Articles

On a Hillside North of the Harbour:

Changes to the Centre of St. John’s, 1942–1987

INTRODUCTION1

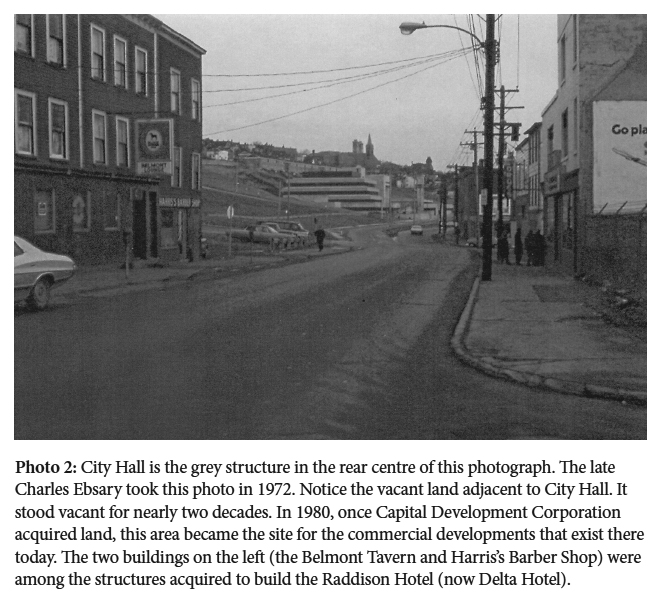

1 For both visitors and St. John’s residents under 40, the location from Carter’s Hill to Springdale Street (from east to west), and from John, Central, and Livingstone Streets to New Gower Street (from north to south) is merely the site of City Hall, Mile One Stadium, the Fortis Building, and the Delta Hotel.2 The area is less than one kilometre in length and less than 200 metres from north to south. It is one of the most expensive pieces of real estate in St. John’s. However, in 1945 this was not the case. This small geographical area was home to nearly 1,500 individuals — most of whom were working-class descendants of Irish Catholics who came to St. John’s in the early nineteenth century.3 It was characterized as a “slum,” “congested,” or “Dickensian” by commentators from Newfoundland (Horwood, 1997) and elsewhere (Bland, 1946; High, 2010). Most of the area was on a hillside overlooking the wealthier Water Street commercial district and harbour below; over the course of the first three decades after Confederation in 1949 the area was “blasted” and “bulldozed” in conjunction with rehousing the poor and urban renewal. This is a story of that transition.

2 This paper has three objectives. First, although previous work on St. John’s has provided solid documentation and analysis of the strategies connected with housing reform from the 1920s to the 1950s (see Baker, 1985; Collier, 2011a, 2011b; Sharpe, 2012, 2006, 2005, 2000), what is missing is an assessment of the population in the “slum area” that was rehoused. We know almost nothing about this population other than the fact that they lived in substandard housing above the St. John’s commercial district. Using data from the 1945 Newfoundland and Labrador census and secondary sources, and interviews with former residents of the area, this paper will show the social diversity of the low-income population that lived in this area.4 The residents of this area were employed in local manufacturing and service firms and secured their daily bread from the area. The slum area was not wholly impoverished — a fact that was not considered in alternative plans to rehouse individuals in better dwellings within the city centre as opposed to their relocation to centralized housing projects. Plans were provided by Bland (1946), Picket (1953), and Project Planning Associates (1961), but were never considered by St. John’s Municipal Council in its slum clearance projects of the 1950s and 1960s.5 The city, instead, concentrated on aspects of the Project Planning Associates (1961) report that emphasized infrastructural changes, such as the widening of New Gower Street to enhance traffic flow.

3 Second, I assess not only the development of housing reform strategies from the 1920s onward (especially since the 1940s). I also distinguish between the policies of the 1950s and those of the 1960s. During this period, Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) shifted from a mandate based on supporting access to new housing (1950s) towards one that combined such housing with urban renewal (1960s) (Bacher, 1993). This policy shift in the 1960s empowered municipalities to purchase cleared land for urban renewal that also involved commercial development. St. John’s Municipal Council provided itself with a mandate for development endorsed by the House of Assembly of Newfoundland. This fostered the “final clearance” of the slum from 1964 to 1966, which met resistance from some slum dwellers (residential and business) wanting better compensation. Although the clearance was beyond the time frame (1940s and 1950s) of previous work on housing in this area (Collier 2011a; 2011b; Sharpe 2012; 2006; 2000), it is considered here in some detail to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the issue. Resistance was accompanied by strategies for commercialization by Municipal Council — strategies that took nearly two decades to be realized. This began at a time when proposed suggestions for rehousing of the slum residents on land in the city centre owned by the city were ignored by Municipal Council (see Project Planning Associates, 1961; Regular and Special Minutes of St. John’s Municipal Council, 1964 to 1966). Instead, that body actively cleared the rest of the city centre in an attempt to attract commercial interests that could provide revenue the urban poor could not. By 1970, all that stood in the cleared slum area was a new City Hall.

4 Third, I assess the developments from 1970 to 1987 that eventually resulted in the commercialization of the city centre. By 1970, the slum was gone, but Municipal Council was in search of revenue-generating neighbours for the new City Hall. I cover this period by focusing first on the failed Trizec development. Then, I turn to the role played by CMHC in providing redevelopment funds to Canadian municipalities. In the late 1970s, the Neighbourhood Improvement Programs (NIP) and Residential Rehabilitation and Assistance Plan (RRAP) provided for the repair of homes and infrastructure. The significance of this, as we shall see, is that some of the homes designated for such repair were later acquired by Basil Dobbin in 1980 in conjunction with his Cabot Place Development. This development, starting with the Radisson Hotel in 1987, finally provided City Hall with commercial neighbours. In the process, much of the remainder of the low-income neighbourhood in the western portion of the city centre relocated. CMHC in the late 1970s left public housing to the provinces and their municipalities (Sharpe, 1993). At this time, Municipal Council, the Newfoundland and Labrador Housing Corporation, and private developers provided non-profit low- to middle-income housing in the city. Some of this is in areas adjacent to City Hall and the new commercial buildings.

5 In summary, plans for clearing the city centre only materialized after Confederation in 1949 and the introduction of CMHC policies. After the 1950s, urban renewal eventually led to the resettlement of the remainder of the slum area. While attempts to commercialize the city centre lay at the heart of the final removal, such plans were not realized for another two decades. In the process, some slum dwellers protested over the terms of their relocation from an area that could have potentially been redeveloped for residential purposes. Instead, the clearance for commercialization in the 1960s was the beginning of another set of processes — commercialization and the entry of infill housing in the city centre.

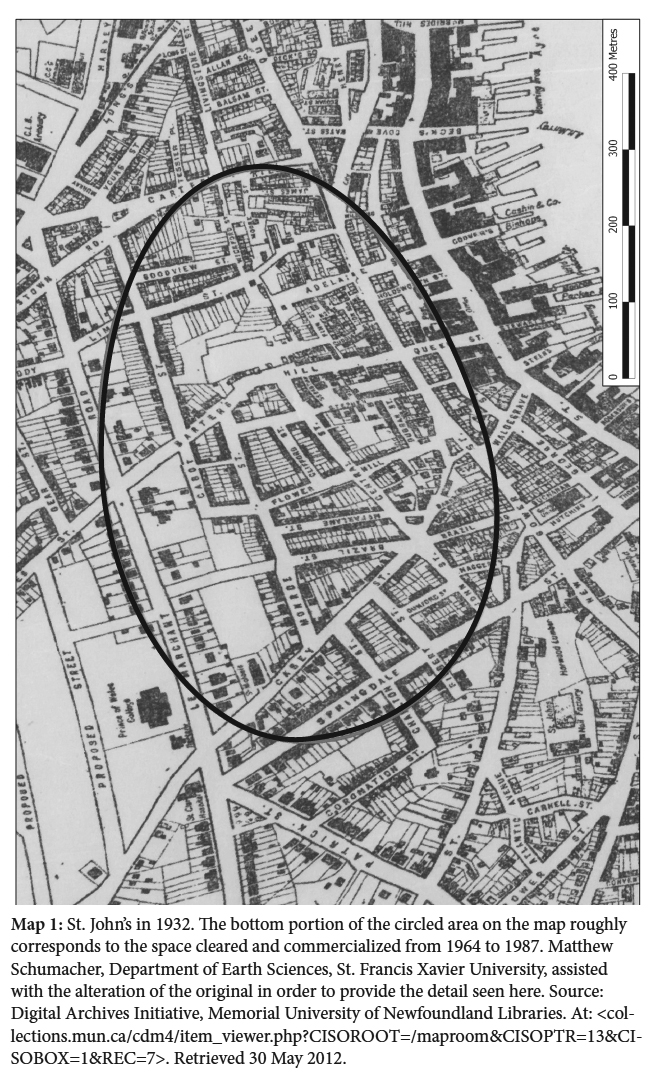

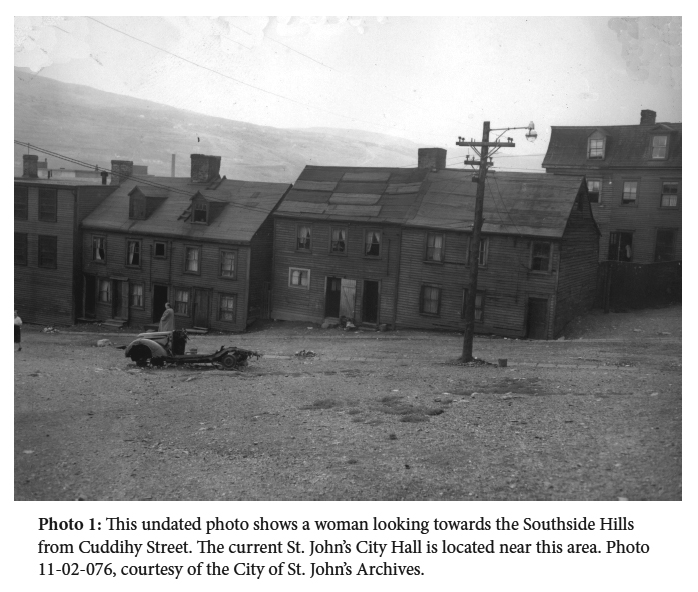

BEYOND THE SLUM: THE CITY CENTRE IN THE 1940S6

As a result of the congestion of buildings and the high density of population, this is also the area where the greatest number of street accidents occur, most of which involve children who have no other place to play but the streets. This is the area of juvenile delinquency, crime and sickness. It is called the slum.

John Bland, Report on the City of St. John’s (1946), p. 5

A few interviewees mentioned seeing signs of prostitution. . . . When asked if the town had a red light district, the interviewees usually pointed to the area that had formerly been a downtown slum but had been cleared to make way for the new city hall.

Steven High, “Rethinking the Friendly Invasion,”

in Steven High, ed., Occupied St. John’s: A Social History of

a City at War, 1939–1945 (2010), p. 179

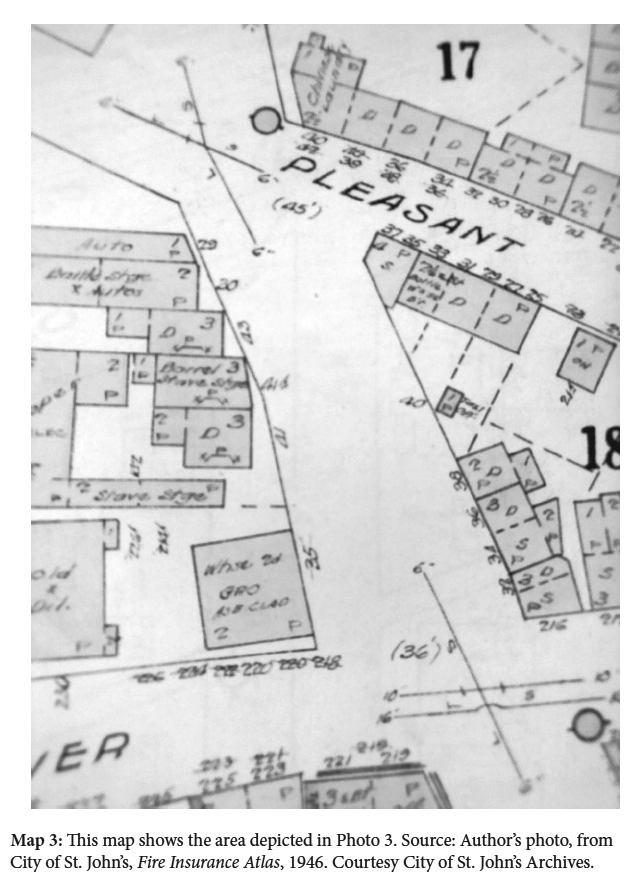

6 Bland (1946) and High (2010) refer to the city centre that is the basis of this paper. Those who live outside of poor areas usually stigmatize places occupied by “the poor.” Bland (1946), in his urban planning document for the Commission of Enquiry on Housing and Town Planning in St. John’s (discussed in the next section), and High’s (2010) interviewees may be correct in their estimation. However, neither writer provides a shred of evidence to substantiate the prevalence of crime in the area.

7 The fact that the city centre described in the first paragraph of this paper had substandard housing in the 1940s (and even before) is well documented by the policy and academic research discussed in the next section of the paper. However, that research (and the stereotypes raised above) tells us little about the community that lived in the space north of the commercial district of Water Street.7 Although the central objective of this paper is to provide an analysis of changes to the landscape of the centre of St. John’s, it is useful to know something about the wider social context of the population that was removed. As we shall see, the population of the city centre was not unlike the general population of St. John’s. However, substandard housing meant that the people living in the city centre were a perennial social and policy problem for Municipal Council until the final clearance in 1966. In the process, serious attention was never given to the positive dimensions of the wider community that occupied the hillside north of the harbour.

8 In the nineteenth century, St. John’s, a city occupied by Europeans since the sixteenth century, spread north and west of the harbour and the mercantile district of Water Street. The area that is the subject of this paper was settled as part of the growth of the city due to an expanding population swelled by Irish immigration (Lambert, 2010), as well as absentee landlords who benefited from the fact that St. John’s did not have a municipal government until 1888 (Baker, 1985).

9 The 1945 nominal census of Newfoundland and Labrador (the last census before Confederation in 1949) shows that the streets for the city centre (see Map 1) had approximately 1,500 residents (calculated from Government of Newfoundland, 1945). Over 65 per cent of this population was Catholic, many of whom may have descended from the Irish immigrant population that occupied the area in the nineteenth century, and perhaps from those who moved into the area after the 1846 and 1892 fires.8 In the remainder of this section, we consider the portion of the population (n = 500) that occupied an area in the city centre near the current City Hall (see Map 2 and Photo 1). This area contained some of the worst housing in the city centre and was demolished in the urban renewal process of the 1960s. This includes the following streets to the north of New Gower Street (Map 2): Adelaide Street, Barter’s Hill, Cuddihy Street, Dammeril’s Lane, Finn Street, James Street, Lion Square, Notre Dame Street, and Simms Street.

10 While the majority of the residents of St. John’s in 1945 also lived in the city in 1935, there had been some changes since the 1935 census. In St. John’s West, over 12 per cent (3,295) of the population (10 years of age and over) that lived there in 1945 resided in another part of Newfoundland and in 1935. The corresponding figure for St. John’s East was just over 13 per cent (2,952) of the population (Government of Newfoundland, 1949a).9

11 The city centre lay within the electoral district of St. John’s West. We do have a measure of internal migration for a portion of the city centre cleared in the mid-1960s to build City Hall. In 1945, over 19 per cent (96) of the population in this area was born elsewhere in Newfoundland 10 Only three individuals were born in another country. The more commercial New Gower Street area that formed the southern boundary of the entire city centre (circled portion in Map 1) had over 20 per cent (72) of its population born elsewhere in Newfoundland. There were also 19 immigrants on New Gower Street (over 5 per cent of the street’s population). This included immigrants from China (12), Syria (4), and Canada (3) (calculated from Government of Newfoundland, 1945). The Chinese and Syrians operated businesses most likely frequented by residents from the area to its north. Thus, the slum area and New Gower Street were largely Catholic, and included migrants from elsewhere in Newfoundland and some immigrants. This area was also largely working class.

12 Over the course of the nineteenth century, the labouring population of St. John’s shifted from fishing to the manufacturing and service sectors. Between 1874 and 1891 workers in secondary manufacturing increased from 34 to 67 per cent of the labour force. Clothing, footwear, confectionary, and baked goods firms serviced the local population (Lambert, 2010). In his observation of St. John’s in the 1930s, Newfoundland writer Harold Horwood (1997) remarked that the city was a “hive of industry.” Many of these industries were located in the western portion of the city (also see Bland, 1946).

Display large

image of Figure 1

Display large

image of Figure 1 Display large

image of Figure 2

Display large

image of Figure 2 Display large

image of Figure 3

Display large

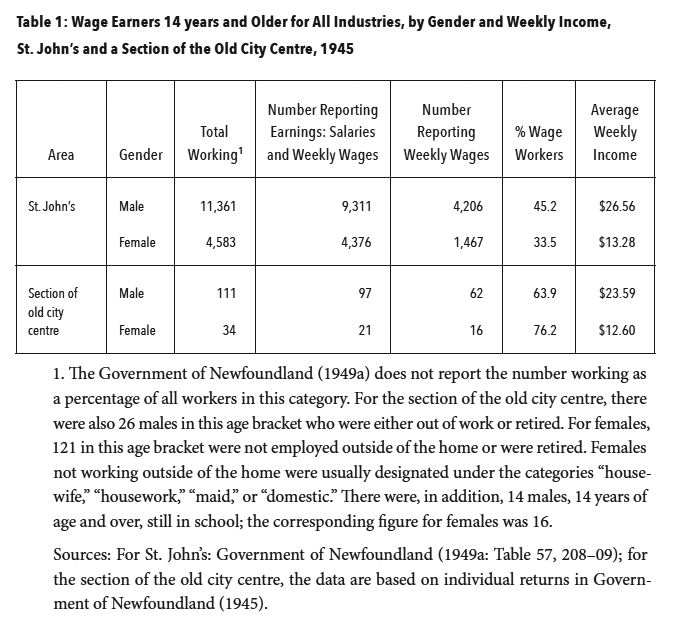

image of Figure 313 In 1945, there were 11,361 males and 4,853 females employed as wage earners in St. John’s. The service (2,869), transportation and communication (1,936), and manufacturing industries (1,887) were the main industries of employment for males. The service (2,664) and trade (894) sectors were the main areas of employment for females. A significant minority of females (1,084) in the service sector had employment as domestics. There were also gender differences in earnings. For example, males in all industries earned, on average, $26.56 per week, and females had average earnings of $13.28 per week, just 50 per cent of the male average. Female domestics, on average, earned only $5.76 per week (Government of Newfoundland, 1949a).11 These differences were most likely due to the fact that females worked fewer hours than males and earned less per hour. In addition, the much lower number of females employed most likely reflects the fact that women normally worked during the interval between the completion of schooling and marriage (see Forestell, 1989).

14 The patterns for the city as a whole were also reflected in the working population living in the area cleared for the new City Hall. Table 1 shows the wages for those 14 years and older who reported weekly earnings, for all of St. John’s and for the area in the vicinity of City Hall. Similar to the city as a whole, males were more likely to be employed than females, and the weekly earnings of males in the city centre ($23.59) were, on average, higher than those for females ($12.60). Thus, those in this portion of the city centre, while they occupied the substandard housing discussed below, had earning levels that closely matched the city as a whole. There was more than the stereotypical crime and prostitution in the city centre.

15 In addition, males and females participated in the manufacturing and service sectors along the lines of those in the city as a whole. Males in the portion of the city centre cleared for City Hall worked on the Newfoundland Railway, as truck drivers, as checkers in factories, in the armed forces, and as general labourers (Government of Newfoundland, 1945). Those employed as general labourers may have sought longshore work on the nearby St. John’s waterfront — which had daily queues for employment (Horwood, 1997). Some were also employed as bakers (in McGuire’s and Walsh’s bakeries in the city centre), in shoe repair, and as owners of small businesses. Some females worked in manufacturing with Purity (biscuits) and the White Clothing Company. Others served as sales clerks in local grocery stores and with retail outlets on Water Street, such as the Royal Stores. Some were also employed as checkers in manufacturing outlets (Government of Newfoundland, 1945).

16 There were also 41 businesses in the city centre north of New Gower Street (calculated from City of St. John’s, 1946).12 Many of these were family-owned stores along the lines discussed in Jack Fitzgerald’s autobiographical account of growing up in the city centre in the 1940s and 1950s. In speaking of the area, Fitzgerald (1997: 61) states that “[e]very neighbourhood was like a little village. Each had a confectionary store, grocery store, Chinese laundry, meat market, barber shop and shoemaker shop.” The area also included boarding houses on Brazil Square, two bakeries, a beverage company (American Aerated Waters) on Adelaide Street, and a bedding manufacturing firm (Standard Bedding) at the foot of Flower Hill.

17 The families in the area purchased their food from local stores where items could be gotten on credit (Fitzgerald 1997). According to Robert Hunt (2011), a long-standing butcher in the city centre he worked for in the 1960s told his customers short of money to pay him at another time. In addition, grocery stores employed boys on bicycles to deliver goods to customers in the neighbourhood (Fitzgerald, 1997). One individual who lived in this area from 1954 until 1974 noted that, in addition to meat sales, Casey’s Butcher Shop also delivered milk door-to-door until the mid-1960s.13 The store serviced several generations of residents in the city centre.

Display large

image of Table 11. The Government of Newfoundland (1949a) does not report the number working as a percentage of all workers in this

category. For the section of the old city centre, there were also 26 males in this age bracket who were either out of work or retired. For females,

121 in this age bracket were not employed outside of the home or were retired. Females not working outside of the home were usually designated under

the categories “housewife,” “housework,” “maid,” or “domestic.” There were, in addition, 14 males, 14 years of age and over, still in school; the

corresponding figure for females was 16.

Display large

image of Table 11. The Government of Newfoundland (1949a) does not report the number working as a percentage of all workers in this

category. For the section of the old city centre, there were also 26 males in this age bracket who were either out of work or retired. For females,

121 in this age bracket were not employed outside of the home or were retired. Females not working outside of the home were usually designated under

the categories “housewife,” “housework,” “maid,” or “domestic.” There were, in addition, 14 males, 14 years of age and over, still in school; the

corresponding figure for females was 16. 18 Farmers from outlying rural areas also frequented the area. Fitzgerald (1997: 162) writes that “news of who was selling what quickly spread by word of mouth, and women came out of their houses to line up to buy their supply of vegetables or meat for Sunday dinner.” In addition, many meat markets in the city (five in or adjacent to the city centre as a whole) owned their own cattle stocks. These grazed in fields in or outside of the city (Fitzgerald, 2007; Murray, 2002). Urban agriculture may have declined since the nineteenth century (MacKinnon, 2005), but it was still an important component of the food sourced by the families. In 1945, over 15 per cent (2,219) of the cattle greater than 1½ years, and over 21 per cent of milk production (602,823 gallons) in Newfoundland came from farms in St. John’s East and West (calculated from Government of Newfoundland, 1949b).14

19 In summary, the city centre emerged in the area north of the business district of Water Street in the nineteenth century. As employment in the fishery declined, the area’s inhabitants were employed in the manufacturing and service sectors. These features were still in place in the 1940s. City centre residents also sourced their food from local stores and outlying farms. However, changes over the next two decades, largely due to the poor housing in the area, resulted in the dispersal of city centre residents to other areas in St. John’s.

20 The city centre contained many homes without running water or sewage facilities. Public water tanks and night soil trucks (also known as honey wagons) were fixtures in many of the streets in the centre of St. John’s from the nineteenth century until well after World War II. At night, the inhabitants of these and other streets in the area were visited by a horse-driven night soil truck that took human waste and disposed of it in a collection tank at the top of Adelaide Street (see Map 1). Water tanks were used for collecting drinking and bathing water for many homes (see Fitzgerald, 1997). In fact, Cuddihy Street (Photo 1) was also known as “tank lane” for the water tank adorned by a lion’s head (as were other tanks in the area) (O’Neill, 2008). This tank was shared with the inhabitants of Lion Square.

21 The homes in the area were in very poor condition. This drew the attention of Municipal Council early in the twentieth century (Baker, 1983). Horwood (1997: 7), the notable Newfoundland writer who grew up in St. John’s in the 1930s and 1940s, commented that “[t]hose row houses, with broken windows, leaking roofs, and rotting front steps, and two or three families in basements or other tenements, were believed to shelter almost 5,000 people in conditions almost as bad as those in the London ‘rookeries’ or the east side tenements of New York.” The dilapidated conditions of the homes in St. John’s, in general, also caught the attention of Mona Wilson, who directed the Red Cross’s operations in Newfoundland during World War II (Poulter and Baldwin, 2010). In 1949, Humphrey Carver, Director of Research and Educational Funds for CMHC, a Canadian governmental body, made a visit to the area with David Mansur, the top official at CMHC. He commented on the women in the area using public taps for their household needs. This was in conjunction with the introduction of a federal-provincial initiative (discussed below) to finance housing development in Canada, of which St. John’s proved to be the first project (Carver, 1975).

22 Fitzgerald (1997: x), who grew up in the Flower Hill area, experienced the impoverished housing conditions in the city centre. “We lived in houses built for the 19th century, most with no water or sewerage, poorly insulated and in today’s society would be considered unbearably cold in wintertime.” As a youth, he and his friends would search neighbourhoods for wood to split and sell in bags to residents of the city centre. With seriousness and a touch of humour, he comments:

23 Fitzgerald’s comments relate to the 1950s. By this time, municipal, federal, and provincial governments were engaged in the move to public housing and in the resettlement of the population. The Commission of Enquiry on Housing and Town Planning, appointed in 1942, would have an impact on these developments. While, as we shall see, many of these houses had to be removed, some planners had proposals to rehouse some of the inhabitants in the city centre itself (Bland, 1946; Pickett, 1953; Project Planning Associates, 1961). However, political priorities and commercial objectives would dictate otherwise.

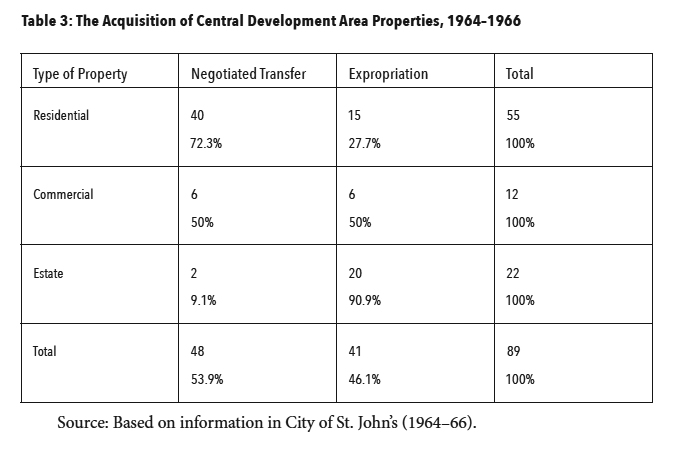

HOUSING REFORM IN THE 1940S

24 Although concerns over the “slums” north of New Gower Street date to the early part of the twentieth century, due to the absence of financing and its limited authority Municipal Council in St. John’s was not in a position to seriously engage in rehousing the urban poor. The initiatives that did take place were limited (see Baker, 1983; Collier, 2011a; Sharpe, 2005),15 and these did not affect the slum area. The city had the authority to expropriate properties and “prepare a scheme for the improvement of the same” (City of St. John’s, 1938: 31). However, there was nowhere to place the residents of the densely populated slum area.

25 In 1926, the Rotary Club invited to St. John’s Arthur Dalzell, a key planner and engineer from Toronto (Sharpe, 2000). Dalzell (1926) suggested that the city ask the Newfoundland government for funds to build houses for the poor and to appoint a Town Planning Commission. Dalzell (1926: 12) states: “[a] study of the plan will show that in the older and congested areas there are streets that should be either extended, diverted or widened to facilitate traffic, to act as firebreaks, to open up such property for building development.” While the housing was never built, the Town Planning Commission (TPC) was appointed. In 1930, Frederick Todd, Canada’s first twentieth-century resident landscape architect, came to St. John’s under the invitation of Justice Kent of the TPC. Todd’s suggestions do not survive, but he had a rudimentary plan to deal with the slum area (Sharpe, 2000). Todd proposed that the area be replaced and that the streets be rearranged as part of any planning. Rearranging the streets, though, would mean “much of this property will be too valuable to be used for this purpose” (cited in Sharpe, 2000: 52). This report was not used. It would take more than a decade before an intervention was made to deal with the slum area. In the meantime, the Commission of Government and St. John’s Municipal Council would debate the terms of how to deal with the slum area.

26 In the early 1930s, while in the midst of a severe financial crisis, the Newfoundland government’s Dominion status was suspended. For the next 15 years, an appointed Commission of Government ruled Newfoundland. During this period, it periodically clashed with the Municipal Council of St. John’s, which at the onset of the Commission’s rule was the only elected body in Newfoundland.16 Housing turned out to be an issue of contention. In 1934, the Commission offered Municipal Council a $500,000 loan to be used for improvements, including a slum clearance program. The city refused it because the Commission wanted jurisdiction over city spending until the loan was repaid (Baker, 1983). In 1936, the Commission of Government’s plan for reconstruction also involved a loan to the Municipal Council in exchange for taking control over municipal finances. In the Commission’s dispatch sent to London in 1936 by Governor Walwyn, impatience with the City of St. John’s is duly noted:

Municipal Council did not move in the direction suggested by the Commission of Government. It would take another three years before another initiative to deal with the slum area took place. This time, it came from within Municipal Council.

27 In 1939, Councillor John Meaney called upon the city and the Commission to provide an organization to build houses for the working poor (Sharpe, 2000). Meaney’s proposals were adopted by Council but not accepted by the Commission because it would have involved more financial commitment on its part (see Baker, 1983; Sharpe, 2005). In 1942, Deputy Mayor Eric Cook, who worked on a citizens’ committee in 1941 dedicated to slum clearance, moved to have the newly elected Council act quickly on the housing issue. Various segments of the community (including religious bodies, the Board of Trade, the Child Welfare Association, and the Newfoundland Federation of Labour) were asked to sit on a commission of inquiry on housing conditions in the city. Municipal Council asked the Commission to appoint the commission of inquiry, but wanted this commission to report to the municipality. The Commission of Government agreed on the condition that the commission of inquiry also reported to the government of Newfoundland. Council agreed and a 13-member body under the leadership of Justice Brian Dunfield was appointed in 1942 (Baker, 1983).

28 Over the course of the next two years (1942 to 1944), the Commission of Enquiry on Housing and Town Planning (CEHTP) produced five reports. Dunfield assumed a central role on the CEHTP, and while the policies he suggested did not directly lead to the elimination of the “slum problem,” these did lay the groundwork for reforms in the 1950s as Newfoundland benefited from Canadian housing policies. In particular, as we shall discuss below, the Churchill Park land assembly that was prepared as a result of the CEHTP provided serviced land that could take advantage of CMHC policies (Collier, 2011b; Sharpe, 2005).

29 Sharpe (2005) notes that the CEHTP was created on the assumptions outlined by Councillor Meaney in 1939 and reiterated in 1941: slum clearance and rehousing should take place within municipal boundaries; no new organization should be established; and the national (i.e., Commission) and municipal governments should not be builders of homes. All three principles would be violated. Before we turn to these “violations,” it is necessary to briefly examine the work of the CEHTP.

30 The CEHTP embarked on a survey of housing in the St. John’s area (CEHTP, 1942). There were 6,500 homes in St. John’s and the CEHTP received 5,700 survey responses that covered 4,613 homes (CEHTP, 1943). The survey dealt with issues such as the age and quality of homes, presence of sanitary facilities, housing density, the desire for better housing, and the capacity to pay for such housing (CEHTP, 1942).

31 On the basis of the survey, houses (in St. John’s as a whole) were classified into six categories: (A) excellent; (B) good; (C) fair; (D) tolerable but in need of replacement; (E) bad, i.e., needing to be condemned at an early date; and (F) very bad, i.e., needing to be condemned immediately. Nearly 38 per cent (1,750) of the 4,613 homes in the survey fell into the latter three categories. Table 2 summarizes the CEHTP findings for the last three categories of housing.

32 Generally, housing conditions worsen from one category to the next lower one, while the average number of persons per bedroom (a measure of housing congestion) is over 1 for every category. Moreover, the majority in the last two categories (E and F) had no water or sewer. As Dunfield points out (CEHTP, 1943), these homes were often in such bad shape that it wasn’t feasible to install water and sewer.

33 While the data are for the city as a whole, it is reasonable to assume, based on Dunfield’s remarks and previous observations, that a substantial portion of these substandard dwellings were in the city centre. Some of the streets in this area were pinpointed for their congested homes. Duggan Street had 9 houses with an average of 1.67 per room; the corresponding average for the 28 homes on James Street was 1.52. These were designated as category F dwellings (CEHTP, 1943).

34 The Third Interim Report (CEHTP, 1943) added that such congested conditions were not conducive to good public health. It noted insufficient light, dampness and cold, and poor ventilation, in addition to the absence of sanitary facilities, as factors for concern. It emphasized the problem of infant mortality in St. John’s in 1942, which, at 96 per 1,000 live births, exceeded the rates for Ireland (80), Canada (65), and England and Wales (59). The number of deaths from tuberculosis was also high. In St. John’s, the rate was over 145 per 100,000 population (five-year average from 1938 to 1942); in the Canadian Maritime provinces, the rates were 74 for Prince Edward Island, 73.8 for Nova Scotia, and 69.3 for New Brunswick.

Display large

image of Table 2

Display large

image of Table 235 The CEHTP (1943) response to this was not to engage in immediate slum clearance; its objectives were more modest. It noted most of those in slum housing conditions did not earn enough to afford better homes. The CEHTP argued for the establishment of the St. John’s Housing Corporation (SJHC) to build homes on available land outside of the city. This public corporation would have a housing scheme for those who earned from $1,500 to $1,800 per year. The objective would be to have a “filtering up” process whereby those better off would leave the congested area for new housing, and let those less well off move into the homes they left behind:

36 The data for the 1945 census for the houses in part of the area cleared for City Hall (see Map 2) show 30 owners and 47 renters. Of these, only six owners and renters had an income greater than $1,500 (calculated from Government of Newfoundland, 1945).17 The CEHTP proposals would not have been directed to those few in this category; instead, the objective would be for these owners and renters to occupy better homes in the city centre as those with higher incomes relocated to new housing.

37 This “filtering up” process never transpired. In 1944, the SJHC had a “sod turning” ceremony on Elizabeth Street (later Avenue) on a circumferential route in an area that used to be outside of city boundaries. The SJHC expropriated farmland northeast of the city for housing. This acquisition was based on a recommendation in the CEHTP’s Fifth Interim Report. The Commission of Government agreed to this expropriation of 800 acres of land (Sharpe, 2005; also see Lewis and Shrimpton, 1984). In her history of agriculture in St. John’s, Murray (2002) notes that some farming families resented the expropriation of the land and eventual demise of their businesses.

38 The end result was the building of homes for the middle class. This included 250 homes by 1947. These houses, in a suburb that became known as Churchill Park, raised the ire of Municipal Council and organized labour because they did not alleviate housing congestion. The Council had contributed over $1 million for new housing and the urban slum issue was still not solved (Sharpe, 2005).

39 The Churchill Park suburb contained homes out of the reach for all except for perhaps the most well-off in the city centre. The original estimate in 1943 of costs for the homes was from $2,500 to $3,500. However, by mid-1945, this estimate increased to $6,271 for a two-bedroom house to $7,000 for a four-bedroom house. The 20 houses sold by the SJHC in 1947 averaged $11,300 (but took $12,372 to build) (Lewis and Shrimpton, 1984). In 1945, the average price of the 30 homes owned by residents of the area (see Map 2) near the current City Hall was $3,183 (calculated from Government of Newfoundland, 1945). Churchill Park was most likely beyond the expectations of any of these homeowners.

40 The “filtering up” process behind the Churchill Park scheme may have been an unrealistic assumption by Dunfield, but he was a man of his times. Even CMHC officials in Ottawa in the late 1940s believed that the provision of an expanded housing market for middle-income earners would free up housing stock for lower-income individuals and prevent state involvement in social housing. Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent considered one unit of social housing to be one too many. His thinking pervaded CMHC in the early post– World War II period (Bacher, 1993).

41 However, the SJHC, through Churchill Park, provided the basis for the “orderly post-war expansion of St. John’s” (Sharpe, 2005: 107). Dunfield, in establishing the SJHC, laid important groundwork for housing in the decades after Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949. A land assembly had been prepared that CMHC took advantage of in the early 1950s (Collier, 2011b; Sharpe, 2005).

42 Before Confederation, the city acquired the Ebsary property northwest of the city centre and built 17 concrete buildings with four apartments per building (Rice, 2002). The city also provided water and sewer. This development was co-financed by Municipal Council ($75,000) and the Commission of Government ($300,000). Such accommodations were palatable to the general public because they helped the “deserving” poor who were unable to help themselves. The 17 properties on Ebsary Estate became known as the Widows’ Mansions. Some from the slum area were accommodated in these dwellings (Sharpe and Shawyer, 2012). Yet it was Confederation and the entry of CMHC that ultimately provided the dynamic that cleared the city centre.

AFTER CONFEDERATION: PUBLIC HOUSING IN THE 1950S

43 In the first decade of Confederation, St. John’s became one of the earliest beneficiaries of public housing in Canada. Some CMHC officials, especially Carver (1975) in the 1950s, shared Dunfield’s belief that the private market, by itself, would not provide adequate housing for all members of the population (see Bacher, 1993). However, the solution was not in the form of expanded social housing for all of those in need.

44 CMHC, as Bacher (1993) notes, kept to the market as much as possible in providing more housing for an urbanizing country. This was under the auspices of the National Housing Act (NHA). The NHA was passed in 1938 and authorized joint federal-provincial programs for low-priced homes on rental and owner markets (Dewing et al., 2006). In 1949, the amended NHA (section 35) called for “authorized cost-sharing by the federal and provincial governments for land assembly and servicing (75% was paid for by the federal government)” (Dewing et al., 2006: 6). To participate in the program, municipalities needed their provincial government to pass legislation that allowed them to administer provincial dimensions of housing activities (Dewing et al., 2006). Amendments to section 35 of the NHA coincided with the entry of Newfoundland into Confederation. In March 1950, the Smallwood government passed An Act to Provide for Slum Clearance and the Development of Housing Accommodation. This was aimed at rehousing those in the slum area in the city centre (Collier, 2011a).

45 This move to public housing was facilitated by housing and infrastructural developments prior to Confederation (Collier, 2011a; Sharpe, 2005). The SJHC was an established authority; serviced land was available due to its work in the late 1940s and acceptance of the need for government intervention in the housing field (Collier, 2011a).

46 The first six federal-provincial housing projects in the 1950s resulted in 584 units; 408 of these units were built in the area originally expropriated for the Churchill Park development (Collier, 2011b). According to Collier (2011b: 47):

The term “beginning” needs emphasis as the public housing projects of the 1950s only made a small inroad on the housing needs of those in the city centre. In fact, an urban renewal study in 1961 showed that over 1,000 new housing units were still needed for those in the city centre (Project Planning Associates, 1961).18

47 The first scheme, the Westmount project, was completed in 1951. It surrounded the Widows’ Mansions in an area northwest of the city centre. This project consisted of 140 housing units. It resulted in the demolition of 98 houses in the city centre. It followed in the wake of a series of meetings involving CMHC President David Mansur, CMHC Director of Research and Educational Funds Humphrey Carver, and O.L. Vardy, the provincial MHA for St. John’s West and Minister without Portfolio (Collier, 2011b). This project was the first in Canada and the only one undertaken in 1950 (Bacher, 1993). A second area in the northeast of the city (in the Churchill Park assemblage) consisted of 152 units, but only 24 houses were taken down in the slum area to become part of this project. While most of the first six public housing projects were outside of the city centre, 36 units were built on Livingstone and Goodview Streets in the city centre (Collier, 2011b). The public housing projects of the 1950s made only a small impact on the slum area, a factor that the City Planner, Stanley Pickett, commented on as he left his post in 1956 (Sharpe and Shawyer, 2012). Public housing projects would not rise substantially again until the mid-1960s.

URBAN RENEWAL AND THE CITY CENTRE: PUBLIC HOUSING IN THE 1960S

John Bacher, Keeping to the Marketplace:

The Evolution of Canadian Housing Policy (1993)

48 In the early 1960s, CMHC embarked on a new direction in regard to public housing. This dovetailed with urban renewal. Urban renewal was an attempt by CMHC officials like Humphrey Carver to make space for more social housing in a policy landscape still tightly connected to the provision of housing for middle-income Canadians. A 1954 amendment to the NHA brought the banks firmly into the mortgage market because CMHC provided insurance. This did not (nor was it intended to) solve the issue of affordable and quality housing for low-income Canadians (see Bacher, 1993; Carver, 1975). Carver (1975: 108) remarked about his experiences with CMHC in the early 1950s that “[t]he only interested party in the housing scene which didn’t seem to get much attention at the staff meetings of CMHC was the Canadian family which couldn’t afford home ownership.” In his autobiography, he stated that the most satisfying period of his life at CMHC was from 1955 to 1967. At this time, he was involved with an advisory group on urban renewal. Despite Carver’s desire to provide more housing that was not connected to the market, the urban renewal schemes he helped to launch had unforeseen consequences. The large-scale housing projects that came out of this met with resistance by the late 1960s and early 1970s (Bacher, 1993).The razing of low-income areas for commercial developments and the shifting of the urban poor to facilitate such projects were the impetus that eventually “solved” the “slum problem” in the central area of St. John’s.

49 In his 1956 resignation letter as City Planning Officer, Pickett (Shawyer and Sharpe, 2012) expressed frustration over the federal-provincial initiatives in the 1950s that had not significantly provided for the population in the slum area. For Pickett, too much of the housing development was targeted towards middle-income earners. In 1953, Pickett had prepared an urban development scheme for the slum area that included new streets east to west to combat the steep slopes of an area proving to be unsafe as the city entered the automobile age. Pickett (1953), like Bland (1946) before him, commented on how traffic coming out of the steep slum area was funnelling dangerously into New Gower Street. Pickett also discussed the widening of New Gower Street, and how new housing could be built on vacant land in the slum area in conjunction with new east-west streets. The widening of New Gower Street did not take place until the 1970s (in conjunction with the Harbour Arterial Road discussed in the next section). In the meantime, Municipal Council had the clearance of the slums as one of its chief urban development initiatives. In that regard, it emulated municipal councils in other Canadian cities (Bacher, 1993), including Halifax (Clairmont and Magill, 1999) and Saint John (Marquis, 2010, 2009).

50 The remainder of the slum area as far west as the bottom half of Casey Street (see Map 1) was cleared in conjunction with commercial developments in the 1960s. This was in contrast to a housing development study for the slum area proposed by Project Planning Associates (1961), a Toronto planning firm contracted by Municipal Council to make recommendations for urban renewal. While the study dealt with a range of issues including transportation and business development, the core of the report pertained to housing conditions in the city centre and other parts of St. John’s.19 Despite a decade of federal-provincial initiatives, many of the problems originally identified by the CEHTP (1943) still existed.

51 Project Planning Associates (1961) identified the city centre as part of a redevelopment area. The boundaries of the area stretched beyond the area discussed in this paper. It included New Gower to Cabot Streets (south to north) and Long’s Hill to Springdale Street (east to west). The area contained 4,800 persons in 1,023 households. The 708 houses in the area included 347 (over 34 per cent) that were deemed “bad” to “very bad.” Over 81 per cent (574) of the 708 houses were row houses. The inhabitants of the area were still living in overcrowded conditions with 1.07 persons per habitable room; at this time, the average for the city as a whole was 0.85 persons. Furthermore, since 1,023 households lived in 708 homes, this meant an average of 1.4 households per dwelling. Finally, over 40 per cent (440) of these households had no private bathroom and over 61 per cent (632) had no hot water.

52 Project Planning Associates (1961: 30) “recommended the acquisition, clearance and rebuilding of this area to be the first part of the St. John’s urban renewal program.” On the basis of a survey of owners and renters in the area (1,023),20 Project Planning concluded that over 75 per cent (767) wanted to remain in the area. To facilitate this, it recommended that Municipal Council make use of land it owned in the city centre for building new housing. The objective would be to build new houses for those in the most dilapidated dwellings first. Then, those dwellings would be removed to make way for more new housing. Eventually, the entire area would be rebuilt. Project Planning envisioned city centre inhabitants rehoused in 857 subsidized and 166 non-subsidized units. This would take 5–10 years to complete and would require Council to reach agreement with its federal and provincial counterparts under section 23 of the NHA in order to finance the project. This provision meant that funding would be split on a 50–50 basis between the federal and provincial governments. Dewing et al. (2006) note that the federal government could make loans to the provinces and municipalities to cover two-thirds of their 50 per cent portion.

53 Municipal Council moved to place the inhabitants of the city centre in better housing, but not along the lines recommended by Project Planning Associates (1961). In 1964, Mayor Harry Mews, along with C.W. Powell, the Deputy Minister of Municipal Affairs and Supply for Newfoundland, A. Vivian of CMHC, and Richard Cashin, the Liberal member of Parliament for St. John’s West, announced a tripartite agreement for the construction of nearly 1,000 rental units in St. John’s. These included: 186 in Buckmaster’s Field (an area north of the city centre), 400 in other areas (not specified) recommended by Municipal Council, and 400 in an area to be determined at a later date. Buckmaster’s Field was to be cleared of “substandard buildings.” The playing field and drill hall were to be maintained for recreation (Regular Meeting of Municipal Council, 3 Jan. 1964). This area was once farmland (see Murray, 2002) and then a site for Canadian forces from HMCS Avalon in World War II (Sharpe and Shawyer, 2010). The area to be determined at a later date turned out to be Municipal Council’s references to the “northeast land assembly” — an area near Torbay Road (Regular and Special Meetings 1964 to 1966, various dates). The minutes of the first Regular Meeting of 1964 noted that “it appeared that as a result of discussions of proposals certain properties enumerated in a schedule submitted could be acquired for 402,000” (Regular Meeting of Municipal Council, 3 Jan. 1964: 41). The eventual passing of An Act Respecting the Development and Redevelopment of Certain Areas in the City of St. John’s would facilitate the acquisition of such properties. This would empower Municipal Council to “declare and designate, as a result of an urban development or renewal area (‘hereinafter called ‘development area’), any area of the City of St. John’s which in the opinion of Council requires planning, designing, development, redevelopment, rebuilding or renewal (hereinafter called ‘development’) in the interests of the City or any part thereof” (Special Meeting of Municipal Council, 24 Feb. 1964: 69). The Act would give Municipal Council enormous powers to clear land for either housing or commercialization. It could enter into an agreement for “industrial, commercial, office, hotel, apartment or housing purposes or for the provision of public or private parking lots” (Special Meeting of Municipal Council, 24 Feb. 1964: 69). The Newfoundland House of Assembly passed this Act in June of 1964 (Government of Newfoundland, 1964). After that date, the properties in the city centre that Municipal Council could not acquire by negotiation were secured by expropriation. As we shall see, from 1964 to the end of 1966, Municipal Council used this Act to clear the city centre in tandem with a proposed commercialization on the same land.

54 In 1964, the city already owned two-thirds of the area included in the “Central Area Redevelopment” project. To foster further clearance, offers were made to property owners in the area. This included 130 properties, of which 70 were owner-occupied, 26 were businesses, and 34 were rental properties (Regular Meeting of Municipal Council, 1964). The Regular and Special Minutes from 1964 to 1966 only provide information on the acquisition of 89 of these properties. These are summarized in Table 3.

Display large

image of Table 3

Display large

image of Table 355 The properties turned over to Municipal Council after an initial or subsequent offer are defined as negotiated transfers. All other properties are defined as expropriated. This also includes those properties that reverted to Municipal Council after expropriation was announced and the owners attempted to settle for the Council’s previous offer. Council was not sympathetic as these property owners were offered a reduced figure from the one offered prior to expropriation.21 As Table 3 shows, business (50 per cent) and estate owners (90.9 per cent) were more likely to be expropriated. While there are some cases of resistance by the latter, it was more likely that the resistance of the former was recorded in the Regular and Special Minutes of St. John’s Municipal Council. This included some businesses (a bakery, a beverage company, and a furniture company) that relocated to other parts of the city. In addition, after acceptance of offers for 18 residential premises in the spring of 1964 (Special Meeting of Municipal Council, 22 Apr. 1964), many of the other owners resisted offers and faced expropriation. All of the 15 owners expropriated met this fate before the end of 1965 (Regular and Special Meetings of Municipal Council, various dates, 1964 to 1966).

56 One of the concerns was over the enactment of legislation in 1952 (and its renewal up to 1966) that prevented repairs to buildings in the area beyond those needed to keep the “elements out” (also see Pickett, 1953). Those occupying dwellings felt that this depreciated their properties. In the spring of 1964 some residents formed a committee addressed by A.J. Murphy, the Progressive Conservative member of the House of Assembly for St. John’s Centre — the riding where the slum was located. The objective was to lobby for better compensation (Evening Telegram, 8 May 1964). Despite this, St. John’s Municipal Council expropriated residential and business owners who did not accept the financial compensation offered. In the summer of 1966, Council received a letter from one of the organizers of the 1964 committee asking for better compensation, in the form of tax concessions and rebates, because of the prohibition of new construction from 1952 to 1966 (Special Meeting, Municipal Council of St. John’s, 20 July 1966). In correspondence with this writer, that individual noted:

However, the die was already cast. The Municipal Council had vast powers of expropriation and development rights over the slum area — rights that the Smallwood government had endorsed by passing the city’s “development” legislation in June 1964. The last property in the designated area was removed before the end of 1966.

57 In tandem with slum clearance was the Municipal Council’s proposed commercial development in the cleared area in the city centre. The St. John’s Commercial Centre Company Limited was a constant reference in Municipal Council minutes from September 1964 to end of 1966, when an agreement was reached with this entity to erect a commercial development in the city centre. At the heart of Municipal Council’s proposals was the greater revenue that could be earned from such a development. A special meeting was convened on 22 September 1964 to:

Municipal Council announced that the ground rents in an option to be signed with the St. John’s Commercial Centre Company Limited would be $60,000. This was to be signed by 31 October 1964 (Special Meeting of Municipal Council, 22 Sept. 1964).

58 However, in order for Municipal Council to get a secure agreement for development, it needed to clear the city centre. As we have seen, this took another two years of negotiation and expropriation. The owners of St. John’s Commercial Centre Company Limited are never revealed in the minutes of Municipal Council. A Montreal law firm represented this entity in meetings with Municipal Council from 1964 to 1966 (Regular and Special Minutes, 1964 to 1966, various dates). One informant speculated that this firm was a “shell company” owned by prominent St. John’s businessmen.23 However, we have no verification of this.

59 Negotiations with St. John’s Commercial Centre Company Limited eventually drew the attention of the downtown business community concerned over its decline and the prospects that the new firm posed for its competitiveness. St. John’s Commercial Centre Company Limited had plans for commercial and office space in the city centre — plans that included the leasing of land purchased from the city for a new City Hall linked to the new commercial complex. Before Municipal Council reached an agreement with St. John’s Commercial Centre Company Limited in late 1966, it fielded concerns from both the Newfoundland Board of Trade and a group representing downtown business interests. In a letter, the former indicated that:

This is the only recorded communication (in terms of Municipal Council minutes) between the Newfoundland Board of Trade and Municipal Council. However, in August, September, and October of 1966, the downtown business community represented by prominent figures such as Derek Bowring, Lewis Ayre, and John Murphy made written submissions and personal presentations to Municipal Council. Derek Bowring of the Bowring Company (present in Newfoundland since 1811) indicated that Water Street firms developed an Association to “preserve property values on Water Street, particularly in light of the Sobey Development in the Kenmount Road area and contemplated development on the north of New Gower Street.” The delegation asked Municipal Council to share one-half of a $15,000 consultancy fee to assist in the development of their Association (Special Meeting, Municipal Council, 29 Sept. 1966: 500–01). The Sobey Development on Kenmount Road turned out to be the Avalon Mall, Newfoundland’s first indoor shopping centre complete with abundant outdoor parking. John Murphy, owner of the discount Arcade Stores (and future mayor) indicated that the downtown association was concerned over “the fact that the Avalon Mall on Kenmount Road area would be opening in early April 1967” (Special Meeting, Municipal Council, 7 Nov. 1966: 575).

60 Murphy had good reason to be concerned. As Shrimpton and Sharpe (1980) indicate, by the early 1970s the movement of business interests to the periphery of the city coincided with the decline of the downtown core. By the early 1970s, major downtown stores either closed or relocated to shopping malls outside of the core. St. John’s had a surplus of retail space. This, combined with the shortage of parking in the downtown area (as opposed to the shopping malls), meant less retail dollars for downtown merchants (Shrimpton and Sharpe, 1980). In addition, the removal of the bulk of the population from the city centre had negative economic consequences because this removed “a captive market for the Water Street shops” (Sharpe and O’Dea, 2005: 161). Between 1961 to 1976, the inner city of St. John’s (which surrounded and included the slum area) had the largest population decline of any Canadian city. During this time, it experienced a population decline of over 37 per cent (Shrimpton and Sharpe, 1980).

61 On 21 October 1966, Municipal Council and St. John’s Commercial Centre Company Limited signed an agreement (Special Meeting, Municipal Council, 21 Oct. 1966). Land in the city centre between Carter’s Hill and Adelaide Street (see Map 1), known as Area “C,” would be leased to the St. John’s Commercial Centre Company Limited, and as “the first phase of the Central Area Development the Company is to erect on Area ‘C’ under a separate lease a City Hall-Office Building” (1966: 544). Areas “A” and “B” would have a commercial retail complex. The remainder of the agreement refers to the preliminary design of the City Hall, including parking, and the nature of the commercial retail complex. The lease for City Hall would be for 25 years (rate is not specified). Areas “A” and “B” were to be leased to the developer for 77 years at $45,250 per annum (Special Meeting, Municipal Council, 21 Oct. 1966).

62 In the midst of the slum clearance it was revealed that Municipal Council developed a “secret fund” in the 1950s and 1960s for the purposes of a new City Hall. Former Mayor Harry Mews announced this fund’s existence in 1966 in an address to the Rotary Club. A new City Hall, at a cost of $3.5 million, was opened in 1970. The proposed commercial development never transpired. St. John’s Commercial Centre Company Limited decided not to go ahead with the development (Baker, 1991). The reasons why are not revealed, but it may be likely that, as well as the declining downtown business community, it was concerned about the growing competition of the Avalon Mall and the fact that the inner-city population (which included the city centre) was in decline. In addition, the company may not have been able to attract enough tenants.

Display large

image of Figure 4

Display large

image of Figure 463 Where did those cleared from the city centre to make way for commercialization end up? Although we have no firm evidence, it is reasonable to assume that some ended up in social housing. In 1965, Buckmaster’s Field (locally known as Buckmaster’s Circle) to the north of the city centre became one of the housing projects built under federal-provincial CMHC funding for rehousing some of the former residents of the city centre. It consisted of 210 units (Collier, 2011b). This development was financed by a tripartite agreement with the government of Newfoundland and CMHC (Special Meeting, Municipal Council, 15 June 1966). The city made arrangements with the Royal Bank of Canada to raise $5 million for the project (Special Meeting, Municipal Council, 8 June 1966). The province provided $500,000 (Special Meeting, Municipal Council, 15 June 1966). The amount provided by CMHC is not revealed in Municipal Council minutes.

64 Centralized block public housing units developed since the 1950s, such as Buckmaster’s Circle, were also meeting with opposition from St. John’s residents. Sharpe (1993: 73) notes:

In his study of policing in St. John’s, McGahan (1984) wrote that the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary labelled the Buckmaster’s Circle area as problematic. Mellin, a St. John’s architect (2011: 70), regarded the area as one not conducive to community living:

65 Even individuals from other low-income (and equally stigmatized) areas considered Buckmaster’s Circle problematic. This included the parents of students at Holy Cross School. In early 1970, the drill hall in the centre of Buckmaster’s Circle became for a three-year period the site for Holy Cross, a Catholic boys’ elementary school. The school on Patrick Street in the west end of the city was lost in a fire on 11 December 1969. During the early 1970s, boys from the area in the city centre west of the new City Hall were warned not be in Buckmaster’s Circle after dark as there was a “hard crowd” up there. In other words, once school was over, come on home.24

66 Other former residents of the city centre may have wound up in social housing in the northeast land assembly. Two of my interviewees indicated that some moved in with relatives in other places in the city centre and downtown area, including houses on Gower Street.25 Sharpe (1993) states that some of the houses on Gower Street were abandoned and provided accommodation for some of those removed from the city centre. Above all, what did emanate from this clearance was Municipal Council’s desire to have commercial neighbours on the vacant lands to the west of the new City Hall. For nearly two decades, the grey bunker-like City Hall structure was the only occupant of land between New Gower and Central and Livingstone Streets (south to north) and Carter’s Hill and Barron Street (east to west) in the city centre. Eventually, however, the city centre became commercialized.

COMMERCIALIZATION AND INFILL HOUSING, 1970–87

67 The period from 1970 to the late 1980s witnessed commercialization, a heritage movement, and infill housing. First, we consider the failed Trizec development to the west of the new City Hall. This is followed here by a consideration of policy changes in CMHC that involved the repair and rehabilitation of properties in Canadian cities, as opposed to block housing developments (see Bacher, 1993). These changes were embraced by St. John’s Municipal Council but within the context of promoting commercialization that impinged on such developments. In the midst of this, an emerging heritage movement voiced concerns over the deterioration of historic properties by commercial developments. Third, within this milieu City Hall finally received revenue-generating neighbours. This included the Cabot Place Development that resulted in the clearance of other properties in the city centre in 1982. Finally, Municipal Council, in conjunction with the Newfoundland and Labrador Housing Corporation (NLHC), provided for infill housing; much of this would be situated in the downtown area, which included cleared areas in the city centre.

68 In the early 1970s, the area to the west of City Hall was the only significant vacant area in the city centre. Trizec Corporation of Montreal purchased some of this land in October 1974 for a planned development of three towers (including a 16-storey hotel) on top of a seven-storey base. The overall development was to include retail outlets, office space, and parking. Part of the agreement with Municipal Council involved the provision that the city build a harbour arterial road to enhance the movement of people and goods from the northeast of the city (location of the airport) to the Trans-Canada Highway (Shrimpton and Sharpe, 1980). This road was a controversial project that drew the attention of interest groups such as the heritage movement and the Southside Citizens’ Committee. The former group was concerned with developments that undermined historic properties in the city. The latter group was concerned with the fact that the harbour arterial was directed towards their homes. Due to their protests, modifications in the original design were made (Sharpe and O’Dea, 2005). The road eventually was constructed, beginning on a widened New Gower Street before winding its way around the end of the harbour and turning right towards the Southside Hills before connecting with the Trans-Canada Highway.

69 In November 1976, Trizec informed the Municipal Council that it was backing out of the arrangement because the provincial government refused to fulfill its agreement to be a tenant in the complex. The provincial government denied it had abrogated the agreement. The city entered into litigation over the agreement in 1978, arguing that it completed its contractual obligations by building the harbour arterial road project. In 1979, the city and Trizec entered a settlement whereby the corporation sold the land back to the city for its original price (Shrimpton and Sharpe, 1980).

70 The Trizec development and the arterial road were part of disputes over the development of the downtown core and adjacent areas. Atlantic Place and TD Place on Water Street emerged as controversial topics. These buildings clashed with the interests of the heritage movement that was gaining some leverage with Municipal Council (see Sharpe, 1993; Sharpe and O’Dea, 2005; Shrimpton and Sharpe, 1980). While these structures were being built, the heritage movement was successful in making heritage zoning a part of Council policy. Over the course of the 1980s and 1990s, more land in the downtown core and adjacent areas was successfully placed in a heritage area that placed limitations on such features as the height and external presence of buildings (see Sharpe and O’Dea, 2005). Before the heritage movement’s aims were partially institutionalized, more land in the city centre became subject to commercialization. Since this land was originally part of a renovation project funded by the federal government, it needs discussion here.

71 In the 1970s, Canadian municipalities attempted to gain more policy leverage in the midst of federal-provincial disputes over policy. One area was housing. In 1971, the newly formed Ministry of Urban Affairs presented an opportunity for municipalities to lobby Ottawa directly for more funding. CMHC switched from being under the Department of Finance to Urban Affairs (Dewing et al., 2006). In 1973 amendments to the NHA, 100 per cent loans were made available to non-profit housing groups. These groups became eligible for loans to purchase and rehabilitate older homes (Bacher, 1993). The loans were also available to private homeowners. In the 1970s, this impacted the city centre of St. John’s, as well as other Canadian cities. The Neighbourhood Improvement Program (NIP) and Residential Rehabilitation Assistance Program (RRAP) were CMHC vehicles used in the 1970s to upgrade old neighbourhoods.

72 The NIP dealt with public facilities. Most of the city centre was included in one NIP. Almost all residential units in this NIP were eligible for upgrading under the RRAP. By 1982 (when the RRAP ended), nearly $9 million had been spent upgrading 1,760 dwellings. The NIP and RRAP were undermined by the absence of a co-ordinated plan for the development of St. John’s. The “encroachment of commercial developments into residential areas was permitted, perhaps even encouraged” (Sharpe, 1993: 18). This encroachment would not be curtailed until the development of a city plan in 1984, but before then the last remaining area of the old city centre was cleared for commercialization.

73 In 1980, 130 houses were acquired by Basil Dobbin, a local developer, and demolished by 1982 (Junior Achievement, 2013). Plans were in place for a 10-storey office block, most of which lay within the West End NIP (Sharpe, 1993). Trahey (2000: 115) writes that this acquisition of homes “rivaled in extent the earlier slum clearance.” The homes in question were located from New Gower Street to the south side of John Street (south to north) and from Barron Street to Springdale Street (east to west) (see Map 1). In reflecting on this development, Sharpe (1993: 88) writes:

The proposed building was to be one of five planned units and the regional headquarters of a national engineering firm (Sharpe, 1993). Like the Trizec complex before it, this building was not constructed. However, the former Trizec site and the newly cleared land became part of the Cabot Place Development site where Dobbin, in conjunction with Manulife Financial, built two towers. The expected Hibernia oil development encouraged such investment (House, 1985; Trahey, 2000).

74 The first tower (built in 1987) became the Radisson Hotel (now Delta Hotel). In addition, an underground parking garage was built into the hill where the hotel was located. In 1988, a second 12-storey office tower was built; this building was under-leased until the federal government purchased it in 1995 (Trahey, 2000). One of the restaurants in the Radisson Hotel was named Brazil Square. The hotel was on top of the former street.

Display large

image of Figure 5

Display large

image of Figure 575 The need for subsidized and low-rent housing did not disappear with the slum clearance of the 1960s and the NIP and RRAP programs. In fact, Bacher (1993) argues that the latter had the ironic effect of inflating housing prices and further displacing low-income earners. And, as we have seen, the Cabot Place Development removed even more low-income earners from the little that was left of the residential area discussed in the opening paragraph of this paper. This was after NIP and RRAP funding for some of these residents.

Display large

image of Figure 6

Display large

image of Figure 676 By 1982, more than 500 individuals were on the waiting list for public housing and more than two-thirds of these were in the inner city of St. John’s. This area included the city centre (Sharpe, 1993). However, CMHC would not be involved in the next stage of housing the St. John’s urban poor. In 1978, it withdrew from direct involvement in financing public housing and directed future housing to arrangements between the provinces and their municipalities (see Bacher, 1993). In 1981, the SJHC was absorbed by the NLHC. In 1986, an agreement between the federal government and the province set the boundaries for Urban Living, a non-profit housing corporation operated by the city of St. John’s. NLHC and private developers joined the city in housing developments. These included rehabilitation of existing units (mostly done by private developers) and infill housing (mostly done by the City and NLHC) (Sharpe, 1993). The latter are discussed below.

77 In 1982, Municipal Council directly provided for low-income housing under Section 56.1 of the NHA. This included infill housing on vacant lots — some of which still existed in the city centre (Sharpe and Shawyer, 2012). The infill housing program was “intended to encourage the development of vacant lots by allowing higher-than-normal densities, and rehabilitation of older units” (Sharpe and Shawyer, 2012: 2). This is non-profit housing based on affordability for low and medium-income families. These housing units are meant to be revenue-generating. Rent supplements are provided for at least 15 per cent of units. For our purposes, the importance of this lies in the fact that most of the projects in the first decade (70 per cent) of Urban Living’s program were concentrated in downtown residential areas (Sharpe, 1993). One of these is Sebastian Court, a 29-unit lower end of the market (LEM) development established just east of City Hall in 1986 in an area of the old city centre that was cleared in the mid-1960s. In addition to LEM, the St. John’s Non-Profit Housing Division has rent geared to income (RGI) properties. One of these is a 65-unit complex on Hamilton Avenue, which lies just west of the Delta Hotel (although separated by “undeveloped” land) (Sharpe and Shawyer, 2012).

78 By the 1987, the dynamic in favour of commercialization had taken hold in the city centre. The end of the 1990s saw much of the city centre filled with commercial buildings that included the Fortis property next to the Delta Hotel and Mile One Stadium, which now (since 2012) serves as the home base for the St. John’s IceCaps, the farm team of the Winnipeg Jets. Across the street from these developments is the St. John’s Convention Centre. Sebastian Court, an infill housing development, is next to City Hall, a reminder of the lowincome population that once dominated the hillside north of the harbour.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

79 The “slum” on the hillside north of the harbour no longer exists. In the case of St. John’s, the move to commercial development was merely the last stimulus in the resettlement of the slum area. There were plans by city elites to resettle this population that date to the early twentieth century. What began as a “social problem” eventually morphed over the first three decades of Confederation into a commercial solution. The “slum problem” was eventually solved, but for selfish as opposed to altruistic reasons (see Sharpe, 2000).

80 This paper covered the initiatives that fostered the clearance of the city centre from 1950 to 1982: the 1950s and the entrance of CMHC funding; the 1960s and urban renewal and clearance of the designated slum area; and the 1970s and 1980s and the clearance of much of the remainder of the city centre population. In the process, the centre of St. John’s became a commercialized space, albeit with some infill housing. The area as a whole experienced significant depopulation from 1961 to 1981 (Sharpe and O’Dea, 2005). Slum clearance removed much of the population, and others moved to newer developments in St. John’s and elsewhere.

81 In the process, the fact that there were suggested alternatives to the “slum problem” by using public monies in the area north of the harbour did not bear consideration by those with power and influence. While much of the congested population in the area needed to be relocated to other areas due to substandard housing and the absence of adequate infrastructure, the fact that two-thirds of the land in the area cleared in the mid-1960s was vacant and owned by the city suggests that Municipal Council could have made use of CMHC funds to rebuild. Project Planning Associates (1961) even had a plan. The housing portion of this plan for a rebuilt city centre was not considered. The plan may not have been feasible, but history shows that the commercialization process was a protracted one. Without the Hibernia oil project, City Hall might still be looking for commercial neighbours.

82 With the exception of City Hall, the cleared area as far west as Barron Street remained vacant for nearly two decades. Children would bobsled down the steep slopes adjacent to City Hall during winter months in the early 1970s. Municipal Council installed snow fences so they would not slide into traffic on New Gower Street. This, instead of commercial interests, is the activity that occupied this area. By the early 1980s, nothing remained. The hillside was blasted away for commercialization.

83 This is no romantic overture to the past. As an individual who resided in the portion of the old city centre bulldozed in the early 1980s to make way for Cabot Place Development, and descended from a family that lived on Lion Square in the slum area (1860s until 1961), I know that life was difficult in this low-income area. However, this group of urban poor had access to livelihood opportunities and met their needs in ways that the current urban poor probably cannot. The old city centre had a degree of social diversity that was not replicated when the urban poor were relocated. It was certainly not replicated in block housing developments. These projects were divorced from shopping and work arrangements. Homogeneity replaced heterogeneity at a time when alternatives were being discussed (e.g., Project Planning Associates in 1961) but never seriously explored.

84 While these last comments are a subject for another paper, we must remain aware that the policy choices made in the past were not the only options available. To believe so is to constrain our notions of the types of housing futures that can be explored in the ever-changing landscape of St. John’s.