Early Picture Shows at the Fulcrum of Modern and Parochial St. John’s, Newfoundland

Paul S. MooreRyerson University

1 THE RECEPTION OF CINEMA in Newfoundland encapsulates the parochial setting’s confrontation with an emerging mass culture at the turn of the last century. As an electric amusement requiring imported technology and globally distributed films, cinema made explicit an unsettled duality in the role of St. John’s in the colony: metropolitan nexus of commercial and secular modernization, and yet seat of religious and political authority sanctioned to uphold traditional cultural standards. Early picture shows transformed the social scene of leisure and public gathering, demonstrating how St. John’s was squarely part of the continental mass market. The Roman Catholic archdiocese, and to a lesser extent colonial legislators, reacted to early cinema as a symbol of modernization, making efforts to regulate the public’s interest in the novelty pastimes as much as showmen’s provision of the entertainments. In Newfoundland — perhaps uniquely within North America — the new technology was not regulated by a secular, bureaucratic apparatus. Instead of matching the modern amusement with modern governance, the standards of local cinema-going were set parochially, that is to say outside of the transparent rule of law. This contrasted with all of Canada and most of the United States, where novel legislation was introduced specifically to address the novelty of cinema.

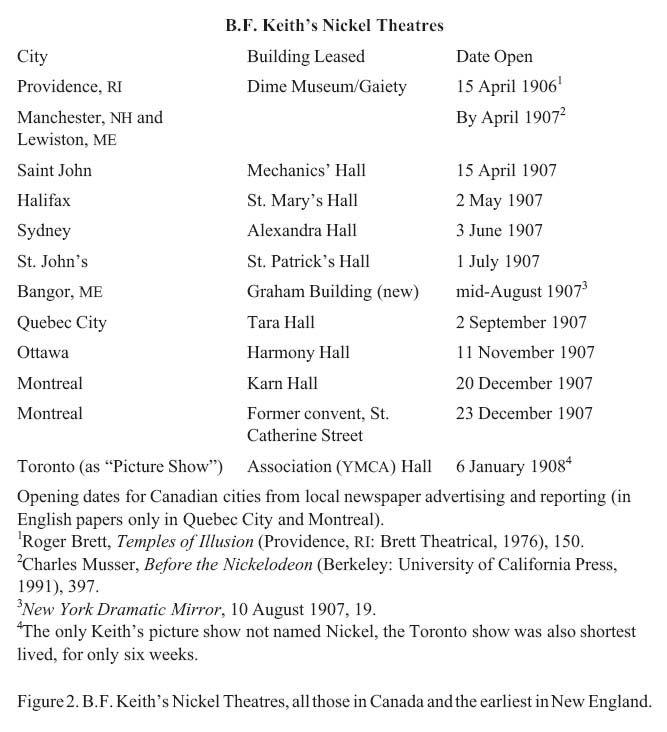

2 On 1 July 1907, an American-affiliated company opened the Nickel Theatre in St. Patrick’s Hall directly across Military Road from the Roman Catholic Cathedral. By October 1907, three more "five-cent picture shows" were open in other association halls in St. John’s. When the fourth opened, the Evening Herald noted wryly that every available hall except one was now devoted to five-cent shows, which appeared to have "a cinch" on entertainment in town.1 Some shows boasted that they were locally run, but all relied entirely on a constant flow of moving pictures and illustrated popular songs shipped from New York, often after first playing at affiliated theatres in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. In his Lenten Pastoral for 1908, the first since the shows opened, Roman Catholic Archbishop M.F. Howley amended Newfoundland’s Regulations for Lent to specifically prohibit attending moving picture shows, and railed against the demoralizing effects on family and religious life, notably across all classes:During the past year some new forms of entertainments have been introduced here, under the name of Moving Pictures.... It is painful and shameful to see not only children but grown-up persons, fathers and mothers of families, constantly frequenting those places of amusement, wasting hours upon hours of time when they ought to be attending to their work or household duties ... not to speak of the example of frivolity and silliness given by persons whose responsible positions would lead us to expect something more sedate and prudent from them.2While moral reformers in the biggest American cities and in Toronto had already cast moving pictures in similarly disparaging terms, they had called for formal and bureaucratic policing and censorship rather than sermonizing the public itself. Howley’s focus on moving pictures was exceptional for a Catholic pastor, not echoed by the archbishops of Halifax or Saint John, although their parishioners were also entering their first Lent amidst the temptations of the five-cent show.3

3 The point is not that Newfoundland was any more or less moralistic, strict, or harsh. No jurisdiction was as moralistic in its response to the movies as Toronto, where Sunday shows were banned, censorship was a constant police duty, and careful standards governed theatres’ construction, location, decoration, labour, attendance, and advertising. If anything St. John’s — even within the purview of the church — had minimal, less moralistic interference with the daily operation of theatres. But every aspect policed and regulated in Ontario, Manitoba, British Columbia, and almost everywhere else in North America, was eventually written into laws, carefully made transparent and rationalized, distinctly and proudly part of the public record. What happened in St. John’s was extra-legal, informal, and undermined the modern precept of the transparent rule of law. As Melvin Baker has carefully documented, in this period the St. John’s municipal council was cash poor and lacked the power to tax, police, and service the city at anywhere near the level becoming normative throughout North America. At times, the colonial government even suspended the existence of an elected council altogether.4 It was thus not only religion contributing to the parochial character of film regulation. The municipal structure overall in Newfoundland was feeble, implying that the colonial government refused to accept bureaucratic regulation and public safety measures as the cornerstone of the people’s welfare, as has been theorized for American cities.5

4 The social debate over cinema in Newfoundland did not stem from the technology of the "bioscopic" projector, nor from the novelty of gathering to view living pictures. Cinema did not become controversial in Newfoundland until it became a social technology in 1907 with the daily availability and cheap cost of a moving picture show. A five-cent show was a force of modernism because of its commercial, secular context, rather than its content or optical technology in itself.6 Howley himself, for example, during Lent in 1897 had given a series of illustrated lectures, using a magic lantern projector of still pictures to tour the Holy Lands of Egypt and Palestine.7 Before the Nickel and its imitators, for the previous decade, cinema commingled more easily amidst an irregular schedule of touring, professional dramas and local, amateur performances, the latter often serving fundraising purposes. The first exhibition of moving pictures in Newfoundland was a demonstration of the Lumière Cinématographe on 13 and 14 December 1897 in the Methodist College Hall for 30 cents admission. The Daily News noted that "nothing of the kind has ever been shown in St. John’s before," and listed the films shown as including Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Procession, Bedouins with Loaded Camels, Arrival of an Express Train at Lyons, Fifth Avenue in New York, and a Serpentine Dance of the kind popularized by vaudeville performer Loie Fuller.8 The Evening Telegram explained the projection would be thrown 100 feet onto a screen 11 by 12 feet, the film passing before the lens at a rate of fifteen pictures per second.9

5 It thus took about two years after the Paris debut of the Cinématographe for it to reach St. John’s; a year and a half after the Lumière apparatus had given the first moving picture shows in Canada in Montreal late in June 1896; and just over a year after moving pictures had first appeared in Halifax and Saint John.10 The next several public cinema shows in St. John’s were "Grand Bioscopic and Stereoscopic Exhibitions" at the British Hall in June 1898, April 1899, and April 1900.11 The first of these three exhibitions was presented by Mr. Pooke, manager at St. John’s Electric Light Works, who apparently owned a projector (by then for sale through the Sears-Roebuck catalogue, for example). Newspapers noted that Pooke included some local scenes alongside selections from his "collection" of filmed scenes from Europe and around the world.12 The escalating profitability and mobility of the apparatus was demonstrated in February 1901 when two touring shows appeared simultaneously in St. John’s.13 By 1905 in many American cities and in 1906 in Toronto and Montreal, permanent five-cent moving picture shows opened, giving the still-novel amusement an institution of its own.

6 This mass market of moving picture shows gave cinema its own institution: the movie theatre. About a decade after their North American debut in 1896, thousands of entrepreneurial showmen and several well-financed companies almost simultaneously opened small "nickel shows" in every neighbourhood of big cities and almost every town on the continent. Like the mass-produced uniformity of its content across the continent, local regulations were largely standardized, using existing measures as models with only minimal local variation. Major metropolises responded to the technology of cinema by inventing new bureaucratic technologies to match. These urban practices set precedents for provincial and state laws and bureaucracies thus covering small town and rural areas.

7 On the farthest eastern edge of North America, the city of St. John’s, Newfoundland, not yet part of Canada, was an exceptional place where there was instead little regulation of early picture shows. Since the content of films and popular music was not particular to St. John’s, it is worth listing a few factors that made the place distinct, especially for an urban site, in addition to the relatively weak powers of its municipal council: St. John’s was a rare city with a majority Roman Catholic population within a majority Protestant region14; rather than commercial sites on shopping streets, the halls leased for shows were pre-existing buildings run by civic and religious associations; the Roman Catholic Archdiocese acted largely outside of secular governance to curtail the influence of the modern amusements on its parishioners. All of these factors might prompt a comparison with rural areas, especially in Quebec, but, since St. John’s was not rural, the parochial factor would only be reinforced. The integration of this mass practice was somehow both commercially similar to elsewhere yet culturally unique to this place.

8 Municipal, provincial, and state governments typically met the picture show with formal bureaucratic measures, generally aiming for transparency by carefully separating social influences from regulatory institutions. Parents, educators, religious ministers, and self-appointed reformers had their part to play, but their complaints against businesses were mediated by policing, inspection, and licensing, which were supposed to reflect rational, modern techniques of governing.15 For moving picture shows this meant annual licenses dependent on detailed fire safety stipulations, trained and examined picture machine operators, adult accompaniment laws, and especially censorship boards to inspect all circulating films before their distribution.16 None of these were introduced to St. John’s or the wider colony of Newfoundland. Instead, the modernity of the novelty mass practice of moving pictures seems to have been integrated culturally through distinctly informal means of municipal governance.

9 Despite this parochialism, all the concerns and issues that led elsewhere to those measures were debated, preached about, even brought to the attention of the Constabulary. That is the subject of the remainder of the paper, explained in the context of the novelty’s business arrangements. Discussions of the emergent place of moving pictures in the everyday life of St. John’s did not sort into the typical situation of organized reformers calling for regulation as government composed laws to curb the excesses of commerce through council bylaws and police inspection. Put concisely, in St. John’s the separation of sacred and profane was often blurred. Church, police, council, and showmen alike took on various responsibilities whose jurisdictions were more clearly distinguished elsewhere. The case of moving pictures indicates, in effect, that there was a tendency in St. John’s to balance, rather than separate, parochial means of moral regulation with modern means of municipal regulation.

THE NOVELTY PASTIME OF DAILY PUBLIC AMUSEMENT

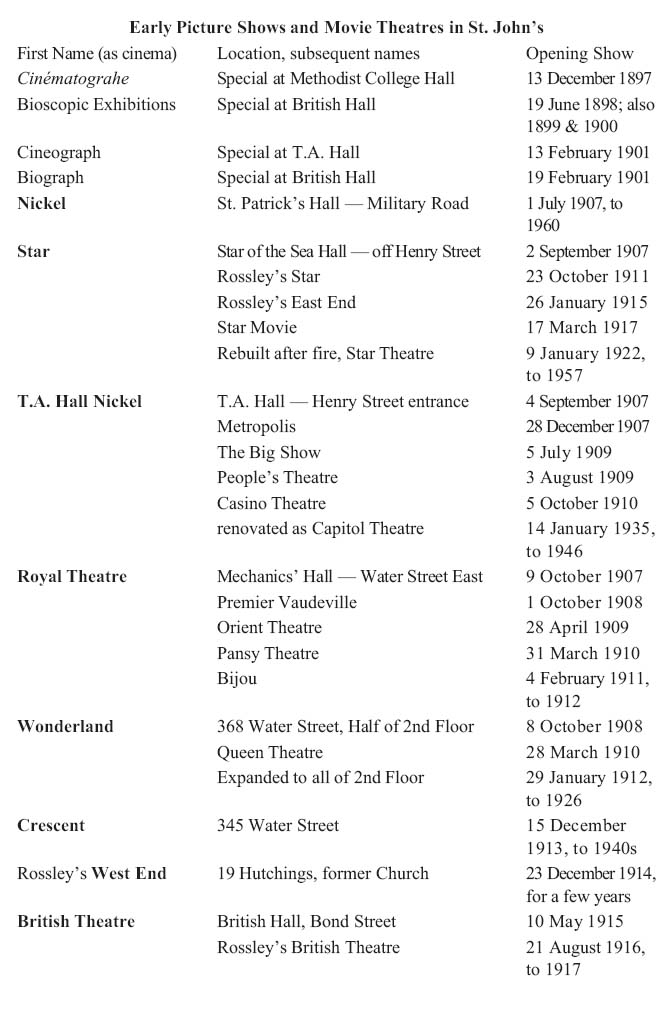

10 When the Nickel Theatre opened in St. Patrick’s Hall in July 1907, it was the first permanent, commercial, daily amusement in the city. The Nickel, still today, is fondly recalled as an important local institution in the city, for example serving as the name for the province’s annual independent film and video awards. At one point, its opening was thought the very first film show in the colony, and it remains a marker of the entry of modern amusements into Newfoundland culture.17 Although temporary cinematograph engagements had taken place in St. John’s since 1897, the Nickel’s opening in 1907 happened amidst a continental boom period in picture shows.18 The picture show fad was already mythologized as starting with Pittsburgh’s Nickelodeon in 1905.19 The craze became continental quickly with the rapid spread of "nickelodeons": small, entrepreneurial shows quickly converted from storefront properties, and thus a term never used in St. John’s and inappropriate for its shows with one exception. The first "scope" in Montreal advertised its opening on 1 January 1906, the first "theatorium" in Toronto recalled as opening later that spring, elsewhere in Ontario in the fall of 1906, and really flourishing throughout Canada in 1907. The picture show was imported to St. John’s intact: a copy of a mass-reproducible commercial practice based on mass-produced content.

Figure 1. Longtime manager, John P. Kiely, on the steps of the Nickel around the time of its closure in 1960.

Display large image of Figure 1

11 The Nickel Theatre and its opening in July 1907 might now symbolize the local character of early film-going, but much more than the idea of a five-cent show was imported to Newfoundland. The canisters of film were imported, as well as the sheet music and slides used to illustrate the popular songs that were part of the program, and only rarely adapted to add local colour. More importantly, the investment and management of most early shows were imported as well: the Nickel Theatre was part of the B.F. Keith’s chain of picture shows, one of a string of thea-tres that ran out of Boston up through New England and the Maritimes, and out to Newfoundland. The first managers published news of their plans to expand to Newfoundland in the New York Dramatic Mirror weeks before details were reported in St. John’s newspapers.20 The company’s name was registered as Newfoundland Amusements by Montreal lawyers, and its first manager, Fred G. Trites, was sent from Saint John. Well-known, longtime manager, John P. Kiely, first showed up in town as an agent for the chain, leaving briefly to manage the Nickel in Quebec City before returning permanently.21 While its foreign connections are perhaps disappointing to note, it is important to pause and consider how it was profitable to do so. Films travelled at least two days’ ferry and train ride — passing through Newfoundland customs with 40 percent duty — and yet it was still possible to charge only a nickel admission. St. John’s Nickel thus demonstrates how immensely profitable the nickelodeons closer to New York and Chicago must have been.

12 Keith’s Vaudeville in Boston laid claim to inventing "continuous" vaudeville.22 Without a break between the end of one show and beginning of the next, Keith’s was one of the earliest places to put moving pictures on the variety program — as the "chaser" act at the end of the bill. Late in 1906, the chain had entered Canada directly in Saint John.23 As part of the nickelodeon boom and its profitability, the chain was already operating "Nickel" shows to supplement some of its vaudeville theatres in New England. Early in 1907, Keith’s decided to expand their chain in Maine and into Canada through five-cent pictures-and-song theatres rather than big-time vaudeville. These corporate roots were rarely discussed in the local papers alongside ads for the Nickels (in St. John’s the link was flaunted only briefly for the second season in 1908), but reports in the moving picture and amusement trade papers make it clear, publicizing the plans even before the St. John’s Nickel was open.24 By August 1907, there were a total of seven in the chain, with an eighth in Bangor, Maine, about to open.25 Having established a network out to Newfoundland, the Keith chain then doubled back to places where it faced competition, in Quebec City, Ottawa, Montreal, and finally to Toronto (its only failure, a short-lived venture at the YMCA hall).26

Figure 2. B.F. Keith’s Nickel Theatres, all those in Canada and the earliest in New England.

Display large image of Figure 2

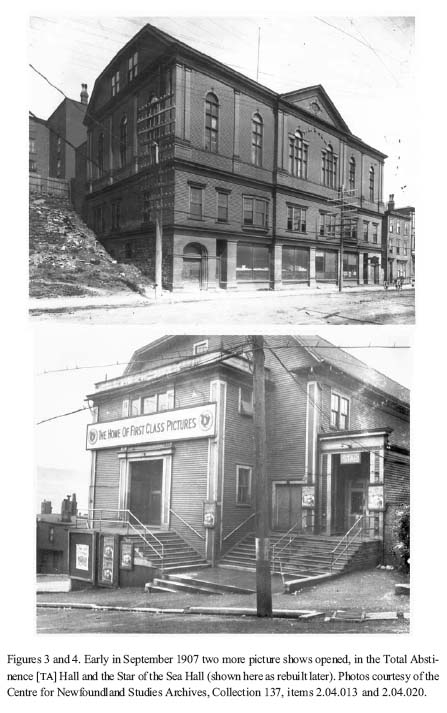

13 As in St. John’s, the strategy in Canadian cities was always the same: lease a large, existing association hall, advertise daily in the newspapers in the same style as a legitimate playhouse, and perhaps unintentionally encourage competition by opening up distribution networks. Exploiting economies of scale and formal connections back in New York gave Keith’s Nickels the advantage of priority to films. And competition did flourish once the Keith’s Nickel chain proved that a site was profitable.27 Around Labour Day 1907, two more five-cent shows opened in St. John’s, at the Total Abstinence [TA] Hall, and at the Star of the Sea Hall. Negotiations to lease these halls had begun just a couple of weeks after the Nickel opened. On 11 July 1907, G.E. Couture, manager of the new King Edward Theatre in Halifax, corresponded with the Star of the Sea Association about the condition and possible terms of leasing the hall.28 He ultimately leased the Total Abstinence and Benefit Society’s larger and more ornate TA Hall instead.29 In August, a request to rent the Star Hall for $1,500 a year was received from Mr. J.A. Gagnon, but an offer had already been extended to local entertainer John Burke.30 Some of Burke’s ads specifically note his five-cent show was local.31 In October, a fourth show opened at the Royal Theatre in the Mechanics’ Hall, run by Mr. Blumenthal, although further details are unknown.32

Figures 3 and 4. Early in September 1907 two more picture shows opened, in the Total Abstinence [TA] Hall and the Star of the Sea Hall (shown here as rebuilt later).

Display large image of Figure 3

14 The profitability was not ensured, as these St. John’s shows required substantial lease payments and wages on top of film rental fees. Consider an article about the Nickel in the Evening Chronicle that listed sixteen "most prominent" employees of manager Trites: a door-keeper, press representative, machine operator, five ushers, two cashiers, an assistant manager, two musicians, and three vocalists.33 Burke’s lease agreement for the Star Hall required him to pay all of the lighting, heating, and maintenance on top of $30 a week rent and another $36 weekly wage for the janitor.34 If Burke had even one-quarter the number of employees as Trites at the Nickel, earning only as much as the janitor, then the first 700 tickets sold each day would just barely cover his minimum expenses, not counting heat and light nor the cost of the films, music, and song slides.

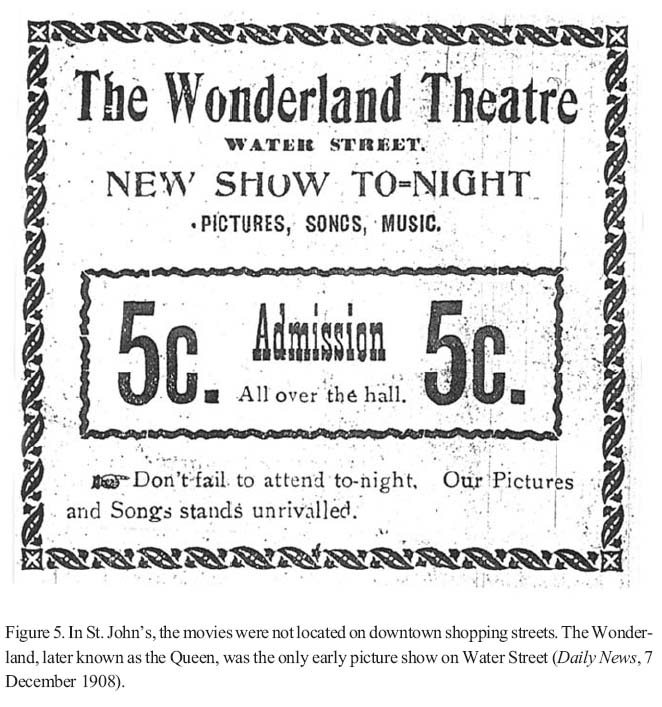

15 Unlike in Halifax, Saint John, Montreal, or Toronto, unlike almost any other city, none of these first four shows in St. John’s were located downtown on the Water Street West shopping strip. In other cities, the halls leased by Keith’s for Nickel Theatres were always on downtown shopping streets. But in St. John’s, St. Patrick’s Hall was instead uphill across from the Roman Catholic Cathedral. This is exceptional because early picture shows were integrated into routines of consumption, part of the downtown scene, commercial sites as much as cultural spaces.35 While none of the Nickels were small, store shows, they were still always downtown, except in Newfoundland.

16 St. John’s had a different type of social geography even before the movies came to town. The Nickel and its competitors largely fit into that existing shape, rather than remaking downtown into a theatre district with bright lights and night life. In St. John’s, associations for civic, religious, or leisure purposes alike had long been off Water Street. Associations like the Benevolent Irish Society, the Star of the Sea, the Total Abstinence and Benefit Society each had to own and thus build on lots away from downtown. This is why the Nickel, Star, and TA Hall theatres, respectively, ended up away from downtown in turn. Theories about downtown and urban life tend to conflate leisure, and thus movies, with consumption. In big cities and small towns alike, movies were inextricable from downtown, providing women a degree of public independence while shopping and giving children some unmonitored independence with just a nickel in the hand.36 Instead, in St. John’s, movies are already spatially once-removed from the secular, commercial life controlled by Water Street’s merchants. The simple fact of being in existing association halls would already have tempered the strangeness and novelty of picture shows. Being closer to home in uphill halls in non-commercial areas made the shows doubly domesticated in St. John’s, a good context for local authorities to balance regulation with a degree of parochialism.

Figure 5. In St. John’s, the movies were not located on downtown shopping streets. The Wonder-land, later known as the Queen, was the only early picture show on Water Street (Daily News,7 December 1908).

Display large image of Figure 4

17 There is, however, a single exception that proves the rule. St. John’s fifth picture show, the Wonderland, opened in October 1908.37 It alone followed the entrepreneurial type similar to nickelodeons or theatoriums in other North American cities and towns. First operated by local merchant J. Burnstein, it opened in a cramped space, not a spacious hall, seating just 300 people on the second floor of a Water Street shop adjoining a billiard hall.38 This, finally, was the nefarious, commercialized fire trap that in the rest of North America attracted concern from parents and moral reformers, ministers, mayors and aldermen, fire and police chiefs, and insurance adjusters. The Wonderland flourished like the other shows in town, if on a smaller scale. Unlike the others, it rarely advertised. Perhaps it did not need newspaper ads, being much smaller and right on Water Street, or perhaps it was simply less profitable and could not justify the expense. Better known as the Queen Theatre after John J. Duff bought it in 1910, it expanded to twice the space (still on the second floor) in 1912, before the new Queen was built back onto George Street in 1926, still using the Water Street entrance as a lobby.39 Not until 1913 did just one other show open on Water Street, the Crescent, operated by a long-standing dry goods merchant, P.J. Laracy, right across from the Queen in what had been his store site. The Queen and the Crescent hardly added up to make Water Street a theatre district in the fashion of Broadway in New York or rue Ste. Catherine in Montreal, let alone Halifax’s Barrington Street or Saint John’s Charlotte Street around King Square. If anything, the Wonderland being alone downtown in 1908 demonstrates how distributing films to St. John’s took a few years to become routine enough for a small entrepreneur to open a storefront show in the more conventional urban form as happened elsewhere. The Nickel’s Keith-chain status was a necessary first step because of the financial risks and continental trade involved.

REGULATIONS RESPOND TO THE NOVELTY PASTIME

18 Just as the spaces of St. John’s picture shows were different from elsewhere, the promotion and advertising differed from metropolitan cities, too. In Toronto and other large cities throughout the US and Canada, the earliest five-cent shows were at first anonymous shops downtown without newspaper advertising. They drew the attention of investigative journalism when calls came for censorship and restricting children’s attendance.40 This early journalism focused on understanding the marginal audience, the appeal of the novelty to children, young working women, and foreign-born ethnic audiences. Indeed, the best-described audiences in Toronto, but also in Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York alike, were specifically ethnic — Jewish, Italian, Mexican, or Japanese, depending on the minority enclave of most concern in each city.41 In large, metropolitan cities, the early picture show was not instantly a mainstream, mass practice. The mass character of movie-going was not determined by its technology or even its practiced format, but rather had a gradual process of normativization. This mainstreaming was achieved through shifts in showmen’s advertising, reconstruction of theatre spaces, and also with the introduction of regulation and censorship. Of course, filmmaking also became a vertically integrated big business with name-branded studios and the iconic faces and names of movie stars. To generalize, advertising, regulation, and the feature film combine to make the movies a mainstream, mass practice sometime around 1913, just in time to make the use of movies for wartime patriotism seem like a natural consequence.

19 The story for smaller cities like Halifax and Saint John is different, with picture shows respectable and mainstream earlier, but at the local level, not necessarily part of a regional or transnational mass culture. Even those smaller cities differ from St. John’s because daily, commercial theatre or vaudeville was already common before picture shows arrived. The movies could be seen as cheaper and more crass but the idea of a show day-in day-out was nothing new. However, the St. John’s Nickel really was the first reliably daily show in Newfoundland. The gradual emergence of a mass practice out of marginal novelty does not quite apply in the same way. Instead, its advertising right from opening day demonstrated, indeed bolstered, the idea that the picture show almost immediately changed local leisure routines. In one sense, the Nickel and its early competitors created everyday public amusements in St. John’s. The four shows seemed like a barrage transforming the town; "Still They Come," the Evening Herald wrote.

20 I have found just one letter to the editor of the St. John’s Daily News about these issues, but the writer indicates that a dramatic effect on schooling, parenting, and family life had occurred. Perhaps written by a schoolteacher but signed simply "A Parent," the letter notes with apprehension how the schoolchildren of St. John’s had become obsessed with the picture shows, "I might say a rage."42 The writer claimed the city’s children had come to spend all their spare time attending and talking about the shows, where they used to discuss their schoolwork and do homework in the evenings. Compared to 1907 before the shows opened, she notes, grades had fallen in 1908, even the grades of better students! One showman’s decision is lauded: to bar children under fifteen years old from attending in the evenings, not even if accompanied by parents and adults. This recognition that moving pictures had significantly and quickly changed the leisure pursuits of people in St. John’s, especially children, is somewhat at odds with the way showmen were promoting and advertising wholesome shows for the betterment of the city’s public.

21 From their beginning, film showmen in St. John’s aimed their pastime inclusively at an audience of "everybody," again meaning at the local level rather than the continental mass public implied in advertising in later years. This is quite different from American industrial cities where picture shows were decidedly working-class, ethnic, juvenile, or all three, and from Montreal where the "scopes" are now held up as a French "alternative public sphere."43 The difference partly comes from there being so little distinction among types of commercial leisure in St. John’s beforehand. In the decade before the Nickel, local amateur concerts and shows were promoted almost identically as touring, commercial theatre companies. In both cases, the entire public was invited, and there was no marked distinction between the type of entertainment and the expected class of audience. This interchangeable promotion of all forms of public amusement continued briefly even with the picture shows opened; for example, the Nickel’s Leo Murphy’s correspondence with the New York Dramatic Mirror about activities in St. John’s in 1908 and 1909. All other cities’ correspondents simply list what was on stage at the biggest, legitimate theatres, ignoring small-time vaudeville and picture shows altogether. Murphy’s reports instead make no distinction between commercial and civic leisure, let alone big and small shows. He lists recitals and sacred concerts at various halls, notes special nights of roller skating and wrestling, a Parish concert, and a college alumni performance. Murphy seems intent upon showing how the pictures in this city were integrated into a full range of more traditional pastimes.

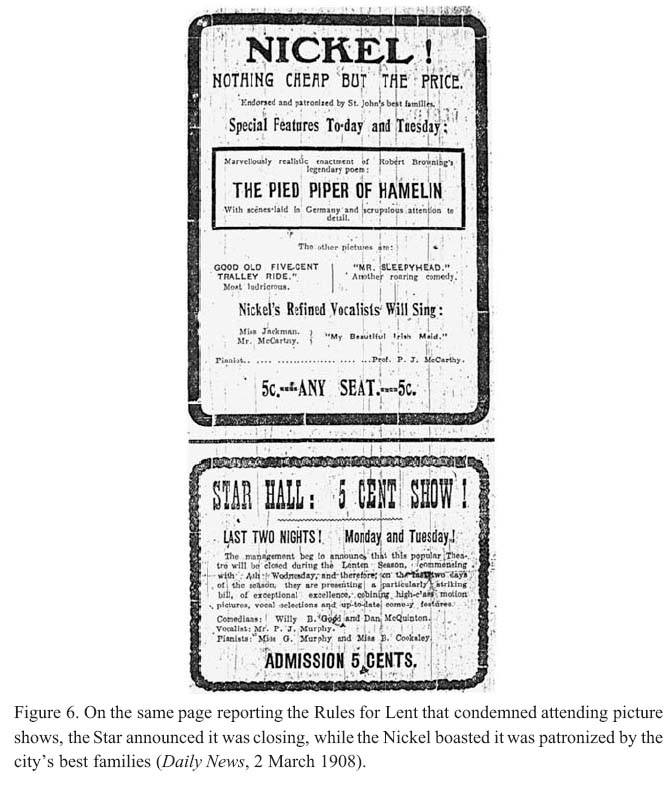

22 If showmen were trying to prove their integration with community, others with responsibility for the well-being of the city’s people were trying to dampen the novelty’s appeal. The Roman Catholic Church in Newfoundland responded quickly to the novelty amusement. Sermons and Lenten Pastorals in 1907 had rebuked young men’s drunken nights and young women’s hankerings for dances and parties.44 Moving pictures expanded the practice of such hedonistic public amusement to include children and families. The 1908 Regulations for Lent were re-written specifically adding the word "shows" to the list of forbidden practices, which had already been comprehensive, listing "dances, parties, balls and theatrical or other public entertainments ... except on St. Patrick’s Day on which from immemorial custom it is permitted to hold a dramatic or musical entertainment of a patriotic or national character."45 In the first Lenten edicts after the picture shows arrived, Archbishop Howley specifically vilified this novelty pastime. In his Lenten Pastoral for 1908, Howley spent over one-third of the sermon preaching in detail about the evils and problems of the "new forms of entertainments" that had appeared that year "under the name of Moving Pictures."46 The evils and errors of modernism had already been a theme that the Catholic Church was striving against, and with picture shows it suddenly turned into a concrete daily practice. The Pastoral could point to a specific place and pastime as emblematic of the overall secular tendency that was seeping into parish life.

Figure 6. On the same page reporting the Rules for Lent that condemned attending picture shows, the Star announced it was closing, while the Nickel boasted it was patronized by the city’s best families (Daily News, 2 March 1908).

Display large image of Figure 5

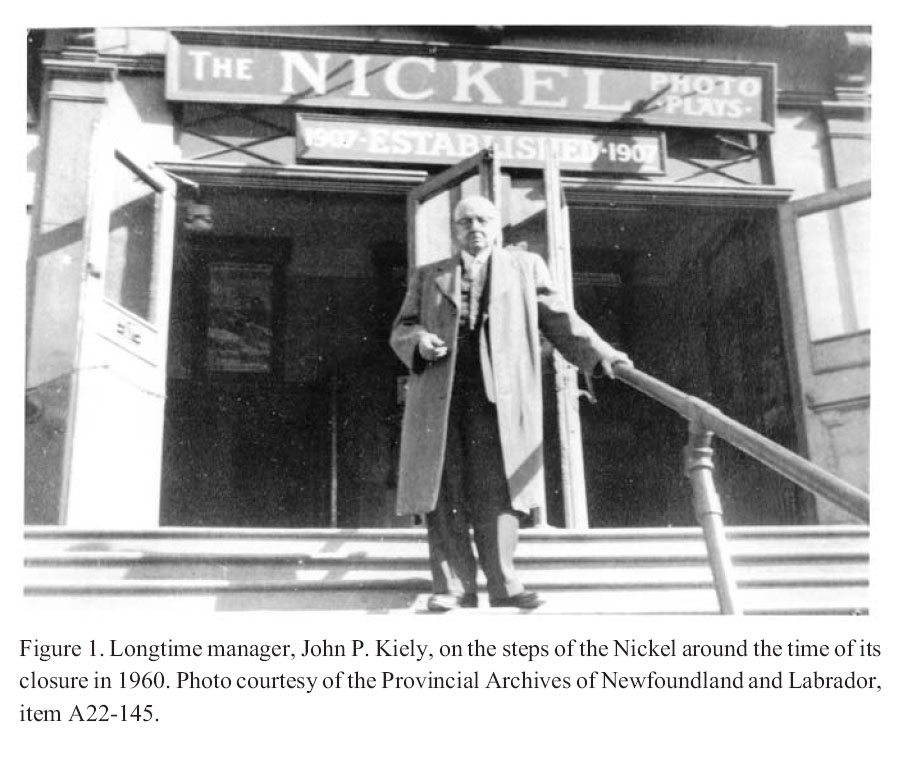

23 Of the shows leasing halls from Catholic-affiliated associations, only the Star closed for the entire 40 days of Lent (except St. Patrick’s Day). Despite operating in Catholic-associated halls, the Nickel in the Benevolent Irish Society’s St. Patrick’s Hall, and the Metropolis in the Total Abstinence and Benefit Society’s TA Hall both remained open despite the ban on Catholics attending shows during Lent.47 Even the Nickel and Metropolis closed for Holy Week, with all three reopening with great publicity on Easter Monday. Holy Week closings happened annually for several years, an occasion for a thorough cleaning, repainting, and redecorating of the halls. I have not noticed picture theatres closing for Lent or Holy Week anywhere else in North America, not even in Quebec. Abbreviated reiterations of the evils of amusements were included in Howley’s Lenten Pastorals again in 1909 and 1910, but no longer in 1912 or 1913. The ban on Lenten shows and the tendency to close for Holy Week or Lent was lifted entirely in 1915, perhaps in recognition of the fundraising role theatres played in support of the sealing disaster the previous year.48 During Lent in 1915, special shows raised funds for charitable causes, in one case literally giving loaves of bread to the city’s poor in exchange for their ticket stub.49 Even after the Regulations for Lent were officially changed, some theatres continued to close during Holy Week and fundraising occasions continued intermittently in recognition of the religious season.

24 In 1908, however, showmen in St. John’s used their advertising to defend their shows, noting how these were civic spaces, safe, clean, moral, and uplifting. Descriptive phrases advocated for the civility and respectability of their programs, the cleanliness of their auditoriums, and the propriety of their audiences. While "up-to-date" amusement was a claim all held, the Royal was perhaps the first to draw attention to the quality of its auditorium, not just its shows: "Have you ever seen our shows? If not, why not? Visit our comfortable theatre to-night."50 The Metropolis then put cleanliness next to comfort, if not godliness: "Our theatre is scrupulously clean, commodious, comfortable, while its central location makes it within reach of all."51 Adjacent to the synopsis of Archbishop Howley’s Pastoral condemnation of amusements, the Nickel rebounded with "Endorsed and patronized by St. John’s best families," while the Star that same day announced "This popular theatre will be closed during the Lenten Season."52 Perhaps struggling with a drop in attendance during Lent, the Nickel spelled out its case inside of its advertising: "Don’t forget that this theatre is sterilized twice weekly, therefore perfectly clean; it is steam-heated, well ventilated and in every way the most up-to-date playhouse in the city."53 The Nickel, in particular, was savvy (or simply fortunate) to present the worldwide phenomenon of an elaborate film of The Passion Play in February 1908 just before Lent. The Daily News reported about the first showing that "in the audience was a representative gathering of clergymen, who express[ed] to the management their great surprise at the excellence of the subject dealt with."54 The same films of the Passion Play had for the previous months played to much the same acclaim and pious hype all over North America. It had prompted several theatoriums in Toronto to advertise for the first time in September 1907. Curiously absent in responding to moving pictures are Methodist or Church of England reformers in St. John’s. In this period, temperance seemed to be their primary cause. Thus, almost single-handedly and without banning films or obstructing commercial leisure outright, the St. John’s Catholic Archdiocese kept close parochial oversight of the place of moving pictures in St. John’s society. Indeed, Howley’s 1908 Pastoral explained,Some of these exhibitions are objectionable from a moral and religious point of view, and strongly suggestive of pruriency, and complaints on the matter have been made to us. We have communicated with the Police Authorities on the matter, and have received a guarantee that these shows are closely watched, and that at the very first appearance of anything immoral — or even immodest — they will be closed by legal authority.The police were apparently invited to patrol theatres by showmen, too, although the only direct mention of this was for the Nickel’s opening in 1907. In advance of the event, Manager Trites arranged for several policemen to supplement the staff.55 Even the Catholic Church recognized the authority (and efficacy) of the constabulary, who had the ability to bring charges to the magistrate against any purveyors of indecent and obscene material.56 The integration of moving pictures into St. John’s society was not entirely parochial, and measures such as the Regulations for Lent were balanced with the secular policing of indecent acts.

Figure 7. For over a decade, most St. John’s theatres closed for Holy Week and had grand re-opening shows on Easter Monday (Daily News, 20 April 1908).GOVERNMENT CODIFIES THE REGULATION OF PUBLIC SPACE

25 The main mechanism of municipal governance over commerce and amusements is licensing, thus making a business register and seek approval with city hall before it opens. The license has been theorized as a uniquely municipal legal technology, as state governance without direct surveillance.57 It works by dispersing the tasks of policing and patrolling to the management and ownership of businesses, making the proprietors responsible for their patrons, in a sense making businesses keep the public order or risk losing the license to operate. In Toronto, annual amusement licenses were set at $50 by 1890, years before moving pictures appeared, and well over a decade before picture shows proliferated. In all of Ontario, initially as a fire safety statute, places handling film were required to have such a municipal license from 1908, and in 1909 the province itself began licensing all moving picture machines and their operators in addition to municipal licenses for the buildings.58 Similar licensing codes and fire safety bylaws, typically issued by local authorities in the US and mandated by provincial governments in Canada, were the primary route of surveillance of amusements. No such licensing of amusements seems to have happened in St. John’s. The Municipal Act of St. John’s did not even allow such authority, let alone mandate its implementation.59 While the two Water Street shows would have required building permits before construction began, leased association halls were not required to do anything bureaucratic to operate, and there seems no allowance for routine inspection after opening beyond the general policing of criminal and indecent acts (i.e., policing persons, not regulating businesses). Indeed, fire safety standards for movie theatres appear implemented only in 1936, nearly three decades after such laws were the first written specifically for cinema in Ontario and Quebec.60

26 In British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec, both municipal and provincial police forces were variously mandated to regulate moving pictures — sometimes in apparent conflict with each other, and, by 1913, replaced entirely by bureaucratic theatre branches of the provincial treasuries. In contrast, the Newfoundland Constabulary appears not to have had the authority, let alone the mandate, to inspect, approve, or license theatres and projectors for safe operation, to examine and license picture machine operators for proper training, nor to require children’s adult accompaniment. Whereas the Catholic Archbishop of Newfoundland felt he had to personally sermonize about picture shows, the Canadian Presbyterian Church had already in 1910 recommended simply that the bureaucratic measures of Ontario become national standards. The Canadian Methodist Church in 1914 cited approval when such nation-wide standardization had actually been achieved.61

27 Instead of amusement licensing, the St. John’s Council was given the power to levy an entertainment tax in a 1910 amendment to the St. John’s Municipal Act. Given the theory of indirect surveillance ascribed to licensing, it seems important that the Newfoundland colonial government allowed City Council only the right to tax as opposed to license amusements. This permission to tax, not license, continued with the City of St. John’s Act in 1921, the foundation of the current version.62 In the first year of the Amusement Tax, 1910, the city collected 4 percent of gross receipts at the box office, a total of $899. The rate was then decreased to 2.5 percent for a few years, before settling at 3.5 percent from 1914 for 20 years. Up to $5,500 was raised annually by the city from the entertainment tax, a substantial 1-1.5 percent of total municipal revenues.63 Such taxation contrasted with proper licensing fees by treating mass entertainment as a foreign element in the economy rather than an integral part of it. For the movies in particular, this might have been an accurate assessment of the relationship with the culture of the community, but the situation differed entirely from elsewhere in North America. Amusement taxes elsewhere begin only in 1916 as a way for governments to fundraise for World War I.

28 The comparison with elsewhere is reversed for film censorship, which had begun before World War I in Canadian provinces (as early as 1911 in Ontario), but was introduced to Newfoundland only as an anti-propaganda war measures act in 1916. Its form was anti-bureaucratic and largely ceremonial rather than the codified systems of inspection and professional boards in effect elsewhere. Rather than a review board, the Newfoundland censors were three patronage appointments without salary or budget, who each had the authority to enter any theatre "for the purposes of inspecting and passing upon the fitness for public exhibition" of any moving or stationary picture, film, or slide. A quorum of two out of three could decide to stop the show.64 The slight debate over the bill recorded in the Proceedings of the House of Assembly shows that this, too, was inscribed with a careful balance of parochial and bureaucratic intentions.65 First up in the House, Prime Minister E.P. Morris made a weak case for the importance of moving pictures overall, constructing a circular argument: "Everybody knows that the moving pictures are a great educator, and not only are they educators, but afford pleasant cheap amusement. In this way, at a very reasonable rate they not only prove a good amusement maker, but a good educator." His case in support of censorship was just as feeble, as the only concrete advantage to the bill was its cost: none. An opposition member, W.F. Lloyd, actually made a stronger case for censorship, against propaganda to ward against German, American, and Irish Nationalism. In a political compromise not uncommon in Newfoundland, the censor board initially included one Methodist member, one Church of England member, and one Roman Catholic.66

29 The rigour of censorship largely depended on time volunteered by the appointed members, and the quality of inspection ebbed and flowed with the fiscal support of government. It is clear from archived correspondence, however, that the censors themselves took their job seriously and tried their best to perform their duties in the style of the massive film board bureaucracies in Canadian provinces, despite having neither the resources to do a thorough job nor the legislation to enforce their decisions. For many years, as is clearly archived, they were able to pass judgment upon every film playing in St. John’s (and therefore in all of Newfoundland), assisted greatly by the apparently voluntary cooperation of St. John’s showmen. When controversy or complaints arose, showmen and censors met with clergy from several religious denominations to decide what best to do — the entire routine proceeding outside the letter of the law and unenforceable in court should any theatre manager contest the consensual norms that had been established.67 Censoring was eliminated in practice after Newfoundland joined Canada in 1949, by simply relying on decisions from Nova Scotia. Yet, the law remained on the books until 1996 when it was repealed in a massive housekeeping, striking down dozens of anachronistic statutes.68

30 This summary of the regulation of early moving pictures in Newfoundland has emphasized how laws and practices continually balanced modern, bureaucratic measures with traditional, parochial moral pressures. Moving pictures were adopted and adapted into the leisure time of St. John’s largely outside of policed, political, and bureaucratized institutions — perhaps a singular case among all of North America’s cities. My point is not that informal compromise and the influence of churches only happened here in St. John’s. There are plenty of cases of politicians and police making concessions elsewhere, but it is often called graft and corruption when it happens under a tight bureaucracy. There are also plenty of cases of churches and reformers organizing against the evils of amusement, its avarice and indecency, but it is called lobbying and influence when it leads to formal regulations. The parochial factor in St. John’s meant that showmen could effect compromise without having to systematically undermine regulations, without the interaction taking on the form of systemic corruption or influence. It also meant that the Church could wield its influence through preaching or threatening to sermonize against the movies from the pulpit. Only rarely did the situation lead to backroom politics and direct interference.

31 At the level of the colonial government in Newfoundland, as opposed to the council of St. John’s, this substitution of parochial for bureaucratic governance was certainly unique compared to Canadian provinces. Melvin Baker’s corpus of work on the St. John’s Council indicates a continual tight rein on municipal authority on the part of the colonial government.69 St. John’s had a tax rate far below cities of similar size in Canada and delivered far fewer services and of inferior quality accordingly. Council did not have the ability to run a deficit or raise funds through bonds, and could not decide its own tax rate against absentee landlords in Britain. It had little ability to write its own bylaws, which would have been enforced by the Newfoundland Constabulary rather than by a city police force. Baker thus implies that the parochialism I am describing was an outcome of colonial policy. The City Council was not allowed to introduce rational, modern bureaucratic measures. The city, its people and its institutions, of course pursued parochial means of regulation instead. My study shows that St. John’s picture shows were commercially integrated into the continental mass market even as the city and its local institutions managed and regulated their influence in distinctly local means.

psmoore@ryerson.ca

Acknowledgements

Research in St. John’s was done over many years on trips home while a SSHRC doctoral fellow at York University and a SSHRC postdoctoral fellow at the University of Chicago. Thanks to Beverley Diamond for including a presentation of an earlier version in Memorial University’s series on Music, Media, and Culture. Thanks to editors and reviewers at Newfoundland and Labrador Studies for helping craft the final essay. Helping me respond to reviewers’ comments, my father Joseph Moore located countless new details, dug up archived correspondence and lease agreements, and discovered a cache of censorship records.Notes