrador, as well as the research led by Peter E. Pope in the Petit Nord (the Atlantic coast of Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula), have provided much information on the exploitation of marine resources in Canada’s Atlantic coast by continental Europeans (Pope, 2008). Even Ferryland, an iconic site on the Avalon Peninsula best known for its association with the Calvert family, encompasses a French occupation (Gaulton and Tuck, 2003). While French fishing contexts are not anecdotal in Newfoundland and Labrador, archaeological knowledge of Franco-Iberian fishing activities in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon remains surprisingly general.

9 In southern Newfoundland, according to the site inventory of the Provincial Archaeology Office, only four sites contain a possible Basque cultural component. These are the probable Basque component of Fort Louis in Placentia (ChAl-9), the Basque burials near St. Luke’s Anglican Church, also in Placentia (ChAl-17), and a presumed Basque shipwreck at Oderin Island in Placentia Bay (ChAq-1). A fourth site has recently been proposed for this list, as materials from the Isle aux Morts shipwreck have been associated with Basque outfitting networks (Dieulefet, this volume).

10 Given the scarcity of hard data, a theoretical model is needed to envision the cultural reality of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century fishermen, before the titanic clash of England and France indelibly printed imperial boundaries on political maps and people’s minds. We need to imagine a transnational territory that was occupied seasonally by multiple groups who produced and reproduced their cultural identities, within the shared objective of harvesting marine resources. In an evocative example, in 1578, Anthony Parkhurst counted 350 fishing vessels in Newfoundland, of which 150 were Norman or Breton, 100 were “Biscayan,” and only 50 were English. Not only does Parkhurst’s census show the great number of fishing crews that shared the territory, but also it emphasizes their cultural diversity, particularly those from France (Pope, 2004: 19).

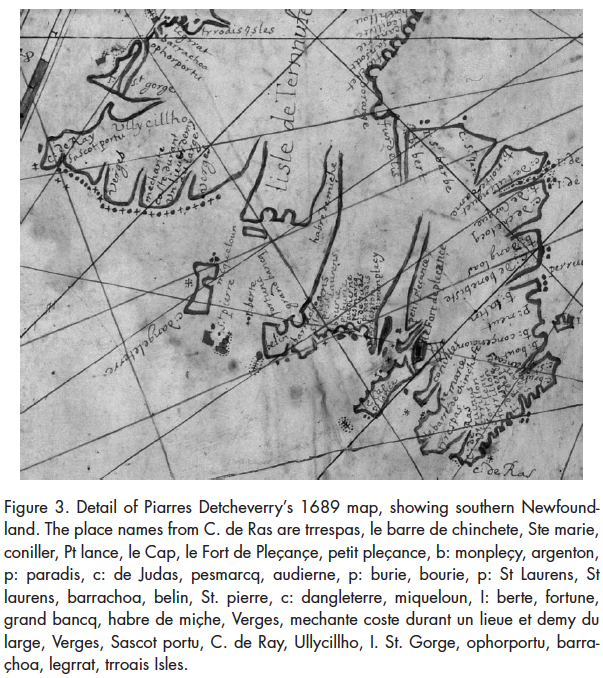

The Basque Fishing Fleet and Its Regional Distribution

11 One of our goals is to quantify the Basque fishing fleet and map its distribution in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon. We will show that, within the overall Basque fleet that was grouped in several regions around the Gulf of St. Lawrence and its Atlantic gateways, a majority of Basque ships fished in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon.

12 Although Basques are perhaps better known as whalers, the dry cod fishery was the backbone of their transatlantic economy, employing a fairly constant number of ships and men while other activities waxed and waned. Basque whaling in Labrador, at its height in the 1570s, attracted 30 large ships and 2,000 crewmen, half of whom were based at Red Bay. In addition, Parkhurst found 70 “Biscayan” (i.e., from Spain) ships that were fishing for cod around Newfoundland, employing another 2,700 or so men and boys. Even though intensive whaling collapsed in 1579, Basque cod fishing never wavered. A level of 3,000 sailors has been reconstructed for 1625 and 1631, when records are available (Loewen and Delmas, 2012: 378–79). Based on an average crew of 35 to 40, this number of sailors translated into 75 to 85 ships, averaging 150 tons each (Turgeon, 2000).

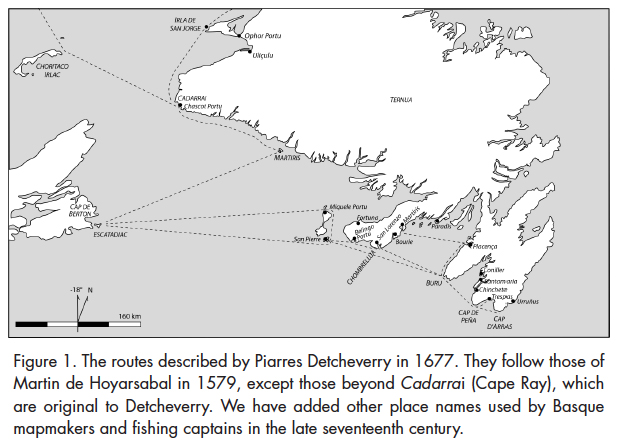

13 Within the Basque Country, the three maritime provinces contributed unequally to the transatlantic fleet. Well over half of all Basque ships and crewmen typically came from Gipuzkoa in Spain, with the remainder hailing in roughly equal numbers from Bizkaia in Spain and Lapurdi in France. These overall numbers likely represented the maximum crewing capacity of the Basque ports. In 1651, in a surge of optimism, Saint-Jean-de-Luz outfitters hoped to send 4,000 men across the Atlantic. This ambitious goal represented more than twice the total number of all sailors living in Lapurdi, and Luzien outfitters planned to make up the shortfall by recruiting in Gipuzkoa (Azpiazu, 2016: 201–03).

14 As a result of geopolitical factors, the destinations of the Basque fleet varied over time. In the seventeenth century, Basque ships and crews tended to separate into two groups that headed to different areas of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. The first group, comprised of Basques from Spain, sailed to Labrador, the northern Gulf coast, and the Port-au-Choix region of Newfoundland. These successors to the intensive sixteenth- century Labrador whale hunt combined whaling, sealing, fishing, and the Inuit trade. The region they knew as Gran Baya was gradually brought under French control between 1661 and 1703, in a series of land grants that pushed the colonial frontier eastward from Tadoussac to Brador. Although the coastline available to “Spanish” traders and fishermen slowly decreased, historical data show that the Basques remained in Labrador throughout the seventeenth century (Loewen, 2017). The number of ships in the northern fleet is hard to estimate for this period, but it likely did not surpass 10 or 15 in a given year.

15 The second group of Basque ships was significantly more numerous, and these were crewed by fishermen from both Spain and France. These ships fanned out to ports in Cape Breton Island, Chaleur Bay, southern Newfoundland, and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, as well as western Newfoundland as far as the Bay of Islands. Numbering from 75 to 85 ships, the southern fleet hailed from the Basque provinces in both France and Spain. Most headed to ports in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, where Basques shared the maritime landscape with crews from various regions of France. As late as 1763–1818, the colonial correspondence of Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon shows that ships from the Basque Country regularly called at Saint-Pierre. In 1768, the port registry identifies 10 vessels from Saint-Malo, four from La Rochelle, and one each from Le Havre, Saint-Pierre (perhaps in Martinique), Granville, and Bordeaux. Additionally, we find six Basque ships outfitted in Bayonne and one in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, making up 28 per cent of the traffic from France (Anonyme, 1768).

Basque Ports and Routes: Reconstructing the Basque Cultural Landscape

16 Reconstructing the Basque cultural landscape in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon relies on a group of maps produced in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, especially by Denis de Rotis in 1674 and Piarres Detcheverry in 1689. The maps show a wealth of Basque place names in Newfoundland and around the Gulf of St. Lawrence (Egaña Goya, 2002). Of even greater insight to the Basque cultural landscape is Detcheverry’s pilot book or routier, published in Bayonne in 1677 (Detcheverry, 1677). This unique work has not been fully appreciated as a source for Newfoundland history and archaeology, in part because it is written in rather technical seventeenth-century Basque, and in part because its title page somewhat misleadingly describes it as a translation of a 1579 Basque pilot book written in French, by Martin de Hoyarsabal (Hoyarsabal, 1579; La Roncière, 1904; Oregi, 1987; Barkham, 2003). To aid the future use of these two Basque routiers, we have set their passages concerning southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon side by side (see Appendix), and we will follow Detcheverry’s text in our reconstruction of the seventeenth-century network of Basque ports and routes in this region.

17 Martin de Hoyarsabal’s pilot book, first published in 1579, was reprinted in various French ports in 1632, 1633, and 1669 (Barkham, 2003). We may assume that it came into the hands of Piarres Detche- verry and his contemporary pilots, who saw the need for an updated version in the Basque language. The two works remained closely related, in the tradition of early pilot books, circa 1300–1700, where the “blood-lines” of proven knowledge were watchfully maintained and purified (Sauer, 1996: 13). Given this conservatism, each difference between the two Basque pilots is highly significant for the history of Basque navigation to the region.

18 While Hoyarsabal covered the coasts of southern and eastern Newfoundland, Detcheverry omitted much of eastern Newfoundland and added original descriptions of western Newfoundland and Chaleur Bay, where Basques had begun fishing in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries (Barkham, 1989; Loewen and Egaña Goya, 2014). As for southern Newfoundland, side-by-side comparison of the two routiers confirms their basic similarity, indicating that Basque routes and ports remained fairly stable in this region over the century between the two pilot books. However, Detcheverry changed or added some details, especially in the Placentia area.

19 Born in 1636 or 1637 to a Saint-Jean-de-Luz family of captains and outfitters, Piarres Detcheverry towers above other informants on the seventeenth-century Basque cultural landscape in the New World (Loewen and Egaña Goya, 2014). His sailing instructions in southern Newfoundland begin on the Cape Breton coast, at Eskatadiak (Scatarie). This island is the starting point for routes radiating to San Pierre (Saint-Pierre), Michele Portu (Miquelon), Martiris harbour (Ramea Islands), and Isla de Sablat (Sable Island). In each case, the heading provided by Detcheverry is accurate, but the distances given in leagues of three nautical miles (5.55 km) often underestimate the true distance. Detcheverry mirrors Hoyarsabal in his use of central points and radiating routes, and the resulting lattice of nodes and connections forms an integrated, multi-centred cultural landscape. Extending westward from Martiris is the leg to Cadarrai (i.e., “cap de Ray”), where Detcheverry advised pilots to stay three leagues from the coast to avoid the many rocks, or bachac (from “bajas”). For this route, Detcheverry clarifies the confusing text of his predecessor, and he also uses it as the connecting leg to his original description of routes and ports in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. One senses Detcheverry’s personal knowledge heightening as he approaches the confines of the Gulf.

20 The next central point is San Pierre, where pilots used the nearby high island of Colunbia (Grand Colombier) as a local seamark. From here, Detcheverry directs his readers to Buru (Cape St. Mary’s), Miquele Portu (Miquelon), and Belingo Portu (Lamaline) on the Burin Peninsula, from where he carries the route along the coast to San Lorenzo (St. Lawrence).

21 Detcheverry’s next passages describe the Atlantic approach to Placentia Bay. From Cap d’Arras (Cape Race), his routier guides us westward to Cap de Peña (Cape Pine) and then to Cape St. Mary’s, which he simply calls Buru, or the Headland (literally, “forehead” or “brow”). Cap de Peña is named after a cape near Gijon, on the Cantabrian coast of Spain, where sixteenth-century whalers took their last sighting before charting a course to the Strait of Belle Isle (Loewen, 1999: 93). From its Newfoundland namesake, a short spur leads to Trespas (Trepassey), while Detcheverry’s main route continues westward to Buru, where he warns of rocks (bachac) lying two leagues east of the cape itself. Up to this point in his text, Detcheverry follows Hoyarsabal except for renaming Buru with a generic simplicity that suggests its pivotal place in sailors’ mental construction of the southern Newfoundland seascape.

22 From Buru, Detcheverry describes three radiating routes: back to San Pierre, north along the coast to Placença (Placentia), and across Placentia Bay to the prominent dome-shaped seamark of Chombrellua at the entrance of San Lorenzo harbour. Chombrellua (Mount Soker) was known as “Chapeau Rouge” to French-speaking sailors who extended this name to all of the Burin Peninsula. For Basque mariners, Chombrellua was a place name that they also gave to at least two other sugarloaf headlands, at Fox Harbour on Argentia Bay and at West St. Modeste in southern Labrador. The latter also appears in 1564 as Sonbrero (Barkham, 1987: 94, 113). The three place names — chombrellua, chapeau, and sombrero — all refer to hats and they conjure an anthropomorphic image that, along with buru ( “brow”), provides an insight into seventeenth-century sailors’ conceptualization of their cultural landscape.

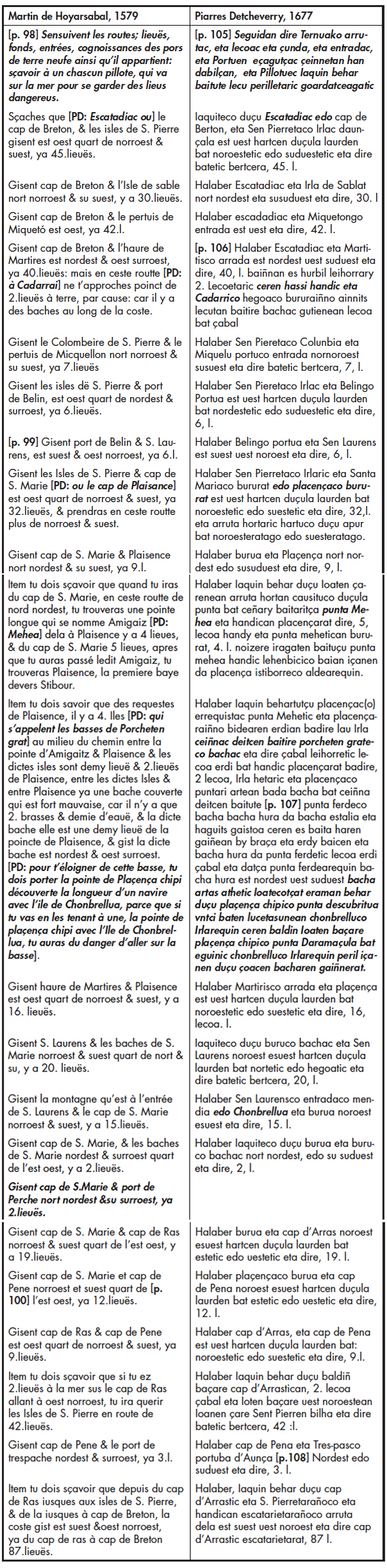

23 Sailing along the coast from Buru to Placença, we follow Detcheverry into a densely named region that had developed greatly since the time of Hoyarsabal. Four leagues (22.2 km) north of Buru, Detcheverry points out Punta Mehea (“fine point”) — today’s Point Breme — that Hoyarsabal knew as Pointe d’Amigaiz (“bad cliff point”). 1 Here, the coastline subtly changes direction and this seamark reminded pilots to adjust their course and begin rehearsing for the dangers awaiting them on the last five leagues to Placentia.

24 Halfway along this last stretch are four rocky islets lying half a league offshore, which Detcheverry calls placençac errequistac.2 This name is borrowed from Hoyarsabal’s les requestes de Plaisence, which uses an old term for an offshore reef that pilots should take heed to avoid while following a coast. Today this reef is called the Virgin Rocks. Detcheverry also calls them porcheten grateco bachac, meaning the rocks of Porcheten Flake. We do not know the meaning of porchet, nor do we find a French equivalent in Hoyarsabal’s routier. However, we find a phonetically similar word for Port de Perche, which Hoyar- sabal locates farther south (possibly St. Bride’s). Despite their phonetic similarity, porchet and perche occur at different places in the two routiers and their locations are geographically distinct.

25 It is unclear whether Detcheverry corrected or confused the location of Hoyarsabal’s Port de Perche, or whether porcheten grateco bachac was a secondary name for placençac errequistac. A possible solution lies in the place name itself, since porcheten grateco bachac appears to be named after a grat (flake or dégrat) on the adjacent coast. This would be today’s Great and Little Barrasway, derived from barratxoa, meaning a small bar or beach, a widespread Basque toponym that is preserved in French as barachois and was historically associated with a fish-drying function. We may suggest that Great and Little Barrasway were named Porcheten Grat by seventeenth-century Basque fishermen who came here to dry fish when Placentia became too crowded. 3 While local fishermen had created a new place name, long-distance pilots continued to use the old place name since the time of Hoyarsabal, les requestes de Plaisence, because of its mnemonic function of signalling their approach to Placentia harbour.

26 Nearing Placentia, Detcheverry warns of another shoal hidden under two and a half fathoms of water, lying half a league southwest of Punta Ferde (Point Verde). He names it punta ferdeco bacha. These toponyms replace Hoyarsabal’s more generic place names of Pointe de Plaisence and bache couverte (covered rock, or shoal), although Detche- verry also uses the older Placençaco Punta (Pointe de Plaisence). Thus we see the evolution of local toponymy around Placentia as the landscape had become more densely occupied and more precisely named during the interval between Hoyarsabal and Detcheverry.

27 North of Placentia, the landscape had evolved to an even greater extent since the sixteenth century. Whereas Hoyarsabal’s text does not go north of Placentia, Detcheverry describes several places around present-day Argentia. He mentions Placença chipi, translated as Petit Plaisance on his 1689 map and called Placencia menor in 1603 by fishermen from Mutriku, Gipuzkoa (Barkham, 1987: 154, 184). Detcheverry tells pilots how to enter the harbour by lining up the point of Placença chipi with a dome-shaped hill in the background called Chombrellu, then separating the two seamarks by “the length of a ship.” Like Porcheten Grat, Placença chipi was a post-Hoyarsabal expansion of the Basque cultural landscape around Placentia.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

28 A final route given by both Basque pilots heads from Placença to Martiris, 16 leagues (48 nautical miles) to the west. While this name also designated the Ramea Islands, in this case the directions lead us to Mortier Bay on the Burin Peninsula, a small port north of Burin. We note the phonetic similarity of Martiris and the English pronunciation of Mortier. This is the third time that Detcheverry describes a sea route to the Burin Peninsula — after those from San Pierre to Belingo Portu and from Buru to Chombrellua. These ports on the Burin Peninsula thus appear as independent points that were offset from nodes located many leagues away in the pilots’ mental map, and not as a string of interrelated ports that followed each other. Again, we see that long-distance pilots and regional fishermen constructed their landscapes at different geographical scales and also according to different ways of experiencing the landscape, as we noticed in the double name of placençac errequistac and porcheten grateco bachac.

29 Other sources flesh out the Basque maritime landscape in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon. One of these consists of hearings by the Spanish Navy into the Newfoundland fishery, held at San Sebastián in 1697. Noted by the Argentine historian Enrique de Gandía in 1942, this source on Newfoundland history is overdue for an in-depth analysis (Gandía, 1942: 46–61). 4 Its context was the war of 1689–98 and, particularly, a blockade by French corsairs off Cape Race in 1696 that forced Gipuzkoan ships headed for Placentia Bay to detour all the way through the Strait of Belle Isle (Loewen, 2017). During the hearings, veteran Gipuzkoan captains identified their usual fishing spots and described their relations with French authorities. Despite the specific context, the captains testified that French authorities in Newfoundland had never troubled them in the pursuit of their fishery. Nor did they make any effort to dissimulate their favoured ports, naming four in western Newfoundland and no less than 16 in the south.

30 Among these ports, San Pierre, Miquele Portu,and Portu de Placencia were most frequent destinations of Gipuzkoan outfits. Along the Burin Peninsula, they also fished at Fortuna (Fortune), San Lorenzo Andía and Chumea (Great and Little St. Lawrence), Buru Andía and Chumea (Great and Little Burin), as well as Portu Paradis (Paradise). East of Cape St. Mary’s, they fished at Conillas or Cuniller (Admiral’s Beach), Santamaria, Trespas, Baia de Vizcaya,and, according to de Gandía, Renews.

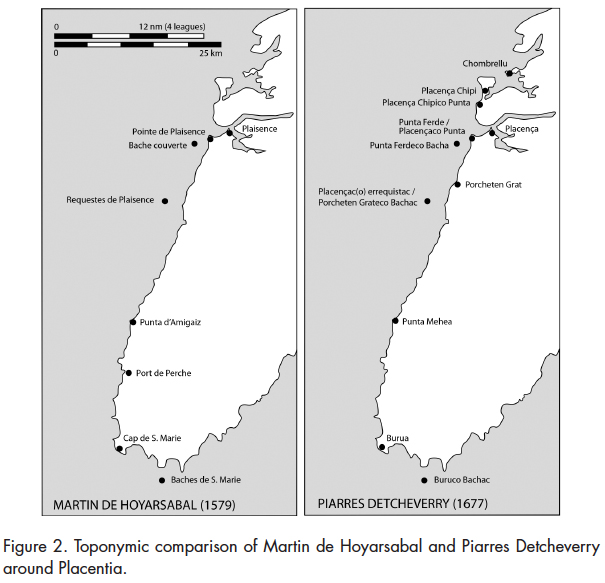

31 Another source for reconstructing the Basque maritime landscape is Detcheverry’s own map from 1689, which shows several additional ports along the Burin Peninsula and around St. Mary’s Bay (Figure 3). Two places, Barre de Chinchete and Sascot Portu, are not mentioned in Detcheverry’s routier or by the fishing captains. In all, we glean more than 30 Basque toponyms in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, not counting several examples of the generic Barrachoa. This region doubtlessly holds the greatest density of Basque toponyms of any region around the Gulf of St. Lawrence, providing a framework for the Basque maritime landscape.

Display large image of Figure 3

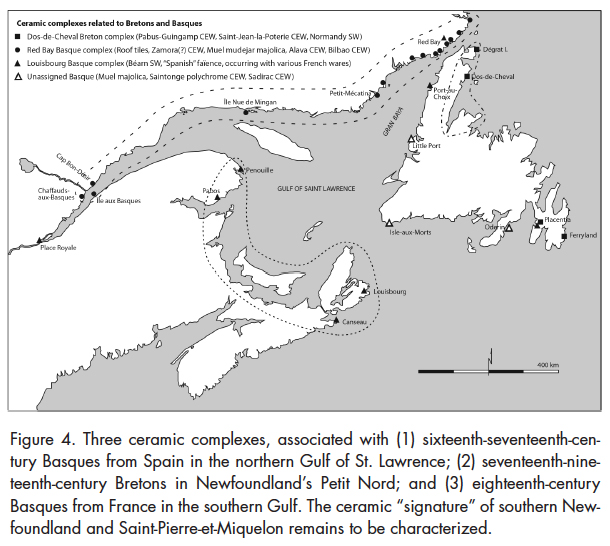

Display large image of Figure 3

The Basque Fishing Fleet in Southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon

32 In addition to holding the largest number of Basque fishing ports, southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon also attracted the greatest number of Basque ships, likely surpassing those in all other regions combined. As we have demonstrated above, the seventeenth-century Basque cod fishing fleet on the Atlantic coast and around the Gulf of St. Lawrence hovered between 75 and 85 ships. This number excludes the mixed fleet of 10 to 15 ships that headed from Spain to Labrador. Based on an estimated subtotal of 25 to 30 ships in Cape Breton, Chaleur Bay, and western Newfoundland, 5 we may judge the number of Basque outfits in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon at somewhere between 45 and 60.

33 Basques were not alone in this region, which they shared with outfits from Nantes, La Rochelle, and Brittany, especially the Saint-Malo region (Landry, this volume; Crompton, 2017). However, our analysis of another source, an annotated map by the French naval officer de Courcelle (Courcelle map 1676; cf. Harrisse, 1968: 319), suggests that Basque ships formed the largest contingent in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon. In 1675, de Courcelle navigated around Newfoundland, stopping at 55 ports where he encountered ships from France. In all he counted 173 ships, including 86 in the Petit Nord where crews from northern Brittany dominated (Table 1). The remaining 87 ships were in southern and western Newfoundland, where Basques customarily fished. If we assume that all 12 ships in western Newfoundland were Basque, that leaves 75 ships from all cultural groups in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon. Thus the Basque contingent of 45 to 60 units formed the majority — between 60 and 80 per cent — of all fishing ships in this region. Of a total of 2,600 to 3,000 seasonal fishermen in this region, Basque crews numbered between 1,600 and 2,400 sailors in a typical year.

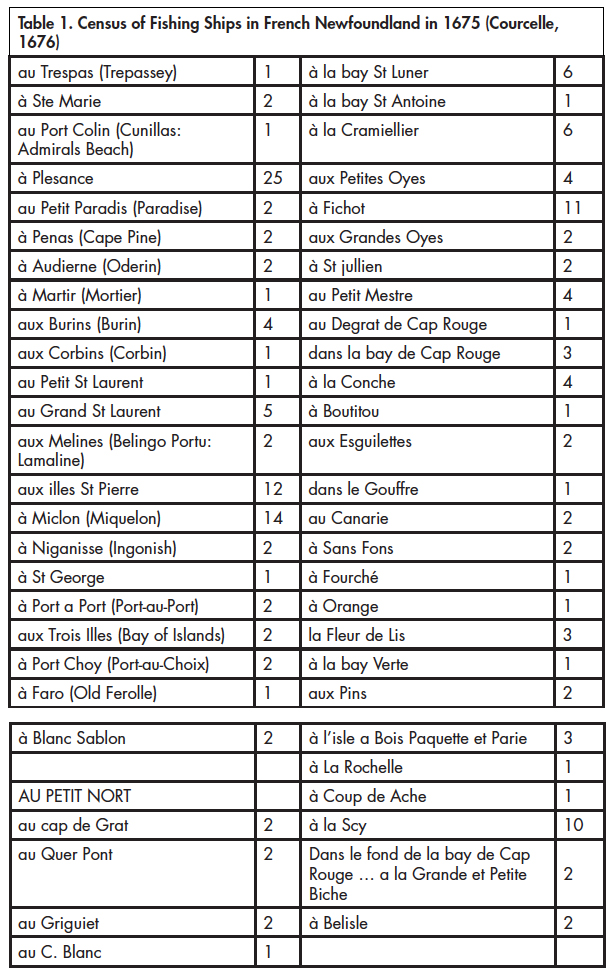

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 134 Of the 15 ports in this region visited by Courcelle, the most popular fishing destinations were Saint-Pierre with 12 ships, Miquelon with 14, and Placentia (including Petit-Plaisance) with 25. These three ports attracted two-thirds of all ships in the region. Another 20 ships were dispersed among eight ports along the Burin Peninsula, especially at the Burins and at Grand and Petit Saint-Laurent. Courcelle encountered only six outfits east of Cape St. Mary’s — at Admirals Beach, St. Mary’s, Peñas (Cape Pine), and Trepassey.

35 While we do not know which of these ships were Basque, Breton, Rochelais, or from other places in France, Courcelle’s data allow us to weight the fishing ports according to the number of vessels they attracted in 1675. In this maritime landscape, crews from the Basque Country (Spain and France) formed a majority, while outfits from elsewhere in France made up 20 to 40 per cent (15 to 35 ships) of the seasonal fishing fleet. Historical data do not allow us to be more precise, but an archaeological approach can shed light on the cultural interplay at work in seventeenth-century southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon.

French Influence on Basque Transatlantic Outfitting

36 Mingling of Basques with Bretons, Rochelais, and other French fishermen raises the archaeological challenge of identifying and distinguishing the different cultural groups that were present in seventeenth-century southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon. Heightening this challenge is the shift over space and time of the Basque archaeological “signal” as we know it. While this shift was doubtlessly complex and multi-faceted, before 1630 Basque whaling sites in the northern Gulf of St. Lawrence are characterized by mostly Iberian pottery (Gusset, 2007; Escribano-Ruiz and Barreiro Arguëlles, 2016). After 1713 in the southern Gulf, a Basque presence on cod-fishing sites has been recognized by a small number of Basque-specific ceramic types that occur among a majority of common French types (Chrestien and Dufournier, 1995; Loewen and Delmas, 2012: 385–88). Data on the intervening period, and especially from the major region of southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, remain sparse and imperfectly understood (Loewen and Delmas, 2012: 383; Delmas, 2018; Loewen, 2017: 171–74).

37 From a material culture standpoint, the challenge of distinguishing cultural groups involves separating two cross-cutting archaeological tendencies. On one hand, owing to the regional nature of European coastal economies, ceramic provenances are tied to the supply chains and home ports of transatlantic fishing ships. Specifically, Basque, Rochelais, or Breton ceramics that had a restricted regional market in Europe can also identify fishing outfits from the same region (Chrestien and Dufournier, 1995; Dagneau, 2009; Pope et al., 2008; Escribano-Ruiz and Barreiro Arguëlles, 2016). While some regional ceramics eventually expanded to reach an interregional market, especially faiences, Domfront stoneware, and Sadirac-style green-glazed coarse earthenware that were available in many French ports, such success stories were exceptions to the rule, even though their products could account for a large proportion of finds on a given site (Dagneau, 2009).

38 Opposing this regional ceramic signal, in seventeenth-century southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, various historical and archaeological factors could have a mixing effect on ceramic assemblages. Taking the Basque example, during wartime, French naval authorities obliged captains from Spain to purchase supplies in France in order to fish in New France, thus increasing the frequency of French ceramics on Basque sites at the cost of Iberian products (Turgeon, 2000: 174–75; Lugat, 2006; Aragón Ruano and Alberdi Lon-bide, 2007; Dieulefet, this volume). In addition, Rochelais and Nantais merchants peddled their wares at fishing stations throughout southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, including Basque ports (Crompton, 2012: 68–72; Crompton, 2017; Landry, 2008 and this volume). Finally, successive occupations by Basque, Breton, or Rochelais crews on the same site could mix the ceramics of each cultural group within the same stratigraphic levels (sensu Pope, 2017: 48). Sorting out these factors in ceramic assemblages to identify a site’s occupants requires a new level of understanding for each ceramic type found on “French” sites in Newfoundland and around the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

A Tool for Recognizing the Basque Archaeological Profile of Southern Newfoundland

39 While the discovery of Basque fishing sites is a likelihood in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, shifts in Basque material culture provenances and the inflow of Breton, Rochelais, and other French artifacts leaves archaeologists with the challenge of recognizing seventeenth-century Basque material culture. Our purpose here is to suggest a framework that can help to identify a Basque presence in a region that was visited by fishermen from several regions in France. Beyond this methodological challenge, there is a hermeneutic need to embrace the cultural diversity of the region and avoid masking regional diversity by lumping together sites that are characterized by “French” ceramic assemblages.

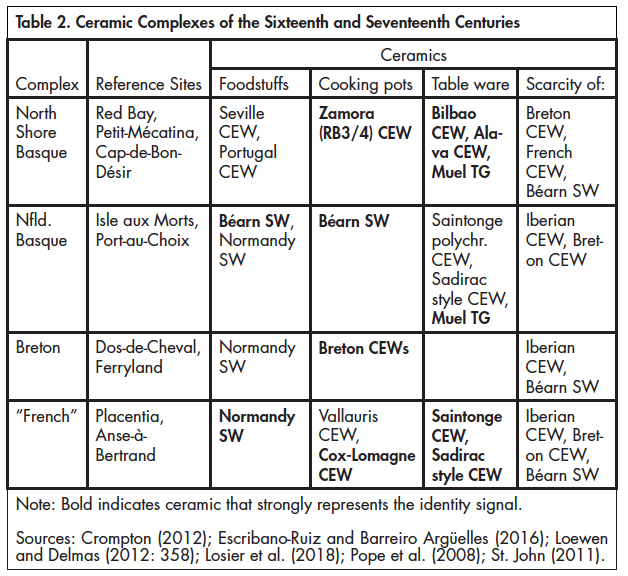

40 Ceramic provenance spectrums are also a line of evidence allowing the development of a more complex discourse regarding sixteenth-and seventeenth-century fishing establishments. Based on their attributes of provenance and function, ceramics found on Basque, Breton, Norman, or “French” sites can be considered as regional identity markers, in complex, evolving ways. While some ceramics were part of the ship’s general outfit, such as containers for food storage, preparation, and service, as well as pharmaceutical products, others belonged to individual crew members or officers, such as majolica or faience, dinner plates or chafing dishes (Dagneau, 2009: 427).Therefore, ceramics are good indicators of where a ship was outfitted, as well as the crew’s regional origin and cultural diversity. As well, by comparing provenances over time among containers with similar functions, related either to the outfit or its crew, we can track regional changes in outfitting and crewing practices (Dieulefet, this volume).

41 Thus far, we have very little archaeological evidence from which to recognize Basque materiality in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon. Only four sites showing a Basque presence are known between Renews and Port-aux-Basques, and none in Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon. Except possibly for Isle aux Morts, their ceramics are hardly diagnostic of a Basque provisioning network. As for French sites, beyond Placentia, Ferryland, and Anse à Bertrand (Saint-Pierre), no sites contain artifacts that can be assigned to any origin in France. Considering the important number of sailors from the European Atlantic facade visiting the region since the sixteenth century, this small database reflects the limited archaeological work in the region.

42 From a theoretical standpoint, we may first suggest that material culture on seventeenth-century Basque sites in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon will fall between two established book-ends, namely, pre-1630 Basque material culture in the northern Gulf of St. Lawrence, and post-1713 Basque-related material in the southern Gulf. As for Breton and Norman material culture, it could resemble material from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sites in the Petit Nord, where crews from Saint-Malo Bay fished intensively. If we can segregate “Basque” and “Breton” material culture in this way, then the remaining “French” materials can be ascribed to ships’ crews or suppliers from the intervening western French coastline, from Bordeaux to Nantes. As we will see, these three ceramic signals are strikingly different.

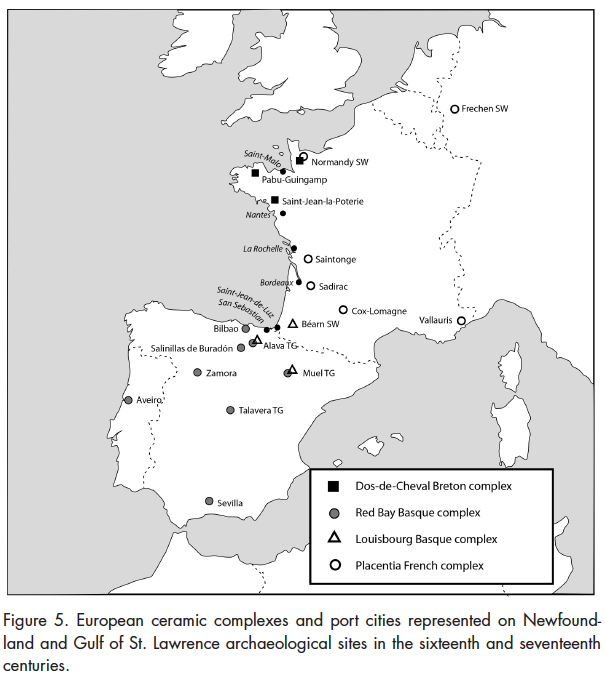

43 Ceramics found on Basque sites along the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Strait of Belle Isle show a preponderance of Iberian provenances. The most significant types that have been identified are “Red Bay 3 and 4” cooking pots that likely come from Zamora, León. They are followed by glazed coarse earthenware from Bilbao and Salinillas de Buradón in the western Basque Country, and by tin-glazed majolica from Muel in Aragon and other centres in Spain or the Basque Country. Some sites have small amounts of Portuguese redware, Andalusian amphorae, and Normandy stone-ware (Loewen and Delmas, 2012: 367; Escribano-Ruiz and Barreiro Argüelles, 2016). This highly diagnostic spectrum of Iberian ceramics is clearest in sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century contexts.

44 On some North Shore sites where a mid- to late seventeenth- century Basque presence is suspected, as at Petit-Mécatina, isolated examples of Saintonge polychrome coarse earthenware enter the ceramic spectrum. Green-glazed Sadirac-style pottery is also found, although it may be from later French occupations of the same sites (Escribano-Ruiz and Barreiro Arguëlles, 2016). This new input from Saintonge and Sadirac, combined with a marked decrease and/or evolution of Iberian types, is suggested on the circa 1640–90 Isle aux Morts shipwreck and could be part of a seventeenth-century Basque pattern (Dieulefet, this volume).

45 In the southern Gulf, a post-1713 Basque ceramic signal has been recognized. It is characterized by Béarn stoneware, found conjointly with a range of French ceramics. Considered to be diagnostic of a Lapurdian presence, Béarn stoneware is abundant at Louisbourg, Canso, and Pabos, in contrast to the northern Gulf where only two shards have been reported, at Port-au-Choix and Red Bay (Chrestien and Dufournier, 1995; Gervais, 2017: 188–89). In addition, new styles of Spanish faience arise in the southern Gulf, possibly retailed by Saint-Jean-de-Luz merchants (Loewen and Delmas, 2012: 385–87). Basques were not the exclusive occupants of southern Gulf fishing sites, nor was their activity limited to fishing. At Pabos their input was perhaps more as fish traders than as migratory fishermen (Nadon, 2004: 21–23). On eighteenth-century sites in the southern Gulf, the limited Basque ceramic signal is overshadowed by a tuned-up “French” signal.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

46 Sites located in the Petit Nord have revealed Breton occupations of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Pope, 2008). Ceramics from these sites are less varied than the ones found on the Basque sites. However, they are easily recognizable and are dominated by the Pabu-Guingamp and Saint-Jean-de-la-Poterie coarse earthenware types, respectively from the Saint-Malo/Saint-Brieuc and Nantes hinterlands (Pope et al., 2008; Pope, 2016a: 59–61, Pope, 2016b: 87–89; St. John, 2011: 185–86). In association with these ceramics, significant quantities of Normandy stoneware are found on Breton sites, possibly shipped via Granville. The Breton ceramic complex is consistent with supply networks set in the hinterlands of port cities that are readily associated with the Petit Nord fishery.

47 In comparison with Basque and Breton sites, archaeological knowledge of Norman occupations is very limited. According to Peter E. Pope (2008: 39), Norman crews were more engaged in offshore “green” cod fishing. Pierre Nadon has also shown that the circa 1730–60 sedentary fishery at Pabos in Gaspésie was supplied through a “Norman” commercial network based in Granville (Nadon, 2004: 21). Even though Granville is near Saint-Malo, typical Breton earthenware is absent at Pabos. Instead, the ceramics that seem to reflect this supply network are Normandy stoneware and coarse earthenware from Beauvais. Interpreting ceramic provenances in Normandy and Brittany remains fraught with unknowns. On migratory fishing sites, Norman and Breton input may occur together as the two regions are next to each other, especially if the occupants are associated with Granville or Saint-Malo. Earthenware from Saint-Jean-la-Poterie in southern Brittany may be associated with outfitters in Nantes, who were active in supplying Placentia and Saint-Pierre (Tanguy, 1956; Landry, this volume).

48 Placentia is the best-known archaeological example of the French presence in southern Newfoundland. Established as a French colony in 1662, this settlement has been abundantly studied through archaeological fieldwork and historical research. However, Placentia was visited since the sixteenth century by Basque fishing crews from Spain and France (Crompton, 2012: 69; de la Morandière, 1962: 220). It is also likely that Norman and Breton crews visited on a regular basis (Landry, 2008: 24–27).

49 Aside from the Basque gravestones located near the St. Luke’s Anglican Church (Egaña Goya, this volume), no clear evidence of a Basque presence has been identified during archaeological excavations in Placentia, although potential roof tiles have provided a tantalizing clue (Fry, 1984; Mills, 2007; Simmonds, 2011). At the Vieux Fort, Crompton recognized coarse earthenware from Saintonge (polychrome style), Brittany (both Saint-Jean-la-Poterie and Pabu-Guingamp styles), Cox-Lomagne, and even Vallauris. Portuguese redware and stoneware from Normandy and Germany were also found (Crompton, 2012: 410–19). This ceramic spectrum is different from typical Basque or Breton assemblages and, aside from the Breton and Portuguese pottery, similar collections can be found in many parts of New France or even in French Guyana at Habitation Picard (Losier, 2016: 84–95).

50 The Placentia ceramic assemblage seems to reflect a commercial network linking France and colonial settlements in North America, and broadens our view of the materiality of cultural diversity in seventeenth-century French Newfoundland. Sites associated with fishing activities in the Petit Nord, on the other hand, are characterized by pottery that conveys the home of the fishermen engaged in migratory fishing, especially Normandy stoneware and Breton coarse earthenware. During the summer of 2017, excavations at Anse à Bertrand, near the town of Saint-Pierre (in Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon), revealed Normandy stoneware together with slipped yellow-glazed Saintonge earthenware and Sadirac-style green-glazed coarse earthenware (Losier, 2017; Losier et al., 2018). The context seems to predate the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. The assemblage seems to echo that of Placentia, in that it is consistent with an interregional French commercial network directed towards supplying a colony, while the Normandy stoneware also correlates with the archipelago’s role as a favoured destination for Breton and Norman fishing crews.

51 This overview suggests what we can expect to find on a fishing site in southern Newfoundland — or perhaps, what we cannot expect to find. The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century sites occupied by Basques from Spain in the Strait of Belle Isle and seventeenth- to nineteenth-century Breton sites in the Petit Nord have very distinctive ceramic signatures, reflecting homogeneous supply networks in Europe and exclusive occupation zones in the New World. As for eighteenth-century Basque material culture in the southern Gulf, it reflects a post-1713 colonial environment that excluded Basques from Spain. Although Basques were in the majority in seventeenth-century southern Newfoundland, they came from both sides of the Franco– Spanish border, shared the landscape with Breton fishermen, and were exposed to the broader “French” supply networks seen at Placentia.

52 In addition to various “scrambling” influences on Basque material culture around Placentia Bay, France’s growing geopolitical influence forced Basques from Spain to outfit part of their fishing voyages in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, thus tuning down the original Iberian signal in Basque material culture. Therefore, while sixteenth-century archaeological contexts in southern Newfoundland may show clear cultural distinctions, by the seventeenth century, growing interrelationships blurred these distinctions, so that we can expect to find a more transnational mix of regional cultural identities and interregional economic relationships.

Towards a New Hermeneutic of Fishing and Colonial Sites

53 From the standpoint of cultural diversity in the North Atlantic, the theatre of southern Newfoundland, including Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, may be perceived in different ways. It was the core area of the Basque fisheries that adapted to ever-changing conditions; it was a transnational territory occupied seasonally or permanently by several cultural groups in their pursuit of marine resources; and it was where the French state established the seat of its Newfoundland colony, and after the Treaty of Paris (1763) Saint-Pierre was the organizational centre of the French North Atlantic fisheries. There is a hermeneutic need to recognize these multiple fields of meaning, not only to understand the region’s archaeology but also to appreciate the strong sense of historical place and identity that permeates today’s society in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon.

54 Our theorization implies, first, a recognition of cultural differences among Breton, Norman, and different Basque fishermen. However, it also recognizes the interaction of different cultural groups, for example, a culturally mixed crew in which a few sailors would bring personal possessions from their home region onto a ship outfitted in a specific port, as well as the state-sponsored colonization process that tends to mute regional specificities. Because of these factors, identification of cultural groups through their material culture is inherently complex. Today’s sense of place and identity also plays a role in archaeological perceptions. In the face of this complexity, archaeologists need to avoid a simplistic binary stance in which “not English” is reduced to “French.”

55 This observation calls for a finer understanding of regional ceramic assemblage. To enhance our knowledge, we focus on the nature of Franco–Iberian ceramic assemblages in and around Newfoundland. On a pragmatic level, analysis of ceramic assemblages must consider not only the presence of certain types but also the absence of others (Table 2). For example, on sixteenth-century Basque sites in the northern Gulf, Iberian ceramics representing the supply networks of ports in Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa are dominant. On these sites, Normandy stoneware is anecdotal or possibly intrusive, while Breton earthenware has so far not been identified. In sharp contrast, in the Petit Nord fishing stations associated with Breton crews, Iberian ceramics are rare or absent. In these cases, the identity signal is strong and easily visible in the archaeological collections.

Display large image of Table 2Note: Bold indicates ceramic that strongly represents the identity signal.

Display large image of Table 2Note: Bold indicates ceramic that strongly represents the identity signal.

56 Peter Pope has broached the idea of a “vernacular” fishing trade that followed “local and traditional” patterns and was not yet subjected to the emerging world economy and the colonial policies of France and England (Pope, 2004: 28–32). Further along the identity spectrum, Charles Dagneau (2009) and Catherine Losier (2016) have explored the transition from regional to national provenances in artifact assemblages from French shipwrecks and colonial sites, reflecting the growing influence of a world economy and national policy. These ideas enrich the regional cultural identities that we see on fishing sites, as well as the integrative mechanisms we see at work in the course of the seventeenth century. We have identified sites that can serve as references for these ideas (Figure 5).

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

57 Following Peter Pope, we suggest that the complex of Basque sites in the northern Gulf, characterized by Red Bay, as well as the Breton sites in the Petit Nord, described at Dos-de-Cheval, are examples of vernacular industries where regional identities are strongly upheld. Brad Loewen and Vincent Delmas (2012: 384–88) have suggested that an eighteenth-century evolution of the Basque archaeological complex, in which a faint “vernacular” signal can still be detected despite the influence of a world economy and French colonial policy, can be seen at Louisbourg and Pabos. At the end of this spectrum, we may suggest the existence of a “French colonial” archaeological complex as represented at Placentia.

58 In the case of seventeenth-century sites, especially in southern Newfoundland, the French colonial project was supported by interregional commercial networks that were not bound to a regional or “vernacular” fishing trade. It is important to distinguish these broad-band commercial networks and their development over time from their narrow-spectrum counterparts in the migratory fisheries. The new geo-political dimension mutes the regional signals that are visible in the collections of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Therefore, we should not expect to find archaeological collections that are solely Breton, Norman, or Basque in southern Newfoundland. Especially, the former Basque archaeological signal will be blurred by trade requirements placed on Basques from Spain through the Saint-Jean-de-Luz admiralty, especially in wartime, by the links that Lapurdian outfitters maintained with suppliers in Béarn and Bordeaux, and by the activity around Placentia Bay of itinerant merchants and fish traders from La Rochelle and Nantes.

59 To recognize identity in archaeological data, researchers must also work with faint noises in the background instead of focusing only on the main signal conveyed by an assemblage. We must consider that fishermen heading for Newfoundland brought personal possessions with them, including ceramics typical of their home ports. Such low-frequency signals can be used to recognize the regional identity that individuals carried in their personal possessions. Therefore, in a material world characterized by a “French” colonial signal, it may be possible to identify a faint but recurring signal of artifacts associated with a Basque presence, for example, Béarn stoneware, Basque or Aragon majolica, or Iberian earthenware.

60 Such an approach to archaeological data will allow a nuanced analysis of cultural diversity within the transnational territory of southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon. This hermeneutic shift recognizes regional and chronological cultural variation within the transatlantic fisheries. Archaeologists have already demonstrated that regional identity is highly visible within sixteenth-century fishing activities. However, this identity did not disappear in the seventeenth century, and cultural diversity is still translated in the data by subtle signals in ceramic assemblages.

Conclusion

61 In building this approach to cultural diversity within the French Atlantic world, we have focused on the importance of the Basque fisheries in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon. Using various historical sources, we have estimated the number of Basque ships that fished in this region and the proportion they represented within the overall Basque transatlantic fleet, as well as within the overall European presence in the study region during the seventeenth century. Other sources have enabled us to reconstruct the network of ports where Basques fished and the seaborne routes they followed, showing a cultural landscape in which archaeology can play a greater role of understanding.

62 The region around Placentia Bay is at the heart of an important Basque cultural landscape, in which the Piarres Detcheverry routier and other sources document more than 30 places known by the Basques in southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon.

63 Contrary to regions such as Labrador and western Newfoundland where only Basques fished, or the Petit Nord where only northern Bretons did so, southern Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon formed a transnational territory where several cultural groups rubbed shoulders. Basques were not the only group to visit the region during the seventeenth century; Breton and Norman fishermen were also present in significant numbers. Moreover, the Plaisance colony and the Saint-Pierre settlement were centres within the region, and they attracted a commercial network that branched out to all of the fishing stations in the region. Considering that these dynamics are still at work today in Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, this region holds one of the longest archaeological records in the French Atlantic, requiring a robust theoretical approach. Our focus on the seventeenth century, which shows both regional identities and integrative mechanisms at work, is also a call for further research in a region where archaeology has an important role to play.