Article

The Whaling Station at Hawke Harbour, Labrador:

A Case Study in the Unsustainable Exploitation of Marine Natural Resources

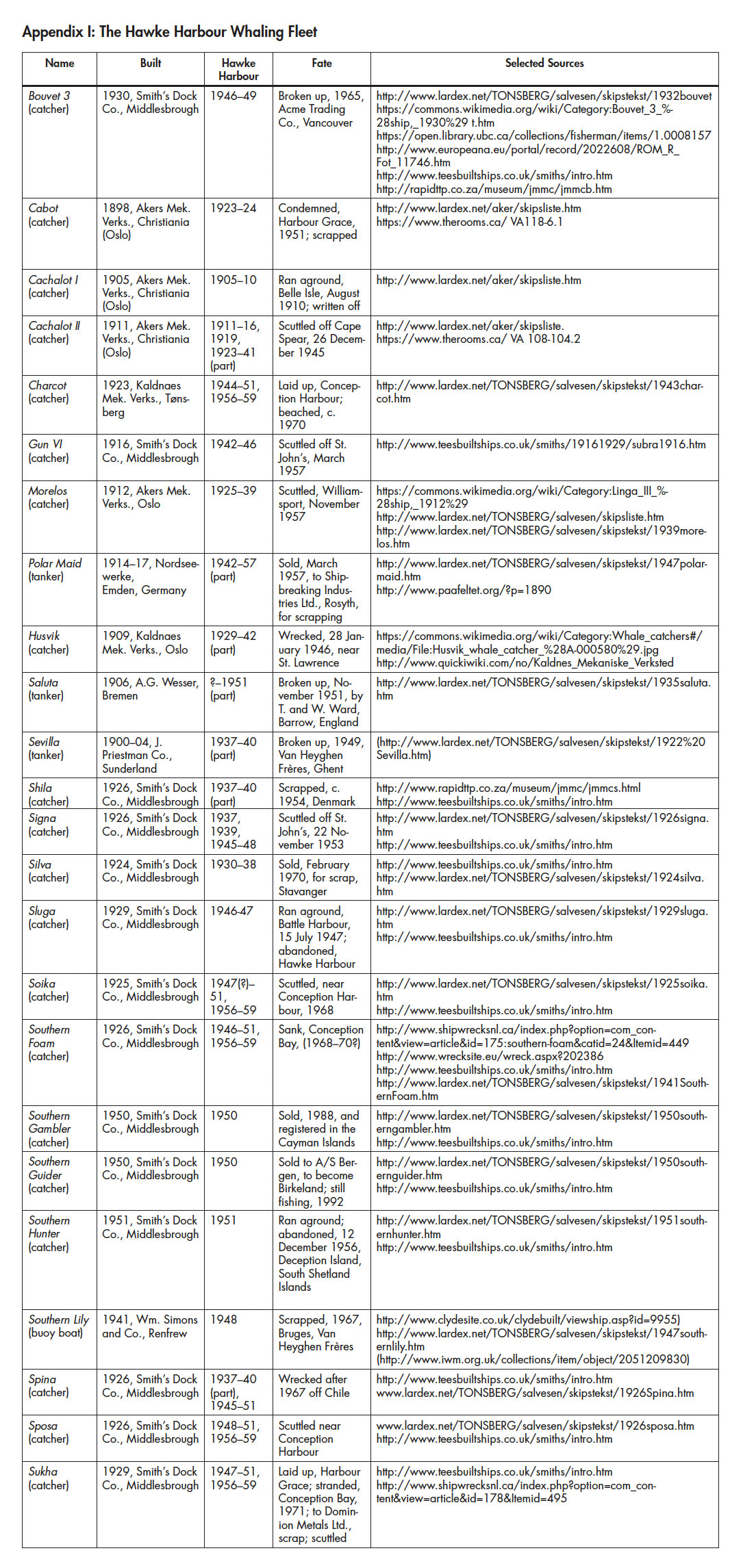

1 Four centuries of unregulated whaling reduced the numbers of slow-moving bowhead, northern right, and sperm whales to commercially uneconomic levels by the mid-nineteenth century. Faced with the need to utilize new stocks and species to continue what had been a profitable industry for many, methods and equipment were gradually developed to allow the capture of unexploited faster-swimming species such as blue, fin, humpback, and sei. These were combined in the mid-nineteenth century when the Norwegian sealer Svend Foyn mounted a cannon capable of firing a grenade-tipped harpoon onto the bow of a steam-driven catcher, bringing about the immediate transition from “traditional” to “modern” or “industrial” whaling. All the stocks of large whales now faced reduction, initially by vessels operating from shore stations, then from the mid-1920s by pelagic fleets of catchers supplying purpose-built factory ships.1 The effectiveness of the catcher–explosive harpoon combination was such that, in three decades, Norwegian whalers destroyed the stocks on their Finnmark hunting grounds, forcing them to spread their operations globally. The killing of a fin whale near Baccalieu Island on 26 June 18982 not only introduced modern industrial whaling to North America, but also briefly led to whaling replacing the spring seal fishery as Newfoundland’s most important industry after the salt cod trade.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

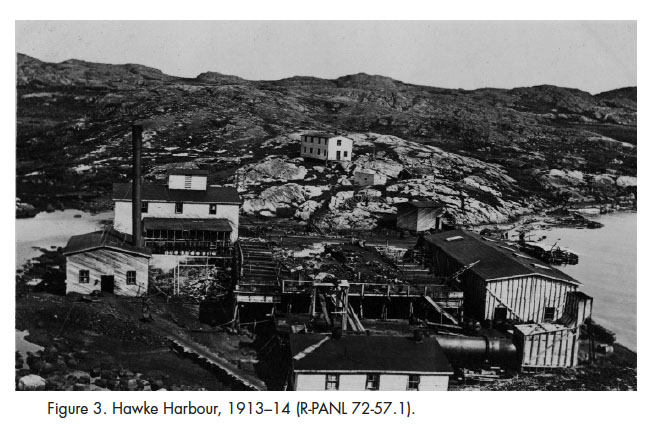

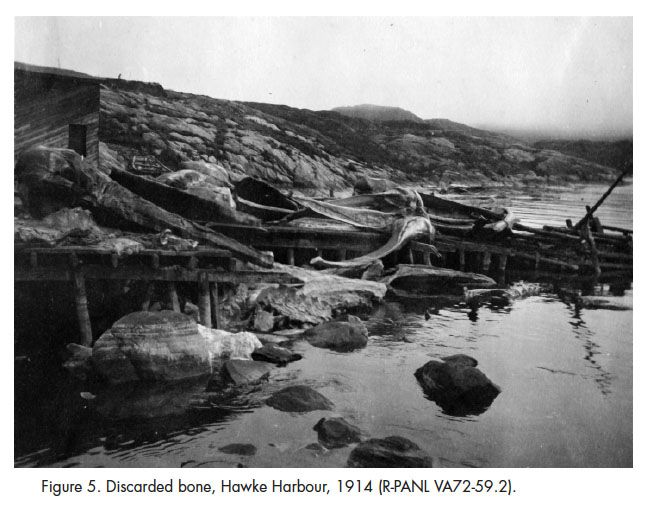

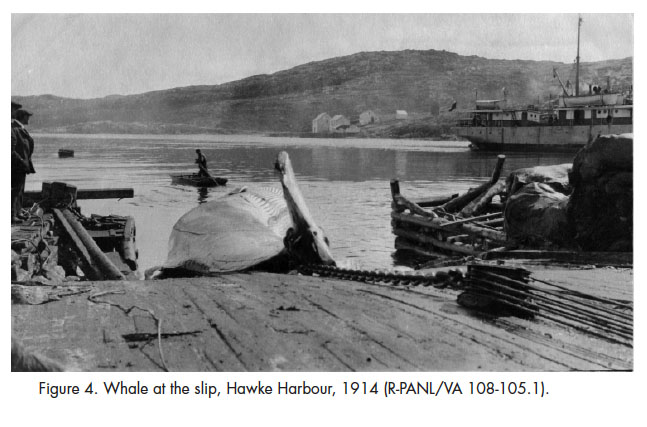

2 The lack of effective regulations and the search for quick profits made commercial whaling a cyclical process, with each phase involving the discovery and exploitation of a new or regenerated stock, subsequent competition and overexploitation, stock decline, and closure. Between 1898 and 1972, when the Canadian government placed a moratorium on non-Indigenous whaling, the Newfoundland and Labrador shore-based industry passed through four such phases3 (1898–1919; 1920–37; 1938–51; 1952–72) wherein at one time or another 27 mostly small and highly speculative companies operated 21 stations (Figure 1) and some 60 vessels (Appendix i: The Hawke Harbour Whaling Fleet) to process at least 20,000 whales, primarily (65 per cent) fin.

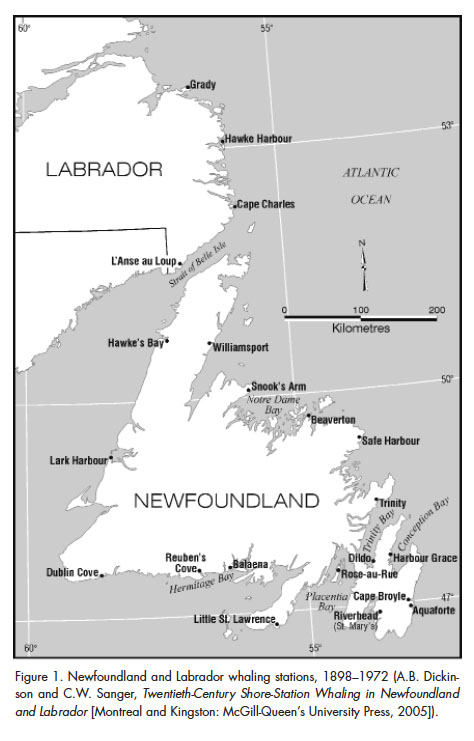

3 The industry reached Labrador in 1904 with the opening of stations at Cape Charles (1904–12) and L’Anse-au-Loup (1904–05), followed by Hawke Harbour (1905–59) (Figure 2) and Grady Island (1926–30). Only that at Hawke Harbour was successful, despite commencing at the peak of the industry, when 10 vessels working from 14 stations killed 1,275 whales, a pressure that could not be sustained. As a result, the catch per station declined by 40 per cent, from 91 in 1904 to 53 in 1905, and then by a further 50 per cent in 1906. Companies were dissolved or amalgamated, with the cessation of whaling, albeit temporarily, from Hawke Harbour in 1919 bringing an end to the first phase of the Newfoundland and Labrador industry.

4 However, Hawke Harbour was reactivated in 1923 because of the post-World War i demand for oil, the lack of competition, and its proximity to the northern migration limits of the whales, where blubber thickness and oil yield were at a maximum. Neither was there a resident human population to influence company operations by complaining to the government about noxious processing odours and pollution. These had been partly responsible for introduction of the 1902 Whaling Act, the first Newfoundland legislation, albeit ineffective, to regulate the industry. Furthermore, only a handful of summer fishermen might be inconvenienced by catcher activities, another contributory factor to the Act.4 Conversely, the remote location and harsh climate provided construction, maintenance, operational, and financial challenges not faced by companies operating further south.

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

5 Newfoundland was essentially a tabula rasa for commercial whaling when the Cabot Steam Whaling Co. opened the first station, at Snook’s Arm in Notre Dame Bay, in 1898.5 Subsequent companies were forced to widely disperse their properties to minimize competition and maximize profits, an ad hoc strategy later reinforced by the Whaling Act when it prohibited stations being built within 50 miles of each other. The lack of specificity as to how this was to be measured, by terrestrial or nautical miles, or in a direct line, led to confusion and complaint, and resulted in the Ministry of Marine and Fisheries defining catching zones for each station.6 Late entrants to the industry, and those wishing to expand their operations during these early boom years, found themselves occupying increasingly remote locations on the island, and eventually Labrador. Hawke Harbour proved, in fact, to be the most advantageously situated of the stations active in 1906, processing 60 whales for 1,260 barrels (64 imperial gallons per barrel, 6 barrels per ton), an average yield of 21 per whale compared to, for example, 681 barrels (10 per whale) produced from 67 caught from Rose-au-Rue in Placentia Bay.

The Labrador Whaling and Manufacturing Co. Ltd. (1905–16, 1919)

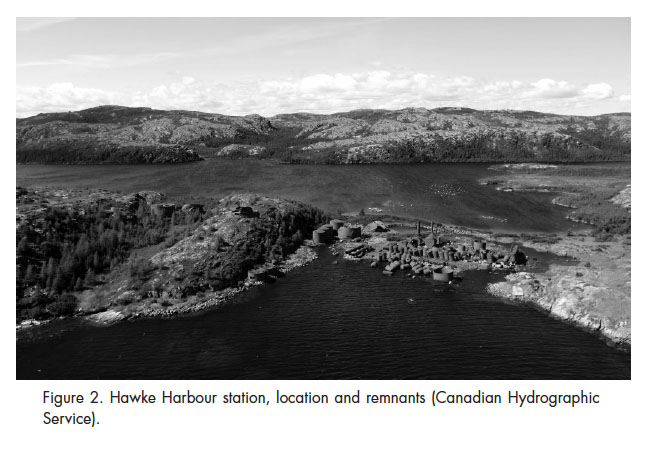

6 Whaling began from Hawke Harbour (Figures 3, 4, and 5) after Daniel Ryan, one of the colony’s wealthiest merchants and a member of the House of Assembly, had an application to the government for a station operating licence approved in February 1903. In the rush by investors to achieve profits already reaching 20 per cent annually, 46 such submissions were received between 6 December 1902 and 27 November 1903, including for renewal of the annual $1,500 licence fee imposed by the 1902 Act on 10 stations previously approved (Aquaforte, Balaena, Cape Broyle, Cape Charles, L’Anse-au-Loup, Little St. Lawrence, Reuben’s Cove, Riverhead, Rose-au-Rue, Snook’s Arm). Only eight of the 35 new applications were successful (Beaverton, Dublin Cove, Harbour Grace, Hawke Harbour, Hawke’s Bay, Lark Harbour, Safe Harbour, Trinity), with Hawke Harbour being the sole one of 13 applications submitted for Labrador, perhaps an indication of Ryan’s business and political status. Consequently, by July 1904 he was able to incorporate the Labrador Whaling and Manufacturing Co. with the Newfoundland Railway magnate W.D. Reid as its major shareholder and supplier of the station’s boilers.7 Like most of these early companies, the limited capital available from the small local business community necessitated many individuals buying small numbers of $100 shares and hedging their investments in different operations.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

7 Operations began after the new Norwegian-built catcher, Cachalot I, arrived from St. John’s in late May 1905 with experienced whale men from Placentia Bay, most likely previously employed at the Rose-au-Rue station that had opened in 1902.8 However, this first season at Hawke Harbour was not as successful as Ryan probably hoped for. Severe ice and fog restricted catching,9 resulting in only 70 whales being taken for just 8 per cent of the industry’s catch. Also mitigating was the need for several of the catcher crew to remain ashore while being treated for “dropsy” at Dr. Wilfred Grenfell’s recently completed hospital at Battle Harbour.10

8 Unlike other companies active in the industry, the catch of at least 123 whales during the next two seasons allowed Ryan’s company to declare a 15 per cent dividend in 1907 and hold back $2,000 to support future operations. An increased catch of 100 whales in 1908 permitted a further 17.5 per cent payment and banking of an additional $3,000.11 Revenue was also gained by supplying American Arctic expeditions, such as those led by Lieut. Robert Edwin Peary, with whale meat for sledge-dog food.12

9 Although the 1909 hunt was disrupted when Cachalot I damaged its propeller,13 the 74 whales processed further increased the dividend. However, disaster struck on 25 August 1910 when the vessel ran aground on the eastern end of Belle Isle, making it a complete loss after taking only 33 whales, ultimately the total for the season.14 A more powerful and ice-strengthened replacement, Cachalot II,15 was ordered from Akers Mek.Verks. of Christiania (Oslo),16 a move indicative of Ryan’s positive outlook for the future of his station. The new vessel arrived in St. John’s on 6 June 1911, but could only catch 51 because of heavy ice,17 a continuing factor in further reducing the catch to 37 in 1913. However, the major contribution to this catch decline was probably overexploitation, as observers noted there “has never been seen before such a scarcity of whales on the Labrador.”18

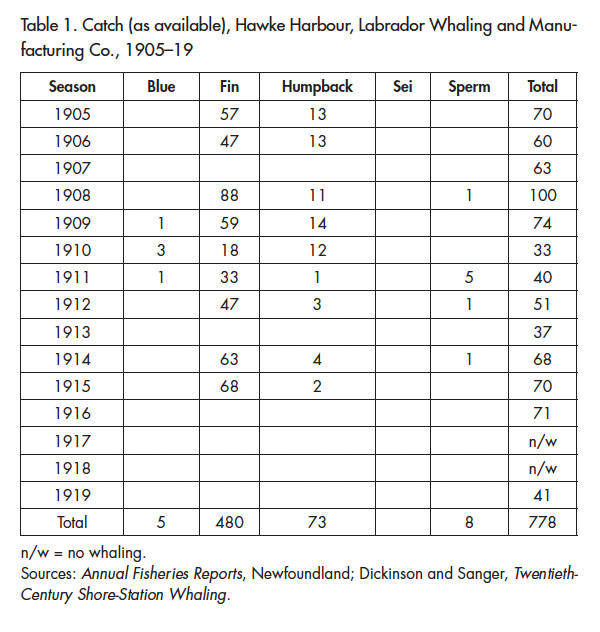

10 Although there is no contemporary objective evidence for depleted stocks, all the stations closed by 1916, even though the average oil price rose from £14 per barrel (1905) to £30 (1916)19 and the United Kingdom called for increased production to meet the wartime demand, especially to make margarine and glycerine for explosives.20 Despite the earlier optimism shown by ordering a new catcher, Ryan now decided that whaling was too uncertain a business and also withdrew from the industry.21 Not surprisingly, it was impossible for him to sell the station, but he was able to lease Cachalot II to the Newfoundland government for fishery patrols until 1919. Following a continuing rise in the oil price to £57 in 1918, he reopened Hawke Harbour in the hope that stocks might have recovered enough to support a smaller operation.22 But since the gestation period of fin and blue whales is 10–12 months, and sexual maturity is not attained until at least six years, this assumption was unwarranted. Only some 41 were processed, and despite an oil price of £67 (1919), his operating expenses were probably not covered. Consequently, the Labrador Whaling and Manufacturing Co. abandoned Hawke Harbour at the end of that season after taking 778 whales since 1905 (Table 1). As Ryan had earlier pronounced in the House of Assembly when summarizing the volatile industry:

Display large image of Table 1

Display large image of Table 1The Newfoundland Whaling Co. Ltd., 1923–37

11 After Hawke Harbour closed in 1919, the Newfoundland and Labrador industry entered a period of quiescence as oil prices declined again (£31, 1923). However, an expatriate Norwegian, Capt. Amund Anon-sen,24 previously the master-gunner of Cachalot I and II, decided that the absence of competition and the potential for price increases as the Antarctic pelagic industry expanded might make a limited industry feasible.25 Therefore, in June 1923 he bought the dormant properties at Beaverton, Cape Broyle, Hawke Harbour, and Rose-au-Rue, and the catchers Cabot and Cachalot II, all now owned by Ryan, for the Newfoundland Whaling Co., which he incorporated on 17 July 1923.26

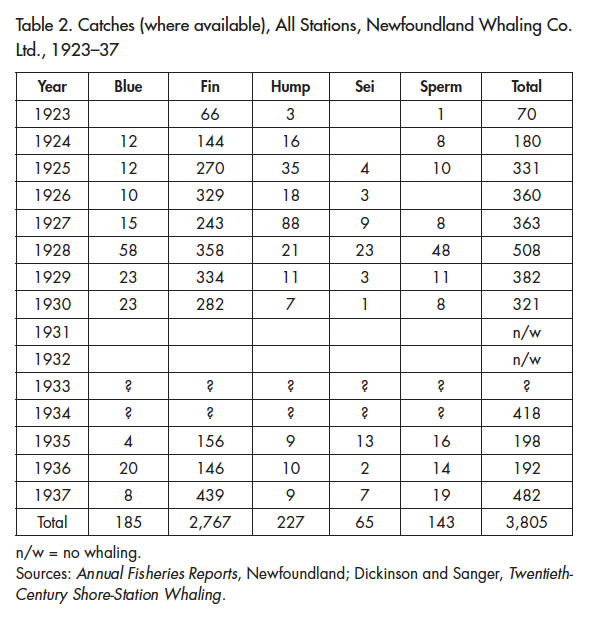

12 Since Rose-au-Rue and Hawke Harbour needed substantial repairs after lying idle from 1915 to 1919, Anonsen opened only Beaverton while the others were being refurbished. This done, and although 70 whales were taken in 1923, he then closed it in favour of using the better-situated Hawke Harbour and Rose-au-Rue, a move that yielded 180 whales in 1924 (Table 2) when the oil price had, in fact, risen slightly to £37 per ton.27 Encouraged by this success, and thinking for the long term, Anonsen decided that rather than pay dividends he would reinvest in the company by upgrading Hawke Harbour and buying a larger catcher, Morelos, to work with Cachalot II on the northern grounds while the older Cabot hunted from Rose-au-Rue in the more sheltered waters of Placentia Bay.28

13 This catching strategy and the decision to reinvest in better equipment contributed to a catch of 508 whales from the company’s two stations in 1928,29 which, despite a fall in the oil price to £30 per ton as a result of oversupply from Antarctica, convinced him to buy yet another catcher, Husvik (renamed Rio Sama), the following year. However, it is unlikely that the stocks had recovered enough in the years when there was no hunting to sustain this level of catching, and they again declined sharply.30 Global oil prices continued to fall, forcing Anonsen to close his stations in late 1930 with the oil price at £21, a particularly unfortunate move for those attracted by the seasonal employment, as well as for the Newfoundland economy in general. The importance of Hawke Harbour for those living nearby had been demonstrated in 1925, for example, when a family that lost its fishing stages and equipment in November storms was provided with winter supplies by the company.31 On the wider front, the station employed 203 men in 1927, mainly from the island, to produce oil valued at $277,500 and dried meat and bone meal (guano) worth $44,400.32

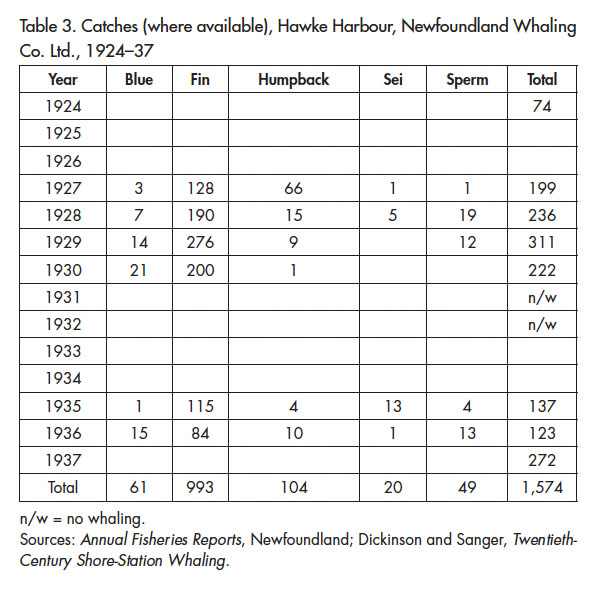

14 Faced with decreased catches, and oil at its lowest price of £12 a ton, the Newfoundland Whaling Co. was liquidated in 1931. The properties and vessels were bought for $48,000 by Anonsen and several former directors who still believed that whaling was viable.33 Only Hawke Harbour was reopened in 1933, but the company still could not profit because of a storm-delayed start to whaling, the costly renovations needed after the station had been idle for two years,34 and the oil price remaining at £12. Consequently, the company was again wound up in 1934, then reorganized for a third time with the help of St. John’s businessmen Chesley A. Crosbie and Capt. Olaf Olsen, a Norwegian resident in St. John’s with extensive local maritime and whaling experience.35 Although the post-depression oil prices began to improve (£15, 1934; £20, 1937), it was clear that whaling could not continue without financial input from outside Newfoundland. Despite having processed 198 whales at Hawke Harbour and Rose-au-Rue in 1935 (Table 2), including 137 at the former (Table 3), the directors decided to seek help from the world’s largest whaling company, Christian Salvesen and Co. Ltd. of Leith, Scotland.36

15 Salvesen agreed to a partnership, placed family members on the Board of Directors, provided funds for the 1936 and 1937 seasons, and retained Anonsen as whaling manager.37 However, the goal was to gain full control, and after fractious discussions and negotiations with the local board members, Salvesen petitioned the Supreme Court of Newfoundland to let his company take over the Newfoundland Whaling Co. Approval was given on 12 August 1938 conditional on payment of $300,000 to the creditors.38 The assets at Hawke Harbour, Rose-au-Rue, and Grady and land at Beaverton and Cape Broyle were advertised for sale,39 and bought by Salvesen on 24 November 1939 for the requisite $300,000. Ownership had now gone overseas, only the second time that a local whaling station had been operated by a non-Newfoundland company, the other being at Aquaforte (1902–08).40

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 2 Display large image of Table 3

Display large image of Table 316 Salvesen’s presence in Labrador renewed the company’s whaling activity in the North Atlantic, which had ended when its station at Olna Firth, Shetland Islands (1904–29), closed. Since the United Kingdom’s Whaling Industry (Regulation) Act, 1934, prohibited whaling within its coastal waters, this new opportunity was fortuitous, making it possible for Salvesen to return to the northern hemisphere and profit from the edible oil demand of the post-depression economic recovery. Production from the company’s primary southern hemisphere operations at Leith Harbour, South Georgia, and Saldanha Bay, South Africa, and the pelagic fleet, could be supplemented when those were inactive during the austral winter. Able to process up to eight whales daily, Hawke Harbour was equipped with 24 pressure cookers, a factory for producing meat and bone meal, two centrifugal separators for removing residual oil from pulverized meat and other body parts, and had a storage capacity of 1,000 barrels of oil. Before Salvesen took control, the Newfoundland Whaling Co. processed some 3,805 whales from 1924, including at least 1,574 from Hawke Harbour. Particularly noticeable was the increased catch of blue whales (c. 5: 1905–19; c. 185: 1924–37), although some 70 per cent were caught from Rose-au-Rue, closer to their migration route. The arrival of Salvesen served not only to continue the industry, but also to further increase the hunting pressure on the stocks, especially on the blue whales.

Polar Whaling Co. Ltd., 1939–51

17 Having gained control of the Newfoundland Whaling Co., Salvesen dismissed Anonsen and made its subsidiary, Polar Whaling Co., responsible for operating Hawke Harbour and Rose-au-Rue. Represented by A.H. Murray and Co. of St. John’s, the company established its headquarters and catcher repair and overwintering base at Harbour Grace on the yard site of the Newfoundland Shipbuilding Co., 1917–19.41 Other stations obtained during the purchase were abandoned. The influx of capital, equipment, and expertise included catchers and masters- gunners from Salvesen’s southern hemisphere operations, major contributors to both revival of the industry and depletion of the stocks.42 The station also provided a training site for those about to hunt elsewhere for Salvesen, and for testing equipment such as the transmitters implanted into carcasses so that they could be retrieved by buoy-boats, and for developing improved materials such as lighter, more flexible nylon foregoers, the connection between the harpoon and whale line. Some Newfoundlanders also gained more experience by working in the Antarctic; in 1939, for instance, men from Placentia Bay went there on one of the company’s floating factories.43

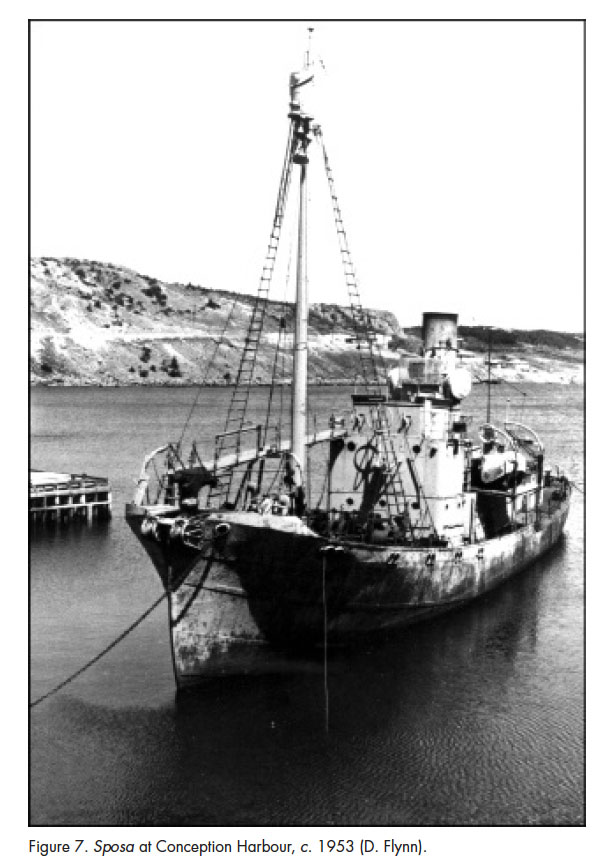

18 The Polar Whaling Co. began hunting from Hawke Harbour in 1939, but operations temporarily ended the following year when the British Ministry of Shipping requisitioned the catchers Shila, Signa, Silva, Spina, and Sposa into the Royal Navy for wartime convoy duties and coastal defence. This temporary cessation also provided the opportunity to sell two older catchers, Cachalot II and Morelos, and the station at Rose-au-Rue to Marine Oils Ltd., owned by ex-Newfoundland Whaling Co. director Capt. Olaf Olsen.44 The elderly Husvik was bought by Capt. Johan Carlson Borgen, the company’s chief gunner and master of Signa.45

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

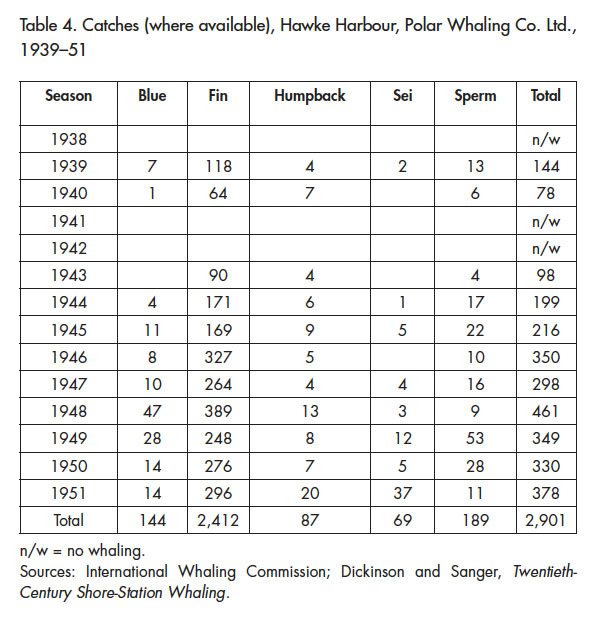

19 The loss of catchers and the hazards of operating in the contested waters of the North Atlantic caused Hawke Harbour to remain closed until 1943, when the decreased German submarine presence after the Battle of the Atlantic (1940–43), the loss of much of its southern pelagic fleet through enemy action, and the ongoing need for edible oils in the United Kingdom led Salvesen to reopen the station.46 The processing capacity was increased, and two newer and more powerful catchers, Charcot and Gun VI , were permanently transferred from South Georgia. The requisitioned catchers were decommissioned by the Royal Navy in 1944, and those that could be refurbished for whaling returned to Hawke Harbour.47 This revitalized fleet, and the seasonal use of highly experienced Norwegian crews and catchers from the south, markedly increased the catch from 199 in 1944 to a peak of 461 in 1948 (Table 4).

20 Despite the introduction in 1946 of more exacting controls on global whaling by the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (icrw) and the formation of the International Whaling Commission (iwc) to monitor compliance and effectiveness,48 the renewed pressure placed on stocks by the expanded hunt caused catches to decline yet again. Hunting moved further offshore, increasing operating costs,49 and more of the smaller, immature, lower-yielding whales, especially sei, were caught. Although the average oil price rose from £43 (1943) to £141 (1951) per ton, Salvesen was forced to close the station in October 1951. Factors such as the inability to profitably produce enough oil despite the then record high price, falling demand as plant oils replaced edible marine oils in products such as margarine, and the increased availability and use of butter, all combined to bring about this decision.50 The company’s other operations were soon similarly affected. Leith Harbour closed at the end of the 1960–61 season, and the company’s last factory ship, Southern Harvester, made its final voyage in 1962–63 before being sold to Nippon Suisan Kaisha (nsk) of Japan in July 1963 for her catch quota.51 At least 2,901 whales had been taken from Hawke Harbour by the Polar Whaling Co., by far the biggest catch for any company or station in the Newfoundland and Labrador whaling industry.

Display large image of Table 4

Display large image of Table 4Hawke Harbour Whaling Co. Ltd., 1956–59

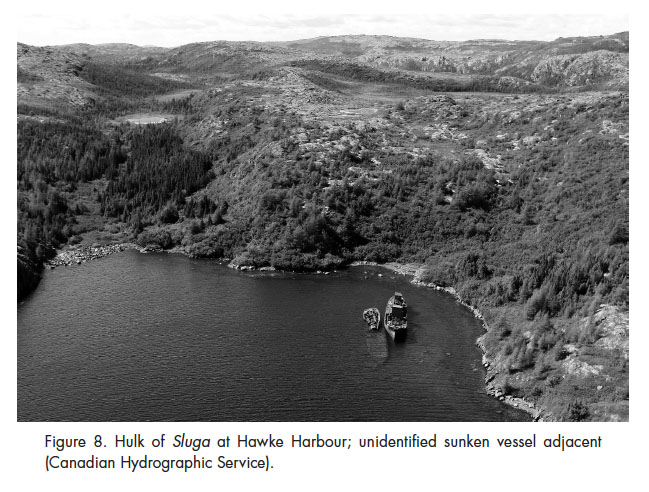

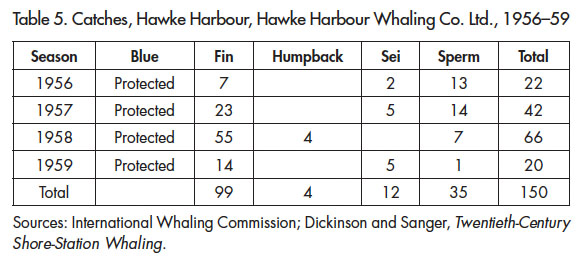

21 The departure of Salvesen did not mark the end of whaling from Hawke Harbour. On 24 August 1956, former chief gunner Capt. Johan Carlson Borgen52 formed the Hawke Harbour Whaling Co., believing, as had Anonsen, that a small operation might be profitable, especially since oil prices, although declining, were still high (£89 per ton in 1956). Furthermore, the development of fox and mink ranching in Trinity Bay during the early 1950s had opened up a market for whale meat.53 Although the industry was largely supplied from the onshore drive of pilot (pothead) whales, the sustainability of this stock, and thus the fur industry, was being threatened by large catches, some 36,500 in the years 1951–57. Borgen realized that despite their decreased availability, the large whales still seasonally found off Labrador might complement potheads as a source of meat for the mink and fox farms. Unfortunately, the animal feed market did not improve as fur farms closed due to increased operating cost. Whether or not whaling could have continued at Hawke Harbour for much longer was resolved when the station was destroyed by fire on 12 September 1959.54 Only 150 whales had been taken (Table 5), using at different times the catchers Charcot, Soika, Southern Foam, Sposa, and Sukha, which Borgen had also obtained from the Polar Whaling Co. A proposal from a speculative new enterprise, the Newfoundland American Whaling Co. Ltd., to rebuild the station failed because capital could not be raised. Whaling from Hawke Harbour permanently ended.55

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Table 5

Display large image of Table 5Unsustainable Exploitation

22 The whaling operations at Hawke Harbour reflected the history and methodology of the industry globally. Unfortunately, they had a significant cumulative negative impact on the seasonally occurring stocks, but particularly during and immediately after World War ii when more aggressive catching methods and expertise were introduced. Although there are little objective data, there can be no doubt that this continuing and increased pressure led to overexploitation, especially of the small stock of high-yielding blue whales. After Confederation, the government of Canada assumed responsibility for fisheries and oceans management in the province and stationed an inspector at Hawke Harbour to monitor compliance with the iwc regulations. Infractions were frequent, the 1950 and 1951 reports, for example, identifying the killing of whales below the minimum lengths set out by the Commission as indicators of sexual maturity, and of pregnant or lactating females. Twenty- one of 81 (26 per cent) of the blue whales caught in July 1950 fell into the former category. There was also little incentive for the gunners not to kill prohibited whales, since although not credited to their catch bonuses, the oil produced was counted as part of the total production and reflected in the bonuses paid to shore employees, including the managers. The pursuit of scarce blue whales further south into the Gulf of St. Lawrence was also of questionable value, since the increased bacterial decomposition of the blubber and body tissues during the often extended return voyage with a carcass led to an inferior and less valuable oil being produced. As the inspector presciently observed: “Within another three seasons at the present decreasing kill of blues [1947, 10; 1948, 47; 1949, 28; 1950, 14; 1951, 14] they too will be as the Greenland right or bowhead whale, practically extinct.”56 The Polar Whaling Co. thus continued to reduce a population whose estimated pre-whaling number of some 1,500, was now “in the low hundreds” and designated “endangered” by cosewic, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada.57 Once the Strait of Belle Isle blue whale hunt finished in July, the catchers moved elsewhere to repeat the process on humpbacks, which by the 1949 and 1950 seasons comprised only eight of the 349 whales taken. Both blue and humpback whales were belatedly protected by the iwc in 1955.

23 No action was taken against Salvesen for these depredations, but the company and the government of Canada were aware of the content of the inspector’s reports. The need to react was forestalled by the departure of Salvesen at the end of the 1951 season. Although the inspector at Hawke Harbour was required to take organ samples from carcasses so that federal scientists could determine the age structure of the catch and populations, no concerted or meaningful attempts to determine these parameters were made until commercial large-species whaling resumed in 1963 from stations at South Dildo and Williams-port. This renewal of the industry provided the opportunity, through tagging and observation cruises and carcass sampling, to gather more objective data on the status of the western North Atlantic stock of fin whales, the only commercially significant non-protected species available. As a result, the first attempt was made to conserve this stock by imposing an annual catch quota on each station, which continued to be reduced as catches and biological data showed continuing decline. This and the international opposition to whaling caused the government of Canada to close the industry at the end of the 1972 season.

Conclusion

24 Between its opening in 1905 and closing 54 years later, Hawke Harbour processed approximately 5,500 whales, more than 25 per cent of the catch from the 21 stations that operated at one time or another between 1898 and 1972. It was also the only station to participate in the three revivals of the industry after the first phase ended in 1919, and in so doing it became a major contributor to reducing the local stocks. Nonetheless, it did influence the overall economy of Newfoundland and Labrador through the production, export, and sale of whale oil, bone, guano, and animal feed, and provided much-needed seasonal and well-paying employment to help free many families from the crippling grip of a predominantly fisheries-based subsistence economy. Although important to the small number of residents of southern Labrador, its major influence was felt in communities in southeastern Newfoundland. The Trinity and Placentia areas provided much of the labour and benefited from the expenditure of wages, while Harbour Grace profited from being a repair and overwintering base for the catchers. The bottom of Trinity Bay became a vibrant fur farming region partly as a result of the whale meat processing activities of the Newfoundland Fur Farmers Feed Cooperative at South Dildo, supplied in part from Hawke Harbour. Indirectly therefore, the station helped to shape the cultural and economic fabric of these important towns and regions.

25 The recent growth of environmental, cultural, and historical tourism in the province is, in part, fostered by the increased occurrence of some whale species, particularly the once depleted humpbacks. Commercial whale watching and a related tour boat industry flourishes in several communities, and whereas the originally poorly legislated commercial whaling proved to be unsustainable, this new well-regulated use of whales reverses the situation.

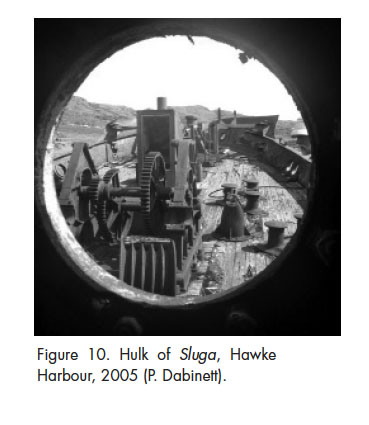

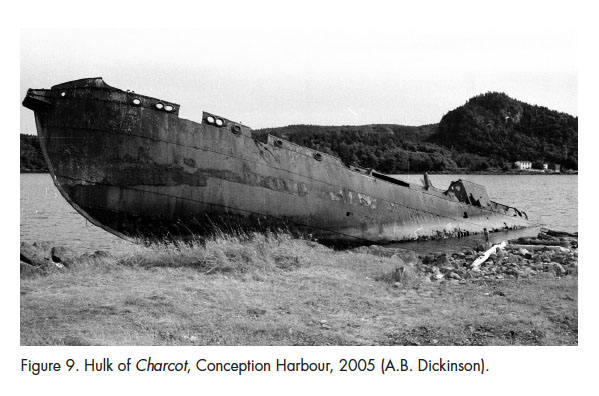

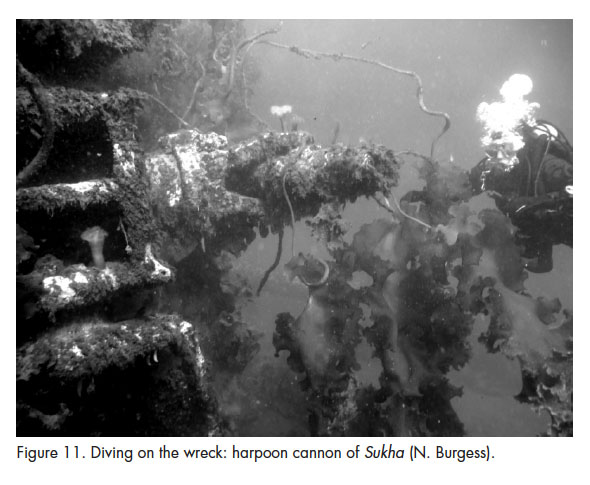

26 The remnants of whaling stations and sites are of additional interest. Although Hawke Harbour and its relics are accessible only by boat, the derelict and demolished structures and the hulks of catchers have become increasingly attractive to visitors, especially summer yachters. On the island, there is growing interest in those Hawke Harbour Whaling Co. catchers beached or sunk in Conception Bay. The stranded wreck of the Charcot near Conception Harbour (Figure 9) provides photographic opportunities, and the nearby underwater remains of Sukha and Southern Foam are promoting wreck diving.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11