Articles

E. Mary Schwall:

Traveller, Mission Volunteer, and Amateur Photographer

1 Eva Mary Schwall’s collection of photographs, captured during the summers of 1913 and 1915, is likely to be classified as a “shoebox collection.”1 The collection includes 135 amateur-quality, black-and-white images taken by (Eva) Mary Schwall (hereafter E. Mary Schwall).2 Schwall was a school principal in New Bedford, Massachusetts, who first travelled as a volunteer, at age 54, to the Grenfell Mission in St. Anthony in the (then) colony of Newfoundland (Annual Report of the School Committee of the City of New Bedford, 1886).3 While working as a volunteer at the Grenfell Mission, she maintained a photographic travelogue, one that could be regarded as both “realist” and “romantic” in its perspectives (Langford, 2001: 66). In addition to visually documenting the material conditions and circumstances of the Grenfell Mission at the time, Schwall’s photographic collection also provides a narrative account that engages in what scholar Martha Langford identifies as a “suspended conversation” about the Mission and its work (2001; Moors, 2006). This conversation, although partial and incomplete, is shaped by Schwall’s selective organization and presentation of her photographs, and by their brief textual captions that encourage the formation of perceptions about the places pictured, about Schwall herself, and about the Mission to which she travelled (Langford, 2001: 24). Until now, the collection has been considered in relation to its circuitous acquisition, from its custodians on the west coast of the United States to an archive on the east coast of Canada, previously the Centre for Newfoundland Studies Archives and now Archives and Special Collections, Queen Elizabeth II Library, at Memorial University of Newfoundland (Gzowski, 1994; Labrador City Ad-Hoc Committee, 2004; White, 2004).4 It has not yet been considered for its historical and social significance, or for its contributions to conversations about volunteers at the Grenfell Mission, many of whom were women; it also has not yet been considered in relation to the production of photographic collections and their location in a larger body of textual and visual travelogues, autobiographies, and memoirs intended to initiate narrative constructions of the Mission, its work, and its workers.

2 In this article, I analyze Schwall’s photographic collection as a cultural artifact.5 I elucidate the content and form of the photographs in mainly descriptive ways, paying close attention to subjects; to the particular ways subjects are framed; to the composition; and to the frequency, repetition, and “distribution of particular poses and landscapes” across the collection (Jenkins, 2003: 312; Margolis, 1988). This visual methodology places importance on photographs as visual and material artifacts intended for viewing. As Lorna Malmsheimer (1985: 54) argues, photographs constitute:

3 Even when photographs are removed from the contexts in which they were created, Martha Langford suggests they establish conversations, or what Gillian Rose in her photographic critique refers to as “relations” between images and their audiences (Langford, 2001; Rose, 1997: 227; 2011). I draw on Schwall’s photographic collection as a primary source to consider its contributions towards polyvalent relations, conversations, and narrative accounts of the Grenfell Mission, noting their simultaneous construction in print materials used to promote tourism in Newfoundland and historical analyses of Newfoundland, Labrador, and the Grenfell Mission specifically. I argue that E. Mary Schwall’s collection visually represents the subjects and spaces of the Mission as a “spatial exotica,” one that emphasizes myths about place and that possesses, if only temporarily, its social and cultural world (Jenkins, 2003: 314; Malmsheimer, 1985).

4 Representation of this “spatial exotica” serves multiple purposes. It serves as a useful tool for drawing a cadre of volunteers, Schwall among them, to geographic and cultural locales from which they could construct and assure their differences from local residents. It provides a rationale for narratives about travel based in benevolent labour instead of tourism; and, importantly, it provides a justification for the Mission’s existence at this particular time and in this particular locale.

5 The Mission to which Schwall travelled was established to provide medical care to migratory deep-sea fishermen and to local populations residing on Newfoundland’s Northern Peninsula and along the Labrador coast (Rompkey, 2011). British medical doctor, Wilfred Thomason Grenfell (1865–1940), who later became the Mission’s superintendent, first visited the area in 1892 to provide medical assistance. Upon his return in 1893, he worked towards the Mission’s further establishment and initiated a range of medical services and non-medical activities intended to promote self-sufficiency for migratory and permanent coastal residents. These endeavours were largely dependent on a volunteer labour force (Rompkey, 2011). Grenfell’s efforts were also based in a religious mandate centred in “muscular” Christianity and in his acceptance of the imposition of imperial order (Ryan and Schwartz, 2006: 5). During the late Victorian period, muscular Christianity emphasized evangelicalism alongside the “manly virtues” of physicality, patriotism, and self-reliance (Bloomfield, 1994: 172; Hulan, 1997). Renée Hulan argues that muscular Christianity, which combined “discourse[s] of medicine, gender, class and religion,” was used as a means by which to erase social differences, required in instances of “colonial expansion” (1997: 183). Grenfell worked concertedly to maintain a positive, public impression of the Mission and its expansion, in text and image. Positive depictions of the Mission were central for its work, as well as for the retention of its international supporters who contributed towards its maintenance in cash and in-kind donations, and with their labour.

6 E. Mary Schwall’s photographic collection, which contributes towards this intentionally positive impression, has multiple meanings, depending on its viewers (Rose, 1997: 227). Her collection likely constitutes an aide-mémoire, a personal reminder of Schwall’s travels and her two summers spent at the Grenfell Mission (Schwartz, 1996: 26; Coombs-Thorne, 2010). It is plausible that the temporally ordered photographs documenting her travel and her stay at the Mission were used, as Langford suggests, as visual aids for storytelling (2001). Perhaps this conversation served to recollect memories; and perhaps it served to solidify impressions about Schwall and her life. Photographs, Marilyn Motz argues, provided a means by which women could document their independence outside of marriage and family (1989: 64). At the turn of the century, the photographic album provided independent American women with a medium through which they could construct their lives as they saw them, and as they wished to have them seen by others (Motz,1989: 63). Its purpose as an aide-mémoire, however, would have been restricted temporally. Upon Schwall’s death in 1946, her collection would not have continued to serve this same purpose for its custodians or for those viewing her photographs today. Justin Carville argues that, once archived, photographs no longer function as an aide-mémoire; instead, they function as “a historical document of how an individual and a society once remembered through the photographic image” (2009: 92). Because of the passage of time, this photograph collection, which is associated with Schwall in its location in the contemporary archive, also is distanced from her and from her memories.

7 The collection furnishes photographic evidence of vernacular Mission buildings and of individuals connected with the Mission. Schwall’s photographs depict and name specific Mission buildings and structures, and illustrate their purposes, such as the hospital and its adjacent tuberculosis tents, and the Children’s Home. Images of buildings contrast the built landscape of the Mission with the natural landscape surrounding it and provide a tangible rationale for the Mission’s existence. The buildings furnish evidence of Grenfell’s presence in the (then) British colony of Newfoundland. Mission buildings, many of which have facades inscribed with Biblical quotations, also associate individuals with the Mission’s religious intentions and visually articulate Grenfell’s missionary purpose.

8 For some viewers, the collection provides a “pictorial codification” of daily life in select communities across Newfoundland and Labrador (Carville, 2011: 51). The collection is one of the ways through which an “imaginative geography” of place is created, a term first coined by David Harvey to refer to “an overarching appreciation of the significance of place, space and landscape in the making and meaning of social and cultural life” (Harvey, 1990, in Ryan and Schwartz, 2006: 6). As an assemblage of select images, Schwall’s photographs create shared meanings about place, and establish their differences from other places. For example, Schwall’s carefully crafted portrayal consciously focuses on the natural environment and landscape, depicting the challenges and opportunities they present for adventure, including her own. These depictions are also repeated in tourist literature and images, creating what Olivia Jenkins refers to as a “circle of representation” in visual images (2003: 308). Located in this existing body of promotional text and images, Schwall’s collection shapes and reinforces viewers’ knowledge of geographic spaces, and informs their “cultural and political imaginings of place” and its inhabitants (Carville, 2011: 15). Schwall’s images justify the presence of the Mission and its benefits for annual migrants and community residents who accessed it (O’Brien, 1992). They provide evidence of Schwall’s association — as an observer, a participant, and a communicant — with the Mission and its purposes. On one hand, the collection illustrates what the Mission accomplished, in terms of the provision of its services and activities geared towards self-sufficiency; on the other hand, it manufactures its continuous need, in terms of the Mission’s perpetual requirements for donated goods, including medical supplies, clothing and food, and voluntary labour. Schwall’s collection extends the range of observable spaces, making a wider range of places and conversations accessible to travellers and viewers (Ryan and Schwartz, 2006: 2).

9 Schwall’s collection is among the earliest, dated, photograph collections compiled by a Mission volunteer.6 A substantial body of scholarly work examines the perspectives of Mission staff as they have been recounted by nurses and/ or doctors (Perry, 1997; Bulgin, 2001; Laverty, 2005; Rompkey, 2009; Rutherford, 2010; Greely, 2010 [1920]; Coombs-Thorne, 2010, 2013; Lombard, 2014).7 However, fewer accounts have been recorded from the perspectives of Mission volunteers and/or staff members’ families, as those roles often were conflated. These perspectives are reflected in Schwall’s collection, which compiles her experiences as traveller, mission volunteer, and amateur photographer.

SCHWALL AS TRAVELLER

10 Wilfred Grenfell, founder and superintendent of the Mission, and Mission staff in its satellite locations recruited volunteers from the United States and Great Britain for various Mission roles (Coombs-Thorne, 2010). E. Mary Schwall travelled to St. Anthony, Newfoundland, via Nova Scotia, from her hometown in New Bedford, Bristol County, Massachusetts.8 Although Schwall likely was recruited while she lived in the United States, she may already have known something about Nova Scotia; her mother, Eleanor (Ellen) (McNutt) Schwall, was born in Onslow, Colchester County, Nova Scotia, in 1827 and later moved to Massachusetts.9

11 Written records show that E. Mary Schwall travelled to the Mission in St. Anthony in the company of her younger sister, Sarah (Sally) (1864–1940) (Rompkey, 2001; Laverty, 2005). The practice of travel companionship for women was recommended by Emma E. White, secretary-treasurer in the Grenfell Mission’s Boston office, and was likely to have been “based on the popular belief that ladies disliked or feared travelling alone” (Rompkey, 2001: 10).10

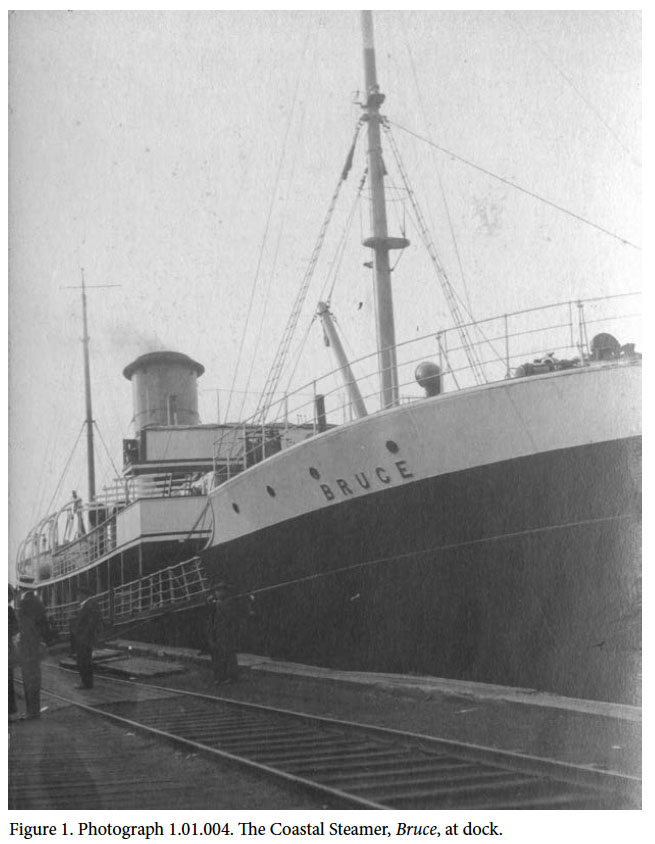

12 Their travel, which involved transport by train, ship, and schooner, is documented in Schwall’s photograph collection and in her brief, written notations.11 The brevity of the notations suggests they were intended primarily for the purposes of personal recollection and narration (Motz, 1989: 67; Langford, 2001). Schwall’s written notations identify the names of ships and schooners. For example, Figure 1 is labelled “The Coastal Steamer, Bruce, at dock,” but it provides no further information about the places that its passage connected. Her notations also identify (at times incorrectly) the names of the communities that she sailed past or, in some instances, visited. The way Schwall captures and captions photographs of communities — naming one, then another, and then another — reflects the episodic character of the journey and prompts viewers to perceive the geography and landscape of Newfoundland as fragmented and disconnected. It does not illustrate, for instance, some of the ways that communities are connected to one another through families, shared resources, or around geography, such as a bay. Presumably, her narrative may have bridged these disconnections, until such time when it was no longer available to accompany the photographs. At the same time, the organization of these photographs affirms that travel across Newfoundland could be readily accommodated, even if it was along well-travelled and predictable routes facilitated by coastal steamers carrying supplies, mail, and tourists (Albers and Williams, 1988; Larsen, 2005). The modes of transportation on which Schwall travelled to and from the Mission were shared by many others, including other visitors from the United States. In 1913, there were 4,072 recorded tourist visits to Newfoundland (Pocius, 1994: 69). Tourist passage was provided between New York and Newfoundland and tickets issued in Boston by Plant Line Steamers were advertised in the Newfoundland Quarterly (1913).

13 Many of Schwall’s images depict an unspoiled natural landscape that was already promulgated widely, in text and image, in tourist materials and in books, magazine articles, and pamphlets (Williams, 1980; Legge, 2007). Their primary purpose was to attract American visitors to Newfoundland and Labrador to bolster the area’s economic base by offering the landscape as a direct and accessible challenge for travellers and adventurers (Pocius, 1994). A pamphlet produced by the Reid Newfoundland Company in 1912 claimed that “Newfoundland and Labrador are no longer unknown lands” and that “railways and steamers afford easy access to all parts of Newfoundland and Labrador” (Reid Newfoundland Company, 1912: 5).12 Claims such as this one simultaneously produced and contradicted ideas about the area’s geographical remoteness.

14 Schwall’s photographs also provide some idea about the opportunities available to women with the financial means and leisure for travel. In her examination of women’s travel and photographic records on Canada’s west coast, Colleen Skidmore (2006: xxiv) observes that:

Schwall’s temporary departure from her familiar surroundings, the novelty of the geographical locale, and the change from her daily activities likely framed her excursion, and her visual, textual, and oral narration of it, as an adventure apart from her everyday life.

SCHWALL AS MISSION VOLUNTEER

15 The work that E. Mary Schwall and her sister Sally undertook as Mission volunteers remains unclear. Some volunteers used their time at the Mission to take up new experiences, while others offered their already acquired professional expertise in nursing and medicine. Laverty (2005: 169) states:

Jessie Luther was an American artist and occupational therapist who, having previously worked in Chicago at Hull House, the widely known settlement house for immigrants, was recruited by Wilfred Grenfell to work at the Mission (Rompkey, 2007: 56). Alice (Appleton) Blackburn taught at the Mission’s school from 1911 until 1913 (Rompkey, 2001: 326). The role of travelling assistants to Luther seems unlikely because she had already left the Mission by 1915, as her own comments below, indicate. The Guest House received visitors to the Mission, many of whom were its supporters, and the Mission made extensive use of summer teachers in the Children’s Home (Laverty, 2005).13 It seems more likely that E. Mary Schwall, a school principal at the Dartmouth Street Primary School in New Bedford, Massachusetts, who had completed two years of college level education, “served as a teacher” and that her younger sister, Sally Schwall, a bookkeeper whose formal education had finished at high school, may have been a housekeeper at the Mission Guest House (New Bedford Annual Report, 1897, 1899).14

16 Another account, recorded by Jessie Luther, suggests different roles for the two women:

The Loom Room provided a centralized location for weaving, an activity that formed part of Grenfell’s Industries (also referred to as the Industrial), which was focused on the commercial production and sale of handicrafts, among them, hooked floor mats for which the Industrial became well known (Laverty, 2005).

17 A further account in the July 1915 issue of the quarterly publication, Among the Deep Sea Fishers, lists “the Misses Schwalls” as “traveling assistants, 1915, volunteer” in the Industrial Department (International Grenfell Association, 1915: 84).15 As Schwall’s collection contains photographs of children, likely enrolled in the Mission’s summer school, and of the Guest House and the Loom Room, it offers no further clarity regarding their specific roles.

18 Mary Schwall’s brief, summer sojourns as a volunteer worker were situated within a gendered labour force, and her responsibilities, whether they were in the schoolhouse, the Guest House, or the Loom Room, were consistent with the roles normally assumed by women at the Mission. In the absence of volunteers, these roles were assigned occasionally to staff nurses as a part of their non-medical responsibilities at the Mission (Perry, 1997: 88; Coombs-Thorne, 2013).

SCHWALL AS AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER

19 Mary Schwall’s efforts to visually document her surroundings situate her among a significant cohort of individuals who, beginning in the early twentieth century, took up amateur photography as a popular pastime (Oliver, 2007). Cameras were marketed, beginning in summer 1888, for purchase by amateur photographers. Their relative portability, moderate cost, and accessibility of purchase in department and drug stores increased their appeal and use (Margolis and Rowe, 2004: 212; Gregory, 2006: 210). Schwall’s photographs were captured with a Kodak 3A folding camera (Todd Gustavson, personal communication, 23 July 2014). Manufactured between 1903 and 1941, it was one of seven varieties of the folding camera.16 The Kodak 3A folding camera used 122-size roll film, and processing was widely available. In this particular model, the lens folded back into its box construction, and the camera was advertised as able to fit into a coat or vest pocket. It was not just the camera and its popularity that led to the use of “Kodak” as a verb; its popularity was furthered by Kodak signs and advertising that populated the landscape, including in St. John’s, Newfoundland — the site of a Kodak export franchise (Ryan and Schwartz, 2006; Sexty, 2014; Geoff Tooton, personal communication, 4 July 2014). Intended to link the pastimes of travel and photography, advertising for this particular model boasted postcard size images.17 The combined availability of the camera, film, and processing initially encouraged amateur photographers to capture outdoor surroundings; eventually, technological advances in shutter speed and lighting expanded their capacity to include indoor photographs (Gover, 1998).

20 Cameras were intentionally marketed to women, as personified in the visual advertising image of “the Kodak girl,” and promoted by Kodak’s advertising slogan, “you press the button, we do the rest” (Gover, 1998: 2; West, 2000). This implied ease of use for women, who may have expressed hesitations about its technological requirements, also reinforced dominant gendered stereotypes but equalized the use of the camera for women and men (Oudshoorn, Saetman, and Lie, 2002; Pedersen and Phemister, 1985).

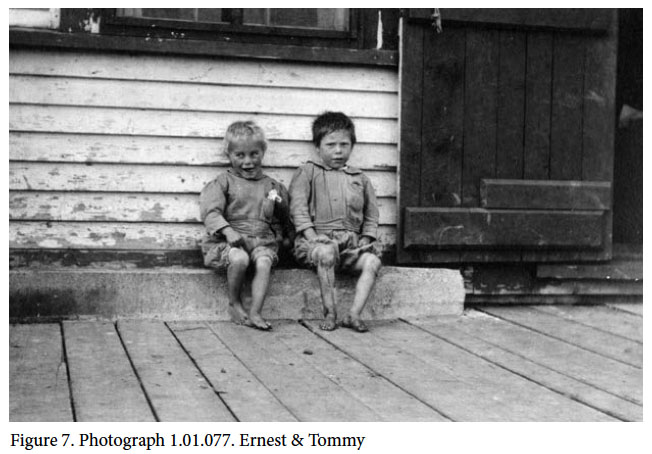

21 Schwall’s photograph collection enjoyed some “visual economy,” a term conceptualized by Deborah Poole (1997) to refer to the flow of images across spatial, temporal, and geographic boundaries. The condition of photographs in the collection indicates that they were not placed in albums, as would have been the fashion; however, this alone does not preclude their shared distribution and narrative functions (Motz, 1989). They may have been exchanged or passed to admirers and acquaintances. At least one of Schwall’s photographs (see Figure 7) was reprinted in the January 1915 issue of the Mission’s quarterly magazine, Among the Deep Sea Fishers, but without attribution to Schwall. In this way, her photograph inhabited public spaces through the magazine’s international circulation to Mission supporters. By 1914, Among the Deep Sea Fishers had a circulation of approximately 7,500 copies (Connor and Coombs-Thorne, 2014).

CONSTRUCTING IMAGES OF IMAGINED SPACE AND PLACE

22 Ordered and numbered sequentially, Schwall’s photographs trace her travel from “Mulgrave, Nova Scotia,” then across to “Channel [Newfoundland],” onto “St. John’s — and a trip from St. John’s north around the coast to St. Anthony, across the Strait of Belle Isle — to Labrador and back down the west coast of the Great Northern Peninsula” (Riggs, 1996).

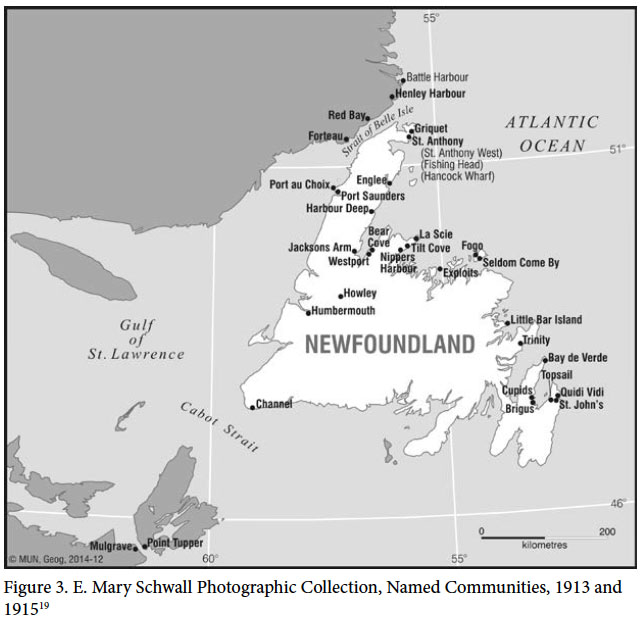

23 The collection pictures and names 34 communities in Newfoundland and Labrador (Figure 3).18 In Figure 2, a photograph likely taken from the water, modestly built houses are scattered along the shoreline, many of them fronted by fishing stores and flakes. The image depicts the area’s dependency on fishing, and highlights the remoteness of the landscape, as does the name recorded for this particular community, Seldom Come By, Newfoundland. Their identification reinforces perceptions about the area’s geographical remoteness, and at the same time, affirms the necessity of the Mission’s presence in the landscape (Larsen, 2005).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

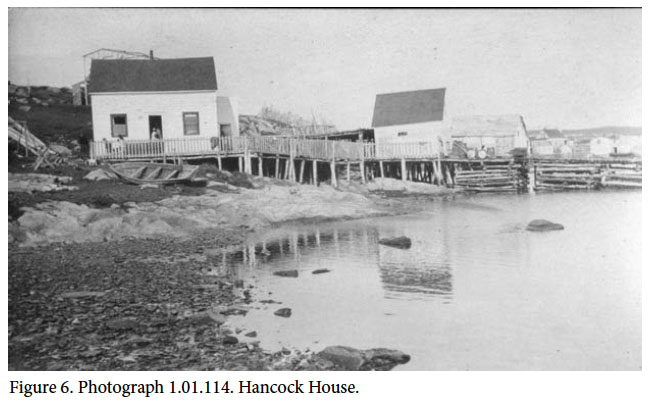

24 The number of communities that Schwall photographed implies a vast geography, but closer examination suggests that it was not necessarily one that she traversed. Many of the photographs appear to have been taken from aboard coastal steamers; Schwall may only have sailed past these communities. In many instances, there is only a single image of the named community. In the case of some communities, such as the town of Brigus, her photographs are confined to areas in close proximity to docks and wharves, suggesting that her visit ashore was brief.20

25 The greatest number of images taken in a single location, apart from the Grenfell Mission itself, is a set of 19 images of the urban centre of St. John’s and the nearby (then) fishing village of Quidi Vidi. Comprised mainly of streetscapes and landscapes, the content of these images closely resembles the commercial postcards available for purchase at the time, including those purchased and collected by Schwall. By capturing images already similar to those that existed, Schwall’s collection participates in the co-production of their visual significance as spaces worthy of attention and worthy of narrative engagement (Larsen, 2005: 422). Her images can also be read in ways that are supportive of the Mission’s purposes, even when physically distanced from the Mission. For example, Schwall’s images in Quidi Vidi picture the village’s fishing flakes and wharves, thereby reaffirming Grenfell’s view, to which Schwall may already have been introduced, about the detrimental effects of the area’s economic reliance solely on fishing as a cause of local impoverishment and poor health.

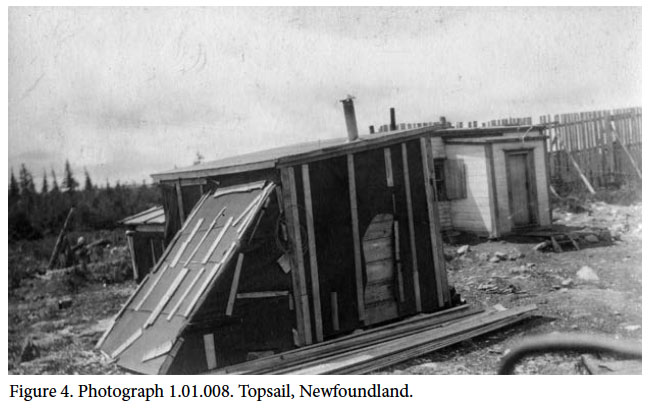

26 The theme of impoverishment recurs in the generally poor condition of some buildings, and is noted in Schwall’s classification of them as “shanties,” as shown in Figure 4, photographed in Topsail, Newfoundland. Indeed, by the early 1900s, the poor quality of housing and its implications for ill health, particularly among the working poor of St. John’s, already were the concerns of a local civic reform committee; furthermore, the benefits of the “laws of ventilation” for physical health were being expounded in print (Tait, 1913: 6; Baker, 1982).

27 Beyond St. John’s and Quidi Vidi, Schwall’s photographs are inscribed with the names of specific communities, and in some instances her subjects tend towards distant buildings, stretched horizons, and their watery foregrounds (Pocius, 1994; Jenkins, 2003). Their composition conveys long stretches of travel aboard ships and schooners. As their sometimes incorrect names suggest, Schwall may not always have been aware of what she was seeing or may not have been cognizant of features that distinguished communities from one another. This part of the collection suggests that Schwall may have been engaged in what Jeremy Foster refers to as “observing without looking,” as a way of projecting her own subjectivities and expectations onto a place (2006: 143). Collectively, her photographs affirm Newfoundland’s location as a scenic, yet undiscovered, frontier — one that Gerald Pocius (1994: 54) suggests existed closer to its “natural” state than might have been the case for communities at that time in the already industrialized northeastern United States. The photographs contrast the everyday life and work of Newfoundlanders with Schwall’s travel as leisure, and with her voluntary labour.They construct and affirm differences between the place from which Schwall travelled and the Mission as her destination.

28 This sparsely inhabited landscape is reinforced by the fact that Schwall chose to include relatively few human subjects in these photographs, confirming the impression that was often given in promotional brochures — that few Newfoundlanders actually lived in the colony (Pocius, 1994: 60). Those subjects who were included in Schwall’s photographs taken en route to the Mission tend to be boys and men, many of whom are engaged in work-related activities. It would appear that Schwall had relatively little access to domestic spaces in Newfoundland communities as she travelled to and from the Mission; or, if she did, that she chose not to photograph them, perhaps aware of the likelihood of their poorer image quality.

29 Many of these images are spontaneous rather than posed. Their subjects are actively engaged in work, such as a man accompanying a barrel-laden cart in St. John’s, a man sitting on a horse-drawn cart partially immersed in the water in Brigus, boys loading fish into a wheelbarrow in Cupids, and men gathered on a wharf in Westport.21 The subjects do not face the camera, and make no eye contact with the photographer. The images are not framed or cropped in any way so as to place their subjects in the centre of the frame. In some instances, their backs are to the photographer, suggesting, instead, that they form part of the landscape (Larsen, 2005). By photographing them in this way, Schwall may have endeavoured to minimize her intrusion on the landscape; or, as these poses suggest, she may have been more interested in picturing her surroundings than in the subjects themselves (Roy, 2005).

30 Perhaps surprisingly for this time period, few photographs in the collection locate places and their residents in the dramatic events and political resonances affecting Newfoundland and Labrador. By Schwall’s second visit, during the summer of 1915, the presence of World War I activities in Newfoundland would have been notable, including the presence of a training camp at Pleasantville in Quidi Vidi and a unit of the Legion of Frontiersmen in St. Anthony (O’Brien, 2007). There is little indication of these activities in Schwall’s collection, although their accessibility may also have been limited by expectations about the public censure of war-related activities.22

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

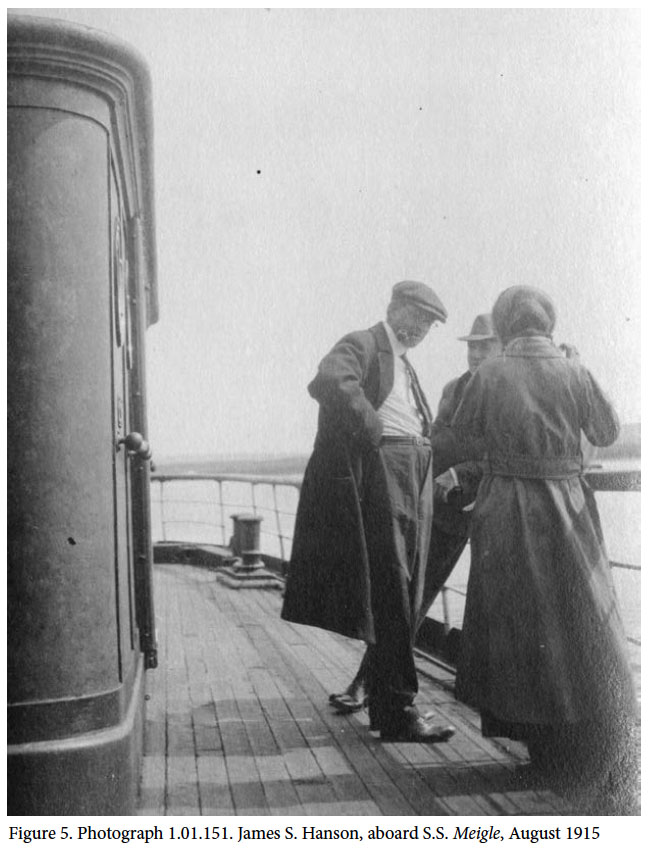

31 The single exception in the collection is a photograph of the alleged German spy, Mr. James S. Hanson (Figure 5). This photograph and Schwall’s textual identification of its subject suggest that she had some knowledge, prior to taking this photograph, of Hanson’s arrest and the ensuing public controversy. Captured aboard the S.S. Meigle in August 1915, the composition of the photograph suggests a chance encounter rather than a personal acquaintance (Western Star, 1915). In the photograph, Hanson, a British subject born in Scotland, stands at the ship’s rail; aware that he is being photographed, he looks away from his travelling companions and glances down towards Schwall’s camera lens. His glance lends an impression of brief temporality to the encounter.

32 Local newspapers in St. John’s and Curling reported that Hanson was arrested in Labrador, where he was reportedly on fur-buying business; his “slight accent” and his presence in Battle Harbour, Labrador, raised suspicion (Daily Star, 1915; Western Star, 1915; Bassler 1988). Hanson was transported to St. John’s where he was required to account for his presence and was expelled.23 Later, Hanson demanded an investigation into his treatment; however, none was conducted (Bassler, 1988: 62).

CONSTRUCTING IMAGES OF PLACE AND PURPOSE

33 Schwall’s photographs taken at the Mission provide a firmer sense of familiarity with place and infer more intimate relations with its residents. Her collection includes photographs of the landscape surrounding the Mission, buildings associated with the Mission and its work, and people associated with the Mission, including residents, volunteers, and Mission staff (Ryan and Schwartz, 2006). Although advances in flash photography would have permitted indoor images, Schwall’s images are captured, almost exclusively, outdoors.24 Through her photographs, Schwall orders the vast geographical space, along rocky coast and shorelines, that figures prominently in the landscape. One way of understanding the significance of this landscape may be to see it as a necessary frame for the Mission — its physical location, and its focus as a medical mission with an intentional emphasis on self-reliance.

34 Schwall’s collection includes photographs of various Mission buildings, which demonstrate their purposes and their beneficiaries. A photograph of a modestly built, wooden building, the Stop-Cash Cooperative Co. Ltd in St. Anthony, records Grenfell’s efforts to undermine the subjugation of local fishers through merchant exploitation in the credit system (Rompkey, 2007).25 Co-operative stores were intended to provide affordable purchases to local residents through “better terms for cash deals and bulk purchases” (Hiller, 1994b: 28). Situated in their architectural isolation, the painted and generally well-maintained Mission buildings, many of them with curtained windows, pathways, porches, and fences, are juxtaposed against a rugged landscape. Photographs of buildings in St. Anthony include the Guest House, the Children’s Home, and the hospital, as well as canvas tuberculosis tents located separately in the hospital yard.26 The Children’s Home, also referred to as “the Orphanage,” was a wooden building capable of accommodating approximately 20 children. In 1922, a brick building was constructed to replace it (O’Brien, 1992; Rompkey, 2011). The building’s facade is adorned with the text “Suffer Little Children Come Unto Me” in large, upper-case letters, and is intended to be visible from a distance. Similarly, the hospital in St. Anthony is adorned with a religious text that reads, “Faith Hope and Love Abide But the Greatest of These is Love,” although this text is only partially visible in Schwall’s photograph.27 The hospital’s outdoor porches, built on two levels and furnished with benches and chairs, and the yard’s scattered tents on wooden platforms demonstrate the open-air treatment for tuberculosis (Knowling, 1996). Treatment of tuberculosis at this time, William Knowling argues, was subjected to “broad ideologies of modernization” and social agendas, including “work therapy” (1996: 26–28). Because of Schwall’s tendency to centre buildings in the frame, her collection does not provide a sense of the layout and scale of the Mission, the proximity of buildings relative to one another, or the proximity of St. Anthony to other locations where the Mission’s work was also carried out, including numerous nursing stations.28

35 A few photographs, including Figure 6, are of residents’ houses. The Hancockhouse accommodated the family’s eight children, one of whom, Ned, had his education in the United States provided by the Mission (Rompkey, 2001; Laverty, 2005).29 Schwall also photographed the houses of Mission staff, and in her captions she associates houses with the names of the Mission staff who resided in them.30 They include three American physicians: Dr. John Pendleton Scully, accompanied at the Mission by Mary Elizabeth (Betty) (Chase) Scully, who worked alongside her husband; Dr. John Mason Little, who resided at the Mission from 1907 until 1917; and Dr. John Grieve, who resided at the Mission from 1906 until 1916 and who, during a 15-month stay at the Harrington Hospital, also assumed the role of Indian agent (Rompkey, 2011; Heritage Newfoundland, n.d.). Schwall’s collection includes a photograph of the staff house of nursing sister Florence Bailey at Forteau, Labrador. A British-born nurse, Bailey is credited with providing obstetrical care in Labrador (Rompkey, 2001: 305). All of these individuals are named in written accounts of the Mission and its work (Greely, 2010 [1920]; Laverty, 2005). These photographs of houses represent domestic spaces and Schwall’s familiarity with them, and perhaps, with the individuals who resided within them. Staff houses at the Mission served the dual purpose of sheltering staff and their families and of providing local residents with appropriate models of industriousness and cleanliness, tidy exteriors, tended summer gardens, and fenced dogs. Written accounts corroborate the importance of these ideals to the Mission. Mission nurse Laura Harrington suggests that “tourists’ praise of neatly kept homes . . . and gardens stimulated further improvements” among local residents (Perry, 1997: 159). Schwall’s photographs of staff houses serve, thus, as further examples of standards for everyday living reinforced by the Mission.

36 During her time at the Mission, Schwall also photographed children, replicating a pattern on the pages of Among the Deep Sea Fishers that “especially emphasized children” (Connor and Coombs-Thorne, 2014: 33). In these photographs, children are the intentional subjects.

37 As far as can be identified, only one of Schwall’s photographs (Figure 7) appeared in the Mission’s print magazine. A photograph of two young boys, identified as Ernest and Tommy, was published in the January 1915 issue of Among the Deep Sea Fishers (1915: 153). These two young boys are identified in earlier and in subsequent issues specifically in relation to the improvements made to their health (Grenfell Association, 1913: 33; International Grenfell Association, 1916: 51). At this time, the publication did not normally credit photographers; however, Schwall is referred to indirectly. The accompanying texts states, “This picture of little Tommy and Ernest was caught while they were making mud pies and the artist did not allow for them to be scrubbed” (International Grenfell Association, 1915: 153). The caption offers an apology for Schwall’s spontaneity in capturing the image, one in which two thin boys appear dirty and barefoot, contrary to the Mission’s (and its supporters’) emphasis on diet, cleanliness, and hygiene (Perry, 1997: 143). The explanation that accompanies the photograph assures subscribers that the boys, who were in the midst of play, would normally have been scrubbed and well-attired, as expected by those who made regular donations of clothing to the Mission.31

38 Tommy (on the right) appears to be the “bright, five-year old boy” who is mentioned in Grenfell’s “Log,” a regular column printed in the Mission’s publication, Among the Deep Sea Fishers, and also in a feature article about the Children’s Home in a 1913 issue. Grenfell states that prior to his arrival at the Mission, “Tommy was fed only oatmeal and butter,” implying the family’s impoverishment and offering an explanation for his diminutive size (Grenfell Association, 1913: 7, 8). Tommy is characterized as “a very obedient child who gives no practical trouble” (1913: 33). In the same column, Ernest, aged three (on the left), is described as having been removed from “a desolate home” with the Mission as “his only hope”; he is identified, by way of a Biblical reference, as “Tommy’s shadow: he follows him everywhere and echoes his words as if they were words of wisdom far above rubies” (Grenfell Association, 1913: 33). The inclusion of the photograph, its caption, and further information about its subjects combine to provide a rationale for the Mission’s continued support; through the reproduction of her photograph Schwall is embedded in this plea.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

39 Another photograph (Figure 8) taken by Schwall closely reproduces the composition of school photography. Eleven children are positioned in rows in front of a wooden building, likely the Children’s Home. Ernest and Tommy sit side by side, dressed in identical outfits, at the centre of this image. The children are posed in three rows, bookended between two adults. This pose was likely a familiar one to Schwall as a school principal, and it invites viewers to recall their own places in this contrived composition (Mitchell and Weber, 2005). Likely to be an image of some of the schoolchildren who populated the Mission, it can also be read as an indirect plea for support for children’s education at the Mission. There is some informality; some of the children are sitting, while others are standing, and their posture is not rigidly controlled. The setting is outdoors, and some of the children squint, either into the sun or into Schwall’s camera lens. The children who direct their view downward and away from the camera are a reminder that the subject’s consent to be photographed can be granted temporarily or even fleetingly (Mitchell and Weber, 2005). The two adult women who accompany the children are distinguished by their stature and dress. They are not Schwall’s intended subjects, as indicated by the fact that their heads are outside of the frame. On the one hand, these two adult women are distinguished by their place in the photograph and by their dress; on the other hand, they share a spatial proximity with the children, one that suggests a “common humanity” approach to the Mission’s work, perhaps a key for establishing religious affinity (Eves, 2006: 725).

40 All of the children are attired in gender-specific clothing, either in dresses with pinafores or in outfits with short pants. They are not dressed uniformly, as is the case in photograph collections from some other residential settings (Malmsheimer, 1985; Margolis and Rowe, 2004; Warley, 2009). A notable feature is the children’s short hair, although this, too, is not uniform. Haircutting is noted by Lorna Malmsheimer in her visual analysis of photographs taken at the Indian Industrial Training School, also known as the Carlisle Indian School, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, as an overt symbol of cultural assimilation (1985). It may serve that purpose here; or it may also be a practical means to address the spread of head lice. Malmsheimer argues the photographic session was an initiation ritual “into civilization” (1985: 57). It seems more likely that Schwall’s photograph is arranged purposively to illustrate Mission narratives about its ability to provide for and educate children, including those who would otherwise be cared for in ways characterized by Mission staff as inappropriate or dangerously substandard.

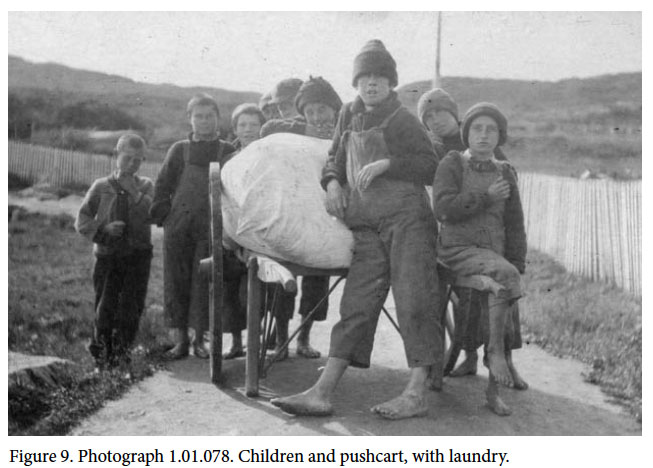

41 In another photograph (Figure 9), Schwall captures an image of nine boys, all of them dressed in work attire and posed around a pushcart loaded with a bag of laundry.32 In this photograph, the boys are wearing shirts, overalls, and hats — but not shoes. Their clothing is an important marker of their desired role as workers, and visibly demonstrates the in-kind support received (Eves, 2006). Patricia O’Brien (1992: 38) notes that used and donated clothing was kept in the Mission’s clothing stores, and that it was often dispensed, sometimes by Grenfell himself, as a form of payment in exchange for labour, or in exchange for the production of saleable handicrafts.

42 This photograph reinforces the centrality of work for subsistence in Newfoundland, and for the Mission’s ideals. Its activities promoted “industrial development,” and imparted the values of self-reliance and financial responsibility (Higgins, 2008). Indeed, the importance of work for people in Newfoundland and Labrador was emphasized by Schwall’s volunteerism. This theme was also reiterated in an article titled “Industrial Work in Northern Newfoundland and Labrador” (1916: 3). Authored by E. Mary Schwall, it was published in a 1916 issue of Among the Deep Sea Fishers.33

Marianne Gullestad argues that, in relation to Norwegian mission photographs, residents — and children in particular — were subjected to a convention of missionary rhetoric that affirmed their continuous material needs and demonstrated visually how donations and monetary contributions successfully met those needs (Geary, 1990). In this photograph, and in other photographs of children captured by Schwall, viewers can affirm the Mission’s benevolence as necessary, positioning the subject as in abject need.34

43 Apart from the photograph of Ernest and Tommy, there are few photographs in the collection of children at leisure. This situation suggests that Schwall had few opportunities to observe their leisure or that the Mission sought to structure children’s play and leisure, or both. Five years after the photograph of the boys and the pushcart was taken, Floretta Elmore Greely, in Work and Play at the Grenfell Mission, noted that Mission staff took on the work of organizing boys’ leisure time.35 The Boy Scouts Club underpinned the Mission’s colonial activities by reportedly offering them “some occupation other than spitting and throwing stones at birds,” and providing them instead with occasions for swimming lessons, learning the history of the Union Flag, talks on courtesy and chivalry, and instruction in first aid and public health (Greeley, 2010 [1920]: 40, 115, 123, 128).36

44 The Mission’s dominant visual rhetoric, which also included magic lantern slides used to accompany Grenfell’s speaking engagements, attracted the attention of some of the colony’s officials and church leaders. Concerns about Grenfell’s portrayal of Newfoundlanders, and the risks that these visual conventions posed for commercial interests and for “local dignity and pride,” were raised by “merchants, traders and ecclesiastics” (O’Brien, 1992: 16). Michael Francis Howley, Roman Catholic Archbishop in St. John’s, expressed his concerns publicly as early as 1905. In a letter to the Daily News, he suggests Grenfell’s pictures were “taken from the lowest and poorest of our people’s homes” (O’Brien, 1992: 21; Crosbie, 2014). Similar concerns were expressed about Grenfell’s “exaggerated, condescending lecture circuit portrayals of a backward society mired in poverty and disease” (Hiller,1994a: 128; 1994b). In 1917, Newfoundland magistrate Robert T. Squarey was tasked with leading an inquiry into the Grenfell Mission for a host of reasons, including “its degrading representation of Newfoundlanders as paupers,” and its alleged misrepresentations of Newfoundland and Labrador abroad (Hiller, 1994a; Rompkey, 2009: 194). Grenfell countered that the plight of individuals at the Mission was instead dramatized by the press, and in November 1917 the Grenfell Inquiry exonerated the Mission of the specific allegations against it (Hiller, 1994a).

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10

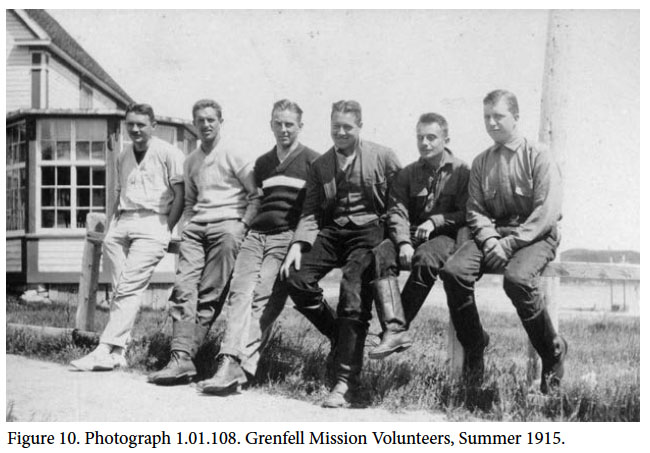

45 Looking considerably less abject in their dress and demeanour, Schwall’s collection also includes a posed photograph of six Mission volunteers (Figure 10). In this photograph the six men lean and sit along a fence with the Guest House at St. Anthony in the near background.37 Assuming relaxed postures and facial expressions and with their hands in their pockets or in their laps, they gaze directly at Schwall’s camera. The men are named in the July 1915 issue of Among the Deep Sea Fishers as “Volunteer, Other Helpers” (1915: 83). They are: Harold D. Finley, Yale University; William Adams Jr., Yale University; Waldo Tucker, Yale University; William A. Rockefeller, Yale University; Charles McPherson Holt, Williams College; and Phillip Garey, Newark Academy (1915: 83, 84). Their attire — light-coloured shirts, sweaters, and jackets — would not be conspicuous among the Ivy League US colleges from which Grenfell recruited summer volunteers; only their boots attest to their participation in voluntary labour at the Mission (Harvard Crimson, 1925; Vassar Miscellany News, 1935).38 Millicent Loder (1989), the only Labrador-born woman to have worked as a nurse at the Mission, remarked on the gap in appearance between residents and those she termed “outsiders,” as is demonstrated in this image (see Perry, 1997). For those viewing this photograph 100 years later, another — historical — gap is all too clear: these young men represent a chilling contrast to the working-class men, Newfoundlanders among them, who were dying overseas in the muddy trenches of World War I, and to those Newfoundlanders who had so recently died in the 1914 sealing disasters.

46 No photographs of Mary Schwall, her sister Sally, or of their travelling companions appear in the collection. In one image, a shadow that may be the photographer — perhaps E. Mary Schwall — is evident.39 Eric Margolis and Jeremy Rowe explain:

Despite the absence of other images of E. Mary Schwall, viewers are nevertheless implicitly invited to imagine her presence on the landscape, and to consider the narratives that accompany these images. Contemporary viewing of this photographic collection expands the viewer’s access, familiarity, and knowledge of the Mission, of the colony of Newfoundland, and of Labrador. At the same, this viewing and its temporal framework transform Schwall’s images from her personal memories into “history” and re-sorts that “history” in relation to particular historical narratives (Carville, 2009: 94; Field, 2014).

CONCLUSION

47 Policy dictated that accounts of the Missions’ activities, whether authored by staff or volunteers, be vetted so as not to deviate from normative scripts and risk detrimental effects for Grenfell’s fundraising efforts (Perry, 1997: 28).40 The content and form of Schwall’s collection adhere closely to expected normative scripts for textual and visual representations of the Mission; and, in that way, her photographs provide a further justification for the necessity of the Mission’s presence and its activities (Perry, 1997; Bulgin, 2001). The photographs highlight the Mission’s continued financial need and reinforce the suitability of its staff and volunteers to improve the economic and physical health of its residents. Depictions of its activities and staff emphasize the necessity of work and industriousness, and document the gendered implementations of the religiously based social reform agenda that was the Mission’s purpose. This agenda was conveyed through the Mission’s geographical expansion along the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador, its architectural and social presence, and its control over activities — from consumer purchasing habits to medical care and rehabilitation — intended to instill habits of productivity and religious adherence, and to foster health and well-being.

48 Schwall’s photographs provide a “pictorial codification” of rural life in Newfoundland, and through their organization and presentation, they offer glimpses into the daily lives of those in Newfoundland and Labrador (Edwards, 1999; Carville, 2011: 51; Pedri, 2012: 253). As intentional constructions of Newfoundland, Labrador, and the Grenfell Mission, they reinforce themes that are also evident in other print and image materials, and that collectively contribute towards polyvalent conversations about the Mission, its work, and its workers.

49 E. Mary Schwall’s travel to Newfoundland adhered to efforts to attract American tourists, travellers, and adventurers to the colony, promoted in print as “America’s Newest Playground” (Legge, 2007: 429). No list of Mission volunteers is available for the summer of 1913; however, a list maintained for 1915 indicates that Schwall was one of 42 summer volunteers, 26 of whom were women, and 10 of whom were from the state of Massachusetts.41 Efforts undertaken at the Mission assured that Schwall arrived at a place that was already altered, through expectations, customs, and conventions, so as to be familiar to someone of her social background. Schwall’s collection visually depicts some of the Mission’s activities, and through them, its broad-reaching expectations, intentions, and ideals, including its gendered expectations. At the Mission, Schwall adhered to the conventions expected of women, and her volunteerism, whether it was in the Guest House, the summer classroom, or in the Loom Room, fit conventions about roles appropriate for women volunteers. It provides evidence of the Mission as a desirable site of middle-class women’s philanthropy, whether through their subscription to the Mission publication, the donations of goods, the purchase of handicrafts, and/or their voluntary labour. It also illuminates some of the ways that the Mission and its activities provided an acceptable travel destination and an acceptable avenue for middleclass women’s creative expression, including through amateur photography. These perspectives could become part of the analysis of the Mission in future studies.

50 Records maintained by the New England Grenfell Association suggest that after her visit, E. Mary Schwall did not maintain a connection with this branch of the organization, and no further personal connection between Schwall and the Grenfell Mission in Newfoundland or Labrador can be discerned (Conni Manoli, personal communication, 29 July 2014). However, E. Mary Schwall maintained her collection of photographs for the rest of her life, and upon her death, it was passed onto custodians who ensured its preservation. In this way, Schwall’s photographic collection continues to shape narratives about the landscape and the people of Newfoundland and Labrador, and about the Mission’s specific intentions towards that landscape and its people. It permitted Schwall to inhabit and to possess, temporarily and materially, the social and cultural worlds of the Mission in order to narrate its significance in ways that reinforced its importance for Newfoundland, for Labrador, and beyond these places.

I appreciate assistance provided by many people in conducting this research. Linda White directed me to this collection initially; she and Bert Riggs, Archives and Special Collections, Memorial University, provided archival assistance and valuable comments on an earlier draft. Three anonymous reviewers also provided valuable comments. Paula Laverty answered my early questions about E. Mary Schwall. Charles Conway, who prepared the map, and Dr. W. Gordon Handcock, Department of Geography, Memorial University, shared their geographical expertise about Newfoundland and Labrador. Tanvi Kapoor, Special Collections Assistant, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, assisted me with information about the Beatrice Farnsworth Powers Collection. Todd Gustavson, Technical Curator, George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, helped me to determine the camera type and model. Geoff Tooton, who shared information about the history and availability of photographic processing in St. John’s, Newfoundland, proved to be very helpful, as did Conni Manoli, William Munroe Special Collections, Concord Free Public Library, Concord, Massachusetts, who accessed information about the New England Grenfell Association. Dr. Jim Connor and Dr. Jennifer Connor, Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University, provided me with an opportunity to present an early version of this research at a conference on the topic of the International Grenfell Association. Finally, Brad Gibb assisted with proofreading and editing. Any errors and omissions that remain are my own.