Interviews & Reflections / Entrevues et réflexions

Robert Blair St. George

Interview and Introduction by Thomas Carter

Introduction

1 During the 1970s and early 1980s a number of young folklorists were drawn to architecture and material culture as a field of study. One of the most influential of these is Robert (Bob) Blair St. George, now a professor in the History Department at the University of Pennsylvania. His major publications include Conversing by Signs: Poetics of Implication in Colonial New England (1998), Material Life in America, 1600-1860 (1988), and The Wrought Covenant: Source Materials for the Study of Craftsmen and Community in Southeastern New England, 1620-1700 (1979).

2 Bob’s story is instructive for not only does it shed light on the state of folklore studies during this time, but also helps us understand the contribution folklorists made (and continue to make) to the field of vernacular architecture studies. Bob, like many others, found that folklore provided an open, interdisciplinary framework for studying ordinary buildings, both past and present, while at the same time affirming the growing acceptance of such objects as primary evidence. In this way, folklore became an early player in the nascent field of vernacular architecture studies, with its emphasis on fieldwork and documentation, including drawing. The following excerpts come from a conversation I had with Bob at the end of May 2019.

Hamilton College

3 Robert St. George (Fig. 1) was born in Oceanside, New York in 1954. He moved to Towson, Maryland when he eleven. He was introduced to historical studies in high school, but began to take the profession seriously as the result of a number of chance encounters during his years at Hamilton College, in Clinton, NY (1972-1975). At Hamilton, Bob ended up a studio art major.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

You had to take like three art history classes, so I picked one that was called “A Survey of Modern Architecture.” That’s where I hooked up with people at Boston’s Child’s Art Gallery. I worked on the experimental etchings of a Philadelphia artist named Joseph Pennell, of which they had a collection ... I ended up putting together an exhibition and bringing it to the college. I gave a public lecture, when I was a sixth semester junior, which was a really great thing to do. Little did I know that I would end up majoring in all that stuff. It was a great thing that I could do that kind of applied stuff. I think I did a little bit of preliminary primary work during that whole escapade which has become part of the way ethnography works, or the way ethnographic history works. I was thinking that by primary I meant not what most historians think, as like a verbal/written document. And vernacular architecture is primary stuff, it’s not secondary. It’s something that shapes, or it constitutes what you’re up to. It’s like a baseline of what kind of argument you need to make about a bunch of people or the things they possess. So that’s what I think of primary sources. It’s like material things.

Historic Deerfield

4 During the summer of his junior year at Hamilton, Bob interned at Historic Deerfield, working under the tutelage of Donald Friary and Kevin Sweeny. This was the summer of 1975.

Don [Friary] had gotten his PhD at Penn with Anthony Garvan. His dissertation, which I’ve looked at, was called Anglican Church Architecture in the Northern Colonies, or something along those lines. And then the assistant person, who is now fully tenured and probably retired from Amherst, was a man named Kevin Sweeney. He was there as the assistant to Friary in teaching. Kevin was just trained by Edmund Morgan and he was entirely self-taught as a material culture person, which I really liked about him. He started with gravestones and then he worked his way into 18th-century Connecticut River Valley stuff. I liked Kevin Sweeney and his work.

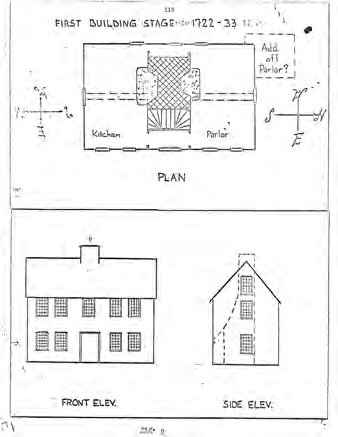

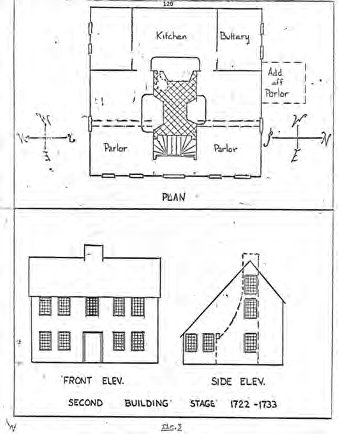

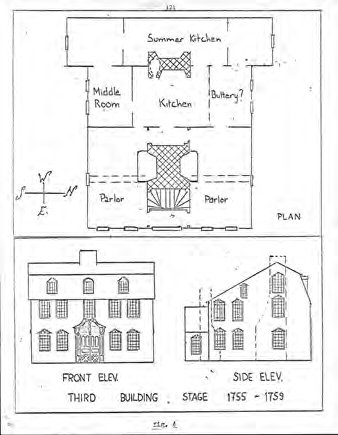

And, as it turned out, there’s a bunch of people working on miscellaneous topics, and then there’s a few people who get to work on whole houses and do a social history based on some primary work on a building. So I got to work on this one building that was part of the museum complex called the Thomas Dwight House. The Dwight House had been moved to Deerfield in the 1920s and it had originally stood on a strip of South Springfield in the town of Springfield. The first part of the house was built in the early 1720s. By the time they moved it to Deerfield, it had been enlarged a couple of times. They thought when they moved the house that it was the way it always had looked, which I proved wasn’t actually the case. That was the first time that I wrote anything on a vernacular house that had a really dramatic history. It was traditionally dated in the village that it was built in the 1760s, but I proved that it was actually built in the early 1720s in Springfield. I looked up the deeds, I measured all the plans, I found newspaper articles about it when it was moved, and the like.

[Friary and Sweeny didn’t draw] but they told me to go out and draw and were interested in me looking at the periodization. I must have based my drawings (Figs. 2a, b, c) on J. Frederick Kelly’s book Early Domestic Architecture of Connecticut (1963). I must have. It was the only thing that was around. I probably got some help. Not from these teachers, but from other students who were also just past their junior year. There was a really kind woman, whom I’ve remained in touch with over the years. Her name was Mary Spivey, who was a student Smith College and came from St. Louis. She helped me measure some things, and I suppose Lee Magnusson probably helped as well with some things. Lee was from Kendrick, Idaho.

The year before I was at Deerfield, there was a person that I’ve remained in touch with, named Sumpter Priddy. His first initial was J. Sumpter Priddy. He’s an antique dealer in Alexandria, Virginia, although he may be retired now. He also published a large book on fancy furniture in the Early National Period. He worked on a house right before I did, which was not suffering from the same problems in Deerfield. The house is called the Sheldon-Hawkes House. I think I maybe talked with him on the phone about what he would have accomplished if he had been able to work on it for more than ten weeks. He said, “I really would have worked a lot more on the building.” I really think he approached it out of records, the old court and probate records. When I did it, I wanted to look more at the building itself.

Display large image of Figure 2a

Display large image of Figure 2a

Display large image of Figure 2b

Display large image of Figure 2b

Display large image of Figure 2c

Display large image of Figure 2c

Ralph Lieberman

5 Bob’s connection to vernacular architecture continued that fall during his final semester at Hamilton. Architectural historian Ralph Lieberman was teaching at Kirtland College (Hamilton’s all-woman sister campus) and Bob enrolled in his course.

The class I took with him was on American architecture, and I think it was the only time he ever taught it. My paper [for the class] was probably called “The Churches of Oneida County.” Because one of the earliest, by any means, from 1815 was the chapel at Hamilton by Philip Hooker. I’d like to use [for this piece] that brick church (Fig. 3). I also had a plan of it. It had two front doors. I liked that building. It was a Baptist church in Vernon Center, New York, which is in southern Oneida County. I found that it was common to have two front doors in New England. And Philip Zimmerman did a Boston University dissertation just on the double door New Hampshire churches (1985). The only doors into the place were through the front, and they were on either side of the pulpit against the front wall. If you got there late, it was really hard to walk in without being shunned.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

Historic Annapolis

6 After graduating from Hamilton, Bob applied for and received another internship, a month long “research desk” at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. There he studied the pattern books of Batty Langley, a prolific writer of architectural manuals. He then returned to Maryland, where he faced the standard post-undergrad question: What am I going to do now?

I looked in the ads. The Baltimore Sun paper had a special article about Historic Preservation in Maryland. The article mentioned that there was an important place in Annapolis, which was only an hour’s drive from my parent’s house. So, we drove down. I wrote a very earnest letter saying everything that I had done, just figuring I’d send it out and see what happened. But I was called in for an interview and I got a job! It was really kind of odd. Historic Annapolis is the name of the shop, and it was directed by two women for a long time. The longest serving director was St. Clair Wright. She had been serving for about twenty-five years. There was also another assistant named Pringle Simmons, and they were who I worked with. One of the things they had me doing was building an exhibition in this little building that served the William Paca Garden, that had a floor plan of fifty, maybe seventy-five feet. It was behind one of those buildings that they owned. The building had a single common fence all the way around, and the garden behind it goes all the way to the walls of the Naval Academy. I worked on that in the spring of 1976. And the exhibition stayed up for ten years, until 1986.

Winterthur and Benno Forman

7 While working at Historic Annapolis, Bob met Gregory Weidman. Gregory was a curator and had gone to the Winterthur Museum’s Program in Early American Culture. As Bob explains, “When I heard about the Winterthur program, I said, ‘I want to do that.’ She wrote me back a separate note saying, ‘You probably won’t get in. It’s really hard to get in.’ But I did.”

Benno Forman was my main advisor while studying there—which meant you were going to work on 17th-century [New England] stuff. And by that time, Benno knew that [Robert] Trent had done Middlesex County. He [Benno] had done Essex County. So, I did Plymouth County and Bristol as well as the eastern counties of Narragansett.

This was around the time I met Robert Trent, who had already published his chair book, Hearts and Crowns (1977). He was a couple years ahead of me at Winterthur. He had learned from Henry Glassie and was at Winterthur when I got there in 1976. Benno had done his own work on Essex County, which is northeast of Boston, around Marblehead and Ipswich. In looking at counties, I mean we were looking at all the objects within a county. This is what led to my thesis, Style and Structure in the Joinery of Dedham and Medfield, Massachusetts, 1635-1685 (1978).

Benno would take us into the museum with a spotlight, and that’s what I remember most about his teaching. He’d say, “Go into that room, and I’ll be there in ten minutes. Pick two things that you think are really cool or great, and I’ll be there to look at them.” So, he did. He brought along the spotlight, and we took drawers out, or a case out, or whatever it was we wanted to see.

We would talk about objects as evidence before. What Benno would teach you was to look systematically at a large group of stuff. When I eventually went into folklore, that was the biggest lesson I had taken away from Benno’s teaching: always look systematically at a lot of stuff. Not one really cool thing, but rather, a hundred and twenty things. Like Henry in the Virginia book [Folk Housing in Middle Virginia (1975b)] says, “I left out a lot of stuff, but only fifteen houses matter.” I thought that was a great problem on how to deal with a large body of stuff and then really find the ones that matter.

The Wrought Covenant

8 While at Winterthur, Bob applied for and received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to put on a furniture exhibit at the Brockton Art Museum. The accompanying catalogue was one of the first to include Bob’s interpretive drawings.

I finished Winterthur in May of 1978, and by then I had already started working up in Boston at the Brockton Art Museum. It was Benno who had really gotten me into the whole New England thing. They all worked on the 17th century up there, but the thing about Benno was that he taught you how to look at stuff. That’s what he did. He taught you how to look in a systematic way at a lot of stuff. By the time I went up to New England, I had already developed a sort of furniture worksheet.

I first got into drawing by trying to examine furniture. You could draw a panel and you could find the compass marks that they relied upon to lay out carved panels. It was a high mannerist design, as my friend Bob Trent would have said. I don’t know where or when I moved from just doing duplications of carvings to thinking about how I could draw all these other details of joints that I could attribute to the work of joiners in specific towns. I think I just made them up—I don’t know where I got the idea to draw those.

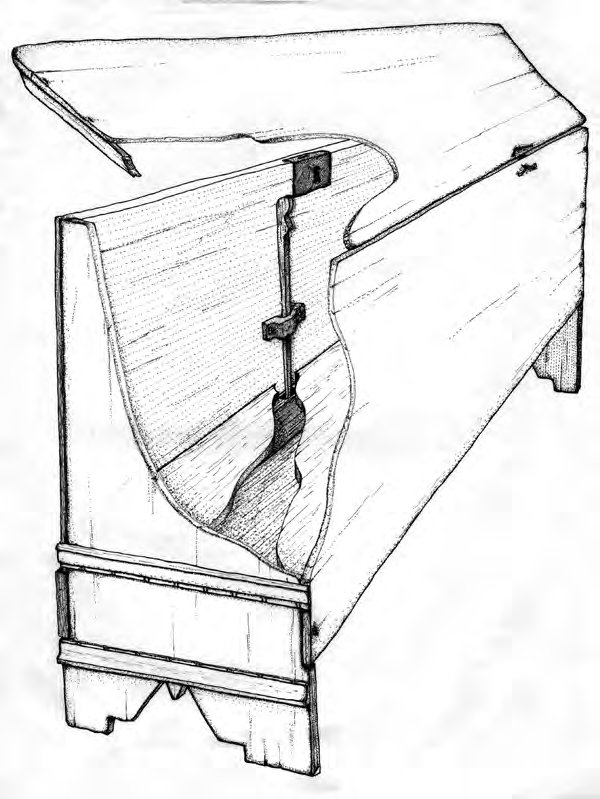

Anthony Wells-Cole worked at the Temple Newsam House in Yorkshire, England. He was one of these people who was always measuring stuff. He would take photographs and then try and draw over what he saw. He was able to send them to me in the pre-email days. I think I saw a couple of his drawings that he sent to me. He really wasn’t that great of a draftsman. So I figured I could outdraw him anytime. So, some of my drawing was in part inspired by that. But some of the other weird drawings that I did, including this one (Fig. 4) ... Well, I really just drew that because I wanted to show the sliding lock back there. It held the drawer in place. I made up that cutaway view and then tried to draw those curves so that people could see it without losing a sense of where it was.

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

From Furniture to Buildings

9 Bob’s work on New England furniture brought him increasingly into contact with the early buildings of the region, and gradually his interest shifted to architecture.

I think I gravitated away from studying 17thcentury furniture and shifted towards buildings because I felt that buildings were more complicated subjects than just looking at a chest, for instance. I had looked at the joinery and I had published articles on it. I knew about it. I could keep doing it, had I felt like it. But something about it was less complicated than buildings. There were more decisions to understand and think about, more to write about in a building––or even just a gravestone. And the same goes for any other kind of thing that has stayed in one place long enough to be able to trust.

I think the first was that I wanted to study something that was internally more complicated. That’s what really brought me to buildings. I knew that to unpack them could take the rest of my life. And so far, it’s taken me at least until now. I don’t know where I learned that from. Maybe it came from [Henry] Glassie in his writing or his lectures. Maybe I understood by talking with Abbott Cummings up in the Matthew Cushing barn, discussing that these buildings were complicated and had really deep and often times confusing evidence even to read.

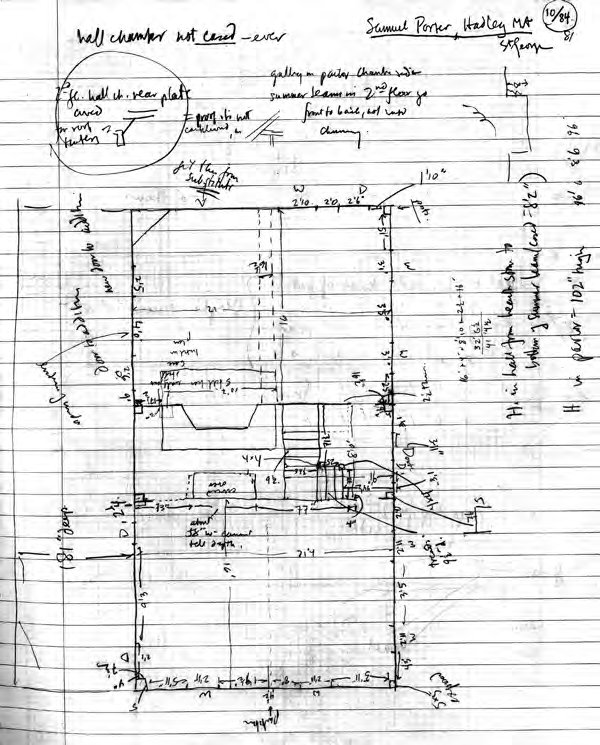

I had to be able to draw anything in a building, whether that was a floor plan or section, initial build or subsequent addition (Figs. 5, 6a, b). And I had to represent it in a way that people who read my work would really have a sense that I was writing about something complicated. Overall, I think that’s what won me over to buildings over furniture. I had lots of friends that studied furniture and stayed with it, but I was not among them. I wanted to join forces with people who were studying it [architecture] already, and I didn’t see that much of it in American studies or other sects of history.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6a

Display large image of Figure 6a

Display large image of Figure 6b

Display large image of Figure 6b

Folklore and Folklife at the University of Pennsylvania

10 Bob studied at Penn from 1978 to 1982. Folklore and folklife provided the kind of interdisciplinary training he was seeking.

At [this] point I was searching for graduate programs where the action was in material culture studies. Like most Winterthur people, I applied to Yale, however, I didn’t get enough funding to warrant going. It was also clear that the kind of stuff going on at Yale was like what Jules Prown and John Singleton Copley were focused on. The people in the art gallery were curators and they were interested in things like mirrors or chest of drawers. There was also Pat Kane, who was basically the senior curator, who had done a catalogue on early stuff. I wasn’t really interested in any of it.

I went into folklore because it seemed to be such a multi-disciplinary approach of understanding. Sociology was part of it, as was sociolinguistics, due to Henry’s alliance with Dell Hymes. We had to read a lot of sociolinguistics. We had to read about all genres, performance studies, and all of those things put together. It seemed to me, that folklore gave you the intellectual ammunition to look at a given thing—such as a building that is internally complicated to a vexing degree—from a variety of viewpoints. I think that’s one of the things that I really took away from folklore. Folklore was a way of looking at things from a variety of perspectives that all intersected in one field. I studied with Erving Goffman for two semesters. I also studied with Ray Birdwhistell for two semesters. I also studied with maybe three or four folklorists that were also there at that time.

I started at Penn in the fall of 1978. Henry taught a class in architecture while I was there in either my second or third semester. It was a large class with around sixty people in it. It was a very strange thing called a “graduate lecture class.” It was a mixture of topics pertaining to Virginia and a little bit from Ireland that related to All Silver and No Brass. It was published in 1975 and is a very well-written book, in my opinion (see Glassie 1975a). I’ve used it on and off for teaching over the years. I also had a full semester of reading the work of Lévi-Strauss in order with Glassie and an English scholar, Simon Lichman. I suppose he went back to the UK eventually. I learned a lot from reading all of those things.

I also think that my interest in folklore was related with the rise of populism at the time as well. There was always a jam session going on at the early AFS meetings. Sandy Ives would be there and Roger [Abrahams] was still able to sing. It was basically what I later learned to be a ceilidh, or a hootenanny, or something like that.

And of course, I had read all of Marx, which had made me more sensitized to looking at that material as a way of linking it up with buildings and folklore. The new social history hooked up with what I had been reading, and together they all connected to what I was thinking about folklore, in terms of being multi-disciplinary.

When I started folklore classes at Penn, the people there had never heard of any of this stuff that I was doing. They came to Penn to work on proverbs or riddles. Anything related to that kind of oral genre stuff. They had absolutely no idea what I was up to. And they just told me so! “You have no idea what you’re really up to!”

By the end of my dissertation in 1982, I had really shifted over to buildings. It was called A Retreat from the Wilderness, rather than buying into Perry Miller’s Errand into the Wilderness (1956). It was about folk architecture in New England. I think I picked the first part of the subtitle from Henry’s 1968 book, Pattern in the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United States. So, I think I called it Pattern and the Domestic Environment in Southeastern New England, 1620-1720.

Influential Teachers: Abbott Lowell Cummings and Henry Glassie

11 Two seminal leaders in the vernacular architecture studies movement of the 1970s and 80s were Abbott Lowell Cummings and Henry Glassie. Bob St. George is one of the few who studied with both. With Abbott, the connection was informal and occasional. Henry was his advisor at Penn.

I first met Abbott Lowell Cummings in 1975 when Donald Friary led us on the Boston field trip. Really, it was Abbott Cummings who led the trip. He took us on about a three-hour walk through the major different sections of Boston in that summer of 1975. After that, I don’t think I saw him again until 1979 or 1980 when I was working, primarily in the summers, for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. He would come over for meetings concerning the New England Begins catalogue.1

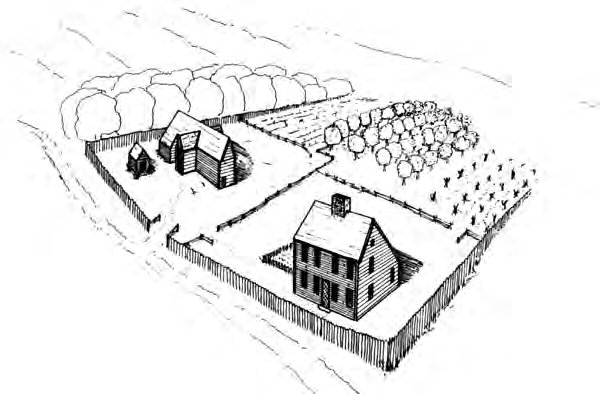

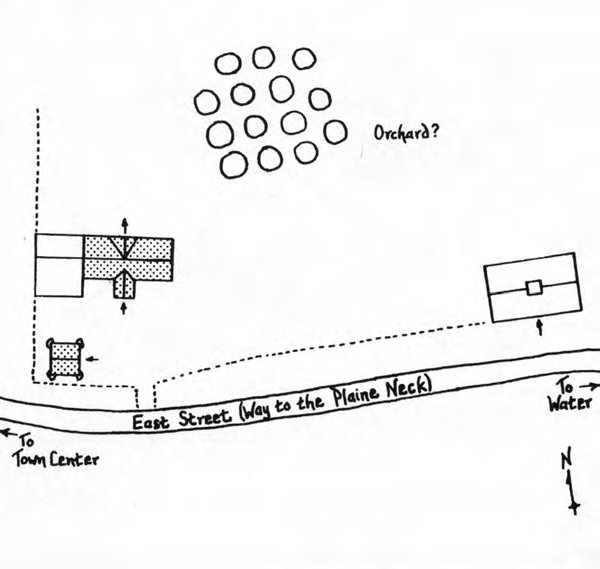

I also had a couple of sessions with Abbott in the field. But that was in the early 1980s, maybe even 1984. I remember sitting in his office at 141 Cambridge Street in the old SPNEA [Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities] building. And he said, “What are you interested in?” You know, expecting me to say this house or that. Instead, I said, “I’m interested in farmstead design and barns in particular.” Because houses were always part of a farmstead, correct? Abbott responded, “Yes, my boy! What a great idea! About which I know nothing. But I know one great farmstead to go to. And I know another really great outbuilding to go to.”

So he took me down to the Cushing place to see the very great connected barn and corn granary (Fig. 6a & b) that’s there that could all be dated. After that, he took me up to see another building at a place on the North Shore of Massachusetts that was attached to the so-called Barnard House in Saugus. It’s a really great outbuilding and I have a sketch of it in my drawing collections.

I never did go out with [Lawrence] Sorli.2 No, never with Sorli. However, I went out with Abbott a bit and he showed me what to draw. I drew exactly one building for him and it was behind the Parson Barnard House. He brought me back there to look at it and then said, “Make a drawing of this for me.” That’s one thing that really mattered to me about Abbott. He trained me to do a little more documentary sleuthing after I had measured buildings. The buildings came first. But then you would figure out what questions do I have to ask to get more information on the building through the title search?

I suppose it was Abbott who taught me how to do a proper title search before looking at other kinds of records. Then I started doing it all on my own. In the days before I had a firm commitment to that multi-disciplinary approach to folklore and folklife, Abbott taught me to draw first and do research later. You had to have the thing understood first. And he said the hardest thing is to understand the object. Abbott often discussed the importance of drawing even though he didn’t do it himself.

Henry was different, he taught more through inspiration and example. Both Pattern and Folk Housing became sort of manuals that we carried with us into the field. One of the things about Glassie’s work and his drawings make very clear is that he’s got really exact data, but he also loves to write it up in a theory-rich environment.

One can never really be sure whether or not theory is driving the data or whether data is driving the theory. Theory matters because it allows cross-cultural comparative work. And that’s something that I’ve always seen as one of the key methods in the world of folklore or folklife studies. I’m never sure with Glassie. I think he probably wants to get really exact data down so that he can generate a kind of comparative frame, whatever that might be. I have always found that a difficult thing to do because the world of just getting things measured and doing so correctly had such an aura within itself.

In terms of inspirations, I still think that Glassie’s work matters. I read the footnotes more than I read the text, just to keep up on the literature in the given field. I have trouble reading through the text. I might read the intro and outro, glance at the table of contents, and then start reading the footnotes. However, that big book that Henry did, Passing the Time in Ballymenone (1982)—that book has the biggest footnotes. I love to read and look at his drawings.

Vernacular Architecture Forum

12 As his interest grew in studying buildings, St. George found colleagues in the Vernacular Architecture Forum, a scholarly organization founded in 1979 to further the study of ordinary buildings in the United States.

I can’t speak for the motives of the historic preservation crowd, let alone all of the university people now. But I’ve always felt that I’ve learned a lot from a lot of different people. For instance, I talked to Catherine Bishir yesterday. I hadn’t really had a nice chat with her in a couple of years, so I stopped her yesterday and just caught up with her. She was a person I’ve always found to be very supportive over the years. I found that there were people in the South that were studying these kinds of things early on, including Carl Lounsbury, Catherine Bishir, and Ruth Little. And Bernie Herman too, when he was in Delaware for so many years.

I always felt that I was surrounded by people. I don’t know how many people live in Philadelphia that are doing what I’m interested in. I didn’t ever meet people here, until maybe some of the preservation people in the area. [But in the VAF] I think I felt surrounded by this little group, like [Cary] Carson, Edward Chappell, Dell Upton, and the others. We discussed all of these sorts of topics.

This was all happening right around the time I was shifting to buildings. Let’s say that when the first VAF meeting happened in D.C. in 1980, there were people that I already knew who were players in this. And at that time, I was probably still making a transition from furniture to meeting all of these people who really weren’t interested in furniture. However, they were interested in two things: they were interested in different communities or groups of people. This included Bishir’s attention to actually studying the architects who made these things, such as Jacob Holt. All of a sudden, we had a builder’s name and someone writing about these things, and a name for the discipline too. I thought that was a great thing.

Boston University, 1984-1988

13 Bob’s next stop was at Boston University and the American and New England Studies Program.

I started teaching at Boston University in 1984. I began with a course on vernacular architecture. I advised six or seven dissertations while I was there. It was a good place to work.

Richard Candee [was there]—I had met him when I was at Deerfield. He gave a lecture. He had studied at Cooperstown and was already at Boston University. Richard was a good colleague. Candee taught the history of preservation and that was probably one of his major courses. Because he was running a program, I think he only had one course to teach a semester. That program was good and he brought in some really excellent people. However, Candee wasn’t a fieldworker. He was more like Abbott, in that respect. Sort of the same ilk. If I had his dissertation, you know, I’d put it in the same pile. I mean it doesn’t matter in that he was such a player in New England studies, as well as in the preservation group.

University of Pennsylvania Department of Folklore and Folklife

14 Bob taught in the University of Pennsylvania’s Folklore and Folklife Department from 1989-1999. While he was teaching in the Folklore Department, Bob wrote the seminal book, Conversing by Signs, which was published in 1998.

At Penn, I had as colleagues some of the same people with whom I had earlier studied as a grad student, including Kenny Goldstein, Dan Ben Amos and Don Yoder. Each one of these teachers had a very different pedagogical approach. I also met people in many other departments. There was a person teaching in landscape architecture in the Graduate School of Design named Dan Rose. He had a book that Sage Publications put out just on ethnographic method. I learned a great deal from Dan.

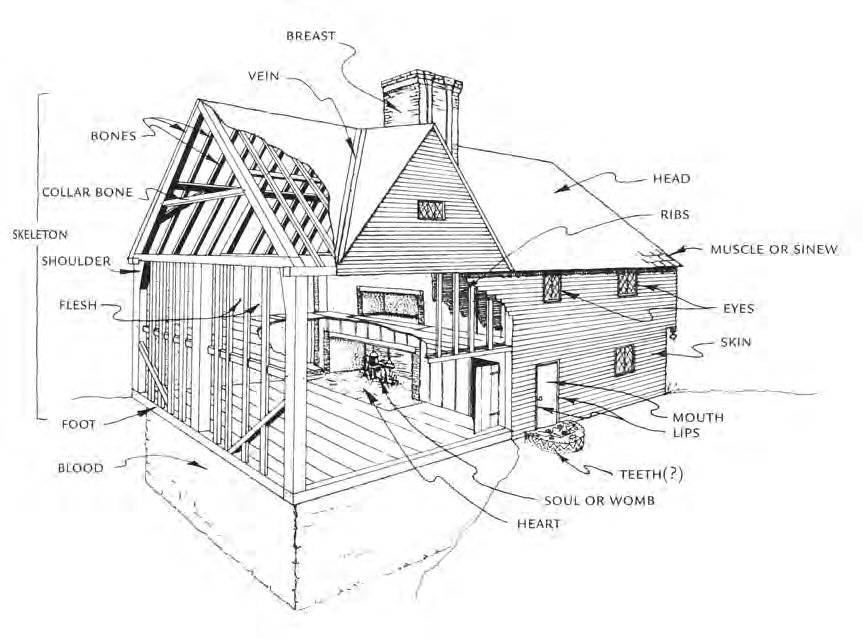

Well, I think what I said before: that I went to folklore initially because it was multiapproached. Therefore, I was able to look at buildings within folklore from a sociolinguistic or poetic point of view. What I tried to do in Conversing by Signs was to raise some of those questions about how to look at a building from a multitude of perspectives, which is the way I think about buildings. That’s my way of thinking about them as a folklorist. I believe that folklore still has this multi-disciplinary focus, even if nobody else knows this. And that’s what gave me almost a sense of extreme license to look at things as I mentioned in the intro to the book. I believe the reference was a “visual-topiary of signs.” It was a way of connecting older studies in vernacular architecture with much newer ideas in performance studies and sociolinguistics. There were a lot of books which combined theory with material data and I was fascinated with them. There was the literature on the human body, such as Jean Christophe Agnew, his book Worlds Apart (1986). You know you could consider Conversing by Signs as “Buildings and Bodies” (Fig. 7). And there was the work on commodity, I think I have mentioned Wolfgang Haug. There was also Webb Keane in the Anthro Department who was a specialist in how semiotic signs worked in Sumba, Indonesia. His great early book was called Signs of Recognition (1997). Arjun Appadurai, he really helped me rethink the way commodities worked in society. He edited and wrote the intro to the Social Life of Things (1986).

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

A Folklore Method

15 I asked Bob: What do folklorists bring to the study of vernacular architecture? Is there a way of seeing that characterizes our work?

For me a folklore method includes production, use, circulation, exchange. Essentially, the life of what I’ve termed “commodity poetics.” I first got the idea of commodity poetics from reading a book by a German author called Wolfgang Haug that was entitled Critique of Commodity Aesthetics (1971). I have an article in The Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Scholarship on commodity poetics (2010).

I would probably begin with the pairing of production and circulation. That means that when I go in and start looking at buildings or landscapes, I am thinking, how did this idea come to this particular part of the world? It’s a chronological thing first. Do I really think that? I’m not sure, but I might. If you’re an architectural historian, you know style functions as temporal placement. What if we just asked a group of students, wherever they currently may be, to answer Kevin Lynch’s question, “What time is this place?” Every little spot you can occupy had its own little temporal valance. That’s what I take from that question, “What time is that place?” I think it’s a fun question to think about.

And then in terms of folklore, what time is folklore? I remember Henry Glassie once told me about a conference in Providence that E.P. Thompson attended. And Thompson, who had recently written an essay on folklore and history in The Journal of Midland History, turned to Glassie and asked him, “What do you think folklore is?” And Glassie responded, “Folklore lasts a long time and history is brief.” Classic Henry!

Folklore has trained me to think about the longue durée. Maybe history is worth like a century or fifty years. Or perhaps three hundred years. I don’t know. I don’t care that much. But I attend papers at the Annenberg School of Communication at Penn and somebody always talks for forty-five minutes on recent developments in cellphone technology. That technology lasts a total—you know, that much time!

I think if you consider that deeply held conservative idea of persisting over time then you have to ask what time is. And not everything is hooked up with the clock, right? Even E. P. Thompson did that important essay on clock time for the industrial revolution versus task time.

Ethnographic History

16 As a footnote to his thoughts on folklore methods, Bob brought up the similarities between contemporary ethnography (where you talk to people) and ethnographic history (which requires extracting narratives from written and other sources).

The problem of ethnographic history has two kinds of answers. One is that you try to find period documents, houses, diaries, court records, or similar sources. You could almost put quotes around voices in the court records. They seem so alive. And even though they don’t have quotes, I’ve often times wanted to put them in. So that’s one response. Then you start reading Erving Goffman or Henry Glassie or Michael Zuckerman. All of a sudden, you’re reading stuff that you’re bringing in from outside disciplines to make you ask very different questions in the field. That’s very different from looking at the building and then thinking about diaries, period documents, and period texts.

University of Pennsylvania Department of History, 2000-2019

17 In 2000, Bob moved to the Department of History when the Folklore Department was converted into a program and its members dispersed into other departments.

I discovered in the History Department that life was divided by geography and period and in ways I had not yet experienced in folklore. When I joined History they categorized me as a 17th-century early Americanist. Within five years that system really began to grate upon me, so I began to teach a new set of courses, including “Witchcraft and Possession” and “Performing History.” The latter course ranged from 1730 to 1920, and included all the things about societies except written words. We looked at house assaults, strike parades, and the building of monuments, among others. Back to folklore!

The Future of Folklore and Folklife

18 At the end of our conversation, I couldn’t help asking: Do you think the folklife studies movement is still alive?

We’re still alive, so it is still alive.