Articles

Alan Caswell Collier (1911-1990):

An Ontario Artist of Newfoundland and Labrador

1 Visiting artists have greatly enriched the cultural heritage of Newfoundland and Labrador, with such sojourners sketching and painting what they could get to and see.1 Historically, their work was both facilitated and limited by the means of transport available to them in the region. Over time these changed remarkably. When the celebrated American painter Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) visited in 1859, he arrived in St. John’s by boat from Halifax and then chartered a vessel to explore along the east coast of the island and as far north as Battle Harbour, Labrador.2 He next sailed down the west coast of Newfoundland before crossing over to Sydney, Nova Scotia. There were few roads in Newfoundland at the time, but, while staying in St. John’s, Church chose to venture overland to Petty Harbour and made a sketch of that thriving outport.

2 From 1898 travel by train across the island from St. John’s to Port aux Basques (where a connecting ferry service to Nova Scotia operated) offered visitors another perspective on the topography of Newfoundland. Eventually, there were also branch rail lines and an extensive coastal boat service (the inspiration of much story, song, and verse) tied to the railway enterprise. The artists who touched in, though, continued to focus their attention on the coastal scenery and seascapes for which the island is justifiably famous.

3 In the 1930s, the English artist Rhoda Dawson (1897-1992), who worked for the industrial department of the medical mission established by Sir Wilfred Grenfell, produced excellent watercolours depicting a variety of locations in northern Newfoundland and coastal Labrador.3 Her base of operations was St. Anthony, where the Grenfell headquarters was located, but she eventually sojourned in Twillingate (with the accomplished Dr. John Olds) and in St. John’s, where she spent several months recording, in picture and word, the life of the harbour.

4 In the 1940s the Canadian war artists who came to Newfoundland and Labrador had access to military transport by land, sea, and air, the last made possible by the bases built by Newfoundland (using British expertise) at Gander and by Canada at Torbay (site of the present-day St. John’s airport), and Goose Bay, Labrador.4 Thanks to Canadian and American defence spending (the United States constructed bases at St. John’s, Argentia/Marquise, and Stephenville), there was a transportation boom in Newfoundland in the decade. Trans-Canada Air Lines (TCA) began scheduled service to St. John’s in 1942 and this welcome development has greatly facilitated travel to and from the island ever since.5

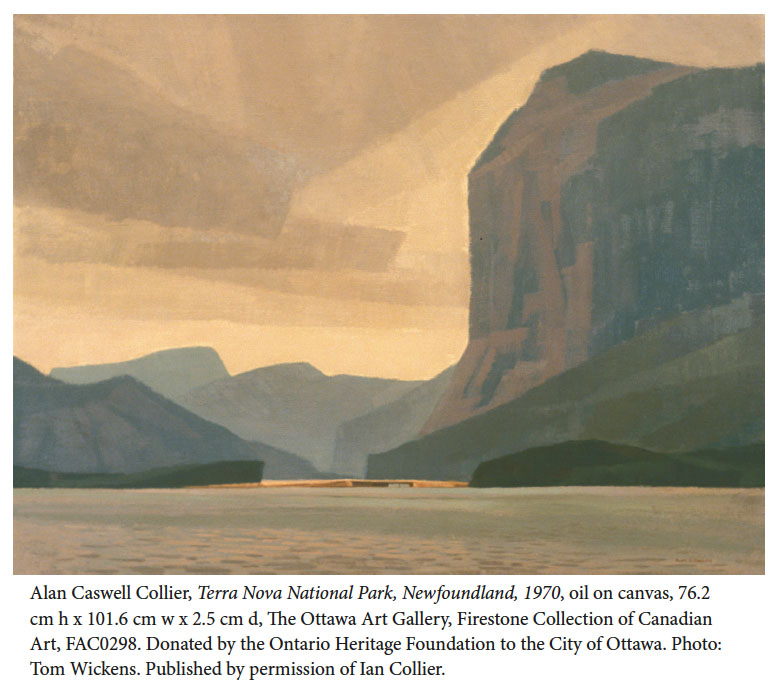

5 When the London, Ontario, artist Clare Bice first visited the new Province of Newfoundland in 1951 (just two years after Confederation), he flew into St. John’s with TCA and then went over the Conception Bay highway, one of the oldest roads on the island, to the Port de Grave/Brigus area, which had been recommended to him by fellow painters for its natural beauty and artistic potential.6 He made the locality the setting for his beautifully illustrated children’s story The Great Island: A Story of Mystery in Newfoundland (New York: Macmillan, 1954), which also refers to Gander, now easily accessible and also on his Newfoundland itinerary. By this time, road building was a major economic activity in Newfoundland, with the construction of the island portion of the proposed Trans-Canada Highway, a daunting task, in prospect. As this highway was pushed across the island (essentially following the route of the railway), it opened up Newfoundland as never before to Newfoundlanders and visitors alike.

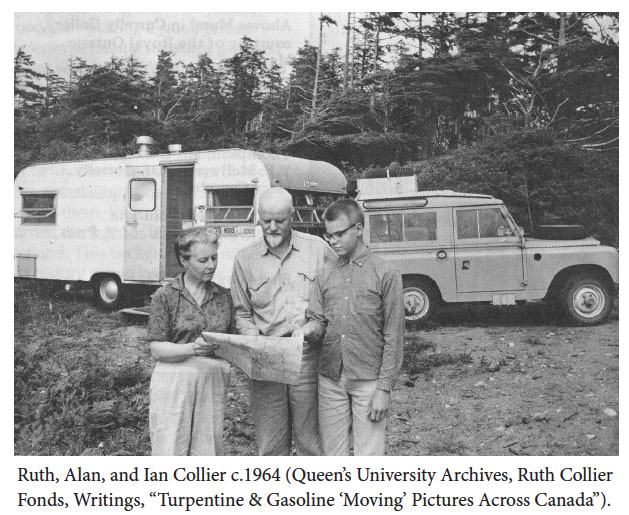

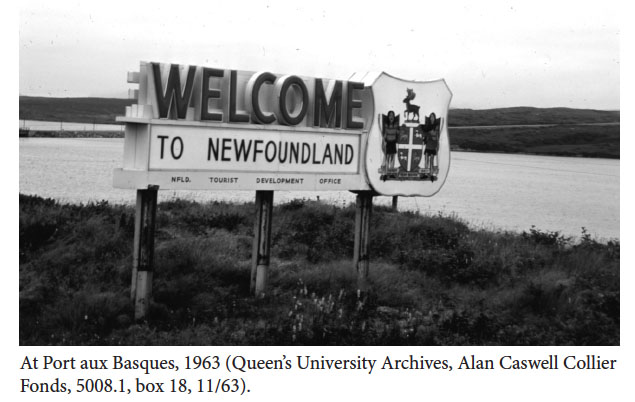

6 Among the early travellers over the full length of the new road were the Toronto artist Alan Caswell Collier, his wife Ruth, and their young son Ian. During the summer of 1963, the Colliers drove from Port aux Basques to St. John’s and back at a time when an artery that would change the face of Newfoundland was still under construction and only paved here and there. Along their bumpy and dusty way, they duly noted the billboard message of the provincial Liberal government of Joey Smallwood, honouring Lester B. Pearson, the Canadian Prime Minister of the day (and another Liberal): “We’ll finish the drive in ’65/St. John’s to Port-aux-Basques/Thanks to Mr. Pearson.”7 In the event, the promise was kept, to the great credit of the visionary planners and builders whose legacy, the “TCH,” is now a defining feature of the province.

7 The Colliers had many family adventures in Newfoundland, and Alan was kept busy with his sketchbook. He was drawn to the rocky shores and coastal vistas of the island and made six more productive visits to the province. The result was a considerable Newfoundland and Labrador oeuvre, now scattered in a variety of public and private collections across the country, most notably in the holdings of The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery, St. John’s, and the Firestone Collection of Canadian Art at the Ottawa Art Gallery. One of his bestknown and most striking Newfoundland pictures is his canvas Terra Nova National Park, Newfoundland, 1970 (see insert) in the Firestone Collection. This work encompasses everything he thought “typical of Newfoundland — the sea, high rocky shore, and a very small evidence of human effort.”8 An established figure in the history of Canadian landscape art, Collier is of particular interest in the art history of Newfoundland and Labrador. His work celebrates the scenic variety of Canada and in this sense classifies him as a nationalist painter. The purpose here is not to theorize — the whole subject of “comefrom-away” artists awaits more interpretive scholarship — but to set his Newfoundland and Labrador work in the context of his career as a Canadian artist. Born in Toronto on 19 March 1911, Collier was the second of three sons of Robert Victor Collier and Eliza Frances Caswell. Vic Collier ran a tailoring business, and Alan inherited an entrepreneurial outlook. Keeping accounts and records and living within one’s means were second nature to him, as were the virtues of sobriety and thrift. In the fall of 1929, having graduated from Harbord Collegiate, he enrolled at the Ontario College of Art (OCA), where he met his future spouse, Ruth Brown, from Brantford. Graduating in 1933 with the AOCA designation (Diploma of Associate of the Ontario College of Art) at the very bottom of the Great Depression and with the family business struggling, he faced bleak employment prospects. That summer he sketched in northern Ontario, acquired a taste for the hobo way of life, and learned to ride the rails. In July 1934, he hitchhiked to Detroit, whence he and a chance companion delivered a car to Los Angeles. From there he hitchhiked to Vancouver, the hobo capital of Canada, where he moved in with relatives. He next went on relief, living from September 1934 to May 1935 in camps for single unemployed men in the British Columbia interior.9 His letters to Ruth from these camps are an excellent source for understanding the harsh circumstances of the dispossessed young in Canada during the Great Depression.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 18 Returned to Toronto and again living at home, he still faced an uphill battle getting started in an art career, and in May 1936 went to work in a northern Ontario mine. In 1937 he enrolled at the Art Students League in New York City and thereafter worked in that metropolis as an advertising artist. On 7 April 1941, having patiently waited out the Great Depression, he and Ruth were married in Brantford and then settled in New York. In 1942, they moved back to Toronto, where Alan worked for Victory Aircraft at Malton and was a union activist. In 1943 he enlisted in the Canadian army and in 1944 was posted to the United Kingdom.10

9 After the war, Collier worked in Toronto in advertising. In 1949, he and Ruth moved into 115 Brooke Ave, North York, where they lived for the rest of their lives (a studio was added to the house in 1955). Ian, their only child, was born in 1950. In 1952, Alan was elected a member of the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA) and, in 1954, became an Associate of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA). He was vice-president of the OSA, 1956-58, and president, 1958-61. In this period, he became a habitué of the Arts and Letters Club, Toronto.11

10 In 1955, Alan was appointed an instructor in OCA’s Advertising Department. This job gave him the opportunity for out-of-term summer travel and he made the most of it. Beginning in June 1956, when they went to British Columbia, the Colliers set out every year for some distant Canadian destination, where Alan would spend the summer sketching and the family would explore. Like many Canadians who had slogged through the Great Depression and served in the Second World War, Alan came to enjoy comparative affluence in the 1950s, and in his case this was turned to artistic and educational purpose. Automobile production leaped forward in a decade of unprecedented economic growth and this was accompanied by major highway expansion. More Canadians could afford cars than ever before, and they now had more roads to drive on. In Ontario, Highway 401, the artery that defines the southern part of the modern province (the name dates from 1952), was in the making, and work was being pushed forward on the Trans-Canada Highway, the new Canadian east-west link, celebrated by Ed McCourt in his The Road Across Canada (Toronto: Macmillan, 1965). As a result of these and other such developments, many Canadian families, now able to afford travelling as holidays, took to the open road, often pulling live-in trailers behind them. For many, the journey perhaps now mattered as much as the destination. The Colliers were in the vanguard of this social change (now with its own rich literature), which Alan was also able to turn to financial advantage.

11 In April 1962, after six summers on the road, he told Don Sims of radio station CJBC, Toronto, that while he and his family were “by no mean pioneers of travelling,” they had “developed a missionary complex about it” and wanted others to “join in . . . [their] enjoyment.”12 “I have tried all kinds of camping,” the experienced Collier explained, “boxcars and ‘jungles’ during the Depression, tenting in the bush for 5 months at a time while working underground in a mine, canoe trip camping, army ‘camping,’ and now this deluxe stuff in a trailer with its own toilet, shower and proper fridge.”

12 “Nobody wanted me for the first 30 years of my life,” he told Gary Lautens of the Toronto Star in April 1963, “[t]hen all of a sudden I was in demand.”13 Though uncommonly gifted, Alan was in many other respects a representative Canadian of his generation — the cohort held back by the Great Depression but which, having served in the Second World War, entered the broad, sunlit economic uplands of the 1950s.

13 Obviously, by the time the Colliers set off from Brooke Avenue for Newfoundland on the afternoon of 13 June 1963, this time pulling their trailer with a new Land Rover, they were seasoned road travellers, with carefully constructed and well-understood roles and practices. Alan did the driving, looked after care, repair, and maintenance, and took time to sketch whenever he found subject matter than appealed to him. Ruth looked after shopping, cooking, laundry, and everything else that made the trailer as much as possible a home away from home. Ian had fun with both his parents, as he absorbed an education in geography that few Canadians of his age could match (while avoiding the rigours of the Ontario classroom in the warm month of June). Both Ruth and Alan wrote constantly and had well-established routines in this regard. On their first Newfoundland trip, Ruth produced an account of their travels — “Rolling Home 1963” — that runs to 127 typewritten pages (Alan contributed a brief section), all but the first four singled-spaced. Alan himself wrote detailed letters to several correspondents in the same diary-like style he had perfected in his many letters to Ruth in the 1930s and 1940s. Among the recipients of his letters were his friends the editor and writer Howard Gerring and his wife Daisy.14 Alan’s letters had much to say about road and travel conditions. At the time about one-third of the Trans-Canada in Newfoundland was paved (in sections here and there), about one-third was being upgraded for paving, and about one-third was rough gravel. On the latter the Colliers would find themselves “travelling at 15 m.p.h. for hours on end.”15 Together with the “fierce hills” along the way, this made for a daunting drive, indelibly remembered by those who did it.16

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 214 On their leisurely trip east, the Colliers stopped in Belleville, Upper Canada Village, and Montreal. From there they drove through the Eastern Townships and across northern Maine to Bar Harbor, where they took the ferry to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, whence they moved on to Halifax and thence to Cape Breton, where Alan sketched. On the night of the 28th, they crossed over to Port aux Basques, which very much reminded them “of the barer parts of the Yukon.”17 From Port aux Basques (they hit their first dirt road when pavement ended after 18 miles), they slowly made their way across Newfoundland, visiting with Anna and Frank Hayward in Grand Falls (Ruth had known Anna years before in Ontario), and arriving in Terra Nova National Park on 2 July. There, thanks to direct federal government spending, the rough and ready Trans-Canada became “a real Banff-type highway with paved shoulders, wide cleared right of way with grassy slopes, a wonderful surface and gentle sweeping flowing grades.”18 At this location Ian set up his pup tent, but for the first time in three years of using it was rained out. He had to retreat into the trailer and to his parents’ double-width sleeping bag. While based in the park, they visited Eastport, Happy Adventure, Salvage, and Glovertown and vicinity. On 4 July they got back on the highway, spending that night at Bellevue Beach and arriving at Gushue’s Pond Provincial Park, near St. John’s, the next day.

15 One of their first ports of call in St. John’s itself was Adelaide Motors, where they had a wheel bearing checked. Based at Gushue’s Pond, where they got to know Newfoundland couple Rex and Gert Andrews and their children, they toured extensively in the St. John’s and Conception Bay areas (Ruth described Brigus as “the Peggy’s Cove sketching spot of Nfld.”19 ) and along the Southern Shore. Alan found much to sketch, and at Bay de Verde Ruth was inspired to make her own drawing. On 16 July, Ian’s Ontario report card turned up in the mail awaiting them in St. John’s. On 17 July, they headed west again and spent more time in Terra Nova Park and vicinity before moving on. From Deer Lake they headed up the challenging Hall’s Bay Line and explored Bonne Bay, eventually touching in at St. Anthony, Flower’s Cove, and Roddickton (where they visited with the family of Scott Fillier, the top student in Alan’s 1963 OCA class in advanced illustration).20 On the Great Northern Peninsula, Alan was much taken with the regional use of the word “wonderful,” as in “wonderful cold” and, in relation to the sea, “wonderful rough.”21 More exploring followed as they headed back down the west coast. Arriving on 16 August at John T. Cheeseman Provincial Park, near Port aux Basques, they next made a side trip to Rose Blanche. After more local touring from their base at Cheeseman Park (they all went to Wreckhouse and Alan and Ian went to Cape Ray), they crossed over to Nova Scotia on 21 August aboard the MV William Carson and landed back in Toronto on 1 September. For that time, their Newfoundland travels were extensive and adventurous. Above all, the trip gave them an appetite for the province and a strong desire to return there. Their 1963 Christmas card featured a sketch of Flower’s Cove.

16 Writing from Port aux Basques on 18 August, Alan told the Gerrings that there had been “so few tourists in Nfld.” that the people stared at them and had “yet to learn that the tourists come to stare at them.”22 Beards — Alan, who had red hair as a young man, had long sported one — were a particular attraction: “As I have remarked before, the more rural the people are, the more they find beards hilariously funny. I sure kill them in this province, especially teen-aged girls. They point and burst into gales of laughter. Civilization has reached most of Nfld. now so that teenagers are just about the same as any place else.” The roads, he reported, were the worst they had seen in their many travels and, because of political corruption, it was unlikely that the Trans-Canada would be paved in the province by the announced objective of 1965. “The roads are so bad here that people ruin tires by driving too fast with heavily loaded cars. . . . You get potholes so deep that you feel you are running on a series of bath tubs. It is great in the rain when the holes are full of water and you can’t tell how deep they are.” Thanks to a 27 July Maclean’s feature article about the Collier family’s Canadian travels, which had included a picture of their Land Rover and trailer, their vehicle was widely recognized and this led to “some pleasant conversations.”23 At Terra Nova National Park, where the office staff had an issue of the magazine on hand and showed it about, they had “a constant stream of visitors cruising by, or stopping in front of us.”

17 Overall, the story of the summer was that they had been received as “decided oddities.”24 Many people with whom they had chatted couldn’t understand why they had come to Newfoundland: “They assume that we are native sons who are paying a return visit or else are coming to visit relatives. Except for American service men, at least 98% of the visitors from the mainland would fall into those categories. They think we are nuts when we explain why we came.” Nor was the much-vaunted Newfoundland reputation for hospitality much in evidence:

An exception to all this came one day when Alan was sketching at Sandy Cove, Bonavista Bay, near Terra Nova Park:

18 In a circular letter written on 10 July to his friends Herbert Palmer, A.J. Casson, and others, Alan offered these impressions of the Newfoundland social scene:

19 Against this backdrop, sketching posed its challenges and sometimes had to be abandoned, though both artist and host community could also loosen up:

To help matters along, Alan, who had a knack for invention and cutting corners, made adjustments:

20 Description of the different ways of social behaviour they encountered in Newfoundland is likewise a prominent feature of Ruth Collier’s lengthy day-byday account of the trip, which is sprinkled with ripe comments about the province and its people. “More boulder strewn country,” she wrote on 7 August, “made me realize that this is a country, not only of picket fences & wind but of boulders. Boulders strewn across the barrens, boulders in streams and boulders along the shore.”28 An especially memorable moment during the trip came the next day, at Woody Point, Bonne Bay, when they had a chance encounter with Farley and Claire Mowat, who at the time were living in Burgeo, Newfoundland. Claire Mowat recognized Alan, having been a former pupil of his at OCA. A lively conversation ensued, and Farley autographed Ian’s copy of The Black Joke (Boston: Little, Brown, 1962). The little group, Ontarians all, then enjoyed a lengthy lunch together at a grassy spot near the foot of a hill that Ruth called “the struggle.”29 According to her account, the lunch “was a wild affair,” with the Colliers contributing two loaves of bread bought in Woody Point and the Mowats sharing tins of Vienna sausages and sardines.30 Inevitably, the talk turned to provincial politics, with Mowat leaving no doubt about his negative opinion of Premier Smallwood and the provincial Liberal government. Describing Mowat as “a Smallwood-hater,” Alan himself compared the Newfoundland leader to Huey Long and wrote that the “graft and crookedness of Joey’s boys” made Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis “look pretty clean by comparison.”31

21 As the party broke up, the Mowats tried to persuade the Colliers to park their trailer in Bonne Bay and come with them to Burgeo but this invitation was a non-starter, though there was much talk of the Colliers returning the following year and spending a couple of weeks at the Mowats’ south-coast retreat, while Farley and Alan worked together on a book. Nothing came of this. “Farley and I got on beautifully,” Alan wrote, “because we are both troublemakers but he, of course, is a pro while I just fiddle around at it. His ‘People of the Deer’ made the H[udson’s].B[ay].C[ompany]. and the Dept. of Northern Affairs hate him and things he has written and said in Nfld. have made Joey swear to shoot him on sight.”32

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3 Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 422 A few days later, at Barachois Brook campground, the Colliers got another earful about Smallwood, this time from the hirsute Harold Horwood, Mowat’s friend, prominent Newfoundland writer, and former political associate of the Premier. Alan’s account of this exchange ranged widely over Horwood’s crusading career:

Based on what they saw and heard during the summer, the Colliers left Newfoundland with a decidedly negative opinion of Smallwood and of Newfoundland public life generally.

23 Whatever the value of their recorded impressions of the province, Alan accomplished much artistically on the family’s first Newfoundland visit, in which they covered almost 6,000 miles on the island. Opinion is one thing and art another, and the understanding of the former may have nothing whatever to do with the latter. Interesting though the Colliers’ musings are, it is Alan’s pictures that matter. Like music, art may be illuminated by biography but is separate from it. In company with many other artists who have ventured onto the shores of Newfoundland, Alan was an artist of the place rather than the people. As detailed in Ruth’s account, Alan spent many productive hours off by himself sketching (he did not sketch on the eastward journey across the island in order “to get an idea of the general layout”35 ), and he returned to Toronto, as was his annual practice, with many sketches to work up in his studio. He kept an itemized record of his artistic output (including disposition), and his 1963 Newfoundland list has 64 entries, with many pieces recorded as “sold” and others marked “destroyed.”36 He also added dozens of photographs to his growing collection. Some of the paintings, one a depiction of Cape Ray, went to the Mowats in Burgeo (shipped to them via Halifax ship brokers Rowlings Ltd. after the CNR — to Farley’s great annoyance — had refused to value the crate at more than $50 for direct shipment to Burgeo because it had no agent there and the crate “would be left unattended on the wharf”).37 Altogether, Alan’s imagination had been stirred by Newfoundland, to which he would return, and he had found a new outlet for his burgeoning talent.

24 In the 1960s, with Canada continuing to prosper and Toronto a banking and financial hub, Collier finally became what he had wanted to be since the 1930s: an independent, full-time, self-supporting artist. In 1964, he had a one-man show at the Charles & Emma Frye Art Museum in Seattle and the next year was named Honorary Treasurer of the RCA. In 1965 he gave a speech on the traditions of Canadian landscape art. The occasion for this was an exhibition, which he was asked to open, at the Sigmund Samuel Canadiana Gallery, Royal Ontario Museum, sponsored by the C. W. Jefferys Chapter of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE). Jefferys (1869-1951) had been a prominent Canadian artist, illustrator, and writer and the show featured work by the nineteenth-century landscape artists William Armstrong and F. H. Rowan, acquired by the museum’s Canadiana gallery with the help of the IODE chapter. At a time when “fashions in art” were changing “overnight,” Collier cautioned, it was necessary to “look frequently to our foundations — to our roots.”38 He quoted approvingly an article in Canadian Art by the American art critic Clement Greenberg, “the darling of the avant-garde, — the writer who named ‘Abstract Expressionism’, — the prominent art movement so recently gone out of fashion — [and] the promoter of the exhibition seen in the Art Gallery of Toronto a year ago, — ‘Post Painterly Abstraction.’”39 In this article, Greenberg had written that his interest in Canadian art had been awakened not by abstractionists JeanPaul Riopelle and Paul-Émile Borduas but by Goodridge Roberts, whose work had then led him “to know and relish the Group of Seven, [James Wilson] Morrice, [Maurice] Cullen, Emily Carr, [David] Milne, [Jean-Paul] Lemieux, . . . and quite a few other Canadian landscape painters.”40 “I do not want you to feel,” Collier told his audience (perhaps tongue in cheek), “that I am quoting Greenberg as an attack on representational art but quoting him to bolster my belief that landscape painting is not dead and that we owe a profound debt to those who have gone before us.” That landscape art was thriving in Canada was “due not only to the rich soil of our country but as well to the strong roots — roots that bear the names Armstrong, and Rowan, and C. W. Jefferys.”

25 In 1966, Collier was granted leave by OCA for the academic year 1966-67, on the understanding that he would return to his college duties at the end of that time. This experiment proved such a success, however, that he decided to leave his position there. “You must know,” he told Principal Sydney Watson on 20 March 1967, “that over the years I have thought of myself primarily as a painter. I have not sought a life that would make me the most money but one that brings the most satisfactions to my family and me. This past year was an experiment; to concentrate on painting to the exclusion of all other incomeproducing activities. The satisfactions have been immense and are, I believe, reflected in my current exhibition — and I do not mean from the standpoint of sales.”41 He asked to be relieved of his commitment to return to OCA and this request was granted, his resignation being accepted “with considerable regret.”42

26 Alan went from strength to strength as an independent artist. In 1967, he was awarded the Canadian Centennial Medal and the next year, drawing on his extensive experience as a hardrock miner, completed a mural on mining in Ontario for the new Macdonald Block at Queen’s Park, Toronto.43 In August 1967, he told Corinne Noonan of Edward Parker Public Relations Limited, who was collecting information to bolster the nomination by the RCA of nine academicians (Collier included) for the recently instituted Order of Canada, that he was “primarily a painter of the Canadian landscape and underground mining subjects” but did “some commissioned work in the portrait and mural field.”44 Describing himself as “a long-time believer in the Canadian landscape,” he explained that he had “travelled from the east coast of Newfoundland to the west coast of Vancouver Island and to the Yukon” in order to paint. His work was represented in the permanent collections of the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa), the Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto),45 the Hamilton Art Gallery, the London (Ontario) Art Museum, the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery, the Frey Museum in Seattle, and seven universities: Victoria (Victoria, BC), British Columbia (Vancouver), Trinity College (University of Toronto), Queen’s (Kingston), Sir George Williams (Montreal), Loyola (Montreal), and Mount Allison (Sackville, NB). Through his executive work for the RCA, the OSA, the Art Institute of Ontario, and the Arts and Letters Club, he had devoted a “good part” of his time to “the activities and welfare of . . . fellow artists.” He belonged to the Audubon Society and the US National Parks Association “[i]n the interests of conservation” and to the World Federalists “[i]n the interests of peaceful coexistence.”

27 In a presentation entitled “Progressive Innovation[:] The Artist’s’ Viewpoint,” prepared for a 1968 seminar on the topic “Are Art Galleries Obsolete?” Collier explained his philosophy of art at this stage of his career.46 Artists and galleries, he argued, should “be judged by their influence within their fields, not by the fashions” they followed. Public galleries had to “display well-conceived progressive innovations, — or die.” On the other hand, if they showed only such work, they would “just as rapidly” be killed off: “All fields must be explored and exploited but not any one field exclusively.” The curator of contemporary art in a big public gallery “must know the clichés and be able to peel away the abstruse and pseudo-intellectual verbalizing.” A sense of humour would also be helpful — in relation, for example, to the giant hamburger47 on display in the Art Gallery of Ontario, a piece that heralded the arrival in Canada of pop art:

The public gallery should be like a Pied Piper, “playing an inviting tune while surrounded by its people, — pushing some ahead of it, pulling others, but never running ahead of those willing to study and eager to follow”:

Every gallery had to answer the question posed by Harold Rosenberg in The Anxious Object: Art Today and Its Audience (New York: Horizon, 1964): “Am I a masterpiece . . . or an assemblage of junk?”48

28 Alan also expressed firm opinions regarding the business side of art. He was a strong opponent of the American war in Vietnam, but when he was approached by a Toronto anti-war group to donate a picture to be auctioned in support of its work, he said no, sending a cheque instead:

Though a radical in some respects, Alan also was his father’s son and had a good eye for double-entry bookkeeping. When asked in 1968 to recommend for purchase the work of a couple of young artists who could use help, he gave a characteristically blunt reply: “There are no young artists that I could recommend, that need a leg-up these days. If they have any talent (and even if they don’t) there seems to be all kinds of grants and scholarships. It’s the over-35s that need the help.”50 From this cohort, he recommended the work of William G. Roberts and Gordon Peters. Like many artists of his generation, Alan had a small-business mentality and was positioned historically between a Group of Seven establishment and a rising cohort of artists who looked to government programs for support.

29 Commercially, Collier was now well established in two galleries: the Roberts Gallery in Toronto and the Kensington Fine Art Gallery in booming Calgary.51 He also enjoyed the patronage of O. J. (Jack) and Isobel Firestone, important collectors of Canadian art (O. J. Firestone taught economics at the University of Ottawa).52 In March 1969, a show of Alan’s work at the Roberts Gallery numbered 105 pieces, of which 88 were hung for the opening. Of these, 56 sold on the opening night and, as Alan explained to his brother Bruce and sister-in-law Mary in Edmonton, he had to scramble to keep up to the demand:

Ultimately, 89 sales realized $25,255, while five other items “out on approval” stood to realize another $2,900.55 Whereas Alan had sold 35 per cent of his 1960 and 1961 sketches, he had sold 75 per cent of those done since then. When asked about these figures at a lecture, he attributed the difference to “a couple of factors” — and then caught himself from making a blunder:

With some of the proceeds of the highly successful 1969 Roberts show he bought a winch for his current vehicle (a GMC Suburban) and a Hasselblad camera. Obviously, he had made no mistake when he gave up his day job at OCA.

30 In 1969 the Colliers again made Newfoundland their summer destination, but Ian, who had begun studying mechanical engineering at Queen’s the previous fall, stayed behind; following his father’s footsteps into the mining industry, but not underground, he had a summer job at the Griffith Mine near Red Lake, Ontario. This time, to meet the requirements of the Gulf ferry, the Colliers’ vehicle and trailer measured 38.5 ft. (as compared with about 33 ft. in 1963) and they were able to drive from Port aux Basques to St. John’s over a fully paved Trans-Canada Highway. As always, both Alan and Ruth wrote detailed accounts of their travels, which included an extensive trip along the Labrador coast aboard the Nonia, leaving from St. John’s on 20 July and getting back there nearly three weeks later.57 On this voyage Alan took 635 photos and made good use of a tape recorder he had brought along; like many visitors to Newfoundland and Labrador, he was fascinated by the speech of the region and wanted to record examples of it. Alan’s list of pictures from the trip numbers 112 items.58 In St. John’s, he got to know Peter Bell, the curator of Memorial University’s art gallery and a key figure in a now dynamic provincial art scene. Arrangements were made between them for an exhibition of Alan’s work in the Newfoundland capital and this opened at the Memorial Gallery on 11 September 1970.59 Alan and Ruth flew in for the occasion.

31 The show, which ran in St. John’s until 4 October and then circulated to other centres on the island, consisted of “framed drawings, 12” x 16” oil sketches, and various-sized paintings.”60 Three-quarters of the work had Newfoundland or Labrador subject matter and included Terra Nova National Park, Newfoundland, 1970, which Alan had specially executed for Jack Firestone. Ten items from the 1970 show were sold, and three were kept in St. John’s for rental by the gallery. The leading buyer was Lord Taylor, the president of Memorial, who acquired seven pictures for the university’s collection. Six of these were of Newfoundland scenes (At Topsail, Over Bonavista Bay, Bell Island, C. B., Portugal Cove, C. B., Point Verde, Placentia Bay, and Near Clarenville) and one of Cartwright, Labrador.61Across the Narrows sold to a private purchaser for $550.62 Another private sale was of Woody Point, Bonne Bay, a location that would attract many other artists following the establishment of Gros Morne National Park Reserve in 1973. In November 1970, Alan told Firestone that the show had “looked quite handsome” in the St. John’s gallery (located in the city’s Arts and Culture Centre) and that sales had been “well above” his expectations.63

32 In the 1970s and 1980s, Collier, who turned 60 in 1971, continued to prosper as an independent artist. His annual cycle of travel and work was now well established and his pictures were in demand. In December 1970, L. Bruce Pierce of Norflex Limited, Toronto, who owned a large work by Collier, tried to arrange a spring visit for himself, his wife Anne, and Alan and Ruth to the American artist Rockwell Kent, but this fell through because of the latter’s frail health.64 The controversial Kent (in 1967 he had received the Soviet Union’s Lenin Peace Prize), who had sojourned in Brigus, Newfoundland, in 1914-15, had been a formative influence on the young Collier. According to Pierce, Alan continued to find inspiration in Kent’s protean oeuvre and believed that the American had been a major influence on Lawren Harris and other members of the Group of Seven. “He [Collier] DEEPLY admires your social/political stand,” Pierce told Kent: “He shares many of your strong political feelings. He told me that he regretted the fact that he had never spoken out on these essential matters as you have. In a sense, physically and verbally living with the Establishment, although in his soul and deepest thoughts, living a life far to the left. He is most sensitive to the compromise he has made and this makes your life stand out as a beacon.”65

33 None of this, of course, held Collier back in his career, with 1971 being a typically busy and productive year. On 16 March, the Oshawa Art Gallery opened a retrospective of his work and this was followed by a show at the Roberts Gallery, which ran from 30 March to 10 April. On 1 September, the London, Ontario, art gallery also put on a show of his work, which ran until 3 October. This was organized by his friend Clare Bice, the head of the London gallery, with whom he often shared the experience of a fall gathering of Ontario artists at Combermere. Like Collier, though conservative in many respects, Bice was also something of an outsider. “I see that you have missed meeting up with Rockwell Kent (who was also an influence on me),” he told Collier in one letter, “but I expect you will still have some chats with him in the next world when you’re both on coffee breaks from shovelling coal. I now realize how alike you are/were — prickly and difficult and always betting on the wrong team.”66 In the same missive, having recently served on the jury for the RCA’s annual show, Bice commented that “there was certainly far more intolerance among the avant-garde than amongst us straights.” This observation would have been well received by Collier, the quintessential outsider/insider.

34 In 1972, Alan spent 11 weeks sketching in the Arctic aboard the icebreaker d’Iberville and in 1976 made his fourth visit to Newfoundland, where he and Ruth now had many contacts and were well known in the provincial art world. As always, their travels were duly recorded and the number of pictures undertaken by Alan duly logged (in this case the number was 125).67 In 1978 he returned to the Arctic, spending five weeks aboard the icebreaker John A. Macdonald. Another visit to Newfoundland followed in 1980. On this trip, thanks to arrangements made by Jim O’Rourke of the British Newfoundland Development Corporation (Brinco), they did another Labrador tour, this time by air, flying into Goose Bay at their own expense and then on to Melody Lake Camp and the northern Labrador coast on company aircraft.68 On this adventure, Alan took about 200 photos and Ruth another 70. Alan’s log of pictures from the 1980 trip to the province recorded 107 items.69 In 1981, on a visit to Alberta, he and Ruth enjoyed the hospitality of Jack Gallagher of Dome Petroleum and his wife Katie, a get-together that was indicative of just how far he had come in life since his days as a relief stiff in western Canada in the 1930s. Asked by Gallagher for his ideas about how Canada could be kept united, Alan ventured the following:

Ottawa’s “elected members, plus the mandarins” needed to broaden their horizons and “to meet all kinds of people in all parts of the country and to understand their joys and their discontents.” This was the way forward for the country.

35 In 1960, always ready and anxious to defend artistic freedom, Alan was active in his capacity as president of the OSA in defence of Toronto artist York Wilson. Wilson’s right to work on a mural he had been commissioned to paint for the O’Keefe Centre, then under construction (it opened on 1 October 1960), was challenged by the International Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators and Paperhangers; the union claimed jurisdiction in the building over “all painting done on the walls or anything applied with adhesives.”71 Thanks to good legal advice — future Chief Justice of Canada Bora Laskin, at the time a faculty member at the University of Toronto, played a behind-the-scenes role in this fracas72 — the Brotherhood backed off and all was well artistically. The mural — The Seven Lively Arts (measuring 100’ x 15’) — was duly completed by the embattled Wilson (who had two assistants) and is the centrepiece of the foyer of the building. In 1984, Alan was just as quick to support Toronto sculptor Joe Rosenthal when the city council’s Selection Committee for Public Art rejected his maquette for a public memorial to the Chinese nationalist leader Sun Yat-sen.

Thanks to community endorsement of his work and support from fellow artists like Collier, Rosenthal prevailed and the statue was duly erected in Riverdale Park — a monument to artistic freedom as well as to Sun Yat-sen.

36 Alan also acted as a mentor to Newfoundland-born-and-bred artist David Blackwood, who had been a student at OCA when he had taught there. In 1978, on a temporary basis, Blackwood took over the work of vice-president of the RCA following the resignation of Blake Millar. When he was next urged by architect John C. Parkin to succeed him as president of the association, Blackwood looked to Collier for advice. Alan’s response was typically blunt. “You would be crazy,” he told Blackwood, “to accept the presidency of the RCA — any creative artist would be crazy to do so. Even if there was a terrific director to run the business end, it would take too much of your thinking time — time in which you should be thinking about your own work.”74 Moreover, the RCA was now mainly in the business of conferring honours and acting as a gobetween for the “various disciplines and various geographical divisions” of the country. Canadian Artists Representation, an assertive new organization formed in London, Ontario, in 1968 in which Alan was active, had “taken over most of the things that the academy should have done years ago — fees for exhibiting, tax problems, Copyright, and so on.” Both the Academy and the OSA had been “fatally weakened by thinking only of exhibitions and social standing” and eschewing “nasty, mundane economic problems,” lest the feelings be hurt of “those in power in Ottawa or in Queen’s Park,” the people who really counted. Blackwood welcomed this response, which exemplified Alan’s understanding that, as the cultural agencies of the state had grown in power and influence, old Canadian arts institutions had been hollowed out.

37 In 1984, Alan’s Terra Nova National Park, Newfoundland, 1970 was included in an exhibition of the Firestone art collection, which toured a number of British and European centres. Jack Firestone reported to Collier that Don Jamieson, Canada’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom and a Newfoundlander, was “particularly proud” of this picture.75 That year, eight of Alan’s pictures from the Firestone collection were chosen by the Ontario government to be shown at Ontario House in Brussels for two years.76 In 1986, Alan and Ruth made their sixth visit to Newfoundland; in 1989, they went there for the seventh and last time. On these trips they followed their usual routines of visiting, writing, and sketching and Alan was his usual productive self. His list of works from the 1986 trip numbered 27 and from the 1989 trip 86.77 Subsequently, his health declined and he died at North York General Hospital on 23 August 1990.78 A funeral service was held at the North York chapel of the Trull Funeral Home and his remains were cremated. In his introduction to “A Tribute to Alan Collier,” an exhibition held by the RCA in 1991 in honour of one of its most accomplished members, Jack Wildridge of the Roberts Gallery observed that in eastern Canada “the rugged shorelines of Newfoundland” had been Alan’s forte. 79 And indeed they had been.

38 In 1992-93, Ruth Collier, who had kept Alan’s many letters to her in the 1930s and 1940s, donated the Alan Collier Fonds to the Queen’s University Archives in Kingston, Ontario. The collection, which came in four accessions, is extensive and exemplifies Alan’s business-like approach to his career and his and Ruth’s flair for intimate correspondence, travel description, and recordkeeping. The collection is an important source for understanding the art history of Newfoundland and Labrador and includes the many photographs Alan took in the province. The latter constitute a visual record through a period of sweeping social and economic change and await a digitization project to make them more generally available. Ruth Collier died in Toronto on 19 July 1993. Since February 2012, researchers interested in Alan Collier’s career have also had the benefit, again at the Queen’s Archives, of the Gerring-Collier correspondence collection, which includes many letters from Alan to Howard and Daisy Gerring about the Collier family’s road trips back and forth across Canada. The Roberts Gallery in Toronto (“the oldest fine art gallery in Canada”) continues to deal in Collier pictures, which are on a rising tide of value. In 1982, the Toronto writer and social activist, June Callwood, welcomed a proposal from Collier that she write his biography — “I do not want an art book, I want a book about an artist who has led an interesting life” — but this project was not realized.80 In 1988, in recognition of his many contributions to Canadian art, Alan was made a Fellow of the OCA.

39 Alan Caswell Collier was perhaps the leading light in a group of central Canadian artists who found inspiration in Newfoundland and Labrador in the 1950s and 1960s. Their number included Clare Bice (1909-1976), Franklin Arbuckle (1909-2001), George Pepper (1903-1962), and Kathleen Daly Pepper (1898-1994). They knew one another, belonged to the same art organizations, and had a gathering place in the Toronto Arts and Letters Club. Inevitably, they brought cultural baggage to the province, which often surprised them by its social and economic difference. But they were artists rather than sociologists, and, in the long run of history, it is their art that matters. Individually and collectively, their efforts added lustre to the artistic inheritance of Canada and its tenth province.

Acknowledgements: I am grateful for the assistance of Dr. Melvin Baker, President’s Office, Memorial University, St. John’s; Jock Bates, Victoria, British Columbia; Ian Collier, Kingston, Ontario; and the staff of the Queen’s University Archives, especially Heather Home and Susan Office. Photographs from the Alan Caswell Collier Fonds and Ruth Collier Fonds, Queen’s University Archives, are published by permission of Ian Collier.