Article

Everything but the Car:

The Carport as Social Space in Puerto Rican Domestic Architecture

Résumé

Le carport, ou auvent de voiture, espace fonctionnel sans caractère particulier dans la plupart des maisons portoricaines, abrite souvent différentes pratiques sociales au cours de l’année. Des activités quotidiennes telles que la lessive et la garde d’enfants s’y déroulent souvent, mais il s’agit aussi d’un lieu consacré aux évènements exceptionnels tels que les anniversaires, les rassemblements sociaux et les fêtes de Noël. Exclusivement conçu pour abriter la voiture, le carport sert souvent à tout sauf à cela. Afin de comprendre comment cet espace s’est trouvé d’autres finalités, cet article se concentre sur l’histoire de l’apparition de la voiture et du carport à Porto Rico. La transformation d’un espace à fonction unique en espace aux fonctions multiples ayant des signifiants culturels distincts s’est faite peu après la diffusion du carport dans les options de construction résidentielle. L’histoire de la relation coloniale entre les États-Unis et Porto Rico est liée à l’histoire des changements de forme de la maison nord-américaine, en particulier des espaces les plus utilitaires au sein de la sphère domestique. Le carport reflète les rêves et les illusions de l’ascension sociale et la façon dont celle-ci s’est mise à retomber, dans une chute libre économique qui a commencé en gros en 2007 et qui continue, échappant à tout contrôle.

Abstract

The carport, a nondescript functional space within a majority of Puerto Rican houses, often accommodates different social practices throughout the year. Daily household activities such as laundry and childcare often take place in the carport, but it is also a site for landmark events such as birthdays, social gatherings, and Christmas parties. Designed exclusively for car storage, the carport is often used for everything but the car. In order to understand how this space came to be repurposed, this article focuses on the history of the introduction of the car and carport in Puerto Rico. The transformation of a single-use space into an all-purpose space with distinct cultural signifiers happened soon after the spread of the carport. The history of the colonial relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico is tied to the story of changes to the North American house form, particularly the most utilitarian spaces within the domestic sphere. The carport reflects the dreams and illusions of upward mobility and how that came crashing down in a seemingly economic free fall that began roughly in 2007 and has continued spiraling out of control.

1 Some of my earliest memories of Christmas Day consist of running around with a new toy, hearing the soft murmur of grownups chatting within the house—punctuated by sharp laughter—rain pouring outdoors, and the smell of dense greenery at my grandfather’s marquesina. This large, spacious, roofed terrace fit a hammock, eight chairs, and a table, all the while allowing for ample floor space to run around barefoot on the cool terrazzo floor. The space opened up to the winter breeze that flowed from the hills of Bayamón, bringing with it the smell of ozone and my grandmother’s garden. The marquesina was protected by a partial wall of open concrete ornamental blocks and curved wrought iron grills that kept us from falling down the sloping hill. At six I was aware that the marquesina was the carport, where the car was meant to be stored, but that was never the functional association I had with it. Rather, the carport served as a large extension of the five by ten foot porch that contained the main entrance to the house. The marquesina was the place to be when visiting either of my grandmothers’ houses, used in a variety ways from a safe play space for us children, to birthday and holiday family gatherings, to baptismal parties and the novena prayers for our recently departed. It was cleaned daily with a hose and/or mop. These varied interactions within the marquesina were not limited to my family but were considered expected behaviour within the daily lives of most families throughout Puerto Rico who either lived in a house with a carport or knew someone who did. With the advent of industrialization and modernity, the carport took on many of the traditional roles of the batey, or padded earth yard, where Puerto Ricans historically spent much of their daily lives.

2 Modern architectural construction methods and vocabularies popularized in the United States were introduced to Puerto Rico through a combination of U.S. federal and private projects during the mid-20th century, completely changing the built landscape in the process. A new architectural vocabulary used throughout the island took its inspiration from architect and development company subdivision designs. Most marquesinas, or carports, form part of the house façade and are made with the same concrete block and flat concrete roof as the rest of the dwelling, located directly to the left or right of the main entrance with access to the kitchen or similar areas, and in many cases connected to the front door via the front porch (Fig. 1). Fernando Luis Lara observes a creation of a vernacular modernism in Brazil in his writing about the collapse of the dichotomy between modernist architecture and traditional construction practices by homeowners and builders, a phenomenon that co-occurred in Puerto Rico along with other places around the world that adopted modernism as the main building vocabulary (2009: 44). In the context of Puerto Rico, not only did the modern carport become a standard component in most single family houses following the introduction of modern architectural forms, but the space came to take on a plasticity that allowed its uses to creatively change during the course of the day, but also throughout the year—even reflecting key moments in the life stages of the inhabitants. The movement of the car, furniture, laundry, and other objects along with social interactions reflects a constant vernacular re-codifying of space through the assemblage of disparate parts not unlike the contemporary Wiccan altars researched by Sabina Magliocco (2001). Although the space itself has often been altered through the construction of walls or, conversely, to amplify it, there is always the standard open minimal space that would hypothetically fit the car when needed. This runs contrary to more permanent alterations made to other intimate car-house related spaces, such as the modifications done by homeowners to mobile homes in the United States in order to personalize and customize them to the resident’s needs and tastes (Jenkins 1990; Wallis 1989).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

3 A utilitarian space, the carport was conceived by designers in the United States for the sole purpose of car storage, yet in Puerto Rico it allows for flexibility unparalleled in the rest of the house. The carport was considered preferable to the fully-closed garage due to its efficiency in material usage while still fulfilling its main function in protecting against rain. In its design, the carport is suited to creative reprogramming due to its openness, proximity to the house, and liminal nature as a conduit between the privacy of the home and the public, exposed exterior. The space shares common vocabulary with both the batey in its openness and public/private duality, and the concept of balconies, porches, and verandahs, which serve a similar yet more constrained function, offering partial protection from the elements with a roof while limiting contact with the exterior.

4 In order to understand the current and historical uses of the carport in Puerto Rico, I visited the city of Arecibo on the northern coast of the main island during the summer and fall of 2017. During both informal conversations and more structured interviews with my informants the use of the marquesina as a social space was often talked about in the past tense, with a twinge of nostalgia. This perception of a disappearing tradition led me to pursue the following research questions: As an architectural feature, how widespread are carports? Are they being used for purposes outside of car storage? How are people using the marquesina on a day-to-day basis and are these uses similar across different types of communities? My main methods involved a comprehensive building documentation survey that sought representation of different urban typologies, including the historic town centre, subdivisions, a parcela (informally organized community grown out of plots of agricultural land redistribution during the 1930s), and an online survey on the perceived uses of the marquesinas in Puerto Rico. Interviews, ethnographic observation, and archival research provided further information. While doing fieldwork in the various communities of Arecibo, I allowed the buildings to tell their own story through the documentation of form as they were presented at the time of recording (see Glassie 1975). In an attempt to understand a space that is perceived to be in the past, the performativity of inhabiting space through memories, rather than the actual space, became pressing (Williams 1991).

5 A major component of my research was to understand how the marquesina became so widespread, which necessitated tracing the history of the car and car storage in Puerto Rico within the framework of cultural shifts that impacted diverse facets of society, including spatial usage in the domestic sphere. The carport is a relatively recent addition to domestic architecture vocabulary worldwide, created as an airier alternative to the enclosed garage during the mid-20th century (Fox and Jeffrey 2005). The story of how the carport became a taken for granted part of the landscape is tied to the history of rapid change across Puerto Rico during the mid-20th century, especially through the implementation of the car as the main mode of transportation along with the rampant development of subdivisions known as urbanizaciones for a burgeoning middle class after World War II. These radical changes to a landscape that was formerly agrarian—dotted by vernacular forms of architecture made of local and renewable materials—to one based on concrete and pavement was intentional and implemented as part of a flurry of U.S. federal government initiatives aimed to improve Puerto Ricans’ quality of life in a way that would reflect 20th-century ideals of modernity and progress in the United States.

Breaking with Traditional Construction

6 Before the mid-20th century, a substantial percentage of Puerto Ricans inhabited vernacular structures of wood frames ranging from the Indigenous straw and palm bohíos to casas criollas made of wood and zinc. Landscapes often combined elements of both depending on the access to localized materials and economic class. The bohío was based on Taíno design and incorporated Spanish and African influences. It was built with a combination of palm and hardwoods and roofed with palm or grass-based thatch (Medina 2012; Vlach 1978; Jopling 1988). Bohíos were relatively small, measuring approximately between 168 and 620 square feet and often accommodating large families (Department of Education, Puerto Rico 1934: 37). Many of the daily and social functions took place outside on the batey or padded earthen yard, or in liminal spaces such as balconies, porches, and the guariquitén or Indigenous verandah, when possible. Houses were accompanied by a series of auxiliary buildings including the kitchen, ranchón, outhouse, and the low lying tormentera or storm shelter for hurricanes (Fig. 2).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

7 The batey defined the exterior living space of the dwellings, anchored the surrounding supporting structures, and would often become the central location for neighbourhood congregations. The term has been used to define different types of open-air spaces of both Taino and West African influence throughout the Caribbean, from the connective tissue between informally placed houses to the grounds of sugar estates, particularly where social and domestic life happened between the 19th and early 20th century. The batey became the place to chat with neighbours, play games, host parties, and partake in daily social life (Ortiz Colom 2008: 6).

8Carmen (Carmín) Arocho and her husband Pedro (Pellín) Feliciano Fernández were both born and raised in Barrio Dominguito in the municipality of Arecibo. Dominguito is still considered rural because it was historically agricultural land and continues to have a strong agricultural presence. However, the barrio has seen many of the changes to the Puerto Rican landscape that happened in the 20th century, moving from being sparsely populated and built-up to having various small subdivisions and other organically formed neighbourhoods. Both Carmín and Pellín witnessed many of these changes to the barrio and the landscape. Carmín recalled:

9 Daily scenes such as this one were repeated throughout rural and semirural regions of Puerto Rico, with the batey setting the stage for daily communication between family, friends, and neighbours.

10The batey is also associated with the creation and continual performance of Bomba music and dance by African slaves (see Ortiz Colom 2006), as well as other forms of heightened performance. In 1954, Fred G. Wale, who was working with the Puerto Rican Board of Education, wrote in an open letter published in Marriage and Family Living:

11 Wale was making an argument on the character of the Puerto Rican community he was interacting with, but in the process was able to observe a joyful, and possibly a carefully curated performance on his behalf in the batey.

12 The bohío and batey were systematically eradicated from the landscape beginning in the 1930s after a series of devastating hurricanes swept through Puerto Rico in 1928 and again in 1932. Hurricanes San Felipe II, known as the Okeechobee Hurricane in the United States, and San Ciprián, were massive storms that decimated the landscape, taking with them the coffee crop and destroying a large number of the more ephemeral bohíos. Hurricanes have always been a Caribbean reality. That houses would have to be rebuilt after a storm was understood by inhabitants from precontact times, through the Spanish colonial period, and into the 20th century after the United States annexed Puerto Rico from Spain in 1899.2

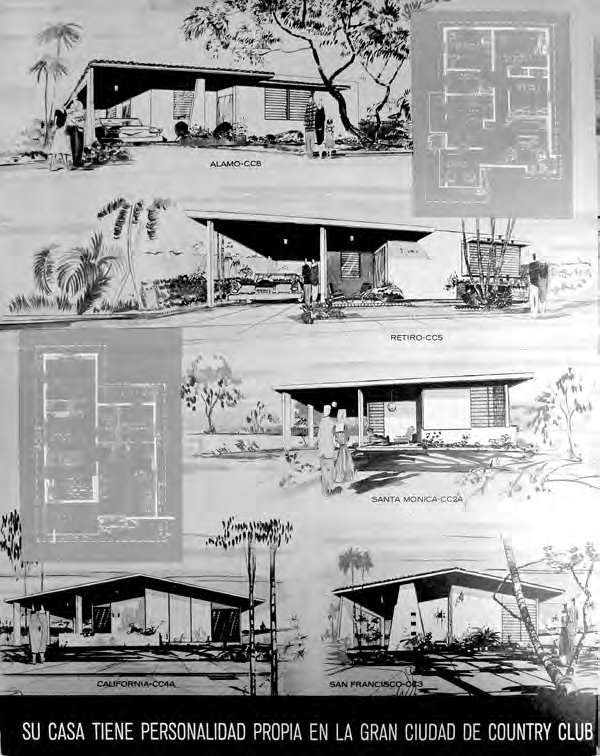

13 The presence of the United States did not indicate an immediate shift in construction practices, however. Most federally-funded initiatives at the start of the 20th century were aimed at institutional facilities rather than housing. The hurricanes of 1928 and 1932 were the main catalysts towards increased efforts to find sturdier construction systems. By 1934, according to a report by Puerto Rico’s Department of Education, 115 families out of a group of 150 studied in rural Puerto Rico were living in houses of wood and zinc, materials provided by relief organizations after the storms (34). There was a concern that traditional bohíos were not only fragile, especially after the recent destruction wrecked by the two massive hurricanes a few years earlier, but were also viewed as prone to overcrowding with anywhere from between three to six people per bedroom (37). The general physical and “moral” well-being of the families residing in these vernacular structures due to the “mixing of the sexes” from lack of space and privacy, was as concerning as the lack of interior plumbing, electricity, and structural integrity (Medina Carrillo 2012: 120).

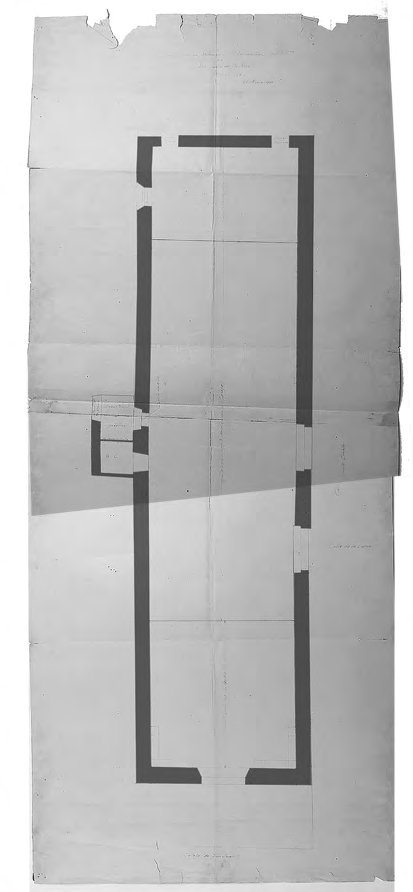

14 As a result, the United States Federal Government introduced sweeping policy changes through the implementation of the Puerto Rican Emergency Relief Administration (PRERA) in 1933 and the Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration (PRRA) a few years later. These two programs fell within the scope of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, impacting every facet of Puerto Rican life and irrevocably changing the landscape. Everything from industry to healthcare to infrastructure were intervened upon at different levels. Clean, safe, and modern housing was a top priority of the PRRA initiative. Administered by the Puerto Rican government, the PRRA was used to identify housing typologies that would serve in both rural and urban settings. Concrete and rebar, materials that had begun appearing in Puerto Rico since the turn of the 20th century, were made more accessible and gained visibility through the experimental housing project. Although buildings in brick, poured concrete, and metal were built, the vocabulary of minimalist concrete box houses as alternatives to vernacular wood structures began making inroads. The original experimental houses were not much bigger than the bohíos they replaced, nor did they take into consideration the potential for car ownership or even interior bathrooms (279), but this was the beginning of a popularized modern building vocabulary (Fig. 3). Many of these small houses were built on plots of land known as parcelas which were the result of “Parcelas de la Reconstrucción Rural,” a land redistribution project through the PRRA with the purpose of providing land titles to the formerly landless (Medina Carrillo 2012: 97-98). The PRRA waned and was eventually discontinued in the 1940s yet it succeeded in bringing about lasting changes to local concepts of housing, land usage, and durability.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

15 As new construction materials and designs were made more accessible to the general population, the pieces for the postwar boom that would lead to a marquesina in most houses were being put into place, although without economic accessibility to the general population. Both cars and urbanizaciones in Puerto Rico had existed since the turn of the 20th century but had been accessible to an elite few. According to the October 28, 1899 issue of the Gaceta de Puerto Rico, the earliest automobile permits in Puerto Rico date back to 1899, just one year after the United States invaded Puerto Rico, when the U.S. military’s Civil Division granted Fitzgerald Marquard Eng. Co. permission to operate mass transportation “on any or all military roads of the Island…” (1). From May 1902 onward daily trips between San Juan and Ponce were being announced in a Puerto Rican mercantile newspaper (Automobile Transportation Co. 1902).3 By 1918 there were ads for new cars, tires, and automotive services every few pages, nestled between news of the Great War and the earthquake of 1918 in the Puerto Rico Ilustrado, the preeminent magazine for Puerto Rico’s upper class during much of the 20th century. The earliest garage plans stored at the Architecture and Construction Archives at the University of Puerto Rico (Archivo de Arquitectura y Construcción de la Universidad de Puerto Rico or AACUPR) are dated to 1912 and consist of alterations to a brick masonry building in Old San Juan (Fig. 4). The earliest example of a porte cochere, the predecessor of the marquesina, might be attributed to the architect Antonin Nechodoma in his design of the Georgetti House, a palatial Prairie School building in Santurce designed in 1917 and built in 1923 with a horizontal overhang for stepping into the house (Díaz 2004) (Fig. 5).

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

16 Mary Frances Gallart describes the earliest urbanización, El Condado. Designed in 1907 as an exclusive residential area for upper and upper-middle-class residents of San Juan, El Condado emulated planning systems in the United States (2000: 32). A large ocean facing lot of land measuring about 260,000 square metres was subdivided into 1,600 lots of various sizes and planned with boulevards, plazas, and amenities. Fourteen houses were standing by 1908, just one year later (36-37). The houses, based on popular designs in the United States, such as the bungalow, were the first sign of the planning style that would envelop most of Puerto Rico much later in the century.

How the Marquesina Became Endemic

17 The elements put into place during the first half of the 20th century, such as the introduction of materials like cement block, urban planning precedents, the introduction of the automobile as a primary source of transportation, and modelling citizens as consumers, set the stage for the great construction boom of the 1950s. There were multiple factors occurring in a short period of time.

18 After World War II, as the concept of direct colonial rule was going out of favour, Puerto Rico’s system of governance shifted from having a congress-named governor to electing their own governor in 1948, to becoming a commonwealth (Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico) in 1952. The boom in urban development occurring in the United States after World War II was reflected similarly in Puerto Rico, with returning veterans entering university and integrating into an expanding public workforce as well as newly opened factory positions (Sepúlveda 1997: 39). This new construction boom was shaped on the Fordist inspired living system that prioritized consumerism, individuality, and the concept of private property.4 This system was replicated to great effect in Puerto Rico as the federal and state program “Manos a la Obra” (“Operation Bootstrap”), sought to stimulate the economy through private industry growth. Arguably the spiritual successor of the PRRA, Manos a la Obra continued to develop infrastructure, education, and most notably the economy, with a noted emphasis on industry. Speculation in construction was considered a win-win for a population that still needed housing, offering stimulation to the economy through the construction industry and reshaping what an optimist future could look like. The accompanying private subdivision-centred housing system would become the staple of private housing construction throughout the entirety of Puerto Rico over the next fifty years.

19 The proliferation of the automobile was central to this rapid urban development, shaping the urban and suburban landscapes, changing spatial interactions, and blurring the concept of urban and rural areas (Marqués Mera 2000: 203). House and car ownership were encouraged through advertisements, word of mouth, and low interest long-term loans. Car ownership went up from 12 cars per 1,000 inhabitants in 1940 to 76 cars per 1,000 in 1960, an increase of over 600 per cent in a twenty-year period (Sepúlveda 1997: 30). Housing units grew at an even faster rate, particularly in urban and newly created suburban areas. New construction in urban areas, mainly in San Juan and the surrounding townships, had stalled during the early 1940s during the Second World War, with a low of 88 new houses units built between 1943-1944 (Housing in Puerto Rico 1950: 11). The amount of new housing jumped to 1,883 units between 1945-1946 and quadrupled between 1948-1949 to 5,402, most of which were located in the new Puerto Nuevo subdivision, thought to be the biggest housing development of its kind planned and built until that moment (11). Caparra Terrace, a massive addition, was added in the following years, elevating the number of houses to approximately 7,000 units (Sepúlveda 1997: 35). Although the enormous subdivision was strategically placed around one of the main road arteries on the outskirts of San Juan, the houses did not include space for car storage, even as cars were becoming more economically accessible.

20 Designed and built for an up-and-coming working and middle-class population, Puerto Nuevo’s design reflected how most subdivisions in Puerto Rico would take shape from the planning scale to the most intimate details. The developers provided house plans that would snuggly fit the lots which measured approximately 40 x 60 feet. All of the houses were built of concrete block tied with rebar, with evenly interspaced structural walls and overhanging flat roofs made from poured concrete. The “Miami style” windows were designed to provide security and ventilation, although their placement did not take crosswinds into consideration. The space was purposefully designed to reflect houses and the ideals of home living in the United States.

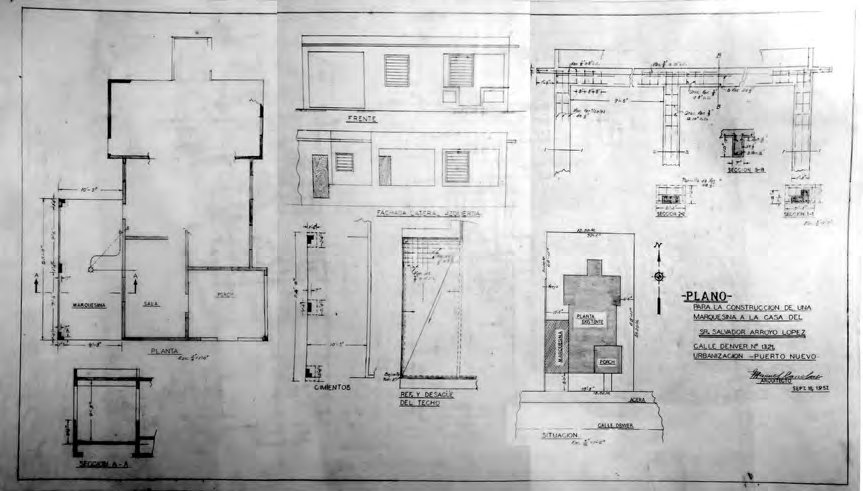

21 One entered the house through the balcón or porch directly into the living room. The kitchen was located in the middle towards the front, with the bathrooms after, and two or three bedrooms clustered in the back. Each space reflected a purposefully designed use and included the necessary electric outlets, plumbing, and other required amenities such as space for appliances in the kitchen. The marquesina was not a required component of the design even though the subdivision was designed for the purpose of commuting to the city centre. When the carport was present, it would often have a direct entrance to the kitchen, emulating the practical designs of similar subdivisions for in the mainland United States, using these two functional spaces for transitioning between the house’s interior and the driver’s destination. As in the case of houses with garages in the mainland, the more informal entrance was, and continues to be, preferred by the residents, reserving the main entrance, and access to the formal living room for formal occasions and special guests. Some houses in higher end subdivisions would play with the format and include the main entrance behind or attached to the carport. However, these always included a visual cue to separate the space for car parking and the entrance to the house. The template reflected in Puerto Nuevo would be replicated throughout Puerto Rico, in both future subdivisions and individually built houses over the next fifty years, although the carport would become as standard in new designs as a second bathroom (in most cases). In Puerto Nuevo, the lack of parking space did not last long as people began extending the flat roof of their houses into carports as soon as they could afford it. Architect Manuel Canelas submitted a carport addition for Puerto Nuevo resident Salvador Arroyo Cópel in 1957 (Fig. 6). The carport measured ten and a half feet wide, extending to the very edge of the property.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

22 Even as Puerto Nuevo and Caparra Terrace attracted much attention due to their size, other subdivisions were quickly cropping up throughout the greater metropolitan region. Architectural and engineering firms partnered with developers, realtors, and contractors to buy land, create a set of designs, and promote them through speculative development. This became the main model for large scale private housing construction. The model was used for both multifamily housing and subdivisions. In the 1950s, land was considered cheap and bountiful. Rural populations were migrating in massive amounts to urban centres as the economic model incentivized industries— mainly factories from the United States—over agriculture. Subdivisions, with the promise of a house and land per family were considered the more popular alternative. Developers marketed their houses through the prospect of modernizing with a clean slate, leaving behind the concept of rural cultural backwardness by purchasing the promise of a better future. A considerable amount of money was invested in brochures and advertisements. Even the names for the developments and housing designs were carefully curated to create a sense of desire (Campos Urrutia 2010).

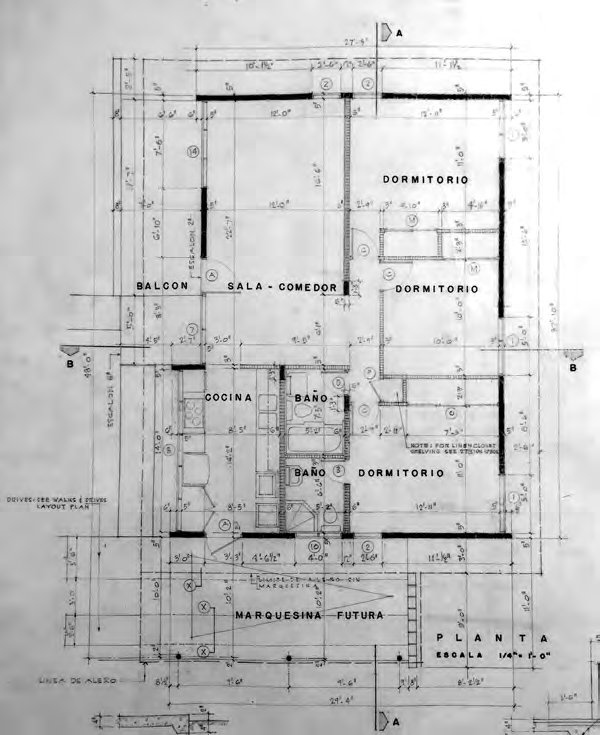

23 Developers began incorporating the marquesina as a standard addition to new subdivision design options in recognition of the growing popularity and indeed the necessity of cars as a means to commute to work. The urbanización University Gardens, designed in 1958 by the design firm of Amaral y Morales Arquitectos provides a transitional example. Located walking distance from the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras, the subdivision was aimed at professors and young working alums and their families. Potential clients were offered a slew of slight design variations that would be adjusted to the lot they brought with flattering names based on gems stones such as Safiro (Sapphire), Esmeralda (Emerald), and Ópalo (Opal), among others (Fig. 7). The designs were meant to accommodate the tastes, needs, and budgets of individual families. Every design offered the possibility of adding a carport at a future time, an additional cost that the client could take on at the moment or postpone for later. The central location of Río Piedras, with access to public transportation and at a walking distance from the university, made it a bit of an anomaly in terms of car storage options as commuting was less of an issue.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

24 Other urbanizaciones in the 1950s such as the Country Club located between San Juan and the neighbouring township of Carolina, were designed specifically for longer distance commute with the use of the car. As in the case of other development projects that were cropping up simultaneously, the developers of the Country Club used brochures to offer a variety of options, highlighting the simplicity and minimalism of the designs and featuring the carport as a prominent feature at the front of each house design option (Fig. 8).

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

25 Both large and small scale urbanización speculation projects began cropping up throughout the urban centres of the vast majority of Puerto Rico’s 78 municipalities.5 Subdivisions throughout Puerto Rico were considered the epitome of upward mobility by a large portion of the population. The buildings were new and solid, built of reinforced concrete blocks to withstand both hurricanes and earthquakes, and lined up neatly along a road rather than clustered around a batey. The designs were standardized, often taking their cues from the precedents set in the San Juan Metropolitan area. The flat roofs and minimalist lines were incorporated more as a matter of cost cutting in speculative construction than as an ode to Modernist design principles. Standardized factory-made materials made construction a relatively inexpensive and quick investment.

26 Young families that benefited from upward mobility through new factory jobs and university education took advantage of the accessibility of cars and homes and moved to the urbanizaciones. Government programs in the 1950s and 60s such as Ayuda Mutua Esfuerzo Propio (Mutual Aid through Own Effort) provided plans and materials through a low-cost loan so that people could build their own houses with help from the neighbours (Calaf Seda 2012: 25). The materials and designs shared many of the basic principles with urbanización buildings, primarily in the use of concrete block as the main building material and visual simplicity. The design precedents however, were not limited to preplanned subdivisions or government designed templates, becoming the standard of informal and vernacular construction in both urban and rural areas throughout Puerto Rico. Many casas criollas, originally built in wood, were rebuilt with an updated variation of their original floor plans in concrete blocks. Many concrete houses throughout Puerto Rico built between the 1930s and 1950s were retrofitted with concrete slab roof marquesinas, usually fitting one car. This was a phenomenon that I observed throughout Dominguito where small concrete houses built through the PRRA and later Ayuda Mutua were expanded and retrofitted after their original construction in order to update them to contemporary needs.

27 Eurítida, known as Ori, was born and raised in Dominguito and recalled how her father built a simple concrete house with a living room and two bedrooms in 1947. The kitchen was a small structure apart from the house, and a separate latrine served as the toilet. Over time, her father incorporated a modern kitchen, running water, electricity, a bathroom, an extra bedroom, and a carport. He added the carport in 1965, after the family was able to afford their first car. The construction of a carport was an investment. Even without building walls, building two columns and a flat roof out of concrete just for car storage required savings and time. Like many others who could not immediately afford a carport, Ori’s father kept their car in a barebones shack made of four wooden posts and a zinc sheet roof until he saved up enough money to build the concrete structure (Eurítida, personal communication, August 30, 2017).

28 Not everyone would be able to save up for a marquesina even when they became much more economically accessible. In Dominguito, where most houses have been built by their owners over time, more than half of the structures I surveyed had marquesinas, mostly in concrete, but a fair share were built in wood and metal as well, a reality reflected throughout Puerto Rico, both within the subdivision constructions that normalized marquesinas but also in most other types of house construction.

The Carport as Social Space

29 The exact moment in which the carport shifted from being exclusively used for car storage to the most versatile space in the house is difficult to pinpoint. One day in conversation I asked my grandmother, Gloria Mulero González, when was it decided to use the carport primarily as a social space. She simply responded: “first we built the carport, then we put the car in, and then took it out.”6 There was no pretense, nothing in particular to commemorate the occasion or elevate it above a mundane practical matter. My grandparents’ current house, just like Ori’s childhood home, was originally built by my grandfather through the Ayuda Mutua program in the 1950s, replacing the original wood house where my mother spent the first years of her life. The marquesina was added after purchasing a car for the family a few years later. It was used mainly for car storage for a time—until it wasn’t. Ori was emphatic during our conversation that the carport was built exclusively for car storage use. Other uses came at a much later date (Eurítida, personal communication, August 30, 2017).

30 How this decision was made, not just by Ori and my grandparents but by a whole generation of Puerto Ricans, remains blurry. When conducting interviews, on more than one occasion events in the past were usually marked as “los tiempos de antes” (olden times) to differentiate a time before traditions were interrupted by modernity, yet the phrase is vague and can shift through the decades to mark different moments of recalling lost traditions. The building and use of the marquesina fell into a memory vacuum that did not qualify as “los tiempos de antes” but is not considered recent, either. Talk would shift instead to listening to conversations on the batey “en los tiempos de antes” or conversely hosting Christmas parties and fiestas de marquesina (marquesina parties, a staple of chaperoned parties for many a teenager) in the 1970s and 1980s (Carmen Arocho and Pedro Feliciano Fernández, personal communication, September 15, 2017).

31 Regardless of how the decision was made to create multiple spatial purposes for the carport, the resulting spatial usage was more akin to a combination of the historic batey, porch, and guariquitén than to the original car storing function. The carport, like the aforementioned spaces, is liminal, connecting the private interior of the house to the network of roads directly. Usually located at the front of the house, to the left or right of the main entrance, the marquesina is highly visible, showcasing the car to all passersby. Even without the car, it continues to be an exposed space visible to the exterior. The floor is often made of terrazzo or ceramic tiles, the same material as the interior of the house, and often provides access to both the kitchen and main entrance, simplifying the flow of movement throughout the space.

32 The openness of the space with protection from the rain and relative coolness in comparison to the rest of the house (most concrete houses measure approximately eight feet in height and the “Miami style” windows provide limited circulation) make it ideal for multiple and often simultaneous uses. Car storage was and is still considered the primary use, although according to the online survey, widely varying activities such as parties celebrating heightened events such as Christmas and Three Kings Day, marquesina parties for teenagers, and day care for young children were close behind in association.7 While documenting the houses of Arecibo, I found that roughly one third of the marquesinas I observed were furnished with chairs, tables, ornamental plants, washing machines, and/or hammocks. Only a quarter of houses had cars inside of them and a similar amount had cars on the curbside or driveway. Interactions with the space change from house to house. The expectations of what constitutes social marquesina usage also changes. As in the case of Lara Pascali’s research on basement kitchens in Italian immigrant homes in North America, daily uses of the carport are considered an assumed and integrated part of daily life, “...naturalized within the community to the point that it is no longer visible” (2011: 49). As in the case of Pascali’s research, this very invisibility provides an insight to the space’s meaning in everyday life.

33 Because of the high visibility from the streets, the marquesina is often kept as clean as possible, washed more often than the interior of the house itself with a hose and broom, and decorated with an assortment of potted plants and easily movable chairs (Fig 9). Over the decades as Puerto Ricans have gained upward mobility and/or family circumstances have changed, the marquesina has expanded to fit additional cars, and often a combination of cars and social uses. Conversely, the space has been partially closed off to create additional rooms or small informal businesses.

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

Continual Changes

34 Up to the beginning of the 21st century, building, subdivision, and road construction continued at a rampant pace with approximately half a million new housing units built each decade from 1970 to 2010 for a total of 1,636,946 reported buildings (Departamento del Comercio de los E.E.U.U. 2012: 5). Even though the marquesina continued to be incorporated into most new construction, the airy openness characteristic of the structure began to disappear in the 1970s due to perceptions of growing crime and insecurity. Residents began installing highly ornamented wrought iron security grills over every exposed opening on the house to discourage break-ins (Fig. 10). The ornamented grills allowed for the continued inflow of air and light but represented the first visceral closing off of domestic spaces from the greater community, a tendency that would be replicated at a greater scale in the late 1980s with the gating of communities. In the last twenty years, as perceptions of crime and economic instability have continued, the marquesina has often returned to the exclusive use of protecting the car, at least at night. Many owners have opted to install mechanical rolling garage doors to increment visual privacy. In 2008, Puerto Rico went into an economic recession that has continued into the present. By 2016, 257,798 houses constituting 16 per cent of all residential units were vacant (Hinojosa and Meléndez 2018: 5). The passage of Hurricane Maria in 2017 has only exacerbated this situation and laid bare many vulnerabilities that had been obfuscated by the optimism of rampant 1950sstyle development over the decades. The cost of building and purchasing houses inflated and then burst with the economic crisis. Coupled with the lack of job opportunities, more and more houses are now being put up for sale or abandoned by despairing owners (Fig 11). The future for both the marquesina and its multiple uses currently remains uncertain.

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 10

Display large image of Figure 11

Display large image of Figure 11

Conclusion

35 The study of traditional places is not limited to analyzing the structure itself but we must take into account the multiple meanings, uses, and social significance codified into its materiality by the inhabitants. This codification is informed by the cultural knowledge and traditions that are passed not just from one generation to the next, but from one building typology to another. The carport in Puerto Rico has had its uses expanded beyond the original intention of car storage, in the process becoming a substantial component in daily life. The spatial usage is more akin to the traditional uses of preindustrial domestic spaces such as the batey and porch, semi-private/public spaces where much of daily life occurred up into the early 20th century. Urban development was used by both the federal United States and Puerto Rican governments as a modernization tool that was meant to improve the quality of life by purposefully breaking with the past and introducing as many technological components as possible. As a result, traditional building types such as the bohío disappeared completely to be replaced by concrete structures and many smaller communities were replaced by large urbanizaciones designed for commuting with the car. The marquesina was considered an efficient and cost friendly solution to car storage and was quickly adopted by a majority of new house owners. However, the marquesina was too large—often taking up to 30 per cent of the roofed structure of a house—to be used for mere car storage and many of the activities that traditionally took place in the batey were subsequently transferred to the marquesina. Although marquesinas continue to be used in a flexible and multipurpose manner, an economic recession combined with the impacts of Hurricane María has put the fate of such domestic spaces into question as more and more people are leaving Puerto Rico for the mainland United States in search of livelihood.