Research Notes

Cultural Heritage Tourism along the Viking Trail:

An Analysis of Tourist Brochures for Attractions on the Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland

Craig T. PalmerUniversity of Missouri-Columbia

palmerct@missouri.edu

Benjamin Wolff

bj_wolff@hotmail.com

Chris Cassidy

c.l.cassidy@gmail.com

INTRODUCTION

1 THE GROWING ANTHROPOLOGICAL INTEREST in tourism has been primarily due to tourism’s large, and often uneven, economic impact on people around the world (Desmond 1999, xvii; Fotsch 2004). Additionally, a great deal of tourism is focused on the cultural diversity that makes up the subject matter of cultural anthropology. This diversity is the primary "attractor" (what attracts tourists to an area, see Smith 1977/1989, 4-6) of visitors in many tourism industries. Diversity plays a secondary, or other important role, in many others. This paper examines the function of different cultural heritage categories in the tourist promotion of the Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland. It also includes a discussion of how tourist brochures take the archaeological evidence from a small, thousand-year-old Norse settlement and use it as a dominant part of the area’s ethnic heritage as a strategy to attract tourists.

CULTURAL HERITAGE TOURISM

2 There are many ways to categorize forms of tourism, and Bruner notes that any typology of tourism designed for one setting may be of limited use in analyzing the complexity of tourism in other times and places (2005, 71). Adler points out, for example, that starting in the late eighteenth century types of tourism were known as "travel styles," and that "many travellers overtly gave themselves and their journeys such labels as ‘romantic,’ ‘picturesque,’ ‘philosophical,’ ‘curious,’ and ‘sentimental.’" (Adler 1989, 1371-2). We follow the more recent practice of dividing tourism into categories on the basis of "attractors" — things which encourage people to attend a site or consume a commodity. Although there are many ways of creating "categories of tourist attractions" (Yale 1991, 2), most studies focused on tourist attractors attempt to answer the question: "What are the forces that cause people to leave home during their leisure time?" (Nash 1981, 464). This study focuses upon words that evoke attractors in tourist brouchres. Specifically, we examine attractors that use categories of people defined (at least implicitly) as sharing cultural traditions due to a common ancestry, and as distinct from other categories of people on the basis of this asserted ancestry. It is this focus on both the distinctness of a culture, and the extension of that culture into the past, which makes this a study of "cultural heritage" tourism.

3 The "cultural" part of the term "cultural heritage" requires that the category include a distinctiveness, regardless of what else may distinguish the category of people. "Heritage" has been a "buzz word" of the tourism industry since the 1970s (Yale 1991, 20-21). Although there is debate over how narrowly to define "heritage" (Garrod and Fyall 2000; Poria et al. 2001), there is general agreement that to qualify as cultural "heritage" the cultural distinctiveness of the attractor must at least be perceived as having a significant temporal dimension. This is because "strictly speaking, heritage refers to that which has been or may be inherited ..." (McCrone et al. 1995, 1; see also Yale 1991, 21).

4 The direct or indirect contact with people whose cultural behaviours the tourist industry portrays as having been distinct over an extended period of time plays an important role in many tourist industries. Indeed, some researchers have stressed that tradition or cultural heritage is the "product" most often consumed in many tourist industries (McCrone et al. 1995, 20; Alsayyad 2001; Timothy and Boyd 2006). Further, there are other attractors that are similar and may overlap with cultural heritage tourism, such as "ethnic" tourism. As long as "ethnicity" is seen to have a cultural as opposed to "racial" basis, then ethnic tourism also involves the two ingredients of culture and a temporal dimension. This is implied by the use of the phrase "cultural background" when van den Berghe writes: what defines ethnic tourism is the nature of the tourist attractant: ethnic tourism exists where the tourist actively searches for ethnic exoticism. In Weiler and Hall’s definition, ethnic tourism is ‘travel motivated primarily by the search for the first hand, authentic and sometimes intimate contact with people whose ethnic and/or cultural background is different from the tourist’s’ (van den Berghe 1994, 8). The same cultural and temporal dimensions are also typically found in "tribal tourism," and, at least in some instances, of what is sometimes referred to as "nation" tourism. Further, as Cogswell points out, tourism focuses on a "way of life" which also has connotations of both culture and heritage, especially when combined with the term "folk," as in "fisherfolk" (e.g., "come experience the way of life of the local fisherfolk") (Cogswell 1996; Nadel-Klein 2003).

5 There is also considerable overlap between "cultural heritage" tourism and "culture" tourism, when both cultural and historical dimensions are found in culture tourism. Such a temporal dimension is illustrated in the subtitle to the book edited by Rothman (2003) The Culture of Tourism, the Tourism of Culture: Selling the Past to the Present in the American Southwest. Moscardo summarizes the relationship between these two forms of tourism when he writes, "This chapter is concerned with two interrelated forms of tourism, that which is focused on the past (heritage) and that which is focused on the present (cultural) way of life of a visited community" (Moscardo 2000, 3). The overlap between these categories of tourism is incomplete because some attractors in culture tourism, such as a modern art museum or a skate park, may lack a significant temporal dimension.

6 There is a similar partial overlap between cultural heritage tourism and "heritage or historical" tourism. Although many "heritage" and "historical" attractions refer to cultural heritage, a historical or heritage attraction may place little emphasis on any distinct cultural category of people. For example, a museum documenting the history of a form of technology may not discuss the cultural categories of the people who invented that technology. Further, a heritage attraction may not refer to humans at all. For example, heritage tourism may only refer to some part of the natural environment, such as "beautiful scenery," which has been in an area for a period of time and/or is hoped to be preserved in an area for a long time (Yale 1991, 21) . Even less overlap is typically found between cultural heritage tourism and nature tourism, ecotourism, or adventure tourism (see Buckley 2003; Orams 2001). However, although these attractors may be distinct from cultural heritage tourism, nature-based attractions can be intertwined with both dimensions of cultural heritage tourism in a variety of ways. For example, tourists may be encouraged to explore the beautiful land where a certain culture lived for centuries, and may be guided on such explorations by people perceived to be culturally distinct. Even recreational tourism such as golf vacations may include some reference to the exotic cultural heritage of the area surrounding a golf course.

7 This emphasis on the two seemingly simple criteria of cultural distinctiveness and temporal dimension should not obscure the fact that cultural heritage "is a complex notion, involving the past, contemporary social understandings of places, and the active construction of the past" (Baram and Rowan 2004, 5; see also Cheung 1999). Added complexity stems from the fact that "the past is opened not only to reconstruction but to invention" (McCrone et al. 1995, 1; Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983; Pearce et al. 2000; Harvey 1996). This complexity is perhaps best seen in the contentious debate about "authenticity," a crucial concept in the study of cultural heritage tourism (Wang 1998; Reisinger and Steiner 2006; Chhabra et al. 2003; Waitt 2000; Garrod and Fyall 2000; Poria et al. 2001; Apostolakis 2003).

AUTHENTICITY

8 One aspect of "authenticity" is the correlation between the actual ancestry of people and the cultural category to which they are assigned in the attraction. In many cases there may be no correlation, or the links may be impossible to determine. Sometimes this measure of authenticity may be negotiated through light-hearted banter with the tourist (Halewood and Hannam 2001). Such situations have produced what Fife refers to as "Post-modern tourism," in which tourists "delight in the ironic mockery of modernist conceits such as the notion that ‘true history’ or ‘authentic reconstructions’ are within the realm of human attainment" (Fife 2002, 53; see also Halewood and Hannam 2001). Even when there is a correlation between the assigned cultural category of the attraction and actual ancestry of the local people, there is still the question of the extent to which "traditional" behaviours have been "invented" as opposed to having being handed down from one generation to the next. The issue of authenticity is even more complex since the same attraction is often perceived by some tourists as authentic, but not by others, and people may mean very different things by "authentic" (see, Fife 2002; Halewood and Hannam 2001; Steiner and Reisinger 2006). Indeed, sometimes a "high perception of authenticity can be achieved even when the event is staged in a place far away from the original source of the cultural tradition." (Chhabra et al. 2003, 702). This point is important because "[m]uch of today’s heritage tourism product depends on the staging or re-creation of ethnic or cultural traditions." (Chhabra et al. 2003, 702).

9 Many anthropological studies take a critical approach to cultural heritage tourism, and the desirability of cultural heritage tourism is open to debate. For example, forms of cultural heritage tourism that include the performance of "traditional" behaviours have been interpreted and evaluated in many different ways. Ostensibly, this tourism is often used to "celebrate the difference and particularity of the performing group" (Desmond 1999, xvi). However, researchers often see such tourism as a multifaceted "contest over heritage" involving "tourists versus local peoples" (Baram and Rowan 2004, 5; see also Cheung 1999; Callahan 1998). In such situations, the outcome of this contest may be difficult to judge. Often this type of cultural heritage tourism is seen as harming the people whose heritage is being produced and consumed, while in other instances ethnic groups can use such a situation to raise their status (Adams 1997; Hampton 2005).

10 Most anthropologists studying cultural heritage tourism feel there is a need for "critical commentary" (Overton 1996, viii) and some studies explicitly aim to change negative images and stereotypes of indigenous populations (e.g., Li 2000; Buzinde et al. 2006). Many of these works also try to examine and change the power relations that allow some social groups to generate the images that play such a vital role in tourism. Although our own goal is not critical in this sense, we hope that our findings may be used in debates over socio-political aspects of culture change related to tourism.

THE SETTING

11 The Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland (GNP) was once home to the Beothuck, and other aboriginal populations. Around the year 1000 the Norse visited for a brief time. The French used the region as a fishing area in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, roughly the same period in which the British ancestors of its current residents settled there. Since that time, it has been populated mostly by people relying primarily on marine resources (especially cod) and secondarily on lumber and mining. Many of the patterns of culture and social interaction are based on this ecological adaptation of domestic commodity fishing in an island environment (Palmer 1995a; Palmer 1995b; Palmer 1995c; Palmer and Sinclair 1997). The semi-isolation of this area helped maintain distinctive traditional patterns of fixed gear fishing techniques, land inheritance, and other activities into the 1960s (Firestone 1967). These patterns of fishing evolved with the introduction of new technology, particularly the use of draggers during the 1960s and 1970s. Further changes occurred with the decline in cod harvests in the late 1980s and the subsequent moratorium on cod harvesting in1994 (Felt and Sinclair 1995; Palmer 2003). The official closure of the commercial cod fishery caused intensified competition for resources, especially among the dragger fleet because it now had to rely on alternative species such as shrimp. Today the region includes several dozen villages with populations of several hundred people or less, and the slightly larger Port au Choix and St. Anthony. Although some fixed gear and dragger fishing continues, the area has experienced significant out-migration since the collapse of the cod fishery (Palmer and Sinclair 2000; Palmer 2003). Many of the remaining residents have turned to tourism to earn a living (Fife 2002, 2004a, 2004b).

12 Tourism has long been seen as having great economic potential for Newfoundland and Labrador (see Overton 1996, 10-42). Thus, the images used as tourist attractors have been economically significant. While images of nature have dominated the attempts to attract tourists, human attractors have long been present. For example, a brochure from 1902 features a Newfoundland outport couple, and a brochure from the 1950s features a Newfoundland man playing the accordion (Overton 1996, 43). These images have focused on the unique Newfoundland outport culture; indeed, "romantic, nostalgic and patriotic themes" have been "the stock images and ideas of Newfoundland" used to attract tourists (Overton 1996, x). Not only has the authenticity of such images been questioned, but Overton suggests that "perhaps ‘Newfoundland culture’ is best thought of as an ‘invented tradition’" (Overton 1996, x).

13 The economic significance of images used to attract tourism means that control over these images brings corresponding economic power. Thus, Overton refers to "particular interests within Newfoundland mobilizing negative national/ethnic images to support their position" (Overton 1996, xi). For example, the post-Confederation period saw "new institutions catering to the arts, and other leisure-time activities (camping and tourism)" (Overton 1979, 223). This leads him to stress that it is important not only to question, "How and why have people come to see tourism as a path to development?" but also "Who have been the promoters of the industry?" (Overton 1996, x). This is particularly important because of the competitive nature of cultural heritage tourism (Apostolakis 2003).

14 Today the GNP offers two main categories of attractors: nature and cultural heritage. These are intertwined and it is difficult to distinguish which one is primary (Buckley 2003). For example, Fife states that there are four major tourist attractions on the GNP (L’Anse aux Meadows, Gros Morne, Port au Choix, and St. Anthony), and one (Red Bay) on the Labrador side of the Strait of Belle Isle (Fife 2002, 51). Only one of these (Gros Morne) relies on nature. Cultural heritage is the primary attractor to L’Anse aux Meadows, Port au Choix, and Red Bay, while St. Anthony combines nature (especially icebergs) with Newfoundland cultural heritage (especially the Grenfell mission).

CULTURAL HERITAGE TOURISM IN NEWFOUNDLAND

15 An examination of cultural heritage tourism on the Northern Peninsula is best performed within the context of other forms of cultural heritage tourism. One measure of the importance of cultural heritage tourism in Newfoundland is the names given to the roads that leave the Trans-Canada Highway and travel through the coastal villages located on the various peninsulas and bays that contain the vast majority of communities on the island. Tourists are informed of these names in many ways, including tourism web pages, road maps, and restaurant place maps (see Hanna and Del Casino, Jr. 2003, ix). Not only do the names of roads (or "tours") reflect the different attractors of Newfoundland tourism, but the names themselves become attractors. Some of the place names refer to aspects of physical geography (e.g., the Cape Shore, Cape Spear Drive), and others relate to biological aspects of nature (e.g., the Osprey Trail, the Caribou Trail). Other roads are named after historical figures (e.g., Captain Cook’s Trail), or more general aspects of history without an explicit emphasis on specific cultural heritage (e. g., the Admiral’s Coast, the Discovery Trail). Other names imply a unique Newfoundland cultural experience such as the Outport Adventure Trail or the Island Experience. The Killick Coast has connotations of emphasis on distinct Newfoundland culture because "killick" is a Newfoundland word for a type of anchor. However, there are also roads explicitly referring to cultural heritage. These include the Irish Loop, the Baccalieu Trail, the Dorset Trail, the Beothuck Trail, and the French Ancestors Route. It is within this context that the relationship between tourism and the discovery of archaeological evidence indicating a small thousand year old Norse settlement near the northern tip of the GNP (Fife 2002; 2004a; 2004b) becomes particularly significant. Perhaps most importantly, the attention given to this archaeological find in the 1970s and 1980s led to Route 430 (the main road on the GNP that runs along the west coast from Dear Lake to St. Anthony) being named the Viking Trail.

METHODOLOGY

16 Fife suggests that "Attention must be paid to the overall context of a site or a plurality of sites that form a single cultural theme in an area (such as a Viking village)" (2002, 58). We accomplished this by examining 101 tourist brochures for attractions along the Viking Trail that we collected during the summer of 2005. An attempt was made to collect every brochure at all locations along this route, duplicate brochures were then removed from the sample.

17 We selected tourist brochures as a source of data not only because they are explicitly used to attract tourists, but also because they play a large role in the social construction of tourism in this and many other areas. All tourism involves the transmission of a product to the tourist. In cultural heritage tourism "[c]ultural resources, or ‘traditions,’ are the raw materials from which selection is made" (Wells 1999.vii). However, instead of being directly consumed, "[t]hese selected resources are converted into products through interpretation, through a form of storytelling. What is transmitted, and the means of transmission, become the product" (Wells 1999, vii). Thus tourism is the "mediated consumption" of a product, and brochures are one of the common forms by which the consumption of cultural traditions and ethnicities are mediated and transmitted to tourists (Ooi 2002, 1). Tourist brochures, like maps, "are key texts through which tourist landscapes at historic sites are interpreted by visitors, often helping them to make the past meaningful in the present" (DeLyser 2003, 104; see also Jakle’s discussion of "Travel Books as a Data Source" 1985, 17; Burns 1999, 92; and Harvey for a description of different types of tourist brochures 1996, 59).

18 One way to make the past meaningful is to transform historical or archaeological artefacts into a cultural heritage or ethnic attraction. This is accomplished by converting the evidence from the past into a contemporary interaction with "a culture," and, in some instances, contact with living people who are portrayed as culturally different from the tourist. Thus, we coded the 101 brochures by both the cultural heritage category (Newfoundlander, Viking, English, Inuit, French, European, Maritime Archaic Indian, Paleo-Eskimo, Basque, and Irish), and by four categories of experiences:

- Interactions with a person of the cultural heritage category (e.g. "an evening of food, fun and feuds with the Vikings ...").

- Experiences of some aspect of the culture, such as food, crafts, music, or humour (e.g. "more than two hundred Newfoundland gifts and souvenirs").

- Experiencing the same things that members of the cultural heritage category experienced (e.g., "Experience the sense of history as you see from the water the coastline the Vikings saw over 1,000 years ago as they sailed into L’Anse aux Meadows ...").

- The mere mention of a cultural heritage in describing the location of the attraction (e.g., "Located ... at the end of the Viking Trail").

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

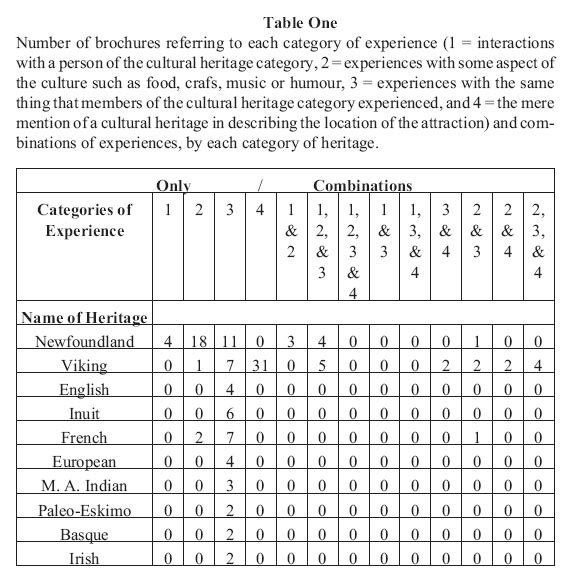

19 The importance of cultural heritage in the tourist industry of the Northern Peninsula is demonstrated by the inclusion of the name of a cultural heritage category in 79 of the 101 brochures. The results of our analysis can be seen in the two tables below. Table One shows the specific combinations of cultural heritage attractors found in each brochure. Table Two shows how many of each type of attractor, regardless of the presence of other types of attractors, were found for each cultural heritage attractor.

20 Although ten different (but not mutually exclusive) cultural heritage categories were named in our sample of brochures, two (Newfoundlander and Viking) were dominant. This is seen most clearly in category one attractors (contact with actual people of a designated cultural heritage), category two attractors (experience an aspect of a unique cultural heritage), and combinations of attractors that include category one and/or category two attractors. With only three exceptions (which mentioned category two French cultural attractors), all of the brochures using category one and/or two attractors were Newfoundlander and/or Vikings. The rest of attractors were category three (experience something that members of that cultural heritage category experienced). For this reason, our discussion focuses on the categories of Newfoundland and Viking as cultural heritage attractors.

Table One.

Number of brochures referring to each category of experience (1 = interactions with a person of the cultural heritage category, 2 = experiences with some aspect of the culture such as food, crafs, music or humour, 3 = experiences with the same thing that members of the cultural heritage category experienced, and 4 = the mere mention of a cultural heritage in describing the location of the attraction) and combinations of experiences, by each category of heritage.

Display large image of Table 1

21 Excluding purely directional references, Newfoundland is the most frequently mentioned category, being referred to in 41 brochures. All of the 35 references to a cultural heritage in category four (with regard to location only) were the result of the highway being called the Viking Trail. However, only 12 of the 79 brochures only mentioned a cultural heritage in the context of the location (i.e., located themselves on or near the Viking Trail). Thus, 67 of the 101 brochures included some reference to cultural heritage beyond simply being located on the Viking Trail. Even excluding such brochures, the category of Viking is easily the second most frequently mentioned category, appearing in 23 brochures. The dominance of these two categories is interesting given they are profoundly different in actual relevance to the history of the GNP. The numerous references to Newfoundland are not surprising given that "Newfoundlanders" are the dominant group in the area. In contrast, the actual presence of "Vikings" appears to have been limited to several dozen Norse individuals, who visited the GNP some 1000 years ago. Further, their occupation of the area is known only through a relatively small number of artifacts. This disproportionate use of the Viking category in the brochures is also seen when comparing the Viking category with the French category. The French played a major role in the history of the area, and this presence is well documented in several impressive museums on the GNP. However, the French are invoked in tourist brochures far less frequently than are Vikings.

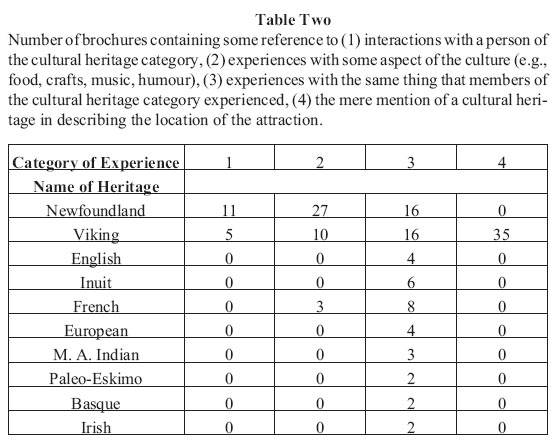

Table Two.

Number of brochures containing some reference to (1) interactions with a person of the cultural heritage category, (2) experiences with some aspect of the culture (e.g., food, crafts, music, humour), (3) experiences with the same thing that members of the cultural heritage category experienced, (4) the mere mention of a cultural heritage in describing the location of the attraction.

Display large image of Table 2

22 Given the differences in the real presence of the Newfoundlanders and Norse people in the area, one might expect that category one experiences (actual interaction with living members of the category) would be very common for the Newfoundland category, but absent for the Viking category. Indeed, one might expect the Viking category to be limited to the category three experience (i.e., experiencing the same area the Vikings experienced in the past) with perhaps a small number of references to aspects of Viking culture related to the nature of the Viking artifacts found in the area. Unlike in areas where descendants of the Norse remained (Halewood and Hannam 2001), no claim of authenticity through descent is possible in this area. However, our brochure sample was far different. Although promises of category three experiences were the most common for the Viking category, eleven brochures referred to category two experiences (experiences of some aspect of the culture, such as food, crafts, music, or humour), and five brochures referred to actual interactions with living members of the category of Vikings (category one experiences). These category one experiences are obviously meant in only a metaphorical sense (i.e., contact with people portraying Vikings), as is illustrated in one brochure by the statement: "We Vikings love games and competitions...." This finding is even more interesting when it is noted that no such experiences with members of other categories (e.g., French, Inuit, Maritime Archaic Indian, and Basque) were promised in any of the brochures.

23 We suggest two possible explanations for this pattern. First, the uniqueness, and the historical significance, of the Viking presence on the GNP is obviously part of the reason for its predominance in tourist brochures for the area. In contrast, many of the European cultural heritages mentioned in the brochures exist in other areas, both within and outside North America. The presence of these categories on the GNP lacks the distinctive historical significance of the Vikings. Similarly, references to past indigenous residents are found in other areas of North America. Consequently, the status as the site of the only authenticated Norse site in North America justifies some of the dominance of the Viking category relative to these other cultural heritage categories. The frequent category four references to Vikings (but not to other cultural heritage categories) due to the naming of the highway after the Vikings is easily explainable in this way. The number of category one (in particular) and category two references to Vikings are less readily explained. Although category one and category two experiences with "Newfoundlanders" may often involve some degree of "inauthenticity" in the sense that Newfoundlanders may behave in ways they would not if tourists were not present, the degree of "inauthenticity" of Vikings is more extreme.

24 Thus, the clearest puzzle found in our analysis of tourist brochures is the frequent use of blatantly inauthentic Viking attractions. This is particularly interesting because there were only three references to category two and no references to category one experiences with any of the other cultural heritage categories mentioned in brochures. That is, while there were invitations to "sample our famous Viking Burger" or to spend "an evening of food, fun and feuds with the Vikings" there were no references to Maritime Archaic Indian dances, Paleo-Eskimo storytelling, or authentic Basque dinners. There were also no local residents dressed in Inuit, English or French traditional garb. It is difficult to explain this situation by the historical significance of the Norse presence on the GNP. Rather, we propose that the explanation must also include a factor found, paradoxically, in the very nature of the tenuous and remote connection of actual Vikings to this area. The lack of a real connection to any people currently living in the area allows blatantly inauthentic portrayals of this particular cultural heritage without concern about offending current members of the cultural category. Dressing like Inuit, or even Maritime Archaic Indians, to entertain tourists would likely be met with protest from those who associate themselves with these categories in some way.

25 The inappropriateness of the name "Viking" itself supports this hypothesis. As Brown commented: "I wish, how I wish, that people would get over this obsession with Vikings.... Viking used accurately refers to a period when Norse warriors were raiding the Atlantic coast of Europe. The Norse who came to Vinland were farmers, merchants and sailors — the story is dramatic enough without Hollywood hyperbole" (Brown 2003, 241). But those who design tourist attractors consider the more "blood-thirsty image" of Viking to be more effective than evoking the concept of the Norse (Hannam and Halewood 2006, 17). The more precise term, "Norse," is not entirely absent from the brochures, but it is overwhelmed by the ubiquitous use of the term "Viking." A "Norseman" shop can be found on the Peninsula, it is in the "Viking Mall."

CONCLUSION

26 Tourism involves the transmission of a product to the tourist. One of the goals of the anthropology of tourism is to study the elements and means of this transmission. The tourist brochure is a useful tool for both tourists and those attempting to attract tourists. Tourists seeking particular experiences use brochures to make decisions about where to visit, and the residents of an area use brochures to attract tourists to their particular product. Although it is difficult to quantify the influence brochures have on the perceptions potential tourists have of an area, brochures provide useful information to anthropologists wanting to understand the process of tourism (Mercille 2005). In cultural heritage tourism, this process involves all of the sociopolitical complexity inherent in notions of cultural diversity and such controversial concepts as authenticity.

27 Of great importance is the question of who controls the text and images in brochures. The provincial or federal government designed some, while private residents created others. In all cases, what others have done influences choices, and what has apparently been successful in attracting tourists in the past. Future research will address the factors that influenced the decisions about the selections of specific words and images used in brochures. One conclusion is possible at this point. In the case of the Great Northern Peninsula, the way that tourist brochures portray a fleeting Norse settlement from a thousand years ago to create the cornerstone of the modern tourist industry in the region reveals much of this complexity. It suggests that the portrayal of any cultural heritage is likely to be influenced by both the actual existence of that cultural heritage in an area and current political sensitivities regarding how that cultural heritage can be portrayed. This finding suggests that such issues need to be addressed in future studies of tourism.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Amber L. Palmer, Fran L. Palmer, Clara M. Wright, Ella M. Wright, and all of the people on the Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland who assisted us with this research.Referenced Cited

Adams, Kathleen M. 1997. "Ethnic Tourism and the Renegotiation of Tradition in Tana Toraja (Sulawesi, Indonesia)." Ethnology 36:309-320.

Adler, Judith 1989. "Travel as Performed Art." The American Journal of Sociology 94(6): 1366-91.

Alsayyad, Nezar ed. 2001. Consuming Tradition, Manufacturing Heritage: Global Norms and Urban Forms in the Age of Tourism. London: Routledge.

Apostolakis, Alexandros 2003. "The convergence process in heritage tourism." Annals of Tourism Research 30(4):795-812.

Baram, Uzi and Yorke Rowan 2004. "Archaeology after Nationalism: globalization and the consumption of the past." In Marketing Heritage: Archaeology and the Consumption of the Past. Yorke Rowan and Uzi Baram, editors. Walnut Creek, CA: Alta-mira Press 3-23.

Brown, Stuart C. 2003. "Review of The Viking Discovery of America: The Excavation of a Norse Settlement in L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, by Helge Ingstad and Anne Stine Ingstad."Journal of Newfoundland and Labrador Studies 19(1): 240-241.

Bruner, Edward M. 2005. Culture on Tour: Ethnographies of Travel. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Buckley, Ralf 2003. Case Studies in Ecotourism. Cambridge, MA: CABI Publishing.

Burns, Peter M. 1999. An Introduction to Tourism and Anthropology. London: Routledge.

Buzinde, Christine N., Santos, Carla Almeida and Stephen L.J. Smith 2006. "Ethnic representations Destination Imagery." Annals of Tourism Research 33(3):707-728.

Callahan, R. 1998. "Ethnic Politics and Tourism a British Case Study." Annals of Tourism Research 25(4): 818-836.

Cheung, Sidney, C.H. 1999. "The Meanings of a Heritage Trail in Hong Kong." Annals of Tourism Research 26(3): 570-588.

Chhabra, Deepak, Healy, Robert, and Erin Sills 2003. "Staged Authenticity and Heritage Tourism." Annals of Tourism Research 30(3): 702-719.

Cogswell, Robert 1996. "Doing Right by the Local Folks: Grassroots Issues in Cultural Tourism." In Keys to the Marketplace: Problems and Issues in Cultural and Heritage Tourism. Patricia Atkinson Wells, editor. Middlesex, UK: Hisarlik Press.

Desmond, Jane C. 1999. Staging Tourism: Bodies on Display from Waikiki to Sea World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

DeLyser, Dydia 2003. "‘A Walk Through Old Bodie’: Presenting a Ghost Town in a Tourism Map," 79-107. In Mapping Tourism. Stephen P. Hanna and Vincent J. Del Casino, Jr., editors. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Felt, Lawrence F. and Peter R. Sinclair 1995. Living on the Edge: The Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland. St. John’s, Newfoundland: Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Fife, Wayne 2002. "Performing History: Vikings and the Creation of a Tourism Industry on the GNP of Newfoundland," 51-62. In Identities, Power, and Place on the Atlantic Borders of Two Continents: Proceedings from the international research linkages workshop on Newfoundland and Labrador Studies and Galician Studies. Sharon R. Roseman, editor. St. John’s, Newfoundland: Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Fife, Wayne 2004a. "Semantic Slippage as a New Aspect of Authenticity: Viking Tourism on the Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland." Journal of Folklore Research 41(1): 61-84.

Fife, Wayne 2004b. "Penetrating Types: Conflating Modernist and Postmodernist Tourism on the Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland." Journal of American Folklore 117(464): 147-167.

Firestone, Melvin 1967. Brothers and Rivals: Patrilocality in Savage Cove. St. John’s, Newfoundland: Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Fotsch, Paul M. 2004. "Tourism’s Uneven Impact: History on Cannery Row." Annals of Tourism Research 31(4): 779-800.

Garrod, Brian and Alan Fyall 2000. "Managing heritage tourism." Annals of Tourism Research 27(3): 682-708.

Halewood, Chris and Kevin Hannam 2001. "Viking Heritage Tourism: Authenticity and Commodification." Annals of Tourism Research 28(3): 565-580.

Hampton, Mark P. 2005. "Heritage, local communities and economic development." Annals of Tourism Research 32(3): 735-759.

Hanna, Stephen P. and Vincent J. Del Casino, Jr. 2003. "Introduction: Tourism Spaces, Mapped Representations, and the Practices of Identity," ix-xxvii. In Mapping Tourism. Stephen P. Hanna and Vincent J. Del Casino, Jr., editors. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hannam, Kevin and Chris Halewood 2006. "European Viking Themed Festivals: An Expression of Identity." Journal of Heritage Tourism 1(1): 17-31.

Harvey, Clodagh Brennan 1996. "The Heritage Embroglio: Quagmires of Politics, Economics and ‘Tradition’," 43-64. In Keys to the Marketplace: Problems and Issues in Cultural and Heritage Tourism. Patricia Atkinson Wells, editor. Middlesex, UK: Hisarlik Press.

Hobsbawm, E. and T. Ranger (eds.) 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jakle, John A., 1985. The Tourist: Travel in Twentieth-Century North America. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Li, Y. 2000. "Ethnic Tourism — A Canadian Experience." Annals of Tourism Research 27 (1): 115-131.

McCrone, David, Morris, Angela, and Richard Kiely 1995. Scotland — The Brand: The Making of Scottish Heritage. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Mercille, Julien 2005. "Media effects on image: The Case of Tibet." Annals of Tourism Research 32(4): 1039-1055.

Moscardo, Gianna 2000. "Cultural and Heritage Tourism: The Great Debates," 3-17. In Tourism in the Twenty-first Century: Reflections on Experience. Bill Faulkner, Gianna Moscardo, and Eric Laws, editors. London: Continuum.

Nadel-Klein, Jane 2003. Fishing for Heritage: Modernity and Loss along the Scottish Coast. Oxford: Berg.

Nash, Dennison 1981. "Tourism as an Anthropological Subject." Current Anthropology, 22(5): 461-481.

Ooi, Can-Seng 2002. Cultural Tourism and Tourism Cultures: The business of Mediating Experiences in Copenhagen and Singapore. Herndon, VA: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Orams, M.B. 2001. "Types of Ecotourism," 23-36. In The Encyclopedia of Ecotourism. David B. Weaver, editor. Cambridge, MA: CABI Publishing.

Overton, James 1979. "Towards a Critical Analysis of Neo-Nationalism in Newfoundland, 219-49." In Underdevelopment and Social Movements in Atlantic Canada. Robert J. Brym and R. James Sacouman, editors. Toronto: New Hogtown Press.

Overton, James 1996. Making a World of Difference: Essays on Tourism, Culture and Development in Newfoundland. St. John’s: Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Palmer, Craig T. 1995a. The Boats From Home: Fish Smacking Tactics and the Management of the Labrador Fishery. Research and Policy Paper, no. 17. Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Palmer, Craig T. 1995b. "Growing Female Roots in Patrilocal Soil: Cod Traps, Fishplants, and Changing Attitudes towards Women’s Property Rights," 150-163. In Living on the Edge: The Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland. Lawrence F. Felt and Peter R. Sinclair, editors. St. John’s: Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Palmer, Craig T. 1995c. "The Troubled Fishery: Conflicts, Decisions, and Fishery Policy," 57-76. In Living on the Edge: The Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland. Lawrence F. Felt and Peter R. Sinclair, editors. St. John’s: Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Palmer, Craig T. 2003. "A Decade of Uncertainty and Tenacity in Northwest Newfoundland," 43-64. In Retrenchment and Regeneration in Rural Newfoundland. Reginald Byron, editor. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Palmer, Craig T. and Peter R. Sinclair 1997. When The Fish Are Gone: Ecological Disaster and Fishers in Northwest Newfoundland. Halifax: Fernwood Press.

Palmer, Craig T. and Peter R. Sinclair 2000. "Expecting to Leave: Attitudes to Migration among High School Students on the Great Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland." Newfoundland Studies 16(1): 30-46.

Pearce, Philip, Benckendorff, Pierre and Suzanne Johnstone. 2000. "Tourist Attractions: Evolution, Analysis and Prospects," 110-129. In Tourism in the Twenty-first Century: Reflections on Experience. Bill Faulkner, Gianna Moscardo, and Eric Laws, editors. London: Continuum.

Poria, Yaniv, Butler, Richard and David Airey 2001." Clarifying Heritage Tourism." Annals of Tourism Research, 28(4):1047-1049.

Reisinger, Y. and C. Steiner 2006. "Reconceptualizing Object Authenticity." Annals of Tourism Research, 33: 65-86.

Rothman, Hal, K. (editor) 2003. The Culture of Tourism, the Tourism of Culture: Selling the Past to the Present in the American Southwest. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Smith, Valene L. 1977/1989. Hosts and Guests: the Anthropology of Tourism, second edition. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Steiner, Carol J. and Yvette Reisinger. 2006. "Understanding existential authenticity." Annals of Tourism Research, 33(2): 299-318.

Timothy, J. Dallen and Stephen W. Boyd. 2006. "Heritage Tourism in the 21st Century: Valued Traditions and New Perspectives." Journal of Heritage Tourism, 1(1): 1-16.

van den Berghe, Pierre 1994. The Quest for the Other: Ethnic Tourism in San Cristobal, Mexico. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Waitt, Gordon 2000. "Consuming Heritage: Perceived Historical Authenticity." Annals of Tourism Research, 27(4): 835-862.

Wang, N. 1998. "Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Research." Annals of Tourism Research, 26: 349-370.

Weiler, Betty, and Colin Michael Hall, editors. 1992. Special Interest Tourism. London: Belhaven.

Wells, Patricia Atkinson 1999. "Introduction," vii-x. In Keys to the Marketplace: Problems and Issues in Cultural and Heritage Tourism. Patricia Atkinson Wells, editor. Middlesex: Hisarlik Press.

Yale, Pat 1991. From Tourist Attractions to Heritage Tourism. Huntingdon: ELM Publications.