Papers on the Basques in Newfoundland and Labrador in the Seventeenth Century

The Basque Seal Trade with Labrador in the Seventeenth Century

1 For 250 years, from the sixteenth century to the eighteenth century, about 3,000 Basque sailors on average spent the summer in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, to fish for cod, hunt whales, trade pelts, and engage in the fish trade with sedentary communities. Between 70 per cent and 90 per cent of crews came to fish — a proportion that varied mainly because other Basque activities rose and fell, as a function of the historical conditions they depended on. 1 Among these secondary activities, the seal hunt is perhaps the least known. In the Basque sources we have studied, sealing and the seal economy are documented from 1603 to 1661. Especially, the port registers of Deba and Mutriku, in western Gipuzkoa, reveal several steps in the transatlantic seal trade, from the outfitting of voyages to Labrador to the fabrication of specialized footwear for sailors. We also see crews from Donostia–San Sebastián and Saint-Jean-de-Luz in search of seal in Labrador and the Magdalene Islands, while Gipuzkoan tanners exported their finished sealskins as far afield as Lisbon, in Portugal. The Basque seal trade may have included the Labrador Inuit, and if so it would provide a context for the oral tradition, still much alive in the Basque Country, of relations between Basques and Inuit in the seventeenth century. 2 The Basque seal trade sheds new light on the history of the North Shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence during the century before its integration into New France.

2 Several French colonial authors, from Samuel de Champlain onward, mention Basque or “Spanish” fishers and whalers in the northeast Gulf of St. Lawrence in the seventeenth century. 3 Spanish-language archives confirm that the Basques never abandoned Labrador in the seventeenth century. 4 They show that Basque whalers and cod fishers frequented both shores of Gran Baya, their name for the northeast part of the Gulf between Newfoundland and Quebec’s Lower North Shore, from the sixteenth century through to the eighteenth century. As well, they reveal that several captains traded with the Inuit to obtain sealskins or some even wintered in the country to hunt seal themselves. The Gipuzkoa notarial archives from the 1610s to 1630s show the sealing activities of a Mutriku captain, Antonio de Iturribalzaga, while the Mutriku municipal archives shed light on the Basque sealskin economy, particularly on the tanners and shoemakers who worked the skins, and on the sale of sealskins to other places in the Iberian Peninsula. While our research covers only the port of Mutriku in the first half of the century, related sources indicate that Labrador seal oil and skins arrived in several Basque ports throughout the seventeenth century.5

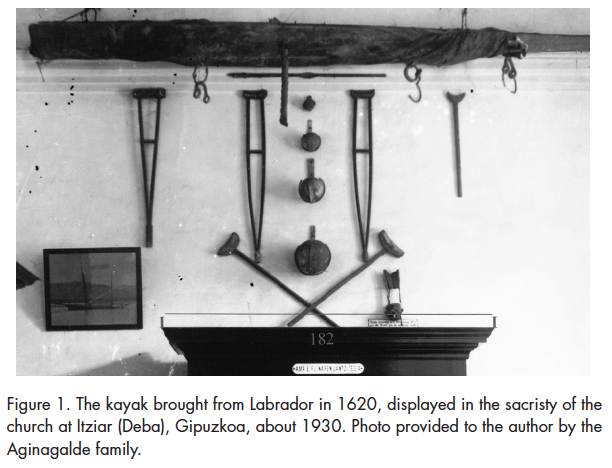

3 For over 4,000 years, people have exploited the seal around the Gulf of St. Lawrence. 6 In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the seal hunt left many historical and archaeological traces. 7 While the role of the Basques in the Labrador seal economy has received little scholarly attention, 8 in the Basque Country the link that the seal represented with Labrador and the Inuit has deep roots in the collective memory, due to a kayak that was preserved for 350 years in the church of Itziar, near the Gipuzkoan port of Deba. In 1620, Captain Francisco de Sorarte from Deba brought the kayak from Labrador, as well as a young Inuit family of two parents and a child. The infant died soon after the family’s arrival, while the father was unhappy in Europe and returned to Labrador. The mother, however, adapted to life in Deba, where she spent the rest of her life working as a domestic in the household of a Deba merchant family. As for the kayak, at some time it was cut and amputated of about a third of its length, so it could be hung on the wall of the small sacristy. It is visible in this condition in an old photograph from about 1930 (Figure 1). It stayed in the church until about 1970, when a local priest decided to throw it out. The memory of the Inuit family and its “Galerilla pequena, o Canoa,” was still alive in 1767 in the Aldazabal family with whom the mother had lived, while a pamphlet on the Itziar church commemorated the Inuit family in 1927. 9 Our discovery, in early 2012, of the photograph of the kayak was recently reported by the newspaper El Diario Vasco,10 thus renewing the memory of this tangible link between the Basques and the Inuit from the seventeenth century.11

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

4 We may associate this compelling story with notarial acts, in the Histórico de Protocolos de Gipuzkoa (AHPG–GPAH) in Oñati, that show the Basque seal hunt in Labrador and Gran Baya. Some of these documents have been published or commented by historians Selma Huxley Barkham and especially José Antonio Azpiazu, without, however, intimating the real extent of the Labrador seal trade.12 We were surprised therefore to learn, while consulting records for a seemingly unrelated project on mills on the Basque coast, that a mill in Mutriku also ground tree bark for its tannin to be used for curing hides and, a few records later, that these hides included sealskins from Labrador. 13 This discovery comes from the Archivo Municipal de Mutriku (AMM), where we examined the port register from 1582 to 1640. Eventually, we were able to reconstitute the sealskin chaine opératoire, including the acquisition of sealskins in Labrador, their tanning, their transformation into specialized footwear that Basque sailors wore during their Labrador sojourns, and the resale of hides to other places in the Iberian Peninsula.

Seal-hunting Voyages

5 Other records from the Gipuzkoa notarial archives reveal the wide activities of Antonio de Iturribalzaga, a captain and outfitter from Mutriku, who was active in the Labrador seal trade in the 1620s and 1630s. Born about 1592 into a family of sailors, outfitters, and shipbuilders, 14 Iturribalzaga differed from other transatlantic fishers of his time because of his frequent visits to the notary. From 1613 to 1635, his name appears in at least 15 acts (see Appendix 1). 15 Apart from his penchant for notaries, his career was likely typical of many transatlantic captains. From the age of 21, he invested in cod-fishing voyages to Terranova. Over the years, he sailed to Terranova in ships owned by outfitters in Zumaia, Getaria, Donostia–San Sebastián, and Donibane Lohitzun (Saint-Jean-de-Luz), either as captain or dueño (who represented the cargo owners). In 1620 he had his own ship built, the Nuestra Señora de la Concepcion, which he put on the Seville route for two years before converting it for the Terranova cod fishery. He continued to work as a captain or dueño on other ships, travelling in convoy and typically describing his destination as “la canal de la Gran Baya.” Sometimes he gave a more precise destination. Thus we find him sealing in 1624 and 1626 at Los Hornos (St. Modeste) in the Strait of Belle Isle, and in June 1632 he stopped at Isla de San Jorge (St. George Island) and at Ferrol in western Newfoundland, en route to the Straits region.16 In our last news of him, in the summer of 1635, he was “absent in Terranova” when his procurers sold 280 sealskins in his name to a Mutriku shoemaker.17

6 Over these 23 years, Iturribalzaga stated four times that he was going to hunt seal, or perros marinos. In 1624, as captain of the San Sebastián outfitted to take “ballenas, perros marinos y bacallao,” he was headed for Gran Baya and specifically to “al puerto que llaman de las Ornos,” that is The Ovens (St. Modeste, Labrador). 18 Two years later, he returned to “al puerto de los Ornos a pesca de ballenas, perros marinos y bacallao.” 19 In 1629, his ship the San Pedro was in the Mutriku roads ready to sail for Gran Baya, where he intended to hunt whale and seals. 20 On 11 April 1630, in the role of master and captain of the San Pedro, Iturribalzaga again set sail for Gran Baya, “a la pesca de ballenas y perros marinos.” 21

7 While these are the only explicit mentions of the Labrador seal hunt that we have found in Basque archives, other documents seem to hint at this activity indirectly. Hunting the harp seal on its migration through the Strait of Belle Isle implied wintering in the country. Harp sealing takes place in early spring and late fall. Although the fall hunt could be squeezed in before winter freeze-up, the spring hunt occurred very early and required overwintering in Labrador. This schedule explains the documentary evidence that Basques occasionally overwintered.

8 Sealing thus may be the reason why crewmen from Donostia–San Sebastián were asked by their captain to pass the winter of 1603–04 at Red Bay, and possibly again the following year. 22 Another indirect sign of the seal hunt may be references to conflicts with the Inuit, whose subsistence depended on the same resource. In 1603, a group of Inuit confronted and slew Domingo de Alascoaga, the captain and harpooner on the Maria of Saint-Vincent de Ziburu (Ciboure). 23 In 1626, other Inuit killed captain Pedro de Echevarria, his sons, and other members of his crew from Donostia–San Sebastián. 24 Such tragic incidents led Lope Mártinez de Isasti, a priest at Lezo in the port of Pasaia (Pasajes), to write in 1625 that the Inuit killed and ate Basque sailors. 25 While conflicts between Inuit and Basques arose for a number of reasons, it has been argued that they resulted from competition over access to seals and the best spots for capturing the harp seal during its migration, at narrow “tickles” between islets and the coast. 26

9 The added risks of overwintering and potential conflict with the Inuit may explain why ordinary sailors put their home affairs into order before embarking for the Labrador seal hunt. 27 They also suggest that the Basques had strong incentives to minimize overwintering. Indeed, avoiding the cost and risk of wintering may also explain why we find Iturribalzaga sailing to the Strait of Belle Isle via western Newfoundland in June 1632, that is, so he could intercept migrating bands of harp seal as they followed the retreating pack ice through the Strait, from the Gulf to the Atlantic. These direct and indirect references to the seal hunt show the period from 1600 to 1635 as one of extensive trial-and-error development of the Basque seal trade in the Strait of Belle Isle.

Basque Leather Trades and Sealskins

10 We may now trace the link between the Labrador sealing voyages and the leather trade in the Basque Country. We should note that the path that led us to the Basque seal trade was anything but direct. Since 2010, we have studied the mills that were located in the port of Mutriku from the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries. As noted above, these mills crushed tree bark to extract the tannin, and this tannin was used to macerate the hemp that was transformed into rope for ships. Records showing the origin of the hemp in the Ebro Valley 28 also revealed its destination in the mills, demolished long ago, within the tight space around the port. 29 As our research continued, we saw that the mills also crushed bark for local tanneries (adoberías or curtiderías). Finally, as this research expanded, we encountered mentions of sealskins from Canada among the shipments of hides entering the tanneries and leaving them to various destinations. While certainly not the most direct route, this archival trail led us to discover the economic motor underlying the seal hunt that had remained hidden from researchers focused directly on the transatlantic fisheries. The junction between our mills and the transatlantic fisheries turned out to be the career of Antonio de Iturribalzaga.

11 The setting for Iturribalzaga’s career was Mutriku, a secondary port wedged into a notch in the coastal cliff of Gipuzkoa so as to provide a secure anchorage for large sailing ships. Its economic function complemented that of Deba, a commercial town and port located three kilometres to the east on a river route leading to inland Iberia, but limited to boats and smaller ships because of silting. As a deepwater port, but without access to inland routes, Mutriku had a complementary relation with Deba. While Deba was a prosperous merchant community connected to Castille and the Ebro Valley, Mutriku was a harder town of sailors, ship carpenters, and port industries. Both ports, however, had a leather industry.

12 In Deba, we find an adobería as early as 1412 in the port area of Amillaga. By the seventeenth century, the tanneries extended along the river upstream of the town. In Mutriku, the municipal archives contain a copy of a royal ordinance from 1503 regarding leather workers (peleteros) for all of Spain. 30 Because the town kept a copy of the ordinance, we may deduce the local presence of leather trades. A 1511 Gipuzkoa regulation stipulated that all shoemakers (zapateros) in the province were to have official standing and have their products inspected to ensure that each item was “made of well tanned leather, well sewn and assembled.” The regulation stated the need for good shoes in this “mountainous and coastal province where it rains much of the time.” 31 The first explicit reference to an adobería in Mutriku is in a 1549 dowry of “the land and walnut stands of the tannery.” 32 In 1572, the Augustine monastery received a donation of walnut stands used for tanning, in addition to lands planted in vines, orchards, forests, chestnuts, osiers, and fruit trees. 33 The walnut trees cultivated for their tannin thus were part of a wooded landscape that was managed for food production and port industries. Four years later the town prohibited shoemakers from washing leather in the communal brook, calling instead for them to use the basins of customary tanneries (teneryas acostunbradas). 34 This document reflects the typical frictions over the use of streams and rivers. The public brook in Mutriku powered several mills, whose reservoirs likely contained edible fish that were menaced by the toxic residues of tanning. In these ways, municipal management of land and professions provides information on local leather trades.

13 Other documents shed light on the operations of an adobería or curtidería. A 1503 royal ordinance prohibited tanning between the first of November and the following February, perhaps to prevent the accidental overflow of contaminated water during winter floods. It required tanners to have their equipment inspected, including “the basin, flour, salt, and other equipment.” 35 In the early seventeenth century, the Mutriku tannery belonged to Simon and Pedro Iturriza, father and son in a prominent local family. 36 It was located on the wharf, as indicated by a 1636 gift of timbers from the mayor to “make the piles of the mole [pier] and the tanneries.” 37 The town reconfigured its military defences in 1667 to include the tannery, but in 1682 the tannery’s battery was moved to higher ground. 38 Like the mills and the walnut stands, the tanneries were in the hands of powerful families who ran municipal affairs.

14 In this context of coastal leather trades we find references to the arrival of the skins of perros marinos (sea dogs, literally). Our first discovery was a 1635 act for the sale of various skins, including sealskins, to a Mutriku shoemaker (see Appendix 2). 39 The buyer, a Mutriku shoemaker (official de azer calçado) named Martin de Larralde, promised to pay Maria Nicolas de Armunoeta, also of Mutriku, 100 ducados for 46 cow and ox skins that were in Getaria, as well as 10 other cow skins, 18 goat skins, and 40 skins of perros marinos that were already being tanned in Larralde’s casa and in the Mutriku adoberías. To guarantee the purchase, Larralde mortgaged two basins (tinas) for tanning hides that were in his house.

15 The same day, in a separate transaction, Larralde also bought 280 sealskins from Antonio de Iturribalzaga, in exchange for footwear and other clothing items to be used in the captain’s upcoming Terranova voyage. 40 We may ask whether the sealskins were used to make watertight footwear 41 or possibly footwear adapted for winter conditions. By way of comparison, in the eighteenth century, outfitters supplied Canadian sealers in Labrador with “Indigenous footwear” (souliers de Sauvage) made of sealskin, or provided them with skins from the previous year so as to make their own footwear. 42 It has been suggested that traditional Inuit skills and methods for making sealskin kamiks were transmitted to Basque shoemakers in the early seventeenth century. 43 Was the Inuit couple that came to Deba in 1620 recruited to teach Basque artisans how to work with sealskin?

Re-exportation of Sealskins

16 The Mutriku port register for 1582–1640 contains other indicators of the sealskin trade. The 1634 (new style) entries include a ledger of expenses and profits for a voyage to Lisbon, by a zabra (or patache44 ) named Nuestra Señora de la Antigua and commanded by Jacobe de Gastañeta. The vessel transported 281 skins of perros marinos, gauged as 35 quintals for about 5.73 kilograms per skin. 45 This shipment brought a profit of 1 real per skin, in addition to the ship’s main cargo of 728 quintals of various iron products. 46

17 The document provides a glimpse of Mutriku’s seaborne trade in the seventeenth century, which included sealskins from Labrador. Two-thirds of the zabra’s profits went to its crew, while the other third was divided among three associated shippers or outfitters, to the sum of 1,926 reales. From this amount, 607 reales were deducted to cover the cost of emergency repairs in Galicia, leaving 443 reales for each shipper. The three associates were all from Mutriku and are identified as Ysabel de Laranga, widow; Pedro de Ydiaquez; and the captain, Jacobe de Gastañeta. Laranga was the daughter and widow of prominent ship and mill owners, while Ydiaquez was a well-known naval commander and the mayor (alcalde) who, in 1636, donated a hundred piles for the wharf and tannery located at a place called Anchirri or Inchirri. 47 In addition to the skins he shared with his two associates, Ydiaquez shipped 79 sealskins in his own name on the Nuestra Señora de la Antigua. Thus, in total, the zabra transported 360 sealskins to Lisbon. 48 By way of comparison, the annual production of a French sealing concession in Labrador in the eighteenth century, while notoriously variable from year to year, could attain 1,150 skins and 170 barriques of seal oil.49

18 Most of the records we have found on the Basque seal hunt and sealskin trade date to the years 1603–37, but at least two documents show that this activity continued into the 1660s. In Mutriku, the last record we know is a 1656 letter of payment. Miguel Lopez de Goycoechea, from the locality of Iturmendi in Navarre, purchased 89 perro marino skins from Maria Santuru de Asin, of Mutriku, at 8 reales per skin. This document allows us to follow the Labrador sealskins to inland destinations, in this case to the region of Altsasu about 50 kilometres from Mutriku. Despite our research on Maria Santuru de Asin, we have found no information about her link with the sealskin trade.50

19 The last source we know is an agreement dated 25 February 1661, between the Zubiburu (Ciboure) outfitter Saubat de Haristeguy and master mariner Martin Detcheverry from the parish of Askain in Lapurdi (Labourd). Detcheverry promised to sail with 12 other men in a ship to be designated by Haristeguy, “to Terranova and the Isle of La Magdalaine to winter there, conduct the seal fishery and convert the seal into oil.” 51 In return, Detcheverry and his men could keep a third of the oil and “other merchandise.” The agreement shows that Lapurdian Basques also pursued the seal hunt, not only in Labrador but as far south as the Magdalene Islands. We hope other researchers can learn more about these later mentions of the seventeenth-century Basque seal hunt.

Conclusions

20 Sealing voyages lay at the base of a transatlantic trade that led to the tanners and shoemakers of Deba and Mutriku. In these Basque ports, sealskins entered a leather industry where they were tanned, transformed into specialized sailors’ footwear, and sometimes re-exported. The skins were tanned in adoberías along with the skins of cows and goats, and were cut and stitched into footwear by zapateros (shoemakers). While the sealskins were tanned in vats alongside the hides of cattle and sheep, they had a unique use as footwear supplied to sailors headed for Labrador. Other tanned sealskins were sold to Lisbon and Navarre, in a trade of significant value.

21 Owing to the constraints of our project on mills and millstones, our research has been limited to the archives of a single port, Mutriku, in the period before 1640. The archives of other Basque ports, such as Hondarribia (Fontarrabia) and Bayonne, may contain more information on the seventeenth-century sealskin trades.

22 Despite the limitations of our research, the Mutriku archives reveal a poorly known facet of Basque activities in Labrador. They illuminate the seventeenth century, the least-known period of the Basque presence around the Gulf of St. Lawrence. 52 Like whales, seals provided oil, but their skins also had commercial value for the Basque leather trades. More so than whaling or cod fishing, the seal trade brought the Basques into contact with the Inuit. Of course, Labrador was the principal theatre of relations between Basques and Inuit, but these relations also extended to the Basque Country, as seen in the settlement of an Inuit family in Deba, the adoption of sealskin kamiks by Basque sailors, and possibly the transmission of Inuit knowledge to Basque shoemakers.

Appendix 1: Documents Relating to Antonio de Iturribalzaga of Mutriku (born c. 1592)

Iturribalzaga was the maternal uncle of the royal naval architect Antonio de Gaztañeta. José Antonio Azpiazu and Maria D. Erviti, “Antecedentes y primera época de Gaztañeta,” in Antonio de Gaztañeta, 1656–1728 (Donostia–San Sebastián: Untzi Museoa, 1992), 15–24. Cited in Azpiazu (2016: 26, 35–36, 52, 179).

1613. Outfits a cod fishing ship for a destination in Terranova or “Frislandia.” Cited by Azpiazu (2008: 133), no reference given.

1615. Sails for cod to Terranova in the Nuestra Señora del Rosario, owned by Juan Lopez de Irure of Zumaia. AHPG–GPAH, 1/2620, fol. 17. Cited by Azpiazu (2008: 134).

1616. Said to be in Terranova on 31 July. AHPG–GPAH, 1/2620, fol. 120. Cited in Azpiazu (2008: 134).

1618. Sails to Terranova for “bacalao, rabas y grasa” in the 80-ton ship of Joanes de Laçon (Lasson) of Saint-Jean-de-Luz. AHPG–GPAH, 1/2602, fol. 44. Cited by Azpiazu (2016: 179).

1618(?). Is headed to Terranova for cod in an 80-ton barque, owned by Juan de Lazon (Lasson) of Saint-Jean-de-Luz. AHPG–GPAH, 1/2602, fol. 120. Cited by Azpiazu, (2008: 134).

1620(?). On “el camino de Terranova” for cod. AHPG–GPAH, 1/2607, fol. 29. Cited in Azpiazu (2008: 134).

1622. Having built the ship Nuestra Señora de la Concepcion two years previously, Iturribalzaga is preparing it for its first voyage to Terranova. AHPG–GPAH, 1/2603, unfoliated. Cited by Azpiazu (2008: 134–35).

1624. Sails as captain of the ship San Sebastián to Granbaya, “al puerto que llaman de los Ornos,” outfitted to take “ballenas, perros marinos y (2008: 135; 2016: 179).

1624. At the end of the year, aged 36 years, Iturribalzaga bid on a whale that his father Domingo had taken with his pinaza near Mutriku. AHPG–GPAH, 1/2612, 69r–70r.

1626. Returns to “al puerto de los Ornos a pesca de ballenas, perros marinos y bacallao.” AHPG–GPAH, 1/2605, fol. 26. Cited by Azpiazu (2008: 135; 2016: 179)

1629. His ship the San Pedro is ready to leave for Granbaya, to hunt whales and perros marinos (seal). AHPG–GPAH, 1/2623, s. fol., 1630. Cited by Azpiazu (2008: 135–36).

1630. On 11 April, he leaves for Granbaya “a la pesca de ballenas y perros marinos” as captain and master of the ship San Pedro. Cited by Azpiazu (2016: 179), no reference given.

1630. In July, he is named in the will of Domingo de Petriyarza, a sailor on La Piedad, owned by the family of Cristobal Basurto of Getaria. AHPG–GPAH, 1/2623, B, fol. 74r–81v, notary Domingo de Ibarra. Transcribed by Barkham (1987: 185–86).

1632. Named in the will of a sailor, Joan de Hea, at San Jorge Island (St. George) “en la canal de la Gran Baya.” AHPG–GPAH, 1/2623, D, fol. 118r–122v.

1635. On 8 June, he is in Terranova while his procurors sell 280 “pellejos de perros marinos” to the shoemaker (zapatero) Martin de Larralde of Mutriku. AHPG–GPAH, 1/2623, unfoliated. Transcribed by Barkham (1987: 185).

Appendix 2: From AHPG–GPAH, 1/2624, C, fol. 80r-80v, 8 June 1635

En la villa de Motrico, a ocho dias del mes de junio de mill y seiçientos y treinta y çinco años a ora de las nueve de la mañana ante mi Domingo de Ybarra scrivano rreal y del numero de la dicha villa y testigos de yuso escritos parescio Martin de Larralde ofiçial de azer calçado vezino de la dicha villa y dixo que se obligava y obligo de dar y pagar y que dara y pagara a Maria Nicolas de Armunoeta viuda vezina de la dicha villa que estava presente o a quien su poder o derecho tubiere çien ducados de a onze rreales cada uno en vellon que la devia y heran por rraçon de otros tantos que le avia dado y entregado prestados por azerle buena obra en dineros de contado en la dicha moneda de vellon . . . . todos los cueros y pellejos de bacas bueyes cabrones y de perros marinos que al presente tiene curando en las adoberias y en su cassa en esta villa que son por una parte quarenta y seis cueros de bacas y bueyes que compro en venta judiçial por pascoa de spiritu santo pasado deste año en la villa de Guetaria y otros diez cueros de bacas y diez y ocho pellejos de cabrones y quarenta de perros marinos, y mas obligo e ypoteco toda la erramienta de su oficio y dos tinas grandes de curar cueros que tiene en la dicha casa de su morada para que esten obligados e ypotecados espresamente para la dicha paga y seguridad . . . .

Appendix 3: From AHPG–GPAH, 1/2624, C, fol. 81r-81v, 8 June 1635

En la villa de Motrico, a ocho dias del mes de junio de mill y seiçientos y treinta y çinco años a ora de las tres a las quatro de la tarde ante mi Domingo de Ybarra scrivano rreal y del numero de la dicha villa y testigos de yuso escritos parescio Martin de Larralde vezino de la dicha villa y dixo que el capitan Antonio de Yturribalçaga vezino della le avia dado y entregado dozientos y ochenta pellejos de perros marinos los dozientos dellos a dos rreales y veinte maravedies cada uno y los ochenta rrestantes a dos rreales cada uno todo en vellon y dellos se dio por entregado y porque su entrega de presente no paresçe rrenuncio las leyes que ablan sobre vistas y pruebas de las pagas y entregas como en ellas se contienen y que a los dichos preçios montan los dichos pellejos seisçientos y setenta y siete rreales y veinte y dos maravedies y que para en quenta y parte de pago dellos avia pagado trezientos y treinta y ocho rreales en esta manera, los dozientos y veinte y quatro rreales al dicho capitan Antonio quando estava de partida para Terranoba donde al presente esta en calçados y otras obras de su oficio que hubo menester para la dicha Terranoba y despues que el partio para alla avia dado por el y su nombre y como a su poder aviente a Maria Nicolas de Ybaseta viuda vezina desta dicha villa ochenta y quatro rreales en dinero y treinta rreales en calçado para la casa del dicho Antonio con que son los dichos trezientos y treinta y ocho rreales y baxados de los dichos seisçientos y setenta y siete rreales y veinte y dos maravedies debe de rresto trezientos y treinta y ocho rreales y doze maravedis los quales se obligo de dar y pagar y que dara y pagara al dicho capitan Antonio de Yturribalçaga o a quien su poder o derecho tubiere para el dia de navidad primero benidero fin de este dicho presente año los diez ducados dellos en dineros de contado y lo rrestante en calçado para el y su casa sin otro plaço alguno llanamente y sin pleito con mas las costas que en su cobrança se le siguieren y rrecresçieren y para ello obligo su persona y bienes avidos y por aver generalmente y especial y espressamente obligo e ypoteco para la dicha paga y seguridad todos los cueros de bueyes y bacas y pellejos de perros marinos y de cabrones que tiene curandolos en la casa de su morada en esta dicha villa y en las adoberias de la rribera della y toda la erramienta de su officio y dos tinas grandes que tiene en la casa donde vive para curar los cueros para que especialmente estén obligados e ypotecados para la paga y seguridad de los dichos trezientos y treinta y ocho rreales y doze maravedis sin que la obligaçion general de su persona y bienes . . . .