Documents

Mining Prospects, c. 1668, at a Prehistoric Soapstone Quarry in Fleur de Lys, Newfoundland

INTRODUCTION

1 Historians and archaeologists like to complain that seventeenth-century Newfoundland is poorly documented. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that the documents of this period are not well known. In the course of research on the French migratory salt-cod fishery in northern Newfoundland, I have cranked my way through the relevant microfilms of France’s Archives de Colonies, a source equivalent to the Colonial Office (“CO”) series, familiar to students of British overseas interests. The early volumes of Archives de Colonies touching on Newfoundland are largely devoted to the administration of the French colony at Plaisance. But among these, I was happy to find a 1669 report on the fishing harbour of Fleur de Lys, on the Petit Nord, roughly the Atlantic coast of Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula.1 From the earliest days of the transatlantic fishery through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, this was an important fishing zone for crews from France, particularly Brittany, often shipping out of Saint-Malo.2 After 1713, the Petit Nord became the centre of gravity of the diplomatically defined French Shore in northern Newfoundland, where fishing crews had explicit permission to build seasonal shore stations, as they had done in previous centuries.3

2 The document of 1669 is signed simply “Denarp”; nor is it clear to whom the report is addressed, the writer simply beginning “À Monseigneur,” that is “My Lord,” a conventional greeting in addressing an administrative superior during this period. The use of the last name alone as a signature suggests that the writer was not without power himself — but the first real research question arising from this document is the identification of both Denarp and his correspondent. France, alas, is only now acquiring the kind of dictionary of national biography that Canadians can turn to when such questions arise. Worse, the French editors have chosen to proceed alphabetically, rather than by period, and have reached only “L.” The seventeenth-century official in question does not appear as Denarp and if he is to be remembered as de Narp, the more common spelling of this uncommon name, he will be indexed without the particle de, as Narp.4 Fortunately, questions of identity have become considerably easier to answer with the rise of serious historical content on the Internet, through such sites as Google Books, Internet Archive, and Gutenberg. A few hours of research online yielded a startling reference: the apparently obscure document of 1669 had long since been calendared, in a mid-nineteenth-century guide to manuscripts copied in the pre-Confederation Upper Canada Library of Parliament. This summary suggests the degree to which documents speak differently to different people, in different places, in different periods:

3 Given the survival of the report in the Archives de Colonies, it seemed possible that the superior whom Denarp addressed as Monseigneur was Jean-Baptiste Colbert himself, Louis XIV’s great Controller-General of Finances between 1665 and 1683. Colbert took a serious interest in industrial issues, including mining and even, from time to time, France’s transatlantic fisheries.6 The assumption that Denarp and Colbert were correspondents finds confirmation in Charles de La Roncière’s biography of the celebrated administrator, which cites a 1673 letter to Colbert from “l’intendant de Narp” in Saint-Malo.7 La Roncière used indendant here in a loose sense sometimes extended to military officers, for de Narp turns out to have been, more precisely, a commissaire de marine. A nineteenth-century collection of Colbert’s letters and instructions yielded another interesting document, as well as a crucial footnote. The document is an instruction from Colbert, dated 26 February 1670, addressed to “Sieur de Narp, Commissaire de Marine à Saint-Malo.”8 This is an important missive, at least for Newfoundland. To promote the French fishery there, Colbert gives the port of Saint-Malo the right to exempt certain skilled cod fishermen, such as “capelaners,” salters, and splitters, from the new classification system he has introduced to draft men into the navy.9 As we might expect, the commissaire de marine for Saint-Malo was deeply implicated in the administration of the migratory cod fishery. The crucial editorial note identifies him as “Philibert de Narp ou de Narpes, commissaire de marine à Brest, en 1668, puis à Saint-Malo. Mort à Rochefort, en 1679.”10 So the memorandum of 1669 is a report by a senior regional official in Brittany, with responsibility for issues relating to the transatlantic fishery, probably addressed to the French minister with the most power to turn suggestions into realities. How is it of interest?

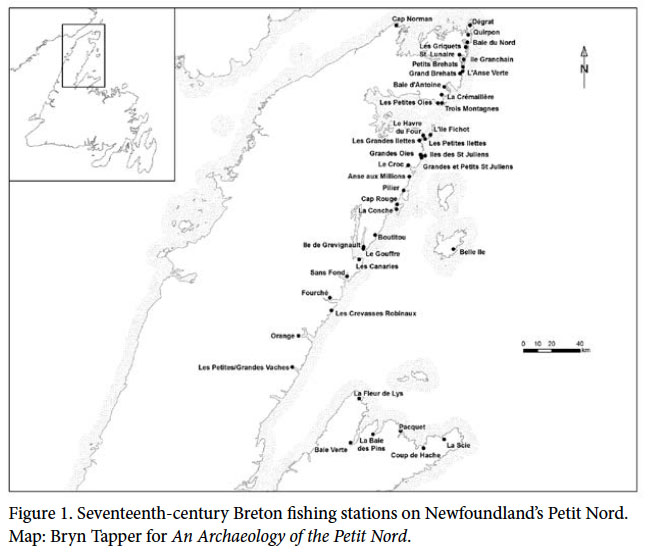

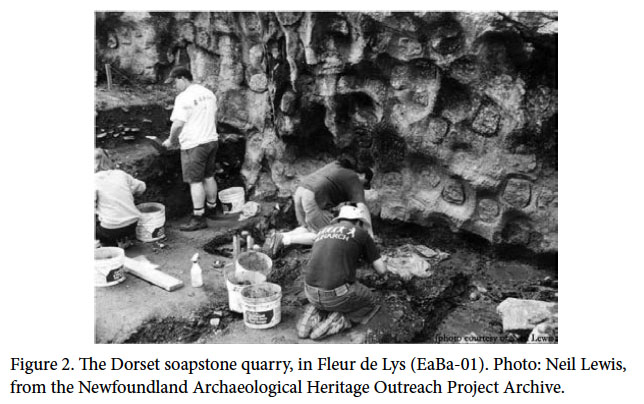

4 The attractive, well-protected harbour of Fleur de Lys lies on the Bay Verte Peninsula, east of White Bay, towards the southeastern limit of the Petit Nord, at least as it was known from the later seventeenth century (Figure 1). Denarp’s use of the term “Petit Nord” for the region, in 1669, is one of the earliest surviving official uses of the toponym. Fleur de Lys today is probably best known as the site of a soapstone quarry, exploited by Dorset Paleoeskimos, between AD 400 and 800.11 This unusual or, indeed, unique archaeological site was first brought to scholarly attention in 1915 by James P. Howley in his classic work on the Beothuk, the Algonkian people European mariners encountered when they found their way to Newfoundland at the turn of the sixteenth century.12 Within a few decades of Howley’s work, archaeologists had begun to establish the presence of earlier prehistoric peoples on the island of Newfoundland. In 1932, Diamond Jenness reinterpreted the Fleur de Lys site as relating to the Dorset, a Paleoeskimo culture, which he had recently identified in the high Arctic.13 Analysis of artifacts from the quarry, including the remains of soapstone pots and lamps, left archaeologists in no doubt that these are the remains of a Dorset industry.14 The site (EaBa-01) is striking, for it is hard to miss the pot scars, visible on the soapstone rock faces, where prehistoric quarriers worked patiently to remove sub-rectangular preforms, which they then finished to provide themselves with the sturdy, fire-proof vessels that formed such an important element of their portable technology and mobile subsistence strategies (Figure 2).15 In the decades since the main site was securely identified, it has been intensively excavated by the archaeologists Chris Nagle and John Erwin, who also identified other soapstone outcrops in Fleur de Lys, which likewise show evidence of Paleoeskimo exploitation.16 Local heritage activists have done an impressive job of bringing the Paleoeskimo quarry to life in the interpretation centre they have created to welcome visitors.17 Nor are the generations of French fishermen who used Fleur de Lys forgotten.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1 Display large image of Figure 2

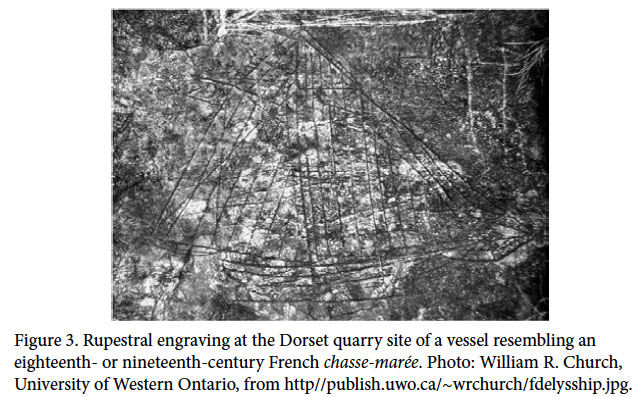

Display large image of Figure 25 Philibert de Narp’s memorandum of 1669 makes a number of interesting observations about French or, specifically, Breton operations in Newfoundland, but his summary of the report of Pierre Rouxel, who seems to have actually visited the Fleur de Lys quarry in 1668, has a special resonance for readers today, given the prehistoric cultural context we now give the site. To date, local interpretive efforts are almost the only way in which the French migratory crews of the early modern period have been introduced, at least conceptually, to the Dorset quarriers of the preceding millennium. While a number of historic carvings are evident on the soapstone outcrops, previous analysis has suggested that these are of twentieth-century origin.18 Archaeological survey elsewhere on the Petit Nord indicates that French crews did sometimes record their presence with rupestral inscriptions, particularly in the last half of the nineteenth century, during the decades of intensified conflict over the French Shore, once Newfoundlanders had begun to complicate what had previously been a simpler two-sided debate between Britain and France.19 At Fleur de Lys, some representations of small ships closely resemble the French chasse-marée of the nineteenth century or even a patache of earlier centuries (Figure 3). French naval charts of the early nineteenth century reflect a keen interest in local landforms.20 One of the most important traditional fishing rooms, l’Amirauté, is situated right next to the Dorset quarry. This proximity and Rouxel’s impressions, related to us by Denarp in 1669, strongly suggest that French fishing crews were familiar with the worked soapstone outcrops.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 36 Rouxel seems to have interpreted the quarry as a mine, because he recognized it as the scene of previous human industry. Reading between the lines of Denarp’s summary, the reader has the sense that Rouxel simply assumed quarrying reflected European activity and that it did not cross his mind to associate the site with Native peoples, even though he was vividly aware of their presence in the area. Rouxel asked for a place on the naval vessel usually commissioned, as he put it, “for the defence of the other ships, against the trouble that the savages might cause them.” The “sauvages” with whom French crews fishing on the Petit Nord fought, pretty well throughout the seventeenth century, were Inuit venturing south from the Labrador coast.21 The cultural relationship of this Neoeskimo people with their predecessors, the Dorset, is unclear, but there is no evidence that the Inuit ever used the Fleur de Lys quarry as their predecessors had. Unless Rouxel was misinformed, it does not make much sense to think that the samples he brought back to Brittany, identified as a lead ore, would have been soapstone. There is, geologically speaking, no particular reason to associate lead with soapstone. Soapstone or steatite is a metamorphic rock composed predominantly of talc — H2Mg3(SiO3)4. It is formed by the metamorphosis of magnesium-rich protoliths, for example serpentine. Lead, on the other hand, is normally extracted from galena or lead sulphide — PbS — which has no special association with either steatite or even its precursor, serpentine. Although we cannot know exactly what mineral Pierre Rouxel brought back to France, it is more certain that Monsieur Colbert would have been pleased to hear of a supply of lead.

7 With copper, tin, silver, and gold, lead was one of the metals officially considered manquant, that is “wanting,” in seventeenth-century France and, therefore, exempted from contemporary import controls.22 In 1665, Jean Talon, the Intendant of New France, made a serious effort to obtain lead from a mine in Gaspé, but by 1667 this effort had failed.23 Within a decade, the French did succeed in opening lead mines in what they called the Illinois country (now Wisconsin), mines productive enough to supply the French of the North American interior with ammunition.24 Brittany itself had been a source of the metal in ancient times and entrepreneurs would eventually redevelop lead mines there — but this was all later in the century. Thus, in 1669, a proposal to carry out prospecting for lead in a part of New France would have been remarkably timely.25 Is it possible, then, that Pierre Rouxel saw in the rocks of the Fleur de Lys quarry what he wanted to see?

8 Whatever encouraged Rouxel to take samples from Fleur de Lys as a possible ore, he was ahead of his time. The Bay Verte Peninsula lies on a belt of mineral-rich deposits.26 Tilt Cove, near La Scie, became the first major mining development in Newfoundland, after copper deposits were identified in 1857 and, in the later nineteenth century, became one of the largest copper mines in the world.27 The huge open-pit asbestos mine opened, in the 1950s, between Baie Verte and Fleur de Lys is better remembered in Newfoundland today, but mines in the area also produced copper, zinc, gold, and lead during this period. More to the point, in 1936, William Travers identified lead deposits at Fleur de Lys while exploring a deposit of molybdenum there. The Newfoundland Lead Company then opened an exploratory mine, less than a kilometre from the Dorset quarry. The modern mine operated only a year before it closed. At that time, the American geologist James Osborn Fuller produced a study of the geology and mineral deposits of the Fleur de Lys area, including both the contemporary lead mine and the local talc deposit.28 He noted one mass of talc, covering 6,000 square feet (a little over 200 m2 ) just west of the major metals deposits, pinpointing the quarry where the Dorset had extracted soapstone 1,500 years ago.

9 Early modern visitors to Newfoundland were often excited by resources which, in fact, would take centuries to develop. (The iron of Bell Island is another good example.) In this case, what triggered an interest in regional mineralogy was an archaeological extraction site, already a millennium old in 1667.

DOCUMENT

10 [Philibert] Denarp, “Memoire agnaux 1669 Terre Neuve Mine de Plomb, 1669,” France, Archives de Colonies, C11 C vol. 1, 29–30.

11 More might be said about this curious document but it surely speaks for itself. The transcription follows standard paleographic practice in regularizing the use of “u” and “v,” which were interchangeable in early modern documents. Denarp’s erratic spelling, capitalization, and punctuation are reproduced, although I have inserted expansions of certain abbreviations as well as a few identifications, full stops, and commas where these facilitate interpretation [all in square brackets]. Denarp’s own corrections are bracketed with carets “^”. My English translation follows the transcription.29

Memoire agnaux [anno] 1669

A Monsigneur

Terre Neuve

Mine de Plomb

12 Il y a Un An Au moys d’Aoust de l’an mil six centz soixte huict que le Nommé Pierre Rouxel Officier marinier natif de la Paroisse de Ploüer [Plouay, Morbihan, Bretagne] estant a la coste de Tereneufve lieu du Petit Nord en un Endroit Apellé vulgairement La fleur de lys ou on faict Pescherye de morües[.] Ledit Rouxel estant en Compagnye de quelques gens de dinan [Dinan, Côtes d’Armor, sur la Rance] il aurois decendu et mis pied a terre d’une Chaloupe au d’ [dit] Lieu de La fleur de lys y faisant L Chasse sur le bord de la Coste et estant dans le fondz d’une Baye y auroit remarqué pres d’un Ruisseau Trois Testes [têtes] de Pierres quy luy ressemblent estre Pierres de mines[.] sa Curiosité luy en fit amasser quelques morceaus qu il a porta en france et en fit faire l’assai Par un fondeur de gardes d’Espeés apelle Julien Guillaume habitans de Dinan quy fit fondue la d’ piere quy luy rendit comme de la crasse de Plomb [.] La quantite de ce qu’en avoit porté Le d’ rouxel n’ayant ^peu^ en fournir aucune masse mais ce fondeur asseure que c’est d’une mine de laquelle on tire Le corps du Plomb /

13 L’endroit ou s’est faict cette deccouverte semble ^Propre^ suivant le Raport du d’ Rouxel y aïant autour de beaux bois et un Ruisseau fort beau la Scituation n’en estant pas mesme desagreable.

14 Les trois Testes de ces mines sont distantes les Unes des autres denvïron douze Pas et Chacunes Trois A quatre Piedz de hauteur sur Terre et de Rondeur sept a huict ce quy en Couvre les distance sont Caillou [.] le d.’ Rouxel croit que la d.’ mine avance dans le bois [,] suivant le mesmoire quil en a fourny.

15 Comme il doit s’embarquer ce printems il s’offre A Monseigneur de se transporter sur le mesme Lieu ou il avoit pris les Sur d.’ eschantillons des aporter une quantité de laquelle il s en puisse Tirer un Essay quy face Conetre la Verité de Cequil met en avan[.] mais[,] comme les Vaisseaux quy partent de Celieu pour Terreneufve ne sont pas Toujours asseure de fixer Positivement Un havre et que mesme ni que [quel?] Contremre [Contremaître] de vaisseau, il dit que l on luy face donner une Place sur le navire qu’on arme ordin~ [ordinairement] Pour la deffence des autres Vx [Vaisseaux] Contre le trouble qu leur peut arriver Par les Sauvages[.] Le d’ Rouxel Promet de Passer a l’effect ce qu il fournit dans son Mesmoire[.] l’officier du d’ Vau marchand armé en guerre ne fera pas de difficulté de donner au d’Rx [Rouxel] Une de Pataches qu il dettache de son d.’ Vau pour Veiller incessement a la conservation des Autres et le Poste du havre La Fleur de lys a Rouxel[,] qui faisant son devoir servera autant qu’il pourra de la d.’ [dite] Pierre de mine Sans qu il en Couste Aucune chose pour en avoir Cet Automne Prochaine.

16 Voila Monsigneur ce que jay tiré du mesmoire que Cet officier marinier ma fourny signé de Luy et d’une Lettre du fondeur, qu il m a Escrite /

Denarp

Report anno 1669

My Lord

Newfoundland

Lead Mine

17 It was last year in the month of August 1668, that the said Pierre Rouxel, ship’s officer and native of the parish of Plouay [in the Bay of Morbihan, Brittany], being on the coast of Newfoundland, on the Petit Nord, in a place commonly called Fleur de Lys where they carry on a cod fishery, the said Rouxel, being in the company of people from Dinan [in Côtes d’Armor, on the Rance, inland of Saint-Malo], disembarked from a chaloupe and set foot ashore at the said Fleur de Lys, being engaged in hunting along the coast and being at the bottom of a bay, he remarked, near a brook, three stone outcrops which to him seemed to be the rocks of mines. His curiosity led him to collect several pieces, which he carried back to France and had an assay done by a caster of sword guards, called Julien Guillaume, inhabitant of Dinan, who melted the said stone and made it like lead slag. The quantity that the said Rouxel had brought not being much, it did not produce a mass — but the founder guarantees that it was from a mine which yields lead ore.

18 The place where this discovery was made seems to be convenient, according to the said Rouxel’s report, near fine woods and a very handsome stream, the location being not disagreeable.

19 These three mineheads are about a dozen paces one from another and each one is three or four feet high above the ground and seven or eight around, with pebbles covering the ground between them.30 The said Rouxel thinks that the said mine continues into the woods, according to the report about it, which he supplied.

20 Since he must re-embark this spring, he offers his services to Monseigneur, to go back himself to the same place, where he took the aforesaid samples, to bring back a quantity which would enable him to obtain an assay which would make known the truth of what he has put forth. However, as the ships which depart from here for Newfoundland are not always positively sure of their choice of harbour there nor even of the ship’s contremaître, he asks to be given a place on the ship that is normally commissioned for the defence of the other ships, against the trouble that the savages might cause them.31 The said Rouxel promises to bring into effect what he mentioned in his report. The officer of the armed merchantman will be at no trouble to give the said Rouxel one of the pataches detached from his ship to watch constantly over the safety of the others and the station of the harbour of Fleur de Lys to Rouxel, who doing his duty will do as much as he can to get the said mine stones, without any cost, for next autumn.32

21 There you have it, Sir, what I have drawn from the report, submitted to me and signed by this ship’s officer and from a letter written to me by the caster.

Denarp