Research Notes

“No More Giveaways!” Resource Nationalism in Newfoundland:

A Case Study of Offshore Oil in the Peckford and Williams Administrations

INTRODUCTION

1 When channelled into policies, resource nationalism can provide jurisdictions with the ability to maximize the benefits of resource exploitation. Since the earliest days of responsible government in the 1850s Newfoundland politicians have pursued a number of resource-driven projects to further develop the economic and social well-being of their citizens (and sometimes, themselves) under bombastic catchphrases such as “develop or perish,” “burn your boats,” and “no more giveaways” (Thomsen, 2010: 134). While there have been notable writings on Newfoundland nationalism generally (see Vezina and Basha, 2014; Marland, 2010; Cadigan, 2009; Hiller, 1987; Overton, 1979), little attention has been paid to a comparative assessment of resource nationalism in the province, particularly between different administrations. This essay attempts to rectify this oversight.1 In doing so it improves our understanding of the role resource nationalism plays in a sub-state jurisdiction by examining the policy prescriptions and actions of two provincial administrations — Progressive Conservative (PC) Premiers Brian Peckford (1979–89) and Danny Williams (2003–10) — as they attempted to wrest benefits from offshore oil development.

2 There is, notably, a 14-year gap between these two governments, a gap that was largely presided over by the Liberal premierships of Clyde Wells (1989–96) and Brian Tobin (1996–2000). While it is certainly true that both Wells and Tobin were involved in high-profile battles — in the case of Wells, with his federal counterparts, and in the case of Tobin, with major companies and foreign powers — neither Premier pursued a resource nationalist approach concerning oil. This can largely be explained by the low price of oil during the period, the unavailability — until November 1997 — of an operating oil field (Hibernia), and a constant preoccupation with the collapse of the cod fishery. While numerous post-Confederation premiers have adopted resource nationalist stances in other sectors, including fishing, mining, and hydro development, resource nationalism has been most prominent in the move to derive benefits from the offshore oil sector.

3 By focusing on Newfoundland’s experience with resource nationalism in the offshore oil sector this article contributes to the qualitative theoretical debate twofold; first, by analyzing a small, developed sub-jurisdiction this article adds to the comparative case studies on resource nationalism that oſten are focused on the Middle East, Latin America, and the former Soviet Union. Second, in the Canadian context, what little scholarly work has been done on resource nationalism is Alberta- and Quebec-centric (see Goldstein, 1981; Bradbury, 1982). This essay reorients the debate to one of Canada’s smaller provinces, providing another useful comparison on the role resource nationalism plays in federal–provincial relations.

4 Our analysis will first provide a short theoretical overview of resource nationalism. That summary will be followed by a brief explanation of Newfoundland nationalism with a particular focus on the historical factors that have fashioned nationalism in the province and on how numerous governments have used nationalist policies to diversify the local economy. Following that are the two case studies: the Peckford and Williams administrations. Those sections will highlight the resource nationalist actions and policy prescriptions taken by each leader towards obtaining a greater portion of the rents from both the federal government and, in the case of Williams, from international oil companies in the province’s offshore oil industry. Finally, this paper will conclude with how the province’s experiences with this most recent bout of resource nationalism compares and contrasts with the theory.

RESOURCE NATIONALISM

5 While governments have been claiming control over resources since Roman times, “resource nationalism” is a much more contemporary concept, tracing its roots to mid-nineteenth-century economic nationalism (Helleiner, 2002: 309; Bond, McCrone, and Brown, 2003: 371; Ross, 2012: 33). That being said, resource nationalism emerged as an ideology in its own right only in the two decades following World War II (Helleiner, 2002: 309). Influenced by the combination of Keynesian economic thinking, the perceived economic success of state-owned corporations in the Soviet Union, and the “conceptualization of market failure,” resource nationalism became adopted as a form of state economic policy in both developed and developing countries in the 1960s and 1970s (Domjan and Stone, 2010: 38; Stevens, 2008: 7; Ross, 2012: 39).2

6 The general idea driving resource nationalism is the fixation on controlling and exploiting natural resources; yet, the term remains contested, frequently used but lacking a universally accepted definition. Nevertheless, a brief literature review can extrapolate a succinct understanding of what the term implies. At its most basic, resource nationalism is closely allied with economic nationalism. As Robert Gilpin notes, economic nationalism refers to those “economic activities [that] are and should be subordinate to the goal of state-building and the interests of the state” (Gilpin, 1987: 31; see also Helleiner, 2002: 309). Within that framework one can place resource nationalism, a concept that articulates the view that “the natural resources in the ground or under the sea are the property of the nation rather than of a firm or individual who owns the surface area” (Mares, 2010: 6). In effect, resource nationalism views natural resources as representing a “national patrimony” that “should be used for the benefit of the nation rather than for private gain” (Mares, 2010: 6). Resource nationalism posits that territories with an abundance of a particular natural resource should use their “legal jurisdiction over these resources to achieve some set of national goals that would otherwise not [be] obtain[ed] if their exploitation were leſt to international market processes” (Wilson, 2010: 3).

7 Differences, however, emerge over what policy prescriptions are implied in resource nationalism. Bremmer and Johnston (2009: 149) argue that proponents of resource nationalism are more concerned about shiſting political and economic control of natural resources from private and foreign companies to state-owned enterprises. Stevens contends that we need to examine the range of elite-actor motives behind resource nationalist policies to ascertain an explicit understanding of what the term references. For him, resource nationalism can be defined by two core components: (1) limiting the involvement of major international businesses; and (2) “asserting a greater national control over natural resource development” (Stevens, 2008: 5–6). Thus, resource nationalism “encompasses both the reassertion of state control prior to the end of the construction phase of a development and the outright exclusion of foreign participation” (Domjam and Stone, 2010: 38). However, resource nationalism need not be exclusively defined by those policies that lead to total nationalization of a resource industry; it can also include policies that derive more financial benefit from the privately managed resource.

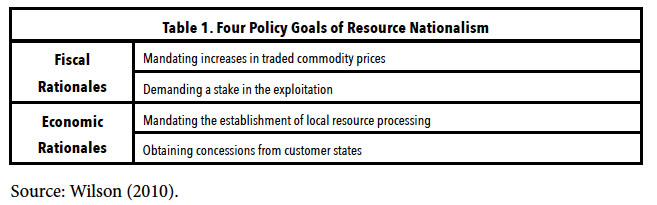

8 Consequently, for many resource-rich states there continually exists public pressure to garner better development benefits through state interventionist policies (Wilson, 2010: 3). In this context, Wilson has noted that, generally, four policy goals underpin resource nationalism: (1) capturing more revenue “by mandating increases in the traded prices of commodities”; (2) capturing more revenue by demanding a stake in the exploitation; (3) mandating the establishment of local resource processing and manufacturing through contractual negotiations with foreign corporations; (4) and obtaining “(non-resource related) concessions from customer states, through the use of various forms of ‘resource diplomacy’” (Wilson, 2010: 4). These goals can be divided into fiscal and economic rationales (see Table 1). Fiscal policy goals are focused on obtaining more direct cash into the treasury while economic goals are more concerned about jobs and other indirect benefits. Of course, the common thread underlining each goal is to derive more benefits out of the resource exploitation than would have been possible had there been no intervention.

Display large image of Table 1

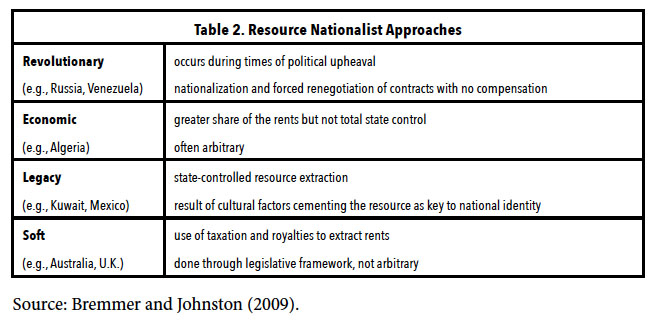

Display large image of Table 19 These goals, in turn, can be classified into four approaches: (1) “evolutionary resource nationalism”; (2) “economic resource nationalism”; (3) “legacy resource nationalism”; and (4) “soſt resource nationalism” (Bremmer and Johnston, 2009: 150–51; see Table 2). The first, revolutionary resource nationalism, occurs during times of political upheaval (e.g., Vladimir Putin’s renationalization of the oil and gas sector in Russia). It usually leads to the forced renegotiation of contracts under the rhetoric of “historical injustice or alleged environmental or contractual misdeeds by . . . companies” (Bremmer and Johnston, 2009: 150). There is oſten zero compensation or recourse of action for those companies affected.

10 Economic resource nationalism is less concerned about total state control. Rather, economic resource nationalist policies remain focused on increasing the state’s share of the rents, either through operating state-owned resource companies or through obtaining a larger share of the private sector’s revenues using legislative means (e.g., Algeria). Oſten done arbitrarily, the ultimate outcome is a greater share of the revenues, not so much controlling the resource. Third, legacy resource nationalism occurs in jurisdictions where the resource is “central to national political and cultural identity” (Bremmer and Johnston, 2009: 151). States with legacy resource nationalist policies will place the resource under the control of a state-owned enterprise. The final variant, soſt resource nationalism, is found most oſten in developed countries (e.g., Australia and the UK). Today, there is little in the way of state-owned resource companies in such countries; however, fiscal policies in the form of taxation and royalties are implemented to extract a percentage of the rents. These nationalist policies, unlike economic resource nationalism, are not done arbitrarily but through established legislative and regulatory frameworks (Bremmer and Johnston, 2009: 152). Moreover, even when the rare forced renegotiation occurs, it still is subject to regulatory, legislative, and legal review (i.e., there is a recourse of action for the affected companies).

Display large image of Table 2

Display large image of Table 211 The strengths and weaknesses of resource nationalist policies, especially as they relate to oil, also have been well documented. As the 1973 OPEC crisis demonstrated, an increase in the price of a strategic commodity like oil can alter the bargaining power between states and industry (Ross, 2012; Vivoda, 2009; Bremmer and Johnston, 2009: 155–57). When prices are high there is said to be “disharmony” between governments and industry; consequently, “host governments rethink their contracts and seek higher taxes and royalties” (Vivoda, 2009: 517–18). During these times resource nationalism, in popular sentiment and in government rhetoric, is on the upswing. However, the corollary also is true; when prices are low governments are more willing to concede a larger share of the rents in exchange for industry investing in developing the resource. In such situations, resource nationalist feeling is suppressed and government-industry interactions are characterised as “co-operative” (Vivoda, 2009: 521). Such co-operation was quite apparent in numerous jurisdictions during the late 1980s and 1990s when oil prices were at record lows, including in Newfoundland. Vivoda (2009: 519) further contends that the lack of resource nationalist policies globally during those two decades can be explained by three factors that are prescient even today: (1) states over-reliant on oil became desperate for more foreign investment when prices were low; (2) international oil companies, with a near-monopoly on technological sophistication and managerial competence, faced little or no competition from state-owned industries; (3) and private oil companies had other investment alternatives should they be denied a favourable domestic revenue-making environment.

12 In light of the above, the cyclical nature of commodity prices also highlights the dangers in resource nationalist interventionism. When it comes to earning oil revenues during a time of high prices, for example, governments will oſten cut taxes. The downside is that by removing a stable form of earning revenue, government finances become dependent on a volatile commodity over whose price they have little control. For example, in 2008 the Venezuelan government spent at the rate of $75 a barrel but had based its budget estimates on oil trading at $35 a barrel. It had become politically unfeasible to derive other forms of revenues and thus the country became financially vulnerable (Bremmer and Johnston, 2009: 152). The Venezuelan case speaks to another truism: short-term resource nationalist policies are popular and politically sellable but can carry long-term risk. Still, they can make good economic sense if the population in question has gone through a period of heavy taxation or when public infrastructure and services require large, quick injections of cash (Ross, 2012: 31–33; see also Karl, 1997). Not surprisingly, the influx of oil revenues has also been noted to foster larger government bureaucracies. It has been estimated that, on average, the governments of oil-dependent states are 45 per cent larger than non-oil-dependent states (Ross, 2012: 29).

13 Some resource nationalist policies also carry the risk that they can deny governments access to the necessary foreign expertise and investment to “expand, or even sustain, the output and revenue streams they need for long-term survival” (Bremmer and Johnston, 2009: 152). Thus, while they are oſten the main focal point of consternation behind the very pursuit of resource nationalist policies, the same major international businesses remain the experts in the technological complexities of resource extraction and management. Such expertise, of course, is needed to ensure efficient and productive extraction. Likewise, resource nationalism can oſten delay projects as whatever leverage governments may think they have during times of high prices belie the fact that large resource companies operate in a global marketplace. Delays in one jurisdiction can oſten translate into industry shiſting focus to extraction in another, as Vivoda notes. This was most evident in the 1970s when a rash of nationalizations in OPEC countries saw private industry shiſt to oil exploration and production in the North Sea and Alaska (Bremmer and Johnston, 2009: 155).

NEWFOUNDLAND NATIONALISM

14 A resource nationalist critique of Newfoundland is apt in consideration of island nationalists’ long-held goal to both exercise control and obtain benefits from natural resource exploitation (Overton, 1979: 226; Hiller, 1987; Bannister, 2003). To understand the role of resource nationalism in Newfoundland politics over the last 30 years one must first understand the currents of history that flow through Newfoundland nationalism. Newfoundland’s historical evolution as a self-governing territory has seen its identity characterized by two constants: (1) its political leaders frequently articulate a belief that the nation’s future is tied to the ability to exploit its natural resources; and (2) these same leaders lack the ability to control such resources or at the very least to provide policy guidance on how to accrue some of the financial benefits. Though conscious of the fact that Newfoundland governments were perpetually negotiating from “a position of weakness,” the inability to have such control has become a common refrain in explaining Newfoundland’s economic backwardness (McAllister, 1982: 123). Importantly, this thinking fuelled the notion that the nation’s economic struggles were the responsibility of outsiders, which in the pre-Confederation period meant fishing merchants, the government of Canada, and such foreign powers as France (Hiller, 2007: 116; Bannister, 2003: 147). In the case of oil and gas development in the post-Confederation period this blame would shiſt to Ottawa and international oil companies. For Newfoundland citizens, this “version of events” fostered an image of a people who had been “the victims of a hostile imperial policy that was antithetical to the establishment of a settled colonial society, which had emerged nevertheless thanks to the efforts of the hardy and resilient settlers” (Hiller, 2007: 117; see also Bannister, 2003: 147).

15 Cognizant of running a thinly populated country whose people remained scattered among hundreds of coastal villages and overly reliant on one resource — the fishery — Newfoundland nationalists became fixated on devising policies to diversify the local economy. This effort was most pronounced with the building of the railway during the 1881–98 period (Overton, 1979: 221–22; Korneski, 2008). The impetus behind this nationalism was largely “economic development . . . [with] the nation state as the main building block” (Overton, 1979: 222). The nationalist cause was further bolstered in the early twentieth century by the populist leadership of Prime Minister Sir Robert Bond. Associated with a period when Newfoundland was relatively prosperous, Bond has long been mythologized for having “stood up for Newfoundland” against Ottawa, London, and big business — a trait Newfoundlanders expect in their leaders today (Hiller, 2007: 121).

16 Since Confederation in 1949, and with the exception of a dispute with Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker over federal transfers 10 years later, Newfoundland nationalism remained largely dormant during most of Liberal Premier Joseph Smallwood’s 22 years in power. Nevertheless, the earliest signs of a re-emergence in nationalist sentiment began late in the 1960s. Despite Smallwood’s rhetoric of Confederation being a great “giſt” to the province, aſter the post-Confederation construction boom began to wind down in the mid-1960s Newfoundland began an economic slide that carried into the 1970s (Gwyn, 1972; Horwood, 1989; Cadigan, 2009a). As a result, the provincial treasury became more dependent on federal transfer payments. Combined with a growing intolerance of Smallwood’s leadership, this dependence was particularly resented by the new, urban middle class, who were benefactors, ironically, of Smallwood’s establishment of Memorial University in 1949 and of the increase in the standard of living brought about by federal social programs and infrastructure investment (Overton, 1979: 227; Hiller, 1987; Hiller, 2007: 130; Cadigan, 2009b: 41). This period also witnessed a cultural revival in the province — particularly in the urban areas — with theatre groups like CODCO stressing the province’s distinctiveness and the need to protect its songs, customs, and dialects (O’Dea, 2003: 378; Hiller, 2007: 130; Cadigan, 2009b: 41). Notwithstanding these changes, Newfoundland nationalism has not verged into outright secessionist sentiment — a point worth remembering (Thomsen, 2010; Vezina and Basta, 2014).

17 Coinciding with these cultural, social, and economic changes was the 1969 agreement to build one of the world’s largest hydroelectric facilities: in Labrador, at Churchill Falls. Operating under the rubric of “develop or perish” (incidentally, the same phrase used in pre-Confederation times for resource development), Newfoundland entered into a deal with the province of Quebec and a coalition of international business interests to develop the Churchill Falls dam (Horwood, 1989; Marland, 2010). The aim of the project, outside of the immediate construction jobs, was to place the province as a strategic supplier of electricity to the eastern United States. Instead, through the machinations of federal–provincial politics at the time, Quebec support for the project was essential and it co-operated only on the condition that the power be sold to its provincial energy utility, Hydro-Québec, at exceptionally low prices until 2041 (Churchill, 1999; Feehan and Baker, 2007; Marland, 2010: 161; Feehan, 2011a). Unfortunately for Newfoundland, Hydro-Québec continues to reap the gains from that project due to its access to almost all the electricity for which it pays an incredibly low price. By the early 1970s, particularly aſter the OPEC crisis, it had become clear that Smallwood’s Churchill Falls deal amounted to a major “giveaway” of a valuable “national” natural resource. To the urban middle class, in historian Sean Cadigan’s words, the deal “became symbolic of Newfoundland’s weak position within Confederation” (2009b: 40–41). More importantly, the Churchill Falls deal became a focal point for stimulating the resource nationalist drive among the wider public, leading to calls for both greater provincial control over natural resources and a larger share of the rents. Churchill Falls and the phrase “no more giveaways” would become the rallying cry of succeeding generations. And it would shape the future governments of Premiers Peckford and Williams in their quest to obtain better “deals” over the province’s new-found oil wealth (Hiller, 2007: 130–31; Cadigan, 2009b: 41; Bannister, 2012: 212–13).

THE PECKFORD YEARS (1979–89)

18 Unfortunately for Newfoundland’s premiers, the first sign of potential oil deposits off Newfoundland occurred in the late 1960s, around the same time that the Supreme Court of Canada ruled offshore petroleum development to be a federal prerogative (Plourde, 2012: 100).3 Tellingly, then Premier Joey Smallwood claimed provincial jurisdiction over offshore resources, laying the foundation for future clashes between the province and Ottawa. Smallwood at one point dispatched a deep-sea diver to walk the floor of the Grand Banks and claim ownership of the offshore resources, but this was as far as he would go in advancing the province’s claim (House, 1985: 55). With the change of government in the 1970s, prior to any commercial discovery off Newfoundland, a small group of advisers in the provincial Department of Mines and Energy designed a petroleum development policy based on the Norwegian state intervention approach to oil extraction. Among this group were departmental legal adviser Cabot Martin, the assistant deputy minister, Steve Millan, and economic consultant Pedro van Meurs (House, 1985: 47–48). Led by their minister, Brian Peckford, these individuals set out to establish resource nationalist policies that would promote “development through regaining control and through good management of the major resource industries,” of which oil was the most prominent (House, 1985: 48). Their overarching goal was threefold: (1) achieve provincial autonomy; (2) preserve the rural way of life and culture; and (3) achieve the first two goals by adopting “a controlled approach to resource exploitation and development” (House, 1985: 44; Thomsen, 2010: 130).

19 Their first move was to create the province’s own petroleum legislation and regulations, An Act Respecting Petroleum and Natural Gas, in 1977, with corresponding regulations produced in 1978 (House, 1985: 49–50). Oil companies initially halted exploratory drilling in protest but returned to operations the following year (Higgins, 2011). Notably, these regulations were a direct application of the North Sea oil development model used by the Norwegians and advanced in the 1960s (House, 1985: 56), a position later endorsed by the Economic Council of Canada in its 1980 study of Newfoundland (McAllister, 1982: 127). Embedded within the regulations were seven policy goals:

- Obtain the biggest portion of the economic rents for the province.

- Establish Newfoundland as an active participant in developing off-shore petroleum through the use of a Crown agency, the Newfoundland Petroleum Corporation.

- Give local businesses first right of refusal on oil supplies and servicing contracts.

- Ensure that oil companies give Newfoundlanders a preference in hiring.

- Require the expenditure of a certain amount of corporate budgets on training, education, and research.

- Ensure that Newfoundland’s petroleum needs are met during allocation.

- See to it that any and all oil developments must minimize “adverse impacts upon local communities” (House, 1985: 50).

20 The following year, 1979, would prove a turning point in the pursuit of resource nationalism in Newfoundland. With the resignation of Frank Moores that March, Peckford became Premier, the Hibernia oil field was discovered, oil prices climbed rapidly, and the province was beset by both a national and international recession (Thomsen, 2010: 137). With the Hibernia discovery there was finally a real possibility of commercial development. The problem for Peckford was the dual constraint of having to contend with a centralizing Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau, and the federal claim to jurisdiction over offshore resources, reinforced by the Supreme Court’s 1967 decision. Initially, there was some respite on the first charge as Trudeau’s defeat in the federal election of 1979 brought in a young Progressive Conservative Prime Minister, Joe Clark. An Albertan, Clark promised to treat offshore resources the same as those on land (as they were in his home province), effectively giving Peckford what he wanted. This hope was dashed with the defeat of the Clark government in February 1980. The return of the Liberals under Prime Minister Trudeau signalled a period of bitter public bargaining and political manoeuvring, especially when Ottawa passed Bill C-48 in 1981 to create the National Energy Program on the presumptive basis that offshore resources were under federal control (House, 1985: 56–57). Moreover, the political battling between the two governments stifled investment in the offshore as businesses hesitated to spend large sums of money in such an uncertain climate. The ripple effect of the jurisdictional disputes prolonged the date when oil could actually be extracted (Plourde, 2012: 101). Nevertheless, three months aſter the 1980 federal election, the first round of talks between Newfoundland’s new Energy Minister, Leo Barry, and his federal counterpart, Marc Lalonde, ended in failure. During January and February of 1981 talks resumed but failed again. Barry resigned and his replacement as provincial Energy Minister, William Marshall, met with Lalonde in October of that year but they were not able to reach an agreement, and despite attempts by the province to continue the discussion they were receiving no response from the federal government on new proposals.

21 During this period, 1979–83, Peckford’s rhetoric consistently reflected a resource nationalist theme, mimicking the tensions between St. John’s and Ottawa, and reflecting the goals outlined in his legislation. The 1979 Throne Speech, the first for Peckford as Premier, declared that “our ownership of and control over our offshore oil and gas resources must be beyond question” (cited in Thomsen, 2010: 136). The 1982 Throne Speech cited offshore petroleum deposits as Newfoundland’s “birthright” and that the province needed to “seize the resources” from Ottawa in order to prosper (Thomsen, 2010: 137–38). Even the 1982 PC Party election slogan tried to capture the sentiment that control over offshore oil was the path to prosperity when it ran under the headline of “Have Not Will Be No More” (this slogan also became the title of Peckford’s memoirs). More explicit was Peckford’s 1983 manifesto, whereby he proclaimed that:

This is not to say that Ottawa was unhelpful. Offshore oil-drilling subsidies under the National Energy Program in many ways encouraged oil companies to maintain exploratory drilling during a time of depressed oil prices (Reid and Collins, 2013).

22 Peckford went out of his way to capitalize on and to mobilize public sentiment around his position. He created a new provincial flag, adopted the pre-Confederation national anthem — “The Ode to Newfoundland” — as the province’s anthem, poured money into arts and culture programs, and even called a snap election in April 1982, asking for a mandate to negotiate with Ottawa. He won an overwhelming victory with 44 of the 52 seats in the provincial legislature. However, the federal government seemed to be unimpressed by Peckford’s electoral success, and on 19 May 1982 announced that it would take the ownership issue to the Supreme Court of Canada. In response, Peckford had the Supreme Court of Newfoundland similarly examine the jurisdictional issue. The province’s case rested on Terms 7 and 37 of the Terms of Union, the document that proscribed Newfoundland’s transition from a Dominion to a Canadian province in 1949 (House, 1985: 58–59; see also Collins, 2012). In short, the province argued that as Newfoundland’s legal status as a self-governing Dominion was recognized in Term 7, and that Term 37 allocated mineral rights and royalties to the province, then Newfoundland held ownership over off-shore resources. In February 1983, the Newfoundland court responded that while Newfoundland was “not a province like all the rest” and that it was a self-governing Dominion equal to Canada in international law before 1949, it could not go against the national court’s earlier rulings on the federal right to control offshore resources (House, 1985: 58–59; Plourde, 2012: 101). In March 1984, the Supreme Court of Canada made its ruling that the sub-sea resources off Newfoundland belonged to Canada (Feehan, 2009: 176). In response, Peckford declared a provincial day of mourning and encouraged everyone in the province to wear black armbands — a position not unlike Smallwood’s three days of mourning and flags-at-half-mast actions in 1959 over Term 29 funding (Cadigan, 2009a; Bannister, 2012; Vezina and Basta, 2014). He promptly set out on a national tour for a “fair deal” with the rest of Canada (House, 1985: 60).

23 While the Peckford government was dealing with the Trudeau Liberals and the consequences of the Supreme Court decision, other events were occurring that would change matters considerably. Brian Mulroney won the leadership of the federal Progressive Conservative Party in June 1984. He and Peckford met soon aſter and reached a settlement on a proposed Atlantic Accord should Mulroney win the next election. This accommodating mood may have developed based on the crucial support given by both Peckford and third-place leadership contender John Crosbie of Newfoundland to Mulroney on the final ballot of the recent leadership convention (Crosbie, 1997; see also Mulroney, 2007: 248). In short, Mulroney promised that Newfoundland would be the principal benefi-ciary of oil development; that there would be joint management with Ottawa of offshore petroleum; that the province could collect resource revenues as if they were on land; and that equalization payments would continue for a period of time once oil revenues started to come in (House, 1985: 60).

24 On 4 September 1984 Mulroney led the Tories to a huge electoral victory. Two months later provincial Energy Minister Marshall met the new federal Energy Minister, Pat Carney, to work on the details of the Accord. The predevelopment round of the dispute between the federal and provincial governments was resolved on 11 February 1985 when Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and Premier Brian Peckford signed the Atlantic Accord. As per the original pre-election agreement, the Accord gave both governments equal partnership in the management of offshore oil and gas resources and gave the province access to revenues — in the form of royalties, corporate taxes, and provincial taxes — from offshore development similar to those received by provinces from land-based oil and gas (Feehan, 2009: 177; Bickerton, 2008: 101). In terms of equalization payments, the Accord allowed for a transition period of 12 years during which offset payments would be allocated to the province as compensation for any oil revenues loss in the equalization formula. This component of the Accord would take place once Hibernia’s “cumulative production had reached a specified threshold” (Feehan, 2009: 178). The federal government would reach a similar agreement with Nova Scotia in 1986. Much of the 1977 regulations became either disavowed or folded into the new joint management board, the Canada–Newfoundland Offshore Petroleum Board.4 While hardly the autonomist vision Peckford initially wanted, this arrangement between the two levels of government cleared the way for the signing of an agreement with the consortium of companies in 1990 to proceed with the development of the Hibernia oil field.

THE WILLIAMS YEARS (2003–2010)

25 Much like Brian Peckford’s policies, the foundations of Danny Williams’s resource nationalist policies were rooted in the province’s poor fiscal health and a sense that Newfoundland was being shortchanged on offshore oil revenues. Even before he took office in the fall of 2003, Williams, as leader of the PC Party, was running on a theme of “No More Giveaways” (Vezina and Basta, 2014). This similarity was particularly acute when, in 2002, he criticized Liberal Premier Roger Grimes’s Voisey’s Bay nickel deal with mining giant Inco as being unbeneficial (Koop, 2014). However, and despite the fact that Hibernia was producing oil when Williams came to office in 2003, the prevalence of extremely low oil prices meant that very few benefits were coming into the provincial treasury. In his first year in office Williams was faced with a severe fiscal situation, the province’s per capita debt and debt-to-GDP ratio being among the worst in the country (Bickerton, 2002: 294). In a live television address to the province, the new Premier announced wage freezes for public employees and program cuts (Feehan, 2011b: 51). That same year the Royal Commission on Renewing and Strengthening Our Place in Canada, a creation of the previous Liberal administration of Roger Grimes, released its final report examining the province’s status in Canada. A key component of the Commission’s findings was the need to maximize Newfoundland’s share of off-shore oil revenues, which it claimed were being lost to equalization “clawbacks” (Bickerton, 2002: 290; Feehan, 2011b: 51).

26 Designed in the 1950s and enshrined in section 36 of the Constitution Act, 1982, the equalization program commits the federal government to make payments to fiscally weak provincial governments so that each province has “sufficient revenues to provide reasonably comparable levels of public services to all Canadians at reasonably comparable levels of taxation” (Bickerton, 2008: 100–01). The program was critical for the Newfoundland treasury, accounting for 25 to 33 per cent of all government revenues between 1967 and 2003 (Bickerton, 2002: 294). Suffice it to say, while the 1985 Atlantic Accord had promised to make Newfoundland the principal beneficiary of oil revenues, the design of the equalization program at the time meant that in practice the Newfoundland government’s equalization grant would decline by about 70 cents for each dollar of offshore oil revenue it received. The 12-year transition period of equalization offsets outlined in the Accord had already started in 1999–2000 amid a period of low oil prices (Feehan, 2009: 178). The Commission concluded that the Accord was inhibiting the province from gaining the most benefits from offshore oil, especially with two oil fields coming on stream in addition to Hibernia: Terra Nova and White Rose. Taking a long-term perspective the Commission determined that the federal government would accrue 76.7 per cent of the oil fields’ tax revenues, compared to Newfoundland’s 23.4 per cent (Feehan, 2009: 179). With austerity measures on the horizon the Williams administration became determined to put the Commission’s recommendation into action and accrue 100 per cent of the clawback oil revenues from the federal government — without any loss of equalization payments over the life of the oil fields.

27 Possibly due to the prospect of the federal Liberals obtaining a minority government in the June 2004 federal election, Williams was able to get Liberal Prime Minister Paul Martin, during a campaign stop in St. John’s, to agree to the demand of not including oil revenues in equalization calculations over the life of the oil fields (Feehan, 2011b: 51). However, resistance from Ontario and the federal bureaucracy led to a prolonged delay in responding to Williams’s proposal upon Martin’s return to the Prime Minister’s Office that summer (Feehan, 2011b: 52). It would take until October 2004, at a First Ministers’ Conference, during which the Prime Minister announced major changes to the equalization formula — with the federal government still claiming “70 cents in equalization for every dollar earned in offshore energy revenues” — that Williams made a great public spectacle, storming out of the meeting claiming Martin had broken his promise (Feehan, 2011b: 51–52; Library of Parliament, 2006: 10; Smith, 2005: 19–20).

28 The back-and-forth exchanges continued until two days before Christmas Day 2004, when Williams ordered the taking down of all Canadian flags on provincial buildings (Feehan, 2011b: 51–52). This move, akin to Peckford’s “day of mourning” actions two decades earlier, proved highly popular in Newfoundland. By January, with the flags having returned to the poles and the public clearly backing him, Williams and Martin agreed to a new Offset Agreement, complementing the original Atlantic Accord. Specifically, Ottawa agreed to compensate Newfoundland for 100 per cent of oil revenues lost as a result of clawbacks up to 2011–12, one year beyond the end of the original 12-year transition period outlined in the 1985 Accord. The province would receive a $2 billion up-front “pre-payment” for the anticipated clawback money ending in 2011–12 (Feehan, 2011b: 52). Should Newfoundland qualify for equalization in 2011–12, and its “debt-servicing charges remain high,” an eight-year renewal agreement would kick in, providing 100 per cent compensation on offshore revenues through to 2019–20 (Library of Parliament, 2006: 10; Smith, 2005: 20). Nova Scotia also received an identical Offset Agreement for its offshore natural gas industry. But Williams did not get all he wanted. As a Library of Parliament study (2006: 10) on the agreement remarked, there was no alteration to the equalization formula and there would be no compensation of revenues for the life of the oil fields. Still, with oil prices climbing, the provincial treasury soon became flush with cash.

29 Williams would try to repeat his success against newly elected Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper in 2007. In the 2006 federal election that unseated Paul Martin, Harper had promised Williams that he would not include natural resources in the equalization formula. But in 2006, the report of Expert Panel on Equalization and Territorial Formula Financing, otherwise known as the O’Brien Report, commissioned under the previous federal Liberal government, recommended that 50 per cent of all natural resource revenue be included in equalization calculations and that equalization payments be capped so that a recipient province’s fiscal capacity did not exceed that of Ontario (then, the lowest non-receiving province). Harper’s 2007 budget implemented many of the report’s key recommendations, “which effectively killed the federal commitment in the Atlantic Accords to delink the offshore oil and gas revenues of Newfoundland and Labrador and Nova Scotia from their equalization entitlements” (Bickerton, 2008: 102; see also Feehan, 2009: 176). While Nova Scotia reached an alternative arrangement in light of these changes, Danny Williams refused; although with Ottawa receiving four times the revenue from Hibernia that Newfoundland got ($4.8 billion to $1.2 billion) that year, Williams’s indignation was largely justified (Bickerton, 2008: 103). The Premier immediately took to targeting Harper in speeches, demanding that the Prime Minister’s promise be kept. In October 2007 the province went to the polls again. In a move that was highly reminiscent of Brian Peckford’s 1982 election campaign, Williams pitched himself as defender of the province’s interests (Koop, 2014). The PC Party’s platform that year focused on Harper’s broken pledge, declaring that Harper “did not honour . . . [his] commitments” (cited in Koop, 2014). Reflecting Williams’s approach to natural resources, the platform further stated that “The days of resource giveaways are gone” and that Newfoundlanders were now “masters of our own house.” This latter saying was a direct resuscitation Quebec Premier Jean Lesage’s “Maîtres chez nous” campaign slogan in 1962, a phrase that led to the nationalization of that province’s electricity sector and paved the way for the Quiet Revolution (Vezina and Basta, 2014). Williams consequently rode a wave of nationalist popularity, capturing 70 per cent of the vote and 44 of 48 seats in the House of Assembly (Feehan, 2011b: 52). Later the resource nationalist crusade continued as Williams led a bitter Anything But Conservative (ABC) campaign during the 2008 federal election. Williams registered the ABC campaign as a third party under Canada’s election laws, allowing him to purchase full-page newspaper ads and billboards in Ontario proclaiming Harper as a leader not to be trusted. Provincially, the Premier framed the federal Conservatives’ broken promise “as a betrayal of all Newfoundlanders and Labradorians” (Koop, 2014). While he did not achieve much success nationally the ABC initiative saw the federal Conservative Party lose all three of its seats in Newfoundland, slipping to third place in voter preference (Feehan, 2011b: 52).

30 Faced with an inability to reach another political settlement with Ottawa, Williams turned to maximizing the province’s revenues via an equity stake with industry on the development of the Hebron oil field, scheduled to produce oil in 2017. The vehicle through which Williams would achieve this would be a newly reconstituted Crown energy corporation, Nalcor. At the time, the consortium of companies involved in the project were in the process of constructing a Hibernia-like platform to extract the oil, which is heavier and harder to remove and refine than the oil from the other fields off the province. At one point, in 2006, the prospects of development were looking dim: the consortium had announced they were abandoning the project and claimed that once they had dismantled the development team it would take at least two years to restart the project. Premier Williams threatened to pursue fallow field legislation, which would up the stakes of the decision to postpone the development of the field. The companies would risk losing the right to develop a field if they did not develop it within a certain period of time. The main points of contention were the province’s demand for an equity stake in the project as well as the introduction of a super royalty level that would take effect when oil prices were exceptionally high (Sinclair, 2008). This was a move by the province to once again impose a Norwegian development model plus a variation of the generic royalty regime established earlier with Hibernia (see Harvie, 1994). Naturally, this was a model the oil companies vigorously resisted. However, the Chevron-led consortium negotiated from a point of weakness, given the already tight and declining supply of oil combined with an increasingly unstable investment climate elsewhere at the time. This combination of factors resulted in a development agreement in 2007 where the province seemingly got most of what it wanted. The Hebron agreement “had widespread support across the province given concerns over unemployment and underdevelopment” (Koop, 2014). As an aside, the Hebron negotiations would earn Williams the nickname “Danny Chavez” from the oil industry, aſter the populist authoritarian leader of Venezuela, Hugo Chavez, who had nationalized much of that country’s petroleum industry in the 2000s.

CONCLUSION

31 In reviewing the Peckford and Williams premierships it can be said that Newfoundland’s push for autonomy and control over oil resources was largely tempered by what Plourde (2012: 88) notes as the three factors that always impact Canadian oil development: geology, demographics (in politics), and constitutional provisions. Still, this did not stop either Peckford or Williams from trying. If we take Wilson’s (2010) four goals of resource nationalism as an example, it is clear from the Newfoundland experience that the most pertinent goal was to capture a greater share of the rents by demanding a stake in the exploitation, not outright nationalization. Arguably, this likely was due to the weak fiscal position in which the province found itself during the 1980s and again in the early 2000s. Owing to constitutional losses at both the federal and provincial supreme courts, Peckford eventually backtracked from outright control, as he had proposed during his tenure at the Department of Energy, settling on shared jurisdiction over offshore oil with Ottawa through the Atlantic Accord. It is also arguable that the years of delays generated through constitutional wrangling precipitated a desire in Peckford to reach a compromise in order to reduce jurisdictional uncertainty and initiate oil production.

32 The Accord, and the 2005 Offset Agreement negotiated by Williams, allowed the province to receive a portion of the rents Ottawa earned in each oil field, but with limitations: the federal willingness under both Liberal and Conservative governments to cede total revenue-generating power was clearly never going to be an option. Given such constitutional and political constraints, by the time the oil revenues started entering the provincial treasury in the 2000s the Williams government moved from increasing Newfoundland’s share of the rents via Ottawa to actually obtaining a financial stake offshore in the Hebron project. This latter point differentiates Williams from Peckford, who largely abandoned the goal of having a provincial stake in projects in favour of joint management. Williams, on the other hand, resurrected it, especially in establishing Nalcor, the Crown energy corporation. Nalcor, in many ways, is a revival of Peckford’s pre-Atlantic Accord establishment of the Newfoundland Petroleum Corporation (Plourde, 2012: 96, 106).

33 Two of Bremmer and Johnston’s (2009) four variants of resource nationalism are applicable to the Newfoundland oil case study. While these authors argue that Newfoundland would fall under the rubric of “soſt resource nationalism,” common in most developed countries, the province is also an example of a less extreme variant of “economic resource nationalism.” For instance, both Peckford and Williams took the “soſt” nationalist approach of appealing for a greater share of the rents through royalties, but Williams took an aggressive stand against the international consortium on the Hebron oil field, threatening to enact fallow field legislation should the province not obtain a stake in the project, as well a provision guaranteeing super royalties in the event of high oil prices. Peckford, in contrast, was concentrated on fighting the federal government over jurisdictional issues — he paid little attention to combating the oil industry. What the Newfoundland case potentially means is that resource nationalism in developed countries is more nuanced than originally thought.

34 Tellingly, as Vivoda would note, the province’s success in achieving its goals during the Hebron negotiations could not have happened without the high price of oil (roughly US$70 a barrel and climbing). Under pressure to develop more oil fields, the Chevron-led consortium had little choice but to accede to the province’s demands. Therefore, the Hebron negotiations illustrate the role that obsolescing bargaining has played in the history of Newfoundland’s oil development. As noted in the introduction, when oil prices were low in the late 1980s and early 1990s, at less than US$20 a barrel, the government of Premier Clyde Wells was stuck bargaining from a weak position with the oil consortium developing the Hibernia field. One of the major companies holding a 25 per cent stake in the project, Gulf Oil, backed out in 1992. Based on this event the remaining partners reduced expenditures and work on the project slowed as they searched for a new partner. In the end, the intervention of the federal government in combination with the “favourable provincial royalty regime” of the Wells government saved the project from complete collapse (Feehan, 2009: 178; Mulroney, 2007; Crosbie, 1997). Such a contrasting experience within a two-decade period highlights the cyclical nature found in the bargaining arguments made by Ross (2012), Vivoda (2009), and Bremmer and Johnston (2009). Moreover, Newfoundland’s experiences on bargaining from both weak and strong positions in such a short period of time also point to the volatility of the oil market and to how much favourable royalty agreements are due to global economic factors beyond the control of St. John’s. The drop in oil prices in late 2014 and early 2015 has further highlighted the vulnerabilities of relying on a resourceheavy economy, leaving the provincial government with a $916 million budget deficit (projected as of December 2014) and in a weakened bargaining position for negotiation royalties from future oil deposits, like those recently found in the Flemish Pass (Minister of Finance, 2014; CBC, 2014).

35 Finally, the impact of resource nationalism on Newfoundland’s oil development during the Peckford and Williams years illustrates the applicability of the theory to other resource issues and disputes. This applicability likely includes an analysis of the Peckford and Wells approaches to the fishing industry; Brian Tobin’s fight with Inco over mineral processing in the province; and Williams’s nationalization of Abitibi-Bowater’s hydro and factory assets in 2008. Likewise, the handling of the Churchill Falls (Upper and Lower) file dating back to the Smallwood years would provide a fascinating case study of how successive administrations adopted resource nationalist policies on managing this sensitive resource. Again, these topics point to the research potential that remains in analyzing resource nationalism in Newfoundland and to the merits that lie in researching an understudied case.

The authors would like to thank Louise Carbert, the editor, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.