Articles

"It was a woman’s job, I ’spose, pickin’ dirt outa berries":

Negotiating Gender, Work, and Wages at Job Brothers, 1940-1950

Linda CullumMemorial University

lcullum@mun.ca

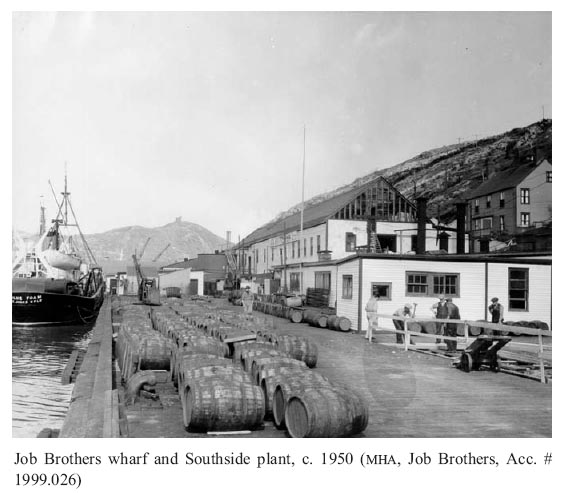

1 BLUEBERRY PROCESSING AND EXPORT has been considered a minor activity in the economic life of Newfoundland and Labrador, yet this production supplied seasonal employment and income for significant numbers of women and men as pickers or processing labour in fish plants. While considerable attention has been given to the history of labour and economic development in Newfoundland (less on Labrador) in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most has focused on fishers, technology, merchants and business operations, and the truck system. Post-World War II attempts to diversify and industrialize the economy, and produce "new" workers for the emerging industrial processes in Newfoundland in particular, have been explored as well.1 In the last twenty years, historians have examined the history of St. John’s female workers and their employment,2 and Jessie Chisholm has made a considerable contribution to our understanding of male waterfront dock labour connected to fish plants in St. John’s, especially in relation to work and the constitution of masculinity.3 Fewer scholars have considered the traditions, workers, and work processes involved in industrialized processing operations.4 The lesser-known business and seasonal organizational routines of fish processors, such as the fall production of blueberries for export to the United States after World War II, have not been addressed; nor have the social relations produced in the intersection of female and male work forces in these operations been sufficiently analysed. This essay explores the industrialized processing of blueberries at Job Brothers and Company fish and blueberry processing plant on the Southside Road in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

2 Job Brothers, along with other plants in St. John’s, processed berries in the fall. They employed women as the primary labour in processing, and male waterfront workers handled the "physical" tasks of moving the berries on the wharf and in the plant. This gendered division of labour at Job’s and the everyday practices that shaped this division, embodied contested meanings of femininity and masculinity produced in, and through, workplace hiring procedures, and workers’ talk about work and work processes. This essay examines worker negotiation of these practices, the meaning-making and definitions of "real" work, and the material reality of a consistently unequal wage structure for women and men as negotiated by the unions. Such gendered processes were not unique to Job Brothers in the postwar era. An industry and site-specific historical approach5 to examining sex segregation allows us to understand more about these everyday practices and the individual and collective negotiations of workers and management in the fashioning of such a workplace and definitions of "real" work.

THINKING ABOUT BLUEBERRIES

3 The humble blueberry has received scant attention in most fields of scholarly research and publication. In general, historical and geographical analysis of fish plant work in Newfoundland and Labrador has focussed on fish processing, rather than blueberry production and export.6 Discussion of berries tends to appear in the scholarly examination of local foodways and residents’ subsistence strategies. Folklorists Everett and Pocius, for example, both discuss berry picking and use in the context of community life in the late twentieth century. Pocius notes that blueberries were second only to bakeapples in popularity in Calvert where community members used them for wine, jams, and pies. Everett explores the forms of knowledge and identity construction produced in and through linkages between traditional food, culinary tourism, and social class. Part of this discussion focuses on traditional and commercial uses of many kinds of wild berries, rather than on blueberries in particular. Anthropologist John Omohundro examines the seasonal round of subsistence activities in Main Brook, Newfoundland, noting the role and timing of wild fruit collection on the Northern Peninsula in the early 1990s.7 In discussions of tourism, only limited analysis has been done on the widely popular berry-related festivals in contemporary Newfoundland and Labrador.8 In a discussion of the blueberry industry, sociologist James Overton provides a brief but interesting account of civil unrest and strike actions within the berry industry in the 1930s. With particular reference to the forced berry picking by those cut off the dole and the struggle for decent wages for such work, he argues that berry picking and poverty are sometimes linked, not only in the Depression years, but also during lean years in the fishery, when berries have been exchanged for clothing in some communities, and unemployment insurance denied some berry pickers.9 More numerous are economic analyses, such as those found in the Newfoundland Journal of Commerce, and blueberry production and industry development concerns were addressed in agriculture reports from 1949 to 1966.10 Reports of harvest yields, prices, technological developments, and conflict in the industry appear in daily papers,11 and local historical accounts of daily life in Newfoundland and Labrador often contain details of berry picking and cooking, since these were and are popular activities.12

4 In this essay, I draw on some of this diverse research to flesh out the story of blueberries from the fields to the processing plant. At the heart of this essay, however, are the stories of working-class women and men employed as fish and/or blueberry processors at Job Brothers between the late 1930s and 1967, when the plant was closed. Thirty-three women and men, including three married couples, all aged 63 to 85, contributed their narratives about Job’s, their work, and their domestic lives.13 Archival records and documentary sources form another fertile layer in this project. Particularly valuable are the union records — minutes, roll, and dues books — of the Ladies’ Cold Storage Workers Union (LCSWU) and the Longshoremen’s Protective Union (LSPU). The business records of Job Brothers and Company provide insights into the company’s organizational practices in the 1940s and 1950s; records of the Newfoundland Board of Trade and the Newfoundland Employers Association Limited (NEAL) illuminate union contract negotiations; business journals and daily newspaper reports provide rich detail about the blueberry industry as a whole. By reading these multiple texts over and against each other — what Britzman calls reading "the absent against the present"14 — it is possible to provide a rich and complex picture of workers’ lives.

SOUTHSIDE ROAD:JOB BROTHERS AND COMPANY

5 For much of the twentieth century, the Southside Road along the St. John’s waterfront was a site of intense industrial activity. Fish and seal processing, processed food items, and the transhipment and storage of goods were conducted there. Porter writes, "Mudge’s, Morey’s, Wyatt’s, Hickman’s, Cashin’s, Baine Johnston’s, Bowring’s, Job’s, they were all independent operations where salt, coal, fish, foodstuffs and, in the spring, seal meat and flippers, were unloaded."15 Some of these operations long stood on Southside Road; the Job family conducted business on their Southside site for nearly 250 years. They became part of the social, economic, and political life of Newfoundland and Labrador in the 1780s when young John Job became the ward of Devonshire merchant Samuel Bulley. The Bulley family operated business concerns in Newfoundland from the 1730s, when John Bulley purchased the parcel of land on the south side of St. John’s harbour known as Prosser’s Plantation. By the twentieth century, the Job family maintained interests in a wide range of industries in Newfoundland and Labrador, from mineral exploration to steamship and fisheries investments to the manufacture of foodstuffs.16

Job Brothers wharf and Southside plant, c. 1950 (MHA, Job Brothers, Acc. # 1999.026)

Display large image of Figure 1

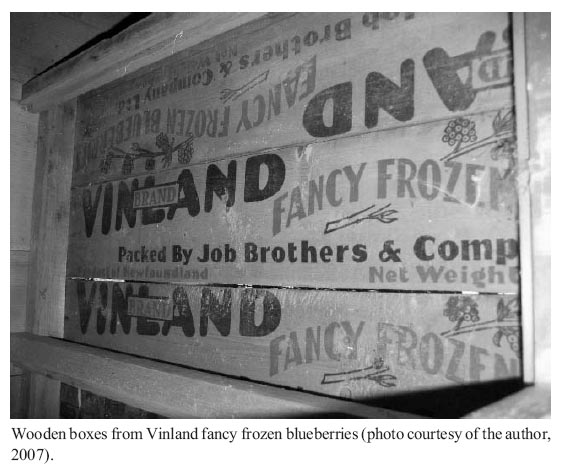

6 The Job Brothers processing plant was situated near Prosser’s Plantation. It employed both women and men, whose work and numbers changed with developments in the fishery and Job’s business interests. From the early decades of the twentieth century, production depended on the seasonal processing round of seals, fish of various species, and, in the fall, blueberries. The fishery had long standing seasonal and gendered divisions of labour, which were replicated within the blueberry industry. Spring seal processing — the flaying (skinning), scrapping, salting, piling, and packing of seal skins for the production of skins and oil — was the work of men. Then small-boat inshore fishermen from the St. John’s area, as well as large banking schooners operated by other merchants such as W.W. Wareham or Munroe’s, supplied Job Brothers from June to October with fish.17 The introduction of side-trawlers and other deep-sea fishing technologies in the 1930s and 1940s meant species such as haddock, halibut, flounder, rosefish, herring, and perch were caught in greater numbers. Job Brothers marketed fish products under a number of brand names: Hubay and Labdor brine frozen salmon, Hubay quick-frozen fillets, Flag brand smelts. They handled dried codfish, cod oil, seal oil, seal skins, pickled herring and salmon, canned lobsters and salmon, and fresh, frozen, and smoked fish. Job Brothers marketed their blueberries in the United States under the name Vineland Fancy Frozen Blueberries.18 New processing technologies such as integrated conveyor belts and modern freezing techniques for fish and blueberries resulted in new production and work processes. These transformations significantly altered the seasonal flow of work and unemployment for women and men at Job Brothers. Blueberries, part of the fall production flow at Job’s, continued with few changes until the introduction of mechanical berry pickers in the 1950s.

7 The Southside plant drew workers from distinctly working-class neighbourhoods: Fort Amherst in the Narrows of the harbour entrance, the Southside Road near the plant, Shea Heights on the top of the Southside Hills, and the downtown area on the north side of the harbour. Nearly half of Job’s employees were female — single, married, or widowed women, ranging in age from early teens to middle age. They worked as weighers, packers, and wrappers of fish and blueberries. Their male relatives also worked at Job’s as filleters, wharf men, general plant labour, and foremen. Many of the women were related to each other as well: mothers worked alongside daughters, sisters next to cousins. Their numbers swelled in the summer, when the company hired school-aged girls and other local women — in essence a reserve army of labour — to handle the inevitable glut of fish arriving at the plant.

8 Fish and blueberry processing were divided by gender and segregated into separate occupational spaces. Men, members of the LSPU, had won the right to perform what was considered the heavier physical labour of loading and off-loading boats, storing products in the freezers, using mechanical equipment and tools in their work, and doing plant maintenance. Men also worked as filleters or cutters, the highest paid and most respected job in the fish processing line. Their work with berries mirrored the physical labour they did in fish processing. They did most of this work on the main floor of the plant, but performed some outside on the wharf, in all weathers, or inside, in the freezing storage areas. Power, drawing on Rowe’s work, notes that men’s jobs in fish plants were associated with masculinity, and were "literally closer to water or outside the boundaries of the factory walls" than women’s.19 This seems true of Job’s practices too.

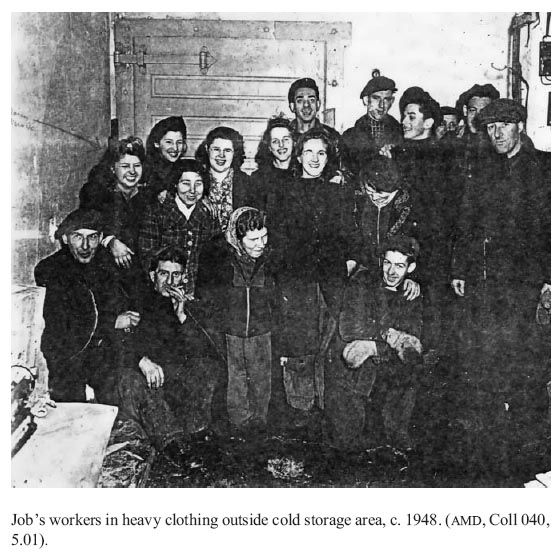

9 Management assigned women repetitive jobs inside the plant: weighing, trimming, wrapping, and packing fish, and blueberry cleaning and packing.20 They believed these required little or no training or skill, and thus were lower paid. The fish work was done on the second floor of the plant.21 Blueberry processing, also considered unskilled, was confined to a section of the plant outside the cold storage area on the main floor. A small female workforce drawn from the fish processing line cleaned, packed, and wrapped the blueberries. The women on the blueberry line ranged widely in age and experience. Veteran workers laboured alongside newcomers, some of whom were as young as 12 years.22 Newspaper accounts of the day described women’s work in Job’s plant as "clean and light," with the women maintaining an appearance "equal to that of any good cook in a spotless kitchen."23 The domestic reference underscores the perception of women’s work as an extension of the household, and thus, requiring little skill or training.

10 This gender division of labour is consistent with other factory work. Glucksmann notes that British industrialists recruited women specifically for work on conveyor belt operations in food production prior to World War II. She examines food processing industries such as jam making, fruit preserving, and canning, and argues that, with the advent of mass consumer production, women assumed a new and heightened significance within the industrial workforce. Employers deliberately recruited them to operate the assembly lines and conveyor belts used for mass production.24 These jobs showed a clear division of labour based on sex category and gender ideologies, and established what people thought constituted appropriate work for women and men. Glucksmann found that, work sex-typed as feminine was routine and repetitive. It was portrayed as clean and light, requiring no training or formal skill, but rather as depending on dexterity, concentration and the ability to tolerate monotony. All jobs that were presented as heavy and dirty or as necessitating formal training, manual skills or technical knowledge were ipso facto ‘men’s work’. Since people were allocated to jobs on the basis of gender, the workforce was inevitably divided on the basis of gender.25 Glucksmann’s portrait of work in England accurately describes the division of labour in the Job Brothers processing plant in the 1940s and 1950s. Both management and workers considered this division of labour to be "natural" and proper, in part based on traditions of household production where women prepared food, the idea of "lighter" or "easier," less skilled work as a marker of women’s jobs and thus distinguishing them from men’s jobs,26 and notions of masculinity and femininity which constructed work differently for each sex. But blueberry processing at Job Brothers required delivering berries to the conveyor belt, a task that straddled the "male" physically demanding work with the "female"food processing role. The development of this industry is a relatively recent one, and it reveals a struggle for fair wages among women.

PICKING BERRIES

11 In Newfoundland, berry picking for sale has a particular history. As Overton observes, berry picking is hard work and in the past, especially during the 1930s, working people in Newfoundland often did it to provide food or much needed cash for families.27 In some areas of the island few berries were sold, but were picked for use in the home as jam, pies, puddings, or wine.28 Early in the twentieth century, fish processors and local merchants sent their agents into different parts of the island to purchase gallons of blueberries and partridgeberries from local pickers. Although women usually performed or directed berry-picking work, male family members and children also contributed labour if family conditions warranted.29 Aubrey Tizzard of Notre Dame Bay notes that his "grandfather, father and two half brothers" picked the family’s berries the fall he was born as his mother could not get out on the berry grounds due to pregnancy.30 Hilda Murray of Elliston, Bonavista Bay describes a different gendered social organization of berry picking. Women went to the berry barrens in "groups of twos or threes ... sometimes taking along smaller children who picked berries as well." Men went alone or with the older boys in the family, and travelled further afield, over more difficult terrain. Girls went berry picking in same-sex groups of four or five, while boys "tended to be more solitary and ranged further afield." Mixed sex groups usually picked together when they went as a family group.31

12 Berry pickers might be paid in cash or a berry note. The berry note was a buyer’s receipt issued to the picker, which detailed the quantity of berries purchased from the picker, the amount shipped, and the current price per gallon.32 This note was later used to purchase goods at the issuing store. A good season’s picking, with many family members participating, might provide sufficient credit to supply the family with important food items and clothing for winter. Abbie Ellis-Whiffen writes of her experiences with berry picking in the 1930s, noting that, [I]n late August we would go blueberry picking which meant taking a lunch and walking about three miles. I remember picking a gallon and a half. The price offered was 10 cents cash and 12 cents credit per gallon. We used to sell ours at the merchant’s on the way home, take the credit, and get the cash when we got home.33 Whiffen’s "12 cents credit per gallon," points to the use of berry notes rather than cash in hand, and the local merchant’s use of slightly higher prices per gallon to encourage pickers to take credit rather than cash payments for their berries. However, berry money fluctuated drastically from year to year, with no guarantee that this year would pay the same as the previous one.

13 Whether as berry notes or cash, annual and regional variation in prices paid for berries created inequities, and on occasion were grounds for civil disputes and confrontations with the law. Overton reports that in the early 1930s pickers received only eight to ten cents a gallon for berries in the Bonavista area. By the late 1930s, newspaper accounts describe berry pickers on strike for better pay per gallon — then up to about 18 cents. Police were called in to restore order in other areas, arresting strikers around Clarke’s Beach. In 1952, pickers in the Bonavista area received about 50 cents per gallon, with the average person picking five to eight gallons per day. But in 1954, Bonavista Cold Storage paid 50 cents a gallon as opposed to 60 cents a gallon a year earlier. Job Brothers purchased berries from the Avalon Peninsula, primarily around Portugal Cove and Bay Bulls. Here too, prices paid varied considerably. In 1954, Job’s paid pickers 40 cents a gallon, whereas the average for 1953 was 70 cents a gallon.34

14 New technologies influenced berry prices as well. Business owners introduced mechanical berry pickers in the early 1950s in the Avondale, Roache’s Line, and Carbonear areas. Pickers could collect 25 to 40 gallons a day with the introduction of this new technology. Processors, however, paid only 50 cents a gallon. Still for those with access to the new methods, more money could be made at berries. Overton notes that an estimated 60,000 to 70,000, five-gallon boxes of berries, both fresh and frozen, were exported from Newfoundland at this time. Up to 1950, nearly 95 per cent of Newfoundland blueberries were processed as frozen product, with the bulk of this marketed in the United States.35

BLUEBERRY PROCESSING AT JOB’S

15 When Ernest Eaton, a specialist in blueberry and cranberry production at the Dominion Experimental Station in Kentville, Nova Scotia, visited Newfoundland in the fall of 1949, he noted that four fish processing firms operated a total of 14 quick-freeze plants for fish and berries in Newfoundland. Eaton described these plants as "among the most modern in the world."36 Using this technology, Job Brothers shifted some processing capacity to blueberries during a fall confluence of events: berries were available, there was a lull in fish catching, and women workers could be spared from the fish processing line.

16 For several reasons, blueberry export seldom made a profit for Job’s.37 Company records cite poor blueberry crops and the lack of pickers as reasons for the poor economic showing in blueberry sales during the war years.38 In the early 1950s, a local journal cited poor markets as depressing prices paid for berries, despite an excellent berry harvest. Nova Scotia, Quebec, and other parts of mainland Canada also had good, sometimes earlier, crops of blueberries, and competition for the American marketplace meant a lower demand for Newfoundland blueberries.39 Nevertheless, in one year, Job Brothers shipped 64,000 boxes of the berries to markets in the United States and England.40 Various products, including pies, jams, and dyes were made from the blueberries, and berries were sold directly to restaurants and supermarkets.41

17 Representatives of the company collected from outports and deeply chilled berries for delivery to Job’s plant by Job’s vessel, the Blue Peter.42 Chilling ensured less damage to the berries and easier handling in the cleaning process.43 At Job’s wharf, men moved the filled berry boxes into the plant. Two women, working together, loaded the cold berries from the boxes into the hopper (or sifter as the women called it), a wire mesh revolving drum which sifted and separated the berries, leaves, and stems, and fed the chilled blueberries to be spread on a conveyor belt.44 Other women further separated, cleaned, culled, and packed the berries in lined boxes or cartons, placed "hot wrap" of cellophane around the packages and made them ready for storage, by men, in wooden boxes in the cold storage room.

Wooden boxes from Vinland fancy frozen blueberries (photo courtesy of the author, 2007).

Display large image of Figure 2

18 "Working at the berries," as the women phrased it, meant standing in frosty air, for eight hours a day on low wooden stools beside the berry conveyor belt, a line of "girls" on each side using bare hands to pick out rotten, crushed, or green berries, and twigs, leaves, and dirt of all kinds from the passing line. The women were given breaks for lunch or to use the bathroom, but in general, the rhythm of work was one hour in the cold on the berry line, and fifteen minutes outside the cold storage area to warm up.45 The women wore their own extra heavy winter coats and headscarves, with additional scarves around their necks to fend off the cold.They brought their own rubber boots from home to keep their feet dry, because the floor was constantly washed down with cold water.46 This was rather different treatment than that given to LSPU men: from 1948 onwards, the company provided LSPU men working "in the frost" with suitable coats and mitts by the employer. There is no mention of women receiving the same consideration despite their work in the cold areas of the plant.47

Job’s workers in heavy clothing outside cold storage area, c. 1948. (AMD, Coll 040, 5.01)

Display large image of Figure 3

19 Job’s management assigned only five or six women to do the berry processing work each year.48 Ann remembers that, that was very hard work. Nobody liked to goin’ to the blueberries, so it was me and Donna and my sister-in-law [Phyllis] and her sister and couple from the Battery used to go in ... they just picked so many of us out of the fish plant to go out into it and they’d pick the same girls every year, you know. ’Cause the rest of the girls didn’t want to do it!49 These women did not see berry processing as a good job, or one that paid well, but they took pride in accomplishing the heavy, repetitive tasks, and working co-operatively in the company of other women. While some of the women worked on the berry line for brief spells, perhaps one or two fall periods, others worked at the berries every fall, shifting from their place in the fish weighing and packing lines to do so. Phyllis was just 12 years old when she started working on the berry line, despite struggling to reach the conveyor belt to do her work. One of the foremen teasingly suggested he would have to "get a block and tackle, stretch ya," so she could reach the berries.50 Julia, aged 14 when she began at Job’s, wanted very much to work on the berry line, but was never chosen to do the work.51

20 Other women responded differently to the prospect of berry work. Ellen, who worked at Job’s from the early 1940s to the early 1960s, refused berry work because she saw it as beneath her, describing the other women who did this work as "a rough crowd ... from the Battery and places like that." She linked her departure from another processing plant, Harvey’s, on the north side of the harbour, to the fact they processed blueberries. She firmly stated, "I wouldn’t work at the berries ... didn’t want to go pickin’ no berries ... don’t want to work at it." Ellen, the daughter of a small merchant from the north side of the harbour, considered this work unsuitable for her because people working on the berries were "not my company."52 Class relations and sensibilities, along with gender ideologies, shaped women’s reactions to the production line.

21 Ann’s cousin, Donna, remembers the berry work as demanding physical labour, performed in cold, frosty conditions, especially when loading frozen berries into the hopper.53 Donna is clear about it being co-operative work with women changing work positions to relieve other workers of the heavier tasks. they had a big sifter and one [girl] had to stand up high, you know, cause the sifter was on an angle, and there’d be a girl underneath and a girl on top ... we used to change around, an hour for hour ... the girl on the bottom would put her hand in through and scoop out the frozen berries, put ’em up to this other girl and she’d throw ’em in the sifter. Then they’d come down on a conveyor belt and there was so many girls on each side of the belt and they were pickin’ out bad berries ... you know, unripe berries and dirt....54 Donna points to a co-operative work process on the berry sifter where moving freezing berries into the sifter for the initial cleaning was strenuous and exhausting work. So, the women shifted work roles, relieving the strain on their bodies and other women, actively negotiating the conditions of their labour in the workplace. By working at a specific pace of 50 buckets of blueberries per hour, no more, no less, women workers asserted some control over the speed of the line and kept their daily work pace manageable. This informal arrangement negotiated among the women working on the berry line, and with management at Job Brothers, meant that the women actively participated with management in the co-regulation of production flow. Dumping more than 50 buckets per hour into the sifter and onto the conveyor belt provoked protests from co-workers; dumping less could incur the disapproval of management.55

22 Margaret who worked on the fish trimming and packing lines and for two years on the berry processing line, found berry work cold and tiring, but experienced some small pleasures, such as tasting the berries as they passed by on the conveyor. She remembered one of the foremen conveyed through humour his close supervision over the berry workers. Mr. Brown used to be there right and he’d be watching (laughs). He’d be watchin’ cause every now and again you’d pick a great big blueberry comin’ along, and he’d say ‘Ah-ah, for the box’ (laughs). He was a queer hand right. ‘Don’t eat the berries, you’re eatin’ our profit!’ 56 Despite such amusing moments, working conditions on the berry line were hazardous. Ann raised the health and safety concerns the women faced, especially the dangers of stepping from your stool onto the slippery floor around the conveyor belt.57 Margaret also remembers "the blueberries were slimy ... if somethin’ got on the floor ... down in the frost. Every time you opened the freezer [cold storage doors], thefrost’d [flow out over the floor]."58 The women also had to contend with the uncertain footing of standing on small wooden stools in order to reach the conveyor belt.

23 A woman’s physical condition might be used by Job’s management to justify her exclusion from the berry line as well. Hannah remembers management opposition to her supervising berry line work: "Samuel Thompson [plant manager] didn’t want me to do work over there because I was pregnant, ’fraid I might fall or something."59 Donna described pregnancy, in particular, as a health concern for plant management saying, Oh, forget it ... if you were pregnant ... and you needed your work; you dare not tell them you were pregnant. You hid it as long as you could. Yeah, because soon as they found out you were pregnant, and it was dangerous, the floors’d be slippery or something, you had to give up work.60 The unsafe and unhealthy working conditions in and around the blueberry processing line were witnessed by workers and managers alike, and could be used to restrict or curtail altogether women’s paid labour at the plant. There was no maternity leave for women in the 1940s, and many of Job’s workers could not afford to give up work.

24 The term "corporate patriarchy" might be used to describe the structure at Job’s: the gender segregation of labour, with poor wages and less secure jobs attached to women’s work, buttressed by gendered ideologies and practices of employers, unions, and male workers. Neis notes an intersection of ideologies in this time period: "corporate-owned fish plants in some communities also strengthened familial patriarchy in the early 1950s." Thus, she suggests, patriarchal norms establishing men’s power and authority over women were linked to gender ideologies, structures, work, and wages in plants.61 The blueberry sector may have had such effects as well.

TALKING ABOUT WORK,CONSTRUCTING GENDER

25 The women, their male relatives and co-workers, and Job Brothers management believed working at the berries was appropriate women’s work. This was particularly evident in the conversations with married couples, where intensely gendered debate and negotiation of ideas about what constituted "proper" femininity and masculinity, appropriate expressions of class, especially at the intersection of masculinity and class, and the meaning of "real" work, took place. Phyllis and Carl, a couple who met over the berry line, for example, held very different views of the work of berry processing. Carl, an LSPU man who processed fish and seals and loaded coal at Job’s, described cleaning the berries as "unskilled work," that "anybody could do."62 It required no particular training; whoever was "there first told ya what to do," so women would "just go in and go to work" according to Phyllis.63 Even the managers treated women’s work as unskilled, as Phyllis noted of one boss: "he’d say, now ya knows what ya gotta do, so go ahead and do it."64 Carl suggested women, including his wife Phyllis, were less valued labour because they required no skill or training to accomplish the tasks on the berry line. It was expected that women knew how to do the work, since cleaning berries is work that has long been done by women within households. Phyllis herself linked domesticity and women’s work to make clear this gender division of labour in paid work outside the home. She suggested that "it was a woman’s job I ’spose, pickin’ dirt outta berries ... it wasn’t too hard," and was work similar to that performed in the household, "cleaning your berries."65 Thus, in this gendered assignment of work roles in the plant, the division of labour follows that of the home — women perform the preparation and cleaning work.

26 Carl stressed that men would not do berry work because it was not "physical" labour, and wages were not as high as in men’s jobs, a result of women’s work being classified as unskilled. Definitions of masculinity, and by implication, femininity, begin to emerge in conversation between Phyllis and Carl. C: I imagine the men wouldn’t do it.

P: That’s cause they’re m-e-n!.... They were men!

C: It wasn’t, uh, physical.... [And the pay wasn’t as good?] That’s right.... When you’re workin’ on the shore years ago, you had to be strong or else you didn’t get by with a lot of it.66

Here, men’s work and women’s work are placed in opposition. Carl equates strength, and active, physical labour with masculinity and working in the longshore. Then he links longshore work with the idea of strength in saying "you had to be strong," and have the capacity to handle the work required of you as a man, working as a longshoreman. In this linking, berry work becomes a job that a member of the LSPU would not perform, nor would he be asked to do the work. It is, as Phyllis put it, not a job for "m-e-n." Physical capacity is a key explanation in this gendering process; it is constituted as working long hours, lifting substantial loads, and on-going bodily activity. Although women’s work at the berries does contain tasks that fit within these boundaries of "real" labour, Carl does not not acknowledge these tasks. Bodily labour, such as lifting heavy buckets of berries over your head, or standing for hours by the conveyor belt, are not constituted as requiring strength or endurance. Here, intersecting ideologies of gender and "real" work operate to exclude women’s work on the berry line. This gendered constitution of specific labour and work processes has an intergenerational constituent as well. Another longshoreman, Charlie, worked at many jobs in the plant, from culling boy, to foreman of discharging vessels on the wharf. He remembers well his father’s wishes: as foreman over the cold storage area, Charlie’s father did not want him working there, and clearly instructed Charlie not to accept berry cleaning employment.67 Through the influence of the father, the boundaries of gender ideologies and divisions were instilled in a new generation.

27 These concepts of masculinity are in keeping with long standing assertions by LSPU members and their representatives that their work demanded, and was defined by, a very particular expression of masculinity that included definitions of skill, knowledge, strength, and stamina. Indeed, testimony, contained in the 1935-36 Royal Commission of Enquiry Investigating the Sea Fisheries, describes long hours and endurance as a specific discourse of masculinity required in longshore work. Michael Coady, President of the LSPU in the late 1930s, asserted the importance of strength and endurance in being seen as a productive worker and a good LSPU man. As he testified, "[A] Newfoundlander or a fisherman can easily stand two nights work without sleep and can work steadily. Very often I have lost two nights sleep working and felt nothing the worse for it." Later in his testimony in response to a question about the long hours of work for longshoremen, Coady replied, "[I]f a man can’t stand a few nights and a couple of days [of steady working], he is no good."68 Both Coady and Carl articulated ideologies of gender commonly expressed by LSPU members.

28 Not all expressions or practices of masculinity are equally acceptable. Class and masculinity intersected and were negotiated in various ways in and around the plant. At Job’s in the late 1940s, relations between male managers and LSPU men were riven with competing concepts of masculinity, with implications for those not meeting the hegemonic, and most valued criteria. Lloyd, who made salt fish and worked on Job’s vessels, mentioned one instance in which a manager’s inability to solve a household plumbing problem showed him as deficient in masculinity. Plant manager Sam Thompson turned to his wife for assistance, and then resorted to calling one of the LSPU men to come to his home, to find and turn off a leaking water valve. Lloyd recounted his exchange with the plant manager. This conversation, conducted on the wharf, in a distinctly male setting — "all the boys were there" — allowed Lloyd’s own skill, knowledge, and production of the valued hegemonic masculinity to be recognized and validated by other men. As Power suggests, "masculinities are complex and plural, mediated by the social positions that men fill."69 Class relations intersected with the production of masculinity. In this case, Lloyd, a working-class LSPU man, using concepts of appropriate class and gender behaviour, measured upper-middle class Thompson against other men, and found him wanting.70

THE GENDERED MEANINGS OF COLD STORAGE WORK

29 Masculinity and femininity were constituted in and through the physical environment of the plant. On the berry line, the work was cold and damp, as the line was located just outside the freezers in the cold storage area. The rhythm of the work — an hour in the cold storage area, 15 minutes outside in the relative heat of the plant to warm up, and then back into the cold storage area for another hour of berry cleaning — created its own problems. The women would often perspire from the extra layers of clothes and the heat of the plant outside the cold storage area, and then they had to return to the cold and damp. Many women workers attributed their present health issues, such as recurring arthritis, to this cold work.

30 The geographic location of the berry line became a site of the constitution of femininity and masculinity in the following excerpt from the conversation between Phyllis and Carl. P: In the cold storage I lined boxes, picked the dirt out of the berries, stuff like that.

C: Although you worked packin’ for cold storage....

P: We were packin’ for the cold storage.

C: … but you wasn’t in the cold storage.

P: No, no. The men were in the cold storage, only so many.

C: But now when it come to the berries....

P: ... we were in cold storage.

C: No, [women] were doin’ cold storage work ... getting’ money for cold storage ... but they weren’t actually in it.

P: Though in the chill room was very cold.71

Here, Carl differentiated between men’s work and women’s work in the berry operation. Men worked "inside" the cold storage area, while women worked "outside," and by implication did not properly earn cold storage wages. The chill room was about -10 or -12 degrees Fahrenheit, while some of the cold storage areas, the "sharps," could go to -45 degrees Fahrenheit.72 Thus, the women’s work area was less cold than other areas, undercutting women’s contention that their work was arduous because of low temperatures and difficult physical working conditions. The implication of this differentiation is that men were expected to, and did, work under greater hardship than women. Carl described his work in the cold storage area: Now, there was me in the cold storage ... open the boxes as they came in and put them out of the cold for the machine. Then on the other end of the machine there’d be another room ... with men in there, and the berries that come in, come in to the boxes. We used to take the boxes out, put the paper down inside them and put the cover ... nail their covers on. And then, when the boxes covers nailed on there’d be a couple of more guys ... puttin’ the metal straps round with the machine and puttin’ two boxes of blueberries together. And they stuck ’em together. So that’s the way they’d go out then, two boxes together.73

Carl was adamant that women could not do this work. No! No, no because, like.... Ya had maybe ten or eight piles, storing’ up boxes. And ya had ta be quite strong at it ... put it this way, that the young fellas today had to work they’d drop dead ... especially the longshore. They’d never do it.74

Masculine strength and endurance and the physical capacity to work in the coldest conditions inside the cold storage area was required for this job, indeed, to work as a longshoreman at all.75

WE USED TO HAVE SOME FUN

31 Women capitalized on the gendered organization of Job’s workplace. The pace of the berry line, and women’s positions along it, allowed them to talk to each other, have a laugh, and still get their work done. This physical arrangement of work had an effect on some women, helping shape their attitudes towards the berry line work. Phyllis remembered that, You could still talk back and forth to each other. Girl on this end, girl on that end, one here and one there, maybe one there ... [indicating 2 sides of the belt].... Like I say, it, it was good relationship at work, right? It was really good.... I don’t know anybody else [found it monotonous], but I didn’t. I enjoyed it.76 As Cockburn found in her study of women and men working in gender stratified jobs in a mail order warehouse in England, women valued being with other women, "[A]mong your own kind" where "you can talk your own talk, be yourself."77 Women on the berry line valued the company of other women.

32 It was not all hard work on the berry line. Working closely together with other women meant time to plan other sorts of activities. Phyllis, who was related to both female and male workers in the plant, described with pleasure the cross-gender tricks women played at the end of the run on the berry line. when we worked at the berries we used to love for the end of it right.... End of the berries ... play tricks on the men. Take their hats, nail ’em on the wall, take their shirts, nail ’em on the wall. [laughing] Let ’em get who did it. That was fun, we used to have some fun.78 As one of the younger berry workers, Phyllis also had jokes played on her by one male relative in particular. Yeah, Uncle Dick almost got fired at that (laughs). Well he got me, he strapped me in a box. [I] put my hands up for a berry box and they hauled me on the conveyor, put me in a box and strapped me into it (laughs). The [warning] bell went for 15 minutes and I couldn’t get out.79 Gendered spaces in the plant provided the opportunity for women to talk throughout the day and plan jokes together, producing for some women a comfortable and attractive workplace. Mildred had no other family working at Job’s, but to her "it was a desirable place to work ... I loved it ... Loved to get up and go to work in the morning." At Job’s "you knew everyone," and they were "all friendly."80 She remembered a workplace that was a secure and "steady" place in her life and described many other women in the plant feeling the same about their work.

GENDERED WORK,GENDERED SPACE,GENDEREDWAGES

33 Despite the fun and intimacy of working with women they knew, being able to negotiate the speed of the berry line, and having the opportunity to lighten the workday with humour and jokes, another reality was also present — women’s wages reflected the gendered norms of the plant. Women’s work was consistently lower paid than men’s. In keeping with the idea that blueberry processing and weighing, wrapping and packing work in fish processing was "unskilled" and "women’s work," was the equation of men’s work as skilled, valued and requiring higher wages.

34 Women received lower wages for doing berry and fish processing than LSPU men were paid for the general unskilled labour they performed in the plant. Blueberry work in the early 1940s earned women about ten cents an hour, until they were given a raise of one cent an hour around 1942. At fish processing, women earned 11 cents an hour with a raise bringing them up to 14 cents an hour around the same time, and, as Donna said, "you worked like a slave to get that."81 Historically contingent gender ideologies about appropriate work and reward for either sex supported the unequal structure of work and wages at Job Brothers and other plants.82

35 In Job’s plant, as in other workplaces on the St. John’s waterfront, the LSPU actively pursued improved wages and working conditions for its male members. As Steedman notes of the needle trades, positioning women in lower wage jobs to maintain the dominance of male workers was "shaped and legitimized by the process of collective bargaining." Men provided the union leadership and negotiated the contracts for women workers in that industry. Steedman observes that in the needletrades, "[W]omen remained subjects of the discussion, rarely active participants."83 While LSPU records indicate a level of consultation with women workers at Job Brothers, the LSPU played a significant role in job protectionism for its male members and the gender segregation in blueberry and fish work and wages at Job Brothers.

36 The LSPU was an exclusively-male union, organized in 1903 in St. John’s.84 At its peak, the union had several thousand members, governed many aspects of work on the waterfront, and formed alliances with other unions to present a united front to employers threatening workers’ gains.85 The LSPU was not afraid to strike to achieve their aims, and records show successful actions against employers for better wages, working conditions, gang size, and benefits.86 Indeed, Chisholm notes that dock workers in St. John’s were "the most strike-prone workers in the city."87 They actively protected men’s jobs on the waterfront as well. In one notable moment in 1949, the LSPU resisted the hiring of female workers to label tinned lobster and salmon at Job’s north side premises, insisting LSPU men be hired to perform the work.88 This approach was used in 1920 as well, when the LSPU defended against a rollback in men’s wages for barrowing fish during the work of curing and drying fish. Women and girls also did this work for some smaller employers, but were paid only one-half of men’s wages. The LSPU did not address these lower wages or attempt to assist the female workers, but instead acted to protect the higher wages of male LSPU members.89 This was in keeping with belief in the primacy of male breadwinner wages and the ideology of "separate spheres" for women and men that was widely accepted at the time.90

37 In 1948, these patriarchal norms regarding women’s work and wages extended to the LSPU refusing women waterfront workers membership in the union based on the belief that women’s membership "might cause a bit of trouble." As a former LSPU executive, Ron, suggested, "it woulda never worked, not in the Longshoremen."91 He argued that women could not be members of "our union," because they "wouldn’t understand it ... working conditions and everything else on boats." Thus, women were perceived as limited in their capacity to understand the separate male world of work on the waterfront, because in the words of Ron, "all [women] ever done was fish work."92 This view echoes the devaluing of women’s processing work at Job’s, and points to an unexpressed assumption that men’s work is more complex and important than women’s.

38 The containment of women’s wages within later union-employer agreements did nothing to alter women’s economic subordination to men after WWII. A closer look at the formal labour agreements negotiated between the LSPU and NEAL confirms the gendered inequality of wages for both fish and berry processing work in Job’s plant, and elsewhere on the waterfront, since these agreements covered all sites worked by LSPU men. The Seventh Annual Report of NEAL records that the 1947-48 agreement between it and the LSPU was the first formal labour agreement negotiated between the two parties.93 While the women workers were not yet organized, the Ladies Cold Storage Workers Union was formed in Spring 1948, the LSPU included them in this first labour contract. LSPU Minutes record they negotiated a raise in women’s wages in this contract — from 25 and 27 cents per hour to 32 and 37 cents per hour for day and night work respectively.94 There is also a significant gendered wage difference for women and men enshrined in this agreement.95 This contract paid male casual in-plant labourers 74 cents an hour for day work, while all women workers, regardless of their job, were paid only half of this rate — 32 cents per hour. For late night work, the same longshoremen were paid $1.00 an hour, and $1.50 per hour for work performed during meal hours and on Sundays; women received 64 cents an hour for Sunday and meal hour work.96 This contract shows no wage rate for women for the late night period, implying that they were not expected to work after 11 p.m. It was not until 1948-49 that a late night wage rate for women appears in contracts. Whenever shifts of work were used in the plant, and workers were guaranteed 48 hours of work in a six-day work week, separate wage rates were in force: in 1947 men were to be paid $37.00, but women only $16.00 for each 48 hour week. In all of these rates of pay, women were held at about one-half the rates of pay for men.97 This first formal agreement set in place a gendered wage structure that was to remain unequal for many years to come.

39 Regrettably, the early records of the Ladies Cold Storage Workers Union are incomplete and the women I interviewed were unable to recall in detail the contract negotiation process. This is not surprising, since the LSPU minutes note the very occasional presence of unnamed women executive, but no other LCSWU members. Thus, we can only speculate about their participation in drafting agreements that left them so far behind LSPU wage rates. In the absence of LCSWU Minute Books for 1948 to 1952, we must rely on the minutes of the LSPU and the limited reference to contracts in records of the LCSWU. References to the LCSWU appear in the LSPU Minutes close to contract time — in April of each year.

40 In April 1948, the relationship between the newly-formed LCSWU98 and the LSPU was raised at an LSPU membership meeting. LSPU President Leo Earle stated there was no "affiliation" with the Ladies Cold Storage Workers Union, but that they had the "moral support" of the LSPU. Earle also reported that the LCSWU had requested the LSPU "to seek an increase in wages for them" for the coming year.99 With this acknowledged inclusion in negotiations, LCSWU per hour wages increased to 39 cents day rate, 44 cents for evening work, and 77 cents for Saturday nights, Sundays and meal hours. Late night period rates — 77 cents per hour — appear for the first time for women. So, while women did gain a raise, they remained confined to half of men’s wages.100 The primacy of men’s work and the significance of men’s wages over women’s are explicitly upheld in the labour negotiations. In and through the narrow, tightly defined, and feminized category "woman," so visible on the printed contract page, women were placed in a subordinate economic and social position by the LSPU and NEAL.

41 In April 1951, the LCSWU is mentioned once again in LSPU Minutes. The President and Treasurer of the LCSWU, who remain unnamed, joined the LSPU Executive for "discussions" regarding the "proposals from the Employers Association, pertaining to Cold Storage Operations under the jurisdiction of the LCW Union." The substance of the "discussions" is unknown, but the minutes note the LSPU was delegated to act as bargaining agent for the LCSWU in negotiations with the Employers Association on wages and working conditions for the coming year.101

42 The LSPU and NEAL negotiated separately for each work area — steamship, coal and salt, fish wharf, cold storage, and seal operations — with different committees of the Employers Association.102 In 1951, the Employers Association offered the fish wharf workers seven cents an hour rather than the nine cents they offered workers in other areas of the plant. The LSPU refused to consider the lower wage rise for the fish wharf men, and recommend "9 cents straight across the board" for all sectors of plant operations. Despite the inclusive language referring to all plant operations, the section of the contract where women are included, cold storage, provides only a six cent an hour increase.103 The LSPU men attending this April 1951 meeting gave their unanimous support for this contract, continuing and reinforcing women’s secondary social and economic status in Job Brothers workplace. Ultimately, while women were actively engaged in everyday negotiations over the boundaries of femininity and masculinity on the plant floor and in conversations about work and wages, ideologies of gender, work, and the specific practices of the Longshoremen’s Protective Union in collaboration with the Employer’s Association constrained women’s capacity to shift their social and economic relations within Job Brothers plant.

CONCLUSION

43 In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Job Brothers and Company’s fish and blueberry processing plant organized work on the basis of gender. Occupational and spatial segregation in the plant reflected and reinforced this gendered organization of labour. Ideologies of gender supported these divisions. Gender-based inequalities between female and male workers were inscribed in a range of everyday practices: through work assigned, wage schedules, male dominated definitions of what constituted "real work" in the plant, and in and through the labour agreements between the LSPU and the Employer’s Association. Unequal wages were consistently structured through collective bargaining, first for the unorganized women workers and, beginning in 1948, for the women members of the Ladies Cold Storage Workers Union.

44 In the face of these structures, at Job Brothers, workers’ memories of blueberry processing are mediated by their relationship to the production line, other workers, and to ideologies of femininity and masculinity. Women recognized and named the work of processing blueberries as cold, tiring, sometimes heavy labour, which they did co-operatively together, regulating the speed of the line through informal means. For their work, they received the lowest wages in the plant. Male workers and management describe women’s berry processing work as "unskilled" and produce definitions of specific work conditions as constituent of femininity and masculinity. Berry work was not men’s work; it was not seen as requiring strength and endurance to perform it well. The implicit opposite to this masculine definition of work is the work of the "other" — women — perceived as unskilled, repetitive, requiring only domestic skills, and thus, deserving low wages.

45 In contrast to this negative valuation of women’s work, is the engagement of women themselves in the daily round of operations at Job Brothers. Women remember well the "fun" of the berry line, where cross-gender jokes and teasing were common occurrences, and humour was used to negotiate gender and familial relations on the plant floor. Many women expressed affectionate feelings about their collective action and solidarity with other women at Job’s. Working with friends and relatives brought an intimacy to the workplace that they did not experience in other jobs in St. John’s.

46 This article demonstrates the usefulness of industry and site-specific historical analyses of everyday interactions, practices, forms of work processes, and conversations. In this way, it is possible to see the on-going construction and negotiation of gender, work, and femininity and masculinity at Job Brothers fish and blueberry processing plant. We may see also that this workplace was not just one kind of experience, fixed and unchanging, routine and monotonous. Rather, the social, economic, and material realities of women’s and men’s lives — the work processes, working conditions, and relations of gender and class — were complex, nuanced, and always under negotiation.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Michelle Park and Susan Williams who shared their interview recordings with me. I also thank the Institute for Social and Economic Research, Memorial University, for providing a post-doctoral book Fellowship. Two anonymous reviewers offered excellent critique on an earlier version of this article. I thank them for their generosity.Archival Sources

Archives and Manuscripts Division, Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland (AMD): Papers of the Ladies’ Cold Storage Workers Union (LCSWU), Collection 040: Roll Books, 1951-1967, 5.01.001 to 5.01.003 Minute Book, 19531971, 5.03.001; Papers of the Longshoremen’s Protective Union (LSPU), Collection 040: Minute Books, 1.04 to 1.16. Roll Books, 1943-1970, 2.11 to 2.36.

Maritime History Archives (MHA): Job Brothers and Company Limited Fonds, Accession # 1999.026; Board of Directors Meeting Minutes, June 1918 to December 1983, Box #1.

Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador (PANL): MG 870, Job and Company Limited, St. John’s. Box 1 -Box 4; MG 310, Job Papers, Merchants, St. John’s and Liverpool. Box 1 -Box 2.GN6, Royal Commission of Enquiry Investigating the Sea Fisheries of Newfoundland and Labrador other than the Seal Fishery, 1935-36, Transcripts of Testimony, Michael Coady; Newfoundland Board of Trade, MG 73, Box 11, File #14; Box 50, file #4 and #7.

Interviews:

Ann. (1992) Taped Interview, 6 June.

________. (1994) Taped Interview, 22 November.

Charlie. (1992) Taped Interview, 26 February,

Donna and Lionel. (1992) Taped Interview, 13 February and 8 June.

________. (1994) Taped Interview, 3 November.

Ellen. (1995) Interview Notes, 2 November.

Hannah. (1995) Interview Notes, 2 October.

John. (1995) Taped Interview, 3 October.

Julia. (1995) Taped Interview, 10 June.

Margaret and Lloyd. (1995) Taped Interview, 19 October.

Mildred. (1995) Taped Interview, 2 November.

Phyllis and Carl. (1992) Taped Interview, 3 June.

Ron. (1994) Taped Interview, 7 December.

References Cited

Badcock, A. (1965) The Blueberry Industry in Newfoundland. St. John’s: Department of Mines, Agriculture, and Resources.

Blueberry Harvest Satisfactory. (1952) Newfoundland Journal of Commerce 19 (9): 15.

Britzman, D. (2000) "The Question of Belief": Writing Poststructural Ethnography." In Working the Ruins: Feminist Poststructural Theory and Methods in Education, ed. E.A. St. Pierre and W.S. Pillow, 27-40, New York: Routledge

Chisholm, J. (2000) "‘To utilize the organized strength of all for the welfare of each’: Dock labour in St. John’s, Newfoundland, 1880-1921." In Dock Workers: International Explorations in Comparative Labour History, 1790-1970, ed., S. Davies, 141-159. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishers.

________. (1988) "‘Hang Her Down’: Strikes in St. John’s, 1890-1914," paper presented to Seventh Atlantic Canada Studies Conference, University of Edinburgh, 1988.

________. (1990) "Organizing on the Waterfront: The St. John’s Longshoremen’s Protective Union (LSPU), 1980-1914," Labour/Le Travail 26 (Fall 1990): 37-59.

Cockburn, C. (1985) Machinery of Dominance: Women, Men and Technical Know-How, London: Pluto Press.

Cullum, L. (2000) "Fashioning Selves and Identities: Contested Narratives, Disputed Subjects." PhD thesis, Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education, OISE/UT, Toronto.

________. (2003) Narratives at Work: Women, Men, Unionization and the Fashioning of Identities. St. John’s: ISER Books.

Daily News. 9 February 1948.

Eaton, E.L. and I.V. Hall. (1961) The Blueberry in the Atlantic Provinces. Ottawa: Research Branch, Canadian Department of Agriculture.

Ellis-Whiffen, A. (1999) "Growing Up — Up in Cove," available from, http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/205/301/ic/cdc/fisheries/whiffen; accessed November 2007.

Everett, H. (2005) "Class Acts: Culinary Tourism in Newfoundland." PhD diss., MUN.

Forestell, N. (1986) "Working Women in St. John’s, the 1920s." In Newfoundland History 1986: Proceedings of the First Newfoundland Historical Society Conference ed. S. Ryan, 219-229. St. John’s: Newfoundland Historical Society.

________. (1987) "Women’s Paid Labour in St. John’s Between the Two World Wars." MA thesis, MUN.

________. (1989) "Times Were Hard: The Pattern of Women’s Paid Labour in St. John’s Between the Two World Wars." Labour/Le Travail 24 (Fall 1989): 147-166.

Forestell, N. and Chisholm, J. (1988) "Working-class Women as Wage Earners in St. John’s, Newfoundland, 1890-1921." In Feminist Research: Prospect and Retrospect, ed., P. Tancred-Sheriff, 141-155. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press Limited.

Glucksmann, M. (1990) Women Assemble: Women Workers and the New Industries in Inter-War Britain. London and New York: Routledge.

Horwood, H. (1997) A Walk in Dreamtime: Growing up in old St. John’s. St. John’s: Killick Press.

Job, R.B. (1961) John Job’s Family: Devon-Newfoundland-Liverpool, 1730-1953. St. John’s: Evening Telegram Printing.

Little, L. (1994) "Women in the Catalina Fish plant," 1985. Unpublished paper, Centre for Newfoundland Studies, MUN.

McInnis, P. (1987) "Newfoundland Labour and World War I: The Emergence of the Newfoundland Industrial Workers’ Association." MA thesis, MUN.

Milkman, R. (1987) Gender at Work: The Dynamics of Job Segregation by Sex During World War II. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Murray, H.C. (1979) More than 50%: Woman’s Life in a Newfoundland Outport, 19001950. St. John’s: Breakwater Books.

Neis, B. (1993) "From ‘Shipped Girls’ to ‘Brides of the State’: The Transition from Familial to Social Patriarchy in the Newfoundland Fishing Industry." Canadian Journal of Regional Science/Revue canadienne des sciences régionales, XVI, 2 (Summer): 185211.

________. (1988) "From Cod Block to Fish Food: The Crisis and Restructuring in the Newfoundland Fishing Industry, 1968-1986." PhD thesis, University of Toronto.

Omohundro, J.T. (1994) Rough Food: The Seasons of Subsistence in Northern Newfoundland. St. John’s: ISER.

Overton, J. (1999) "Picking Berries." Newfoundland Quarterly, XCII, 3, Winter, 1999: 44-45.

Pocius, G. (2000) A Place to Belong: Community Order and Everyday Space in Calvert, Newfoundland. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Porter, H. (1979) Below the Bridge. St. John’s: Breakwater Books.

Power, N.G. (2005) What Do They Call a Fisherman?: Men, Gender, and Restructuring in the Newfoundland Fishery. St. John’s: ISER.

Rodgers, T.H. (2000) "Work, Household Economy and Social Welfare: The Transition from Traditional to Modern Lifestyles in Bonavista, 1930-60." MA thesis, MUN.

Ryan, D.W.S. (1954) "Market Conditions Cause Slump in Sale Local Blueberries." Newfoundland Journal of Commerce, 21 (10), October 1954: 28-29.

Ryan, F. (1976) "A Comparative Study of Three Fresh-Fish Plants of Newfoundland — Bonavista Cold Storage Company Limited, Bonavista; Fishery Products Limited, Catalina; and Arctic Fishery Products Limited, Charleston, Bonavista Bay." Unpublished paper, MUN.

Ryan, S.J. (1954) "Blueberry Harvest On Bonavista Peninsula Not As Good As Last Year." Newfoundland Journal of Commerce, 21 (10), October 1954: 42.

Steedman, M. (1997) Angels of the Workplace: Women and the Construction of Gender Relations in the Canadian Clothing Industry, 1890-1940. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Story, G.M., W.J. Kirwin and J.D.A. Widdowson (eds.) (2002) Dictionary of Newfoundland English, 2nd Edition with Supplement, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Tizzard, A.M. (1984) On Sloping Ground: Reminiscences of Outport Life in Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland. St. John’s: Breakwater Books.

Wall, G.M. (1950) "Blueberries in Newfoundland." The Family Herald and Star Weekly 31 (2), January: 31.

Wright, M. (1995). "Women, Men and the Modern Fishery: Images of Gender in Government Plans for the Canadian Atlantic Fisheries." In Their Lives and Times: Women in Newfoundland and Labrador, A Collage, ed., C. McGrath, B. Neis, M. Porter, 129-143. St. John’s: Killick Press.

________. (2001). A Fishery for Modern Times: The State and the Industrialization of the Newfoundland Fishery, 1934-1968. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Notes