Interviews & Reflections / Entrevues et réflexions

Folklore, Fieldwork, and Vernacular Architecture: Reflections by Henry Glassie

Interview and Introduction by Gerald L. Pocius

Introduction

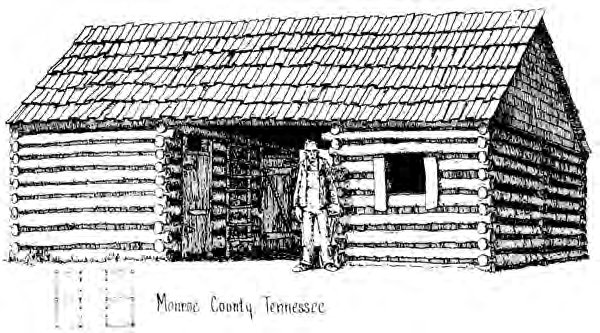

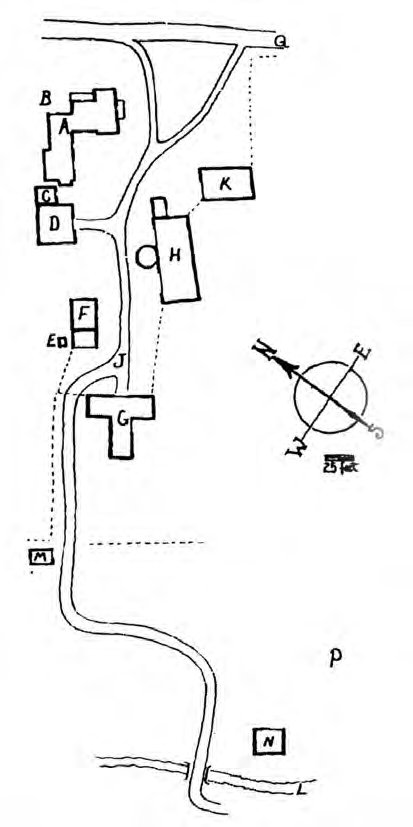

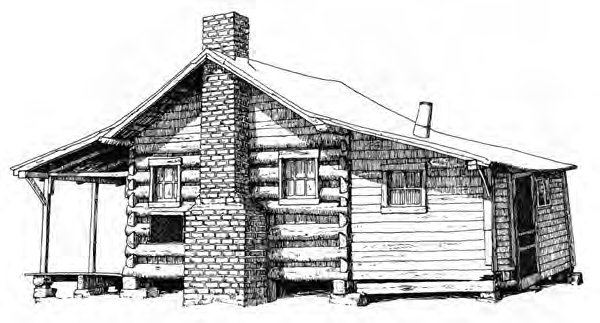

1 Henry Glassie (Fig. 1) has contributed more than any other folklorist to the study of vernacular architecture. Even as an undergraduate student, he was interested in documenting what would later be called vernacular architecture—drawing log cabins, barns, and other outbuildings across the American South. While the discipline of folklore was beginning to professionalize and expand in the early 1960s, no North American folklorist had yet devoted research to ordinary buildings. Glassie’s pioneering work combined many of the elements of his folklore training in historical and contemporary ethnography, along with influences from cultural geography and archaeology. He produced what still remain seminal field studies used by vernacular architecture scholars past and present no matter their disciplinary training. Glassie’s Folk Housing in Middle Virginia (1975) and Passing the Time in Ballymenone (1982) remain among the best examples of how the folklorist understands architecture, interpreting both the fabric of the building and the mind that built it. For this special issue of Material Culture Review / Revue de la culture matérielle devoted to the contributions folklorists have made to the study of vernacular architecture—looking back, looking forward—Henry agreed to reflect on his life as a folklorist studying architecture. What were the important concepts and methods he developed? What can folklore scholars offer other students of ordinary buildings?

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

2 Henry was interviewed at the sound recording studio in the Centre for Cape Breton Studies at Cape Breton University, on September 12, 2019.1 He was visiting Cape Breton University to give a keynote address to a conference on Intangible Cultural Heritage. Henry was given a series of questions ahead of time of topics to be covered. Instead of a question and answer format, he preferred to speak in an uninterrupted monologue which lasted about two and a half hours. The text that follows has been edited and shortened where necessary, but essentially remains Henry’s reflections on his study of vernacular architecture over his renowned career as an academic and public-sector folklorist.

The Beginning: Recording Folksongs and Repertoires

3 By the time that I was sixteen, I knew that I wanted to be a thing called a folklorist. I’d learned about folklore from liner notes to records, like Kenny Goldstein’s, for example.2 That had led me to books. I’d read books by the Lomaxes.3 And it led me ultimately to Traditional Ballads of Virginia (Davis 1929). I was a little kid in Virginia, I identified with the South and I read C. Alphonso Smith’s book.4 Just read it like it was a novel–it was just a collection of Child ballads from the beginning to the end.

4 I knew that people did fieldwork. And that just meant a tape recorder and you go somewhere. And because I was where I was—raised looking up at the Blue Ridge mountains—I knew that where I wanted to go was up into the Blue Ridge mountains. And did.

5 So, here’s the way that I think I would start–you’ve got to start at the beginning. And the beginning for this would be, a place to begin would be the summer of 1961. I had just turned twenty and for the first time I’m going to go into the field as a dedicated folklorist. I’ve got my tape recorder, I’m ready to go, I understand something about what folklorists do, and I’m off.

6 So, when I was propelled forward to do fieldwork, there were a couple of things that had driven me there. First of all, I felt that I was a Southerner and I felt that the South was not accurately represented, generally, in the mass media and so on; that people were prejudiced against the South. I certainly wasn’t. I identified myself strongly as a Southerner. And what I thought of the South as a place, it was rural. Not urban. That it had Black people as well as white people, and it had great music.

7 And so from the very beginning I was very interested in what we call folksongs and very interested in what people called commercial country music. I mean, that was my music and I loved it. And I loved the music in church, and I loved the music that was played. My great uncle was a good fiddler. I was effectively raised in this music, but the music was for me the proper emblem of the South that was made by Black and white people together. That’s really what I was after, and I really wanted to do that.

8 So ... that summer, I’m twenty years old. I just root out a singer and banjo picker called George Pegram and I knew that he was the kind of guy that made this stuff called folk music. And he had made a record called Pickin’ and Blowin’ with Walt Parham, and I liked that record (Pegram and Parham 1957). And I just went and he was in Mount Airy, North Carolina. And Pegram was a nice guy. Definitely a nice man. And that’s just what I found from that, my first minute of fieldwork: You know what? People are really nice. And they’re complimented that you want to record them. A lot of times students say, “I don’t want to intrude on somebody.” You’re not intruding! People are bored and tired and they’re happy and they want you there.

9 So, George Pegram was really nice and he recorded for me. Well, here was the thing that Pegram did. He sang the “Boston Burglar.”5 I knew that was a folksong. This is exciting! Here’s a man actually out in the hills who sings actual folk songs. He sang “Ellen Smith.” Not only did he sing the murder ballad of “Ellen Smith,” but his grandmother actually knew the man who killed Ellen Smith in 1890—I think 1896 is a right date.6 And she said to George Pegram that he was the handsomest man she had ever seen. So, here’s a handsome murderer and a ballad that’s about a murder. That’s the kind of stuff folklorists are supposed to be interested in. He also sang “Love Letters in the Sand.”7 What the hell is going on? That’s not a folksong. This guy’s a folksinger, right? And he’s singing country, a recent country hit as well. Instantaneously, I was more interested in him than I was in the folksongs. That was the first revolutionary moment. This is really interesting. I like country music. It wasn’t like country music was alien to me and I was an enemy of country music. But this guy collapsed that stuff in together. And so, what do I do about this? I didn’t know. But here was the first great fortunate thing in my folkloristic life.

10 In that same summer, I met Paul Clayton Worthington.8 Clayton made many records, folksong records. He sang himself, but he was unlike most of the folksingers in that he actually did fieldwork. He was actually performing on Riverside Records songs that he had himself collected. He did that work ... that I wanted to do. And I met him. He was enough older than me to be mature. He had also just completed—with A.K. Davis—all the transcriptions for the More Traditional Ballads of Virginia (Davis 1960; Coltman 2008: 27-28, 130-31).9 So, I had a pair of bibles at that moment. And the brand new one, Clayton was part of it.

11 I was thrilled to meet Paul Clayton, but what did he do? He lived in a log cabin, Brown’s Cove, in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. And he was recording the full repertory of his neighbour, Mrs. McAllister. And all a sudden I realize that—I mean, I’m talking about just barely twenty years old—that’s the answer! It’s not to collect like a collector. It’s to record the repertoires of singers. Then you’ve got the whole picture of the singer. Then you’ve got George Pegram doing “Love Letters in the Sand” as well as “Ellen Smith.” That’s a natural thing. Clayton was recording the complete repertory of Mrs. McAllister. That was the answer, methodologically. The first answer that I had methodologically. And what I was going to do, and began within a year, was to record the complete repertory of a ballad singer from North Carolina called Tab Ward.10

12 And Tab Ward’s not a famous person. George Pegram had been on records, Tab Ward certainly hadn’t. But I had a model for proceeding. What I learned from Clayton, this basic thing, was a method. I didn’t have any method at all. I had a tape recorder, but that’s not a method. I would go up in the mountains—that’s not a method, it’s just kind of idle. But if you’re going to get to know someone well enough to record their entire repertories, I have my first problem solved. If I didn’t start with music, I’d be falsifying my background. That’s where it began, was music.

An Emerging Interest in Material Culture

13 When I was up in the mountains, I was excited by, very quickly, more than the songs. I began to be interested in a lot of things, but in particular I was interested in woodworking. My grandfather was a carpenter. I was raised by my grandparents as a little kid. I was used to woodworking. I was excited by two things that weren’t songs. One was furniture, especially old, you know, slat-backed mule-eared chairs. And the other one was log cabins. The only thing that I could say as background for being interested in log cabins is that my grandmother was born in a log cabin and when I was a little kid it was a stable, but I knew it was my grandmother’s birthplace. Her father came back from the Civil War defeated and he built that log cabin and my grandmother was born in it.11 So, there’s kind of a sentimental attachment to the concept of the log cabin. My vision wasn’t to study log cabins and furniture. I’d never heard of material culture. I mean, I’m talking about a guy that’s young. But I saw that there was something about those old ballads and something about those old houses that was the same.

14 And my vision was that what I would do—I had this grandiose vision at the age of twenty—I was going to make a book. And the book was going to be about a kind of scattering of Appalachian facts. And so, what it was going to have was stories. I was already finding stories—nobody told me that ancient tales were dead, so I found that they were still quite alive and I recorded a lot of ancient tales as well. So I was recording stories, I was recording songs, and I was taking photographs like crazy of things that I thought were ambient—a kind of context for those songs. I wasn’t thinking about studying them. I didn’t even want to. I was taking photographs and I didn’t want to take photographs. I wanted to draw them.

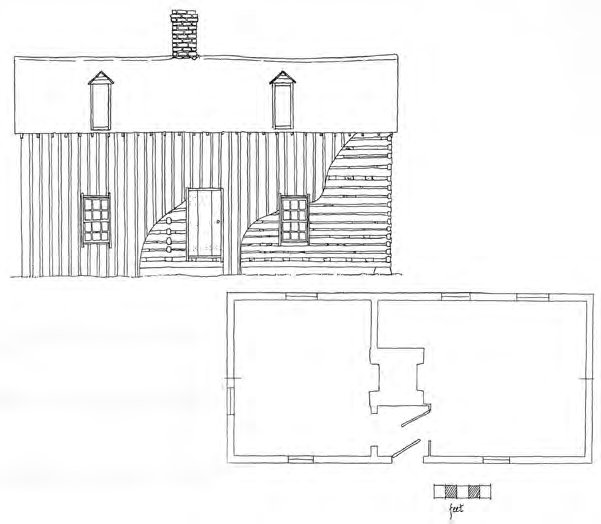

15 I really had a very clear vision that I would have ballads and stories and then I would have my own drawings. The only skill that I actually have is drawing. These other things are kind of fraudulent, like actually, from the time I was tiny I could draw. I sort of identified myself as an artist. I loved Italian Renaissance painting. I liked baseball more, but I liked Italian Renaissance painting a lot.

16 And so I wasn’t intending to study architecture or furniture, I was drawn to it because I was interested in woodwork itself. And I also thought that I could make drawings and I really wanted an excuse to make drawings. And if anybody were to run into the first publications that I made—all the writing was just an excuse to make drawings. That’s just true. I wanted to make drawings. But actually, more important was my excitement about carpentry. I could do a little of it myself. I still do. And my grandfather was a great carpenter. I mean, professional. That’s what he was, he was a carpenter. And he was really, really good. So, woodwork was interesting to me and I liked to draw some and make drawings of woodwork.

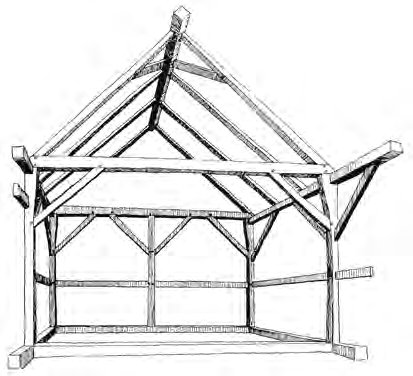

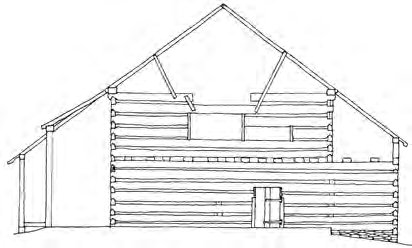

17 Well, into my life at almost that moment— still the same summer—the same way that Paul Clayton came in and sort of like an angel said, “Child, the thing to do with folksong is not to just record them. Get the full repertories of a singer,” another master arrived. I was out in upstate New York at the Farmers’ Museum in Cooperstown. And the Farmers’ Museum had tools. And an old gentleman was standing beside me, and he said—now, I could almost imitate him—he said, “Lad, do you know what that thing is?” And I said, “Sir, that’s a froe.” He said, “Do you know how to use it?” I said, “Indeed, I do.” “What do you do?” And I described the making of a shingle. And that man happened to be Fred Kniffen. And Fred Kniffen was the author of the first great study of American vernacular architecture called “Louisiana House Types,” published in 1936.

18 And I didn’t know that. He didn’t know who I was. But we immediately started talking. And he found that I had been going around in the Southern Mountains and taking photographs of buildings. I probably did say to him that I wasn’t actually interested in the buildings. They were a kind of setting for songs and stories, and I wanted to make drawings of them. But I was taking photographs. And he had a little Leica [camera], and he was really a good photographer. And he kind of swung me around at that point, that the photograph had some purpose in itself.

19 We talked and talked and talked, just fell onto each other at that time. He was teaching at LSU, Baton Rouge. I was headed for Tulane University in New Orleans—that’s close. We talked about Louisiana. We talked about all the things that we were interested in. And he said, that very first day, he said to me, “Lad, you can be the Francis James Child of folk architecture.” Well, Fred Kniffen is a geographer. Actually, he was trained by both [Alfred] Kroeber and [Carl] Sauer at Berkeley. But he knew about folklore, and he’d actually written a few little articles in the Journal of American Folklore (see Kniffen 1949; 1954; 1956; see also Vlach 1995). So, folklore was familiar to him, and he knew enough to be able to say to me—knowing that I loved old ballads—that I could do for folk architecture what Child had done for the ballad. Well, it’s a little extreme, but of course he knew how to get me and he got me! He caught me just like that.

Discovering New Methods

Typology

20 What Kniffen immediately gave me that made so much sense to me as a budding folklorist, was typology. I think a lot of people in the architecture business still don’t get it. They still don’t understand. They look at buildings—they don’t actually see them as architectural elements. They still act like collectors, rather than scholars. And collectors talk about the styles. So, you see, some buildings that have nothing to do with the Neoclassical, they label Neoclassical. What it is, it’s a Georgian plan house. That’s what is really going on. And Fred Kniffen taught me to look straight through the details to form. Immediately I understood, for example, that log cabins could be made of frame. You looked at the form instead of the details. I think bad architectural historians are obsessed with style. I wasn’t an architectural historian at all. I was obsessed with construction.

21 Then I was in it. I was off. Twenty years old: Paul Clayton has given me a method for recording songs that make sense, Fred Kniffen has given me a method for doing architecture. I was interested in typology, that is, the types, the forms, of buildings.

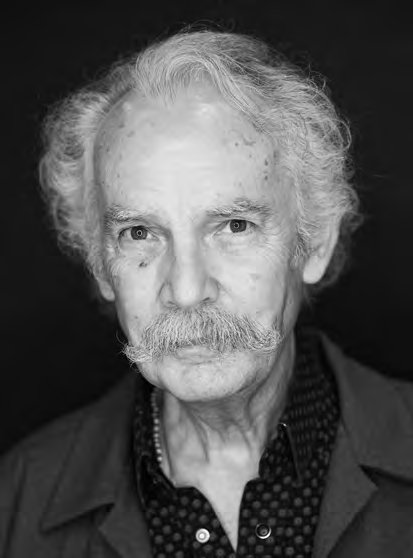

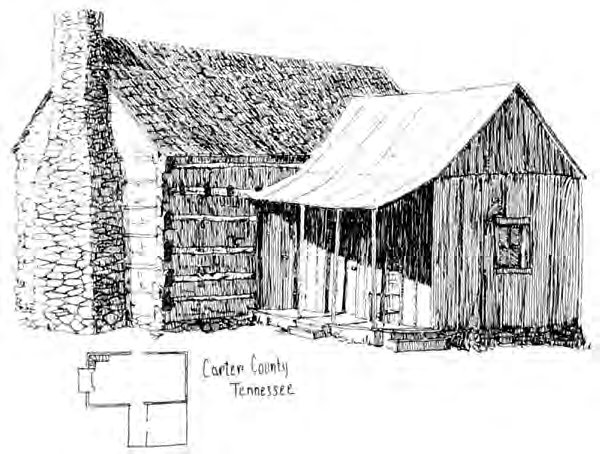

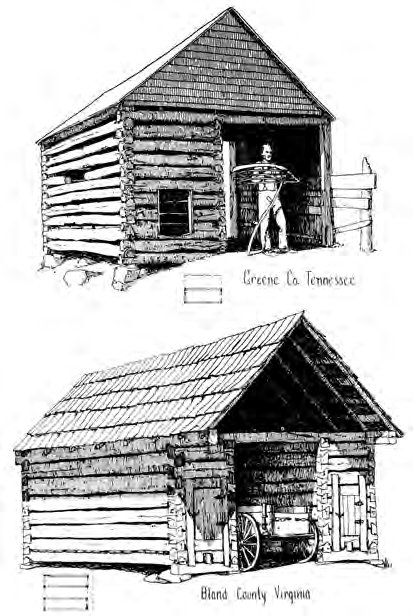

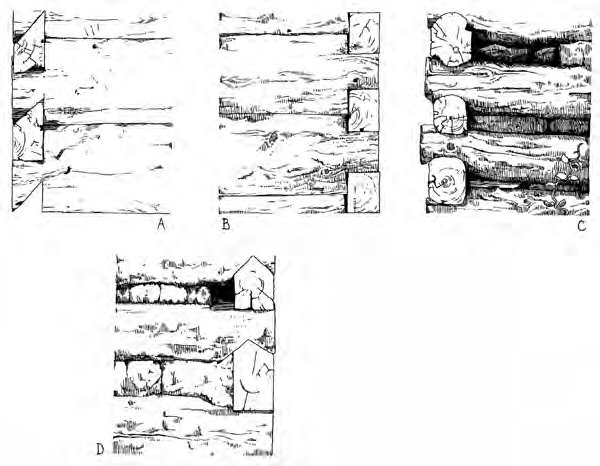

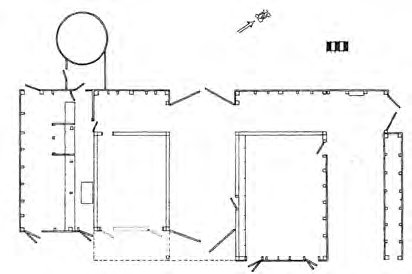

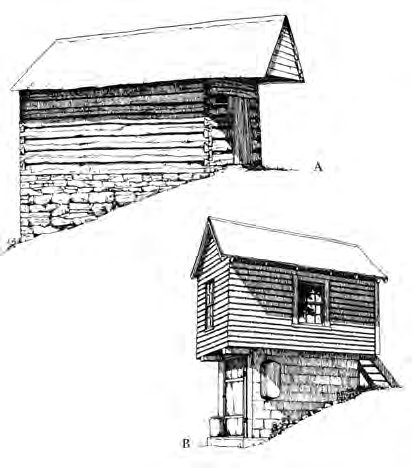

22 Skipping ahead just a little bit, by the time I graduated as an undergraduate, I’d already published a number of articles. I’d written about ballads, I’d written about folktales, I had written about architecture. And the very first article that I ever wrote—the first thing I ever published—was on the Appalachian log cabin. 1963, I was twenty-two (see Glassie 1963). It was published in Mountain Life and Work, a little Appalachian journal (Fig. 2).12 And I got a letter from Jesse Stuart, the great poet, saying, “That’s new information! I loved that information that you had in that little article.” I met Bascom Lamar Lunsford, another of my great heroes, a great musician. And Mr. Lunsford said, “Well, you’ve got a mission for our people. Study their buildings. Nobody has done that before.”13 See, it’s still poets, and nobody here in this story yet is an architectural historian, or anything like it. Fred Kniffen was a geographer. So, I became absolutely committed to a Kniffen-style geography. That was really what I did. I was a folklorist, but I had a real method. And so I continued to work with singers and I continued to work on repertories, and I continued to attend to architecture (see Glassie 1964 and 1965a. And I continued to be particularly interested in typology (Figs. 3, 4).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

Traverses

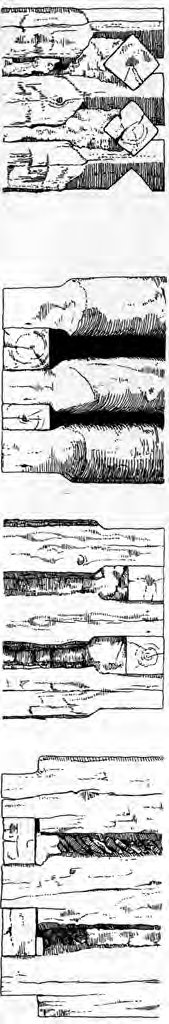

23 The first time that I did take on Kniffen’s second lesson, which is about traverses, was when I graduated from college. I went to Tulane, studied anthropology and medieval literature. Then I went to the Cooperstown program, which was in its very first year. And when I was there, I was settled in Otsego County, New York. And Kniffen and I had, by that time, really gotten very interested in the complexities of log building. We had a map at LSU that had every county in the eastern United States on that map. It was a gigantic map. We’d put dots for every variety of log construction. And we were seeing, oh, square notching is all towards the east. There’s a half-dovetailing that seems to come down into Eastern Tennessee; that the V-notching really swells out of Pennsylvania (Fig. 5).14

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

24 We had all this kind of patterning of log construction and we felt pretty confident that we were on the road to, really, some kind of interesting cultural-geographic conclusions. But I was in upstate New York, where there, in fact, was one very old log building which put a kicker in a lot of the thinking about log construction. But I was in a frame-using territory. And I said, “This is a great opportunity that I have.” Instead of studying log cabins, which I’m really interested in (still carpentry), I would study framed buildings. We didn’t have a comprehensive understanding of framed patterns. I was in a place with all these barns, and I set out to make a record of them (Figs. 6, 7). Because I was in one place, I could do the second thing that Kniffen taught, which was traverses. That is, not to just be interested in something that strikes you as interesting, but to drive along the road and make a record of every single building. And I did that in Otsego County in New York. I ultimately published that in the festschrift for Fred Kniffen (see Glassie 1974).

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

25 But what’s important, what I’m trying to suggest is important, is an evolution of method. And Kniffen gave me two things. First of all, you look at buildings as types. You know, you understand the gross grammar—the physical form—and don’t get distracted by little details of ornament, or even details of construction. But go straight to the essence of form. And the second thing is don’t just look at the ones that you’re sort of tickled by, look at them all. Every single one of them. So, I looked at every damn barn in Otsego County in New York and came up with really interesting conclusions.

26 I wasn’t yet thinking about history. I was just thinking about making a record. I was thinking about, you know, the cultural geographic patterning—what you want to do is to draw a portrait of a place. That’s what I was up to. And the portrait of the place would be a gathering-in of a whole set of interesting details. One of those details would be architecture, another one would be farming patterns. Other ones would be songs, and so on.

27 So, there I am. That’s me as a master’s student at Cooperstown. I wrote my master’s thesis on Appalachian architecture.15 I don’t have any idea what I said in it (Fig. 8). I don’t remember doing it. It’s just a master’s thesis. But the thing I did on barns was really good. I liked it. I thought I’d really done something here because we didn’t know much about framing and I was concentrating on framing. And furthermore, I’d done a proper traverse. So I’m off.

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

On Drawing

28 Drawing is just what I could do. I mean, it’s just, as a child, you know—I could get sentimental about that too. Because I can remember I was given very young, probably six or seven years old—people knew that I liked to draw—some kind of child’s history of art. And I turned to Caravaggio’s Calling of Saint Matthew. And I just said, “How the hell could that be done by a human being?” It was angelic. I was blown away by one particular picture by Caravaggio. And I didn’t actually get to see that in the church in which it is now there in Rome until about three years ago. But there was that one drawing, it was one painting. I was just blown away.

29 I was excited by Michelangelo. And I copied him. I mean, as a little kid with coloured pencils, I was copying drawings from the Sistine [Chapel] ceiling. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. So, I liked to draw. That’s just that simple.16 And when the need for drawing hit me, and hit me hard, I was at Cooperstown and I did a little study of a farm. It was the Wedderspoon Farm and I thought that I was doing something that was really necessary (Glassie 1966). Tom Hubka, ultimately, did that and did it right. I think Tom’s book on connected farm plans in New England is just great (Hubka 1984). But I got excited by the entire farmstead. And I thought that what we ought to be doing is less studying houses than assemblages of houses. I talked to Fen Wedderspoon, and his wife, and these old folks that lived in this really amazing, quite wonderful, farmstead. And it was a work of art. The farmstead was a work of art (Fig. 9). It wasn’t a connected farm like New England, but the buildings were very clustered. There was a kind of courtyard plan, the buildings, and I was just thrilled by it as a work.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

30 I needed money. I was a student, like other students. But I had kids, and not many of them did. And I had a wife. Louis Jones, who was head of the Cooperstown program, got me a little contract to do a program for seventh grade social science in New York State. I did it to get kids to interview their grandparents about farm life. And I used the Wedderspoon Farm as the kind of prototype for that, for me. In other words, here’s the farmstead. What are the buildings for? There’s a hop barn, how is that used? You know, what are all the buildings for? Talk to your grandparents about what you do in these buildings.

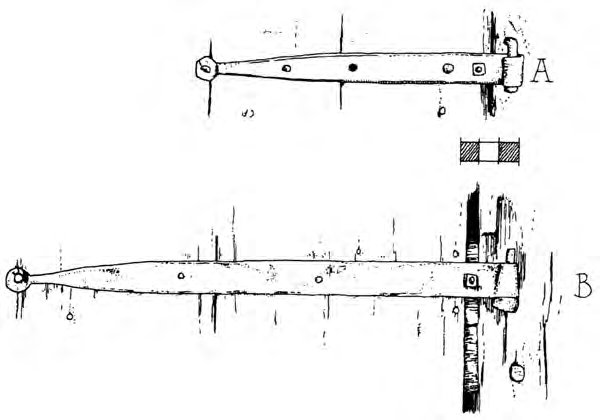

31 So, I did it. I did it with the Wedderspoons. And when I was doing that, I realized that I needed plans of the farm and the buildings. And I just drew them, and they weren’t good. When the article came out in New York Folklore Quarterly, and I looked at it, it was really how bad those plans are that I said, “I’ve got to figure this plan business out.” And so I just figured it out for myself. I looked at them. I said, “This is not right. We’ve got to do this more ... more like engineering drawings.” And there was Pencil Points.17 You know, I saw a couple of those. I said, “These are pretty plans.” I saw Kelly, in Early Domestic Architecture of Connecticut. I saw those plans (Kelly 1963). I said, “I got to figure out how to do that.”

32 I had always had—this is odd—but I’d always had a good drafting table because I bought it when I was in high school at the auction of a man called E. W. Donn who had actually been a restoration architect. And it was a nice, old, wooden table. I was just doing artier drawings on it. But I had it and said, “Heck, you just get a T-square and stuff and you can do this yourself.” I just taught myself how to do it. The prime motivation for my doing that was that I looked at the plans I had done of the Wedderspoon Farm and they just weren’t any good. And I didn’t know exactly why, I just knew these are not satisfactory, I’ve got to do this thing better. They weren’t measured. I didn’t have anybody talking to me about these things. They weren’t measured, but I sort of was just envisioning what it would look like from above, you know, the plan of the house and the plan of the barn. So they weren’t awful, but they were ugly. And they just, they didn’t satisfy me. I just knew that I had to do them more accurately.

33 So, you know, I started working with Rapidigraphs18 and stuff. And I had already been using that equipment for making kind of arty drawings. All those first articles that I’d written back when I was an undergraduate about Appalachian barns, Appalachian outbuildings, Appalachian log cabins, and so on, there were little funny plans, but they were stupid. But the drawing of the building was pretty good. To do a drawing of one of those, like, log buildings, I’d take fifteen or twenty photographs. All details. So, I had a lot of good photographs, so the drawings were not bad but the plans were just ridiculous. But I didn’t know that ... I knew something like that should be there, but I didn’t know what it’d look like. And so I snuck around, but I just taught myself how to do that.

34 When I was an undergraduate at Tulane, Fred Kniffen was great friends with Estyn Evans. Great Irish anthropologist, geographer, folklorist. And I met Evans. So, from meeting Evans, I knew that there were people that did write about buildings, but I didn’t think of them as architectural historians. Evans wrote Irish Heritage and Irish Folk Ways (Evans 1957; 1963). Both of them have houses in them. And good analysis of houses and typological analysis of houses. Really good. We became friends ultimately when I went to Ireland. I mean, I was very close to Estyn Evans. I’ve written essays about Evans’ work, and so on (e.g., Glassie 1996; 2008). I mean, I love him. I love Fred Kniffen among dead people most, maybe Estyn Evans second. Paul Clayton, maybe third. I mean, these people that were hitting me early and were so instructive.

35 But Evans. I recall meeting him in Baton Rouge, and he gave a terrific talk. Obviously, the talk he gives when he’s in America is about the two Irelands. But he looked at my plans and drawings, and he said, “This is the right thing to be doing. Not just taking photographs, you’re making drawings.” Mr. Kniffen didn’t make much in the way of plans. He took good photographs and then, for several of his articles when I was an undergraduate, he had me draw the buildings using photographs or using my own knowledge. But he wasn’t interested in—you wouldn’t find floor plans in [his publications] that much.

36 Evans did have floor plans. I can picture them right in my head. You know, the two basic Irish house types. The fact is, there are a whole lot more than two basic Irish house types, but that was kind of a vision. But he told me about other people, so I got interested in Iorwerth Peate’s book on Wales (1946). I began to read especially all the English literature, so that from Evans I was taken to British vernacular architecture study. Ron Brunskill, and so on. And so, I was reading all of that. That was really important to me. And it was important to me because it had a comparability. If you read Brunskill’s work, he’s interested in typologies and interested in consistent kinds of surveys too (see Brunskill 1965; 1970; 1974; 1982).

37 So, my mind is expanding. But I’m building on precisely what I’d learned in the very first year. So the next year [after Cooperstown] I go to the University of Pennsylvania to get my PhD in folklore, committed to folklore. I continued to improve both of these kinds of motions forward. So, in ’65 and ’66, I was recording Ola Belle Reed.19 And I also decided to go off and do architecture right. And I didn’t feel like I’d done it right yet, but I knew how to do it right. And I knew how to do it right, so if I did typologies and I did traverses. I was on the right track.

38 So Kniffen and I realized—we were really working together all this time—that we had pretty good information on the western South, but not the eastern South. It was kind of a gap. There was architectural history writing about it. Henry Chandlee Forman (see 1934; 1956). It just didn’t, it didn’t have this ... it didn’t move. It wasn’t moving. It was kind of: here’s an interesting old house, and here’s another interesting old house, and aren’t they interesting? Not particularly. But we needed to know eastern Virginia, so we kind of set that up. I mean, Kniffen and I, when I was in New York state, we were talking about it. And I said, “We have log buildings pretty much in order, but we don’t have framing.” So, we were being very consistent.

39 So then, eastern Virginia, I’d go there and I’d just set up. I just found a place and did these broad traverses to try and find a place where there was a lot of survival of early buildings. I didn’t care where it was. It ended up being in Louisa County, Virginia. And I just pitched a tent. I mean, it might be said that by this time, I’m married and I have a couple of kids. But they’re sort of dragged along. You know, without too much kicking and fighting. But any rate, they’re sort of dragged along. And at that point, I was working on my PhD in folklore at University of Pennsylvania.

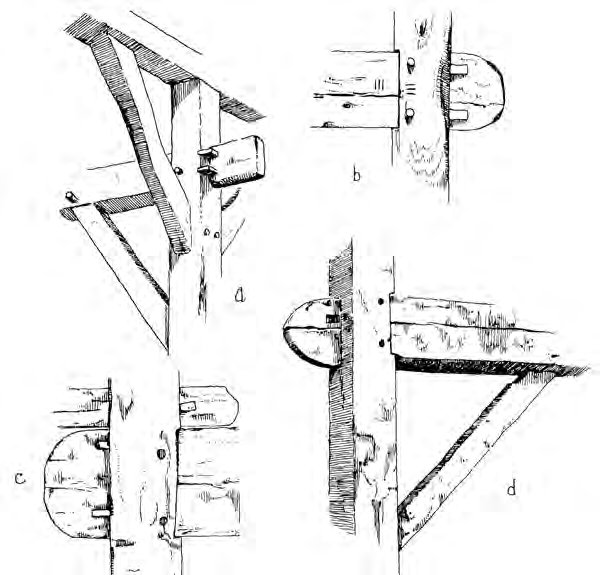

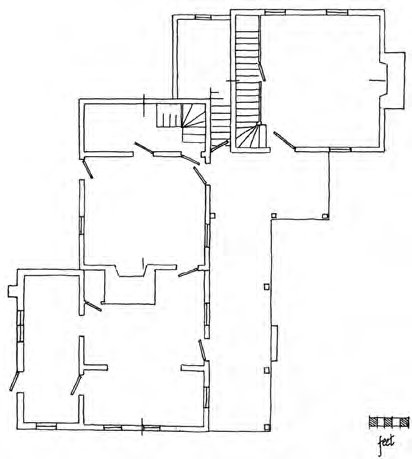

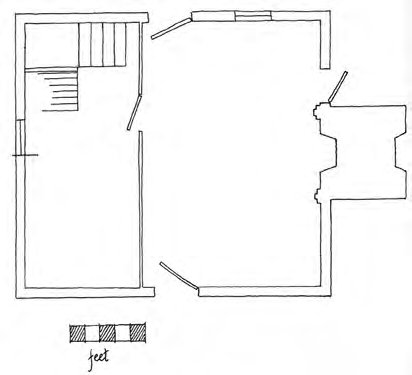

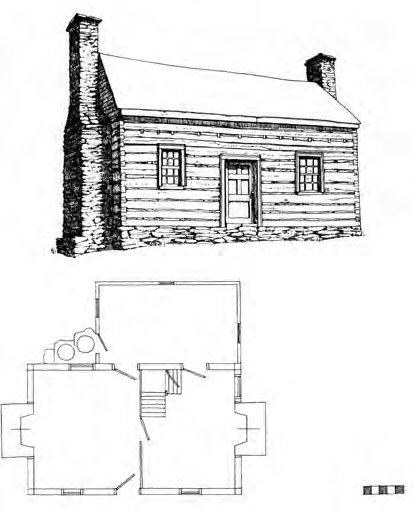

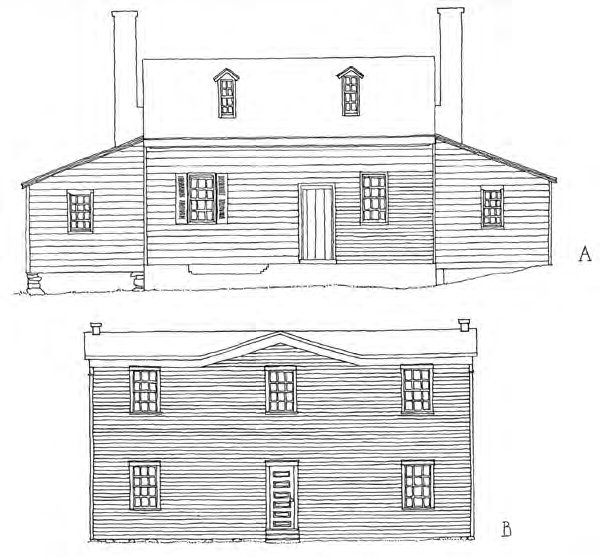

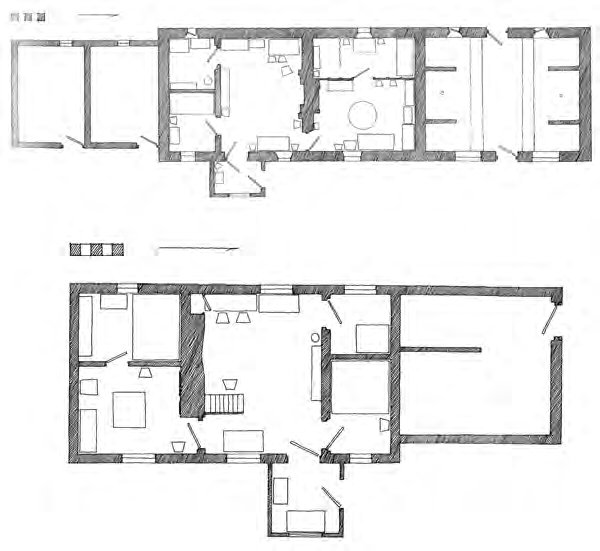

40 I was going to do it right. And what I had learned about what I’d done wrong up to this point was pretty clear. I hadn’t listened enough to the folklorist in me. The folklorist in me knew that when you record, every word, you’re transcribing. If I’m with Ola Belle and I’m transcribing her ballads, I’m getting every word. But I was kind of treating architecture too casually. That’s what I realized. And so what I knew on the basis of transcription of ballads is that I ought to be making better records of a few model houses—the excellent, especially good houses. So, when I set out to do the work that would ultimately become the Middle Virginia book (1975), then I had another mission for myself. One is I did a traverse, made a record of every single house. Two, I made a typology, so I knew what every house belonged to. But the third thing that I hadn’t done before is I made really good measured drawings. I had seen that kind in Kelly’s book on Connecticut. Nice drawings. And I really wanted to draw, anyway, so then I said, “that’s what I ought to be doing. I ought to be making really good measured drawings.”

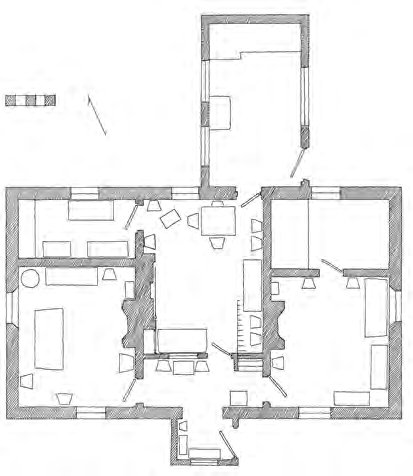

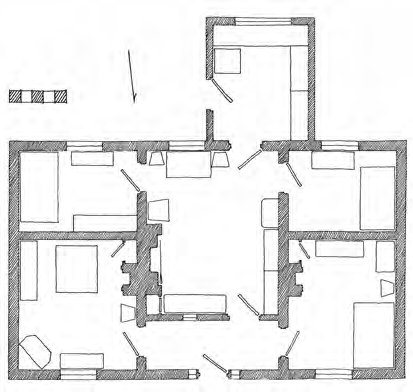

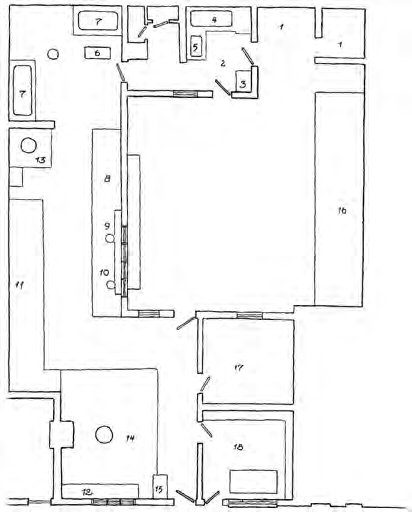

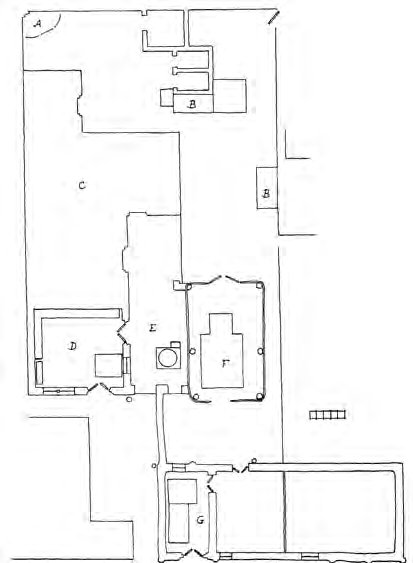

41 I first made a typology, and then having done the typology, I’d say, “Now pick a couple of examples from each type and make really good—I had rough drawings of them all—but really good drawings. Or any house I didn’t understand at all. I’d stop and do a measured plan. And so, I was sophisticating my drawing (Figs. 10, 11, 12). So it was really my studies of oral literature that drove me to making good records of buildings. More than looking at Kelly’s book. I mean, I didn’t stop and look at Kelly’s book and say, “How did he do it?” I just said, “I’ve got to figure out good, good methods of recording.” So at that point, I’ve added to the idea of repertory by recording the life history of the singer. That’s getting better. I’m adding to the idea of traverses and typologies good measured plans.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12

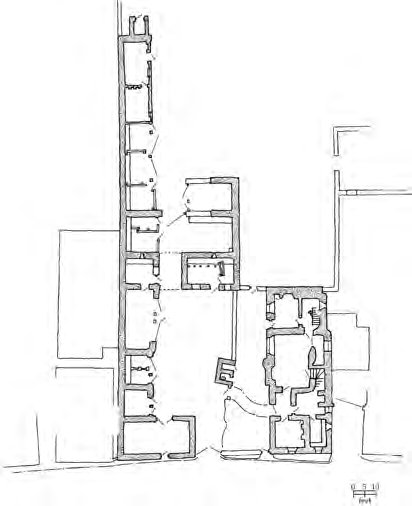

On Doing Architectural Field Recording

42 I just always had a little notebook. I learned early that if possible, you measure on the inside, not the outside, because then you can just always add the width of the walls, and so on. But the insides have got a lot more detail. And the detail is easy because if you’re just one person, which normally would be the case for me, you’re measuring short distances. So, if you measure from the wall to the window, and the width of the window, and then from the window to the door, you know, you can stretch out your tape measure, and just zip in a circle. And you can go really fast.

43 The most fun I ever had in the field probably was when Rusty Marshall and John Vlach and Steve Ohrn and I went to do this project in Greene County, Pennsylvania.20 And, I’m telling you, we could hit a lot. We found a lot of buildings—early log buildings. I can’t remember, something like fifty-three. We could measure those things like a rocket because we had three guys. Then it’s really easy. So, one guy’s stretching out the tape, calling out the numbers. The other guy’s making the drawing. That’s all really easy. But even if you’re alone, you can do it very, very rapidly. It gets to be troublesome when you have asymmetrical masonry buildings. It gets harder to do, but if you get framed buildings—you know, log, wooden buildings—it’s really very quick.

44 When I have all the data I can spread wide, and I usually make the drawings maybe three times the size that they will be appearing in the books. I also like it. It’s a matter of personal taste. I draw the straight lines with a pencil and a ruler, but I draw them with a pen free-hand. And it makes a kind of vitality. If you take that and reduce it a lot, you don’t see the wobbliness, but you get a sense of kind of an energetic mind. That’s just a matter of aesthetic taste there. As accurate as anything else, but I tend to do the final thing entirely by hand. Just going over the pencil lines that I’ve drawn with pen. You feel it—a kind of vibrance in the drawing, even though it’s just a straight line representing a straight line.

Entering Public Sector Folklore: Glassie as Pennsylvania State Folklorist

45 I was a graduate student at Penn. It was a time that I was writing the Pattern book (Glassie 1968a) on the one hand, but I was also spending just a lot of time with Ola Belle. I really was very fond of Ola Belle and very fond of especially Burl Kilby, who played the banjo in her band. And I was down as often as I could to Oxford. It’s not far from Philadelphia. You go down to Oxford, Pennsylvania, which is where Campbell’s Corners was—this store where every Sunday night, Ola Belle and her band, the New River Boys and Girls, with her brother Alex, performed. I was probably there every midnight Sunday for two years. So, that was the kind of setting.

46 And MacEdward Leach was in charge of the department at that time.21 And he had to retire. It was in those days required at a certain point to retire and he didn’t want to retire. He had no interest in it at all. So, he said, “If I’ve got to retire, I’m going to make a job for myself.” And the job he made for himself was to be the state folklorist of Pennsylvania. He invented the whole idea of having a state folklorist. Mac Leach was lobbying through the legislature of Pennsylvania with the support of ethnic groups. A Polish group from Wilkes-Barre, Scranton. Italians from Pittsburgh. African Americans from Philadelphia. And he was just smart enough to say to these different people “you all are different. But you know what, you are joined by the study of folklore.” He made this argument.

47 And so they passed a bill that was put through. A wonderful African American guy called Leroy Irvis, who eventually I befriended, he was the Speaker of the House of Pennsylvania. He got this bill through for the Ethnic Culture Survey, the state folklorist position. And MacEdward Leach worked for that because he wanted a job. Then what happened? They told him he’d have to live in Harrisburg. And he said [laughing], “Me? Living in Harrisburg? Come on! I live in Philadelphia. Philadelphia is a great city, Harrisburg is a kind of dead-end place.”

48 And so, he literally—I was in Tris Coffin’s class and Mac came to the door and said, “Glassie, come here.” And I went outside and stood in the hall. He said, “I’ve got a great job for you.” It was just because he didn’t want to live in Harrisburg! And, you know, what can I say? I, at that time, was married and had two kids. I could use a job. I wasn’t through with my studies at all. And I said, “You know, I haven’t finished my coursework here.” Mac said, “Come on. Independent study. We’ll just knock it out with independent study. You can do whatever you want to. Just go out to Harrisburg and get this good job.” You know, it paid something like eight thousand dollars a year. I mean, we’re talking big money. And so, I said, “Oh, okay.”

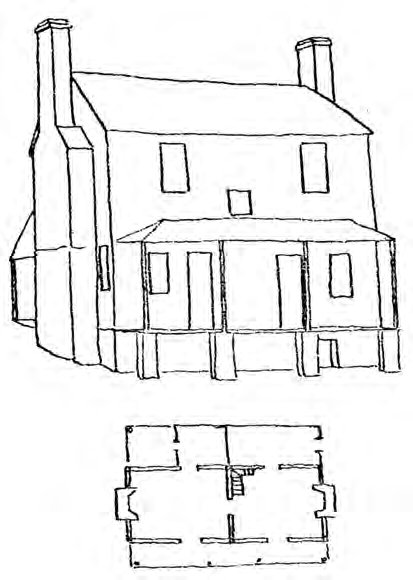

49 That’s exactly what happened! [Laughing] So I just did it because he didn’t want to do it. And so, I went out to Harrisburg and, you know, it was kind of a dream come true. I was working with Ola Belle all the time. And so I thought, I’m going to live south of Harrisburg. And I’m going to live near Pennsylvania Dutch Country. And I’m going to live near Ola Belle. And so I found a little, tiny farm in northern York County near a town called Dillsburg. And it was a Pennsylvania Dutch log house. Tiny. But real. And I was just exhilarated. I paid $8,100 dollars for a four-acre farm. It had a barn. Log house on it. I was in my radical hillbilly nationalist phase. [Laughing] I was so excited to own my own farm. I had two pet cows that I milked. It was so corny. But I loved it. I really loved it. I fit right in. [Glassie’s work as state folklorist included the documentation of architecture in the area (e. g., Figs. 13, 14, 15)].22

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 15

50 And, you know, I’ve already mentioned it, that was a time that I was employed at the state government of Pennsylvania and I could be sent to work in the Smithsonian, and was. Constantly. So, I worked with every folk festival, I was there with Ralph Rinzler.23 It was great fun. I wanted to advance Ola Belle’s career. I got her into the Folklife Festival and so on. Ralph and I applied for money all over the place. We went to all these big foundations trying to get money for folklore. We were not successful, but ... Ralph and I were a kind of team there for three or four years.

51 That was really crucial. Ralph—very important. I was a minor character. But it’s really important, getting public folklore going. The Smithsonian, the Library of Congress—all that is a direct consequence of Ralph’s work at the Smithsonian. And I could work with him and did as state folklorist. Pennsylvania had one [state folklorist], so Maryland decided it wanted one. Hired George Carey. George Carey is a friend of mine—a great, good guy. He got his PhD from Indiana; so, pretty soon you got state folklorists all over the place.

Folklore and Politics in the 1960s and Today

52 We were political. I mean, everybody was aware of politics. And the United States today—the very concept of politics is depressing. I don’t even want to say the name of the president of the United States at all. But, even countering that sort of drags you into it. You know, it’s kind of evil. In those days, we had evil and it was called Nixon. And we knew it was evil and it was just recognized as evil. And every day, kids were down there bringing Nixon down. And now people are wishy-washy because they think they’re doing something by ... you know, sending email messages to their friends about how much they hate Trump. That’s not going to get anywhere. I mean, people ought to be down there in the streets. I feel the whole thing is extremely depressing. It’s not an energetically political time.24

53 But at that time, it was energetically political and we knew that folklore was a political act. That it was oppositional—that’s the whole point of it. But if you think that doing folklore on the Internet is folklore, though it’s not oppositional, then you’re sucked in too. You’re complicit. You’re part of the, you know ... they used to talk about “the system” all the time. But if you’re sending messages on Facebook, you’re part of the system! You can’t be against the system. You are the system! But in those days, of course, you could be oppositional. And in those days, if you wanted to get half a million kids to Washington, DC, there was no Internet, but everybody would show up.

54 You know, after the kids were killed at Kent State,25 I’m telling you, everybody was there in Washington. Nobody had to tell anybody about it ... there’s no planning. It was my first year of teaching at a university. I felt like my students— my personal, beloved students—had been murdered. I’m going to go to Washington, DC, and when I’m down there, everybody is there. Earl Scruggs is there “pickin’ for peace.”26 You know? I think without question that folklore is inherently political. It’s inherently oppositional. You can call yourself a folklorist and not feel that way. In the old days, the first time I was going to the American Folklore Society, a part of the delight that I felt.... There’s a lot of old conservative guys that used to come. Mostly from the Midwest and the South. It wasn’t a bunch of radical people. But there were a lot of radical people there. But those old conservative guys also thought they were being oppositional. That was interesting to me. They were oppositionally conservative to a liberal disaster, in their minds. And I was [laughs] opposition to a conservative disaster in my mind, but we kind of got along.

55 But I don’t think that the kind of political nature of folklore would necessarily come into the mind of the students today. We were professionalizing; now they have professionalized. And I think it’s just not even a part of the question. That doesn’t mean everybody is like that, but I think that it’s possible to be a folklorist without even thinking about whether doing folklore is a political act. But nobody in 1967 wouldn’t have thought politically. Folklore was a political act. Even though they might be on opposite ends of the political spectrum. They certainly thought this was a political act.

56 And I went to all those things, all those events in Washington, DC. I mean, I went to them all. And I really believed in them, you know. And ultimately, I worked for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. I mean, I wasn’t outside civil rights. I was inside, hard inside. And so, I believed in it.

The Perils of Fieldwork and Pattern in the Material Folk Culture

57 Here I am, a first-year graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania in folklore. And Don Winkelman27—older than me—says, “Well, you are the person who could write the first thing that could be written about material culture and why folklorists should be interested in it.” That’s a very welcoming thing. It’s also true of that period that there was a great welcoming to young people. I mean, it was interesting that I was into this business, you know, a sort of professional folklorist well before I was thirty. And in those days, there was a lot of need to have young people. That was just like you would include Black people or gay people today—which, of course, God knows we should—but then it was the young, and being twenty-six or twenty-seven years old and writing books, I got invited to be in a lot of places. And so Winkelman said, “Well, you ought to write this thing.”

58 Well, I didn’t think much about it, but I was doing fieldwork in Virginia for the Middle Virginia book. I didn’t know I was writing Middle Virginia, but at any rate, I was doing the fieldwork. For the simple reason I wanted to do great fieldwork. That was really, really my goal. Not to come to any historical conclusion. But I came across a house, and everybody knew it was built by a man called Samuel Dabney. It was a tiny, little, square house. Basically, a one-room house with a chimney at the end.28 And it was really, very beautifully made. And it was a type of a house that I’d began to find other places. There’s two things you can do if you want to make a beautiful house. You can make it big or you can just make it really well. Occasionally what you find in early days is a lot of little houses are just gems. Beautifully made. All the mouldings and everything, but it’s tiny. It’s a different attitude about what you do with your time. You make a beautiful, small house or a big, lumpy house. So, Sam Dabney’s house was one of those gems; everything in it was beautiful. Beautifully made, everything was.

59 And so, what was the problem? It was completely covered with poison ivy. And so, me being the intrepid fieldworker ... I just went into it. And I made a measured plan of Sam Dabney’s house. And I caught an amazing case of poison ivy. I got poison ivy in my lungs. And I was dying. And I was rushed to the hospital at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, which was the nearest place. And they gave me all kinds of steroids and saved my life. Literally, my lungs were filling with poison ivy junk. You know, my eyes were closed. They had to put straws up my nostrils to have me breathe. It’s like brave? It was stupid! It wasn’t brave, but dumb.

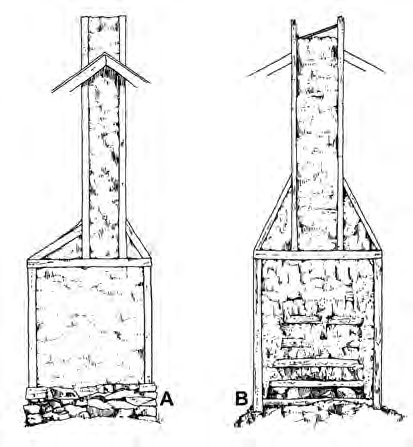

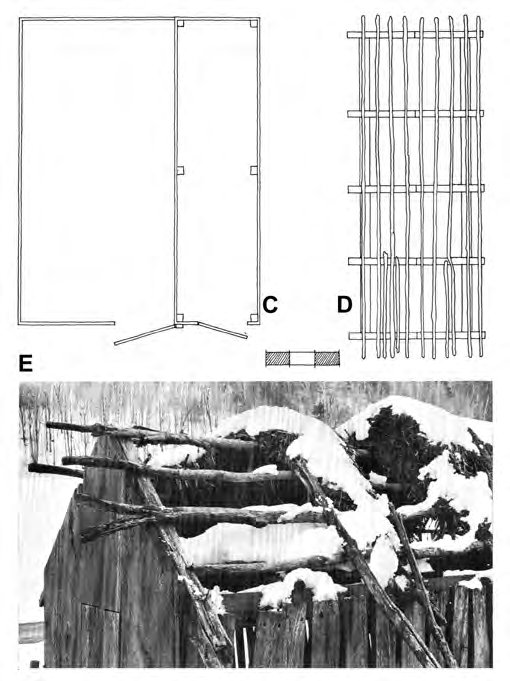

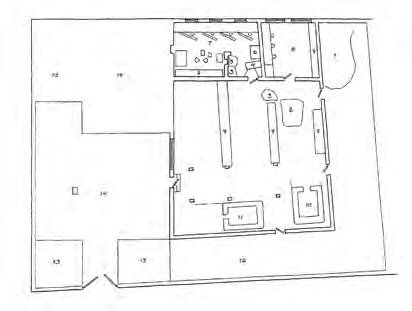

60 I’m out in Virginia. And I’ve got this fieldwork to be done, and I got poison ivy all over me. I’m out there, nowhere, with no electricity. You know, just ... gaslit lanterns and such. But I was too hurt to do fieldwork for a while. So, I started writing that book [Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States (1968a)]. And it was about why folklorists should care about material culture. That was what I did. It started out there in Middle Virginia, because I couldn’t do anything else for a while. I got better and I continued to heal, and then I went back to Penn for my second year. I just kept writing that book. And I just kept writing the thing, and kept writing the thing, and kept writing the thing [Glassie basically was compiling the fieldwork he had done over the years: while at Tulane (Figs. 16, 17, 18, 19), Cooperstown (Figs. 20, 21), and then in his public-sector job at Harrisburg (Fig. 22)]. The University of Pennsylvania library was fantastic. And with that library and with my interests, I saw the introduction to ... material culture.

Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 17

Display large image of Figure 17

Display large image of Figure 18

Display large image of Figure 18

Display large image of Figure 19

Display large image of Figure 19

Display large image of Figure 20

Display large image of Figure 20

Display large image of Figure 21

Display large image of Figure 21

Display large image of Figure 22

Display large image of Figure 22

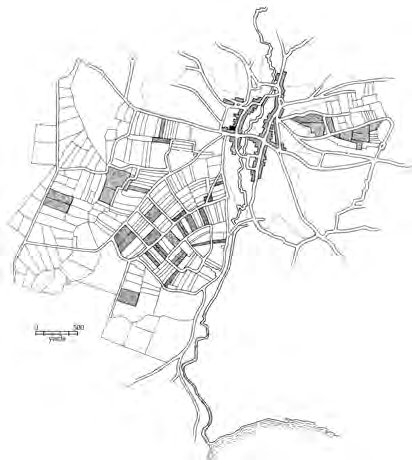

61 I think it’s good to say, it’s simple to say that what really we could teach to American history was regions. And I believe that. That is what I really profoundly believed, and do believe, that the United States is a kind of a thin overlay on really rich traditions. Regional traditions. I don’t want to say rural, because sometimes they’re quite urban. Memphis, New Orleans, Chicago, you know. But there are these deep, deep regional traditions that are really profound. And material culture revealed that. That was as good an idea as I could have at that particular moment for telling people why they should study material culture, was that it was a great revealer of regional difference.

62 It was done in the Kniffen School. I was just nothing more but Fred Kniffen’s boy when this was all going on. But we were reading Hans Kurath’s A Word Geography of the Eastern United States and noticing its incredible correlations (Kurath 1949). That just where, you know, log construction pushed up into southern Indiana was exactly the place that linguists called the “Hoosier Hump.” There’s a little place of southern dialect that’s up there. You followed all these dialect lines with architecture lines, and Kniffen and I were thrilled by that. And so the idea that I thought that I could have, that I could offer to the world as a reason why folklorists should be attentive to material culture had entirely to do with regions. And it fit perfectly well with, you know, all the Laws indexes of broadside ballads and American ballads, and you see these regional patterns. You can certainly see them. That was what I thought I could offer to folklorists. And I was just writing that book.

63 We’re talking about the late 1960s. And so I was very active in the desire to stop the war, and so on. I was downtown Philadelphia, and I was sitting-in on the street. Blocking traffic because ... I don’t know [laughs], somehow, I thought that by blocking traffic in Philadelphia we were going to stop the war in Vietnam. I didn’t know [laughs] why that was going to work, but we did. So, I was sitting-in, blocking the traffic. You know, we’re sort of bored out there stopping traffic. Big, burly cops in front of us. And the guy next to me, named John Bernheim, just said, “Well, what do you do?” I said, “Well, folklorist.” And he said, “Well, what are you doing?” And I said I was writing this book about, kind of, the regional nature of the United States based on things like barns, old houses, food, clothing, and furniture. He said, “You know, I’m an editor at the University of Pennsylvania Press. Let me have your book.” I said, “Well, okay.” I was a graduate student, so indeed I handed it to him. And Bernheim said, “This is really great. I’ve never seen anything like this.” And I said, “Well, Fred Kniffen is my man.”

64 The University of Pennsylvania Press accepted it for publication. At which time, it was sent over to the Folklore Department. The Penn Press said to Kenny Goldstein, “This folklorist has written a folklore book.” And so, Kenny said, “What do you mean? This is Glassie, my student!” Kenny said, “Yeah, it’s really good. Let’s publish it.” And so he did.

65 Meanwhile, I was doing fieldwork with African American teenagers, boys from my neighbourhood in Philadelphia. I was planning a dissertation on their stories and jokes, their verbal play. But Kenny convinced me not to write the dissertation I was writing, but he would accept the book I’d already written [Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States] for my dissertation. I wanted a PhD. Kenny gave me one for the book. That’s great. I’ll accept it. And I agreed for a very important reason. By that time I was so involved with civil rights that I was ambivalent about white people writing about Black people. I’d recorded music from Black folks in North Carolina. Easy, comfortable. I’m excited that the work Pravina Shukla and I are doing in Brazil has mostly been with people of African descent (see Glassie and Shukla 2018). Brazil is different, and what mattered here back then was the fight for civil rights.

Folk Housing in Middle Virginia

66 Evans wrote a great book, The Personality of Ireland (1973). I was writing “the personality of Middle Virginia.” That’s what I thought I was doing. What happened there in Virginia, however, is that as soon as I began to write about the personality of Virginia, the thing that I had not been taught to pay any attention to—you won’t find it in Kniffen and you won’t find it in Evans—was time. They were really tight. They were telling you a geographer’s story. I liked it. I appreciated it. I still am more apt to think of it that way. I’m much more apt to look at a building and think it’s characteristic of New England than I am to think it’s characteristic of 1830. I think first about space and second about time.

67 But when I really did the Virginia book, all of a sudden I realized that I didn’t have a spatial story at all, I had a historical story. I didn’t know it. I wasn’t trying to do that. All I was doing was making a good record of the buildings that I had, what I wasn’t even looking for is that there was a pattern of change. And that wasn’t what I wanted. I wanted to do a kind of personality of Middle Virginia, but the personality of Middle Virginia was about time.

68 Completely shocked me. And once I understood that, then that’s what I wrote about in the book. It may be scientifically incorrect, but if you do really good fieldwork, you don’t really have to know where you’re headed. By that time I was reading about structuralism and being exhilarated by the writings of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Noam Chomsky and so on. I had all this data about architecture and it fit.29 It wasn’t that I was trying to make it fit, it’s just by doing all this reading and having all this data, and finding the data was good, when I went back to the place, I found no problems.

69 I wrote the book in 1972.30 I was excited by the historical pattern from open to closed forms and from asymmetrical to symmetrical forms (Fig. 23). It seemed to be a principle, in that it seemed to be generalizable. I didn’t know that, but I presumed that there was a kind of generalizable principle that I had found on the ground in Virginia, without even looking for it. It’s kind of like an archaeologist would do. I’m just digging down, and you find stuff you didn’t expect to find.

Display large image of Figure 23

Display large image of Figure 23

70 And so, the archaeological metaphor is pretty good because around this time, I met Jim Deetz and begin to think a lot about archaeology. So, archaeology was kind of pouring into my thinking as well.31 Jim and I became great friends and sort of traded ideas back and forth. And we both dedicated books to each other.

Ireland

71 I got really interested in this historical pattern. Then I made—it was a little bold that I did—an application to the Guggenheim Foundation thinking that my discovery was really important and that it needed a test. And so, I made a perfectly reasonable, hypothetico-deductive test that I would try out my ideas in Ireland. The reason it would work in Ireland was that I theorized that the change from open to closed and asymmetrical to symmetrical happened before the Revolution. It was a sign of revolution coming. That is the change that had already been made in hearts, and minds, and men. It was a predictor.

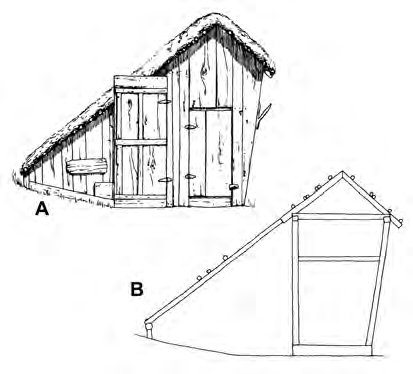

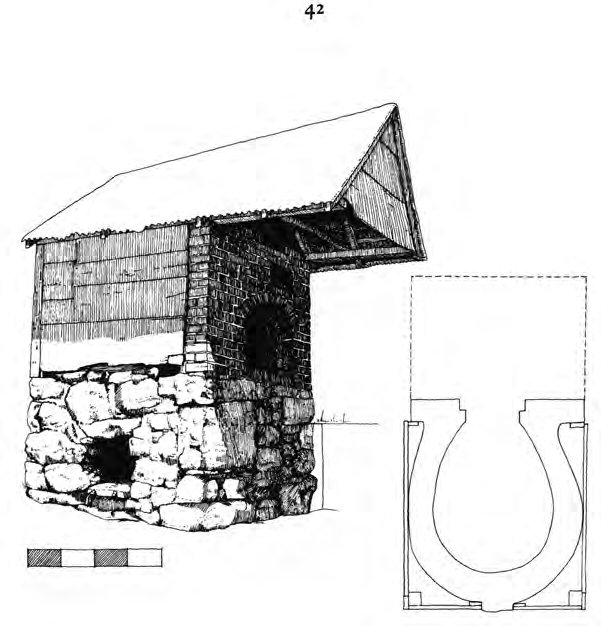

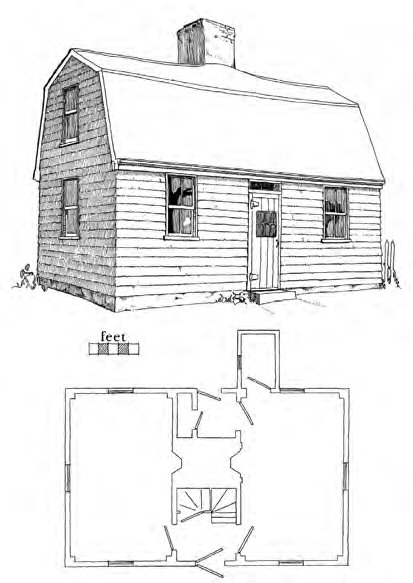

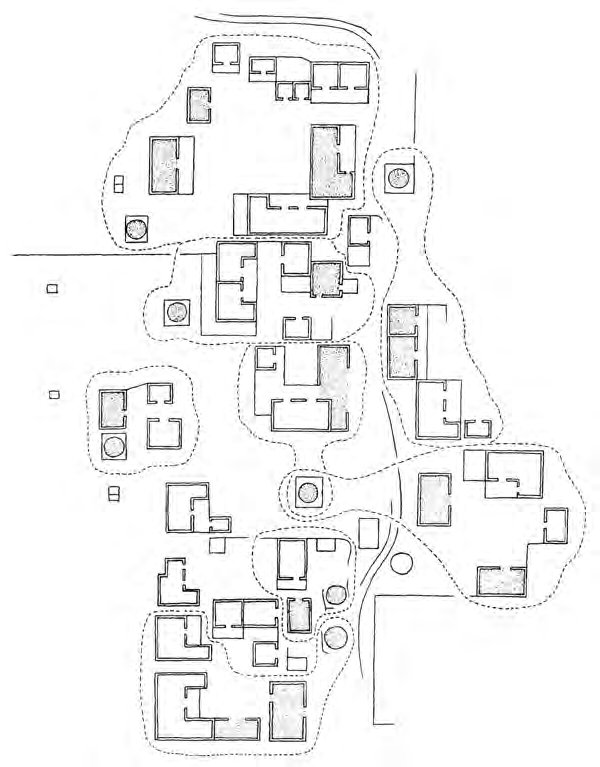

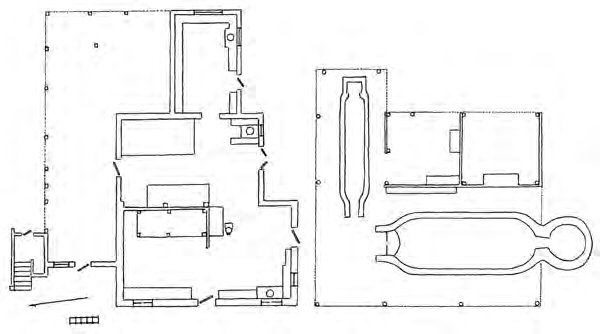

72 So, if it happened in 1760 in Virginia, it should happen around 1900 in Ireland. And the reason that was beneficial to me was that nobody had studied contemporary Irish buildings. They’d only studied the earlier traditions. So, I knew what the earlier tradition of buildings were, and I knew the earlier tradition of buildings in the west of Ireland was exactly like the earlier tradition of buildings in Middle Virginia. That is, they were open and asymmetrical (Fig. 24). I had to theorize that somewhere around 1900, what would happen is those buildings, they’d suddenly get closed and symmetrical. If my theory that in advance of a revolution, in advance of a political-military act, the culture has to change for that political-military act to actually happen. That was the kind of idea. Politics doesn’t really matter. Military things are mop-ups. What really matters is culture change, and that culture change registers eventually in politics. But it’s already registered in the buildings that the people are building for themselves because that’s the intimate world. They can control the intimate world; they can’t control the big world. I had to theorize that was going to happen in Ireland in 1900 and the Irish scholars hadn’t written about 20th-century rural buildings.

Display large image of Figure 24

Display large image of Figure 24

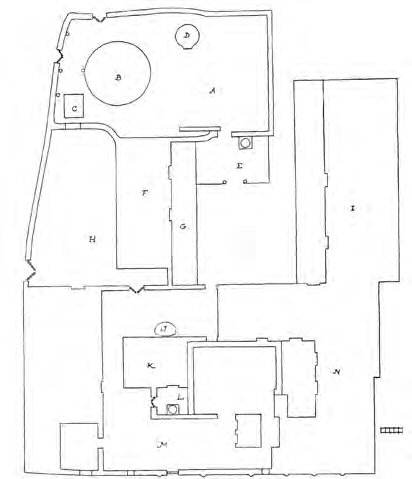

73 That allowed me to do the first real piece of fieldwork that I could do. Because I had money, I had a grant. And that grant would allow me to actually spend time doing nothing but fieldwork, and I’d never been in that situation before. When I was doing the Otsego County project, I was taking classes and I was in school. When I was doing the Virginia work, I was taking classes, I was in school, and I was stealing the time from what I was supposed to be doing. But now I could go off to Ireland. I had always wanted to go to Ireland because I loved the literature. Maybe that’s off topic here, but it’s true. So, I went off to Ireland and my goal was to test the theories of Folk Housing in Middle Virginia. In a month I knew I was right. Since the Irish event had happened a whole lot more recently, I could know that the very first symmetrical enclosed house in the rural area where I was living was built by a Protestant policeman in a Catholic neighbourhood (Fig. 25). Just the kind of person who would be anxious about change and whose anxieties about change would register in the buildings first. [A similar enclosed plan is Fig. 26]. So that in that community, that was the first and it was literally built in 1900, that is sixteen years before the 1916 Rising, just as 1760 would have been sixteen years before 1776.

Display large image of Figure 25

Display large image of Figure 25

Display large image of Figure 26

Display large image of Figure 26

74 Well, they continued to build the old-time houses until 1956. So, there’s a long period of change, and that was a corrective to what I had thought about in Virginia because I just didn’t have the evidence. I just didn’t know, really, when those houses were built. It’s like archaeologists. It was a seriation. It was a correct seriation in that these came first and these came second, but exactly what year they came in and all that kind of thing I couldn’t really know. In Ireland, I could. So, I knew that the change took a longer time to happen than I had imagined was the case for Virginia. That was a corrective. But it didn’t change the basic story any. So that what I was able to do in Ireland first was test that historical idea that had impressed me in Virginia.

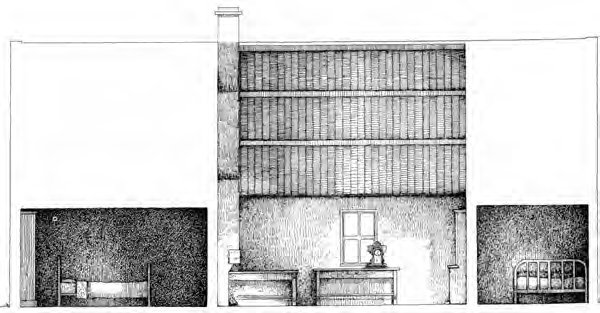

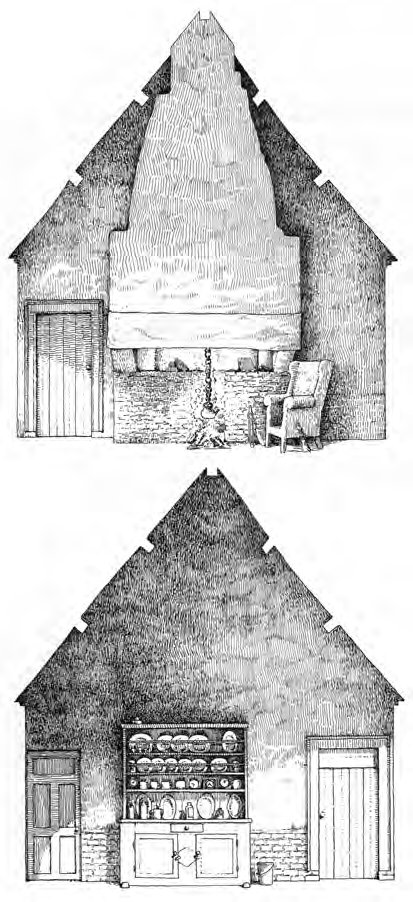

75 I was in a community where these old houses were still being lived in. They weren’t relics, they were the way that people lived. And the houses were still thatched, they were still whitewashed, they were still, for the most part, exactly the kind of houses that Evans had talked about. And what that did was to move me into a better understanding of house interiors.

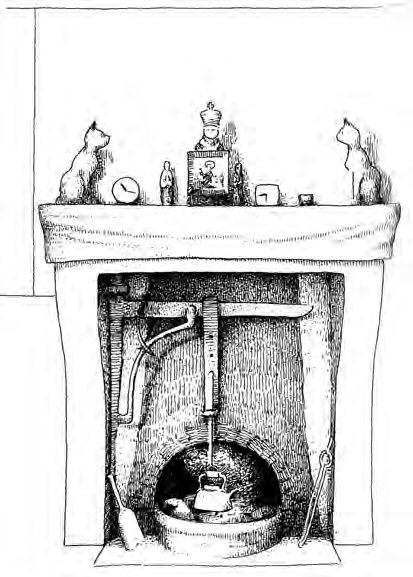

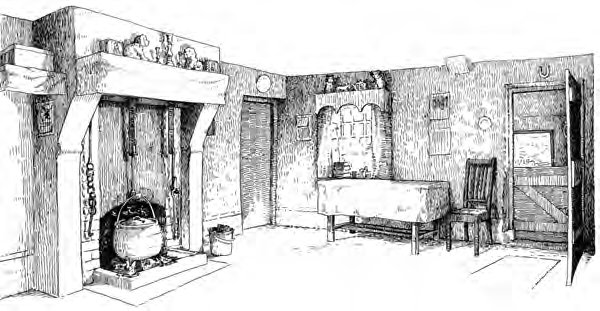

76 Why I was in Ireland, why I was in Ballymenone in south Fermanagh on the border, was to check the historical pattern that I had found in Virginia. But that wasn’t really what interested me. What interested me was that these houses were a part of the living system like I had never seen before. You know, a lot of the log cabins and so on in the mountains had been kind of abandoned. They remained, maybe someone had covered them with asbestos, you know, but the difference in Ireland was that I happened to be in a community that still didn’t have electricity, still didn’t have running water. There was only one automobile in the entire community. So it was a kind of a drop back in time. Not to some ancient time, but probably the 1930s. It was an anomalous community. And when I was talking to my friends in Dublin, they doubted there was even a place like that anymore in Ireland. But there was. And I was living there, I was documenting it. Electricity came in 1976, but I’d been there in ’72. So, I got real experience of what it was like to live with an open hearth (Figs. 27, 28). Cooking was all done at the fireplace with all these things. It was enlightening.

Display large image of Figure 27

Display large image of Figure 27

Display large image of Figure 28

Display large image of Figure 28

77 So, what did that do? That shifted my view inside. And when my views shifted to the inside, it left the men who were doing the thatching and building the houses, and favoured the women who were minding the hearth (Figs. 29, 30). And so, the story has been that by simply just following my nose, a whole sequence of changes have been made. So that from typology to traverses, from traverses to good measured plans, from good measured plans to historical understanding, from historical understanding to Ireland. And in Ireland, what I did was to really begin to think more about female homemakers than about male housebuilders. Though both were interesting. The book that reported all that came out in 1982.

Display large image of Figure 29

Display large image of Figure 29

Display large image of Figure 30

Display large image of Figure 30

78 I think that’s sort of a stopping point for more questions and so on. But that’s the course that I took. And what it had, if you were to think about it, was very little architectural history, a lot of social history. Much more anthropology, more geography than anthropology. The works that I was reading that were influential on me were mostly European. They were from Ireland, Wales, Sweden. Those were the works that I read that inspired me. But the people who inspired me, really, in the architectural business were Fred Kniffen and Estyn Evans. Evans was an archaeologist, Kniffen was a geographer. And so that geography that Kniffen practiced and the archaeology that Evans practiced, just blended with folklore so nicely. It’s kind of a rant, but that is really how I got into it. That is, it went from music to material culture.

79 But I would say that we’ve gotten to a certain point and the two things that I learned at the very beginning had to do with architectural recording and oral literature recording. And when I got to Ballymenone, I came to a conclusion for myself that I recorded the complete repertory, not of an individual, but of the entire community. That seemed to be what a folklorist ought to have done. But I don’t know if anybody else has done it. So, I recorded every single story that every single person told in Ballymenone. So that was the conclusion of the thing that began with George Pegram a long time ago, singing a country song and an old ballad in the same session. And the other thing that I did was not only, you know, sort of make a record of the houses, I made a record of every one. I actually made a measured plan of every house in Ballymenone, save one. And so that was, you know, kind of the ultimate version of all the things I’d been doing between the period 1960 to 1982.

80 And that doesn’t mean that I didn’t do new things, but actually, I felt what I did, to say it very simply, was become confident in a method that I could go and really use in difficult places. Then it was Turkey (Glassie 1993). Then it was Bangladesh (Glassie 1997). Then it was places that were a whole lot more challenging. But that method, honestly, has held together right to the present. That if I’m really attentive to repertories and if I’m really attentive to traverses and to typologies, I’ll get a record that makes some sense of wherever I am. Brazil, Nigeria, it doesn’t really matter.

The New Folklore: Shiſting Disciplinary Perspectives and The Emergence of Vernacular Architecture Studies

81 We’ve gotten to a certain point by following a personal trajectory. What I want to do now is then double back and suggest how that relates to the general development of folklore. Folklore was changing in 1964, and it was changing rapidly, primarily because it was professionalizing. Instead of being an amateur folklorist who made a living as a scholar of romantic poetry, you were now a folklorist first. I think that’s exactly what happened. In ’64 there’s this robust expansion. It’s still centred on oral literature, but there’s a robust expansion. The department at Penn became Folklore and Folklife. So, there’s a kind of willingness to gather in these other things, and this is what was happening. Now, as that happened, what everybody was doing (I’m talking about American folklore) was looking wider. The consequence of that looking came in 1972 when Dorson published Folklore and Folklife.

82 In that moment of widening to folklife, I was already present. I wasn’t causative, but I benefitted enormously from people noticing that in Europe they have this folklife. The term. The term folklife got into the United States from Ulster Folklife,32 which was a translation from the Swedish folkliv. Ulster Folklife gave the term to Don Yoder who named his magazine Pennsylvania Folklife.33 The term [folklife] in folklore isn’t used very much anymore, except by the Library of Congress,34 the Smithsonian.35

83 Those things were all developed at the same time so that what was happening in that crucial sixties period was, first of all, the expansion of the discipline and its incorporation of a more ethnographic method. The second one was exciting new topics. The third was that public folklore was invented. If you think about it, all the public folklore programs were developed in that period.

84 The first Smithsonian Folklife Festival event was in ’67. I think the key to the whole development of public folklore was Ralph Rinzler establishing the Folklife Festival in Washington, DC, in 1967. In 1967, I was the first state folklorist in the United States. So, Ralph could call on me from Pennsylvania and I could cooperate with Ralph on a number of projects, which I did because basically Ralph at the Smithsonian and I in Pennsylvania were the ones on government payrolls. That had a very simple, direct consequence. The directors of the institutions for which we worked could cooperate very easily. So, it was no problem at all for S. K. Stevens in Pennsylvania to second me to the Smithsonian a number of times.36 Ralph Rinzler and I were just working on all this because we were among the few public folklorists.

85 So, a lot of things are happening at once. The discipline is professionalizing. The discipline is expanding into public work. The discipline is in a mood of expansion. I benefitted from that tremendously because people looked around and knew that people in Europe did these other kinds of things. And for people like Dorson I was about the one who did them. So I got drawn into very many more things than I would have been drawn into. But I was actually brought in as a kind of token, almost, like a token European folklorist who had never been to Europe, but who did that kind of work. Because I knew Evans. By that time, I was corresponding with Evans, corresponding with Alan Gailey in Ireland,37 corresponding with Kevin Danaher.38 I’d not been to any of those places, but I was corresponding with Sean O’Sullivan.39

86 So, I was a person who was making these connections. I benefitted tremendously from a particular moment in folklore that lasted from ’64 until about ’72. You can put Dorson’s Folklore and Folklife at the end of that. And that’s Richard Dorson saying, “I accept architecture. I accept folk art. I accept costume. I accept food. All these things.” Because, if, for example, Don Yoder at Pennsylvania accepts those things, that’s no big deal because he was always interested in those things. Or if Warren Roberts at Indiana accepts them, it’s no big deal because Warren did that.40 So, ’72, I think, is the end of that particular era. And I benefitted personally by being fairly young in that period, and I was a kind of exemplar of a very important part of that expansion. A lot of people have negative things to say about Dorson. I liked Dorson. I think Dorson was good. He was a liberal. And he just looked and said, “You know, it’s okay to study old houses and it’s okay to study costume.” It’s not that he was going to do it. But the very last panel that Richard Dorson had at the American Folklore Society was a panel on material culture. That’s just true. It wasn’t his interest, but he embraced it.

87 In the history of this first segment, there was no resistance on the part of the people of folklore. Alan Dundes had read European work and knew perfectly well that Europeans were interested in houses and costumes, too. He wasn’t [going to study it], but that didn’t mean he didn’t understand it. And so, Alan Dundes and Roger Abrahams were the powerful leaders of the new folklore. They didn’t do it, but they absolutely embraced it. So I would say both of those men were tremendously supportive of me. I was younger, but I was doing the kind of work that they were absolutely convinced should be done because they knew that Europeans did it. Not because it was done in America, but because Europeans did it. And I just accidentally [became] a kind of European folklorist. Maybe because I’d met Estyn Evans, but more because I just liked it. I mean, really, I liked material culture. I responded to it. And I could say that first period, ’64 to ’72, is the professionalization period of the discipline of folklore, and that expansive moment was tremendously welcoming.

88 I was hired to teach at Indiana University in 1970. And when I arrived, Dorson was very welcoming to the idea of material culture. I knew that Warren Roberts had committed himself to material culture after his time in Norway so I said, “I don’t have to teach material culture, I’m interested in”—and it’s true—“all of this stuff.” So, “I’d like to teach the fieldwork class.” And I was assigned by Dorson, my first semester there, the general introduction to folklore theory. I was happy. Warren could do the houses, it was just fine. But what it meant was that in that period, say 1970, it’s the shifting period just before Folklore and Folklife came out (Figs. 31, 32).41 All this is in.

Display large image of Figure 31

Display large image of Figure 31

Display large image of Figure 32

Display large image of Figure 32

89 So, then you have students. They start showing up. You [Gerald Pocius], Bernie Herman, Rusty Marshall, John Vlach.42 A lot of people are all of a sudden interested in material culture. And it’s because it’s valid, validated. And everybody is accepting it as being part of the study of folklore. But it’s also true that it was a kind of swashbuckling period. People came in. They didn’t care that much about theories. They cared about fieldwork. And so teaching the fieldwork class, fieldwork was where it was at. I mean, that’s really where it was at.

90 I think that in the sixties and mid-seventies, there was a democratizing energy [in American history]. So, all those things combined. Folklore is in expansion. There’s a kind of sixties quality to a lot of the students who find it exciting to go out and they’re not embarrassed or troubled to meet other people. They want to meet other people! They indeed want to befriend and hang out with, maybe, right-wing people that don’t agree with them politically, but have a lot of information about, maybe, how to make a shingle roof. Who cares what their politics are? You add the expansion of folklore from ’64 to ’72 with me, bicentennial, and the democratizing of American history, and there’s a kind of synergetic exhilaration that happened right around that time. There was a reason for this all to be happening. And then the question is, how long could that be sustained? The answer was not very long. But a lot of things did happen. And the exhilaration of the people of the sixties were still going strong in the middle of the seventies.

91 I mean that people like me who were active in civil rights had a kind of energy. You know, we stopped the war in Vietnam. I mean, I was in that generation. We watched Nixon resign. Do you know how happy we were? Because we did it! By just ... you know, putting his feet to the fire. He’d be in Washington, we’d be down there screaming, you know, for his neck. So, there’s kind of a sense of victory that was there. Democratizing ... a kind of victorious thing. And then ... things slumped. I mean, in general, there was kind of a slump in the American environment. Its exploration would be interesting. The professionalization of folklore continued, but it seems to me that the exhilaration of the first generation couldn’t quite be sustained in the second generation. And that’s one of the problems. A lot of people who were really good folklorists, still couldn’t have that sensation of ... creating this thing.

92 I could have that sensation, though I was younger than, say, Alan Dundes and Roger Abrahams. I was doing something that they valorized. They thought this was right. “Somebody ought to be doing this” kind of thing. So that the next generation, maybe Dick Bauman, me, Barbara KG [Kirshenblatt-Gimblett]—Dan Ben-Amos is kind of in between—we were welcomed by the old masters. And I think that in the combination of those two generations there were people who felt they were creating the discipline, and the next crowd felt less exhilaration. “We’re not really creating this.”

93 The number of folklore departments has declined. It’s a relatively conservative era. I’m not making some original statement there, but once the democratization of America was celebrated in the bicentennial, it seems to me that historians slid back into an interest in the Founding Fathers, and those conventions. There was a moment we were talking about everyman America, and I think at the moment it has passed. I think the next generation had a hard time trying to figure out, “what are we going to do new?” when the thing had been so well done. I think there’s a slightly lost generation.

The Future of Vernacular Architecture Studies and Face-to-Face Fieldwork Within Folklore

94 GP: Why do you think there are no longer vernacular architecture papers at the American Folklore Society meeting?

95 HG: I think that’s true. To some extent that’s the direct result of the Vernacular Architecture Forum. A lot of folklorists drifted away because there was another society that met their needs. It wasn’t that folklore was an unwelcoming home, but for people who were very interested in architecture the AFS just wasn’t the place to get the best response, though there continue to be architecture panels—a really good one recently on historic preservation.

96 But what I think, if we think about the future of vernacular architecture studies within folklore, we have to reckon with large cultural changes. The two things that drove the exuberance of vernacular architecture studies in the past were, first, the desire to do fieldwork and, second, solving historical problems.

97 The people who come into folklore today, generally speaking (there are exceptions), don’t want to do fieldwork. Fieldwork is a little bit hard. You know if there’s a word for our particular age it’s comfort. There’s comfort food, desirable feelings of being comfortable. People say, “I don’t feel comfortable with this. I don’t feel comfortable with that.” Fieldwork is about discomfort. You endure discomfort to learn something new. If the desire is to stay home in comfort, you’re not going to go out and seek discomfort.

98 I have, in fact, enjoyed difficult environments. Ireland during the Troubles, the heat of Bangladesh. Now Pravina and I are doing fieldwork in Brazil, right on the Equator.43 People in Canada can’t imagine that heat, and what else?

99 Mosquitos, sickness. You get hurt in fieldwork, seriously hurt. So if the main thing you want is comfort, fieldwork is not for you. The point is to learn to endure discomfort. You know, I lived all that time in Ballymenone. I was living without electricity, without running water, just like everyone else around me. That was instructive, but it surely wasn’t comfortable.

100 So, one of the things that seems to be characteristic of our era is that people want to be comfortable, physically and socially comfortable. And so you think, “What can I do that’s just absolutely comfortable?” I would say, absolutely unchallenging. “Well, I’ll just stay home and look at the computer and do Internet folklore.” There’s no need to do Internet folklore. Our job is to get information that is not available through the conventional media. Ralph Rinzler defined folklore as the art which is not supported by the capitalist system. The Internet is a function of the capitalist system, a mechanism to make the rich richer and the poor poorer. It is an advertising medium. I stay as far away from it as I can, but if people want to study it, that’s all right with me, but for me, folklore is alternative, oppositional, and the Internet is anything but alternative or oppositional. It is complicit in the system of oppression.

101 I’m on a rant here, but the point is that it is comfortable to sit in front of the computer where you’re not challenged by the weather or mosquitos or people you don’t understand. So, one of the things that has happened to folklore is that people want to be comfortable, which means they don’t want to do the fieldwork you’ve got to do to study vernacular architecture. And the second thing is that people are not much interested in history. And the truth is that vernacular architecture’s greatest virtue is what it teaches us about history.

102 So if you want to study—and I can use myself as a good example—the contemporary creativity in any place—Turkey, Bangladesh, Brazil, Nigeria—architecture is not the thing that teaches you the most. It just isn’t. Architecture really teaches you a lot when you are trying to find out about people who are no longer here, about people who built buildings centuries ago. There’s no reason we can’t study architecture as part of the contemporary scene, except you can get the results, the results vernacular architecture can provide, much quicker through interviews and watching people in action. It’s just true. So, it doesn’t mean that I don’t study vernacular architecture anymore. I do and always will. But it is usually as an adjunct to a living tradition, let’s say, as I’ve done in Turkey (Figs. 33, 34), or in Bangladesh (Figs. 35, 36, 37), or in Brazil. Vernacular architecture is just not the thing that calls me most loudly today.

Display large image of Figure 33

Display large image of Figure 33

Display large image of Figure 34

Display large image of Figure 34

Display large image of Figure 35

Display large image of Figure 35

Display large image of Figure 36

Display large image of Figure 36

Display large image of Figure 37

Display large image of Figure 37

103 But if I want to know history, it is the most important thing. There is no historical source that we have that is better than vernacular architecture. I’m firmly convinced that the landscape is the most important text we have if history is the goal. W. G. Hoskins,44 Estyn Evans, and the other historical geographers were right. If you want to know about the past, then look at the landscape (Figs. 38, 39). You can read the archival record until your eyes fall out, but you will learn a whole lot more and a whole lot quicker by going out into the field. That is the case for history, but if you are interested in contemporary culture, vernacular architecture is useful but—I’m being honest here—I think it will only rarely prove central.

Display large image of Figure 38

Display large image of Figure 38

Display large image of Figure 39

Display large image of Figure 39