Rockin’ the Rock:

The Newfoundland Folk/Pop "Revolution"1

Paul ChafeMemorial University

1 OUTSIDE MY OFFICE there is a poster advertising "A fundraiser for Culture & Tradition."2 Emblazoned with a border of Celtic design, and adorned with the names of the various protectors/performers of Newfoundland identity, the poster also sports the clever name of this benefit concert for heritage: For Folk’s Sake. An obvious play on a well-known expletive, the title reflects the duelling notions of duty and despair that so often form an aura around such moments of protecting and preserving a disappearing culture. In these moments, performers can become what sociologist James Overton classifies as "folk-singing patriots" engaged in a battle of "cultural survival" (6). Sometimes these moments call for more than the playful allusion to gruff language, as Overton notes in "A Newfoundland Culture?" (citing Peter Narváez): "Audiences are told by performers to shut up and be quiet because ‘we’re preserving your fucking culture’" (15). While this punk rock attitude has yet to produce an accordion-wielding Johnny Rotten, it has played a part in the valorization of Newfoundland culture. In local stores, rock T-shirts depicting Metallica, Eminem, and (more notably) deceased and deified idols like Tupac Shakur and Jimi Hendrix are overshadowed by displays of clothing that fetishize "Newfie sayings" like "Whataya’at?" and "Yes b’y!" A shirt embossed with John Lennon flashing a peace sign hangs next to a "Republic of Newfoundland" T-shirt bearing the pink-white-and-green flag (falsely) identified with Newfoundland independence. We have entered the era of the Newf-chic, an era in which a teenager is more likely to wear a shirt proclaiming "Free Nfld" than s/he is to don the likeness of a dead musician or rock star du jour. In light of these "fundraisers" and acts of preservation, I am left wondering if Newfoundland culture, like rock icon Jim Morrison, is beautiful because it is dead? Is the popularity of Newfoundland iconography and "folk nights" indicative of a new and performative pride? Or is it narcissistic navel-gazing that "reclaim[s] culture as a site ... of pleasurable diversion" (Huggan 67)? Has the "Goofy Newfie" that so often accompanied the American and Canadian into the bar been replaced by "The Rock" Idol? Or has this promotion of tradition and music simply left "The Rock" idle?

2 Anyone enjoying a folk night in any Newfoundland pub will quickly notice that this "culture" is truly a "hybrid product" (Huggan 47). On any given night, "traditional" instruments like the mandolin and bodhran will share the stage with a booming electric bass or a Fender Stratocaster. One cannot help but sense this feeling of fierce aggression against assimilation when listening to St. John’s-based band Shanneyganock blast out their rendition of "The Islander." Gravel-gulleted lead guitarist Chris Andrews usually prefaces the song with the part-question part-battle cry "Are there any Newfoundlanders here tonight?" — a question that may seem redundant as he usually asks it while in a bar in downtown St. John’s. One immediately realizes, however, that Andrews is asking if there are any real Newfoundlanders present — Islanders who wear their identity like a medal on their chest, Newfoundlanders who identify with the sentiments expressed by Mark Hiscock’s booming baritone:I’m a Newfoundlander, born and bred, and I’ll be one ’til I die.

I’m proud to be an Islander and here’s the reason why.

I’m free as the wind and the waves that wash the sand.

There’s no place I would rather be than here in Newfoundland....

In Montreal, the Frenchmen say that they own Labrador,

Including Indian Harbour where me father fished

before.

But if they want to fight for her, I’ll sure take a stand,

And they’ll regret the day they tried to take my Newfoundland.

While the chorus seems only to profess a sort of jovial jingoism — "I’m proud ... I’m free ... there’s no place I would rather be" — it is the final verse that advocates a paranoid sense of possession and promise of violence — the vow to "take a stand" and "fight for ... my Newfoundland." These sentiments are hardly unique to the electric age of Newfoundland folk music — one can hear such fierce and fearful phrases in the more traditional "Thank God We’re Surrounded by Water" or in "The Anti-Confederation Song" published anonymously in 1869:Hurrah for our own native Isle, Newfoundland —

Not a stranger shall hold one inch of her strand;

Her face turns to Britain, her back to the Gulf,

Come near at your peril, Canadian Wolf!

Would you barter the rights that your fathers have won?

No! Let them descend from father to son.

For a few thousand dollars Canadian gold

Don’t let it be said that our birthright was sold.

In light of these and many other anti-Confederation songs, one is left wondering why there has been such a profound and prevailing aggression toward Canada.

3 This construction of a culture of defiance and determination is a topic more suited for post-colonial studies and Homi K. Bhabha offers an explanation for such a creation in Nation and Narration: "Culture [is] a strategy of survival," he writes, "Cultural identification" occurs only when a society is "poised on the brink of ... the loss of identity or [what] Fanon describes as a profound cultural ‘undecidability’" (304). It is only when people are massed together and encouraged to absorb into a greater community that "culture" becomes an issue. This "culture" offers a much desired difference and identity to a people on the edge of consumption.

4 Newfoundland teetered perilously over this abyss of assimilation following Confederation with Canada. Overton regards "Newfoundland culture as a construct" (15) and asserts that this culture only came into being to combat the feelings of alienation and financial desperation that plagued Newfoundland before and after Confederation. This theory is given credence when one considers how Newfoundland culture and identity perpetuate an "imagined community" that offers comfort and belonging to the (Anglo-Irish) individual while — thanks to the tourist and music industries — providing the province with a major source of income. Newfoundland culture fits neatly into Bhabha’s notion of culture as a combative construct meant to fiercely protect the self against the encroaching other. This new identity is a conflation of Newfoundland history, or what historian Jerry Bannister refers to as the collapse of "the distance between historical epochs into a single meta-narrative" of how "Newfoundland had triumphed in the face of adversity" ("Politics" 125). The very work, culture, and music of Newfoundlanders thus become part of this meta-narrative, symbolic by its continued existence of a combative and persistent Newfoundland identity.

5 Why after 55 years of union with Canada do these anti-Confederation sentiments still remain? How can artists, most likely playing instruments imported from the mainland, and possibly benefiting from Government of Canada grants to produce their CDs, take to the stage and sing such songs of resolute and rebellious independence? Has life as a Canadian province been so poor as to give rise to a "Secret Nation" or a "Newfoundland Liberation Army"? While the answer to the last question is most likely no, it cannot be denied that toil, hardship, and a pious putuponness have played a major role in the creation of these representations of Newfoundland’s psyche and culture.

6 The performance and preservation of folksongs have gone a long way in maintaining what Bannister calls a "shared historical narrative" ("Whigs" 2) and has ensured that Newfoundlanders remain a distinct and definite society within Canada. This shared historical narrative is based largely upon the "psychic wound" ("Whigs" 18) Bannister claims every Newfoundlander inherits. Confederation with Canada in 1949 was necessary because a short fifteen years before, the then nation of Newfoundland was declared unfit to rule itself by a British Royal Commission. Overton notes the effect of their damning report on the Newfoundland psyche when he cites the responses of J.L. Paton and Joseph Smallwood to the recommendations of the Amulree Commission:the findings of the Commission put Newfoundland’s "national character ... under a shade," according to J.L. Paton. This led to a great deal of discussion about the peculiarities of the Newfoundland character.... During the same period J.R. Smallwood, in a soul-searching vein, was led to argue that Newfoundlanders should shoulder some of the "blame" for their backwardness".... But in spite of all difficulties and regardless of such dark thoughts, Smallwood was not pessimistic, believing that ultimately the spirit of "The Fighting Newfoundlander" would eventually lead to "greatness." (Overton 12-13)Here we can see the beginnings of a Newfoundland identity that has much in common with the target audience of modern rock music. Both teenagers and Newfoundlanders have had to put up with authority figures that have told them they do not know what is best for them. Whereas rock’n’rollers have always told their young audiences to react against their parents, Newfoundland culture and music have always to some extent possessed an underlying message of "trust neither outsiders nor outside authority." Just as rock has united so many young people against the (supposed?) judgment of the previous generation,Newfoundland culture unites people across social divisions based on class, religion, gender, region, etc. It is something that exists as an observable "fact" for many people, even those who see Newfoundland culture as a reaction to put-downs and stigma still assume that there is a common culture or character which is being negatively evaluated, usually by outsiders. (Overton 11)Just as the oft-maligned parents never understand, those who are not from here could not possibly comprehend what being from here means. So, what does it mean?

7 The "shared historical narrative" Bannister discusses takes its roots in the toil and hardship experienced by Newfoundland settlers, or, as Overton puts it, "it is the way of life and the attitudes of the rural small producer [i.e., fisherman] that form the core of a distinctive Newfoundland culture" (11). Or at least it is the way the life of an outport Newfoundlander is perceived. Overton notes how a "promotional pamphlet issued by [Newfoundland’s] Department of Industrial Development" promotes Newfoundlanders as a "hardy, fun-loving race" (7) — "tender, tough, frivolous, fearless, simple, and sophisticated people who keep working regardless of ... suffering or hardship" (7). It is this trope of the Newfoundland martyr, saint, trickster, workingman, and hero that has been exalted to rock-star status in recent years. Though this icon of "Newfoundlandness" ignores the ongoing diversification and urbanization of the province (not to mention the female population, past and present), the fisher trope remains emblematic of Newfoundland culture and identity.

8 The fiddle-and-Fender generation have kept the character of the fisherman at the centre of Newfoundland identity and culture through rock/funk-ified versions of traditional tunes like "Lukey’s Boat" or "I’se da B’y."3 These raucous and refreshing performances are undeniably entertaining, but one cannot help but notice the separation between the upbeat music and its dour subject of the struggling and starving fisherman. In truth, the referent has been lost in these performances as everyone dances, sings, and cheers while the fishermen-narrators of these songs speak of having to eat "maggoty butter" or getting a new wife "in the spring of the year" because the old one is "dead and ... underground." While it is fair to say Newfoundland has its share of mournful songs about shipwrecks and drownings, and Newfoundland folk music’s repertoire of cheery takes on cheerless events is not unique, these songs are indicative of how deep the character of the plucky planter has nestled itself in the Newfoundland consciousness.

9 The woes and work of the fisher family have become the bonding force and saving grace for Newfoundlanders. As the fishery staggers and the outports empty, the music that celebrates the heroic people of the sea is arguably the only place where this identity survives. Attempts to remain a distinct society and not just another Canadian province have unfailingly focused on the rugged land and harsh existence of Newfoundlanders as the elements that set this province apart. Both the tourist and music industries are prospering through their promotion of a universal toil that has become what Theodor Adorno would call a "fashionable misfortune" (58). Struggle and survival is the Newf-chic and Newfoundlanders who have never so much as jigged a cod can now claim affinity with their seafaring forebears. Overton would call such people "plastic Newfoundlander[s]" (9), while philosopher F.L. Jackson uses the term "Duckworth St. Baymen" (i.e., urban Newfoundlanders feigning rural wisdom) to describe those who "became experts on a way of life they barely knew" (Jackson 8). Such people are subtly but certainly mocked by folk singer Ron Hynes in "St. John’s Waltz," a song that disguises its scathing remarks with romantic notions and images.

10 Though Hynes is hardly a rock artist, he has certainly played a major role in the popularization of Newfoundland music. Hynes sings at times with that typical and peculiar nostalgia for the present that is found in many songs that seek to define a place. The song begins with an image of the St. John’s harbourfront at night — a more quaint and contented scene could not exist: "Oh the harbour lights are gleaming/And the evening’s still and dark/And the seagulls all are dreaming/Seagull dreams on Amherst Rock." The tempo of the song is that of a "rocker" — not in the head-thrashing, guitar-squealing sense of the word — this song is the type that inspires the listener to gently rock back and forth. Yet in the midst of this romantic revelry is an unsettling parallel barely perceptible through the pastoral poetics:Oh we’ve had our share of history

We’ve seen nations come and go

We’ve seen battles rage over land and stage

Four hundred years and more

For glory or for freedom

For country or for king

Or for money or fame but there are no names

On the graves where men lie sleeping

All the nine to fives survive the day

With a sigh and a dose of salts

And they’re parkin’ their cars and their packin’ the bars

Dancin’ the St. John’s Waltz.

The petty problems of the nine-to-fiver would appear to have little in common with the tribulations of those who have died fighting for this nation/colony/province. Nor do they resemble the day-to-day existence of the fishermen and sailors who glide into the harbour in the first verse. Yet here are the urban-based office workers, shoulder to shoulder with the soldiers and seamen. While any sense of kinship between the modern-day working stiff and the glorified doryman seems absurd, it is a

stretch that is commonly made when establishing a sense of place. Daniel J. Boorstin uses the American example of the "Great Men" who fathered and fostered that nation: "We revere [these Great Men], not because they possess charisma, divine favor, a grace or talent granted them by God, but because they embody popular virtues. We admire them, not because they reveal God, but because they reveal and elevate ourselves" (50). When faced with "Newfie jokes" and an ever-diminishing sense of control over local affairs and resources, it is comforting to know that Newfoundlanders are the descendants of heroes — "Great Men" who were great because they overcame and endured. As the progeny of such stalwart settlers, Newfoundlanders should realize that their culture is not so much a leisure to be enjoyed as it is a force to be joined.

11 At least this seems to be the notion in most pop culture industries throughout the province. Local bands not only sing about past glories, but actually derive their names from past tragedies. Beaumont Hamel, a St. John’s-based heavy metal band, takes its moniker from the location in France where 272 members of the Newfoundland Royal Regiment were slaughtered during World War I. The name has come to identify Newfoundlanders not only through their sacrifice, but through their abuse at the hands of the British who usually ignored their colonial subjects until they proved useful as cannon fodder.

12 The spirit of the Fighting Newfoundlander inhabits the music industry far beyond the name of an upstart rock group. Over the years the image of the fisherman has been effectively merged with the notions of the Fighting Newfoundlander and the entertainer to create the ultimate personification of "Newfoundlandness." When it was first published in 1902, Cavendish Boyle’s "Ode to Newfoundland" had on its cover the image of a fisherman and a Royal Naval Reserve officer bearing the unfurled and overlapping flags of Britain and Newfoundland. In the background behind and above the sailor, a warship in full regalia steams through open water. In the opposite corner sealers have disembarked from their wooden ship and are carrying out their trade on a plane of ice. The inference is obvious: these men are warriors, and both risk their lives for the safety and well-being of this island. These men are not juxtaposed, but conflated, their flags and their worlds merge into each other.

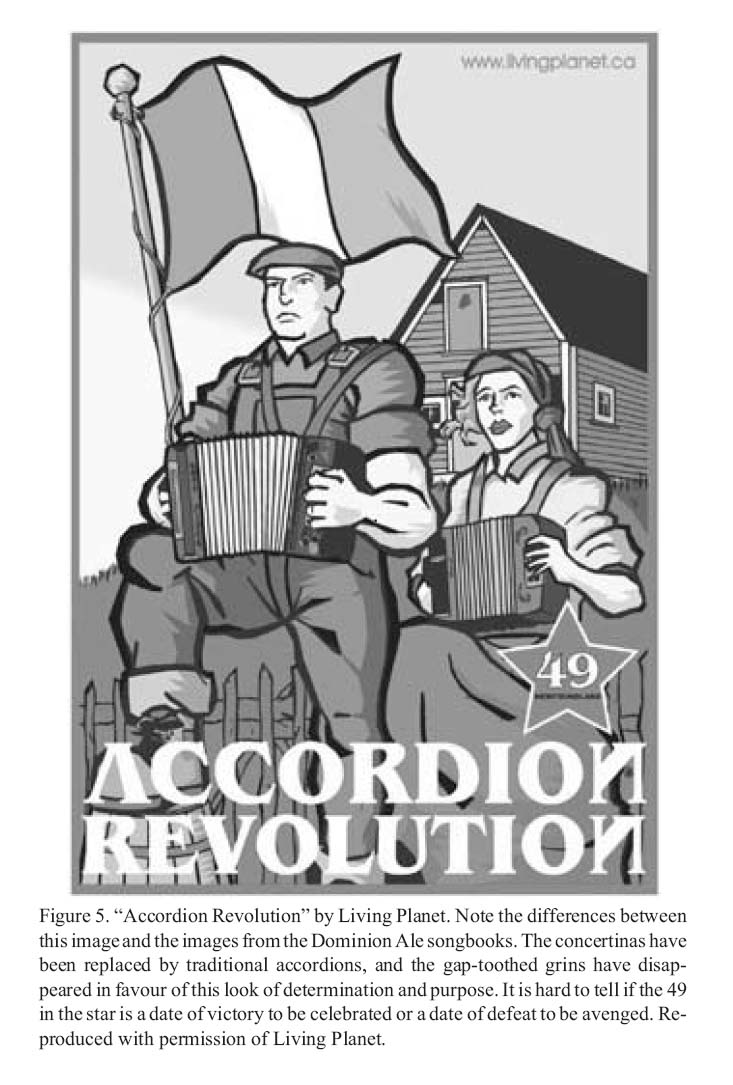

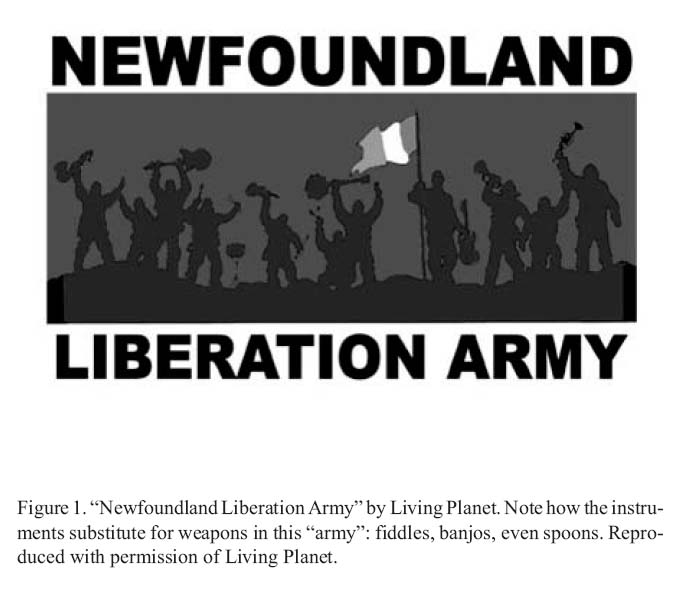

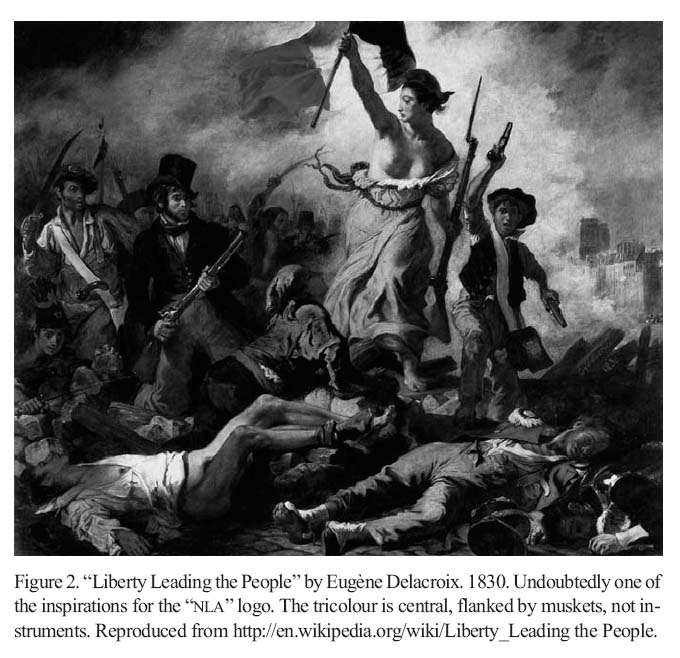

13 Living Planet, a purveyor of patriotic garb in the St. John’s shopping district (also dubbed the "heritage district" by the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador) counts among its bestsellers a shirt which sports the name and logo of the "Newfoundland Liberation Army" (Figure 1). The design depicts eleven silhouetted figures cresting a horizon of blood red sky meeting rocky earth. In the spirit of Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (Figure 2), the leader of the pack carries the unfurled flag of the Republic — not the blue, white, and red of France, but the vertical pink, white, and green bars of the old Newfoundland flag. In Delacroix’s painting, the feminine personification of liberty carries in her other hand a rifle with bayonet — the flag bearer of the Newfoundland Liberation Army carries a guitar. In the upraised arms of the other Newfoundland insurgents are saxophones, trumpets, banjos, and fiddles — one member of this musical mob proudly brandishes a set of spoons. The design is very much in the spirit of a "people’s uprising" — a guerrilla force of singing Sandinistas bravely battling tyranny. Through this mixture of the militaristic and the musical one can sense that the arts have become the real weapon of independence on this island. Here the Newfoundland "come all ye" becomes a more forceful "Musicians of the island unite!" It is an image remarkably and no doubt purposefully similar to posters calling for violent revolution. The symbol has proven rather vogue, appearing not just on T-shirts, but on tight-fitting bellytops (for the sexy socialist), and retro-style three-quarter-length T-shirts àla the Mötley Crüe and Def Leppard shirts so popular in the 1980s. The shirt has become one of the province’s biggest exports — favoured by trend-seekers and intellectuals alike. Judging by the number of people wearing this T-shirt, one would think that the attitudes of Newfoundland nationalism are so widespread that the government is in danger of being overthrown any day. Yet Living Planet’s on-line description of their product reminds us not to take the message too seriously. The design supposedly "expresses the ‘revolutionary’ sensibilities of many Newfoundlanders" — the well-placed quotation marks deflating not only the "revolutionary" potential of the piece, but also its "bold"ness. Such an ironic stance, coupled with the fact that this logo also appears on the backside of underwear, reminds us that the "Newfoundland Liberation Army" is more play than protest — more cheek than Ché.

Figure 1. "Newfoundland Liberation Army" by Living Planet. Note how the instruments substitute for weapons in this "army": fiddles, banjos, even spoons

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

14 The singing-soldier-of-heritage idea is also conveyed through a poster distributed by Scop Productions challenging the "Government to measure the arts funding budget against the annual revenues generated for the province by writers, artists, musicians and actors." The Pink, White, and Green is once again present — but this time appears to have been spray-painted onto the poster. The words "Quantify It" appear at the top of the sign in that bold stencilled script usually reserved for military cargo. This particular presentation, combined with the appearance of the poster on telephone poles and university bulletin boards, gives the entire message the aura of an undertrod urban proletariat carving out their censored messages on the walls of the city.

15 This sense of irony pervades the popular and musical culture, seemingly tempering the more serious and insurrectionary sentiments. The liner notes for Great Big Sea’s Up claim that "Lukey’s Boat"— that song of bliss in the midst of hardship — "is from the ‘ironic detachment’ school of local songs" (Hallett). Adorno uses a similar term when he reconsiders the culture industry. According to Adorno, a sense of "ironic toleration" prevails among those trying to find a place either inside or outside a supposed "culture": After all, those intellectuals maintain, everyone knows what pocket novels, films off the rack, family television shows rolled out into serials and hit parades, advice to the lovelorn and horoscope columns are all about. All of this, however, is harmless according to them, even democratic since it responds to a demand, albeit a stimulated one. (Adorno 89)The pop/folk culture industry of "fundraisers" for tradition and "Free Nfld" boxer-briefs both propagate and stimulate the "demand" for ardent and antagonistic heritage. Songs that rekindle Newfoundland’s feelings of indignation and isolation as well as logos that allude to an underground cultural movement literally and figuratively draw out Newfoundland’s history of loss and oppression. A culture that focuses on the problems of our past is a culture on life support — why else would it need a "fundraiser"?

16 In a conference paper (2002) for a symposium on "The Idea of Newfoundland," Jerry Bannister noted that Newfoundlanders’ obsession with their noble and tragic past may simply stem from the fact that it is easier to sing, bemoan, and valorize our past than it is to deal with our present. Adorno would agree with him. According to Adorno, "pseudo-activities" such as the presentation and performance of our culture are "spurious and illusory activities" (168) which provide a distraction for people who have a "dim suspicion of how hard it would be to throw off the yoke that weighs upon them" (168). In this light, "A Fundraiser for Culture & Tradition" may be little more than a "staged marginality" (Huggan 87), a well-planned performance that has the appearance of what Graham Huggan would call an "ethnographic salvage" (43). Presented with the daunting task of improving the lot of this province, most of us prefer to be an audience to the easier task of preserving and modernizing our folksongs than to become an active player in the more difficult undertaking of economic and industrial renewal. As an audience to these cultural events, we remove ourselves even further from meaningful activity — performers who tell us to "be quiet" while they busy themselves "preserving" our culture truly take the folk out of folk music. As Adorno writes, such prepared performances are "more concerned with instructing the listener about the event he is about to witness and the powers that have staged it than about encouraging him to participate in the work itself" (70).

17 Though many of us may subscribe to Hallett’s belief that all this "insurgency" must be taken with a little bit of "ironic detachment," this pseudo-oppression, even if only partially believed, still permits performers and artists to re-enter and revamp Newfoundland culture. As rock rebellion meets folk preservation, the new rock idol becomes an amalgamation of all the old tropes — fighting Newfoundlander, hardy fisherman, warrior-poet. As Boorstin notes, in worshipping this idol we are worshipping ourselves. This idol is in truth "a ‘nationally advertised’ brand" (Boorstin 49) and we can actively buy back our culture through the purchasing of shirts we can wear to the next great moment of culture. Adorno warns against the false feelings of betterment that accompany such cultural revivals in The Culture Industry:What parades as progress in the culture industry, as the incessantly new which it offers up, remains the disguise for an eternal sameness; everywhere the changes mask a skeleton which has changed just a little as the profit motive itself since the time it first gained its predominance over culture. (87)The culture industry offers only the illusion of change. Yet it is the recent shift in illusions that is the greatest source of hope for Newfoundlanders.

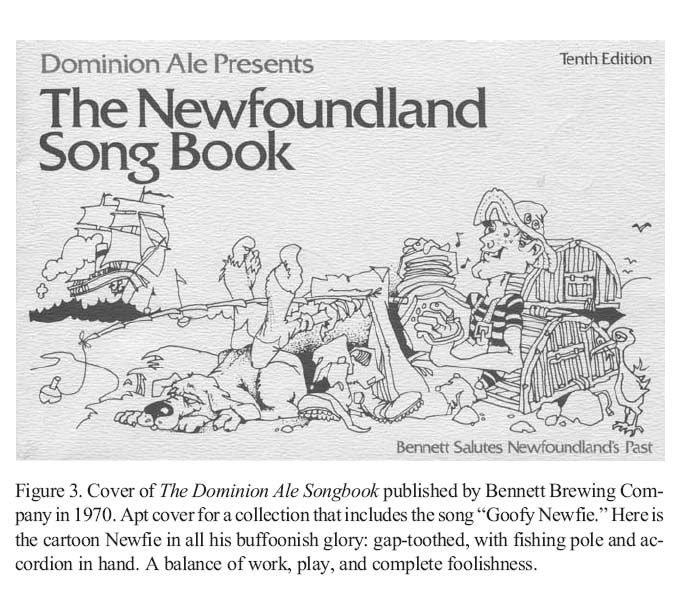

18 The fusion of folk and rock has modernized the token Newfoundlander. In the reactionary and revolutionary world of rock’n’roll there is no room for the self-deprecating jokes once so popular on this island. Perusals of songbooks distributed by Dominion Ale in the 1970s reveal how much times have changed. The tenth edition of The Newfoundland Song Book adorned as it is with the loveable fisher-trope (Figure 3) — gap-toothed, appropriately "hove off" on lobster pots, accordion and fishing pole in hand, toes protruding from holes in socks — contains the song "Goofie Newfie" by Roy Payne. Though the verses convey a frustration at being the "victims" of "stupid jokes," the chorus seems to suggest a willingness to play along with this image concocted by "the mainlanders":So go on call us goofie Newfies

Laugh aloud when you hear us speak

We’ll just sit back and enjoy liven

And chug-a-lug that good old Newfie Screech

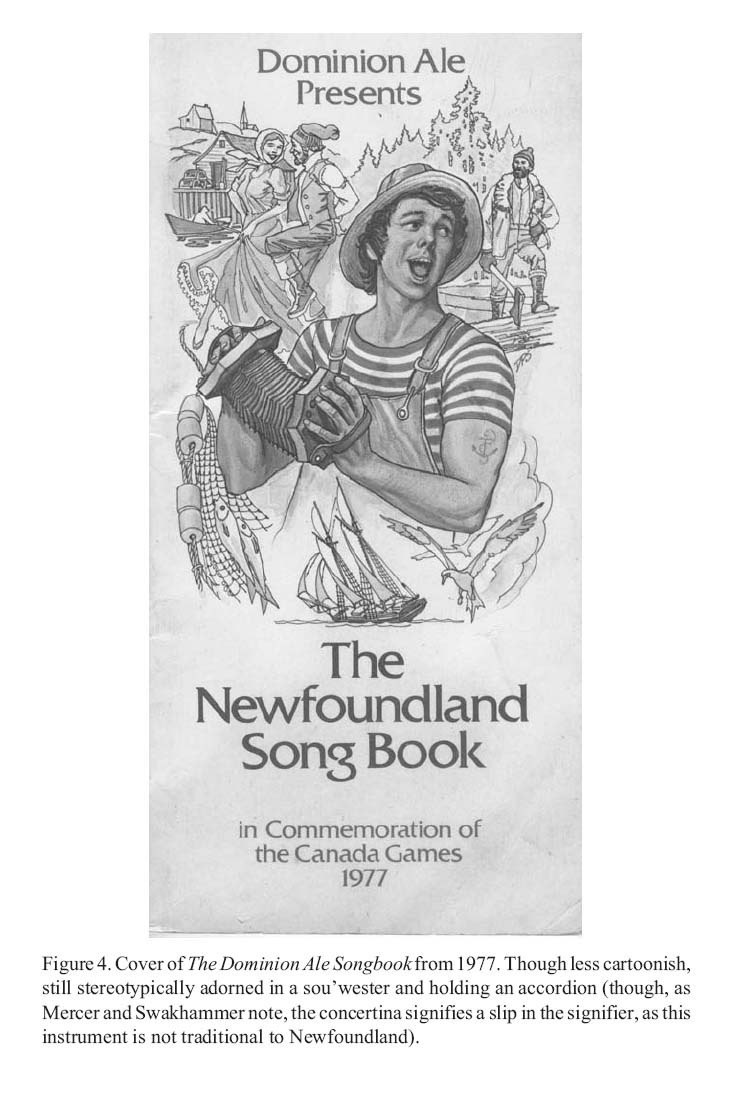

The 1977 version of the same collection (Figure 4) presents what folklorists Paul Mercer and Mac Swackhammer call "a much more sympathetic treatment of the same themes," though neither fisherman’s concertina nor his overalls "are traditional for Newfoundland" (42). Though the covers read "Dominion Ale Presents," these collections are actually produced by the mainland-based Bennett Brewing company and present what Mercer and Swackhammer contend are "mainland conceptions of Newfie-ism designed to sell beer" amounting to little more than "a visual Newfie joke" (41, 42).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

19 These songbooks were part of a campaign that included television commercials of bearded men in work clothes partaking in "traditional" Newfoundland activities or re-enacting significant moments from Newfoundland’s history and folklore. These men were at once a source of pride and humour. This touch of humour, this ever-present trait of being funny, is put to interesting and perhaps even covert use in recent depictions of Newfoundlandness.

20 Living Planet’s "Accordion Revolution" is the next in a long line of images converting fisherfolk into catch-all containers of Newfoundland culture and identity (Figure 5). The grin of the Goofy Newfie is replaced by a grim glare of purpose; the out-of-place concertina is replaced with a more accurate depiction of the button accordion. Above all flies the proud Pink, White, and Green. Yet, like the Dominion Ale depictions of dress and traditions that are more Québecois than Newfoundland, there is something decidedly not Newfoundland about this very Newfoundland image. The "A" and the "N"s of the slogan look particularly Russian. The red star with "49 Newfoundland" in the bottom right corner looks like a communist commemoration of a day of revolution — or a day of defeat. And the grey-clad labourer with his sleeves rolled to the überbiceps is more reminiscent of the uprising worker in socialist propaganda posters than the Newfoundland fisherman. The far-off stare of the couple is the same stare shared by labourers and soldiers in countless socialist posters. Yet it is the accordion that seems to both drive and de-fuse the situation, to separate this call to action from more serious revolutionary propaganda. In this instance, the accordion as icon represents both the proud musical heritage of Newfoundlanders and their humour. Whereas most socialist propaganda tells the labourer to put down his tools and pick up his gun, the "Accordion Revolution," like the "Newfoundland Liberation Army," demands Newfoundlanders to arm themselves with instruments.

21 The "hybrid product" that is contemporary Newfoundland folk-rock is more concerned with songs of a proud and powerful position. "The Band Played Waltzing Matilda" or "Those Warlike Lads of Russia" have as much a chance of being played at any "Newfoundland" folk performance as does "The Islander." The point: apparently Newfoundland folk music is no longer a place for "laughing at ourselves" but a place for aligning our proud heritage with other uncompromising and unbreakable cultural moments. The "formation" of the Newfoundland Liberation Army, even if it is tongue-in-cheek, and the singing of revolutionary songs, even if they are not ours, still threaten to foster what Asha Varadharajan calls a "predestined frustration" (21) — a self-fulfilling quest for oppression and angst. Yet, modern versions of traditional songs and icons like the "Accordion Revolution" represent a conflation, rereading, reorganization, and revitalization of Newfoundland culture and history. The result is an active and evolving identity — an identity that is continually challenged and transformed but never defeatist.

Figure 5. "Accordion Revolution" by Living Planet. Note the differences between this image and the images from the Dominion Ale songbooks. The concertinas have been replaced by traditional accordions, and the gap-toothed grins have disappeared in favour of this look of determination and purpose. It is hard to tell if the 49 in the star is a date of victory to be celebrated or a date of defeat to be avenged Reproduced with permission of Living Planet.Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W. The Culture Industry. Ed. J.M. Bernstein. 1968. London: Routledge, 1991.

Andrews, Chris and Mark Hiscock. "I’se Da Bye." Traditional, arranged by Andrews and Hiscock. Shanneyganock. Live at O’Reilly’s Volume I. 1998. Item no. 29927.

———. "The Islander." By Bruce Moss. Live at O’Reilly’s Volume I. 1998.

Bannister, Jerry. "Whigs and Nationalists: The Legacy of Judge Prowse’s History of Newfoundland." Unedited paper, 2002.

———. "The Politics of Cultural Memory: Themes in the History of Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada, 1972-2003." Collected Papers of the Royal Commission on Renewing and Strengthening our Place in Canada. St. John’s: Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2003. 119-166.

Bhabha, Homi K. "DissemiNation: Time, Narrative and the Margins of the Modern Nation." Nation and Narration. Ed. Homi K. Bhabha. London: Routledge, 1990.

Boorstin, Daniel J. The Image, or What Happened to the American Dream. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1961.

Great Big Sea. "Lukey." Traditional, arranged by Great Big Sea. Up. Scarborough, ON: WEA Distributed by Warner Music Canada, 1995. Issue no. CD 12277 WEA.

Huggan, Graham. The Post-Colonial Exotic: Marketing the Margins. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Hallett, Bob. Liner Notes. Up. 1995. Great Big Sea. Up. Scarborough, ON: WEA. Distributed by Warner Music Canada, 1995. Issue no. CD 12277 WEA.

Hynes, Ron, "The St. John’s Waltz." Face to the Gale. Mississauga, ON: Artisan Music. Distributed by EMI Music Canada, 1997. Issue no. 72438 36187 2 9.

Jackson, F.L. Surviving Confederation. St. John’s: Harry Cuff Publications, 1986.

Jameson, Frederic. Postmodernism: or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke UP, 1999.

Johnston, Wayne. The Colony of Unrequited Dreams. Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998.

Mercer, Paul and Mac Swackhammer. "The Singing of Old Newfoundland Ballads and a Cool Glass of Beer Go Hand in Hand." Culture & Tradition 3 (1978): 36-45.

Overton, James. "A Newfoundland Culture?" Journal of Canadian Studies 23 (1988): 5-22.

Payne, Roy. "Goofie Newfie." The Newfoundland Song Book. Dominion Ale, 1977.

Prowse, D.W. A History of Newfoundland From the English, Colonial and Foreign Records. 1895. Reprinted in facsimile, Portugal Cove: Boulder Publications, 2002.

Varadharajan, Asha. Exotic Parodies: Subjectivity in Adorno, Said, and Spivak. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1995.

Notes