Articles

William Ford Coaker, the Formative Years, 1871-1908

1 Although Sir William Ford Coaker (19 Oct. 1871–26 Oct. 1938) became one of Newfoundland’s most prominent and controversial figures (as a labour leader, journalist, politician, and businessman), little is known of his life before 1908, the year in which he founded the Fishermen’s Protective Union (FPU). 1 In his 1927 biography of Coaker, Smallwood presents an image of a man emerging out of the “Northern Bays of the Country” to form a fishermen’s union. 2 The only major scholarly study of Coaker is McDonald’s 1971 doctoral thesis (published as a monograph in 1987), which deals with Coaker’s and the FPU’s involvement in politics between 1908 and 1925; it provides a brief, general overview of Coaker’s pre-1908 life, as does a 1975 publication by McDonald. 3 There are also brief glimpses of his pre-1908 life in John Feltham’s 1959 MA thesis as well as in S.J.R. Noel’s 1971 seminal study of early twentieth- century Newfoundland politics. 4

2 This sparsity of information on the early life of one of Newfoundland’s most outstanding historical figures is surprising. This essay attempts to remedy that situation. It provides a comprehensive account of Coaker’s life up to the first days of the FPU. The next section provides a brief profile of Coaker and the subsequent sections then proceed in a chronological fashion.

BACKGROUND

3 Prior to 1908, Coaker had been an employee of fish merchants, a telegraph operator, a postmaster, a farmer, a political operative, and an aspiring journalist and politician, long dependent on others for political patronage and working within the boundaries of the existing political structure. In 1908 he was a man imbued with a strong sense of moral outrage, his views informed by nearly 20 years of anger against the treatment outport fishermen had experienced from successive governments and the commercial elite. Living at Herring Neck, Notre Dame Bay, for much of this period, Coaker saw first-hand how fishermen worked hard all their lives and yet had little to show for all their effort. Writing in 1916, he reflected on the fate of two fishermen, brothers John and Elias Warren, who were once leading fishermen, owned their vessels, and yet “died in poverty.” 5 The animosity he had with a Herring Neck fish exporter’s agent greatly shaped and formed his outlook on life as well. Coaker “studied the fishermen’s grievances,” always “took sides with them,” and was “continually in hot water with merchants, politicians and parsons.” He grew passionately devoted to the fishermen’s cause and this “passion was intensified and nurtured by treatment accorded me by those whom circumstances made my opponents.” 6 As Smallwood observed in 1923, Coaker was “not a Socialist — indeed he would hardly know what one was. . . . He is solely a product of Newfoundland and Newfoundland conditions. . . . With all his responsibilities and in spite of his practical nature Coaker is a sincere idealist.” Each of Coaker’s ideas, Noel wrote in 1971 of the FPU, “can be seen as an attempt to remedy a particular ailment of outport society.” 7

4 Coaker’s parents were William and Elizabeth Ford Coaker. His roots ran deep in Newfoundland’s seafaring culture. His mother came from the community of fishermen and longshoremen who lived on the south side (the South Side) of St. John’s harbour. 8 This area was home to the city’s many fish storage premises and seal-oil factories and its residents included mariners and trades-men such as seal skinners, coopers, and other maritime-related tradespeople. 9 His Twillingate-born father was a carpenter, sailor, and sealing master-watch well known among northeast coast fishermen, having spent about 40 years sealing at the ice fields off Newfoundland’s northeast coast. 10

5 His parents married on 16 May 1861 at St. John’s and were members of St. Mary’s Church of England congregation located on the South Side. From age nine years to 14 years, their son sang in the church youth choir, developing a love of music he retained for the rest of his life. The minister at this time was that “venerable, devoted and sincere servant of God, Edward Botwood,” whose preaching he listened to “twice every Sunday” 11 developing a “high reverence for religion.” 12 As a nine-year-old he worked selling newspapers on city streets. 13 He attended St. Mary’s School 14 until his parents took him to work in 1883 on the St. John’s waterfront. He quickly showed his nascent leadership skills in early September 1883 when the 11-year-old fish handler led a successful twoday strike 15 of other young boys who struck for 40 cents a day, the same amount that Bowring Brothers was paying its young labourers. They were being offered 30 cents a day instead. 16

6 He loved political debate and frequented the gallery of the House of Assembly in the early 1880s, where “his father had many times to seek him out listening spell-bound to [Prime Minister William] Whiteway, the master orator.” 17 Whiteway was a populist politician and lawyer who championed railway construction as a means of spurring industrial and agricultural development to diversify the economy from its dependency on the fisheries. 18 Coaker’s father would never understand his quest for knowledge and he “refrained from opening my mind,” as Coaker wrote to his father on 9 December 1894, and consequently never confided in him as “every son should have no nearer friend than a father.” 19

7 In 1885, Coaker attended the General Protestant Academy and Presbyterian Commercial School at St. John’s for the term 21 April to 24 July 1885. He did well in history and arithmetic and average in grammar, spelling, reading, recitation, dictation, and geography. His school report noted that his conduct was “exemplary,” with his attendance at school being “slightly interrupted,” his neatness “very good,” and punctuality “exemplary.” 20 That same year he commenced employment as an assistant storekeeper for McDougall & Templeton, city commission merchants whose business since 1870 21 specialized in the importation of manufactured goods. 22

8 His was a reactive and pragmatic personality. He had a trusting disposition, but if slighted, he observed in a 1912 newspaper article (in the first-person plural that was often his style) “we are composed of material that must offend some. Our composition is of a nature that scorns efforts to coast past enmity with sugar. Our memory is a long one. We never yet started a row with anyone, but if started by an antagonist we will never cave in. Treat us right and, right we will treat you, but treat us wrong and take what comes, is the keynote to the enmity of our enemies.” 23 He was, wrote a Canadian journalist in 1920, a “thick-set man, unusually broad in the shoulders, long armed and big fisted” and “his eyes express the man. Their gaze is frank and steady. There is no staring Coaker down. He has no past and no secrets that shun the inquisitor’s scrutiny.” 24

MANAGER AND FIRST TASTE OF POLITICS AND FARMING

9 McDougall & Templeton also operated a brokerage operation selling lobsters, fish, and blueberries for export, 25 and in 1888 the firm sent Coaker to Herring Neck, a small fishing community of nearly 1,000 residents, to manage its lobster canning operation. This involved purchasing lobsters from fishermen and supervising lobster canning for shipment to St. John’s. The factory was at Pike’s Arm on the northeast end of New World Island. Pike’s Arm was part of the area constituting the community of Herring Neck, situated in Notre Dame Bay eight miles by water from the bay’s principal town, Twillingate. 26 Coaker managed the business for four years, 27 returning to St. John’s each winter to work with the St. John’s firm and to further his education through private study. 28 During the winter of 1890-91, he managed McDougall & Templeton’s canning factory in St. John’s 29 and during the winter of 1892-93 he studied at Bishop Feild College, whose headmaster was William Blackall (a future Church of England superintendent of education) and where one of his teachers was William Lloyd (a future journalist, lawyer, and premier thanks to Coaker’s support in 1918 as leader of the FPU’s Unionist members in the House of Assembly). 30 McDougall & Templeton was dissolved in 1892 with Robert Templeton carrying on the firm’s business, and by 1893 the firm had sold to Coaker the lobster factory at Pike’s Arm. 31

10 In 1889 Coaker had thrust himself into local politics, speaking at an election meeting in Herring Neck that year as Whiteway was returned to power as premier. The meeting was at Salt Harbour, Herring Neck, with the Tory candidates being Augustus Goodridge and Michael T. Knight. That meeting “ended in tumult and confusion” following a “simple question” that Coaker asked Goodridge. This had been his “first taste of politics”; he asked a “question which brought about the collapse of the meeting, which baptized me into the ranks of the Liberal Party,” 32 although Coaker at the time had had “no political opinion.” During the meeting, he had a physical encounter with the brother of James Lockyer (1856-1924). 33 Later derisively described by Coaker as the “lord and master at Herring Neck,” 34 Lockyer was the local agent for a St. John’s fish export firm that operated in the area. Many of the Liberals Coaker befriended in 1889 in Herring Neck became friends for life, fishermen such as Samuel Miles and Joseph Kearley. 35

11 Coaker was active in educational and church matters. Nearby Green’s Cove had a small school chapel where he taught Sunday school. 36 He helped organize a night school for the young men of the community, 37 and in 1892 he led Sunday school for local children and also that year helped form a Church of England Institute at Herring Neck; he was its vice-president, the Rev. George Chamberlain the president. The Institute’s goal was to provide a forum with regular meeting nights for “debate” on contemporary issues for fishermen, and “arranged for several Newfoundland newspapers, and will keep such books and papers in our rooms as will tend to instruct our young men.” His reading at this time was a mixture of contemporary English novelists, such as Charles Dickens, and religious writings. 38 Rev. Chamberlain initially adopted a mentoring role with the young Coaker and wanted him to join the ministry and also marry his daughter. Neither was to his liking. Coaker considered Newfoundland’s denominational educational system to be financially wasteful, producing too many schools and resulting in poor school structures, insufficient school and text supplies, and unqualified teachers. As a member of the Church of England school board for Herring Neck, he attempted to change the local denominational educational system in an 1892 initiative to improve educational facilities but Lockyer, also a member of that school board, opposed Coaker’s suggestions. 39

12 Coaker expected an appointment to the Herring Neck Road Board and to be its chairman after the re-election in 1893 of the Whiteway government. However, the Tory opposition, led by lawyer and Bonavista District MHA Alfred Morine, used the courts to have the government unseated and the establishment of a Tory ministry led by Augustus Goodridge. Goodridge remained in power until the Liberals again assumed power under the temporary leadership of D.J. Greene on 13 December 1894. In early 1895 the legal disabilities barring Whiteway and other Liberals from the legislature were removed and they were returned to the Assembly. 40 On 9 April 1895 the Whiteway government (Whiteway had become prime minister on 8 February 1895) appointed Coaker to the Herring Neck Road Board. 41

13 In 1895 Coaker commenced farming full-time on an uninhabited, low-level island about three miles in circumference and about five miles across from Boyd’s Cove, 42 Notre Dame Bay. Farming offered Coaker the possibility of an independent livelihood. He named his farm Coakerville (which he appears to have first started developing in 1893) 43 and over the next decade he cleared the land for dairy and sheep farming. 44 His turn to farming for a livelihood was in keeping with the farming background of some of his St. John’s ancestors and his grandfather Jonas Coaker’s family; 45 his motivation might also have been the successful farm that Robert Bond, a Liberal politician and son of a prominent St. John’s merchant, had established at Whitbourne on the Avalon Peninsula. Or he might have been prompted by the relative success of his friend John Clair, a fisherman-farmer with a dairy farm at nearby Boyd’s Cove. He first visited the mainly level, heavily wooded island in 1889 and determined that this was where he wished “to make a living from my own manual exertions,” and he “grew to love work and construction” living alone with his dog Tip. He envisioned establishing a sheep farm and turning it into a valuable asset. Writing to his parents on 20 January 1894, he observed that “I like the woods, I think it was made for me and I for it.” He told them that the farm — he had 25 acres “so level, just as flat as the harbor” — could sustain a flock of 500 sheep and be operational within three years. “Then I will contently die, my wish being completed, whether it be accounted great or small,” he continued, for “something will be done that was not done before, but which may in future be a great benefit to this country.” 46

14 The death of his mother in January 1894 temporarily dampened his optimism. From Herring Neck, he “felt her presence on the night she died” in St. John’s, a loss that may help explain his later strong interest in spiritualism. Her death was a great “shock” as he had “no idea she was so ill, but somehow knew that she was dead, before I got the news,” he wrote his father. The country’s bank crash in December 1894 had been a further blow to him, wiping out his savings and forcing him in 1895 to give up the lobster factory at Pike’s Arm and to rent the premises. 47 His financial setback tempered his enthusiasm for rural life. Writing to his father in December 1894 he said that he “will never settle down at Coakerville or Hy [sic] Neck either, I don’t like outport life, but it is a fine school for me and will be a stepping stone, for the experience I will gain will be very valuable to me and besides I will be more widely known and get acquainted with people I would never see if I was at St. John’s.” The reason he had stayed at Herring Neck so long, he explained, was because he had hoped to use public influence in the area to help make a name for himself, something he would not be able to do as easily if he stayed in St. John’s. 48 His failure to remain in the lobster business he later attributed to the opposition of James Lockyer, claiming to Colonial Secretary Robert Bond that Lockyer, also involved in the lobster business, tried to put him out of business because of the strong political animosity that had developed between the two men who were the acknowledged leaders of the area’s two political parties. 49 He continued to maintain a public profile by writing letters to the Twillingate Sun. Concerned about the plight of fishermen, for example, he denounced the low price fishermen received for their fish, and in late 1895 he called on fishermen not to be “duped” any more when fish was being bought by merchants in the Green Bay area for $3.00 per quintal and sold by St. John’s exporters in Europe for $5.60 per quintal.50

TELEGRAPH OPERATOR AND POSTMASTER

15 In 1895 Coaker helped organize a requisition from the Herring Neck area supporting Bond’s candidacy in a by-election scheduled for 26 September 1895 in Twillingate District, which Bond won by acclamation. 51 Faced with financial difficulties, he appealed to Bond for employment help. “I have been in communication with reliable persons in Wisconsin, 52 U.S.A., with the object of leaving Nfld. and trusting my future to develop itself in the United States,” Coaker informed Bond. 53 “But the love of my native soil burns strongly,” Coaker wrote him in September 1896. 54 By then, Coaker had already spent about $2,000 on his farm with the “object of making it self-supportable in time.” He intended to go into sheep farming but failed to get a government agricultural grant to aid him. 55 As his “financial affairs” now were not in a “very healthy condition,” Coaker, who regarded himself as the only person who could loyally inform Bond of political events in the area, 56 offered Bond a proposal that he felt would enable him to stay in Newfoundland and continue developing his farm, while providing unswerving loyalty to Bond’s political cause in the area. Because of his political support for Bond, he had made some enemies in the area and they have “worked with the object of doing all the harm possible to me, which have resulted in me having to withdraw from trade.” To remain at Coakerville, he asked for government employment on a short-term basis. 57 Coaker blamed Lockyer for his situation, the latter having become his “enemy since, because I dare have an opinion of my own.” 58 Coaker had further showed his loyalty to Bond by having formed a Herring Neck branch of the Northern Liberal Association (NLA), the District party organization Bond had organized in 1896. 59 Coaker shared Bond’s view that each NLA branch have an educational role by making books and newspapers available to members. For the Herring Neck branch, he asked Bond to send immediately a flag, “red with white letters N.L.A.” 60

16 Coaker requested the post of telegraph operator (at the monthly salary of $20) and postmaster (at the yearly salary of $50) at Herring Neck in addition to teaching school in the community. The latter position was held by the local female teacher, but Coaker informed Bond that her operating practices allowed Bond’s opponents to know government and Liberal business; besides, her father was a “very bitter opponent of yours” and should not be allowed to have the post office on his property. Coaker proposed that the teacher be transferred to another community. 61 In four or five years he would have saved enough money to make his farm self-supporting, thereby enabling him then to give up his government positions. Coaker claimed that the proposal would be advantageous to Bond, for it “would benefit you and the party by having a figure-head for your supporters at Herring Neck. For they are now as sheep without a shepherd, and would keep me in my own country.” Coaker’s appointment would “please your supporters at Herring Neck and around” and “I know the Government will be only too pleased to reward in any way the services of a supporter.” 62 Coaker considered himself Bond’s ears and eyes in the area and had kept Bond informed of the activities of his political opponents, who were prominent community leaders while Bond’s supporters in Herring Neck consisted of “some planters, with most all of the common poor fishermen, but all uneducated.” 63

17 Coaker once more appealed to Bond in November 1896 for a response to his “proposal at an early date (if possible), as I want to make some definite arrangement as to my future movements.” He also asked Bond to speak to a local director of the Montreal Loan and Investment Company about a $500 loan application he had made to that company. 64 There is no evidence Coaker secured the loan, but he received his appointment as telegraph operator. Appointed on 14 January 1897, Bond advised him the following month that he was “now a public official, and don’t do or say anything that will interfere with your usefulness as such” and warned him to avoid any confrontation with Lockyer or any “other business man over politics.” Bond acknowledged that Coaker had a “perfect right” to his political opinions and to “exercise them, provided you do not do so offensively.” However, Bond would not stand in the way of Coaker’s “personal interest,” although Bond informed him that he would “suffer loss” politically if he became offensively outspoken because Coaker had always been a “most active worker for the Party.” 65 Bond agreed to Coaker’s suggestion that the NLA adopt a “literary” side by “having certain nights set aside for debate, and others for reading and writing [as this] is just what I had in view when I threw out the proposal of forming the ‘Liberal Association’ two years ago in Twillingate. I am quite certain that there is no better way to win the confidence of the rising generation than by discussing with them all matters of public interest, by providing them with reading matter and encouraging a taste for reading. You are just the man to help such a movement forward, and your business hours will now be such as to afford you ample leisure to do so, and this will in no way conflict with your public duties.” 66

18 Bond had told Coaker on 13 February that his appointment as telegraph operator would be conditional on the people of Herring Neck petitioning the government for the removal of the existing incumbent. On 18 February he also received the additional appointment of postmaster with the post office being transferred to the telegraph office. While it is not known if a petition soon followed, when Bond informed Coaker on 6 March of his appointment as postmaster, Miss Miles had “left the District.” 67 The post office was removed to the telegraph office and Coaker’s joint salary was set at “$400 per annum to date from the first of April” with the Postal Department and the Government Engineer’s Office (the department then responsible for the government telegraph system) sharing the cost. In justifying the merger of both offices, Bond noted that in 1895 the Inspector of Post Offices had visited Herring Neck and reported in favour of the post office being removed to the telegraph office location, the most suitable site in the community. 68

19 Despite these appointments, Coaker’s financial problems remained pressing. His farm was secured against any attachment and in June 1897 he offered one creditor, St. John’s hardware merchant Sidney Woods, a compromise whereby, by December 1898, he would repay his debt of $650 at 40 cents on the dollar with part of his wages as a public official being put aside for this purpose. He asked Bond to guarantee his repayment method and to ask his creditor to accept this compromise proposal. 69 The matter of the “alleged insolvency of W.F. Coaker of Herring Neck” was scheduled to be heard in the Supreme Court on 2 June 1897, but was postponed to 16 June as “negotiations are being held with a view to a compromise.” On 16 June the Court agreed to a further postponement pending the completion of negotiations. Arthur Knight, Coaker’s lawyer, informed the court that Coaker’s creditors had agreed to the terms offered. It is not known when or how Coaker compromised on his debts with all his creditors and who they were. 70

20 In 1897 Coaker was still the chairman of the government-appointed Herring Neck Road Board and his determination to provide much-needed employment soon landed him in legal difficulties. A road board was responsible for the expenditure of annual grants from the legislature to maintain roads and bridges in consultation with the government, or with the district representative if a member of the governing party. On 27 April 1897 Elijah Powell of Merritt’s Harbour in the District of Twillingate took out an affidavit before James Lockyer, J.P., alleging that Coaker used funds of the Road Board for which no work nor service had been rendered and that the individuals who were paid did work for Coaker for his personal benefit. 71 In his own defence, Coaker wrote Bond that during the past winter he had relieved “destitution at Boyd’s Cove, Cobb’s Arm, Pike’s Arm, Too Good Arm, Gut Arm, [and] Starve Harbour” and had helped “every man making application to me for food, this winter & spring, I have also given potatoes to every person applying to me for work to obtain them. No matter who or what he was.” He contrasted this with the mercantile practices of Lockyer, who refused supplies to any fisherman who was a member of the NLA. 72 For being a “loyal Liberal,” he was “grieved to death with a threat of being convicted a criminal.” 73 “Had it not been for your letters and words advising me to be cool,” Coaker told Bond, “Lockyer would have a sore head this very minute, although I would be punished for it. He has done all that a mortal enemy can do to hurt me. He has sent men, sent spies, got men to scatter lies to hurt me . . . And all because I am working for you.” 74

21 The facts of the situation as found by a judicial inquiry into the charge held by St. John’s Magistrate D.W. Prowse at Herring Neck on 14 July 1897 were the following. In the autumn of 1896, Powell informed the government that there would be considerable poverty during the winter of 1896-97 at Merritt’s Harbour and it would be necessary for the government to provide relief. On 9 March 1897 the Herring Neck Road Board itself informed the government of the situation at Merritt’s Harbour and on 19 March received authorization to spend $120 on a public wharf there. Only the most destitute people were to be employed. On 2 April the government authorized the board to spend $100 on public works to help alleviate the destitution at Herring Neck. Board chairman Coaker was responsible for both expenditures. Before giving out the Herring Neck relief, the board members decided to keep this grant secret or otherwise there would be a great demand on the board to provide more relief than it had funds for. With the support of board members Samuel Miles and Joseph Kearley, Coaker gave relief to Herring Neck people “in the name of Elijah Powell to whom the Road Board had given a contract to build the wharf at Merritt’s Harbour for one hundred and twenty dollars.” Prowse found that the Board’s activity concerning the wharf was straightforward. Coaker also provided Prowse with an account of the expenditure in Herring Neck, where the people were employed in cutting wood for the construction of a canal at Pike’s Arm, as well as the names of all the parties who worked with the amount paid to each. As far as Prowse could determine, it was “all bona-fide” and the procedure of employment and payment was in accordance with the rules laid down by the government for the governance of road boards. Prowse acquitted “William Ford Coaker, and the other members of the Road Board of Herring Neck, of fraud and malversation of the public funds entrusted to them.” He was convinced that the complaint against “Coaker arose from personal and political ill feeling towards him and not from any regard for the public service, the object of Lockyer and his allies was simply to ruin Coaker as a political opponent and this object is plainly shown by the complaint having been forwarded to Mr. [Alfred] Morine.” Prowse also informed Bond that Lockyer admitted to him that he “looked on Coaker as an interloper in Herring Neck and that he had wished that someone else to be placed in the telegraph and Post Office.” 75

22 A change of government in the 1897 general election won by James Winter resulted in Coaker and other Liberal officeholders being quickly replaced by Tory supporters. As he later recalled, he “deserved being fired, as we did work for Bond against Morine, and consider that any public official who takes a hand in politics must be prepared to take what comes. We did not value the position and did not care whether we went or stayed.” 76 In the Herring Neck area, this meant that Lockyer and his supporters were in the political ascendency. On 22 November 1897 the St. John’s Tory newspaper Evening Herald reported that Coaker had been “fired, he having made himself a violent partisan,” and his replacement, Elizabeth Cassels, was being paid half the salary Coaker had received. 77 The newspaper’s claim did not go unchallenged. John Kearley and Samuel Miles, chair and secretary of the Herring Neck branch of the NLA, responded that Coaker was “fired” to “give place to a Tory who is as qualified to fill Mr. Coaker’s place as we are to rule England. . . . Mr. Coaker is so popular, and has worked so hard for our Common Good, that, if he required it, three-fourths of the people of Herring Neck would memorialize His Excellency to reinstate him. We learn that Mr. Coaker intends spending the winter in Canada on ‘The Isaleigh Grange Stock Farm,’ owned by J.N. Greenshields, Esq., so as to better prepare himself for the sheep-raising industry to which he intends to devote part of his time. We are glad to learn this, as young men of Mr. Coaker’s stamp and pluck are what this country stands most in need of to-day, and we will be glad to welcome home amongst us, hearty and well, when his course at the Stock farm is finished.” 78

FARMER

23 Coaker declared his plans in a letter to Bond. The letter equated his own frustrations of being summarily dismissed for patronage reasons with the fate of Newfoundland generally, which had fallen into the hands of non- Newfoundlanders such as the Nova Scotia-born politician Alfred Morine, Winter’s Finance Minister, for it “will be as well to live in Africa as in Nfld., for next four years if the present Blue-nose government hold out. If the Tory government were composed of natives, we would swallow it.” He told Bond that he would remain at his farm for a few days to “get work fixed up,” then go to St. John’s for Christmas and petition for insolvency, his financial problems apparently still unresolved. With additional funding, he would return to his farm in June 1898 after “spending the winter on a stock farm in Canada, returning in May (if I am backed for business). If he could not get any financial assistance, he would make “an effort to get to South Africa (when leaving stock farm) and wish Newfoundland good bye.” In case he went to South Africa, he asked Bond for a letter of introduction to businessman Cecil Rhodes “or anything in writing that may be a help to me.” 79 Coaker instead spent the winter of 1897-98 in St. John’s, 80 returning to Herring Neck in March 1898, and then helped organize public protest there against the 1898 Railway Contract. Country-wide, Bond, now the leader of the Opposition, at this time was mobilizing public opposition to the agreement that gave Canadian railway builder Robert Reid control of the recently completed trans-island railway. 81 Coaker had been present in the House of Assembly in February 1898 when Bond impassionately rallied public support against the contract, the fight for his native land now being uppermost in his mind. 82

24 However, Coaker’s legal difficulties remained. In early 1898 charges of fraud were laid against him. He claimed later the charges were an attempt by the government to drive him from Newfoundland itself by offering to drop the charge if he immigrated to the Crow’s Nest Pass in western Canada, a place of railway employment where many other Newfoundlanders at that time were going in search of work. In short, the government’s claim was that Coaker had attempted to obtain $8.80 by overcharging accounts while he was an operator at Herring Neck. Superintendent John Sullivan 83 of the Newfoundland Constabulary went to Herring Neck to arrest him and conduct an investigation under the direction of local Justice of the Peace James Lockyer. Sullivan summoned several witnesses before Lockyer, who held court for a day on the matter with Coaker being refused bail. After that one day, Lockyer no longer held open court and allowed Sullivan to continue the investigation for another three days before releasing Coaker on security bonds of $2,000 and requiring him to appear at St. John’s within a week. Coaker renewed his bail weekly for three months as the government did not move to bring this case forward. Finally, that charge was dropped (Sullivan evidently was unable to find any evidence to support the charge against Coaker) and another one was laid based on the evidence of the Prowse Inquiry of the previous year for a trial before the Supreme Court at St. John’s. Ice conditions along the coast prevented Coaker from being able to appear for 20 May when the Supreme Court opened for its spring sitting. He arrived in St. John’s soon afterwards and the Crown declined to proceed with the case right away, but Chief Justice Joseph Little on 6 June required Coaker to post bail of $400 and to surrender himself to the Court again on 20 November. Coaker’s brother John posted $200 for the bond and a friend, Joseph Hobbs, put up the remaining $200. When he reappeared before the Court on 21 November before Justices Little and George Emerson, his lawyer, Herbert Knight, successfully got a discharge as the Chief Justice believed little evidence existed for a prosecution and the government was unwilling to pursue the matter further. 84

25 Having decided not to leave Newfoundland, Coaker had returned to farming full-time. For the winter of 1899-1900, he travelled to Canada to study agricultural techniques. He visited the Agricultural College in Guelph and spent four months employed first at the Halifax Grange farm 85 and then at the Isaleigh Grange Farm at Danville, Quebec. He wanted to improve his knowledge of animal husbandry and stock-breeding. Interviewed in the Evening Telegram in early April 1900 upon his return to St. John’s, Coaker stated that stock-raising could be carried on in Newfoundland on a scale sufficient to meet the country’s needs. Also, his study of the dairy industry in Quebec, he said later in 1914, had convinced him of the need for proper government inspection and regulation of the industry so that “every gallon of milk there is inspected and has to go through a process,” while the farmers’ butter was also inspected and “unless it is up to a certain grade of fat, the factory will not take it.” 86 Armed with his new-found knowledge and experience, Coaker visited the stables of the Board of Agriculture outside St. John’s later in April 1900 and then challenged the government in a letter to the press by declaring the stables a “useless waste of public moneys” because of the poor sanitary conditions in which the sheep were being maintained. Coaker was now well prepared for agricultural work in his “native soil” where he believed sheep-raising could be made a “success.” 87 However, he did not limit his activities to farming. He remained active in supporting the Liberals and served as secretary of the Herring Neck NLA branch.

AGITATING BOND

26 In 1900 Robert Bond, who had replaced Whiteway as Liberal leader, became prime minister. However, the patronage that Coaker and his supporters felt he deserved for their political devotion was not immediately forthcoming. Bond had promised him in October 1901 that he would try to find employment for him. Coaker wanted the position of preventive officer (customs officer) at Herring Neck in addition to the positions of telegraph officer and postal officer he had held in 1897. Bond instead gave those positions to the local schoolmaster. Writing to Bond in February 1902, a frustrated Coaker claimed that the new appointee was no supporter of Bond and asked him how he expected “to retain the support of your friends by such means as this. You know my position and how loyal I have supported you and certainly if anyone had a claim upon a party I have. . . . Try to discern your true friends for those who will kiss your face and cut your throat after.” Coaker declared that he had waited “patiently long enough. You have been in power nearly two years. . . . I mean business in future, and I will indeed feel obliged for an early reply. I shall be sorry to take any part against you, but my future actions must depend on the treatment I receive from you. . . . I have no doubt but Sir Wm. Whiteway will be glad to have my support, and if given, will be active as possible.” Coaker wanted a definite reply from Bond by 1 March 1902. 88 The enthusiasm of the Herring Neck NLA branch for Bond and their desire to flatter him apparently knew no bounds; indeed, they had wanted to rename their community “Port Bond,” a choice the prime minister refused to endorse. Similarly, Joseph Kearley also intended to name his new schooner he planned to launch in April 1902 the “Hon. R. Bond” but Bond ignored this request and the vessel was named the “Marilla.” 89 Flattery did not work on Bond, at least not from his constituency supporters at Herring Neck who still supported Whiteway, who had been politically alienated from Bond since the latter had taken control of the leadership of the Liberal Party in 1899. 90

27 The Herring Neck Road Board also supported Coaker’s claim for a job from the government. Samuel Miles (chair), Joseph Kearley (the father of Josiah and Edwin Kearley), John Edney, and Benjamin Torraville wrote Bond in February 1902 to rescind the recent public appointment at Herring Neck, asserting that “we are your supporters here and claim to have common sense enough to manage our own local affairs. We respectfully recommend you to appoint W. Coaker to his old position and that of preventive officer. If you carry out our requests we are your firm and faithful friend, but to decide, you will find that Lockyer and other opponents are your enemies and will ever remain so.” If Coaker was not appointed by 1 March 1902, the board members would resign and petition for Coaker’s appointment. 91 Joseph Kearley also wrote separately to Bond two days later objecting to the insult and snub Bond had delivered to Coaker, as the appointees made were “opponents of yours,” whereas “Mr. Coaker has been a faithful supporter of yours.” Kearley threatened to withdraw his support for Bond after 1 March: you may “look upon me in the future for the same actual opposition to you as I have hitherto supported you and I speak for many and can assure you that if you lose Mr. Coaker’s support you may consider yourself doomed here. . . . I am so deeply pained by the way you have treated us that I cannot find words strong enough to condemn your treatment.” Kearley wrote that he would not be surprised to see Coaker running against the Bond candidates in the next election in Twillingate District. If Bond did not do justice by Coaker, then Kearley threatened to publish a copy of his letter to Bond and if you take Coaker for a “fool you are mistaken.” 92

28 On 28 May 1902 Coaker was appointed the telegraph operator at Lewisporte, where the Bond government had decided to erect a telegraph building, one of several it had determined would be constructed as near to the railway station in each community as possible. 93 He resided at the hotel owned by Alfred G. Young, who was active in area Liberal politics. 94 Coaker later recalled in 1921 that “many a winter night I sat with Mr. Young around the fireside discussing matters of public importance years before I started the Fishermen’s Union. He was a splendid debater and possessed an abundance of general knowledge and common sense.” Coaker admired Young because he “always maintained his independence and possessed moral courage to express an honest opinion in every matter,” traits that Coaker greatly admired in public officials and that he prided himself on possessing. 95

29 His stay at Lewisporte was not without controversy. He refused instructions from Postmaster General H.J.B. Woods and Telegraph Superintendent David Stott to teach pupils telegraphy without charging a fee for his efforts. 96 More seriously, Coaker protested the letting of a contract for the construction of the telegraph building and let his displeasure be known to the Postmaster General. Annoyed by Coaker’s “agitation,” Bond sternly informed him on 5 November 1902 that it was “entirely unusual and entirely improper on the part of any public official to agitate in the matter that your letters indicate and I have to request that, so long as you are connected with the Public Service, you will confine your attention to the duties that are assigned you.” Coaker had also complained about the telegraph operator at Beaverton, a small fishing settlement located near Boyd’s Cove. Specifically, Coaker had become angered with Ewen Hennebury, who had taught telegraphy to Coaker in 1897, and who refused to put through a personal message to Coaker “dead head,” meaning without charging it. This message had been sent from H. Elliott to Coaker at Coakerville. Coaker also claimed in his letter that Hennebury had refused to pay the expressage of 40 cents for a message delivered to Hennebury by his repairer, Alfred Kearley, and Hennebury did not give any account of it in his returns. 97 Postmaster General Woods assigned Telegraph Superintendent Stott to determine Hennebury’s views on the matter. Hennebury wired Stott a sample of another one of Coaker’s service messages: “To David Barrett, Beaverton. Please take freight and mail from Clyde for Edwin Kearley. Put apples in your cellar.” Hennebury observed that “this fellow Coaker would flood the line with such messages if allowed.” Stott then informed Coaker that “such messages as you have been sending to Herring Neck and Beaverton cannot go free. I have instructed Norris Arm to pass nothing from you except regular business and service messages necessary thereto.” 98 Lewisporte resident Uriah Freake also complained to the government about Coaker, noting that the latter had sent a telegram from the government telegraph office in Lewisporte to St. John’s solicitor James Clift (and Twillingate Liberal MHA) but apparently under the name of Uriah Freake, complaining against the erection of a new building in the town for the telegraph office. Bond ordered an inquiry into the matter on 31 December 1902 and appointed Liberal Burgeo and Lapoile MHA and lawyer Charles Emerson as a commissioner. 99

30 Arriving in Lewisporte on 19 January 1903, Emerson visited Coaker at the telegraph office, where he read his commission and asked Coaker to repeat his charges against Hennebury in order that Emerson could write them down. As Emerson wrote in his 24 January report to the government, “Mr. Coaker being apparently taken by surprise,” he showed him a copy of Coaker’s letter to the Postmaster General with Coaker refusing to specify any of his charges against Hennebury. Emerson then placed him under oath and Coaker then made his charges against Hennebury. In his evidence, Coaker stated that he could not say of his own knowledge whether Hennebury “appropriated the money to his own use.” Emerson also interviewed Hennebury, who “emphatically denied the charge.” 100 Emerson’s report exonerated Hennebury, who “has always been regarded as an honest and faithful servant.” He noted that because “charges [are] so wild and absurd,” he looked “for a motive on the part of Mr. Coaker in preferring them in his letter to the Postmaster-General.” Emerson could “discover nothing beyond the fact that Mr. Coaker seems to be dissatisfied with his present surroundings and evidently forgetful of the fact that he is merely a telegraph clerk, has taken upon himself the responsibility of voicing what he considers to be the opinion of the public in connection with the building of the new telegraph office.” In other letters and correspondence with the Postmaster General, Coaker had expressed his displeasure with the new building while lobbying for the actual positions of sub-collector and postmaster. “Being in this dissatisfied state of mind it may possibly be,” Emerson wrote, “that in making those charges, Mr. Coaker may have not realized the seriousness of the position should he fail to substantiate them, otherwise I cannot discover why he should have acted as he did.” 101 Coaker later, in 1912, publicly refuted this charge, claiming that Emerson was politically motivated and refused to take the oath of the repairer Alfred Kearley “showing he did receive the money which Elliott paid Hennebury for expressing the message.” Coaker also claimed personal vindication from Emerson’s inquiry: “the result of the trouble was Bond offered us immediately after the position at Port Blandford [with] an increase of $200 on our salary. That did not look as though he paid much heed to Emerson’s very partial suggestions.” 102

TELEGRAPH UNION “PROMOTER” AND BREAKING WITH BOND

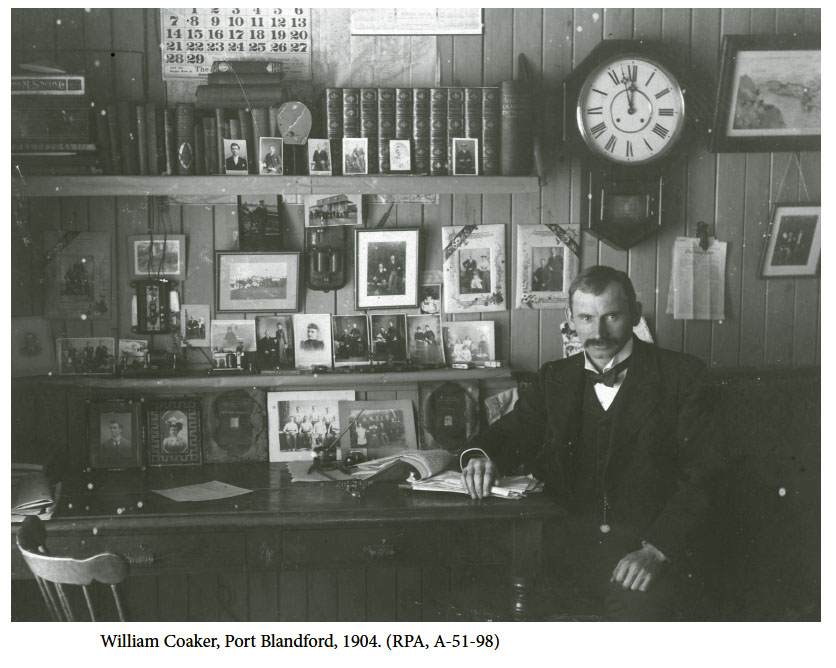

31 Coaker accepted a transfer in April 1903 103 to Port Blandford, Bonavista Bay, where he ran the post office and the telegraph office and was sub-collector of customs. Journalist and folklorist Patrick K. Devine, a boyhood friend who was undertaking a two-week holiday tour of Bonavista Bay and Green Bay, visited him there in late July. Devine has left us a vivid description of the young Coaker in 1903:

A reporter for the Evening Telegram, Devine was on holidays on his way to his hometown of King’s Cove, and had only 10 days with an assignment to write a series of articles about the Notre Dame Bay area. Coaker offered to write the articles for Devine of a trip around Green Bay “as if written by him on the boat, he knew every arm and inlet, the industries, the business places, etc., and when I continued from King’s Cove the next week in the S.S. Dundee he had the big role of manuscript all ready.” The articles were anonymously published in the Evening Telegram under no byline, although it was generally believed that Devine was the author. 104

32 Coaker confided to Devine that he was in the process of organizing the telegraphers into a union. The development of marine-related secondary manufacturing in St. John’s after 1870 and the construction of a railway across the Island had given impetus by the late 1890s to the establishment of labour unions, especially in St. John’s, and the rise of strikes as unions fought their employers for better working and wage conditions. Among the most notable industrial actions at the turn of the century, there was a strike on Bell Island in 1900, a sealers’ strike in St. John’s in March 1902, and in 1904 a railway strike at Placentia against Reid Newfoundland. After a strike of dockworkers in 1903, the Longshoremen’s Protective Union was formed. 105 Unhappy with the working and living conditions of his fellow telegraphers, in 1903 Coaker began secretly to organize the railway telegraphers employed with both the Reid Newfoundland Company and the government telegraph service; the latter service the government in 1901 had acquired from Reid Newfoundland and placed under the jurisdiction of the Postal Office. 106 Signing himself “Promoter,” he sent a circular — “Circular No. 1 To be treated as confidential on both sides” and signed “Yours for Fraternity” — in late July to the telegraphers, using as a mailing address post office box 232 in St. John’s. The circular asked the telegraphers to declare their membership, “which is equivalent to signing the roll,” in the proposed union. Having received sufficient affirmative responses, “Promoter” informed the press in early August that the union “is now formed” but “for the present the officers’ names are withheld” out of fear that Reid Newfoundland would dismiss those who had joined the union. 107

33 The Evening Telegram, a supporter of the Bond government, reported on 14 August 1903 that Donald Morison, a St. John’s lawyer, had rented the postal box. A former Conservative MHA representing the District of Bonavista from 1888 to 1897, former St. John’s municipal councillor (1892-96), and Supreme Court judge from 1898 to 1902, Morison had resigned from the Supreme Court in 1902 to resume his law practice. He announced his return to active politics in April 1903 with an appeal to “the great body of the fishermen and workingmen that I look for the membership of my party.” 108 While Morison in 1902 had asserted his political independence upon leaving the bench, by November 1903 he was in negotiations with Whiteway to co-lead a new opposition party opposed to the then Morine-led Opposition party and against Bond for the forthcoming general election scheduled for the following year. 109 The newspaper also identified Morison as “Promoter.” 110 Morison quickly filed a libel suit in the Supreme Court, claiming the newspaper “maliciously de-famed” him by claiming that he was the author of the circular letter signed “Promoter” and by stating that “the ex-judge is not a discreet man by any means” and “if he were not a very indiscreet man he would still be a judge of the Supreme Court.” 111 The case before a jury was first heard on 10 October before Justice George Emerson, with Arthur Knight (he had represented Coaker in 1897 in his Supreme Court case) representing Morison and Martin Furlong representing the newspaper publisher, William Herder, and its editor, Alexander Parsons.

34 Although he knew who “Promoter” was, Morison told the court he could not disclose such information for professional reasons. The circular came to him “professionally” in “professional confidence” in his business as a solicitor. He had “no authority from my client to disclose his identity. Beyond this professional confidence I have no connection with the authorship of the circular.” He explained his role in the matter to the court.

35 Following Morison’s testimony, Furlong moved that the judge dismiss the case because the “words are not actionable in themselves” and no “evidence was given of the innuendo, and the words cannot be understood as applying to him in his professional capacity. The whole tenor of the article is political.” Judge Emerson dismissed the case because the newspaper article demonstrated no intent to show any charge of professional misconduct against Morison. He also stated that Morison acknowledged his role as an agent for “Promoter,” “doing work for which he must accept the consequences.” The judge withdrew the case from the jury and found court costs against Morison. 113 Morison’s account of his activities were confirmed by “Promoter” in a 14 November letter to the Free Press: “Why Mr. Morison was chosen is, we wanted a solicitor who had no connection with Reid [Newfoundland Company] or the Government. We wanted a solicitor who we could fully trust, and that man was Mr. Morison. We had no connection or correspondence with him concerning the movement before he was retained, and every action performed and every word uttered by me have originated with us.” 114 It is not known otherwise how well Coaker knew Morison at this time.

36 The Reid-owned and Opposition newspaper, the St. John’s Daily News, praised the court’s decision, noting that the proposed strike “might easily have been a very serious matter. All concerned in it if it had taken place might possibly have been indicted for conspiracy.” The newspaper emphasized how critical the telegraph was as an integral part of communications: “Life and death, misery and happiness, liberty, shipwreck, disaster by sea and land — each and all might depend upon the transmission or non-transmission of a telegram, and therefore to promote a strike of operators would be a crime against the public too heinous to be highly excused or easily atoned for.” 115 Upset over the response of the Daily News to the Morison libel case, on 13 November Coaker wrote the Evening Herald, a newspaper edited by Patrick McGrath 116 that supported the Bond government, thanking Morison for his efforts with the circular and defending the right of telegraphers to form an association to fight for better working conditions and higher wages. Coaker denied that the circular called for a strike among the telegraphers and stated that Morison had been retained because he had no association with either Reid Newfoundland or the government, two employers of local telegraphers. Telegraphers from a third employer, the Anglo-American Telegraph Company, 117 were not involved with forming the association because their work conditions were much better. Coaker’s letter also thanked “Promoter” for “initiating with such ability and secrecy the movement from which this Association has been elaborated.” 118

37 The Daily News responded with a strong attack against him, asserting that Coaker was “Promoter” and was “in his own person the entire Association.” The newspaper reminded its readers that Coaker was a Bond heeler who once had been charged with “embezzling road money.” Coaker was now in the “pay of the government as a telegraph operator, and is earning his money apparently by promoting strikes, and writing grossly offensive and partisan letters. . . . Most men would pay to maintain silence.” The newspaper ridiculed the idea that Coaker, as secretary of the union, had thanked “Promoter” for helping to organize the union, in effect thanking himself. 119 The insult did not go unchallenged, Coaker replying on 18 November in another letter to the Evening Herald. First, he denied saying he was “Promoter” in his previous letter to the Evening Herald. “Regarding the ‘secretary’ of this ‘association,’” he wrote that his duties will “from time to time, cause him to cross swords with the enemies of freedom, but his determination is to sink or swim, live or die, survive or persist, in the ranks, doing his duty and nothing that the Daily News or any other man may utter will deter him.” 120 Another letter, also dated 18 November and published in the Free Press, addressed the embezzlement accusation. Coaker emphasized that a judicial inquiry in 1897 had exonerated him of any wrongdoing and that the charge had arisen from “personal and political ill-feeling towards him, and not from any regard for the public service, the object of his opponents being to ruin Coaker as a political opponent, and this object is plainly shown.” 121

38 The circular had its desired effect despite an unsuccessful effort by Reid Newfoundland, which hired a former member of the Newfoundland Constabulary to investigate the identity of “Promoter.” “Promoter” got the signatures necessary to form a Telegraphers’ Association and by early November a slate of candidates was elected as officers of the union formed on 2 November. 122 Coaker was elected as union secretary. 123 As such, he had responsibility for all publicity matters associated with the union.

39 On 19 December 1903 the Telegraphers’ Association approved the establishment of a newspaper 124 to be issued on the first Saturday of each month. The small four-page paper cost members an annual subscription of one dollar for male operators and 50 cents for lower-paid female operators. The Telegrapher’s editor was Coaker, who claimed it was the first union newspaper published in Newfoundland. 125 The first issue appeared on 14 January 1904 and was printed at the office of the weekly Free Press, owned by John Robinson, a former Conservative politician. 126 In the 5 March issue Coaker declared that the newspaper and the Association had “no politics. We know no political creed.” 127 The newspaper boldly proclaimed the rights of labour:

Both the government and the Reid Newfoundland Company reluctantly accepted the formation of the Association, with the latter officially recognizing it in early 1904.

40 The Telegrapher highlighted the grievances the telegraphers had against their employer, especially Reid Newfoundland. They were required to work long hours (9 a.m. to 8 p.m.) even though the amount of business did not justify their presence on the job after 6:30 p.m. They were required to pay for their substitutes when they were fortunate enough to get a leave of absence and to pay the travelling expenses of their substitutes. Wages for female telegraphers were low —$150 per annum — while male operators received between $400 and $580 per annum, a wage that the union argued was too low for the men. 129 The telegraphers were housed in inadequately heated houses rented from their employers. In the 5 March 1904 issue, Coaker wrote that the Lewisporte telegrapher had recently been forced to leave his post for medical treatment in St. John’s “suffering from a severe attack of pleurisy.” Coaker warned that “something must be done to improve [the housing conditions], or every operator will eventually be a victim to pleurisy or consumption.” 130 The government refused to consider several requests from the Association. These included the daily closing of telegraph offices at 6 p.m. from January to the last of April, the refusal to provide free mailing by post of books in connection with a proposed circulating library to be established by the Association, and the issuing of free passes to government operators who reported the movement of coastal steamers operated by the St. John’s firm Bowring Brothers under contract to the government. 131

41 The Telegrapher supported the efforts of trade unions in Newfoundland in challenging the existing economic and political system, recognizing the principle that “In Union there is strength” and that “labor has an uphill battle locally just now, but the present must struggle if the future is to be beneficial.” 132 He gave particular attention to the plight of fishermen. In the 2 April 1904 issue Coaker championed the fishermen —the “despised, ill-treated, down-trodden fishermen” — as the “mainstay, bone and sinew of our Island home.” He asked whose hard earnings

42 On many occasions, Coaker wrote, his “blood has boiled to see creatures posing as the friends of fishermen, fleecing them like a pack of wolves when returned to power, and appearing as wolves in sheeps’ clothing on the eve of an election, using Heaven and Hell to further their designs and to cover up their boodle.” Coaker laid the blame for the perpetuation of this political system at the door of the “miserable sham of education so dear to the hearts of the politicians of Newfoundland.” He personally saw its devastating effects on children at Herring Neck, where a denominational school system led to duplication and waste without benefit to the children. “If we cannot have undenominational schools,” Coaker believed that at least the Protestants should combine their educational grants from the government to provide the best schooling system in each community. 134

43 Also, by this time his break with the Bond government was complete. The 1 October 1904 issue of The Telegrapher was a strong condemnation of the Bond government and championed the recent return to politics and the liberalism embodied by Sir William Whiteway, who was one of the leaders of the United Opposition Party formed to fight Bond in the general election of 31 October 1904. Editor Coaker wrote that as a

Coaker was also unhappy over Bond’s 1901 compromise with the Reids instead of cancelling the 1898 contract as he had promised to do in the 1900 election. 135 And he actively campaigned for Bond’s opponents in the Green Bay area. 136

44 Coaker resigned his three public positions at Port Blandford on 20 October 137 rather than wait for his dismissal by Bond, whose government won re-election 11 days later. He continued as editor of The Telegrapher until the February 1905 issue, having given the Association sufficient advance time to find a successor as editor. 138 He wrote his brother, John, that Bond was “right cold” for him and “if all knew him as I do he would not be Premier today.” He hoped to “have the chance of showing him up during next few years, and doing it in a way that will bring him defeat.” Bond’s only regret was that “I got ahead of him. He knows long ago what I think of him.” It was impossible to be both a Liberal and a Bondite, and having followed Sir William Whiteway, that “shall always be my warmest pride.” In an unpublished memoir written in the 1930s, Alfred Morine, who had had the opportunity to observe both Bond and Coaker from both sides of the House of Assembly, observed that Bond and Coaker were diametrical opposites in temperament and ideology. He wrote: “Bond was cultured and refined; Coaker was not — Bond was experienced in public life and office; Coaker was not. Bond had studied political economy, and knew parliamentary principles and practices; Coaker knew little about either. Bond was born to be a Tory, for he was the son of a merchant, and was endowed with wealth earned by his father in the supplying business; Coaker was a Liberal by heredity and a Radical by nature, and he was not blessed with a spare dollar when he was elected to the Assembly [in 1913]. But though Bond was so richly qualified, and Coaker so poorly, Coaker was the abler man, more vital, more daring, and more reckless.” 138 In short, Coaker found in Bond an unsympathetic patron with no time for the partisanship Coaker symbolized.

45 Port Blandford residents signed a public address on 23 December 1904 to Coaker expressing regret at his resignation and declaring their “warmest appreciation and thanks for the faithful, efficient, and gentlemanly manner in which you have performed [your duties] . . . since your appointment here. Your duties were closely attended to; we always found you at your post and have always been ready to assist us with advice and council.” They also thanked him for his interest in civic affairs: “as a citizen you have won our deepest respect, and you have taken an active interest in all that concerned the welfare of the settlement. The result of your efforts will ever encourage us to advance, ‘progress’ being your watchword.” 140 Both the Telegraphers’ Association and the newspaper apparently went out of existence in 1905, but the experience showed Coaker that in trade unionism he could establish a political base independent of St. John’s and its political parties. It also further whetted his appetite for journalism. 141

MAINTAINING PUBLIC PROFILE

46 Coaker promoted the growth of the Loyal Orange Association in Notre Dame Bay and this broadened his contacts in the area. Between 1900 and 1910 the Order experienced substantial growth in Newfoundland as residents in predominantly Protestant communities established lodges to provide fellowship and charitable assistance for members, such as funds for widows to pay funeral expenses and relief for members who had material losses due to fire and other disasters. Since its establishment in Newfoundland in 1863, the Orange Order often provided a means for Protestant politicians in St. John’s to organize the Protestant vote in Conception Bay and Trinity Bay at election time. 142 In 1900, there were 67 lodges with 4,189 members; by 1910 the corresponding numbers were 154 lodges and 14,029 members. 143 The local lodges served as community social centres, and lodge meetings provided a forum for members to discuss public issues and rules of debate. Coaker’s political ally, Donald Morison, was the Grand Master of the Order, having been elected in early 1903 to that office after previously serving as Grand Master in 1886 and again from 1888 to 1896. Coaker attended the annual session of the Order held on 8 February 1905 at Topsail as a representative of Port Blandford Lodge 100, which had been established in September 1904. At this session, the branch representatives, including Coaker, signed a resolution endorsing their support of Morison, who had been the object of severe criticism from Bond and his supporters during the 1904 general election. 144 The growth of the lodge in Notre Dame Bay reflected Morison’s efforts to counterbalance the influence of the Bond Liberals in the area. Coaker organized the Herring Neck Lodge, 145 which held its first meeting on 20 April 1905 and adopted the name “Truth,” with its officers being installed by representatives from Crosby Lodge, Twillingate. 146 His leadership in the Order can be seen in a letter Coaker wrote the press on 7 March 1907 thanking the Provincial Grand Lodge, which now consisted of 130 lodges and 12,798 members, for its decision to select Lewisporte as the 1908 site for the annual session. With 23 lodges in Notre Dame Bay and a membership roll of over 2,000, Coaker predicted that Lewisporte would be “equal to the occasion” in hosting the first Grand Lodge session held north of Whitbourne. 147 On 4 December 1907 Coaker was elected the Worshipful Master of Truth Lodge at the Herring Neck Lodge’s session, providing him at last with a more formal position of leadership in the community. 148

47 Coaker also remained a public figure by writing occasional columns for the Free Press. His contributions provided local news on the Herring Neck area and were part of the regular columns from various contributors around Newfoundland the Free Press featured about outport communities. 149 His restless spirit for political change could not be stilled and he became more closely allied with Morison, remained opposed to the Bond government, and supported an opposition Tory faction led by Morison and Free Press editor John Robinson that considered Alfred Morine (re-elected in Bonavista District in 1904 and the leader of the Opposition in the House of Assembly) an obstacle to getting rid of the Bond government at the next election, scheduled to be held in 1908. 150 On 11 November 1905 Coaker wrote the Free Press suggesting the formation of a new political party for Newfoundland and calling for Morine’s resignation from politics; otherwise, “government by an alternative party is an impossibility. . . . Must the only remaining autocrat [Morine] in Christendom be permitted to lord it over us until some black disaster intervene, because pluck to organize a new Opposition Party is lacking in a few individuals in St. John’s? Surely Terra Nova possesses some public spirited men?” He was appalled that the government had added over $6 million to the public debt since 1900, “not one cent of which has been expended in progressive measures, and for which we may search in vain for a cent’s worth of assets. No people on the face of the earth would tolerate such a policy of madness, but Newfoundlanders.” The measures Coaker had in mind included “the cry for prohibition,” for he would assert in 1915 that he was a “lifelong abstainer from the use of Liquors,” 151 and he also called “for civil service reform, for universal schools, for redistribution of seats and single districts, [which] cannot longer be ignored.” His letter to the Free Press was a call to outport Newfoundland to take its place equally with St. John’s at the legislative table. He wrote that “in the formation and organization of such a party the outports should insist upon being recognized. The future must teach St. John’s that the capital contains but one-eighth of the colony’s population, and is depending absolutely upon the outports for maintenance, commercially and politically. The country wants a new political party, and a new political party it must have, and that without delay.” Coaker regarded Whiteway, Morison, and William Howley, a popular St. John’s lawyer and union organizer, as possible leaders of this new party and publicly asked them to respond to his call. 152

48 Coaker hoped that Morison would fund a newspaper at Lewisporte with himself as editor because farming had produced little financial gain for him, he told Morison. In response, Morison informed him in September 1906 that he had not forgotten the newspaper idea, but was more concerned presently with the behind-the-scenes organizational work while acknowledging that Coaker’s temperament was such that Coaker believed nothing was being done politically “unless you are fighting somebody or exerting yourself in some direction to the full measure of your strength.” With the Reids’ financial support, Morison’s efforts had succeeded in 1906 in persuading Morine — “the greatest obstacle to party unity” — to retire from local politics. Political calm was critical during the last few months in 1906, he wrote Coaker, for it allowed the Opposition to get organized and for Morison to secure the nomination for a forthcoming by-election in Bonavista District (won by acclamation by Morison) when Morine’s resignation created the vacancy. 153

49 From the perspective of his later busy life after 1908, this stage of his life at Coakerville he later publicly regarded as one of the happiest of his life — the “wind, storm, calm, the trees, birds, sky, the sunrise and sunset, the snowstorms, bay ice, the work caring for cattle and working in the woods, sleighing on the open Bay, was all a pleasure.” The winter evenings and Sundays gave him “leisure for reading and study and whatever I worked at I always found myself drifting away to thoughts of the toilers’ life and its hardships, while so many lived lives of ease and luxury without toiling or producing.” 154 By 1910 Coakerville contained 1,000 acres with 40 acres under cultivation. His buildings at the farm included a dwelling house, a storehouse attached to the dwelling house, a workshop, a wood-house, a two-storey barn “50 x 50 feet upright” with a detached cellar of “300 barrels accommodation, with green house over,” and a poultry house. There were, as well, a “substantial wharf with store and a fully-equipped lobster factory thereon.” The property was “well fenced and laid out with suitable cattle and poultry yards.” 155 The farm was stocked with the best breeds of sheep (purebred Shropshires) and cattle.

50 Besides the Kearleys, among the fishermen friends who regularly visited Coakerville were John Clair of Boyd’s Cove and Patrick Dwyer, George Mercer, William Freake, Levi Freake, and Edward Richards. 156 John Clair was the most prominent in his life. In many ways, Clair, whom he had known since 1893, was about the age of Coaker’s late father, and he and his wife, Ellen [Dwyer] Clair, often served as surrogate parents for Coaker. He made regular visits to Clair’s farm and Clair “visited us at Coakerville and we made his dwelling our home when at Boyd’s Cove. Honest, fairminded, industrious and reliable he became to us as a second father. When absent from Coakerville we always corresponded.” Clair was a “splendid type of man, intelligent, industrious, contented, broad-minded, a good neighbour and a loyal Catholic. . . . He possessed an excellent memory and democratic ideas.” He told Clair about anything he read and the two men “discussed the points raised and entered into the soul of the thoughts expressed, and we began to discover that our ideas in many ways coincided. . . . Many an hour I spent listening to him relating his life experiences which were intensely interesting. I talked to him for hours of the fishermen’s handicaps and hardships.” Clair would become “one of the strongest Union members in Green Bay,” and he debated his “idea of a Union with him four years before the Union started. He closely followed the drafting of the Constitution of the F.P.U. and he was one of the men we confided in when drafting the Constitution. He followed every step in its formation closely and did all in his power to encourage me by word and deed. He is indeed one of the fathers of the F.P.U.” 157

51 Despite his prominence in the Orange Order, Coaker was broad-minded and supported social causes among other denominations. Among his close friends were several Roman Catholics with whom he discussed his draft constitution. Besides John Clair, another friend who examined and made suggestions for the proposed constitution was the Roman Catholic priest, William Patrick Finn, who strongly supported efforts to improve social and economic conditions of fishermen and sealers and whom Coaker first met in 1897 at Tilting, on Fogo Island, when Finn was a parish priest there. 158 During the winter of 1906-07, Coaker put the finishing touches to the constitution of a union that he had first proposed in the winter of 1904-05. 159 The union, he thought:

He discussed it with friends in the area and with his farmhand, Charlie Bryant, who had come to the farm in 1901 as a 13-year-old from the Church of England Orphanage in St. John’s. 160 Byrant, Coaker wrote, “although not a talker, has good judgment and I discussed each point with him as we chopped timber together in the forest on winter days. I drafted and redrafted the sections, erased some and added others until in 1908 it was ready for use.” 161

WIFE ABUSER?

52 In 1908 Coaker’s family difficulties came to a head. In December 1901, he had married Jessie Leah Cook of St. John’s and their only child, Camilla Gertrude, was born in August 1902. Apparently, Coaker had married to provide a companion for his sister, Emma, who had married Edwin Kearley and in 1901 had been living at Coakerville helping out on the farm. 162 However, in September 1902, 28-year-old Emma died from complications following childbirth. 163 Now, as Coaker was planning a union for fishermen, his marital union with Jessie was collapsing around him. His sister-in-law, Eliza Strong, took out a complaint against him in October 1908. She alleged, through her lawyer, Martin Furlong, that Coaker “did, on several occasions during the past six months, unlawfully assault, beat and ill-treat the complainant’s sister, at Coakerville, and she fears that the accused will do the same bodily harm, and requires him to show cause why he could not be bound over to keep the peace and be otherwise dealt with according to law.” As a result Judge James Conroy ordered Coaker to appear before his court or before one of the justices of the peace within Newfoundland to “answer to the said charge and to be further dealt with according to law.” 164

53 “One fine day a man in civilian clothes called at Coakerville,” Coaker recalled four years later, “finding us at work about a barn. After a half hour’s conversation he informed us that he had a warrant for our arrest, and read it, Mrs. Coaker being present. We at once arranged to proceed to Herring Neck, ten miles away, and gave bonds before our arch enemy Lockyer for our appearance at St. John’s in ten days. We gave Mrs. Coaker instructions to leave and proceed to St. John’s.” 165 Coaker appeared before the Justice of the Peace James Lockyer at Herring Neck on 10 November, where Coaker promised to pay the Crown $200 and to appear before Judge Conroy at St. John’s on 17 November. Two friends, Robert Dally and Edward Richards, each promised to pay $100 and all three offered their property to support the bond payments. Appearing before Conroy on 21 November, the charge was “assaulting, beating and ill-treating Jessie Coaker during the past 6 months.” The matter was settled between William and Jessie Coaker by a separation agreement between the two whereby Jessie only wanted support for their daughter, Camilla. 166

54 Coaker acknowledged publicly in 1912 that this agreement provided:

Coaker said in 1912 that his marriage had had difficulties and that the six months prior to his 1908 court appearance had been “six of the most passable months that Coaker and his wife spent together.” Eliza Strong’s charges had been a “base slanderous falsehood, made probably because of slanders communicated to her by her sister, but nevertheless untrue. . . . Had the case come before the Court, and we were given justice,” he told the public in 1912, “we could have shown that we were not to blame in the matter.” Coakerville proved to be an inhospitable and lonely home for Jessie Coaker.

Rather, “no greater blessing can be bestowed upon a man than the possession of a good wife, but no greater curse ever befell a man than to possess a bad one.” 168 The daughter subsequently lived with her mother in St. John’s and Coaker supported the daughter; his estranged wife refused to accept any financial assistance from him. The daughter later acknowledged to her father that she never blamed him completely for the marital breakup. 169

BIRTH OF THE FPU

55 Contemporaneous with Coaker’s marital problems in 1908 were his efforts to organize the fishermen of Newfoundland into a union. Notice of the pending meeting had been placed in the weekly St. John’s Plaindealer, a liberal-minded newspaper established in mid-1907; its editor was his friend Patrick Devine, who, having already written several articles about the need for fishermen to organize, welcomed the formation of a fishermen’s union. 170 The notice, dated Herring Neck, 25 October 1908, declared that “it has been decided to establish a FISHERMEN’S PROTECTIVE LEAGUE through the length and breadth of the Island, and the first start is to be made at Herring Neck on November 3rd. After that date any Settlement in the Colony containing fifty male fishermen over the age of eighteen may have a Branch of this League established.” Unlike the secrecy of “Promoter” in 1903, this time Coaker stated in the notice that forms of application and copies of the constitution could be obtained upon application to him at Herring Neck. He declared that the “time has come for organization on behalf of the fishermen’s interest, and the 50,000 fishermen of Newfoundland, regardless of creed or party, are invited to stand shoulder to shoulder, through this League, in defence of their financial interests.” 171 The 1908 fishing season was a particularly favourable time to act because,although there had been a good catch, prices were half of what they had been the previous year.

56 He called a public meeting for the night of 2 November, 172 the same date as the general election in which Bond encountered a strong opposition led by his long-time rival, Edward Patrick Morris, a St. John’s populist politician who had been first elected to the House of Assembly in 1885 as an independent in the three-member District of St. John’s West. He had broken ranks with Bond in 1907, ostensibly over a disagreement about the rate of pay for road labourers in St. John’s. In March 1908, at a meeting of sealers in St. John’s, Morris formed the People’s Party, with a broad appeal to the labouring population. The result was a tie election requiring another vote the following year, with Morris easily defeating the Bond Liberals.

57 To keep his proposed movement politically neutral, although he favoured Morris in the election, 173 Coaker waited until election night to hold the public meeting at Herring Neck in that community’s Orange Lodge Hall. The meeting was attended by over 250 men. It was, Coaker later said, the occasion of his first public speech and he was initially nervous, but he found his confidence and spoke for nearly two hours. Coaker then adjourned the meeting and convened it again the next night, when he spoke to another full hall for two hours. With the public meeting over, Coaker convened a union meeting and 19 fishermen stayed behind and approved a constitution for the proposed union, electing Coaker as its first president and with Herring Neck having the distinction of having the FPU’s first council. The 19 men were mainly his staunchest friends over the past two decades from his having lived in the Herring Neck area. On 4 November, Edwin Kearley, the newly selected Herring Neck FPU Council Secretary, wrote the press announcing the formation of a fishermen’s union with the adoption of a constitution and election of officers. He stated that “every fisherman should become a member and assist in securing for their class rights and benefits always denied and which can only be secured by organization.” 174