Articles

Supporting Learning Readers in Post-Confederation Newfoundland:

A Collective and Distributed Enterprise

1 Most children learn to read in school, but their developing literacy is supported and reinforced elsewhere in their society. In the 1950s, as Newfoundland adjusted to changed governance within Canada, the task of supporting the literacy development of the new province’s children was distributed across many different institutions. In this article, I explore some of the organizations and people whose work, professional and voluntary, laid the groundwork for young readers to develop and flourish. The young reader who serves as the focus for my exploration is myself, aged between one and 13 in the years between 1950 and 1962 during which my literacy developed. But this story is not about me; rather, it involves the named and nameless individuals whose labour buttressed my earnest efforts to join the world of readers.

2 In this article, I explore the role of the “helpers” who contributed their part to fostering literacy development in the city of St. John’s in the 1950s and early 1960s. I draw from a larger study of my own literacy growth (Mackey, 2016), but here I look in more depth at the role of other individuals, particularly as they can be seen in the school system, the church, and the library. All education in Newfoundland during this era was framed by religion; my own denomination was the United Church of Canada. My particular examples are the K–11 system of Prince of Wales College (PWC), Gower Street United Church, and the Gosling Memorial Library. I look briefly at out-of-school literacy opportunities represented and promoted by the Canadian Girl Guides, and conclude with a brief glance at media institutions in the city that, inherently, promoted literacy: newspapers, magazines, movie theatres, and radio and television stations.

Background

Learning to Read in a Particular Context

3 William Barker, discussing the history of the book in Newfoundland, comments on the changes after 1949: “From Confederation onwards, there was expansion of other media and at the same time a rapidly and vastly developed book-based school system including the university, now extended to all social groups” (Barker, 2010: 22). Barker’s account of post-Confederation development swiftly moves past the 1950s: “The real liftoff occurred around 1967, anniversary of Canadian Confederation” (2010: 43). Doug Saunders questions whether 1967 marked quite such an uncomplicated watershed in Canada more generally, observing:

As they adjusted to new arrangements in Canada, Newfoundlanders certainly participated in some of the “profound changes” that Saunders describes — and they also joined in the “explosions” of creative change that followed the 1967 celebrations. Much of the groundwork for these incipient changes was humble, daily, and largely invisible. By focusing on the structures that supported child readers in the 1950s I explore an unheralded element of civic society.

4 The story of a learning reader has many universal features, but every Western reader masters the challenge of learning to interpret the abstract shapes of letters assembled in written words. That learning takes place in a specific local context, with specific local support structures. I learned to read in St. John’s in the 1950s. To what extent was this achievement a local activity? What specific components of life in St. John’s enabled and/or restricted my reading? What institutional decisions, made by professionals in some cases and by amateur volunteers in other cases, affected how the patterns of my literate life were shaped? To what degree is everybody’s reading local?

Recreating a Reading World: A Developing Methodology

5 As I explored my early reading environment, my initial ambition was to collect as many as possible of the materials with which I became literate in my youth, to develop at least a partial replication of the world of specialist children’s books and magazines, school and church mtexts, and mundane household reading that surrounded me. With help from libraries, second-hand bookstores, and family members, I acquired a collection that currently fills eleven 30-inch bookshelves. It comprises picture books, novels, school textbooks, adult and children’s magazines, Sunday school leaflets, Brownie documents, television programs, films, audio recordings, sheet music, knitting patterns, recipes, scrapbooks, diaries, family newsletters, and much, much more. This personal collection is augmented by relevant library holdings in St. John’s and Edmonton.

6 At first, I was content to conduct a textual study, re-reading and reflecting on the kinds of invitations these materials offered to a learning child. In the early stages of the project, I thought it merely incidental background information that I lived on Pennywell Road in St. John’s during the time span that saw my emergence as an increasingly confident reader. But, as I pored over the retrieved texts of my youth, I found that Pennywell Road had seeped irrevocably into my interpretation of these materials. Today, neither can I fully access my childhood readings of these books and documents nor can I subtract my childhood interpretation from my adult awareness. The physical, emotional, and institutional settings of my childhood are wired into the recognition I felt when I reopened books I had not looked at for half a century and more. Some elements of that childhood experience were accidents of geography. Many more were the consequence of deliberate decisions by many different people.

Documentation

7 What follows is a sampler of the work of agencies supporting child literacy in St. John’s in the 1950s, rather than a continuous account of any particular operation. Like a quilt pieced together out of different fabrics, this article presents an overall pattern of support structures through a series of snapshots, rather than an in-depth probing of any single institution. Its utility lies more in how it points to the complexity of the local setting in which a child learned to read, rather than as a guide to the history of any one organization or as any kind of exhaustive history of literacy support structures in St. John’s.

8 My documentation highlights the mid-1950s and, necessarily, is contingent on available records. For example, the 1956 PWC yearbook, the Collegian, provides the full text of the principal’s report for 1955, offering a wealth of detail about school organization. Provincial figures from 1949 and 1955 provide a context for the report.

9 The church data set is a random selection; for some unknown reason, my parents saved a church bulletin from 30 December 1956. Its resemblance to every other church bulletin of my time in Gower Street United Church is sufficient to use it confidently as a template to outline the church structures in some detail. I supplement the information from this document with references to materials from the Gower Street United Church archives.

10 Some of the best data I could find about the Gosling Library came from a twenty-first anniversary report (Public Libraries Board, 1957), but information from the founding of the library in 1936 also is relevant. In each case, I attempt to draw on the fullest and liveliest data I could locate for any institution. My report is partial, but it offers some sense of patterns of local intervention in children’s literacy development.

School Systems and Educational Ethos

School

11 My school, Prince of Wales College (the umbrella name for the K–11 system), was founded in 1860 as the Wesleyan Academy, and its Methodist history was an essential element in the school’s proud identity. It was not the only K–11 United Church system in St. John’s; Curtis Academy and Macpherson School had their own structure. However, PWC board members and alumni considered it the elite United Church institution in the province, fully comparable to the city’s top schools in the other denominations. At that time, there was no secular or state educational alternative in the province (see Stanbridge, 2007, and Kim, 1995, for further discussion of the role of denominational education in Newfoundland’s history).

12 The Methodists and their United Church successors always were a minority in Newfoundland. Census figures of denominational breakdown show the Methodists peaking as a percentage of the total population in 1921, when they represented 28.2 per cent of the whole. By 1951, that ratio had dropped to 23.7 per cent and it fell a bit further by 1961 to 21.4 per cent (Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 1988: Table A-5).

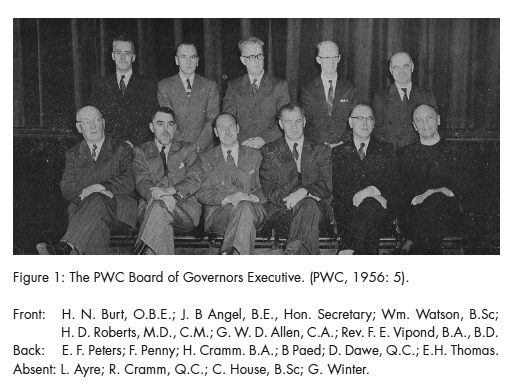

13 United Church priorities affected much of my life and my learning. To take one obvious example, United Church schools were coeducational. Most other education systems in the city separated males and females. The Methodist heritage fostered relatively rigorous expectations about girls’ scholarly achievement. As early as the 1890s, the school’s principal, Robert Edwards Holloway (for whom my elementary school later was named), promoted equal opportunities for girls:

14 My education was affected directly by contemporary decisions, but echoes of such past priorities also inflected aspects of my schooling. It was not a completely straightforward form of equal opportunity. Marilyn Porter, in an excellent study of girls’ schooling in St. John’s just before Confederation, presents a set of contradictions that I certainly recognize as lasting into the 1950s and beyond:

15 The denominational school system was a large element of Newfoundland’s cultural and educational framework, but many smaller details of organization and many local decisions by boards and committees also helped to shape the world of an emergent reader. For example, one or more authoritative bodies selected the Dick and Jane whole-word reading series as the textbooks for learning to read. Children’s education was directly affected by decisions reached by the provincial education department and the school board, and also by the church governance bodies, as well as by the provision of books in library and bookstore.

The Provincial Department of Education

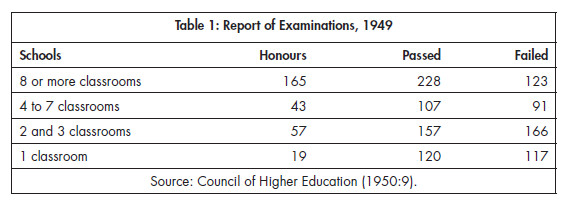

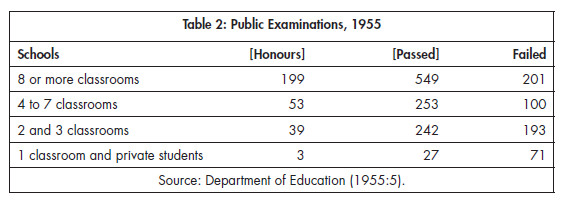

16 Statistics from the year of Confederation demonstrate the scale of the challenge the new province faced in educating its children. The 1949 report on examination results (Table 1) delineates an impoverished system. There was no Grade 12 at this time or for many years thereafter. At the Grade 11 matriculation examinations 1,393 students sat for testing. Of them, 896 passed. The results were broken down according to school size, presenting a portrait that illuminates the educational landscape of the time. Only in the schools with eight or more classrooms did the number passing with honours exceed the number who failed. In the one-room schools, the 117 failures come very close to matching the 120 who succeeded in gaining a simple pass. The achievement of the 19 from one-room schools who earned honours is all the more striking in that setting.

17 I later present the Grade 11 results of one urban school in 1955, so the 1955 provincial figures shown in Table 2 provide useful background information. Unfortunately, there appears to be an error in the headings of the columns in the summary report. Drawing on the more detailed evidence laid out in the report, I have corrected these headings in square brackets.

18 More than twice as many students sat for the exam in 1955 (3,010 as compared to 1,393 in 1949). That tally represents a huge jump in numbers and, undoubtedly, a corresponding doubling of hard work in a very short time span.

19 A note sent from the Deputy Minister of Education to the schools in August 1949 sheds a different kind of light on the challenges facing the education system. He reports on a benefit of Confederation:

Such progress was not completely straightforward, as the following advice shows:

20 A 1958 recruitment leaflet aimed at attracting teachers from Great Britain updates the provincial profile as follows: the province had a total of approximately 1,200 schools, of which 500 were one-room rural schools, with more than 3,250 classrooms serving over 112,000 pupils, a total that was increasing by about 5,000 pupils per year (Department of Education, 1958: 5). Approximately 300 school boards administered these institutions (Department of Education, 1958: 4). Even nine years after Confederation, one-room schools made up 40 per cent of the total.

21 The Department of Education selected textbook options, sometimes recommending books on the basis of school size, sometimes on religious grounds. A full history of school textbook selection before and after Confederation would be fascinating. Memorial University has an extensive historical collection of such texts as well as provincial curriculum documents. To explore such issues as the prevalence of American, British, and Canadian titles, the percentage of text choices based on sectarian options, the pace of change in implementing recommendations, and the degree to which adopted Canadian books were updated to include reference to the entry of Newfoundland to the country would be illuminating.

The School Board

22 While one-room schools are reported as representing about 40 per cent of the province-wide total as late as 1958, school systems in St. John’s were larger and more securely staffed and provisioned. Social differentials undoubtedly applied between school systems; the Board of Governors of PWC represented the professional elite of St. John’s, at least in the United Church segment of the city. A photograph in the 1956 Collegian (Figure 1) shows the executive committee of the Board: 11 men, whose names and degrees are listed below the picture. Four more are absent, but their names and credentials are provided (PWC, 1956: 5). Among them, these 15 men cite seven bachelor’s degrees. There is one medical doctor, one chartered accountant, one minister of religion, two lawyers who had been appointed as Queen’s Counsel, and one holder of an Order of the British Empire. The caption highlights values of social status and accrued cultural capital. Little attention is paid to Board members’ economic status, but no doubt such information would have been part of the implicit knowledge brought to bear on this image by many contemporary readers of the Collegian.

23 I serve as a historical witness in a small way to some of the school board’s activities since my father, Sherburne McCurdy, was the principal of Prince of Wales College (including Holloway and Harrington schools) between 1950 and 1962, the time span of my project. Many faces in this photograph are familiar to me. I recall some of the ways they invested their time and energy into the upkeep of the school system. We lived in a rented apartment on land owned by the school (the Ayre Athletic Grounds on Pennywell Road), and one Board member in particular, H.N. Burt, checked regularly on the state of the soccer pitches and other sporting facilities. H.D. Roberts, a busy medical man who served as chairman, telephoned our house nearly every evening to discuss how the day had gone in school. The secretary of the Board, J.B. Angel, was the man my father phoned early in the morning on potential snow days to decide together whether the schools should shut or stay open in the face of bad weather. In such mundane ways, as well as through official meetings, these prominent citizens took responsibility for the management of the school system in their purview.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1Social and Cultural Capital in the School System

24 That same 1956 Collegian provides the full text of the Principal’s Address at Speech Night, the graduation and prize-giving ceremony, held on 2 November 1955 (McCurdy, 1956). The formal welcomes convey the level of civic investment in the school system, at least on these official occasions. Attendees acknowledged in this address include the Lieutenant-Governor and his wife (Sir Leonard and Lady Outerbridge), the Acting Premier of the province, the Deputy Minister of Education, the head of the United Church Division of the Department of Education, and a representative of the Presbyterian Church in Newfoundland.

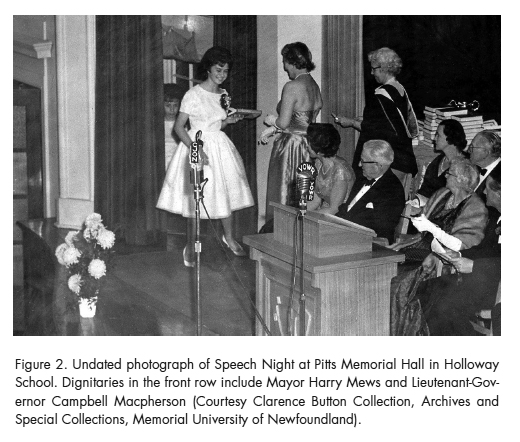

25 A later, undated photograph of a subsequent Speech Night (Figure 2) also manifests a display of social and cultural capital represented by the formal dress of all participants. The furs and the white gloves, the black ties, the academic robes of the vice-principal in the background, and the white frocks and flowers denoting graduating students all make social statements of financial and educational standing unlikely to be replicated in many one-room schools of the province. The stack of prizes and trophies testifies to a complex hierarchy of school successes and rewards. And the microphones of two local radio stations (CJON and VOWR) suggest the local significance of this event.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 226 In contrast to those 500 small outport schools, PWC in 1955 educated a total of 1,365 students in 34 classrooms — a total number not far short of the entire Grade 11 exam-writing cohort in 1949. In June 1955, 39 PWC boys and 35 PWC girls wrote the public examinations; 9 boys and 13 girls took honours; 20 boys and 20 girls passed; 10 boys and 2 girls failed to receive diplomas.

27 Trinity College of Music Examinations also were taken by 45 PWC students (McCurdy, 1956: 98). In addition, the principal’s report makes extensive reference to sports activities and lists cocurricular activities such as the school’s Boy Scout and Girl Guide troops and Cub and Brownie packs. There was a newly formed Traffic Patrol, and 16 students (boys only!) signed on for the first-ever driver safety course. The school presented an operetta in April (“Chonita” with music by Franz Liszt).

28 The principal’s report to his stakeholders also includes reference to a “crucial accommodation problem” (McCurdy, 1956: 97) shortly to be solved by completion of a new building (Harrington School) for approximately 240 pupils in Kindergarten and Grade 1. Even in this flagship school system, some makeshift arrangements were necessary. The principal reported:

29 The report lists and thanks numerous volunteer organizations whose work contributes to the achievements of the school: the Ladies College Aid Society (famous for the November College Sale that raised funds for the school — described on this occasion as “substantial”), the Home and School Association (the parents’ organization), the Old Collegians Association (the alumni society), the Junior College Aid group, and the College Guild. These groups provided such amenities as an intercom system in the Prince of Wales building, new curtains for the stage in the assembly hall, and a party for the graduating class of 1955. The Old Collegians, in particular, were heavily involved in funding and building an arena for the school on the Ayre Athletic Grounds; this facility opened in 1955. Such amenities supported a concept of education that fostered arts and sports as well as academic study.

30 A lively social and managerial network was required to fund and look after this intricate educational structure. Yet, the ultimate mission was not managerial. The principal’s address concludes with these stirring words:

The combination of cultural advantages is unmistakable. The noble goals, the managerial complexity, the multiplicity of volunteer organizations, and the intellectual, cultural, moral, and social capital being accrued by those Newfoundland students schooled at the prosperous end of the public education spectrum helped to establish an elite. The more limited educational offerings elsewhere in the province form a contrasting background of disadvantage to these privileged students. Much was expected of students at this end of the system, yet they (we) developed a strong sense of entitlement.

Church

31 Reading flourished and was fostered beyond the school. The church was another important supporter of particular aspects of literacy.

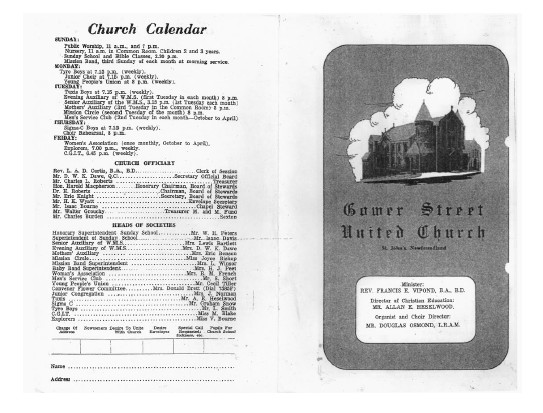

32 The 30 December 1956 Gower Street United Church bulletin provides a wealth of institutional information. It is a single sheet of paper, printed on both sides and folded in half to make a four-page document. Figure 3 presents the outer half of the bulletin. The front never varied unless there was a change of minister; the list on the back page (on the left in this image) was less immutable, but committee members served for at least a year.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 333 This bulletin presents a snapshot of a very busy calendar. At this time, there was one minister at Gower Street, Rev. Francis Vipond; a director of Christian education, Allen Heselwood; and an organist and choir director, Douglas Osmond. All are cited on the front page of the bulletin. The back sheet gives a broader sense of the volunteer work sustaining a lively network of activity. The regular weekly church timetable is outlined on the back page:

- SUNDAY:

- Public Worship, 11 a.m. and 7 p.m.

- Nursery, 11 a.m. in Common Room. Children 2 and 3 years.

- Sunday School and Bible Classes, 2.30 p.m.

- Mission Band, third Sunday of each month at morning service.

- MONDAY:

- Tyro Boys at 7.15 p.m. (weekly).

- Junior Choir at 7.15 p.m. (weekly).

- Young People’s Union at 8 p.m. (weekly).

- TUESDAY:

- Tuxis Boys at 7.15 p.m. (weekly).

- Evening Auxiliary of W.M.S. [Women’s Missionary Society] (first Tuesday in each month) 8 p.m.

- Senior Auxiliary of the W.M.S., 3.15 p.m. (1st Tuesday each month)

- Mothers’ Auxiliary (3rd Tuesday in the Common Room) 8 p.m.

- Mission Circle (second Tuesday of the month) 8 p.m.

- Men’s Service Club (2nd Tuesday in each month — October to April)

- THURSDAY:

- Sigma-C Boys at 7.15 p.m. (weekly).

- Choir Rehearsal, 8 p.m.

- FRIDAY:

- Women’s Association (once monthly, October to April).

- Explorers, 7.00 p.m., weekly.

- C.G.I.T. [Canadian Girls in Training], 6.45 p.m. (weekly).

Thus, some 16 organizations needed participation from the congregation in order to function. The particular news for this week at the end of December, listed on an inside page of the bulletin, adds the Official Board, the Executive of the Christian Education Committee, and the Annual Congregational meeting. Furthermore, five people (all men) served as ushers for that Sunday.

34 The back page lists 28 people (17 of them men) involved in one organization or another. Some single-line entries (such as Sunday school) represent a large number of volunteers. The work of these contributors was not finished when the meetings ended; on page 3 of the bulletin, a note asks all these organizers to submit their annual reports to the Clerk of Session as early as possible in the new year, “so that he may prepare a unified report for the Annual Congregational meeting.” This lengthy list of volunteers and their responsibilities is far from unique; most Protestant churches in the 1950s expected similar lay dedication to running the organization.

35 I invariably attended church on Sunday mornings and Sunday school after dinner. The church service itself presented a very large range of literate discourses: hymns, scripture, announcements, prayers, invocation, and benediction — even the relatively non-ritualistic United Church supplied a variety of liturgical conventions. The church bulletin and the Sunday school leaflet provided each Sunday were fixtures in my reading life and I took completely for granted the human network and the work those people represented.

36 Documents in the church archives include those committee reports solicited in the bulletin. For the most part they are relatively dry accounts of numbers and names, but one intimation of humans at work, making the best decisions they can, lies in this paragraph from the unsigned Sunday school report of 1956:

37 The United Church was a national organization, and further input into church and Sunday school decisions came from Toronto. In addition, there were international connections with Methodist and Presbyterian churches elsewhere. No doubt children in other denominations likewise operated within a context of national and international frameworks. In each case, the actions and judgments of local men and women also affected their literate lives.

The Library System

38 Ruby Gough’s excellent biography of Robert Edwards Holloway, long-time principal of the Methodist College that later became the Prince of Wales complex, includes a succinct summary of “literary and scientific institutes” in nineteenth-century St. John’s.

In short, the city invested in a lively cultural life with an assortment of supportive institutions. But the Athenaeum was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1892 and was not replaced with a civic library in St. John’s until 1936.

39 In the interim, “the only free book-lending service that existed was one that served not St. John’s but the outports, mainly through the schools. Known as the Travelling Library, it was managed by the bureau of Education and largely financed by the Carnegie Corporation of New York” (Public Libraries Board, 1957: 1). Jessie Mifflen, a committed librarian over many of the lean years in Newfoundland, describes the Travelling Library in more detail: “Established in 1924 . . . this service provided an exchange collection of about one hundred books to the communities requesting them, and was of necessity confined to schools, although it was also used by some adult groups and organizations” (Mifflen, 2008: 66).

40 In 1933, the British government established a Royal Commission under the auspices of Lord Amulree to report on the state of the Newfoundland government and the failing economy. Its members commented on the lack of a library in St. John’s:

41 In the face of such official rejection of any kind of government commitment, the development of the Gosling Memorial Library, which opened in 1936 on Duckworth Street, not far from the site of the Athenaeum, clearly took a collective effort by many people. Lorne Bruce describes a ferment of civic activity, led by citizens who may or may not have been stung by the tone of the Amulree Report:

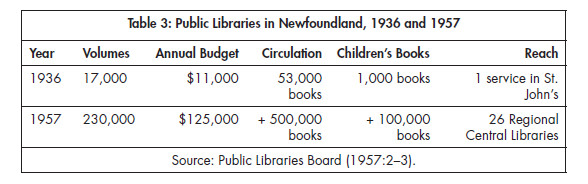

The list of sources for the initial collection bears traces of the efforts needed to assemble it: the private library of a former mayor, donated by his widow; part of the collection of the Legislative Library; 2,000 volumes given by Lord Rothermere; books to the value of $2,000, donated by Sir Edgar Bowring; the 7,000 books of the Travelling Library; and some purchases by the Public Libraries Board (Public Libraries Board, 1957: 2). The Boys and Girls Library seems to have been separate from the outset. Twenty-one years later, the 1957 report on library service in Newfoundland provides some very interesting comparative figures (Table 3).

42 Even with the library’s small collection in 1936, take-up was prompt and substantial when the library opened on 9 January of that year. Paul Sparkes quotes Harold Newell on activities at the new library between January and the end of June 1936. In just under six months, “no fewer than 53,000 ‘borrowings’ had been recorded. And the tally of registered borrowers went over 6,000 in that brief six months” (Sparkes, 2016). The 1936 population of St. John’s stood around 40,000.

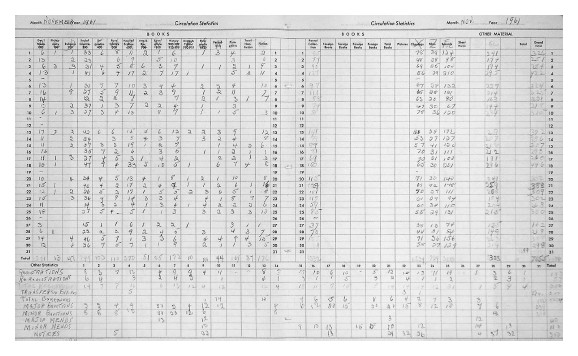

43 A library, of course, is more than its books. During the period of my study, the Gosling Library staff kept meticulous records of their daily transactions. A sample record from November 1961 captures a snapshot of the activity of the Boys and Girls Library (Figure 4).The main grid shows the circulation figures for each day of the month, separated by Dewey headings. Below, “Other Statistics” are gathered, again daily (and again entered by hand): registrations, re-registrations, transfers, and expiries; major and minor questions (presumably reference questions); and major and minor mends.

44 This log records the basic daily work of the library but under-represents other library services. Every November, the Boys and Girls Library featured a children’s book week, for example, but it is not reflected in these statistics.

Display large image of Figure 4

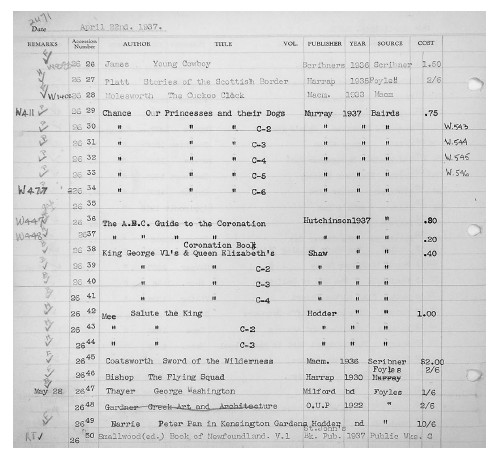

Display large image of Figure 445 The acquisitions register, recording every book ordered, also illuminates a bygone time. Unfortunately, the Boys and Girls Library retained this register only for the years 1936–39. The lists from the earliest days of the Gosling Library are rich with interest. My sample page (Figure 5) offers one small insight into how the Dominion of Newfoundland interacted with larger political and economic entities.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 546 This page presents a conventional acquisitions list. The column headings read: Remarks, Accession Number, Author, Title, Vol., Publisher, Year, Source, and Cost. The Remarks column includes a few numbers but mostly features ticks, presumably indicating that the book had arrived. The range of titles deemed appropriate for the boys and girls of 1937 skews British on this page, in part because of separate entries for each of six copies of Our Princesses and Their Dogs, four copies of King George VI’s and Queen Elizabeth’s Coronation Book, three copies of Salute the King, and two of The A.B.C. Guide to the Coronation. One book is about George Washington, and a copy of Smallwood’s Book of Newfoundland appears at the bottom of the page.

47 The price column is intriguing. The listed currency fluctuates between dollars and cents and shillings and pence. It is not clear whether the dollars are American or Canadian or a mix of both. Alternatively, since many of the dollar entries go to Bairds, a local importer, we may also be looking at Newfoundland dollars. Smallwood’s book is listed as a gift. It is worth noting that the charge for all the books about the royal family is paid in dollars, while the George Washington book comes from Foyles in London at a price of 1/6.

48 These documents reveal an orderly work world where numerous decisions were made and recorded, reflecting a clear mandate to support the reading habits of the children of St. John’s, whether in 1937, 1957, or 1961. The acquisitions records conclude long before my time as a library user, but in my perusal of their pages I did occasionally catch sight of a title I knew I had read as a child — very likely the same copy. I could read that specific book because somebody made an explicit decision to purchase it. It is a sad loss that later acquisitions information is no longer available.

Other Literacy Support Structures

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6Brownies and Guides

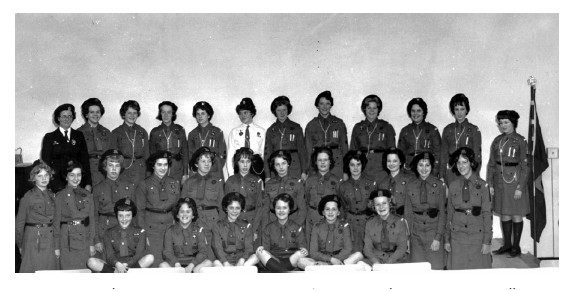

49 Between the ages of 8 and 13, I was a Brownie and a Girl Guide. The photograph above (Figure 6) shows my Guide Company in 1961 or 1962; I am third from the left in the back row. The Guide Captain had been my Kindergarten teacher and Guide meetings took place in the Kindergarten classroom of the new Harrington School.

50 This picture could serve as a manifesto for the significance of implicit literate understanding. The girls in the back row display extra insignia — stripes on the pockets of their uniform dress to signify that they are a patrol leader or a second-in command; lanyards to communicate status and prowess. Where a girl’s arm in that back row can be seen, it sports achievement badges, an addition conspicuously missing on the more visible sleeves of the younger girls in the front row. The sense of hierarchy is imposing, as no doubt it was intended to be.

51 My mother saved my Brownie membership card, and it displays a “Brownie literacy” that was orderly and cumulative. Achievements leading to a Golden Bar were enhanced for the greater glory of a Golden Hand. The requirements for badges were spelled out carefully; a committee somewhere decided what criteria were satisfactory. Literacy requirements simply taken for granted included reading the Brownie handbook and mastering the specifications for badges (and some badges acknowledged reading activities explicitly). Local Brown Owls (adult leaders of the Brownies), Guiders, and Commissioners organized the local scene, according to protocols laid down nationally and internationally. During my time as a Girl Guide, in September 1961, Olave, Lady Baden-Powell visited St. John’s, to be greeted by an enormous rally, which must have absorbed many voluntary committee hours to organize.

52 My mother was a Guide Commissioner during the 1950s, and, along with the girls in her charge, donned her own uniform for any formal occasion. The Guiding organization was hierarchical from bottom to top; and its allegiance to the virtues of uniforms ran through all levels. Rituals of who wore what and on which occasion, protocols of salutes and handshakes, recognition of degrees of seniority made clear to the rawest novice Brownie — to belong to the Brownie world, a child had to master them all in an exercise of reading both words and symbols that was simultaneously abstract and embodied.

Literate Invitations in the Larger Environment

53 Many other literacy institutions contributed to my life. Newspapers and radio and then television programs, for example, all fed my developing understanding of the wider world. Each of these formats mixed local and global ingredients. There is not space here to develop a detailed account of the kinds of active decision-making that went into their daily impact on the lives of the people of St. John’s, but they did not materialize by accident or out of any kind of cosmic necessity. They were designed and instantiated on purpose, and the decisions made by their creators inflected how I understood the wider world.

54 A consolidated history of the institutions conveying information and entertainment to Newfoundlanders would make for very rewarding reading. Fragments of that history are currently available and they provide fascinating insights (see, for example, Moore [2007] on early films in Newfoundland, Webb [2008] on pre-Confederation radio service in Newfoundland, and Riggs [2005] on the history of Dicks, the bookstore).

55 Other institutions were shifting the literacy landscape in Newfoundland in different ways that affected children rather more indirectly. Gillespie (2016) discusses the impact of union organization on Newfoundland society over many decades, including the period I have examined. Webb (2016) outlines the development of different disciplinary approaches to the academic study of Newfoundland culture and economics. Such developments contributed to shifts in the tacit literacy climate of Newfoundland society. During the time I have considered — 1950–62 — the changes were nascent, inchoate. By the time of the centennial year of 1967 that Barker regards as an important turning point in the history of Newfoundland literacy, conditions were in place for the explosion of cultural self-expression that now distinguishes Newfoundland society.

56 Conditions of literacy are complex, and much more is out of sight and hidden in depths than cannot be perceived except with mindful and focused inspection. In order to reflect on the scale of such a story of literacy, I conclude with a singular, telling example: some elements of the history of one book that came into our family’s possession in 1957.

Local and Abstract: A Final Example

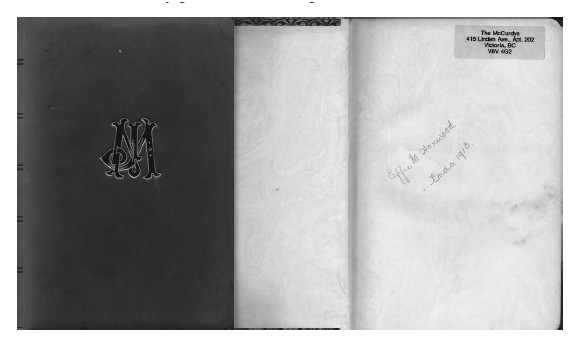

57 The paper book, with its coded marks on the page and its particular history as an object owned and shared by readers, moves in and out of local life while representing something broader in terms of time and space. To sum up the complexity of the book and its readers and the unseen efforts of the people who make that reading possible, I take one small example of a book currently located in my home in Edmonton, Alberta. Titled Milton’s Poetical Works on the spine, with a slightly longer wording on the title page, it is bound in a thick layer of handsome purple plush, now somewhat faded. The front cover, shown in Figure 7, is embossed with a “JM” monogram. On the endpaper are two names: written in pencil, “Effie M. Horwood Xmas 1913”; and, on a sticker adhering to the top corner, “The McCurdys,” followed by an address that was my parents’ last independent home in Victoria, BC.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 758 From 1910 until her sudden death in 1957, Effie Horwood taught in the school system eventually known as Prince of Wales College. She had been a student in the Methodist College from 1896 onward and she trained as a teacher in the same institution. Overall, her connection with the school lasted 61 of her 67 years.

59 Miss Horwood left two books of poetry to my father, who then was the principal of Prince of Wales. The second was an equally sumptuous leather-bound copy of Tennyson’s poetry, signed by her in 1908. I inherited those books from him. The Milton volume contained clippings of two different newspaper obituaries of Effie Horwood, cut tight around the text and with no provenance provided. One of them comments that she was educated “at the Old Methodist College, Long’s Hill, under Dr. Holloway and Mr. Harrington” (source unknown).

60 Gough’s biography of Robert Holloway provides the further information that he, as a pupil teacher at the Wesleyan Training College in England, had his classes inspected by Matthew Arnold, who he remembered well. Arnold “praised the staff for their efforts to diversify the curriculum and to provide for the pupils’ individual needs. . . . Mat-thew Arnold envisaged universal compulsory education as a way of producing cultured citizens of a new democracy” (Gough, 2005: 14).

61 This Oxford edition of Milton’s poetry, published in London in 1912 and purchased by or for Effie Horwood in 1913, offers an embodied example of the local and the larger world, all in a single object that can be held in the hand. Miss Horwood did not provide a location with her signature on the flyleaf, but she was already teaching at the Methodist College on Long’s Hill in 1913, so the book existed in St. John’s and was very possibly purchased there as well. The book presents an authoritative version of the works of one of the greatest poets of the English language, a man who lived between 1608 and 1674, and who was himself a robust champion of the significance of reading and the rights of readers (Aereopagitica, 1644). The Preface to my volume says, “This edition of Milton’s Poetry is a reprint, as careful as Editors and Printers have been able to make it, from the earliest printed copies of the several poems” (Beeching, 1912: v). The earliest poems in the volume are reproduced from a book first published in 1645.

62 Miss Horwood (1890–1957) lived — and presumably looked at this book — in St. John’s, and her personal history invokes a chain of connection back to Robert Holloway (1850–1904), an educator of high esteem whose impact on Methodist education in Newfoundland still resonated in my lifetime. Through Holloway, we can follow that chain back, away from the Dominion to the “mother country” and the educational inspiration of Matthew Arnold (1822–1888), poet and inspector of schools. After 1957, the book lived in a place of honour on my parents’ bedroom mantelpiece on Pennywell Road. It ultimately moved with them, first to Edmonton, and then to Victoria, and has now returned to Edmonton with me.

63 The obituaries of Effie Horwood make some associations explicit that, otherwise, I would not have been able to articulate — but those associations belong to the book, whatever its current owner’s awareness may be. This grand little volume reaches from the twenty-first century back to the seventeenth. It belongs to St. John’s and it belongs to the large world of arts and letters, both at the same time. Its plush covers manifest a certain attitude to learning and poetry redolent of a different era. It stands as a physical connection to a very particular historical sequence of events and priorities in the history of Methodist and, then, United Church education in St. John’s. And, for me, it brings back strong personal memories of that bedroom mantelpiece on Pennywell Road, where my parents displayed a small set of especially valued books. It is a memory that incorporates a distinctive attitude to education that permeated my home as well as my school. In addition, the name-and-address label on the endpaper vividly reminds me of the apartment in Victoria that my parents occupied in a late stage of their lives.

64 I elaborate on the resonances of this single artifact because I think this story, so insignificant in many ways, encompasses many of the aspects of literate development that I have attempted to describe in this article. The decisions and actions of four dedicated educators (Mat-thew Arnold, Robert Holloway, Effie Horwood, and my own father [1924–2007]) are linked to this object through associations that are relatively easy to establish and that adhere to the book as a physical object containing two distinctive marks of ownership. In a different way, the contents of the book connect to a great seventeenth-century thinker and poet, whose ideas crossed the world of his time and travelled as far as the Dominion of Newfoundland. Somewhere, possibly at Dicks on Water Street, a bookseller acquired this title and made it available for sale.

65 As a child, I was hugely impressed by the lavishness of this volume, and curious enough to look inside — though I cannot say I was won over to Milton’s poetical diction at the age of nine. I was, of course, oblivious to how it might be possible to focus, through the material existence and historical aura of this single book, on so many manifestations of active engagement of human beings committed to enabling literacy. But even as a nine-year-old, I was vaguely aware that this plush hardback connected me to a larger and grander world, and that reading was the key to entering that world. The book links Pennywell Road in 1957 to the building then known as Holloway School on Long’s Hill, all the way back to 1896, and to the educational values and efforts of people like Matthew Arnold even further back in the nineteenth century. It incarnates the words of Milton from as early as 1645, edited with care and attention in 1912, and its portability meant it could cross the Atlantic Ocean and then the full breadth of Canada. It has a global history and a local provenance.

66 My copy of this book is one kind of private legacy of the efforts to support literacy in the 1950s — a legacy that at once looks backwards and outwards from the mantelpiece on Pennywell Road. Another inheritance from that era is more public. Just as bringing Milton to Newfoundland involved specific efforts and decisions, so the educational work done in the 1950s led to the explosion of artistic representations of the city and the province that followed improved federal funding after 1967. Many contemporary Newfoundland novelists, poets, artists, playwrights, satirists, filmmakers, and musicians similarly benefited from the care and attention of numerous boards and committees, volunteers and professionals, working hard through the 1950s to turn the assets of Confederation to the advantage of the new province’s children. Today, these artists represent Newfoundland and Labrador to the world, and to the citizens of this province. When I think about the blank spaces of the 1950s where descriptions of my own world should have flourished, and then look at the contrasting wealth of representation available today, I value the genius and creativity of the creators, but I also acknowledge the debt of gratitude owed to their elders and mentors who made such efforts to scaffold better forms of learning.

Conclusion

67 Of course, in 2017 decisions continue to be both necessary and consequential. As I write these words, questions about the library service are under consideration; a new tax has been placed on books; and an education task force has just reported. Stasis is not an option. New decisions will be deliberated, implemented, resisted, and enacted. Today’s volunteers continue to work within frameworks established by larger groups, both lay and professional. And in the midst of this world of often invisible, unheralded labour, both local and distant, today’s children are learning to read.

I would like to thank Susan Kearsey for her substantial help in locating some of the papers that inform this article and I acknowledge my great debt to Linda White of Archives and Special Collections at Memorial University of Newfoundland. All errors and omissions, of course, are my own.