Articles

The Resettlement of Pushthrough, Newfoundland, in 1969

INTRODUCTION

1 One of the largest internal state-sponsored migrations of people within Canada occurred in Newfoundland and Labrador between 1954 and 1975.1 Some 300 rural communities were vacated and 30,000 people relocated to larger communities, greatly reshaping settlement distributions and patterns in outport regions, particularly along the south coast, in Placentia, Bonavista, and Notre Dame bays, and on the southeast coast of Labrador. Many who moved under the program welcomed their relocation from small, isolated outports as improving immensely their social and economic prospects even if their communities were dismembered in the process. There was little public opposition until the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the program had largely run its course. Resettlement then became a cause célèbre of what journalist and writer Sandra Gwyn called the Newfoundland cultural renaissance, led primarily by a St. John’s artistic and intellectual class that considered resettlement a misguided policy imposed by callous state elites, insensitive social and economic planners, and ill-informed politicians that recklessly interfered in the lives of ordinary, hard-working people.2 It indicted Joseph R. Smallwood, the province’s Premier from 1949 to 1972, for his failure to appreciate the uniqueness of outport life in his relentless search for modernity and North American consumer culture.3 His attempt to change the spatial patterns of settlement through the depopulation of isolated settlements did not simply threatened the physical, social, and cultural landscapes of the past, they argued, but was paramount to destroying a people by obliterating its culture, history, and traditions. Resettlement represented social engineering at its most arrogant: it devalued outport life and its pluralistic economy, which had traditionally defined rural Newfoundland, and privileged an urban society with its educated and specialized workforce. Historian Jerry Bannister has observed that “At the heart of this perspective was the belief that the island’s golden age lay not in a modern future of material wealth but in an idyllic past of outport culture.”4

2 Some of the criticism was also excessively outrageous, even if resettlement did promote particular ways of living. In 1971, for instance, the Evening Telegram compared resettlement to Hitler’s treatment of the Jews two decades earlier. Columnist Ray Guy, a native of Placentia Bay, an area much affected by resettlement, termed it “one of the greatest crimes committed against the Newfoundland people,”5 and Canadian writer Farley Mowat, then living in Burgeo, compared resettlement to the harsh eighteenth-century Highland clearances in Scotland.6 Two Memorial University professors composed a ballad to their colleague, Parzival Copes, an outspoken economist and proponent of resettlement, promising his executioners safe passage through the pearly gates of heaven.7 Much of the excess of the early critics has waned, and the history of resettlement is now largely in the hands of novelists, playwrights, poets, and songwriters. Collectively, their memory of resettlement fosters a sense of nostalgia about the depopulated outports. Still, resettlement is an important event in Newfoundland and Labrador, and in 2012 the province’s Historic Commemorations Program recognized it for its cultural and historical significance.8

3 An analysis of the political process around resettlement that involved federal and provincial politicians and bureaucrats might demonstrate that the policies articulated and implemented were an attempt to deal rationally with the demands of citizens who lived in Newfoundland and Labrador in the 1950s and 1960s. Perhaps, resettlement yielded the greatest net benefit and achieved the goals and objectives for both state and citizen alike, especially at a time when the role of the state was growing. Resettlement might have been the appropriate policy to deal rationally with the social and economic conditions existing in Newfoundland at the time. What might also be true is that the people most affected by the policy determined the outcome even if they did not set the agenda. Or none of this may be the case: perhaps outport people were the victims of an evil and misguided state. Only further research will help to understand all the dimensions of resettlement, but the most recent historian to turn to the subject has concluded that when an activist state intervenes in people’s lives — as it did during the period of resettlement — the consequences are “oſten tragic.”9

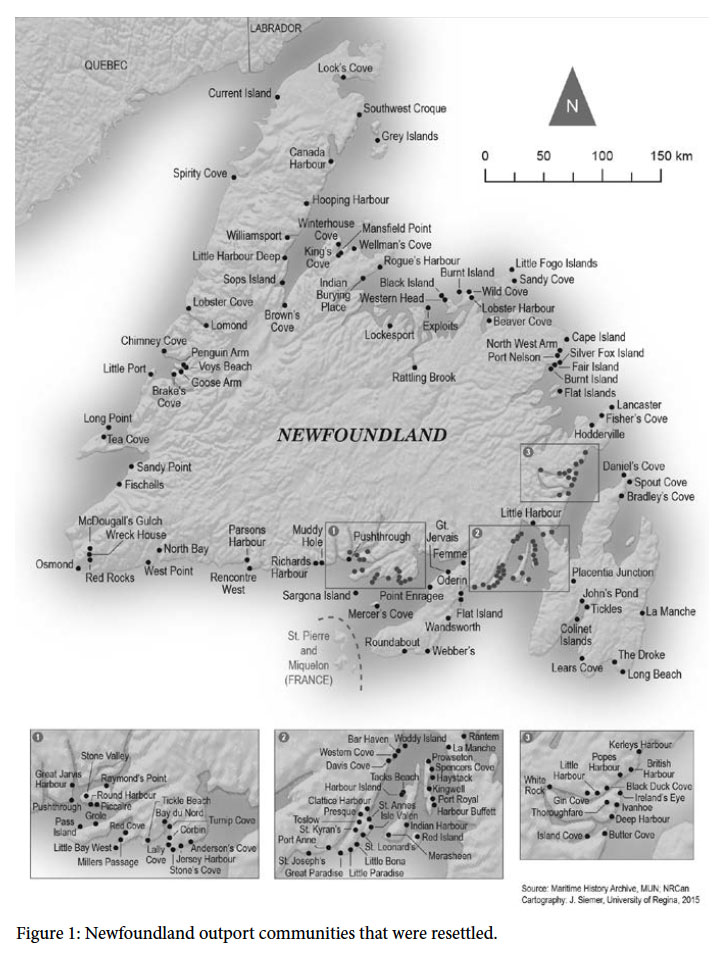

4 This article investigates the resettlement of Pushthrough, the author’s place of birth and early childhood. It was a small fishing village on Newfoundland’s southwest coast about 20 kilometres northwest of Hermitage (see Figure 1). Pushthrough was comprised of three sections: Dawson’s Point, which was separated from the main area of settlement by the Pushthrough Gut (a narrow channel of water), Pushthrough proper, and the Bottom, a small harbour to the west of the Gut. It is said Newman and Company, the famous Dartmouth merchants who plied a trade in salt fish and Portuguese port, founded their first summer seasonal migratory fishing base, or plantation, in Newfoundland at Pushthrough in 1672. The first permanent settlers date from around 1812, when George Chambers moved there from Gaultois to establish a fishing room and later mercantile premises. By the first Newfoundland Census in 1836, 12 families called Pushthrough home, and the population — principally English from Dorsetshire and Somerset and almost all Anglican — had grown to 86. In 1872, an 86-foot bridge was constructed over the Gut to link Dawson’s Point to the main settlement, and by 1884, when the population reached 209, the community enjoyed an Anglican church and school, and had become a major service community for outlying harbours. By then, four small trading firms were engaged in trading furs, the lobster fishery, the bank fishery, and the coastal trade, but in the first two decades of the twentieth century, most of the local firms scaled back operations and eventually went out of business. By 1945, the population had declined to 175 but the arrival of families from the smaller, nearby fishing communities pushed it to 247 in 1961. A gradual decline began thereaſter as young families relocated, first to work in the Gaultois fish-processing plant and later to Head of Bay d’Espoir and Milltown for employment on a major hydroelectric project. By 1966, the population had shrunk to 204, and the three-room school was reduced to two because of the inability to attract qualified teachers. The quality of education that children were receiving became an important consideration in the decision to resettle the community a short time later. Most of the men in Pushthrough had earlier engaged in either the inshore fishery or the bank fishery, but by the 1950s and 1960s they had migrated to the offshore trawler fleet operating out of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia ports. Those who worked in the Nova Scotia deepsea fishery normally leſt Pushthrough shortly aſter Christmas each year and returned only in late fall. With the men away, women ran the households, dependent on the money sent by their husbands via postal telegrams aſter each voyage. At the time of resettlement, 35 residents were listed as dragger fishermen (mostly in Nova Scotia), 10 as general labourers, and six as carpenters; virtually all were employed outside the community.10 Between 1966 and 1968, 17 of 50 households leſt the community. Most of those who leſt were young families with children.

5 Pushthrough was just one of hundreds of small and isolated communities in the province that lacked basic public services and social amenities taken for granted in most places in Newfoundland and across Canada by the 1960s. Some households had installed generators by the late 1960s for lighting in the evening but the community was without electricity during daylight hours. No one in the community had running water and families had to bring four or five three-gallon aluminum buckets of water each day from a community well, and more on washdays. The well was oſten a quarter of a kilometre or more from the homes and the buckets were filled twice daily, necessitating a kilometre walk each day for water. Lack of electricity added immensely to the burden of work, especially for mothers; without electricity, water had to be heated on the stove in the hot days of summer as well as during the winter. Baking bread was also a demanding endeavour; winter or summer, the wood stove had to be fired up to bake bread and to cook each meal. In Pushthrough, men and young boys went in dories to cut the wood for the stoves and the wood box had to be replenished each day, a chore for children. There were no electric irons, no vacuum cleaners, and no dishwashers to free women and their older daughters from the drudgery of housework. Washday, usually on Monday, was perhaps most onerous, and it lasted the whole day. Some families had gas washers with a wringer, but the washboard (or scrubbing board) and cans of lye were still common when the community relocated in 1969. The kerosene lamp was ubiquitous, and without running water there were no indoor flush toilets. A bucket served that purpose and it had to be emptied daily. The doctor, stationed in Hermitage, visited Pushthrough every second week to hold clinic aboard the “doctor’s boat,” the Sir Richard Squires, which was ironic given that Squires as Prime Minister was the great harbinger of Newfoundland modernity in the 1920s. By the mid-1960s, residents were becoming acutely aware of the lack of social amenities and public services that came as a result of their isolation, and they oſten petitioned government for better living conditions.

PURPOSE OF ARTICLE

6 This article has several purposes. The first is to emphasize the importance of resettlement in the history of Newfoundland and Labrador and encourage further study at the state, community, and individual levels. The second objective is to bring to scholarly attention the data gathered by public officials and now available at The Rooms Provincial Archives in St. John’s and at Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa on hundreds of Newfoundland communities and the thousands of outport families during the era of resettlement, and thereby to encourage researchers to make more use of these valuable resources to investigate the social, cultural, and economic history of twentieth-century Newfoundland and Labrador. Those records, collected by various government departments, but notably the Department of Community and Social Development, Resettlement Division, the Department of Public Welfare, and the Department of Rural Development in Newfoundland, as well as several federal departments, principally, Fisheries, Regional Economic Expansion, and Manpower and Immigration, may be the most complete records of rural and outport Newfoundland ever assembled. At the micro level, these records show how each community was structured. The Resettlement Division collected and preserved records for each household in all the resettled communities. My third purpose is to encourage further investigation into individual resettled communities to understand how the process functioned at the community and familial level. Fourth, we need to better understand the world of resettled families and consider strategies that resettled peoples adopted as they transitioned into their new communities and how they were accommodated (or were not accommodated) by receiving communities. And, finally, delving into the resettlement files may be an effective way to understand social and economic change in rapidly developing modern societies, as Newfoundland was aſter union with Canada in 1949.11

GOVERNMENT RESETTLEMENT DOCUMENTS

7 This article is based largely on files from the Resettlement Division in GN 39/1, the Department of Rural Development Fonds, at The Rooms Provincial Archives. These records provide some of the best materials now available on the lives of many communities in rural Newfoundland in the post-Confederation period. The files, detailed and reasonably complete, contain the initial letters from community members who approached the government investigating the possibility of state support for their individual relocation or that of their communities. Each file contains an application to resettle from each household and includes all correspondence between state and household until a Release of Mortgage on an applicant’s property was granted, giving households title to their new homes. The records normally cover a period of between five to seven years although some files cover more than a decade, especially when households were resettled more than once or encountered an issue that took time to resolve. The personal information in the 24 metres of resettlement files at The Rooms is protected by the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act, 2002, which prevents the sharing of private information without the permission of those individuals mentioned, but the records are available to researchers. I was permitted access, but no private information about the people who moved from Pushthrough, except for that concerning my own family, is included here. What follows is based primarily on the files in GN 39 for Pushthrough; records that survived my family’s resettlement and are in my possession; and interviews with several people who resettled from Pushthrough.

THE RESETTLEMENT PROGRAMS, 1954–1975: A BRIEF OVERVIEW

8 Although the Commission of Government had sponsored a land-settlement program in the 1930s aimed at relocating unemployed and underemployed families to unsettled areas where farming activities might add a component to their livelihood, it was largely unsuccessful. Eight land settlements were created but only 200 families were assisted in relocating. The first post-Confederation resettlement program undertaken by the provincial government in 1954 on its own, and known popularly as the Centralization Program, had at first a more general focus.12 The Centralization Program was initiated following requests to Premier Smallwood from families in several isolated outports for financial assistance to relocate to communities with better access to employment and services. Administered through the Department of Public Welfare, its aim was to centralize people in communities with better schools, medical facilities, and improved transportation, especially road networks. Initial grants were modest, at $150 per family, but increased incrementally to $600 by 1958. Payments were made only when all families in a community relocated. However, no restrictions were placed on where a family might resettle and, indeed, some families actually relocated to places with only marginally better public services than those where they had lived. From the outset, though, government insisted that it leſt to the people all decisions about vacating their communities because it did not want to be accused of coercing people to relocate from the smaller outports.

9 Despite pressure from Premier Smallwood, the federal government refused to become involved in the province’s first resettlement program. The federal cabinet feared that the whole issue of resettlement would be a sensitive one and decided to leave the matter to the province. Moreover, Ottawa believed that the program was outside its jurisdiction even though many federal bureaucrats believed that the exodus of fishers from the more remote communities was inevitable and desirable.13 By the mid- to late 1960s, the governments and bureaucracies in Ottawa and St. John’s were largely influenced by a group of politicians and technocrats who embraced the liberal notion that the state knew what was best for society and agreed to participate in Newfoundland’s resettlement program.14 Ottawa signed with Newfoundland in July 1965 a five-year, cost-shared federal–provincial agreement to support the removal of households from outlying settlements to more favoured communities within Newfoundland. It was renewed in 1970 for an additional five years. The program had two objectives: first, to “facilitate the transition of the human resources and movement of social capital from disadvantaged outlying communities to areas of greater opportunities for economic, social and cultural benefit”; and, second, to “rationalize and develop a viable and dynamic 20th century fisheries industry.”15

10 The Newfoundland Fisheries Household Resettlement Program, as it was officially called, provided a basic grant of $1,000 to each household and an additional grant of $200 for each member of household that moved from Pushthrough and other isolated communities. The basic grant included several allocations, including a cash payment of $400 and a fisheries readjustment grant of $200 from the federal government. It split equally with the provincial government a relocation grant of $400 to each household. The grant of $200 for each member of a resettled household was also divided evenly between the two orders of government. All expenses, supported by receipts, incurred in relocating the household were reimbursed by Ottawa, but the program did not provide for the cost of the movement or replacement of real or immovable property. Any property abandoned, including all physical structures, became the property of the Crown, except when fishers continued to use the premises for the purpose of carrying on their work. The Canada–Newfoundland Agreement also outlined the procedure for resettlement, and its various aspects are discussed below.

THE RESETTLEMENT OF PUSHTHROUGH

11 People abandon villages and outports they have lived in for generations for a variety of reasons, and resettlement had been common in Newfoundland. Scores, perhaps hundreds, of similarly situated places like Pushthrough had been abandoned through voluntary out-migration from the mid-nineteenth century up to the 1950s, when government assistance perhaps became a factor in speeding up the process of rural depopulation. Some of these migrations were related to changes in the fishery. The motorboat and cod trap are said to have encouraged some centralizing of population, as did the commercialization of species such as lobster. More commonly, out-migration was related to employment opportunities elsewhere, and while Pushthrough had benefited from such developments earlier, by the 1960s it had lost the prominence that it once had as a new set of conditions and specific dynamics, factors, and influences converged to lead to its abandonment. Pushthrough merchants had long quit the bank fishery and many of the 35 residents who laboured in the offshore dragger fleet in 1969 sought employment that offered a steady, predictable income and allowed them to spend more time at home with their families. That employment could not be found in Pushthrough. Similarly, general labourers and carpenters only infrequently found employment there and they were part of a migratory group in constant search for work. Most males were employed outside of the community and were oſten away for months at a time. As was noted above, 17 families moved from Pushthrough for employment opportunities elsewhere between 1966 and 1969; initially, these migrations were at their own expense, but each family was later approved for relocation and received the relocation allowance. One of those families had eight school-aged children, and the general decline in school enrolment, together with the difficulty of attracting qualified teachers, became an important impetus to resettlement as families moved for better educational opportunities. Values and expectations, especially regarding education, were changing in Pushthrough.

12 Throughout 1967 and 1968 several Pushthrough residents wrote to Premier Smallwood and Don Jamieson, the federal Member of Parliament for Burin-Burgeo, requesting information about relocating. Jamieson indicated that “the tone of their letters suggests that most of the people of Pushthrough recognize the need to resettle,” and suggested that a government official visit the community.16 The regional director of resettlement had indeed gone to Pushthrough in September 1967, a month before Jamieson’s letter. Although a number of residents had contacted St. John’s about resettlement, the regional director came to Pushthrough to discuss with Reverend Reuben Hatcher, the Anglican priest, the resettlement of the smaller and more isolated communities in his parish. Pushthrough had once been the headquarters of an extensive parish with several dozen small isolated communities, but by the mid-1960s the Parish of Pushthrough was reduced to only a half-dozen locales as the rest had been depopulated and abandoned through out-migration. Pushthrough, however, was not yet on any resettlement agenda as government had recently approved it as a reception community for several families from Great Jarvis Harbour, a community of just two families a kilometre away. Even so, note was taken that Bay d’Espoir, just 30 kilometres away, was becoming increasingly attractive because a major hydroelectric project there was nearing completion, and if prospects of a new pulp and paper mill in that community were realized “Pushthrough would phase out slowly within the next few years.”17 For most men, the attraction of wage labour and year-round employment while living at home was irresistible. Although some residents requested a resettlement petition form, which according to government rules needed to be signed by 80 per cent of the householders before action could be taken, it was not circulated until further discussion occurred.18

13 Letters from Pushthrough trickled into St. John’s throughout early 1968, describing the difficulties facing the community, notably the problem of recruiting qualified teachers and seeking information about resettlement. Some residents had also contacted Abel Charles Wornell, their Member of the House of Assembly, advising of their wish to be relocated elsewhere.19

14 Resettlement was first discussed officially and publicly in Pushthrough in April 1969, by which time the 50 households in 1966 had dropped by 17. Although the resettlement regulations had been changed in August 1966 to extend the program to individual householders who moved to designated fisheries growth centres where employment opportunities were available, most of the families that moved before 1969 were not certain they would qualify for assistance. However, it is logical to assume they understood that they would qualify for all available financial assistance as regulations permitted householders to claim financial aid if they relocated not more than 18 months before a petition was received from the evacuating community.20 The sudden and precipitous loss of these families had a major impact on the thinking of those remaining concerning the viability of Pushthrough as a place to live and raise families. The inadequacy of the community to meet rising expectations clearly was becoming apparent to everyone, and given the rugged terrain and limited population, a road to the rest of the province was improbable.

A PUBLIC MEETING AND A PETITION

15 A public meeting was called on 7 April 1969 to discuss relocation. Fiſteen householders attended. A Pushthrough Resettlement Committee was formed. The three-person committee represented the three distinct “sections” of the community: the Bottom, Pushthrough proper, and Dawson’s Point. The meeting passed two resolutions. The first empowered the committee to circulate a petition, certify its authenticity, and submit it to the Department of Community and Social Development. The second authorized the committee to negotiate with the Director of Fisheries Household Resettlement on all issues on behalf of the community. The three members then signed a statement testifying that all information pertaining to the resettlement program had been presented and discussed.

16 The purpose of the community petition, dated 25 April 1969, was clear. It states: “We, the householders of Pushthrough, an isolated community, hereby indicate our desire to move and Petition for assistance under the Fisheries Household Resettlement Act.” Householders were asked their intentions about resettlement and, affixing their signatures, indicated their plan to request financial assistance through the Fisheries Household Resettlement Act to cover the cost of relocation. Once the request for relocation had been approved, each household had to complete an application for assistance. Several people were asked to visit, or canvas, each home in the community with the petition.21 Of the 50 householders “officially” listed as residents, a notation on the petition indicated that 17 had “already gone” by the time the petition was circulated. Another note indicated that one householder was on a herring seiner out of Shelburne, Nova Scotia. Thirty-two signed the petition indicating their intent in relocating. Once the petition had circulated throughout the community, William Simms, chair of the committee, dispatched it to St. John’s. The Pushthrough resettlement files at The Rooms also contain the names and information on each of the 17 households and the 65 persons who leſt prior to the meeting of 25 April 1969; their departure sealed the community’s fate.

17 The age and signature of each head of householder who signed the petition are revealing. Data on the Pushthrough resettlement petition show that householders signing averaged 58 years and ranged in age between 34 and 84. Four marked an X, indicating illiteracy — at least an inability to write their names. Each signatory to the petition included a proposed place of resettlement and the anticipated departure date. Chosen as destinations were: Milltown, St. Alban’s, and other communities in Bay d’Espoir, where a 130-kilometre gravel road connecting to the Trans-Canada Highway had recently been completed; Hermitage, population 400 in 1966, with a multi-room school and a doctor, and persistent rumours of a fish-processing plant about to be built there; the deep-sea fishing ports of Gaultois, Fortune, Port aux Basques, Burgeo, and Grand Bank; the pulp and paper town of Grand Falls; and the capital city, St. John’s. Five householders indicated uncertainty of destination.

NOTIFICATION OF INTENT TO RELOCATE/REQUEST FOR EMPLOYMENT FORMS

18 Each householder who signed the resettlement petition was also required later to complete a document or form called the Notification of Intent to Relocate/ Request for Employment.22 It was on the basis of information from the petition and the document of Notification of Intent as well as reports from the local Pushthrough Resettlement Committee and a Rural Development officer who had to visit the town that the Resettlement Committee of the province assessed the merits of each application and made a recommendation on the request to resettle. The provincial committee could approve the request to resettle, but then refuse to approve the householder’s choice of destination. Most householders completed their Notification of Intent between early April and late July 1969. Although only a single page, the application form contains enough information to construct a fairly detailed demographic profile of communities such as Pushthrough at the time of relocation. The Notification of Intent was divided into several sections. The first asked for basic householder information: name, age, marital status, occupation, expected occupation aſter move, and social insurance number. Only those employed outside the home had a number; none of the women did. The second section listed all members of the household. Each head of family registered the name and age of each member, stating relationship to householder, identifying those who were in school both before and aſter the move, recording the grade level of each, and providing the type of work each member of the household was engaged in if not in school and the type of work to be engaged in aſter relocation. All trades and skills had to be enumerated, and members of household who were eligible for assistance or training under the Canada Manpower Mobility Program had to be identified. Some who resettled received additional grants under this program.

19 The third section asked a number of questions about the impending relocation. The first asked if the householder’s name appeared on the original petition for assistance under the Fisheries Household Resettlement Program. The second asked if the householder was applying to move to an approved growth centre or if applying to move as a widow(er), incapacitated, or elderly. In the first year of the federal–provincial agreement, only 25 per cent of those householders that resettled went to growth centres (the stated government preference) while 60 per cent resettled to other substantial communities; 15 per cent chose communities only marginally more populated than Pushthrough but that had better amenities, had potential for development, and provided some better prospects for employment. The choice of location was largely leſt to each householder. The resettlement program aſter 1966 allowed householders who were widows, handicapped, or elderly to relocate from isolated communities and to apply in an individual capacity, in the same manner as individual applicants wishing to resettle to the growth centres. The fourth section posed four questions. Where were they moving? Would the householder be moving his/her present house, building, buying, or renting? What travel and moving costs were needed? And, finally, was the applicant applying for either the $3,000 or $1,000 mortgage as supplementary assistance towards the cost of a building lot? It should be noted that by 1969, resettling householders were offered supplementary assistance of up to $3,000 to purchase serviced lots in developed townsites or $1,000 for unserviced lots in other reception centres. The amount requested usually varied depending on installation costs for various services, notably water and sewages services. Naturally, those relocating observed carefully what other householders received and frequently demanded an adjustment if those in similar situations received larger sums. As a result, many asked for a re-evaluation and adjustments to their claims. In one instance, a householder who relocated to Milltown discovered that those who had moved to Hermitage received the full $1,000 in supplementary assistance but because he had paid only $400 dollars for water and sewage servicing and $150 for the cost of the land purchase, he was reimbursed only for that amount. He had installed running water and a flush toilet but could not afford a full bath or hot water at the time. He demanded equitable treatment so, he, too, could enjoy some of the modern conveniences: on 7 January 1971, almost two years aſter leaving Pushthrough, he wrote the Director of the Resettlement Program: “I am asking for the [additional] four hundred and fiſty dollars [that] is due to me so we can put in our bathroom set . . . and our hot water.” His letter went unanswered for months, and on 19 August he wrote again: “the other people that moved to other places got the money and I was promised it when I leſt Pushthrough.” In October 1971, he received a visit from the Regional Director of Field Services, and a short time later the full amount was paid and a hot-water boiler and bathtub were installed.23

20 Not all requests for redress ended well, however. One case lasted until 1976 and the delay leſt the applicant frustrated and angry. He had relocated to Morrisville as a pensioner but when he submitted expenses for the supplementary land assistance on 17 August 1970, his request was denied. Morrisville was not an approved reception centre, and although the provincial resettlement committee had given special permission (as it normally did) for the move, such persons did not normally qualify for the supplementary assistance. In fact, under the rule, about two-thirds of the Pushthrough resettling householders failed to meet this requirement, but this particular applicant was persistent and refused to accept the ruling of the Department of Community and Social Development. In a letter to the Director of Resettlement, he wrote: “I understood the reason all of us leſt the settlement of Pushthrough were for various reasons as no electricity, running water or sewage, suitable teachers for our schools and also poor medical attention.” He reminded the Director that other communities such as Hermitage had not been on the approved list but those who relocated there were able to avail of the full range of assistance. The applicant pointed out in a letter dated 10 July 1971 that a widow who resettled received a supplementary grant, and he warned that he would persist until his claim was accepted.24 The applicant sought the intervention and support of his MP, Don Jamieson, and south coast MHAs, who all asked the provincial government to reconsider its decision, as did the Regional Director of Field Services of the Department of Community and Social Development. Even the applicant’s threat of legal action against the department and its minister, William Rowe, did not produce the results desired. In a final letter dated 4 February 1976 the Director, clearly exasperated, wrote: “We are sorry but there is no way under the Federal/Provincial Agreement that assistance can be provided.”25

21 Many who resettled were desperate for the supplementary assistance because re-establishing themselves in new communities was costly and few had savings to call upon to provide their basic household services. With serviced lots averaging between $3,500 and $4,000 and construction costs for a home an estimated $12,000, the cost of housing was enormous, especially with annual family incomes averaging around $3,600, families struggled to cope with the cost of housing in reception areas. A householder who received $1,600 in resettlement grants and a supplementary assistance of $1,000 later wrote government saying: “you can’t do much with building a home for that much money.” This individual had expended his basic grant to erect the exterior shell of his house and had completed only the kitchen and one bedroom. The rest of the house could only be completed “as finances become available,” he added.26 Such stories question any notions that people resettled as part of a “money grab” from the state.

22 The final section of the Notification of Intent posed questions about the household’s personal history, including: grade level of education (generally very low); training completed; licences or certificates held; qualifications for machine and equipment operations; and disabilities.

DELAY IN APPROVING THE PUSHTHROUGH PETITION

23 Shortly aſter Pushthrough residents petitioned to resettle and completed their Notification of Intent, they received a personalized form letter from the government acknowledging receipt of their request. They were advised that a fieldworker from the Department of Community and Social Development would soon visit the community, and following his report the Household Resettlement Committee would meet and make known its decision to applicants at the earliest possible date. When the committee in St. John’s began its initial review of the Pushthrough case, however, it discovered that some applicants proposed moving to Milltown, a community that the committee, based on information from Crown Lands, believed did not have suitable land to accommodate them. Others indicated that they wanted to move to Hermitage, which was not then on the list of approved reception centres. Word of the delay caused considerable anxiety in Pushthrough as the decision to move had been firmly taken and there was no retreating from it. Residents were concerned with what might happen to them.

24 As it turned out, the town council of Milltown, Bay d’Espoir, had been trying to acquire government-owned land for a new subdivision to accommodate families resettling from Pushthrough and other communities and had identified land approved by several government departments but rejected by Crown Lands. The problem was brought to the attention of the MHA representing both Pushthrough and Milltown, and was quickly resolved in favour of the applicants. The issue of Hermitage not being a recognized community for receiving resettled families was brought into focus by a letter 28 April 1969 from Minister Rowe to a resettlement applicant, a prominent shipowner involved in the coastal trade who had selected Hermitage as his preferred destination. The minister recommended Harbour Breton, Gaultois, or St. Alban’s as acceptable alternatives, but his advice and decision were evidently not much appreciated. In typical outport fashion, where government was a distant entity and there was much reliance on more literate residents — merchants, teachers, and, especially, clergy — in dealing with the state, this particular applicant followed the usual route and turned to the Anglican priest as his advocate.27

25 The result was a stinging, abrasive, and censorious letter from the Anglican priest to Rowe. It began with an assessment of the neighbouring towns recommended as reception communities: “I can probably understand moving to Hr. Breton; Gaultois appears to be saturated already and continues to be isolated; St. Alban’s, as far as I can learn is mainly a welfare community and certainly offers no employment and at St. Alban’s, as well as other parts of Bay d’Espoir, land is frozen and no one can get permission to build a house there.” He continued: “Rejection of [name removed] application to move to Hermitage confirms my belief that this total resettlement program is being done blindly.” He reminded the minister that he had written an earlier letter to Premier Smallwood complaining about the lack of availability of land in Bay d’Espoir and about other aspects of the resettlement program but it had not even been acknowledged. Then, he turned to the point at hand and made a case for Hermitage as a receiving settlement: “I understand locally that people are being encouraged to move to Hermitage and that land is being prepared there for new building lots. Hermitage shows as much growth as any other centre in this part of the South Coast,” he wrote, adding that many of the people from the resettled communities of Richard’s Harbour and Muddy Hole had moved to Hermitage, as had a number of families from Piccaire. While maintaining that he was not disagreeing with centralization and the program of resettlement, he condemned the process: “It is now late in the game as far as the resettlement of Pushthrough and some other places are concerned,” he wrote. “In many cases people are moving, ignorant of the scheme and knowing only some of the answers.”28

INVESTIGATION INTO PUSHTHROUGH RESETTLEMENT PLANS

26 In mid-June 1969 the fieldworker, who was already familiar with Pushthrough, began investigating the problems delaying the approval of the Pushthrough petition. On Tuesday, 10 June, he met with the Milltown town council and was assured suitable building lots would be available by the time families arrived. He also examined and approved two sites in nearby Morrisville that Pushthrough householders had already acquired. At St. Alban’s he was likewise assured by the mayor and town clerk that plenty of suitable building lots were available. The fieldworker then travelled to Pushthrough by CNR coastal boat. As he reported to the Director of the Fisheries Household Resettlement Program, Mr. K. Harnum: “I worked until twelve midnight interviewing people at Mr. Wm [William] Simms’ house. I also did Field Workers reports on all householders that are now living at Pushthrough. I find that one hundred percent of the people are planning to move not later than November 1, 1969. All the people are dismantling their houses and are moving to reception centres.” He noted that people were moving to Hermitage, Milltown (10 or 11 families), Port aux Basques, St. Alban’s, Morrisville, Fortune, St. John’s, Grand Falls, Harbour Breton, and Burgeo. Aſter completing his work, he hired a private boat to take him to Hermitage. At Hermitage, the fieldworker met Mayor Everett Rose and talked by telephone to Reverend Canon Watkins, who was in Stone Valley (it had only one phone), an island community approximately six kilometres away that also resettled a year later. They discussed the availability of building sites, noting that the community council had 12 building lots available with room for more. The fieldworker recommended that Hermitage be accepted as a reception centre (as it subsequently was), adding that it was a “viable community,” with good schools, a doctor, and “a progressive town council.” It had a year-round fishery and daily collection from the fish plant at Gaultois. He filed his report with the government on 20 June 1969.

27 As noted, the fieldworker completed the mandatory report for each household while in Pushthrough. These documents are another source of valuable information. Each asks the reason for resettlement. In addition to listing members of the family and the age of each, it provides additional data on household family structures and personal characteristics. An applicant, for example, had to identify extended family members, and those with any disability or who were in any way incapacitated. There were also questions about housing ownership and tenure, both in relation to Pushthrough and in the new location.

RESETTLEMENT OF PUSHTHROUGH APPROVED

28 At a meeting on 10 June 1969, the provincial Household Resettlement Committee tentatively approved the relocation of Pushthrough pending satisfactory resolution of issues regarding Milltown and Hermitage as reception centres. Meeting minutes noted that 100 per cent of households had petitioned and that 17 families had already moved.29 Aſter reviewing the fieldworker’s report and materials from applicants, Mr. Harnum informed William Simms, the chair of the Pushthrough Resettlement Committee, by letter that the Pushthrough petition had been approved. A telegram was sent two days later to the Reverend William Noel, advising him that the letters of approval for the householders of Pushthrough were in the mail. Earlier, between 23 January and 1 May 1969, the provincial committee had considered 14 applications for resettlement from Pushthrough, approving 12 and deferring two, pending arrangements for building lots in the Milltown area. All householders approved for relocation during that period were employed either in the fish-processing plants in Burgeo, Gaultois, and Fortune or as carpenters in Milltown.30 With the approval of all remaining applicants, the resettlement of the whole community could now proceed. Applications for the Resettlement Assistance Claim accompanied the approval letters. These were to be returned, together with receipts for travel and removal expenses, aſter the move had been completed.

LEAVING PUSHTHROUGH: A PERSONAL NOTE

29 My family leſt Pushthrough for our new home in Hermitage on Monday, 7 July 1969. Our next-door neighbours and friends, the Rowsells, went to Fortune less than four weeks later. Grandmother Garland joined us in Hermitage at the end of August; Grandmother Blake relocated to St. Alban’s on 4 September 1969. By the end of that month every family had leſt. Kinfolk and friends who had lived together for much of their lives were separated forever. I am never sure what I actually remember of the day of our departure from Pushthrough. Resettlement was a subject that was rarely discussed in our home, and I can never be certain now if what I remember are my recollections or if I have somehow internalized what I did hear and have made them my own memories. I recall, however, a sense of anxiety in the few days before the move when everything was readied for the journey across the bay, and I remember an Evening Song service in the Anglican church the day before leaving. I remember the arrival of Mr. Riggs’s schooner from nearby McCallum (which was also isolated and continues to debate resettlement), as well as the loading of our belongings and my mother’s tears. We loaded coal aboard the schooner even though in our Hermitage home we had an electric and oil stove and no longer any use for this fuel. We took the white enamel pail that we had at the top of the stairs and used for years as a toilet, but it was relegated to the storage room in the Hermitage house, where we had a flush toilet and running water and even a bathtub. What I remember most about moving into our new home was the separate bathroom and the switches that could turn on the lights any time of day or night.

30 My mother, who was a widow by then, completed her application for assistance under the resettlement program 10 days aſter we arrived in Hermitage. In it, she recorded household members — herself and six family members (myself and her five other children) — and the important part called the “Declaration.” My mother had to declare that she was the head of household of the dwelling in Pushthrough and that the “dwelling and lands are now vacated and it is understood that they may not be occupied again without the written approval of the Minister of Community and Social Development.” The form also contained the standard references to the veracity of the information provided. She signed the application in the presence of Canon Watkins. Her application was processed rather quickly, and a cheque was issued on 31 July 1969. We still have the Remittance Voucher, No. 323433, marked “RESETTLEMENT ASSISTANCE IN MOVING FROM PUSHTHROUGH TO HERMITAGE.” The Department of Community and Social Development arrived at the amount under the following formula: the Basic Resettlement Grant (provided by the government of Canada), $400; the Fisheries Resettlement Adjustment Grant, $200, paid for by the government of Canada; a Relocation Grant of $400, split evenly between the government of Canada and the Newfoundland government; and the Household Members Grant of $200 per household member, with $100 paid by each government. She also received $28 for travel expenses, which presumably was the amount for passage on the schooner ($4 each for seven people). The $250 for transporting our household goods from Pushthrough to Hermitage was paid directly to the carrier by the Department of Community and Social Development. The cheque for $2,428 was more money than my mother would have ever seen at one time. It was used to make a payment on the house we had purchased for $5,000 in Hermitage. Still, she owed $2,500 and did not have any savings to cover the balance owing. Her monthly income of $220 from Worker’s Compensation she received aſter the death of our father leſt little aſter household and other expenses with which to clear her debt. Although our father had paid Canada Pension premiums, the Plan rejected her claim for benefits because he had been killed in a construction accident before contributing the minimum necessary to collect. When my grandmother closed her home in Pushthrough and relocated to live with us, her benefits of $1,215.87 also went towards a payment on the house.

31 Although resettled families were eligible for the Land Supplement Assistance — or what was referred to as “mortgage payment” — it took more than a year for my mother’s benefit of $1,000 to arrive. There were no problems with the dwelling house as it had been renovated just a few years earlier, but there were questions about land tenure. The question of landownership has been traditionally a constant source of acrimony and bitterness in rural Newfoundland, where landownership is oſten based on flimsy claims. During the resettlement period several prominent residents of a number of reception centres claimed ownership over considerable parcels of land on the assertion, for example, that their livestock once grazed on a particular site or they stored firewood there. Landownership is a subject that, if investigated, would reveal much about life in rural Newfoundland and also tell us something about how resettled people were treated upon their arrival in their new communities.

32 Fortunately, the family from whom my mother had purchased the house had secured title to their land in 1967 aſter several years of renting it from a local entrepreneur, who claimed a considerable amount of land in Hermitage. My mother bought the land on which the house sits on 16 April 1970 (though the amount was included in the price of the house). Because the Indenture was signed by a Commissioner of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia where the original sellers then lived, it was deemed inadmissible by the Registrar of Deeds in Newfoundland and the proper signature of a notary public in Nova Scotia was required. The Rural Development Officer responsible for the file estimated the cost of land and services to be over a $1,000 and recommended that amount be paid. Once the proper titles were received, the Department of Community and Social Services issued her a cheque for $1,000 on 16 October 1970, 75 per cent provided by the federal government and 25 per cent by the government of Newfoundland. That cheque was also used as a payment on the house.

33 There have been many reports in some receiving communities of attempts by neighbours to exact payments from resettled householders — oſten of $1,000, the amount that many resettled families received to deal with land issues — for existing water and sewage connections. Because there were no municipal water and sewage networks in most outports, several homeowners co-operated to install running water and sewages lines to the ocean. In some instances when a house was purchased by a resettled family, the residents who had initially installed the water and sewages lines demanded payment for the newcomer’s share of the installation even though the original owner of the house would have paid his share when the lines were installed. Clearly, this was an attempt to take advantage of resettled families, and such actions oſten resulted in bitter disputes between long-time residents and newcomers. It was just one incident that resettled families had to deal with in their new communities. Another was the bullying and treatment of children who arrived from resettled communities. In many cases, resettled people were long considered outsiders to the community pretty much in the same way that immigrants or refugees have been regarded elsewhere in Canada.

34 When resettled householders accepted a Supplementary Land Assistance, the government of Newfoundland took an interest-free mortgage on the property (house and land) of that amount. The mortgage was reduced at a rate of 20 per cent annually for each full year of occupancy for a five-year period. As my mother had been in the house for a year prior to receiving the grant, her mortgage term was reduced by a year. If she had vacated the home at any time within the five years, then she would have had to repay to the government the value of the mortgage, less 20 per cent for each full year of occupancy. Each year, she had to apply for the Annual Write-off of Mortgage, and on 23 October 1974 the house in Hermitage was finally hers. By that time, she had already repaid the debt for the house with the help of her sons who were deep-sea fishing in Nova Scotia.

35 Pushthrough ceased to exist as a community in 1969. My mother was rather stoic about it all and said very little about resettlement aſter we leſt. At times, however, when some of her friends would lament the resettlement of Pushthrough, she would respond with something like, “what would we do up there now with no school or doctor and storm-bound for days even as someone lay dying for lack of medical care.” I recall vividly her delight in having a larger school with qualified teachers and access to better medical facilities, even if it was just a lone doctor at the community health clinic. Modern domestic conveniences at Hermitage surely made her life much easier than in Pushthrough. Some of the differences included: running water instead of buckets in the porch filled daily from the community well; electric lights replacing oil lamps; indoor flush toilet rather than a white enamel pail at the top of the stairs that had to be taken and emptied into the ocean every day (preferably at high tide); and a hot-water tank rather than a large cast-iron boiler simmering all day on the wood-burning stove. Surely, these modern “conveniences” made her life much easier. My grandmother, who lived with us aſter she leſt Pushthrough, never adjusted well to life in Hermitage, even though she had moved several times earlier in her life, including from Saddle Island — a bleak, desolate island a kilometre west of Pushthrough — aſter a tsunami in 1929 destroyed their fishing premises. Resettlement was generally not kind to the elderly but many of them encouraged their sons and daughter to move, nonetheless. A friend who moved from Pushthrough with his family to Milltown in 1968 remembers a conversation between his 85-year-old grandfather and his father, when the former said, “Freeman, my son, you have four young sons, there is nothing here for them, they need to get their education.”31 My mother oſten gave the same reason for resettling. She and many others believed that the future lay in education and she understood that was not possible in Pushthrough. The future also lay in the larger communities that were or could be linked to the provincial road system (and physical topographical difficulties and cost made that unlikely for Pushthrough). The loss of 17 families between 1966 and 1969 had been a major blow to the demographic sustainability of the school and the community.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

36 Many critics of resettlement never lived in any of the isolated communities like Pushthrough when decisions were taken to relocate, and thus they could not fully appreciate the circumstance of those involved. Those born in isolated outport communities who leſt to live and work in St. John’s and other urban centres, with never a thought of returning except for a short visit or a summer holiday, were oſten most critical of the people who moved during the resettlement program. Pushthrough was in difficulty long before 1969, and like many resettled communities it faced widespread illiteracy, a lack of economic opportunities, and in the absence of modern amenities, the sheer drudgery of everyday work, especially for women and mothers, and that was becoming increasingly unacceptable. It has also been argued — oſten without detailed evidence — that many people vacated their communities to join the ranks of the unemployed in new communities. This is only one of many assertions that need further inquiry. An investigation by the Department of Social Services and Rehabilitation in February and March 1970 found that 11.7 per cent of householders were in receipt of social assistance the month before relocating, but only 6.9 per cent at the time of the survey.32 There are also suggestions that households moved to take advantage of the financial incentives offered by the state, but as suggested here, those financial rewards were limited and rarely enough to re-establish a home in a new community. Even if residents moved willingly, some critics of resettlement have maintained, they were not aware that they were being manipulated through various financial incentives to relocate. Residents in the resettled communities were no fools and they normally made their own choices about where to live.

37 Yet, resettlement involved the uprooting and dismemberment of the social, cultural, moral, and economic webs of life built up over generations. Communities like Pushthrough had a wealth of oral knowledge accumulated over time through the exploitation of local resources, notably the fishery, and had developed a complex web of kinship and friendship that sustained it. There can be no denying that relocation involved a massive loss of that culture, and those traditions were lost without time for grieving — or, perhaps, fully understanding — as citizens rushed to meet the bureaucratic and financial hurdles that came with resettlement. Citizens obviously looked to the future without, at the moment, thinking much about what was lost. It is clear, too, that government officials simply did not anticipate a host of political, logistic, and administrative problems that might arise from resettlement. The idea was simple: move people away from living in a place with insufficient amenities and employment opportunities to places with more amenities and more jobs. While the intentions were noble, perhaps more consideration should have been given to how all this related to employment, kinship ties, land use, availability of housing, differing responses from community members, receptiveness of receiving communities, existing social supports, large-scale financial incapacity to absorb cost shocks in housing, for instance, and the widely varying capacities to adapt. There was a sense of a comprehensive plan but that was just an illusion. As is common with policy-makers and governments, those who led the resettlement agenda lacked capacity to anticipate consequences and sometimes inflicted more harms on individuals subject to their schemes than was ever imagined or certainly intentioned. Yet, there was a relatively mild response to administrative difficulties that the resettled people of Pushthrough (and elsewhere) experienced because the administration of the program was so personal, so face-to-face, a feature of public administration that is now gone.

38 Resettlement was not necessarily detrimental to those involved, however. Those who leſt their communities oſten brought renewal and dynamism to many towns throughout Newfoundland. Resettlement, then, is about both displacement and renewal as resettled people like those from Pushthrough confronted their challenges and adopted sustainable and successful rehabilitation strategies in their new communities. Most recipient communities oſten experienced a new dynamism and growth and enjoyed greater prosperity and diversity with the arrival of the newcomers from resettled communities such as Pushthrough.33 Consider Milltown, for instance. It had a population of 560 according to the census report from 1966; one can only imagine the impact that the arrival of 14 families and 51 people from Pushthrough alone had on the community, in addition to others who arrived from other outlying communities. Hermitage, Fortune, and Harbour Breton are also examples of towns that grew rapidly and gained more energy and viability because of resettlement. Many of the newcomers went on to play prominent roles in their new communities, but the receiving communities were quite conscious that there were “newcomers” among them.

39 A number of issues related to resettlement have been identified here, and more scholarly research should be pursued on the various aspects of the program in Smallwood’s Newfoundland and Labrador. A brief overview of the experience of the resettlement of Pushthrough in 1969 shows that the archival materials for more detailed investigation into individual communities is now available, particularly at The Rooms, for scholars and other serious researchers intent on studying resettlement, especially at the level of community and family. The massive collection of resettlement files also provides material for scholars interested in trying to understand the many facets of rural Newfoundland in the 1950 and 1960s, especially elements of social and economic transformation that were sweeping the province. For my family, resettlement worked because we were fleeing a difficult environment and my mother wanted a better life for her children. Although a single mom, she was practical, stoical, and resilient, qualities I suspect that were cultivated and admired in places such as Pushthrough and other outports that were places of frequent hard events. She, like many others, looked to the future and did not see it for her children in Pushthrough. Given the records that are now available at The Rooms and the Centre for Newfoundland Studies, we should begin a series of projects that will lead to a better understanding of resettlement, one of the truly momentous and seminal events in the long history of Newfoundland and Labrador.

The author wishes to thank Peter Neary, Melvin Baker, John Whyte, Stephen Whittle, and Reid Robinson, who offered comments on an earlier version of this paper.