Articles

William Eppes Cormack (1796–1868):

The Later Years

Introduction

1 The story of William Eppes Cormack’s early years was presented in this journal in 2016.1 Cormack is well known in Newfoundland for his walk across the island in 1822, and for his efforts on behalf of the Beothuk, Newfoundland’s Indigenous people. He was born in St. John’s in 1796, the third of five children to Janet (née McAuslan) and Alexander Cormack. His older two siblings had died by the time he was six years old, and his father died a year later, in 1803. Janet Cormack remarried, to the merchant David Rennie. The couple had five children. In 1810, the family left Newfoundland for good and settled in Glasgow, Scotland, where William attended Glasgow and Edinburgh universities. In 1818 his stepfather, David Rennie, sent him to Prince Edward Island (PEI) to settle Scottish crofters on land he had purchased years earlier.

2 In early 1822, about a year after his mother, Janet Rennie, had died, Cormack returned to St. John’s, Newfoundland. This paper presents in outline what is known of Cormack’s life from 1822. It covers Cormack and Sylvester’s walk across Newfoundland in 1822,2 Cormack’s founding of the Boeothick Institution, his search for Beothuk survivors, and his efforts to collect information about the Beothuk from Shanawdithit, as recorded in Cormack’s papers found in the Howley family archive in St. John’s in the 1970s.3 The content of many of these papers was published in J.P. Howley’s The Beothucks or Red Indians,4 though some of the material referred to in this paper is new.

3 Cormack’s family’s business interests in Newfoundland are outlined as well as his eventual bankruptcy. After leaving Newfoundland, he lived in the Maritimes, Australia, New Zealand, and California, with returns to England. Cormack died in British Columbia in 1868.

4 Important primary archival material and manuscripts discovered by the authors over the years include the only preserved record in Cormack’s handwriting5 of his journey across Newfoundland, which he submitted to the Natural History Society in Montreal in 1832–33. This manuscript was found at the McCord Museum, Montreal, and a copy is now held at the Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Memorial University.6 Another is Cormack’s lengthy and significant paper on the Newfoundland fisheries, which was located in the Board of Trade documents at The National Archives, Kew, England. There is also Cormack’s description of his discovery of a moa bone, in New Zealand, among the papers of Richard Owen, the foremost authority in the field of extinct, flightless birds, in the Natural History Museum, London.7 The Royal Botanic Garden Library and Archives, Kew, holds informative correspondence of Cormack with Sir William Hooker.

Cormack Returns to Newfoundland, 1822

5 Upon returning to Newfoundland in 1822, Cormack took over the administration of the family property in St. John’s, which his mother had left in a trust disposition on behalf of her three Cormack children, William Eppes, John Bell, and Janet Grace.8 This trust covered properties previously owned by her first husband as well as her own purchases after his death. The largest and most valuable holding was Roope’s Plantation, a waterfront property with wharves and storage facilities. William Cormack appears to have lived in the spacious dwelling at Roope’s9 but probably sublet some of the storage and wharf facilities. Roope’s Plantation incorporated large tracts of land between Water Street and New Gower Street, as shown on the Plan of St John’s by surveyor William R. Noad.10 Due to housing shortages in St. John’s during the early 1800s, some of it was sold as building lots that would have yielded ground rents.11 At that time, Crown land leases for part of a plantation were £20 and a waterfront lot was £86 per annum.12 Beyond the boundaries of Noad’s Plan of St. John’s, the Cormack siblings also owned the River Head Farm;13 “a certain field or enclosed meadows” including “tenement or premises with all its appurtenances” near Fort William;14 3½ acres of Crown land that Janet Cormack had leased for 21 years;15 and substantial acreage in the area of today’s Victoria Park.16

6 Rather than starting a business in the tradition of his father and stepfather, Cormack appears to have lived on his share of the income from these properties as well as rents from the land he owned in PEI. Hence, within a few months of his arrival “free from professional engagement,” Cormack decided to pursue his personal interests and to explore the “Interior of the Island, a Region almost totally unknown, and concerning which and its aborigine inhabitants, the Red Indians, who were supposed to occupy the whole of it, the most besotted conjectures were entertained particularly by the chief delegated public authorities.”17

7 Having witnessed the opportunities in PEI as it opened up its forested inland areas to settlement and cultivation, Cormack was clearly interested in investigating what Newfoundland’s interior had to offer. As it was virtually unexplored by Europeans, Cormack wished to “throw some light upon its natural conditions and geography.”18 Possessing considerable drive, perseverance, and courage, he set about to undertake the hazardous journey of crossing the island on foot.

8 Cormack’s plan for the expedition may have been inspired by John Barrow’s Chronological History of Voyages into the Arctic Regions, which includes Capt. David Buchan’s19 report of his expedition to Red Indian Lake in central Newfoundland in January 1811.20 Buchan’s information was confined to the observation that “the general face of the country in the interior exhibits a mountainous appearance, with rivers, ponds and marshes in the intermediate levels or valleys,” also noting that most of its timber was stunted. Barrow noted that “we know so little of the interior [of Newfoundland], or even of its shores” after a settlement of more than two hundred years, and no attempt has yet been made “to collect a Flora of the island.”21 In 1823, following his journey, Cormack submitted to Barrow the first report of his expedition and intended “to continue to pursue his enquiries into the natural productions of the country” informing Barrow of anything “worthy of being communicated” in the future.22 In effect, Cormack wanted to narrow the gap in existing knowledge about the island’s interior, including its geology, flora, and fauna. His interest in geology was inspired by his mentor and “excellent friend and distinguished promoter of science and enterprise,” Professor Robert Jameson, Edinburgh University.23

9 Though it has generally been assumed that the main purpose of Cormack’s trek was to meet with the Beothuk, the evidence suggests otherwise. When choosing a route he was, rather, guided by the “the natural characteristics of the interior [that] were likely to be most decidedly exhibited” between Trinity Bay on the east coast and St. George’s Bay on the western shore, so that he would traverse the main body of the island at its widest, excluding all large peninsulas.24 With regard to making contact with the Beothuk, Cormack believed he would come across some of them en route since they were supposed to occupy the whole of the “central parts.”25 When he described the object of his expedition to Governor Charles Hamilton, Cormack stated only that he wanted to obtain “a knowledge of the interior of the country.”

10 Cormack engaged Joseph Sylvester to act as his guide. Sylvester may have been recruited for him by J.S. Christopher from Messrs. Newman, Hunt & Co., who operated fishing/merchant stations on the island’s south coast.26 In his Narrative, Cormack described Sylvester as “a noted Micmac hunter from the south-west coast of the Island,” that is, Bay d’Espoir, in particular the area near Weasel Island, to which Sylvester planned to return after the trek to join close kinsfolk.27 Although today Cormack’s guide is also referred to as Sylvester Joe,28 there is ample evidence that his name was Joseph Sylvester.29 The most striking proof is his signature — “Joseph Sylvester 182_” — in a book of catechisms and prayers in Mi’kmaw hieroglyphics that he is believed to have owned.30 Since Cormack was not conversant with Mi’kmaw, it must be assumed that Sylvester spoke English and possibly some French. With regard to his skills, Sylvester was not only a good shot, but was an experienced woodsman who knew how to travel and survive with a minimum of support in the type of country that they planned to cross. A river system — roughly sketched onto Cormack’s field map,31 presumably with the assistance of Sylvester — suggests that he had first-hand hunting experience in the country east of Bay d’Espoir and between Fortune and Bonavista bays. The latter area was the home of Peter Sylvester, his wife Susan, and their son Michael, who were probably related to him.32

A Trial Expedition: July–August 1822

11 Before they set out on their historic journey, Cormack arranged a trial excursion that took the two men from St. John’s to Placentia via Holy-rood and St. Mary’s Bay and back by way of Conception Bay, which he reckoned was “a distance of about 150 miles” (240 km).33

12 They set off on 25 July 1822, walking from St. John’s to Portugal Cove and from there along the coast to Holyrood. The innkeeper there “affronted Joe so much that he was going to desert me . . . however, I pacified him after a good deal of persuasion.”34 In his diary, Cormack noted plants and “zoology” and described the landscape and its geology. Progress was often impeded by wet, mossy ground covered in tree stumps and by large ponds. Six to ten miles (c. 9.5 to 16 km) was the most they could advance in a clear day; when it became foggy they travelled by compass. They both camped in the wild but also overnighted at the occasional inn or private home. On the way, partridges, ducks, and geese were their mainstay. Once they caught a beaver and Sylvester roasted the meat by throwing it on pieces of burning wood. Cormack found it so delicious that he decided to stay in camp for a day to feast on it.

13 On 9 August, the men arrived near Placentia Bay and left on the 14th towards Spread Eagle. In his diary Cormack records an ancient cross composed of stones laid on the ground about 30 feet long and 20 feet broad at Bay du Nord, “about ¾ miles from the salt water.” The two travellers arrived at Harbour Grace three days later and slept at Fox’s, “a good clean house.” Cormack visited several inhabitants there and on the 19th the two men joined a party sailing to Portugal Cove, arriving in St. John’s at 10 p.m. that night. The diary closes with advice about suitable clothing for a trek of this nature. Cormack also sketched a map of the lay of the land that, together with the diary, has been preserved among his papers.35 He later sent a sketch map and a letter with instructions on the best route from Holyrood to Placentia to “Mr. Munby of [HMS Sir Francis] Drake.”36 The trek was a success in that it apprised Cormack of Sylvester’s capabilities, of their compatibility, and it reassured him of food availability in the country and the suitability of their equipment.

The Expedition to Explore Interior Newfoundland: August–November 1822

14 Cormack decided to leave St. John’s at the end of August and prepared equipment for three participants for a three-month campaign. 37 The third travel companion was to be Charles Fox Bennett, a merchant and Stipendiary Magistrate (later premier of Newfoundland), 38 who was three years Cormack’s senior and a friend. None of the other volunteers, and there were several, were suited in every respect.39 At the end of August, shortly before the three men were to start their journey, Bennett had to withdraw because the “chief government authority was opposed to the project.”40 The reason for the governor’s disapproval was never explained. Information about topographical and geological features of Newfoundland’s interior would have been a valuable asset, worth reporting to government agencies in Britain. Five years later, in 1827, when Governor Thomas Cochrane was asked for a topographical and geographical record of the island, Cochrane readily pointed to Cormack’s expedition, which up to then was the only set of observations of the island’s interior.41

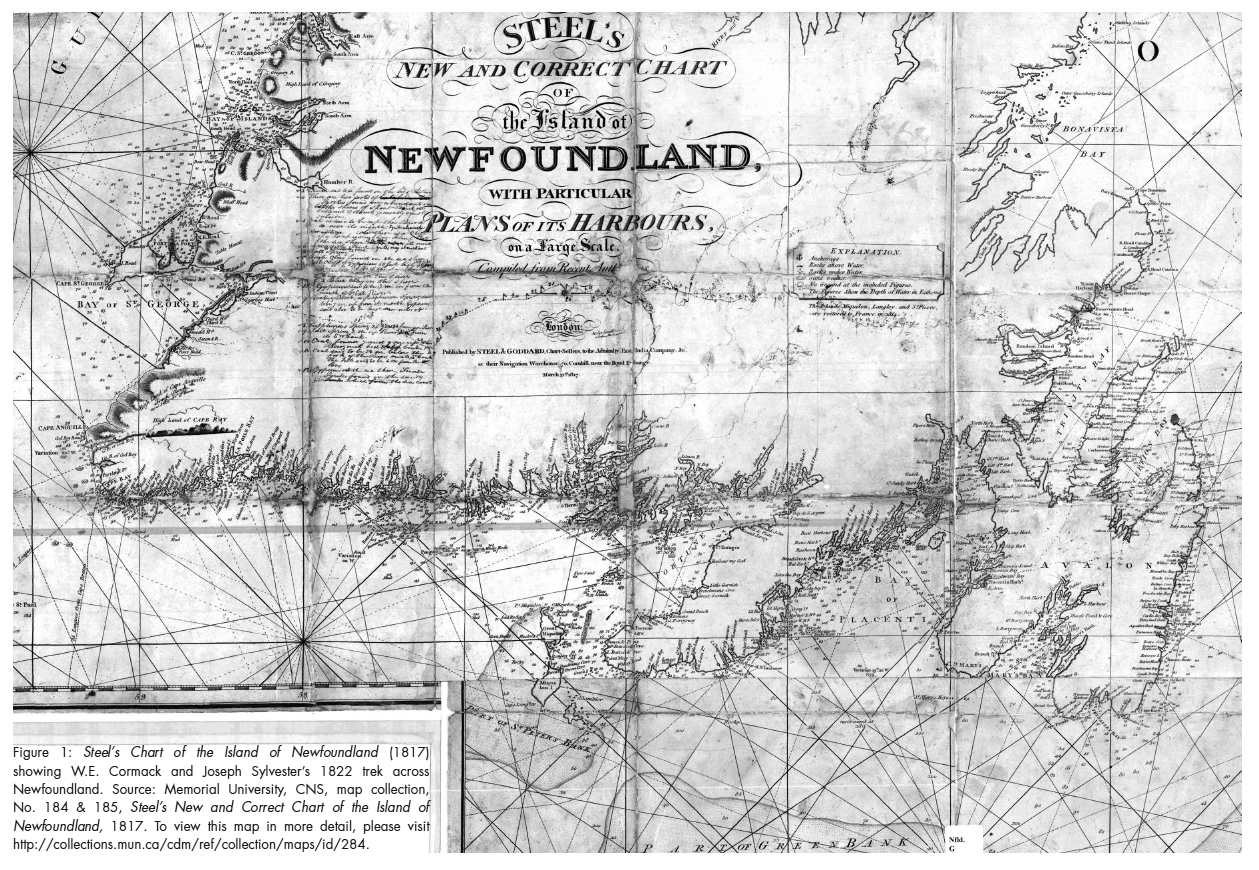

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 115 Having come to know Sylvester as a reliable and skilled woodsman, Cormack’s spirit of adventure prevailed. As he noted in his report, “uncertainty of result waved over my determination, now more settled (by opposition) to perform at all hazards what I had set out upon. That no one would be injured by my annihilation was a cheering triumph at such a moment.”42

16 A debatable explanation for Cormack’s determination to lead an expedition into the interior of Newfoundland was a newspaper account that claimed he had been married to a young woman in PEI and that this marriage had ended in tragedy and psychological trauma. This supposition is based on a story known as “Hunter’s Grave,” first published in an “old Charlottetown newspaper” in 1879 and republished in the Charlottetown Guardian in 1939.43 Some of Cormack’s reported activities and credentials are described fairly accurately, though the given time frame does not fit. According to this tale, Cormack was to marry a Marion Whittier from Rustico, PEI. She had once been betrothed to an Arthur Hunter, who was thought to have died during the War of 1812. Hunter, however, turned up on the wedding day and, realizing the situation, disappeared into the woods. Desperate and guilt-ridden, Marion led a search party but failed to find him. Hunter’s remains were later found by lumbermen and were buried near the river subsequently known as “Hunter’s River.” Although the story is tenable, there are few known facts: neither Whittier nor Hunter could be found in existing records and the Hunter River was named by surveyor Samuel Holland after a Thomas Orby Hunter, in 1765.44

17 Cormack and Sylvester boarded the steamer to Old Bonaventure in Trinity Bay and a hired boat took them to Smith Sound, in the area of Flower’s Cove. On 5 September 1822 the two men set out on their trek due west.45 Cormack used the upper part of Steel’s New and Correct Chart of the Island of Newfoundland with Particular Plans of its Harbours to mark their route with a dotted line starting at St. John’s Harbour and ending at St. George’s Bay (Figure 1).46 Little flags, intersecting the line between each date, indicate the distance covered on a particular day. With a pocket compass to determine their course, Cormack could only ascertain their route in a general way.47

18 In the early stages of the trek, Cormack was haunted by “apprehensions and thoughts of no ordinary kind” and was unable to sleep, while Sylvester seemed to be at home in the country and slept soundly. As during their trial trek, progress was slowed by trackless marshes and woods, by wind-fallen trees, brush, ponds, and brooks, as well as the suffocating heat and bloodthirsty flies.48 Cormack also blamed the weight of their 22-kg knapsacks for their delay.49 Once they reached more open country they covered greater distances, and when gaining a view from occasional hilltops Cormack was utterly enchanted by the magnificence of the scenery.50

19 After crossing Southwest River, the abundance of wildlife persuaded them to consume their remaining provisions, though this decision then forced the men to hunt daily. While they shot a few caribou, they largely lived on beavers, geese, and ducks.51 They also fished for trout and ate berries. By mid-September, the two travellers descended into the plains or savannas, as Cormack called them. At this point in the journey, Sylvester voiced his dissatisfaction with the arrangements — perhaps because he realized that this was going to be a longer and more cumbersome trek than anticipated — and Cormack agreed to more compensation at the end of their journey, which included pork and flour for Sylvester’s mother and trips to Europe, “in order that it might do his health good.”52

20 Cormack and Sylvester spent close to a month trekking through the flat country that forms the east-central portion of the interior. A solitary mountain peak served as a marker by which to check their course. Cormack named it Mount Sylvester after his guide, a toponym that is still in use today.53 In early October, the travellers reached a hilly ridge at about the centre of the island that proved to be a serpentine deposit. Its mineralogical appearance was so singular that Cormack stopped for a day or two to collect specimens; he believed this to be a quiescent volcano. Cormack named the ridge “Jameson’s Mountains,” after his Edinburgh mentor. 54 At this point, Cormack noted that they had not yet seen any trace of the “Red Indians” who were supposed to occupy the central regions of the island but he expected to meet them farther to the west.55

21 Gradually, the strain of the trek took its toll, and on 10 October Cormack recorded that he and Sylvester were feeling the detrimental effects of the continued excessive exertion, of wet clothes, and of irregular supplies of food. Sylvester wished to retreat to the south coast to overwinter but for Cormack this was not a choice and he kept encouraging Sylvester by “promises of future rewards.”56 Continuing westward through rugged, mountainous country they arrived at the hunting camp of James John, a Montagnais [Innu], who provided them with a bark map outlining the route for the remainder of the trek.57 Cormack was told that the country of the “Red Indians” lay nine to eleven km to the north but that at this time of the year the Indians would overwinter at Red Indian Lake, an even further distance from their path.

22 On their continued westward trek, a heavy snowfall forced the two men to stay in camp. Their provisions were soon exhausted and deep snow prevented hunting. The situation had become precarious when, in an “enfeebled” condition, they reached the camp of a Mi’kmaw family.58 Cormack could eat only a few mouthfuls, his jaws and stomach were too weakened. On 21 October, after a few days of rest, the men were once again able to progress in a southwesterly direction. Cormack continued to record the general appearance of the country and its geological features but he was unable to describe other details because the snow “concealed the characteristics of the vegetable as well as the mineral kingdoms.”59

23 In the following days the men passed many thousands of caribou hastening eastward on their periodical migration, herd followed upon herd in rapid succession over the whole surface of the country.60 They were able to shoot caribou every day, but even this ample supply of food was inadequate to lift their state of exhaustion and painful fatigue. “For my part I could measure my strength — that it would not obey the will . . . beyond two weeks more,” wrote Cormack.61 It became imperative to reach the coast as quickly as possible. When Sylvester started to turn in a southwesterly direction — presumably following the instructions of the bark map — Cormack disputed his change of course because it was leading them further away from Beothuk territory, but Sylvester would not be swayed and Cormack gave in. 62 Travelling westward the two men came upon another Mi’kmaw hunting camp. To Cormack’s mortification he was informed that they were still 97 km or about five days’ walk from St. George’s Harbour.63

24 Realizing that time was running out, Cormack proposed to their host, Gabriel, to accompany them for the last leg of the journey. Gabriel agreed and led the tired men on a forced march through snow-covered country and across swollen rivers.64 On 2 November, having spent close to two months crossing the island, Cormack and Sylvester arrived in Flat Bay and two days later crossed over to the European settlement of St. George’s Harbour. After a few days of rest, Sylvester, “the one who had with painful constancy accompanied me across the Island,” joined other Mi’kmaw families to spend the winter there until spring, and Gabriel, having secured supplies and ammunition, returned to his family in the interior.65

25 As all European and other vessels had already left the harbours on the west coast, Cormack, after having recuperated, made his way to Fortune Bay on foot and by boat. After a harrowing trip, he arrived at the establishment of Messrs. Newman, Hunt and Co., in Hermitage Bay, and within a few days was able to catch the last ship to Britain, the Duck.66

Other Early Nineteenth-Century Travellers through Newfoundland’s Interior

26 Though Cormack claimed that his trek was “the only one ever performed by a European,”67 this statement has been disputed. Some suggest that the honour goes to Father William Herron (or Hearn).68 Trained for the priesthood, Herron was sent to Placentia Bay where he became responsible for the Catholics along the south and west coasts.69 In 1820, after a visit to St. John’s where he performed five baptisms,70 he went by sea to Notre Dame Bay. According to oral tradition, he walked from there to St. George’s Bay “through trackless forests accompanied by a single Indian.”71 Herron would therefore have been the first European to cross Newfoundland on foot though the distance he covered was not as much as that of Cormack and Sylvester, and there appears to be no record of the journey.

27 Later nineteenth-century travellers through Newfoundland’s interior, whose exploits were recorded, included the following: a Mr. Rogers, who was shipwrecked in Port aux Basques in 1833 and subsequently walked to St. John’s; Archdeacon Edward Wix, whose visits to his charges, in 1835, took him across country to many far-flung places; a Mr. Salmon, agent of Messrs Slade & Co, who in the winter of 1844 walked on snowshoes from Twillingate to Piper’s Hole and from there to St John’s. Finally, in 1858 three British army officers crossed the island from Conception Bay to the Bay of Islands; and in the winter of 1875, sawmill owner Joseph William Phillips of Point Leamington, who had urgent business in Toronto, made his way on snowshoes first o Bay d’Espoir and from there to St John’s.72

A Return to Scotland, 1823

Family Matters

28 Cormack reached Glasgow early in 1823 and was confronted with the news that his stepfather, David Rennie, had died on 7 January 1823, at the age of 58.73 According to the inventory of David Rennie’s personal estate, his properties in Scotland were valued at close to £14,000, plus land in Township 23 in PEI. He bequeathed his estate to his five children, David Stuart, James Gower, William Frederick, Robert, and Janet Emma.74 The Cormack siblings, David Rennie’s stepchildren, who had inherited the properties of their Cormack parents, were not mentioned in the will.

29 At the time of his stepfather’s death, Cormack’s younger brother, John Bell Cormack, was in a five-year apprenticeship in the law office of J.S. Robertson and J. Arnott in Edinburgh, having started in 1822. His “Law I” course at Edinburgh University had allowed him to become articled to a solicitor for further training. During his apprenticeship, in 1825, he also attended the “Law II” course and received the title of W.S., Writer of the Signet, in May 1827.75 John Bell Cormack remained in Edinburgh practising law until 1832.

30 In May 1824, Cormack’s younger sister, Janet Grace Cormack, married William Scott, a merchant.76 Before their wedding the couple signed a marriage contract and disposition according to which William Scott renounced any claim to the estate of Janet Grace with regard to properties in Newfoundland, which had been assigned into a trust on behalf of the Cormack children.77 The couple moved to Naples and of their nine children, the first three were born there. Around 1831–32 the family moved to London.78 W.E. Cormack kept in touch with his sister and, in 1850, when he was living in London, Janet’s son, George, was his messenger.79

Writing an Account of the 1822 Journey

31 With the experience of his trek through Newfoundland’s interior uppermost in his mind, Cormack spent the next few months in Glasgow writing a summary of his observations, entitled “Account of a Journey across the Island of Newfoundland.” He also prepared a map of the journey showing the lakes and mountains with the place names he had bestowed, as well as geological formations. Professor Jameson in Edinburgh assisted him in identifying the rocks and minerals he had collected.80 Cormack submitted the report and map through Professor Jameson and John Barrow to the Right. Hon. Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State for the Colonies.81 It was published in the Edinburgh Philosophical Journal in 1824.82 The original manuscript has not survived, though Cormack’s field map is preserved in the collection of the CNS at Memorial University.83 The 1824 report covers little more than five printed pages. In it, Cormack briefly characterized the different parts of the island. Though he listed a few species of trees and shrubs with regard to “a botanical point of view,” he believed the interior not “to be particularly interesting after having examined the country near the sea coast.” Nevertheless, “the island altogether . . . afforded a wide field for research to the botanist.”84 Cormack neither mentioned the personal experiences and deprivations that had hampered the two men’s progress, nor did he refer to his return trip along the south coast to Fortune Bay. In later years, Cormack prepared longer accounts of the trek, described below.

32 While the 1824 “Account of a Journey” had little immediate impact, perhaps at that time travels through the wilderness by one or two men with a guide were not particularly rare, but for many years to come Cormack’s map remained a key source of information about the geography and geology of Newfoundland’s central and southern interior. Geologists J.B. Jukes (1842), Sir Richard Bonnycastle (1842), and J.P. Howley (1860s-1880s) used it in their own reports, including Cormack’s toponyms and geological notations.85 In the 1970s it was claimed that Cormack’s “map of the interior was so precise that it was used in a survey for the trans-insular railway 50 years later.”86

Residence in Newfoundland and Scotland, c. 1823–1826

33 No date has been found for Cormack’s travel back from Glasgow to St. John’s after his stepfather’s death in 1823, but it is assumed that he returned later that year or in early 1824. At that time he was involved in the shipping trade and owned the 120-ton brig Brothers that sailed between Liverpool and St. John’s87 and was part-owner of the 42-ton schooner Oak.88

34 Cormack also started a commission business. In 1825 or earlier he partnered with the Greenock merchant, John B. Thompson, in a company listed under the name Wm. E. Cormack & Co. 89 This business sold goods on consignment for a commission. Between December 1825 and April 1826, the Newfoundland Mercantile Journal advertised split peas and pearl barley on sale by Cormack & Co.90 In June 1826, the company advertised “250 Firkins excellent Irish Butter” sold for “Cash, Fish or Oil.”91 Cormack also advertised for sale or rent “a Pew in the Established Church.”92 Together with Thompson, Cormack also purchased the Seven Sisters, a 59-ton coastal Canadian schooner, and they seem to have been involved in the provisions and lumber trade from Canada.

35 As income, Cormack would still have received his share of the ground rents from his mother’s trust disposition, although the 21-year lease on 3¼ acres of land ran out in 1826. Additional money would have been due to him from his properties in PEI.

36 Despite his business obligations in Newfoundland, Cormack remained focused on his scientific interests. In the fall of 1825 he returned to Edinburgh University to take up further studies.93 The University Class Lists for the period from fall 1825 to spring 1826 record him as attending a fifth-year literature class, as well as Professor Thomas Charles Hope’s chemistry course.94 It may also be presumed that he had contact with his former mentor, the renowned mineralogist Professor Jameson. One of his classmates in the chemistry course, and a student of Professor Jameson, was Charles Darwin.95

37 Cormack returned in June 182696 to St. John’s, where he lived at the Roope’s premises.97 While the commission sales continued, Cormack focused on his researches, first writing an essay on the species of fish and seal harvested in Newfoundland and Labrador. This paper, “On the Natural History and Economical Uses of the Cod, Capelin, Cuttle-Fish, and Seal as they occur on the Banks of Newfoundland and Coasts of that Island and Labrador,” was published in the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal in 1826.98 Mindful of the role that government should play in the fishery, Cormack also accumulated data for a paper on the value of Newfoundland’s fisheries. 99

Cormack Founds the Boeothick Institution in 1827

38 During his years in Newfoundland, Cormack heard reports about the persecution and dwindling numbers of the Beothuk. Sympathetic to their plight, he wanted to try to save these “sylvan” people from extinction “for the sake of humanity.”100 In the fall of 1827 Cormack decided to search for survivors inland from Notre Dame Bay, known to be their last area of refuge, and to “force a friendly interview with some of them.” According to a scribbled note in his papers he considered going with a large party — “11 self and others,” including “4 Indians and 7 able men to be hired.”101 Cormack gave as “Objects of the Red Indian Expedition: Their numbers and apparent means of subsistence,” and his undoubtedly ill-conceived plan was “to surround them and then advance upon them as friends or as their determined captors . . . persuade them by signs and drawings of our friendly intention . . . and that they must come with us to the coast.”102 This time, Cormack’s equipment was to include “Musquittoe veil, Musquitto ointment or mask of oil cloth with goggles, Arrow points, small looking glasses, large beads and one seamless canoe-skin” to carry two men.103

39 On his way to Notre Dame Bay, Cormack stopped over in Twillingate, and on 2 October 1827 he organized a meeting of men interested in the cause of the Beothuk at the court house. Cormack described how the Beothuk had been widely persecuted and appealed to feelings of guilt and sympathy by asserting that “those who are invested with power and influence in society” are all the more obligated “to reclaim the aborigines from their present hapless condition” and “bring about justice.”104 It was proposed to form a society “to be called the Boeothick Institution for the purpose of opening a communication with, and promoting the civilization of the Red Indians of Newfoundland.” The idea for such an institution had come from A.W. Des Barres,105 a senior assistant judge of the Supreme Court and judge of the Northern Circuit Court, who had offered Cormack a berth on the vessel that took him northward for his judicial duties.106

40 The institution was to be supported by voluntary subscriptions and donations. The Bishop of Nova Scotia, John Inglis,107 was voted patron and the Hon. Augustus Wallet Des Barres vice-patron. Cormack became president and treasurer, John Dunscombe 108 vice-president, and John Stark109 secretary. The position of honorary vice-patron was assigned to Professor Jameson, Cormack’s mentor in Edinburgh, and to John Barrow, Esq., one of the secretaries to the Admiralty in Britain. John Peyton Jr., justice of the peace and merchant at Twillingate, was voted resident agent and corresponding member at Exploits.110 Many of the local elite — and Twillingate was a wealthy merchant centre — signed up. It was proposed that the Beothuk woman “Shanawdithit,” at that time living with the Peytons, “be placed under the paternal care of the institution, the expense of her support and education to be provided for out of the general funds.” Peyton had taken Shanawdithit into his household in 1823 after her mother and sister had died. The proposal of the Boeothick Institution was later used to authorize her removal from Exploits Island without Peyton’s permission (described below). In an 1828 letter to John Stark, Cormack reflected on the success of the meeting, reminding him of “the ever memorable and glorious day at Twillingate, when the oldest and most respectable inhabitants of the place reluctantly left the dinner table of the Court to breakfast with their families,” suggesting that the discussion continued throughout the night.111

41 Cormack later rejected the Bishop of Nova Scotia’s suggestion to name Governor Sir Thomas Cochrane as patron of the Boeothick Institution,112 presumably because Cochrane had acknowledged neither his successful 1822 trek across the island nor the aims of the Boeothick Institution, and had shown no interest in the care of Shanawdithit. Indeed, Cormack accused the government of gross negligence of the island’s Indigenous inhabitants, stating, in well-intentioned but colonialist language of the time: “It is a melancholy reflection that our Local Government has been such that under it the extirpation of a whole Tribe of primitive fellow creatures has taken place.” 113

Cormack’s 1827 Trek Inland in Search of Beothuk

42 By the time the search for Beothuk survivors was to begin, Cormack had abandoned the idea of taking hired men, most likely due to lack of government support and financial considerations. Having been unable to get in touch with Joseph Sylvester through his contact, Wm. Creed in Galtois,114 he engaged John Louis, an Abenaki,115 Maurice Louis, a young Mi’kmaq,116 and an elderly Montagnais, John Stevens.117

43 Though Inglis, the Bishop of Nova Scotia, believed that it would not be safe to rely entirely on his chosen crew,118 Cormack was satisfied to go with his guides and defended their reputation in a lengthy note that forms part of his papers.119

44 The men began their journey from the Peyton household at Exploits Island, where Cormack met Shanawdithit for the first time. On 31 October, after many delays, the party was taken by one of Peyton’s boats to the mouth of the Exploits River. Walking in a northwesterly direction for four days they came to the northern end of “Badger Bay-Great Lake” (today’s North Twin Lake), where they found remnants of a Beothuk village with vestiges of eight or ten winter mamateeks (the Beothuk term for wigwam) and remnants of a small skin tent for taking steam baths.

45 The party moved on towards Red Indian Lake. By mid-November the winter was well underway and deep snow made walking laborious. When they arrived at the lake, it soon became clear that the Beothuk had deserted it long before. Remnants of their occupation included small clusters of winter and summer mamateeks, storage buildings, and the wreck of a large birchbark canoe. There was also a cemetery with a variety of graves. In a burial hut, two adults wrapped in skins were laid out at full length, with children. A skeleton in a pine coffin, neatly shrouded in white muslin, turned out to be the remains of Demasduit, or Mary March as she was called by her captors.120 Cormack removed several of the offerings surrounding the interred bodies, including figurines, bark cups, a canoe replica, and a bow and quiver of arrows, and also took the skulls of Demasduit and her husband, Chief Nonosabasut.121

46 The last hope of meeting Beothuk was now to search for them along the Exploits River where they were known to hunt caribou for their winter provisions with the aid of fence works. The men went downriver on rafts, noting along their journey old fences in complete disrepair.122 Cormack concluded that any surviving Beothuk may have taken refuge in some sequestered spot in the northern part of the island. At the end of November, after 30 days of trekking through the country, Cormack returned to John Peyton’s. Peyton did not recognize him at first: he now had “a gaunt, haggard and worn out appearance . . . [and] did not look much like the stalwart individual he saw depart for the interior a month earlier.”123

47 As Cormack had plans to leave for Britain to lay the proceedings of the Boeothick Institution before the Earl of Bathurst, Secretary of State for the Colonial Department,124 he wrote only a “brief outline” of the expedition, which was read at a meeting of the Institution by its chairman, A.W. Des Barres. The report was published in 1829 in the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal.125 It did not include a map but Cormack’s friend, John McGregor, marked the route on a “Map of Newfoundland” in his book British America.126 A vocabulary of the Beothuk language, consisting of 200 to 300 words that Cormack had obtained, would have been the Demasduit word list collected by the Rev. John Leigh, who had given a copy of it to John Peyton.127 He gave the “ingenious” Beothuk artifacts128 he had collected to Professor Jameson for the University Museum in Edinburgh.129 Cormack left St. John’s on 14 January and returned on 22 May 1828.130

A Search for Beothuk Launched by the Boeothick Institution in 1828

48 In Cormack’s absence, the Boeothick Institution in February 1828 decided to send John Louis [Lewis] and John Stevens, accompanied by Abenaki Peter John, on another search. To forestall any unfriendly interchange, they were instructed not to make contact with the Beothuk but only to establish their numbers and the area they occupied. 131 They were to travel overland to St. George’s Bay, search the country around Grand Lake and to the west of Red Indian Lake, and proceed from there to White Bay, returning via the Exploits River. The projected route covered more than 800 km as the crow flies.132 After trekking for four months through the country without success, the three men returned to St. John’s. When they presented the report of their search to the Boeothick Institution133 it was resolved to send them out again, and John Louis was to make a plan (a bark map)134 of the country they passed over.

49 As the funds of the Boeothick Institution were inadequate to pay for the expedition, members were asked to contribute. The number of subscribers had grown considerably since the inception of the institution and while there is no complete list of subscribers, The Royal Gazette of 24 June 1828 cited four additional vice-patrons and 27 possibly new members, all of whom would have made an annual payment or a donation. 135 More names were to be published in the following issue, which unfortunately has not been preserved.

50 The result of the second expedition was presented at a meeting of the institution in the fall of 1828. The three men had delivered a letter from Cormack, by then back in Newfoundland, to the French commodore at Croque Harbour, who knew nothing about the whereabouts of Beothuk. They then investigated White Bay and its hinterland without coming across any Beothuk, though old marks of their occupation were noted everywhere. Cormack concluded this “proves that the tribe, if not totally extinct, are expiring.”136 It was not considered prudent to send men out again.

Shanawdithit in Cormack’s Home, St. John’s, 1828

51 By the time John Louis and his men returned from their second unsuccessful search for Beothuk survivors, Cormack realized that Shanawdithit, who was still living with the Peytons, was the only person who could provide authentic information about her people’s history, language, and customs. Cormack considered it a priority to transfer her to St. John’s and obtain from her as much information as she was able and willing to convey.

52 It was presumably Cormack who asked John Stark and Andrew Pearce to sail to Exploits Island and take Shanawdithit to Twillingate. John Peyton Jr. was absent when they arrived and his wife refused to give permission, although a few days later she gave way and sent Shanawdithit to Twillingate. John Peyton Jr. was much displeased about Shanawdithit’s removal from his household, perhaps afraid that she would talk about his father’s murder of Beothuk 14 or 15 years ago.137 Cormack defended the transfer. He was obviously determined to salvage what she was able to communicate, and seems to have expected John Peyton Jr. to share these views, stating that it was “done for the best and with the best intentions.”138

53 Shanawdithit arrived at Cormack’s house at the Roope’s premises on 20 September 1828.139 In October, Cormack also hosted John Louis and his search party.140 Assuming responsibility for Shanawdithit’s well-being included having her vaccinated — on this matter John Stark wrote, “pray, let nothing prevent this”141 — and having Dr. Car-son look after her health.142 She was said to be suffering from consumption and during the nine months under the care of the Boeothick Institution she was often unwell.143 Cormack is believed to have commissioned the well-known artist, William Gosse, to paint a portrait of her.144 This portrait is now exhibited in The Rooms — her penetrating and reproachful look is striking; according to Cormack she “never laughed.”145

54 As Shanawdithit spoke little English, it became a priority for Cormack to instruct her. He also provided her with paper and pencils and found that she had a talent for drawing.146 When questioned about encounters of her people with Europeans, Shanawdithit produced sketches of certain events such as the arrival of Capt. Buchan’s party at a Beothuk camp on Red Indian Lake in the winter of 1810– 11, including the victory feast after two of Buchan’s men had been decapitated,147 and the taking of Demasduit (known as Mary March by the settlers) by the party of John Peyton Jr. and Sr.,148 and she also disclosed that in the encounter they not only killed Demasduit’s husband, Chief Nonosabasut, but also his brother. She sketched Buchan’s party going up the Exploits River with Demasduit’s remains149 and the location where a Beothuk woman was killed by Peyton Sr. “14 or 15 years ago.”150 Most revealing is Sketch IV, marking the camps of Beothuk families and their route as they moved from the Exploits River to the lakes inland from Badger Bay in March–April 1823.151 Cormack’s notes give further details of the situation of the Beothuk, their experiences with the English, a census of the different Beothuk groups in 1811, their decline and amalgamation, and the number of people who died prior to Shanawdithit’s capture, in 1823.152 At that time only 12 of her kin were left; she never narrated this part of her story without tears.

55 Shanawdithit also depicted Beothuk winter and summer mamateeks and other structures,153 a variety of animal food items,154 Beothuk objects, a woman in what appears to be a dancing dress,155 and “Emblems of Mythology,”156 as Cormack called them. Sketch X shows Cormack’s dwelling at Roope’s Plantation. 157 It is believed that before leaving Newfoundland Cormack gave these 10 drawings to members of prominent families in St. John’s. 158 When J.P. Howley became interested in the history of the Beothuk and collected material for his book The Beothucks or Red Indians, he was able to retrieve them.159 Cormack probably left additional sketches and information obtained from Shanawdithit with his friend John McGregor in Liverpool, with whom he stayed after his arrival in Britain in 1829. McGregor published the information anonymously in 1836,160 but the drawings have not been preserved.

56 In the course of Cormack’s conversations with Shanawdithit he collected about 120 Beothuk words not included in the vocabularies acquired earlier from Oubee161 and Demasduit.162 Then, in January 1829 he submitted what was probably an amalgamated list of Beothuk words from all three sources to the Natural History Society of Montreal as a token of his appreciation for having been elected corresponding member,163 saying that these words came from the Beothuk woman who was at that time living in his house. He also gave a copy of the word list to a Dr. Yates, probably Dr. James Yates,164 whom he might have known from his university days in Glasgow in 1811.

57 In early 1829, Cormack transferred Shanawdithit to the home of Attorney General James Simms and his family. As a parting gift she presented him with a rounded piece of granite, a piece of quartz, and a lock of her hair.165 When Dr. Carson’s medical ministrations could no longer halt the steady progress of her consumption she was moved to the St. John’s hospital located in the area of today’s Victoria Park.166

58 Shanawdithit died there and was buried in a cemetery on the South Side of St. John’s. Presumably this was the burial ground attached to the military hospital, located several hundred metres west of where the parish church of St. Mary the Virgin was built in 1859.167 A plaque attached to a cairn close to this church includes the words: “Near this spot is the burying place of Nancy Shanawdithit very probably the last of the aborigines who died June 6th 1829.”168

59 Among J.P. Howley’s papers is a poem of 11 four-lined stanzas entitled “The Indian Girl’s lament” with the note: “I have been favoured by Mr. W.H. Rennie with the following poem written by the celebrated New England poet, I.C. Whittier [should be J.G.], Haverhill, Mass. Nov. 1829, and inscribed to W.E. Cormack Esq. It refers to Shanawdithit ‘the last of the Beothucks, or Red Indians.’ Mr. Rennie received it from his cousin Mr. Charles Scott of Alverstoke, Hants.”169

Cormack’s Business Dissolves: His Final Departure from Newfoundland, 1829

60 At the same time as Cormack became involved in protecting the Beothuk, his business began to deteriorate. During the years 1827 and1828 advertisements in The Royal Gazette and The Public Ledger attest to the fact that Cormack & Co. continued with the consignment business.170 In May 1827, clothes, woollens, hosiery, cottons, silks, and linen, together with other goods suitable for spring, were advertised for sale.171 A couple of months later 400 bags of Hamburgh Bread, 100 barrels of Hamburgh flour, barrels of pork, red wine, fabrics, rugs, mitts, fox traps, and more were auctioned off on Cormack’s premises.172

61 Initially the sales may have gone well, but when Cormack started to offer dry goods the items he had chosen do not seem to have been popular. Listed in the final auctions were such items as flushing great coats and jackets, fancy waist coating, silk plaids, gentlemen’s and ladies’ silk stockings and kid gloves, crepe dresses and scarves, comforters, and items like a handsome grate, brass front, set of fire irons, kitchen oven complete, boxes of window glass, and ironmongery.173 Cormack would have had little experience in this type of business and his choices of silk clothing, for example, may not have been prudent. He may also have lacked business connections. His repeated stays in Scotland and his search for Beothuk survivors kept him away from St. John’s for several months at a time and would have had a detrimental effect on his business. The co-partnership with Thompson dissolved in January 1828.174 Thompson subsequently pursued his own business and did well, but for Cormack it appears to have accelerated his insolvency.

62 As previously planned, Cormack left the country on 14 January 1828175 to lay his report on the Boeothick Institution before Earl Bathurst and give the Beothuk artifacts he had collected to Professor Jameson in Edinburgh. Upon his return to St. John’s in May 1828, he advertised for rent the waterfront premises of Roope’s Plantation “at present occupied by the subscriber.” They included for immediate possession “an excellent wharf, good stores, a comfortable Dwelling House, and every other convenience suitable for carrying on a large business.”176 In May, two days were set aside for auctioning a long list of goods at the shop of W.E. Cormack.177 In May and June “Edinburgh Ale of very superior quality” was offered for sale and in September, J. Clift auctioned bread, tobacco, and snuff on Cormack’s premises.178

63 On 22 January 1829, shortly after Shanawdithit was transferred to the household of Attorney General James Simms, Cormack sailed on the brig Helen for Greenock, never to return to Newfoundland. 179 In May 1829 his business was declared insolvent,180 and R.R. Wakeham and H. Hawson were appointed provisional trustees of the estate. 181 New efforts were made to rent out the waterfront premises182 and, on 8 May, an auction took place at which “all stock in trade, consisting of shop and store goods and household furniture” were sold. . Also in May, a sheriff ’s sale to satisfy a suit by James and Wm. Stewart against Cormack included furniture and household items presumably from Cormack’s dwelling.183 In June all remaining items were sold by auction every Thursday and Saturday “until the whole is disposed of. By order of the Provisional Trustees of Wm. E. Cormack.”184 Later in the year the provisional trustees were replaced by Edward Blake and James Stewart.185 In September, a financial setback occurred when the Seven Sisters was lost at sea.186 In 1829, Cormack also sold his properties in PEI, including one town lot and two half town lots in Charlottetown, and two large pasture lots, the second one covering 72 acres in total; for sale were also five acres of land at the head of Rustico Bay.187

64 The liquidation of Cormack’s assets in St. John’s dragged on for another two years. In May 1830 “all the right, title and interest of William E. Cormack, Insolvent, in those extensive and desirable Waterside Premises and Land in this town — the interest of the Insolvent consists of one undivided third part of the said Premises” — were offered for sale.188 On 4 September Cormack’s share of the River Head Farm was purchased by David Stuart and James Gower Rennie as “executed by the Trustees of W.E. Cormack.”189 In July of the following year Cormack’s creditors were requested to make their claims and to meet in August at the office of the subscriber “when a statement of the estate will be exhibited, and a dividend of the funds declared.”190 However, Cormack was not entirely without income at this time. Eight lots with six houses and four shops were still part of the “Janet Cormack Estate” that continued to benefit all three of the Cormack children.191

65 It is suggested that around this time the “Scott and D.S. Rennie Estate” 192 as marked on the Plan of St. John’s193 (drawn up in 1849) came into existence. According to this plan, much of the waterfront land of Roope’s Plantation and 12 lots between Water and New Gower Streets194 were still owned by Janet Grace Scott (the sister of William Eppes Cormack and John Bell Cormack), while William E. and John Bell had sold their one-third shares to D.S. Rennie.

66 John Bell Cormack had run into financial difficulties in 1832 when he left Edinburgh “in haste” for PEI after the birth of his daughter, Anna Janet, in January 1831,195 and his marriage to Mary Ann Crawfuird, in April 1832.196 In his letters to his stepbrother, David Stuart Rennie,197 who worked in his law firm,198 John Bell thanked him for sorting out his affairs and trying to secure money owed to him. John Bell also told him that he wanted to leave the country altogether and move to PEI, and that to do so he needed 250 pounds sterling.

67 D.S. Rennie appears to have accepted ownership of John Bell’s shares in Roope’s Plantation, including the building lots that were originally part of it, in exchange for a loan of the money.199 John Bell and his family moved to PEI in 1833.

68 D.S. Rennie bought James Gower’s part of the River Head Farm in 1833 (together, they had purchased W.E. Cormack’s share in 1830), and presumably at that time or earlier W.E. Cormack had also sold his share of Roope’s Plantation to D.S. Rennie. These transactions would have led to negotiations with Janet Grace Scott (who still owned one-third of Roope’s) and the creation of the “Scott and D.S. Rennie Estate,” probably a trust.

69 In 1836 John Bell Cormack was admitted a “Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court” of PEI200 and his step-siblings subsequently gave him the power of attorney to represent their interests in PEI.201 He kept his shares in the River Head Farm and the property in the Victoria Park area (originally owned by his father) until 1848–49.202 John Bell Cormack and his wife eventually separated; his wife and their seven children moved to Boston while John Bell stayed in PEI but later returned to St. John’s, where he died in 1869.203

Cormack Moves Around the World, 1829–1868

70 England 1829 and Further Papers about Newfoundland Topics Cormack arrived in London in 1829 and hoped to obtain employment in the British government service. To that end, he submitted several documents to Sir George Murray, Secretary of State for the Colonies, among them his paper on the Newfoundland fisheries. He also offered “to cross and explore New Holland and New South Wales [in Australia] in any direction.” 204 Though Murray eventually granted him an interview, this did not lead to a government position. 205

71 In the following decade, Cormack continued research and writing. In early 1831, while living in PEI, he sent a paper, “On the Political and Commercial value of the Newfoundland and other North American Fishery,” to the Natural History Society in Montreal. This document, researched in the 1820s while he was still in Newfoundland, focused on the value of the island’s fisheries. The manuscript was read to the Society on 25 April 1831 and subsequently won an essay competition206 upon Cormack giving his permission that “the Society . . . expunge certain passages of a warm political bearing, and which, as a literary Society, devoted solely to the advancement of knowledge, they cannot sanction by their approbation.”207 The prize-winning paper is no longer in the archive of the Society and was never published. Secretary of State Murray sent a copy to the Board of Trade, which is now on file in the Board of Trade papers in The National Archives, Kew.208

72 In 1832–33, Cormack submitted a considerably longer report of his 1822 journey to the Natural History Society of Montreal. It consisted of 60 closely handwritten folio pages with a cover entitled, Narrative of a Journey across Newfoundland by W. E. Cormack (For the Natural History Society of Montreal).”209 The original of this narrative (without a map) is preserved in the archives of the McCord Museum. Although not the original field diary, it is nevertheless written in that format.

73 A notable addition to the longer 1832–33 version is the extensive information on flora from central eastern Newfoundland, including the colour of flowering plants that do not bloom during late fall when he had travelled across the island.210 In 1823, Cormack’s lack of information on this topic is confirmed by a letter from Robert Morison, assistant surgeon of HMS Sir Francis Drake and an avid botanist, to Sir William Hooker at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: “The few plants that W. Cormack took home [to Britain] from here [Newfoundland] I saw and named for him.”211 Cormack later told Hooker that Morison had “the best collection [of plants] that has been made in this quarter,"212 and urged him “to obtain the plants of our alpine district if they may be so called, at the South West and North West parts of the Island and of the Interior for there are plants there not to be found nearer the Sea Coast. I only saw a little of these districts in 1822, and did not or rather could not examine their plants.” 213 As it was, Hooker had already . received a “hortus siccus of Newfoundland >plants” from Morison.214 After Morison had died on Clapperton’s exploration of Central Africa, in December 1825, Cormack would have been able to gain unrestricted access to Morison’s plant collection, particularly as he was acquainted with Sir William Hooker,215 who was the Rennies’ neighbour on Bath Street in Glasgow.216 It is suggested that Cormack noted the names of many plants in the collection and included them in the manuscript of his 1822 trek for the Natural History Society, mostly in footnotes. While Cormack may have profited from studying Morison’s collection, his descriptions of Newfoundland plants in the various bio-zones in his “Narrative of a Journey” were likely based on knowledge he had accumulated in the years following his 1822 trek.217

74 Cormack continued with his interest in Newfoundland’s flora and sent plants collected in the vicinity of St. John’s to the Linnean Society in Britain.218 Twenty-one plant specimens included in a list of vascular plants from Newfoundland in the Herbarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew are also noted as coming from Cormack,219 and two specimens in the Grey Herbarium, also known as the Harvard University Herbarium, are listed as “collected by Cormack in Newfoundland between 1822 and 1829.”220

Canadian Maritimes, Early 1830s

75 Without work in England, Cormack moved to PEI where he established an export trade of grain to Britain.221 This was followed by a move to Cape Breton, since he stated on one of his lot conveyances in PEI that he was “at present residing in the Island of Cape Breton.”222 It is likely that Cormack became involved with the General Mining Association in Cape Breton Island, for he later claimed to have been “connected somewhat extensively with the opening and active management of coal mines.”223 Another of Cormack’s activities was that of agent for the New Brunswick and Nova Scotia Land Company,224 and in 1833 he became a citizen of Fredericton, New Brunswick.225 During the winter of 1833–34, Cormack went to Britain to consult with various parties on behalf of the Land Company and returned to Fredericton in 1834.226 However, when he came into conflict with W. Kendal, another agent of the Land Company, both men had to present their case to the Board of Directors in London. The Board agreed with Kendal’s argument and Cormack left the Company.

Australia, 1836

76 In May 1836, in the wake of this setback, Cormack emigrated to Australia,227 where he accepted the joint position of postmaster and clerk to the Bench of the Petty Sessions Court at Dungog, a farming district about 70 miles north of Sydney.228 However, a dispute with the police magistrate caused Cormack to resign and lease a farm at “East Bank, Croompark,” a few miles from Dungog.229 He successfully grew tobacco using convict labour,230 but in 1839, following another altercation with the police magistrate, Cormack came to believe that New Zealand would be a more promising place to settle.231

New Zealand, 1839

77 Cormack purchased several large tracts of land from the Maoris on New Zealand’s North Island along the Pararu, Piako, and Waipa rivers, for his own use and as agent for other land purchasers and investors. Some of this land was signed over to him in exchange for goods, including guns and ammunition that the Maori coveted.232 Then, in 1840, after Britain had claimed New Zealand through the Treaty of Waitangi with the Maori, a new Land Claim Act retroactively required all land purchases from Maori to be approved by a British Land Commission.233

78 This led to a trip to London in 1843 to apprise his partner, a Mr. Willis, and other investors of the developments.234 There he seems to have written his history “Of the Red Indians of Newfoundland,” including the story told by Shanawdithit, and also his “Geology and Mineralogy,” since both of these manuscripts were written on paper with the watermarks 1840 and 1843.235 Most likely he had left his notes on Newfoundland matters, collected in the 1820s, with his partner Willis before he had set off for Australia in 1836.236 During his sojourn in London Cormack also met Michael Faraday. Part of a conversation with him about his experiences in Newfoundland was published in The Correspondence of Michael Faraday. 237

79 After his return to New Zealand, Cormack was made justice of the peace in 1845.238 In due course he became embroiled in New Zealand politics and attempted, unsuccessfully, to influence British Parliament, through friends, to grant New Zealand representative government.239 While he was waiting for the Land Commission to come to a decision with regard to his land claims, Cormack opened a watchmaker’s shop in Auckland.240 He also purchased a 22-ton schooner, Roory O’More, to trade oil and whalebone,241 procured spars for the British Admiralty using Maori labour, and set up a mill for them in payment for their efforts.242 Eventually, most of Cormack’s land purchases were disallowed,243 a decision Cormack disputed unsuccessfully.244

England, 1849

80 Disillusioned by political machinations, Cormack turned his back on New Zealand for good and in 1849 once again returned to London.245 He brought with him a plant collection for Professor Hooker that was unfortunately spoiled on arrival when the glass cover of the case was broken. Only a kauri seedling survived.246 A few years earlier he had already sent seeds of 90 New Zealand plants.247 While in New Zealand, Cormack had also obtained a Moa bone, which he gave to Professor Richard Owen, conservator at the Hunterian Museum, who published a photograph of it and Cormack’s description of the “Locality of the remains of the Dinornis Giganteus” in his Memoirs on the Extinct Wingless Birds of New Zealand.248 Guided by a Maori, Cormack had found the bone on the northern part of the island, on a cliff above Opito Bay, next to an old Maori fireplace that was buried under three feet of sandy soil.

81 By this time Cormack was 53 years old, and while in London he amused himself by taking on yet another project, namely a booklet on ice-skating, at which he excelled.249The Art of Skating Practically Explained250was based on Robert Jones’s 1772 A Treatise on Skating.251Cormack revised and extended the text, added instructions for more complex figures on the ice, and gave directions for the construction of skates and for different methods of fixing them to the foot.252 He also used his time to burnish “with Dr. [Andrew] Ure and others his old Scotch lore in Metallurgy — Mineralogy etc.”253

California, 1851

82 After two years in London, for all indications with no employment, Cormack emigrated in the wake of the gold rush to California, where political developments were to his liking.254 He travelled by sea via New York to Panama, and from there on the SS California to San Francisco, arriving on 5 October 1851.255 Little is known about Cormack’s time in California. In January 1855 he held a job as postmaster in O’Byrnes Ferry, Calaveras County, and in the San Francisco city directories for 1856 to 1858 he is listed as a merchant living at 118 Sacramento Street.256

British Columbia, 1858

83 Cormack did not last in California either. By 1858 business in San Francisco had become curtailed and Cormack moved to British Columbia, which was experiencing a gold rush. Shortly after his arrival, in February 1859, he accepted the position of colonial secretary with Governor James Douglas.257 Two years later, he resigned from this job and advertised a variety of clothing, hardware, liquor, tobacco, and other items “for sale by the undersigned at the store of A.R. Green” — presumably sold on consignment under his name.258 Cormack also became a member of the first Municipal Council of New Westminster and as its chairman strongly advocated representative government for BC.259 According to a letter to the editor of the British Columbian, Cormack was credited with involvement in bringing young women from Britain to New Westminster for the purpose of providing marriage partners and/or domestics.260 In keeping with his concern for the Beothuk in Newfoundland, he became supportive of the local First Nations, applying for a building lot for a chapel and objecting to the local government’s acquittal of BC men involved in the killing and stabbing of First Nation individuals.261 In 1864 he became “Superintendent for Indian Demonstration” responsible for First Nations celebrations and the distribution of goods. 262 After a lengthy illness, Cormack died in New Westminster on 29 April 1868 and was buried in the small cemetery of Holy Trinity Church in that town.263

The Cormack Papers

84 Circumstantial evidence suggests that during Cormack’s time in London from 1849 to 1851 Newfoundland’s Surveyor-General, Joseph Noad, had tracked him down and communicated to him his interest in the Beothuk.264 Hence, before leaving Britain for California, Cormack dispatched his papers pertaining to Newfoundland and to the Beothuk to Noad in St. John’s and thereby finally severed his connection with this island.265 Noad had been working on a history of Newfoundland’s Indigenous people and was now able to add details gathered by Cormack from Shanawdithit. In January 1853 he presented a lecture on the Beothuk at a meeting of the Mechanic’s Institute to “a numerous and respectable audience.”266 It was published by The Patriot Press in the same year.267 Cormack’s papers included a more polished and longer version of his report on the 1822 trek than the “Narrative of a Journey” he sent to the Natural History Society in Montreal, with the plant names incorporated into the text. Recognizing the value of this document, Noad recommended to Governor Charles H. Darling to have it published. In 1856, at government expense, The Morning Post and the Commercial Journal printed the Narrative of a Journey across the Island of Newfoundland by W. E. Cormack, Esq. The only one ever performed by a European.268 On leaving the province in 1855, Noad placed the box of Cormack’s papers into the library of the Atheneum-Mechanic’s Institute.

85 In January 1881, at the first meeting of the Newfoundland Historical Society at the Atheneum library, Rev. Moses Harvey reported that on that morning an old box with papers about the transactions of the Boeothick Institution and other documents, as well as birchbark maps, had been found in the library.269 The box was placed in the hands of James Patrick Howley, at that time assistant to Alexander Murray on the Geological and Topographical Survey of Newfoundland, who had developed a particular interest in the Beothuk. At a follow-up meeting of the society,270 Howley announced that the box contained W.E. Cormack’s papers from his sojourn in Newfoundland in the 1820s and described its contents as a history of the Beothuk, proceedings of the Boeothick Institution, correspondence of its members, reports about searches for Beothuk survivors, and many small notes, some of them nearly illegible. There were also five bark maps. Howley published most of the information contained in these papers in his classic The Beothucks or Red Indians, in 1915.

86 When the late David Howley granted access to the Howley family archive it became clear that the Cormack material had become part of the Howley family papers. To facilitate the assessment of these papers, in 1984, Ingeborg Marshall created 81 file folders to organize the documents. The two main files concern Cormack’s diary of his trial walk with Joseph Sylvester (61 pages, small page size, not published)271 and the manuscript “Of the Red Indians” (22 folio-sized pages).272 Other files include correspondence of members of the Boeothick Institution, reports to the institution, notes on Newfoundland history, and about 30 files holding handwritten notes half a page in size or less. Most watermarks of the papers range from 1818 to 1828. A brief manuscript about the Beothuk people, starting with “On reflecting after my expedition in search of them . . .” has the watermark 1833.273 The manuscript on the “Geology and Mineralogy of Newfoundland”274 has the watermark 1843, and that ”Of the Red Indians of Newfoundland,” with the exception of page one, is written on paper with the watermarks 1840 and 1843.275 The paper of the “Preface” has the watermark 1828 and is in line with the introductory sentence: “To begin in the year 1828 to write a history of the Red Indians of Newfoundland is like beginning to write the history of an extinct people.” This page is followed by admonitions to the British government for its lack of protection of the Native population, a history of interactions between Beothuk and naval parties, the capture of Demasduit and of Shanawdithit and her mother and sister, leading to Shanawdithit’s disclosure of the story of her people and their movements over the country as well as of their decline, which was published by J.P. Howley in 1915.

87 The papers also include an “old worn map,” which turned out to be Steel’s Chart of Newfoundland, 1817, used by Cormack to mark the progress of his crossing in 1822.276 Of the five birchbark maps in the box, two were produced by James John, one outlining rivers and ponds from Bay d’Espoir to Island Pond277 and a second one with the route taken by Cormack and Sylvester from Meelpag Lake to George IV Lake within “20 miles to [illegible] Bay.”278 Three further bark maps were sketches of the rivers and ponds between Grand, Sheffield, and Red Indian lakes. These three maps were most likely drawn by John Louis, chief of the search party, on or after their trek in 1828. The third of these maps presents a clearer configuration of these lakes and the country to the north.279

Photograph of W.E. Cormack

88 There is also some information about a photograph of W.E. Cormack, which is not part of the Cormack Papers. Ernest Cormack Finch, solicitor in Britain and grandson of Cormack’s sister, Janet Grace Scott, owned a photograph that he believed to be that of his great-uncle.280 In 1931 he sent it to Robin J. Rennie of St. John’s (grandson of William Frederick Rennie). The cardboard backing of the photograph bore the name of a Southampton firm and the date “Oct/77” — well after the date of Cormack’s death in 1868. E.C. Finch surmised that this was a copy of an old photograph of Cormack, which an uncle in Southampton had asked a photographer to make. The name of W.E. Cormack on the back was written by Finch. 281 Robin Rennie had the photograph copied (by Miss Holloway) and sent the copy to the Secretary of the Legislature.282 A file in the Archive and Special Collections Division at Memorial University contains a photograph of W.E. Cormack with the inscription “Portrait of the late William Epps Cormack, Born at St. John’s, Nfld., 1796, Died at British Columbia, 1868, Author of ‘Journey across Newfoundland in 1822.’”283 It is the only known portrait of W.E. Cormack and has been widely reproduced, although there seems to be a shadow of doubt about its authenticity.

William Eppes Cormack’s Legacy

89 In the early 1820s, after Cormack and Sylvester had completed their walk across the island, there was little acknowledgement of their achievement. This changed in 1928 with F.A. Bruton’s reprinting of the report “for use in schools” — with the botanical names, a glossary, and other information neatly tucked into five appendices.284 The story of Cormack and Sylvester’s feat came to be standard fare in Newfoundland’s school curriculum.285

90 Cormack’s paramount legacy remains his information about the Beothuk. Compassion for this people prompted him to found the Boeothick Institution, search for Beothuk survivors inland, and obtain extensive information about the history and culture of the Beothuk from Shanawdithit. Her disclosures to Cormack remain invaluable ethnohistorical records.

91 Cormack’s achievements have also been acknowledged by naming geographical features and places after him. A mountain west of Middle Ridge is called Mount Cormack, and a lake north of King George IV Lake is named Cormack’s Lake.286 A spit of land at Flagstaff Pond is traditionally known as “Cormack’s Point,”287 and in 1948 a community in western Newfoundland was formally given the name “Cormack.”288 A school, streets, a square, a bridge, and business establishments bear his name,289 and a 182-km walking trail from St. George’s Bay across the rugged Anguille Mountains to Petites on the south coast has been named “Cormack Trail” in Cormack’s honour.290

92 Cormack and Sylvester’s journey has inspired any number of attempts to walk or drive or ski the same route. An extensively documented recreation of the journey was that undertaken by journalist Don Cayo and photographer Ray Fennelly in the fall of 1991.291 Though they occasionally used roads, their route meshed with that of Cormack and Sylvester, hitting some of the same high spots. The two men completed the journey in 39 days travelling a distance of close to 600 km. There were also three scouters of the 6th St. John’s Troop who “followed in Cormack’s steps” in 1960, walking largely on roads and railway beds.292 Eight men from central Newfoundland crossed the island on skidoos in 1971. It took the party 12 days to reach St. George’s Bay, and their odometers showed a distance of 568 km.293 The 27-man Assaults Pioneer Platoon from the Canadian Forces Base at Gagetown, New Brunswick, walked from Milton, Trinity Bay, to St. George’s Bay in September 1994 as a personal endurance test.294 And there were others.295

93 William Eppes Cormack was buried in the cemetery of Holy Trinity Church in New Westminster, BC. In time, the cemetery was neglected and in the early 1940s was levelled to make room for a school.296 Journalist Don Morris collected information on the grave’s whereabouts,297 and in 1986 a large, framed photograph with a commemorative text was unveiled at New Westminster’s City Hall and later moved to the museum of that town.298 The inscription reads: “In memory of William Eppes Cormack, born May 5, 1796: St. John’s, Newfoundland; died April 30, 1868;299 New Westminster, B.C. Explorer, Entrepreneur, Philanthropist, Agriculturist, Author. Whose name is honored in the country of his birth for his expedition across the Island of Newfoundland in 1822, and for his unremitting efforts on behalf of the Beothuk Indians of the Colony and their traditions, AND his life by this plaque, erected in the city of his burial, for his services in the promotion of the City of New Westminster, the Colony of British Columbia, and the enrichment of its life. Erected by the students of the W.E. Cormack Academy, Stephenville, Newfoundland.”300

94 In Newfoundland a memorial in Cormack’s honour has been established by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. It was originally placed near Cormack Bridge in Milton but later, with a new text, was moved to the road to Random Island. The memorial consists of a large boulder with a plaque attached to it. The text reads:

His friend and obituarist, John Robson, stated that “the impulse of a strong fancy made him a wanderer — the commercial man and the explorer in one. . . . He was naturally of a buoyant and happy disposition, genial and kindly; his manners were suave and dignified”302 — an apt summary of Cormack’s life journey and of his personality.

The authors are indebted to John Howley, St. John’s, who gave access to the privately held Cormack Papers. Appreciation is due to Michael Rennie, California, a descendant of the St. John’s Rennie family, who has shared important research material. Thanks are also due to Marianne P. Stopp, for deciphering Cormack’s papers, including the diary of his trial walk and for repeated edits of the manuscript, and to Suzanne Sexty, for her research assistance.