Articles

“A Square Deal for the Least and the Last”:

The Career of W.G. Smith in the Methodist Ministry, Experimental Psychology, and Sociology

INTRODUCTION

1 Although it is a convention for authors to seek anonymity by using initialized pen names, W.G. Smith is an exceptionally anonymous name. “I have no photograph, not having visited a photographer in ten years,” he wrote in April 1921. “I shall have to ‘sit,’ if you desire one, but I thrive best in obscurity.” It is this modesty that is responsible for W.G. Smith’s (1873-1943) obscurity. He should be remembered today as a Newfoundlander who contributed to the intellectual life of Canada before Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949. Salem Bland (1859-1950) in his book The New Christianity; or, The Religion of the New Age — a key text for the social gospel movement — acknowledged an intellectual debt to two people, an editor and “my friend, Professor W.G. Smith of the University of Toronto, who gave me valuable criticisms and suggestions” (Bland, 1973: 6). Smith was also a friend of another important intellectual figure in Toronto, the philosopher George John Blewett (1873-1912). Among all the nineteenth- and twentieth- century idealist philosophers in Canada, Blewett may be the most significant for a rational Christian understanding of the relationship between humans and nature (Armour and Trott, 1981: 321). Blewett is the author of The Study of Nature and the Vision of God (1907) as well as The Christian View of the World (1912).

2 Born in the town of Cupids in March of 1873, W.G. (William George) Smith is surely the first Newfoundland-born experimental psychologist. He taught psychology at the University of Toronto for about 15 years, but the surviving record provides more insight into his work as a Methodist minister and his contributions to the study of immigration, although he wrote in an era sometimes referred to as the “prehistory” of sociology in English Canada (Brym, 1989: 15). 1 The diversity of Smith’s career may seem puzzling today. One might wonder if it is intellectually consistent to be a Christian minister and a laboratory psychologist interested in sensory perceptions, a social reformer, and a sociologist, but multi-faceted careers were typical of the social sciences in Canada in the early twentieth century. Smith published two books, A Study in Canadian Immigration (1920c) and Building the Nation: A Study of Some Problems Concerning the Churches’ Relation to the Immigrants (1922). He was also the author of at least one study in experimental psychology; three articles about immigration in the Canadian Journal of Mental Hygiene; and three articles in the journal Social Welfare, one of which is about immigration. The Canadian clergy who conducted surveys related to immigration in the first three decades of the twentieth century can be divided into three categories: clergy who defended an exclusionist immigration policy; those who ranked ethnic minorities in terms of the ease with which they could be assimilated in Anglo-Canadian society; and those who were more accepting of non-white newcomers and justified limited cultural diversity (Christie and Gauvreau, 1996: 188). Both of Smith’s books illustrate the third category. This is particularly evident in Building the Nation.

3 After introducing information about Smith’s formative years in Cupids and St. John’s, this article explores his career in Toronto as a psychology instructor and Methodist minister. Filling the gaps in the public record of these institutions requires that we turn to accounts of the life of the boy from the outports who became the grand old man of Canadian poetry, E.J. Pratt. Smith and Pratt had much in common: both were Newfoundlanders; both were ordained Methodist ministers, privately skeptical about some of the most fundamental church doctrines; both were students and instructors at the University of Toronto; and they were fascinated, at least in their younger years, by the new science of experimental psychology. They were nine years apart in age. Pratt was from Western Bay, an outport about 50 kilometres from Cupids. Following the appearance of his first book, Smith was appointed a professor of sociology at Wesley College in Winnipeg. This paper reviews the extensive negotiations pertaining to the appointment because they reveal information about his religious beliefs. Two outlines for his planned sociology courses are analyzed for their insight into his knowledge of sociology.

4 The title of this article comes from a letter Smith wrote on 28 March 1921 (quoted in full below). A “square deal” means fair, honest, and straightforward treatment. The term appears twice in Smith’s letter. In the first instance he was criticizing Methodists for their unjust treatment of Salem Bland. However, the term has broader implications. In the second instance he referred to the importance of striving for a “square deal ‘for the least and last.’” The quotation is an allusion to Jesus’s parable of the workers in the vineyard (Matthew 20:1-16) and might thus symbolize Smith’s vision for Canada.

5 According to an obituary published by the United Church, “The Reverend William George Smith was born in Newfoundland in a family that for generations had engaged in fishing. Mr. Smith served with his father’s fishing fleet for a few seasons and following the depression . . . of the early nineties he decided to seek other fields of labour.” 2 The baptismal records for the two oldest Smith children at the Brigus Methodist Church give the occupation of W.G.’s father, Thomas, as “fisherman” in 1867 and the following year as “planter.” Alice (Ogden) Smith, wife of W.G.’s brother James, is the author of a Smith family history. She writes that Thomas Smith had no schooling. As Thomas’s mother was a widow, he went to sea at an early age and “later in life he learned to read, write and ‘figure.’”

Alice Smith states that Thomas formed a partnership with two of his brothers (William and George). The three brothers engaged in the spring in the sealing industry and from June to October fished near Manak Island in northern Labrador. Their first ship was a brigantine they called the Garland. Alice Smith also gives information about the education and religious faith of W.G.’s mother, Emma, who was the eldest daughter of William and Patience Nosworthy:

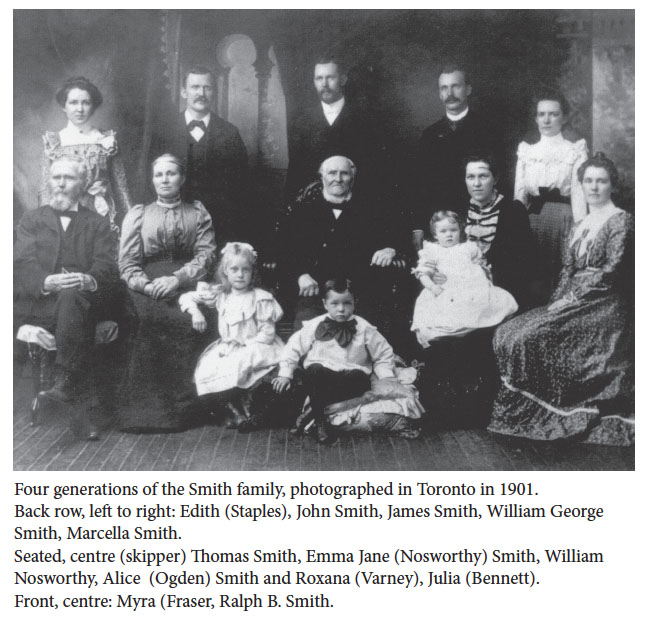

6 A photograph of Thomas, Emma, and their six adult children in 1901 shows a prosperous middle-class family that could surely afford to send two sons to university (James and W.G.). 3 Partly through self-study and by studying at the Methodist “College” in St. John’s, W.G. was able to pass the London University Matriculation Examination. 4 The Methodist College would have been one of the best institutions in Newfoundland for completing high school. Smith was fortunate in being able to attend the college in its heyday when Robert Holloway served as principal. Holloway appears to have been the most interesting educator in nineteenth-century Newfoundland, judging from Ruby Gough’s biography (2005). The school’s curriculum was unusual for its time because Holloway placed so much emphasis on the natural sciences.

7 Smith was granted a leave of absence from the University of Toronto during the academic year 1909-10 and visited Germany. On his return voyage in the summer of 1910 he stopped in Newfoundland where he spent several weeks (Anon., 1910a). In addition to giving a sermon at a local church in Cupids he was a speaker during the John Guy Tercentenary Celebration, which was reported in the St. John’s newspaper, The Daily News:

8 Malcolm MacLeod’s research on Newfoundland students studying abroad between 1860 and 1949 shows that one-third of the students did not return to live in Newfoundland. In terms of occupation, clergymen were the least likely to return (MacLeod, 2003: 18), perhaps because there were so many opportunities for work in the ministry. In Smith’s (1921a) case, he became such an ardent Canadian nationalist that he was not willing to write a letter of recommendation for one of his students to teach at an American university because Canada was “big enough for any of us.” Nonetheless, Smith was attached to his homeland. He grew up at the ocean’s edge in a classic Newfoundland outport. The town of Cupids has a beautiful and dramatic setting and it has a unique history as the site of the second oldest permanent English settlement in North America. But I am not aware of any writings in which he mentions Newfoundland. Hopefully, family letters will surface some day and reveal more about his attitude to the island.

9 Although the Smith family may have been prosperous by Newfoundland standards, economic disparities in Cupids would have been relatively small. This characteristic, plus the traditional network of mutual aid in rural Newfoundland (Whitaker, 1988: 82-83), may have made Smith more receptive to the message of the social gospel. Also, it is conceivable that he became more committed to promoting social equality because he knew that Methodist ministers on the island had rarely criticized merchants for the credit system that exploited fishers (Hollett, 2010: 99). In Shouting, Embracing and Dancing with Ecstasy: The Growth of Methodism in Newfoundland, 1774-1874, Calvin Hollett arguesthat one reason fishing families tended to be so religious was because fishing and sealing were exceptionally dangerous occupations. We might speculate that excessive claims of God’s special providence helping sealers and fishers survive disasters (Hollett, 2010: 85-96) might have made Smith uneasy about the supernatural elements in traditional Christianity.

METHODIST MINISTER AND PSYCHOLOGY INSTRUCTOR

10 In every generation since the mid-nineteenth century Newfoundlanders have left the island to pursue higher education (MacLeod, 2003: 4-25). In Smith’s time there was no alternative because Newfoundland did not have a degree- granting university. He chose to study at Victoria University (in the University of Toronto). Smith entered in 1895 and graduated four years later. His undergraduate education in the natural sciences included courses in physics, biology, and optics, and he also took two courses in psychology, probably the courses called “general” and “experimental” psychology. On the basis of his undergraduate education, he could not have made a convincing claim to be a philosopher, although he did complete undergraduate courses in ethics, the history of philosophy, metaphysics, and the theory of knowledge (Smith, n.d.: 1). Victoria University was located in a burgeoning metropolis, downtown Toronto. Students had ample opportunities to become active in organizations grappling with the social problems that were the focus of reform during the Progressive Era. It is also significant that Victoria University had a reputation as a school influenced by liberal theology (Grant, 1989: 90). 5

11 Smith was president of his class at Victoria; an active member of the Union Literary Society, whose objective was the “cultivation of literature, science and oratory”; chairman of the Missionary Committee; assistant business manager for the student publication Acta Victoriana; and played on the school’s hockey team. 6 W.G. Smith married Ella Blanche Silver, who was from North Gwillimbury, Ontario, on 26 August 1903. In 1904, five years after completing his B.A. degree and a few months after his thirtieth birthday, Smith was ordained a Methodist minister. His studies in theology were also completed at Victoria University.

12 According to the historian Phyllis Airhart (1992: 8), the evolution within the Methodist Church in the late nineteenth century from revivalism (that is, individual salvation) to progressive politics was relatively easy. The end result — sometimes referred to as the secularization of the faith or serving the present age — may seem a radical departure. But she argues that Protestant churches had always emphasized personal salvation through faith in Jesus along with charity and care for other people. Historically, the emphasis was on faith. These two dimensions of Protestantism might be referred to as the personal gospel and the social gospel. Smith (1922: 164) penned a classic example in Building the Nation: “It will not do to say that problems of industry are not any part of the church’s work, which is to preach the gospel and save souls. Wherever a human being suffers want, or injustice, or misfortune, or cruelty, or neglect, or mal-adjustment, there must be present the stabilizing, adjusting, healing hand of the Church.” The social gospel movement is thus not a radical departure from tradition or a result of anti-intellectualism associated with revivalism, but rather is a shift in emphasis to charity towards and care for others. Charity became more important than faith. If Airhart is correct, fundamental changes in popular ideologies can sometimes result from slight modifications of familiar ideas (Airhart, 1992: 62).

13 It is, of course, possible to be a theological liberal and a political conservative or vice versa. Emphasizing the diversity within the social gospel movement in the years 1890 to 1914, McKillop (2001: 219-20) argued that three ideas united all the factions: people are fundamentally good; society requires greater social equality; and it is essential to encourage a stronger sense of social consciousness. The social gospel movement in Canada coincided with a period of relative prosperity. Many Canadians feared a possible breakdown of social cohesion due to growing income inequality. Many thought that religious idealism was the only enduring foundation for social reform (Airhart 1992: 77).

14 Followers of the social gospel understood “sin” as a consequence of social conditions as much as individual moral failings. Some argued that the competitive nature of capitalism was inconsistent with Christianity and that if Jesus were alive today, he would be a socialist. Moral reform required an accurate understanding of how institutions function. The reforms they encouraged were temperance, women’s suffrage, abolition of child labour, promotion of labour unions, and the assimilation of immigrants. Sociology was the academic discipline best suited to provide the information that would help solve these problems (Campbell, 1983: 43).

15 Liberal Protestant churches played a key role in introducing the social sciences in Canada during the first two decades of the twentieth century when the social sciences were not well established in universities (Christie and Gauvreau, 1996). Wesley College, Victoria University in Toronto, and the United Theological College in Montreal were pioneers in teaching sociology and psychology among church-affiliated colleges. As early as 1898, Victoria University introduced divinity students to political economy (ibid., 82). In 1906 Wesley College offered the first sociology course at a Canadian institution of higher education (Valverde, 2008: 129). At least as early as 1912 Protestant theological colleges affiliated with McGill offered Christian sociology courses (Shore, 1987: 50-51). In 1919 Victoria University appointed the first chair of Christian Sociology in Canada, the Presbyterian minister John Walker Macmillan (Christie and Gauvreau, 1996: 83). Almost every social survey undertaken in Canada in the 1920s was sponsored by Protestant churches or directed by clergymen (ibid., 183-92). Finally, it is typical that the man who was the major Canadian sociologist in the 1920s, Carl A. Dawson, completed a degree in divinity (Shore, 1987: 66).

16 From letters of recommendation written a dozen years later, it appears that as a young man Smith was not a successful shepherd of his flock. He thus made a living by combining university teaching with the ministry. His work with the Methodist Ministerial Association of Toronto in the late 1910s and early 1920s seems to be the most substantial (or at least the most recognized) aspect of his religious engagements. The following is part of a resolution that was passed unanimously by the association and reproduced in the magazine The Christian Guardian.

17 From 1905 to 1921 W.G. Smith taught experimental psychology in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Toronto. Psychology was normally taught in philosophy departments until the introduction of experimental psychology, which was defined as a natural science. Psychology had more popular appeal once it was separated from philosophy because the laboratory procedures and apparatuses fascinated the public (Shore, 2001). The University of Toronto is thought to be the home of the first experimental psychology laboratory in the British Empire. Modelled after the pioneering laboratory established in Leipzig by Wilhelm Wundt, the Toronto laboratory was founded in 1890 by the renowned American psychologist James Mark Baldwin. In 1894 Baldwin left Toronto and was replaced by one of Wundt’s best students, Augustus Kirschmann, who made the Toronto laboratory a centre for the study of such topics as the perception of colour and the role of colour in aesthetics. This might seem like trivia — and at odds with the world view of an undergraduate student who once read a paper at a missionary conference titled “The Best Lines of Approach to Non-Christian Nations on the Part of the Missionary” — but the perception of colour had been taken for granted for generations. 7 Once it was understood that not all people see the same colours and that cultures categorize colours differently, the subject came to have greater social significance. The focus on colour was also motivated in part by occupational safety concerns related to some occupations. More broadly, it might be understood as one aspect of the fascination with the visual that characterized the late nineteenth century (ibid., 75-76).

18 Unfortunately, W.G. Smith missed the most exciting period in the laboratory’s history because he entered Victoria University in 1895, a year after Baldwin’s departure. Professor Kirschmann is described as ambitious and hard-working but in 1908 he requested a leave of absence from the University of Toronto. He suffered from ill health in Germany and never returned to Canada. John G. Slater, in his history of philosophy at the University of Toronto, recounts that university administrators then tried to get by as cheaply as possible by not seeking a prestigious psychologist to replace Kirschmann. W.G. Smith, whose highest degree was a B.A., would have been one of the cheap replacements. Nonetheless, Smith became one of three professors saddled with most of the teaching in psychology, including instruction at the graduate level (Slater, 2005: 198-99). 8 By the time he resigned on 30 June 1921 he had become the highest ranking member of the group teaching psychology (ibid., 199), although he seems to have published only one brief professional article, a study of the perception of black, grey, and white (Smith, 1907). Roger Myers (1982: 95) claims that Smith’s career as a psychologist was limited because he was not gifted at doing laboratory work. Perhaps this is true, but Myers may have underestimated Smith’s heavy teaching load and the time he devoted to the ministry. Despite lacking a credible publication record in psychology, Smith was allowed to teach an impressive range of courses at the graduate level.

- (a) Introduction to Psychology, to lead up to (b) Methods and Tasks of Social Psychology

- Psychology of Sight and Hearing in their Relation to Higher Mental Processes, or (b) History of Psychophysics

- Tests of Intelligence

- Studies in the Psychology of Religion

- Modern Doctrines of Space

- Categories of Experimental Psychology

19 The most intriguing course for deciphering Smith’s opinions must have been the psychology of religion, which would surely have fostered a secular perspective. Psychological studies of religious conversions were widely read at the turn of the twentieth century and were controversial among Methodists because of the weight they had placed on the emotional experience of conversion. Some people began to see revivals, even by mainstream churches, as psychologically dangerous (Airhart, 1992: 98-103). As we shall see, Smith was ambivalent about the revivals conducted by the popular evangelist Billy Sunday. Unfortunately, there is not enough information about Smith’s course on the psychology of religion to speculate further about his own ideas. 10 Courses on topics such as the psychology of sight and hearing and the methods of testing intelligence must have sometimes appeared to a minister to be a distraction from the important things in life. Social psychology, on the other hand, would have allowed Smith to get out of the laboratory, if he wanted, without altogether renouncing laboratory-based research. It was not unusual for instructors to teach both experimental psychology and social psychology. Embracing sociology early in his career would not have made sense financially. Half a century would pass in Canada before there would be a thriving market for sociologists. 11

20 The poet E. J. Pratt (1882-1964) was actually a demonstrator in laboratory classes Smith taught at the University of Toronto. “W.G. Smith regarded [Pratt] as an impractical dreamer, if not an utter nincompoop, and let his assistant know exactly what he thought of him” (Pitt, 1984: 149). More importantly, Smith supervised Pratt’s Ph.D. thesis in philosophy, Studies in Pauline Eschatology and its Background. This topic was inspired by the new historical-critical methods for understanding the Bible that had become popular and were creating problems for fundamentalists, who believed in a devotional and literal reading of the scriptures. These methods challenged the veracity of the Bible and disputed its authorship. It is difficult to imagine a topic more remote from experimental psychology, but it made sense for an ordained minister to supervise a thesis about concepts of the afterlife even though his academic degrees were inferior to those of his student. Pratt concentrated on the historic intellectual environment that influenced the apostle Paul.

21 To a non-specialist, Pratt’s thesis appears to be an impressive intellectual study of the complex, evolving, and imperfectly recorded religious beliefs of a “primitive people” (Pratt’s term). However, the thesis is so far from being a study in psychology that it is not clear why the claim was allowed to stand. Pratt’s major biographer depicts Smith as an unpleasant, emotional, and demanding supervisor.

22 There is evidence — from more than one source — that some students found Smith to be “an incisive, inspiring, interesting teacher.” 12 I think this vignette about Pratt and Smith is misleading. Only one side of the conflict is given. It is not unusual for Ph.D. students to have disputes with supervisors. Smith supervised Pratt at a time when the student’s professional life was rather unfocused, thus probably adding to his already unfavourable impression of his fellow Newfoundlander. 13 Incidentally, not every page in Smith’s major publication, A Study of Canadian Immigration, is characterized by academic dispassion. For example, the book concludes with an anecdote about a self-sacrificing rural teacher in Saskatchewan, Peter Yeman, who gave his life helping immigrant farmers and “joined the ranks of the immortals” (Smith, 1920c: 400).

23 Smith’s relationship with experimental psychology may have paralleled that of his student. How else are we to account for the fact that his publication record in experimental psychology is so slim when he found time on weekends and in the summer to write a 400-page book about immigration? In 1913 Pratt published an enthusiastic paper in the student journal Acta Victoriana about the promise of experimental psychology. Soon Pratt became disillusioned about the limitations of laboratory experiments as a method for understanding human behaviour. For financial reasons, and perhaps status, Smith may have found himself trapped in the role of psychology instructor. Academic positions did not pay overly well (Shore, 1987: 37-38), but academic remuneration probably exceeded that for the ministry. Smith’s annual salary as an assistant professor at the University of Toronto in 1913 was $2,100, about three times the average annual income for wage earners in Toronto at that time; 14 after five additional years of teaching and promotion to the rank of associate professor, his annual salary was increased to $2,850 (Slater, 2005: 199). The role of academic psychologist could also have given him credibility as a social critic trying to create a more sensible immigration system.

A STUDY IN CANADIAN IMMIGRATION

24 a Study in Canadian immigration provides a detailed analysis, accessible to general readers, of government statistics on immigration. The volume is an important contribution to one of the major social problems in early twentieth- century Canada. The demobilization of 1,000 Canadian soldiers per day at the end of World War I was widely perceived as a serious social problem, but immigrants had been arriving in Canada at the rate of 1,000 per day for over a decade prior to the war (Smith, 1920c: 115). To use the language of the time, Smith worried that too many “defectives” were arriving, newcomers who had minimal job skills and who were illiterate as well as physically and mentally challenged. They were unlikely to succeed. Sixty-one statistical tables provide a factual basis for critiquing the public’s misperceptions about the ethnic groups responsible for the largest number of undesirables. Statistics proved that a surprisingly high number of British immigrants were deported as undesirables. Smith also refers — favourably — to the British as a mongrel race. “The Canadian stock was not ‘pure’ to begin with, and the Anglo-Saxons, as the name implies were not ‘unmixed’” (ibid., 349).

25 In Smith’s opinion, the American reception of newcomers was far superior to the Canadian alternative. He proposed that the Canadian government build facilities like those on Ellis Island in the harbour of New York City so that immigrants could be housed for several days and thus closely evaluated before being admitted to Canada (ibid., 324-28; see also Clarke, 1920: 11). After summarizing the history of immigration to Canada, Smith discussed the anticipated demographic consequences of the Immigration Acts of 1910 and 1919, which added safeguards for the reception of immigrants, better monitoring of transportation companies, definitions of moral and political offenders, and specified penalties for profiteers who induced foreigners to immigrate to Canada with false promises (Smith, 1920c: 92-113, 353-64). Some of the most eloquent passages in a Study in Canadian immigration are critical of white Canadians for their lukewarm reception of foreigners:

26 Some readers of a Study in Canadian immigration have misperceived Smith’s values due to his use of what today is considered politically incorrect language, for example “the alien” (singular) and “the refuse of the tide” of immigration. They have been less attentive to the passages that mark him as a left-wing social critic. Smith’s major publication is consistent with the social gospel emphasis on gathering and analyzing statistics related to social problems (Airhart, 1992: 125, 187). Smith (1920c: 383) argues that one of the better-known American sociologists, E.A. Ross, drew a “lurid” picture of the primitiveness of Eastern European immigrants. But even if the portrait were realistic, Smith says, it is the responsibility of Canadians to “show the helping hand.” Smith’s moving depiction of Eastern European immigrants at the conclusion of a Study in Canadian immigration is a discourse one would expect of a social reformer rather than an academic committed to an objective science.

27 Smith’s book is another twist in his career. Little of the content in this book suggests that the author was a psychologist, although the research was completed at the request of the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene and portions of the research were first published in the Canadian Journal of mental Hygiene (Smith, 1919, 1920a, 1920b). The volume might be described as “almost sociology” in that the theoretical component is very weak and the author lacks an understanding of the underlying economic and political forces responsible for an inadequate immigration system. Nonetheless, the reviewer in The Canadian Historical review (Mitchell, 1920) praised Smith for writing “the pioneer book on the subject of Canadian immigration.”

28 The reviewer in The Canadian Forum (identified as C.B.S., possibly C.B. Sissons) called a Study in Canadian immigration “one of the most important books of the year,” and he praised the chapter on East Asian immigration as the best presentation of the topic he had ever read. Smith wrote that the real reason for white Canadians’ objection to Asian immigration was not racial, social, or religious prejudice, but economic. Asians were willing to work longer and for lower wages, thus potentially lowering the standard wages and working conditions for the white population (Smith, 1920c: 174). C.B.S. complimented Smith’s analysis of government statistics while pointing out that the statistics were flawed. He also noticed that occasional lapses in style and a few errors indicated that Smith wrote a Study in Canadian immigration in his spare time. “Not infrequent eloquence and now and then a very welcome flash of humour amidst the statistics serve to show how a good book might have been improved could University authorities be brought to reflect on the derivation of the word scholarship” (C.B.S., 1920). 15

29 Another book historians consider to be a pioneer study of Canadian immigration is Strangers within our gates; or, Coming Canadians (1909), by another Methodist minister, J.S. Woodsworth. Written with the assistance of Arthur Ford, whose name does not appear on the title page, the volume reads like a scrapbook of fragments. The inconsistencies in Strangers within our gates are due to it being written by two authors who did not reconcile their differences and to its reliance on long excerpts from popular sources. 16 Although Woodsworth’s chapter “With the Immigrants” conveys a sympathetic image of newcomers, other chapters are quite judgemental (e.g., Woodsworth, 1909 [1972]: 112, 115, 144-52, 158). Strangers within our gates is often referred to today because of Woodsworth’s subsequent fame as a Labour member of Parliament and later as the first leader and the social conscience of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF). It is obviously inferior to a Study in Canadian immigration.

“THE SINCERITY THAT REGARDED ME AS PERFECTLY SAFE IN THE REALM OF EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY”

30 In 1921 Smith was offered an appointment at Wesley College, which was affiliated with the University of Manitoba. Wesley College is now the University of Winnipeg. Typical of the era, the job search for an administrator and senior professor was undertaken personally by the college president (or principal), John H. Riddell. 17 Riddell was head of Wesley College from 1917 to 1938. Between 400 and 600 students were enrolled annually at Wesley College during Riddell’s term as president, and the teaching staff included 20-some faculty members (Friesen, 1985: 255). The historian Gerald Friesen (ibid., 251) writes that Wesley College had been a hotbed of religious and social reform in the decade before World War I and that Riddell (1863-1952) was responsible for shifting the school in a moderate direction in the interwar period. Smith might have been viewed in 1921 as a man who appeared to strike a balance between the extremes of the social gospel and conventional Methodist evangelism. Friesen (ibid., 259-60) concludes that Riddell was actually “uneasy” with the academic side of serving as a university administrator because he lacked the skill and time to engage in scholarship. Riddell himself admitted that he was not a serious scholar. However, he was the first person to teach sociology at Alberta College in Edmonton; and he had studied sociology at the University of Chicago, the centre of early North American sociological research, although only for one summer (ibid., 260). As president of a small college, Riddell was expected to teach full-time (Latin, Greek, Bible studies, sociology), hold church services, and serve as the chief administrator. Friesen argues that Riddell was ill-informed about Smith’s religious beliefs. On the other hand, it would be strange for a university head to consider appointing a dean of theology at a religiously affiliated institution when he knew little about his religious faith. It will be evident, however, that Riddell was indeed ill-informed about Smith’s politics.

31 W.G. Smith may not have been the most inspiring preacher for a conservative congregation, but he was a popular speaker at gatherings of young people. His intellectual and social skills impressed Methodist leaders in Toronto. Given the paucity of information about Smith, the best assessment of his activities and character are the four letters of reference related to his appointment at Wesley College. The letters are very positive, as one would expect, but they do give some indication of the candidate’s weaknesses. The Rev. T.W. Neal, President of the Toronto Conference of the Methodist Church, recommended Smith in these words:

32 The letter of reference from the Rev. Jesse H. Arnup, Assistant Secretary for Foreign Missions in the Missionary Society of the Methodist Church in Toronto, is complimentary but mentions differing opinions about the public expression of religious ecstasy, which had been a prominent feature of Methodist churches, including those in Newfoundland (Hollett, 2010):

33 There is some evidence from Smith himself of his opinions about “red hot revival meetings.” In 1917 a delegation of Methodist ministers travelled to Buffalo to hear the evangelist Billy Sunday. As they were waiting at the train station to return to Toronto, half a dozen ministers were interviewed by a reporter from The Evening telegram. Smith was critical but diplomatic: “We are not interested in Sunday’s theology. . . . I doubt the wisdom of any of us attempting to imitate his methods. Most of us have our own. Our only purpose should be to catch a little bit of the supreme enthusiasm that possesses him and his. We have seen a human dynamo in action. I overlook the peculiarities, the slang and idiosyncrasies and see only the power that lifts men” (Anon., 1917b).

34 W.A. Creighton of The Christian guardian, in his reference letter in regard to Smith’s possible appointment at Wesley, noted that in recent years he, too, had formed a more sympathetic impression:

35 The fourth letter of reference (7 February 1921) is on the stationery of Victoria University. The referee writes that Wesley College would be “perfectly safe” in appointing Smith as dean as long as the appointment did not make jealous any staff members who had aspired to the dean’s office. The writer comments that Smith had a “good deal of shrewd judgment, a real interest in students’ progress, and experience of life, and he has overcome most of the deficiencies that naturally attend a man who has had to make his [own] way.” Smith is also described as an “exceedingly hard worker.”

36 The Wesley College president bargained with Smith over his salary and title because he had credible qualifications in theology and psychology — and with some future effort on the candidate’s part — in sociology. He may not have been satisfied at the University of Toronto but it was a secure position. He and his wife Blanche had four children to support and educate. He may also have hesitated to accept the offer because some people thought Salem Bland had been fired at Wesley College because of his liberal religious convictions. Others thought he was sacrificed because of the university’s financial problems (Horn, 1999: 50-52). On 8 March, Smith (1921b) wrote to Riddell reviewing all of the reasons why it made sense to reject an offer from Wesley College.

- (1) Hiring professors to teach the history of philosophy, ethics, sociology, and social psychology would be more consistent, he thought, with the mission of Wesley College than spending money on a psychology laboratory. It is not mentioned in the letter but Smith had served as secretary for the Massey Foundation’s report on the quality of secondary schools and colleges affiliated with the Methodist Church. The report recommended that Wesley College provide advanced instruction in sociology and ethics taught by “one highly qualified man, capable of doing advanced work” (Massey Foundation, 1921: 107) and that instruction in experimental psychology be entrusted to the University of Manitoba.

- (2) He claimed to have worked “very hard” for the past dozen years separating psychology from philosophy at the University of Toronto. By moving to Wesley College, he would “have to pull up stakes and move into a new field to do over again, largely, the pioneer work of a decade.”

- (3) There was the question of salary and job security. “I struggled for years against inadequate salary — it is not a struggle one likes to repeat.” His children were reaching the age of high school and university. Also, he anticipated that the union of Methodists and Presbyterians would occur in a few years and that this might make his position at Wesley College redundant.

- (4) Finally, he argued: “To abandon my work in Psychology and take up the work in Philosophy seemed like throwing away a great deal of my life’s labour. I have some interest in Philosophy, but only on a psychological foundation, and that standpoint is not closely in agreement with the prevailing views in Universities. Wesley deserves better things than a cold philosopher.” Smith anticipated that the president would consider him to be a “tenderfoot and a faintheart” for rejecting the appointment.

37 Only three days later, on 11 March, Smith (1921c) changed his position and telegraphed the president: “Abandon idea experimental psychology and laboratory[.] Offer me professorship philosophy and sociology with deanship. . . .” This immediately led to President Riddell asking Smith for his opinions about the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919:

38 That the relationship between these two future colleagues soured might be inferred from Smith’s ironical first paragraph. He began a serious letter with a joke. The president’s suspicion that sociologists are political radicals is an old myth based partly on fact. Smith did not hide his liberal religious views from the president, but distanced himself to some extent from Salem Bland. With modesty, Smith also highlighted his skills as a negotiator in the Methodist Ministerial Association. The concluding sentence suggests that the only legitimate politics may be choosing which version of socialism is best for Canada. But he was not more precise:

39 The special committee Smith mentions was a group of seven men charged with the task of rewriting the 1918 declaration by the Methodist Church of Canada concerning its attitude to industrial organization. When the declaration was perceived by some members of the Church as too left-wing, a new committee was formed that reflected the diversity of opinions within the Church about industrialization. However, the 1921 revision did not reject any of the basic principles of the original declaration. The revision committed the Church to freedom of expression for all political perspectives consistent with Christianity. Methodists were expected to be devoted to the common good, but there was no explicit attempt to state the political form this might take. The revision reminded businessmen that their concern should be “human welfare” rather than maximizing profits. “Destructive competition” in business was considered to be inconsistent with Christian brotherhood. All workers had a right to form labour unions. The revision contains one paragraph about the politics of immigrants, which must have been suggested by Smith. After recognizing that immigrants were arriving in Canada from most of the major “races” (i.e., ethnic groups) in the world, an explanation was offered for their politics: “They bring not only habits and modes of living consonant with their past history, but attitudes toward government and industry such as inevitably arise from a more or less embittered past” (Anon., 1921a; see also Thomas, 1921; Methodist Church of Canada, 1919: 399-401; Methodist Church of Canada, 1923: 405-07).

40 On 2 April Smith (1921e) wrote the president expressing his desire to be an administrator in a theology faculty. This was Wesley College’s advantage over the University of Toronto, which offered more security and academic prestige. The remark that theology is “only the verbal articulate expression” of religion might be consistent with the generalization that discussions of theological subtleties were not the strong point of the social gospel. It is also typical of the movement that he comments on religion’s service to the state in the idealistic terms of justice, mercy, and humility. Readers also get an impression of the time-consuming nature of Smith’s ministerial duties. This letter contains one of two references in Smith’s correspondence to “my friend” George John Blewett, who had graduated from Victoria University two years before Smith and had participated as a student in the experimental psychology laboratory at the University of Toronto before completing more courses in experimental psychology at Würzburg and Harvard (Paterson, 1976-77: 397).

THE BRIEF TENURE OF PROFESSOR SMITH

41 Smith was finally appointed Vice-President and Professor of Psychology and Sociology at Wesley College and began teaching in the autumn of 1921 (Matthes, 2011). This makes him, in a sense, the first Newfoundland-born sociologist. In the following months he wrote two drafts of outlines for sociology courses for the academic year 1922-23. However, he was fired before he had a chance to teach them. Wesley College was affiliated with the University of Manitoba. The outlines were probably written for submission to a board of examiners at the University of Manitoba, whose approval was required if new courses at Wesley College were to count as credit towards a degree.

42 Smith was planning to have his students read standard American textbooks. The fifteenth edition of William McDougall’s text had appeared in 1920, the sixth edition of Edward Hayes’s text in 1918. The first reading list — consisting solely of books in psychology — suggests that Smith produced this outline very quickly in order to satisfy bureaucratic demands, or that he was unprepared to teach a real introductory sociology course, or that he did not want to co-operate with a board of examiners at the University of Manitoba whose approval was required for the introduction of new courses. He did admit to a board of examiners on 10 January 1921 that what he called “sociology” was essentially social psychology (Lodge, 1923). His comment that experimental psychology forms the basis for sociology seems idiosyncratic today but the well-known psychologist William McDougall, for example, did argue that he would provide a theory of motivation that would be the basis for all the social sciences. 19

43 The second reading list includes a psychological perspective on social psychology (McDougall), a sociological perspective on social psychology (Ross), both now considered early classics in the discipline (Jahoda, 2007: 157-69), and two texts introducing mainstream sociology (Hayes and Carver). Supplementing these books is Harry Hollingsworth’s Vocational Psychology, a book in applied psychology about the forces influencing people’s choice of occupation and employers’ methods for evaluating job candidates. Thomas Nixon Carver’s Sociology and Social Progress (originally published in 1905) is an anthology of classic articles that would supplement an elementary textbook. Carver’s selection is eclectic because he thought that sociology was actually an old discipline and that some of the best ideas came from philosophers who never called themselves sociologists. Smith also went outside the canon to assign Bertrand Russell’s reflections on the causes of World War I.

44 With the exception of Charles Ellwood’s an introduction to Social Psychology, none of these books makes more than a passing reference to the men now celebrated as the founding figures of sociology: Karl Marx, Max Weber, and Emile Durkheim. Ellwood devoted several pages to Marxism, but readers would probably come to the conclusion that Marxism was a political philosophy rather than a valid theory for explaining the evolution of societies. Both Charles Ellwood (Turner, 2007: 135) and W.G. Smith emphasized education as the most effective way of solving social problems. While Ellwood (1917: 298) did claim that there was “much psychological and sociological truth” in Marxism, he emphasized the deficiencies. 20 Ellwood’s conclusions might give us some insight into Smith’s politics:

In 1922 Smith offered this proposal for moderating social inequality:

45 The president and governing board of Wesley College received a letter on 6 June 1922, bearing the signature of five members of Grace Church in Winnipeg and warning them that Smith was espousing ideas contrary to the doctrines of Methodism. Members of the congregation felt that they had to notify the president and board for the “cause of Christ in general” and for the good of the Methodist Church and Wesley College. The specific complaints were:

- He does not accept the Miraculous Conception and Virgin birth of our Lord Jesus Christ, declaring it to be a Romish invention of later ages;

- Does not accept the Resurrection of Jesus Christ;

- Declares that the significance of the Cross and our Lord’s Crucifixion consists in His willingness to suffer and die for His great principles, asserting that any further significance was added by the speculations of the Church of later ages;

- Does not accept the Gospel of John.

46 The split that occurred in the early twentieth century between professors/ clergymen and their more orthodox congregations is evident in the reactions from the members of Grace Church. They do not elaborate on the fourth point but the complaint was probably that Smith believed the Gospel of John to be less accurate than the Synoptic Gospels as a portrait of the historic life of Jesus. This was not an idiosyncratic opinion (Sanders, 1993). A supporting letter, also dated 6 June 1922 and signed by more than 30 people, requested that Smith be fired or forced to resign. “The above list could be increased to hundreds if the time were taken” was added by hand on the supporting letter. 21 Since J.S. Woodsworth had previously been a minister at Grace Church, the congregation should have been familiar with the more radical side of the social gospel. But it could have been the example of Woodsworth that aroused protests against Smith. The ordination vows of the Methodist Church did not require that a candidate for the ministry believe all of the church’s doctrines (McNaught, 2001: 50). Smith’s views are not so surprising for a university professor inspired by the social gospel movement (Marshall, 1992; Cook, 1985). Offered a year’s salary as an alternative to a timely notice of the termination of his contract, Smith was fired.

47 The letter from members of Grace Church is obviously a crude account of Smith’s opinions. The focus is solely on the ideas he questioned. It is possible to imagine Smith’s reply by combining ideas from the ministers and professors who were his acquaintances: Bland, Blewett, and W.B. Creighton. If it makes sense to argue, like McKillop, that J.S. Woodsworth’s philosophy is best summarized by Blewett, the same may be true of Smith and other Christians in the social gospel movement who did not take reason and secularism to the logical extreme of deism or atheism: “And the truth of the world, the truth both of ourselves and of the world, is God; God and that ‘far-off divine event’ which is the purpose of God, are the meaning of the world. And this means that that heavenly citizenship must first be fulfilled upon the earth, in the life in which our duties are those of the good neighbour, the honest citizen, the devoted churchman” (Blewett as quoted in McKillop, 2001: 223).

48 Michiel Horn analyzed this case in Academic Freedom in Canada: a History. Smith sued Wesley College for $30,000 but lost (Horn, 1999: 82). No surviving document indicates that there was a discussion of Smith’s Christian beliefs. Smith and his examiners debated bureaucratic procedures: the exact nature of his contract, how much power was assigned to particular offices, who should report to whom, etc. Smith often had private and public conflicts over administrative matters with the president of Wesley College. There is thus the question, which remains unresolved today: Does academic freedom cover instances in which an administrator publicly criticizes another administrator? 22 Having examined the archival information at Wesley College, I agree with Horn that it is unlikely Smith was fired because of his religious beliefs. The complaints by members of Grace Church may have been a pretext to dismiss a difficult colleague. Perhaps the referees who recommended Smith for Wesley College were too optimistic that he had acquired more tact. 23

49 In the 1920s, university and college presidents had more power than is the case today. Members of a governing board might have had the final authority in theory but they generally delegated decisions to the president (Millett, 1968: 2-3). Especially at smaller institutions that operated in a more informal manner, the organization of higher education combined bureaucratic authority and traditional authority (Baldridge et al., 1977). To some extent presidents made decisions on a personal and arbitrary basis, although they were restrained by their sense of the institution’s traditions. The president of Wesley was also influenced by his perception of the policies of the Methodist Church as well as the wishes of the wealthier board members. Smith had accepted the appointment at Wesley by telegram on 8 April 1921 and then wrote on 27 April saying that he was also uncertain about the exact title of his position, did not know his initial salary or annual increases, and wondered what the duties of a vice- principal (or vice-president) were. Smith mistakenly thought he could make important administrative decisions without the president’s prior approval. But Wesley College was financially insecure and some faculty and board members were uncertain about Riddell’s administrative ability (Friesen, 1985). When Smith had to defend his actions before the president and board he could credibly argue that his employer was the Methodist Church rather than Wesley College (Sparling, n.d.). In such a climate there were legitimate reasons for misunderstandings between administrators.

50 The dismissal, which came after only one year of his teaching at Wesley College, ended Smith’s academic career. Lacking even a master’s degree and having lost a court case that was publicized in the media, there was no future in higher education. It was a crucial time in Smith’s career. He was nearing the age of 50 and finally affiliated with an institution sustaining his interest in sociology, although it was a marginal institution in the North American university system. a Study in Canadian immigration could have been the start of a significant career in sociology. Instead, it is the highlight.

BUILDING THE NATION

51 In 1922 Smith published Building the nation, a second book targeted at general readers, which he had begun before leaving Toronto. The volume appeared in a graded series of books on immigration published by the Canadian Council of the Missionary Education Movement. Smith was responsible for the volume intended for adults. The editors of the series stated that the opinions expressed in the book were those of the author rather than the Missionary Society and that the book was “intended to provoke discussion rather than present final answers” (Smith, 1922: xv). For Smith’s biographer, this is the more compelling book because the topic allowed the author to elaborate on his personal opinions about the social role of religion. For example, the theme of self-sacrifice on behalf of the nation and the next generation is more fully developed. No dispassionate sociologist would end a book with a statement like this:

52 The dominant discourse in Building the nation is assimilation (or Anglo- conformity), although Smith’s respect for other religions is consistent with policies that later came to be called multiculturalism. Smith rejected amalgamation as impractical in the immediate present because it was too time-consuming. “This task is assimilation, which means Canadianization, not amalgamation. The latter must be left to future operations of nature. . . . But Canadianization is the glorious though difficult task of blending the diverse elements of the various peoples of our Dominion into the unity of a national life” (ibid., 170). Both Smith and Bland were more critical of their own people and institutions than of foreigners. In The new Christianity Bland offered some praise to Roman Catholics. Bland was familiar with Catholicism and could thus specify the lessons Protestants might learn from Catholics. Bland was also explicitly promoting the blending of Christian denominations because he thought the era of Protestant domination had passed. As far as I can tell, Smith lacked close contacts in ethnic minority communities. For instance, in his books he turns to other sources for ethno-graphic detail about newcomers’ experiences. Readers certainly learn about the work ethic of new citizens from Eastern Europe and Asia in Building the nation; however, the book teaches tolerance instead of an appreciation of foreign cultures. The latter required a level of cultural knowledge that Smith lacked. A full appreciation of Otherness was never his goal.

53 Smith agreed with official Canadian policy that it was essential to attract more farmers to Canada, especially to the western provinces. When Britain had to import food, the ideal adoptive citizens who would farm in Canada were not likely to be British. The option, “practical friendliness” (ibid., 163), was the acceptance of ethnic diversity and helping immigrants assimilate into a nation dominated by people of British ancestry. For Smith, assimilation had to be the work of both church and state, but religion was the ultimate source of values uniting the nation: righteousness, peace, and goodwill. Canada as a bi-ethnic nation, French and English, was not one of Smith’s preoccupations. For Smith, the main agent of Canadianization was not the clergy but primary school teachers. It was the role of the church to inspire more young people to make the sacrifices required by teaching, medical practice, and serving as social workers in minority communities. “The truest memorial to the sleeping victors of the struggle [of World War I] is a nation homogeneous in character, united in purpose, incessantly solicitous in its care of the living and exquisitely tender in its memory of the dead” (ibid., 178).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 154 One of the most inspiring themes in Building the nation is Smith’s explanation of why Chinese and other Asian immigrants were not assimilating. He did think, however, that a temporary restriction on Asian immigrants was unavoidable because of the confusion among the Canadian population about how to deal with them. He noted that the head tax on the Chinese paid the advertising bills for immigrants from all countries (ibid., 167-68, 306). Smith pointed to white racism as the cause of the problem. To put this in perspective, Building the nation was published one year before the Canadian government passed the Chinese Immigration Act, which excluded almost all Chinese people from moving to Canada and did nothing to address the unequal civil rights of those then living in the country (Li, 1998). Smith did not see Chinatowns as “dreary” places of “peculiar customs,” “heathen worship,” and “outlandish fiddles,” like one of the authorities quoted by Woodsworth (1972 [1909]: 144-52).

CONCLUSION: A TAINT OF RADICALISM

55 W.G. Smith’s preference to avoid the limelight has had the unfortunate consequence that, even though he was associated with a book as significant as The new Christianity, no historian has published an academic study of his career because of the paucity of autobiographical information. The result is that this article resembles an incomplete and imperfectly assembled collection of still photographs. We have precise information about brief moments in Smith’s career, but it is impossible to understand the movement outside the camera’s range. For example, Smith assigned essay topics on “doctrines of sensation” and “theories of association” (Anon., 1918) in a fourth-year course in 1918 at the University of Toronto, but it is impossible to say what he actually knew about psychology. The evidence that leads me to think he was a moderate within the social gospel movement includes the statement that he disagreed in some fundamental ways with Salem Bland, the mediating role he played in revising the 1918 declaration of the Methodist Church on industrial organization, the diplomatic assessment of the Rev. Billy Sunday, the unwillingness to state a clear opinion on the Winnipeg General Strike, the course outline that required students to read a book on vocational psychology, and his refusal in Building the nation to associate the Methodist Church with a specific socio-economic policy. 24 Rev. Neal commented that Smith had a taint of radicalism, yet Smith’s “square deal” is an inherently ambiguous term. While it might be interpreted as a reference to socialism, it can also be understood as tempering the social inequality inherent in any capitalist economy. Smith continued to refer to divine love, the moving grace of God, the inspiring hand of the prophets, and personal salvation.

56 He was angry about injustice; he had solutions for improving the immigration process that were consistent with those of the Methodist Church (Smith, 1922: 154-97); he knew at least the basic American sociological literature on race and ethnicity, and had read more widely in social psychology. Returning to Newfoundland to teach sociology at Memorial University College after his dismissal at Wesley College would not have been an option because the discipline was never part of the college’s curriculum (MacLeod, 1990). The first sociology course was offered at Memorial University of Newfoundland only in the mid-1950s, a date that is typical for many Canadian universities. One consequence of the social gospel for sociology was that when Protestant ministers and divinity students in the first quarter of the twentieth century associated sociology with social reform, they became less receptive to the scientific sociology popularized by the most influential department of sociology in North America, at the University of Chicago. If Smith had followed that development of a scientific thrust in Canadian sociology, he might have moved to Montreal because McGill had the first sociology department in Canada and was strongly influenced by Chicago. Unfortunately, his two books appeared near the end of an era, the pre-professional era in Canadian sociology.

57 After a period as a supply minister and conducting regular services at the Unitarian Church of Winnipeg in 1927-28 (Ransom, 1943), W.G. Smith concluded his career as a public servant. He served as the Director of Child Welfare in the Department of Health and Public Welfare for the province of Manitoba, and as Director of the Welfare Supervision Board in Winnipeg. 25This was a logical step for a Methodist minister, given the Protestant churches’ activist role in pressing for an expanded sphere of state activity (Christie and Gauvreau, 1996). In 1930 he published an article in Social Welfare in which he is identified as the Director of the Manitoba School of Social Science. This is an obscure institution that, according to Smith, was launched in October 1929 under the auspices of the Manitoba Department of Education and the Department of Health and Public Welfare. The school had no government grant and no university status, although the University of Manitoba provided space for the lectures and instructors were paid small honoraria. The aim of the school was to further the education of social workers, many of whom were university graduates who already held jobs in the social services. The projected two-year curriculum included lectures on sociology (Smith, 1930b). If we picture Smith as a tragic figure and imagine that the Manitoba School of Social Science is the sad end to a career that once looked so promising, we might be applying the standards of modern academic careers. Given Smith’s social activism, maybe some combination of employment as a civil servant and minister was the more satisfying option.

58 Rev. Smith died on 8 September 1943 in Calgary (where he had moved to be with family members) and was buried in Queen’s Park Cemetery. He was apparently a life-long sufferer from rheumatism, but how this might have affected his career is not known. Rheumatism can cause irritability. Smith seems to have been a person who was intent on complicating his life. That may be one reason why he chose to study psychology. The surviving documents suggest that he had a contradictory character — modest but opinionated. “This book has many defects” is the opening sentence in the preface to a Study in Canadian immigration (Smith, 1920c: 3). But he appears to have continually experienced problems collaborating with people. “Charming though [Smith] could be in his intercourse with his friends, he simply could not work with other people” (Dr. G.B. King of Wesley College, as quoted in Bedford, 1976: 177). His failure to develop into a professional sociologist was not due solely to an unfavourable institutional climate. In person, he may have been abrupt and intolerant of sham and old ideas, but this personality trait does not surface in his writings.

59 Contemporary readers are likely to be disappointed that the theoretical dimensions of Smith’s topic are left at such a rudimentary stage. Readers rarely get to hear immigrants speak for themselves or hear what they think about native-born Canadians. But to his credit he did not tell newcomers what to think or how to behave. Was that because he himself was an immigrant? Oddly, he never told readers of his books that he was born outside Canada. He might have acquired a better understanding of acculturation and assimilation if he had reflected in his writings on the experiences of moving to Toronto as a young adult. 26 The loss of W.G. Smith to Canada could be understood as the price Newfoundlanders paid for the slow progress higher education made in St. John’s, where the first degree-granting institution of higher education opened its doors 55 years after he entered the University of Toronto.

60 What lingers in the mind after reading W.G. Smith is the strength of his commitment to social justice. Let us give Rev. Smith the last word. Here, from Building the nation, is part of his critique of the Canadian treatment of Asian immigrants: