Kenneth Peacock’s Contribution to Gerald S. Doyle’s Old-Time Songs of Newfoundland (1955)1

Anna Kearney GuignéMemorial University

ak-guigne@nl.rogers.com

INTRODUCTION

1 IN 1965, AFTER TEN YEARS of folksong research in Newfoundland, the classical musician and composer Kenneth Peacock (1922-2000) released a three-volume collection, Songs of the Newfoundland Outports, with 500 songs and variants, and a wide range of song material derived from the British, Irish, Canadian, French, and American traditions as well as several locally composed songs. It showed the strength and vitality of Newfoundland’s musical tradition as Peacock saw it, based on his field collecting in the 1950s and early 1960s on behalf of the National Museum of Canada (Guigné 2004). In this work, Peacock paid a small tribute to St. John’s businessman Gerald S. Doyle (1891-1956), remarking that he had been "more responsible than anyone else for making people aware of Newfoundland folksongs" (1, xxi).2 Alluding to Doyle’s popular songsters Old-Time Songs and Poetry of Newfoundland (1927, 1940) and Old-Time Songs of Newfoundland (1955), Peacock added, "though the value of his collection cannot be overestimated, its wide dissemination on the mainland has created the impression that Newfoundland folksongs consist entirely of locally composed material." By publishing Outports he hoped to "correct that erroneous impression" (xxi).

2 Peacock had a singular understanding of Doyle’s impact on the popularization of a select number of folksongs. Almost half of the 1955 songster, which Doyle published shortly before his death, was comprised of material Peacock himself had collected in 1951 during his first year of fieldwork in Newfoundland. Although Doyle acknowledged Peacock as a contributor to this particular edition, little is known of the extent to which he drew on this collector for new material (1955a, 7). Even less has been written about the interaction between the two. This essay clarifies their mutually constitutive social roles. I consider Peacock’s influence on the 1955 songster and Doyle’s impact on Peacock’s publication strategies.

THE DOYLE SONGSTERS AND FOLKSONG SCHOLARSHIP IN NEWFOUNDLAND 1927-1950

3 Gerald S. Doyle was a native of King’s Cove, Bonavista Bay, with strong Irish-Catholic roots. Moving to St. John’s at an early age, in 1919 he founded a highly successful business retailing pharmaceutical and household products and his own brand of cod liver oil. Doyle was a marketing innovator with a populist touch. In 1924, he launched The Family Fireside, a free newspaper filled with local news, poetry, and updates on community activities alongside advertisements for his products. In 1932, he initiated The Gerald S. Doyle News Bulletin, which aired over VONF radio. The program, the broadcast equivalent of the newspaper, combined a community message service with commercials for his products, and was popular for over 34 years.3

4 Doyle became a familiar figure to thousands by travelling regularly to the out-ports each summer to meet customers face to face. At first he leased vessels, and, then, in the 1930s he purchased his own boat, naming it Miss Newfoundland.4 These ventures provided Doyle with the opportunity to distribute products and to socialize. He met numerous singers, inviting them on board for an evening of song and a drink. Between 1927 and 1955, Doyle also released his three paperback songsters. These too were distributed free across Newfoundland. True to form, he alternated songs with advertisements for Doyle products.

5 Doyle’s business activities were linked to his fervent nationalism.5 He was passionate about Newfoundland’s position as a country unto its own and on the importance of the outport economy. Although he was keenly aware of the richness of the British, Scottish, French, and Irish folksong tradition in Newfoundland, he chose to emphasize locally composed songs (Rosenberg 1991, 45-57). These he considered to be "true Newfoundland songs"; all others were viewed as "importations" (Doyle 1955a, 31). These true (i.e., local) folksongs, Doyle noted, were recognizable by the "rollicking swing and tempo, the grand vein of humour" and their description of the Newfoundland "way of life" (31). By the late 1940s, songs such as "Kelligrews Soiree" and "Ryans and the Pittmans," which appeared in all three editions, were well on their way to becoming the most commonly known songs, "creating a popular song canon for Newfoundland" (Rosenberg 1991, 46).

6 For the 1927 edition, Doyle initially drew from the thriving broadside tradition extant in St. John’s at the early part of the twentieth century (Mercer 1979). By 1940, when he issued the second songster, a new thrust in folksong collecting had occurred. In 1920 and 1921, Elizabeth Bristol Greenleaf (1895-1980), a young volunteer teacher from New York, visited the Great Northern Peninsula to work for the Grenfell Mission. There she heard traditional songs and began to collect them.6 In 1929, Greenleaf returned to Newfoundland with musician Grace Mansfield on a "folklore expedition" funded by Vassar College for the express purpose of collecting folksongs (Greenleaf 23-25). They subsequently published Ballads and Sea Songs of Newfoundland (1933), with 200 songs. In 1929 and 1930, the English collector Maud Karpeles (1886-1976) also arrived in Newfoundland to collect folksongs. Guided by her mentor Cecil Sharp (1859-1924) and his theories of authenticity, she sought material of British origin (Lovelace 2004, 285-299). Despite her narrow perspective, Karpeles successfully acquired almost 200 songs, publishing 30 of them in Folksongs from Newfoundland (1934), a two-volume collection with pianoforte arrangements by Ralph Vaughan Williams, Clive Carey, Hubert Foss, and Michael Mullinar.7 Although the collecting styles of these women differed, both publications encouraged Newfoundlanders to take a new interest in their own folk culture (Emerson 1937, 234-238).

7 Doyle was apprised of this research. He had facilitated Karpeles’s activities, providing her with at least one letter of introduction to Mrs. Burdock of Belleoram on the South Coast.8 Greenleaf, who had documented singers performing several songs from the 1927 songster, also communicated with Doyle, seeking permission to publish these and other songs from his songster in Ballads and Sea Songs.9 Doyle was sufficiently impressed with Greenleaf and Mansfield’s use of musical transcriptions that he subsequently drew upon their work for the 1940 songster; fourteen of the 25 new songs in this publication came from Ballads and Sea Songs (Rosenberg and Guigné 2004, xix). Doyle also published their transcriptions for the songs they had recorded in 1929 from singers who had learned them from his 1927 songster. The addition of the melodies along with the texts in the 1940 edition started the process of establishing a standard melodic form.

8 As a marketer, Doyle appreciated that fresh songs whetted his customers’ appetite both for the publications and his products.10 He therefore retained pieces from earlier editions which he felt were more popular. Others of less interest were left out. This marketing method was highly effective; the songsters solidified Doyle’s role both as an inventive merchant and an amateur collector of Newfoundland folksongs.

9 By the late 1940s the Doyle songs, already well publicized in Newfoundland, gained in popularity in mainland Canada, eventually drawing interest from Canadian revivalists. During World War II when soldiers were stationed on the island, it was Doyle’s brand of Newfoundland folksong that was presented to Canadians both through his songsters and by way of radio and record (Hiscock 1988, 41-59). Following the war period, a wave of Canadian nationalism led mainland musicians to collect and study Newfoundland folksong. It was their awareness of the work of Maud Karpeles and the Doyle songsters which drew Toronto musicians Leslie Bell and Howard Cable to Newfoundland in 1947.11 As an educator, Bell was primarily interested in obtaining new material for songbooks he was preparing for the Ontario College of Education. The Doyle songsters were viewed as an essential source.

10 Upon arriving in St. John’s they teamed up with musician Robert (Bob) Macleod (1908-1982).12 During the 1920s and 1930s, Macleod had already developed a reputation as a noted pianist and organist and by this time was regularly performing Doyle’s folksongs in and around St. John’s. Macleod had also accompanied Doyle on several collecting trips around Newfoundland on the Miss Newfoundland; Doyle acknowledges his assistance in the preparation of the 1940 songster (1940, 1).

11 Bell and Cable spent most of their time with Macleod and it was the Doyle songs that he performed for them. They, in turn, converted this music into a series of classical arrangements. Throughout the late 1940s, Cable and Bell’s Newfoundland-based compositions gained extensive exposure on radio. Just months after they returned from Newfoundland, Bell’s choral group, the Leslie Bell Singers, performed an arrangement of "I’se the B’y" on a CBC musical entertainment series.13 This was one of several songs Macleod had given them during their stay in Newfoundland (Rosenberg 1994, 59).

12 Cable and Bell’s arrival in Newfoundland was partially linked to the burgeoning interest in Canadian folksong which emerged from a broad-based "folk revival boom" with roots in the United States, Canada, and Great Britain (Rosenberg 1993). Throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, as part of this revival, a mass market for Canadian folk music emerged primarily through the dissemination of this music by way of radio, records, and print (Guigné 2004). This revival was directly linked to a rise in Canadian nationalism; folksongs were deemed to be part of Canada’s heritage as distinct from that of the United States.14

13 As Taft points out, Doyle’s ideals, although focused on highlighting the significance of Newfoundland material, also had much in common with other revivalists of the period (1975, xiv). In the 1940s, he helped nurture a growing popular market for Newfoundland songs. As an extension of his interests in promoting Newfoundland folk music, Doyle became involved in financing the creation of records of Newfoundland music. In 1943, he provided the monetary support for Arthur Scammell (1913-1985), a native of Change Islands, to record his composition "The Squid Jiggin’ Ground" under the RCA label. It was a commercial success both in Newfoundland and the mainland, going all the way to the hit parade (Taft 1975, xiii; Rosenberg 1994, 60). As Taft notes, through the arrangement between Doyle and Scammell, a "traditionally composed song" had been turned into "a commercially-successful recording" (1975, xiii). The popularization of a select number of locally composed songs taken from the Doyle songsters and then aired over the radio, and by way of records, became for many Canadians the quintessence of Newfoundland music. It was these songs, among others, which main-land Canadian folk revivalists drew upon during the early stages of their own folk revival.

14 A typical example is Canadian folksinger Alan Mills (1913-1977) who, in 1947 launched a new program, Folksongs for Young Folk,on CBC. By 1948, Mills was performing Newfoundland folksongs from the Doyle songbook on air for Canadians. Newfoundlanders also had access to this show through shortwave radio ("Folksongs and Yarns"). In 1953, having become affiliated with the American-based Folkways Records, he also created Folksongs of Newfoundland (6831), performing such songs as "Jack Was Every Inch a Sailor," "The Badger Drive," and "Lukey’s Boat," taken from Doyle’s songbooks. Throughout the 1950s, the Doyle material was a key source for other Folkways albums and a publication of Newfoundland folksongs (Mills 1958).

THE NATIONAL MUSEUM AND THE DOYLE SONGSTER CONNECTION

15 By the late 1940s, Newfoundland was seen as a key destination for folksong collecting. Stimulated by Greenleaf and Mansfield’s Ballads and Sea Songs, the American ballad scholar MacEdward Leach (1892-1967) visited the province in 1950, 1951, and 1960 (Coffin 434). Although he collected over 500 songs and instrumental numbers in the first two years, little of this material was published until several years later.15

16 One year after Newfoundland’s union with Canada, the National Museum of Canada also sent musician Margaret Sargent (McTaggart) (1921- ) on an exploratory mission.16 The Museum’s interest in Newfoundland was in part stimulated by a revival of interest in Canadian folksong and the reality that its collections of folk music were badly outdated (Guigné 2004). Mainly through anthropologist Marius Barbeau (1883-1969),17 this institution had been in the business of recording folk and First Nations music for some time, but the material had been gathered on wax cylinders and was deteriorating (Sargent 1951, 75-79). Although retired, Barbeau was still connected to the Museum and had secured funding to hire Sargent to transfer the cylinders to a new medium called magnetic tape so the material could be transcribed (Sargent 1950, 175-180). Despite the work Helen Creighton (1899-1989) had been doing in Nova Scotia, the balance of the Museum’s collections consisted mainly of French and Aboriginal music; the Anglophone material was, by comparison, negligible.18 As Sargent pointed out, because of the recent demand for Canadian folksongs, the field trips to Newfoundland were a way of addressing this issue.

17 Sargent arrived in Newfoundland in June 1950, and spent the first phase of her fieldwork in St. John’s. While in the city, she too was directed to see people within the Doyle network. She eventually met Bob Macleod, and recorded several songs from him. Most of them had been previously published in the Doyle songsters (Blouin 1982). Sargent then made her way to Branch and St. Bride’s on the southwest coast of the Avalon Peninsula, 130 miles from St. John’s. Here she encountered solo singers performing a cappella. Her experiences point to the co-existence of two distinct styles of performance practice at this particular time period. One is best described as a popularized St. John’s presentation of Newfoundland folksong, particularly those in the Doyle songsters. The other, an older one, is where singers learn their songs from a broad rural repertoire of folksong influenced by such factors as family connections, occupation, settlement patterns, and community networks; they perform them without accompaniment.

18 Upon returning to Ottawa, Sargent resigned from the Museum and headed off to British Columbia. Due to time constraints she was unable to publish anything from her Newfoundland visit. Sufficiently impressed with her findings, Barbeau pushed the Museum to continue the field program. At Sargent’s recommendation, and with Barbeau’s support, Kenneth Peacock was offered a summer contract to visit the province in 1951 (Guigné 2004).19 Peacock saw the offer as a summer stopgap between teaching and composing. So he took on the job.

PEACOCK’S 1951 FIELD TRIP20

19 In June 1951, with one of the Museum’s new Soundmirror tape recorders in hand, Peacock set out for Newfoundland, arriving in St. John’s several days later. One evening he ended up at the Old Colony Club, a popular upscale establishment. By chance, he met lawyer Lloyd Soper, a friend of Doyle’s, who happened to be there singing folksongs for friends.21 As Doyle was out of the city at the time, Peacock asked Soper if he might interview him. The next day they met in Soper’s office in downtown St. John’s, where Peacock recorded him singing the "H’emmer Jane," a humorous parody of more serious sea disasters, which Soper performed with an exaggerated Newfoundland accent. Soper also sang "Feller from Fortune," and "I’se the B’y." He had learned all three songs from Bob Macleod.22

20 To Peacock, Soper’s performances of all three songs were really a "St. John’s interpretation of outport culture."23 He was more interested in acquiring material from singers in the outports where friends might gather to sing generally unaccompanied and individually. Soper also made a distinction between the St. John’s and outport performances, later noting "I think this was the interesting thing about it because [Peacock] would be getting people to sing the folksongs without any accompaniment and in the true style of the folksong."

21 Probably at Soper’s suggestion, Peacock headed down the Southern Shore in search of something which he deemed to be more authentic. He eventually ended up in Cape Broyle, securing a place with the local merchant, Ron O’Brien, who introduced him to Ned (Edward) Rice (age 35 at the time), and his father Jim Rice (1878-1958). Peacock recorded several songs from Ned Rice, including "Daniel Monroe," "Loss of the Titanic," and a version of Arthur Scammell’s "The Six Horse Power Coaker," as well as two locally composed songs about the war, "Hitler’s Song" and "Our Boys Gave Up Squidding." From Jim Rice he recorded a locally composed song about the St. John’s sealing fleet and their captains called "Old Sailing Fleet (Captains and Ships)," and an Irish number "The Big Roaring Fire." Ron O’Brien and Ned Rice also sang "The Star of Logy Bay" and "Molly Bawn." Peacock was introduced to their neighbour, Mike Kent (1904-1997), recording from him "Give an Honest Irish Man a Chance," the Child ballad, "Lady Margaret" (4-23) (No. 77), "Wexford Girl," "My Old Dudeen," and "Thomas and Nancy."24

22 Peacock was excited by the range of music, which included British broadsides, Child ballads, and many locally composed songs outside of the Doyle canon. Although the performance style differed from Soper’s, some Doyle repertoire (from the 1940 songster) — "The Star of Logy Bay" and Scammell’s "Six Horse Power Coaker" — was shared with Peacock, along with "Our Boys Gave Up Squidding," a locally composed war song based on the textual and melodic structure of Scammell’s "The Squid Jiggin’ Ground."

23 Peacock next headed down the Burin Peninsula to Grand Bank; here he met Ewart Vallis, a young local singer, who accompanied himself on the guitar.25 Vallis had begun to make a name for himself singing and performing on VOCM radio’s Barn Dance, a program which incorporated country, Newfoundland, and Irish music.26 Peacock recorded just two numbers from this singer: "The Roving Newfoundlanders," which Vallis had learned from the 1940 Doyle songster, and "Feller from Burgeo," a variant of "Feller from Fortune. " Although Peacock disliked Vallis’s decidedly country and western style of singing and guitar playing, this singer actually typified many rural musicians who regularly used the radio as a source for their music, tuning in to mainland stations to hear such favourite singers as Wilf Carter and Hank Snow (Taft 1974, 99-120).

24 Peacock next made his way to Bonavista Bay, stopping first in King’s Cove.27 As the community lacked electricity, on the spot he transcribed the songs including the Child ballad "Bonny Banks of Vergie-O" (No. 14), performed by an elderly couple, Kenneth and Rebecca Monks, who had earlier sung it for Maud Karpeles (Karpeles 1934, II, 78-82 and 142 n.). He also spent time in Stock Cove working with the Heaney and Mahoney families. From James Heaney he collected "My Father’s Old Sou’wester." The influence of the popular media as a medium for disseminating songs was once again evident. This song was one of several written for the radio drama, Irene B. Mellon, which aired over VOGY radio (later to join VONF), a program that had much popular appeal (Hiscock 1991, 178).

25 In the town of Bonavista, he recorded innkeeper Harry Drover, who offered him a rendition of the "H’emmer Jane." Peacock later noted that he found it "so exaggerated."28 From Drover’s cleaning lady, Mrs. Venus Way, Peacock recorded the songs "Go and Leave Me if You Wish Love" and "The Spring of ’97," a song about a sealing tragedy. Peacock also encountered Stewart Little who sang "Bonavista Harbour," a satirical song that he had composed about the poor construction quality of a wharf in 1944 which entailed removing a hill of rock by a Canadian company.

26 Peacock returned to Cape Broyle and recorded several new songs from the Rices and Mike Kent. Peacock was also introduced to Rice’s daughter, Monica Rossiter (1913-2004), who sang mainly locally composed songs including "Dying Soldier" and "Prison of Newfoundland." Peacock wound up his field season by going to Ferryland where he met Howard Morry (1885-1972), a fisherman and sheep farmer, recording from him seventeen songs.

27 At the end of the summer, Peacock headed back to Ottawa. It was, by all accounts, a successful field trip; he had collected almost 70 songs on tape and an additional 30 or so in manuscript. Although Peacock preferred older material, and had a distaste for the influence of country and western music, he had also been able to provide tangible proof that Newfoundland music was much more diverse than had previously been represented through the Doyle material or other collections. The Newfoundland fieldwork, which eventually extended over a ten-year period, launched Peacock on a life-long career of documenting Canada’s traditional music on behalf of the National Museum of Canada.

THE DOYLE-PEACOCK CONNECTION

28 Early in 1952, Gerald S. Doyle approached the director of the National Museum for the use of Peacock’s material with a view to publishing another songster ("Here and There").29 Peacock was advised by the Museum to let Doyle have whatever he wanted. As Newfoundland was now part of Canada, it was a goodwill gesture. When they eventually met in Ottawa, Peacock played Doyle a number of field recordings and presented the Newfoundlander with his musical transcriptions. Peacock noted that Doyle was filled with emotion and "tears came to his eyes" when he heard Jim Rice singing several numbers. Despite the range of song material which Peacock had collected, it also struck him that Doyle was interested "almost entirely in locally composed songs; so that was his criterion."30 For Peacock, their meeting was a memorable experience.

29 Peacock gave Doyle a total of 30 songs from his 1951 field collection ("Here and There"). At Doyle’s request Peacock also prepared piano arrangements for them. In the end Doyle decided to publish only the melodies. Peacock speculates that cost might have been a factor.31 Three years later, Doyle published his third edition under the simpler title Old-Time Songs of Newfoundland. The songster was plainly bound in a light green cover. As a reminder of the province’s former status as a country, Doyle used an image of the island on the front cover and he also included Sir Cavendish Boyle’s "Ode to Newfoundland" (1955, 7). Several of the songs from Peacock appear to have been hastily included at the end of the index out of alphabetical order and almost as an afterthought. Doyle apparently published two versions: one with advertisements and one without, the latter for gifts to friends.32

30 In all, the 1955 songster contained 48 songs. Eight of these had appeared in both the 1927 and 1940 editions.33 Doyle had acquired seven more from Green-leaf and published them earlier in the 1940 edition (Rosenberg and Guigné xix).34 One song, "The Trinity Cake," had previously been published in 1927, but the melody was added to the 1955 edition, probably transcribed by Patricia Kielly, then engaged to Doyle’s son.35 Four remaining songs had also been published once before in 1940. These included Scammell’s "The Squid Jiggin’ Ground"; "Two Jinkers," now presumed to have been composed by Doyle’s uncle, P.K. Devine (1859-1950); "Tickle Cove Pond," now attributed to Mark Walker (1846-1924) (Hiscock 2002, 32-68); and "Great Big Sea Hove In Long Beach," which Doyle acquired from an unknown source. Several of the twenty songs which Doyle carried over, had been printed twice and/or recorded in the 1940s and were well on their way to constituting the Newfoundland folksong canon.

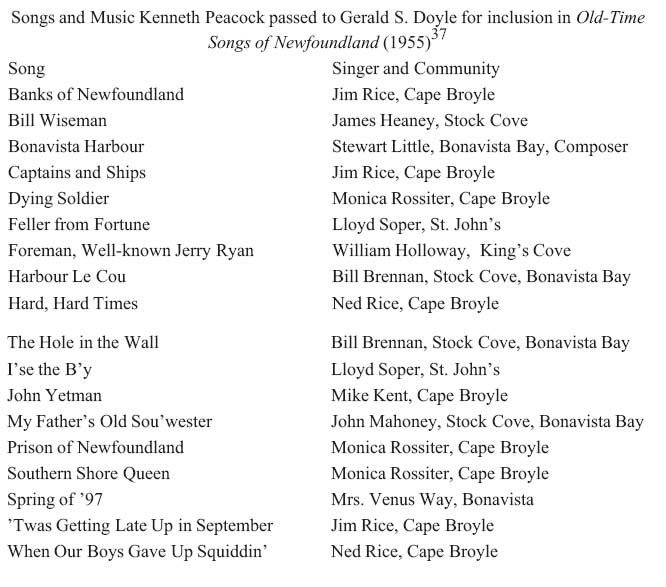

31 For the new material, in addition to the "Ode," Doyle drew on Greenleaf’s collection ("Crowd of Bold Sharemen," "Twin Lakes," and "Sally Brown"), local composers, and Peacock. Two new compositions, "Down by Jim Long’s Stage" and "Let Me Fish Off Cape St. Mary’s," are attributed to Mark Walker and Otto Kelland (1904-2003) of Lamaline, respectively. Doyle acquired "Old Polina" from Captain Peter Carter and Harry R. Burton of Greenspond (Fowke 1973, 195), and apparently composed two songs, "A Noble Fleet of Sealers" and "The Sealer’s Song," himself.36 The source for "When the Caplin Comes In" is unknown. The remaining eighteen songs were all provided by Kenneth Peacock as follows:

Songs and Music Kenneth Peacock passed to Gerald S. Doyle for inclusion in Old-Time Songs of Newfoundland (1955)37

Display large image of Table 1

Doyle also used Peacock’s melodies for "The Roving Newfoundlander(s)" and "Star of Logy Bay," combining them with the texts from the previous edition.38

THE DOYLE SONGSTER AND CONFEDERATION

32 Out of the 48 songs published in 1955, 28 plus two melodies came from collections made by non-Newfoundlanders. In this sense Doyle had made good use of the then-current folk music scholarship. Some preliminary observations can be made specifically regarding the Peacock-Doyle exchange. The themes contained in this new material often parallel that of the earlier editions (Rosenberg 1991, 48-49). Many of the songs Doyle selected fitted with his views of an idyllic Newfoundland culture featuring the sealing and cod fisheries: "Captains and Ships," "’Twas Getting Late Up in September," and "Banks of Newfoundland." Others, such as "When Our Boys Gave Up Squiddin’," were a reminder of Newfoundland’s participation in World War II when it was still a country (albeit under a Commission of Government) prior to joining Canada. Such comic songs as "The Hole in the Wall" and "Bill Wiseman" are consistent with Doyle’s views of socializing in outport Newfoundland. "Harbour Le Cou," "I’se the B’y," and "Feller from Fortune" were probably chosen because they fitted well with Doyle’s sense of true songs which had a "rollicking swing and tempo" (Doyle 1955a, 31).39 In the case of "I’se the B’y," although Macleod and Soper had both performed it, the song was commonly known in the St. John’s area and elsewhere (Hiscock 2005, 205-242).40 As is well documented now, these more upbeat numbers, when eventually disseminated beyond the shores of Newfoundland, by way of the Canadian folk revival, have contributed to the Canadian stereotype of Newfoundlanders as rather simple-minded (Rosenberg 1994, 64).

33 Rosenberg notes that in the 1940s Doyle was "suspicious of confederation with Canada" (1991, 56), perhaps because of the uncertainty of how such a union might affect his business dealings. Doyle had actively campaigned for a return to responsible government. Shortly before Newfoundlanders went to the polls on 22 July 1948 for the final vote, Doyle distributed a flyer in The Family Fireside with the banner "Vote to Save Not Sell Newfoundland," encouraging Newfoundlanders to consider the consequences.41 Doyle was also concerned about the future of The Doyle Bulletin which, in 1940, had an estimated listening audience of over 300,000 Newfoundlanders (Wesley 7-8). Following Confederation, VONF radio was turned over to the publicly funded Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. In an unprecedented move, the Bulletin was allowed to continue, even with its commercially sponsored status, due to the provincial popularity of the show. For Doyle this was conceivably a positive indication of the benefits of Confederation.

34 By the time the 1955 edition was released, the manner of doing business in Newfoundland had begun to shift dramatically. Export restrictions were eliminated.42 The early years of Confederation were also marked by a reorganization of the province’s infrastructure and a program of modernization that affected every aspect of life.43 Doyle, who continued to make annual visits around the island, was in a position to witness first-hand the post-Confederation changes. Throughout the early 1950s, he noted, in a series of annual reports, many improvements across the island in the form of new wharves, electricity in rural areas, increased school enrollment, and increased benefits for consumers ("1954. As Seen By Gerald S. Doyle," 5-8, 16, 18-23; Doyle 1955c, 5-7, 11-14, 40-48; Pumphrey 25-27).44

35 The arrival of the Canadian industrial economy in the post-war period also added to the breakdown of traditional social and economic patterns associated with the fisheries (Britan 153-165). Doyle, who had been a main distributer of products, now had to compete with the onslaught of new companies interested in Newfoundland consumers. The songsters, always popular with Newfoundlanders, gave him an added advantage. As the advertisements for the 1955 songster show, Doyle attempted to convey to customers in Newfoundland that they were just like other Canadians. He placed testimonials from Newfoundlanders who had benefited from such products as Dr. Chase’s Ointment alongside those of other Canadians who had tried it (1955a, 18). In the songster Newfoundlanders could read comments from other Canadians using the products he carried, as in the case of Mrs. Beatrice Huff of Winnipeg Street in Penticton, British Columbia, and Miss Elizabeth Klassen of Alberta who offered their remarks on the benefits of Paradol, now sold "coast to coast across Canada" (1955a, 61).

36 In publishing this third edition, Doyle was offering Canadians something that could bridge the gaps between Newfoundland culture and Canadian culture — Newfoundland folksongs. As one advertiser noted, "the privilege of participating in this publication is especially pleasing to us since we realize the rich heritage of melody and song to be found in Canada’s newest province" (1955a, 73). Folk music was seen as "a language that can knit" the Dominion together.

CANADIAN FOLK REVIVAL AND PEACOCK

37 In the ensuing years, through the wide distribution of this publication, songs such as "I’se the B’y," "Harbour Le Cou," and "Feller from Fortune," which Peacock had originally recorded and then passed back to Doyle, were to become part of a well-known body of songs in both the mainland Canadian and Newfoundland song traditions (Rosenberg 1994, 55-73). The popularization of this material is due partially to the revivalist activities of Museum workers such as Peacock and Barbeau and through their links to other popularizers, all of whom aimed to make Canadians aware of their musical traditions (Guigné 2004). Barbeau found an immediate use for Peacock’s field recordings, including Soper’s rendition of "Feller from Fortune," incorporating them, along with Ned Rice’s performance of "Daniel Monroe," into his Canadian Folksongs (SL-211, 1954), an album that he was preparing for the American folklorist, Alan Lomax, as volume eight in the Folk and Primitive Music series. Using the facilities of CBC Ottawa, Peacock later recorded himself singing songs he had collected, including "Foreman Well-known Jerry Ryan."45 Barbeau used this performance as well.

38 Peacock had also disseminated some of this material (of which the 1951 collection was a part) through a series of six CBC radio programs devoted to his collecting activities.46 In 1956, he created Ballads and Sea Songs of Newfoundland Sung By Ken Peacock (FG 3505), released under the Folkways label. Peacock also gave "I’se the B’y" and "Feller from Fortune" to Edith Fowke and Richard Johnston for their new compilation Folksongs of Canada (1954), a publication that was pivotal to the Canadian folk revival as much as it was to the popularization of a core of Newfoundland folksongs.47 In 1958, he collaborated with Alan Mills, providing the piano arrangements for Favorite Songs of Newfoundland, including four numbers from Peacock’s 1951 collection under the titles "I’se the B’y that Builds the Boat," "Harbour Le Cou," "Feller from Fortune," and "Hard Hard Times" (1958, 20-21, 32-33, 44-45, 38-39). All of them had previously been in published Doyle’s 1955 songster. These exchanges were part of the efforts of the revivalists to create a body of Canadian folksong wherein Newfoundland and its folksongs featured prominently.

39 In Newfoundland the situation was somewhat different. The popularity of the Doyle songsters was such that the new material was readily picked up by singers in the outports much as they would acquire material from the lumber camps, at sea, or through any other source. Between 1958 and 1961, Peacock returned to the province for four more fieldwork seasons and discovered, first-hand, the impact of the Doyle songsters. Soon after resuming his fieldwork in 1958, Peacock found "Harbour Le Cou" had become popular: "And so many singers in ’58 were singing this song and I thought it must be the [Doyle] book."48 As he later pointed out in Out-ports, "several of the songs have since become quite well known in Newfoundland and on the mainland and in recent years I have had to be careful not to re-collect them" (1965, I, 59).49

40 By this time urbanites in St. John’s had also begun to present choral arrangements of Newfoundland folksongs. In 1955 and 1956, Ignatius Rumboldt and the CJON Glee Club issued two long-playing records under the Rodeo label, dedicated to Rumboldt’s long-time friend, Gerald S. Doyle (Woodford 41-42).50 The albums included such well-known standards as "Kelligrews Soiree," "The Badger Drive," "The Squid Jiggin’ Ground," "Jack Was Every Inch a Sailor," and "I’se the B’y."51 In reviewing the albums, Peacock pointed out that the recordings, which relied so heavily on the Doyle material, were really limited in scope (1961, 40-41). By this time Peacock was in a position to speak with some authority. At the end of ten years of fieldwork he had managed to visit over 30 communities, collecting 766 songs and melodies from more than 100 singers.

41 For Peacock the problem was that up to 1961 he had actually published very little of his Newfoundland collection, mainly disseminating songs in more popular formats. Despite the diversity of material, as a comprehensive collection it was unavailable to the public. By this time, exclusive of the Doyle publications, those by Greenleaf and Mansfield and Karpeles were out of print. Peacock therefore attempted to publish as many songs as possible. With the Museum’s backing, Songs of the Newfoundland Outports (a total of 1,035 pages over three volumes) went to the printers in 1962, eventually appearing in 1965. With so many songs to choose from, Peacock opted to exclude several of those that he had passed to Doyle because they had been previously printed in 1955 (Guigné 2003, 47-63). In adding the word "Outports" to the title, he purposefully shifted the emphasis toward the singing tradition which best represented folk music as he saw it in the 1950s and away from the representations of this tradition as he had witnessed through the popularity of the songsters.

42 As Peacock pointed out in 1963 in "The Native Songs of Newfoundland," although the material he had collected included a wide range of songs from Britain, France, Canada, Ireland, and the United States under a wide range of themes, the "patriotic Doyle booklets" created the erroneous idea that "all her folksongs are locally-composed" (238). Peacock expanded this view by revealing the "scope and variety" of locally composed material he had personally collected (239). Peacock was understandably frustrated by the over-popularity of the Doyle collection, created mainly with material "mostly from my own collection" (1963, 213). The release of Outports in 1965 rapidly shifted perceptions. By the late 1960s, a new generation of Newfoundlanders, anxious to go beyond the Doyle material, readily embraced Peacock’s collection and created their own localized revival (Saugeres 1991). The timely arrival of Outports provided the province’s musical community with an extensive resource full of lesser-known songs. As Peacock had named the singers and their home community, it was also a valuable publication for members of Memorial University’s newly established Folklore Department, leading them to locate and record performers from these areas. In mainland Canada, the reaction was similar; Outports was readily seen as an exciting new collection to be used for performance, recordings, compositions, and educational materials (Guigné 2004).

43 In an interesting turn of events in 1965, shortly before Outports was released, the Doyle family again approached Peacock to provide assistance with the printing of a fourth edition of Old-Time Songs.52 The company was planning to issue the book in conjunction with the nationwide centennial celebrations in 1967 and the province’s efforts to celebrate its first fifteen years of union with Canada in the form of a "Come Home Year" celebration. Peacock briefly entertained the idea, suggesting that the family move toward a new body of folksong with chords and photographs, but the whole concept fell apart. By this time he was completely absorbed in the documentation of the newer ethnic traditions in Western Canada. The Doyles went ahead with the 1966 edition but kept to the original format, incorporating a sampling of songs and poetry from the three previous songsters including several Peacock had given to Doyle in 1952 for the 1955 edition (1966, 23, 28, 31, 46). This time they also published Bob Macleod’s version of the "H’emmer Jane" (49), the one song Peacock despised because of its close association with the St. John’s tradition. As it is typically sung in a supposed outport dialect, Peacock found this derogatory because it negatively depicted a culture which for him was musically rich and vibrant.

CONCLUSION

44 As an astute businessman, Gerald S. Doyle successfully promoted local Newfoundland folksong between 1927 and 1955, publishing a total of 95 separate titles in three songsters. One-third of these would become widely popular in both Newfoundland and mainland Canada. The chain of events, which Doyle put in place by publishing his songsters, had ramifications for the direction of later folksong scholarship in Newfoundland and for the revival and popularization of folksong in Newfoundland and Canada. Peacock had no idea that the songs he passed Doyle in 1952 for the 1955 songster would take on a life of their own but, as with material in the two previous editions, these songs also became favoured in Newfoundland and mainland Canada. The popularity of the Doyle material forced Peacock to expand his research by recording other previously under-documented aspects of Newfoundland’s folk music tradition as he saw it in the 1950s. In turn, through Songs of the Newfoundland Outports, Peacock successfully presented to both Newfoundlanders and other Canadians a new view of Newfoundland culture.

45 Doyle relied more and more on non-Newfoundland collectors for material for his songsters — Greenleaf first and then Peacock — and, by using his marketing genius, he created an awareness of Newfoundland and its folksong. As only Peacock could appreciate, the material appearing in the Doyle songsters, even the 1955 edition, offered a finite view of Newfoundland culture. In publishing Songs of the Newfoundland Outports this view was something Peacock aimed to change, by shifting the view toward the rural tradition. As Outports contains so much diverse material by way of ballads, broadsides from the American, British, and Canadian traditions, alongside dozens of locally composed numbers, it continues to be a major resource for researchers of Newfoundland folksong and for Newfoundland revivalists interested in re-discovering their musical traditions.

46 Peacock’s collection, emerging during the time of a nationalist-driven Canadian folk revival of which the National Museum was a part, might well have been different without the popularity of the other. Peacock probably appreciated that he could do little to alter the ever-increasing popularity of songs such as "I’se the B’y" and "Feller from Fortune," which he initially passed to Doyle. As we now appreciate, through his own revivalist activities Peacock also contributed to the prevailing presence of these kinds of songs. Nevertheless, he was able to demonstrate beyond a doubt that there is a broader song tradition. Ironically, both Doyle and Peacock, each with their own aims, successfully promoted Newfoundland, establishing a popular market both in Newfoundland and Canada for its folksongs.

47 Today both the Doyle and the Peacock collections continue to be valuable resources for Newfoundlanders and their music. The internationally acclaimed group Great Big Sea, celebrated both in this province and across Canada for their particular style of Newfoundland music, recently released a new album: Great Big Sea: The Hard and the Easy (Warner 262606). Among the tracks are materials from the Doyle and Peacock collections, "The River Driver" is based on a version of the song that Peacock collected in 1959 from John T. O’Quinn (Peacock 1965, I, 198-199). Peacock’s sound recording of Quinn’s performance was part of a collection of field recordings released by the Canadian Museum of Civilization in 2003 under the title Songs of the Newfoundland Outports and Labrador (TCDA 19082-2). "Harbour le Cou" is one of the songs which Peacock passed to Doyle for the 1955 songster (1965, III, 759). One additional twist to this intriguing tale is Jim Payne and Don Walsh’s recent release of Kenneth Peacock’s Songs of the Newfoundland Outports Vol. 1-3 (SS 0305) in collaboration with the Canadian Museum of Civilization. These sound recordings are now digitized on CD ROM along with Peacock’s original texts and music as they appear in his 1965 publication. The collection includes the magnificent voices of Mike Kent, Monica Rossiter, Ned Rice, Jim Rice, Howard Morry, Venus Way, and Lloyd Soper, all of whom Peacock first visited in 1951. As both Doyle and Peacock would probably agree, here, for those who want to listen, is the essence of some of the finest Newfoundland music to be heard. In this sense Peacock continues to accomplish what he intended many years ago.

Works Cited

"1954. As Seen By Gerald S. Doyle." Atlantic Guardian (December 1954): 5-8, 16, 18-23.

Barbeau, Marius. "Folk-Song." Music in Canada. Ed. Ernest MacMillan. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1955. 32-54.

Blouin, C. 1982. "Index to Collection Sargent, M./Tower, L. Audio Documents, 1950. S.T-A-1.1 to 1.9." Canadian Centre for Folk [Culture] Studies. Library and Documentation Services, Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Britan, Gerald. "The Transformation of a Traditional Newfoundland Fishing Village." The Community in Canada Rural and Urban. Ed. Satadal Dasgupta. Lanham: University Press of America, 1996. 153-165.

Cable, Howard. Telephone interview. 11 March 1999.

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Archive, Toronto, Ontario. Transcript, "Leslie Bell Singers." 480416-04/00.

———. Transcript, "Newfoundland Folksongs." 520114-01/00. Canadian Museum of Civilization, Hull, Québec. Fonds Kenneth Peacock.

———. Fonds Margaret Sargent.

Casey, George J., Neil V. Rosenberg, and Wilf W. Wareham. "Repertoire Categorization and Performer-Audience Relationships: Some Newfoundland Folksong Examples." Ethnomusicology 16 (1972): 397-403.

Coffin, Tristram Potter. "Leach, MacEdward (1892-1967)." American Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Ed. Jan Harold Brunvand. New York: Garland Publishing, 1996. 434.

Cowle, Alan H. "Bell, Leslie (Richard)." "The Leslie Bell Singers." Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. Eds. Helmut Kallmann, G. Potvin, and K. Winters. 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992. 107, 744.

Croft, Clary. Helen Creighton: Canada’s First Lady of Folklore. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 1999.

Deir, Glenn "We’ll Rant and We’ll Roar: The Gerald S. Doyle Songbooks." The Livyere 1.3-4 (Winter/Spring 1982): 38-40.

Doyle, Gerald S., comp. and pub. Old-Time Songs and Poetry of Newfoundland. St. John’s: Manning and Rabbitts, 1927.

———. Old-Time Songs and Poetry of Newfoundland. 2nd ed. St. John’s Gerald S. Doyle Ltd., 1940.

———. Old-Time Songs of Newfoundland. 3rd ed. St. John’s: Gerald S. Doyle Ltd., 1955a.

———. Old-Time Songs of Newfoundland. [without advertisements] 3rd ed. St. John’s: Gerald S. Doyle Ltd., 1955b.

———. "Gerald S. Doyle’s Annual Review. Report of Author’s Coastal Tour Around Nfld." Atlantic Guardian (December 1955c): 5-14, 40-48.

Doyle, Gerald S. Ltd. Old-Time Songs of Newfoundland. St. John’s, 1966 and 1978.

Doyle, Marjorie. "Prominent Figures From Our Recent Past: Gerald Stanley Doyle, O.B.E., K.S.G." The Newfoundland Quarterly 84.3 (1989): 32.

Doyle, Thomas. Personal communication. 14 January 2006.

Emerson, Frederick R. "Newfoundland Folk Music." The Book of Newfoundland. Ed. J.R. Smallwood. Vol. 1. St. John’s: Newfoundland Book Publishers, 1937. 234-238.

"Folksongs and Yarns." Atlantic Guardian (May 1948): 37-38.

Fowke, Edith, comp. The Penguin Book of Canadian Folksongs. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. 1973.

Fowke, Edith and Richard Johnston. Folksongs of Canada. Waterloo, ON: Waterloo Music, 1954.

"Newfoundland Businesses and Personalities. Gerald S. Doyle Limited: Thirtieth Anniversary of Gerald S. Doyle News." The Newfoundland Quarterly 61.4 (1962): 21-23.

Greenleaf, Elisabeth B. and Grace Y. Mansfield. Ballads and Sea Songs of Newfoundland. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1933.

Guigné, Anna Kearney. "‘The Folklore Treasure There is Astounding’: Re-appraising Margaret Sargent McTaggart’s Contribution to the Documentation of Newfoundland Folksong at Mid-Century." Ethnologies, forthcoming.

———. "Kenneth Peacock’s Songs of the Newfoundland Outports: The Cultural Politics of a Newfoundland Song Collection." PhD diss., Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, 2004.

———. "The Songs that Nearly Got Away." Canadian Journal for Traditional Music 30 (2003): 47-63.

"Here and There." The Evening Citizen (Ottawa, ON), 31 May 1952: sect 3.24.

Hiscock, Philip. "Folk Programming Versus Elite Information: The Doyle Bulletin and the Public Despatch." Culture & Tradition 12 (1988): 41-59.

———. "Folk Process in a Popular Medium: The ‘Irene B. Mellon’ Radio Programme, 1934-1941." Studies in Newfoundland Folklore: Community and Process. Ed. Gerald Thomas and J.D.A. Widdowson. St. John’s: Breakwater, for Dept. of Folklore, 1991. 177-190.

———. "Taking Apart ‘Tickle Cove Pond’." Canadian Journal for Traditional Music 29 (2002): 32-68.

———. "I’s the B’y and Its Sisters: Language, Symbol and Crystallization." Bean Blossom to Bannerman, Odyssey of a Folklorist: A Festschrift for Neil V. Rosenberg. Ed. Martin Lovelace, Peter Narváez, and Diane Tye. St. John’s, Memorial University of Newfoundland: Folklore and Language Publications, 2005. 205-242.

Karpeles, Maud. Folksongs from Newfoundland. Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1970.

Karpeles, Maud, coll. and ed. Folksongs from Newfoundland. 2 vols. Accom. Ralph Vaughan Williams et al. London: Oxford University Press, 1934.

Lovelace, Martin. "Unnatural Selection: Maud Karpeles’s Newfoundland Field Diaries." Folksong: Tradition, Revival and Re-Creation. Ed. Ian Russell and David Atkinson. Aberdeen: The Elphinstone Institute, 2004. 285-299.

MacEdward Leach and the Songs of Atlantic Canada. 11 August 2006 http://www.mun.ca/ folklore/leach/.

Matthews, D. Ralph. "The ‘Modernization’ of Newfoundland." Interpreting Canada’s Past. Vol. 2. Ed. J.M. Bumsted. 2nd ed. Toronto: Oxford Press, 1986. 636-661.

McNaughton, Janet C. "John Murray Gibbon and the Inter-War Folk Festivals." Canadian Folklore canadien 3.1 (1981): 67-73.

Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Archive [MUNFLA]. Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Newfoundland. Kenneth Peacock Collection, Accession 87-157. ———. Maud Karpeles Collection, Accession 78-003.

Mercer, Paul. Newfoundland Songs and Ballads in Print 1842-1974: A Title and First Line Index. Bibliographic and Special Series No. 6. St. John’s: Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1979.

Mills, Alan. Favourite Songs of Newfoundland. Piano accompaniment by Kenneth Peacock. Toronto: Berandol Music, 1958.

Neary, Peter. Newfoundland in the North Atlantic World, 1922-1949. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988.

Nowry, Laurence. 1995. Man of Mana: Marius Barbeau. Toronto: NC Press, 1995.

Peacock, Kenneth. Rev. of Gaelic Mod Souvenir Album, by MacDonald Hundred Junior Pipe Band (Rodeo RLD 74); Marches Strathspeys, Reels and Jigs of the Cape Breton Scot (Rodeo RLP 75); Newfoundland Folksongs and other Selections, by CJON Glee Club (Rodeo RLP 83); Newfoundland Folksongs-Volume 2, by CJON Glee Club (Rodeo RLP 84); Au Pays De l’Erable, Les Joyeux Copains de Hawkesbury (London MB7); and Canada’s Story in Song Sung by Alan Mills (Folkways FW 3000). Canadian Music Journal 5.2 (1961): 40-41.

———. "The Native Songs of Newfoundland." Contributions to Anthropology, 1960 Part II. Bulletin No. 190, National Museum of Canada. Ottawa: Dept. of Northern Affairs and National Resources, 1963. 213-239.

———. Songs of the Newfoundland Outports. 3 vols. Bulletin No. 197, Anthropological Series 65. Ottawa: National Museum of Canada, 1965.

Peacock, Kenneth. Personal Interviews. 8 and 20 February 1994, 30 May 1996, 16 April, 21 June and 2 October 1997, 8 and 20 October 2000.

Pumphrey, Ron. "Well-Known Businessman, Gerald S. Doyle Gives Comprehensive Report on Newfoundland Business Conditions." The Newfoundland Journal of Commerce (October 1955): 25-27.

Rompkey, Ronald. Grenfell of Labrador: A Biography. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991.

Rosenberg, Neil V. "The Gerald S. Doyle Songsters and the Politics of Newfoundland Folksong." Canadian Folklore canadien 13.1 (1991): 45-57.

———. Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

———. "The Canadianization of Newfoundland Folksong; Or the Newfoundlandization of Canadian Folksong." Journal of Canadian Studies 29.1 (1994): 55-73.

Rosenberg, Neil V. and Anna Kearney Guigné. Foreword to Ballads and Sea Songs of Newfoundland, by Elizabeth Greenleaf and Grace Mansfield. Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Publications, 2004. ix-xxv.

Sargent, Margaret. "Seven Songs from Lorette." Journal of American Folklore 63.248 (1950): 175-180.

———. "Folk and Primitive Music in Canada." Annual Report of the National Museum of Canada for the Fiscal Year 1949-1950. Bulletin No. 123 (Canada, National Museum of Canada) Ottawa: Dept. of Resources and Development, 1951. 75-79.

Saskatchewan Archives Board. Kenneth Peacock Collection, Accession 599-68.

Saugeres, Lise. "Figgy Duff and Newfoundland Culture." MA thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1991.

Soper, Lloyd. Personal Interview. 20 October 2000.

Taft, Michael. "‘That’s Two More Dollars’: Jimmy Linegar’s Success with Country Music in Newfoundland." Folklore Forum 7 (1974): 99-120.

———. A Regional Discography of Newfoundland and Labrador 1904-1972. Bibliographical and Special Series, No. 1. St. John’s: Memorial University Folklore and Language Archive, 1975.

Thistle, Lauretta. "Chasing Tunes in No. 10." The Evening Citizen [Ottawa, ON] 27 October, 1951: 24.

Thoms, James R. "The Doyle News: A Newfoundland Institution." Book of Newfoundland. Vol. 4, 1967. 346-350.

Thomas, Philip J. Emails to author. 28 May and 14 August 2004.

———. Letter to author. 14 August 2004.

Vallis, Ewart. Telephone interview. 20 June 2000.

Vassar College Libraries, Poughkeepsie, New York. Elisabeth Greenleaf Correspondence, Henry Noble MacCracken Papers.

Wesley, Gordon. "Oh, This is the Place Where Newfoundlanders Gather ..." Imperial Oil Review (April 1963): 7-11.

Woodford, Paul G. The Life and Contributions of Ignatius Rumboldt to Music in Newfoundland. St. John’s: Creative Publishers, 1984.

Discography

Barbeau, Marius. Canadian Folk Songs. Vol. 8. Ed. Marius Barbeau, Columbia World Library of Folk and Primitive Music (SL-211, 1954) LP, 33 1/3 rpm.

Canadian Museum of Civilization, Tont Crin Discs. Songs of Newfoundland Outports and Labrador/Chansons de Terre-Neuve et de Labrador. (TCDA 19082-2, 2003), compact disc.

The Glee Club of CJON-TV and Radio, St. John’s Newfoundland. CJON’s Glee Club Sings Newfoundland Folksongs and Other Selections. Rodeo (RLP 83) LP 33 1/3 rpm.

Great Big Sea. Great Big Sea: The Hard and the Easy (Warner 262606).

Mills, Alan. Folksongs of Newfoundland (Folkways 6831, 1953).

———. Newfoundland Folksongs — Vol 2. Rodeo Records (RPL, 84) LP, 33 1/3 rpm.

Kenneth Peacock, Jim Payne, Don Walsh and the Canadian Museum of Civilization. Kenneth Peacock’s Songs of the Newfoundland Outports. Coll. and ed. Kenneth Peacock (SS 0305, 2001) CD ROM.

Peacock, Kenneth. Songs and Ballads of Newfoundland Sung by Ken Peacock. Folkways (FG 3505, 1956) LP, 33 1/3 rpm. Smithsonian Folkways, cassette tape.

Notes