Research Report / Rapport de Recherche

Notes from the Field:

Architecture and Ecumenical Life in Indiana’s Whitewater River Valley, 1800-1860

1 One of the attractions folklore studies has always had for me is fieldwork: the gathering of previously unrecorded data within specific communities, emphasizing the everyday, traditional elements in the society. It started in college, when I began recording fiddlers in Vermont and has stuck with me throughout my career. Along the line I switched from music to buildings, a fortunate decision given the state of the labour market during the 1970s. My move into architectural history coincided with the creation of federally funded state historic preservation programs. I parlayed a survey job with the Utah State Preservation Historic Office into a dissertation, which opened the door for a teaching job in the University of Utah’s College of Architecture and Planning (see Carter 2017).

2 It wasn’t quite as easy as it sounds, however, since along the way I had to learn how to actually study buildings. The inspiration was there, certainly. At Indiana University students had both Henry Glassie and Warren Roberts as role models, but the particular techniques involved in architectural research were left for us to discover on our own. I knew I needed floor plans but had no idea how to get them. Luckily a friend and fellow grad student, Gary Stanton, asked me to help with fieldwork he was doing on German immigrant architecture in Franklin County, in eastern Indiana. Gary had helped Warren Roberts record some German-built houses in southern Indiana’s Dubois County, so he had the basics down and was willing to teach me. Driving through the countryside looking for old houses and barns, talking to folks about their buildings, and just getting out of the classroom, I loved it.

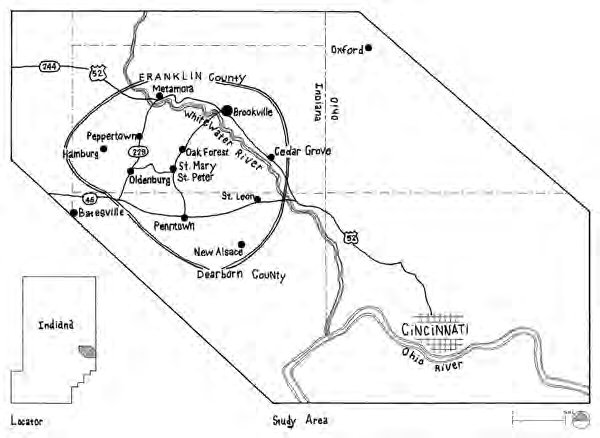

3 For me, it was several term papers. For Gary, a dissertation. But in the end, we both moved on. Me to Utah, where I was from. Gary to South Carolina and Virginia. But together we felt the pull of unfinished business in Franklin County, so for several summers in the early 2000s we returned for a few weeks of new fieldwork (Fig. 1),1 this time focusing not just on German buildings, but on the larger question of early 19th-century community building on the American frontier. We hoped for a book, but it never happened. Still, the building data raised questions about Franklin County history that should not be ignored. In this report I summarize our findings, while at the same time offering a brief overview of folklore methodologies.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

The Whitewater River Valley

4 The study began with a simple desire to know more about German immigrant architecture in southern Indiana. Background reading and several exploratory road trips pointed to the Whitewater River Valley in Franklin County as a good place for this kind of research. Lying a bit north and east of Cincinnati (Fig. 2), the Whitewater was first occupied by Europeans in the last years of the 18th century, soon after the Northwest Territory was opened to American settlement. In the 1830s and 1840s it became a prime destination for German immigrants who came first to Cincinnati and then spread into the interior looking for affordable land. While it is true that most of the central and upper Midwest bears the mark of German settlement, the Whitewater, because of its early American occupation, heavy influx of German immigrants, and abundance of surviving 19th-century architecture, proved ideal not only for studying the immigrant experience but also, and this became more clear as the project unfolded, the nature of a multi-cultural frontier society in the early years of the Republic (Doyle 1978; Faragher 1986; Clark 2005).

Display large image of Figure 2

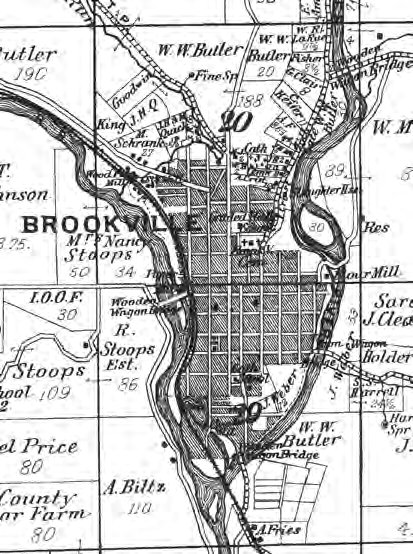

Display large image of Figure 2

5 This isn’t the place for a lengthy discussion of method (which I must say evolved greatly over the many years of the project), but from the start we followed textbook folklore protocol (Roberts 1972; Leach and Glassie 1973; Glassie 1983; Carter and Cromley 2005). First came a windshield survey (driving all the roads in the study area), then the documentation of significant individual sites (with measured drawings and photography), followed by talking with owners and residents (about house and family histories), and finally courthouse and archival research (to date buildings and get biographical background on their owners and users). Through the years, Gary and I collected a great deal of information on local farmsteads, houses, barns, and construction technologies. From this material several patterns emerged.

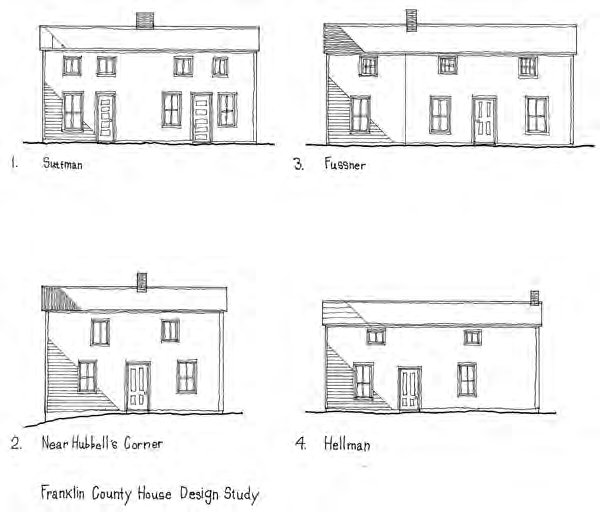

6 First, the most important factor in landscape organization here was religion. Small religious communities, whether they were American or German, typified settlement, with churches of various denominations built not only for congregational purposes but also as a means of establishing group affiliation and individual identity (Cresswell 1995). And second, when it came to architecture, religious and domestic, German settlers generally followed American stylistic precedence. Certain old-world practices survived, particularly in such things as farmstead layout, construction methods, and interior finishes, but on the whole German buildings look much like their American counterparts (Stanton 1985).

7 The word that came to mind when describing the Whitewater landscape was ecumenical, with ecumenical used in the broadest sense to cover not only religion but also society itself. The parish-centered communities were divided ethnically as well as theologically yet co-existed as a viable ecumenical whole. Personal identity came largely through one’s parish, and the existence of distinctly German parishes, set off by religion (as well as language) allowed immigrants to maintain a connection with both their home country and, by extension, their collective Germanness, while at the same time participating in the American nation building project going on all around them.

8 This last aspect of Whitewater history, the balancing act between local and national cultures, is an aspect of life here that comes through best in the architecture. Focusing on the parish landscape, historians have stressed the former, the local. In a fine study of the region, historian Richard Nation emphasizes the role a powerful “localist ethic” played in shaping the parish landscape (Nation 2005: 1-5, 38-76). But looking at the buildings, which display an ever-increasing allegiance to broader outside trends in design, I would add that it was a localist ethic that came with decidedly national aspirations.

American Settlement

9 The American occupation of the old Northwest Territory, which stretched from the Alleghenies to the Rocky Mountains, began in earnest after 1785 when the land was surveyed and made available for purchase at discounted rates (Reps 1965: 216-17). Migration into the territory generally followed the rivers, with the Ohio serving as the principal artery. A series of tributaries, including the Whitewater River, led inward and attracted first settlement. The reliance on waterways meant that the frontier moved from south to north and west. Ohio, with Cincinnati as its principal city, was the first state carved out of the former Indian lands, being added to the union in 1803. The Indiana Territory was created in 1800, with the largest settler population occupying the portion of the would-be state (statehood came in 1816) lying closest to the Ohio River (Power 1953; Reichmann, Rippley, and Nagler 1995; Hurt 1996).

10 The land itself was not particularly inviting. It acquired the “Hill Country” label early in its history, but it is more like an undulating plain, deeply dissected by stream-cut valleys with disparities between high and low ground of about 300 feet in elevation. It is a country of narrow bottomlands and limestone ridges, and marginal farmland, but—and this seems to be the key point—it was farmland, and its potential for productivity was countered by a deep-seated appreciation among both Americans and German Americans that access to land, even of lesser quality, brought personal freedom and financial opportunity. It was this idea that propelled first American and then Germans into the Whitewater country (Stanton 1985: 65-66; Nation 2005: 6-37).

11 The first settlements were to the north in Brookville and Fairfield Townships, with the majority of emigrants coming from Ohio, Pennsylvania, and the Upland South, especially Kentucky (Nation 2005:14-16). Several towns were platted by speculators, including Brookville, which was laid out with a traditional grid in 1808 (Fig. 3). Some smaller settlements followed a linear pattern, with buildings arranged in a line along a central street, though often these fledgling towns got gridded additions as their populations increased (Chappelow and Dunaway 2008; Reifel n.d.: 193-231).

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

12 Brookville was destined to become the principal market town in the valley, sharing an early prosperity with nearby Metamora, a town created in conjunction with the building of the Whitewater Canal, which commenced, according to the Atlas of Franklin County Indiana, “on the West Branch of the Whitewater River, at the crossing of the National Road [near present day Richmond, Indiana]; thence passing down the valley of the same to the Ohio River at Lawrenceburg...” ([1882] 1976: 16). Work on the canal began in 1836 and when dedicated in 1842 Whitewater farmers were connected by water to the Ohio River and downriver markets. Soon the completion of rail lines in the 1850s and 1860s (the Whitewater River Railroad utilized the old canal towpath for it tracks) rendered the waterway obsolete, but in a way, it had already served its purpose by making a positive impression on prospective settlers (Reifel n.d.: 248-52).

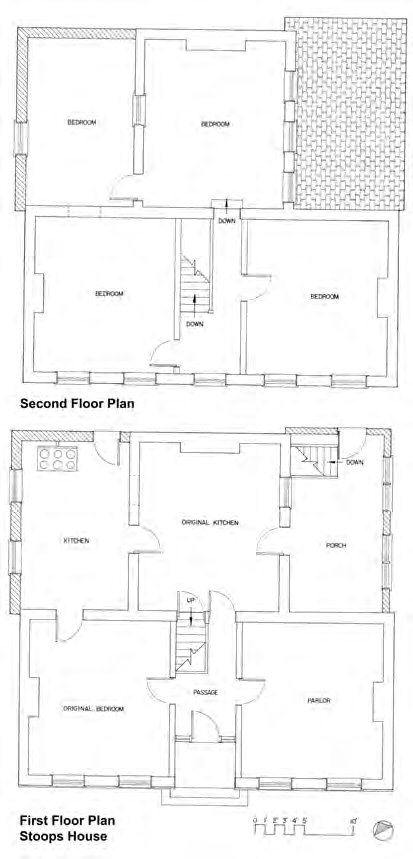

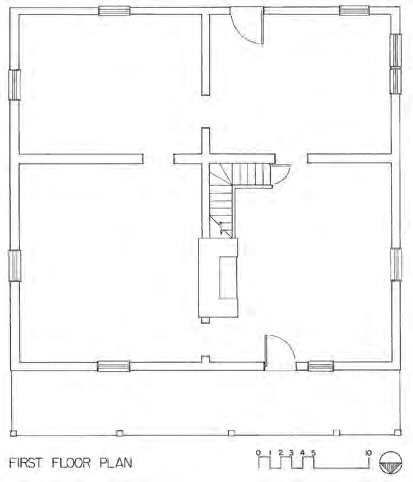

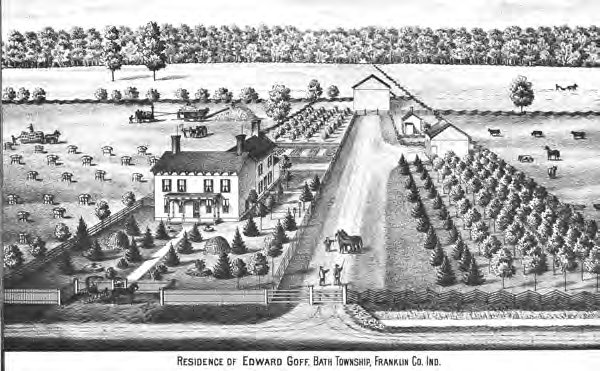

13 While towns like Brookville and Metamora are conspicuous in the historical literature, most valley residents lived in the countryside on dispersed farmsteads (Fig. 4). Scattered through the valley, individual farms varied in size but customarily had a house, a barn, and a number of outbuildings (corn cribs, hog houses, chicken coops, etc.), and while isolated and often separated by considerable distances, they were nevertheless part of an intricate network of social and economic relations built around parishes. These parishes, usually centered at major crossroad intersections, worked like small villages, with a cluster of houses and usually a tavern/hotel, a school, a few shops (almost always a blacksmith), and a church (Cresswell 1995: 59-62).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

14 A good example of an early Whitewater Anglo parish/village is the one at Little Cedar Grove, just south of Brookville (Fig, 5). The site was settled after 1806 by Baptists, almost all from Kentucky, who formed a society and built a school and church. On the map the church is depicted with a steeple, but the one at Little Cedar Grove was actually quite different. As one observer noted, the church is

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

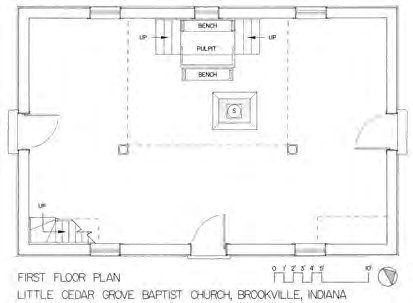

15 Finished in 1812, the building followed an older cross-axial meetinghouse design that had the main entrance and raised rostrum/pulpit facing each other along the long side walls (Figs. 6a and 6b). Once ubiquitous, meetinghouses like this by the second quarter of the 19th century were everywhere being replaced by a new steepled design that placed the main entrance on the building’s narrow end, with the door opening onto a long aisled nave that led to the raised altar (Benes and Zimmerman 1979; Buggeln 2003; Lounsbury 2011; Benes 2012).

Display large image of Figure 6a

Display large image of Figure 6a

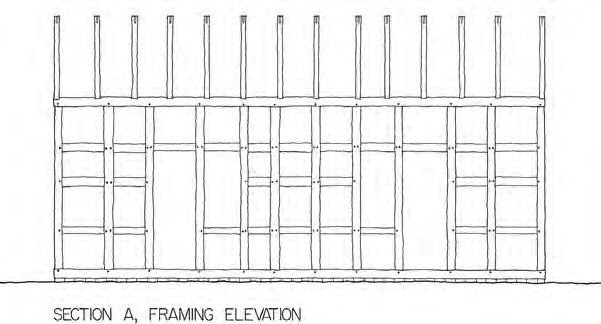

16 The role parishes and parish churches played in the settlement of the Whitewater region cannot be overestimated, for together they constitute the defining features of the local human landscape. In the words of historian Richard Nation,

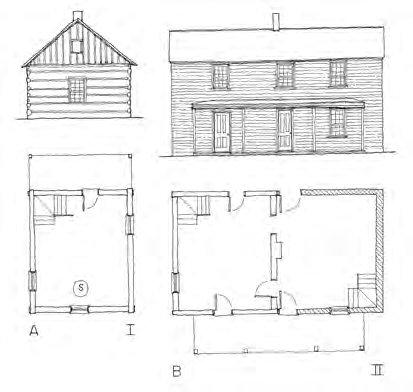

17 It is curious, however, given the powerful union between people, place, and church, that there was little interest in differentiating denominations architecturally. Except for a few evangelical congregations that favoured buildings without steeples (examples are Cupp’s Methodist Evangelical Episcopal Church outside Peppertown in Salt Creek Township and the Big Cedar Grove Regular Baptist Church in Springfield Township) most Whitewater parishes adopted the new church form, either in the Greek or Gothic fashion (Cresswell 1995: 155-81).

18 The Methodist Episcopal Church in Brookville (Fig.7), locally called simply the “Old Brick Meetinghouse,” was one of the first of these “church-type” buildings in the Whitewater, dating to the early 1820s. The roof tower is awkwardly prominent (seemingly out of scale with the building), and may or may not be original. Its form, however, a square base topped by a tapered spire, is standard, although decorative treatments vary according to parish tastes and the vagaries of fashion. For the Brookville church, builders worked in the Greek mode, evidenced in the pedimented cornice returns found on the shallow-pitched main building and the compass-headed windows placed below the tower’s hooded cornice (Chappelow and Dunaway 2008: 66).

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

19 American housing in the valley, like the religious architecture, falls into two chronological periods: the local and then the national. The first dates from initial settlement into the 1840s and is a style of architecture fashioned around log as a construction material. Most American settlers arriving in the valley came with some knowledge of log construction. Introduced into the Mid-Atlantic colonies first by Scandinavian and then German immigrants in the 17th and 18th centuries, the practice of laying up houses, barns, and other buildings with tiers of horizontal logs secured at the corners with various types of interlocking notches, proved well suited to the heavily forested Midlands. The forest had to be cleared, and the downed timber proved a readily available building material—vertical trees being turned into horizontal logs (Jordan 1985; Stanton 1985: 128-40; Kniffen and Glassie 1986 [1966]; Hoagland 2018).

20 But if convenient, the reliance on logs placed certain restrictions on what could and couldn’t be done. Walls rise in alternating tiers with notched corners, essentially producing square or rectangular boxes (often called “pens” or “cribs”) that can stand alone or be expanded by adding additional units. The advantage is that the technique produces rectilinear one- and two-room house plans consistent with traditional Anglo-American practice (Roberts 1984: 115-30); the disadvantage is that the box-like units dictate overall house design, with openings determined not by some overarching principle (like symmetry) but rather by where doors and windows could be placed within the log cribs. The overall effect of this “inside out” design is exterior irregularity, with most designs featuring an offset front door and unevenly placed windows (Stanton 1985: 110-26; Hutslar 1986: 377-422; Hoagland 2018: 25-30).

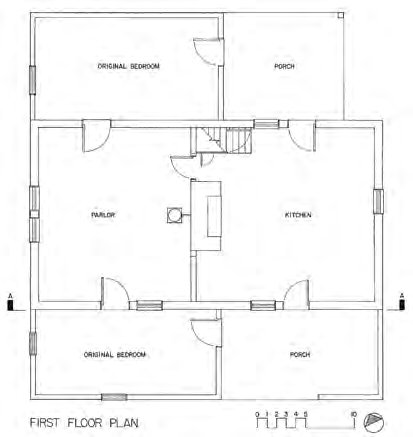

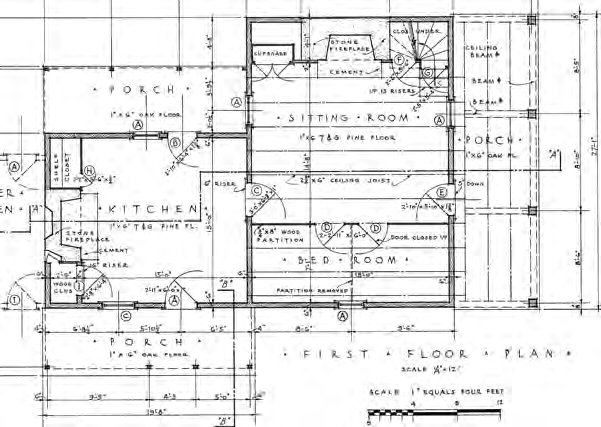

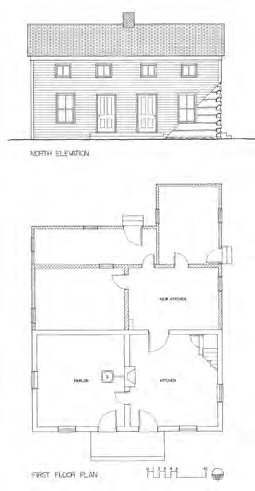

21 The Logan house (Figs 8a and 8b), one of the earliest of these log buildings in the valley, displays the classic features of the First Period style. The original log section was built in 1809 in Fairfield Township, north of Brookville, for the family of South Carolinian William Logan (the frame kitchen and perhaps the two-story front porch were added in the 1840s). The front door and window are placed symmetrically within the large, rectangular log crib, as is the single upstairs window, giving the main elevation a certain asymmetry that is typical of these houses. The interiors of both ground and upper level spaces are divided by frame partitions into two rooms each, giving the house a basic Anglo-two-room “hall-parlor” plan, with an original kitchen (labelled here “sitting room”) and bedroom on the ground floor (Slade 1983: 29-30).

Display large image of Figure 8a

Display large image of Figure 8a

Display large image of Figure 8b

Display large image of Figure 8b

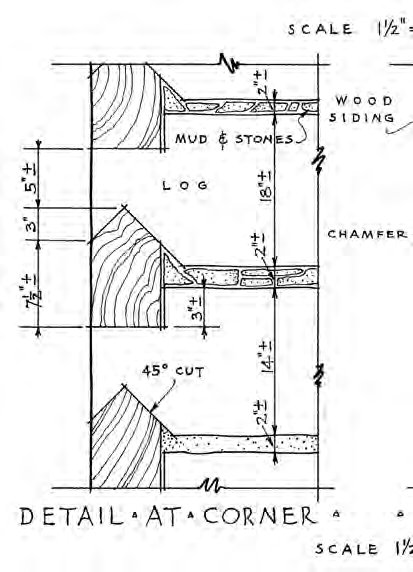

22 The log work on the Logan house is also typical for the Whitewater country (Fig. 9). The logs are hewn flat on front and back, left round on both top and bottom, and the gaps or interstices between the tiers filled with mud or clay chinking. The corners are secured with interlocking notches of three main kinds: the half-dovetail, the full dovetail, and the “V” notch. The “V” notch, pictured here on the Logan House, is by far the most common notch in the Whitewater (Stanton 1985: 129-30).

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

23 The second period of Ante-Bellum housing begins in the 1840s with a shift from the regional log style to one dominated by imported national fashions. By the time Indiana was being annexed and settled, the design principles associated with Neoclassical architecture were ascendant everywhere in the U.S. (Peat 1962: 9-80; Pierson, Jr. 1970; Maynard 2002). Chief among them were symmetry and balanced proportion, which were hard to achieve in log, but well suited to frame, brick, and stone, which became the new building materials of choice. During this second period, Whitewater families with enough money favoured a house two stories high, two rooms wide, and a single room deep, with or without a central stair passage and rear kitchen ell (Glassie 1968: 49; Kniffen 1986: 7-10). A smaller one-and-a-half story version, which sported distinctive half or “eyebrow” windows along the cornice line, was also popular (Glassie 1968: 129-31). The William Stoops family house, just west of Brookville (Figs. 10a and 10b), falls into the two-story category. William was born in Kentucky, and moved as a child with his family to Brookville in 1805. The house probably dates to the late 1850s or early 1860s (Reifel n.d.: 114).

Display large image of Figure 10a

Display large image of Figure 10a

German Immigration

24 To this parish landscape was added, after 1830, a steady influx of German immigrants. The newcomers were hardly a unified lot, for in their numbers were counted Catholic families from the German states of Bavaria, Hanover (Osnabruck), and Oldenburg, and the west-Rhine state of Alsace-Lorraine as well as Lutheran immigrants from Hesse-Darmstadt, Baden, and Prussia. They came first to Cincinnati, a principal destination for German immigrants (and itself becoming a largely German city), and then scattered through the region (Tolzmann 2005). In terms of the Whitewater, their movement was facilitated by several immigrant land speculators, including John Phalspol and John Ronnebaum, who bought up large tracts in Franklin County’s Ray and Butler Townships for resale to their countrymen (Taylor 1971: 37-42; Dinnerstein and Reimers 1977: 10-35; Stanton 1985: 48-100; Dreyer 1987).

25 It’s hard to go into any kind of research without harbouring some kind of expectations, and this one was no different. I must admit that we had hoped to find evidence of old-world building practices being imported into the Indiana hill country. Not only would this satisfy the folklorist in us (particularly the need to see tradition triumph over the forces of modernization), but it also could give the whole project an interpretive frame (becoming the story of immigrants resisting acculturation). However, the field data didn’t support these conclusions, although it did redirect the study in a new and perhaps more interesting direction. There are instances where German ideas prevailed, and these are noted in the following pages. More commonly, however, German settlement and architecture in the Whitewater Valley indicates adaptation rather than retention, with immigrants fitting rather seamlessly into the established parish/village landscape (Zelinksky 1973: 13-14; Taylor 1980).

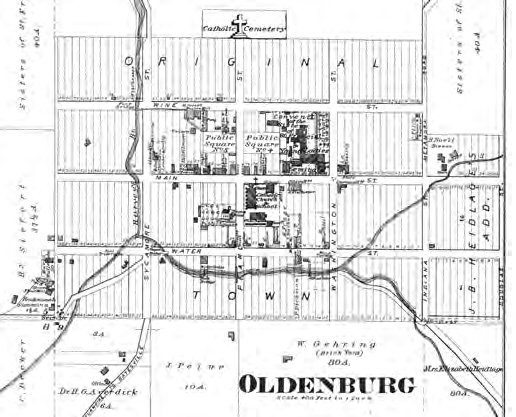

26 Of all the Whitewater towns, Oldenburg in Ray Township, platted in 1837, is probably the most German (Fig. 11). Here city planners eschewed the customary grid, using instead long narrow lots that imply an agricultural intent. Note that outside the town center, which has four public squares, each lot has potentially enough room for a house, barn, orchards, and gardens. Individual families could also have additional farmland outside the city limits, and the plan may have anticipated a European lifestyle taking root, with farmers traveling to their fields each day and returning to town in the evening, just as they did in the German villages left behind (Reifel n.d.: 163-71; Stanton 1985: 36-37).

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11

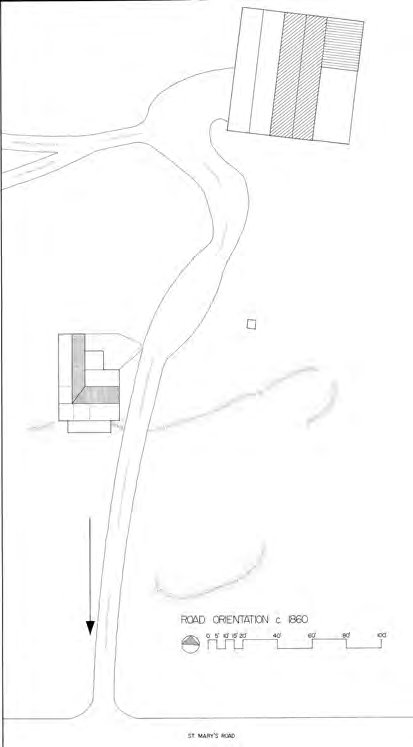

27 The prospect of owning land and all that it promised, however, tugged at the newcomers as fiercely as it did the Americans, and scattered family farms became the staple for German settlement (Fig. 12). There are some subtle old-world influences, particularly in farmstead layout. On Anglo farms, dwellings invariably faced outward toward the street, presenting a distinctive social façade (see Fig. 3 above). On a number of German farms, however, like the Schafstall’s on St. Mary’s Road in Butler Township (Fig.13), an old-world pattern persists where the house is “faceless,” oriented not to public space but rather inward in the direction of the barn and other outbuildings (Bergengren 1990 and 1994).

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13

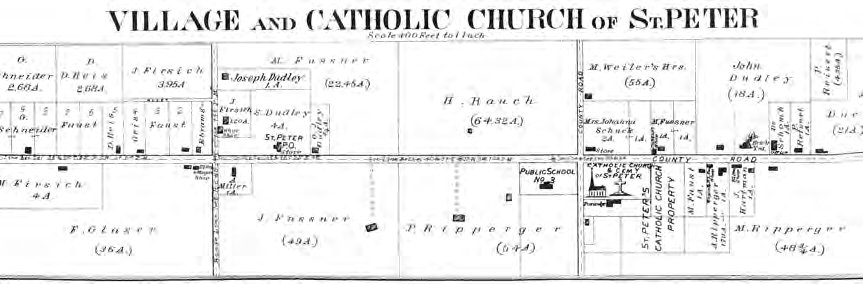

28 Dispersed farms may have been desirable to German families, but a sense of community apparently was too and this they found in parish-centered life. The Whitewater landscape is decidedly rural, but immigrant farms were never far from hamlets like St. Marys, Enochsburg, and St. Peter. The latter was first settled in the 1830s, but firmly established by the early 1840s and incorporated in 1853. St. Peter was unusual in that it stretched out to encompass not one but two crossroads (Fig.14). The one on the east, known to locals as “downtown,” had a school, general store, a cabinetmaker’s shop, a brickyard, a wagon maker/repair shop, a blacksmith shop, as well as the St. Peter’s Catholic Church. To the “Uptown” west stood a post office/store, blacksmith and wagon shop, dance hall, shoe store, and Zion’s Lutheran Church, which is not present on the map shown here (Cresswell 1995: 46-59, 79-108; Atlas of Franklin County Indiana [1882] 1976: 93; Reifel n.d. 134-35).

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14

29 In terms of ecclesiastical architecture, the great majority of German parish churches, whether Catholic or Protestant, copied American designs. The parish church at St. Peter is a good example (Fig. 15). It was constructed by subscription in 1852-53 and replaced a smaller log building that dated to 1844. The new church has a prominent steepled tower over an arched front door that opens onto a long aisle leading to a raised pulpit. The distinguishing features are Gothic, from the steep spire to the pointed-arched windows and window tracery (Cresswell 1995: 82-86).

30 The one exception to this assimilative trend may be The Church of the Holy Family in Oldenburg (Fig. 16). It was started in 1846 under the supervision of the Reverend Father Franz Rudolf, and is notable for its large, half-round compass windows and heavy medieval tower, topped by an onion-domed cupola with open Venetian-style ogee arched openings. These features suggest the influence of the Rundbogenstil, an architectural aesthetic popular throughout Germany at the time of emigration, and one grounded in the heavy round-arched Romanesque tradition, coupled with a rekindling of Renaissance (Venetian and Byzantine) decorative finishes (Atlas of Franklin County Indiana [1882] 1976: 106; Reifel n.d.: 472-73; Pierson Jr. 1986; Watkin and Mellinghoff 1987: 119-39;). Calling it German may be stretching things but compared to the other immigrant churches it seems quite foreign.

Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 16

31 German housing likewise adheres to the “from regional/log to national/Neoclassical” stylistic sequence found in established Anglo settlements. There are several houses, like the Kramer-Koester house in Dearborn County (Figs. 17a and 17b) that defy easy categorization and appear to reflect in their form and construction German influence. The house was built in the late 1830s or early 1840s and what immediately caught our attention was the way its roof extends out in an unbroken line over a long front porch, a feature rarely found in the Whitewater but which does surface in several other parts of the German-settled Midwest, Tennessee, and Texas (van Ravensway 1977: 113-74; Roberts 1986: 267-68; Coggeshall and Nast 1988:78; Gavin 2001; Hafertepe 2015) The two-room plan, with large central fireplace, isn’t unusual, but the house type itself, characterized by the porch (here with one side closed in to make a separate room) and distinctive roof profile, stands out. While not a house you would find in the literature on older German vernacular architecture, it does resemble the kind of smaller working-class cottages that were becoming increasingly popular in the middle years of the 19th century, as Neoclassicism thinking swept through that country. It may be a design, that is, that was related to something new the immigrants had lived in or seen before leaving for the United States (Gabler 1991; Gros 2011).

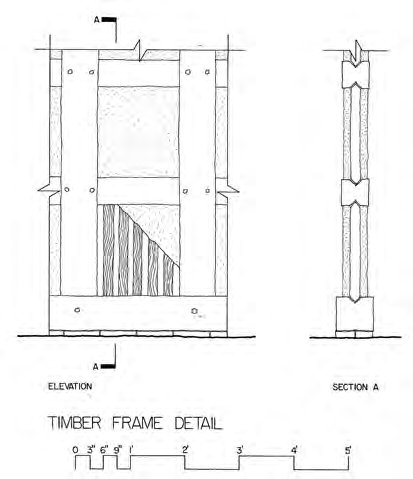

32 The most striking thing about the Kramer-Koester house is its fackwerk (infilled) timber-frame construction (Figs. 18a and 18b), a technology notable for its complexity and in the Whitewater, its rarity. German settlers, like the Americans, primarily relied on horizontal log construction, which they undoubtedly learned from their American neighbours. Fachwerk on the other hand, is decidedly German, and consists of a mortise and tenon timber frame, up braces on the gable ends, and in filled with mud-chinking (van Ravenswaay 1977: 145-77; Stanton 1985: 141-56; Tishler 1986; Gavin 2001; Hafertepe 2011: 114-16). Although we found this kind of timber framing being used for only a few complete houses, we also discovered that it was more commonly employed for additions to existing log houses, probably because it was easier to attach a frame extension to a log crib than join new logs to it (Stanton 1985: 148).

33 Most immigrant houses that we surveyed, however, fit nicely into the stylistic sequence shown in American housing. In the 1830s and 1840s German settlers built log houses resembling those found around them. Houses were rectilinear blocks with either one or two downstairs rooms, half-story chambers above, and off-center front doors. Many started out as a single-chambered room, and either remained that way or received a second chambered room through addition. The one Henrich (Henry) Ronnebaum built on St. Mary’s Road, in Butler Township (Fig. 19), is indicative of this pattern. Franklin County records show that Henry was born in Oldenburg, Germany in 1814. He left through the Port of Bremen in 1832, landing first in Baltimore, and then proceeding on to Cincinnati before arriving in Franklin County in 1837. He gained title to the land this house sits on in 1853, but the house could have been built earlier, soon after his arrival in the valley.

Display large image of Figure 19

Display large image of Figure 19

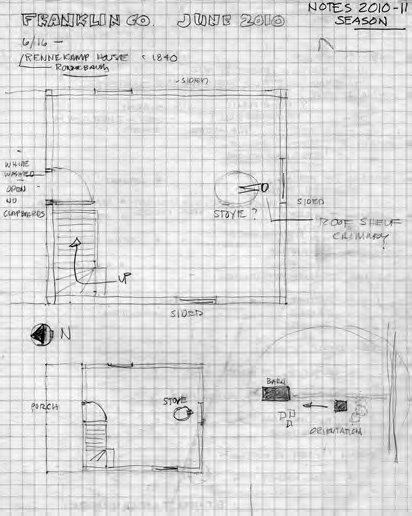

34 Our field sheet, reproduced here (Fig. 20), shows the Ronnebaum house plan as it was originally constructed with a single room, a corner staircase leading to the upper chamber, a stove chimney, and a single door that opened not to St. Mary’s Road but rather to the rear of the lot, toward the barn. The logs were covered on three sides with clapboards. The north wall, with the door, was whitewashed and may have been covered by a porch.

Display large image of Figure 20

Display large image of Figure 20

35 The “V” notched log work on the house is consistent with what we found on the majority of Whitewater log houses (Fig. 21; compare to Fig. 10 above). Again, although building with logs is found in some parts of Germany, the immigrants landing in Indiana came from regions, most notably Hanover, Baden, and Alsace, where timber framing and not log was customary, so these buildings are yet another indication of how the Germans adapted to lifeways in the United States.

Display large image of Figure 21

Display large image of Figure 21

36 The most common German log houses had two ground floor rooms, half- or full-story upstairs chambers, and either fireplace or stove chimneys (stoves were preferred). In nearly all cases, the logs were covered at the time of initial construction with clapboard siding. Rear service rooms, either in a gabled-ell or a shed-roofed lean-to, are typical as well. Representative of this group is the Heudepohl-Grunkemeyer house on St. Mary’s road (Figs. 22a and 22b). It was built for John F. and Mary (Maria) Heudepohl who hailed from Hanover, Germany. John was naturalized in the late 1840s, in Franklin County, and the house may date to that time. The Heudepohls sold the property to Andrew Grunkemeyer in 1885 and it remained in that family until the late 1950s.

Display large image of Figure 22a

Display large image of Figure 22a

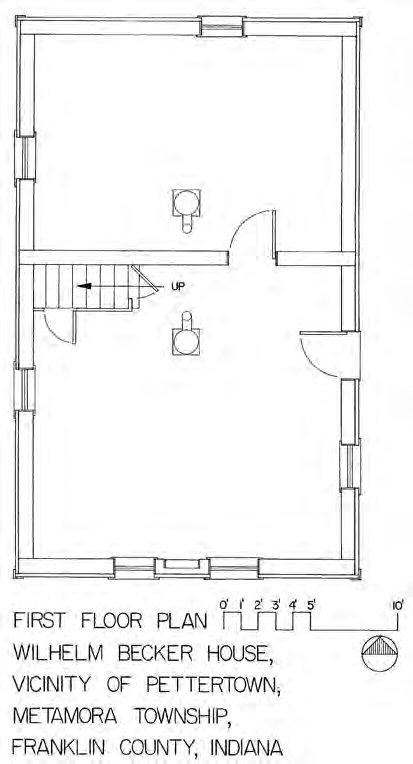

37 Contrasting with the Heudepohl house, which has the appropriate Anglo social façade, are a number of German-built houses that lack such a formal public statement. One, the Henry Ronnebaum house, we have already mentioned. Another is the Herman-Becker house built on Stacy Roof (Figs. 23a and 23b) in Metamora Township. This house is the two-room with chambered upstairs type, but here it faces away from the road (probably toward the barn and farmyard which had been torn down by the time of our visit). The history of this house is uncertain, but it appears to have been built in the 1850s for the family of Conrad Herman, who later sold it to the William Beckers.

Display large image of Figure 23a

Display large image of Figure 23a

Display large image of Figure 23b

Display large image of Figure 23b

38 Given the constraints found in building with log, and the fact that many German houses achieved the most desirable two-room size only through addition, it is not surprising that great variation occurs. This diagram (Fig. 24) shows a range of Whitewater Valley German log houses, with the overall effect being one of an organic, additive design process. It’s easy to see how the houses grew from one to two-rooms, and window and door placement, while aspiring to symmetry, cannot quite attain it given the exigencies imposed by log crib (module) construction. Every family apparently felt free to find the best, most expedient solution to their fashion.

Display large image of Figure 24

Display large image of Figure 24

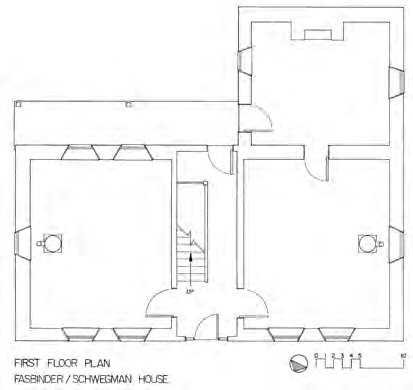

39 By the 1850s and 1860s, German families, like their American neighbours, began experimenting with the newer, more fashionable, house designs associated with the Neoclassical style. As we have seen, the house conveying the most status was the full two-story type, either of fired brick or stone, like the one built for the Fasbinder family on Clear Fork Creek in Butler Township (Figs. 25a and 25b). The William Fasbinders emigrated from Germany in 1848 and by 1850 were living on this farm in Franklin County. The large stone house was probably built by William’s son August, who married Magdelena Stock in 1856 and completed the new house by 1860.

Display large image of Figure 25a

Display large image of Figure 25a

Display large image of Figure 25b

Display large image of Figure 25b

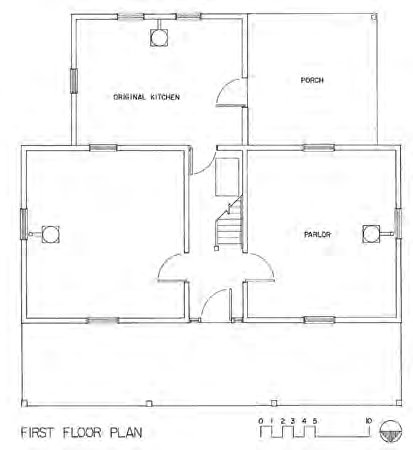

40 Accompanying the surge in new construction, Second Period German domestic architecture also included a good number of remodelings. Now, however, instead of simply adding a second room and letting the log walls dictate the exterior appearance, families worked toward a more proportional Neoclassical outcome. What happened to the Henry Ronnebaum family house (see Figs. 20-22 above) is instructive. First a decision was made to reorient the house according to Anglo practice so that it faced forward toward St. Mary’s Road (Figs. 26a and 26b). Then a second room was added in a way that made the house, resemble (as much as possible) the two-story Neoclassical house (Fig. 27). As in many additions, timber-frame fackwerk was used for the new section, which made the extension easier because the framing could simply be butted up against the original log house.

Display large image of Figure 26a

Display large image of Figure 26a

Display large image of Figure 26b

Display large image of Figure 26b

Display large image of Figure 27

Display large image of Figure 27

41 Another Anglo house form adopted by German immigrants was one folklorist Henry Glassie has called the Classic Cottage. These houses are recognized by their one-and-a-half story height and the presence of small “eyebrow” windows placed just under the front eaves. Often this type of house is found with a central-stair passage, as is the case with the Frederick Glaser family house that stands on Blue Creek Road in St. Peters (Figs. 27a and 27b). Michael Ripperger appears to have been the one who purchased the land from the United States Government in 1837, but by the 1860s when this house was probably built, it was owned by the Glasers. According to his obituary, Frederick was born in Bavaria in 1817 and emigrated to America with his parents around 1824. They may have come first to Cincinnati, but by the 1840s were living in St. Peters. Frederick was the town blacksmith, an occupation he pursued until his death in 1893. One history holds that the people of this small community were so pleased to have a blacksmith in town that they built Frederick a log shop to use for his business.

42 Fieldwork suggests that the Classic Cottage form caught on particularly well with Whitewater Germans, though many examples preserve an older two-room plan hidden behind a regular Neoclassical facade. Two such houses are notable for the way their builders reconciled exterior appearance with interior function. If the choice is for the house to have two equal sized rooms, then the most coveted kind of Neoclassical symmetry, where the front door is centered with one or two windows to either side, cannot happen. The problem is that the internal partition (whether log or frame) gets in the way, preventing the front door from being placed in the middle (as in the Glaser house, Figs. 28a and 28b).

Display large image of Figure 28a

Display large image of Figure 28a

Display large image of Figure 28b

Display large image of Figure 28b

43 On the first example (Fig. 29), the Haas House, which is located at the corner of St. Peters Road and State Road 1, in the South Gate community, the central chimney is substituted for the front door as the dividing point in the design, and then doors are placed to both sides in a window/ door/door/window opening pattern to achieve the balance prescribed in Neoclassical thinking. When originally constructed around 1850, the house consisted of just the two front rooms that were log, while the later rear rooms were frame that was in-filled with fired brick.

Display large image of Figure 29

Display large image of Figure 29

44 Similarly, in the Laker-Meyer House (Fig. 30), we see a balanced symmetrical façade, but the four-bay door/window/window/door arrangement reveals the presence of the two-room interior. This house, which stands on St. Mary’s Road, has timber-frame fackwerk walls, and dates to the early 1850s. It was built for Henry and Maria Laker. Henry was born in Oldenburg, Germany in 1827. He left from Bremerhaven and arrived in the United States in 1847, coming through New Orleans to Cincinnati, where he married Maria Backhaus in 1851. The couple then moved into the Whitewater River Valley and built this house soon after purchasing the land in 1853.

An American Landscape

45 Studies like this are important not only because they represent rare fieldwork-based investigations of the 19th-century midwestern vernacular architecture, but also because they offer unique artifact-driven perspectives on the history of the region and its people. For us, it seems that we barely scratched the surface of what remains a vast but largely unstudied landscape. But several things stand out. One is how quickly German immigrants bought into the ways of their new homeland (which is not surprising given that they came to start new lives in a new country), and the other involves the creation of small-town ecumenical America, a topic that warrants considerably more attention than we give it here. Folklorists might not be enamoured by the thought of studying the coming of mainstream popular culture, which seems antithetical to the romantic callings of our discipline (my generation of folklorists, after all, were naturally drawn to expressions of cultural resistance). But the traditional architecture of the Whitewater River Valley, and other Midwestern regions like it, is a built landscape that is rapidly disappearing, and one that in a small way we honour here with these photos and drawings.

Display large image of Figure 31

Display large image of Figure 31

Notes

Thanks to Gray Stanton for making this project possible and hanging in with me for so many years. It wasn’t easy, I know. Jerry Pocius and Meghann Jack helped with the fieldwork, read earlier versions, and their suggestions helped greatly. Julie Schlesselman, Manager of the Local History and Genealogy Department at the Franklin County Public Library in Brookville, also read through a draft, checking for factual errors, and generously provided historical and biographical information on many of the individual houses included here. Thanks to Julie and her staff for making this report a much better product.