Article

The Crab House on Oyster Creek:

Folkloristic Response to Vernacular Landscape and its Environmental Moorings

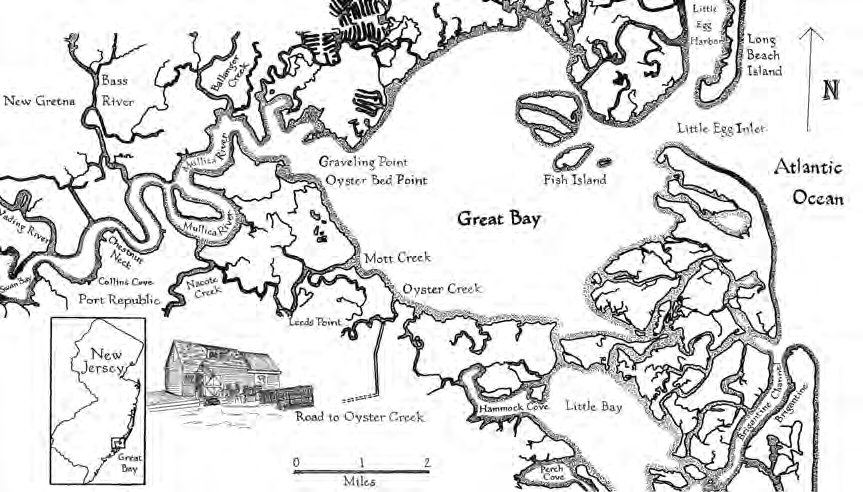

Résumé

La Maison du crabe Andersen, sur Oyster Creek (le « ruisseau aux Huîtres ») est située sur une voie d’eau faisant partie du large environnement estuarien qui s’étend de Great Bay à la rivière Mullica, au New Jersey. Ce type de bâtiment a longtemps servi aux pêcheurs d’huîtres, de palourdes, de crabes, de poisson et aux chasseurs de gibier d’eau sur les rives de l’océan Atlantique et de la baie Delaware. Cette maison, vieille de près de quatre-vingt-dix ans, est idéalement située pour que Phil Andersen puisse chercher des crabes dans les marais adjacents et préparer ses prises pour le marché. Ce bâtiment, de pair avec son bateau et son attirail de pêche, organise les contours de son paysage de travail ; ces outils ne définissent pas seulement l’adaptation de ce métier à l’environnement mais, en tant qu’assemblage, font continuellement progresser l’acquisition par Andersen d’un savoir écologique traditionnel. Bien que sa présence austère dans les marais salants signale son adaptation environnementale et son rôle d’aiguille de la boussole occupationnelle d’Andersen, le fait que sa fonction de paysage de travail perdure résonne fortement à travers la communauté. Le travail et la vie sociale qui se déroulent dans ce bâtiment évoquent sa capacité de s’attirer de nombreux affiliés, ses caractéristiques, son usage et sa situation ayant tous une qualité de profondeur esthétique et performative qui en font une pierre angulaire de l’expérience de l’environnement et du sens du lieu. Ces attributs – et en particulier leur rôle dans l’apaisement de la mémoire et l’affirmation des ancrages environnementaux de la communauté – montrent comment la maison du crabe Andersen, et les autres bâtiments similaires qui l’ont précédée, ont provoqué une réaction de folklorisation pendant plus de cent cinquante ans.

Abstract

The Andersen crab house on Oyster Creek is located on a waterway that is part of the wider estuarine environment consisting of New Jersey’s Great Bay and the Mullica River. It is a building type that has long served oystermen, clammers, crabbers, finfishers, and waterfowlers along New Jersey’s Atlantic Ocean and Delaware Bay coastlines. Having survived for almost ninety years, the building’s siting allows Phil Andersen to effectively tend the adjacent crabbing grounds and prepare the catch for market. The building, along with his boat and harvesting gear organizes the contours of his working landscape, tools that do not simply define the occupation’s environmental fit, but, as an assemblage, continually advance Andersen’s acquisition of traditional ecological knowledge. While its stark presence on the salt marsh punctuates its environmental fit and role as the axis of Andersen’s occupational map, its enduring function as a working landscape resonates widely throughout the community. The work and social life of the building speak to its capacity to be broadly affiliative, its features, use, and siting laden with aesthetic and performative depth that make it a touchstone of environmental experience and sense of place. These attributes—specifically their role in curating memory and affirming a community’s environmental moorings—show how the Andersen crab house, and similar buildings that preceded it, have engendered folkloristic response for over one hundred and fifty years.

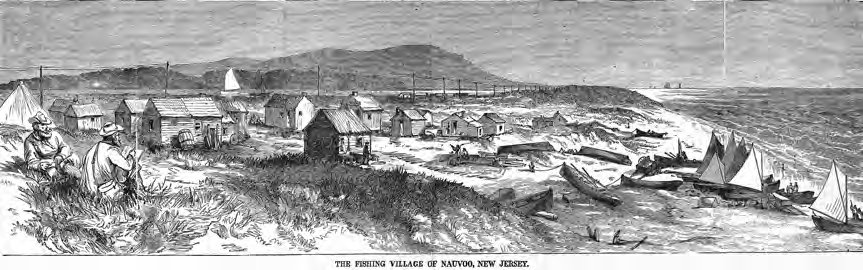

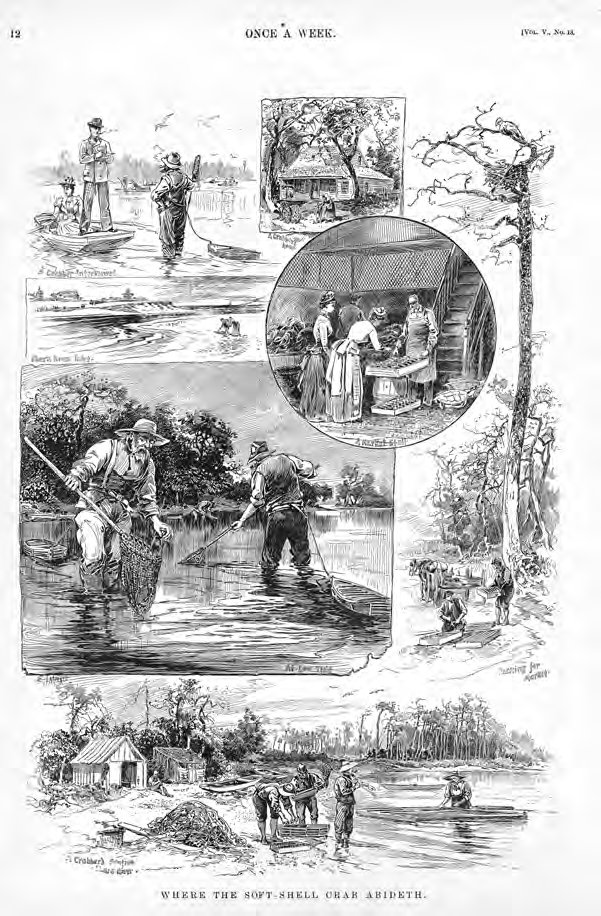

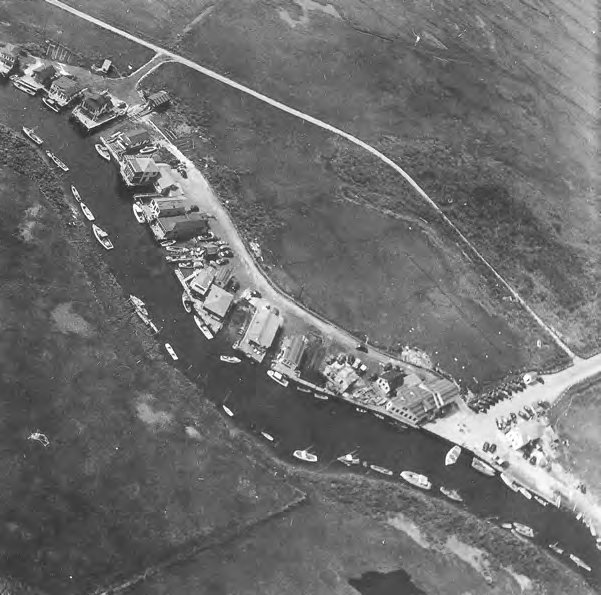

1 When, in the 1930s, Henry Charlton Beck—often viewed as New Jersey’s first folklorist—made his way out to Leeds Point along Southern New Jersey’s Atlantic Coast, then to its terminus at Oyster Creek and the expanses of Great Bay, he used the vernacular landscape to retrieve what he perceived as the area’s “forgotten” history. Taking his cues from extant and ruined building stock, and from stories about them as told by informants he met along the way, he challenged historians “to find…what went on, years ago, in a variety of scattered places, in the words of those we have met to talk to.” Beck was “in search of coherent folk lore,” and, anticipating the field’s growing priorities, took measure of the vernacular landscape and the words of his informant, Jesse Mathis, to better understand how past and present livelihoods relied on “‘the sea and salt tang of the air’” for their sustenance. Drawn by words and place, Beck proceeded from the area’s piney woods to Great Bay’s marshy littoral and a telling encounter with its vernacular landscape. It was dotted with small buildings used by baymen who clammed, oystered, crabbed, fin fished, hunted, and trapped, and, to a lesser degree, by some who simply wanted to dwell by the bay during their leisure hours. Beck’s arrival made him party to a historically charged, folkloristically inspired encounter with this vernacular landscape and its estuarine siting. But, somewhat unbeknownst to him, he was not the first, nor would he be the last, to be affected by this experience (Beck 1937: 7-8, 118-20).

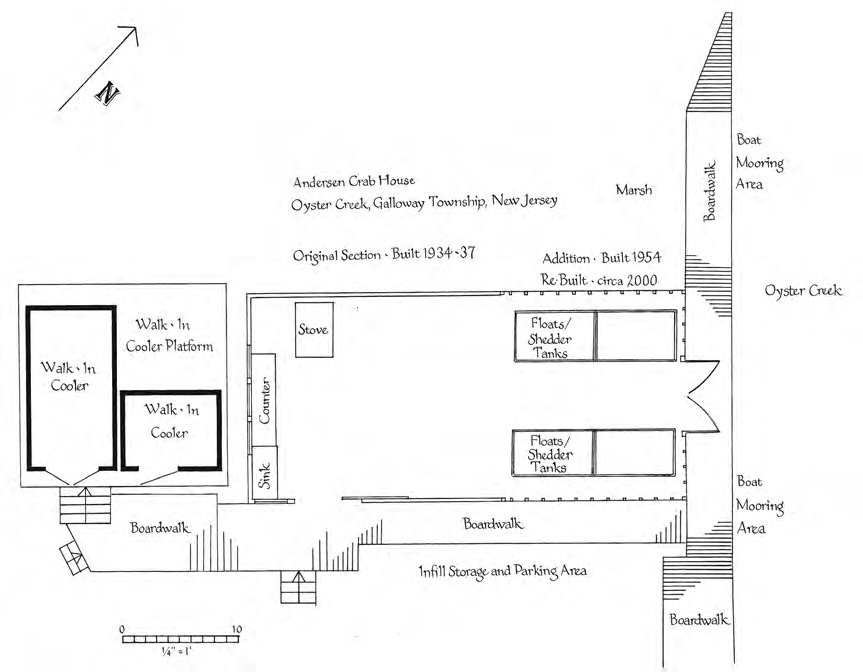

2 Describing his quest for “coherent folk lore” and reflecting further on his task, Beck was actually revealing his desire to present the mythic layering of the vernacular landscape—the meaningful history that was at work in the richly textured experience of local life (Beck 1937: 8). Today, this location—which captured Beck’s imagination and his hope to use folklife to expand historical narrative—is the site of the only active crab house on Oyster Creek—the place from where Phil Andersen continues to work the crabbing and waterfowling grounds of Great Bay (Figs. 1, 2). Andersen’s enduring use of his crab house and the collective affirmation it engenders from those who work and socialize there, who visit periodically, or who simply encounter it by chance after a long foray to the end of Leeds Point, make it a place of practicalities, but also a place where folk history’s mythic veil is still in play. Overtones of Beck’s sentiment continue to wash over the starkly perched crab house on Oyster Creek, as does a longer tradition of canonizing the marine environment’s working landscapes as icons of regional identity. Our encounter with this site gives way to the folklorist’s urge to reckon, to begin unravelling an environmentally sublime setting whose mythic pull, in the words of Henry Glassie, culturally nourishes past and present “through the daily rhythms of work and play of its moment, softly coaxing people while they construct their realities” (Glassie 1988 [1977]: 72).

Display large image of Figure 1

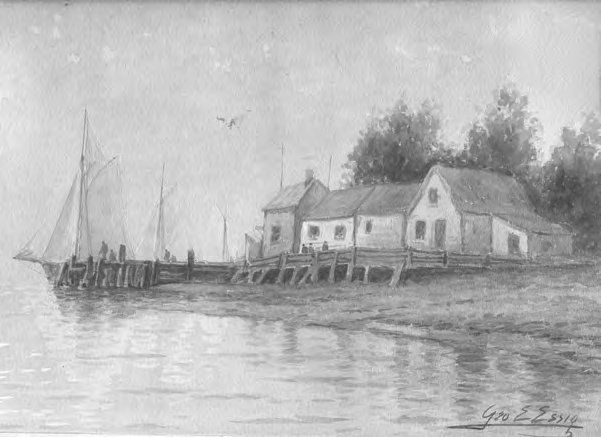

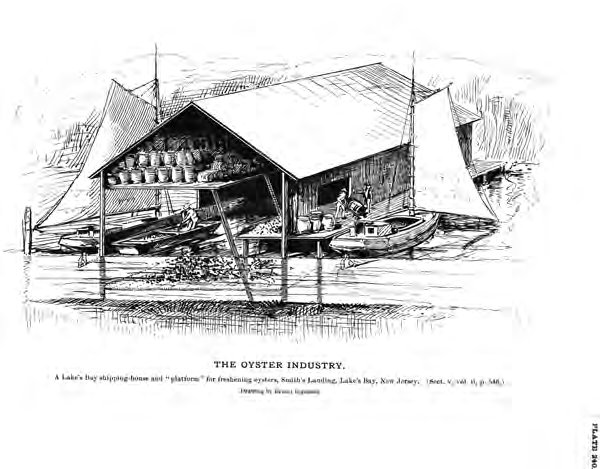

Display large image of Figure 1

3 Located slightly north of Atlantic City, New Jersey sits Great Bay, one of the state’s largest estuarine environments, a body of water serving as the terminus of the Mullica River and a gateway to the Atlantic Ocean. Rimming Great Bay are vast expanses of salt marshes that are cut through by numerous creeks and sluices. These waterways traditionally serve as points of entry for baymen who harvest Great Bay’s marine resources, places containing modest arrangements of fish, crab, or clam houses, docks and wharves, and moored boats. Approaching these settings by land or water when they are framed by the verdant sedge grasses of summer or their golden-brown hues of winter, is to begin grasping the juncture they occupy in maintaining the collective reach of those who work the water. Such cultural landscapes embody the toil and sensory response inherent in architectural thresholds where land and water meet. Honing human experience in biologically rich, tenuously controlled marine environments, these buildings have enticed the folkloristic sensibility of observers for well over a century and a half.

4 Near Great Bay, in December of 1876, Walt Whitman crossed the bayman’s threshold domain when his train “enter’d a broad region of salt grass meadows, intersected by lagoons, and cut up everywhere by watery runs. The sedgy perfume, delightful to my nostrils ... I could have journeyed contentedly till night through these flat and odorous sea prairies.” Moved, but not deluded, by the salt marsh’s intoxicating sulpheric scent, Whitman’s ambient response laid bare the bayman’s ecologically poetic working landscape, but did not shy away from the primal forces confronted by the occupation’s place-making in the liminal realm. As later versions of Leaves of Grass would reveal, he had “the wish to write a piece, perhaps a poem, about the sea-shore—that suggesting, dividing line, contact, junction, the solid marrying the liquid” where his own existential quest could find affiliation—indeed repose—in the biologically and physically dynamic context of the bayman’s working landscape (Whitman 1907: 88). If needing recent translation, it is the Whitmanesque statement by John Stilgoe that the bayman’s buildings and boats make “what happens in the marginal zone ... exactly that which is important, intrinsic, essential, that which illuminates not only larger issues of landscape, of environmental presentiments, but whole components of American culture” (Stilgoe 1994: 10). Quite simply, it is recognition of cultural landscape’s effort to animate and harmonize an ecosystem, what the American poet characterized as a “blending of the real and ideal,” a response to an enduring “liquid, mystic theme” (Whitman 1907: 88-89).

5 When Walt Whitman extolled the virtues of the “boatman and the clamdigger” in Leaves of Grass, it was one of his many visceral responses to American occupational folklife and its tether to both the country’s natural resources and to the locally constructed settings where it gained meaningful expression. After time spent with the aforementioned baymen, he informed readers of their fuller vernacular landscape where, after harvesting clams, the work setting’s social and environmental priorities converged: “You should have been with us that day round the chowder-kettle” (Whitman 1992: 35). Indeed, in his ecopoetics, Whitman was seemingly throwing an ethnographic lifeline to folkloristically inspired observers who would henceforth have to reckon with fishing places as both tool and expression of deep, intimate local living and the “unfailing perception of beauty” emerging from it (Whitman, Leaves of Grass [1855] qtd. in Killingsworth 2004: 95). From his native Long Island to the shorelines of Southern New Jersey, Whitman looked to evoke the multiple essences—some historical, some emergent—of dwelling and working in the littoral zone. He imbued them with what can be described, in the words of Edwin Dobb, as an “erotics of place,” the lure of places “we believe we need—to survive, flourish, multiply, elaborate” and have “invited and aroused extraordinary passions.” From this perspective, it warrants comparing the attention garnered by the bayman’s work environment to Dobb’s views of his native Butte, Montana and the expectations of its mining landscape—“ through the lens of human desire” (Dobb 2010: 2-3). Setting this up in verse, Whitman proclaimed:

To hear the birds sing once more,

To ramble about the house and barn and over the fields

once more,

And through the orchard and along the old lanes once more.

along the coast,

To continue and be employ’d there all my life,

The briny and damp smell, the shore, the salt weeds exposed at low water,

The work of fishermen, the work of the eel-fisher and clam-fisher;

I come with my clam rake and spade, I come with my eel-spear

Is the tide out? I join the group of clam-diggers on the flats,

I laugh and work with them, I joke at my work like a mettlesome young man.

6 This sentiment drove Whitman to see a transcendent convergence between local culture and local environments, and his sensory response to his beloved estuarine ecology only heightened the affective depth of his shared experience.

7 Whitman’s musings correlate with folkloristic sentiment that rippled widely throughout America well into the 20th century. Folklorist Regina Bendix calls this pattern “the aesthetic of the common man”—the notion that vernacular landscape embodied authentic American experience borne of its users’ interactions with the country’s natural endowments (Bendix 1997: 72-73). This strain of American romanticism gradually consumed the energy of observers interested in clarifying the traditions and environmental fit of a fishing community’s working landscape, a movement whose folkloristic resiliency could be measured by diverse chroniclers ranging from writers and painters to photographers and government reporters. Visual and written narratives of these sites began gracing the pages of Harper’s (Weekly and Monthly) and Scribner’s with ever greater frequency starting in the 1870s, and by the turn of the 20th century were fully ensconced in America’s most popular printed media (Figs. 3 and 4).

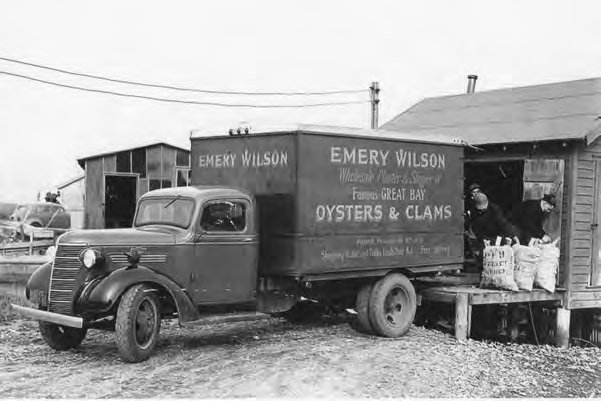

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

8 The U.S. Fish Commission seized on similar presentational strategies of these sites to provide ethnographic bearings for advancing progressive management and scientific advice for the nation’s fisheries (Pauly 2000: 44-70). Painters who attended increasingly popular art colonies along the Atlantic coastline between New Jersey and Maine—such as the Rocky Neck Art Colony in Gloucester, Massachusetts and the Cos Cob Art Colony in Greenwich, Connecticut—found the vernacular architecture of nearby fishing communities to be ideal subject matter for expressing regional identity in coping with the tensions of rapid industrial transformation. Near Great Bay and the confines of Oyster Creek, a number of painters emphasized Impressionist technique to echo the nobility Whitman saw in the Jersey bayman’s working landscape (Larkin 2001: 86-87; Curtis 2008; Pedersen 2013). As American visual artists became more entrenched in the country’s cultural politics and the pull of regional romanticism, their work did not shy from incorporating the variety of human activities that occurred at working waterfronts. Less inclined to solely depict buildings, their scenes were now contextually alive with people talking, preparing food for market, building and repairing boats, and engaging in leisure activities—occupational pursuits that were becoming notable genres of the emerging folklore studies movement. Although not as committed to including people in his work, well-known artist Arthur Wesley Dow was gripped by emergent folkoristic sentiment and its response to vernacular architecture. Deeply attached to the settings of his native Ipswich, Massachusetts, he was among a cohort whose varied visual media canonized clam shanties and assorted fishing buildings in an effort to portray authentic American regional culture. Harmonizing work and nature in his depictions of clam shanties, Dow sought to “dignify” their placement amidst the “beautiful distances” of the salt marsh, and, in his efforts to advance early historic preservation policy in Ipswich, used his work to underscore the necessity of conserving traditional working landscapes (Fairbrother 2007: 32-33, 37, 41-42).

9 These sentiments gave way to the intellectual and political ambitions of the American regionalist movement of the 1920s and 1930s which viewed the country’s folk cultures as critical touchstones of a newly constituted national identity. Vernacular landscape figured prominently in this movement, its resiliency and adaptability befitting what B.A. Botkin saw as the emergent quality of folk expression. Not surprising, this outlook found favour with some of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s most notable New Deal Programs. For Botkin, along with other participants in the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA) Federal Writers Project, their work brought sharp focus to the aesthetics and use of vernacular landscapes, seeing them as folk expressions arising from “intimacy with specific environments” (Dorman 1993: 83, 89-92, 95-97, 103-104, 113-14, 119-22, 141-42, 148-54). This documentary spirit brought greater qualitative scrutiny to the previously picturesque evaluations of fishing architecture, and framed a building’s compelling aesthetics alongside its economic function and social necessity, as well as its role in fostering traditional ecological knowledge—insights gained through years of working the water. Although in its formative stages, this documentary template was revealed in WPA writer Josef Berger’s Cape Cod Pilot when he remarked:

10 The cultural temperament that drove this regional longing, and shaped the complex desires behind its “mythic valence” (Glassie 1988 [1977]: 72) descended on the working landscapes of clammers, crabbers, finfishers, and waterfowlers along Great Bay and its tributaries, as well as on similar sites throughout Southern New Jersey. The watercolourist, George Emerick Essig (1838-1923), made the bay-man’s working landscape in Southern New Jersey a staple of his work, also rendering these scenes as etchings, and to a lesser extent, as oil paintings (Figs. 5 and 6). Having exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and influenced by James Hamilton and Edward Moran, he moved to Atlantic City in the 1890s (nearly adjacent to Great Bay and its tributaries) and his artistic focus became even more fixed on maritime landscapes and their natural environments (Grzesiak 1993: 8-17). Juxtaposed against the backdrop of Atlantic City—America’s most metropolitan seaside resort of the era—images of bayman tonging for oysters or raking clams made for poignant depictions of tradition bearers labouring under the tourist gaze of the Philadelphia/New York City urban corridor. Similar visibility prompted the U.S. Fish Commission to document buildings used to facilitate the transplanting and cleansing of oysters in the Great Bay vicinity (Fig. 7). At the same time, as the area’s land became more desirable for real estate development, images of the bayman’s working landscape were used to market the appeal of living in a marine locale (Fig. 8).

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

11 Early 20th-century photographers of Southern New Jersey’s marine landscapes— whether depicting fishing, clamming, crabbing, oystering, trapping or hunting—enhanced public understanding of how the vernacular architecture of each activity functioned and broadened occupational folklife’s role in fuelling the region’s environmental imagination. Working as a journalist and photographer, Cora Sheppard Lupton’s exhaustive catalogue of Southern New Jersey’s Delaware Bay shad, sturgeon, and oyster fishing architecture produced an unmatched visual narrative that ushered viewers through every step of moving marine products from their waterborne environment to market. Having garnered a regional and national reputation as a writer on fisheries, agriculture, and a host of other natural resource use issues—as well as being a noted commentator on emerging environmentalism—her visual narratives of the region’s fishing architecture corresponded with the depth of her journalistic work. Viewed accordingly, her depictions of vernacular architecture revealed a significant reckoning between folklife and a rising tide of ecological consciousness. When she chronicled the long tenure of shad fisherman William “Catfish Billy” Whitsel, who “lived in a little shanty erected upon an army pontoon,” she elaborated on its placement amidst the “thriving village of cabins, built on scows and piling” around Bayside, New Jersey “where fishermen ... hasten to get their boats and nets in working order” (Sheppard 1903) (Fig. 9). To emphasize the “thriving” pulse of this working landscape, Lupton’s portraits keenly underscored the fishery’s reach throughout the community—a place where the collective affiliation of men, women, and children found expression at the local boardinghouse or in a space on the salt marsh where gill nets were maintained (Figs. 10 and 11). Ethnographically rich, her series of images conveyed the environmental fit of these built environments and the manner in which they animated the amphibious interface of land and water settings; in short, she participated in a documentary tradition that clarified fishery architecture as a compass of each of its occupant’s attenuated marine domains.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11

12 The reach of such visual expression deepened when photographer Harvey Porch—a contemporary of Cora Sheppard Lupton—began his documentary work on New Jersey’s Delaware Bay oyster fishery. While most of Porch’s photography of oystering architecture was intended to serve distinctly promotional goals for the area’s industry, it was also, in the emerging era of Progressive governance in the United States, visually deployed to show that tradition and regional identity would hold their place amidst the state’s regulatory oversight and scientific investigations of the fishery (Figs. 12 and 13). His photography of oystering architecture graced the pages of New Jersey Bureau of Shell Fisheries Reports, New Jersey State Industrial Reports, New Jersey Board of Health Reports, and state-mandated textbooks for elementary and secondary school students. Aspirational in nature, Porch’s depictions of vernacular architecture in these outlets tangibly reinforced societal expectations that a resource—oysters—held as common property by the state’s citizens and harvested by one of its most iconic folk communities, could serve the greater public good through coordination of occupational tradition and centralized government. Such photographic portrayal found itself awash in America’s diverse exercise of folkloristic sentiment, not reducible to one objective, but often caught in a mix of nostalgia, commercial promotion, and regional boosterism. But these visual strategies also showed murmurings of the emergent American regionalist movement and its desire to draw inspiration from the aestheticized dimensions of folk culture—the expressive power of its practice. Vernacular landscape’s organic sensibility was central to these aims and fit broad progressive plans to advance the socially and environmentally integrative benefits of America’s folk communities (Chiarappa 2019; Dorman 1993: 103-104, 119-22, 135-36).

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 12

Display large image of Figure 13

Display large image of Figure 13

13 Journalistic accounts and government reporting—in both written and photographic outlets—on what became recognized as the quintessential New Jersey bayman’s shelter, along with the structure’s wider pictorial dissemination on real photographic postcards, contributed to making it a widely recognized motif of regional affiliation. Endowed with a degree of typological flexibility, the minimalist appearance of these structures and their wider working landscape steadily gave way to intrigue over their standing as a bellwether of the region’s mythic values. Regional writers probed this condition, seeing the environmental and social synthesis of these vernacular landscapes as an enduring, and at times fading, marker of authentic American experience. In his 1931 portrayal of Barnegat Bay, A. P. Richardson used its “waters and shores ... to tell of the folk who dwell about the bay, who sail and fish upon it.” For him, an inspiring, yet threatened authenticity was passing and soon there would be “no more bayman and marsh-men, no more women with red blood in their cheeks.” A focal point of Richardson’s observation was the “hut” of Hector Barton, a place he scrupulously described but was at great pains to typologically cast. He contemplated: “what is [it] that stands yonder on the meadows, small and square and black,” but whose “six feet by ten feet” dimensions served as “the hailing port” from where Barton did “ ‘ a leetle fishin’, shootin’, or trappin’” (Richardson 1931: v, 122-30).

14 Not far from Great Bay and the working venues that dotted its creeks and sluices, Cornelius Weygandt—a Professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania and an unabashed romantic who characterized himself as “one who holds with the Old Ways”—lamented encroachments on the bayman’s estuarine world by vacationers who created “bungalowdom” on his working landscape (Figs. 14 and 15). While walking toward a sea island shack with a bayman who was selling his dunescape to vacationers, he described his guide as wracked with ambivalence and “feeling ... down deep ... that he was betraying his native heath to the hosts of outlanders ... who had turned the beauty, so grey and lonely, of his beach hills into flat and featureless suburban nothingness” (Weygandt 1940: 333-36). As Weygandt roamed Southern New Jersey, he incorporated folklore’s artifactual and oral genres into his assessments of the region’s distinctive sense of place, and, recognizing this expressive mix, accounted for its usefulness in understanding the working landscape’s environmental fit.

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 14

Display large image of Figure 15

Display large image of Figure 15

15 But if a certain artifactual and verbal ecology animated the bayman’s built environment, Weygandt was not alone in seeing it. When Joel Barber—an architect who was largely responsible for canonizing waterfowl decoys as American folk art—did his fieldwork in the 1920s and 1930s, he drew his conclusions based on countless visits to shacks used by baymen along New Jersey’s coastline between Barnegat Bay and Great Bay, as well as those in locations spanning the entire east coast of the United States. One commentator praised him for his ability “to lounge up to a shoresman and drop into easy conversation with him, how to win his confidence with knowing, sympathetic talk of boats and tides and birds…a tribute to his understanding of shore folk and decoys” (Add Americana: The Decoy, 1932: 38). Barber’s exploration of waterfowl decoys sharpened his view of their contribution to the bayman’s wider material world, and, in the process, led him to celebrate the shanty’s role in it. So moved, he penned a collection of verse that opened and closed with poems respectively titled “Shanty Preface” and “Shanty Poetry,” and, to underscore the volume’s response to cultural landscape and estuarine ecology, sported an illustration of a classic bayman’s shanty on the frontispiece. The collection, labelled ‘Long Shore and published in 1939, thoughtfully evoked the bayman’s estuarine experience and sought to viscerally convey the shanty’s role in organizing it (Barber 1939: 1-2, 108; 1954 [1934]).

16 Not unlike others who wrote on Southern New Jersey’s maritime folk cultures, Henry Charlton Beck typically employed a processional narrative, a rhetorical strategy where he took readers on a journey to discover the mythic quality of the region’s vernacular landscapes and the people who animated them. Beck’s earliest writing embraced this approach, putting readers alongside informants who used buildings and landscapes as archives of their community’s collective memory. But, in Jersey Genesis, as the title implies, Beck’s ethnographic ambition took a decidedly incisive turn toward the mythic. Specifically, he desired to portray the working landscapes at the juncture of the Mullica River and Great Bay as living legacies, places where a usable past deeply informed those who utilized the marine resources of this lush estuarine environment (Beck 1945).

17 Beck keyed on signature buildings and artifacts that were gateways to understanding the folkloristic relevance of this marine setting— places where work never veered from affirming the collective obligations of those who lives were shaped by the river and bay. Central to this endeavour, Beck reprised his earlier encounter with Jesse Mathis, seeing in these previous travels the need for “authentic talking” if one was to decipher the enduring historical relevance of placemaking at Oyster Creek. He coupled these folkloristic leanings to descriptions of Charles Leek’s boatyard as the setting of an artisan who “lets his boats speak for themselves” and after they were “ ‘lanched’ ... continued to follow them as if they were members of his family.” More frequently, he extolled hard-bitten work experience, whether it was the sight of Charlie Weber (in Beck’s words, a “surviving anachronism”) harvesting salt hay and transporting it on his salt hay barge or his encounter with Watson Lippincott, who—in his eighties—would emerge from his “scowboat” (a houseboat) and build rowboats, but, in his earlier years, had clammed and oystered on Great Bay. Beck punctuated these observations when he visited Len Sooy “on the porch of the weather-blackened house his grandfather had built ... leaning back on the settee made by his grandfather’s father,” sporting “his great shaggy head ... blown wild all that day by winds that swept down Little Egg Harbor and in across Great Bay, rocking his clamming garvey [boat].” Ancestral connections—artifactual, occupational and environmental in scope—gripped Sooy, his patrimony giving way to the everyday exigencies of work, his harvesting of “clams and oysters the daily fulfillment of a sacred trust” (Beck 1945: 45-46, 61, 76, 102-104, 205-206). Few informants moved Beck like Sooy, his presence and testimony compelling in their own right, but doubly heightened by the manner in which his material world curated bodily experience and environmental longing. Beck recounted:

18 Never overlooking a mythic tether to what he saw as the “real America,” Beck’s readership joins him in a roving narrative crafted to confront tensions arising from the clash of tradition and modernity. Starting at the confluence of Great Bay and the Mullica River and moving upstream, his waterborne procession appeared to be strikingly shadowed by the “hypocrisies ... and the ambiguities of ‘civilization’” presented in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (Denby 1995: 118). When challenged for being overly romantic about the enduring practices of those who worked the Mullica River and Great Bay, he strongly disagreed, claiming that human agency and a historically-charged landscape was being sorely underestimated:

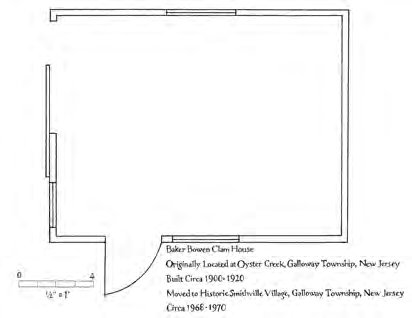

19 During the latter half of the 20th century, Beck’s Jersey Genesis played no small role in fuelling popular interest in the lower Mullica River and Great Bay. The journeys he described of driv ing out dead-end roads to work sites and landings used by baymen soon became common fare of seasonal tourists and automotive day-trippers looking to reconnect with the region’s maritime traditions. Nearby, from the 1950s through 1970s, Fred and Ethel Noyes began assembling what was to become Historic Smithville Inn and Village—a collection of buildings serving as restaurants, shops, and a living history museum only two and one-half miles from Great Bay and Oyster Creek. Buttressing these trends and reinforcing the living history museum’s focus on Southern New Jersey life, one of the buildings re-located to the site was Baker Bowen’s clam shack from Oyster Creek (Courter 2013: 57-114) (Figs. 16 and 17).

Display large image of Figure 16

Display large image of Figure 16

20 Beck’s footprint, along with those who preceded him, was apparent. The sacralizing overtones of his odyssey up Great Bay and the Mullica River (evident in his book’s title) added a pivotal layer to the observations of those who preceded him—it was explicit affirmation of the enduring utility of traditional cultural landscapes. Bristling at the suggestion that the people and places he portrayed offered “little in the way of new contributions to civilization,” he contended they were “preserving something we lack, a true community kind of living and a talent for making an economic order work. Their ingenuity is undoubted” (Beck 1945: 251). Beck had cast the die, and, as evidenced by John McPhee’s writing and the subsequent study of the region by the Library of Congress’ American Folklife Center in the 1980s, anticipated a new era where cultural conservation and environmental consciousness would converge (McPhee 1968; Hufford 1986). The roads and waterways he had travelled were being re-trod, the places he chronicled now subject to a new wave of historical and ethnographic inquiry intent on gleaning, and applying, the lessons of the working landscape. He was leading us to Phil Andersen’s crab house on Oyster Creek.

21 Spare and lean in appearance, these features are what endow the bayman’s modest buildings with the versatility needed to harvest marine resources and endure an estuarine environment where one is never totally land or water bound. Such architecture (along with boats and gear it accommodates) is as nearly amphibious or ecologically consonant as the quarry it is designed to pursue, not only mimicking the estuarine environment, but breathing with it.

22 Whether approaching the Andersen crab house from land or water, its white siding gives it a stark contrasting presence amidst the salt marshes surrounding it (Fig. 18). It sits on pilings driven into the salt marsh, and is located directly at water’s edge on Oyster Creek. While the building’s east and south elevations are clad in contemporary white siding, original cedar shingle siding still graces parts of the north and west elevations, and a dormer window on the elevation’s south side completes the retention of historic fabric on the building’s exterior. A wooden walkway or boardwalk runs the exterior length of the building’s south elevation, connecting the building to a platform supporting walk-in coolers. This south facing boardwalk is bordered by a marsh/flood plain area made firm by successive waves of infill, measures taken to provide space for boat storage, crabbing equipment, and vehicle parking. Connected to this boardwalk is another one running the length of the property in a north-south direction along Oyster Creek. Moored to this boardwalk is the Miss Ginny, a durable, fiber-glass hulled boat known as a T-Craft that Andersen adapted for crabbing and clamming, and later, for guiding waterfowl hunters (Figs. 19 and 20). Honouring tradition, Andersen concedes “there is a real history of boat-building in this area ... something great about the craftsmanship,” and he once used a locally-built, cedar-planked, twenty-eight foot (8.5 m) garvey for clamming—a distinctive regional boat type he sheathed in copper to deter ice damage. But he prefers the T-Craft’s maneuverability for crabbing, and its durability in cold weather months, stating: “When I would go clamming, all the other clammers would wait for me to come out and break ice [with the T-Craft] in the winter” (Phil Andersen, personal communication, January 9, 2019; August 16, 2019)

Display large image of Figure 18

Display large image of Figure 18

Display large image of Figure 19

Display large image of Figure 19

Display large image of Figure 20

Display large image of Figure 20

23 Entering the crab house’s original section and flanking the left side of its sliding door entrance, is a sink and counter (Fig. 21). To the immediate right sits a portable grill, refrigerator, and food storage area. Across this entrance area along the building’s north wall sits a wood stove and storage for slip-on fishing boots, waterproof fishing bib pants (overalls), and waterfowling waders, as well as assorted fishing equipment. Completing this area of the building is an open space where new crab pots can be prepared for use or old ones repaired.1 When not used for these tasks, the space functions as a vibrant social arena where fellow baymen and baywomen, waterfowl hunters, friends, customers, and the occasional unknown, curious (yet welcome) visitor gather for the conversation and food (Figs. 22 and 23). Abutting this area of the building, the later addition retains its shedder tanks but they cease to be used during cold weather and a heavy curtain partitions this space to insure the retention of heat in the original section for waterfowlers who gather before and after hunts.

Display large image of Figure 22

Display large image of Figure 22

Display large image of Figure 23

Display large image of Figure 23

24 The original section of the Andersen crab house was built circa 1934-1937 by Curtis Maxwell, a bayman from nearby New Gretna. Maxwell used it as an oyster house—for oysters he harvested from his cultivated grounds and for those he bought from other baymen. He also used it as a staging area for offering charter boat services to recreational fishing parties—a practice long pursued by the area’s baymen but one that more nostalgically disposed commentators, such as Henry Charlton Beck, saw as potentially “cloaking” the locale’s “forgotten importance” and fostering what Cornelius Weygandt ruefully characterized as “bungalowdom.” In 1954, Curtis’ son, Donald Maxwell, added a one-story, flat-roofed section to the building’s original structure. When Phil Andersen acquired the building in the early 1980s, its exterior remained largely as it appeared when owned by the Maxwell family (Figs. 24 and 25), which had now re-located slightly north of Oyster Creek to a building on Nacote Creek. Andersen adapted the building’s interior space to accommodate his blue-claw crab fishery. By the late 1990s, deterioration of the building’s later addition led Andersen to totally re-build it, replacing its lower, one-story, flat-roofed construction with a taller gable-roofed arrangement that almost identically matched the original structure (Phil Andersen, personal communication, March 16, 2019; August 16, 2019) (Fig. 26).

Display large image of Figure 24

Display large image of Figure 24

Display large image of Figure 26

Display large image of Figure 26

25 Andersen’s initial changes to the building’s interior started with the construction of wooden shedder tanks in both the original section and its later addition (Fig. 27). Designed to hold shedder crabs (also known as peeler crabs) until they fully molt from their hard carapace and become “soft shells”—a prized delicacy—shedder tanks are filled with brackish water that is circulated by pumps for aeration and removal of toxic waste. For nearly twenty years, these built-in features— totalling eighteen—consumed nearly all the building’s interior space and each one could hold as many as five hundred shedder crabs. The culinary quality and marketability of a soft-shell crab hinges on the timing of its removal from various tanks during, and immediately after, the molt. This process was paramount in Andersen’s work regimen during these years and governed the human energy expended in the building. Shedder crabs that are beginning to break open from their shells have soft skin and will be preyed upon by other crabs in the tank. Adding to these concerns, a shedder crab that has completed its molt needs to be quickly removed from the tank before “it gets paper [the cellophane-like beginning of new shell growth] on its back” and has its market value compromised. These demands, particularly when Andersen handled a high-volume of “shedders,” required almost twenty-four hour oversight of the tanks where, in nearly four to five hour intervals, crabs were separated according to their molting stage. When Andersen started to limit his handling of soft-shell crabs, and gradually ceased to harvest clams during the late fall and winter months, he removed the tanks from the building’s original section (Phil Andersen, personal communication, March 16, 2019; August 16, 2019). He began devoting this space—now more open and versatile—to not only his continuing work as a crabber, but to the logistical and social demands of his waterfowling guide service, known locally as “taking out gunning parties.” Oyster Creek’s architectural arrangements, and the friendships they fostered, facilitated Andersen’s transition to guide work in the 1990s (Figs. 28 and 29). Reflecting on these events, Andersen states:

Display large image of Figure 27

Display large image of Figure 27

Display large image of Figure 29

Display large image of Figure 29

26 Occupational tradition shapes the Andersen crab house as an architectural response to its environmental context—a place whose interior and exterior spaces breath in tandem with the biological and physical forces of its estuarine setting. Organizing a working landscape that stretches beyond its four walls, it is the compass of bodily engagement with water and marsh and an organizer of traditional ecological knowledge that sustains its occupant’s respected role as a bayman. Clarifying this synthesis, where the contingencies of everyday labour, the marketplace, and environment converge, are the site’s exterior spaces. While the site’s boardwalk along Oyster Creek provides mooring for the Miss Ginny, it also serves the manageable movement of the day’s catch to appropriate dockside spaces. Bushels of hard-shell crabs are moved along the building’s south facing boardwalk to the walk-in cooler sitting on an elevated platform at the site’s west end (Fig. 30). Soft-shell crabs are unloaded and taken through double doors on the building’s east gable end and placed in shedder tanks. Adjacent to the site’s boardwalks is an area variously used for storing crabbing equipment and parking motor vehicles. Notable in this mix are rows of crab pots—some requiring refurbishing, some simply pulled from use and awaiting resetting, and some needing to be cleansed to remove the accumulation of burdensome aquatic vegetation.

Display large image of Figure 30

Display large image of Figure 30

27 Watching Oyster Creek’s tide rise to meet the top of the crab house’s boardwalks and, at times fully inundating them, is to reckon with the entire site’s elasticity, its capacity to physically embody and culturally archive the lessons of amphibious experience, crafting them into a resilient working landscape. High tides are normal, blow-in tides frequent, and major coastal storms inevitable (Fig. 31). Such considerations put the Anderson crab house’s environmental fit at the centre of collective memory concerning the endurance and erasure of buildings at Oyster Creek. The locale’s clam houses are all gone, but Andersen’s crab house has weathered natural afflictions for approximately eighty-five years. Such endurance is attributed to the building’s one and one-eighth inch thick base sheathing, nailed diagonally for greater structural strength. The original section’s floor boards are two and one-half inch thick long-leaf yellow pine and are credited with shoring up the building’s fortunes during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. They show wear patterns of baymen who have trod them over eight decades and their grayish patina is evidence of countless waves of bay water and mud that have inundated the building since it was constructed. After tidal surge deposited mud in the crab house, in the words of one bayman, “the thing to do was to get down there [Oyster Creek] as soon as you could and wash that out, because if that dried, that’s just like glue, that mud. It’s silt” (Bob Wilson, personal communication, August 24, 2019). Bob Wilson, whose clam house sat next to the Andersen crab house until it was severely damaged by Hurricane Sandy, remarks that the height of dock and boardwalk construction at both sites needed to account for Oyster Creek’s tidal action to insure the manageable offloading of a boat’s catch (Fig. 32). For baymen, faulty dock height creates burdensome lifting from moored boats. Wilson has worked at Oyster Creek since he was seven years old, when his site was occupied by his grandfather, Emery Wilson (Fig. 33), and now observes how rising tidal levels complicate the traditional calculus used to determine appropriate dock height:

Display large image of Figure 31

Display large image of Figure 31

Display large image of Figure 32

Display large image of Figure 32

Display large image of Figure 33

Display large image of Figure 33

28 Recognition of the working landscape’s environmental fit started early for Phil Andersen. His grandfather, Anders Andersen, immigrated from Norway in 1889 and worked in a shipyard in Camden, New Jersey where he built, among other watercraft, vessels for the Atlantic menhaden fishery. Reinforcing memory of this family connection to the marine world are ruins of a menhaden reduction plant within view of the crab house. Andersen’s father, Harry Andersen, and his uncle, Charles Andersen, also worked in Camden’s shipyards, and his father eventually became a tugboat captain. As a boy, Andersen’s family frequently visited Port Republic where he was introduced to duck hunting, and, immersing himself in the area’s surrounding waters, took his first black duck when eight years old. When not hunting, he was fishing for perch in nearby Collins Cove. By the age of twelve he had carved his own rig of duck hunting decoys and earned enough money to acquire a sneakbox—arguably the region’s most iconic watercraft—and used it to hunt from Nacote Creek (Fig. 34). In his teens, he began working as a deckhand on party boats used for serving recreational fishers, and gradually began crabbing and clamming. Returning from military service and having embarked on a job he did not find satisfying, he decided to pursue crabbing and clamming as a full-time occupation (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1930; Georgieff, 2009: 17, 20). He began, in the early 1970s, working the waters of Ludlam Bay and Delaware Bay, areas further south and west of his current location. In the later 1970s, he moved to Green Bank, New Jersey (further up the Mullica River) in order to work Great Bay and its various tributaries, and operated from the Chestnut Neck Boatyard where he moored his boat, stored his crab pots, and maintained a walk-in cooler. It is a transition he tellingly describes: “I moved back up to the area [Great Bay] that I grew up in, was familiar [my emphasis] with” (Phil Andersen, personal communication, March 16, 2019). Long familiar with Oyster Creek’s value as a work site where connections to the area’s crabbing, clamming, and hunting grounds could be maintained, and where water could be readily pumped from the creek to a building containing shedder tanks, he acquired the crab house in 1981. Familiar waters had led him back to Oyster Creek.

Display large image of Figure 34

Display large image of Figure 34

29 Phil Andersen’s crab house is the locus of his working life, a portal to his everyday interactions with the estuarine environment. While readily identifiable as a place where marine resources are moved from their waterborne setting to America’s markets, it is also a place where environmental experience is meaningfully affirmed, coursing through the social and economic reach of Andersen’s life. When Andersen arrives at the crab house during the morning hours of crab season, he first checks the shedder tanks while his fellow crabber, Bobby Dianjoell, prepares menhaden for the rebaiting of crab pots they will check over the course of the day (Fig. 35). No sooner do they leave the landing at Oyster Creek when they are quickly onto their first line of crab pots. In a motion indicative of years of experience, Andersen begins retrieving his crab pots with a fluid rhythm—the boat slowly moving, he catches the pot’s buoy line with a retrieving hook, wraps the line around the electric winch, pulls it up the inclined stern platform, and passes it on to Bobby to be unloaded. Once in Bobby’s hands, the pot’s contents are sorted by size, sex, and potential use as shedders with undersized crabs returned to the water. The crab pot is re-baited with menhaden, locally known as “bunker,” and returned to the water (Figs. 36, 37, 38). The well-honed expenditure of energy and motion displayed in these actions are what allow Andersen and his crew to efficiently tend 250 crab pots in a day, and that, during his most active years, allowed him to tend 400 in a day (Phil Andersen, personal communication, March 16, 2019). Aside from unloading the contents of crab pots, some are re-located to areas, typically warmer waters, where crab activity insures the likelihood of greater catch.

Display large image of Figure 35

Display large image of Figure 35

Display large image of Figure 36

Display large image of Figure 36

Display large image of Figure 37

Display large image of Figure 37

Display large image of Figure 38

Display large image of Figure 38

30 The informed placement of crab pots comes from Andersen’s years of experience in evaluating bay bottom, water depth, and fluctuations in water temperature and salinity levels; it is a series of calculated measures that effect the volume and profitability of his catch, as well as the energy he expends in any one day. His crab house architecturally moors these decisions, directly siting, and then more extensively mapping, his work on the surrounding waters. An occupational axis, it is the place where tangible experience and perception coalesce to inform yet another day of labour amidst the estuary’s fluctuating biological rhythms; in Henry Glassie’s words, it is the architectural tether of an environmental relationship that “grinds the mind sharp, honing wits that dull with ease” (Glassie 1982: 422).2 Andersen’s own description of the sentiment that infuses his working landscape affirms this folkloristic sentiment: “To me, it’s one of the last lifestyles left in America where you really live by your wits and the whims of nature. There is a real challenge to it and I love it” (Watson 2010). Elaborating on the role his crab house plays in organizing his work, Andersen states:

31 Corresponding with the folklorist’s urge to see vernacular architecture as an expression—indeed, a reckoning—of a user’s immersion in a particular environment is historian Richard White’s characterization of cultural landscapes as “tools, the products of work ... extensions of ourselves” that cultivate “bodily knowledge of the natural world” (White 1996: 172-73). For folklorists, and others who share White’s sensibility, vernacular buildings like the crab house are sites of working memory, places framing years of traditional ecological knowledge that continues to inform the labour of those who use them. Gripped by such spatial memory, Andersen reflects on the years when he ventured just south of Great Bay to Reeds Bay whose shallower waters warmed more quickly in spring and promoted earlier crab activity after the species’ dormant winter phase. Now, balancing age and the burden of moving crab pots, he chooses to stay closer to the confines of the crab house: “I may still go to Little Bay, but basically, even in springtime, I don’t go past Little Bay ... I stay up in this area and wait for the crabs to come to me” (Phil Andersen, personal communication, March 16, 2019) (Fig. 39).

Display large image of Figure 39

Display large image of Figure 39

32 At his crab house, the fruits of Anderson’s labour collate with his environmental ethic—his reverence for the resource and its sustainability— and his accountability to fellow baymen. These values—the balancing of individual grit and cooperative spirit—are on display in the building as Andersen achieves communion with waters that bring cultural and economic sustenance not only to himself, but the wider community. Reflecting, he says:

33 When Andersen expresses his deeply felt connection to Great Bay and its adjacent waters—Mullica River, Wading River, Bass River, Mott Creek, Nacote Creek, Ballanger Creek, and Little Bay—he is, at the same time, harmonizing the occupational, aesthetic, and emotional values embodied in his building. In turn, the structure meaningfully blurs boundaries between interior and exterior space, sacred and secular feeling, work and leisure, natural environment and built environment, marsh and water. It is, in short, a work sphere giving equal way—in organic fashion—to an expressive venue, the crab house, the place where Phil Andersen’s soulful endurance achieves fulfillment in his working life: “This has been the greatest place for me, the river. I always say ‘God Bless the Mullica River,’ because that makes this place great, that makes this place great [his emphasis]. We have a perfect mix of fresh water coming down and mixing with the inlet.” Reinforcing this sentiment as material expression, the crab house harmonizes or communicatively fuses human intention and nature’s forces, giving tangible reach to Andersen’s occupational life and the meaningful affiliations and sense of place it fosters: “This has been a wonderful place, and more than that as I start cutting back on the amount of crabs that I shed out, I’ve removed these tanks [shedder tanks] because I’ve needed more space for people that were hunting here, to come in and change ... but the friends and the camaraderie, the friendship and all down here ... it has been such a big part of my life” (Phil Andersen, personal communication, August 16, 2019; March 16, 2019).3

34 Andersen’s dedication to his work, and the sentiment flowing from it, frames the manner in which his building accrues meaning. An outcome of the environmental ethic of the bayman—one that eschews a life of ease, yet quietly revels in the rarely experienced intimacies of being immersed in the estuarine world—his building forges a nexus between his personal desire to follow the water and the response it engenders from the community. The building’s expressive depth emerges from its capacity to bring “coherent aesthetic sensibility’’ (Forrest 1988: x) to Andersen’s occupation, an aesthetic not defined by usual artistic conventions, but a value placed on meticulous placement and retrieval of crab pots, the sorting of the day’s quarry, the unloading of the Miss Ginny, and, when duck season arrives, the informed placement of duck blinds and decoys. Such actions are laden with the “bioregional intensity” Whitman observed throughout the American scene (Killingsworth 2004: 100-101), and show the building aesthetically cohering the contours of an environmental experience where discernable skills and expectations resonate (both for practical and emotive reasons) in community life.

35 For bioregional thinker Robert Thayer, Jr., buildings like the crab house key the ingredients of a particular place’s life giving force, engendering various forms of cultural affirmation that recognize the bioregion as the “logical locus ... for a sustainable, regenerative community” (Thayer 2003: 3). The affective power of this convergence of work and architecture gives rise to emergent feeling that produces talk, social interaction, and historical reflection. In this vein, Andersen’s crab house emerges as a performative venue, a place that not only structures a working relationship with the estuarine environment, but one where deeply felt experience affirms those relationships—not only for Andersen, but all those who feel, or desire, a stake in his enterprise and the tradition he upholds.4

36 The stories and social life that unfold in the crab house extend its role as a cultural anchor. Being the centrepiece of everyday dialogue, the building cultivates a sense of belonging and a collective ethos where problems are deliberated and lives of hard work celebrated. Not unlike Henry Glassie’s observations of the Irish household and its working landscape, the social life of Andersen’s crab house becomes “an epitome of connectivity” (Glassie 1982: 472), the setting where the collective reach of his work finds poetic affirmation in words and deeds. On a winter day, with the crab house sealed tight and the wood stove burning, Andersen’s friend and fellow bayman, Tom Pacula, prepares clams for duck hunters to eat when they return from a day on Great Bay (Fig. 40). The building centres his thoughts when he says: “I just love coming here because it draws me here, because there is something in my heart.” He is talking with John Reese, who has been a regular visitor to the crab house for over thirty years where he moors his boat and helps Andersen maintain his crab pots (Fig. 41). Moved by the building’s context, Pacula goes on, intently reflecting on his decision to work the water and the meaning he derives from it:

He continues:

Display large image of Figure 40

Display large image of Figure 40

Display large image of Figure 41

Display large image of Figure 41

37 During this encounter, Pacula and Reese talk of boyhood days they shared living “in the inlet,” the area of northern Atlantic City where Gardner’s Basin is located and where the city’s commercial fishing fleet was based, as well as some of its most popular recreational fishing amenities. Reese recalls going underneath the docks and buildings (supported by pilings) at Captain Starn’s (the locale’s principal restaurant and recreational fishing centre) and would “catch bait all underneath the building ... all the bait that would go overboard, scooping up all the bait and the little bluefish eating, jumping around eating the bait and the clam shells would be down there ... I would work at the Atlantic City Tuna Club as a kid ... and used to carry five gallon buckets of chum (ground up fish bait) to the recreational fishing boats” (John Reese, personal communication, December 26, 2018).

38 The tone turns reverent as Pacula recounts early lessons he learned as boy from his grandfather, a scalloper who worked out of Gardner’s Basin. Hardly concealing sentiment shaped by his years of working the water, Pacula reminds me that “the bay is a wonderful experience, and if you have never lived it, experienced it, it is very hard to explain it to somebody about what it means to you” (Tom Pacula, personal communication, December 26, 2018). Not unlike Michael Ann Williams’ assertions regarding memory in Appalachia’s “homeplaces,” Pacula’s “narrative form has the ability to give expression to these intangible aspects” of the crab house, its relationship to Great Bay, and, in his own thoughts and actions, to those places he values in the wider vernacular landscape (Williams 2004 [1991]: 20). Pacula’s work and words converge in his quest to map a meaningful life on the water, substantiating Kent Ryden’s notion that:

39 The reckonings Pacula describes find resolution through the social life of the crab house. Empowering his voice, the building’s narratives define its significance as a “storyscape” where “memory making” unfolds with decided purpose, a juncture of material life and oral culture where the bayman’s sense of place is affirmed and where a traditional occupation’s contribution to bioregional dialogue is expressed (Kaufman 2009: 38-74; Page 2016: 29-30). Those whose livelihoods rely on the harvesting of commonly-held marine resources are always awash in shifting ecological contexts, changing stock assessments (both official and unofficial), and contested sentiment over how such resources should be managed—from the number of crab pots placed in the water to a duck hunter’s bag limit. These challenges require talk—sometimes affirming and harmonious and at other times debated and conflicted. Places like the crab house have consistently provided an expressive venue to not only deliberate or reinforce the historical and contemporary claims of their users, but, in an era of more reflexive folklore practice, should be recognized as vital locations for fieldwork exchanges and “shared authority” that might better advance the sustainable use of natural resources (Borland 1998: 320-32; Frisch 1990; Clifford 1988: 21-54; Marcus and Fischer 1986).

40 Today, recognition of the value of traditional ecological knowledge in natural resource management calls for a realignment of our inquiry into the crab house to see how its multiple uses and expressive dynamics have applications in these areas and broader public discourse; in short, this built environment offers possibilities for the application of public folklore.5 As previously discussed, an earlier cohort of writers, documentarians, artists, and government reporters had such ideas in mind when they put the social and working life of buildings, like the crab house, squarely at the centre of their cultural commentary and scientific investigations. The Andersen crab house rekindles this tradition of appreciating the broadly applied lessons of vernacular landscape, of examining how buildings translate environmental experience and then communicate it—indeed, give it resonance and relevance—to overlapping communities who value enduring connections to the estuarine environment. Mary Hufford brought focus to these possibilities when she identified the bay-man’s vernacular landscape as a material and oral interpretation of environmental experience, an inextricable nexus of expressive folk genres that put the crab house at the centre of a traditional occupation’s use of marine resources (Hufford 1987: 13-41). Hufford’s insights, along with Tom Carter’s and Carl Fleischhauer’s observations of Utah’s ranching landscapes, unveiled the often unseen environmental ethic that drives the creation of these sites, a turn toward using the desire and restraint embodied in these places as source material for environmental planning and cultural conservation (Carter and Fleischhauer 1988). Such documentary thinking inserts the crab house into wider community service, its capacity to prompt spatial memory bringing forth the acute observation and versatility needed to ensure occupational survival and its broader social dividend.

41 For Andersen, during his years of more intensive soft-shell crabbing, this meant capitalizing on the “big shed” when crabs emerge from their dormant stage in the spring and simultaneously molt in greatest number. The value of soft-shell crabs heightened the urgency of the tools and knowledge he brought to bear on their harvest. As Richard White notes, Andersen’s tools—his building, his boat, his crab pots, the entirety of his working landscape—become an “extension” of himself that serve to express his “history of past work ... history ... turned into bodily practice” that, as we have discussed, “is unconsciously observed, imitated, adopted, and passed on in a given community” (White 1996: 179). The maneuverability of his T-Craft boat became vital in tending crab pots that were closely placed during the shedder/peeler run (Phil Andersen, personal communication, August 16, 2019). Beyond rote harvesting, Andersen notes that a critical environmental reading informed the use of his tools:

The first peeler run is the big run of the whole season. Almost every crab is involved. Either a big male carrying a female that he’s going to mate with and she’s going to be a shedder. But the first run is predominantly immature females who are becoming sexually mature and it will be the last time they shed their shell in their life.

But in the springtime, males are worth a lot more money, because they’re scarce. So, we want to sell them, but, at the same time they’re worth their weight in gold, because during that first shed we use the male crabs as bait. We put the male crabs, we call them Jimmy crabs, in the pots and all those females who are becoming sexually mature, which are overwhelming in that first peeler run, are looking for a male to mate with. I have pulled up pots with two or three male crabs and have 200 perfect female shedders.

So, the first shed is the big shed, the first peeler run. Everybody thinks that it happens on the full moon, but it could happen on any moon. It is a bunch of conditions that have to be right at the same time, a lot of it has to do with water temperature, you need water around sixty degrees. (Phil Andersen, personal communication, March 16, 2019)

42 Taking us from the crabbing grounds back to the crab house, Andersen describes the process of shedding out crabs in the building’s tanks or floats:

43 As our fieldwork exchange unfolds, Andersen guides me the full round of his working landscape, and, taking pause, reflects further on the handling of a marine resource that factors so prominently in the region’s identity from its harvesting to its consumption at dinner tables:

Display large image of Figure 42

Display large image of Figure 42

44 Phil Andersen’s crab house maps his occupation’s broad sweep into community life, and reveals deliberation and versatility that, according to Kent Ryden, are central for “people who are both in and of the landscape, whose worldview is predicated not on exploitation and destruction of nature, but on understanding, respect and preservation.” These traits are tested in “the mirror that nature provides,” imparting insights that the building’s occupants and wider society can use to craft an equitable convergence of environmental planning and cultural conservation (Ryden 2001: 50). Memories curated within the confines of the crab house sharpen our perspective on how certain spaces are valued, and reveal experiences that blur the boundaries between artifice and nature. As much as the observer might be moved by the crab house’s capacity to convey occupational integrity—a building that encodes the immutable calling a bayman feels for the water—it is also equally relevant to see it orienting options and decision-making that hinge on nature’s rhythms and more profound ecological change. This prospect acknowledges the seamless experience embedded in the vernacular landscape; in this case, one where the bayman’s actions and expressive behaviour synchronize the palpable biological rhythms of the estuarine environment. It is an enterprise well-suited for folklorists who see the vernacular landscape’s vibrancy tethered to the necessary integration of material life and oral expression.

45 Epitomizing the dynamics behind such landscape experience, Tom Pacula takes pride in describing how he has “eeled, minnowed, scalloped, clammed, crabbed ... I can spurt them [digging clams], seine them [fin fish], Shinnecock rake them [clams], wade them [clams] ... I have learned how to do this, that is how you live… there is not one thing I can’t do ... you have to be flexible, capable of change” (Tom Pacula, personal communication, December 26, 2018).

46 His commentary is but one contribution to quandaries evoked by the crab house’s social scene. These can range from concerns over the sustainability of dredging crabs in winter to not shooting at a flock of sixty ducks while hunting in hope they will return at a later time; it is an action accompanied by the waterfowlers refrain at the site: “Do you want to eat for one day or for the year?” Influenced by a place that is in the “heart,” in the “soul,” Pacula further reflects on his environmental experience and his evaluations of the effects of toxic run-off and natural disasters in Great Bay, saying:

47 A forum for eliciting life history, Andersen’s crab house can take environmental experience and its discourse, and insert it into ethical—indeed, honourable—constructive partnership with cultural conservation. It galvanizes forward-looking options for using marine resources in culturally and ecologically sustainable ways, balanced options that can potentially address Richard White’s concerns with “condemning all work in nature and sentimentalizing vanishing forms of work” or “replacing a romanticism of inviolate nature with a romanticism of local work” (1996: 181).

48 Resonating with feeling and affective depth, the Andersen crab house blurs the lines between being curated—a place maintained for everyday use—and, at the same time, serving as curator—a place where occupational memory ensures that environmental and social relationships are not compromised by the transactional necessities of modern economic life. Behind these relationships are the disciplined desires of the bayman, a calling not solely gauged in the daily economic contingencies that engulf Andersen’s life, but one which honors an equilibrium premised on reconciling nature’s inexorable force with the realities of the material world. Acknowledging this outlook, Andersen remarks:

49 The crab house embodies this measured temperament, keeping the past inscribed in its fabric, epitomizing, in John Ruskin’s words, those earthly forces that bestow on buildings the “sublimity of the rents, or fractures, or stains, or vegetation, which assimilate the architecture with the work of Nature” and those human desires that make it “stand as long as human work at its strongest can be hoped to stand” (Ruskin 1981:172,183).

50 Cognizant of how his building, in a Ruskinian sense, “manages and mitigates” its sublime context (Spuybroek 2017: 189), Andersen is equally aware that this engagement with nature, combined with the building’s “cultural weathering”—the human experience inscribed in its years of use—projects the reach of his work throughout the community and region (Heath 2001: xviii-xix, 182-86). Humourously musing, but also taking seriously the occupational tradition his building represents, he recalls repairs he needed to make to his roof:

Display large image of Figure 43

Display large image of Figure 43

51 Imparting obligation, his tempered handling of the building over time—never abrupt or sweeping in its changes—is a learned response to nature’s rhythms and recognition of the enduring utility of form and fabric (Glassie 2000: 29). For Ruskin, such considerations spoke to architecture’s unshakeable power in shaping memory, “we cannot remember without her” (1981: 169). Taking his cue from this sentiment, Henry Glassie asserts that vernacular architecture “gives physical form to claims and names, to memories and hopes” (2000: 22). The Andersen crab house sits at the inextricable juncture of experience and memory, a place whose lessons, according to Kent Ryden, can convey “environmental knowledge gained through work rather than through leisure or literature ... a sort of environmental wisdom and responsibility, yet one that does not bring with it a corresponding desire to sweep working people off the landscape completely” (2001: 75). This sentiment continues to be as relevant now as it was over fifty years ago when Henry Glassie began placing vernacular architecture at the centre of the folklorist’s quest to interpret how people meaningfully live and work in certain environments. Glassie steered a course not only intent on unravelling meaning in the vernacular landscape, but, like Ruskin, one offering commentary on the enduring relevance of these built environments in contemporary society. Central to the folklorist’s enterprise is the task of seeing how the vernacular landscape is inherited and used by its immediate users, and, as their lives become inscribed in it, show its continuing role in culturally orienting a community’s valued endeavours. These historical patterns undergird the vernacular landscape’s grip on folkloristic inquiry, our exploration into seeing ordinary buildings as a functional and social gauge of ethical—indeed, hopefully sustainable—relations with the natural world.