Article

Work, Play, and Performance in the Southern Tobacco Warehouse

Résumé

Cet article considère les entrepôts de tabac du sud des États-Unis comme étant à la fois des lieux de travail et de divertissement. En abordant sous l’angle de la performance l’étude de l’architecture vernaculaire qui s’enracine dans une méthodologie ethnologique, cet article avance que ces lieux du travail quotidien avaient un potentiel festif, nonobstant les restrictions induites par la ségrégation spatiale des lois Jim Crow. Il se concentre en particulier sur les soirées de danse qui rassemblaient de nombreux participants dans ces entrepôts soigneusement décorés pour l’occasion, du début au milieu du XXe siècle. Durant ces soirées de danse, les danseurs noirs détournaient les espaces de travail de l’entrepôt de tabac, restrictifs sur les plans social et économique, en lieux de radicalité potentielle et de plaisir. Les arguments de cet article sont étayés à la fois par une documentation conventionnelle pour ce qui est de l’architecture, et par les témoignages oraux de divers travailleurs, musiciens et danseurs du monde du tabac, qui ont utilisé ces entrepôts avec des intentions diverses, et souvent conflictuelles. Rassemblés, leurs récits soulignent à la fois la résistance localisée à la ségrégation et l’importance des archives éphémères des histoires et mémoires individuelles dans l’étude de l’architecture vernaculaire historique.

Abstract

This paper examines tobacco warehouses in the southern United States as sites of both work and play. Using a performative approach in the study of architecture that is rooted in folklife methodology, the essay claims these quotidian working structures as places of celebratory potential amid the strictures of Jim Crow spatial segregation. In particular, it focuses on a series of massive dances held in the elaborately decorated warehouses during the early-to-mid-20th century. During these dances, Black celebrants turned the restrictive social and economic working spaces of the tobacco warehouse into places of radical potential and pleasure. The claims of this essay are supported by both conventional architectural documentation and the oral testimonies of a variety of tobacco workers, musicians, and dancers, who made use of the warehouses for a variety of often conflicting purposes. Told together, their narratives emphasize both spatialized resistance to segregation, and the importance of the ephemeral archives of individual stories and memories to the study of vernacular architectural history.

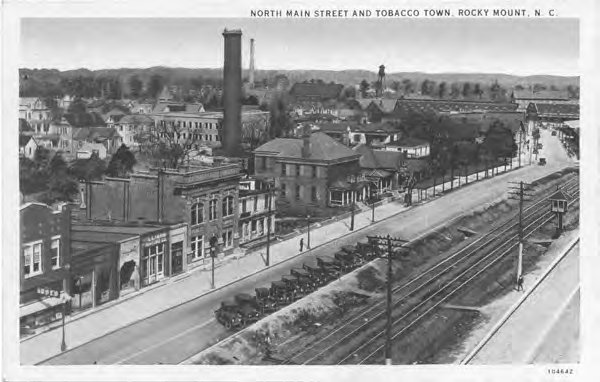

1 For a full century, the tobacco warehouse was the centre of life in eastern North Carolina towns like Rocky Mount. One of a couple dozen self-proclaimed tobacco capitals in the American South, the small city’s downtown was dominated by the sprawling structures meant to store the fall’s tobacco harvest ahead of its sale and production. In these warehouses, generations of white eastern North Carolinians ascended to a middle-class existence through the sale of tobacco. Equal numbers of Black North Carolinians were subjected to low wages, poor working conditions, and dead-end jobs. But the buildings were not just economic entities. They acted, too, as social hubs—gathering spots for African American workers turned celebrants who danced to big (and big name) bands throughout the long summer nights on the warehouses’ emptied floors. At these dances, Black people subverted the meaning of the architecture and carved out a place for themselves in a city, region, and time built in opposition to their success and happiness.

2 Over three decades in the midst of the Jim Crow regime, the massive brick, corrugated steel, and wood-beamed tobacco warehouses of Rocky Mount hosted a series of concerts, dances, and other events for African American audiences. The events transformed these spaces from sites of labour to sites of pleasure and play. This transformation was effected through the interactions of people with buildings and each other, a performance of placemaking.

3 This performative interaction was not just in the formal sense of musician and audience, but more broadly within the scope of the quotidian modes of everyday response and interaction. In this essay, I look at the creation of southern tobacco warehouses alternately as places of work and play. In doing so, I complicate the dichotomous relationship between the two, and point to the disruptions in designed intention that performance can bring to architectural space.

4 This essay charts those contradictions of utility and recounts the ephemeral transition of tobacco warehouses into places of Black entertainment and refuge, of imagining and becoming. The summer dances held in these buildings temporarily translated their meaning amid the intensive spatial and social restrictions of Jim Crow (Berrey 2016). Celebrating in—and with—these warehouses, African American people were consciously performing complex social identities ordinarily restricted symbolically and literally by the tobacco warehouse and its cheap valuation of Black life. These buildings, the work they held, and the dances they played host to, give us occasion to reconsider a performance approach to the study of vernacular buildings and their uses. Departing from the recent architectural formalism of the field while remaining attentive to the specifics of a building’s materiality, I focus on the ways in which performance with and in a building might signal a departure from its designed intentions. In Rocky Mount, performative repurposing opened a world of associational meanings for a broad community of people otherwise excluded from the economic gains offered by tobacco warehouses, structuring imagination of a better and fuller life.

The Architecture of the Southern Tobacco Warehouse

5 The work of tobacco industrialized in the late 19th century. The post-Civil War period saw a rapacious demand for the tobacco branded “brightleaf.” Pioneered in the 1840s, this curing process supposedly produced a mellower, more consistent smoking tobacco that United States soldiers serving in the South demanded after their return home. Farmers and budding industrialists were happy to oblige. In the interior coastal plain and piedmont of North Carolina and Virginia particularly, new investors took advantage of this expanded national market to routinize the golden leaf’s production. From this consumer demand came the birth of the American tobacco industry (see Hahn 2011; Joseph 1967: 43-73).

6 The industry had an immediate impact on the built environment of tobacco growing regions. Log curing barns were built along roadsides and on fallow lands and other unusable agricultural spaces of most farms. County seats and mercantile centres became tobacco towns, filling up quickly with industrial-scale storage and processing buildings to meet the output of the surrounding countryside. Factories, stemmeries (for removing stems), and prizeries (for packing and aging tobacco), were quickly built into the expanding fabric of these small towns. But the tobacco warehouse was the defining architectural form of these urban outposts. In the new and growing cities and towns of the region, their individual size and collective scope combined to dominate entire city blocks and dictate the plans of these cities (Bishir and Southern 1996: 43) (Fig. 1). The huge blocks encompassed in the flat, once-farmland of the east were dominated by brick or metal facades and “sweeping roofscapes [punctuated] by several thousand raised, rectangular skylights,” which allowed enough light to inspect the crops of tobacco piled in the warehouse (National Register of Historic Places, Wilson Central Business-Tobacco Warehouse Historic District, n.d.). By the early 20th century, most tobacco warehouses were large structures made of sturdy manufactured materials, though street facing elevations might have brick facades to give the appearance of human scale and integration into city streets. Especially in Rocky Mount, Wilson, Danville, and other tobacco towns, builders eschewed ornamentation in favour of efficiency and outright expression of function.

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

7 These early 20th-century warehouses, built throughout the Piedmont and inland Coastal Plain of North Carolina and Virginia, were remarkable for their size and utility. Most were framed with large timbers, had gabled or hipped tin roofs, and exterior facings of brick, corrugated metal, or whatever other industrially produced material was cheapest in the era they were built. These structures changed little in type from the 1900s to the 1950s, only becoming more utilitarian as they became commonplace. Few of the buildings rise above conventional industrial architectural idioms or possess stylistic flourishes that would attract the notice of onlookers or many architectural historians. But their size, ubiquity, and central downtown placement in numerous cities imprinted them on the lived experience of virtually everyone in the region from the start of their construction in the late 19th century.

8 Rocky Mount serves as an excellent encapsulation of these changes in the urban-industrial built environment of the brightleaf growing South. Its utilitarian buildings, though little documented, mirror the pattern of development throughout the region. After a slow start, Rocky Mount grew into perhaps the largest hub of tobacco sales in the state. Envious of the money being made in the older tobacco towns of Oxford and Henderson, “in the year 1887 a movement was set on foot...which resulted in the building of the first warehouse in Rocky Mount,” a 50 by 100 foot building (Rocky Mount 1906: 52.) Another warehouse was built in 1900, and several more followed in the next few years. Within a generation, there was an emerging architectural pattern for warehouses in Rocky Mount and beyond. Their first increase was in size. By 1906, the behemoth warehouse of 1887 described above “would look like a pigmy” by the side of the new warehouses in the city (52). An unpublished 1930s description of the composite warehouse landscape from nearby Durham details the next generation of innovations. The buildings grew even further— “a tobacco auction warehouse is an acre of floor, enclosed”—and mostly replaced the early dirt floors with oak plank ones (Tobacco Market—Durham) (Fig. 2). Among the very largest warehouses was the locally owned Mangum’s in Rocky Mount. When clear of tobacco bundles it boasted “a floor space of 300X400 feet” (June German Classic is Given For 52nd Consecutive Year, 1932). The structures remained functional and only infrequently adorned, with most dispensing even with the brick facades of earlier years in favour of quick, cheap, and durable corrugated metal or wood (Fig. 3).1 Larger, more cosmopolitan and economically diverse cities like Durham might sometimes build elaborately styled showcase warehouses, like the tobacco conglomerate Liggett and Meyers’ Smith Building or the Romanesque Revival warehouse of the British-based Imperial Tobacco (National Register of Historic Places, Smith Warehouse, n.d.) (Fig. 4).

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

9 But for Rocky Mount, the more utilitarian structures came to define the city both materially and symbolically. Local residents embraced the rustic nature of the structures as a marker of their own status, reveling in the disjuncture between their outward simplicity and the money that their interiors represented. Indeed, they emphasized the contents of the building far more than the rude facades, as in this postcard showing the expansive floor during an auction, or the many accounts of groups decorating to bring “interior beauty” to the working structures (Dances Here to Reach Peak in Annual German, 1928) (Fig. 5). According to one 1930s account, the typical structure had “wooden sides and a wooden roof, unfinished and unpainted inside, the outsides of corrugated iron, the roof, tarpaper and skylight glass.” The interiors of the building were lit chiefly by sunlight and the football-sized floor interrupted only by “about 125 eight by ten pine posts” supporting a shallow, gable front roof (Tobacco Market—Durham, n.d.). They were built in or near the centre of the town and in close proximity to its many converging railroad lines that were there largely in service of tobacco and the millions of pounds that filtered through the city’s warehouses, stemmeries, and factories. Here, tobacco was king, and African American people were again compelled to the service of a lucrative cash crop with little potential profit for themselves.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

Folklore, Performance, and Architectural Meaning

10 The preceding sketch of the architectural history of the tobacco warehouse is incomplete because of the absence of the people who made use of the structures. Conventional architectural history has made significant strides in accounting for the use of structures without centring that approach. Vernacular architecture scholars have gone a step further, building a documentary practice that prioritizes attention to the undervalued and unnoticed. A significant part of this practice comes from an accounting of the material modifications of a building through successive generations (Heath 2014). Prioritizing use value has become a hallmark of the field of vernacular architecture studies, but attention only to the visible material culture and modifications of a building carries its own absences. Actions, voices, and people also animate buildings, even when their presence in them is only temporary. Performance—with, in, and of a building—can help us better understand its evolving and adaptable meanings.

11 The remainder of this essay will reconstruct the performative uses of tobacco warehouses through an ethnographic approach to the built environment based on my own fieldwork and that of previous generations of folklorists. This approach views the past through an archive of buildings, experiences, and the ephemeral traces of use left behind. In this endeavour, I am building on the methodological intersections of North American vernacular architecture studies and folklife studies. Especially recently, folklore has most often been subsumed as merely one of the strains of a generalized interdisciplinary approach to vernacular architectural studies. In the decades since the founding of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, the organization and vernacular built environment studies more generally have emerged as a field with a particular set of practices, methods, and adherents. Part of vernacular architecture’s emergence as its own field has been the shunting off of many of its antecedents into prologue, rather than current practice. This has largely been the case with the performance studies framework pioneered in folklore. As Susan Garfinkel observes, the performance approach emerging from folklore is “simultaneously formative and underappreciated” (2006: 106). Garfinkel is noting a kind of genealogical distancing, where folklore and folklife methodologies are conceptualized as historically significant to the formation of the field, but are more rarely foregrounded in discussions of its present and future. This is a critical absence that both ignores the specific and ongoing contributions of folklore and folklife methodologies within the field, and reduces the scope of vernacular built environment studies. Folklore represents both a significant part of the past of the field and offers several possibilities for renewing its importance and vitality.

12 During the celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, Dell Upton pointed to the necessity of new approaches for what he saw as a stagnating field. He notes that the field as a whole “remains well within the genteel antiquarian tradition” (2006: 9). Our work and its focus on style, structure, and buildings themselves often overlooks the processes of use and the performative gestures inherent in human interactions with and in the built environment. Indeed, for Upton the impulse toward direct, in-person documentation of structures is a fetishization that “threatens to commit us to an unreflective empiricism that shuts off other possible avenues of inquiry” (9). It’s an overstatement surely, but it does point to some of the major problems with vernacular studies of the built environment that a more varied approach might help solve. A folklife approach is not a panacea, and I certainly do not mean to reflect on its historical usage within the field as constituting some interdisciplinary golden age for vernacular architectural studies. Rather, a folklore approach has been more about possibility and unrealized potential than about realized utility for studying buildings and landscapes. Folklore offers us the potential to animate buildings more fully with the voices of the people that use them.

13 Upton himself suggested as much in an early attempt to articulate a theoretical approach for understanding architecture through performance. In a 1979 essay in Folklore Forum, he focused on the potential of a structure to “have any real meaning to its builders and users” (178). He was building on the work of Henry Glassie who had earlier helped to give rise to the American vernacular architecture movement with his Folk Housing In Middle Virginia (1975). Glassie’s most meaningful contributions departed from previous work in vernacular architecture (mostly centred in Britain) and crucially, from the work of his own mentor, the cultural geographer Fred Kniffen. Instead, Glassie wrote in concert with other folklorists like Dell Hymes and Richard Bauman, then also reconsidering folklore approaches from ethnographic and sociolinguistic perspectives.2 What emerged—perhaps most fully in Glassie’s book—was an understanding that sought to depart from both the textual primacy of other fields and the cold empiricism of earlier structuralist theories. Glassie worked toward a more humane and nuanced systematic theorization, insisting that “different forms can be identical, but the meanings and uses different people associate with these forms can only be similar” (Glassie 1975: 21). In other words, meaning came through interaction, what we can identify now as performative usage.

14 This performative, ethnographic approach fundamentally transformed folklore as a field of study. It came amid what folklorist Michael Ann Williams called recently “a series of revolutions” (2017: 130). The embrace of folklife—of material culture, of food and other lifeways, of vernacular architecture—was simultaneous with this awakening of new approaches in other parts of the field. But folklore broadly, and its theories of performance more particularly, should still be central to an arena of study that is seemingly always poised to descend into the mire of stylistic detail and a crude determinism about its impact on human action. As folklorist Bernard Herman reminds us in his essay on performative approaches to vernacular architecture, “the ardent preoccupation with objects as singular statements” detracts from our ability to understand the material world as one composed of “plural [phenomena] modified by a series of creative acts across broad spans of time” (1985: 164). What folklore can do, then, is help us to enliven buildings, to document, and theorize the intangible and ephemeral, and to refocus our attention on the people making and using places.3

The Tobacco Warehouse at Work

15 Tobacco work was once so ubiquitous in eastern North Carolina that it went largely unremarked. As with many localized lifeways, its memory and traditions were recorded in detail by ethnographers intent on better understanding these worlds. Their close observations, and particularly the testimony of their narrators, give us insight into the smaller scale histories of the tobacco industry and help populate the monumental, monolithic structures that dominated the landscape and life of the region. It was principally in these warehouses and stemmeries that African Americans worked in Rocky Mount. In the warehouses, farmers, usually from the immediately proximate counties, would drop off their crop of cured tobacco for sale. Often lured in by large signs proclaiming the time of the next sale, the farmer pulled to the edge of the warehouse and was met there by a team of African American workers. Their job, day or night, was to unload the sheaves of tobacco and arrange them for sale on the floor of the warehouse (Biles 2007: 171). The labour was intensive, if irregular. Reuben O’Neal remembered his days working in warehouses in the 1930s and 40s as comprised of “mostly the floor type of work, nothing special” (personal communication, Reuben O’Neal to Beverly Jones, 1971). He might help unload, sweep the floors for remnants, or even pick the mold out of unsold piles for later resale. Whatever the work, it was barely remunerative despite its intensive schedule. During the season, he remembered, “for 2-3 months we’d work every Sunday, we’d work every day of the week.” O’Neal went on to note that even working seven day weeks, “it just about taken everything you make to live on.” These new types and places of employment still recreated the old forms of racial inequality that people like O’Neal fled from in the countryside.

16 Because of the on-call nature of the work, the warehouses even served as de facto living quarters. As the blues musician Thomas Burt recalled, the warehouses “had places upstairs with bunks, mattresses all over the floor. They had a night watchman and a fellow to keep fires going upstairs” (personal communication, Thomas Burt to Glenn Hinson, 1979). There were separate, segregated bunkrooms for Black workers and the white farmers who brought their crops to town. But staying in the quarters a night or two was far different from actually living there. Workers were tasked with keeping the stove burning and staying prepared for the next loads of tobacco coming in. The work was steady enough that it was easier to live and work in the same place, as Parson Barnes testified when he mentioned that he had “moved up here in the warehouse at Christmas,” shortly after beginning work there. The bunk rooms offered little respite for workers on call (personal communication, Parson Barnes to Leonard Rapport 1936). Even when the work was not around the clock, these warehouses became homes for a large number of labourers, waiting for the work to pick back up with daylight.

17 A description from the 1930s describes the process of that work. “From the head-high stacks of baskets at one side of the warehouse—shallow, round-cornered baskets, a yard square, of tough oak strips—the Negroes bring half a dozen. The tobacco is in sheaves of twenty or thirty leaves, wrapped with a leaf at the stem end, and hung on a four foot stick, about twenty-five sheaves to the stick” (Tobacco Market—Durham n.d.). Eventually, these individual piles of tobacco covered nearly every square foot of the warehouse floor, leaving just enough room for auctioneers and their trailing customers to navigate as the tobacco was sold in minute-long bursts. After the auction, the same Black men who had unloaded and arranged the tobacco transported it from the warehouse to nearby “stemmeries” or “prizeries.”4

18 Each of these stemmeries was staffed almost exclusively by African American women, a division of labour that was entirely by design. Stemming was piecework, paid by the pound. It required swift, powerful motions, splitting each leaf almost in two but leaving “the little part of the stem in the leaf,” as Estelle Hodges recounted of her days working in tobacco (personal communication, Estelle Hodges to Glenn Hinson, 1979). Women would stack stems on large tables, working next to two or three others, and pile up their finished tobacco into big bundles to be picked up by men employed for this purpose (personal communication, Hallie Caesar to Glenn Hinson, 1979). The pay here was scarce: anywhere from eight to twelve cents per pound of the lightweight, desiccated stems.5 This was a miserable wage, exacerbated by the horrendous working conditions of these factories. Motivated by a prevailing belief “that sunlight and fresh air would dry out the tobacco, white supervisors in stemmeries closed and covered windows” (Biles 2007: 185). Like other industrial work spaces in North Carolina, stemmeries were hot, dusty, and cramped, without even the promise of year round work to make it seem worthwhile.6 Men were not allowed to do the stemming work because they could generally do it even more quickly and thereby earn far more than the usual subsistence wage. Instead, they were likely to be employed at any of a variety of jobs where they were designed to be replaceable.

19 Indeed, all of the industrial tasks of the tobacco industry were designed to function without the benefit of “skilled labour” and to be replaceable at a moment’s notice. Because the work was largely seasonal, it meant that African American people in Rocky Mount were often without work for much of the year. Piecing together off-season labour in a town with one major industry and few employers was a near impossibility. This meant that some Black workers, especially men, were mobile. As Hazirjian explains, “men often went north for the spring and early summer in search of construction work or other manual labour, then returned for the tobacco season and stayed on in Rocky Mount until the northern frost broke” (2003: 48).

20 This helped deepen ties between this small Southern city and the industrial North, where increasing numbers of family members and friends were settling semi-permanently. Never a one way street, the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to more northern industrial centres saw cultural and geographic ties to Southern homelands persist amid supposedly permanent moves.7 This sense of flux and mobility was the motive force underlying these migrations and remigrations. At home in the south, African Americans found other ways to negotiate and even appropriate spaces marked as white. The tobacco warehouse, as the most visible symbol of the tobacco industry, represented a class and working culture otherwise closed to African American men and women. Whites were certainly also subject to selectively low wages and often were among the tenant farmers who suffered tremendously when prices fell or crops failed. However, tobacco was also a powerful economic force that transformed a moribund agricultural region of former plantations and smallholdings into a profitable centre of commodity agriculture. It was the rise of tobacco, more than anything else that created a large, southern, white middle class for the first time, and it simultaneously cast both Black farmers and Black urban labourers as a kind of permanent economic underclass, forever subject to whims both human and environmental.

21 As a symbol, then, the tobacco warehouse represented the foreclosure of a middle-class existence to African Americans. As a built structure, it likewise removed much of the possibility of creating African-American spaces for anything other than menial work. Because tobacco warehouses were both so ubiquitous and so monumental, they were the central secular buildings of Rocky Mount and other tobacco towns like it. The pride that groups like Rocky Mount’s elite society, the all-white Carolina Cotillion Club, took in decorating what were in effect oversized barns, nods to their understanding of the centrality of these structures to their livelihoods. Their repurposing of these structures for a formal dance was done with both a wink at the absurdity of the “city [that] sheds her working garb to dispense hospitality,” but also a genuine pride in the utilitarian structures that represented so much accumulating capital (June German 1941). For African Americans, this kind of repurposing had a far different meaning.

The Tobacco Warehouse at Play

22 The tobacco warehouses were highly adaptable buildings. Particularly during the summer months when they were vacant, they served as the centre of civic and recreational life in Rocky Mount and other tobacco towns.8 Most often, this ephemeral transformation of the building and its purpose was in service of white organizations and institutions, but through the efforts of a variety of African American people in Rocky Mount, the warehouses too became a venue for the expression of a liberatory Black sense of place.9

23 Building owners were eager to make good use of the cavernous spaces of the warehouse throughout the year. This meant renting buildings for events and entertainment which often only emphasized the exclusive nature of the structures. For instance, in 1926 a large regional Ku Klux Klan meeting “assembled at two local warehouses ... secured for that purpose,” before parading through downtown Rocky Mount (Klan Meeting is Slated for City 1926). The most frequent—and famous—repurposing of the warehouses, however, was for a summer dance dubbed the “June German.” Named for a particularly elaborate dance formation, the June German began nearly simultaneously with the construction of the warehouses in the 1880s. It was organized from its inception by the all-white Carolina Cotillion Club (CCC) (Cotillion Club Organizers Tell of First German Here 1928). Under the direction of this club, the June German went from a local society event to one seeking notoriety and profitability. The CCC “realized that money was to be made by turning scenery and properties of their dance over to Negroes for a Colored June German” (Spellman 1939: 17). They did just that, leasing their warehouse space and decorations from the all night Friday dance for a Monday evening affair in the Black community.

24 Under the direction of some ambitious promoters, this new event was turned into “a commercialized edition of the white invitational affair” by eschewing local talent to bring in nationally known “ ‘name bands’ ” (Spellman 1939: 17). In just a few years a band’s selection to play the so-called “Colored June German” became a marker of particular prestige. It signalled, as newspaper articles reported every year, that the performers in question were the most nationally popular band of the year (Buddy Johnson to Play June German 1949). Bands like Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, Andy Kirk, Roy Elridge, and the International Sweethearts of Rhythm all played the dance.10 As it grew in both size and reputation, those outsiders visiting the dance came from cities all along the eastern half of the United States by the thousands or even tens of thousands. The June German became, in the words of Norfolk’s Journal and Guide, “not just an ordinary dance but also a reunion of thousands of friends” (Andy Kirk to Play June German Dance 1943).

25 As revellers arrived to Rocky Mount by train, bus, or car, they quickly moved toward Douglas Block, the central Black business district for the city. Taxis may have shuttled people to the distinctly segregated areas around town to visit family and friends, but the terminus point for every year’s June German was within two blocks of the centre around which African-American life in Rocky Mount, and indeed much of Eastern North Carolina, revolved. Douglas Block was a geographic marker for Black people looking to orient themselves in Rocky Mount. In the early years advertising the June German, when it was still growing beyond a regional event, the location of the dance was marked as “opposite Douglas Corner” so that prospective visitors had a landmark to find their way to an unfamiliar structure (Frank Lewis Presents Jimmie Lunceford 1938). These locations were not selected by the promoters of the African-American dances, but rather the all-white CCC. For this committee, the utilitarian tobacco warehouses represented a kind of studied contrast with the splendor of the decorations for the June German and the strictly formal dress code. But for African Americans, it meant that the centre of the social calendar of North Carolina was squarely within the most visible Black neighbourhood in the city.

26 Many promotions for the Black June German emphasize the fact of this centrality and visibility. One 1935 advertisement calls the Douglas-Armstrong Drug Store on “corner, main and Thomas sts.” the “June German Headquarters” (Classified Advertisements 1935). Indeed, Douglas-Armstrong was an anchor not only of the block but of the June German experience. It was one of the businesses that stayed open throughout the evening, a place where you could “enjoy Gar-O-Ler ice cream” or a sandwich to fuel a night of dancing and drinking (1935). It was also a place, along with the Center Theater Smoke Shop (located a little over a quarter of a mile away in the heart of downtown), that people could buy tickets for the June German (The Original Colored June German 1938). The theater was decidedly not in Douglas Block and its location as a destination for ticket sales seems intentional. The advertisements for these tickets appeared in the white-run Evening Telegram and clearly spoke to both white and Black consumers. The latter would purchase their tickets in Douglas Block, the former only in downtown. There was certainly a difference between attending to business at a place adjacent to Douglas Block, where many of the town’s biggest tobacco warehouses were. In fact, every one of the warehouses used for a June German was within a block or two of this central Black business district. For African-American dancers, this must have seemed like a serendipity that heightened their own sense of celebration on a night when the town became decidedly and definitively Black. For white people—either as spectators at the “Colored June German” or as dancers at Friday night’s white German—being in this part of town and celebrating in the warehouses was a step removed from their usual inhabitation of the city. Still, these spatial and social boundaries were transgressed frequently, motivated alike by a white investment in Black bodily pleasure and the geographic necessities of small-town life. These kinds of proximate intimacies created a challenge to the easy contours of spatial segregation and informed a performance of the June German that increasingly represented the celebration of everyday Black pleasure.

27 This was heightened in particular by the spatial politics of the dancefloor within the warehouse itself. Each year’s decorations were increasingly elaborate variations on similar themes. Descriptions by Black newspapers tended to highlight the otherworldly characteristics of the transformed tobacco warehouse. By far the most utilized descriptor was “fairyland” or “fairy-like.” The local, white-run Telegram tended to be more specific in describing the individual themes of the decorations. One year’s adornments had “the general effect ... of an English garden” (Workers Putting Warehouse Into Shape for June German 1931). Other years recreated “a peach orchard in blossom time,” or festooned the warehouse with “thousands of miles of white streamers” with a massive white canopy overhead and “side walls treated in replica of out of door cafes, such as one sees in European countries” (Final Plans Completed Today for Annual June German Here 1928). Another recurrent motif saw the English garden theme of ivy, laurels, and picket fencing made more local by a row of “North Carolina’s long leaf pines ... to wall off the dance floor” (Thousands of Visitors Praise Cotillion Club Entertainment 1931). These decorations all evoked a particular kind of nostalgia, one that pulled from a romanticized past and foregrounded the translation of European cultures to American landscapes. These were familiar evocations not necessarily of the particular eras they invoked, but rather of the recreative grandeur of the plantation landscape which likewise called on these antiquarian pasts. The logic of these decorations was filtered through that mindset, commonplace still in the 20th-century South. The decorations then served to reify the spatial segregation of the warehouse. It is telling that white newspapers focused their descriptions of the buildings on specific, terrestrial references, while African-American writers imagined an otherworldly fairyland. It points to the ways in which each imagined this place and its potential. One was grounded clearly in historic referents, the other pictured a world fully apart from the one they inhabited.

28 As the dances continued to grow in size and prominence, they attracted an audience. The massive dancefloors were increasingly ringed by spectators whose reduced admission fees helped pay for the big bands. Starting as early as the late 1920s, the so-called Colored June German was perceived as an attraction for white spectators. A 1932 article, the first mention of the event in any Rocky Mount newspaper, was centred on “ample provisions ... made for white people to see the dance” (Thigpen 1937). The article suggests that this was a fairly common practice and that “as in previous years, it is expected that a large number of white spectators will be present” (Negro June German Planned for Monday June 27, 1932). In equally large letters one year were the sponsoring organization’s name and a promise of a special section for the white audience: “Sponsored by the Rhythm Club Reserved Seats for White Spectators” (Fig. 6). Presumably in response to crowded conditions in years past, a 1942 ad promised “More Seats, More Room, More Comfort for Spectators” (World’s Largest Negro Dance 1947). The reverse was never true throughout the many decades of the white June German dance. Like other segregated Jim Crow institutions (and like the workaday tobacco warehouses), the only African American people allowed at the all-white dances would have been those working.

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

29 In effect, the Black June German advertised a segregated experience, one that allowed whites to view the bands and dancers without actually interacting in any meaningful way. It promised a voyeurism of a sort. Regarding this from a scholarly framework, it seems little more than yet another accommodation Black people had to make to the spatial and social inequalities of Jim Crow. But African-American attendees recall a different meaning of the building that stemmed from their dancing in, and being part of, the event in the transformed warehouses. The saxophonist Maceo Parker grew up in nearby Kinston and recalls the means by which June Germans and other shows held in tobacco warehouses were segregated:

But they would have a rope, like a big, thick rope like maybe from a ship or something [laughs], and have it in the center of the stage, down the thing, and then all the way to the back. They’d have Black people on one side, white people on the other side.

And I, you know, remember as a kid saying, “I don’t understand this. What’s the difference in the rope? I don’t understand.” And then, you know, like this. [Demonstrates] This is the stage, and the rope is like this, all the way back, and then you’ve got white people over here, Black people over here. ... You know what I mean? And you’re listening at the same time. (Personal communication, Maceo Parker to Sarah Bryan, 2007)

30 Parker here is commenting on the absurdity of this particular form of discrimination, a kind of sonic segregation. People were clearly hearing the same music, but had a markedly different experience of the event. Though the move toward accommodation for white spectators was largely advertised as an attraction, it ended up functioning as a performative critique of the means of segregation, as well as its ideology. In that sense, these dances acted as a direct critique of the system of segregation and performed a kind of alternative to it through gathering, celebrating, and dancing in an otherwise strictly restricted pace. Journalist A. A. Morisey noted that the dance inverted the social position of the South for an evening, forcing “those who normally usurp the superior facilities,” to “sit and watch while Negroes enjoy ... complete freedom” (1948). Freedom for Morisey and the other dance attendees was measured in unfettered access to the warehouse, its selling room turned dancefloor, its bathrooms, and any of its entrances. Freedom was using the place as their own.

31 The June German was not just another dance. Commentators at the time and subsequently insisted on that fact. A woman I talked to remembered going to the June German year after year when she was young. She lamented its passing amid the other changes in Rocky Mount, but mostly she remembered the fun she had in this place transformed for the night. “We just danced! We didn’t eat and drink, we just danced. We just danced and danced all night long” (Mrs. Travathan, personal communication, 2017).11 This, she suggested when I pressed her further, was the point: to be in that place, with so many other Black people, fully enjoying themselves for one evening. Their ability to revel in the space and take pleasure from a place built to extract labour is a fitting example of the performative undermining of the architecture of Jim Crow.

Conclusion

32 The tobacco warehouse was truly a structure of potential and imagination. The importance of the building was as a conceptual repository for the longings of its temporary occupants. White farmers could dream of their profits and the economic security it might buy them, Black workers could dream of steady wages and a life apart from the hardships of farming in the countryside, and Black dancers could imagine themselves in a different, perhaps nonexistent place. Each of these stemmed from a performed relationship with the building itself. In present day, most tobacco warehouses are largely shells, literal repositories for human-centred notions of social and economic value. Now, with most warehouses standing emptied or no longer extant, their functions become even more about the imagined and projected. The enlivening of a building with its performed uses should be central to our task as scholars of the vernacular built environment. We have held principles of utility and ubiquity highly, and a recommitment to the tools of folklore helps us build on that basis and on the human-scale stories of the buildings we study. As scholars of the built environment, we often invoke an aphorism to students and colleagues: buildings have stories. But we should say what we really mean, that buildings contain stories that people hold. To do a better job studying buildings, we have to rely on the narratives of people that lived, worked, and played in them.