Articles

Stephen and Florence Tasker and Unromantic Labrador

Introduction

1 For over a hundred years, the story of Stephen and Florence Tasker’s 1906 expedition has been of little service to Labrador culture and criticism. This is strange, given that celebrated guide George Elson was involved,1 but on the other hand the story’s themes and details do little to confirm prevailing ideas of regional identity, and Labrador’s literary canon has only recently begun to expand beyond the task of identity formation. As readership practices mature and the canon’s needs change, stories like the Taskers’ become more useful, even necessary. At the same time, the Taskers’ 1906 photo album has happily made its way into the archives at Memorial University Libraries, prompting new research that gives us the chance to understand them in ways we never have before.

2 The album documents a journey also retold in the periodicals of the day: a circumscription of the Labrador Peninsula from Missanabie, Ontario, through James and Hudson Bays, across Ungava by paddle and portage, then along the coast to Cartwright and St. John’s, and back by rail and ferry to Ontario. The adventure narrative itself would find an audience today, with illustrations and a selection of news sources to choose from, but greater value is to be found in the Taskers’ prose, which is forthright, vigorous, and startling, both in its content and in its variety. In fact, taken together, Stephen’s and Florence’s short works do not merely supplement a reading list, but actually uncover an alternative view of Labrador: a view like a bugbear, which always haunts us but is seldom seen.

3 Almost alone among their contemporaries, the Taskers do not immediately find romance on the peninsula.2 Rather, they discover what the cynics within us fear: that a landscape may be desolate without being sublime, and that poverty, hardship, and isolation do not inevitably ennoble a society. Stephen in particular longed to believe in the romance of Labrador and the North, pursuing it throughout his life in travels and in writing spanning 30 years. He may have eventually persuaded himself, but while literary Labrador is usually either a land accursed by God or a sacred homeland and inviolable trust,3 the Taskers initially depict it merely as a disappointment. For them, the barrens do not partake of grand themes: they are barren of theme itself.

4 To brush aside accounts like these is to neglect an opportunity. Stephen is obviously sincere, and his Progressive Era prejudice and naive privilege make it more likely for him to idealize Labrador, not less — as demonstrated by his contemporaries and his own gradual reformation from a detractor to a celebrant of Labrador. Florence is a different case, but reading her alongside her husband contextualizes the stark contrast between her account of the Labrador trip and her previous writing. The more we read the Taskers’ output, the more we realize that their understanding of Labrador is not at issue; rather, it is our own. We do not read the young, wealthy, Philadelphian couple to learn about Labrador: we read them to learn about our own assumptions about the region. By challenging the empirical basis for a romantic Labrador, which is our most dominant literary theme, the Taskers help us realize that we may be better off dismantling the idea than defending it.

Explorers of Leisure

5 Stephen and Florence Tasker are best understood in the company of Leonidas and Mina Hubbard, Dillon Wallace, William Brooks Cabot, and Hesketh Prichard. These seven middle-class white explorers all first set foot on the peninsula between 1903 and 1906, seeking adventure. Each had romantic ideas and literary leanings, but their defining characteristic is that none had a strong professional imperative to be in Labrador. They were mainly urban professionals4 attracted by the mystique of Labrador’s land and people, as stirred up in the American Northeast and England by the lecture tours and reputation of medical missionary Wilfred Grenfell. They were also individually inclined to write and, moreover, to pursue in their writing what W.S. Wallace identified in John McLean’s earlier Hudson’s Bay Company (hereafter HBC) memoir as a “literature of power”5 — a thing seldom encountered in Labrador, except in these seven explorers, without attachment to some obvious commercial or socio-political end.

6 In short, the Taskers and their peers were tourists and travel writers, though “explorers of leisure” comes nearer the flavour of Peter Armitage’s apt but gendered term, “gentleman explorer.”6 The key qualification for this group of adventurers is the absence of a straightforward, personal motive,7 but charter membership is laid out by name in Prichard’s Through Trackless Labrador (xiii) and repeated almost exactly by Cabot, who omits only Prichard himself (11).8

7 The idea of making a trip through Labrador’s interior was to distinguish oneself as an outdoorsman while adding to the extant body of knowledge about the country, either by ethnographic and environmental observation, or by cartography. It was also important to accomplish something new, though despite various representations to the contrary, none of the seven was truly the first non-Indigenous person to traverse a particular route or territory. For their part, unlike the Hubbards and Wallace, who fancied themselves discoverers despite the precedence even of white explorers,9 the Taskers seem to have accepted the reality of their tourist status. Far from reducing the ambitiousness of their purpose, this attitude merely better prepared them to accomplish it. In such circumstances, humility and daring are often false opposites — much as Mina Hubbard herself showed by arranging a superior expedition to her husband’s and Wallace’s, simply by deferring to expertise.

8 Likewise, the Taskers prepared their expedition well and responded to emerging facts, modifying their intended route as necessary. Throughout their time in the country they accepted risk without courting it, and dallied neither for curiosity nor for inclement weather (S. Tasker, “Northwestern Labrador” 91). They had no intention of venturing their lives upon an uncertain goal, and detailed accounts of the expedition display prudence and pragmatism. On the homeward journey, Stephen told the Evening Telegram in St. John’s that the trip had been “purely one of pleasure, to see the Labrador and its people” (“1500 Miles”). This alone marks the Taskers as among the most self-aware of the group; of the others, only Cabot might have uttered such a thing.

9 Stephen and Florence were already experienced canoeists and hunters when they went to Labrador in 1906. Stephen was 31, Florence six years younger to the day. Both were of well-heeled Pennsylvania stock, with Stephen descending from engineers and businessmen, including most prominently his great-grandfather, Thomas T. Tasker, while Florence’s father was Civil War telegrapher William Applebaugh and her grandfather was a physician. The couple was married in August 1901, about the same time that Stephen settled a legal dispute surrounding his inheritance from his great-uncle and namesake, Stephen P.M. Tasker, Sr., so from the beginning they had sufficient wealth and freedom to pursue an enthusiasm for outdoor adventure.

10 Stephen seems to have been the principal instigator of their trips, but Florence was an active partner and reportedly a good shot, as well as the one to write up their early adventures in moose-hunting for Field and Stream. She had prominence and charisma of her own as well, being deemed by the newspapers “well known socially among the University set” (“Woman Explorer”) and “One of this city’s pluckiest and prettiest young society women” (“Woman Conquers”).

11 Stephen’s professional trajectory was set by his name: even the middle initials “P.M.” stood for family business partners, as in the Pascal Ironworks and Morris, Tasker, & Co. He was educated first at the Episcopal Academy boys’ school and then at the University of Pennsylvania, where he studied engineering and learned navigation and astronomy. He specialized in marine equipment, like his uncle, who had patented armoured diving suits (Vorosmarti), and by 1906 he was a U.S. Navy inspector at Cramp’s Shipyard in Philadelphia. He would spend most of his professional life in that position, though he did keep other business premises at least briefly, with partner William J. Strawbridge, who died in 1911.

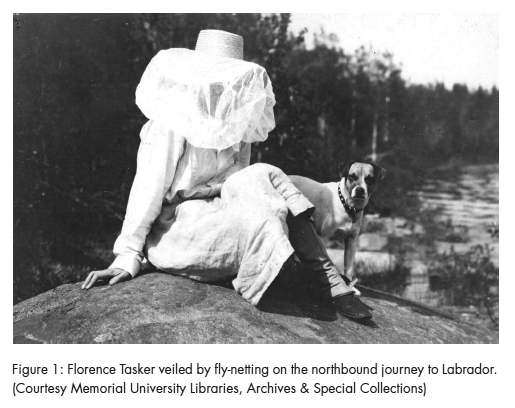

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 112 Stephen’s personal and professional interest in watercraft — showcased early in a 1903 article on “The Steamship of the Future” for International Marine Engineering — was first communicated to Florence in a practical way in 1904, when she stepped into a canoe for the first time and the two of them paddled together on a six-week guided moose hunt in northern Ontario. Florence, who at that point “had never been nearer camping than a Sunday-school picnic” (“White Squaw” 442), seems to have relished nearly every aspect of the experience, lamenting the expedition as all too brief, praising the honesty and industry of their native guides, minimizing all difficulties and inconveniences, and rhapsodizing over the beauty of the landscape, culminating in a passage about the moon showing “such a glorious radiance as only God Himself could make, and in God’s own country” (445). Her entire account has an air of romantic revelation, and the main lesson she draws from the expedition is given in the first two words, which are also the final two — “Go along” — an exhortation to women to accompany their husbands on outdoor travels, instead of remaining at home.

13 Having paddled Canada’s northern woods and belonging to the Canadian Camp organization, the Taskers must have imagined themselves in the milieu of contemporary best-sellers like Norman Duncan’s Doctor Luke of the Labrador and Wallace’s Lure of the Labrador Wild. Indeed, the Taskers soon did step into that world, when by chance they met Wilfred Grenfell (the basis for Doctor Luke) in Cartwright, and he gave them a letter of introduction to the Governor of Newfoundland (Evening Herald, 18 Oct. 1906). Hubbard’s and Wallace’s “lure” drew the Taskers too, more directly; Mina Hub-bard’s 1905 quest to reach the George River provided not only the precedent of a society woman daring the Labrador wilderness, but also the template for a successful trip, and even the very guides to employ, in the persons of George Elson and Job Chapies. Florence’s account of the 1906 journey explicitly sets out Hubbard’s precedence “in a record-breaking trip” (“Woman through Husky-Land” 823), and Stephen remarks, “you would have to know [Mina] as we do, to appreciate her charm and courage” (Steve Patrols More Territory 46).

“All Well”

14 The Taskers are more obscure than their peers partly because whereas the Hubbard, Wallace, Cabot, and Prichard expeditions all produced book-length narratives within a few years, at first Stephen and Florence settled for one magazine article apiece. Stephen also promptly mined his Labrador experiences in articles on watercraft and navigation, but neither he nor Florence would publish further on the expedition itself, or produce any book-length work at all, for more than two decades, until Stephen finally self-published three slim volumes of fables, reminiscences, and essays. Even then there was no distribution network for the printed story. Stephen had neither a publisher nor financial interest in disseminating copies.

15 More importantly in a local context, the market for Labrador literature was not significant until the 1970s. Therefore the public imagination had to be captured through other means than print. Wallace and the Hubbards are remembered in North West River not because of their publications, but because the community actually participated in the story itself. Not only did their expeditions set off from the post, but in 1903, local men rescued Wallace and retrieved Leonidas’s body, and in 1905 Gilbert Blake accompanied Mina as a guide. That participation naturalized the story first as local, and then inevitably as Labradorian, by virtue of North West River’s position at the centre of the Pearl River to Mud Lake crescent where the dominant Labrador literary tradition arose.10 Books may have won Wallace and Mina Hubbard their American public, but their Labrador public had to be prepared and maintained locally for memory and interest to survive the decades until print culture came of age in Labrador, and reprints and retellings appeared to bolster the story in a cultural environment where the interior trapper myth was being cemented as the foundation of a Labradorian political/cultural identity. 11

16 The Taskers, by contrast, never entered Lake Melville. They came down the Labrador coast, but their adventures were primarily in Ungava, a place historically called Labrador, but one remote from the experiences of most people in present-day Labrador. Thus the Taskers made no lasting impression on those they met on the Atlantic coast — a fact that would scarcely matter to audiences in Philadelphia and New York, but that, in a local context, raises the question of which public the story really ought to belong to. Its physical geography is mainly in modern Quebec, but its natural discourse community is clearly Labradorian.

17 The two primary sources on the Tasker expedition are Florence’s article in 1908 and Stephen’s in 1909, but the Taskers’ public presentation of Labrador began with a short telegram sent from Domino, on Labrador’s southeast coast, via Cape Race to Philadelphia. Sent by Stephen, as reported by various newspapers, it reads in its entirety, “Crossed northern Labrador with wife from Hudson Bay. All well.” When these 10 words reached the Philadelphia bureau of the Associated Press, all manner of fantasy was promptly appended.12

18 The immediate press dispatch out of Philadelphia reported that the Taskers were honeymooners who had nearly starved in the interior, being obliged to eat their sled dogs before ultimately being rescued by locals. St. John’s journalist W.J. Carroll later issued a correction for Forest and Stream, blaming “the fertile brain of some Philadelphia scribe,” but editors across the continent exercised a wilful blindness in running with the story, especially given the lack of a plausible source for any of the details and the unlikelihood of travelling by dogsled in the summer. The point to emphasize here is that initial reports appealed extravagantly to the two universal literary themes, love and death: the trip was repositioned as a honeymoon to accentuate its romance, and peril was introduced to increase its poignancy. Presumed reader interest lay not in depictions of the lands or societies encountered, but in the comic or tragic trajectory of the protagonists. In much the same way, The Lure of the Labrador Wild sold well largely because of Leonidas Hubbard’s death, and Mina Hubbard’s story is made more compelling in many versions by the supposition of a love affair with George Elson.13

19 More original articles soon appeared anticipating the Taskers’ return to Philadelphia, as reporters covered the preparations for their welcome or interviewed their families and friends for biographical sketches. Stephen’s mother and stepfather were interviewed by the Public Ledger in Philadelphia, and the Evening World spoke with Stephen’s astronomy professor and his wife, who planned to host a reception for the homecoming adventurers and supplied laudatory background details, particularly on Florence. The Evening World, like most of the news briefs and longer articles, particularly fixated on Florence`s gender, claiming that, “perfect in health and strength [she had] accomplished what no other woman had done,” while repeating the frequent calumny that the 1905 Hubbard expedition had failed (“Woman Explorer”). Likewise, The Washington Times profiled Florence’s character under the headline, “Woman Conquers Labrador Wilds.”

20 The Labrador telegram had been received in Philadelphia on 4 October, a Thursday, and all of these articles appeared either the next day or on the following Monday. Thereafter, reports trickled across the United States, mostly without new material, except when a few weeks later the McCook Tribune of Nebraska ventured otherwise unattested biographical details and a drawing of Florence “in arctic costume,” which may be fanciful, but coincides with other mentions of her posing at the Taskers’ June departure in heavy furs not actually intended for use on the expedition (“Adventurous Trips”).

21 The Taskers themselves were ignorant of all this until their 17 October arrival in St. John’s aboard the Virginia Lake mail boat from Cartwright. Stephen’s indignation sparked an amusing exchange between the Herald, which had repeated the Philadelphia dispatch just the day before, anticipating the Taskers’ arrival, and the Evening Telegram, which immediately secured an interview with Stephen to set the record of the expedition straight. This prompted a defensive correction from the Herald on 18 October, in which the editor relates actually showing Stephen a copy of the report from Philadelphia and cites his laughter as absolution for the false report. Of course, mainstream journalism was more a confidence game then than today, but approaches to accuracy and authority always affect stories’ pathways to public acceptance. Context is also crucial, and a story intended for ephemerality in a media-saturated American culture is not likely to be well suited to the literary-historical record in Labrador, where even today authenticity is the foremost criterion for a story’s value.14

22 So much from a 10-word telegram. A month later Stephen spoke publicly to an American audience on the expedition, addressing the 13 November annual Canadian Camp dinner in New York on the topic, “Impressions of Labrador.” There, as The Sun colourfully summarizes:

23 [He] advised the Campers to keep away from Labrador and told them that the country wasn’t even good enough to die in. “It was a disappointment from start to finish,” said Mr. Tasker. “It furnishes no appeal for sportsmen. All the time I was there I saw only a few white fox, a single caribou and a few ptarmigan. It is, perhaps, the most miserable place in the world.” (“Had Wild Boar”)

24 This “decidedly unfavorable” opinion, as the New York Tribune puts it (“Canadians”), contributes to a long-standing tradition of quips about Labrador’s barrenness. More in the same vein would follow, particularly from Florence, before the initial disappointment was to fade and intellectual romanticism would take over Stephen’s prose, but even two months after their return, in a syndicated brief apparently first published on 7 January 1907, Stephen’s perspective seems to have softened: “‘Those wild regions,’ said Mr. Tasker, smiling, ‘made hardly an appropriate place for a quiet married pair to visit on a pleasure trip. Still, everything came out well in the end’” (“Anecdotes”).

“Through Husky-Land”

25 Almost lost amid the journalistic fanfare is the one actual detailed report of the expedition to appear with any promptness. Surprisingly, it comes not from the Taskers, but from George Elson, via interviewer L.O. Armstrong in Montreal, writing to Forest and Stream. This is exceptional for a Native guide in 1906, and a measure of Elson’s status — indeed, Armstrong does not even racialize him, whereas his colleague Job Chapies is left anonymous and noted merely as “an Indian guide” rounding out the party’s number.15 Similarly, in 1908 Florence devotes a full paragraph to Elson, of whom “Almost everyone had heard,” and follows that with the terse, “Our other man was Job Chappies [sic], a full-blooded Cree” (“A Woman through Husky-Land” 823–24). Elsewhere, Chapies is seldom mentioned at all. The omission makes sense in a way, since the story is inherently about white people traversing Labrador — but it does problematize the treatment of Elson’s own Cree-Scot background.

26 As one might expect, Elson’s account mostly focuses on details of the route taken. It is considerably more precise in this respect than the longer, more formal pieces written by the Taskers themselves. Elson mostly steers clear of generalities and personal impressions, but does offer a few remarks, all positive, noting that the Taskers are both “keen lovers of sport” and “good canoeists”; that the “scenery is bold and very beautiful” and “looks like the pictures of some of the Scotch lochs”; and that “The Eskimo are very quiet, honest people” (Armstrong). This version of the story, mediated by Armstrong, is much closer to the Labradorian mode. Place names are evoked constantly, specific quantitative measures are often given for distances and travel times, and overall impressions are given only briefly, whereas practical observations are occasionally allotted unusual detail. Elson provides an estimate of the draft of the HBC steamer Inenew, for instance, but does not give its name. Similarly, he notes which kinds of trout can be found in which rivers, and takes pains to clarify the distinction between going up the Clear Water River directly or preferring a short distance of the Washatune first.

27 Florence’s article is of an entirely different character. It was the first formal written account of the expedition, and did not appear until the February and March 1908 issues of Field and Stream. Her storytelling flair, and desire to evoke Wallace’s “literature of power,” is evident from the opening paragraph:

28 Also evident from the very beginning is the transformation in Florence’s outlook since 1904, when she urged women to “Go along.”

29 The whole story is told in absorbing fashion, with tendencies to aphorism and hyperbole, and frequent character sketches and summative judgements. Florence does rattle off the customary catalogue of gear, and cites distances and time frames now and again, but her two focuses are the emotional experience of the journey and the characters of the people encountered. Thus young railroad surveyors become “the most forlorn specimens of young manhood I ever hope to see,” who throw up their hands and howl upon learning that the Taskers are on a pleasure trip (824); “shy, comely squaws” at Moose Factory dance to fiddle music on “soft moccasined feet” (825); and we are given descriptions of the slates, pencils, and classroom maps used by the Episcopalian schoolmaster there. Once the expedition enters deeper wilderness, the description shifts to tales of mosquitoes thick enough to snuff candles and drum on tents like rain, and to alders and willows that “wrapped their outstretched arms so clingingly” about Florence on a portage (937). Still, each Indigenous group encountered on the land is separately depicted, usually in unflattering terms or open disparagement, but always with sensitivity to specific sensorial detail. The attention returns to more balanced caricature once Fort Chimo (Kuujjuaq in Arctic Quebec) is obtained.

30 Throughout, the story is one of vignettes, each fresh and independent of the others, so that tone and judgement are always frank and situational. Any delight Florence expresses is patently genuine, and any condemnation or complaint is specific to the encounter. This is not to sanitize — she is unabashedly racist towards those with whom she has no lasting contact. Thus she speaks well of George Elson, who is “willing, kind and faithful,” competent and good-natured with “his quaint tales, and quainter way of telling them” (939), and Job Chapies is a capable guide and bowsman, and no ill is spoken of others who assisted the Taskers in this expedition or on the 1904 moose hunt. But otherwise she is quick to scorn almost every Indigenous person she encounters.

31 As noted, her observations are always particular, and no consistent impression is offered of the society. Rather, Florence’s writing highlights the diversity of experience over the distance travelled. This quality is partially what redeems the prose as valuable today, because it constructs an episodic narrative that invites reader experience and interpretation. It demonstrates the legitimacy of Florence’s remarks, not as truths, but as authentic and individual impressions. Further, the way she presents these impressions, with a deliberate pathos, moves the piece from the realm of mere information into literature.

32 Despite a few synoptic comments on the physical landscape, for instance speculating that God must have made Labrador “in the evening of the sixth day” (828), it is only at the very end of the article that Florence returns to the basic thesis of her opening. She closes by vowing never to leave the United States again and praying for the “strength and wisdom” to refuse any further expeditions that Stephen might plan (943).

33 Stephen’s own published account of the Labrador trip is curious in several respects. To begin with, his motivation for writing is unclear: perhaps he simply felt that Florence had left too much unsaid about the geography, for his version makes no attempt at liveliness and adds nothing of narrative interest. It is not really even a story. His article was also published a year later, offering a detached perspective on the ground covered, as if to outline what a future traveller ought to bear in mind. He begins with a general introduction to “Northwestern Labrador,” and does not even mention his own trip until the closing clause of the second paragraph. Thereafter, he all but removes himself and Florence from the narrative, and does not mention Elson or Chapies. In his account the expedition begins in Great Whale River, without context or preamble, and has no clear terminus, giving the impression that for Stephen the narrative process is less one of tracing a journey to its destination than of filling in a gazetteer.

34 Here and there, turns of phrase echoed from Florence evoke a shared recollection as well as a shared experience, but if Stephen’s article were the only version of the story, then forgetting it would be altogether justified. Where Florence presents vignettes, he either omits incidents altogether or cites them only to illustrate points about the social and physical obstacles of the journey. The contrast with Stephen’s highly sentimental and literary work later in life is equally stark, and therefore perhaps the 1909 piece is best read as the work of a young man, a naval officer and engineer, still overly committed to masculine decorum and the restraint of self-disclosure, if not of imagination generally.

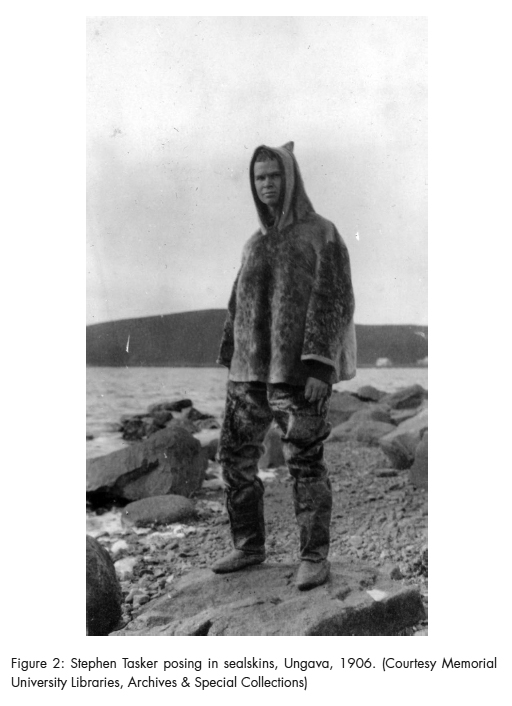

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 235 Some hints of a tamped-down enthusiasm do lurk within the text, which other readings substantiate. For example, the most descriptive passage in the article is devoted to Native canoes and the advantages and drawbacks of their designs. This seems out of place until one remembers that Stephen was a marine engineer. In fact, his first publication after returning from Labrador was not the expedition account, but a June 1907 article for International Marine Engineering (IME) entitled “Eskimo and Indian Boats of Labrador,” wherein he describes the canoe, kayak, and oomiak in intimate technical and anthropological detail, without ever noting that he has been to Labrador.

36 Another passage repeats Florence’s description of mosquitoes thick enough to smother candles, but Stephen goes on to explain that the reason for the flames was to light his artificial horizon each night, allowing him to calculate latitude and longitude based on the stars. This interest resulted in “Navigation by Celestial Observation,” a three-part 1907 article, also for IME, in which Stephen outlines his whole process, from the procurement of equipment to the final analysis, using for an example observations he took at Fort Chimo during the expedition. His final result, he claims, is precise within a quarter-mile.

37 If the twin arenas of our explorers of leisure were outdoorsmanship and learning, Stephen’s priority in writing is certainly the latter. Nonetheless, sport is the only topic on which the 1909 article is anything approaching effusive. Stephen’s salmon are “magnifi-cent,” his trout are “monsters,” in some rivers the fishing “could not be better,” and his disappointment at the lack of caribou is keen. In fact, he devotes whole paragraphs to caribou, after an expedition on which only a single juvenile animal was encountered. This focus reflects his interests, the purpose of the trip, and the audience of the article and magazine, but it also represents a thematic contradiction for Stephen as a writer, because it does not reflect the parts of his Labrador experience that genuinely moved him. Those parts would stay with him for years to come, and their emergence in his prose would be postponed until they had become the reminiscences of an older man.

38 A clue to this eventuality lies in the final judgement of the 1909 article, which gives a somewhat more generous assessment than he offered to the Canadian Campers at a New York dinner address in 1906. “To one who is ambitious to hunt or explore in an unknown country,” writes Stephen, “the whole of northern Labrador offers a virgin field” (90). In the two and a half years since his expedition, Stephen has progressed from warning sportsmen against Labrador to encouraging them to go. Indeed, he offers one “attractive plan for an expedition,” and then a second, more ambitious “valuable but difficult” possibility (90–91).

39 Stephen’s final paragraph is the most lyrical of the piece, full of sensorial details more typical of Florence’s style, but combined with a tendency to abstraction that he will indulge to a much greater extent later on. Unexpectedly, given the restraint of the rest of the text, he suddenly begins extolling the landscapes’ beauty and “lonely grandeur,” and marvels at how these landscapes make one contemplate the magnitude of creation and the smallness of man. His final line even shifts to the second-person appeal, “Do you not wish to be the first to look upon them?” (91). It is an open question whether he is addressing his reader, or whether the “you” is at least, on some level, Florence or himself.

“Woman of Determination”

40 The heterogeneous expedition story thus composed by journalists, George Elson, and Florence and Stephen Tasker provides the skeleton for a fuller, richer treatment, but none of any scope was ever attempted. The expedition itself was far more complex than Mina Hubbard’s, and a greater variety of figures came into it, including in some heart-wrenching episodes that would well suit most ideas of storytelling. After the canoe journey was done, the party shipped aboard the HBC ship Pelican, southbound to Cartwright. A woman died on board — Florence even attended at her bedside — and several major local affairs were ongoing, including the closure of the Nachvak post and the failure of the caribou hunt. Completely neglected even by Florence is the fact that an Inuk man falsely accused of rape shared the Taskers’ southbound trip from Cartwright to St. John’s aboard the mail boat Virginia Lake, in custody of law enforcement, though it was common knowledge aboard the vessel that the assault had actually been perpetrated by a Newfoundland fisherman and the man was almost immediately released upon arrival in St. John’s. A dramatic retelling today would certainly expand upon these crises. The Taskers also repeatedly encountered people whom they took to be starving and impoverished, which could have been the basis or at least the central theme of an account. In sum, the clearest reason the expedition story has been forgotten is that it was never adequately told.

41 Yet the idealized story, or the sum of possible stories, is primarily valuable as a context for understanding what the Taskers did choose to tell, both immediately and later on. Eventually Stephen would transform the meanings of his Labrador experiences into romantic ideals, and that process, which we see in time-lapse by reading successive texts, has major implications for the mechanisms of literary production about Labrador. It demonstrates how incidents and details once separated from their context slowly ferment, and ultimately produce a flavour characteristic of the region’s critical consensus. At the same time, however, it is readers, not writers, who delimit a literature, and Florence is the one whom a later audience has selected and transformed.

42 We have seen already that many journalists of the day exaggerated or even fabricated the details of the Tasker expedition to heighten its interest for readers or to make it conform with expected themes. Florence’s gender was a particular focus for factual reporters and inventive ones alike, and occasioned much commentary on her physique, attractiveness, and sociability. Stephen’s crossing of Labrador was not as remarkable to the press; after all, the same crossing had been made by white people before, albeit not by a society gentleman.16 And not surprisingly, Elson’s and Chapies’s achievements were completely beneath public notice. The real story was that a white woman had made the trip. Therefore, many accounts minimize the roles of the male participants and position Florence as the expedition’s leader, for instance, in the Washington Times’s “Woman Conquers Labrador Wilds.” In her own account she is the least essential member of the expedition, though it is hard to know how to interpret presumably tongue-in-cheek remarks like, “It takes thought and good common sense to plan such a journey as we were about to make, and consequently all arrangements were left, in the main, to my husband” (823). Still, she carried gear and paddled a canoe and helped make camp, and her precise contributions of labour or expertise are beside the point. She “went along,” in her own phrase, at a time when that in itself was extraordinary.

43 After the first flurry of news articles and a few passing mentions by writers like Cabot and Prichard, nothing appears in print on either Tasker until 1975, 30 years after Florence’s death and 38 after Stephen’s. Then Florence is remembered in one column of a Field and Stream retrospective on early female contributors (Nichols). Next, a 1987 essay by Gwyneth Hoyle extols “Women of Determination,” and includes a two-page summary of the expedition based on Florence’s “A Woman through Husky-Land” without further research. Most interesting here is Hoyle’s take on Florence’s personality. She recognizes Florence’s “strength of character” and considers her tone one of “candour” and “sardonic humour, but with a strong sense of compassion for the people of the North” (129). Certainly Florence deserves every benefit of the doubt, but it should not be overlooked that she considers the men she meets at Missanabie “the lowest order of redmen in the whole dominion of Canada” and the women “filthy, indolent, and rude” (824), while at Fort Chimo she responds to the living conditions not with sympathy but with “unutterable disgust,” calling the community “all very loathsome” and devoting paragraphs to the repulsiveness of the people, the ugliness of their clothing, and the uncouthness of their habits (940). Florence’s account is not entirely without compassion, but compassion is not its most striking feature. Similarly, Hoyle points out the Taskers’ generosity, and they did indeed share food with several groups they encountered, but Stephen says that “The continual begging of the natives . . . was a great annoyance to us” (“Northwestern Labrador” 90), and Florence describes George Elson tricking Jimmie and Noonoosh, two locals, in a salary negotiation by switching currencies to give them the illusion of receiving more money (826).

44 The point is not to demonize the Taskers, but to challenge Hoyle’s characterization of Florence. Regardless of one’s biases or priorities, a critic must always look at what is present, rather than sifting a literature for representatives of an idea. Florence Tasker may indeed have been “a woman well ahead of her time” as an explorer (Hoyle 129), but like anyone else, as a writer she can only be understood in the context of the time in which she actually lived.

45 In 2002, the same Margaret Nichols who wrote the 1975 piece for Field and Stream republished the better part of Florence’s “A Woman through Husky-Land,” omitting the dénouement over the last few pages, presumably for brevity. This redacted version systematically removes potentially objectionable passages, including all those just described, as well as other obviously racist or insensitive descriptions, misogynistic comments, and anything reflecting at all poorly on the Taskers’ competence. Nichols omits Florence’s homesickness, the Taskers’ dependence on “the mercy of the natives” in determining their route (826), Stephen’s disappointment about having to go inland at Richmond Gulf instead of further north (because no locals knew of or were willing to attempt a portage into Lake Minto), and Florence’s reflections on her own dirtiness, irritability, and undesirability as a woman. None of these omissions was committed for the sake of concision. More natural opportunities existed for that. The idea was to put forward a certain idea of who Florence Tasker was, of what the expedition was about, and of the nature of Field andStream itself. But if we are to understand them, it is vital that we retain what we find objectionable in our writers.

46 The only academic take on the Taskers is a 2006 paper by Roberta Buchanan, in which she uses Florence’s text alongside Dillon Wallace’s books and Leonidas Hubbard’s diary to exemplify a “hag” stereotype of Labrador women. The case is clear-cut. Buchanan goes on to describe more compassionate missionary accounts, which nonetheless elevate Labrador women only as far as victimhood, and then concludes by contrasting both forms of outsider writing with insider accounts like those of Lydia Campbell and Elizabeth Penashue, which position Labrador women as heroines.

47 This is a fertile ground for multidisciplinary discussion, which indeed has been underway for some time.17 The authorship of Labrador stories has often been examined — appropriation and mediation especially being central concerns — but the question of literariness has not entered the conversation. Writers like Campbell and Penashue, and especially Elizabeth Goudie, have reclaimed the protagonist role for Labradorian women, but they have done so mainly according to the anthropological or ethnographic model of outsider observation. That is, they behave like ethnographic writers who decode observations or experiences into information and then report that information, producing Wallace’s “literature of knowledge.” It is a valuable form for many reasons, but ultimately not a model for a healthy, endogenous18 storytelling tradition, in part because once stripped of its theoretical basis or comparative context, the exercise becomes one of celebrating detail for its own sake, as though its significance were self-evident. And indeed it is, in the same way that photographs of a child are obviously significant to its parents: Labradorian readers naturally want to look back at a Labradorian past.

48 Over time, however, when attention is not paid to theme or genre, but only to certain kinds of reportage, the meanings of whole works can shift, so that the details of texts no longer sum to the broader picture — which instead must be communicated to the reader by a social context external to texts themselves. Thus, a litany of tiny details in a text may be thought by writer and reader alike to add up to a picturesque image of a heroic life, when in fact the image is provided by the reader, who has gleaned it from society, and the details are retroactively supplied by the text. This mode sharply limits originality and specificity by removing the process of literary invention from the individual writer and democratizing it through a public. In a “literature of power,” by contrast, a writer processes experiences into subjective meanings, rather than mere information, and uses those meanings to create images that, by definition, are new and particular.

49 Buchanan’s points about the ignorance and insensitivity of early characterizations of Labrador women are well-taken. Still, it must be said that Florence, like Stephen in his later works, models a subjectivity that, however poisonous in some ways, is absolutely necessary for authentic literary production. This would be more evident in fiction, where it is somewhat easier to identify the kinds and degrees of authorial invention, but fiction is not a significant component of Labrador’s literature — perhaps for this very reason. Labrador literature does not consciously invent. It has already accepted a particular romantic thesis, if not as true, then as a basis for conversation, and most qualities of that Labrador pervade even sub-regional perspectives, including those of the Innu whom Buchanan points out in Byrne and Fouillard’s collection, Gathering Voices. Part of the immediate reason for this is the dominating influence of Them Days as a publication venue, but the underlying cause is the habit of understanding Labrador in ways established by visitors, academics, missionaries, and government. Buchanan and many others have recognized the shift from a Labrador seen by outsiders to a Labrador seen by Labradorians, but another vital distinction to be drawn is that between seeing and inventing — regardless of subjecthood.

“The Camera Replaces the Rifle”

50 Labrador may become romantic by many mechanisms, but the works of Stephen Tasker give an unusually clear impression of a typical pathway. His initial reaction has been documented — the land is miserable, disappointing, and almost entirely without merit. Yet over time, as Stephen’s primary emotional response to the expedition recedes, his remembered Labrador experiences gain an almost talismanic quality, so that 30 years on they become a primary data source for testing his metaphysical ideas.

51 In 1929, he produced Under Fur and Feather, a collection of six animal fables based on personal experiences, prefaced by the statement, “The incidents are true and the conversation, what I felt took place between us” (8). The main theme of the book is the juxtaposition of human malice with animal love, and each story has a simple, sentimental moral. The first two are set non-specifically “in the heart of the deer woods” (9) and at a lake in a forest, respectively, but the last four are all explicitly set in northern Canada. “Wawa,” for example, takes place in James Bay in 1906 on the Taskers’ northward journey, and draws on explanations by “Indians” (Elson and Chapies, or perhaps locals) to explain that the wild geese “know nothing but honor and fidelity,” and so possess the secret to happiness. Stephen’s language is altogether unrecognizable from his earlier work, apart perhaps from a weakness for rhetorical questions: “Their slow beating wings, so white, so soft, so lovely in the moonlight — could anything more resemble angels than they did?” (16). The next fable, “Furry-Face,” is a lesson on gratitude, featuring a beaver from Labrador caught in a trap, and the fifth is set during the seal hunt on the Grand Banks, though in this instance it is unclear whether Stephen is actually writing from personal knowledge. The final piece is different from the rest, and while the close is entirely typical, the opening breaks from the formula by its specificity. The protagonist here is a pet dog, “Strong Heart” (identified as “Pat” elsewhere), which the Taskers took with them by rail as far as Missanabie, in 1906. The dog camped with them at the lake there, but soon proved its unfitness for the wild, and on Elson’s advice the Taskers sent it home by rail.

52 What’s It All About? followed the year after and was twice as long, with 13 fables over 36 pages. Here Stephen’s preface claims less authenticity, saying the book “is written from experiences, facts and fiction. My Philosophy and the stories are what you make of them” (9). Some of the fables are complete fabrications, but others include plausible details repeated in other articles. Nine of the fables are set in Canada, mostly in the north, but with some Gulf of St. Lawrence locations as well — New Brunswick, Gaspé, and Anticosti. Still, probably half but certainly at least three of the fables are drawn from the 1906 expedition.

53 The other significant change since Fur and Feather is a gradual shift in form, not only towards invention, but also towards variability in structure. Some of the pieces are not in fact fables, but parables, as they have human subjects. Others are not narratives at all, but essays, and some are altogether idiosyncratic. “Kasba” is important, in that it completely revises Stephen’s opinion of the “Nascaupee,” as Stephen now calls them. The “begging” he had previously called an “annoyance” is now reconsidered, as Stephen tells the story of a man poking through the remains of his campfire, gathering “pieces of our pancake in the ashes” and taking them back to his “comely” wife with “self-sacrifice and gentleness.” Conversing with the man, Stephen learns about the true nature of kindness, and juxtaposes this wisdom with the reason for his own journey to Ungava, undertaken “to forget myself and the mean, thoughtless, selfish and unkind things I have done.” Here the Nascaupee takes the place Stephen usually reserves for animals. Stephen even shifts to an ecological explanation for the poverty and starvation afflicting the man’s family, blaming them on the lateness of the caribou, rather than on improvidence, as before. These Nascaupees are “too proud” to ask for food, and their “emotion and suffering are hidden, controlled.” In short, Stephen makes them noble victims of circumstance, simple-minded but essentially wise and good (19–21).

54 “The Mosquito, Rat and Snake” is an essay contrasting the three worst animals Stephen can think of. He begins by repeating the images of mosquitoes pattering like rain and snuffing out candles, claiming that “man and animal fear them more than the bullet” (50). He wonders, “What is their use?” before inquiring similarly of the rat and snake. Finally, he supposes that the snake’s purpose must be “to personify the Devil,” before correcting himself, noting that a snake strikes and lets go, whereas the Devil “has taken hold of me . . . and I can’t shake him off ” (51). Again, nature and the animal world, even at their worst, represent an escape from guilt and complicity in the follies and cruelty of humankind.

55 The final chapter, “Voices,” is a lyrical piece, again set in Ungava, and offers two basic concepts, the first a mysterious longing for one unspecified voice from home (“the voice I wanted to hear,” not Florence’s) and the second a delight in the voices of the wind, land, and water — the Romantic Aeolian harp — as explicitly contrasted with human voices, “Indian, Eskimo, French, Irish, Scotch and my own” (61). The speaker sheds a tear and imagines it joining a stream, where-after “it will be drawn to the heavens, and it will be cleansed from all earthly matter in that great and perfect still of the clouds, and it will come again to our earth, and be buried and born yet again, even as you and I” (63). Labrador becomes a land not only of purity, but of purification, and the book ends with Stephen “gently kissed” by the wind and falling asleep.

56 Finally, a year before Stephen’s death came Steve Patrols More Territory, a 111-page book of 18 chapters of all kinds. The first is actually titled “Fable,” and displays Aesopian concision, down to the moral: “a spouting whale courts the harpoon” (14). The other chapters are wildly varied, ranging from “What Is Life?” — an even more wide-ranging essay than the title suggests — to “Man or Ape,” a farcical take on evolution, and to a chapter entitled “George Elson.” The whole book is littered with quotations and references to scientists, poets, and philosophers, and is clearly positioned as the culmination of the “Philosophy” (Stephen’s capital) embarked upon in the previous books.

57 Labrador appears throughout the work, but most significantly in the Elson chapter, which begins with a brief account of Elson’s part in the 1906 expedition, then ventures a number of asides on the Hub-bards and other figures, including a citation of Prichard’s mention of the Taskers in Through Trackless Labrador. Most fascinating, however, is the description of a lasting friendship with Elson. “We have known him thirty years and claim him our friend,” says Stephen — and not only did Stephen visit him and his wife at James Bay years after the 1906 trip (without Florence), as described in “Frogs,” but Elson and his wife also visited the Taskers in Pennsylvania, where apparently “friends, acquaintances, and reporters made much of him” (48). A letter from Elson to Stephen is reprinted, inviting him to come on a polar-bear hunt, and passing news of the death of Jim (Jimmie), who had accompanied the 1906 expedition part of the way.

58 Several print photographs are enclosed in the book by way of illustration, including images of Stephen and Florence dated New Year’s Day 1936, and a portrait of Elson opens his chapter. This also explains the otherwise incongruous prints tucked into the front cover of the 1906 album at Memorial University. These fall outside the album’s pictorial narrative, and are dated “July 24th 1920” and “1924.” The 1920 shot is of Elson presumably in East Main, James Bay, playing a fiddle in the kitchen; it may have been taken by Stephen during his visit. The 1924 images show Elson and his wife, in one, and the two of them with Florence, in the other, posed outside a house with stone pillars, likely the Taskers’ in Wynnewood, west of Philadelphia.

59 A final chapter worthy of particular mention, “Chimo,” serves as a case-in-point in demonstrating the transformation of Stephen’s outlook. Here he allegorizes life as a portage, giving as its destination an eponymous paradise and wildlife sanctuary (Stephen gives the meaning of “Chimo” as “welcome”), then veers back into literalism by laying out a program for humane animal treatment, including the trading-in by sportsmen of rifles for cameras (86). Stephen’s attitude towards Labrador and its people has changed, but although his attitude has become more positive, it has also become less genuine: despite the empathy of the camera-toting tourist, it is the hunter whose perceptions are rooted in a practical understanding of the ecological system. When the hunter in Stephen writes, he makes a report based on narrow personal interest, but notionally objective within that space. When the tourist in him writes, especially after a delay, he fits a narrative constructed of expectations to a set of snapshots taken arbitrarily. In so doing, Tasker applies a very different sort of pressure on the society described.

60 A robust literature supports and welcomes external influence as a principal means of growth, but Labrador does not have a robust literature, and Stephen Tasker is only one of a great many writers of his kind. Their collective romanticism has shaped Labrador literature far more than is ordinarily recognized, and only by understanding the origins of that romanticism can critics avoid perpetuating its over-emphasis and shift our consideration to other ideas, endogenous and external alike, about what Labrador might be.

61 It is Florence Tasker who provides us with a small example of how that can be done. With “candour,” yes, as Hoyle says, but also with characterization and precision of detail drawn out into scenes, and scenes into stories, rather than themes or ideas — or if ideas, then new ones arising from the idiosyncratic processing of experience. This practice is not absent in Labradorian works, but it is not common, partly because it requires a redirection of attention to form in order to enable synthesis, whereas, hitherto, form has consistently been adapted from ethnography, and the focus has been on collecting the content to sustain it. Put bluntly, for the sake of balance and sustainability if nothing else, Labrador literature needs to move past the formulaic production of oral histories and embrace a diversity of individual approaches to storytelling.

Conclusion

62 “Story” in Labrador generally means an oral history, and such stories form the basis of most endogenous Labrador literature.19 The preponderance of that single form, often mediated by anthropologist editors, has created a paradigm wherein writers begin with observations of their environment or day-to-day life and invest with significance their experience as participant-observers by an ethnographic process that celebrates stock cultural indicators. Readers in turn learn to expect this set of indicators when they read, and come to texts prepared with an interpretive matrix that evolves based on social, cultural, and political circumstances. Thus individual authorial creativity is largely replaced by a consensus or democratized creativity situated within the readership. This makes stories function fundamentally differently on a broad social scale, increasing their usefulness as tools for social cohesion and identity reinforcement, but reducing their diversity and their capacity for aesthetic innovation.

63 Conversely, outsider writers like Stephen Tasker elevate similar basic observations about Labrador life because of their perceived lack of cultural specificity, finding, instead of a characteristic Labradorian quality, a universal, primitive reality. The object itself may be either condemned as unsophisticated or praised as innocent, but the abstracted concept is typically romanticized. From a decolonizing point of view this approach is simply an error, pushing the Labradorian down a spectrum of noble savagery towards pre-lapsarian man, while in a broader sense it is also the ordinary mechanism for developing literary ideas: the simplification of othered experiences in terms of one’s own subjectivity. Either way, for insider or outsider, Labrador’s land and people become fonts of exaggerated legitimacy. If a thing happens on the land in Labrador, then for Labradorian writers it becomes automatically a candidate for essential Labradorianness, while for outside writers it represents a universalizable truth of unusually high order, much like the elevated yet mundane trivia of Thoreau’s time at Walden Pond.20 The end result is an insider literature intractably rooted in detail but with comparatively little scope for innovation, and an outsider literature rich in wonder but comparatively destitute of actual engagement with local character.

64 Romance is valid as a genre or theme, but not as a critical perspective. Nor should it be permitted to take the place of genuine self-inspection — though in Labrador it has all too often done so. Popular and critical discourses root Labradorian identity in personal and spiritual relationships with the land, for example, particularly as a consequence of resource disputes, but a society is the product of its history, not merely its environment. And as the Taskers saw first-hand in 1906, in spite of the exalted place land holds in the imagination, Labrador’s environment is not particular enough to justify a regional exceptionalism. Labrador cannot possibly have a distinctive identity based on the land alone, when its biomes are among the most common in the world, and when local responses to them are typical of Indigenous peoples and frontier settlers everywhere.

65 Yet Labrador does have a distinctive identity, far more evident at the regional level today than in 1906, and the landscape is undoubtedly an essential formative component of that identity. This contradiction obliges us to nuance our social critique in pursuit of a reconciliation. Stephen Tasker’s wide-ranging ruminations model one version of that process, showing us what we so often do, over the long term, to transform our lived experiences of Labrador into radically different, invented ones. The history of Florence Tasker readership likewise says a good deal about our revisionary critical habits.

66 The Taskers’ stories may have no natural public audience today, any more than they did when they were written. But if we could retain the past century of advances in Labrador’s political and literary sensibilities while also learning from Florence Tasker how to articulate what we actually see in Labrador through our own individual subjectivity, and if we could combine Stephen Tasker’s universalizing impulse with the observational sensitivity and wisdom of Lydia Campbell or Elizabeth Goudie, then we might be able to imagine a literary Labrador more locally relevant and compelling than that of the explorers of leisure — and more artistically diverse than that of Them Days. We could celebrate an unromantic Labrador.

The research behind this essay emerged from a collaboration with Linda White at Memorial University’s Archives and Special Collections, on the digitization and description of the Taskers’ 1906 expedition album. I gratefully acknowledge the assistance I received from Linda and the staff at the Centre for Newfoundland Studies during the early phases of my research. Roberta Buchanan was also an invaluable source of information and insight on the Taskers and Labrador exploration literature more generally. So, too, was Martha MacDonald, who also provided many helpful comments, conversations, and critiques during the production of this essay.