Documents

The Notre Dame Bay Memorial Hospital, Twillingate, 1933:

An Institutional Profile in a Time of Transition

OVERVIEW

1 In 2014 the Notre Dame Bay Memorial Hospital (NDBMH) in Twillingate will celebrate almost a century of continuous service. The hospital’s first 10 years of operation since opening in 1924 were under the direction of Dr. Charles E. Parsons (1892-1940), a tireless and dedicated physician and surgeon. Despite Parsons’s crucial role, his tenure was eclipsed by the much revered Dr. John M. Olds (1906-1985), who succeeded Parsons as Medical Director in 1934 and whose connection with the hospital would span close to 50 years.1 The year 1933-34 was pivotal for the hospital owing to the departure of Parsons and his replacement by Olds. Although the transition went smoothly, it was not without controversy due to Parsons’s all but mandated resignation, ostensibly for reasons of ill health related to alcohol abuse. The year 1933-34 was one of even greater transition for Newfoundland due its economic woes, which saw it relinquish its own system of responsible government in favour of being administered by British-appointed commissioners.2 The domestic troubles of the hospital and those larger ones of the dominion coalesced not only because of timing, but also as a result of the involvement of leading figures such as Sir Wilfred Grenfell (1865-1940), Frederick C. Alderdice (1872-1936 — first in his capacity as Prime Minister of Newfoundland and then as a Commissioner), Sir John C. Puddester (1881-1947), Dr. H. M. Mosdell (1883-1944), and, of course, Parsons and Olds.3

2 Surviving correspondence between these men over the NDBMH, along with a highly informative commissioned report based on a medical audit and site visit of the NDBMH occasioned by prevailing concerns, provide a most useful institutional profile of the hospital at this time: medical, surgical, economic, administrative, political, personal, and social aspects were all addressed.

THE NDBMH, SIR WILFRED GRENFELL, THE COMMONWEALTH FUND, AND DR. CHARLES PARSONS

3 Following the First World War, the people of Twillingate and the Notre Dame Bay region wished to establish a permanent memorial to local men killed in action; establishing a hospital was decided as a fitting tribute. Although the NDBMH was never part of the International Grenfell Association (IGA), it did initially fall within Wilfred Grenfell’s personal sphere of influence. Grenfell was the most prominent and only non-Twillingate member of the NDBMH Association founded in 1924 to oversee this institution.4 Grenfell was also instrumental in securing tens of thousands of dollars to build and expand the hospital through the Commonwealth Fund (CF), a philanthropic foundation in New York City. The retention of the one of the most prominent architectural firms in North America to design the new Twillingate hospital can also be traced to Grenfell. William Adams Delano, senior partner of Delano and Aldrich of New York City, had admired Grenfell since their first meeting in the early 1900s.

4 Despite the critical technical and financial support obtained from the United States, the actual building of the hospital was an intensely communitydriven project. For three years, local tradesmen — often trained on the job site in the skills of masonry, concrete technology, and plastering — created a monument to commemorate the past as well as an edifice that ushered in the future. The CF annual report for 1925 drew attention to the inordinate efforts of the people of Notre Dame Bay in this regard. The “remote location” led to protracted problems, but the “devotion of the people of Twillingate” and their “generous giving of their time and labor in transporting freight, digging roads, installing the water system . . . working nights throughout the summer . . . [and] undergoing every discomfort” culminated in the opening of a fully functioning hospital in September 1924.

5 Five years later, $50,000 more was forthcoming from the New York philanthropists to add a new wing, including a children’s ward. The CF “took special satisfaction” in its support of the NDBMH owing to the hospital’s impressive success and mission. Not only was it the only hospital to serve the 50,000 fishermen and their families along 300 miles of coast, but area residents had demonstrated their whole-hearted commitment to the institution through their free labour and the over $80,000 that they had raised. One incident recounted by the CF that clearly underscored the spirit of community voluntarism, to say nothing of illustrating the remote and exotic nature of this northern colonial land, was a house haul. Although not an uncommon event in Newfoundland outports, the event was marvelled at in the 1929 CF annual report, which noted, almost incredulously, how 600 men dragged a frame house for two days over three miles of snow and ocean ice in order to provide a home for hospital nurses.

6 The continuing philanthropic support enjoyed by the hospital is noteworthy in several ways. First, this expression of generosity by the CF has previously gone unnoticed by both American and Canadian historians. Second, it appears that supporting projects outside of the continental United States was not typical for the CF, so this gesture is all the more significant. Finally, the initial financial contribution to the NDBMH took place several years before the CF formally decided to fund rural hospitals; the highly successful Newfoundland experience that was grounded in its demonstrable community support appears to have been used as a pilot project for the CF’s Division of Rural Hospitals. This program operated from 1926 to 1948 and saw funding for 15 institutions located in the southern and northeastern United States.5

7 It was also Wilfred Grenfell who orchestrated the appointment of Dr. Charles Edwards Parsons as the hospital’s founding Medical Director. Parsons, an American born in Colorado and a 1919 graduate of Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins University, the leading medical school in the United States, had first served the IGA in 1913 as a teacher when still an undergraduate student at Amherst College, then as a medical student assistant, and later as a physician on both the hospital steamer Strathcona and at the Battle Harbour Hospital in Labrador. During his decade of service at the NDBMH, Parsons literally helped plan, design, and build it; he also was the key person in making the institution operational. On the hospital’s tenth anniversary, a Twillingate Sun editorial described Charles Parsons as “kind and generous . . . almost too big hearted,” and stated that he was to be remembered with “love and gratitude.” Similarly, on this occasion his NDBMH successor John Olds, also an American and a Johns Hopkins graduate, noted that Parsons had “contributed a tremendous amount of good to the Bay and shall never be forgotten.”6 Several years later, following his resignation in 1934, Parsons travelled to China with Canadian Dr. Norman Bethune (1890-1939), where they planned to aid the Communist cause of Mao Zedong. Although Bethune would stay and die in China, Parsons was soon requested to leave; Bethune described him in a private letter as a “drunken bum.”7 In spite of his apparent ongoing addiction to alcohol Parsons became Superintendent of the Washingtonian Hospital in Boston, which treated patients suffering from alcoholism. On New Year’s Eve in 1940, following a divorce from his physician wife, Dr. Malvina Elizabeth Moore-Parsons (1901-58), who also had served at the NDBMH, and soon after the death of Sir Wilfred Grenfell, Parsons was discovered dead of a heart attack in a Philadelphia hotel room. According to his brother, the renowned sociologist Talcott Parsons, he had engaged in a drinking binge. Ironically, Charles Parsons was presenting a paper at a symposium on alcoholism entitled “The Problems and Methods in a Hospital for Alcoholic Patients.”8 His obituary in the Journal of the American Medical Association made no mention of his 20 years of dedicated service to the IGA and Newfoundlanders; his obituary in the IGA official organ, Among the Deep Sea Fishers , made no mention of the circumstances of his death. The Twillingate Sun at the time published a letter from Dr. John Olds, who noted that Dr. Parsons had “died suddenly.” Only the New York Times captured the essence of Parsons’s professional life and the details of his death with a brief notice entitled “Dr. Charles Parsons, Ex-Aide of Grenfell.” 9

THE REPORT OF THE TWILLINGATE MEMORIAL HOSPITAL FOR THE COMMONWEALTH FUND : CONTEXT AND TEXT

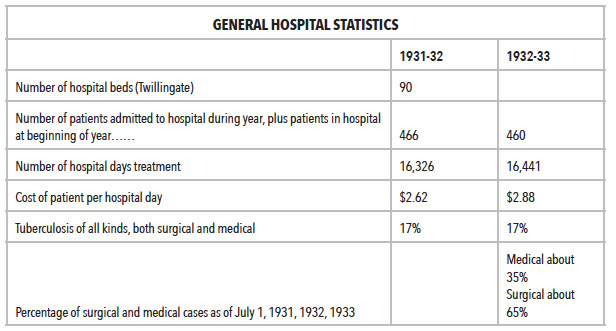

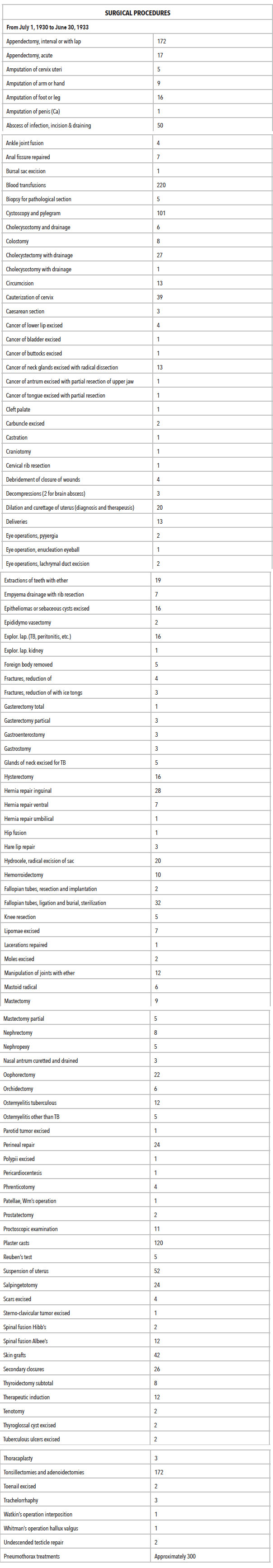

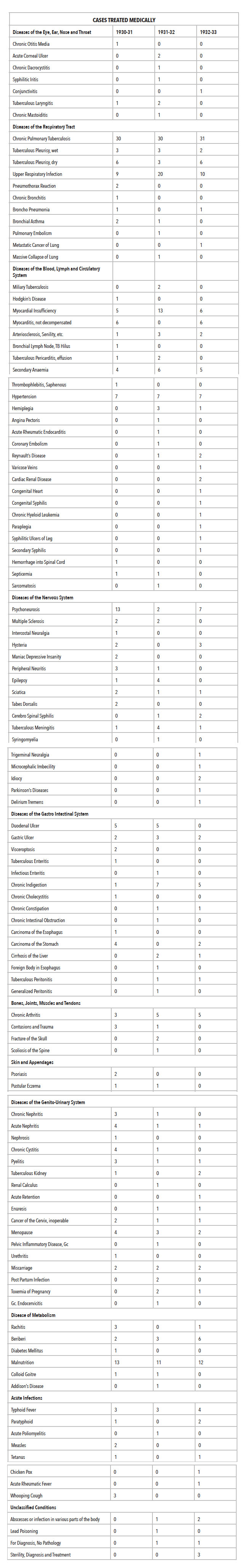

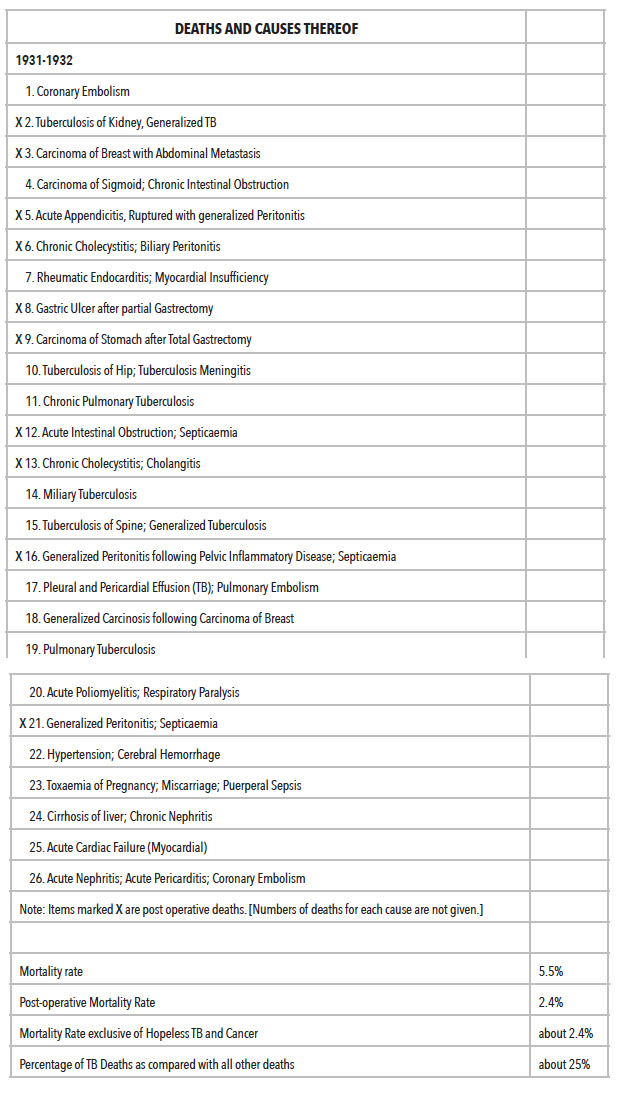

8 The NDBMH had several stakeholders in 1933: Grenfell had an interest in the health and well-being of Parsons along with a complementary concern to maintain the professional reputation of the IGA—both coincided with his personal belief in, and institutional policy of, abstinence from alcohol. As the CF had donated tens of thousands of dollars to support this remote hospital, it did not wish to see this investment jeopardized. And the government, while generally pursuing a policy of benign neglect regarding the hospital, had been allocating a substantial annual grant to support it. Now, with this apparent local crisis due to the unanticipated transition of medical directors, coupled with the larger financial catastrophe that loomed, government officials needed to re-evaluate the NDBMH’s level of support. Extant correspondence between some of these parties during the summer of 1933 and winter of 1934 links Twillingate, St. John’s, Vermont, New York City, and London and reveals much about their respective concerns.

9 Writing in August 1933 to then Prime Minister Alderdice, Grenfell stated that Parsons had indeed taken “refuge in alcohol,” for which he took some responsibility because limited financial and administrative resources had “led me to put on one man’s shoulders more than one man should be called to bear, with the result that unquestionably Dr. Parsons broke down.” Notwithstanding this situation, Grenfell then pleaded that the government must continue to support the hospital and, more revealing, that if there were to be any replacement for Parsons it best be handled not by the government but by the IGA. Perhaps, Grenfell suggested diplomatically, with the Commission government on the horizon it “may lead to new economies and new methods, which we know can insure success in making the North an independent, self-supporting and a valuable asset to civilization, with its fine, Anglo-Saxon people.”10 The government responded, however, by eventually reducing funding to the NDBMH upon the recommendation of Dr. H. M. Mosdell to Sir John Puddester, the Secretary of State — perhaps an unsurprising decision given the shaky administrative shape of the hospital and the dominion’s finances.11

10 Concomitant with this series of communications was another between Grenfell in London and Parsons in New York City, where the latter had been admitted to the Payne-Whitney Clinic under psychiatric care. He openly declared that he was a “nervous wreck and completely knocked out,” but was feeling much better. He then confided that in addition to the strain caused by his onerous hospital duties, a personal crisis towards the end of 1933 exacerbated his condition. Just one month before Parsons’s wife was to give birth to their first child she developed toxemia, whereupon he performed delivery by Caesarean section but with the resultant death of the baby.12 In reply, Grenfell was empathic and emphatic. He wrote:

. . .

I mean every word I have said. I have prayed over it and thought over it. I especially begged [Beeckman J.] Delatour to go down last summer because he loved you.

. . .

Why not regard that as God’s way? God Almighty has to make a better world through imperfect people of whom you and I are part. . . .

I shall look forward to seeing you. I hope you will regard me always as a man who loves you and is indebted to you; but I tell you, both as a friend and brother, that I would abolish at once the idea of ever returning to Twillingate.13

11 Grenfell’s personal selection of Dr. Beeckman J. Delatour (1890-1975) in the summer of 1933 to conduct the site visit, medical audit, and report of the NDBMH was apposite. Delatour was an American physician based in New York City who, like Charles Parsons, had attended Amherst College and also Johns Hopkins medical school (he graduated MD in 1915, and thus was only four years senior to Parsons). More importantly, he was a Grenfell Mission alumnus. Beginning in 1911 when he was a college student he worked in the St. Anthony hospital, and in later years he travelled on the Strathcona and visited Labrador as medical student. As a WOP (Worker-Without-Pay) he came to know Grenfell, ate reindeer meat, and probably also first met Parsons as their work terms with the IGA coincided. Subsequently, Delatour became a director of the Grenfell Association of America; in 1945 he was appointed Summer Medical Director at St. Mary’s River. His wife was also a staunch supporter of the IGA.14

12 Delatour’s Report is thorough, straightforward, and informative. On the one hand, he displayed his understanding of the difficulties of hospital practice in a remote area but remained highly complementary to Parsons and his staff — their performance was that of a “Grade A” hospital. On the other hand, he tried to make clear that the hospital medical superintendent was under great strain and in need of relief. The clinical and administrative challenges that Dr. Parsons faced daily were many and constant; the stress of it was taking its toll. From the Report , we learn much about the occupational hierarchy of the hospital, staff salaries, and duration of work periods; this document is of use to labour historians and economists. The physical plant, condition, and internal and external layout of the institution are also described in detail, thus making the report helpful for historians of architecture. There is also much that social historians can learn from it. Beeckman’s descriptions of the living conditions of fishers and their families and the prevailing attitudes of these people are poignant. The small-mindedness and obstructionism of the dominant merchant class, as described by Delatour, are also revealing.

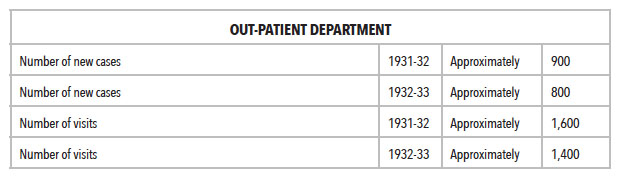

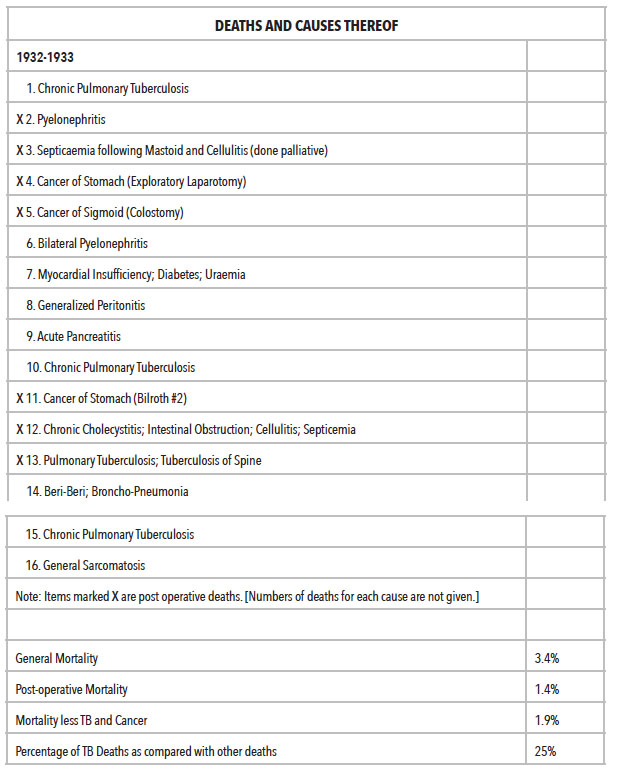

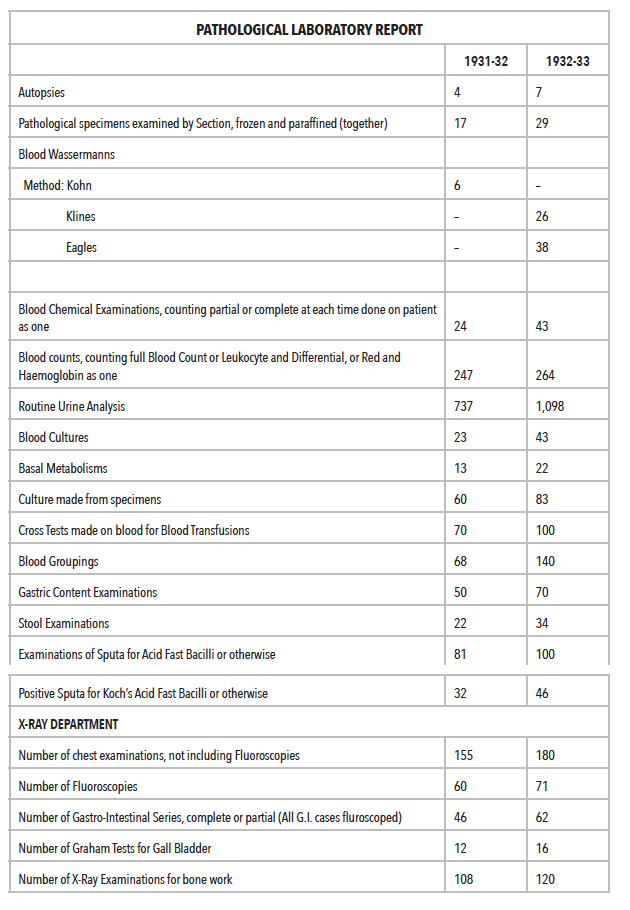

13 For medical historians, this institutional profile or “snapshot” is especially interesting. Delatour’s estimate of the widespread presence of tuberculosis (also referred to as phthisis in the Report ) is alarming, as are the intellectual limitations of many Notre Dame Bay residents concerning public health matters.15 Similarly, his numerical accounts about the range of medical and surgical procedures undertaken at the hospital are especially important. The NDBMH admitted a total of 926 patients from 1931 to 1933; another 3,000 people were treated in the outpatient department for these years. The general mortality rate for the hospital was 4.4 per cent, which was reduced to 2.2 per cent if “hopeless” tuberculosis and cancer cases were not included; the post-operative mortality rate was about 2 per cent. Deaths due to tuberculosis were calculated at 26 per cent as compared to all other hospital deaths; other infections accounted for about the same percentage of deaths. The distribution of medical to surgical cases treated was 35 per cent to 65 per cent, Not only does this material demonstrate how busy the NDBMH was routinely, but Delatour’s level of detail, for example, about the number of laboratory tests requested (all executed by Parsons’s unpaid physician-wife), radiological examinations carried out, and surgeries performed, invokes reflection over a generally prevailing notion that pre-Confederation medical care in Newfoundland was lacking. A contemporary evaluation of the St. John’s medical community by a British administrator who was a member of the Commission of Government for Newfoundland concluded that the capital had a “medical organization which in its human as in its material resources need fear no comparison with that of any other city of its size in the Empire.”16 The same could be said of Twillingate.

14 The copy of the Report of the Twillingate Memorial Hospital for the Commonwealth Fund, housed in The Rooms Provincial Archives Division, is difficult to read as the typing is smudgy; also, it contains several hand-corrected typographical and other errors.17 The transcribed version of the Report that follows has been silently edited to eliminate such mistakes; also, occasionally, an obvious missing word in the original document has been inserted in square brackets.

REPORT OF THE TWILLINGATE MEMORIAL HOSPITAL FOR THE COMMONWEALTH FUND * by Dr. Beeckman J. Delatour 1933

15 Anyone who has been on the East Coast of Newfoundland and is at all familiar with Notre Dame Bay will recall the vast number of small settlements scattered throughout its entire length on small islands in coves and bays.

16 Notre Dame Bay Memorial Hospital is situated on one of two islands on the south side of a harbour formed by these islands that have a population of 3,800 people. Twillingate, as the two islands are known, is well located as to distribution of population [and has] a bay 100 miles across its greatest width. The hospital serves a population scattered along a coast line from Penguin Light east to Cape John, the northwest tip of the Bay.

17 There are no hospitals of any description within a radius of fifty miles of Twillingate. Grand Falls Paper Mills maintain a hospital of twelve beds for their population of 10,000 people. It is seventy miles distant, fifty of which must be travelled by boat and the other twenty miles by railroad. A passenger train on this road runs three times a week. The two nearest hospitals of fifty or more beds are: St. Anthony, one hundred and twenty miles north, travel dependent entirely by water, and St. John’s, one hundred miles south; the fastest means of transportation, coupled with discomfort and inconvenience to any ailing patient, takes at the best time thirty or forty-eight hours.

18 It is interesting to note some of the nearby more thickly populated centers served by the hospital. New World Island and adjacent surroundings some six miles away, including about nine villages, has a population of 3,600. To the east twenty-five miles are Fogo Island, Change Island and vicinity, approximating 5,000. Southeast is the Strait shore including Gander Bay with a population of 2,500 people in a radius of ten to fifteen miles. Lewisporte is directly south thirty miles and with this center of six other localities there is a population of about 2,500 people. The approximate population within a radius of fifty miles of Twillingate is 40,000 people, and during eight months of the year the hospital draws from this area. In this service the longest travelled distance is seventyfive miles. The total winter area from January 1st to May 1st is within a radius of thirty miles and includes 16,000 people.

19 These population figures are compiled from a 1921 census and Latest Voter’s List, and are probably an under-estimate of the present population.

20 To remain in Twillingate a few days, to say nothing of the impression at the hospital, one is amazed at how vastly infected with tuberculosis is this population of 3,500 people. From the inquiries I made from intelligent hospital assistants I am not making too broad a statement when I say every other house has had a share of tuberculosis in some form or another. Either it is a known arrested case or an active pulmonary case, or some kind of bone tuberculosis. There are some variations among towns as to the percentage per population, no doubt, and there may be a number of towns less scourged than Twillingate, but there is no question that this plague is a great handicap to the outports.

21 They say that Newfoundland is its South American and European fish markets because of competition with Norway; also, that Newfoundlanders do not cure their fish properly or by the same methods as the Norwegians. How can such people compete in industry and trade when they are sick? It is said they are lazy and lethargic. The hospital pathologist told me that a few days ago she did an autopsy on a case of a man who died of tuberculosis. He had been working up to three days before his death. His lungs were filled with massive cavitation, cavities of varying sizes and there were only rare areas of normal functioning air cells. Isn’t that sufficient reason to explain their lethargy with people trying to struggle along when disease is so extensively scattered among them? I know that of one cove on Twillingate Island it is said that every home there has tuberculosis in one form or another. What can the best hospital do under such circumstances? They may give them rest, high caloric [diets], fresh air, do phrenectomies or thoracotomies, and after they improved or the case has been arrested they are sent to poorly ventilated homes, to diets that are inadequate, to places of no sanitation and hygiene, only to be reinfected or to infect others, or to break down the protective tissue that was building up under hospital rest and care of many months.

22 Typhoid Fever is far too prevalent in Notre Dame Bay. The people have no conception of what a polluted water supply is. They often dig their wells on the side of a hill below and not far distant from their outhouses. They see no danger in this as long as the water they get appears to be clear. Their cattle are never inspected and they very rarely consider boiling their milk. There undoubtedly are a number of typhoid carriers about the island. Doctor Parsons, of course, never allows a typhoid patient to leave the hospital unless he gets two negative typhoid stool cultures. One man had been at the hospital for some time and the stool could not be cleared of the bacillus. Some indications led to the possibility of gall bladder infection. The man had his gall bladder removed and on culture it gave a growth of bacillus typhosis. After this the stool was free of this infection and as soon as his period of convalescence was over he was allowed to go home. This only shows how carriers who have not been inspected can be around infecting water supplies and can contaminate milk. Neither of these are given the slightest consideration as a possible cause of disease.

23 I was in Twillingate in 1921 for three days and at that time there was an epidemic of typhoid. I remember one woman whom I saw with her doctor in her home in the fourth or fifth week of the disease. During all of her illness she had been up and around every day performing some of her household duties and at this time we saw her she was carding wool. She was determined to be up during her illness. There was no one else to do the work and she insisted she could not go to bed.

24 At that time I remember that Doctor Wood, who is now associated with the Twillingate Hospital, told me of a baby he went to see who could not retain anything in its stomach and was in a bad state of malnutrition. He asked its mother what she fed the baby and she replied, “Doctor, I feeds it chawed bread.” “Chawed” means chewed. She carefully chewed the bread before giving it to the baby but mixed all varieties and species of bacteria with it as she had an advanced case of pyorrhea.

25 These examples show how utterly ignorant are many of these people of hygiene or the transmission of infection. It gives an idea of the problems that cannot adequately be met by the few doctors and hospitals on the coasts. We meet these problems in the cities with heart cases in cold water tenements who have stairs to climb to the third and fourth floors; we have housing problems in cases of tuberculosis. But in the cities we have social services and follow-up clinics and convalescent homes.

26 In Newfoundland there is plenty of fresh air and clear atmosphere, but the people do not know how to use it. Although they are supposed to be hardy and live by the sea, in their homes and in the cabins of their schooners there is little, if any, ventilation. The air of course is very heavy and overheated. Spitting upon the floors is not condemned by the residents, except by a very few, and it has been my experience in Newfoundland not infrequently to see a guest come to his neighbour’s house and spit on the floor many more times than once, so that I was convinced it wasn’t an accident or a momentary [lapse] of memory on the neighbour’s part. Grandma or Grandpa’s cough often goes unnoticed and is never thought of as a possible source of infection to a family of eight or ten children, living with them in a four-room, tightly sealed, overheated home. I had an old lady ask to take a voyage [with] me from Flowers’ Cove to St. Anthony in the Mission yawl. I was taking three or four patients to the hospital. She said she would just like to take a little voyage, despite the fact that she was coughing up large plugs that looked like degenerated lung tissue.

27 The coastal country is badly in need of social service, and in the case of Twillingate it needs the social service work to carry on the results the hospital gets. There is no doubt tuberculosis is the worst problem. Every effort should be made, with every available financial means, to combat it. Investigations as to housing problems, water supply, milk supply, and personal hygiene should be thoroughly gone into. A commission should be appointed to scientifically investigate the problem. Newfoundland will never be able to come back but will fall further behind in her greatest industry, fishing, unless she starts in to tackle the problem of health. In order to increase her power of production she must improve the health of her people. To increase her efficiency she must start to eradicate the prevalence of tuberculosis. It is a big problem; it will take money, thought, and time, but I believe it can be done and it must be done. It is the only salvation of the country.

28 The observations of the hospital and associated plants during my visit of inspection at Twillingate were most interesting to me. It is not the purpose of this report to go into the problems of construction, regarding architectural plans, construction contracts, and funds for buildings, water supply, sewerage disposal, electric lighting, sources of equipment, and many similar items. Suffice it to say I was amazed to see that such a hospital and associated supporting units have built up and developed in the short period of ten years. I can also add that there are no elaborate or unnecessary touches to build up a plain, efficient hospital unit. I do not believe there has been any attempt at overexpansion to meet the present need of location, and I believe that the purpose of the administration is to keep it up to the standard of a Grade A hospital.

29 I wish to thank the superintendent, his assistants, and the general hospital staff for their cooperation in offering me every opportunity to inspect each department; for their eagerness to have open discussions on any questions I wished to ask; for the freedom I was allowed to inspect records and histories; and for their help in compiling statistics that I requested.

30 I made rounds twice with Doctor Parsons; I was present at two major operations; and made a general tour of inspection of the plant, which included the wards, operating room, laboratory, drug room, Out-Patient Department, X-ray department, kitchens, laundry, store-room, ice-house, two cement-lined vegetable cellars, carpenter shop, store-houses, two reservoirs, the hydroelectric plant and motor-power for electricity, the nurses’ home, the cow barns, and the location of the cesspool. In addition to this, a complete tour of all the roads on the two islands of Twillingate was made, which covered a distance of about forty miles.

31 I would like to give a brief description of the general outline of the hospital which is not intended for any architectural opinion but only as an idea of the general arrangement.

32 Notre Dame Bay Hospital is a reinforced concrete block hospital, and fireproof throughout. It is in the shape of a T, is three stories and basement, with a gable roof.

33 The basement consists of a kitchen, maid’s room and bedrooms, laundry, and store rooms for groceries, bulk medicines, and laboratory supplies.

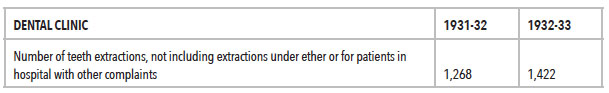

34 On the first floor above the basement are the executive offices, including dining-room, living room, and glass enclosed porch, and small quarters now used by the nurse in charge of the operating room. Also on this floor are the laboratory, x-ray room, two small rooms that can be used as wards, an isolation room, a small room for experimental dog surgery, a drug room for dispensing medicines, and an Out-Patient waiting room with examining and treatment room. Also in [the] Out-Patient department is a small corner reserved for a dental chair for dental extractions.

35 On the second floor are two main wards, one each for men and women. At the end of these wards are glass-enclosed porches, each porch holding four beds, and these were occupied by phthisis patients. There is a small children’s ward, two or three rooms holding four patients each, one private room, one other room that could be converted into a private room, and serving room. The operating room is on the second floor and consists of a main operating room, anaesthetizing room, sterilizing room, and scrub room. From this floor a large uncovered porch extends from the back of the hospital, to which patients can be rolled out in their beds. I should say this could readily hold from fifteen to twenty patients.

36 The third floor is divided into smaller wards and rooms and is under the gable roof, with gable windows. On all floors there is an adequate supply of plumbing and sufficient serving rooms to serve the food properly.

37 The wards, halls and general condition throughout the hospital was clean. The beds appear closer than is warranted by the regular requirements of space. In several instances, patients’ belongings littering the tables and stray bits of paper scattered on the floor helped to give this impression. This was probably the fault of the patients. A rigid routine inspection along these lines would certainly help to dispel the impression this creates. The walls in the halls are somewhat scraped and denuded of paint and show the wear of the time in a busy hospital. When funds are available I believe that a coat of paint would add to the well-ordered appearance. The beds were well-kept. The serving-rooms were orderly and clean. I cannot offer a word of criticism for the operating room. It is well-appointed, with adequate equipment. The surgical asepsis and the general techniques throughout are of the highest standard. The management, teamwork, and esprit de corps is excellent. The laboratory is confined to one room and does not appear to be overcrowded, and is prepared to cover the necessary amount of special technical work for the size of the hospital. There is a doctor in charge of the laboratory who is specially trained for this work, and who has not received any salary to the present, although actively engaged in this work for a year. Double checks on cross tests for transfusions are always made. In tissue work, frozen sections or paraffin preparations may be done. A general summary of the detail work requested by me will be shown.

38 In the kitchen I found a most orderly appearance. Serving tables, meat boards, and everything relating to contact with food was immaculate. The laundry was a busy place, and there I found four or five people actively engaged in work. In addition to hand ironing it is equipped with a large washing machine and a gas-heated rolling ironer.

39 The histories and records of the patients in the hospital are of the highest standard. The histories are carefully and thoroughly carried out and could be used for the compilation of facts in any research work. Careful bedside notes are kept, with complete records of medication, laboratory reports, and operative procedure. The charting is splendidly done. Final and discharge notes are made. In short, all records are carried out in such a way as to be of value for future reference.

40 The x-ray room is equipped with a fluoroscope and x-ray apparatus for doing chest, gastro-intestinal, and bone work, and adjacent to this is a dark room for developing films.

41 The water is adequate for the hospital. The dam for the first reservoir was not built according to specifications and resulted in leakages. Also it has insufficient height to bring the water to the third floor of the hospital. This reservoir now supplies water for the hydro-electric plant which is enough to generate electricity for sterilizing, apparatus in the laboratory, and low voltage electric light. The gas engine has to be used for power to generate enough electricity for the x-ray and also is used at this time of year for two hours to give sufficient power to light the hospital and adjacent buildings. The second reservoir supplies the water for the hospital, nurses’ home, and doctor’s house, and is giving an abundant supply. The water supply is protected by position from contamination.

42 The cattle come from a herd in Prince Edward Island that have been tuberculin tested. No recent bacterial tests have been made of the milk as to count. The two that were made Dr. Parsons said were under the normal required amount. Everything appeared clean and well-kept in the barns. Eggs are sufficient in amount for the patients and are stored for the moulting season in salt vats.

43 The sewerage is carried to septic tanks which are just alongside of the power house at the edge of the harbour water and can offer no source of contamination to others.

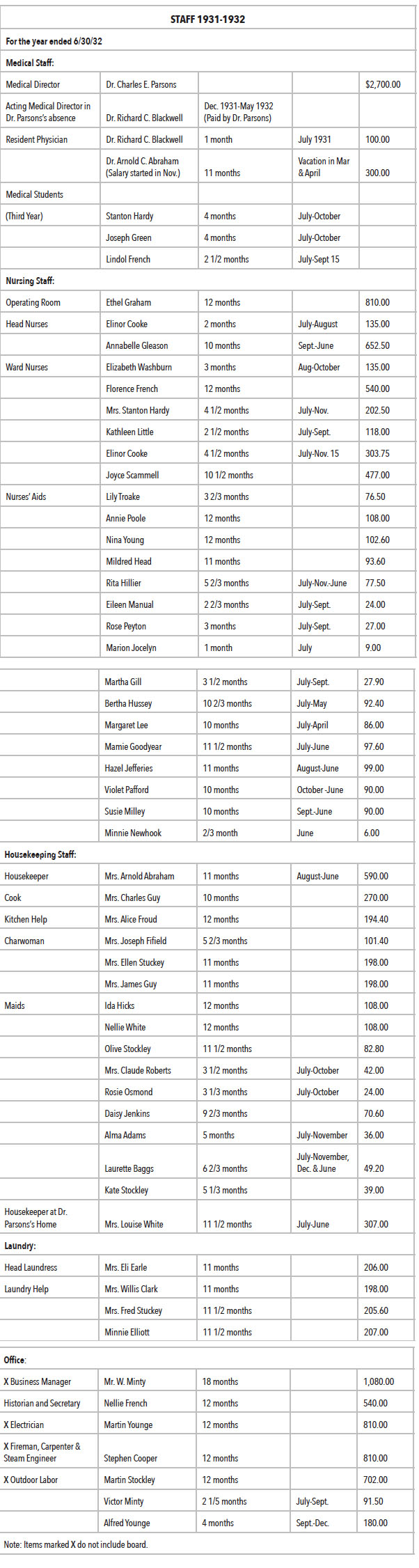

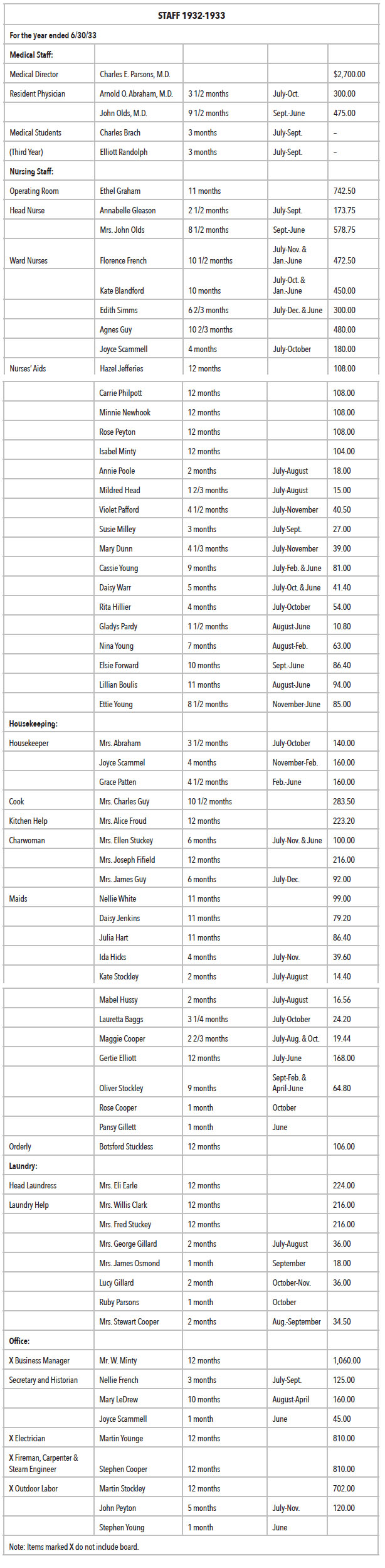

44 Following is a list showing the staff, also detailed statistical reports of the out-patients department, medical, surgical, pathological and x-ray departments.

45 N.B. The large numbers of gynecological cases are due largely to the prevalent use of midwives and consequent poor obstetrical aftercare. They are also due to the fact that a majority of the women are up and at hard work long before involution of the uterus has taken place.

46 There are no specialists, dentists, eye, ear, nose and throat, or bone specialists at Twillingate and all phases of both medicine and surgery are done by Medical Director and House Surgeon. In general, every field of medicine and surgery is handled, with the following exceptions:

- Obstetrics. Only private patients or operative obstetrics.

- Eyes. No cataracts, iridectomies or refraction. Pterygiums and enucleations are done.

- Infectious Diseases. None admitted except Typhoid, except when forced to do so.

- Brain surgery. None, except in emergency for fractures of skull or brain abscess.

47 Doctor Parsons reports that he has yearly urged Government inspection of Twillingate Hospital and its books as he thought it right not only to him but to themselves. This was just as important in the case of increasing the Government grant as in reducing it. If the Government saw fit to increase the grant to meet the required amount of hospital expenditures, it is only right for their protection to investigate the necessity of increased demand, and satisfy themselves as to its justifiability. During the ten years of the hospital’s existence Doctor Parsons states the first visit by any Government official will be made this month by Mr. Trentham, Deputy Minister of Finance.

48 The Government grant to Twillingate Hospital was originally $10,000.00 per year. As the demands on the hospital grew, an increased yearly grant was given until it reached $34,000.00 per year. The urgent need to care for tubercular patients brought such an added burden on the finances of the hospital that Doctor Parsons had to appeal to the Government for further financial aid to care for the tubercular paupers. He made it clear to the Government that he would have to add a new wing to the hospital and make radical changes in the water supply. To obtain those he would appeal to interests outside the country. Before making such an appeal he specified to the Newfoundland Government that he must be assured of some help from them for maintenance of such an addition which would amount to a fairly substantial proportion of the cost of each pauper tubercular patient per day. In partial accordance with his request, the Newfoundland Government gave him assurance to pay $1.50 for each pauper tubercular patient, which would give aid toward the maintenance of the new wing. Accordingly, Doctor Parsons appealed to the Commonwealth Fund and received $50,000.00. He received an additional $10,000.00 from the Newfoundland Government, $6,000.00 from St. John’s and the country in general, and the rest in contributions from the United States, which made a total of from $75,000.00 to $80,000.00. With this money he constructed the hospital addition, a reservoir to take the place of one that was inadequate and previously was unsatisfactory as to construction, supply and position. He also constructed two warehouses and a stone wall as ballast and support to the immediate road leading up to the hospital. These things completed, the Government grant of $1.50 [per pauper tubercular patient per day] began in 1931, a year and half ago. With the previous grant of $34,000.00 a year, this additional pauper grant for tuberculosis brought the amount from the Government to approximately $50,000.00 yearly.

49 This winter he was informed that the $1.50 grant would be stopped and the general grant reduced to $32,000.00. With such a curtailment, immediate economies had to be made. The hospital capacity was reduced to 28. Tubercular joint and pulmonary cases had to be sent to homes that were entirely inadequate for care as to food, general hygiene and general medical intelligence. Large families were exposed to still further tubercular infection. Surgical bone treatment was interrupted in many ways. For one instance, a little boy was sent home with tubercular bone infection of his foot, with special instructions for the bandage to remain on his leg a given length of time. A few days after his arrival home, which was on an island some little distance from Twillingate, the father ripped the bandage from the boy’s leg and allowed him to use the leg without support or protection. In a short time, a month to six weeks, the boy developed severe pains in his ankle with sinus formation opening out through the skin, and an x-ray showed softening and destruction of bone. Here the precious work of weeks and months was undone [and] an added injury had taken place, and this is only one of many such cases.

50 With the reduction in hospital patients, the hospital was over-staffed. This staff was under contract and sufficient in size to meet the demands of caring for additional tubercular cases. To meet this change, it was necessary to ask nurses to take vacations of one or two months in the winter without pay, thus reducing the over staffing and cutting down running expenses.

51 When Doctor Parsons saw Prime Minister Alderdice in January 1933, he was promised a Government grant of $32,000.00 for 1933-1934, plus $4,000.00 if he could obtain an equal amount by subscription outside the country. He then came to New York and requested financial aid from the Commonwealth Fund. Instead of $4,000.00 he asked for $6,000.00. The reason for this additional $2,000.00 was as follows: He had budgeted himself to $46,000.00 for the period from June 1933 to June 1934, which was the minimum amount on which he could run the hospital to his satisfaction and meet the medical demands of the bay, figuring the cost per patient at $2.88 per day. With the general grant of $32,000.00 plus $8,000.00 this brought the amount $6,000.00 under his budget. For this reason he asked for an additional $2,000.00 from the Commonwealth Fund and figured that the other $4,000.00 could be raised from patients and gifts from those about the bay.

52 The directorate of the hospital has been a handicap to the administration, beyond all doubt. I am convinced that the Board of fifteen is too large and is infiltrated with petty jealousies and selfishness, and their breadth of vision is obscured through ignorance. Unfortunately, Doctor Parsons is dealing with the merchant class of the outports of Newfoundland for his board of directors. They are the only ones he could turn to, for the great majority of fishermen have not sufficient education to understand what it is all about. Petty hospital investigations, such as sub-committees to inquire from paid employees into grievances they might have against the hospital, without the superintendent or business manager present, have been urged against the absolute disapproval of Doctor Parsons. In fact, one was carried on with a woman employee without his knowledge beforehand. He did interrupt the secret meeting and proved that her grievances against several people in the hospital were unfounded. Almost immediately this woman resigned. Further, the chairman of the Board of Directors stated at Board meetings that it was impossible to comply with Dr. Parsons’ demand that Mr. Minty (his business manager) and himself be placed on the Board. The reason given was that both were paid servants of the Board. Through Mr. Charles Hunt, the hospital’s lawyer in St. John’s, they were shown they were legally wrong, and both Dr. Parsons and Mr. Minty became members in 1930.

53 If an extra man has been hired for half a day for some minor labor, questions and disapproving discussions arise. Why wasn’t one man chosen in place of another? Or, why wasn’t a south side of the harbor man chosen in place of a north side man? In the question of purchases, it is not the concern of a majority of the Board as to whether material bought in town is the best quality at the cheapest price. Small purchases needed in a hurry may be bought at a nearby store to obviate waste time. Or one store is patronized by the hospital at one time because of the best value received. This repeatedly starts grumbling or innuendoes among certain members because they have not had the benefit of the purchase. In other words, they have a narrow, warped outlook upon the mission of the hospital. They seem to lose the idea of its real purpose, which is the care of the sick for the people of Notre Dame Bay.

54 It looks very much as though they felt it should equally serve as a center for them to do business with. These conditions have been discussed with me at great length by people well informed about the hospital, and I depend for my information here stated upon their frank, open and unbiased discussion. So many petty questions have arisen that meetings of the board of fifteen have convened as often as every week over a long period of time. And yet, when the yearly meeting of the Association took place on June 19th, when the medical and financial reports for the year were to be read and when new directors and a treasurer were to be elected, only nine out of thirty-two members of the Association appeared. Two of these members present were the superintendent and business manager of the hospital.

55 The question arises — what will be the future of the hospital? Can the hospital carry on under the present Board of Directors? Doctor Parsons came to Twillingate with the idea of establishing a hospital. He had a firm belief that he could educate the people to carry on the management for themselves. I believe he sees the absolute futility at such a Board carrying on with the hospital in the event of his inability to continue his present connection, or any other superintendent doing likewise.

56 During my four days at Twillingate, I was greatly impressed, I could say amazed, at the close association of Doctor Parsons with the hospital and the numerous details of the plant. I am sure, I have observed him at the busiest time of the year and I have had an opportunity to see the tremendous amount of work that falls on his shoulders. He is assisted by a resident surgeon who, Doctor Parsons tells me, is a man of excellent calibre, ability, well trained and dependable. Besides this there are two third-year medical students as assistants. Despite these men and the nurses, a great deal of hospital work falls upon him. Of course, the major operating is done or supervised by him. He also assumes routine care and supervision of patients. Besides this, he has important consultations in the Out-Patient Department. The geography and location of Twillingate bring patients over water by trap boat and steamer at all hours of the day, and sometimes at night. Examinations and treatments must often be given shortly after arrival and necessitate the services of the superintendent. Then there are questions about the plant that require his attention. His business manager is a very capable man and is able to relieve him of a great deal of the detail. But I bring this all up to show how saturated Doctor Parsons’ mind, and how fully occupied his life, is with the care of the sick in a ninety-bed hospital and with the administration of the plant. His mind seems to be constantly at work, he enjoys activity, and he is at his best when the work is heaviest. I do not think he realizes how much this all is a part of his life, and how little he is free from it even at home. It seemed to me very rarely that we sat down to eat that he wasn’t called away several times about matters pertaining to the hospital. These do not seem to bother him in the least. Perhaps he might delegate some of the responsibilities more to others. He may, more than I am able to judge. Or it may be that all things in the hospital plant have grown around him as much that he is an integral part of the machinery, and he finds it difficult to separate himself from some of the things he might be spared. His heart is in this work and patients, and his is conscientious to a degree. He has an innate pride in the creation of his hospital unit, but he is disappointed by the realization that the people of Twillingate will be unable to carry on for themselves.

57 The confined work of Doctor Parsons to the general administration, and the worry of finances all over a period of years have been a greater source of nervous strain than he himself realizes. And these, with the difficulties he has experienced with the directors of Notre Dame Bay Hospital, are too much for one man to carry. I think he must realize this for his own good. He should get away from Twillingate for six months every two years, and during that time he should not have the added strain of collecting funds for the hospital. This is vital to his health in order that he may give the best of himself to his work.

58 Under the present conditions, it would be difficult to find a man of any such surgical or medical standards as Doctor Parsons to take his place. No reputable man could accept the pettiness of such a controlling Board.

* Acknowledgement is gratefully extended to The Rooms Provincial Archives Division for permission to reprint this document.