Research Report / Rapport de Recherche

Anna Dawson Harrington’s Landscape Drawings and Letters:

Interweaving the Visual and Textual Spaces of an Autobiography

1 In biographies of esteemed members of her family, Anna Dawson Harrington (1851-1917) is described as the helpful eldest daughter of John William Dawson (1820–1899), geologist and first principal of McGill University, the devoted wife of Bernard James Harrington (1848–1907), McGill professor in mining and chemistry, and the caring sister of George Mercer Dawson (1865–1901), scientist and surveyor (Michel 2003: 174–84; Michel 1992: 33–53; Ouellet 2003; Sheets-Pyenson 1996; Winslow-Spragge 1993). As mother of nine children, her homemaking skills are well documented in “Health Matters: The Dawson and Harrington Families at Home,” a perceptive architectural analysis, by Annmarie Adams and Peter Gossage (2010), of the ways Anna arranged and experienced the interior spaces of her home to manage her children’s health, especially the health of her son Eric, who died of tuberculosis in 1894. In his introduction to Anna’s unpublished memoir of her father, Robert Michel writes that she “illustrated many of his geological books and articles, assisting in many ways until her father’s death.... She inherited her father’s intelligence and spiritual and rational attributes yet, like many educated women, she had to spend most of her energy looking after her family. A few generations later, she might have become a scientist herself” (2003: 180).

2 The objective of this study of a Canadian Victorian woman is to understand the relationship between material landscape and identity through the evidence found in her drawings and the letters she wrote to her husband Bernard. The drawings are mainly watercolour landscapes that span a period of forty-five years, from 1869 to 1914.1 Housed at the McCord Museum, they depict numerous scenes of Little Metis, Quebec, on the lower Saint Lawrence River, where Anna and her growing family spent their summers while Bernard was often in Montreal working at McGill or engaged in fieldwork in other parts of Canada or in England. Since Bernard was away so much of the time, the majority of Anna’s letters were written from Little Metis, though a few of interest were written from the family home in Montreal and from Saint Andrews, Quebec, where Anna’s father-in-law had an estate. She also wrote from other places she visited such as Kinsey Falls in Quebec, Toronto and London in Ontario, and from her travels while visiting the United States and England. Anna’s letters are carefully preserved in the McGill University Archives.2

3 Informing this investigation is the notion that autobiography and landscape can be so intricately entwined that they constitute a single self-narrative (Edwards 2009: 297–315; Egan 1996: 166–88; Finley 1988: 549–72). This means that the material forms of the landscape when sensually and thoughtfully experienced by a person can become imbued with autobiographical meaning (Tilley 2006; 2010). Tilley defines the relation of landscape and identity this way: “When people think about social or cultural, or their individual, identity, they inevitably place it, put it in a setting, imagine it and feel it in a place. Ideas and feelings about identity are inevitably located in the specificities of familiar places together creating landscapes and how it feels to be there” (2004: 25). As such, to say that the materiality of landscape is autobiography assumes that Anna’s drawings are uniquely connected to her identity and to what she wanted to convey about her thoughts, feelings, and values. The fact that Anna titled and dated each landscape drawing and stored them protectively indicates her desire to preserve and reveal what mattered most to her as defined by what she saw. Thus, Anna’s drawings are the infrastructure of her autobiographical project perceived by her and then transformed into art to illuminate and encapsulate her life.

4 However, a collection of drawings cannot alone function as an autobiography. Anna’s letters to her husband are significant in that they help to communicate what she is trying to say through visual imagery. While her landscape drawings can be regarded as the core of her self-expression, the narrative frame of the written word renders the mental geography of her visual representations comprehensible. As Kim L. Worthington explains in Self as Narrative (1996), individuality involves constructing a “narrative of the self ” that is embedded in community, and hence in language: “Selves are already always in community, and cannot simply choose or contract to enter the social context in which they have meaningful being…. Personhood is always embedded in the social (and, significantly, linguistic) context in which one has meaningful being; selves are constituted in and by a society and that society’s history” (1996: 56).

5 Anna’s letters to her husband recount not only daily events, but also impressions, ideas, and beliefs. Her emblematic passages concerning family and communal attachments affirm her “relational autonomy,” a concept of personhood introduced by feminist scholars in the research literature of the past fifteen years. In a shift away from the familiar duality of “self” and “other,” the self in feminist thought has been redefined as a consciously social and historical being who evolves through interconnections with people (Friedman 2003; Mackenzie and Stoljar 2000; Meyers 1997; Stanley 1992; Whitbeck 1989: 51–76). This was certainly the case in the Victorian period, as Linda Peterson (1999) explains in Traditions of Victorian Women’s Autobiography: The Poetics and Politics of Life Writing. At a time when women were expected to situate themselves within the domestic space of family and home rather than follow the masculine ideal of individualism and self-determination, women’s writings stressed the ethics of interrelations.

6 In Victorian society letter writing was a private activity viewed to be an accurate reflection of a woman’s character and critical to the formation of female identity (Amigoni 2005: 1–18; Mahoney 2003: 411–23; Nestor 2010: 18–35). At a time when letters were the only means of communication between people who were separated geographically, women were expected to be the family’s principal letter writers. Working within the framework of good manners, refined taste, courtesy and correctness, women were encouraged to write “lovingly” to absent family and friends, to be thoughtful in their compositions, and to express their emotions. The purpose was to produce letters that engaged their recipients by being conversational in tone while conveying information, answering inquiries, posing questions and generally exciting interest. In essence, the etiquette of letter writing offered women the opportunity to create content that was autobiographical in nature.

7 Because I am interested in exploring how autobiography can be represented through the material medium of landscape, I have interrelated two genres not usually considered together: the visual space of landscape and the textual space of letter writing. My starting point was to pair the feminist concept of relational autonomy with a recent examination of its relevance to artistic autonomy. Lambert Zuidervaart, a specialist in social philosophy and the philosophy of art, uses the idea of relational autonomy to explain how 1) interpersonal, 2) societal, and 3) internal autonomy are closely interlinked with the autonomy of the artist (2015: 235–46). In my interpretation of relational autonomy, which couples images and language, I have organized my analysis according to Zuidervaart’s three-part schema.

Interpersonal Autonomy

8 Interpersonal autonomy means that a person’s agency is formed through interactions with others. With this in mind, the places Anna depicts in her drawings can be studied in terms of her connections with the people in her life. Simultaneously, her individuality comes from assimilating these experiences of people and places into images that interpret what she sees. For Anna, the landscape is the infrastructure both for participating in interpersonal relations and expressing her preoccupations and reactions. The special nature of this duality appears in her everyday pictures of Le Metis, where memories of personal and communal events intertwine. Anna writes: “Today Eva, Kate and I went down to the beach ... bye and bye I deserted and wandered off into the nearest woods and found some beautiful cedar which now adorns my room. I also took observations with regard to a certain clump of trees, which I hope soon to sketch” (July 1877).

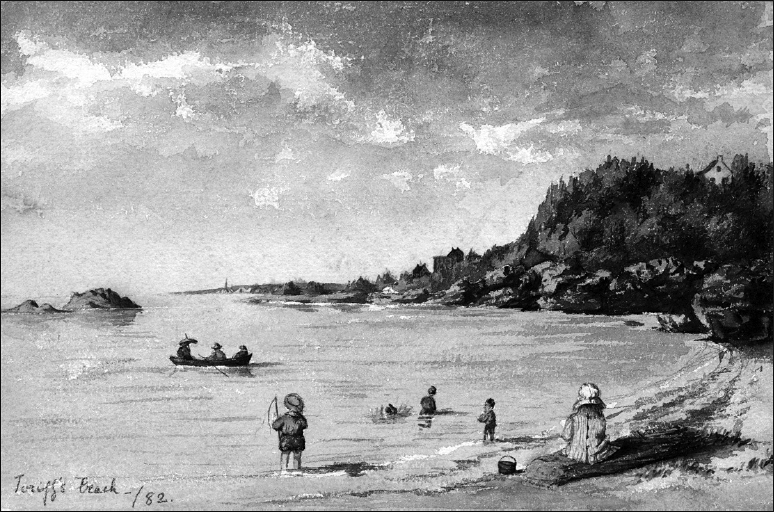

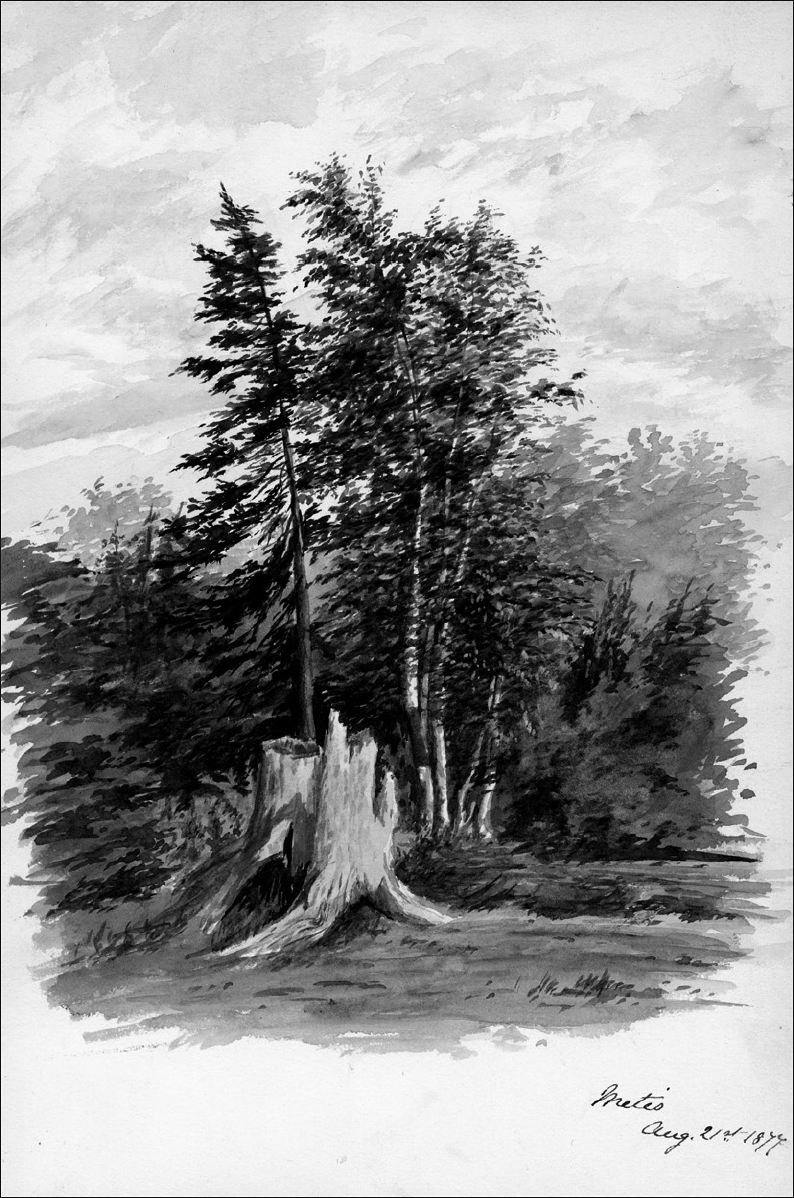

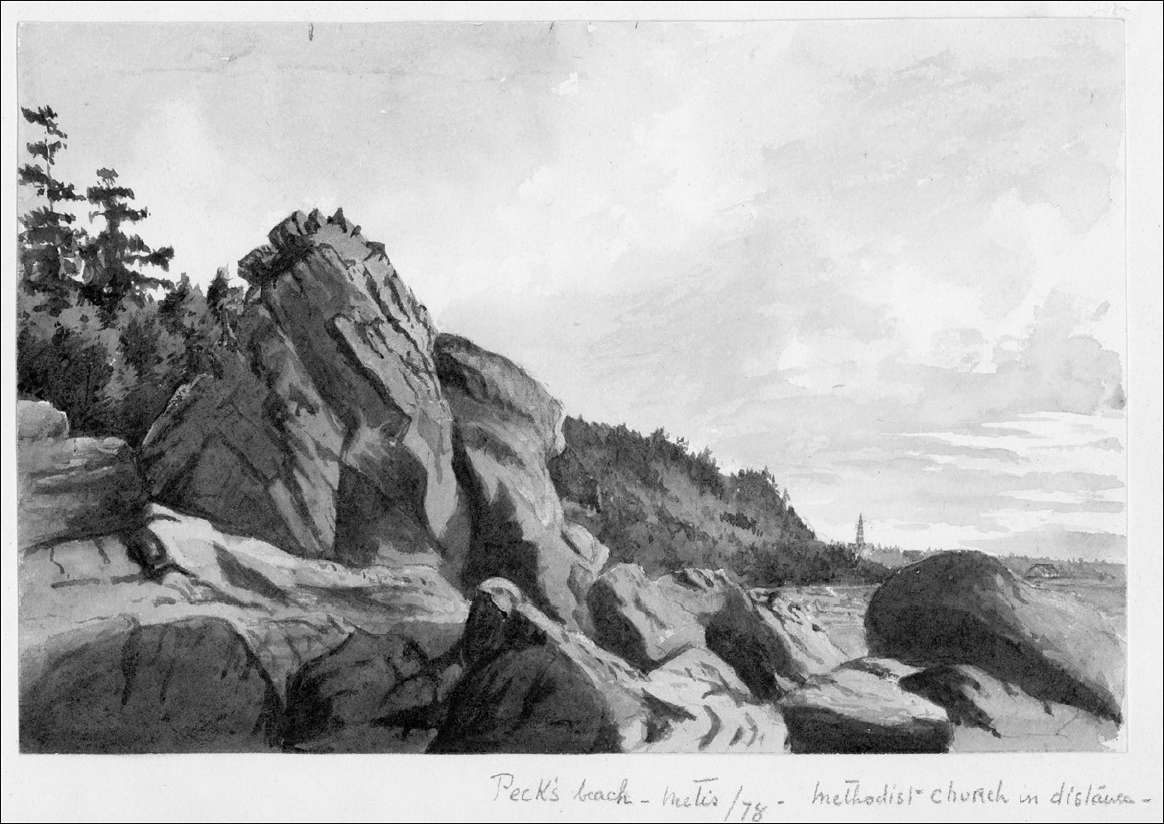

9 Anna’s drawings express the inner quiet she felt in relation to the people around her, a feeling that evidently existed in harmony with the natural landscape they occupied. This was Anna’s emotional relationship with landscape as sensuous material form in how she inhabited the landscape with her friends and family. Frequently she drew small human figures dwarfed by the magnitude of the land, sea or sky (Fig. 1). They often appear to be absorbed in contemplating the surrounding scene. Other compositions that strike a more solitary note suggest a close-up viewing of the scenery and betray the artist’s intense observation of the forms and surfaces of things (Fig. 2).

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 1

Display large image of Figure 2

Display large image of Figure 2

10 In this narration Anna is not only the “I” who envisions the here and now but also the “I” who recalls the places she experienced during her own childhood when she revisits them with her young children. In August 1878 she writes to her husband, “Yesterday we had a perfect sea-side, cool clear fresh and full of sea-savour. I was on the shore all the morning as usual, and had several little walks up and down the rocks with mamma and Mrs. Wilson. The baby was as good as usual playing in the sand, paddling a little rain pool on a rock, and climbing over a prostrate log with unwearied energy.” In the drawings of her children at play in the meadows, forests and rivers she frequented as a child, Anna evokes not only her special bond with the natural environment but memories of herself in that landscape.

11 Indeed, Anna is intent on imparting to her children her multiple readings of and relationships with the places they visit together. For example, we learn that she feels she needs to explain to her young son what she sees and draws: “I began a sketch yesterday of a sort of bog-hole, which I am sure would astonish the eye of the uninitiated, but it may turn out to be pretty. Having to explain everything to Eric while I worked used up nearly all my time...” (July 1882). In these two sentences she reveals her interest in training her eye to see the world more clearly and her maternal obligation to teach her son to discern the analogies between sight and representation.

12 While landscape drawing for Anna is self-reflective and self-directed, it is a shared value in that it is formed and nurtured through relationships with others. In her letters she frequently tells her husband not only the time period she is engaged in a particular drawing, but whether or not she is drawing with friends or teaching them to draw, and if the children are present and are making pictures too. Here are a few examples: “Sketching meets with Eric’s warmest approval.... It is wonderful to see how closely he observes and how accurately he remembers...” (June 1882); “Janie and I are bent on sketching...” (September 1 1882); “Miss Gardner, who I find is making great efforts to sketch, I am going to take in tow, and try to do a little myself by the way...” (July 9 1898). For Anna, the material character of the landscape constituted fundamental social values and identities. With this sensibility she characterized landscape as the site of communal experience and drawing as fundamental to the visual expression of these experiences.

Societal Autonomy

13 The second part of relational autonomy is societal autonomy, which is to say that being a person is to be socially and culturally formed, able to participate with a blend of independence and interdependence in the multidimensional character of society. A society’s character is defined by the norms and ideals that are upheld by its members and the social relations and practices in which they participate. In good measure Anna’s social and cultural formation was an outgrowth of her education. She learned to draw in an era when such learning was fundamental to the upbringing of young women.3 We can discern from the archival records of school attendance and prizes that she took drawing lessons in 1861 and 1862 with Mrs. Tate and Miss Tate at the Establishment for the Education of Young Ladies, and again in 1863 at Mrs. Simpson’s Ladies School.4 She continued to take art courses until 1867, when she was awarded the first prize for drawing at the Midsummer Examination. By 1875 she was devoted solely to art making, and writing to her fiancé Bernard that she “must be off to the Art School.”

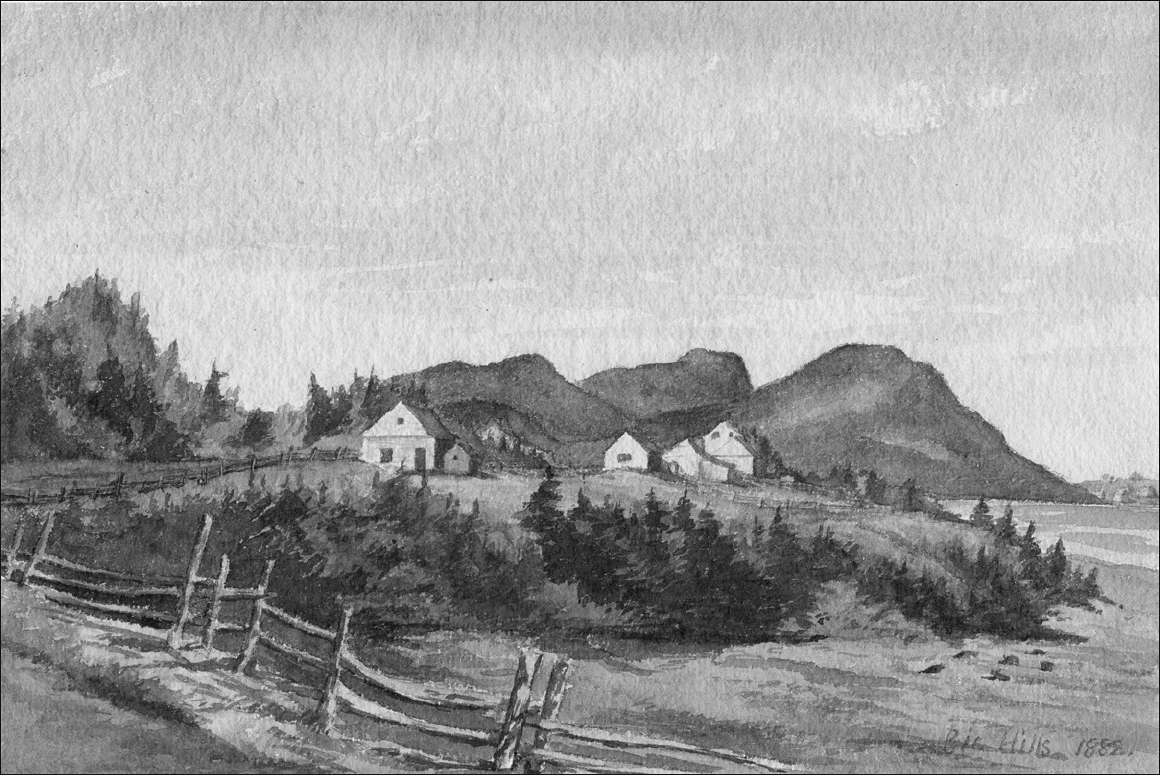

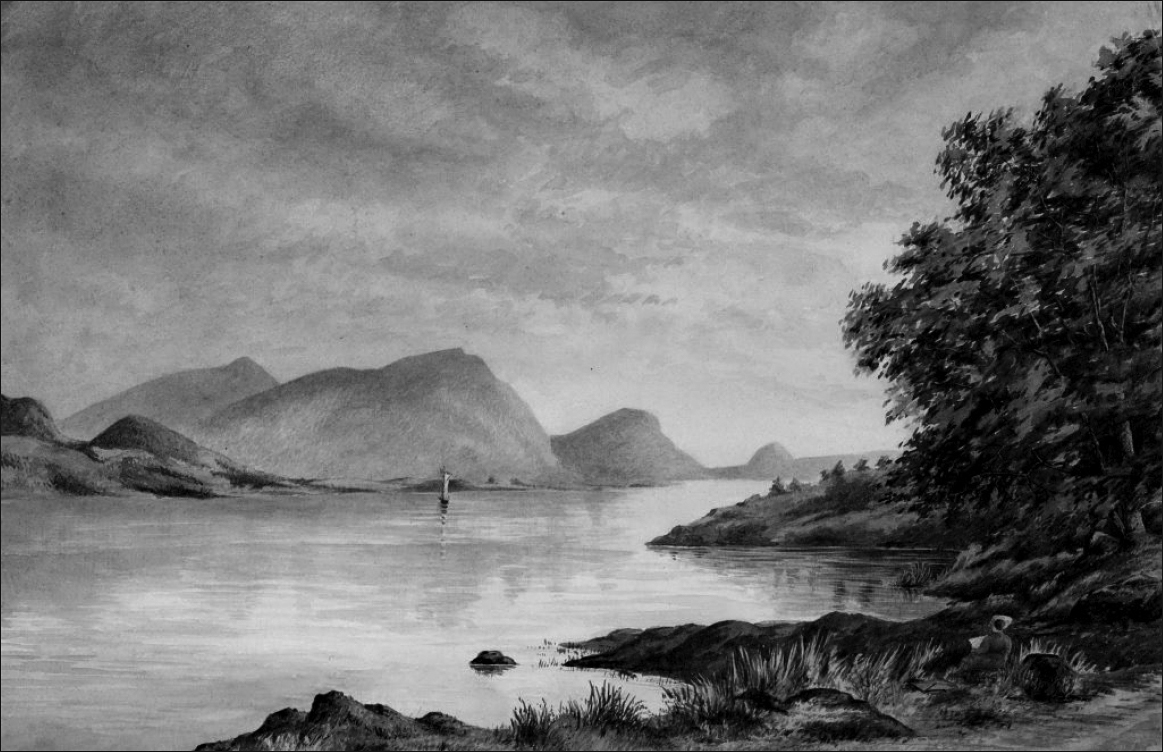

14 Landscape drawing, which involved an intense visual comprehension of the forms and surfaces of nature, was thought to foster moral vision, well-being, and an awareness of the relationship between the personal, the social, and the spiritual. The well-known British poets Milton and Tennyson, who Anna refers to in her letters, believed in the personal and social relevance of art and in a spirituality rooted in the physiology of nature.5 For Milton in particular, good citizenship and social responsibility depended on a harmonious relationship with rural culture and the natural world, as well as on peaceful states brought about by meditating on nature. Anna gives visual imagery to Milton’s pastoral ideal in charming, pleasingly peaceful drawings of rivers, fields, and mountains (Fig. 3), and her letters reveal a belief similar to his, for example, when she writes: “I wish you could be out here too and rest while the frogs sing, and the beautiful stars shine so serenely—God seems so near in the country, and everything is so lovely—I must try and take in all the beauty and restfulness, till I can carry an atmosphere of peace back to you.” We can imagine that with the stanzas of poems such as Milton’s L’Allegro (1875) as her guide— “Mountains on whose barren breast/The labouring clouds do often rest.... Shallow brooks and rivers wide”—Anna chose to reconfigure these sentiments in the landforms of rural Quebec.

Display large image of Figure 3

Display large image of Figure 3

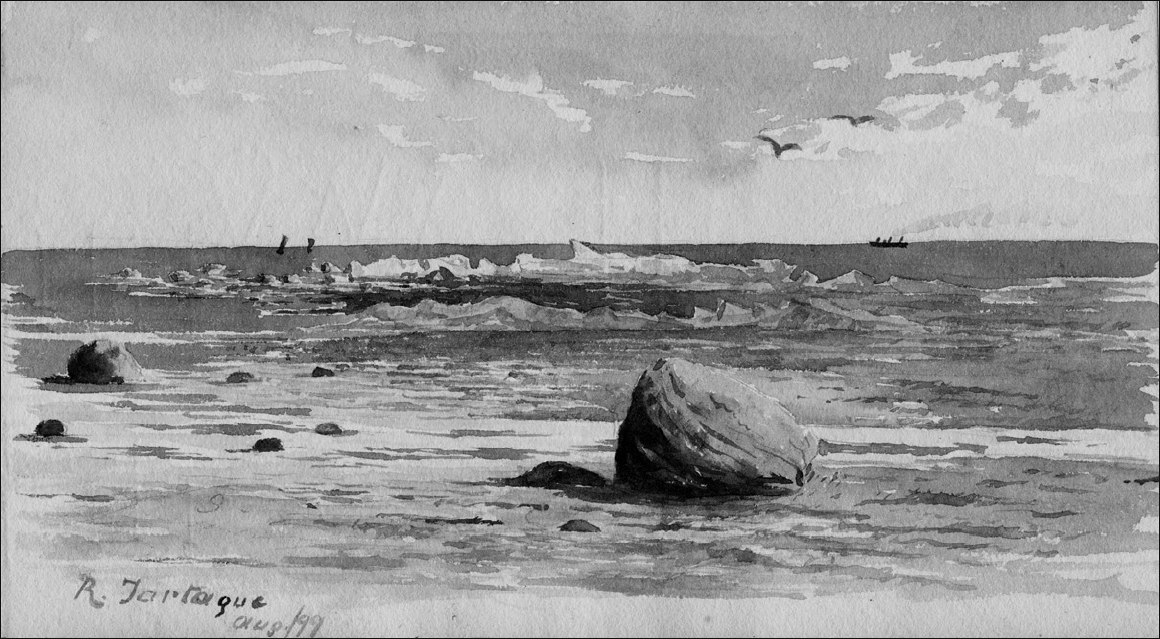

15 Tennyson, who explored interior landscapes and psychological spaces, is likewise suggested in Anna’s drawings. These are her landscapes of isolated locations, sea and shore, sunrises and sunsets, and views of the horizon that mirror the recurrent forms Tennyson uses to give expression to states of human consciousness (Fig. 4). Occasionally Anna writes about how her imagination can turn natural appearances into supernatural revelations:

Display large image of Figure 4

Display large image of Figure 4

16 This description reflects the human and transcendent qualities found in Tennyson’s poetry and in her drawings, where the world is intimate and real, yet distant and unknowable.

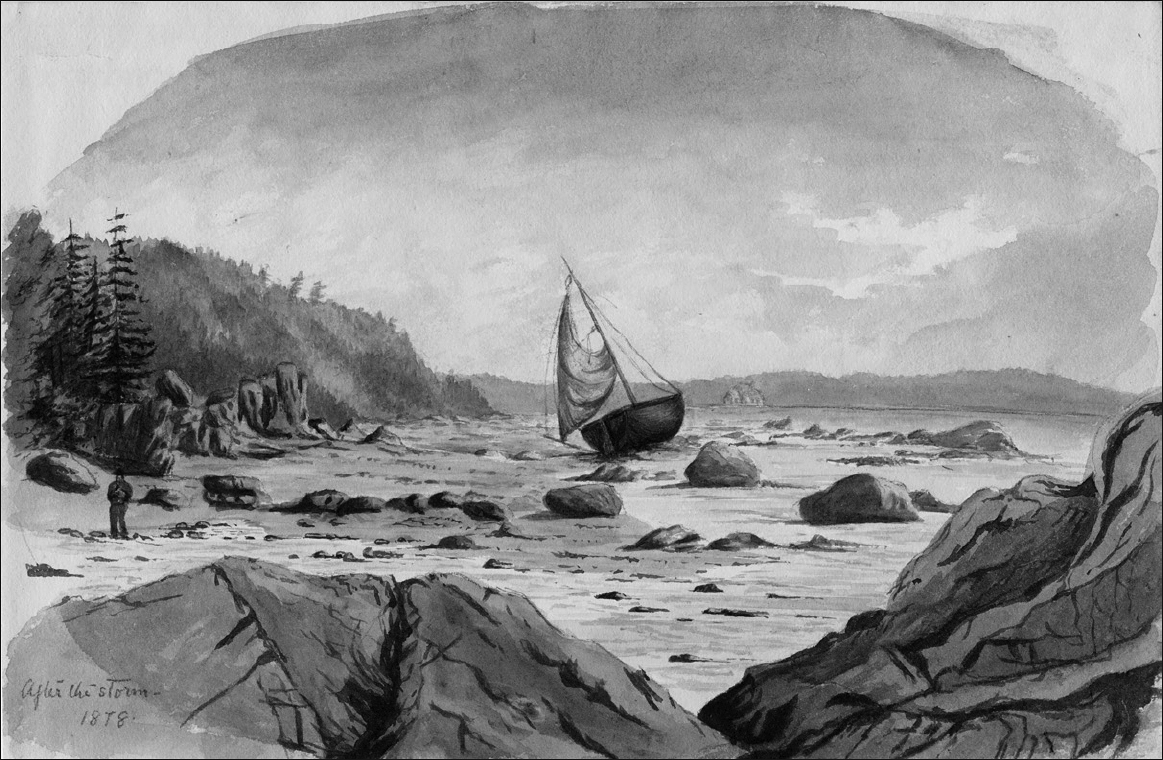

17 The strong spiritual quality of Anna’s landscapes is made legible through the thoughts and emotions that emerge in her letters.6 For instance, she writes in detail about a dreadful storm that occurred in 1878 on July 21. But rather than depict the struggles of the men as they tried to bring their schooners ashore, she captures its aftermath in a drawing of a small boat: “the oars were gone, and the upper part of the boat broken a bit... the helpless craft was rolled and tossed and mumbled by the waves, till it was finally tossed up on the shore....” In After the Storm (Fig. 5), Anna places the broken boat in the centre of the composition, revealing the attention she pays to its loneliness. The boat was powerless against the storm’s strength, yet managed to survive.

Display large image of Figure 5

Display large image of Figure 5

18 Through this picture, which is dominated by an expanse of foggy sky, reminding us of human frailty, distress, and submission, Anna transforms a descriptive text into symbolic awareness. It is “something quite out of the ordinary” (July 1878) she writes to her husband about this drawing, which connotes a personal and philosophical identity that is consistent with her spiritual view of herself and life.

19 Anna was a product of her time, affected by numerous social and symbolic constructions of the landscape. When she writes to Bernard that she “took observations with regard to a certain clump of trees, which I hope soon to sketch,” she acknowledges an interest she had in common with her geologist father and the many landscape painters whose enthusiastic study of geology led to a new language of landscape that evoked spiritual, ethical, and philosophical ideas (Bedell 2001). In asking “why people don’t sing hymns” upon experiencing a “wonderful sunset ... with glowing sky,” she not only affirms the love of music she shared with her husband (who was an accomplished pianist and songwriter), but the popularity of hymns in the evangelical circle to which she belonged and the belief that God’s goodness is observable in the natural world (Harding 1995). In naming the flowers in the woods beyond Mrs. Redpath’s house (June 1880)—the “carpets of pigeon berry blossoms, clumps of veronicas, wild lilies, linaea, and little wild white violets”—and asking her husband about an “odd flower which looks like a mitella” (June 1880) that she had pressed to send him, she recognizes Bernard’s expertise as the president of the Natural History Society of Montreal. She also confirms her own participation in activities associated with the study of natural phenomena. This included, most importantly, according to the norms of the Victorian era, the socially acceptable female pursuits of botanical preservation and illustration (Fig. 6).7

Display large image of Figure 6

Display large image of Figure 6

Internal Artistic Autonomy

20 Finally, Anna’s landscapes evoke her internal artistic autonomy. This is the third part of relational autonomy, wherein the aesthetic dimensions of life and art are closely linked through the processes of exploration, creative interpretation, and presentation of the landscape. From this perspective, landscape is a material form with varied colours, textures, and patterns, and diverse surfaces such as wet, arid, flat, hilly or forested. This is the visual imagery of the landscape that Anna responds to as an artist.

21 On occasion Anna inserts herself into her compositions—the artist who sits by the water absorbed in the imaginative act of creating works of aesthetic value (Fig. 7). Again and again in her letters, in a romantic language that discloses her vision of place, she sees the “tinted clouds” (1875), the “little curls of the ferns coming up” (1880), the “golden autumn fields that continue to fascinate me” (1882) and the “great hills of cumulous clouds making endless reflections and shades in the water” (1885). As she explores, interprets and presents rocky coasts, cascading waterfalls, dense forests and delicate flowers, Anna meditatively caresses forms and shapes (Fig. 8). With broad brushstrokes and thin lines she emphasizes the repetition found in visual elements such as the texture of a brittle stone, the curves of low-lying clouds, the rhythm of twisted branches and the colours of earth and grass (Fig. 9). In each artwork she imaginatively depicts her own experience of seeing and at the same time the internal demands she makes on the pictures themselves.

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 7

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 8

Display large image of Figure 9

Display large image of Figure 9

22 Within this context Anna Dawson Harrington’s letters at the McGill Archives and drawings at the McCord Museum not only demonstrate the interpersonal and social aspects of relational autonomy, but an artistic vision of landscape that is also private, particular, imaginative and autonomous, revealing her personal landscape as the material locus of her self-exploratory autobiography.