Christian Gottlob Barth and the Moravian Inuktitut Book Culture of Labrador

Introduction

1 The following paper was delivered in part at a symposium on Newfoundland and Labrador Book History.1 It was subsequently developed into a contribution to the literary and intellectual history of Moravians in Labrador.2 As such, it seeks not to analyze by social scientific methods the culture contact between Inuit and Europeans but to map out one potent religious and literary influence of the encounter. In so doing we are led to Christian Gottlob Barth, a figure of the German Erweckungsbewegung, a Continental expression of the global religious revival movement called the Second Great Awakening that had deep roots in the older Pietism.3 Barth was one of the most prolific periodical and literary voices influencing foreign missions a few decades before and after the middle of the nineteenth century. The nature of his contact with missionaries and Inuit in Labrador and the literary scope of the encounter are the subject of this paper. Up to this point, we have known very little about Barth’s religious influence in Labrador. This paper seeks to remedy the obvious neglect through an examination of all relevant archival and literary sources from which Barth’s presence in Labrador can be seen. Once the extent and nature of his literary influence are known, cultural historians can better analyze the effect his intellectual and theological presence may have had upon Inuit culture.

Moravian Literacy in Labrador

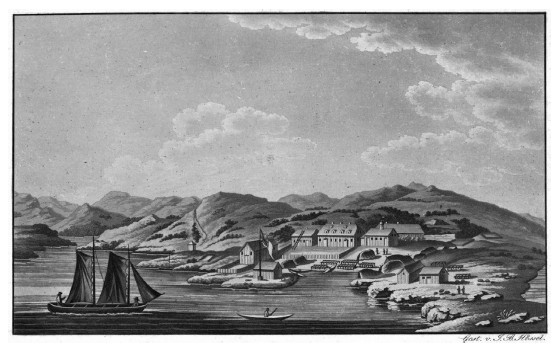

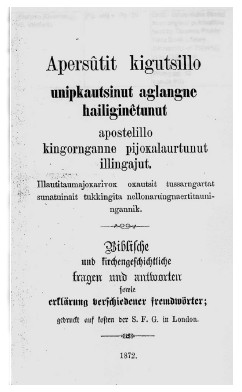

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 12 From the eighteenth century on, the Moravian Church has had a pervasive presence on Labrador’s north coast.4 Perhaps rivalled in its antiquity only by the Waldensians, this old Protestant institution, founded in 1457, with roots in the reform efforts of Jan Hus of Prague, became a worldwide mission-oriented church after its renewal under Count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf in Herrnhut, Saxony. Familiarity of Moravian missionaries with Inuit and the Inuit language since the 1730s in Danish-governed Greenland led in the second half of the eighteenth century to Moravian settlements in Nain (1771–), Okak (1776–1919), and Hopedale (1782–) on Labrador’s north coast (see Figure 1), in what today is known as Nunatsiavut. The churches and settlements were governed by religious ideals grounded in Biblical, liturgical, and catechetical literature and had as distinctive cultural contributions universal education and literacy in Inuktitut for male and female church members.5 As before in Greenland, Moravian missionaries to Labrador gave the Labrador dialect of the Inuit language a written form in the Roman alphabet that was taught in Labrador schools from 1780 until well into the twentieth century.6 Pervasive Inuktitut literacy also resulted in a body of printed literature, which commenced with the first primer of 1790 printed at the Moravian printing press at Barby, Saxony (today’s Saxony-Anhalt), and shipped to Labrador for use in Moravian schools.7 The body of Inuktitut literature that emerged consisted largely of Biblical, liturgical, hymnal, devotional, and catechetical texts, but also featured religious fiction and geographical and other literature. In the early twentieth century, a printing press in Nain published smaller catechetical works and modern religious hymns as well as a periodical.8 Education and literacy even spread through lay instruction to areas in the south, such as Snooks Cove and Karawalla, which had an Inuit presence but no Moravian settlements.9

3 Education and literacy were already a hallmark of the original Unitas Fratrum (Jednota bratrská) that had preceded the eighteenth-century worldwide mission-minded Renewed Moravian Church in what today is the Czech Republic. Jan Amos Comenius, the last bishop of the old Unity of the Brethren and the man after whom the school in Hopedale, Labrador, is named, was also a pioneer in early modern education. In the seventeenth century he advocated universal education “for all young people, for nobility and common people, for rich and poor, for the children of both sexes.”10 Likewise, the Moravian pedagogue and churchman Paul Eugen Layritz, who in 1773 finished writing the educational classic Betrachtungen über eine verständige und christliche Erziehung der Kinder [Reflections on the Reasonable and Christian Education of Children] in St. John’s harbour on his way to Labrador, promoted universal and — for its time — relatively nonviolent instruction of children.11

4 While education and literacy were valued as being of universal value, they were by no means autonomous expressions of culture but closely related to their missionary context and the church’s evangelistic intentions. The missionaries found literacy indispensable for communicating and maintaining their faith through liturgical, devotional, and Biblical texts. The eighteenth-century Moravian leader August Gottlieb Spangenberg (1704–1792), in his programmatic book on how to conduct missionary work, Von der Arbeit der evangelischen Brüder unter den Heiden [About the Work of the Evangelical Brethren among the Heathen],12 which in 1788 appeared in English as An account of the manner in which the Protestant church of the Unitas Fratrum, or United Brethren, preach the gospel, and carry on their missions among the heathen,13 recommended that “wherever it is practicable, as, for example, in Greenland, they keep schools for them [the Indigenous congregations], instructing them in reading, and other useful things.”14 To help missionaries acquire foreign languages in their far-flung global locales, in which the language of the Indigenous population was spoken and written, Spangenberg instructed them to write their own dictionaries and grammars. This made Moravian missionaries worldwide pioneers in lexicography and foreign language acquisition. In Labrador, the originally handwritten dictionaries and grammars were printed in the second half of the nineteenth century.15

The Bible in Labrador

5 After the publication of the Inuktitut primer, the first substantive religious book, translated by Johann Ludwig Beck into the Labrador Inuktitut dialect, was the passion narrative of the Gospels, published in 1800.16 The book was part of a larger tome that featured the Harmony of the Gospels, a work that compiled the four Gospels into one harmonious narrative and appeared in full in an 1810 Inuktitut translation.17 The Harmony of the Gospels is a Christian Biblical and devotional genre. Its origin can be found in the early Christian apologetic period, where Tatian wrote his Diatessaron in c. AD 172, a Gospel narrative compiled from the four Gospels that was used extensively in the Syrian churches and among other second-century Christians.18 The genre was revived in Moravian circles of the eighteenth century by Count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf and Samuel Lieberkühn and found use in translation in several missionary locales.19 The passion narrative, a central object of Moravian devotion and theology, had proven to be of importance to missions among the Greenland Inuit and Native Americans. In Labrador, the translated and eventually printed passion narrative of the Gospel harmony became a powerful vehicle in the transmission of Moravian piety, notably when it was adopted as a textbook in schools. The Inuktitut passion narrative enabled a closer identification of believers with the Christian drama of sin and salvation in Moravian soteriology. As I have written elsewhere, during the Hopedale Revival of 1804–05 a paradigmatic shift “occurred in the religious self-understanding of the Inuit. People moved from a relatively superficial understanding of Christianity . . . to an existential understanding of sin and salvation through participation in Christ’s atoning death.”20 The printed passion narrative was key to the indigenizing of the Moravian faith among Labrador Inuit.

6 The importance of the Bible for Moravian theology and devotion was passed on to the Inuit of Labrador and shaped their religious outlook.21 After the publication of the passion narrative and Gospel harmony, individual books of the New Testament appeared in print and were underwritten by the recently founded British and Foreign Bible Society. The Gospel of John, as found in the Harmony of the Gospels, was first published separately in 1810,22 and eventually the entire New Testament was completed. 23 In 1871, when Moravians celebrated their first century in Labrador, the entire Bible had been translated in several volumes into Labrador Inuktitut. Besides the Biblical text, one of the most valued books among the Christian Inuit was a popular and illustrated volume of Bible stories that had become a worldwide religious best-seller during the nineteenth century. Published by Christian Gottlob Barth (1799–1862) in Calw, Württemberg, it contained 52 stories from the Old Testament and 52 from the New Testament.24 The book, which went through two Inuktitut editions, served in Labrador not only as a devotional reader but also, along with a matching book of questions and answers, as a text for religious instruction within the Moravian school system.

Christian Gottlob Barth and Labrador

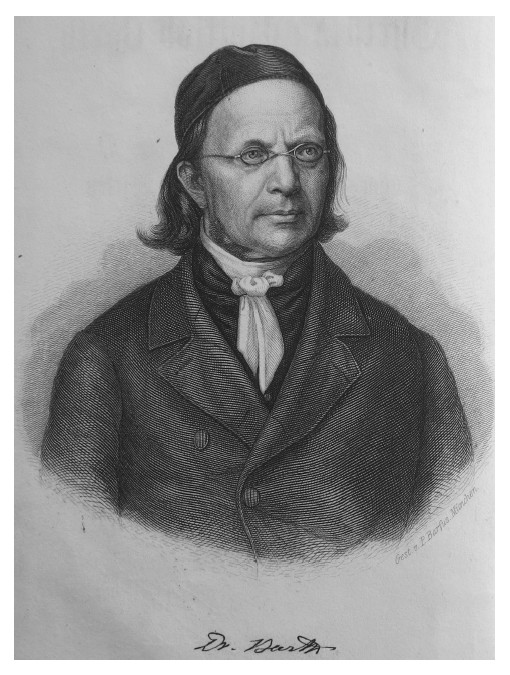

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 27 Christian Gottlob Barth (Figure 2) was a Protestant pastor in Württemberg, who came out of German Pietism and developed a religious publishing empire in the city of Calw with a worldwide outreach. In Barth’s eschatologically oriented theology, worldwide missions featured as a goal and instrument in establishing the Kingdom of God. Barth became famous for his tracts and books that promoted the religious individualism and emotional piety of the Second Great Awakening. He also founded several magazines, most notably the Calwer Missionsblatt, in which he featured the work of the Moravian missionaries in Labrador and correspondence with Inuit as well as missionary efforts in other worldwide locales.

8 Barth’s direct links to Labrador were through Moravian missionaries from Württemberg whom he knew personally, especially the family of Johann Conrad Weiz (1780–1857), an old friend whom he had visited as early as 1819 in Königsfeld, a traditional Moravian settlement in the Kingdom of Württemberg.25 Weiz, a pious bookbinder whose spiritual advice was sought by many, supported Barth’s activities, supplied him with Moravian missionary reports, and represented a living link to the mission field through his children, who were working in Suriname, Africa, and Labrador.26 When Weiz’s son Samuel (1823–1888), a prominent Labrador missionary, first went to Labrador, his father told him how happy Barth had been about this decision and hoped to see him prior to his departure in London.27 In fact, Barth had attended the baptism of Johann Conrad Weiz’s son Samuel. In addition to Samuel, two of his sisters had married well-known Labrador missionaries. Charlotte Friederike Weiz (1821– 1883) was married to Johann Karl August Ribbach (1817–1891), and Auguste Weiz (1818–1886) was the wife of the Labrador missionary and Inuktitut lexicographer Friedrich Erdmann (1810–1873).28 Barth and Johann Conrad Weiz shared a spiritual friendship with Princess Henriette von Nassau-Weilburg (1780–1857), who resided in the castle at Kirchheim, Württemberg, and received her support and encouragement. The princess supported and took a keen interest in Christian social activities and mission work, including that of Weiz’s children in Labrador.29

9 In addition to the Weiz family, 11 Moravian missionaries from Württemberg shared a common pietistic culture and served in Labrador during the first century of its mission.30 Another missionary, Carl Gottfried Albrecht (1800–1888) from Saxony, had visited with Barth in Calw prior to his posting to Hopedale and brought with him to Labrador a package of tracts, pictures, and missionary literature supplied by the publisher.31

10 Barth also had wider links to the Moravian Church. In 1838 he had personally introduced himself to the Moravian Ministerial Conference (Prediger Conferenz), acknowledging the Church’s common foundation with his own missionary interests and that he had “continuous connections to several of its missionary posts.”32 He also knew the captains of the Moravian mission ship that annually visited the Labrador coast and on several occasions attended meetings of the British Moravian missionary society, the Society for the Furtherance of the Gospel (SFG).33 At a meeting of the SFG in 1850, Barth “delivered a short affectionate address, expressive of his deep interest in the Mission among the Esquimaux, and reminding all who heard him of the privilege and duty of seeking the extension of Christ’s kingdom, and working for this blessed object ‘while it is called to-day.’”34 The address indicated how much Barth saw in the work of the Labrador missionaries an eschatological realization of the Kingdom of God. The connections of Barth with Labrador grew so close that the missionaries supplied him with specimens from natural history, among them two polar bears, that the pastor contributed with other specimens to German museum collections. For his scientific contributions, Barth was even honoured with having a Labrador species of sea cucumber, the Orcula or Ekmania barthii, named after him.35 With a load of peas, he also purchased an island near Nain, which still today is named “Barth Island” after him. 36

11 The religious and intellectual links with Barth and his organization in Calw pervade the diaries and correspondence of the missionaries from the 1830s until well after his death. Books from Barth’s publishing house were strongly represented in the Moravian libraries of Labrador. The Hebron library catalogue from 1896 identifies expressis verbis as many as 44 of 136 books as having been published in Barth’s publishing house at Calw.37 Not only religious literature by Barth but also a wide range of reference works in natural history, history, and biography as well as theological literature can be found there. Reference works such as Wolfgang Menzel’s three-volume Naturkunde im christlichen Geiste aufgefasst and Christian Gottlieb Blumhardt’s Handbüchlein der Missionsgeschichte und Missionsgeographie are represented in the still extant Moravian library at Hopedale.38 Two Hopedale missionaries made much use of the four-volume Evangelische Schullehrerbibel on which Barth had also worked.39 The Hebron missionaries also regularly received the mimeographed circular letters from Barth and his successor from 1845 to 1861.40 In addition, Barth also sent packages with school supplies, such as maps, globes, and illustrated posters, to Labrador.41 He also organized regular collections of dried fruit and peas throughout Württemberg, which were then annually shipped to Labrador for distribution among the missionaries and their flock.42

Christian Gottlob Barth and His Inuktitut Tracts and Bible Stories

Barth’s Correspondence with Inuit in Labrador

12 In 1832, the missionary magazine Calwer Missionsblatt started publishing not only reports and grateful acknowledgements for print publications sent to Labrador missionaries but also communications of Inuit with Barth. Notably, the Hopedale Inuk and lay leader Amos engaged in correspondence with the German clergyman and writer. Amos, the most literate among the Inuit lay leaders in the congregation, was born in the Hopedale area in 1781. As a child, Angutauge — his Inuktitut name — went to Nain, where he was raised by relatives. He attended school there and progressed well. In fact, his literacy is the reason we still have several letters from him in Inuktitut and in English and German translations, as well as an exchange in the German periodical Calwer Missionblatt with its editor, Christian Gottlob Barth. Even during his final illness, Amos continued reading his Bible and other books.43 As a young man of 18 he had returned to Hopedale and married Elisabeth, who also served as a chapel servant and, later, as a “Native Helper” to the women of the congregation. What distinguished Amos from other congregants in the eyes of the missionaries was his exceptional understanding of the Bible. While admonishing the congregation in a loving manner, he met the exceedingly high religious and moral expectations of the European missionaries. Amos served for 23 years as a chapel servant but died after only one year in his extended capacity as a National Assistant or Native Helper.44 He also aided each new missionary who came to Hopedale in learning Inuktitut and contributed to the physical well-being of the missionary families by supplying the needed water for the mission. In April 1841 he came down with influenza, of which he died eight days later.45

13 Missionary Friedrich Carl Fritsche (1796–1845), stationed in Hopedale since 1827, translated a letter of Amos in 1832 for publication in Barth’s magazine, in which Amos shared his common faith with “Brother Barth” and thanked him in the name of his children for the dried fruit they had received.46 In subsequent years, until Amos’s death, there was an active exchange of letters with Barth.47 Amos’s letters appeared in the German magazine sometimes in paraphrase rather than in a literal translation from Inuktitut, so that they could be better understood by the readership.48 The letters usually express gratefulness for the interest shown in the Labrador Inuit and thanks for gifts of fruit and peas sent to them.

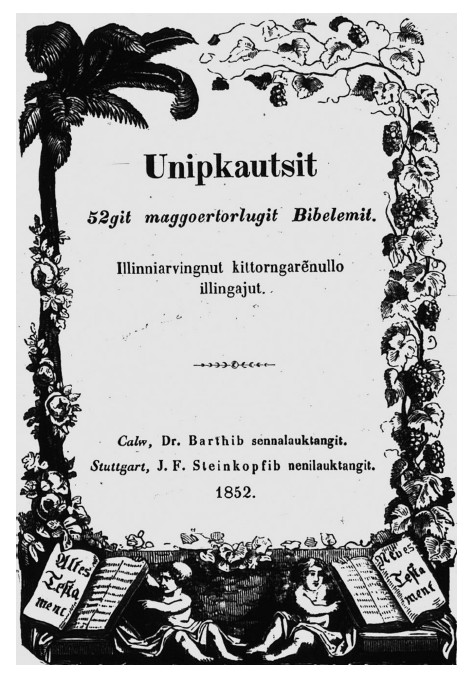

14 From 1836, the missionaries and Amos also gratefully acknowledged tracts in Inuktitut sent to them. Missionary Johann Samuel Meisner (1770–1839) reported in the magazine about the reaction of children to the Inuktitut tracts distributed in Hopedale before Christmas 1836. “I wish you could have seen the friendly faces of the children as the little tracts were distributed on 21 December, a joy as never seen before. If I could draw,” Meissner wrote, “I would paint you a little girl of four-and-a-half years of age, who came . . . into my room, stood with folded hands in front of me and recited by heart with all simplicity the sayings that were printed under the pictures in the little book.”49 Also, the missionary Samuel Stürmann (1766–1839) wrote from Okak that the “neat little tracts” from the previous year and 1836 were well received by the students. “We had first decided,” wrote Stürmann, “to give each of the schoolchildren under 14 years of age such a little tract, if they could spell. But this would not work. As soon as they had been distributed among the children, there came others and said that they had not been present, and yet others, who hardly know the alphabet, who also wanted such a little writing — agloârsungmik.” The adults then demanded such little books as well and were disappointed when told that the benefactor had only intended such tracts for the children. But, in the end, the missionary could supply all who had desired it with at least one such tract.

15 In his letter of 1836, Amos expressed to Barth his wish to see more tracts. The entire letter is characteristically pervaded with an air of otherworldliness and devotion, a piety that Amos shared with his German correspondent. He thanked “Brother Barth” very much for his words of encouragement “to watch and wait for the Lord with the oil-filled lamp,” an obvious reference to Matthew’s eschatological parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins (Matthew 25:1–13), who were waiting in expectation of Christ’s return for the Last Judgment. Although Amos would never be able to meet his correspondent on earth, he was confident that Jesus would make it possible for them to meet in heaven. “My dear Brother Barth!” he wrote, “as long as I live, I will not forget you. We are walking now with one another on the way to heaven (manna ingerarkatikgekpoguk apkome ullapersartauvionartome.).”50

16 In 1838, further tracts were translated by the missionary Carl Gottfried Albrecht. Those already printed were distributed in Labrador, usually around festive occasions or at school.51 In 1839, Amos continued his correspondence with Barth in the otherworldly tone of the preceding years. The death of a crew member was for him yet another sign of human vulnerability and a reminder that he would be with Christ before he reached the age of 50. He was also grateful once more for the “little writings” he had received from Barth.52 Christian Trauelsen Barsoe (1810–1893), a missionary stationed in Hopedale, wrote Barth that he was gratified to see such a great desire for reading among the children. Even during the worst weather mothers brought their children on their backs to school, some of whom had not even reached four years of age. The following year, Missionary Albrecht was grateful to Barth for scriptural tracts in Inuktitut that had been illustrated with woodcuts. These tracts were likely parts of the yet unpublished Inuktitut volume of Bible stories. He wrote that the children requested him to “convey their heartfelt thanks to Barde, as they call their unknown benefactor.” The missionary told Barth and the readers of the Calwer Missionsblatt that one evening “there came to me a little girl, of about eight years of age, and accosted me thus: — ‘Ahak,’ (the ordinary salutation of an Esquimaux), ‘I have words for Barde, and salute him heartily. I wish him not to be displeased or sorrowful; for I am determined to live to Jesus. I am His property; for He has shed His blood for me, and I have been dedicated to Him in baptism. On this account, I love Him.’ Her tears flowed freely while she uttered these words.”53 Such emotion-filled, naive narratives demonstrated to Barth and the pious readers of his magazine the success of their support for foreign missions. The evangelical missionary movement had roots in the global religious renewal known as the First Great Awakening of the eighteenth century and was developed and more thoroughly organized during the Second Great Awakening. The German expression of the latter, termed Erweckungsbewegung, found a fertile ground in Continental Pietistic circles. Pietism, despite its less than unified theology, was a source feeding the Renewed Moravian Church in Herrnhut. The foreign missionary initiatives undertaken by the Halle Pietists had stimulated the early interest in mission of Count Zinzendorf, the Moravian leader.

17 The last letter of Amos published in the Calwer Missionsblatt was penned in 1840. In it, Amos shows his spiritual attachment and personal loyalty to Barth, with whom he shared “Jesus’s works, word, comfort, and kindness.” He was very happy about the communication he had received from Württemberg and now shared in turn with his Christian brother the sad news about the loss of his son Daniel during the past winter, comforted only by the fact that until the end, Daniel “had words that made him joyful.” He also rejoiced over a population increase in Hopedale, since 17 people in all regretted their original departure and had returned to be converted in the Moravian settlement. He was also able to report that local church members and communicants had increased in the community.54

18 Amos died during the influenza epidemic of 1841, and his death is detailed to readers of the Missionsblatt. Missionary Barsoe noted especially the fact that in his final illness he was still interested in reading. Next to the caribou skin on which the ailing Amos lay, the missionary noticed a box with the New Testament and other books. “Can you still endure reading,” Barsoe asked Amos, who replied: “‘Yes . . . , I was still able to read something,’ and added: ‘God’s Word is very thankworthy, my companions should be truly thankful to you and your brethren across the sea. . . .’”55

19 In the years following Amos’s death, the mailing of tracts continued, and there were letters from other Inuit, notably Joseph and Ludwig, who continued the correspondence with Barth.56 Missionary Barsoe used the illustrated tracts sent to him as incentives and gifts for those children who had learned well in school.57 A missionary in Hopedale, who in 1846 requested thank-you letters from those children to whom he had given tracts as Christmas presents, received 14 letters. Quotes from five children were published in the Calwer Missionsblatt in 1846. 58 In 1853, David, the grandson of Barth’s former correspondent Amos, wrote to the German writer that he still treasured the correspondence between Barth and his grandfather, which also his father Simeon had read with great pleasure. None of Barth’s personal letters to Inuit have been preserved, presumably because of the harsh climate on the Labrador coast and the seasonal movements of Inuit families. Another grandson, Matthaeus, the son of Daniel, replied to Barth with news about his own family, just as Simeon and Amos had kept him informed of their families. Matthaeus remained happy and grateful for Barth’s “small blessed writings,” in that they showed him the mercy and salvation of Christ’s sacrificial death.59

Barth’s Religious Tracts

20 The “little writings” or tracts (Inuktitut: agloârsungmik) that are mentioned so often in the correspondence of the missionaries from 1836 on appear to be pre-published excerpts of the book of Bible stories or uplifting illustrated Christian biographies Barth had written, such as the one of Jerry Creed.60 According to the station diaries of Okak and Hopedale, the first “little writings” in Inuktitut were received and distributed in 1835. The diary of Hopedale mentions specifically that “a joy of this kind they never had before.”61 In the diary of Okak we read that thanks to “Pastor Barth, the editor of the Calwer Missionsblatt,” “a good number of little writings in the Eskimo language that contained next to the depiction of the acts of the dear Saviour the Bible verses where they are described” were distributed on Christmas day to all children who could read or spell or were learning it. The great desire of people to receive such writings, according to the missionaries, was likely due to the fact that they had pictures.62

21 The publication of such tracts had led Barth to found the Calwer Traktatverein (Calw Tract Society) in 1829 and establish collaboration with the Stuttgart-based publishing house of J.F. Steinkopf and other tract societies in England and America.63 Although there were likely more, I have been able to trace 13 Inuktitut tracts printed in the Labrador Inuktitut dialect. The translators of the tracts, except for Carl Gottfried Albrecht, remain unknown, but are likely found among the then active or retired Moravian missionaries to Labrador. The ones identifying the publisher were published between 1842 and 1851 at J.F. Steinkopf in Stuttgart. Those without indication of a publisher likely came from the same publishing house; 11 of these tracts are mentioned in James Constantine Pilling’s Bibliography of the Eskimo Language (1887). Two tracts not listed in Pilling (1846 and 1847a in Appendix 2 below) were located elsewhere.

Barth’s “Bible Stories”

22 The publication authored by Barth that had the greatest impact on its readers in Labrador was his “Bible stories,” a worldwide best-seller translated into Inuktitut as Unipkautsit / 52git maggoertorlugit Bibelemit. / Illinniarvingnut kittorngarenullo / illingajut (Stories 52 in number repeated {2 times} from the Bible. For schools and families adapted64 ) (Stuttgart: J.F. Steinkopf, 1852).65 It was a small-sized illustrated book of 205 pages, containing 52 Bible stories from the Old Testament and 52 from the New Testament, followed by a Biblical chronology from the Pietist Johann Albrecht Bengel and two pages of corrigenda. The original German publication, titled Zweymal zwey und fünfzig biblische Geschichten für Schulen und Familien (Two times two and fifty biblical stories for schools and families],66 on which all subsequent, also augmented, editions and foreign-language editions are based, was first published in 1832 and, worldwide, went through more than 1,000 editions.67 The number of stories corresponds to one Old and New Testament story per week throughout the year. The genre, addressing a school audience but also read by the entire family, had been prepared during the Enlightenment and in Pietism. Its title and number of stories can already be found in the work of the high school teacher Johann Hübner (1668–1731), who in 1714 had published Zweymal zwei und fünfzig Auserlesene Biblische Historien aus dem Alten und Neuen Testamente . . . (Two times two and fifty selected Biblical histories from the Old and New Testament).68 Barth’s Biblical narratives range from Genesis to the spread of the Gospel by the apostles. Staying close to the Biblical text, the content of the New Testament ends with the narratives from the Acts of the Apostles. The New Testament epistles and Revelation are not covered. The Bible stories are illustrated with many appropriate woodcuts. Although Barth is credited as its only author, the Old Testament stories were written by Gottlob Ludwig Hochstetter, a pastor friend of Barth.69 While the book intended to oppose rationalism, its narrative content exhibits no extensive moral and theological intrusions and could thus be used by widely differing evangelical constituencies on the mission field.70

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 323 The translation of the first Inuktitut edition was carried out by the Moravian missionary Johannes Lundberg (1786–1856), who had returned to Europe in 1850.71 The translation work was first given to another retiree, Johann Ludwig Morhardt (1782–1854). But according to Superintendent Carl Traugott August Freitag (1807–1867), the quality of the translation, especially the final part, suffered so much from Morhardt’s “weakness of advanced age,” “that a mere correction would have been unsatisfactory.” Thus, Lundberg took over as translator.72 The printing history can be followed in the Minutes of the Unity Elders Conference from March 1851, when the elders first discussed Barth’s offer of publishing Lundberg’s Inuktitut translation, to February 1852, when Barth informed the elders that 500 of 1,000 copies would be ready for shipment to Labrador via the mission ship Harmony in London.73 As in other missionary locales, the illustrated book was a great success all along the Labrador coast, even in the most northerly locations. Hebron missionaries who visited outside members of their congregation in Saglek Bay found children in their tents reading Barth’s book.74

24 The book also found a more formal educational application when Superintendent and Inuktitut grammarian Theodor Bourquin used it as a basis for Biblical instruction and published a guide with questions and answers to each story.75 The companion volume went through four successive editions from 1872 to 1936.76 The German introduction of the 1872 edition stated: “These biblical questions and answers, which are conceived in close connection with the Bible stories from Calw, are not to replace the use of the latter in our schools but, on the contrary, to promote them.”77 Bourquin intended the book for use in the middle and upper classes of the Moravian school system, in which Inuit teachers also were employed. Even younger children without reading abilities, he hoped, would benefit from the questions and answers. With this younger readership in mind, the creation story and birth narrative of Jesus had been more extensively developed. While a catechism-like book invited often only rote learning, the Superintendent expected that variability in questions would eventually lead to a more thorough consideration of content. The increased Biblical literacy resulting from this companion book and the Bible stories, Bourquin hoped, would also later benefit those attending confirmation class. It had been the experience of teachers that by the time people were being confirmed, they had forgotten much of their earlier Bible knowledge.78 Even though the book was originally intended as a close companion to Barth’s book of Bible stories, it is possible that in the twentieth century, when the Inuktitut Bible stories were no longer reprinted, the volume was used eventually as an instructional stand-alone. But even such a use remained in scope and content the outcome of the earlier book on which it was based.

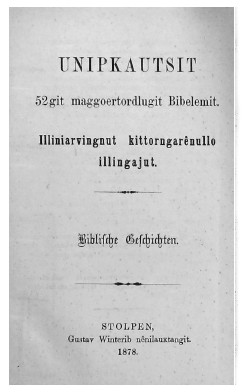

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4 Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 525 A second edition of Barth’s book was published in 1878.79 The translator was the retired missionary August Ribbach (1817–1891), who revised the text with consideration of comments made by Superintendent Theodor Bourquin. The missionaries had originally hoped to use the latest German edition of the Bible stories, including its illustrations, as basis for the revision and have it published with subsidies from the publishing house in Calw. Dr. Gundert, the successor of Christian Gottlob Barth, however, withdrew, his original offer, apparently for financial reasons. The new edition by Gustav Winter in Stolpen lacked the very popular illustrations it previously had.80 In his official Superintendent’s Report to the General Synod of the Moravian Church in 1879, Theodor Bourquin remarked that the Bible stories in the new edition that arrived in Labrador in 1878 were “not a new edition of the hitherto used little book from Calw but much more extensive (perhaps too extensive?).” The latter comment likely pertains to the larger physical size of the second edition.“But what is to be regretted the most,” the Superintendent continued, “is the fact that the pictures, as they appeared until now in the edition from Calw, were omitted. Thus, the only illustrated book [in Labrador] — a true children’s book — has ceased to exist.”81 Not until the 1901 Inuktitut edition of John Bunyan’s Pilgrims Progress, translated by trade inspector Christian Schmitt, would there be in print a fully illustrated book in Inuktitut.82

Summary

26 Education and Inuktitut literacy on Labrador’s north coast were closely related to the missionary context and the evangelistic intentions of the Moravian Church and produced a religious book culture that pervaded the daily life of Moravian Inuit. Through lay instruction it even spread to areas in southern Labrador that had an Inuit presence but no Moravian settlements. One of the most significant literary impulses in the nineteenth century came from German Pietism and Christian Gottlob Barth’s worldwide publishing empire in Calw, Württemberg. Barth, a Protestant clergyman and religious writer, saw mission as a goal and instrument of establishing the eschatological Kingdom of God on earth. In many Biblical and devotional tracts, and particularly through his world best-seller of 52 Old Testament and 52 New Testament Bible stories, Barth’s publishing house and allied printers reached a global audience. Tracts from Calw were translated by Labrador missionaries into Inuktitut during the 1830s and 1840s and printed in Württemberg for distribution on Labrador’s north coast. They served as gifts on festive occasions as well as incentives for children’s schoolwork. In 1852, Barth’s illustrated book of Bible stories appeared in an Inuktitut edition, translated from the German by the retired missionary Johannes Lundberg. In 1878, a revised non-illustrated second edition, translated by the former Labrador missionary August Ribbach, appeared in print. To enhance the educational value of Barth’s Bible stories, Theodor Bourquin, the Superintendent of Moravian missions in Labrador and Inuktitut grammarian, published a companion volume of questions and answers that went through four editions from 1872 to 1936. It was used in the Labrador school system and had the purpose of increasing Biblical knowledge. Literacy also enabled Moravian Inuit in the early nineteenth century to engage in a living dialogue with the German author of their tracts in the pages of his Christian magazine, Calwer Missionsblatt. The correspondence in Inuktitut and German was translated for the German readers and Inuit participants by Labrador missionaries. Inuit were thus able through their letters from the mission field to share a common faith and piety with European readers of the missionary magazine. The two conversation partners could thus see themselves as taking part in a common missionary enterprise that sought to realize the Kingdom of God on earth, preparatory to Christ’s return. Literacy and an emotion-filled otherworldly piety were the common idiom of this global religious communication.

Appendix 1: Moravian Missionaries to Labrador from Württemberg during the First Century of the Mission

27 Christoph Jakob Waiblinger (1709–1778; 1776–1778: Nain) from Laichingen

28 Andreas Ludwig Morhardt (1740–1791; 1771–1791: Nain) from Stuttgart

29 Christian Benedikt Henn (1780–1845; 1819–1840: Okak, Hopedale, Nain) from Bönnigheim

30 Georg Friedrich Knauss (1784–1859; 1815–1852: Nain, Okak, Hopedale) from Schorndorf

31 Johannes Körner (1781–1837; 1815–1837: Nain, Hopedale, Okak) from Waldenstein

32 Philipp Friedrich Bubser (1822–1858; 1849–1858: Okak, Hebron, Hopedale) from Königsfeld

33 Wilhelm Horlacher (1821–?; 1851–1859: Hopedale, Okak, Nain) from [Schwäbisch] Hall

34 Friedrich Thomas Weiler (1832–1886; 1865–1886: Hopedale, Nain, Zoar, Okak) from Königsfeld

35 Friedrich Wilhelm Rinderknecht (1836–1918; 1865–1892: Hopedale, Nain, Zoar) from Königsfeld

36 Samuel Bindschedler (1839–1919; 1867–1882: Hopedale, Nain) from Königsfeld

37 Gustav Adolf Hummel (1841–?; 1869–1870 Nain) from Reutlingen

38 Johann Friedrich Drechsler (1833–1910; 1875–1893: Hopedale, Nain, Zoar, Okak) from Schorndorf.83

Appendix 2: Inuktitut Tracts Authored by Christian Gottlob Bart

39 English translations of the Inuktitut titles below use Pilling’s literal translations or were translated for me by Ms. Sarah Townley, Nunatsiavut/Labrador. An asterisk indicates that I have personally viewed the tract.

40 *[1842]: Okpernermik mallingninganiglo [About faith and about obedience84 ]. No place: no publisher. 8 pp.

41 1844: Nauk taipkoa neinenik? [Where are the nine?85 ]. No place: no publisher. 8 pp. Illustrated.

42 1845a: Jerusalemib asserornekarnera [Jerusalem to destruction86 ; Jerusalem destroyed 87 ]. No place: no publisher. 8 pp.

43 *1845b: Kaumajok nellejunnik kaumatsitiksak [A plain explanation for the ignorant88 ]. Stuttgart: J.F. Steinkopf. 8 pp.

44 1845c: Pillitikset Kittornganut [Things meant-for-presents for children89 ]. No place: no publisher. 8 pp.

45 *1846: Josefe unnibkautsinnik [Joseph’s stories or teachings90 ]. Stuttgart: J.F. Steinkopf. 16 pp. illustrated.

46 *1847a: Gudib keñuêninga nâpkigosung – / ningalo sakkijartuk Jeremiase / Kreedib innôsingane [God’s askings for mercy . . . / and Creed’s life91 ]. Stuttgart: J.F. Steinkopf. 11 pp. illustrated.

47 1847b: Nalungiak Bethleheme [The child born at Bethlehem92 ]. Stuttgart: J.F. Steinkopf. 8 pp.

48 1848: Pingortitsinermik [About the creation93 ]. Stuttgart: J.F. Steinkopf. 8 pp.

49 *1849: Nukapiak angerarviksab nelliuningane [The youth his own departure’s at its time94 ]. Stuttgart: J.F. Steinkopf. 8 pp.

50 1850: Tamedsa Gudib kakkojanga [Here is God’s . . . bread95 ]. Stuttgart: J.F. Steinkopf. 8 pp.

51 *1851a: Bibelib / pivianarninga, saimanarningalo [The Bible / its preciousness and consolation96 ]. Stuttgart: J.F. Steinkopf. 8 pp. illustrated.

52 1851b: Nukakpiarkæk, Gudemik okau – / seeniglo assæniktuk [The two youths / God and his loving words97 ]. Stuttgart: J.F. Steinkopf. 7 pp.