Papers on the Basques in Newfoundland and Labrador in the Seventeenth Century

The Onomastics of Inuit/Iberian Names in Southern Labrador in the Historic Past

Introduction

1 Written records are scarce of the people who lived on the Atlantic coast of south-central Labrador shortly before and following the Treaty of Paris in 1763. In an effort to recreate the demographic picture for the period, the NunatuKavut Community Council sponsored an examination of merchant records, church records, archival sources, oral traditions, and substantiated genealogies. The purpose was to name the people who resided there and were identified (mostly by “outsiders”) as being Inuit. These people were ancestors of the population of Southern Inuit, who are organized today as the NunatuKavut Community Council. The work resulted in a “census” of 641 individuals for the period from 1694 to 1865.

2 Throughout the historical period, Inuit individual identities were a source of confusion for outsiders. Not only was there a problem of phonetics, especially apparent in written sources, but Inuit mobility also disorganized outsiders’ cultural linkage of place and individual identity. Inuit often bore only one name, thwarting outsiders’ habit of organizing individuals into family trees based on patronyms. Annie Meekitjuk Hanson goes beyond these outsiders’ problems to delve into the meaning of names within Inuit culture. 1 Life stories played a role in naming practices, so that individuals acquired names throughout their lives. Adulthood meant that individuals could invent or choose their own name, according to social circumstances. Thus Inuit names can refer to a precise historical context, which makes them time-specific and even event-specific. Over time, some names ceased to evolve and became fossils of a specific time, place, and social context; they became like archaeological deposits that were stratified in time.

3 One group of Inuit names appears to have arisen in the context of contact with Basques from Spain, based on their Spanish or Basque etymologies. Their study has implications for understanding Inuit social structure during the contact period. In this paper the basic research methodology follows just two simple questions: (1) Does the name have a plausible Inuit, Moravian, or English origin? (2) If not, does it have a plausible Basque, Spanish, French, or Portuguese origin?

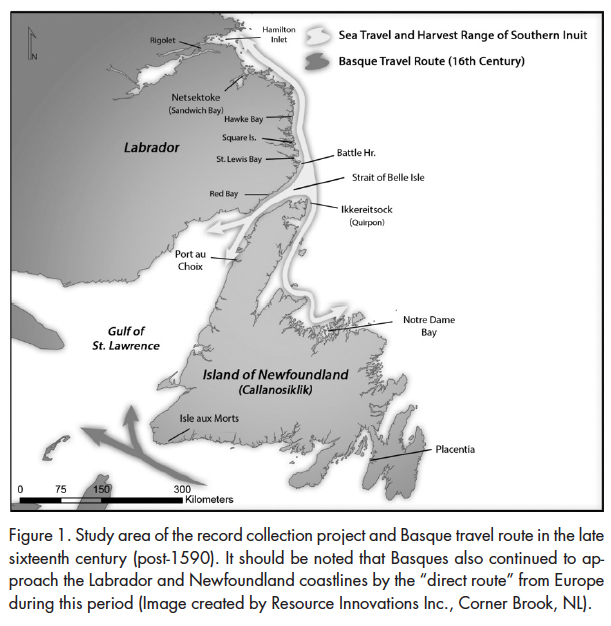

4 Historical Inuit naming practices are known mostly from the outsiders’ point of view. Methodist missionaries to south-central Labrador (south of Hamilton Inlet; see Figure 1) in the early nineteenth century were noticeably upset by Inuit practices around polygamy, in addition to being annoyed by some European men who lived with Inuit “concubines,” as the missionaries called their Inuit women partners. 2 These mixed couples, branded as heathens by the missionaries, were making do on the Labrador landscape outside the realms of Christian and European administrative structures. 3 In the course of their efforts to marry these couples and establish European-style lineages, visiting missionaries Richard Knight in 1825 and George Ellidge in 1827 recorded several very unusual names and found that many Inuit had singular names, rather than binomial, to distinguish themselves from others.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

5 In 1825, Richard Knight married a man named Pompey to Sarah Kouk-souk on 10 August, John Kuniook to Sara Ooing-atshuk on 14 August, and Joseph Hackett to Sara Penni-ook on 14 September.Two years later, George Ellidge married a man named Molina to Sarah Coutebuck on 28 July and then one John Holwell to Joanah Pennyhook on 15 August of that year. 4 It may have surprised the missionaries that four of the five women were named Sara(h), but equally surprising may have been that two of the five Inuit men claimed names with a distinctively Spanish consonance, Pompey and Molina. 5

6 These unpublished records were not found among the marriage records of the Methodist Church (modern-day United Church in Canada) but, for some unknown reason, within a box containing Roman Catholic records for St. John’s (and other areas) at The Rooms Archive in St. John’s. 6 The originals were transcribed by the first author in March 2009 during ongoing research into the history of Labrador’s Southern Inuit. They awakened an unexpected line of inquiry. What was the origin of these borrowed Spanish names? Were there more of them?

The Search for Records

7 Labrador scholarship until recently has conducted an ongoing debate regarding the post-contact Inuit occupation in southern Labrador and the Strait of Belle Isle. 7 It was initially proposed that Inuit from “northern Labrador” (north of Hamilton Inlet) only visited southern Labrador in an effort to obtain and trade in European goods and that Hamilton Inlet was the southern terminus of Thule expansion along the Labrador coast. 8 It now appears, mostly from recent archaeological work, that Inuit occupied southern Labrador on a year-round and permanent basis prior to the assertion of British sovereignty. 9 The descendants of today’s Southern Inuit, represented by NunatuKavut Community Council, are in the process of researching their history both at a community level and at a much broader scale. 10

8 One facet of that research is to compile European records, which has led to the transcription of very diverse church, merchant, and visitor records from the nineteenth century within the study area, from Hamilton Inlet to Quirpon, including the Strait of Belle Isle (see Figure 1), and to gather those records into a single database. In 2010, the database included 593 individual records of Inuit from all known archival sources from 1694 to 1867. 11 Since 2010, 48 more records have been entered into the database, for a total of 641 records from the pre-1867 time period.

9 Clear and suspected Spanish or Iberian names make up a small percentage of that database. Due to language differences between the recorder and the speaker, names often were spelled phonetically or mispronounced, or both. Some tolerance must be allowed for these factors in considering the material. An ongoing consideration during this research is the question of whether these are just “misspelled” Inuit names. Also, it must be borne in mind that Bretons and Normans, occupying the Petit Nord in summer, could have had an influence on Inuit names, although given the outright animosity between Inuit and the French fishers during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this may have been unlikely. 12

Inuit Names and the Naming of People in What Is Now Northern Canada

10 Inuit in Labrador were known by “single word” names in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The first record of a Christian-baptized Inuit with a double name in southern Labrador was at Square Islands in 1805 when William Tory, a transient European merchant, baptized three Inuit identified as Ussungana (the father), Cattarina Ussungana Kokosak, 13 and Nancy Ussungana Kokosak. 14 It was customary for lay persons to baptize children in the absence of a minister or priest in remote locations. It is interesting to note that the probable children took, or were given, surnames of both the mother and the father. From the records available to the authors, these baptisms marked the beginning of surname adoptions among southern Labrador Inuit.

11 The first Inuk to be baptized by Moravians in northern Labrador wasKingminguse, in 1776 at Nain, who was renamed with the single name of Petrus and was the “First Fruit” of the new mission. 15 Formal surnames were not adopted by Inuit in northern Labrador until 1893, and the choice of surnames varied greatly, from typical Inuit patronyms to names of animals, 16 schooner captains, 17 and names of favoured missionaries or music composers. 18

12 Further north in present-day Nunavut, Canada, Inuit did not adopt formal surnames until the 1960s. Prior to this time, the Canadian government issued “dog tags” because visiting people from further south could not understand, or pronounce, Inuit names. 19 The author of a recent article writes that up to the 1960s she was known to the Canadian government as Annie E7-121. To her parents and elders, however, she was “Lutaaq, Pilitaq, Palluq, or Inusiq.” 20 The habit of seemingly random name adoption and the changeability of names during a person’s lifetime present a nightmare for the historical researcher, in both understanding events of the past and following lines of genealogical descent. We may, however, see these names as a form of personal biography framed by social relationships.

13 A person’s name, for Inuit, was not a feature of personal possession or power, but emphasized, above all, the group of kin relations, both living and past. Valerie Alia also describes the use of names in Nunavut: “Inuit have developed one of the deepest and most intricate naming systems in the world. Names are at the heart and soul of Inuit culture. The multilayered naming system is based on sauniq — a powerful form of namesake commemoration that some people describe as a kind of reincarnation.” 21 Names were added during a person’s lifetime and some could be considered as nicknames. In southern Labrador, therefore, Iberian-type names could have been added to existing Inuttitut names, or perhaps Iberian names were incorporated as a result of Iberian/Inuit marriages.

14 In nineteenth-century Labrador, Inuit often chose names of great spiritual significance and meaning, 22 and people were also apt to change their names during a lifetime for various reasons. As the example of Annie Meekijuk Hanson, a.k.a. Annie E7-121, demonstrates, people could have many names at any particular time, depending on the audience and/or their relationships. 23 What may have been more difficult for Inuit was to have a single name throughout their entire lives, given the tendency to change names over the course of a life.

15 Given the foregoing discussion, it is easy to see how Inuit in southern Labrador may have been very open to adopt the names of visiting sailors and fishermen in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries — especially if friendship, in some instances, was the contact mode of the two cultures. 24

Basque and Inuit Commensalism in the Strait of Belle Isle

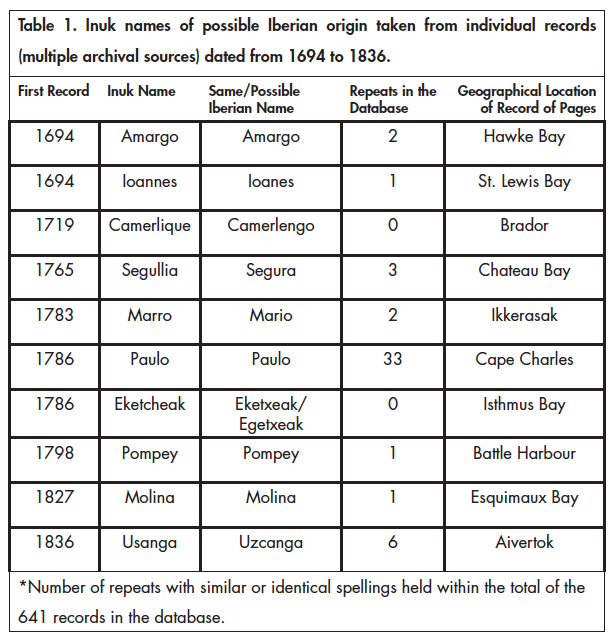

16 Borrowing foreign names was another illustration of Inuit agency and adaptiveness in the changing contact environment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A male Inuk with a name foreign to Inuit etymology and known to Europeans could ostensibly approach Europeans more diplomatically in a trading environment. The “faces” of the Inuit, as we will see in several cases outlined below, were introduced on contact with Europeans, for example, as Capitena Ioannes to Jolliett in 1694, 25 as Capitaine Camerlique to Francois Martel Brougue in 1719, as Capitaine Amargo to Louis Fornel in 1743, and as Segullia (Segura) to Admiral Palliser in the Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1765 (see Table 1). In each of these documented incidents the Inuit individuals with names of European etymology were the spokesmen and negotiators for the Inuit contact group. Taking on a European “title,” usually of rank, was not uncommon in Indigenous/European relations of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, just as the adoption of military and other clothing added prestige to a captain or leader, such as Kullak and Sirmek in the 1780s. For example, the Mi’kmaw negotiator of the 1752 Mi’kmaw–English treaty named himself Major Jean Baptiste Cope. The rank of major was not an appellation historically used by Mi’kmaq, 26 and relatedly, even today the Mi’kmaq use the word “Kepten.” 27

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 117 From Labrador, an Inuit family travelled to Basque Country in 1620, apparently without duress and of their own volition. 28 This occurred at a time when sealskins were being procured by Basque seafarers, such as Antonio de Iturribalzaga, who during his career travelled to Labrador from such ports as Zumaia, Getaria, Donostia (San Sebastián), and Donibane Lohitzun (Saint-Jean-de-Luz). 29 Seal trading in Labrador and the relationships between Basques and Inuit have only recently come under close scrutiny. Archaeological evidence at Red Bay and Seal Islands could suggest Basque–Inuit contact; according to one recent author, “From 1603 to 1635, we find sedentary Basque sealing and conflicts with Inuit. Subsequently, about 1635 to 1690, we find no evidence of Basque sedentary sealing or conflicts with Inuit, but we find references to Basque–Inuit trade in seal oil and skins.” 30

18 Inuit aggression and violence during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when taken from archival accounts, is pervasive, especially involving French nationals, and often has been described as “guerrilla warfare.” 31 However, the relationships between southern Basques (from the Spanish side of the Spain–France border) and Inuit may have been both more complex and a little more peaceful than what it first appears. 32 The questions of whether Inuit were sometimes caught between warring European nations, particularly the two nations that divided the Basque Country (France and Spain), and whether Inuit favoured the Spanish side, certainly require much further research.

19 In general, the relationship between Europeans and Inuit, at any given time in these two centuries, appears acrimonious when seen from the perspective of colonial records. However, as Marianne Stopp has recently surmised:

In uncovering, archaeologically, “re-contextualized” beads, spoons, medallions, and other objects in Inuit households of the period, Stopp points out that these reworked objects “represent cross-cultural negotiation and cultural continuum. At their simplest, the positioning of European objects on the body as clothing decoration ‘spoke’ to Inuit and Europeans alike as intercultural signalling.” 34

20 In this nuanced framework of trade relationships 35 and cultural sharing, the borrowing of Spanish or Basque names by Inuit would follow a similar pattern of resilience and adaptation. 36 Inuit practices of name adoptions were very open and robust, at the very least, into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Valerie Alia considered names to be at the very centre of Inuit culture. 37 If there were certain favoured Basque traders and fishermen, it is understandable that their names would become adopted by Inuit, or, in the alternative, that Iberian sailors simply “called” Inuit by these names.

21 Similarly, beginning in the mid- to late nineteenth century and continuing into the twentieth, Inuit males would sometimes change their names to be “English” in a cross-cultural environment. Inuit, in this period of European presence in southern Labrador, are likely to have used the process of “racial passing” because of stigmatisms. 38 That would be no different in a situation where a southern Basque trader came to trade and you, an Inuk, were introduced with a Basque name; no doubt, the wheels of commerce would be greased more readily.

Discussion

22 One outstanding example of these records and the eclectic admixture of Inuit names is illustrated in the Slade account books from 1798 at Battle Harbour, listing purchases from Inuit by that English trading firm (see Figure 2). 39 First on the list is a person named Pompey, who on 18 July purchased a gun and 25 gun flints in exchange for 70 gallons of seal oil and three pickled sealskins. 40 Of the other 10 names on the list, five appear to have an Inuit origin (Aglucock, Shilmuck, Occabieuke, Teeweockinar, and Eteeweooke) and three of them clearly have English names (young Jack, old Jack, and old George). The remaining two names are questionable as to whether or not they have a Basque/Iberian origin (Cognavagner and Mawcoo). Since these names are held within the Slade ledger of the generalized “Indian Account” some of them could also indicate Montagnais (Innu) people or other ethnicities, requiring further research.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

23 Within the larger record list previously mentioned (641 records), 10 names may be Basque/Iberian (Table 1). 41 The famous French explorer, Louis Jolliet, 42 in 1694, first encountered two Inuit men in Labrador at 52° 30’ in the vicinity of St. Lewis Bay, Labrador. Kamicterineac and Capitena Ioanniswere described as friendly and approached Jolliet with the words “Ahé, thou, tcharacou.” Linguists are divided as to the etymology of the word “tcharacou,” with Louis-Jacques Dorais suggesting the term to derive from the Inuttitut “tuksiarakku,” meaning “because I implore it,” and Peter Bakker suggesting the derivation to be from the Basque word “txarrako,” meaning “of bad” or possibly “war.” 43 It is equally interesting that by 1742 the Inuit greeting to outsiders, such as Charles LeCour, was “Bons camaras, tous camaras,” meaning (in broken French) “good friends, all friends.” 44 Possibly another group of Inuit greeted Louis Fornel the following year at “baye de Meniques” (St. Michaels Bay 45 ) with “Tout Camara Troquo balena, non Characo,” meaning “you (are) comrade, let us trade whale, not war/bad.” 46 It becomes apparent that Inuit who were willing to trade may have been using language appropriate for the audience, whether it was Basque (Euskara), Spanish, or French. By 1771, in a collection of Inuit terms by William Richardson of the Royal Navy, a group of Inuit used the term “Ekingootigac,” 47 with no very apparent Inuttitut etymology 48 and translated by Richardson as meaning “all friends.” It is interesting to note that the Basque word for “all” is “guztiak,” bearing a close relationship with the latter part of the word. Peter Bakker attributes the word “ikinngut” as the Greenlandic Inuktitut word meaning “friend” (Peter Bakker, personal communication). 49

24 To live and trade in a space that was increasingly multicultural and to adapt to that world, both linguistically and through personal expressions and attire, is a hallmark of Inuit persistence and resilience. 50 The adoption of Basque or Spanish names by Inuit within that milieu of sharing a landscape and trading resources should be of no surprise. It should also be noted that name adoptions by Inuit occurred irrespective of whether that name was previously used as a forename or a surname. 51

25 The Methodist records also list a “Johanna” and two other “Sarahs” (total of four), which may be further evidence of Iberian connections within the Labrador landscape. “Johanna” can be considered the female form of “Ioannes,” 52 while “Sara” is a Basque family name as well as the name of a town in Lapurdi. 53 The name “Sara” is also known to come from other Iberian/European areas. “Sara/Sarah” is prevalent in the early records, with 13 entries, and the name may predate any English presence on that coast, as in the case of Sarah Shunnock (1757–1867), purported to be 110 years old at her death. 54 Being a Biblical Christian name, “Sara(h)” has its roots in either Iberian, French, or English sources. Since the name predates an English presence and no other “French” names are present in the records perhaps because of animosities with French nationals, 55 the only reasonable source for the name is Iberian.

26 One of the Basque gravestones at Placentia, Newfoundland, located on the seventeenth-century route to southern Labrador and a major port of entry for Basques to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, 56 bears the name of “Ioannes Sara”; both these names are present in the Inuit records. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Basques in Spain adopted Spanish first names under the influence of the Church. Basques in France transformed French-derived first names in systematic ways, notably by adding –es at the end, as in Joannes or Piarres (Miren Egaña Goya, this volume).

Capitena Ioannes

27 This name was recorded by Jolliet in 1694, describing an Inuk in the area of what may be St. Lewis Bay, Labrador. 57 It is interesting in that “Capitán” is the Spanish word for “Captain,” the French word being “Capitaine” and the Basque turning this into “Kapitaina” or sometimes “Kapitena” in northern Basque Country, following directly on the French, while “Ioannes” is a typical Basque first name from the French part of the Basque Country. It should also be noted that four of the six Basque gravestones at Placentia, from 1676 to 1694, are inscribed with the name Ioannes or Joanes. The gravestones attest to the contemporary Basque usage of this name. 58

28 The name “Johannes” (male) and the female form, “Johanna,” persisted in the Inuit name lexicon throughout Labrador from earliest contact times to the present day, and both are “quite common” and “prevalent” in Labrador genealogies, according to Patricia Way, a prominent Labrador genealogist. 59

29 European name adoptions by the Inuit in the missionary period in Labrador, beginning in 1776 with the first baptisms, were highly influenced by the Moravians, who chose names from a “lot” put forward by various missionaries. 60 The name “Johannes,” for example, could very well have been adopted as the name of a respected missionary, such as Johann Schneider or Johann Ludwig Beck. Inuit were also familiar with the name “Johann” since the time of explorations by a Moravian explorer, Johann Christian Erhardt, who perished in Labrador in 1752. 61 However, Jolliet encountered “Capitena Ioannes” 82 years prior to Moravians renaming Inuit in Labrador. The equivalent of “Ioannes” in English is “John” or “Jonathan.” In the years following British assertions of sovereignty in Labrador (after the Treaty of Paris in 1763), the adoption of the English form of “John” is likely, but does not diminish the possibility of an origin from the Iberian form of “Ioannes.”

Capitaine Amargo

30 Records of explorations to the Labrador coast continued after Jolliet with the journal of Louis Fornel in 1743. 62 In the vicinity of Hawke Bay (latitude 53°02’ N), Fornel encountered the Inuk named Capitaine Amargo, with whom he traded and named the bay in his honour. 63 This name repeats the use of “Captain,” this time in French, and adds a Spanish-looking individual name. The word “amargo” means “bitter” in Spanish. Although it is tempting to see an Iberian version of the first name “Amerigo,” as in Amerigo Vespucci who has been immortalized with continents in his name, 64 it is equally important to consider that this name may be a misspelled Inuk name “Amaqqut” or “Amaruq.” 65 Possible variations of this name, such as the records of Mago (1783) and Mawcoo (1798), may be further evidence for an Iberian source corrupted by dropping the initial “A.”

Capitaine Camerlique

31 Recorded in 1719 in the Brouague Correspondence from Brador, in the Strait of Belle Isle, the name “Camerlique” attracts attention for its probable European origin. In this correspondence written for his superiors in France by the French colonial commander with Basque origins, François Martel de Brouague, Capitaine Camerlique is described as “the most considerable of their [the Esquimaux] chiefs, although he is not from their nation, and judging by the way he talked, he seems to come from Europe.” 66 It is then highly probable that Camerlique was an adopted European, or the son of an Inuit/European marriage.

32 On the other hand, the name “Camerlique” recalls the title “Camerlengo,” or “Camerlingue,” in French. The Camerlengo is the highest administrative office in the Roman papacy, held by someone with the rank of cardinal. He is historically in charge of the material property and revenues of St. Peter’s.

33 From a linguistic standpoint, we could find an explanation to this –ique ending. In the French colonial mindset, the –ique ending is pejorative (as in “cacique” for a powerless Indigenous chief). Thus, if this change to “camerlique” is of Brouague’s making, it could be that he was mocking the status of the mixed-ancestry warrior captain in this letter written to his superiors in France.

34 Considering that Inuit personal names stem from social roles and can vary over time, “Camerlique” may be a social title inherited from his warrior talents, as well as his knowledge of the Europeans or his role in making contact, trading, etc. He appears in Brouague’s account of his standoff with an Inuit force over the fate of an Inuk girl named Acoutsina, a hostage in the Brouague household. Acoutsina’s name also may reflect her social role in this account, as a captive servant. 67 Camerlique recommended killing Acoutsina and the Brouague household, but he was overridden by the Inuit chief, who was a relative of Acoutsina, allowing French colonial power in Labrador to survive the crisis. 68 When Brouague recomposed the events for his official correspondence, he may have belittled the chief ’s “Camerlengue” by naming him “Camerlique.”

Marro

35 “Marro” may be an easy spelling for the Iberian name of Mario, which was first recorded in the St. Michael’s Bay area of Labrador and recorded in the Hopedale records. 69 In Labrador a “Marro” is recorded as moving to Ikkerasak, in the vicinity of Occasional Harbour at St. Michael’s Bay, in 1783. 70 This particular person was renamed Nathanel by a Moravian missionary, Brother Johann Schneider, in 1784. Whether this name is related to the surnames of Maggo or Mucko (present in today’s population) is unknown. The recording of names was entirely at the discretionary ear and pen of the recorders, who were mostly itinerant clergy as well as scattered merchants after 1765.

36 Recent genealogists have suggested that the surname of “Maggo” or “Mucko” as recorded among Inuit reflected some possible association with the French trader, Pierre Marcoux, who began trading in northern Labrador by 1784. 71 However, prior to Pierre Marcoux, the Hopedale Diaries and Records yield a “Mago” [Magok] who, on 18 October 1783, claimed that he had met the Moravian missionary Jens Haven at Quirpon(g) in Newfoundland in 1764, long before the French trader Marcoux arrived in Labrador. 72 In the Hopedale records, both a “Mago” and a “Marro” are recorded as Kippinguk’s brother. We do not know if they are one and the same person or if, in fact, the “Capitaine Amargo” is the “Mago” or the “Marro” with the name misspelled, requiring further research to determine whether this name was given by the Moravians or if it has another origin.

Usanga

37 The spelling of “Usanga” was used to name an Inuk man (Joseph Usanga) born at Netsektok, Sandwich Bay, in 1836. 73 Whether this is an Inuit name or was adopted from another source needs further research. In the Basque Country, a very similar family name, Uzcanga, can be gleaned from the eighteenth-century writings of Don Pedro Aldazabel 74 concerning Basque sailors who went to Labrador. “Uzcanga” would in fact be pronounced “Usanga.” In old Spanish spelling (for Uzcanga), the role of “z” or “s” was to replace the cedilla under the “c,” so as to make the “c” soft. 75 This name may have been spelled as “Ussungana” in some of the Labrador records.

38 The name “Usanga” is based on the Basque word “uso,” meaning dove, while the locative suffix -aga or -anga designates the place associated with doves. This may have been a sailor’s name. Since Basque family names are very often created from that of an ancestral house or farmstead, “Usaga” or “Usanga” meant “the place of the dove.” Usanga may have been a sailor’s name, or Basque sailors may have associated an Inuit family with a place where there were seabirds reminiscent of doves. In her article in this issue, Miren Egaña Goya describes the use of “uso” on a Basque tombstone in Placentia.

Paulo

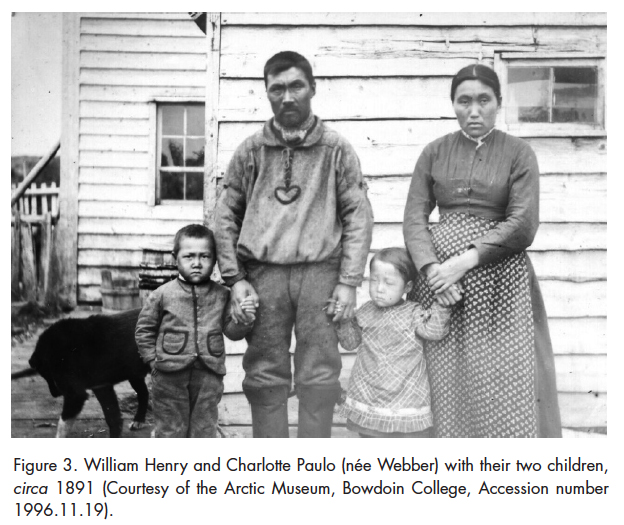

39 First recorded in the Hopedale Diaries (Herrnhut collections) and dated at 1786, 76 this primarily Iberian name is perhaps the most widespread and common in the nineteenth-century records (33 entries). The Spanish and Portuguese form of this name (Paulo) is common today on the Iberian Peninsula. The Paulo family has survived from at least the eighteenth century in Labrador, with the last person bearing the Paulo surname passing away in 2013. 77 However, the name lives on in the area where a great-grandson of Thomas Paulo, Keith Poole, has named his contemporary business Paulo Ventures, and there are presently 23 residents of St. Lewis, Labrador, out of a total of 174 in the town, who are Paulo descendants. 78

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

40 The Paulo surname, spelled phonetically by eighteenth-century recorders in southern Labrador, was written down as “Pualo” by Moravian missionaries. The name survived in northern Labrador at least until 1894, when a census showed four people bearing the name. 79 As in southern Labrador, this Iberian surname no longer exists in the living population.

41 The first recording of the name is by William Richardson in 1771 when it was recorded as “Peu[v]allo,” and it appears in the records 32 more times up to 1867. In the nineteenth century, the Paulo family lived primarily at St. Francis Harbour and Fox Harbour (present-day St. Lewis).

Eketcheak

42 Recorded in 1786 in Isthmus Bay by George Cartwright, 80 a Basque origin of “Eketcheak” is plausible not only phonetically, but also syntactically and culturally. Central to this hypothesis is “etche” in the middle of the name, a frequent element of Basque family names meaning “house” (“etxe”). One of the most common traits of Basque family names is that they refer to the house that the family is from, and thus, often include the word “house” in them. A well-known example is “Etcheverry” (“Etxeberri” in modern spelling), meaning “new house.” Moreover, in Basque the plural is indicated by the suffix “-ak,” as in “etxeak” (houses). As for the “ek-” at the beginning of the name, it may come from the Basque “eki” (east) or “hego” (south), thus giving these “houses” a location, which is also common in Basque, in the sense that it gives a specific character to the house where a family originates, thus building a family name. So here, a Basque origin for “Eketcheak” is entirely plausible from linguistic and cultural standpoints.

Pompey

43 First recorded in 1798 at Battle Harbour in the “Indian Account” (see Figure 2), this surname also no longer exists in Labrador. In addition to the several historic records, the name “Pompey” is maintained in both living memories of elders and in today’s toponymy. “Old Pompey” was said to have committed certain serious offences in one of the communities and was banished to an island in the autumn. 81 He is said to have died there during the winter.

44 Two islands in Labrador retain the name of “Pompey.” West Pompey Island is located just east of Rigolet in Groswater Bay. At Sandwich Bay near present-day Cartwright, Pompey Island is a small island approximately 145 feet in height at its summit. Nearly two miles from Pompey Island is Pompey Rock, which breaks at low water. 82 Even though only two records have been found of this Iberian name, its legacy lives on in the geography of Labrador. Whether one of these islands is the exact location for the banishment and demise of “Old Pompey” is unknown.

Segullia

45 This name was first recorded as “Secullia” by Jens Haven, the principal founder of the Moravian missions in Labrador, at Quirpon in 1764. In 1765 an Inuk named Segullia, described as an Angekok (leader), was greeted by the English Governor Palliser and acted as a spokesperson for 300 Inuit gathered at the peace treaty between the British and the Inuit at Chateau Bay in southern Labrador. 83 Brother Drachardt, another Moravian missionary, in his diaries, written in Inuttitut, records the name as “Sekùliak.” 84

46 The Basque surname “Segura,” the name of a prominent family of outfitters and whalers in the port of Orio, is found in several sixteenth-century documents related to the Labrador fisheries. 85

Molina

47 The only record to date in southern Labrador — from the Methodist records — is for a man named “Molina,” who in 1827 married Sara Couteback (see Hickson, 1824). However, previously, in northern Labrador a woman named “Malina” was baptized with the allotted name of Benigna in 1776. This date and the fact that the person was “renamed” supports the theory that this particular Iberian name was not brought to Labrador by Moravian missionaries. 86 “Molina” is the Spanish word for mill.

Conclusions

48 Historical Basque documents from the sixteenth century yield a number of names discussed in this essay, such as Segura, Joannes, Paulo, and Usanga. 87 These legal trade documents show the names of the various captains and vessel owners. However, we have few records of the common sailors who made up the vast majority of fishermen, whalers, and sealers visiting Labrador from the Iberian Peninsula.

49 Southern Labrador Inuit, like people the world over and throughout time, often named their children after a favoured person in their midst. There is presently a generation of middle-aged men in North America, for example, bearing the name of “Elvis,” after the popular rock and roll star of the 1950s and 1960s. The authors propose that in this vein and perhaps with contact period diplomacy in mind, Southern Inuit borrowed Basque and Spanish names from people with whom they were familiar through friendly trade and otherwise in the seventeenth and perhaps sixteenth centuries. At various times, Inuit may have considered themselves international players in siding with the Spanish nationals and warring with their common enemies, the French nationals.

50 Inuit were adapting to a new world within their territory, invaded by competing seasonal European fishermen and sealers. Their history of organizational skills was demonstrated through efficient and speedy travel 88 in organizing multi-functional operations such as whale hunting 89 and through their efficient and often successful guerrilla warfare tactics. 90 Their hierarchical 91 and accepting culture allowed for flexible adaptations when necessary, such as title and name adoptions for their contact negotiators.

51 The complexities of Inuit–European relationships are yet to be fully explored archaeologically in southern Labrador, especially on the Atlantic coast where the intricate mosaic of bays, coves, and tickles, with a couple of exceptions, has only been very briefly surveyed south of Sandwich Bay. 92 It is surprising that an area such as the southern Labrador coast, which in the beginning years of European explorations acted as a funnel for explorers and entrepreneurs to what they considered to be the “New World,” has had so little scholarly attention. The paucity of historical records from the period inhibits the development of a clear picture of these past events.

52 In surviving records (mostly from the eighteenth century), a small percentage of Inuit names (about 3 per cent) could be of Basque or other Iberian origin, which may give a clue to the Inuit–European contact environment in the period. From whence those names came and the particular circumstances surrounding their adoption by the Inuit is fertile ground for students of southern Labrador history. Just exactly how the original Mr. Molina, Mr. Paulo, or Mr. Pompey, and a number of other Inuit, obtained their names remains a mystery.

The authors would like to thank Susan Kaplan, who first informed Greg Mitchell that some Inuit names from Labrador had a “Basque” sound and may warrant further inquiry. We also thank Hans Rollmann for his kind permission to use some of his unpublished research and Eva Luther for her information on the Paulo family. Louis-Jacques Dorais’s comments on the entire record list were invaluable in examining Inuit origins, and kindest regards to Pieter Jan Bakker for taking the time to review and make suggestions on our paper. We would also like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments. The project may never have gone ahead without the encouragement and a great deal of help from Brad Loewen. Thank you all.