"The Devil's In The Details":

Benign Neglect and the Erosion of Heritage in St. John's, Newfoundland

C. A. SharpeUrban Geographer, Memorial University

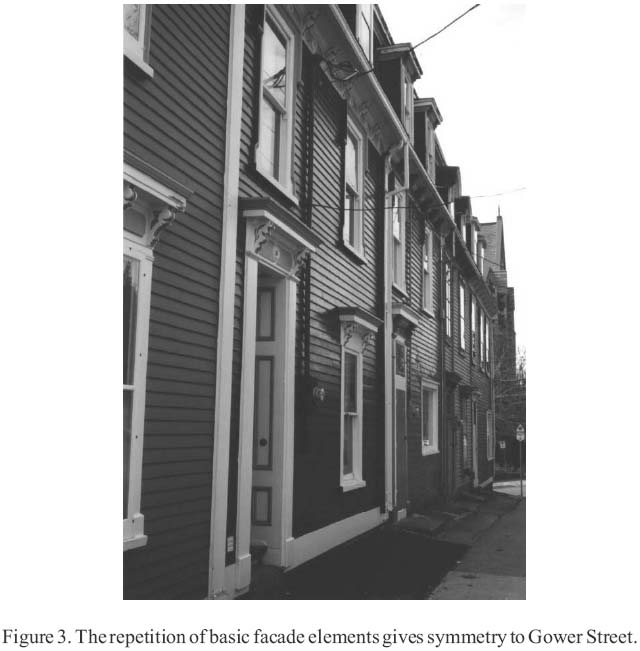

1 SOON AFTER ITS DESIGNATION in 1977, the St. John's Heritage Conservation Area [HCA]1 was characterized by Canada's leading writer on heritage issues as the most successful area conservation scheme yet undertaken in the country (Tunbridge, 1981:118).One significant characteristic was that it incorporated a large part of the central commercial, institutional and residential core of a metropolitan area (Riopelle, 1978). Furthermore, the investment of public and philanthropic funds successfully elicited a considerable amount of private investment, thus satisfying one of the scheme's original goals. A principal cause of this investment multiplier — a 'halo effect' — was that the St. John's Heritage Foundation [SJHF] purchased, restored and resold 28 houses between 1978 and 1981 (Figure 1). There also seemed to be a strong municipal commitment to heritage conservation, recognizing that, as expressed in public meetings, "the residents of St. John's appreciate their city mainly for what it is and has been, rather than for what it could potentially be" (City of St. John's, 1984: Section II-6).2 The 1990 Municipal Plan, in a section subsequently weakened, said that "one of the City's main assets, one that contributes so much to the enjoyment of its residents and visitors, is its built heritage of fine old buildings and streetscapes. It is important to preserve and enhance these features as a part of the development of the City" (City of St. John's, 1990: Section II-10).3 As recently as 1999 St. John's was identified at the Construct Canada Exhibition as one of Canada's outstanding achievements in building and construction. Yet a recent book by three of the most prominent names in the heritage field stated that "St. John's can claim the dubious distinction of possessing both the largest and the most unsuccessful conservation area in Canada" (Graham et al., 2000).

Figure 1. Downtown St. John’s and the ‘Heritage Houses’ restored by the SJHF.

Display large image of Figure 1

2 How did this happen? Is it simply proof that initial good intentions, followed by the valiant efforts of a small group trying to emulate Horatio at the bridge, cannot ensure the long-term protection of something about which the majority is indifferent, or worse? In retrospect, it is clear that the struggle to gain the political and economic support necessary to create the HCA, difficult as that may have been, was the easy part of the job. The much harder task of maintaining an effective, long-term political commitment to support and defend the principles of heritage conservation has proven impossible to accomplish for two principal reasons: a poorly defined purpose for the HCA and an overly ambitious expansion of its size.

3 By definition a case study is reductionist. However, it can be of more general interest and its lessons applied elsewhere if it can be related in some way to a broader context, as this one can. Efforts to preserve the built heritage of downtown St. John's in the nearly 31-year-old HCA are embedded in Canadian and international contexts, which need to be reviewed briefly to provide the necessary context for the local story.

HERITAGE AND HERITAGE CONSERVATION AREAS

4 The goals of a heritage area can be diverse. They may include maintaining the aesthetic qualities of a delimited piece of townscape, conserving resources by restoring existing buildings, protecting cultural memory, maintaining architectural, functional and environmental diversity, and facilitating economic regeneration. They may also include stabilizing population levels, promoting local, regional or national identity, helping citizens cope with rapid change by retaining familiar landscapes, maintaining residential land uses, and enhancing property values.

5 Before considering which of these are applicable to St.John's, there is an obvious question to answer: What is meant by the commonplace word 'heritage'? Those with any familiarity with the literature will know that this is a contested word, which perhaps cannot be defined at all, since "overuse has reduced the term to cant" (Lowenthal, 1996: 94). This may be too extreme a position. One simple definition is, "something we have possession of after the death of its original owners, and which we are now free to use as we choose" (Walsh, 1992: 24). Another is, "that which a past generation has preserved and handed on to the present and which a significant group of the population wishes to hand on to the future" (Hewison, 1989: 15). Most of us would feel reasonably comfortable with either definition, though Hewison's implicit assumption of purposeful preservation by our predecessors may be unwarranted. But they both beg many questions. Given that "heritage is a matter of perception and a quagmire of dissonances" (Tunbridge, 2001: 359), who should be responsible for selecting those relics of the past which are to survive the current generation, and on what basis? Whose responsibility is it to pay the costs of preservation?

6 In spite of its indisputable role as the steward of national heritage, the federal government provides no help in answering these questions. In typical Canadian fashion, the Department of Canadian Heritage website evades the issue by saying that "heritage means many things to many Canadians" (Department of Canadian Heritage, 2004). The built environment is one of these "things," along with other tangible and intangible "things." The Department of Canadian Heritage Act (C-17.3) is one of 30 pieces of legislation identified on the department's website as "related to Canadian heritage," which suggests that there is no official definition of heritage, and that the overall responsibility for its protection has not been defined.

7 Most people are unconcerned with the intricate debate over meaning, and support the creation of heritage areas because they maintain a familiar environment. While it may be irrational, we try to preserve the familiar because "to live in the same surroundings that one recalls from earliest memories is a satisfaction denied to most of us" (Lynch,1972:61). There is (still) a widespread perception that things were better in the past, and that preservation of its artifacts can contribute something desirable to a contemporary world which is perceived to be somehow inferior. Many people think that the preservation of heritage items is "moral in itself," and that "environments rich in such features are more pleasant places in which to live" (Lynch, 1972: 30). The fact that "heritage" and "quaint" have become synonymous in the contemporary real estate market does not change the essential truth of this comment, despite the wisdom of the observation that "the past isn't quaint when you're in it" (Atwood, 1989: 386).

8 Decisions to preserve urban built heritage are commonly based on the assumption that it plays a significant role in the everyday lives of ordinary people. But there has been very little investigation of public attitudes towards heritage conservation, and the assumption that the general public supports such projects on the basis of a considered heritage conservation rationale remains just that — an assumption. It has been argued that any attempt to justify conservation with reference to the supposed role which buildings play in people's lives is nothing more than an ex post facto rationalization of an elitist activity (Hubbard, 1993: 362). It may be that the so-called expert knowledge which drives the identification, preservation, interpretation and delivery of the heritage product to the general public is incorrect in its assumption that the public derives social, psychological and aesthetic benefits from it. If this is true, we certainly don't know why (Parkes and Thrift, 1980: 64), although we do know that public support for heritage conservation is idiosyncratic, fickle and often incidental (G. Wall, 2002). "Many symbolic and historic locations in a city are rarely visited by its inhabitants... but a threat to destroy them will evoke a strong reaction ... [because] the survival of these [often] unvisited, hearsay settings conveys a sense of security and continuity" (Lynch, 1972: 40). A study of the Old Strathcona neighbourhood in Edmonton, Alberta (Heritage Canada's first "Main Street" project), concludes that "outside the middle class, people have little attachment to historic architecture or objects" (K. Wall, 2002: 36). This confirms British evidence that official heritage is defined, interpreted and presented primarily by middle-class experts and consumed largely by their peers (Light and Prentice, 1994).

9 Arguments in favour of preserving urban built heritage often ignore the fact that most old buildings have survived as much by accident as by design. Thus the heritage we create by making contemporary economic, cultural, or political use of the past (Ashworth, 1997) is based on a set of decisions made with respect to a collection of fortuitous survivals. We may end up saving buildings that might not have been considered worthy of preservation by those who made them. It is certainly true, in most cases, that our forebears did not erect buildings or create artifacts with the expectation that they would survive to impress posterity. We must also remember that our inheritance includes not just things that we like, but some that we would prefer not to have inherited. Far from being benign creations, heritage landscapes can be viewed and valued differently by members of any one society, thus creating dissonance (Tunbridge and Ashworth, 1996). Dissonance can also arise from the way in which heritage is identified, since this is very much a matter of power: "Populism not withstanding, heritage normally goes with privilege: elites own it,control access to it and ordain its public image" (Lowenthal, 1996: 90). And given the absence of any history of de-designation, decisions once made become permanent (Galbraith, 1980: 57).

10 Heritage areas reflect the notion that an appropriate spatial context is critical for the proper understanding of the significance of individual buildings, and that this context is always at risk. This is a relatively recent development. At one time, the emphasis in heritage conservation was exclusively on the monumental and the unique, and the importance of the ordinary vernacular buildings which comprise our "scattered past" and provide the compatible supportive environment for individually important buildings was often overlooked (Fitch, 1990: 24). Heritage Canada embraced the concept of heritage conservation areas in 1974 (Miller, 1975), recognizing that the character of an area may be adversely affected by the alteration or removal of buildings which are not, themselves, of architectural or historic significance. The stimulus came largely from development controversies related to the Byward Market in Ottawa (Tunbridge, 1987). The new concept proposed the designation and protection of "integrated environments compatible in scale and quality ... whose character and size combine to provide an atmosphere ... of the past" (Phillips, 1975: 16).

11 The designation of heritage landscapes poses problems much more complex and contentious than the relatively simple designation of individual buildings. Administrative and control difficulties are guaranteed by the fact that any substantial inner city area will inevitably incorporate both privately-and publicly-owned properties. Long-term consequences are too often ill-considered in advance. Designation inevitably requires that development proposals have to be considered under rules different from those which apply elsewhere. More dissonance arises from the conflict between the necessity of townscape evolution in the face of new economic conditions and market forces, and the desire to reduce or eliminate change. The "creative destruction" of some portions of the inherited built environment, and the consequent wastage of investments made by past societies, may be an inevitable consequence of the way in which this conflict is resolved(Mitchelletal., 2001).

12 Designation of a heritage district creates planning consequences which are rarely considered. The prohibition of certain or all types of new development inside the area inevitably deflects development pressure to other parts of the city (Baer, 1995). Conferring historic status on an area implies a permanent commitment, on behalf of the taxpayers, to the costs of maintenance (Ashworth and Tunbridge, 1990: 16). It also requires constant monitoring by the municipality to prevent the small-scale changes in architectural detail and design which can so easily erode the essential character of an area (Larkham, 1999: 265).

13 The St. John's HCA incorporates a significant retail component as well as residential neighbourhoods. The core of the historic retail center along Water Street, designated a Historic District by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (HSMBC) in 1987, is inside the boundary. The major commercial showpiece of the HCA lies between Water Street and Harbour Drive. The Murray Premises, a National Historic Site, is a complex of ten buildings dating from ca. 1848, and is the only significant surviving mercantile structure pre-dating the Great Fire of 1892. The absence of any recent large-scale development proposals in the retail core has spared St. John's the kind of acrimonious debate over how best to preserve historic streetscapes that has troubled other cities like Niagara-on-the-Lake. There has been some encroachment into viewplanes and some very inappropriate new buildings, the most egregious example of which is Atlantic Place. However in St. John's this has not occurred as part of an integrated, large-scale operation.

14 Nor has the area been transformed into the commonplace image of a "convivial city" catering to the "cappuccino lifestyle" of baby-boom professionals (Ley, 1996;Tunbridge,2001;G.Wall,2002).St.John's enjoys the luxury of a readily accessible waterfront and a dramatically picturesque harbour. The Murray Premises overlook this scene, which, in another context, would undoubtedly have been seen long ago as the ideal anchor for a "festival marketplace" (Tunbridge, 2001). But in spite of this raw material, there has been no concerted effort in St.John's to produce an urban consumer space in which the symbolic capital of built heritage is commodified and appropriated by commercial interests.4 This is not to say that the HCA has not been affected at all by the "'three D's' (development, dissonance and derivates) of the 'heritage maelstrom'" (Tunbridge, 2000). There have been development pressures, but not in the form of intensive, large-scale proposals intended to exploit a revalorized streetscape. There has been just sufficient development pressure to ensure that the heritage lobby has not been able to disband. Dissonance, the second 'D', has been absent because there is no contested heritage in St.John's. Local history does not incorporate a period of repression and dispossession of ethnic or minority socia lgroups. But there does continue to be "derivative competition for the locational primacy initiated by heritage" (Tunbridge, 2000: 269). This is the third 'D' which, in the absence of rigorous design controls, can easily lead to discordant streetscape elements. It also provides a basis for Tunbridge's contention, based on his analysis of merchants' decisions to locate in the Byward Market Heritage Conservation District, that while commercial operators and investors cannot help being influenced by broad heritage factors, they have little appreciation of architectural or historic nuances, and little or no tolerance for the restrictions that heritage area designation places on their own specific premises. To them, the Market is "the place to be," but not because of its heritage qualities, and many of them chafe under the resulting planning and use restrictions (Tunbridge, 2000).

THE AIM OF HERITAGE CONSERVATION IN ST.JOHN'S

15 There are many interesting and unexplored issues in the commercial sectors of the St. John's HCA, but this paper confines itself to an investigation of events within and policies affecting the residential sector. This is an area of relatively homogenous housing, devoid of any particular heritage focal points. The 'heritage factor' derives from the general historical ambience which is simply a visual function of the traditional streetscape.

16 As we have seen, definitions of and attitudes toward heritage and heritage conservation are highly variable. To be successful, a programme of conservation and/or preservation of the historic residential built environment requires a clear statement of purpose, a committed municipal administration, and a supportive populace. If the questions "what are we preserving? for whom? and why?" cannot be satisfactorily answered, then the project is doomed to failure. The members of the Newfoundland Historic Trust (NHT) who lobbied for the creation of the HCA in the early 1970s had a clear idea of their collective purpose. It was to preserve all forms of architecture that reflected the culture and heritage of Newfoundland, to enhance the general downtown environment of St. John's by preserving the street pattern and its streetscapes, and to adaptively re-use historic buildings in the downtown area for low-income housing (Minutes of the annual meeting of the NHT, 1974). This clarity of purpose was not carried over into the legislation. The Heritage Bylaw (City of St. John's, 1977) simply designated the boundaries of the HCA, established a Heritage Advisory Committee and prohibited the demolition or alteration of any building inside the Area without Council's consent — a prohibition which one might have assumed would apply everywhere — but did not specify the purpose or goal of the Area. The absence of design controls in the bylaw, or in the Municipal Plan which eventually subsumed it, and the fragility of the coalition which originally championed the creation of the HCA, created the situation described in this paper.

17 The original plan was to create a small, carefully delineated HCA containing a representative collection of residential and commercial structures "large enough to immerse a passerby in an atmosphere of the past, but at the same time small enough to be manageable and to facilitate implementation" (Sheppard et al., 1976: 19). Since the newer, post-war sections of the city, planned to modern standards with wide streets and generous setbacks, could be found anywhere in Canada, it was not necessary to consider designating them as heritage areas.5 The defining characteristic of the inner city was its human, rather than automobile-oriented, scale, and the purpose of heritage conservation was to preserve this character (Warren and Hawes et al., 1981). No isolated area or particular group of buildings stood out as the obvious candidates for conservation. The character which was the object of interest was produced by "the grouping of buildings and the layout of the town, not just the buildings themselves, which produce the flavour and historic character ... (and) the pleasing proportions which by their presence lend to St. John's a sense of the sequence of time" (Sheppard et al., 1976: 5). Most of the buildings in the residential areas were simple, ordinary row houses built after the fire of 1892. "Many were of sound construction and fine detail, but ... individually of little historic or architectural value... [but] the combination of all these ordinary buildings produces the rich and often-commented upon character of St. John's. Every time one of these buildings is destroyed, or has an exterior change, a bit of this character is lost" (Sheppard et al., 1976: 42). The defining characteristic of the HCA, then, was the visual integrity of its streetscapes in which the whole was greater than the sum of its parts. Defenders of the HCA have continued to make the same argument ever since, unfortunately with less to defend each time (Minutes, St. John's Municipal Council, 11 March 1991).

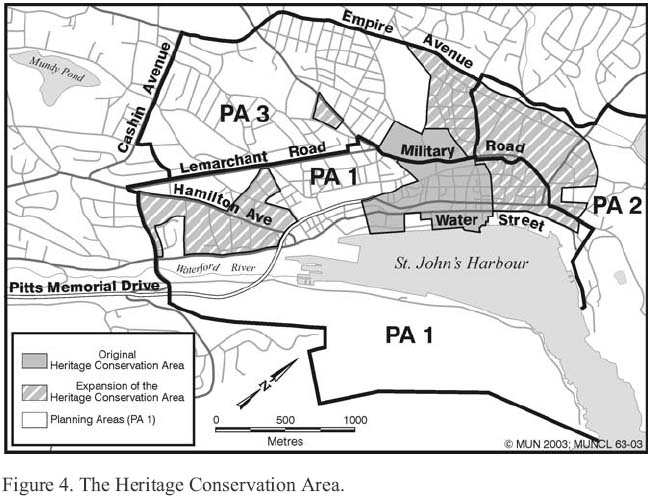

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ST.JOHN'S STREETSCAPE

18 To be effective, a conservation policy intended to protect the existing character of a defined area requires the prevention of an uncontrolled mixing of 'heritage' and 'modernized' buildings stripped of their original decoration. The maintenance of streetscape integrity was the motivation for the SJHF to propose a programme under which it would have upgraded or restored the facades of 60 of the 149 houses on Gower, Bond and Prescott streets (Webber, 1979). This programme was stillborn, but demonstrated that the original proponents of the HCA concept believed it was the overall character of the streetscape which had to be preserved. To do so required preservation of the often small details which, in the aggregate, comprised the essence of what was unique.

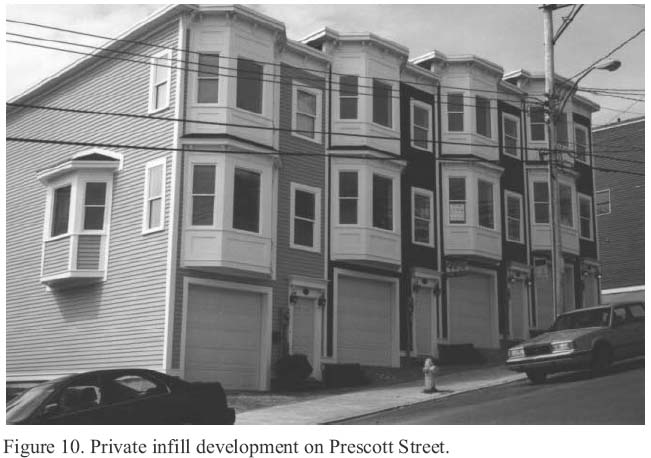

19 The feasibility study argued that the distinctive character of the traditional St. John's streetscape is defined by three elements: cladding, fenestration and colour (Figure 2).

20 Cladding. The traditional cladding on ordinary residential properties is narrow (4 inches exposed) wooden clapboard. The strong texture which it produces is visibly disrupted by any incongruent changes. The cladding is complemented by wide coinboards and window trim, the former providing a strong vertical separation between units, and the latter accentuating the windows.

21 Windows. The original windows were remarkably consistent in style and size, measuring approximately three feet wide by six feet high. There petition of the rectangular shape, and the wide trim, produces a strong vertical component in the streetscape which is severely disrupted by the introduction of horizontal windows.

22 Colours. Most houses were painted in a limited range of deep colours such as dark red and green. The light pastel colours of most 1970s vintage vinyl and aluminum siding were highly undesirable (Sheppard et al., 1976).

Figure 2. Gower Street houses restored by the SJHF.

Display large image of Figure 2

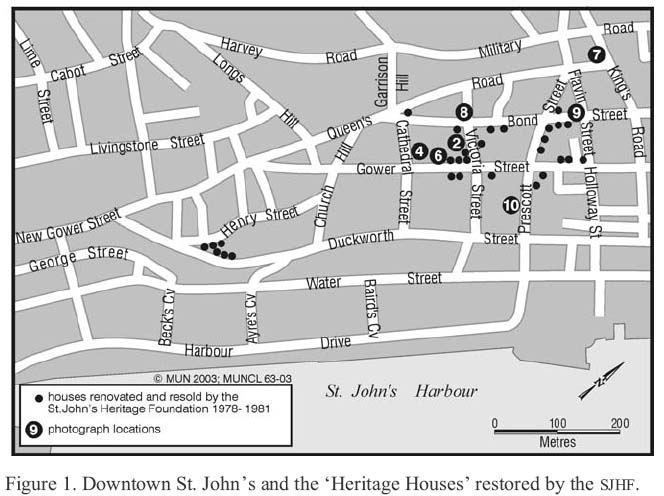

23 The character of the traditional streetscape is thus defined by there petition of a few basic structural and decorative elements: narrow clapboard, vertical windows, wide trim, eave and window brackets and, although the feasibility study did not make a point of it, mansard roofs on some streets (Figure3). One of the major short-comings in the City's heritage legislation is the failure to describe these traits, and embed the requirement that they be preserved in the development control legislation.The 'heritage'streetscapes of St.John's were thus left vulnerable to incompatible alterations. This is not an uncommon situation. In the Old Strathcona HCA in Edmonton, no authentic details requiring preservation were specified. The inevitable result was that "generic old-fashioned" features providing only "hints and references" to the past rapidly appeared on both old and new buildings (K.Wall,2002: 32). Even Ottawa, with its 11 heritage districts, has strangely limited municipal oversight, since only those changes requiring a construction permit are monitored, leaving roofing and siding materials uncontrolled (Tunbridge, 2000: 281).

Figure 3. The repetition of basic façade elements gives symmetry to Gower Street.

THE EXPANSION OF THE HERITAGE AREA

24 The absence of strong design controls is one significant problem. A second, which has increased the difficulty of protecting the urban heritage of St. John's, is an over-expansion of the size of the HCA. The original HCA comprised 45 hectares (111 acres). By 1990 it had been expanded "to include portions of the East and West End residential neighbourhoods that contain significant groupings of architecturally interesting older buildings that help to form'heritage streetscapes'" (City of St. John's, 1989: 8) and now covered 167 hectares (413 acres). Freeing the heritage area concept from its erstwhile strictly downtown location, the 1990 expansion represented a major departure from the original concept, and the nearly four-fold increase in the area increased the number of properties within the HCA from approximately 600 to nearly 2,100 (Figure 4). The expansion was cleverly effected by proposing extensions of the original area in three separate local Planning Area Development Schemes. This strategy of piecemeal expansion, while effective in allowing the planners to accomplish what they intended, precluded a public debate on the fundamental question of whether the size of the HCA should be increased. The pragmatic benefits of this strategy are obvious, especially in a city where public support for the very idea of heritage conservation is fickle and muted.However, one cannot help but wonder whether a precious opportunity to solicit public support for the planners' strategy was sacrificed.

Figure 4. The Heritage Conservation Area.

Display large image of Figure 4

25 The dramatic expansion of the HCA, despite its good intentions, may have contributed to a weakening of the heritage conservation movement. The City Planner ruefully admitted that expanding the boundaries successfully identified all the areas with "good heritage potential," but created a supply which exceeded the demand, and may therefore have been "a poor move in trying to achieve specific targets in heritage improvement" (de Jong, 1991). The problem could be remedied, he said, if Council either reduced the heritage area to its original size, or introduced a two-tier system in which there would be a heritage core governed by stringent regulations, and a larger area subject to more limited objectives and fewer regulations.6 In 1993 the Planning Office carried out a pilot project to determine the feasibility of establishing Heritage Design Control Areas within the inner city, but this is now nothing more than an historical curiosity. An administrative reorganization in 1995 led to the amalgamation of the municipal planning and engineering departments, a reduction in the the planning staff, and their subordination to the City Engineer, who became the head of the new Department of Engineering and Planning. This effectively ended any proactive initiatives of this kind.7

26 As early as 1980, the City Planner warned the Council that development control in the HCA was inadequate, and that in the absence of detailed design controls the future of the city's heritage quality was in jeopardy. He said that neither the members of Council, nor the public they represented, had a clear idea of what the HCA was really supposed to do, or how to go about doing it. An ineffective heritage conservation policy was the inevitable result. He believed the only way to resolve Council's ambivalence in its disposition of heritage issues was to decide whether the Area had any value for the city. If it did not, it should be eliminated. If it did, clear guidelines to control renovations and new development would have to be developed, and then enforced (de Jong, 1980). Unfortunately, this decision has never been made.

THE VINYL SIDING DEBATE

27 It is not too much of an exaggeration to suggest that the crippling of effective heritage conservation in Canada's eastern most metropolitan area was brought about by the introduction of vinyl siding. There were certainly other underlying causes, but the question of whether non-traditional vinyl and aluminum siding could be used in the HCA was the lightning rod for the disaffected. A 1991 decision by the City to surrender its control over the materials used in renovations and new construction effectively terminated the ability of the City to control the 'heritage look' in the HCA.

28 The Heritage Advisory Committee established by the 1977 Heritage Bylaw had the responsibility, inter alia, of considering "any application for exterior alterations in a Heritage Area." The Committee never felt it could control the choice of materials, and although the use of clapboard was encouraged, it did recommend that narrow (so-called "double 4" ) vinyl siding be permitted in some cases. It always recommended that applications which involved the use of wide (8 inch) siding or the insertion of non-traditional windows be rejected on the grounds of non-conformity with the context of the streetscape, and non-compliance with municipal regulations (O'Dea, 2004). This was consistent with best practices elsewhere in Atlantic Canada. In Charlottetown, Saint John and Fredericton, applications for the replacement of traditional wooden cladding by aluminum or vinyl siding on dwellings inside designated heritage areas were routinely rejected. Such precedents encouraged the City's heritage planner to argue that "there were reasonable grounds to restrict the use of non-wood siding in areas where such siding is not prevalent" (McMillan, 1990).

29 The substitutability of man-made cladding was only one issue. The vinyl siding then available in St. John's was not an acceptable substitute for clapboard. It was too wide, had a texture completely unlike wood, and was available only in a range of inappropriate pastel colours. High-quality, narrow-width vinyl siding which could come close to achieving the desired heritage effect was being produced, but was unavailable in Newfoundland. The province had traditionally been a dumping ground for low-quality vinyl which was visually inappropriate, did not provide the maintenance-free future promised by advertisers and so eagerly sought by homeowners, and cost as much as high-quality wooden cladding (de Jong, 1991).

30 The continuing controversy over what were appropriate changes to structures within the HCA led Council to adopt a design control policy in March 1991. Its purpose was to clarify the permissible limits on facade renovations, and the role of the Heritage Advisory Committee in considering applications for new buildings or repairs. The goal was to minimize future conflicts by reducing uncertainty. The new policy called for stringent controls on streets in selected areas, those "containing a relatively high proportion of buildings with traditional design features such as traditional cladding materials, location and proportion of openings, and roof forms [where] only materials and designs characteristic of the period up to 1914 or thereabouts, may be used in the repair, restoration or rehabilitation of the exterior of buildings" (City of St. John's, 1991).

31 This policy reflected more than a simple dislike by 'heritage supporters' of non-traditional cladding or modern windows among the 'heritage activists.' It reflected the concern that when they were substituted for the original clapboard or windows, the remaining trim and brackets were usually stripped off unless the owner paid a substantial premium to compensate for the extra time and effort required to work around, and thus preserve them. As a result, the typical outcome of a renovation project was a pastel-coloured plastic house, equipped with the dreaded horizontal sliding windows, and bereft of all its original detail.

32 The Council debate on the proposed policy was acrimonious. The then-deputy Mayor8 argued that "the choice of materials should be left to the individual" and characterized the proposed prohibition of non-traditional siding as "discriminatory, disgraceful, unfair, elitist and snobbish" (Minutes, St. John's Municipal Council, 11 March 1991). As previously noted, the Committee had never been dogmatic in its opposition to the use of non-traditional cladding. But a majority of the members of Council had always been resolutely opposed to any sort of controls, and negative recommendations from the Committee were routinely criticized and often rejected (EveningTelegram, 1991a, b). In part this reflected a personal antipathy towards the most well-known heritage advocates and their cause, and the Committee was often described by councillors as elitist and obstructionist. But the more significant factor is public attitudes towards the limitations on personal freedom which are inherent in any municipal regulations. The allegation made more than 15 years ago that "most downtown people want the heritage regulations changed... because they are fed up with the Committee dictating to them" (Gushue, 1988) has never been proven incorrect. And it is this attitude, or a pragmatic Council's perception of it, that is the most likely explanation for the Council's history of lukewarm support for heritage issues. Many, perhaps even most citizens, are vehemently opposed to any kind of design or materials control, even the minimal ones that St. John's has had. And it is this group from which the planning staff and members of Council hear most frequently on a routine basis. This is a reality of which people in the heritage community in St. John's and elsewhere are often either unaware, or choose to ignore (O'Brien, 2003). It is the reality which explains why the preamble to the heritage section of the Municipal Plan says only that "heritage buildings should retain their original features" (City of St. John's, 2003: III-27; emphasis added).

33 Recognizing the necessity of accommodating the obdurate opposition of some councillors to design controls, the Heritage Advisory Committee had agreed to a compromise whereby the prohibition against vinyl or aluminum siding would apply only to the sides of a building visible from a street, courtyard or public area. This politically astute but unpalatable concession weakened the new policy, but at least made its approval possible. However, its effectiveness was further reduced by the fact that it applied to 2,077 properties on 67streets. It is difficult to imagine how any municipality could maintain effective control over maintenance and renovations on so many properties.

34 The new policy did nothing to resolve the ongoing tensions between the Committee and Council, and after it had been in effect for only six months Council decided that a public hearing would be held on 24 September 1991 to solicit opinions on the question of whether vinyl siding should be permitted inside the HCA. The majority of those attending the meeting said they opposed the use of vinyl or aluminum siding in the heritage area, and that they wanted Council to stop ignoring the heritage guidelines (Jackson, 1991). The majority opinion was not necessarily representative of HCA residents, since many speakers did not live in the Area. Those that did tended to live on the more affluent streets in the eastern part of the Area. However, the City Planner argued that their opinion was very significant because they were the ones who had made heritage development a reality over the previous two decades. He also noted thatthe special qualities of genuine wood are probably an essential prerequisite for creating the 'heritage image.' Buyers shopping for a heritage home in the most popular areas of the downtown expect to find a genuine wood-clad house, and are willing to pay a premium to get one.... You can fake it only so far. There comes a time when genuine heritage become a 'vinyl illusion' which will not be saleable any longer, and which loses its constructive role as a catalyst for renovation and rehabilitation through private initiative and funds. (de Jong, 1991: 3)

THE REAL ISSUE

35 The hearing considered only the simple question of whether vinyl siding should be permitted and bypassed the real issue, which was the very nature of development control itself. The design control policies which Council had recently adopted did not permit any leeway in their interpretation. Council had long been accustomed to operating with a degree of both technical and political inconsistency which was now impossible. Stripped of all rhetoric, the issue was simply that in 1991 wooden clapboard was more expensive than vinyl siding. So the difference between vinyl and wood was more than just a difference in building materials. It divided the upper and lower sections of the 'siding market' and some councillors argued that a prohibition against vinyl siding would constitute discrimination against the poor.

36 In matters of heritage conservation, whose values should take precedence — those of the 'heritage elite' or those of the 'ordinary citizen'? The existence of widespread public support for the preservation of the historic environment is too often taken for granted. Studies have shown that people do care about their historic environment, valuing its meanings, beauty, diversity and familiarity (English Heritage, 2000; Pollara, 2000; Heritage Canada, 2001). However, while many people will say that they support heritage, their view of what heritage is, and what should be done to save it, may be quite different from that of heritage activists. Most people cannot tell the difference between real and false heritage facades and more importantly don't really care about the issue (K. Wall, 2002: 36). Furthermore, surveys, whether about heritage or anything else, rarely require respondents to think about the costs of their answers, or the possible trade-offs that might be necessary to accommodate their expressed wishes. "Questions asked in the abstract get abstract answers" (Simpson,2002),and people might well respond differently to a question which asked how much additional municipal tax they would be willing to pay in order to make more stringent heritage regulations possible. The historic environment is the outcome of a process in which each generation makes its own decision about what to do with the legacy it has inherited (English Heritage, 2000). Every past generation has been able to modify its environment to suit itself, and the current generation generally wants to be able to do the same thing.

37 The prevailing view of the early 1990�s Council was that private rights should take precedence over public ones. Several councillors argued that there should be no interference with the right of individuals to make renovations to their own property, using whatever materials and designs they wanted. Those who supported the imposition of design controls were in the minority, and could not prevent their colleagues disregarding the clearly expressed majority view at the public hearing. As a result, in 1994 the City was able to abandon its control over the type of material used on all houses in the HCA.

THE 1994 MUNICIPAL PLAN AMENDMENT AND THE LOSS OF DESIGN CONTROL

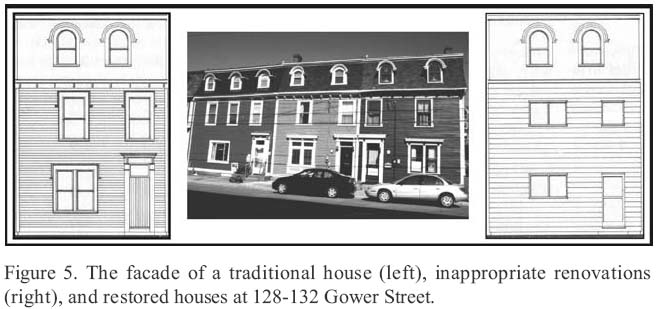

38 The 1984 Municipal Plan required that all buildings in the residential precincts of the HCA "shall conform with other buildings ... originally constructed prior to January 1, 1930, in terms of style, materials, architectural detail and architectural scale" (emphas is added). Council's 1991 design control policy required tha t"only materials and designs characteristic of the period up to 1914 or thereabouts be used for all repairs and rehabilitation of buildings in the Heritage Conservation Area." However, when the Plan underwent a statutory review in 1994 the City proposed that the language be amended to require only that new development "conform with existing buildings in terms of style, scale and height." This deprived the City of its authority to regulate the use of non-traditional materials on the grounds of aesthetic suitability, and thus to prevent inappropriate renovations (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The facade of a traditional house (left), inappropriate renovations (right), and restored houses at 128-132 Gower Street.

Display large image of Figure 5

39 At that time, provincial legislation required that any Plan amendments be subject to a public hearing presided over by a provincially appointed commissioner,9 whose report was submitted to the Minister of Municipal Affairs. The City assured the Commissioner that there was every intention of continuing to support heritage conservation, but that there was no need or justification for interfering with citizens'choice of building materials. The Commissioner accepted the City's position, and opined, "I am not sure the dropping of the word 'materials' is that significant ..." (Heywood, 1993: 29). The Plan was amended accordingly and, although it seems that the 1991 design control policy was never formally rescinded, it obviously became inapplicable.

40 The duties of the Heritage Advisory Committee were modified at the same time by the removal of the requirement that it consider "any application forexterior alterations in a Heritage Area." Its reduced mandate was now only to advise Council on the designation of, or changes to, heritage areas, the designation of heritage buildings, and on "any heritage issues ... which may be referred to it by Council" (City of St. John's, 1994: Section 4.2.2).

41 Was the Commissioner correct in his belief that the removal of this single word was an inconsequential change? Or has the inability of Council to regulate building activity in the interest of preserving the 'heritage look' led to a degradation of the architectural uniformity which has always been considered one of the hallmarks of heritage streetscapes? And if it has, does it matter?

THE EROSION OF HERITAGE

42 Conservatives believe that an unrestricted free market will do what is best for the majority. The folly of relying on such a belief is everywhere evident. Private developers will, by and large, do what is easiest, least risky and most profitable. With the exception of those operating in the bespoke market, this means catering to the lowest common denominator. It means creating an illusion of heritage that the un sophisticated majority of buyers will accept as real. The power of advertising, and the willingness of many consumers to accept at face value what they are told, makes it all too easy to manufacture and sell the fake heritage produced in a development environment where the derivative value of a heritage resource is more highly valued than the presence of the genuine heritage itself.

43 Since 1994 the toothless heritage regulations have permitted a steady erosion of the heritage characteristics of the HCA in two ways. The first is the creeping vinylization of the downtown streetscapes. A 1983 survey showed that 10.6 percent of the houses in the HCA had been reclad in vinyl or aluminum. A re-survey of the same streets in 2003 showed that the percentage had risen to 21.3 percent. On the streets which were added to the HCA between 1987 to 1989, the vinylization was even more dramatic, increasing from 16.8 to 37.9 percent. Inside the current boundaries of the HCA a total of 32 percent of the houses have non-traditional cladding and 44.3 percent have both non-traditional cladding and windows10 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The discordant effect of inappropriate alterations on Gower Street.

Display large image of Figure 6

44 The insidious vinyl invasion has affected prominent landmarks as well as ordinary dwellings. In 1979 the Seventh Day Adventist congregation which occupied a former Congregational Church on Queen's Road sold their building to a developer who wanted to convert it to a hotel. It was subsequently converted to condominium apartments. Ironically, the only way to accomplish this change was to apply for heritage building designation. The Council designates such buildings on the basis of their historical or architectural importance, in order to protect their external appearance (City of St. John's, 1989: 8). The City offers no financial benefits, either grants or tax relief, to the owners of designated heritage buildings, but there is a provision allowing them to be used as bed and breakfast houses, or condominium units, in order to generate the additional income necessary to maintain them.

45 The now-converted building was sold again in 1994, and the new owner applied for permission to reclad the building with vinyl siding. The heritage building designation precluded this, as did the 1991 Design Control Policy, which required that all buildings in 'Selected Areas' (which included Queen's Road) must be finished with traditional cladding, defined as "wood, brick, stone or stucco, in a manner generally used on residential buildings erected prior to 1914." Furthermore, City regulations required that any proposed exterior alterations to designated heritage buildings had to be "carefully monitored by Council for authenticity, as opposed to the primarily contextual approach which occurs with any other building in a heritage area" (McMillan, 1990).

46 Council initially accepted the Heritage Advisory Committee's recommendation that the request be denied (Minutes, St. John's Municipal Council, 25 July 1994). Undaunted, the owner re-applied, pointing out that the difference in cost between clapboard and paint and what was now referred to as "double 4 heritage siding" would be $73,690. The Committee expressed sympathy for the owner but reiterated its recommendation that the re-application be rejected. However, a cohort of councillors, led by the tireless Deputy Mayor, now spoke in support of the owner's application, arguing that the substantial difference in cost was"onerous on the owner when the aesthetics of the property will not be detrimentally affected." The prohibition against the application of vinyl siding on this designated heritage building was characterized as a"clear example of over-regulation." Predictably the recommendation of the Committee was rejected, and the building reclad in powder-blue vinyl (Minutes, St. John's Municipal Council, 3 October 1994; Smith, 1994).11

47 The second type of damage has resulted from contextually inappropriate infill development. This was not always a problem. During the 1980s the City's non-profit housing agency made effective use of the municipal non-profit provisions of the National Housing Act to create some innovative residential in fill developments in the downtown. It was joined by Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation, and the Newfoundland and Labrador Housing Corporation, which also took the time and spent the money to 'get it right' by engaging the services of architects with a proven track record of sympathetic design in heritage areas (Figure 7). Alas, the days of such contextually appropriate development are long gone. Several new developments reflect only the Disneyfied version of heritage conjured up by developers who think that 'heritage' and 'quaint' are synonyms for a generic North American style of downtown architecture. Consider but two contemporary examples.

Figure 7. Municipal Infill Housing on New Gower Street.

Display large image of Figure 7

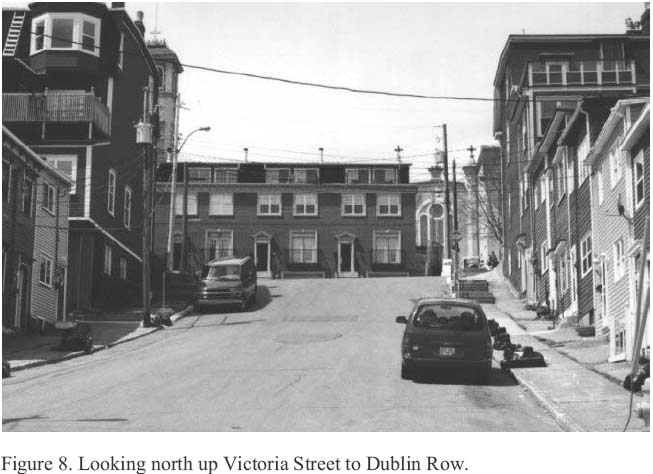

48 Many cities can boast of an inheritance of Georgian architecture, but St.John's cannot. The Great Fire of 1892 made sure of that. However, on a prominent site on Queen's Road, at the top of Victoria Street, which was once featured on a Heritage Canada Heritage Day poster, one finds a range of six brick-faced townhouses, their facades dominated by the entrance to an at-grade garage and french doors leading nowhere (Figure 8). The development is usually referred to as 'Dublin Row,' but sometimes as 'The Brownstones' so that, one assumes, potential buyers or tourists who do not know the difference between a brick and a piece of quarried stone can pretend they are in New York.

Figure 8. Looking north up Victoria Street to Dublin Row.

Display large image of Figure 8

49 The second example is 'Brittany Terrace' on what the developer, but nobody else, refers to as 'Old' Bond Street (Figure 9). Its eight townhouses replace the historic Bishop Spencer College, which was converted to condominiums, and later destroyed by fire. The advertisements boast that the rear side of the units are "clad in beautiful and durable concrete-fibre clapboard." The Bond Street side features an "antiqued brick facade [which] impresses upon you the enduring quality of a finely crafted structure designed to blend seamlessly with the streetscape, yet impose significance." The ground level entrance is "rarified by glass blocks," and is complemented by ersatz eave brackets and the "single-hung windows with half grills." These are advertised as examples of "heritage detailing," but are nothing less than a carnivalesque embarrassment.

Figure 9. Brittany Terrace.

Display large image of Figure 9

50 Both of these developments occupy prominent places in the heart of the HCA, but impose designs and materials completely foreign to it. Brick is a rare building material in St. John's, and virtually absent from the residential precincts of the downtown. The only contextual integrity which exists between these new developments and their milieu is in the advertisements. Unfortunately, in time, developments like these may come to define the heritage of the city, because most of what is now genuine will have disappeared. And the occupants who paid $275,000 for units in The Brittany, and up to $425,000 in Dublin Row, have a vested interest in ensuring that their houses do become the standard against which all others are measured.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

51 Construction activity in a historically sensitive area, whether it be renovations to existing buildings, or the creation of new ones, can either enhance or degrade the character of the immediate surroundings. The question of which result has occurred is a function of how one perceives the built environment. The design questions raised by construction activity, and differing attitudes towards modern materials, have created two opposing views. One is that new development should be permitted to reflect its own time, absolved of the need to defer, or pay heed to, its setting. This view would be antithetical to the designation of conservation areas. On the other hand, there are those who believe that there is merit in conserving, and protecting, the existing townscape. They would, therefore, favour the creation of conservation areas, and the protection of their character at all costs. This is done best by opposing all development, but insisting, when it does take place, that it copies the architecture of existing buildings (English Heritage and CABE, 2001). The latter view is based on the assumption that conservation areas are designated to maintain the historic character of an area, and that conservation should, therefore, be their sole purpose.

52 The implicit assumption of this paper is that when development takes place in a designated heritage conservation area it must be at least contextually appropriate. This does not require the absence of change, or an inflexible requirement that every construction project result in a building that is a slavish copy of its nineteenth-century neighbours. It does, however, mean that all buildings, new and renovated, must enhance the existing environment by sympathizing with it in terms of both design and materials. Not everyone would agree that this is a valid assumption, of course, and it does beg an important question: would it matter if the genuine heritage of St. John's nineteenth-century streetscapes were to disappear?

53 There is overwhelming national and international evidence that it would. The historic built environment is generally considered an important national as well as local legacy. It is often viewed as an asset incorporating a long-term investment of skills and resources that we squander or degrade at our peril. Many historic English towns suffered great indignities during the 1960s at the hands of local authorities and developers trying to accommodate the huge post-war increase in vehicular traffic, the need for more housing, and the national preoccupation with replacing the old and familiar with the new and modern. The fabric of many historic towns was damaged by thoughtless haste on the part of well-intentioned people who should have known better. The modernist spirit of the Festival of Britain, when brought to bear on townscapes, had inevitable results. In too many cases towns were left with a High Street scarred by over-sized, inappropriately designed new buildings, and a town center surrounded by a nasty ring road.

54 Belated recognition of the problem led to national legislation which established the key principle that "demolition of an historic building is not justified simply because redevelopment is economically more attractive than repair and re-use, or because a developer acquired a building at a price reflecting the potential for redevelopment" (Department of the Environment, 1994). Legislation arising from controversies in the 1960s requires that development in historic areas must either preserve or enhance them. The courts subsequently interpreted this to mean that an area must not be made worse as the result of development. The implementation of this requirement is made difficult by the fact that in every case somebody must make a value judgment, but at the very least the legislation and its interpretation imposes some measure of control. Alas, this is lacking in Canada. We have no national heritage policy, and there is none in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador either.

55 Efforts are being made to rectify the situation. In 2001 the Department of Canadian Heritage and Parks Canada, on behalf of the Government of Canada, announced the Historic Places Initiative (HCI), described as "the most important federal heritage conservation proposal in Canada's history" (Department of Canadian Heritage, 2004). It is based on the premise that the federal government cannot act alone to address problems in the heritage sector, and that citizens and other levels of government must also be mobilized. The Initiative provides for the development of three tools. The first is the internet-based Canadian Register of Historic Places, which is intended to identify and promote not only the 850 designated national historic sites, but the estimated 20,000 other sites of local, provincial and territorial significance. This will be supported by a set of standards and guidelines, and a certification process to ensure that all conservation work meets agreed-upon conditions (Bulte, 2001; Frood, 2002). Parks Canada is responsible for another new venture, the Commercial Heritage Properties Incentive, which provides financial support for taxable Canadian corporations interested in making adaptive reuse of heritage properties. Work began on the HCI during the summer of 2004, coinciding with a change in government. Whether the new government will maintain these initiatives remains to be seen.

56 None of these federal initiatives involve any degree of protection to the places listed in the Register, most or all of which will be individual buildings, perhaps because the Canadian constitutional reality is that the federal government has no jurisdiction over cities. The 2004 Auditor General's report decried the fact that only one-third of all federal heritage buildings are in better than "fair" condition, in part because Parks Canada is allocated $100 million less than it needs to fulfill its mandate. But even if it had sufficient funds, it could protect the national parks over which it has clear and uncontested jurisdiction, but not municipal heritage districts (Simpson, 2004).

57 Each generation makes its own decisions about how to deal with the places in which it lives. Through most of our history this has been done in the absence of constraints, so at any time the historic built environment is a palimpsest reflecting the cumulative effect of the 'good' as well as the 'bad' decisions. And no matter how much people care about their historic environment it is the context in which all new development occurs, so time-and resource-hungry conflicts are inevitable.

58 The historic townscape is increasingly recognized as the essential base for the support of cultural tourism, defined as travel to experience different cultural environments. The 1992 Strategic Plan for Newfoundland identified the future growth potential of tourism, and advocated its development. A new "Vision for Tourism," based on the assumption that the province has a strong comparative advantage in both adventure and cultural tourism, appeared almost a decade later (Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2001). The latter is seen to consist primarily of the archaeological, palaeontological and historic resources of smalltowns such as Battle Harbour, Brigus and Trinity. It makes not a single reference to the built environment generally, or to St. John's in particular. And, while admitting that the cultural and historical resources have historically been underfunded, there is no indication that any future emphasis will be re-directed towards urban built heritage. The fact that preservation of the built environment is not a high priority item at the provincial level may help explain why the same is true at the municipal level.

59 Downtown St. John's is believed to be a tourist attraction, with built heritage a critically important part of the "product package" on offer. Unfortunately, neither the province nor the City appear to understand that there are two necessary conditions for the successful development of a thriving cultural tourism sector: possession of an appropriate physical resource which can provide the all-essential sense of place, and its continued maintenance (Heritage Canada Foundation, 2002). The single most important contributor to this sense of place is the common, everyday vernacular environment. But there is an important caveat. It must be authentic, unique to the destination, and not created solely for the purpose of attracting tourists (Webb, 2002; Wheelock, 2002; Canadian Tourism Commission, 2004: 10-11). One can legitimately ask how many tourists will be interested in making the expensive and logistically complicated trip from the mainland to Bond Street to see fake eave brackets embellishing an "antiqued" brick facade on a street innocent of anything but wooden cladding, or to Queen's Road to take photos of a row of fake "Georgian" townhouses in a city that never had any genuine ones?

RECENT POLICY CHANGES

60 Several decisions by the Council in 2004 suggest that there may have been a significant shift of opinion with respect to heritage conservation. The City has agreed in principle with the recommendation that the boundaries of the HCA should be expanded, but subdivided into three zones, each with differing levels of design control (Jackson, 2003a; PHB Group, 2003). In the commercial/institutional core (including the Water Street Historic District designated by the HSMBC) no significant exterior changes of any kind would be permitted. In the residential areas "minimal" changes would be permitted. Recommendations regarding new development guidelines in the historic Battery neighbourhood, which overlooks the entrance to the harbour, were also approved in principle in 2004 (PHB Group, 2004).

61 The introduction of long-overdue design controls on the style and size of doors and windows, and house colours, and some aspects of the flexibility of the proposed new regulations have been applauded by the Heritage Advisory Committee. However, the new regulations would permit the use of narrow vinyl siding, and there is concern that the character of many downtown streetscapes could be changed very quickly (Jackson, 2003b).

62 The intention of the proposed new regime is to have an approval process for development within the HCA that is "more fluent, more rigorous, but less dependent on the Heritage Advisory Committee" (PHB Group, 2004: 75) because there will now be a full-time Heritage Officer (Jackson, 2004). Unfortunately the new officer will have less to safeguard now than in the past.

CONCLUSION

63 More than a decade ago, the City Planner wrote that the heritage policies in the St. John's Municipal Plan were not supported by appropriate planning tools. He warned that "flexible controls subject to a political fiat ... will not get the job done. Without a clear definition of what heritage means, and a clear formulation of strategies to preserve it, it will be impossible to achieve the desired objectives" (de Jong, 1991). His advice fell on deaf ears, with predictable consequences. St. John's was once a Canadian heritage leader, but has not kept pace with the best of contemporary practice in heritage conservation planning. Benign rather than wilful neglect of the heritage area has permitted a "drift from heritage purism" (Tunbridge, 2000: 282), and a creeping deterioration of the visual integrity of its previously uniform streetscapes. One of the Area's principal defining characteristics has been irreparably damaged as a result. It has also contributed to uncertainty on the part of investors who, especially if they are based on the mainland, are used to a greater level of certainty about development and planning approval in historic districts than one can count on in St. John's (Canning and Pitt et al., 2001).

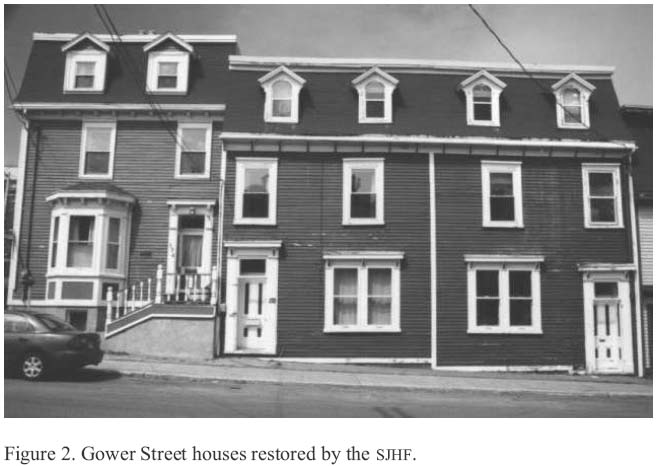

64 One can still find small pockets of carefully restored traditional houses in the heart of old St. John's, and some sensitive restoration and contextually appropriate private infill development has taken place (Figure 10). But years of uncontrolled renovations have seriously compromised the integrity of the HCA as a whole. The absence of strong public support for the idea of heritage conservation, and an unwillingness on the part of the majority to accept the limitations on individual behaviour that it would entail, has allowed a slow, steady erosion of the finely detailed streetscapes which were the hallmark of old St. John's, and the reason for the creation of the Heritage Conservation Area in the first place. Too late, perhaps, we will come to understand that the devil was in the details.

Figure 10. Private infill development on Prescott Street

Acknowledgements

Research assistance for the project on which this paper is based was provided by Cheryl MacLean, Carley Williams and Emily Hobbs. Charles Conway of the Memorial University Cartographic Laboratory was a constant source of help and inspiration, as always. The financial support provided by the Memorial University Career Experience Programme (MUCEP), the Dean of Arts and the Vice-President (Academic) is gratefully acknowledged.References

Ashworth, G. (1997). "Conservation as preservation or as heritage: Two paradigms and two answers." Built Environment 23: 92-102.

Ashworth, G. and J. Tunbridge (1990). The Tourist-Historic City. London: Belhaven Press.

Atwood, M. (1989). Cat's Eye. Toronto: Seal Books.

Baer, W.C. (1995). "When old buildings ripen for historic preservation: A predictive approach to planning." American Planning Association Journal 61: 82-94.

Bulte, S.D. (2001). Luncheon address to the 2001 Heritage Canada Foundation Conference. Preservation Pays: The Economics of Heritage Conservation. Proceedings of the Heritage Canada Foundation Conference, 38-39.

Canadian Tourism Commission (2004). Packaging The Potential. Canada: Destination Culture. Proceedings of a Symposium on Cultural and Heritage Tourism Products. Montreal, 1 May.

Canning and Pitt Associates, M. Denhez, J. Weiler and Sheppard Case Architects, Inc. (2001). Downtown St. John's Strategy for Economic Development and Heritage Preservation.

City of St. John's (1977). The Heritage Bylaw of the City of St. John's.

——— (1984). St. John's Municipal Plan.

——— (1989). Planning Area Development Scheme for Planning Area 1.

——— (1990). St. John's Municipal Plan.

——— (1991). "Public Hearing on Vinyl Siding: Background information and submissions." 24 September.

——— (1994). The 1994 Development Regulations.

——— (2003). St. John's Municipal Plan. de Jong, J.A. (1980). "Comments on the Heritage Bylaw Review." (mimeo).

———. (1991). "Some observations on the public hearing of 1991-09-24." (mimeo).

Department of Canadian Heritage website (2004). <www.pch.gc.ca>. Accessed 30 August.

Department of the Environment, and Department of National Heritage (1994). PPG 15: Planning and the Historic Environment.

English Heritage (2000). The Power Of Place: The future of the historic environment.

English Heritage and CABE (Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment) (2001). Building In Context: New Development in Historic Areas.

Evening Telegram (1977). "City Council favors compensation for residents of heritage area." 24 March, p. 7.

——— (1991a). "Council overturns heritage regulation." 12 March, p. 7.

——— (1991b). "Enforce heritage bylaw." Editorial, 26 April, p. 3.

Fitch, J.M. (1990). Historic Preservation: Curatorial Management Of The Built World. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia.

Frood, P. (2002). "Built heritage places and heritage tourism." Discovering Heritage Tourism: Proceedings of the Heritage Canada Foundation Conference, Halifax, 26-29 September: 5-6.

Galbraith, J.K. (1980). "The economic and social returns or preservation." In National Trust for Historic Preservation, Preservation: Toward an ethic in the 1980s, 57-62.

Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (2001). Vision For Tourism in Newfoundland and Labrador in the Twenty-First Century.

Graham, B.J., G.J. Ashworth and J.E. Tunbridge (2000). A Geography of Heritage.

Gushue, J. (1988). "Heritage drafted into political arena." Sunday Express, 18 September, p. 3.

Haines, E. (1977). "Heritage Area to cover 65 acres: Proposed conservation area would rival

Halifax project." Evening Telegram, 25 March, p. 3.

Heritage Canada (2002). Discovering Heritage Tourism: Proceedings of the Heritage Canada Foundation Conference, Halifax, 26-29 September.

——— (2001). "New survey confirms Canadians care about their heritage." Heritage 4: 17-18.

Hewison, R. (1989). "Heritage: An interpretation." In D.L. Uzzell, ed., Heritage Interpretation. New York: Belhaven, 15-23.

Heywood, R. (1993). "Report of the Commissioner on the City of St. John's Municipal Plan Review, 1992, and the City of St. John's Municipal Plan amendment concerning Planning Area II." (mimeo).

Hubbard, P. (1993). "The value of conservation: A critical review of behavioural research." Town Planning Review 64: 359-73.

Hunt, G. (1976). "Heritage Conservation Area proposed: Second plan nearing completion to revitalize older part of city." Evening Telegram, March 23, p. 3.

Jackson, C. (1991). "Residents opposing vinyl siding dominate heritage area meeting." Evening Telegram, 25 September, p. 9.

———. (2002). "Councillors clash over heritage policy." Telegram, 19 June, p. 5.

———.(2003a). "Balancing heritage and development: Report makes many suggestions to retain city's historical uniqueness." Telegram, 29 May, p. 5.

———. (2003b). "Committee could lighten its load." Telegram, 13 September, p. 3.

———. (2004). "Council charged by Battery report." Telegram, 26 August, p. 5.

Knight, J.W. (1980). "Saving Old St. John's." Canadian Heritage: 59.

Larkham, P.J. (1999). "Conservation and management in U.K. suburbs." In R. Harris and P.J. Larkham, eds., Changing Suburbs: Foundation, Form and Function. London: E and FN Spon, 239-68.

Ley, D. (1996). The New Middle Class and the Remaking of the Central City. NewYork: Oxford University Press.

Light, D. and R. Prentice (1994). "Who consumes the heritage product? Implications for European heritage tourism." In G.J. Ashworth and P.J. Larkham, eds., Building A New Heritage: Tourism, Culture and Identity in the New Europe. London: Routledge, 90-118.

Lowenthal, D. (1996). Possessed By The Past: The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History. New York: Free Press.

Lynch, D. (1972). What Time Is This Place? Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McMillan, A. (1990). "Memorandum to the Chairman, Heritage Advisory Committee re: Siding in Maritime municipalities and St. John's." (mimeo).

Miller, B. (1975). "Heritage Conservation Areas: What they mean to St. John's." Evening Telegram.

Mitchell, C.J.A., R.G. Atkinson and A. Clark (2001). "The creative destruction of Niagara-on-the-Lake." The Canadian Geographer 45: 285-99.

O'Brien, K. (2003). Personal communication with Supervisor of Planning and Information, Department of Planning, City of St. John's.

O'Dea, S. (1981). "The St. John's Heritage Conservation Area: The politics of preservation." Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Architectural Historians, Victoria, BC. (mimeo).

———. (2004). Personal communication with former Chairman of the Heritage Advisory Committee, City of St. John's.

PHB Group (2003). "St. John's Heritage Area, Heritage Buildings and Public Views." A report presented to the St. John's Municipal Council.

———(2004). "The Battery: Development Guideline Study." A report presented to the St. John's Municipal Council.

Parkes, D. and N. Thrift (1980). Times, Spaces, Places: A Chronogeographic Perspective. New York: Wiley.

Pelham, C. (1978). "N.I.P. Plus: Heritage Canada's Area Conservation Program." Impact 1: 11-13.

Phillips, R. (1975). "Area Conservation: Our program." Heritage Canada 1: 16-17.

Pollara Strategic Public Opinion and Market Research (2000). A Pollara Study Concerning Heritage Conservation Issues In Canada. Toronto, ON.

Riopelle, C. (1978). "Redeveloping St. John's: A model for Canada." Canadian Building (April), 39-42.

Sharpe, C.A. (1986). Heritage Conservation and Development Control in a Speculative Environment: The case of St. John's. Research and Policy Paper No. 4, Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

———. (2005). "A Garden Suburb on the Edge: Churchill Park, St. John's, Newfoundland." Canadian Geographer (forthcoming).

Sheppard, Burt and Associates and Arends and Associates (1976). St. John's Heritage Conservation Area Study.

Simpson, J. (2002). "When they poll the know-nothings." Globe and Mail, 11 December, A15.

———. (2004). "Another federal scandal." Globe and Mail, 9 April, A15.

Smith J. (1994). "Wells replaces mayor by trying to stifle O'Neill." Evening Telegram, 4 October, p. 5.

———. (1993). "Council break heritage rules." Evening Telegram, 30 November, p. 3.

Sweet, B. (1998). "Wells versus staff on heritage." Telegram, 15 January, p. 3.

Tunbridge, J.E. (1981). "Conservation Trusts as geographic agents: Their impact upon landscape, townscape and land use." Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, N.S. 6: 110-125.

———. (1987). Of Heritage and Many Other Things: Merchant's Location Decisions In Ottawa's Lower Town West. Discussion Paper 5, Department of Geography, Carleton University.

———. (2000). "Heritage Momentum or Maelstrom? The case of Ottawa's Byward Market." International Journal of Heritage Studies 6: 269-91.

———. (2001). "Ottawa's Byward Market: A festive bone of contention?" The Canadian Geographer 45: 356-70.

Tunbridge, J. and G.J. Ashworth (1996). Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict. Toronto: Wiley.

Wall, G. (2002). "New trends in heritage tourism." Discovering Heritage Tourism: Proceedings of the Heritage Canada Foundation Conference, Halifax, 26-29 September: 16-19.

Wall, K.L. (2002). "Old Strathcona: Building character and commerce in a preservation district." Urban History Review 30: 28-40.

Walsh, K. (1992). The Representation Of The Past: Museums and Heritage in the Post-Modern World. London: Routledge.

Warren and Hawes Limited, K. Paul and Associates and Barlow and Associates (1981). St. John's Heritage Area Development Study.

Webb, A.J. (2002). "Heritage tourism in the United States." Discovering Heritage Tourism: Proceedings of the Heritage Canada Foundation Conference, Halifax, 26-29 September: 12-15.

Webber, D. (1979). "The Heritage Look — Program II." St. John's Heritage Foundation (mimeo).

Wheelock, R. (2002). "Preservation and Presentation: Some thoughts on the role of the Canadian TourismCommission andHeritageTourism." Discovering Heritage Tourism: Proceedings of the Heritage Canada Foundation Conference, Halifax, 26-29 September: 3-4.

Notes